ABSTRACT

Human milk enriches members of the genus Bifidobacterium in the infant gut. One species, Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum, is found in the gastrointestinal tracts of adults and breastfed infants. In this study, B. pseudocatenulatum strains were isolated and characterized to identify genetic adaptations to the breastfed infant gut. During growth on pooled human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), we observed two distinct groups of B. pseudocatenulatum, isolates that readily consumed HMOs and those that did not, a difference driven by variable catabolism of fucosylated HMOs. A conserved gene cluster for fucosylated HMO utilization was identified in several sequenced B. pseudocatenulatum strains. One isolate, B. pseudocatenulatum MP80, which uniquely possessed GH95 and GH29 α-fucosidases, consumed the majority of fucosylated HMOs tested. Furthermore, B. pseudocatenulatum SC585, which possesses only a single GH95 α-fucosidase, lacked the ability to consume the complete repertoire of linkages within the fucosylated HMO pool. Analysis of the purified GH29 and GH95 fucosidase activities directly on HMOs revealed complementing enzyme specificities with the GH95 enzyme preferring 1-2 fucosyl linkages and the GH29 enzyme favoring 1-3 and 1-4 linkages. The HMO-binding specificities of the family 1 solute-binding protein component linked to the fucosylated HMO gene cluster in both SC585 and MP80 are similar, suggesting differential transport of fucosylated HMO is not a driving factor in each strain’s distinct HMO consumption pattern. Taken together, these data indicate the presence or absence of specific α-fucosidases directs the strain-specific fucosylated HMO utilization pattern among bifidobacteria and likely influences competitive behavior for HMO foraging in situ.

IMPORTANCE Often isolated from the human gut, microbes from the bacterial family Bifidobacteriaceae commonly possess genes enabling carbohydrate utilization. Isolates from breastfed infants often grow on and possess genes for the catabolism of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), glycans found in human breast milk. However, catabolism of structurally diverse HMOs differs between bifidobacterial strains. This study identifies key gene differences between Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum isolates that may impact whether a microbe successfully colonizes an infant gut. In this case, the presence of complementary α-fucosidases may provide an advantage to microbes seeking residence in the infant gut. Such knowledge furthers our understanding of how diet drives bacterial colonization of the infant gut.

KEYWORDS: fucosylated HMO, Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum, α-fucosidase, substrate-binding protein, strain specificity, Bifidobacterium, fucosidases, glycan metabolism, milk oligosaccharides

INTRODUCTION

In humans, colonization of the gut microbiome in early life is strongly influenced by various elements in human milk. Human milk is composed of lactose, fats, proteins, and numerous bioactive molecules. One key constituent known to influence the gut microbiota is human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs). These highly abundant (10 to 15 g liter−1) (1) and structurally diverse bioactive molecules consist of neutral (nonfucosylated and fucosylated) and acidic sialylated oligosaccharides (2). While energetically dense, HMOs are not digested by the infant but, rather, fermented by intestinal microbes, often infant-borne bifidobacteria (3). Only one species of Bifidobacterium, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis, has been shown to consume the full constellation of HMO structures (4–6), while isolates of other infant-borne species, including Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum (7), Bifidobacterium breve (8), Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense (9), and Bifidobacterium bifidum (10), have been shown to consume portions of the HMO pool. These differential consumption phenotypes suggest that HMOs delivered to infants enrich a network of primary bifidobacterial consumers who target different components of the HMO pool. In addition, some primary consumers partially degrade HMOs externally, releasing component sugars, which are consumed by recipient strains (11, 12). Similar HMO consumption networks could be predicted from other HMO-consuming taxa like Bacteriodes species (13), Akkermansia species (14), and Roseburia species (15), among other taxa that degrade HMOs externally. These HMO consumption networks, along with the conditioning of the environment from production of organic acids (16) and lowering of pH (17), generated by fermentation of HMOs, likely limit entry into the infant colonic ecosystem.

The genome of B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 contains transporters, substrate-binding proteins (SBP), and glycosyl hydrolases (GH) organized in a 43-kb cluster specialized for HMO utilization (18). While other Bifidobacterium species exhibit growth on HMOs, none grow as robustly as B. longum subsp. infantis. Although the closely related B. longum subsp. longum can broadly consume type I core HMOs, relatively few strains are capable of metabolizing fucosylated HMOs, and none are known to consume sialylated HMOs (7). These growth differences have a clear genetic basis in B. longum subsp. longum SC596, which encodes two β-galactosidases and two α-fucosidases but lacks a sialidase (7). B. breve strains generally consume type I and II core HMOs (6, 8, 19), whereas fucosylated and sialylated HMO consumption is restricted to a few specific strains (8). The enzymes lacto-N-biosidase (20), α-fucosidase GH29 (21), and α-fucosidase GH95 (22) are necessary for extracellular cleavage of HMOs prior to importation and catabolism in B. bifidum. While B. longum, B. breve, and B. bifidum are well studied, they are not the only Bifidobacterium species detected in breastfed infant feces.

Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum is prevalent in the feces of breastfed infants (8, 16, 23–27), as well as adults (28–30). The bacterial composition of the infant and adult gut microbiome is distinct (31, 32) and attributable in part to differences in dietary intake. These dietary differences may select for distinct metabolic abilities in infant- and adult-derived B. pseudocatenulatum strains. Of six B. pseudocatenulatum isolates from a cohort of Japanese breastfed infants, only three showed growth on pooled HMOs, preferentially consuming fucosylated HMOs, which corresponded to the presence of an α-fucosidase GH95 (16). On the other hand, an adult-derived B. pseudocatenulatum strain 1E was unable to consume type II core HMOs, even though in silico analysis revealed that its genome encoded β-galactosidases and a β-hexosaminidase (30). Further research is needed to understand strain-specific HMO utilization in B. pseudocatenulatum. In this study, we explored the genetic basis of fucosylated HMO consumption in infant-derived, adult-derived, and other available B. pseudocatenulatum strains.

RESULTS

Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum.

To evaluate a diverse pool of B. pseudocatenulatum strains for HMO growth phenotypes, isolates were obtained from many sources (Table 1). Most B. pseudocatenulatum strains were obtained from earlier studies (infant derived) (8, 33), culture collections (various sources), and colleagues (lamb derived) (34). An adult-derived B. pseudocatenulatum GST210 was isolated from a fecal sample donated by an individual participant in a bovine milk oligosaccharide supplementation tolerance trial (35). All B. pseudocatenulatum isolates (n = 62) were characterized with multilocus sequence typing. In total, 11 unique allelic profiles were observed (data not shown) and concatenated to construct a phylogenetic tree (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). While B. pseudocatenulatum DSM 20438 had an identical allelic profile to B. pseudocatenulatum MP86, both isolates were included in this study since they came from two very different sources. All 12 B. pseudocatenulatum strains are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum strains included in this study

| Strain IDa | Origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SC237 | Infant feces | 11 |

| SC564 | Infant feces | 11 |

| SC585 | Infant feces | 11 |

| SC665 | Infant feces | 11 |

| SC666 | Infant feces | 11 |

| MP80 | Infant feces | 26 |

| MP86 | Infant feces | 26 |

| JCM7040 | Human feces | |

| JCM11661 | Unlisted | |

| GST210 | Adult feces | This study |

| L15 | Lamb feces | 27 |

| DSM 20438 | Infant feces |

JCM, Japan Collection of Microorganisms; DSM, German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures.

Growth of B. pseudocatenulatum isolates on pooled HMOs and select purified fucosylated HMOs.

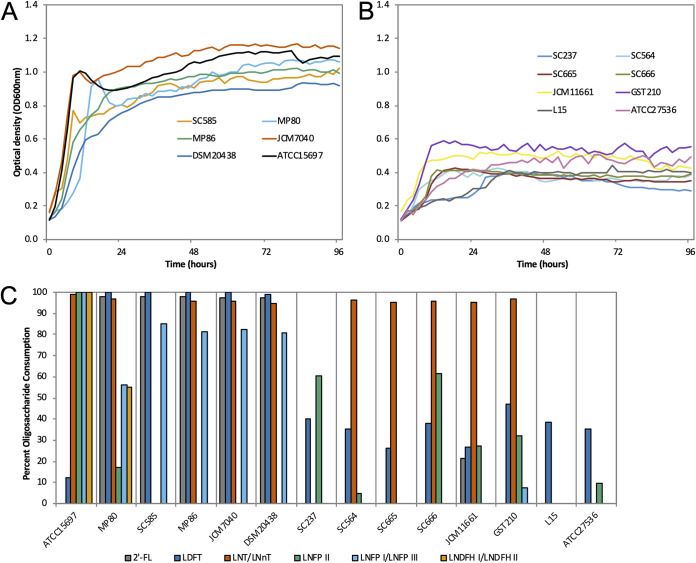

Isolates of B. pseudocatenulatum (n = 12) were examined for their ability to consume pooled HMOs. All B. pseudocatenulatum isolates grew well on lactose (positive control, data not shown), whereas growth on pooled HMOs varied (Fig. 1A and B). The B. pseudocatenulatum isolates SC585, MP80, MP86, DSM 20438 (infant derived), and JCM7040 (human derived) grew to a maximum optimum density (OD) (0.94 ≤ OD ≤ 1.17) similar to the positive-control B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 (OD, 1.13) (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the B. pseudocatenulatum isolates SC237, SC564, SC665, SC666 (infant derived), JCM11661 (origin unknown), GST210 (adult derived), and L15 (lamb derived) grew to a maximum OD (0.39 ≤ OD ≤ 0.59), similar to the negative-control Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis ATCC 27536 (OD, 0.51) (Fig. 1B). Since the purification of pooled HMOs does not remove 100% of the lactose, it is common to observe minimal growth.

FIG 1.

