Abstract

Difficulties with social interactions and communication that characterize autism persist in adulthood. While social participation in adulthood is often marked by social isolation and limited close friendships, this qualitative study describes the range of social participation activities and community contacts, from acquaintances to close relationships, that contributed to connection from the perspective of 40 autistic adults. Qualitative data from interviews around social and community involvement were analyzed and revealed five main contexts where social participation occurred: vocational contexts, neighborhoods, common interest groups, support services and inclusive environments, and online networks and apps. Implications for practice to support a range of social participation include engaging in newer social networking avenues, as well as traditional paths through employment and support services.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Social participation, Adulthood, Connection, Social networking, Employment

Introduction

The diagnosis of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has risen dramatically, from 1 in 150 8-year-olds in 2002 to 1 in 54 in 2016 (Center for Disease Control, 2020). While prevalence rates are most closely monitored in children, ASD is a lifelong disorder characterized by social and communication impairments as well as repeated and restricted patterns of behavior (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). While other symptoms of autism often plateau or improve in adulthood, characteristic social interaction difficulties persist and are potential contributors to lower rates of normative adult outcomes reported in the literature that involve social participation, friendships, or close relationships (Tobin et al., 2014).

Social Relationships in Childhood and Adolescence

Social participation includes the size and quality of social networks (Wong & Solomon, 2002), while friendship is defined as emotional relationships people form with another characterized by mutual affection, companionship, and reciprocal support and interaction (Freeman & Kasari, 1998; Parker & Gottman, 1989, as cited in Bauminger et al., 2008). Yet the importance of the size or number of social contacts related to well-being may vary through different life stages or the lifespan. Parker and Asher’s (1993) research with neurotypical children, meaning those who are typically developing, highlighted the importance of the need for only one close friend in childhood for better well-being. In this study, less loneliness was associated with having at least one close friend, even among children who were not accepted in their classroom. Loneliness denotes a negative emotional state from the subjective appraisal that the quality or amount of social interaction desired does not match one’s actual social experience (Elmose, 2020; Peplau & Perlman, 1982). This is different from solitude, which may be preferred and important (Elmose, 2020; Mazurek, 2014; Peplau & Perlman, 1982). In the literature, loneliness also differs from social isolation, which in contrast to the subjective appraisal of one’s social relationship status, objectively examines one’s amount of social contact (Mazurek, 2014).

There is some support for the similar importance of having a close friend as potential protection against feelings of loneliness in autistic children. Autistic children identified quality friendships in a small circle of supportive friends as an important measure of their well-being, and the preference to have a few close friends who can be trusted (Lam et al., 2020). Similarly, Rotheram-Fuller et al. (2010) identified autistic children who had at least one reciprocal friendship, defined in the research as two children both nominating one another as friends (Kasari et al., 2011), also had greater peer acceptance. While these close friendships may have important implications, they are less frequent. A study of parent reports of friendships indicated 34% of autistic children had at least one good friend, compared to 71% of children with other disabilities and 93% of neurotypical children without disabilities (Rowley et al., 2012). Having one close friend may offer some protection against loneliness, although reciprocal friendships may be less common among autistic children compared to neurotypical children.

Social and communication impairments are often tied to difficulties with developing these reciprocal friendships in childhood. In the regular classroom, autistic children may experience the social structure of inclusion, but often still appear on the fringe of social activities, with higher rates of loneliness and poorer friendship quality than their neurotypical classmates (Kasari et al., 2011; Locke et al., 2010). For example, in a study examining playground observations as well as self, teacher, and classmate reports, Kasari et al. (2011) found autistic children were more likely to be socially isolated, meaning not a part of any social group in the classroom, or identified as only having peripheral social status compared to their neurotypical peers.

Other findings using measures of friendship quality, which evaluates the degree of companionship, help, security, and closeness between an identified friend, are often lower for autistic children and adolescents (Kasari et al., 2011; Locke et al., 2010). Friendship quality, however, is not commensurate with friendship satisfaction, as satisfaction with friendship may be fulfilled through a few friends or from friends outside the school setting (Petrina et al., 2017). Calder et al. (2012) noted autistic children were generally satisfied with their level of friendship. Petrina et al. (2017) also found rates of friendship satisfaction were similar for autistic and non-autistic elementary school children, with the level of perceived friendship reciprocated by named neurotypical peer friends in the study. These named friend pairs were often connected through common interests in childhood which carried into adolescence. Available survey data from Orsmond et al. (2004) on peer relationships in autistic adolescents found 20.9% had at least one friendship with shared activities, but only 8.1% had one close reciprocal friendship, and almost half had no peer relationships at all.

