Abstract

Background:

Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is fatal. Our preclinical study presents an effective treatment against PDAC PC employing a novel oncolytic viral agent, CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1.

Study Design:

CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 is a genetically engineered chimeric orthopoxvirus, CF33, armed with the human Sodium Iodide Symporter (hNIS) and anti-PD-L1 antibody (anti-PD-L1). The in vitro cytotoxic ability of this virus against five PDAC cell lines was tested at various doses (multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10). Production and blockade function of virus-encoded anti-PD-L1 antibody were verified using immunoblot, immunoprecipitation, and PD-1/PD-L1 bioassay. In vivo mouse models of PC, with or without subcutaneous (SC) tumors created by injecting AsPC-1-ffluc cells into nude mice, were treated with PBS or a single dose (1x105 plaque-forming units) of either intraperitoneal (IP) or intravenous (IV) injections of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1. Mice with PC tumors were treated on days 0, 2, or 14 following tumor implantation.

Results:

CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 killed PDAC cells in a dose-dependent manner achieving >90% cell killing by day 8. Cells infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 produced bioactive anti-PD-L1 antibody which blocked PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. In vivo, single dose of virus reduced tumor burden and prolonged survival of treated mice. It was observed that IP administration of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 was more effective than IV administration.

Conclusion:

CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 virus is effective in infecting and killing human PDACs and producing functional anti-PD-L1 antibody. IP delivery of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 effectively reduces peritoneal tumor burden and improves survival after only one dose and is superior to IV delivery.

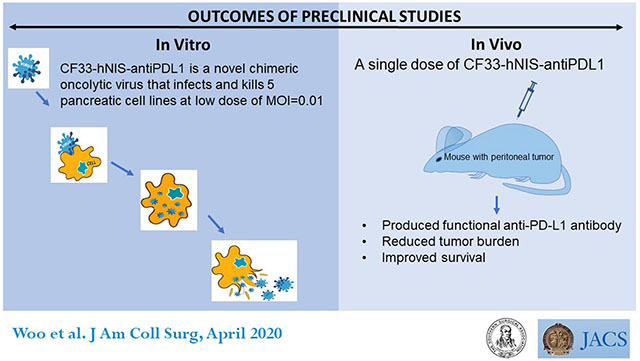

Graphical Abstract

Precis:

Intraperitoneal delivery of the novel oncolytic virus CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 reduces tumor burden and prolongs survival in preclinical models of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) tumors. Findings from this study could advance strategies for route of delivery and timing for treatment of PDAC with pancreatic cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Deaths due to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are increasing and projected to surpass colon cancer to become the second leading cause of cancer related deaths in the United States (1). The majority of PDAC patients present with incurable disease with over 50% having distant metastases at the time of diagnosis (2). While systemic regimens with fluorouracil [5-FU], leucovorin, irinotecan and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX), gemcitabine, and nab-paclitaxel have demonstrated improved survival, these treatments are associated with significant toxicities and eventual chemoresistance (3). These patients experience rapid disease progression associated with severe impairment of quality of life that involves complications like malignant ascites, , protein depletion from removal of ascites for patient comfort, jaundice, bowel obstruction, malnutrition, cachexia and inevitably death. Novel anti-cancer agents such oncolytic viruses and immune check point inhibitors as single agents or in combination are actively being investigated to improve PDAC patient outcomes (4).

Immuno-oncolytic viruses are a promising class of anti-cancer agents with inherent properties of selective infection, replication, and killing, which can be genetically engineered for local expression of immunomodulating target proteins (5). Genetically modified oncolytic viruses (OV) are being investigated for the treatment of Stage IV pancreatic cancer. Having demonstrated safety in Phase I trials, many agents have advanced to Phase II efficacy studies including herpes simplex virus 1 (T-VEC, Talimogene laherparepvec; HF10, ONYX-15 and OrienX010), vaccinia virus (VCN-01 and Pexa-vec), adenovirus (LOAd703), parvovirus (ParvOryx), and reovirus (Reolysin ®) (6).

Orthopoxviruses are especially promising as immuno-oncolytic agents, primarily due to favorable cytoplasmic replication, excellent human safety profiles, and short life cycles (5, 7, 8). We have created a potent chimeric orthopoxvirus backbone (CF33) and further modified it for better oncolytic efficacy (9–12). We have previously demonstrated that unmodified CF33 is safe and well-tolerated and effectively controls flank models of pancreatic cancer at doses of several magnitudes lower than other OVs currently under preclinical and clinical studies (11). For our study, CF33 was further armed with genes expressing hNIS and anti-programmed death ligand 1(anti-PD-L1) antibody to generate the CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 virus. This third generation CF33 variant was designed to synergize OV therapy in combination with therapeutic iodine isotope I131 treatment and enhance local anti-tumor immunity by blocking PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. The objective of our study was to determine the efficacy of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 in the regional therapy of PDAC with PC.