B. pseudocatenulatum growth and glycoprofiling on human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs). B. pseudocatenulatum isolates grown on 2% (wt/vol) pooled HMOs with strong (A) and weak (B) growth phenotypes. B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 and B. animalis subsp. lactis ATCC 27536 were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. Mean optical density at 600 nm of two independent biological replicates. (C) Glycoprofiling of the dominant HMOs from this HMO pool consumed by B. pseudocatenulatum isolates grown on 2% (wt/vol) HMOs. Percent consumption was calculated as the difference in HMO structure abundance at 96 h relative to 0 h. 2′-FL, 2′-fucosyllactose; LDFT, lactodifucotetraose; LNT, lacto-N-tetraose; LNnT, lacto-N-neotetraose; LNFP I, II, and III, lacto-N-fucopentaose type I, II, and III; LNDFH I and II, lacto-N-difucohexaose type I and II.

Mass spectrometry was used to profile select (i.e., dominant) HMO structures from this specific pool that were consumed by each B. pseudocatenulatum strain via analysis of the spent media (Fig. 1C and Table S1). Isomers lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) were depleted (>94%) by most B. pseudocatenulatum isolates, but consumption was undetectable in B. pseudocatenulatum SC585 (infant derived), SC237, and L15 (lamb associated).

Consumption of fucosylated HMOs by B. pseudocatenulatum isolates varied by structure. 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL) and lactodifucotetraose (LDFT) were depleted almost entirely by B. pseudocatenulatum SC585, MP80, MP86, JCM7040, and DSM 20438 (all >97%). All B. pseudocatenulatum isolates exhibited some consumption of LDFT (26 to 47%). Lacto-N-fucopentaose type I and III (LNFP I and LNFP III, respectively) were consumed by B. pseudocatenulatum that consumed 2′-FL, albeit to a lesser extent (66 to 85%). Uniquely, B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 consumed lacto-N-difucohexaose type I and II isomers (LNDFH I and LNDFH II, 55%). B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 demonstrated an ability to consume higher-molecular-weight HMOs, whereas B. pseudocatenulatum isolates preferred lower-molecular-weight fucosylated HMOs (Table S1).

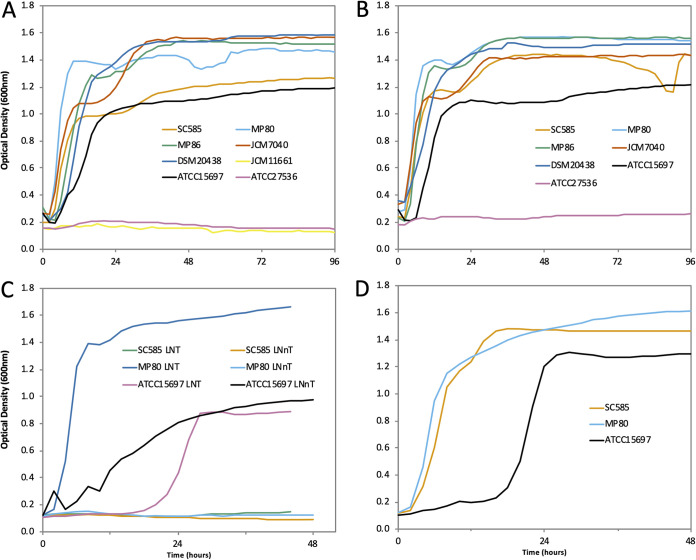

To explore subtle differences observed in growth on HMO pools (Fig. 1C), select B. pseudocatenulatum strains that grew well on HMO pools were examined for growth on purified HMO species. Strains SC585, MP80, MP86, JCM7040, and DSM 20438 grew on purified 2′-FL and 3′-fucosyllactose (3′-FL) (Fig. 2A and B). While B. pseudocatenulatum JCM11661 consumed 2′-FL from pooled HMOs (22%, Fig. 1C), it failed to grow robustly on purified 2′-FL as the sole carbon source (Fig. 2A). Notably, SC585 was able to grow on LNT but failed to grow on LNnT, while MP80 readily grew on both isomers (Fig. 2C). However, both MP80 and SC585 readily grew on LNFP1, which contains the LNnT type 2 core (Fig. 2D).

FIG 2.

Subset of B. pseudocatenulatum isolates grown on 2% (wt/vol) 2′-fucosyllactose (A), 3′-fucosyllactose (B), lacto-N-tetraose and lacto-N-neotetraose (C), and lacto-N-fucopentaose I (D). B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 and B. animalis subsp. lactis ATCC 27536 were included as positive and negative controls. Mean optical density at 600 nm of two independent biological replicates.

Growth of B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 on 2′-FL and lactose produced the end products acetate (44.71 mM ± 1.21 versus 44.51 mM ± 0.20; P = 0.185), lactate (19.06 mM ± 0.53 versus 22.79 ± 0.12; P = 0.027), and ethanol (0.92 mM ± 0.02, 0.35 mM ± 0.003; P < 0.01). B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 produced significantly larger amounts of formate (6.20 mM ± 0.23 versus 0.74 mM ± 0.002; P < 0.01), pyruvate (2.82 mM ± 0.11 versus 0.12 mM ± 0.002; P < 0.01), and 1,2-propanediol (2.82 mM ± 0.18 versus 0.00 mM ± 0.00; P < 0.01) following growth on 2′-FL than growth on lactose (Table 2). The metabolites observed provide functional validation of the MP80 fucose catabolism via the propanediol pathway observed in other fucosylated HMO (F-HMO)-consuming bifidobacterial strains (9).

TABLE 2.

Millimolar concentrations of metabolites detected in the cell-free supernatant of B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 grown on 1% 2′-FL versus 1% lactosea

| Carbohydrate | Concn (mM) of: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Lactate | Ethanol | Formate | Pyruvate | 1,2-Propanediol | Fucose | |

| 2′-FL | 44.71 ± 1.21 | 19.06 ± 0.53 | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 6.20 ± 0.23 | 2.82 ± 0.11 | 4.28 ± 0.18 | 0.65 ± 0.01 |

| Lactose | 47.51 ± 0.20 | 22.79 ± 0.12 | 0.35 ± 0.00 | 0.74 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | ND | ND |

| P value | 0.185 | 0.027 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | NA | NA |

Data are presented as mean ± SE. 2′-FL, 2′-fucosyllactose; ND, not detected; NA, not available.

Characterization of a fucosylated HMO utilization gene cluster.

To identify genes required for fucosylated HMO consumption, we sequenced the genomes of B. pseudocatenulatum SC585, MP80, JCM7040, JCM11661, L15, and GST210 (refer to Table S2 for a summary of the sequencing metrics). B. pseudocatenulatum L15 and GST210 were included as representatives that could not consume 2′-FL. These newly sequenced B. pseudocatenulatum strains have comparable genome sizes and characteristics to B. pseudocatenulatum DSM 20438.

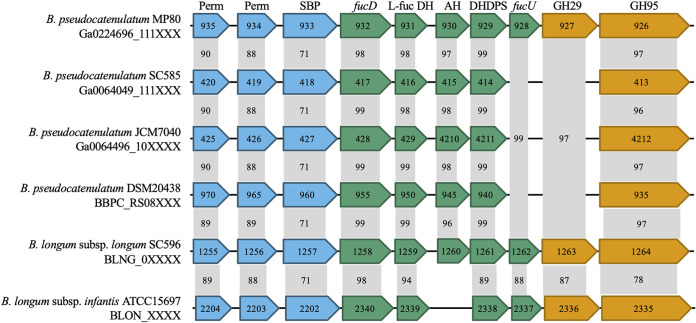

A cluster of genes, predicted to be associated with the consumption of F-HMOs, was readily observed in B. pseudocatenulatum SC585, MP80, JCM7040, and DSM 20438 (Fig. 3). Annotated genes in this cluster include two ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter permease components, a family 1 (oligosaccharide-binding) ABC transporter substrate-binding protein, an l-fuconate dehydratase, an l-fucose dehydrogenase, a metal-dependent hydrolase, a 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase, and an α-fucosidase GH95. B. pseudocatenulatum L15 or GST210 did not contain the putative F-HMO gene cluster, consistent with their inability to robustly consume F-HMOs (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, two additional genes, a fucose mutarotase and an α-fucosidase GH29, were observed in B. pseudocatenulatum MP80. These additional genes are homologous to the fucose mutarotase and α-fucosidase GH29 from B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697.

FIG 3.

Schematic representation of the fucosylated HMO utilization cluster in B. pseudocatenulatum strains MP80, SC585, JCM7040, and DSM 20438 (GenBank accession number AP012330) and homologous genes in B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 (GenBank accession number CP001095). Partial gene locus tags are reported inside the arrows, and gene annotations are at the top. Genes are grouped by primary function as follows: oligosaccharide transport, blue; carbohydrate feeder pathways, green; and glycosyl hydrolases, orange. Numbers in gray boxes represent percent identity of amino acid sequences compared to B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 (BLASTp from NCBI). Perm, ABC permease; SBP, substrate-binding protein; fucD, l-fuconate dehydratase; l-fuc DH, l-fucose dehydrogenase; AH, amido hydrolase; DHDPS, dihydropicolinate synthase; fucU, l-fucose mutarotase; GH29, α-fucosidase; GH95, α-fucosidase.