Social Relationships in Adulthood

When examining the quality of social networks in adulthood, including peer relationships and friendships, systematic reviews of the available research report adults across the spectrum have poorer social relationships than both neurotypically developing peers and those with intellectual disabilities, learning disabilities, and speech language disorders (Gotham et al., 2015; Kirby et al., 2016; Levy & Perry, 2011; Orsmond et al., 2013; Roux et al., 2013). Unlike childhood, where autistic children are more likely to initiate engagement with neurotypical peers in the classroom rather than with other children with disabilities (Bauminger et al., 2003), in adulthood there is some support for a preference for relationships with others on the spectrum (Milton & Sims, 2016; Morrison et al., 2020). For example, Morrison et al. (2020) conducted a study in which they paired autistic and neurotypical adults for a 5-minute social interaction. Researchers found that autistic adults preferred to interact with other autistic adults and were more likely to reveal more about themselves to them compared to neurotypical participants (Morrison et al., 2020). Sedgewick et al. (2019) compared ratings of close relationships between 532 autistic and 417 non-autistic adults and found no significant differences when rating their relationship with a long-term partner or spouse, indicating that autistic adults may feel the same level of closeness to a marriage or long-term partner as neurotypical adults (Sedgewick et al., 2019). Similarly, in survey research with 108 autistic adults, 60% reported having a close or best friend, which was significantly related to less loneliness (Mazurek, 2014). Furthermore, in a qualitative study of 15 adults and nine caretakers of autistic adults, some participants described having a limited number of close friendships as important for aging well (Hwang et al., 2017), which may indicate satisfaction with a few close relationships.

In the neurotypical population, however, particularly with aging in adulthood, the benefits of social participation shift away from the importance of having one close friend. A number of researchers have identified having a broad network of social contacts in adulthood as a key contributor to factors supporting healthy aging, including mental health (Achat et al., 1998; Michael et al., 1999; Uchino et al., 2001). In older adulthood, larger social networks are related to better global cognition (Kelly et al., 2017), while perceived social connectedness is significantly related to self-reported health status (Ashida, 2008). Much less is known about the impact of the size or extent of social networks in autistic adults. In the Mazurek (2014) survey study, number of friends was an important predictor of better self-esteem and less depression and anxiety, suggesting quality and quantity matters. However, social participation outcomes have previously been measured by assessing the number of friendships, frequency of contact or activities with friends, or even a dichotomous measure of the presence or absence of social activity within a defined period, such as the past month or past year. These measures may not accurately capture social participation, or the perceived size and quality of social contacts (Myers et al., 2015; Orsmond et al., 2013; Steinhausen et al., 2016; Tint et al., 2016). For example, in a qualitative study of 38 autistic adults examining factors influencing quality of life, McConachie et al. (2020) found that some participants described difficulty with engaging in social interactions, while others described a lack of desire for friendships altogether, representing a range of social participation preferences.

With differences between autistic and neurotypical individuals in mind, the neurodiversity perspective challenges the use of normative outcomes as the benchmark for success in adulthood. A neurodiverse framework acknowledges the difficulties the autism community faces, while also presenting the commonalities that characterize autistic individuals as strengths and differences rather than inherent deficits (Baron-Cohen, 2017). Social, environmental, or attitudinal barriers, however, can magnify the extent to which these differences interfere with the individual being able to engage in typical participation outcomes. Similarly, as opposed to a medical model focused on deficits, viewing autism as an identity and culture replaces typically held beliefs about social impairments and difficulties with the concept that individuals on the spectrum possess social skills, but they may be different than those of neurotypical individuals (Herrick & Datti, 2020).

With this perspective in mind, friendships and social participation may look different for individuals on the spectrum. For example, autistic adults may plan their social interactions to include less face-to-face contact to meet their social needs without being overwhelmed (Elmose, 2020). Attending concerts, movies, or sporting events may be preferred activities because these activities are more scripted and require less verbal communication. In other cases, individuals may appear to others to be on the periphery of social interactions and not involved, but still themselves consider the activity as social and participating with others (Bagatell, 2010). Additionally, online social networking platforms may serve as an important facilitator of friendship development for autistic individuals (Brownlow et al., 2015). These online friendships may appear to be of lower quality when assessed using a neurotypical model of friendship, but autistic individuals may engage in meaningful and important relationships through the online setting (Brownlow et al., 2015). Furthermore, Mazurek (2013) found autistic adults who used social networking platforms were more likely to report having a close friend compared to those who did not use online social networking.