METHODS

Construction of the novel chimeric orthopoxvirus, CF33, and its variants

For these studies, we utilized a novel chimeric OV, CF33, and its genetically modified variants (CF33-hNIS-ΔF14.5L and CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1). The creation of CF33 and its sequenced genome has been previously described (11). Briefly, recombination among 9 different species/strains of orthopoxviruses [Cowpox (Brighton), raccoonpox (Herman), rabbitpox (Utrecht), vaccinia virus (Western Reserve), International Health Department, Elstree, and VACV strains Ankara (AS)] resulted in a chimeric orthopoxvirus, CF33, which did not previously exist in nature. This virus has been found to be highly specific for infection, replication within, and killing of breast cancer and pancreatic cancer (11, 12).

CF33-GFP and CF33-hNIS were engineered for use in preclinical experiments to allow for the detection of CF33 infection by optical and radiologic imaging by insertion of expression cassettes for GFP and hNIS within the viral genome (9). Briefly, the hNIS expression cassette under control of the vaccinia virus H5 synthetic early (SE) promoter was inserted at the thymidine kinase locus of CF33 with transient dominant selection using the guanine phosphoribosyltransferase marker (13).

CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 (CF33 expressing hNIS and anti-PD-L1)

To combine CF33-hNIS with immune checkpoint inhibition at the local tumor site, we have engineered CF33-hNIS to express anti-PD-L1 single-chain antibody fragment (scFv). This anti-PDL1 cDNA is comprised of a Igκ light chain leader sequence, the VH chain sequence of an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (14), a (G4S)3 linker sequence, the VL chain sequence, and a C-terminal DDDDK-tag (Figure 1A). The anti-PD-L1 expression cassette is under the control of the vaccinia H5 promoter. CF33-hNIS-ΔF14.5L is created as a control virus. This variant has the hNIS cassette in the J2R locus and a deletion of the F14.5L gene.

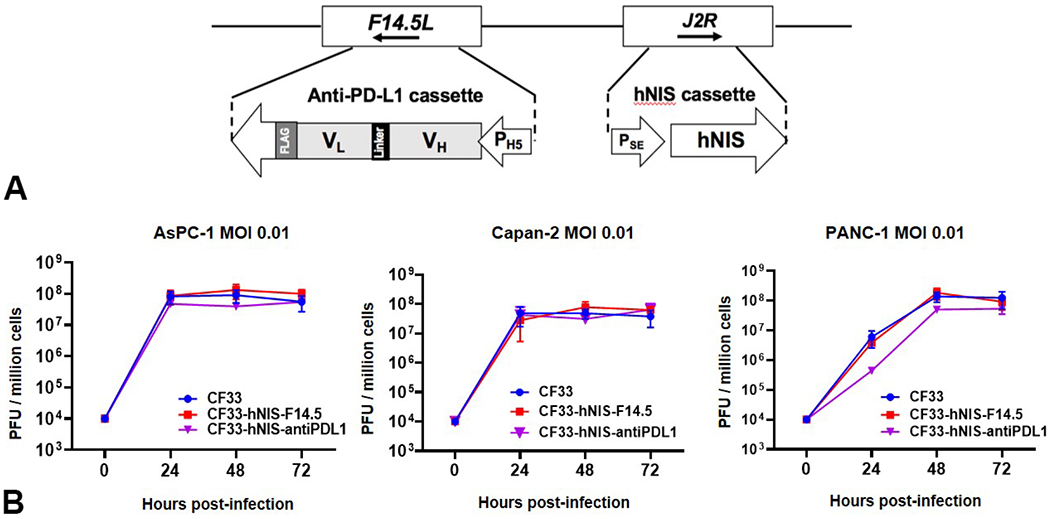

Figure 1.

Gene Construct of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 and viral replication in PDAC cell lines. (A) Schematic representation of hNIS in the J2R location and the anti-PD-L1 scFv structure in the F14.5L location. (B) After infection, viruses replicate efficiently in human PDAC cell lines AsPC-1, Canpan-2 and PANC-1, achieving 4 log increases in titer within 72 hours. Data for parental virus (CF33) as well as for doubly mutated CF33-hNIS-F14.5 and for CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 is shown.

Cell lines

Human PDAC cell lines AsPC-1, PANC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and BxPC-3 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Capan-2 was a kind gift from Dr. Teresa Ku’s lab (City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA). Capan-2 was cultured using McCoy’s 5A medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution. All other pancreatic cancer cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic solution (Corning, NY). The cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. African green monkey kidney fibroblasts (CV-1) were purchased from ATCC. CV-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic solution.

Virus infection and proliferation assay

AsPC-1, Capan-2 and PANC-1 cells were plated in 6-well plates at 5x105 cells/well and incubated overnight. The next day, cells were counted and infected with viruses. Briefly, media from the wells was removed, and viruses diluted in medium containing 2.5% FBS were added to each well in a total volume of 0.5 mL such that the ratio of cells to virus was 100:1 i.e. multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 plaque-forming units (pfu)/cell. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by aspiration of inoculum, and addition of 2 mL media containing 10% FBS to each well. Plates were then returned to the incubator. Cell lysates were collected by scrapping at the indicated time points and virus titers in the lysates were determined by standard plaque assay technique as described previously (9).

