Abstract

Continuous spermatogenesis depends on the self-renewal and differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs). SSCs, the only male reproductive stem cells that transmit genetic material to subsequent generations, possess an inherent self-renewal ability, which allows the maintenance of a steady stem cell pool. SSCs eventually differentiate to produce sperm. However, in an in vitro culture system, SSCs can be induced to differentiate into various types of germ cells. Rodent SSCs are well defined, and a culture system has been successfully established for them. In contrast, available information on the biomolecular markers and a culture system for livestock SSCs is limited. This review summarizes the existing knowledge and research progress regarding mammalian SSCs to determine the mammalian spermatogenic process, the biology and niche of SSCs, the isolation and culture systems of SSCs, and the biomolecular markers and identification of SSCs. This information can be used for the effective utilization of SSCs in reproductive technologies for large livestock animals, enhancement of human male fertility, reproductive medicine, and protection of endangered species.

Keywords: culture, identification, isolation, male germline stem cell, spermatogonial stem cell, transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Spermatogenesis is the process by which spermatogonia, which originate from spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), divide and differentiate into spermatocytes, which further develop into spermatozoa/sperm. It is a complex and continuous process of cell differentiation, in which different stages are precisely timed and coregulated by a range of genes and hormones.1 SSCs are derived from gonocytes in the testes after birth; gonocytes originate from primordial germ cells at the embryonic stage.2 SSCs are the only specialized male reproductive stem cells that serve as carriers of genetic material to subsequent generations and are located on the basement membrane of the testicular seminiferous tubule epithelium.3

SSCs play a pivotal role in mammalian spermatogenesis. They are distinguished from other cells by their capability of maintaining a steady stem cell pool by self-renewal, and that for further differentiating into haploid sperm cells.4,5 The number of SSCs in mice testes is limited and difficult to determine; SSCs account for approximately 0.03% of all germ cells in the testes of mice.6 Numerous unresolved issues remain in the study of the mechanism and function of SSCs in culture. The present review aimed to summarize recent research advances in the biology, niche, culture system, biomolecular markers, and identification of mammalian SSCs. The detailed evaluation of these points is crucial for understanding the physiological and pathological mechanisms related to mammalian reproduction. It would also provide valuable insights into SSC applications in assisted reproduction and cell therapy.

THE SPERMATOGENIC PROCESS

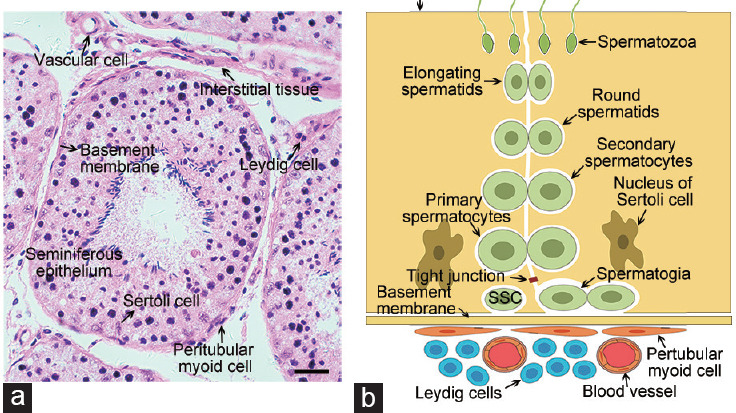

Testicular tissue is comprised of seminiferous tubules and interstitial tissue (Figure 1a). Cell types in the seminiferous tubules include spermatogonia, primary spermatocytes, secondary spermatocytes, spermatids, and Sertoli cells (Figure 1b and 2). During spermatogenesis, different types of spermatogenic cells are arranged in specific positions in the seminiferous tubules.7 Spermatogenesis originates from the differentiation of SSCs, which depends on hormonal regulation and cell signal transduction. The precise balance between the self-renewal and differentiation of SSCs is regulated by the SSCs themselves, epigenetic factors,8 and the SSC niche.9,10,11 The SSC niche12,13 is suggested to be comprised of Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, peritubular myoid cells, growth factors, immune cells, vascular cells, and the basement membrane. The SSC niche plays a pivotal role in the self-renewal and differentiation of SSCs14 by providing extrinsic factors for maintaining stem cell potential.15

Figure 1.

Composition of the SSC niche. (a) Histological cross-section of the seminiferous tubules from goat testes stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Scale bar = 25 μm. (b) Schematic diagram of the seminiferous tubules and interstitial tissue from mammalian testes. SSC: spermatogonial stem cell.

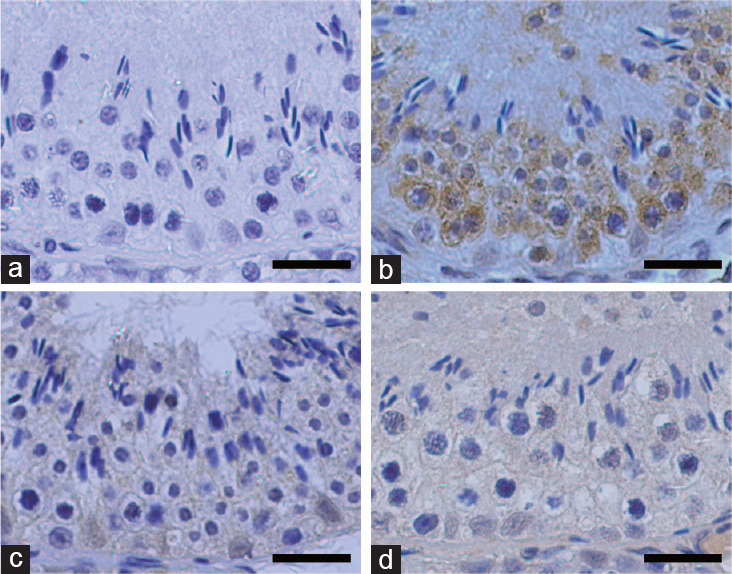

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of DDX4, SOX9, and WT1 in the seminiferous tubules of adult goat testes. (a) The negative control section used non-immune rabbit serum. (b) DDX4 localized in germ cells. (c) SOX9 and (d) WT1 localized in Sertoli cells. Scale bars = 25 μm. SOX9: SRY-related high mobility group-box gene 9; WT1: Wilms tumor protein 1; DDX4: DEAD-box polypeptide-4.

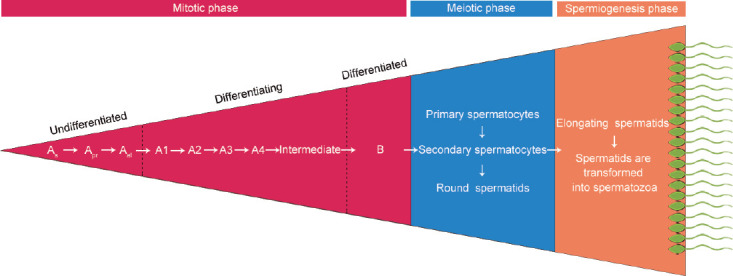

Spermatogenesis in mammals includes three phases:16 the mitotic phase, the meiotic phase, and spermiogenesis (Figure 3). The mitotic phase of spermatogenic development in rodents includes undifferentiated spermatogonia (Asingle [As], Apaired [Apr], and Aaligned [Aal]), differentiating spermatogonia (A1, A2, A3, A4, and intermediate), and differentiated spermatogonia (type B).17 The population of undifferentiated spermatogonia is heterogeneous; most studies have suggested that only As spermatogonia possess stem cell characteristics (characteristics of self-renewal and differentiation into Apr and Aal).18,19 Therefore, As spermatogonia have been defined as SSCs. However, some recent studies have suggested that both Apr and Aal populations show stem cell potential.20,21 The meiotic phase of spermatogenic development in rodents involves three types of germ cells: successive type of primary spermatocytes, secondary spermatocytes, and haploid spermatids. Spermatids are transformed into spermatozoa during the spermiogenesis phase. The spermatogenic process in humans is similar to that in rodents. In humans, however, spermatogonia are divided into three types: Adark, Apale, and type B.22 The transformation of SSCs into mature spermatozoa is vastly different across species. For instance, the duration of spermatogenesis in various mammals is as follows: 74 days in humans,23 35 days in mice,19 41 days in boars,24 57 days in stallions,25 63 days in cattle,26 and 47.7 days in goats.27

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the three phases of spermatogenesis in rodents. As: type Asingle spermatogonia; Apr: type Apaird spermatogonia; Aal: type Aaligned spermatogonia; intermediate: intermediate spermatogonia; B: type B spermatogonia.