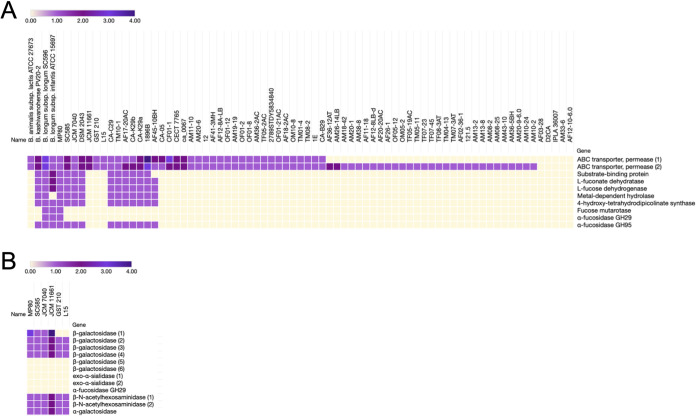

A survey of all publicly available B. pseudocatenulatum genomes in NCBI (June 2020) revealed a subset of strains possessing homologs of the fucosidase operon found in B. pseudocatenulatum SC585, MP80, and JCM7040 (Fig. 4). Of this subset, strains CA-C29, CA-K29a, and CA-K29b are infant derived, while the B. pseudocatenulatum isolates TM10-1, AF17-20AC, and AF45-10BH were isolated from human feces of an unreported age. Unique among B. pseudocatenulatum isolates, B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 possessed two α-fucosidases (GH29 and GH95) resembling the genomes of B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 and B. longum subsp. longum SC596 (7, 36). This additional fucosidase presence in MP80 and absence in the other F-HMO-consuming B. pseudocatenulatum strains (SC585, JCM7040, and DSM 20438) likely contributes to the differential F-HMO catabolism capacity described above. Aside from some shared ABC transporter permeases, most B. pseudocatenulatum strains lack homologs of the fucosidase operon entirely (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

(A) Relative abundance of fucosidase operon homologs in publicly available B. pseudocatenulatum genomes. Color gradient represents the number of homologs of each gene predicted within the genomes depicted. Hierarchical clustering (Spearman rank correlation, average linkage) was performed based on the presence or absence of homologs throughout the fucosidase operon. B. animalis subsp. lactis ATCC 27673 (F-HMO+), B. kashiwanohense PV20-2, B. longum subsp. longum SC596 (F-HMO positive [F-HMO+]), and B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 (F-HMO+) included for reference. B. pseudocatenulatum strain genome sequence accessions used are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material. (B) Additional HMO-related glycosyl hydrolases and transporters from the six B. pseudocatenulatum strains glycoprofiled in this work (see Fig. 1 and 2). Homologs were predicted with PyParanoid (v0.4.1).

While the presence or absence of this main F-HMO gene cluster clearly differentiated the more robust F-HMO consumer strains (MP80, SC585, and JCM7040) from the “nonconsumers” (L15, JCM11661, and GST210), it did not explain other subtle differences in HMO consumption patterns between some strains. Notably, glycoprofiling revealed that strain SC585 did not consume LNT/LNnT (Fig. 1C). While SC585 lacked the ability to grow on LNnT and LNT, it was able to grow well on LNFP1, which contains LNnT as a core (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the shared presence of HMO-related GHs in sequenced strains MP80, JCM7040, and SC585 (Fig. 4B) does not predict the differential consumption of LNnT/LNT in these strains, demonstrating the requirement for individual strain glycoprofiling of HMO consumption preferences (from HMO pools) as well as growth on individual HMOs to truly decipher strain-level HMO-foraging behavior. At present, the mechanism underlying the lack of growth of SC585 on LNnT remains unresolved.

Transcriptomics of MP80 grown on lactose, 2′-FL, and LNFP1 revealed clear induction of the main F-HMO cluster (the cluster shown in Fig. 3) with each gene of the cluster induced from 16- to 48-fold upon growth on the two F-HMOs (Table 3). In addition, an LNB/GNB gene cluster common to many bifidobacteria, including those that do not consume F-HMOs (37) as strongly, was upregulated during growth on LNFP1 but not on 2′-FL, likely due to the fact that LNFP1 contains N-acetylglucosamine. This complements a previous observation of the lack of induction of the LNB/GNB cluster during growth on 2′-FL in a B. longum strain that harbors a similar F-HMO cluster (7). In a separate experiment using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR), strain SC585, which possessed a similar gene cluster for fucose consumption to MP80 but lacks the GH29 fucosidase, showed a similar induction of the GH95 fucosidase (Ga0064049_111413) and SBP (Ga0064049_111418) during growth on 2′-FL (Fig. S2), suggesting a common regulation across strains harboring this F-HMO gene cluster.

TABLE 3.

Expression fold changes of fucosylated HMO utilization cluster, LNB/GNB cluster, and other HMO-utilizing genes in B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 strain during growth in 2′-FL and LNFP1a

| Gene ID | Annotated function | Fold change during growth on substrates |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 2′-FL | LNFPI | ||

| FHMO utilization cluster | |||

| 2765237614 | 1,2-α-l-fucosidases (GH95) | 21.71 | 16.28 |

| 2765237615 | α-1,3/1,4-l-fucosidase (GH29) | 22.24 | 16.07 |

| 2765237616 | l-fucose mutarotase | 20.35 | 15.08 |

| 2765237617 | 4-Hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase | 26.74 | 21.77 |

| 2765237618 | Amido hydrolase | 42.09 | 48.53 |

| 2765237619 | l-fucose dehydrogenase | 40.28 | 51.69 |

| 2765237620 | l-fuconate dehydratase | 40.34 | 45.18 |

| 2765237621 | Solute-binding protein | 30.82 | 38.22 |

| 2765237622 | ABC permease | 28.41 | 38.05 |

| 2765237623 | ABC permease | 29.60 | 41.63 |

| 2765237623 | Transcriptional regulator | 2.58 | 2.61 |

| LNB/GNB cluster | |||

| 2765237505 | N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase | 1.03 | 66.36 |

| 2765237506 | Glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase | 0.60 | 48.50 |

| 2765237507 | β-N-acetylhexosaminidase | 0.60 | 21.57 |

| 2765237508 | Predicted NBD/HSP70 family sugar kinase | 0.51 | 31.28 |

| 2765237509 | ABC permease | 0.60 | 12.39 |

| 2765237510 | ABC permease | 0.48 | 7.91 |

| 2765237511 | Type 1 HMO solute-binding protein | 0.61 | 2.17 |

| Other important HMO-utilizing genes | |||

| 2765236220 | β-Galactosidase | 0.97 | 12.04 |

| 2765237192 | β-Galactosidase | 1.92 | 6.34 |

| 2765237343 | β-Galactosidase | 2.02 | 1.11 |

| 2765237514 | β-Galactosidase | 0.67 | 0.38 |

| 2765237579 | β-Galactosidase | 1.36 | 1.75 |

| 2765237612 | β-Galactosidase | 1.92 | 2.28 |

| 2765236421 | β-N-acetylhexosaminidase | 1.97 | 0.84 |

Level of expression is shown as fold change compared to the lactose control. Fold change values in bold have significant FDR P values (P ≤ 0.05).

B. pseudocatenulatum MP80’s α-fucosidase substrate digestion specificity.

In this work, most B. pseudocatenulatum strains that grow on F-HMOs only contained a single GH95 class of α-fucosidases. However, as shown in Fig. 3 and 4, MP80 contained both GH95 and GH29 type α-fucosidases, similar to those previously characterized in B. longum subsp. infantis (36) and B. longum subsp. longum SC596 (7). To understand the specificity of the MP80 α-fucosidases (GH29, Ga0224696_111927, and GH95, Ga0224696_111926), both were cloned, the enzymes purified, and their activity assessed against an HMO pool as described previously (7). While both α-fucosidases (GH29 and GH95) digested 2′-FL, the GH95 α-fucosidase showed higher activity (100%) than the GH29 α-fucosidase (42.8%) (Table 4). Overall, the GH95 α-fucosidase was more active than the GH29 α-fucosidase on 2-linked terminal fucose moieties (Table 4). Conversely, the GH29 α-fucosidase was more active than the GH95 α-fucosidase on 3- and 4-linked terminal fucose moieties (Table 4). In general, the addition of the GH29 enzyme (Ga0224696_111927) promoted cleavage of a range of HMO moieties poorly cleaved by the GH95 enzyme (Ga0224696_111926) (bolded structures in Table 4), suggesting the addition of the second α-fucosidase expanded the pool of fucosylated HMOs catabolized by MP80 by comparison to strains like SC585, which only contain a single GH95 type α-fucosidase.

TABLE 4.

Percent digestion of fucosylated HMOs by α-fucosidases (GH29 and GH95) from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80

| MW | Common name | % Digestion of: |

Fucose linkage(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GH29 | GH95 | |||

| 490.19 | 2′-fucosyllactose | 42.8 | 100 | α(1-2) |

| 855.33 | Lacto-N-fucopentaose II | 100 | 18.9 | α(1-4) |

| Lacto-N-fucopentaose I/III | 42.3 | 96.5 | α(1-2), α(1-3) | |

| 1220.46 | Monofucosyl-paralacto-N-hexaose IV | 90.9 | 30.3 | α(1-3) |

| 4120aa | 100 | −86.5 | α(1-4) | |

| Monofucosyllacto-N-hexaose III | 100 | 6.87 | α(1-3) | |

| Monofucosyllacto-N-hexaose I | 25.4 | 100 | α(1-2) | |

| Fucosyl-paralacto-N-hexaose III | 100 | 44.4 | α(1-3) | |

| Fucosyl-paralacto-N-hexaose I | 4.44 | 100 | α(1-2) | |

| 1366.51 | Difucosyl-paralacto-N-hexose II | 100 | 49.4 | α(1-3), α(1-4) |

| Difucosyllacto-N-hexose B | 100 | 8.80 | α(1-3), α(1-4) | |

| Difucosyllacto-N-hexose A | 97.5 | 100 | α(1-2), α(1-3) | |

| Difucosyllacto-N-hexose C | 54.6 | 44.9 | α(1-2), α(1, 4) | |

| 1512.57 | Trifucosyllacto-N-hexose | 100 | 92.5 | α(1-2), α(1-3), α(1-4) |

| 4320a | 100 | 100 | α(1, 2), α(1-3), α(1-4) | |

| 1585.58 | 5130a | 71.9 | 66.0 | α(1-3) |

| 5130b | 100 | −22.6 | α(1-4) | |

| Fucosyllacto-N-octaose | 44.7 | 12.1 | α(1-3) | |

| 5130c | 38.3 | 100 | α(1-2) | |

| 1731.64 | Difucosyllacto-N-neooctaose II | 64.8 | 100 | α(1-3) |

| 5230a | 100 | 100 | α(1-2), α(1-3) | |

| Difucosyllacto-N-neooctaose I/Difucosyllacto-N-octaose II | 83.5 | 89.1 | α(1-3), α(1-4) | |

| 5230b | 9.04 | 100 | α(1-2), α(1-3) | |

HMOs with numerical values refer to the number of hexose (first digit), fucose (second digit), GlcNac (third digit), and N-acetylneuraminic acid (fourth digit). MW, molecular weight; Gal, galactose; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine. Boldface indicates those oligosaccharides preferentially cleaved by GH29.