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells were seeded at 3,000 cells/well in 96-well plates with 100 μL/well of specific medium supplemented with 10% FBS and were incubated overnight. Each virus was thawed on ice and sonicated for 1 min and appropriate MOIs (0.01, 0.1, 1.0 and 10.0) were calculated and prepared for infection in medium added with 2.5% FBS for 20μL/well. Cell viability was measured in triplicate every 24 hours for six days via MTS cell proliferation assay using CellTiter 96 Aqueous One solution (Promega, Madison, WI) on a spectrophotometer (Tecan Spark 10M, Mannedorf, Switzerland) at 490 nm (9).

Establishment of AsPC-1-ffluc cell lines

To quantitate tumor volume and dissemination in vivo using non-invasive optical imaging (Xenogen), AsPC-1 cells (pancreatic cancer cell line derived from metastatic ascites) were modified to stably encode firefly luciferase using lentiviral transduction. Briefly, ASPC-1 cells were incubated with polybrene (4 mg/mL, Sigma) in RPMI-1640 (Lonza) containing 10% FBS, Hyclone), and 1X antibiotic-antimycotic (AA, Gibco) and infected with lentivirus carrying ffluc cDNA under the control of the EF1α promoter. Expression of ffluc in AsPC-1 cells was confirmed and single-cell subcloning was performed by the limiting dilution method (15).

Immunoprecipitation assay

AsPC-1 cells were infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 (MOI=3) for 72 hours and cells and supernatants were harvested. Anti-DDDDK-tag monoclonal antibody (BioXcell) was used to pull-down anti-PD-L1, and polyclonal anti-DDDDK-HRP (abcam) was used to blot the anti-PD-L1 antibody.

PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Bioassay

The supernatant of CV1 cells infected with the CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 virus (MOI=3) for 48 hours was tested for anti-PD-L1 antibody using the anti-DDDDK-tag antibody pull-down method. PD-1/PD-L1 Bioassay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to confirm the functionality of the virus-encoded anti-PD-L1 antibody. Commercial anti-human PD-L1 (BioXcell, clone# 29E.2A3) was used as a positive control and commercial anti-mouse PD-L1 (BioXcell, clone# 10F.9G2) was used a negative control.

Late treatment cohorts

Animal model of subcutaneous and peritoneal dissemination xenograft of PDAC

Animal studies were performed under the City of Hope Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocol. Six-week-old Hsd:Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu female and male mice (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) were purchased and acclimatized for 7 weeks. To represent unresectable PDAC with peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) and distinguish tumor burden at the time of imaging, an animal model of the unilateral shoulder and peritoneal xenograft was generated by both subcutaneous and peritoneal injection of AsPC-1-ffluc cells. Injection of 5×106 AsPC-1-ffluc cells in a total volume of 100 μL PBS containing 50% matrigel into the unilateral shoulder and peritoneal cavity was performed for each mouse (16, 17).

Animal model of peritoneal dissemination xenograft of PDAC

The animal model of PC was created by peritoneal injection of 5×106 AsPC-1-ffluc cells in a total volume of 100 μL PBS containing 50% matrigel for each mouse (16, 17).

Treatment of peritoneal disease

To simulate treatment of microscopic peritoneal cytology positive tumor burden, AsPC-1-ffluc cells were implanted into the intraperitoneal cavity and then treated immediately (D0), at 2 days (D2), or at day 14 (D14) post injection of cancer cells. Treatment groups included PBS injected controls (control), intravenously (IV) injected virus, and intraperitoneally (IP) injected virus. Each animal in the IV group was injected with 105 pfu CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 in 100 μL volume into the tail vein; the IP group was injected with 105 pfu CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 in 100 μL volume into the peritoneal cavity; and the PBS control group was intravenously and peritoneally injected with PBS in 100 μL volume. On day 2 and beyond, tumor burden was verified using bioluminescence imaging for luciferase activity. Mice were observed and evaluated for survival, tumor burden (luciferase imaging of peritoneal tumor and weight of tumor at death), weight, jaundice, and cachexia. Animals were euthanized if they lost >20% of their body weight, demonstrated jaundice, cachexia, inability to groom and eat, as per institutional guidelines.

Luciferase imaging

Each animal underwent bioluminescence imaging for luciferase activity of the tumor and was quantified to evaluate for tumor burden once a week and prior to euthanizing. D-luciferin solution was prepared by dissolving 1 g of XenoLight D-luciferin—K+ Salt Bioluminescent Substrate (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) in 35 mL of PBS at 28.5 mg/mL concentration. IP delivery (200 μL/mouse) was performed in all groups and the mice were imaged using Lago X optical imaging system (Spectral Instruments Imaging, Tucson, AZ). Bioluminescence imaging was analyzed using Aura64 software (11).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Tumors were harvested at the end of mouse life, fixed with 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5 μm thick section. Sections were stained with anti-human pan-keratin antibody (Roche Tissue Diagnostics, Clone: AE1/AE3/PCK26) or anti-DDDDK Tag antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Clone: D6W5B Rabbit mAb). Images were obtained using Ventana Image Viewer.