Range of Social Participation

For all individuals, there are different levels of social participation and engagement. Social connections can range from casual encounters, such as greeting a neighbor or stranger, to having acquaintances with those who are familiar but not known well, to close friendships and relationships where individuals feel known and accepted (Wood et al., 2015). While past research has primarily focused on close friendships and relationships, a better understanding of the range of social participation experiences is needed to determine potential benefits in adulthood. Research on healthy aging in adulthood stresses the importance of making social connections and forming these connections in a variety of ways that are personally meaningful (Ashida, 2008; Michael et al., 1999; Uchino et al., 2001). Within the autism community, there is a call to research the strengths and unique perspectives of individuals to add validity and depth to the outcomes measured (Henniger & Taylor, 2012; Howlin & Taylor, 2015). Research on the individual subjective experience of social participation of autistic adults will meet this gap (Tint et al., 2016).

Purpose of the Study

There is little qualitative research on the breadth of social interactions and experiences among autistic adults, and how these different types of engagements are perceived by autistic adults. Beyond the normative ways of thinking about friendships, more information is needed regarding which social connections adults with autism are engaging in that are meaningful, and how they are making connections they feel are important to them. Understanding where meaningful social participation occurs, and the contexts that frame or promote these interactions, are important for developing client-centered services and client-identified goals (McCollum et al., 2016). Seeking input from the autistic individual on meaningful social activities and connections both empowers the individual to provide information as an expert on the experience and can facilitate a deeper understanding of which activities and interactions are significant (McCollum et al., 2016; Tobin et al., 2014). The purpose of this study is to describe the range of social participation experiences of autistic adults to better understand, from the individual’s perspective, where and how these meaningful social contacts occur.

Methods

This study draws on data collected as part of a larger mixed methods project aimed at understanding the community participation of autistic adults. The qualitative data describing social interactions and community connections in the larger study are the focus of this analysis.

Participants

Participants were recruited through an autism research registry affiliated with a university in the southeastern United States. This registry maintains a list of individuals with autism who have indicated interest in participating in autism research, and contacts individuals on the registry based on the study’s inclusion criteria. The registry contacted potential participants for the current study who could communicate (verbally or nonverbally) in English and had an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 70 or above on record with the registry. IQ was confirmed through psychological reports previously submitted to the registry or through a previous diagnosis of Asperger’s Disorder. Recruitment invitations were sent from the registry via mail and email in groups of 30 by geographic catchment area, with approximately a 20% response rate. Interested participants could respond to the registry or the principal investigator. Research team members contacted interested individuals to confirm their ability to complete two 60-minute interviews and that a typical week of community participation could be captured during the study week.

Procedures

Data were collected primarily using semi-structured interviews to assess the importance of community activities, feelings of belonging, and social connectedness from the individual’s perspective. Over the 2-year study period (2019–2021), the majority of interviews (n = 29) were completed in person with the research team traveling to the participant’s community area prior to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data collection after March 2020 (n = 11) was completed via Zoom and required that participants have reliable internet access. These interviews included additional questions regarding how participants’ social and community participation changed since the onset of COVID-19.

Each interview was conducted after the participant finished a week-long data tracking process recording community activities through participants carrying a GPS tracking device and completing a daily travel diary. No intervention was included in the larger study. The interviews focused on the activities that occurred during the week, facilitators and barriers to participation, the importance of different locations visited in the community, and feelings of belonging and social support in the community. Primary study questions such as “Where do you typically see your friends?” “Are there any activities you wish you were more involved with?” “Do you feel a part of your community?” and “Who is your biggest form of social support?” often prompted discussion related to social participation. Prior to the current study, pilot testing of each project component and the interview guide was completed with 12 autistic adults which resulted in some modifications to the questions and response style of the measures used in the larger study.

The university Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of the study. Written consent was received from participants or their guardians, including consent to record the interviews. Participants with consenting guardians (n = 5) verbally assented to participation. One participant was minimally verbal but was able to respond through confirming his family member’s responses to questions. The tracking data of community activities was used to triangulate the report of social activities if they occurred during the tracking week. After study participation, a summary of interview data including general themes of the interview and question responses was sent to each participant. Participants were asked to confirm that the information was accurate or provide changes as necessary as a form of member checking.

