Abstract

An unusual black-pigmented coryneform bacterium was isolated from the urogenital tract of a woman who experienced a spontaneous abortion during month 6 of pregnancy. Biochemical and chemotaxonomic analyses demonstrated that the unknown bacterium belonged to the genus Corynebacterium. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA sequences (GenBank accession no. AF220220) revealed that the organism was a member of a distinct subline which includes uncultured Corynebacterium MTcory 1P (GenBank accession no. AF115934), derived from prostatic fluid, and Corynebacterium CDC B8037 (GenBank accession no. AF033314), an uncharacterized black-pigmented coryneform bacterium. On the basis of chemotaxonomic and phylogenetic evidence, this organism probably represents a new species and is most closely related to the uncharacterized Centers for Disease Control and Prevention group 4 coryneforms. Our strain is designated CN-1 (ATCC 700975).

Corynebacteria are a heterogeneous group of bacteria frequently associated with bacteremia, endocarditis, and wound, urinary tract, and respiratory tract infections. Many of them are considered normal flora of skin and mucous membranes, whereas some occupy a specific niche. Due to an increase in the number of immunocompromised patients, interest in Corynebacterium as an opportunistic pathogen has increased. In the last decade, new molecular genetic techniques, such as 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, have allowed the identification of several new species of Corynebacterium from clinical specimens (4, 5, 11, 17). Currently, the genus Corynebacterium includes at least 36 species, most of which are medically relevant (2, 3, 6). We report the isolation and characterization of an unusual black-pigmented Corynebacterium sp. from a woman with spontaneous abortion.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 34-year-old woman who presented with the sudden onset of premature labor during month 6 of pregnancy. The obstetrical history was unremarkable except for mild endometriosis. There was no history of diabetes, immunosuppression, previous miscarriages, sexually transmitted diseases, or antibiotic use during the pregnancy. Attempts to suppress labor with magnesium sulfate tocolysis were unsuccessful, and the fetus expired during vaginal delivery. External examination of the fetus revealed no anomalies. The mother was afebrile, and histologic examination of the placenta did not show evidence of chorioamnionitis. A vaginal sample taken at the time of delivery was culture negative for group B Streptococcus. However, moderate growth of a black-pigmented, diptheroid-like bacterium was observed. The patient had an uneventful postpartum recovery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and cultivation of Corynebacterium sp. strain CN-1.

Strain CN-1 has been deposited in the American Type Culture Collection (accession number 700975). This strain was isolated from the vaginal swab of a 34-year old patient after she had a spontaneous abortion during month 6 of pregnancy. The strain was isolated on a 5% sheep blood agar plate (BAP) (Remel, Lenexa, Kansa.) incubated for 24 h at 35°C in a 5% CO2-enriched environment. It was subcultured on both 5% sheep BAPs and chocolate agar plates incubated under the conditions described above.

Phenotypic analysis.

Biochemical reactions were performed using the API Coryne system (BioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and other standard biochemical media. The tyrosine hydrolysis test was done with tyrosine agar plates (BBL, Cockeysville, Md.) at 37°C. The DNase test was done with RIM DNase (Remel). Cellular fatty acids (CFAs) were determined with the Microbial Identification System (Microbial ID, Inc., Newark, Del.) after 48 h of incubation at 35°C on 5% BAPs. The CAMP test was performed as described previously (6). A lipophilic test was performed by comparing the growth of strain CN-1 on BAPs with and without 0.1% Tween 80 (7).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The antimicrobial susceptibility of strain CN-1 to a number of antimicrobial agents was tested by the E-test and the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method with Mueller-Hinton agar plates supplemented with 5% sheep blood. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 h. Since the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards has not explicitly set the breakpoints for susceptibility and resistance for Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus aureus was used as a standard to determine the MIC, as has been done in other Corynebacterium reports (10).

16S rRNA gene analysis.