B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585 fucosidase operon SBP’s substrate-binding specificity.

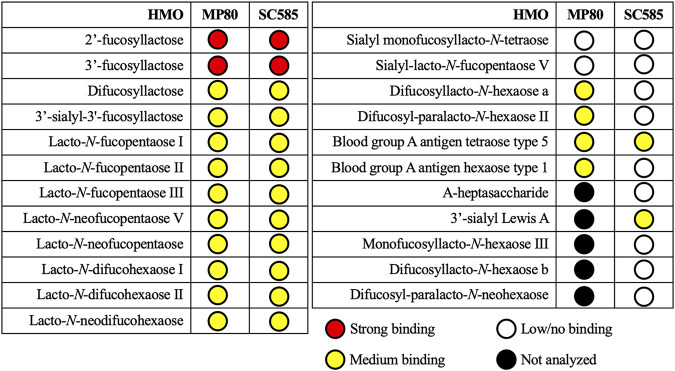

As shown above, strains MP80 and SC585 were able to consume fucosylated HMOs; however, differences were noted, particularly consumption of higher-molecular-weight HMOs by MP80. Given that we did not witness differences in SBP and GH95 expression between MP80 and SC585, we postulated that ATP transporter specificity differences between the strains might also drive the HMO consumption differences in addition to the added GH29 fucosidase in MP80. Notably, the SBPs from each strain (Ga00224696_111993 versus Ga0064049_111418) were only 71% identical by comparison to the higher identity among the remaining genes in this operon between the two strains (Fig. 3), which is clearly different than the near-identical homology among the remaining genes in the cluster. The SBPs from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585 were cloned and purified, and substrate-binding affinity to a variety of HMO structures was determined using catch-and-release electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (CaR-ESI-MS) (38, 39). 2′-FL and 3′-FL had the strongest binding affinity to SBPs from both B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585 (Fig. 5). Several fucosylated HMOs, including 2-, 3-, and 4-linked terminal fucose moieties, showed a moderate binding affinity to SBPs from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585. Specifically, B. pseudocatenulatum SC585’s SBP moderately bound fucosylated HMOs with smaller (≤4 monomers) and unbranched backbone structures (3′-sialyl Lewis A and blood group A antigen tetraose type 5). Of note, B. pseudocatenulatum MP80’s SBP uniquely bound to longer (>4 monomers) and branched backbone structures (difucosyllacto-N-hexaose A and difucosyl-para-lacto-N-hexaose II). Sialylation did not prevent binding of either strain’s SBP, and binding affinity did not require fucosylation. A complete list of HMO structures evaluated is presented in Tables S4 and S5.

FIG 5.

Binding specificity of B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585’s substrate-binding protein to fucosylated HMO. Affinities of the HMOs were ranked according to the abundances of ligands released from the protein complexes (for details, refer to Materials and Methods).

DISCUSSION

HMOs serve as a nutritional source for the proliferation of Bifidobacterium species in breastfed infants (40, 41). The relative abundance and composition of Bifidobacterium species are correlated with maternal secretor status (33), and fucosylated HMO-consuming Bifidobacterium species promote beneficial intestinal metabolite profiles and microbiome compositions (16). B. pseudocatenulatum is a frequently detected member in the mammalian gut microbiota (30), including in breastfed infants (8, 16, 23–27) and adults (28–30). Therefore, it is important to examine the genomic diversity of B. pseudocatenulatum strains to understand its presence in several distinct ecological contexts. Unlike other species common to breastfed neonates such as B. longum subsp. infantis, B. longum subsp. longum, B. breve, or B. bifidum, B. pseudocatenulatum has been poorly studied despite its frequent presence in breastfed infant feces. In this study, a fucosylated HMO utilization gene cluster was identified and characterized in a subset of infant-derived B. pseudocatenulatum strains.

Presence of a fucosylated HMO gene cluster drives strain-dependent utilization.

Growth studies revealed a subset of HMO-consuming B. pseudocatenulatum isolates originating from breastfed infants. Unlike these strains, other tested B. pseudocatenulatum isolates, including infant-, adult-, and lamb-derived specimens, poorly consumed HMOs as a sole carbon source. It was not surprising to observe poor consumption of HMOs in the adult- and lamb-derived B. pseudocatenulatum since HMOs are not a part of an adult or lamb’s diet. However, the differential HMO consumption in infant-derived B. pseudocatenulatum isolates may be due to the presence or absence of HMO catabolism genes.

Bifidobacterium species possess highly specialized HMO utilization gene clusters, which promote assimilation and catabolism of neutral nonfucosylated/nonsialylated, neutral fucosylated, and acidic sialylated HMOs (42). Not all isolated Bifidobacterium strains from breastfed infants are capable of consuming all HMO isomers due to missing, incomplete, or dysfunctional HMO utilization gene clusters (8, 16, 27, 43–45). Whole-genome sequencing of B. pseudocatenulatum SC585, MP80, and JCM7040 (all infant derived) revealed an intact fucosylated HMO utilization gene cluster containing oligosaccharide transporters, a carbohydrate feeder pathway, and glycosyl hydrolase genes (Fig. 3). This gene cluster’s structure and composition are homologous to the fucosylated HMO utilization gene clusters in B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 (18), B. longum subsp. longum SC596 (7), Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense PV20-2 (9), and other B. pseudocatenulatum isolates (16) (Fig. 4).

A broad analysis of publicly available B. pseudocatenulatum genomes illustrates a subset of B. pseudocatenulatum strains uniquely capable of consuming fucosylated HMOs (Fig. 4). Additionally, B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 is unique among B. pseudocatenulatum isolates given that it possesses two α-fucosidases (GH29 and GH95). This gene cluster was missing in the fucosylated HMO-nonconsuming B. pseudocatenulatum strains JCM11661, L15, and GST210 included in this study. Previous studies and our analysis (Fig. 4) demonstrate that the presence or absence of genes within this gene cluster separates B. pseudocatenulatum strains into either consumers or nonconsumers of fucosylated HMOs (16, 27). Matsuki and colleagues (16) concluded that the fucosylated HMO utilization pathway, present in other isolated Bifidobacterium species as well as a subset of B. pseudocatenulatum, was fundamental in their cohort of Japanese infants (n = 12). Infants consuming breastmilk from secretor mothers and harboring fucosylated HMO-consuming Bifidobacterium species (B1 cluster) were characterized by lower fecal pH and higher concentrations of fecal acetate. They concluded that fucosylated HMO-consuming Bifidobacterium species, including B. pseudocatenulatum, produce metabolites which bestow health benefits to infants.

B. pseudocatenulatum MP80, a robust fucosylated HMO consumer, possesses complementary α-fucosidases (GH29 and GH95).

Previous characterization of the fucosylated HMO utilization gene cluster in B. pseudocatenulatum strains found that a single α-fucosidase belonging to the GH95 family was associated with consumption of 2′-FL (16, 27) and other fucosylated HMOs (16). However, the genome of B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 contains an additional α-fucosidase (GH29), consistent with the gene clusters in B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 (18) and several other Bifidobacterium species (7–9, 16, 27) but not seen previously in B. pseudocatenulatum (16, 27). Additionally, both α-fucosidases (GH29 and GH95) were required for robust growth on 2-, 3-, and 4-linked fucosylated HMOs in B. breve SC95, SC154, and SC568 (8). The α-fucosidase GH29 has been shown to preferentially cleave 3- and 4-linked terminal fucose moieties (7, 21, 36), complementing the α-fucosidase GH95’s preference for 2-linked fucosylated HMOs (22, 46). Enzymatic substrate digestion specificity confirmed that B. pseudocatenulatum MP80’s α-fucosidase GH29 preferentially cleaved 3- and 4-linked terminal fucose moieties (Table 4). However, growth on 3- and 4-linked fucosylated HMOs did not require an α-fucosidase GH29 because B. pseudocatenulatum strains SC585, JCM7040, and DSM 20438 (lacking the α-fucosidase GH29) grew equally well on 2′-FL and 3′-FL. These data suggest that the α-fucosidase GH95 has some cross-reactivity on 3- and 4-linked fucosylated HMOs in B. pseudocatenulatum strains (Table 4). The catalytic specificity of α-fucosidase GH95s differs among Bifidobacterium species. Katayama and colleagues (22) did not observe cleavage of 3- or 4-linked fucosylated HMOs with B. bifidum JCM1254’s extracellular GH95 α-fucosidase. However, B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 moderately cleaved 3-linked fucosylated HMOs (46) and several B. breve strains consumed 3′-FL with a single α-fucosidase GH95 and no α-fucosidase GH29 (8). The amino acid sequence of the GH95 α-fucosidase in B. pseudocatenulatum MP80, B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 (78%), and B. breve JCM7019 (97%) are homologous while not being homologous to B. bifidum JCM 1254 (32%). While the presence of the α-fucosidase GH95 is sufficient for growth and cleavage of 3- and 4-linked fucosylated HMOs in vitro, substrate competition in vivo may still show a growth advantage to Bifidobacterium possessing the complementary α-fucosidase GH29.

Expanded fucosylated HMO consumption in B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 cannot be attributed to a more divergent substrate-binding protein.

The B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 genome encodes a plethora of family 1 SBPs to facilitate transport of HMOs via ABC permeases (18, 47). The B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 SBP (Blon_2202) and ABC permeases (Blon_2203-2204) are homologous (71 to 90% identical amino acid sequences) to the B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 SBP (Ga0224696_111933) and ABC permeases (Ga0224696_111934-111935). The B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 SBP (Blon_2202) has been shown to bind fucosylated HMOs (47, 48). Given its proximity to fucosylated HMO catabolism genes and homology to B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697’s SBP (Blon_2202), it is hypothesized that the SBP from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 (Ga0224696_111933) also binds fucosylated HMOs. Catch-and-release electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry showed moderate to strong binding of B. pseudocatenulatum MP80’s SBP (Ga0224696_111933) to 2-, 3-, and 4-linked fucosylated HMOs (Fig. 5). Recently, the crystal structure and ligand-binding site of B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697’s SBP (Blon_2202) was resolved for binding both 2′-FL and 3′-FL with a rotation of 50° to accommodate the different fucose moiety linkages (48). Therefore, the strong binding affinity for both 2′-FL and 3′-FL observed with B. pseudocatenulatum MP80’s SBP (Ga0224696_111933) was not unexpected. Additionally, B. pseudocatenulatum MP80’s SBP (Ga0224696_111933) moderately bound to several larger (DP >3) 2-, 3-, and 4-linked fucosylated HMOs. Sakanaka and colleagues (48) suggest that the binding pocket features of B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697’s SBP (Blon_2202) would likely accommodate larger fucosylated HMOs (DP >3) at lower affinities (48). Along with the presence of the α-fucosidase GH29, the divergent SBP (Ga0224696_111933) in B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 may allow access to a broader range of fucosylated HMO catabolism.