Analysis

All authors were involved with the data collection, interviews, and analysis process. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded using open coding methods by the principal investigator and two master’s level research assistants (RA) on the project. All members of the research team are clinical rehabilitation and mental health counselors with experience working with autistic individuals through research, service provision, and/or as an immediate family member.

Interview data were analyzed using a multi-step approach. First, interviewers recorded detailed notes on the semi-structured interview guide during or immediately following the study visit to capture participant responses to key questions. When approximately half of the sample had completed the study, the research team met to reflect on common threads noted throughout the data collection process from these notes. Potential codes and emerging themes were identified in this process, with a particular emphasis on ten case studies. This initial conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) of the ten cases highlighted social networking facilitated activities, vocational related opportunities, and the importance of personal and formalized supports. A matrix was constructed that included participant demographic information, emerging codes and potential themes, and illustrative quotes (Averill, 2002; Hamilton & Maietta, 2017).

This initial analysis of ten case studies served as the foundation for further analysis. Transcripts were then independently reviewed by two team members using line by line coding for the presence of the initial representative codes or emergence of new codes and themes. The study team met regularly to review findings and compare coding results, with high agreement in coding. Sharing findings from the coding process often confirmed and expanded some of the previously identified experiences from the ten cases but also noted differences in the level of engagement or meaning of interactions and preferences across the spectrum of participation, prompting a return to the review of the data. After data collection was nearly complete, the matrix and key quotes were revisited, and the team applied a neurodiversity framework to analyze the quotes. Using a neurodiversity approach resulted in a refined focus on the range and meaning of social participation reported across participants, reframing differences in social participation as such rather than emphasizing differences as deficits. For example, during the first round of data analysis, relying exclusively on online social connections was coded as a barrier to social participation. When the team applied the neurodiversity framework, however, quotes regarding online social connections were re-coded as an important way individuals were maintaining social contacts with friends living in other geographic areas.

Results

Participants

Forty adults participated in the study. Participant demographics are described in Table 1. Participant age had similar dispersion and averages for males (n = 27, M = 37.89 years, SD = 11.84) and females (n = 13, M = 37.69, SD = 8.57). At the time of study participation, 55% (n = 22) were employed in some capacity (full-time or part-time), 45% (n = 18) lived independently or with a spouse or partner, and 67.5% (n = 27) drove independently. Most participants (n = 36, 90%) lived in urban areas, as classified by the Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx).

Table 1.

Demographics of the sample of autistic adults (n = 40)

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 37.89 years (10.77) |

| Range | 24–62 years |

| Male | 27 (67.5%) |

| Race | |

| White | 33 (82.5%) |

| Black/African American | 4 (10%) |

| Multiracial | 3 (7.5%) |

| Waisman activities of daily living scale scorea | |

| Mean (SD) | 30.75 (4.99) |

| Range | 10–34 |

| Highest level of education | |

| High School | 3 (7.5%) |

| Some college | 10 (25%) |

| Graduated 2-year college | 4 (10%) |

| Some vocational school | 3 (7.5%) |

| Graduated vocation school | 2 (5%) |

| Some 4-year college | 5 (12%) |

| Graduated 4-year college | 7 (17.5%) |

| Advanced degree | 6 (15%) |

| Employment status | |

| Never employed | 6 (15%) |

| Currently employed | 22 (55%) |

| Previously employed, currently unemployed | 11 (27.5%) |

| Living situation | |

| With parent, relative, caregiver, or guardian | 21 (52.5%) |

| Independent | 8 (20%) |

| With spouse or roommate | 10 (25%) |

| Group home | 1 (2.5%) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis (ever diagnosed) | |

| Anxiety | 18 (45%) |

| Depression | 20 (50%) |

| Other psychiatric diagnosis | 9 (22.5%) |

| Parent highest level of education | |

| High school | 3 (7.5%) |

| Graduated vocation school | 4 (10%) |

| Some college | 4 (10%) |

| Graduated 4-year college | 13 (32.5%) |

| Advanced degree | 16 (40%) |

aThe Waisman activities of daily living scale (Maenner et al. 2013) was administered in the context of the larger study to assess independence in completing daily living skills

Social Participation

Participants described social participation in a variety of contexts clustered around five main themes: (1) Vocational contexts, (2) Neighborhoods, (3) Common interest groups, (4) Support services and inclusive environments, and (5) Online networks and apps. A short description and example of each theme is included in Table 2. In all contexts, participants reported experiences that ranged across the spectrum of social participation that included casual encounters, engaging with known acquaintances, or engaging with close friendships or relationships. However, the results are purposefully structured by location and not level of engagement to show that social participation occurred at different levels in each context fostering a sense of belonging, which differed from person to person. Therefore, the goal was primarily to let the data tell the story, through the participants’ own words, and in response to specific interview questions. It is of note participants used some of these contexts to practice social interactions that they then applied to other settings or at other levels of engagement. Quotes were edited slightly for clarity and pseudonyms were assigned to each participant to protect confidentiality.