Statistical analysis

Assay results were expressed as means ±SEM, and paired or unpaired Student’s t-tests were used for comparisons. All p-values are two-sided. Data and Kaplan Meier curves for survival were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (version 7, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Comparison of survival was by log-rank.

RESULTS

CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 efficiently infects and replicates in PDAC cell lines

For in vitro experiments, AsPC-1, Capan-2 and PANC-1 (each representing one of the three main molecular subtypes of PDACs, classical, quasi-mesenchymal and exocrine like respectively (18)) were used to detect the infection and replication of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1. Results demonstrate that CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 successfully infected and replicated in all three PDAC cell lines at an MOI as low as 0.01, with the plateau of replication reached at 24 or 48 hours after infection (Figure 1B). Replication efficiency of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 was similar to the parental virus CF33, and CF33-hNIS-ΔF14.5L in all PDAC cell lines, suggesting that replacement of the two viral genes J2R and F14.5L with hNIS and anti-PD-L1 expression cassettes, respectively, has no effect on the ability of the virus to grow in cancer cells (Figure 1B).

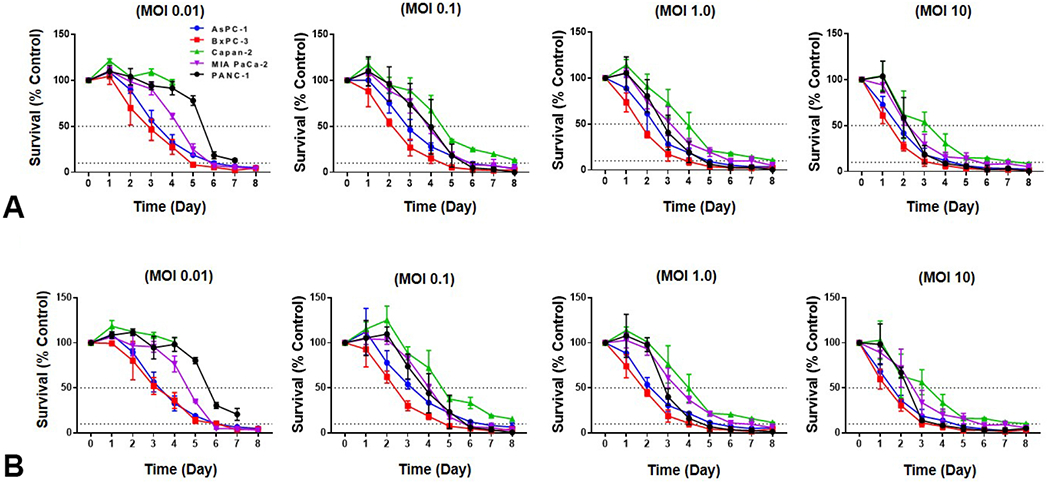

CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 demonstrates cytotoxic effects against PDAC cell lines

Cytotoxic ability of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 was evaluated in human PDAC cell lines AsPC-1, BxPC-3, CaPan-1, MIAPaca2, and PANC-1. CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1, like its backbone control CF33-hNIS-ΔF14.5L, killed all five PDAC cell lines in a dose and time-dependent manner, reaching >90% cell killing within 8 days. Even at the lowest MOI 0.01, efficient cell killing was observed in all five cell lines (Figure 2A and 2B). The results demonstrate that the novel engineered OV, CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1, maintains its oncolytic function in PDACs.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 in human PDAC cell lines in vitro. Five human PDAC cell lines AsPC-1, BxPC-3, Capan-2, MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 were used to evaluate the cytotoxic efficacy of (A) CF33-hNIS-ΔF14.5L and (B) CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 with an MOI 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10.