The infant-derived B. pseudocatenulatum SC585 strain, possessing one α-fucosidase (GH95), consumed less diverse fucosylated HMO structures (Fig. 1C) than B. pseudocatenulatum MP80. The homologous SBP (Ga0064049_111418) from B. pseudocatenulatum SC585 differed in amino acid sequence (71% similar), perhaps suggesting a slightly lower binding specificity for fucosylated HMOs. However, catch-and-release electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry assay did not show a significant difference in the binding specificity between the SBPs from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585. This result was not surprising given the greater homology (91% amino acid sequence) between the SBPs from B. pseudocatenulatum SC585 (Ga0064049_111418) and B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 (Blon_2202) and suggests that B. pseudocatenulatum MP80’s complementary α-fucosidases (GH29 and GH95) promote expanded fucosylated HMO consumption capability compared to other infant-derived B. pseudocatenulatum strains.

Conclusions. B. pseudocatenulatum is a widely dispersed species isolated from a number of diverse environments. This study, among others, demonstrates a genetic basis for specialized fucosylated HMO consumption in a subset of B. pseudocatenulatum strains isolated from breastfed infants (16, 27). In particular, the fucosylated HMO utilization gene cluster from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 indicates that the presence of complementary α-fucosidases (GH29 and GH95) may provide an advantage to residence in the infant gut.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and identification of Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum strains.

To isolate adult-derived B. pseudocatenulatum, 100 mg feces were vortexed in 900 μl sterile 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, serially diluted 10-fold in PBS, and plated (50 μl) onto modified Bifidobacterium selective iodoacetate mupirocin (BSIM) (33). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h anaerobically (5% CO2, 5% H2, and 90% N2; Coy Laboratory Products). Colonies were streaked for three successive passages onto deMan, Rogosa, and Sharpe supplemented with 500 mg liter−1 l-cysteine-HCl (MRSC) agar and subcultured into MRSC broth and stored at −80°C in 25% (vol/vol) glycerol. Additional strains of B. pseudocatenulatum (Table 1) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), the Japanese Collection of Microorganisms (JCM), German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSM), and previous isolation studies (8, 33, 34). Identities of B. pseudocatenulatum strains were confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight biotyper mass spectrometry as previously described (33).

Multilocus sequence typing of B. pseudocatenulatum isolates.

The intragenic regions of seven housekeeping genes (clpC, fusA, gyrB, ileS, purF, rplB, and rpoB) were selected based on previous work (49). Primers (Table 2) were optimized using the publicly available B. pseudocatenulatum DSM 20438 genome (GenBank accession number AP012330). Genomic DNA was extracted with the MasterPure Gram-positive DNA purification kit (Epicentre) and amplified on a PTC-200 Peltier thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). A 50-μl reaction mixture with 1 μl extracted DNA, 1 μl of each primer (10 μM), 1 μl dNTPs, 5 μl 10× PCR buffer, 5 μl MgCl2, and 0.25 μl (1.25 U) AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) was used. Cycling parameters were 4 min at 95°C, 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 63 to 67°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 7 min at 72°C. Amplification was confirmed by gel electrophoresis, and the PCR products were purified using the QiaQuick 96 PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Sequencing was performed on an ABI 3730 capillary electrophoresis genetic analyzer using BigDye Terminator chemistries at the University of California Davis DNA Sequencing Facility. The sequences were analyzed and aligned with ClustalW using BioEdit (version 7.0). Phylogenetic analysis of concatenated sequence loci was performed (version 6.0), and a minimum evolution tree was calculated (version 7.0) using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis software.

In vitro consumption of human milk oligosaccharides.

B. pseudocatenulatum strains (Table 1) were tested for growth in the presence of pooled HMOs, purified from breast milk as described previously (50), and lactose (positive control). B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 and B. animalis subsp. lactis ATCC 27536 were used as positive and negative HMO growth controls, respectively. All growths were conducted anaerobically at 37°C. Bifidobacterium species were cultured onto MRSC agar, incubated for 48 h, and subcultured into 500 μl MRSC broth. After 24 h of growth, 2% (vol/vol) was subcultured into 500 μl MRSC broth and incubated for 18 h. A 96-well plate containing 200 μl of modified MRS medium (mMRS) (33) supplemented with 2% (wt/vol) of pooled HMOs or lactose per well was inoculated with 4 μl of stationary-phase Bifidobacterium species cells. Additional inoculated wells without added carbohydrates were included as controls. All wells were covered with 50 μl of sterile mineral oil to avoid evaporation and incubated for 96 h. Optical density measurements at 600 nm (OD600) using a PowerWave 340 plate reader (BioTek) were taken every 30 min, preceded by 30 s of shaking at variable speed. After growth, cell-free supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 16,000 rcf for 1 min and stored at −80°C until identification of remaining HMOs (described below). Technical triplicates of biological duplicates were performed for each bacteria and sugar combination.

A subset of the Bifidobacterium isolates (those able to consume 2′-FL, as well as one that could not) were tested for growth on purified 2′-FL (Glycom) and 3′-FL (Glycom) (51) using the same methods as above.

B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 metabolite production following growth on 2′-FL.

B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 was subcultured three times on MRSC broth and incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 12 h. A 5% (500 μl [vol/vol]) inoculum was added to 10 ml of mMRS supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) lactose or 2′-FL. Optical density measurements were monitored in a PowerWave 340 plate reader until late log phase (OD600, ∼0.8). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 3,220 rcf for 3 min and washed in 10 ml 1× PBS (anaerobically conditioned) and resuspended in 15 ml mMRS supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) lactose or 2′-FL. After 10 min of anaerobic growth, cultures were centrifuged at 3,220 rcf for 3 min at 4°C. The cellular population (CFU ml−1) was calculated to determine consistency between triplicates. Cell-free supernatants were filtered through a 3-kDa-molecular-weight filter and stored at −80°C until analysis. Thawed filtrate was prepared with the addition of internal standard DSS-d6 [2,2,3,3,4,4-d6-3-(trimethylsilyl)-1-propane sulfonic acid] at a 1:10 ratio and adjusted to pH 6.8 ± 0.1 using NaOH and HCl. A 180-μl aliquot was transferred to a 3-mm Bruker nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) tube and stored at 4°C until spectral acquisition. Spectra were acquired by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy as previously described (52). Fourier-transformed spectra were processed in Chenomx NMR Suite (version 8.4) followed by manual annotation of each metabolite.

B. pseudocatenulatum genome sequencing and comparative genomics.

To whole-genome sequence six isolates (SC585, MP80, JCM7040, JCM11661, L15, and GST210), 100 to 1,000 ng of extracted and purified genomic DNA (described previously) was sent to the Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Laboratory at University of California Berkeley. DNA was sheared using Adaptive Focused Acoustics (Covaris) followed by library preparation using the IntegenX Apollo 324 platform with 13 rounds of amplification using WaferGen library prep kits. Single-read sequencing (50 bp) was performed using the high-throughput mode on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform. Sequencing files were concatenated using Terminal, trimmed with a maximum of 2 ambiguous base pairs, and deleted if their quality scores were below 0.5. Remaining sequences were de novo assembled using CLC Genomics Workbench. Subsequently, B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 was long-read sequenced with the single molecule real-time platform to aid in de novo assembly of its entire circular genome. B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 was streaked onto MRSC agar incubated at 37°C anaerobically; three colonies were subcultured into 2 ml of MRSC both and incubated at 37°C anaerobically overnight. Total genomic DNA (3 × 2 ml) was extracted with the DNeasy blood and tissue kit, including the pretreatment for Gram-positive bacteria (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slight modifications were made, including 20 μl of 50 mg ml−1 lysozyme from chicken egg white and 4 U of mutanolysin, and were included in the enzymatic lysis buffer, followed by addition of proteinase K and RNase A (kit provided) and incubation for 2 min at room temperature prior to combination with the AL buffer. Total genomic DNA was eluted in 35 μl of EB and pooled (total, 105 μl). Protein contamination was measured by NanoDrop 1000, and RNA contamination and genomic DNA shearing were evaluated by gel electrophoresis. The DNA and RNA concentrations were measured using the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer and Qubit double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) BR and Qubit RNA HS sssay kits, respectively (Invitrogen). Size selection of genomic DNA (at 10,000 bp) on the BluePippin system and sequencing on the PacBio Sequel system was conducted by the DNA Technologies and Expression Analysis Cores at the University of California Davis Genome Center. The genome was assembled with the filtered_subreads.fastq file using the default parameters of Canu (version 1.6) (53). B. pseudocatenulatum genomes were annotated and deposited in the Integrated Microbial Genome Expert Review annotation platform (GOLD project ID Gs0113979).

Fucosidase operon gene homologs in publicly available B. pseudocatenulatum genomes were identified with the PyParanoid pipeline (version 0.4.1) using default parameters (54). Briefly, the FASTA amino acid files of 319 higher-quality genomes were chosen to generate alignments with DIAMOND (version 0.9.24) (55). Homologous proteins were identified with Markov cluster algorithm (MCL 14 to 137) (56) and aligned with MUSCLE (v3.8.1551) (57). Hidden Markov models of each homologous protein alignment at homology cutoff at 95% amino acid identity were created with HMMER (v3.2.1) and propagated to additional Bifidobacterium genomes. The resulting matrix of homolog presence or absence was filtered to B. pseudocatenulatum strains of interest. A heatmap of predicted homolog copy number was visualized with Morpheus (accessed on 7 July 2020) (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/).