Table 2.

Overview of social participation themes

| Theme | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Vocational contexts | Employment, educational or volunteer experiences | “It’s work. It’s my practice ground. Social interaction practice.” |

| 2) Neighborhoods | Interaction with neighbors | “I guess I am part of a neighborhood community. I wouldn’t be if I didn’t walk the dog. But you meet a lot of people.” |

| 3) Common interest groups | Activities involving shared interests | “[Improv is] great for social skills. Oh my gosh, it’s so good for social skills.” |

| 4) Support services and inclusive environments | Disability support services | “I was diagnosed with autism at [autism organization]. And then they had an adult support group there, too, monthly and I would go there. Originally, I would go there by myself, and there would be a few other guys with autism that I got friendly with there too.” |

| 5) Online networks and apps | Internet-based platforms | “I think that’s [online communities] just as significant really. It’s still, you know, a community. It’s still a group of people that you share interests and ideas with.” |

Vocational Contexts

Some participants described vocational activities of employment, volunteering, and pursuing education as an avenue for social participation. Participants described work as a place to interact positively with others. For some it offered a sense of belonging, for others, it served as an important avenue for practicing social interactions. For example, Tyler reported his place of work was most important to him because, “It’s work. It’s my practice ground. Social interaction practice.” Similarly, Warren discussed how, prior to his diagnosis of autism, he worked as a grocery store clerk to practice interacting with others, stating,

So, for a while, I got a job, in order to put myself in a spot where I’d have to interact with more people. I got a job at a grocery store for about two months in addition to my other job. That was just so I could learn to interact better with people.

Another participant described the importance of his volunteer activities as an usher as a means to interact positively with others:

Well, I mean, when I usher, I interact with a lot of people. So, it's just getting—talking to people I don’t know. And I mean I have, um, people that are season ticket holders, so they come back every year. So, it’s nice just to see.

Additionally, one participant described his attendance at graduate school as offering a context to practice social skills and foster in-person social connection:

And so, once I went to grad school, I realized I’m far away from home…and I can’t just survive just being online anymore. I don’t ... have like my family for support—things like that. So, I literally just made like a concerted effort to study social skills by myself, as well as get as many experiences as possible to, uh, get to the point where I am today.

From these efforts, Brian developed a network of friends he remains in contact with, “I have like a group of friends from back in grad school I text with, all the time.”

Jack reported volunteering was among one of his favorite activities and commented on the importance of community built there, stating, "I like attending the different meetings for the groups, like the consumer family group for Lions. I just joined a group in a human rights committee at [psychiatric hospital]." Work also provided a sense of belonging and community for some participants. For example, when Bob was asked where he felt he belonged the most, he replied, “Work. It’s where I feel most confident.” When asked where he belonged the most, Joshua, who worked at a service organization for autistic individuals, stated, "Probably [autism organization], because I have been working there for—for a long time and I'm friends with pretty much everyone there.”

Even participants who did not work or participate in organizations directly serving those on the autism spectrum were able to find neurodiverse communities that offered social connection. For example, Brian participated in a neurodiversity group at his place of work and even created an international “autistic task force” within his business. He noted, “I'm active in the neurodiversity business resource group. So that’s been helpful.” Overall, employment, volunteer, and educational settings provided a means for shared common interests, interaction practice, and familiarity with others at different levels of social participation that increased feelings of belonging and connection to a group, and in some cases fostered meaningful social connections that endured.

Neighborhoods

Neighborhoods were identified as an environment promoting meaningful social engagement and personal security. Participants described visiting with friends and acquaintances within their local neighborhood communities as well as neighbors providing a sense of safety. For example, when asked where she usually saw her friends, Julia commented, “I think it's basically around the neighborhood and everything since we live like really close to each other and everything.” Daniel commented on how his neighbor promoted feelings of safety, stating, “There's a real involved next-door neighbor who would never let anything happen,” and indicated this security enabled him to be more independent.