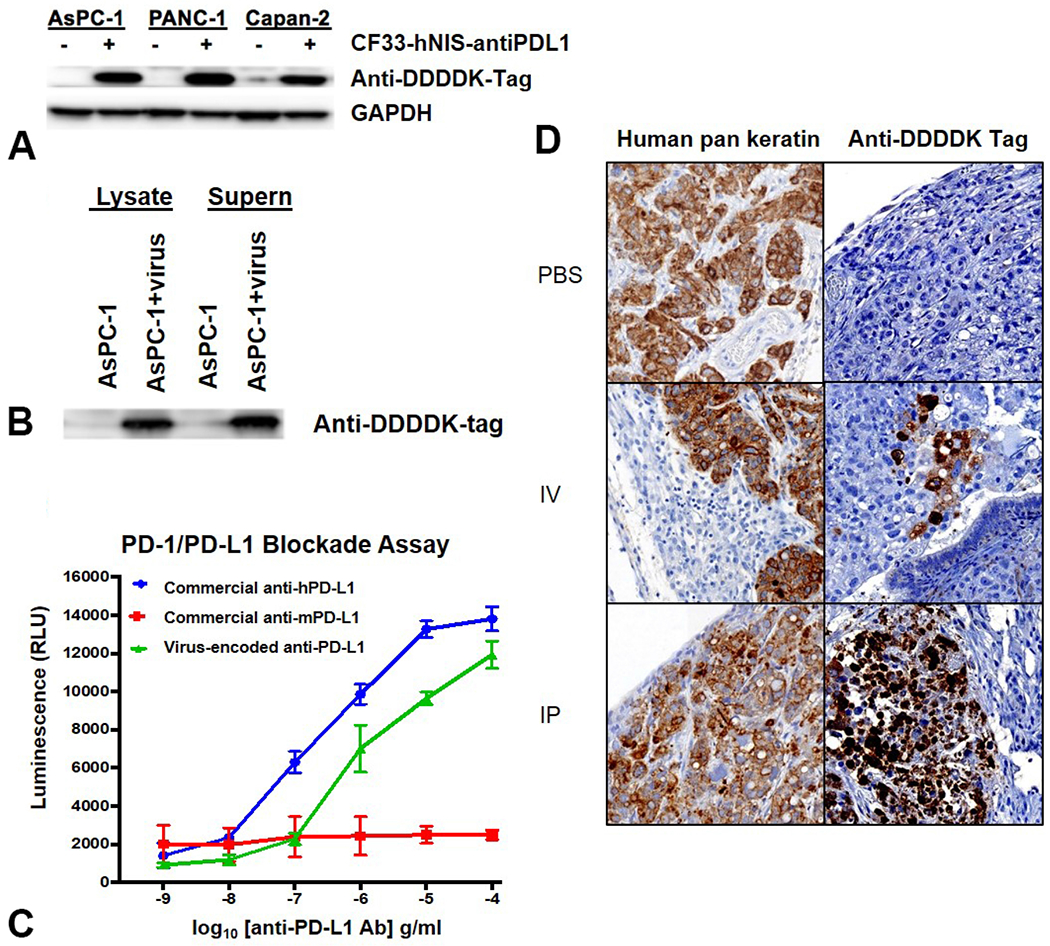

PDAC cell lines infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 secrete functional anti-PD-L1 antibody

In order to locally modulate the immunosuppressive environment of PC to enhance therapeutic response, CF33-hNIS was armed with an anti-PD-L1 expression cassette. To verify the antibody expression and blockade function, first, AsPC-1, Capan-2, and PANC-1 were infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 (MOI=0.01) for 48 hours, and anti-PD-L1 expression was analyzed using anti-FLAG antibody. The FLAG (DDDDK) tag was inserted in the anti-PD-L1 expression cassette for easy detection of anti-PDL1. Anti-PD-L1 protein was expressed from all three PDAC cell lines infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 (Figure 3A). Secondly, a monoclonal anti-DDDDK-tag antibody was used to immunoprecipitate the anti-PD-L1 antibody. Virus-encoded anti-PD-L1 antibody was pulled down from both cell lysate and supernatant in AsPC1 cells after infection with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 (Figure 3B). Next, PD1/PD-L1 blockade assay was used to test the functionality of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 virus-encoded anti-PD-L1 antibody. It was observed that purified CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 virus-encoded anti-PD-L1 antibody from the cell culture supernatant of infected cells could block PD1/PD-L1 interaction similar to commercial anti-human PD-L1 antibody (Figure 3C). These results suggest that functional anti-PD-L1 is produced from cells infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1.

Figure 3.

Cells infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 produce functional anti-PD-L1 antibody in vitro and in vivo. (A) AsPC-1, PANC-1 and Capan-2 cells infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 (MOI=0.01) for 48 hours were harvested, lysed and blotted with anti-DDDDK-tag antibody to demonstrate protein expression of anti-PD-L1 antibody by the virus. (B) Lysate and supernatant from AsPC-1 cells infected with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 (MOI=3) for 72 hours show presence of virus produced anti-PD-L1 antibody. (C) PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Bioassay shows an increase in luminescence signal, demonstrating the ability of virus encoded anti-PD-L1 antibody from cell culture of infected CV1 cells to block PD1/PD-L1 interaction, similar to commercial anti-human PD-L1 antibody, thus demonstrating that the antibody is biologically functional. (RLU: relative light units) (D) Immunohistochemical staining of mouse tumor sections of PC. Peritoneal tumor nodules were stained with anti-human pan-keratin antibody to identify cancer (column one) and anti-DDDDK tag antibody staining verified virus-encoded anti-PD-L1 antibody production within the tumor (column two). (20x using Ventana Viewer Imaging software)

To verify that human PDAC AsPC-1 tumors in vivo injected with virus produce virus-encoded anti-PD-L1 antibody, immunohistochemical staining was performed on tumors harvested from the peritoneum of euthanized mice. AsPC-1 cells in the PC were positively stained with anti-human pan-keratin antibody, and the surrounding mouse tissue was observed to be negative in all groups (Figure 3D). Tumors were negative for virus-encoded anti-DDDK-PDL1 in the PBS treated mice. However, tumors stained positive for anti-DDDK-PDL1 following IV or IP treatment with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 and it was observed that IP treatment showed stronger staining for anti-PD-L1 protein compared to the IV group throughout the tumor sections (Figure 3D).