The 16S rRNA gene of strain CN-1 was amplified by PCR utilizing the broad-range eubacterial primers 27F (5′AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG3′) and 1522R (5′ AAG GAG GTG ATC CAG CC3′) (16). The PCR was performed with a PE7000 thermocycler, a GeneAmp PCR kit, and AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.). A 100-μl PCR mixture consisted of 10 μl of 10× PCR buffer; 1.4 mM MgCl2; 200 μM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 2.5 U of Taq polymerase; 20 pmol each of forward and reverse primers, and 5 μl of template DNA. The ∼1,540-bp PCR product was column purified and then sequenced by cycle sequencing with several Cy-5-labeled nested primers. The sequencing reaction was resolved in a 5% sequencing gel for 12 h with an ALF Express DNA sequencer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). The DNA sequence was aligned using DNAsis (Hitachi Software Engineering Company, Ltd., San Bruno, Calif.) and edited manually to determine the 1,437-nucleotide-long consensus sequence (GenBank accession no. AF220220). The ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequence was compared to all bacterial sequences available from the GenBank database by using the BLAST 2.0 program (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md.).

Phylogenetic analysis.

The rDNA sequence of Corynebacterium sp. strain CN-1 was aligned with a database of archaeal, bacterial, and eucaryal small-subunit rRNA sequences (ca. 8,000 sequences in total) using the ARB software package (http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de/pub/ARB/documentation/arb.ps). Both BLAST analysis and the parsimony insertion tool of ARB tentatively placed the CN-1 sequence within the corynebacterial clade. Consequently, a subset of the ARB alignment, including the CN-1 sequence, 58 corynebacterial sequences (which represent the known extent of the genus), and the sequences of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Rothia dentocariosa (used as outgroups), was selected for phylogenetic analysis and minimized by use of the Lane Mask (a total of 1,241 positions were sampled) (9). A dendrogram was constructed by evolutionary distance analysis (neighbor joining with Olsen correction) with the ARB package (see above). The robustness of this tree was assessed by bootstrap resampling (100 replicates) of evolutionary distance trees (PAUP∗ version 4.0b2 (14); weighted least-squares mean with Kimura two-parameter correction). Parsimony analyses (ARB or PAUP∗) provided results that were substantially similar to those obtained with the evolutionary distance algorithm.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

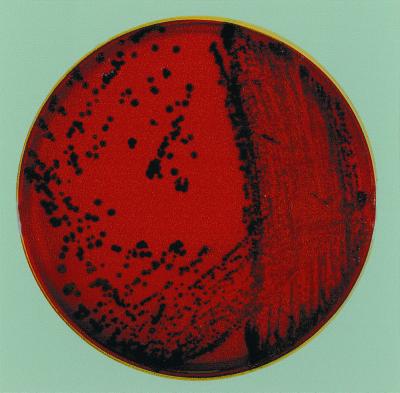

The Corynebacterum sp. was isolated from the vaginal culture of a woman after she had a spontaneous abortion during month 6 of pregnancy. This strain, designated CN-1, was isolated in conjunction with other normal urogenital flora on a 5% sheep BAP incubated at 35°C in a 5% CO2-enriched environment. The CN-1 colonies were 1 to 1.5 mm in diameter, very dry, rough, and pitted in agar after 36 to 48 h. The colonies turned black after 24 to 72 h of incubation (Fig. 1). Microscopic examination revealed that the organism was gram positive and had a diptheroid-like morphology. The isolate was nonlipophilic, non-acid fast, and negative for the CAMP test. The black-pigmented nature of the CN-1 colonies makes this species different from all other reported Corynebacterium species. It is possible that some strains in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention group 4 coryneforms are related to strain CN-1.

FIG. 1.

Colonies of Corynebacterium sp. strain CN-1 grown for 48 to 72 h on a BAP.

The biochemical profile, as determined with the API Coryne system, showed that the strain was catalase positive and fermented glucose, ribose, maltose, sucrose, and glycogen. However, ribose, sucrose, and glycogen fermentation was weak at 24 h of incubation. Strain CN-1 did not ferment xylose, mannitol, and lactose after 72 h of incubation. This isolate was also positive in pyrazinamidase and alkaline phosphatase tests and negative in nitrate reduction, pyrrolidonyl arylamidase, β-glucouridase, β-galactosidase, α-glucosidase, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, esculin, urea, and gelatin hydrolysis tests. Based on the above results, the API Coryne database gave the numerical code 2100327 for this isolate. This code, however, did not yield any identification from the present database. Strain CN-1 did not hydrolyze casein, starch, or xanthine and was negative for DNase activity.