Participants also specifically described pets as promoting social interaction within their neighborhood communities, and these interactions contributed to them feeling a part of the community. Travis stated, “I guess I am part of a neighborhood community. I wouldn’t be if I didn’t walk the dog. But you meet a lot of people.” Similarly, when asked if he felt part of his community, Nathan described how he spoke with neighbors while walking his cat in the neighborhood, stating, “I mean, I do get out occasionally. And if people see me with Cat, they’re pretty impressed and want to talk to me.”

Common Interest Groups

Activities involving a common interest offered opportunities for social engagement for many participants. For example, attending church fellowship provided a sense of belonging and place of connection to others through shared faith. Jack described his favorite activity in the community as “...going to church and being in the choir and things. I enjoy that.” Other participants felt a sense of belonging within their church, Bible studies, or faith-based communities. When asked where she felt she belonged the most, Hannah stated, “Oh, Kingdom Hall is the one that I belong [to] the most.” She described how her church community was accepting and provided a context for meaningful social engagement. Another participant, Kathryn, also described a Bible study and church as where she belonged the most.

Some participants described gaming as a common interest that increased social engagement. For example, Brian reported he participated in game nights frequently: “Playing cards—like I will be gone to board games multiple times a week regularly.” Nathan also described how he ran a Dungeons and Dragons clan, an interactive game, to connect with friends. Peter described his interaction with others through online gaming platforms but wished to play in person as well: “I’ve been dabbling in Pathfinder and Dungeons and Dragons on—with my Discord friends, but I’d like to be with an actual physical group one of these days.” Melissa participated in an improvisation group frequently and described how this allowed for important social skills practice, reporting, “[Improv is] great for social skills. Oh my gosh, it’s so good for social skills.” Common interest groups were used to interact with friends and acquaintances at times and were even used to practice interacting with others in a safe environment.

Support Services and Inclusive Environments

Some participants utilized formalized support services to create meaningful social relationships and also described specific service organizations as offering a sense of acceptance and safety. Specifically, autistic adult support groups were described as a means of providing social connection and comfort. For example, when asked where he felt most comfortable, Charles responded, “I’d probably say [my] support group.” Similarly, Joe noted,

I was diagnosed with autism at [autism organization]. And then they had an adult support group there too, monthly, and I would go there. Originally, I would go there by myself, and there would be a few other guys with autism that I got friendly with there too.

Similarly, two participants commented on the importance of a specific camp for individuals on the autism spectrum. Brian noted he met one of his closest friends at this camp and Joe commented he and his closest friend had attended the camp as a social activity together. Participants commented on how organizations specifically serving individuals with autism and developmental disabilities provided a sense of belonging and safety. Jerry commented,

You know, you come to [organization for individuals with developmental disabilities], you come to [another autism organization], this is like safe. Say what you want to. Do what you want to. You're not likely to go run into any problems [there].

These examples of connections attributed through supportive agencies and inclusive spaces were often described as leading to the development of friendships, where individuals met as strangers or acquaintances but developed closer relationships because they were able to be themselves without fearing judgment.

Although based on a professional relationship, therapists, support staff, and service animals were specifically described as important forms of social support as well. Danielle stated her biggest form of social support was a support staff who worked with her group home. Tyler described how his service dog increased his social motivation and ability to connect with others when he went out into the community. He stated: “I think this [service dog] really helped me. ‘Cause I was, you know, I was in a tough situation before I moved here. Just not much to do, not much motivation. She [my service dog] definitely helped with that.” The addition of extra support or encouragement to engage in social settings was important for initiating these contacts.

Online Networks and Apps: “That’s the way I communicate.”

Several participants commented on online social networks promoting social interaction in a variety of ways. One way in which online platforms were used was to facilitate in-person gatherings. Brian and Melissa indicated they had arranged dates using dating apps. Participants also described using or trying Meetup, an online platform designed for people who share similar interests to meet for events in person. Tyler, Brian, and Troy reported they used Meetup frequently to meet others for social activities in the community such as beer tastings, game nights and rock-climbing events. In fact, when asked about his biggest form of social support, Troy commented that he had used Meetup to connect with individuals at his rock-climbing gym and how Meetup provided a simple means of meeting new people. He stated, “Meetup’s a, you know, pretty good way to go out to do something without really, you don’t need too many social skills to at least sign up and get there, and I guess you’re on your own after that.”