Treatment with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 shows anti-tumor efficacy against human PDAC xenografted in mice

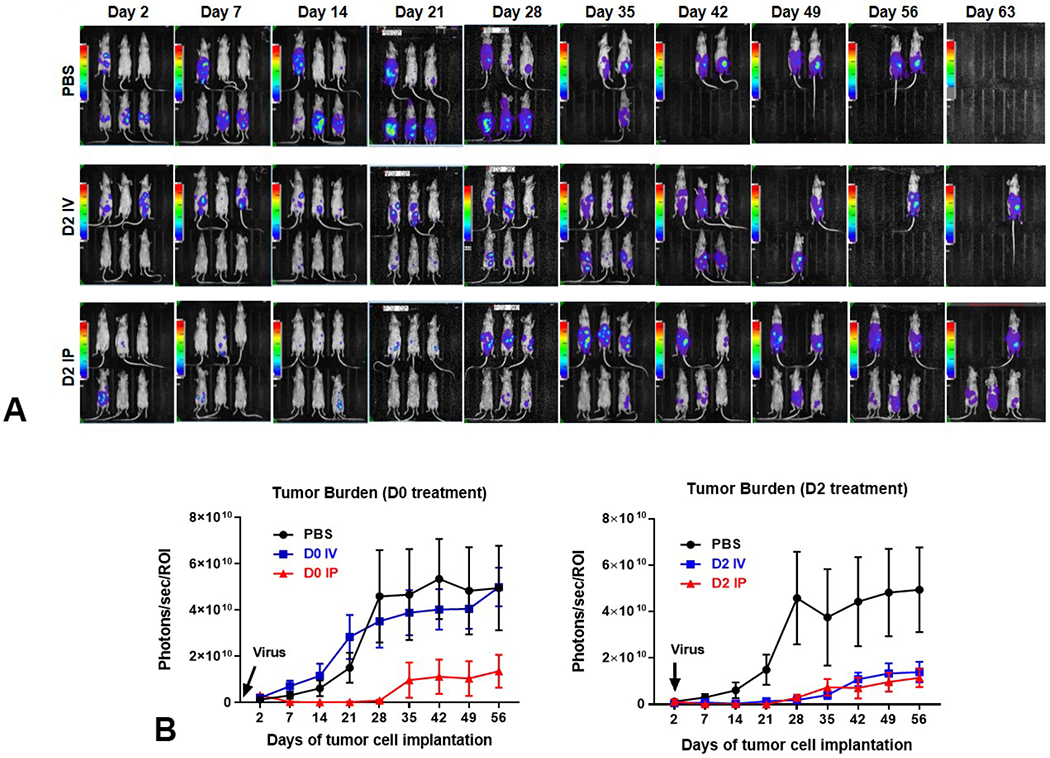

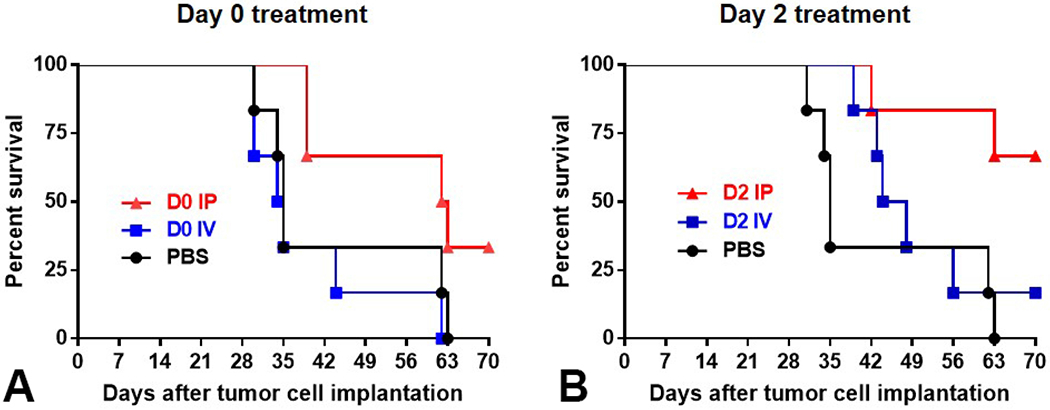

To test the antitumor effect of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 in xenograft models with early stages of PC (early treatment cohorts), nude mice with PDAC PC were treated with either PBS, or CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 via IV or IP delivery on day 0, day 2, or day 14 after tumor implantation. Bioluminescent imaging showed that the IP group had the greatest reduction in peritoneal tumor burden at 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks as compared to the control group (p<0.01, Figure 4). For day 0 and day 2 treated animals, this translated to a survival advantage (p<0.05, p<0.01 respectively, Figure 5). More importantly, IV treatment was more effective on day 2 (after peritoneal attachment) than on day 0.

Figure 4.

Significant decrease in peritoneal tumor burden is seen after treatment with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1. (A) Bioluminescence images of animals intraperitoneally implanted with 5x106 AsPC-1-ffluc human pancreatic tumor cells and treated on day two with PBS (controls), IV virus (IV), or IP virus (IP). (B) Graphic representation of luminescence data representative of intraperitoneal tumor burden is shown for treatment immediately after tumor implantation (D0; p<0.001 IP vs other groups) or on day 2 (D2; p<0.01 PBS vs other groups).