ISOLATION OF SSCS

The number of SSCs in immature and adult testes is limited.6 Thus, the isolation and distinction of SSCs remain challenging. In immature testes, spermatogonia are the main cell type found in the seminiferous tubules. Therefore, immature testes are generally preferred for the isolation of SSCs. The optimal age of different animals for the isolation of their SSCs is as follows: 4.5 days to 7.5 days for mice;28 9 days for rats;29 5 months to 7 months for cattle;30 4 months for goats;31 and 1 month for pigs.32 Two-step enzymatic digestion, which was first proposed by Davis and Schuetz,33 is widely used for the isolation of SSCs from humans,34 mice,35 monkeys,36 sheep,37 pigs,38 and cattle39 (Table 1). In this approach, the testicular tissue is digested using collagenase and trypsin. The enzyme concentration and digestion time affect the activity and quantity of the collected SSCs.40

Table 1.

Culture conditions for spermatogonial stem cells in human, monkey, mouse, cattle, goat, sheep, and pig

| Subject, reference | Donor age | Isolation method | Enrichment method | Medium | Serum | Growth factors | Feeder cells | Identification method | Duration of culture (day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human, Sadri-Ardekani et al.108 | NA | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Differential plating | StemPro-34 serum-free medium | 10% FCS | 20 ng ml−1 EGF, 10 ng ml−1 GDNF, 10 ng ml−1 LIF | NA | Immunostaining | Approximately 196 |

| Human, Guo et al.109 | 22–35 years | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Differential plating + MACS for GPR125 | StemPro-34 serum-free medium | 2.5 mg ml−1 lipid-rich BSA, 1% FBS | 50 ng ml−1 GDNF, 20 ng ml−1 EGF, 10 ng ml−1 bFGF, 10 ng ml−1 LIF | NA | Immunostaining | Approximately 60 |

| Monkey, Langenstroth et al.110 | 3.7–4.6 years | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Differential plating | α-MEM | 10% FBS | NA | Somatic cells | Immunostaining | Approximately 11 |

| Mouse, Kubota et al.28 | 4.5–7.5 days | Two-step enzymatic digestion | MACS for Thy1 | α-MEM | 0.2% BSA | 40 ng ml−1 GDNF, 300 ng ml−1 GFRα1, 1 ng ml−1 bFGF | STO | Immunostaining | Approximately 180 |

| Mouse, Kanatsu-Shinohara et al.111 | 8 days | Two-step enzymatic digestion | MACA for CD9 | StemPro-34 serum-free medium | 3 mg ml−1 of lipid-rich BSA, 1:100 lipid mixture 1, 1:1000 lipoprotein-cholesterol concentrate | 20 ng ml−1 EGF, 10 ng ml−1 FGF2, 15 ng ml−1 GDNF | NA | Flow cytometry | Approximately 178 |

| Cattle, Oatley et al.93 | 4–5 months | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Percoll gradient + differential plating | α-MEM | 0.5% BSA | 20 ng ml−1 GDNF, 2 ng ml−1 FGF2, 100 ng ml−1 LIF | Bovine fetal fibroblasts | Immunostaining | Approximately 60 |

| Cattle, Herrid et al.30 | 5–7 months | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Differential plating | DMEM | 5% FBS | NA | NA | Immunostaining | NA |

| Goat, Ren et al.112 | 2–2.5 months | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Differential plating | DMEM | 5% FBS | 25 ng ml−1 EGF, 20 ng ml−1 PDGF-BB, 5 ng ml−1 bFGF | Sertoli cells | Immunostaining | Approximately 28 |

| Goat, Pramod and Mitra50 | 3–4 months | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Percoll gradient | DMEM | 10% FBS | NA | Sertoli cells | Immunostaining | Approximately 45 |

| Sheep, Binsila et al.37 | Prepubertal | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Differential plating | DMEM | 5% FBS | NA | NA | Immunostaining | NA |

| Sheep, Binsila et al.113 | Prepubertal | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Ficoll density gradient + differential plating | StemPro-34 serum-free medium | 5% FBS | 40 ng ml−1 GDNF, 20 ng ml−1 EGF, 100 ng ml−1 IGF1 | NA | Immunostaining | Approximately 36 |

| Pig, Goel et al.114 | 2–4 days | Two-step enzymatic digestion | Percoll gradient + differential plating | DMEM | 10% FBS | 10 µg ml−1 insulin | NA | Immunostaining | Approximately 7 |

| Pig, Zheng et al.115 | 7 days | Two-step enzymatic digestion | FACS for PLD6 | DMEM | 5% FBS + 5% KSR | 20 ng ml−1 GDNF, 40 ng ml−1 GFRα1, 10 ng ml−1 bFGF | NA | Immunostaining | Approximately 210 |

bFGF: basic fibroblast growth factor; BSA: bovine serum albumin; DMEM: Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; EGF: epidermal growth factor; FBS: fetal bovine serum; FCS: fetal calf serum; FGF2: fibroblast growth factor 2; GDNF: glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; GFRα1: glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor receptor alpha 1; IGF1: insulin-like growth factor 1; KSR: knockout serum replacement; LIF: leukemia inhibitory factor; MACS: magnetic-activated cell sorting; FACS: fluorescence-activated cell sorting; MEM: minimum essential medium; NA: not available; PDGF-BB: platelet-derived growth factor-BB; STO: SIM mouse embryonic fibroblasts; GPR: G-protein receptor; THY1: Thy1 cell surface antigen; CD9: CD9 molecule; PLD6: phospholipase D family, member 6

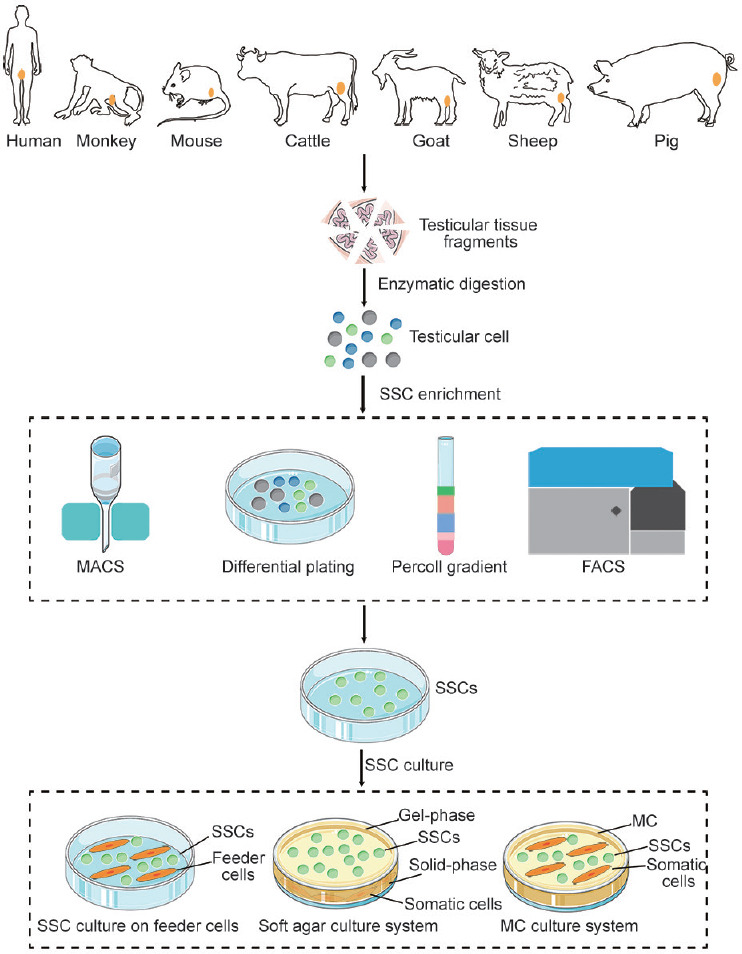

For further enrichment of SSCs, differential plating,41 Percoll gradient,41,42 magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS),43 or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)44 is typically performed (Figure 4). The theory behind the differential plating method is that the adhesion rates of SSCs and somatic cells are different. Somatic cells have a higher affinity for gelatin than SSCs. Compared to other enrichment methods, the differential plating method yields the best results for SSC enrichment, although it has a lower specificity for SSCs.45 Izadyar et al.46 used a Percoll gradient to concentrate a suspension of testis cells containing 25.5% bovine type A spermatogonia to 51%. This method is also widely used for the enrichment of SSCs from humans,47 pigs,48 sheep,49 goats,50 and monkeys.51 FACS and MACS yield SSCs with higher purity than the other methods. For instance, Liu et al.47 enriched human SSCs to an 86.7% concentration by FACS using the SSC surface marker octamer-binding transcription factor-4 (OCT4). Human SSCs were also purified by MACS using another SSC surface marker called integrin alpha 6 (ITGA6).44 However, the use of MACS and FACS is limited by specific SSC surface markers. SSC isolation and enrichment methods for livestock species have been developed; however, their development has occurred at a slower pace than SSC isolation and enrichment methods for other species, which may be attributable to species differences. Moreover, no unique and specific SSC molecular markers have been determined in livestock species.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of isolation, enrichment, and culture methods of SSCs. The testicular tissues is digested using the enzyme. Then, MACS, differential plating, Percoll gradient, or FACS is used for the enrichment of SSCs. In two-dimensional cell culture system, SSCs are cultured on feeder cells. Soft agar and MC are the most commonly used media in the three-dimensional cell culture system. SSC: spermatogonial stem cell; MACS: magnetic-activated cell sorting; FACS: fluorescence-activated cell sorting; MC: methylcellulose.