B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 fucosidase operon gene expression.

Expression of the SBP (Ga0224696_111933), α-fucosidase GH29 (Ga0224696_111927), and α-fucosidase GH95 (Ga0224696_111926) from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and the SBP (Ga0064049_111418) and α-fucosidase GH95 (Ga0064049_111413) from B. pseudocatenulatum SC585 were quantified during growth on 2′-FL. Primers were designed with the Primer-BLAST tool at NCBI (Table 5). The rnpA housekeeping gene from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585 (Ga0224696_112000 and Ga0064049_10607, respectively) was used for relative quantification (52). B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 was grown on mMRS supplemented with 2% (wt/vol) glucose or 2′-FL in a microplate reader, and cells were harvested at mid-log phase (OD600, 0.3 to 0.7), centrifuged at 21,130 rcf, and stored in RNAlater (Ambion) at −20°C. Samples were thawed on ice, centrifuged at 4°C at 21,130 rcf for 2 min, washed with 1 ml RNase-free 1× PBS, and recentrifuged. Samples were lysed with 250 μl of 50 mg ml−1 lysozyme and 120 U mutanolysin at 37°C for 20 min. Lysate was centrifuged at 4°C at 9,391 rcf for 1 min, supernatant was discarded, and pellets were processed with the RNAqueous total RNA isolation kit (Ambion) according to the kit’s instructions for bacterial sample preparation and RNA extraction. RNA integrity was evaluated by agarose electrophoresis (1.2% agarose gel [wt/vol]). Subsequently, DNA was removed using the Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion) according to the kit’s instruction with an extended 1-h DNase incubation. RNA was converted to total cDNA using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the kit’s instructions and stored at −20°C until use. A 20-μl reaction mixture containing 10 μl 2× SYBR premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus) master mix (Clontech), 0.4 μl of each primer (10 mM) (Table 5), 0.4 μl 50× ROX reference dye II, and 2 μl cDNA was run on a 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with a 20-s hold at 50°C, followed by 95°C for 10 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The threshold cycle (ΔΔCT method) was calculated and used to determine fold change in expression.

TABLE 5.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Purpose | Target | PCR primer (5′–3′) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multilocus sequence typinga | clpC | Fb | GAGTACCGTAAGTACATCGAG |

| R | TCCTCGTCGTCAAACAGGAAT | ||

| purF | F | GTCGGGTAGTCGCCATTG | |

| R | CACTCCAATTCCGACACCGA | ||

| gyrB | F | CATGCCGGCGGCAAGTTCG | |

| R | CCGAGCTTGGTCTTGGTCTG | ||

| fusA | F | ATCGGCATCATGGCTCACATCGAT | |

| R | CCAGCATCGGCTGAACACCCTT | ||

| ileS | F | CGGTATCGACATAGTCGGCG | |

| R | ATTCCGCGTTACCAGACCATG | ||

| rplB | F | AGGACGGCGTGCCGGCAA | |

| R | GCCGTGCGGGTGATCGAC | ||

| rpoB | F | GCATCCTCGTAGTTGTASCC | |

| R | GGCGAACTGATCCAGAACCA | ||

| B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 gene expression | rnpA (Ga0224696_112000) | F | GGTATCGCGAGAAGACATCGT |

| R | ACGGCATTACGCGTCACA | ||

| α-Fucosidase GH29 (Ga0224696_111927) | F | GCTCACTTCAACCCAATGCG | |

| R | TTCCATAGTCAGTTCCGCCG | ||

| α-Fucosidase GH95 (Ga0224696_111926) | F | GCTTGTCCAAAGCCACGATG | |

| R | TCCACTGTCTGATCCGTCCA | ||

| Substrate-binding protein (Ga0224696_111933) | F | TTCAACCGTGCTACGAACGA | |

| R | GCAGAATCACCGAATGCAGG | ||

| β-Galactosidase (Ga0224696_111500) | F | ACGTACAACCAGTTCACCCG | |

| R | ATGCGAGCACCTCAGTATCG | ||

| β-Galactosidase (Ga0224696_111924) | F | ACACCAATACCACGTTCGCA | |

| R | CGACCTTCTGAACGACGGTT | ||

| β-Galactosidase (Ga0224696_11522) | F | GACTACAACCCGGACCAGTG | |

| R | GAAATCGTACACGCCTTCGC | ||

| β-Galactosidase (Ga0224696_111652) | F | CAGCCGGAAGAAAACCGTTG | |

| R | TTCCGGGTGCTTTTCGTACA | ||

| B. pseudocatenulatum SC585 gene expression | rnpA (Ga0064049_10607) | F | GGTATCGCGAGAAGACATCGT |

| R | ACGGCATTACGCGTCACA | ||

| α-Fucosidase GH95 (Ga0064049_111413) | F | TCCGTGCAAGAGGTGGAATC | |

| R | GCGACACGTCCCATATCAGT | ||

| Substrate-binding protein (Ga0064049_111418) | F | TGCCGACCATTTCACCAAGT | |

| R | TTGCTCCATGCCTTGTCGAT | ||

| β-Galactosidase (Ga0064049_104415) | F | CGACTACGAGTCCGAATGGG | |

| R | GCTCGGCAATACGACCATCT | ||

| B. pseudocatenulatum SC585 gene expression | β-Galactosidase (Ga0064049_10859) | F | GATCGAACTGTTGAACGCCG |

| R | CGTCAAGCAGCGTAGCAATC | ||

| β-Galactosidase (Ga0064049_111411) | F | CGAATACACCGCCGATACCA | |

| R | TGCGATCCTGGTACGTTTCC | ||

| β-Galactosidase (Ga0064049_11171) | F | CACCAAACTGTTCCGCCAAG | |

| R | ATCGCCGTATCGGACTGTTC | ||

| B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 protein cloning | α-Fucosidase GH29 (Ga0224696_111927 | F | CACCATGAGCAATCCAACAAAT |

| R | TATCCGCACCACAGCCG | ||

| α-Fucosidase GH95 (Ga0224696_111926 | F | CACCATGAAACTCACATTCGATG | |

| R | ACGCCGGATGGTTCCCT | ||

| Substrate-binding protein (Ga0224696_111933 | F | CACCATGAAGGACACTAAAACTGC | |

| R | GTCGGCGTCGGTGGT | ||

| B. pseudocatenulatum SC585 protein cloning | Substrate-binding protein | F | CACCATGAGCCAGGCTAAGAGC |

| R | GTCGGCGTCAGTGGTGACCT | ||

Primers were modified from reference 49 for B. pseudocatenulatum DSM 20438.

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

RNA-Seq screen of B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 transcriptome.

For transcriptome screening, B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 was grown on basal MRS media supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) lactose, 2′-FL, or LNFP-1 in four biological replicates to understand differential expression due to various growth substrates. Cells were grown to mid-log phase with an A600 of 0.6 to 0.7 and stored in RNAprotect (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Cells were lysed with 250 μl (50 g/liter) lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 120 units of mutanolysin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). RNA was extracted with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) and DNase treated twice. rRNA was depleted with the RiboMinus transcriptome isolation kit, bacteria (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), while the integrity of RNA was assayed using the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Barcode-indexed transcriptome-sequencing (RNA-Seq) libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with paired-end 75-bp reads. Sequences were processed with CLCBio Genomics Workbench (CLC Bio, Denmark), and reads were trimmed (maximum of 2 ambiguous base pairs) and deleted if the quality scores were below 0.5. Sequences were mapped to the B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 genome. Reads per kilobase per million (RPKM) values were calculated, and data were log2 transformed and normalized by totals. Gene expression levels in LNFP-1 and 2′-FL were compared to lactose-grown cells, and statistically significant changes were analyzed using Baggerley's test with a false-discovery rate (FDR) P value of ≤0.05.

Cloning and expression of B. pseudocatenulatum fucosidase operon genes.

The SBP (Ga0224696_111933), α-fucosidase GH29 (Ga0224696_111927), and α-fucosidase GH95 (Ga0224696_111926) from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and the SBP (Ga0064049_111418) from B. pseudocatenulatum SP585 were cloned using the Champion pET directional TOPO expression kits (Invitrogen) according to the kit’s instructions unless noted otherwise. The SBP forward primers (listed in Table 5) start with the first nucleotide (MP80 nucleotide 88 and SC585 nucleotide 91) after the predicted signal and transmembrane domains preceded by the CACC sequence and ATG start codon. A 50-μl reaction mixture with 1× Phusion HF buffer, 200 mM dNTPs, 0.5 mM each primer, 100 to 150 ng genomic DNA, and 1 U Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) was used. Cycling parameters are as follows: 30 s at 98°C, followed by 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 64°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s, with a final extension period of 5 min at 72°C. PCR amplicons were purified with QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) or DNA clean and concentrator kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Purified PCR products were cloned into the pET101 (MP80) or pET102 (SC585) dTOPO vector, transformed into One Shot Top10 chemically competent Escherichia coli and plated onto LB agar containing 100 μg ml−1 carbenicillin. Plasmid DNA from putative transformants was isolated using the QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen). Clones were confirmed by PCR prior to transformation into chemically competent BL21star (DE3) One Shot E. coli and plated on LB agar containing 100 μg ml−1 carbenicillin. Confirmed transformants were stored in 25% (vol/vol) glycerol at −80°C.

Inoculate 200 ml of LB broth containing 100 μg ml−1 carbenicillin and 1% (wt/vol) glucose with 4 ml overnight cultures of BL21star transformants and incubated at 37°C with agitation at 225 rpm. At an approximately OD600 of 0.6, protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside and incubated 18 to 22 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,220 rcf for 20 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were lysed in 4 ml 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, containing 90 μl 50 mg ml−1 lysozyme and incubated for 30 min on ice. Solution was vortexed at maximum speed for 2 min, 45 μl DNase I solution (Roche) and 5 μl RNase A (Epicentre) were added, and it was incubated for 15 min on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 rcf for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatants were combined with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose (Qiagen) at a ratio of 4:1 and incubated on a tilt table for 1 h at 4°C. Lysate-agarose was washed twice with 10 ml of 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, in a 5-ml disposable gravity chromatography column (Qiagen). Proteins were eluted with 4 × 500 μl of 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0. Proteins were visualized by SDS-PAGE using a 7.5% 2× TGX mini-Protean gel (Bio-Rad). Imidazole buffer was exchanged for 1× PBS using Amicon Ultra 0.5-ml centrifugal filter units with a 3-kDA cutoff (EMD Millipore). Purified proteins were stored in PBS with 25% (vol/vol) glycerol at −20°C.