Figure 5.

Early IP treatment with CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 increases overall survival in a nude mouse model of the human pancreatic cancer cell line - AspC-1-ffluc. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of the survival of mice with AsPC-1-ffluc peritoneal tumor (5x106 cells IP) treated on the same day ((A) D0, and (B) D2 - by either PBS, or CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1, 105 pfu, IP vs IV). IP treatment on D0 and D2 significantly improved survival compared to PBS or IV treatment.

This is an aggressive tumor model, where animals start getting sick by day 21, and start dying by day 28. However, IP treatment significantly decreased local complications including less biliary obstruction compared to both the IV treated and control groups (14.2% vs. 50% and 50%, respectively). Notably, in the animals treated at day 14, there was a trend toward tumor attenuation and improved survival for IP treatment that did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Outcomes for patients with PC resulting from PDAC are uniformly fatal and current treatment strategies are limited by an inability to control the disease as well as treatment-associated complications. Patients who undergo radical pancreatectomy with occult peritoneal metastases have a worse prognosis as compared to those who have no cancer cells in the peritoneum (19). Systemic therapies are unable to penetrate the peritoneal barrier at sufficient doses to control even the microscopic disease burden. Thus, many regional therapies are being attempted for the treatment of this condition. Attempts have been made for surgical cytoreduction of peritoneal disease, combined with intraperitoneal chemotherapy. These approaches in PDAC patients are limited not only by the difficulty of safely achieving complete cytoreduction but also due to a lack of effective agents to eliminate residual/microscopic disease even with IP therapies. Human trials of this approach have repeatedly demonstrated that higher concentrations of anticancer agents are achievable by peritoneal delivery and that patients who have low peritoneal cancer index score (<12), and those patients who can undergo complete cytoreductive surgery (<2.5mm of tumor) have the best survival benefit (20–24).

Our study demonstrates the preclinical effectiveness of the novel immuno-oncolytic agent, CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1, against PDAC in vitro and in vivo. CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 shows oncolytic efficacy against human PDAC cell lines in a dose-dependent manner with effectiveness starting at an MOI as low as 0.01 (one virus per 100 cancer cells), demonstrating the efficiency of this virus to replicate in PDAC. Virus replication was efficient, achieving more than four logs above starting dose just three days after injection. These data are consistent with our previous report of the virus’ ability to cure PDAC xenografts in mice with as little as a single dose of 103 PFUs. Further, data from the current study also confirm the safety of in vivo administration of virus reported previously (10–12).

The novel virus, CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1, is a promising agent in the treatment of PC as demonstrated by the strong antitumor activity including significantly reduced tumor burden, and improved survival after early IP treatment. This study provides insight into the optimal mode of delivery of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 in the regional control of peritoneal disease. As IP delivery of the virus led to significantly decreased local complications, our results demonstrate the superiority of the IP route of treatment over the IV route in vivo. IP delivery of a potent immune-oncolytic agent is a new promising strategy in the treatment of patients with PDAC PC to reduce tumor burden and provide symptom control with the potential to improve survival.

There is increasing evidence that one major mechanism of action used by OVs is to upregulate the expression of local checkpoint proteins and sensitize tumors to simultaneously delivered checkpoint inhibitors (4). CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1, has been designed not only to target cancer cells regardless of the mode of delivery (IV, IP or intratumoral - IT) and mediate direct cancer killing, but also to produce the anti-PD-L1 protein which could further add to its oncolytic efficacy through enhancing anti-tumor immune cell function. This study demonstrates the robust production of anti-PD-L1 in the local tumor environment. Moreover, PDAC cells infected with the virus produced bioactive anti-PD-L1 antibody which was shown to block PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. A limitation of our study is that the virus was evaluated in a nude mouse model and hence further studies are required to understand the potential for immune modulation or possible additive/synergistic effects of anti-PD-L1 expression. Overall, our preclinical results demonstrate that regional therapy via IP treatment for PDAC PC is more effective than IV and prolongs survival.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we show that CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1, a functionally active artificially designed immune-oncolytic agent that effectively targets and kills human PDAC tumors demonstrates greater efficacy against peritoneal disease when delivered intraperitoneally versus intravenously. Importantly, early IP treatment of PDAC PC significantly decreased tumor burden, delayed time to disease progression and prolonged survival in preclinical models of PDAC PC. These data encourage trials of CF33-hNIS-antiPDL1 in patients with disseminated PC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Seonah Kang, Byungwook Kim, Martha Magallanes, Dr Venkatesh Sivanandam and Dr. Maria Hahn in our laboratory for technical support. The authors thank flow cytometry core and animal facility for supporting our work. The authors thank Supriya Deshpande, PhD for manuscript editing assistance.

Support:

Dr Wu was supported in part by grant CA180425 from the Department of Defense, Dr Fong was supported by grant CIRM DISC2-10524 from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, and grant number P30CA033572 from the NIH. Dr Warner is supported by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant (MRSG-16-047-01-MPC).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PC

Peritoneal carcinomatosis

- OV

oncolytic viruses

- antiPDL1

anti-programmed death ligand 1

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- IV

intravenous

- IP

intraperitoneal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the Southern Surgical Association 131st Annual Meeting, Hot Springs, VA, December 2019.