IDENTIFICATION OF SSCS

Biomolecular markers of SSCs

Currently, there are two methods for the identification of SSCs: (1) biomolecular marker-based identification (identification using multiple SSC markers) and (2) spermatogonial transplantation (SSC colonization of recipient testes). Thus far, the understanding of the morphological characteristics and markers of SSCs has not been comprehensive. SSC markers in mice have been intensively searched for; however, SSC markers in humans and certain livestock species have not been identified. Previously, human SSCs were identified using markers of rodent SSCs. However, studies have demonstrated that several mouse SSC markers used for the identification of human SSCs are also expressed in nongerm cells in the human testes.52,53 As previously mentioned, SSC markers differ between species (Table 2). OCT4 and ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 (UCHL1) have been successfully identified as shared markers among the SSCs of humans, mice, cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor receptor alpha 1 (GFRα1) is widely used for SSC identification in humans, monkey, mice, cattle, and pigs. Whether GFRα1 can be specifically localized in the SSCs of goats and sheep still requires further study. Currently, BMI1 proto-oncogene, polycomb ring finger (BMI1), cadherin 1 (CDH1), forkhead box O1 (FOXO1), nanos C2HC-type zinc finger 2 (NANOS2), integrin beta 1 (ITGB1), paired box 7 (PAX7), and RET proto-oncogene (RET) are unique SSC markers in mice. The specific expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) is only found in human SSCs. Furthermore, the expression of SSC markers in livestock species has been shown to be heterogeneous. As some markers are not unique to SSCs, it is necessary to simultaneously use multiple markers for the identification of SSCs in a species. Additionally, specific molecular markers need to be continuously discovered and canonically used to identify the SSCs of various species.

Table 2.

Overview of spermatogonial stem cell markers in human, monkey, mouse, cattle, goat, sheep, and pig

| Marker | Human | Monkey | Mouse | Cattle | Goat | Sheep | Pig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI1 | ND | ND | Komai et al.116 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| CD9 | Zohni et al.117 | ND | Kanatsu-Shinohara et al.118 | Cai et al.119 | Kaul et al.120 | ND | ND |

| CDH1 | ND | ND | Tokuda et al.121 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| DBA | ND | ND | ND | Izadyar et al.122 | ND | Borjigin et al.123 | Goel et al.114 |

| FOXO1 | ND | ND | Goertz et al.124 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| FGFR3 | von Kopylow et al.125 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| GFRα1 | He et al.43 | Hermann et al.126 | Meng et al.70 | Oatley et al.127 | ND | ND | Lee et al.128 |

| GPR125 | He et al.43 | ND | Seandel et al.129 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| ID4 | Sachs et al.130 | ND | Helsel et al.131 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| ITGB1 | ND | ND | Kanatsu-Shinohara et al.132 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| ITGA6 | Valli et al.44 | ND | Shinohara et al.133 | De Barros et al.134 | ND | ND | ND |

| LIN28 | Aeckerle et al.135 | Aeckerle et al.135 | Zheng et al.136 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| NANOS2 | ND | ND | Suzuki et al.137 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| NGN3 | ND | Hermann et al.138 | Yoshida et al.42 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| OCT4 | Bhartiya et al.139 | ND | Pesce et al.140 | Borjigin et al.123 | Pramod and Mitra50 | Qasemi-Panahi et al.141 | Goel et al.114 |

| PAX7 | ND | ND | Aloisio et al.142 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| PLZF | ND | Hermann et al.126 | Costoya et al.143 | Reding et al.144 | ND | Borjigin et al.123 | Goel et al.114 |

| RET | ND | ND | Naughton et al.145 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| SALL4 | Eildermann et al.146 | Eildermann et al.146 | Hobbs et al.147 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| SOHLH1 | ND | Ramaswamy et al.148 | Ballow et al.149 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| THY1 | He et al.43 | ND | Kubota et al.28 | Reding et al.144 | Abbasi et al.150 | ND | ND |

| UCHL1 | He et al.43 | ND | Kwon et al.151 | Herrid et al.152 | Heidari et al.153 | Rodriguez-Sosa et al.49 | Luo et al.154 |

| UTF1 | ND | ND | van Bragt et al.155 | ND | ND | ND | Lee et al.156 |

BMI1: BMI1 proto-oncogene, polycomb ring finger; CD9: CD9 molecule; CDH1: cadherin 1; DBA: dolichos biflorus agglutinin; FOXO1: forkhead box O1; FGFR3: fibroblast growth factor receptor 3; GFRα1: glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor receptor alpha 1; GPR125: G-protein receptor 125; ID4: inhibitor of differentiation 4; ITGB1: integrin beta 1; ITGA6: integrin alpha 6; LIN28: Lin-28 homolog A; NANOS2: nanos C2HC-type zinc finger 2; ND: not determined; NGN3: neurogenin 3; OCT4: octamer-binding transcription factor-4; PAX7: paired box 7; PLZF: promyelocytic leukemia zinc-finger; RET: RET proto-oncogene; SALL4: spalt like transcription factor 4; SOHLH1: spermatogenesis and oogenesis-specific basic helix-loop-helix 1; THY1: Thy1 cell surface antigen; UCHL1: ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1; UTF1: undifferentiated embryonic cell transcription factor 1

Spermatogonial transplantation

Spermatogonial transplantation, which can be divided into autologous transplantation, allogeneic transplantation, and xenotransplantation, depending on the recipient, has been demonstrated to restore the fertility of male individuals with damaged testes. The spermatogonial transplantation technique was developed to identify SSCs in 1994.54 Endogenous germ cells must be eliminated to ensure that only donor-derived sperm are produced after transplantation.55 As such, recipient mice are treated with busulfan (1,4-butanediol dimethanesulfonate) to deplete endogenous SSCs. Spermatogenic colonies derived from donor germ cells are identified in recipient testes through the expression of reporter genes. The donor-derived germ cells are labeled with β-galactosidase, green fluorescent protein, or other fluorescent proteins. Thereafter, they are transplanted into the seminiferous tubules of recipient mice. Busulfan treatment is known to deplete endogenous germ cells in a dose-dependent manner. However, busulfan has also been reported to have side effects, including toxicity, in recipient animals and may damage organs and Sertoli cells.56 Hence, specific mutant mice lacking spermatogenesis can be used as recipients. For instance, knocking out NANOS2 in mice57 and pigs58 has been shown to reduce the number of endogenous germ cells; these animals can then be employed as ideal transplant recipients for SSCs. After microinjection, the donor SSCs colonize the seminiferous tubules of the recipient. Consequently, spermatogenesis is restored. Fertilization of eggs by donor-derived spermatozoa can lead to the production of fertile offspring.59 Therefore, the germ cell transplantation technique can be used for SSC identification. The success rate of homologous transplantation is higher than that of other types of transplantation. Ablation of endogenous germ cells is easier in rodents than that in livestock. To obtain more effective and reliable recipient males, the ablation of endogenous germ cells in livestock needs better strategies. SSC transplantation methods and recipient males for livestock SSC transplantation still need to be further explored. Currently, the colonization efficiency of SSCs in recipient testes is approximately 12.5%.60 The reason for this low colonization efficiency after transplantation is unclear. Thus, it is important to elucidate the underlying mechanism and improve the colonization efficiency in SSC transplantation.