B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585 substrate-binding, protein-binding specificity.

An approximately 8-μl reaction mixture containing 10 μM substrate-binding protein and 1 μM each HMO (Tables S4 and S5 in the supplemental material) was analyzed by a catch-and-release electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry assay using a Synapt G2S ESI quadrupole-ion mobility separation-time of flight mass spectrometry (TOF MS) (Waters) equipped with a nanoflow electrospray ionization source with minor modifications (58). Briefly, a capillary voltage of 1.0 kV and a cone voltage of 30 kV (in negative ion mode) were applied, and the source block temperature was maintained at 60°C for electrospray ionization. Ion transmission was carried out with trap voltages of 10 to 80 V and transfer voltages of 2 to 60 V. The ion mobility separation parameters were optimized for each HMO isomer set as follows: trap gas flow rate at 6 ml min−1, helium cell gas flow rate at 150 to 180 ml min−1, ion mobility gas flow rate at 50 to 90 ml min−1, trap direct-current bias at 50 V, ion mobility wave velocity at 400 to 1,000 m s−1, and ion mobility wave height at 15 to 40 V. For ion mobility separation, N2 at 341 Pa was used. Data acquisition and processing were carried out using MassLynx (version 4.1; Waters).

Affinities of the HMOs were ranked according to the abundances of ligands released (as ions) from the protein complexes in the CaR-ESI-MS measurements. The HMOs were assigned as “low/no binding” when signal for their released ions was not detected or was detected with a low signal-to-noise ratio (i.e., S/N ≤ 3). HMOs for which the S/N of the released ions was ≥70 were assigned as “strong binding.” HMO ligands with intermediate S/N (i.e., 3 ≤ S/N ≤ 70) were assigned as “medium binding.”

B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 α-fucosidase GH29 and GH95 HMO substrate specificity.

A 1.5-μl (2 mg ml−1) sample of a reduced HMO pool was digested with 2 mg ml−1 of purified α-fucosidase GH29 and GH95 (described above) in 10 μl of 0.1 M NH4 acetate buffer. Reaction mixtures were incubated at each enzyme’s optimal pH, temperature, and duration (data not shown) and stored at −80°C until identification of undigested HMOs (described below).

Glycoprofiling of HMOs by nano-HPLC-ChIP-TOF mass spectrometry.

Cell-free supernatants and undigested HMOs were recovered, reduced, and desalted by solid-phase extraction on graphitized carbon cartridges as previously described (8). HMOs analytes were separated on a 1200 Infinity series high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) unit (Agilent Technologies) and detected on a 6220 series TOF LC/MS unit (Agilent Technologies), and data were processed using the MassHunter qualitative analysis software (version B.06.01; Agilent) as previously described (7, 59, 60).

Data availability.

The sequenced B. pseudocatenulatum genomes were annotated and deposited in the Integrated Microbial Genome Expert Review annotation platform (GOLD project ID Gs0113979). Sequenced strains are located at associated IMG/JGI analysis IDs SC585 (Ga0064049), MP80 (Ga0224696), JCM7040 (Ga0024098), JCM11661 (Ga0064497), L15 (Ga0064499), and GST210 (Ga0064498) (https://img.jgi.doe.gov/). Additional genome accessions are provided in Table S3. RNA-Seq data were deposited in the NCBI GEO repository (accession no. GSE175820).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Juliana de Moura Bell, Joshua Cohen, and Daniela Barile for providing purified human milk oligosaccharides and Xi Chen for providing the LNFP1. The B. pseudocatenulatum strain L15 was kindly provided by Eva Vlková.

This study was funded in part by UC Davis RISE program, National Institutes of Health awards AT007079 and AT008759 (D.A.M.), and the Peter J. Shields Endowed Chair in Dairy Food Science (D.A.M.).

G.S. and D.A.M. designed the study. G.S., J.L.H., B.E.H., and D.A.M. wrote the manuscript. D.A.M. secured funding for this study. G.S. conducted all experiments except as noted. J.L.H. cloned and purified B. pseudocatenulatum SC585’s SBP. J.L.H. and B.E.H. conducted qRT-PCR of bacteria grown on 2′-FL. B.E.H. and S.W. performed RNA-Seq analysis. C.F.M. assembled the PacBio B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 genome. J.A.L., B.E.H., and C.M.S. analyzed the 2′-FL metabolite profile of B. pseudocatenulatum MP80. N.M.J. conducted the comparative genomics analysis. E.G. and C.B.L. analyzed the glycoprofiling of pooled HMO growths. A.E., L.N., and J.S.K. analyzed the binding specificity of SBP from B. pseudocatenulatum MP80 and SC585. All authors read, edited, and approved submission of the manuscript for publication.

D.A.M. and C.B.L. are cofounders of Evolve Biosystems and BCD Biosciences, companies with products for addressing gut health. B.E.H. currently works for Evolve Biosystems. J.L.H. currently works for Mascoma, LLC. No companies played a role in the origination, design, execution, interpretation, or publication of this work. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

David A. Mills, Email: damills@ucdavis.edu.