A variety of antimicrobial agents were used to determine the antibiogram of strain CN-1. The MICs of the antibiotics tested were as follows: erythromycin, 0.016 μg/ml; vancomycin, 0.50 μg/ml; clindamycin, 0.50 μg/ml; ceftriaxone, 1.5 μg/ml; tetracycline, 0.50 μg/ml; piperacillin, 4.0 μg/ml; and quinupristin-dalfopristin (Synercid), 0.75 μg/ml. Strain CN-1 was also susceptible to the following agents, as measured by the Kirby-Bauer method: cephalothin (38 mm), amikacin (28 mm), ciprofloxacin (33 mm), chloramphenicol (28 mm), ceftriaxone (25 mm), tobramycin (28 mm), ticarcillin (32 mm), and rifampin (39 mm). Of the antibiotics tested, this strain was resistant only to penicillin (0.25 μg/ml).

Since the genus Corynebacterium consists of a complex group of organisms, strain CN-1 was also characterized by chemotaxonomic and genetic analyses (7, 8). Analysis of the total CFAs showed that C16:0 (37 to 42%), C18:ω9c (41 to 52%), C18:0 (8%), and C16:ω9c (3%) were the major fatty acids. These chemotaxonomic data were variable and, as a consequence, Microbial Identification system (Microbial ID, Inc.) was unable to identify the strain to the species level, probably because of limitations of the database. Some other species of Corynebacterium show similar variations in their CFA profiles, suggesting that CFA profiles alone cannot be used to identify Corynebacterium to the species level (13).

Molecular phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence was used to identify and determine the phylogenetic position of strain CN-1. A 1,437-bp 16S rDNA sequence from strain CN-1 was compared to all bacterial sequences available in the GenBank database. There was >99% identity with two Corynebacterium clone sequences present in GenBank. The first was uncultured Corynebacterium MTcory1P (GenBank accession no. AF115934), which was amplified from patients with bacterial and nonbacterial prostatitis (15). The second was Corynebacterium CDCB8037 (GenBank accession no. AF033314); the uncharacterized strain CDCB3087 apparently belongs to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention group 4 coryneforms, which show gray or black pigmentation (1).