Complete spermatogenesis was observed after cross-species mouse-hamster61 and mouse-rat62 transplantations, and healthy offspring were produced. However, whether SSCs from nonrodent species could be identified by transplantation has been questioned.63 In 2002, Nagano et al.64 transplanted human SSCs into immunodeficient mice for the first time. Human SSCs were found to colonize the seminiferous tubules in mice and survived there for up to 6 months.64 However, spermatogonial development did not proceed to the meiotic phase. The absence in the mice testes, of certain unique growth factors that are necessary for the spermatogenic process in nonrodent species may explain the inability of mice testes to support complete spermatogenesis following transplantation of SSCs from these species. SSCs from several nonrodent species have been transplanted into the testes of mice. SSC transplantation may be used as a breeding tool for livestock. However, complete spermatogenesis was observed only in the case of SSC transplantation from monkeys and sheep (Table 3). The reason for these interspecies differences may be the requirement for blood–testis barrier and Sertoli cells for the colonization of SSCs in recipient testes. The immunoprotection against germ cells offered by Sertoli cells ensures normal spermatogenesis. The number of Sertoli cells in the seminiferous tubules has also been demonstrated to affect the colonization efficiency of transplanted SSCs in mice.65 Sertoli cells are a category of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) that have begun to differentiate.66 Therefore, co-transplanting SSCs and MSCs has been shown to significantly improve the colonization efficiency of SSCs.67 Co-transplantation of Sertoli cells and SSCs has also been reported to improve the efficiency of SSC transplantation in recipient testes.68,69 Before SSC transplantation, SSCs need to expand in vitro to reach a sufficient number. SSC culture conditions of rodents have been used to culture in livestock SSCs. Obviously, expansion efficiency of livestock SSCs in vitro is still lower than that of rodents. There are still difficulties in SSC transplantation for livestock.

Table 3.

Spermatogonial transplantation in human, mouse, monkey, cattle, goat, sheep, and pig

| Donor species | Transplant type | Recipient species | Spermatogenesis of recipient | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Xenotransplantation | Mouse | Incomplete | Izadyar et al.122 |

| Mouse | Autologous | Mouse | Complete | Koruji et al.157 |

| Mouse | Allogeneic | Mouse | Complete | Ma et al.158 |

| Monkey | Autologous | Monkey | Complete | Hermann et al.51 |

| Monkey | Allogeneic | Monkey | Complete | Hermann et al.51 |

| Monkey | Xenotransplantation | Mouse | Complete | Ntemou et al.97 |

| Cattle | Autologous | Cattle | Complete | Izadyar et al.46 |

| Cattle | Allogeneic | Cattle | Complete | Izadyar et al.46 |

| Cattle | Xenotransplantation | Mouse | Incomplete | Izadyar et al.159 |

| Goat | Allogeneic | Goat | Complete | Honaramooz et al.31 |

| Goat | Xenotransplantation | Mouse | Incomplete | Shirazi et al.160 |

| Sheep | Allogeneic | Sheep | Complete | Herrid et al.68 |

| Sheep | Xenotransplantation | Mouse | Complete | Pukazhenthi et al.98 |

| Pig | Autologous | Pig | Not detected | Honaramooz et al.32 |

| Pig | Allogeneic | Pig | Complete | Zeng et al.161 |

| Pig | Xenotransplantation | Mouse | Incomplete | Dobrinski et al.162 |

CULTURE OF SSCS

The limited number of SSCs in the testes hampers biological and applied research on these cells. However, this obstacle may be overcome by establishing an in vitro culture system that maintains the stem cell potential of SSCs. The culture of SSCs is a challenge at the outset, as growth factors, serum, and the feeder layer may affect the SSC state during in vitro culture (Table 1).

In 2000, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) was demonstrated to regulate the fate of undifferentiated spermatogonia in mice,70 even though it was initially identified as a neurotrophic factor. Currently, GDNF and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) are known to be essential factors for the maintenance of SSC self-renewal in culture,71,72,73 with GDNF having been shown to regulate the fate of SSCs in a dose-dependent manner.70 Wang et al.74 suggested that a high concentration of GDNF (20 ng ml−1) is conducive to the early proliferation of mouse SSCs; conversely, a low concentration of GDNF (4 ng ml−1) was conducive to stable culture in the later stage of SSC development. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) has also been reported to inhibit the differentiation of stem cells in vitro, with 15 mg ml−1 LIF promoting the stable proliferation of SSCs.75 Wu et al.76 demonstrated that the addition of 25 mg ml−1 basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and other factors could continuously promote the proliferation of mouse SSCs in vitro for more than 120 days.

In addition to growth factors, fetal bovine serum (FBS) has been shown to be crucial for the survival and self-renewal of SSCs in vitro (Table 1). Goat SSCs were cultured under different serum concentrations (1%, 5%, 10%, and 15%).77 After 7 days, the number of goat SSC colonies was observed to be higher in the presence of 1% serum compared to the number of colonies in the presence of 5%, 10%, and 15% serum.77 A higher concentration of serum was found to inhibit the proliferation of SSCs.77 However, various undefined factors in FBS may affect the culture status of SSCs in vitro and induce their differentiation. Therefore, knockout serum replacement (KSR) has been attempted for culturing SSCs in vitro. SSCs from immature bovine testes have also been cultured in serum-free medium containing GDNF, bovine leukemia inhibitory factor (bLIF), and KSR,78 with SSC colonies being formed and identified based on morphological characteristics and molecular markers.

Feeder layer cells provide a variety of necessary cytokines for the proliferation of SSCs. Various feeder layer cells, including mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder cells,28,79 SIM mouse embryonic fibroblasts (STO) feeder cells,80,81 yolk sac-derived endothelial cells (C166),82 and Sertoli cells,50,83 have been applied in the culture of SSCs to promote their proliferation. Among them, the MEF feeder layer cells exerted the best effect on the colonization and proliferation of SSCs.84 The preparation of feeder layer cells for subculture is a tedious process; therefore, a Matrigel-based feeder-free culture system was developed.85 This feeder-free culture system was able to maintain the biological function of SSCs in an in vitro culture (Table 1). For the culture of SSCs from livestock, the commonly used feeder layer cells are their own Sertoli cells.50,83 However, Sertoli cells secrete certain growth factors that promote the differentiation of SSCs; therefore, the long-term culture of SSCs in vitro cannot be sustained.

To simulate the growth environment of SSCs in vivo, a three-dimensional cell culture system was developed. To this end, various types of cells in the seminiferous tubules were separated and implanted into a semi-solid medium to maintain the niche function. Currently, soft agar and methylcellulose (MC) are the most commonly used three-dimensional cell culture media Figure 4. Mouse SSCs were cultured for 15 days in a soft agar culture system, and specific markers of haploid sperm cells were found to be expressed by them.86 Similarly, SSCs from prepubertal male testes were cultured in MC and haploid sperm-like cells were subsequently identified.87 Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, and SSCs from rats were also co-cultured in the extracellular matrix to establish an in vitro toxicity test system for rat testes.88 The three-dimensional culture system provides a research model for communication and interactions between cells in the body. However, it cannot sustain the culture of SSCs for a long period and is incapable of recycling all cells.

Culture systems for neonate SSCs differ from those for adult SSCs.39 Using a neonatal culture system to culture SSCs from adult mammals revealed that the system was unable to maintain the SSCs for a long period.39,78 Adult bovine SSCs were cultured for a maximum of three passages, and the stem cell potential of SSCs derived from immature bovine testes was greater than that of stem cells derived from adult bovine testes.78 It appears that the successful establishment of an SSC culture system depends on the age of the animal (neonate or adult). SSCs from rats, hamsters, and rabbits were established using species-specific culture components.82,89,90,91 SSCs from pigs,83,92 goats,50 and cattle39,78,93 were also cultured successfully in vitro. However, most of these studies only carried out a short-term culture. The long-term culture of SSCs from livestock species is still in its infancy.94 Some reports have suggested that SSCs from pigs83 and cattle78 have been successfully cultured in vitro for a prolonged period. However, long-term culture systems for SSCs from other livestock have not been established, which may be due to the lack of proper SSC culture conditions and necessary cytokines for proliferation. The culture conditions for rodent SSCs cannot be fully applied to SSCs from livestock species.95 Although reports have indicated that SSCs or germline stem cells could be continuously cultured over months, the stem cell potential of these cultured cells remains controversial. Therefore, it is necessary to rigorously evaluate the function of SSCs after long-term culture. Transplantation of SSCs cultured into the testes of mice lacking endogenous germ cells was reported to produce offspring originating from donor SSCs, indicating that SSCs cultured in vitro are capable of differentiating into sperm in vivo, leading to the production of offspring.96 Currently, only SSCs from monkeys97 and sheep98 cultured in vitro have been demonstrated to exhibit complete spermatogenesis after transplantation into immunodeficient mice. The establishment of an in vitro long-term culture system for livestock SSCs would help to further elucidate the biology and application of SSCs. Thus, further study of the conditions for long-term in vitro culture of livestock SSCs is urgently required.