Edward G. Dudley, The Pennsylvania State University

REFERENCES

- 1.Smilowitz JT, O'Sullivan A, Barile D, German JB, Lönnerdal B, Slupsky CM. 2013. The human milk metabolome reveals diverse oligosaccharide profiles. J Nutr 143:1709–1718. 10.3945/jn.113.178772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ninonuevo MR, Park Y, Yin H, Zhang J, Ward RE, Clowers BH, German JB, Freeman SL, Killeen K, Grimm R, Lebrilla CB. 2006. A strategy for annotating the human milk glycome. J Agric Food Chem 54:7471–7480. 10.1021/jf0615810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Leoz MLA, Kalanetra KM, Bokulich NA, Strum JS, Underwood MA, German JB, Mills DA, Lebrilla CB. 2015. Human milk glycomics and gut microbial genomics in infant feces show a correlation between human milk oligosaccharides and gut microbiota: a proof-of-concept study. J Proteome Res 14:491–502. 10.1021/pr500759e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LoCascio RG, Ninonuevo MR, Freeman SL, Sela DA, Grimm R, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA, German JB. 2007. Glycoprofiling of bifidobacterial consumption of human milk oligosaccharides demonstrates strain specific, preferential consumption of small chain glycans secreted in early human lactation. J Agric Food Chem 55:8914–8919. 10.1021/jf0710480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrido D, Ruiz-Moyano S, Lemay DG, Sela DA, German JB, Mills DA. 2015. Comparative transcriptomics reveals key differences in the response to milk oligosaccharides of infant gut-associated bifidobacteria. Sci Rep 5:13517. 10.1038/srep13517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thongaram T, Hoeflinger JL, Chow J, Miller MJ. 2017. Human milk oligosaccharide consumption by probiotic and human-associated bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. J Dairy Sci 100:7825–7833. 10.3168/jds.2017-12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrido D, Ruiz-Moyano S, Kirmiz N, Davis JC, Totten SM, Lemay DG, Ugalde JA, German JB, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. 2016. A novel gene cluster allows preferential utilization of fucosylated milk oligosaccharides in Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum SC596. Sci Rep 6:35045. 10.1038/srep35045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz-Moyano S, Totten SM, Garrido DA, Smilowitz JT, German JB, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. 2013. Variation in consumption of human milk oligosaccharides by infant gut-associated strains of Bifidobacterium breve. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:6040–6049. 10.1128/AEM.01843-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunesova V, Lacroix C, Schwab C. 2016. Fucosyllactose and L-fucose utilization of infant Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense. BMC Microbiol 16:248. 10.1186/s12866-016-0867-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katoh T, Ojima MN, Sakanaka M, Ashida H, Gotoh A, Katayama T. 2020. Enzymatic adaptation of Bifidobacterium bifidum to host glycans, viewed from glycoside hydrolyases and carbohydrate-binding modules. Microorganisms 8:481. 10.3390/microorganisms8040481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotoh A, Katoh T, Sakanaka M, Ling Y, Yamada C, Asakuma S, Urashima T, Tomabechi Y, Katayama-Ikegami A, Kurihara S, Yamamoto K, Harata G, He F, Hirose J, Kitaoka M, Okuda S, Katayama T. 2018. Sharing of human milk oligosaccharides degradants within bifidobacterial communities in faecal cultures supplemented with Bifidobacterium bifidum. Sci Rep 8:13958. 10.1038/s41598-018-32080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turroni F, Duranti S, Milani C, Lugli GA, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2019. Bifidobacterium bifidum: a key member of the early human gut microbiota. Microorganisms 7:544. 10.3390/microorganisms7110544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcobal A, Barboza M, Sonnenburg ED, Pudlo N, Martens EC, Desai P, Lebrilla CB, Weimer BC, Mills DA, German JB, Sonnenburg JL. 2011. Bacteroides in the infant gut consume milk oligosaccharides via mucus-utilization pathways. Cell Host Microbe 10:507–514. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostopoulos I, Elzinga J, Ottman N, Klievink JT, Blijenberg B, Aalvink S, Boeren S, Mank M, Knol J, de Vos WM, Belzer C. 2020. Akkermansia muciniphila uses human milk oligosaccharides to thrive in the early life conditions in vitro. Sci Rep 10:14330. 10.1038/s41598-020-71113-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pichler MJ, Yamada C, Shuoker B, Alvarez-Silva C, Gotoh A, Leth ML, Schoof E, Katoh T, Sakanaka M, Katayama T, Jin C, Karlsson NG, Arumugam M, Fushinobu S, Abou Hachem M. 2020. Butyrate producing colonic Clostridiales metabolise human milk oligosaccharides and cross feed on mucin via conserved pathways. Nat Commun 11:3285. 10.1038/s41467-020-17075-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuki T, Yahagi K, Mori H, Matsumoto H, Hara T, Tajima S, Ogawa E, Kodama H, Yamamoto K, Yamada T, Matsumoto S, Kurokawa K. 2016. A key genetic factor for fucosyllactose utilization affects infant gut microbiota development. Nat Commun 7:11939. 10.1038/ncomms11939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duar RM, Henrick BM, Casaburi G, Frese SA. 2020. Integrating the ecosystem services framework to define dysbiosis of the breastfed infant gut: the role of B. infantis and human milk oligosaccharides. Front Nutr 7:33. 10.3389/fnut.2020.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sela DA, Chapman J, Adeuya A, Kim JH, Chen F, Whitehead TR, Lapidus A, Rokhsar DS, Lebrilla CB, German JB, Price NP, Richardson PM, Mills DA. 2008. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis reveals adaptations for milk utilization within the infant microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:18964–18969. 10.1073/pnas.0809584105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James K, Motherway MO, Bottacini F, van Sinderen D. 2016. Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 metabolises the human milk oligosaccharides lacto-N-tetraose and lacto-N-neo-tetraose through overlapping, yet distinct pathways. Sci Rep 6:38560. 10.1038/srep38560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wada J, Ando T, Kiyohara M, Ashida H, Kitaoka M, Yamaguchi M, Kumagai H, Katayama T, Yamamoto K. 2008. Bifidobacterium bifidum lacto-N-biosidase, a critical enzyme for the degradation of human milk oligosaccharides with a type 1 structure. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:3996–4004. 10.1128/AEM.00149-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashida H, Miyake A, Kiyohara M, Wada J, Yoshida E, Kumagai H, Katayama T, Yamamoto K. 2009. Two distinct alpha-L-fucosidases from Bifidobacterium bifidum are essential for the utilization of fucosylated milk oligosaccharides and glycoconjugates. Glycobiology 19:1010–1017. 10.1093/glycob/cwp082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katayama T, Sakuma A, Kimura T, Makimura Y, Hiratake J, Sakata K, Yamanoi T, Kumagai H, Yamamoto K. 2004. Molecular cloning and characterization of Bifidobacterium bifidum 1,2-alpha-L-fucosidase (AfcA), a novel inverting glycosidase (glycoside hydrolase family 95). J Bacteriol 186:4885–4893. 10.1128/JB.186.15.4885-4893.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shuhaimi M, Ali AM, Saleh NM, Yazid AM. 2002. Classification of Bifidobacterium isolates from infant faeces using PCR-based and 16S rDNA partial sequences analysis methods. Bioscience Microflora 21:155–161. 10.12938/bifidus1996.21.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turroni F, Peano C, Pass DA, Foroni E, Severgnini M, Claesson MJ, Kerr C, Hourihane J, Murray D, Fuligni F, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, De Bellis G, O'Toole PW, van Sinderen D, Marchesi JR, Ventura M. 2012. Diversity of bifidobacteria within the infant gut microbiota. PLoS One 7:e36957. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simeoni U, Berger B, Junick J, Blaut M, Pecquet S, Rezzonico E, Grathwohl D, Sprenger N, Brüssow H, Szajewska H, Bartoli JM, Brevaut-Malaty V, Borszewska-Kornacka M, Feleszko W, François P, Gire C, Leclaire M, Maurin JM, Schmidt S, Skórka A, Squizzaro C, Verdot JJ, Study Team. 2016. Gut microbiota analysis reveals a marked shift to bifidobacteria by a starter infant formula containing a synbiotic of bovine milk-derived oligosaccharides and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis CNCM I-3446. Environ Microbiol 18:2185–2195. 10.1111/1462-2920.13144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yassour M, Vatanen T, Siljander H, Hämäläinen A-M, Härkönen T, Ryhänen SJ, Franzosa EA, Vlamakis H, Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Lander ES, Knip M, Xavier RJ, DIABIMMUNE Study Group. 2016. Natural history of the infant gut microbiome and impact of antibiotic treatment on bacterial strain diversity and stability. Sci Transl Med 8:343ra81. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawson MAE, O'Neill IJ, Kujawska M, Gowrinadh Javvadi S, Wijeyesekera A, Flegg Z, Chalklen L, Hall LJ. 2020. Breast milk-derived human milk oligosaccharides promote Bifidobacterium interactions within a single ecosystem. ISME J 14:635–648. 10.1038/s41396-019-0553-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turroni F, Foroni E, Pizzetti P, Giubellini V, Ribbera A, Merusi P, Cagnasso P, Bizzarri B, de'Angelis GL, Shanahan F, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2009. Exploring the diversity of the bifidobacterial population in the human intestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:1534–1545. 10.1128/AEM.02216-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Junick J, Blaut M. 2012. Quantification of human fecal Bifidobacterium species by use of quantitative real-time PCR analysis targeting the groEL gene. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2613–2622. 10.1128/AEM.07749-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milani C, Mangifesta M, Mancabelli L, Lugli GA, James K, Duranti S, Turroni F, Ferrario C, Ossiprandi MC, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2017. Unveiling bifidobacterial biogeography across the mammalian branch of the tree of life. ISME J 11:2834–2847. 10.1038/ismej.2017.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI. 2012. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 486:222–227. 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odamaki T, Kato K, Sugahara H, Hashikura N, Takahashi S, Xiao J-Z, Abe F, Osawa R. 2016. Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: a cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol 16:90. 10.1186/s12866-016-0708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis ZT, Totten SM, Smilowitz JT, Popovic M, Parker E, Lemay DG, Van Tassell ML, Miller MJ, Jin Y-S, German JB, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. 2015. Maternal fucosyltransferase 2 status affects the gut bifidobacterial communities of breastfed infants. Microbiome 3:13. 10.1186/s40168-015-0071-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bunešová V, Vlková E, Killer J, Rada V, Ročková Š. 2012. Identification of Bifidobacterium strains from faeces of lambs. Small Ruminant Res 105:355–360. 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2011.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smilowitz JT, Lemay DG, Kalanetra KM, Chin EL, Zivkovic AM, Breck MA, German JB, Mills DA, Slupsky C, Barile D. 2017. Tolerability and safety of the intake of bovine milk oligosaccharides extracted from cheese whey in healthy human adults. J Nutr Sci 6:e6. 10.1017/jns.2017.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sela DA, Garrido D, Lerno L, Wu S, Tan K, Eom H-J, Joachimiak A, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. 2012. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 α-fucosidases are active on fucosylated human milk oligosaccharides. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:795–803. 10.1128/AEM.06762-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishimoto M, Kitaoka M. 2007. Identification of N-acetylhexosamine 1-kinase in the complete lacto-N-biose I/galacto-N-biose metabolic pathway in Bifidobacterium longum. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:6444–6449. 10.1128/AEM.01425-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Hawiet A, Chen Y, Shams-Ud-Doha K, Kitova EN, Kitov PI, Bode L, Hage N, Falcone FH, Klassen JS. 2018. Screening natural libraries of human milk oligosaccharides against lectins using CaR-ESI-MS. Analyst 143:536–548. 10.1039/c7an01397c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Hawiet A, Chen Y, Shams-Ud-Doha K, Kitova EN, St-Pierre Y, Klassen JS. 2017. High-throughput label- and immobilization-free screening of human milk oligosaccharides against lectins. Anal Chem 89:8713–8722. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katayama T. 2016. Host-derived glycans serve as selected nutrients for the gut microbe: human milk oligosaccharides and bifidobacteria. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 80:621–632. 10.1080/09168451.2015.1132153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turroni F, Milani C, Duranti S, Mahony J, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2018. Glycan utilization and cross-feeding activities by Bifidobacteria. Trends Microbiol 26:339–350. 10.1016/j.tim.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomson P, Medina DA, Garrido D. 2018. Human milk oligosaccharides and infant gut bifidobacteria: molecular strategies for their utilization. Food Microbiol 75:37–46. 10.1016/j.fm.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LoCascio RG, Desai P, Sela DA, Weimer B, Mills DA. 2010. Broad conservation of milk utilization genes in Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis as revealed by comparative genomic hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:7373–7381. 10.1128/AEM.00675-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asakuma S, Hatakeyama E, Urashima T, Yoshida E, Katayama T, Yamamoto K, Kumagai H, Ashida H, Hirose J, Kitaoka M. 2011. Physiology of consumption of human milk oligosaccharides by infant gut-associated bifidobacteria. J Biol Chem 286:34583–34592. 10.1074/jbc.M111.248138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwak M-J, Kwon S-K, Yoon J-K, Song JY, Seo J-G, Chung MJ, Kim JF. 2016. Evolutionary architecture of the infant-adapted group of Bifidobacterium species associated with the probiotic function. Syst Appl Microbiol 39:429–439. 10.1016/j.syapm.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sela DA. 2011. Bifidobacterial utilization of human milk oligosaccharides. Int J Food Microbiol 149:58–64. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garrido D, Kim JH, German JB, Raybould HE, Mills DA. 2011. Oligosaccharide binding proteins from Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis reveal a preference for host glycans. PLoS One 6:e17315. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakanaka M, Hansen ME, Gotoh A, Katoh T, Yoshida K, Odamaki T, Yachi H, Sugiyama Y, Kurihara S, Hirose J, Urashima T, Xiao J-Z, Kitaoka M, Fukiya S, Yokota A, Lo Leggio L, Abou Hachem M, Katayama T. 2019. Evolutionary adaptation in fucosyllactose uptake systems supports bifidobacteria-infant symbiosis. Sci Adv 5:eaaw7696. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delétoile A, Passet V, Aires J, Chambaud I, Butel M-J, Smokvina T, Brisse S. 2010. Species delineation and clonal diversity in four Bifidobacterium species as revealed by multilocus sequencing. Res Microbiol 161:82–90. 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gnoth MJ, Kunz C, Kinne-Saffran E, Rudloff S. 2000. Human milk oligosaccharides are minimally digested in vitro. J Nutr 130:3014–3020. 10.1093/jn/130.12.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]