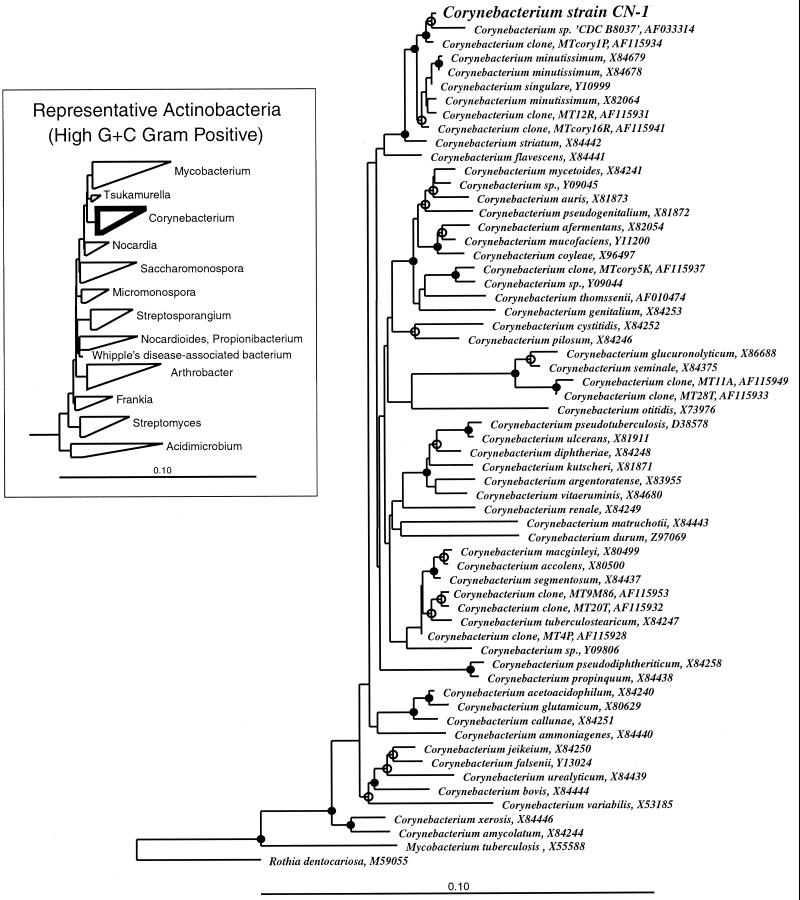

The phylogenetic relationship between CN-1 and other Corynebacterium species was inferred by parsimony and evolutionary distance analyses. A representative evolutionary distance dendrogram and parsimony analysis gave qualitatively similar results (Fig. 2). Bootstrap resampling of 16S rRNA sequence data provided strong support for a specific clade composed of CN-1, MTcory1P, and CDCB8037 (bootstrap values of 93% for distance analysis and 87% for parsimony analysis). Although distance analysis provided some support for CN-1 and CDCB8037 being sister groups to the exclusion of MTcory1P (bootstrap value of 68%), parsimony analysis was unable to resolve the branching order of the three sequences.

FIG. 2.

Evolutionary distance dendrogram of selected corynebacterial 16S rRNA sequences, including that of Corynebacterium sp. strain CN-1. M. tuberculosis (X55588) and R. dentocariosa (M59055) were chosen as outgroups for phylogenetic analysis. Sequences are identified by species name and GenBank accession number. R. dentocariosa is representative of Arthrobacter. Branch points supported by >74% bootstrap values are indicated by filled circles; open circles represent branch points with bootstrap values in the range of 50 to 74%. Branch points without circles were not resolved (bootstrap values of <50%) as specific groups by this analysis. The diagram at left depicts the evolutionary relationship between the genus Corynebacterium and other major groups of the Actinobacteria (the high-G+C-content, gram-positive groups). The height of each triangle (along the vertical axis) is proportional to the number of sequences included in a group. The bar at the bottom of each diagram indicates the number of nucleotide changes per site.

Since no physiological and biochemical data are available for CDCB8037 and no cultivar has been isolated for the MTcory1P sequence, we were unable to determine any relatedness at the physiological level. Other strains closely related to strain CN-1 are Corynebacterium minutissimum, a normal flora of the skin, and C. singulare, a urease-positive organism isolated from semen (12). The biochemical profiles of strain CN-1 are compared with those of these two species and other relevant Corynebacterium species with similar properties in Table 1. C. minutissimum, C. singulare, and CN-1 are positive for tyrosine hydrolysis at 37°C. Unlike strain CN-1, C. minutissimum exhibits DNase activity (17). Colonies of strain CN-1 are dry, raised, rough, and pitted in nature, whereas colonies of C. singulare and C. minutissimum are circular, slightly convex, with entire margins, and of a creamy consistency. In addition, CN-1 produces black-pigmented colonies, suggesting that it is physiologically different from C. minutissimum and C. singulare.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics that differentiate CN-1 from other relevant fermenting, nonlipophilic Corynebacterium spp. encountered in human clinical specimensa

| Strain or species | Reaction in the following test:

|

Other trait(s) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate reduction | Urea hydrolysis | Esculin hydrolysis | Pyrazin amidase | Alkaline phosphatase | Acid produced from:

|

CAMP | ||||

| Glucose | Maltose | Sucrose | ||||||||

| CN-1 | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | (+) | − | Dry, pitted colony; strong adhesion to agar; black pigmented; glycogen + |

| C. durum | + | (v) | (v) | + | − | + | + | + | − | Adherence to agar |

| C. minutissimum | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | v | − | Tyrosine hydrolysis + |

| C. singulare | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | Tyrosine hydrolysis + |

| C. ulcerans | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | REV | Glycogen + |

| C. confusum | + | − | − | + | + | (+) | − | − | − | Tyrosine hydrolysis − |

| C. amycolatum | v | v | − | + | + | + | v | v | − | Mycolic acid − |

| C. argentoratense | − | − | − | + | v | + | − | − | − | Chymotrypsin + |

| C. coyleae | − | − | − | + | + | (+) | − | − | + | |

| C. diphtheriae | v | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | Cystinase + |