SSC fates are also regulated by epigenetic factors. For epigenetic factors, DNA methylation, histone methylation, and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are involved in regulation of SSC fates. DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3-like (DNMT3L; DNA methylation regulator) precisely regulates the proliferation and quiescence of SSCs.99 Tet oncogene 1 (TET1) participates in DNA methylation and histone modification to regulate SSC self-renewal.100 NcRNAs, as the novel epigenetic regulator, play crucial roles in regulating SSC fates. Long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) transcription is important for the self-renewal of SSCs. In the testis, lncRNA AK015322, mainly expressed in SSCs, regulates SSC proliferation by competitively binding miR-19b-3p and reducing the inhibitory effect of miR-19b-3p on ETS translocation variant 5 (Etv5).101 Li et al.102 have demonstrated that circular RNAs (circRNAs) play a role in mammalian SSCs. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a kind of nonprotein-coding short sequence RNA. He et al.103 reported for the first time that miRNA-20 and miRNA-106a are highly and specifically expressed in SSCs of mice, which promoted SSC proliferation and DNA synthesis. And miR-31 regulated meiosis of SSCs by targeting stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8 (Stra8) in vivo and in vitro to inhibit spermatogenesis.104 Huang et al.105 reported that miR-100 is mainly expressed in mouse SSCs, which indirectly regulated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) to promote SSCs proliferation. By isolating high-purity SSCs, Zhang et al.106 found that P-element-induced wimpy testis (PIWI)-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) account for 47% of the total number of small RNAs. Dong et al.107 found that ubiquitin-like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1 (Uhrf1) regulates retrotransposon silencing in male germ cells and cooperates with the PIWI pathway during spermatogenesis. LncRNAs, circRNAs, miRNAs, and piRNAs have formed complicated regulatory networks to modulate the SSCs fate. However, only a small number of ncRNAs have been verified functionally. It is very urgent to further uncover the regulatory effect of more ncRNAs (especially piRNAs and circRNAs) on SSC fates.

CONCLUSIONS

The unique biological characteristics of SSCs determine their importance in spermatogenesis. Any biological dysfunction in SSCs can cause male infertility. Investigation of the methods of isolation, identification, and culture of SSCs would help us better understand the processes of normal spermatogenesis and male infertility. Several SSC markers have been identified in rodents. There are numerous differences in spermatogenic processes between rodents and nonrodents; however, certain SSC markers and features of spermatogenesis are conserved among species. For the identification of SSCs from livestock, the source and quality of antibodies used are critical. Many SSC antibodies have limited specificity in livestock, and there are currently no specific antibodies against SSCs of various livestock species.

Researchers are encouraged to devote more attention to conduct detailed research into the regulatory effects of specific marker genes on SSC fates and spermatogenesis in different livestock species, which is currently lacking. Currently, research on spermatogenesis in livestock is limited and lacks depth. There have been no recent significant breakthroughs in the field of livestock SSCs and spermatogenic processes. The long-term culture of SSCs in vitro to produce sperm provides a novel method for the production of transgenic livestock. In addition, SSCs of superior livestock can be cultured in vitro and then transplanted into the testis of recipient, which can produce a large number of sperm carrying superior livestock genes for fertilization and promote the reproduction of superior livestock. However, the feasibility, safety, and bioethics of applying this technology have yet to be considered. Currently, our knowledge of SSC biology is still limited, and we have not fully developed the full potential of SSCs in vitro. Thus, it is necessary to further explore the role of SSCs in reproductive biology. A deeper understanding of the similarities and differences between the reproductive biology of various mammals would be conducive to the development of SSC culture and transplantation and applications of SSCs in human medicine, livestock improvement, and protection of endangered species.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

HMX was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. HMX, YJR, FR, YL, TYF, ZW, YQD, and LKZ performed the literature search and data analysis. JHH helped to revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31672425).

REFERENCES

- 1.Neto FT, Bach PV, Najari BB, Li PS, Goldstein M. Spermatogenesis in humans and its affecting factors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;59:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLean DJ, Friel PJ, Johnston DS, Griswold MD. Characterization of spermatogonial stem cell maturation and differentiation in neonatal mice. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:2085–91. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlatt S. Spermatogonial stem cell preservation and transplantation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;187:107–11. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Rooij DG, Grootegoed JA. Spermatogonial stem cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:694–701. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mäkelä JA, Hobbs RM. Molecular regulation of spermatogonial stem cell renewal and differentiation. Reproduction. 2019;158:R169–87. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagelenbosch RA, de Rooij DG. A quantitative study of spermatogonial multiplication and stem cell renewal in the C3H/101 F1 hybrid mouse. Mutat Res. 1993;290:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90159-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Rooij DG. The nature and dynamics of spermatogonial stem cells. Development. 2017;144:3022–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.146571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou F, Chen W, Jiang Y, He Z. Regulation of long non-coding RNAs and circular RNAs in spermatogonial stem cells. Reproduction. 2019;158:R15–25. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie T, Spradling AC. A niche maintaining germ line stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Science. 2000;290:328–30. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tran J, Brenner TJ, DiNardo S. Somatic control over the germline stem cell lineage during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Nature. 2000;407:754–7. doi: 10.1038/35037613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiger AA, White-Cooper H, Fuller MT. Somatic support cells restrict germline stem cell self-renewal and promote differentiation. Nature. 2000;407:750–4. doi: 10.1038/35037606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann MC. Gdnf signaling pathways within the mammalian spermatogonial stem cell niche. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;288:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Rooij DG. The spermatogonial stem cell niche. Microsc Res Tech. 2009;72:580–5. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostereva N, Hofmann MC. Regulation of the spermatogonial stem cell niche. Reprod Domest Anim. 2008;43:386–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oatley JM, Brinster RL. The germline stem cell niche unit in mammalian testes. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:577–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Kimura T, Ijiri TW, Isobe T, Asada N, et al. Mili, a mammalian member of piwi family gene, is essential for spermatogenesis. Development. 2004;131:839–49. doi: 10.1242/dev.00973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermo L, Pelletier RM, Cyr DG, Smith CE. Surfing the wave, cycle, life history, and genes/proteins expressed by testicular germ cells.Part 1: background to spermatogenesis, spermatogonia, and spermatocytes. Microsc Res Tech. 2010;73:241–78. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huckins C. The spermatogonial stem cell population in adult rats. 3. Evidence for a long-cycling population. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1971;4:335–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1971.tb01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oakberg E. A new concept of spermatogonial stem-cell renewal in the mouse and its relationship to genetic effects. Mutat Res. 1971;11:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(71)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa T, Nabeshima YI, Yoshida S. Functional identification of the actual and potential stem cell compartments in mouse spermatogenesis. Dev Cell. 2007;12:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hara K, Nakagawa T, Enomoto H, Suzuki M, Yamamoto M, et al. Mouse spermatogenic stem cells continually interconvert between equipotent singly isolated and syncytial states. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:658–72. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amann R, Howards S. Daily spermatozoal production and epididymal spermatozoal reserves of the human male. J Urol. 1980;124:211–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell LD, Ettlin RA, Hikim AP, Clegg ED. Histological and histopathological evaluation of the testis. Int J Androl. 1993;16:83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almeida FF, Leal MC, França LR. Testis morphometry, duration of spermatogenesis, and spermatogenic efficiency in the wild boar (Sus scrofa scrofa) Biol Reprod. 2006;75:792–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson L, Blanchard T, Varner D, Scrutchfield W. Factors affecting spermatogenesis in the stallion. Theriogenology. 1997;48:1199–216. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(97)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hochereau MT, Courot M, Ortavant R, Claire B, Boivineau L, et al. [Labelling of germ cells in the ram and in the bull by injection of tritiated thymidine in the spermatic artery] Ann Biol Anim Bioch Biophys. 1964;4:157–61. [Article in French] [Google Scholar]