Others described using a variety of online platforms for communication purposes. Joe stated, “Now I’m on Facebook groups a lot—autism AS groups communicating with people and I get to know people and it’s just, yeah, I’m really happy.” Hannah also reported, “I do, I do write on Facebook and stuff... That’s the way I communicate.” When asked where he usually saw his friends, Michael responded, “Online. I used to use Facebook but not anymore. Now, I use one called MeWe.” When asked the same question, Catherine responded, "Usually they're internet friends, so I just talk with them online." Brian noted, “And I also have a friend on Twitter I'm pretty close to.” Participants utilized many different social networking platforms to communicate with individuals, ranging from casual encounters, acquaintances, and close personal friends.

Beyond individual relationships, a few participants discussed using social networking platforms to establish important online communities. When asked if she felt part of her community, Catherine stated, “Yeah, the online one, definitely. I can—we have discussion, and—it feels like I'm involved, and my opinions are taken. Like, they—they hear my opinions.” Similarly, Isaac described his view of online communities being of the same importance as typical communities: “I think that’s just as significant really. It’s still, you know, a community. It’s still a group of people that you share interests and ideas with.” Brian, who moved to a new town approximately one year prior, reported he used online platforms to connect with friends in other areas while waiting to build a community closer to home, “I’ve been able to get a good—good network of people—to some extent. They’re mostly online, now, ‘cause I haven’t made full close friends down here.” For some participants, social interactions online led to feelings of belonging and community, and at times prompted the building of connections across the social spectrum, from stranger, to someone familiar, to a supportive community.

Discussion

The current study is consistent with findings in prior qualitative studies where many, but not all, autistic adults desire social connections (Causton-Theoharis et al., 2009; Muller et al., 2008). In the present study, autistic adults were engaging in a range of social participation experiences in a variety of contexts. Moreover, these autistic adults were using different venues to intentionally practice social skills, including in-person engagement and online connections. Reports of casual encounters with neighbors or acquaintances were meaningful and contributed to individuals feeling part of their communities. With a significant focus in the literature on loneliness, isolation, and friendship quality in autistic adults, the current study provides some initial support to think more broadly about the context of where social participation and interactions take place and the meaning ascribed. These findings may provide more context to past research by Mehling and Tasse (2014), who found that individuals with and without autism were participating in the community at similar rates but those with autism reported lower levels of friendship, implying these community interactions were not leading to increased friendships for autistic adults. In conjunction with the current findings, it is possible that autistic adults are socially participating and active in their communities, but it may not extend to the level of a close friendship. Autistic adults may still need some support in finding or developing these closer connections in the community, if desired.

The role and use of video games, online connections, and social media by autistic individuals has received increased attention in the literature, particularly related to social participation and friendship (Mazurek et al., 2013, Milton & Sims, 2016; Schalkwyk et al., 2017; Sundberg, 2018). In childhood, Mazurek and Wenstrup (2013) found time spent playing video games was associated with less time socially interacting or using social media in autistic children compared to their neurotypical peers. In adolescence and adulthood, online connections, social media use, and playing online video games with others has previously been associated with higher friendship quality, more friends, and less loneliness (Kuo et al., 2013; Milton & Sims, 2016; Schalkwyk et al., 2017; Sundberg, 2018). While online connections are often perceived as less meaningful in the neurotypical view of social participation, Mazurek’s (2013) study examining social interactions and friendships reported almost half of the autistic adults in the study used electronic communication to contact close friends through email, text, chat or social media at least once a day or several times a day, whereas in-person visits or phone contacts were more likely to occur on a monthly basis. The current study contributes to the literature supporting the meaning and feelings of belonging attributed to these electronic connections, and new evidence of the progression of independently using technology to meet others in person through using Meetup groups and online dating apps. Participants in the current study did not exclusively use technology for social connections but merged the use of technology and online platforms to engage in in-person connections in the community.

The current study found evidence for the importance of connecting with other individuals on the spectrum in adulthood, whether through in-person support groups with other autistic adults, close personal friendships, seeking online communities specifically for autistic adults, or creating an autistic task force at work to support coworkers who are also on the spectrum. Past research notes autistic adults are more likely to disclose more about themselves to other autistic adults and prefer to interact with others on the spectrum, where they can speak freely about their interest (Milton & Sims, 2016; Morrison, 2020). As noted by Milton and Sims (2016), relationships with others who identify as autistic are very important, especially in fostering feelings of acceptance and safety. Consistent with our findings, online forums provide a space for these relationships. However, in-person connections at work or through autism support agencies were also identified as meaningful places of social connection with other autistic adults. It is of note that the importance of connecting with other autistic adults may represent a shift from childhood, where autistic children show a preference for interacting with neurotypical peers in a classroom setting (Bauminger et al., 2003). In adulthood, the current study provides preliminary support for a broader range of social participation with both autistic and neurotypical individuals.