| C. falsenii | − | (+) | − | w | + | (+) | v | − | − | Yellowish |

| C. glucuronolyticum | v | v | v | + | v | + | v | + | + | β-Glucuronidase + |

| C. imitans | − | − | − | w | + | + | + | w | + | Tyrosine hydrolysis − |

| C. pseudotuberculosis | − | + | − | − | v | + | + | v | REV | Glycogen − |

| C. riegelii | − | + | − | v | v | − | (+) | − | − | |

| C. striatum | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | v | v | Tyrosine hydrolysis + |

| C. thomssenii | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | N-Acetylglucosaminidase + | |

| C. xerosis | v | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | Yellowish |

| R. dentocariosa | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | Adherence |

Data are from Funke and Bernard (6). −, negative; +, positive; v, variable reaction; w, weak reaction; REV, reverse CAMP reaction; parentheses indicate a delayed reaction.

In conclusion, phenotypic, biochemical, and molecular phylogenetic characterization of strain CN-1 suggests that it is probably a new species within the genus Corynebacterium. This report, along with Corynebacterium clones from prostatitis cases, calls attention to the growing recognition of Corynebacterium species as human pathogens and commensals. Indeed, the close relationship of the CN-1 rRNA sequence to that of a prostatitis-related uncultured organism raises that possibility (15). Even though strain CN-1 was not directly linked to the abortion in the study patient, the description of the strain will help other clinical microbiologists to distinguish this species from other Corynebacterium species recovered from the urogenital tract. The rRNA sequence from strain CN-1 will be a resource for the design of hybridization primers to detect this organism and its relatives. Additional isolates of this species may provide information about its ecological niche, clinical relevance, and potential role as an opportunistic pathogen in immunosuppressed patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Teresa Aspeslet and Lisa Baeten.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clarridge J E, Spiegel C A. Corynebacterium and miscellaneous irregular gram-positive rods, Erysipelothrix, and Gardnerella. In: Murray P R, et al., editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 357–378. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Funke G, Lucchini G M, Pfyffer G E, Marchiani M, von Graevenitz A. Characteristics of CDC group 1 and group 1-like coryneform bacteria isolated from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2907–2912. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2907-2912.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funke G, Lawson P A, Collins M D. Heterogeneity within human-derived Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) coryneform group ANF-1-like bacteria and description of Corynebacterium auris sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:735–739. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funke G, Lawson P A, Collins M D. Corynebacterium riegelii sp. nov., an unusual species isolated from female patients with urinary tract infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:624–627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.624-627.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funke G, Osorio C R, Frei R, Riegel P, Collins M D. Corynebacterium confusum sp. nov., isolated from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:1291–1296. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funke G, Bernard A K. Coryneform gram-positive rods. In: Murray P R, et al., editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 319–345. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janda W M. Corynebacterium species and the coryneform bacteria. Part I. New and emerging species in the genus Corynebacterium. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1998;20:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janda W M. Corynebacterium species and the coryneform bacteria. Part II. Current status of the CDC coryneform groups. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1998;20:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) interpretive standards (μg/ml) for organisms other than Haemophilus spp., Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Streptococcus spp. NCCLS document M7–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascual C, Lawson P A, Farrow J A E, Gimenez M N, Collins M D. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Corynebacterium based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:724–728. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riegel P, Ruimy R, Renaud F N, Freney J, Prevost G, Jehl F, Christen R, Monteil H. Corynebacterium singulare sp. nov., a new species for urease-positive strains related to Corynebacterium minutissimum. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1092–1096. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruimy R, Riegel P, Boiron P, Monteil H, Christen R. Phylogeny of the genus Corynebacterium deduced from analyses of small-subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:740–746. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swofford D L. PAUP∗. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods), version 4. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanner M A, Shoskes D, Shahed A, Pace N R. Prevalence of corynebacterial 16S rRNA sequences in patients with bacterial and “nonbacterial” prostatitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1863–1870. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1863-1870.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmermann O, Spröer C, Kroppenstedt R M, Fuchs E, Köchel H G, Funke G. Corynebacterium thomssenii sp. nov., a Corynebacterium with N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activity from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:489–494. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]