- 27.França L, Becker-Silva S, Chiarini-Garcia H. The length of the cycle of seminiferous epithelium in goats (Capra hircus) Tissue Cell. 1999;31:274–80. doi: 10.1054/tice.1999.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Growth factors essential for self-renewal and expansion of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16489–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407063101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dym M, Jia MC, Dirami G, Price JM, Rabin SJ, et al. Expression of c-kit receptor and its autophosphorylation in immature rat type A spermatogonia. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:8–19. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrid M, Vignarajan S, Davey R, Dobrinski I, Hill JR. Successful transplantation of bovine testicular cells to heterologous recipients. Reproduction. 2006;132:617–24. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Honaramooz A, Behboodi E, Megee SO, Overton SA, Galantino-Homer H, et al. Fertility and germline transmission of donor haplotype following germ cell transplantation in immunocompetent goats. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1260–4. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.018788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Honaramooz A, Megee SO, Dobrinski I. Germ cell transplantation in pigs. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:21–8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis J, Schuetz A. Separation of germinal cells from immature rat testes by sedimentation at unit gravity. Exp Cell Res. 1975;91:79–86. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(75)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moraveji SF, Esfandiari F, Sharbatoghli M, Taleahmad S, Nikeghbalian S, et al. Optimizing methods for human testicular tissue cryopreservation and spermatogonial stem cell isolation. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:613–21. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermann BP, Cheng K, Singh A, Roa-De La Cruz L, Mutoji KN, et al. The mammalian spermatogenesis single-cell transcriptome, from spermatogonial stem cells to spermatids. Cell Rep. 2018;25:1650–67.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim YH, Kang HG, Kim BJ, Jung SE, Karmakar PC, et al. Enrichment and in vitro culture of spermatogonial stem cells from pre-pubertal monkey testes. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;14:557–66. doi: 10.1007/s13770-017-0058-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Binsila KB, Selvaraju S, Ghosh SK, Parthipan S, Archana SS, et al. Isolation and enrichment of putative spermatogonial stem cells from ram (Ovis aries) testis. Anim Reprod Sci. 2018;196:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2018.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han SY, Gupta MK, Uhm SJ, Lee HT. Isolation and in vitro culture of pig spermatogonial stem cell. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2009;22:187–93. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujihara M, Kim SM, Minami N, Yamada M, Imai H. Characterization and in vitro culture of male germ cells from developing bovine testis. J Reprod Dev. 2011;57:355–64. doi: 10.1262/jrd.10-185m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zou K, Hou L, Sun K, Xie W, Wu J. Improved efficiency of female germline stem cell purification using fragilis-based magnetic bead sorting. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:2197–204. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heidari B, Gifani M, Shirazi A, Zarnani AH, Baradaran B, et al. Enrichment of undifferentiated type A spermatogonia from goat testis using discontinuous percoll density gradient and differential plating. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2014;6:94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida S, Sukeno M, Nabeshima YI. A vasculature-associated niche for undifferentiated spermatogonia in the mouse testis. Science. 2007;317:1722–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1144885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He Z, Kokkinaki M, Jiang J, Dobrinski I, Dym M. Isolation, characterization, and culture of human spermatogonia. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:363–72. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.078550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valli H, Sukhwani M, Dovey SL, Peters KA, Donohue J, et al. Fluorescence-and magnetic-activated cell sorting strategies to isolate and enrich human spermatogonial stem cells. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:566–80.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herrid M, Davey RJ, Hutton K, Colditz IG, Hill JR. A comparison of methods for preparing enriched populations of bovine spermatogonia. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21:393–9. doi: 10.1071/rd08129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Izadyar F, Den Ouden K, Stout T, Stout J, Coret J, et al. Autologous and homologous transplantation of bovine spermatogonial stem cells. Reproduction. 2003;126:765–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu S, Tang Z, Xiong T, Tang W. Isolation and characterization of human spermatogonial stem cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:141. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi R, Bai Y, Li S, Wei H, Zhang X, et al. Characteristics of spermatogonial stem cells derived from neonatal porcine testis. Andrologia. 2015;47:765–78. doi: 10.1111/and.12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez-Sosa JR, Dobson H, Hahnel A. Isolation and transplantation of spermatogonia in sheep. Theriogenology. 2006;66:2091–103. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pramod RK, Mitra A. In vitro culture and characterization of spermatogonial stem cells on Sertoli cell feeder layer in goat (Capra hircus) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31:993–1001. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0277-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hermann BP, Sukhwani M, Winkler F, Pascarella JN, Peters KA, et al. Spermatogonial stem cell transplantation into rhesus testes regenerates spermatogenesis producing functional sperm. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:715–26. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kossack N, Terwort N, Wistuba J, Ehmcke J, Schlatt S, et al. A combined approach facilitates the reliable detection of human spermatogonia in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:3012–25. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng Y, Thomas A, Schmidt CM, Dann CT. Quantitative detection of human spermatogonia for optimization of spermatogonial stem cell culture. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2497–511. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brinster RL, Zimmermann JW. Spermatogenesis following male germ-cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11298–302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oatley JM. Recent advances for spermatogonial stem cell transplantation in livestock. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2017;30:44–9. doi: 10.1071/RD17418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhartiya D, Anand S. Effects of oncotherapy on testicular stem cells and niche. Mol Hum Reprod. 2017;23:654–5. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gax042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suzuki A, Tsuda M, Saga Y. Functional redundancy among Nanos proteins and a distinct role of Nanos2 during male germ cell development. Development. 2007;134:77–83. doi: 10.1242/dev.02697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park KE, Kaucher AV, Powell A, Waqas MS, Sandmaier SE, et al. Generation of germline ablated male pigs by CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the NANOS2 gene. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40176. doi: 10.1038/srep40176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brinster RL, Avarbock MR. Germline transmission of donor haplotype following spermatogonial transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11303–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagano MC. Homing efficiency and proliferation kinetics of male germ line stem cells following transplantation in mice. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:701–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.016352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ogawa T, Dobrinski I, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Xenogeneic spermatogenesis following transplantation of hamster germ cells to mouse testes. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:515–21. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clouthier DE, Avarbock MR, Maika SD, Hammer RE, Brinster RL. Rat spermatogenesis in mouse testis. Nature. 1996;381:418–21. doi: 10.1038/381418a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dobrinski I. Germ cell transplantation and testis tissue xenografting in domestic animals. Anim Reprod Sci. 2005;89:137–45. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagano M, Patrizio P, Brinster RL. Long-term survival of human spermatogonial stem cells in mouse testes. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:1225–33. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oatley MJ, Racicot KE, Oatley JM. Sertoli cells dictate spermatogonial stem cell niches in the mouse testis. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:639–45. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.087320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gong D, Zhang C, Li T, Zhang J, Zhang N, et al. Are Sertoli cells a kind of mesenchymal stem cells? Am J Transl Res. 2017;9:1067–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kadam P, Ntemou E, Baert Y, Van Laere S, Van Saen D, et al. Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells improves spermatogonial stem cell transplantation efficiency in mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:317. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herrid M, Olejnik J, Jackson M, Suchowerska N, Stockwell S, et al. Irradiation enhances the efficiency of testicular germ cell transplantation in sheep. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:898–905. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.078279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Morimoto H, Shinohara T. Fertility of male germline stem cells following spermatogonial transplantation in infertile mouse models. Biol Reprod. 2016;94:112. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.137869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meng X, Lindahl M, Hyvönen ME, Parvinen M, de Rooij DG, et al. Regulation of cell fate decision of undifferentiated spermatogonia by GDNF. Science. 2000;287:1489–93. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ishii K, Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. FGF2 mediates mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal via upregulation of Etv5 and Bcl6b through MAP2K1 activation. Development. 2012;139:1734–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.076539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Braydich-Stolle L, Nolan C, Dym M, Hofmann MC. Role of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in germ-line stem cell fate. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1061:94–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1336.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shirazi MS, Heidari B, Shirazi A, Zarnani AH, Jeddi-Tehrani M, et al. Morphologic and proliferative characteristics of goat type a spermatogonia in the presence of different sets of growth factors. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31:1519–31. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0301-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang P, Zheng Y, Li Y, Shang H, Li GX, et al. Effects of testicular interstitial fluid on the proliferation of the mouse spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. Zygote. 