Disclosure Information: CF33 has been licensed to Imugene Inc for clinical development. City of Hope Medical Center holds the patent to CF33.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014. Jun 1;74(11):2913–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weledji EP, Enoworock G, Mokake M, Sinju M. How Grim is Pancreatic Cancer? Oncol Rev. 2016. Apr 15;10(1):294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Camateros P, Cheung WY. A Real-World Comparison of FOLFIRINOX, Gemcitabine Plus nab-Paclitaxel, and Gemcitabine in Advanced Pancreatic Cancers. J Gastrointest Cancer 2019. Mar;50(1):62–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribas A, Dummer R, Puzanov I, et al. Oncolytic Virotherapy Promotes Intratumoral T Cell Infiltration and Improves Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cell. 2017. Sep 7;170(6):1109–19.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddad D, Zanzonico PB, Carlin S, et al. A vaccinia virus encoding the human sodium iodide symporter facilitates long-term image monitoring of virotherapy and targeted radiotherapy of pancreatic cancer. J Nucl Med 2012. Dec;53(12):1933–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaRocca CJ, Warner SG. A New Role for Vitamin D: The Enhancement of Oncolytic Viral Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Biomedicines. 2018. Nov 5;6(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jun KH, Gholami S, Song TJ, et al. A novel oncolytic viral therapy and imaging technique for gastric cancer using a genetically engineered vaccinia virus carrying the human sodium iodide symporter. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2014. Jan 2;33:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen NG, Yu YA, Zhang Q, Szalay AA. Replication efficiency of oncolytic vaccinia virus in cell cultures prognosticates the virulence and antitumor efficacy in mice. J Transl Med 2011. Sep 27;9:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaurasiya S, Chen NG, Lu J, et al. A chimeric poxvirus with J2R (thymidine kinase) deletion shows safety and anti-tumor activity in lung cancer models. Cancer Gene Ther 2019. Jun 17. [ePub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi AH, O’Leary MP, Lu J, et al. Endogenous Akt Activity Promotes Virus Entry and Predicts Efficacy of Novel Chimeric Orthopoxvirus in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2018. Jun 29;9:22–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Leary MP, Choi AH, Kim SI, et al. Novel oncolytic chimeric orthopoxvirus causes regression of pancreatic cancer xenografts and exhibits abscopal effect at a single low dose. J Transl Med 2018. Apr 26;16(1): 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Leary MP, Warner SG, Kim SI, et al. A Novel Oncolytic Chimeric Orthopoxvirus Encoding Luciferase Enables Real-Time View of Colorectal Cancer Cell Infection. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2018. Jun 29;9:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warner SG, Kim SI, Chaurasiya S, et al. A Novel Chimeric Poxvirus Encoding hNIS Is Tumor-Tropic, Imageable, and Synergistic with Radioiodine to Sustain Colon Cancer Regression. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2019. Jun 28;13:82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cha E, Wallin J, Kowanetz M. PD-L1 inhibition with MPDL3280A for solid tumors. Semin Oncol. 2015. Jun;42(3):484–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Priceman SJ, Gerdts EA, Tilakawardane D, et al. Co-stimulatory signaling determines tumor antigen sensitivity and persistence of CAR T cells targeting PSCA+ metastatic prostate cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(2):e1380764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito D, Fujimoto K, Mori T, et al. In vivo antitumor effect of the mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 and gemcitabine in xenograft models of human pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer 2006. May 1;118(9):2337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizukami T, Kamachi H, Fujii Y, et al. The anti-mesothelin monoclonal antibody amatuximab enhances the anti-tumor effect of gemcitabine against mesothelin-high expressing pancreatic cancer cells in a peritoneal metastasis mouse model. Oncotarget. 2018. Sep 18;9(73):33844–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguirre AJ. Refining Classification of Pancreatic Cancer Subtypes to Improve Clinical Care. Gastroenterology. 2018. Dec;155(6):1689–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly KJ, Wong J, Gladdy R, et al. Prognostic impact of RT-PCR-based detection of peritoneal micrometastases in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol 2009. Dec;16(12):3333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamath A, Yoo D, Stuart OA, Bijelic L, Sugarbaker PH. Rationale for an intraperitoneal gemcitabine chemotherapy treatment for patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov 2009. Jun;4(2):174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugarbaker PH. Peritoneal Metastases, a Frontier for Progress. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2018. Jul;27(3):413–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugarbaker PH. Peritoneal Metastases from Gastrointestinal Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2018. Jun 8;20(8):62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji ZH, Peng KW, Yu Y, et al. Current status and future prospects of clinical trials on CRS + HIPEC for gastric cancer peritoneal metastases. Int J Hyperthermia 2017. Aug;33(5):562–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugarbaker PH. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of gastrointestinal cancers with peritoneal metastases: Progress toward a new standard of care. Cancer Treat Rev 2016. Jul;48:42–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]