2014;22:395–403. doi: 10.1017/S0967199413000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Momeni-Moghaddam M, Matin MM, Boozarpour S, Sisakhtnezhad S, Mehrjerdi HK, et al. A simple method for isolation, culture, and in vitro maintenance of chicken spermatogonial stem cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2014;50:155–61. doi: 10.1007/s11626-013-9685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu Z, Falciatori I, Molyneux LA, Richardson TE, Chapman KM, et al. Spermatogonial culture medium: an effective and efficient nutrient mixture for culturing rat spermatogonial stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:77–86. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.072645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bahadorani M, Hosseini S, Abedi P, Hajian M, Hosseini S, et al. Short-term in-vitro culture of goat enriched spermatogonial stem cells using different serum concentrations. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29:39–46. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9687-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kitamura Y, Ikeda S, Minami N, Yamada M, Imai H. Long-term culture of undifferentiated spermatogonia isolated from immature and adult bovine testes. Mol Reprod Dev. 2018;85:236–49. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Azizi H, Conrad S, Hinz U, Asgari B, Nanus D, et al. Derivation of pluripotent cells from mouse SSCs seems to be age dependent. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:8216312. doi: 10.1155/2016/8216312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oatley JM, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor regulation of genes essential for self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells is dependent on Src family kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25842–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703474200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mohamadi S, Movahedin M, Koruji S, Jafarabadi MA, Makoolati Z. Comparison of colony formation in adult mouse spermatogonial stem cells developed in Sertoli and STO coculture systems. Andrologia. 2012;44:431–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2011.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kubota H, Wu X, Goodyear SM, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and endothelial cells promote self-renewal of rabbit germ cells with spermatogonial stem cell properties. FASEB J. 2011;25:2604–14. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-175802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang P, Chen X, Zheng Y, Zhu J, Qin Y, et al. Long-term propagation of porcine undifferentiated spermatogonia. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26:1121–31. doi: 10.1089/scd.2017.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Azizi H, Hamidabadi HG, Skutella T. Differential proliferation effects after Short-Term cultivation of mouse spermatogonial stem cells on different feeder layers. Cell J. 2019;21:186. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2019.5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Choi NY, Park YS, Ryu JS, Lee HJ, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, et al. A novel feeder-free culture system for expansion of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Mol Cells. 2014;37:473. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stukenborg JB, Wistuba J, Luetjens CM, Elhija MA, Huleihel M, et al. Coculture of spermatogonia with somatic cells in a novel three-dimensional soft-agar-culture-system. J Androl. 2008;29:312–29. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.002857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abofoul-Azab M, AbuMadighem A, Lunenfeld E, Kapelushnik J, Shi Q, et al. Development of postmeiotic cells in vitro from spermatogonial cells of prepubertal cancer patients. Stem Cells Dev. 2018;27:1007–20. doi: 10.1089/scd.2017.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang X, Wang L, Zhang X, Ren L, Shi W, et al. The use of knockout serum replacement (KSR) in three dimensional rat testicular cells co-culture model: an improved male reproductive toxicity testing system. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;106:487–95. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hamra FK, Chapman KM, Nguyen DM, Williams-Stephens AA, Hammer RE, et al. Self renewal, expansion, and transfection of rat spermatogonial stem cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17430–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508780102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ryu B-Y, Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Conservation of spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal signaling between mouse and rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14302–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506970102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Muneto T, Lee J, Takenaka M, Chuma S, et al. Long-term culture of male germline stem cells from hamster testes. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:611–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.065615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zheng Y, Tian X, Zhang Y, Qin J, An J, et al. In vitro propagation of male germline stem cells from piglets. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:945–52. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0031-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Oatley MJ, Kaucher AV, Yang QE, Waqas MS, Oatley JM. Conditions for long-term culture of cattle undifferentiated spermatogonia. Biol Reprod. 2016;95:14. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.116.139832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.González R, Dobrinski I. Beyond the mouse monopoly: studying the male germ line in domestic animal models. ILAR J. 2015;56:83–98. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Qu R, He Y, Tian X, et al. Spermatogonial stem cells from domestic animals: progress and prospects. Reproduction. 2014;147:R65–74. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Miki H, Ogura A, et al. Long-term proliferation in culture and germline transmission of mouse male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:612–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ntemou E, Kadam P, Van Saen D, Wistuba J, Mitchell R, et al. Complete spermatogenesis in intratesticular testis tissue xenotransplants from immature non-human primate. Hum Reprod. 2019;34:403–13. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pukazhenthi BS, Nagashima J, Travis AJ, Costa GM, Escobar EN, et al. Slow freezing, but not vitrification supports complete spermatogenesis in cryopreserved, neonatal sheep testicular xenografts. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liao HF, Chen WS, Chen YH, Kao TH, Tseng YT, et al. DNMT3L promotes quiescence in postnatal spermatogonial progenitor cells. Development. 2014;141:2402–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.105130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zheng L, Zhai Y, Li N, Ma F, Zhu H, et al. The modification of Tet1 in male germline stem cells and interact with PCNA, HDAC1 to promote their self-renewal and proliferation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37414. doi: 10.1038/srep37414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hu K, Zhang J, Liang M. LncRNA AK015322 promotes proliferation of spermatogonial stem cell C18-4 by acting as a decoy for microRNA-19b-3p. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2017;53:277–84. doi: 10.1007/s11626-016-0102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li X, Ao J, Wu J. Systematic identification and comparison of expressed profiles of lncRNAs and circRNAs with associated co-expression and ceRNA networks in mouse germline stem cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:26573. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.He Z, Jiang J, Kokkinaki M, Tang L, Zeng W, et al. MiRNA-20 and miRNA-106a regulate spermatogonial stem cell renewal at the post-transcriptional level via targeting STAT3 and Ccnd1. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2205–17. doi: 10.1002/stem.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang Y, Zuo Q, Bi Y, Zhang W, Jin J, et al. miR-31 Regulates spermatogonial stem cells meiosis via targeting Stra8. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:4844–53. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Huang YL, Huang GY, Lv J, Pan LN, Luo X, et al. miR-100 promotes the proliferation of spermatogonial stem cells via regulating Stat3. Mol Reprod Dev. 2017;84:693–701. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang F, Zhang Y, Lv X, Xu B, Zhang H, et al. Evolution of an X-linked miRNA family predominantly expressed in mammalian male germ cells. Mol Biol Evol. 2019;36:663–78. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dong J, Wang X, Cao C, Wen Y, Sakashita A, et al. UHRF1 suppresses retrotransposons and cooperates with PRMT5 and PIWI proteins in male germ cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12455-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sadri-Ardekani H, Mizrak SC, van Daalen SK, Korver CM, Roepers-Gajadien HL, et al. Propagation of human spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. JAMA. 2009;302:2127–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Guo Y, Liu L, Sun M, Hai Y, Li Z, et al. Expansion and long-term culture of human spermatogonial stem cells via the activation of SMAD3 and AKT pathways. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2015;240:1112–22. doi: 10.1177/1535370215590822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Langenstroth D, Kossack N, Westernströer B, Wistuba J, Behr R, et al. Separation of somatic and germ cells is required to establish primate spermatogonial cultures. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2018–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Morimoto H, Ogura A, et al. Serum- and feeder-free culture of mouse germline stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:97–105. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.086462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ren F, Fang Q, Xi H, Feng T, Wang L, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB and epidermal growth factor promote dairy goat spermatogonial stem cells proliferation via Ras/ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Theriogenology. 2020;155:205–12. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Binsila BK, Selvaraju S, Ghosh SK, Ramya L, Arangasamy A, et al. EGF, GDNF, and IGF-1 influence the proliferation and stemness of ovine spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:2615–30. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01912-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Goel S, Sugimoto M, Minami N, Yamada M, Kume S, et al. Identification, isolation, and in vitro culture of porcine gonocytes. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:127–37. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.056879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zheng Y, Feng T, Zhang P, Lei P, Li F, et al. Establishment of cell lines with porcine spermatogonial stem cell properties. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2020;11:33. doi: 10.1186/s40104-020-00439-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Komai Y, Tanaka T, Tokuyama Y, Yanai H, Ohe S, et al. Bmi1 expression in long-term germ stem cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6175. doi: 10.1038/srep06175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zohni K, Zhang X, Tan SL, Chan P, Nagano M. CD9 is expressed on human male germ cells that have a long-term repopulation potential after transplantation into mouse testes. Biol Reprod. 2012;87:27. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.098913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. CD9 is a surface marker on mouse and rat male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:70–5. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cai H, Wu JY, An XL, Zhao XX, Wang ZZ, et al. Enrichment and culture of spermatogonia from cryopreserved adult bovine testis tissue. Anim Reprod Sci. 2016;166:109–15. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kaul G, Kumar S, Kumari S. Enrichment of CD9+ spermatogonial stem cells from goat (Capra aegagrus hircus) testis using magnetic microbeads. Stem Cell Disc. 2012;2:92–9. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tokuda M, Kadokawa Y, Kurahashi H, Marunouchi T. CDH1 is a specific marker for undifferentiated spermatogonia in mouse testes. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:130–41. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Izadyar F, Wong J, Maki C, Pacchiarotti J, Ramos T, et al. Identification and characterization of repopulating spermatogonial stem cells from the adult human testis. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1296–306. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Borjigin U, Davey R, Hutton K, Herrid M. Expression of promyelocytic leukaemia zinc-finger in ovine testis and its application in evaluating the enrichment efficiency of differential plating. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2010;22:733–42. doi: 10.1071/RD09237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Goertz MJ, Wu Z, Gallardo TD, Hamra FK, Castrillon DH. Foxo1 is required in mouse spermatogonial stem cells for their maintenance and the initiation of spermatogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3456–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI57984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.von Kopylow K, Staege H, Schulze W, Will H, Kirchhoff C. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is highly expressed in rarely dividing human type A spermatogonia. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;138:759–72. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-0991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hermann BP, Sukhwani M, Lin CC, Sheng Y, Tomko J, et al. Characterization, cryopreservation, and ablation of spermatogonial stem cells in adult rhesus macaques. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2330–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Oatley JM, de Avila DM, Reeves JJ, McLean DJ. Testis tissue explant culture supports survival and proliferation of bovine spermatogonial stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:625–31. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.022483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee K, Lee W, Kim J, Yoon M, Kim N, et al. Characterization of GFRα-1-Positive and GFRα-1-negative spermatogonia in neonatal pig testis. Reprod Domest Anim. 2013;48:954–60. doi: 10.1111/rda.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Seandel M, James D, Shmelkov SV, Falciatori I, Kim J, et al. Generation of functional multipotent adult stem cells from GPR125+ germline progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:346–50. doi: 10.1038/nature06129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sachs C, Robinson BD, Andres Martin L, Webster T, Gilbert M, et al. Evaluation of candidate spermatogonial markers ID 4 and GPR 125 in testes of adult human cadaveric organ donors. Andrology. 2014;2:607–14. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Helsel AR, Yang QE, Oatley MJ, Lord T, Sablitzky F, et al. ID4 levels dictate the stem cell state in mouse spermatogonia. Development. 2017;144:624–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.146928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Takehashi M, Takashima S, Lee J, Morimoto H, et al. Homing of mouse spermatogonial stem cells to germline niche depends on β1-integrin. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shinohara T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. β1-and α6-integrin are surface markers on mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5504–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.De Barros F, Worst RA, Saurin GCP, Mendes C, Assumpção M, et al. α-6 integrin expression in bovine spermatogonial cells purified by discontinuous Percoll density gradient. Reprod Domest Anim. 2012;47:887–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2012.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Aeckerle N, Eildermann K, Drummer C, Ehmcke J, Schweyer S, et al. The pluripotency factor LIN28 in monkey and human testes: a marker for spermatogonial stem cells? Mol Hum Reprod. 2012;18:477–88. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gas025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zheng K, Wu X, Kaestner KH, Wang PJ. The pluripotency factor LIN28 marks undifferentiated spermatogonia in mouse. BMC Dev Biol. 2009;9:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Suzuki H, Sada A, Yoshida S, Saga Y. The heterogeneity of spermatogonia is revealed by their topology and expression of marker proteins including the germ cell-specific proteins Nanos2 and Nanos3. Dev Biol. 2009;336:222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hermann BP, Sukhwani M, Simorangkir DR, Chu T, Plant TM, et al. Molecular dissection of the male germ cell lineage identifies putative spermatogonial stem cells in rhesus macaques. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1704–16. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Bhartiya D, Kasiviswanathan S, Unni SK, Pethe P, Dhabalia JV, et al. Newer insights into premeiotic development of germ cells in adult human testis using Oct-4 as a stem cell marker. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:1093–106. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.956870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Pesce M, Wang X, Wolgemuth DJ, Schöler HR. Differential expression of the Oct-4 transcription factor during mouse germ cell differentiation. Mech Dev. 1998;71:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Qasemi-Panahi B, Movahedin M, Moghaddam G, Tajik P, Koruji M, et al. Isolation and proliferation of spermatogonial cells from Ghezel sheep. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2018;10:93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Aloisio GM, Nakada Y, Saatcioglu HD, Peña CG, Baker MD, et al. PAX7 expression defines germline stem cells in the adult testis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3929–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI75943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Costoya JA, Hobbs RM, Barna M, Cattoretti G, Manova K, et al. Essential role of Plzf in maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells. Nat Genet. 2004;36:653–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Reding SC, Stepnoski AL, Cloninger EW, Oatley JM. THY1 is a conserved marker of undifferentiated spermatogonia in the pre-pubertal bull testis. Reproduction. 2010;139:893–903. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Naughton CK, Jain S, Strickland AM, Gupta A, Milbrandt J. Glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor-mediated RET signaling regulates spermatogonial stem cell fate. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:314–21. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.047365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Eildermann K, Aeckerle N, Debowski K, Godmann M, Christiansen H, et al. Developmental expression of the pluripotency factor sal-like protein 4 in the monkey, human and mouse testis: restriction to premeiotic germ cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;196:206–20. doi: 10.1159/000335031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Hobbs RM, Fagoonee S, Papa A, Webster K, Altruda F, et al. Functional antagonism between Sall4 and Plzf defines germline progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:284–98. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ramaswamy S, Razack BS, Roslund RM, Suzuki H, Marshall GR, et al. Spermatogonial SOHLH1 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling associates with initiation of spermatogenesis in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:350–7. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ballow D, Meistrich M, Matzuk M, Rajkovic A. Sohlh1 is essential for spermatogonial differentiation. Dev Biol. 2006;294:161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Abbasi H, Tahmoorespur M, Hosseini SM, Nasiri Z, Bahadorani M, et al. THY1 as a reliable marker for enrichment of undifferentiated spermatogonia in the goat. Theriogenology. 2013;80:923–32. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kwon J, Kikuchi T, Setsuie R, Ishii Y, Kyuwa S, et al. Characterization of the testis in congenitally ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase-1 (Uch-L1) defective (gad) mice. Exp Anim. 2003;52:1–9. doi: 10.1538/expanim.52.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Herrid M, Davey RJ, Hill JR. Characterization of germ cells from pre-pubertal bull calves in preparation for germ cell transplantation. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;330:321–9. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0445-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Heidari B, Rahmati-Ahmadabadi M, Akhondi MM, Zarnani AH, Jeddi-Tehrani M, et al. Isolation, identification, and culture of goat spermatogonial stem cells using c-kit and PGP9.5 markers. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29:1029–38. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9828-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Luo J, Megee S, Rathi R, Dobrinski I. Protein gene product 9.5 is a spermatogonia-specific marker in the pig testis: application to enrichment and culture of porcine spermatogonia. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73:1531–40. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.van Bragt MP, Roepers-Gajadien HL, Korver CM, Bogerd J, Okuda A, et al. Expression of the pluripotency marker UTF1 is restricted to a subpopulation of early A spermatogonia in rat testis. Reproduction. 2008;136:33–40. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lee WY, Lee KH, Heo YT, Kim NH, Kim JH, et al. Transcriptional coactivator undifferentiated embryonic cell transcription factor 1 expressed in spermatogonial stem cells: a putative marker of boar spermatogonia. Anim Reprod Sci. 2014;150:115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Koruji M, Movahedin M, Mowla SJ, Gourabi H, Pour-Beiranvand S, et al. Autologous transplantation of adult mice spermatogonial stem cells into gamma irradiated testes. Cell J. 2012;14:82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Ma W, Wang J, Gao W, Jia H. The safe recipient of SSC transplantation prepared by heat shock with busulfan treatment in mice. Cell Transplant. 2018;27:1451–8. doi: 10.1177/0963689718794126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Izadyar F, den Ouden K, Creemers LB, Posthuma G, Parvinen M, et al. Proliferation and differentiation of bovine type A spermatogonia during long-term culture. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:272–81. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.004986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Shirazi MS, Heidari B, Naderi MM, Behzadi B, Sarvari A, et al. Transplantation of goat spermatogonial stem cells into the mouse rete testis. Int J Anim Biol. 2015;1:61–8. [Google Scholar]

- 161.Zeng W, Tang L, Bondareva A, Honaramooz A, Tanco V, et al. Viral transduction of male germline stem cells results in transgene transmission after germ cell transplantation in pigs. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:27, 1–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.104422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Dobrinski I, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Germ cell transplantation from large domestic animals into mouse testes. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;57:270–9. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(200011)57:3<270::AID-MRD9>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]