There is also specific support for Elmose’s (2020) notion of “accessibility” as an important factor facilitating social relationships in autistic adults, where partners, spouses, school, or work helped build connections and ease interactions. For some of the current participants, shared interests in games nights, faith communities, work, volunteer, or educational settings provided important contexts encouraging connections of convenience and interaction with others. Different types of roles, such as partner, employee/volunteer, neighbor, or group member, in different contexts led to accessibility for opportunities for social participation.

Participants in the current study reported feeling safe at organizations for individuals with autism and developmental disabilities and connecting with others through online autism groups. Participants also reported using work or volunteer positions as a safe space to intentionally practice social skills with others. This connects to Elmose’s (2020) findings that autistic adults actively decode the social rules of situations or interactions with people based on past experiences, and plan ways to make social interaction easier. However, unlike some of the participants in Elmose’s (2020) study who reported seeking out activities such as going to the movies, sporting events, or concerts where there was less social interaction or the social interaction would be more predictable, the current study noted examples of participants actively seeking out social interactions, through work, volunteer positions, or joining an improvisation class, that were less predictable to practice and improve their social skills.

Finally, it is of note in the autism literature on isolation and loneliness that more attention has been given to the importance of perceived loneliness and the subjective experience of social interaction in determining the impact on well-being (Mazurek, 2014; McConachie et al., 2020). Not everyone in the current study preferred to engage in social interactions, as clearly stated by one participant who commented, “I don’t like people.” Additionally, there were several participants who responded, “I have no friends,” when asked where they typically see their friends. However, a number of participants perceived themselves as being engaged in meaningful social interactions in a variety of contexts and at various levels of social participation that contributed to feelings of belonging that may or may not require having a close friend in adulthood. This finding provides preliminary support for the formation of a sense of community and feelings of belonging. Even those who desired more social connection reported other community connections, in-person or online, with individuals at the casual encounter or acquaintance level that helped them feel connected to their sense of community.

Limitations

While the purpose of the larger study was to describe the community participation experiences of autistic adults, including social participation, data collection was not created around exploring different levels of social engagement, or differences in the quality of friendships found in different contexts, such as in person or online connections. We attempted not to impose our own lens in interpreting the findings and ascribe meanings to the range of social connections described, but rather sought to let the data speak for itself. When asked where participants saw their friends, we assumed their responses included descriptions of meaningful friendships, and at times, this question elicited direct statements of not having friends. Elsewhere, participants openly described the lack of close friendships, or acknowledged that contacts remained at an acquaintance level. However, often participants described social contacts at all levels in relation to identifying places where they felt they belonged, places that were most important to them, and as contributing to feeling part of the community.

Similarly, the current study did not begin from a neurodiversity framework to specifically focus on strengths of individuals in the context of social participation. However, when participants described different means of social engagement that seemed to be working in connecting with others for significant friendships, dating, or marriage partners, we often prompted them to share more in hopes of understanding the different contexts and/or supports that were helpful in facilitating these meaningful connections. Additional study limitations include a small sample from a limited geographic region. Furthermore, inclusion criteria of an IQ of 70 or above means the entire autism spectrum is not represented in our findings. Additionally, most data were collected before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some (n = 11) were collected via Zoom interviews during the pandemic, which expanded our geographic reach but also required that participants have access to reliable internet connection, thus excluding some participants. Participants in the current study indicated if they were ever diagnosed with a mental health condition on a demographic survey. However, we did not collect information regarding current psychiatric diagnoses, which may have impacted social participation unless it was shared directly during the interview. For example, Kayla noted, “I have really bad social anxiety at times...especially for places that are unfamiliar.” Finally, we did not collect any information regarding prior participation in social skill interventions, which may have promoted social engagement.

Implications for Practice

In addition to social skills training groups, our findings suggest the need for structured opportunities for social interactions and individualized approaches to promote social participation in areas of interest. This may be part of providing comprehensive supports for autistic adults through an interdisciplinary approach including professionals such as rehabilitation counselors, recreational, and occupational therapists. While social skills training can be an effective intervention, providing structured opportunities, such as practicing social interaction in community contexts with professional support, could be another step in promoting social participation in autistic adults. Offering information about online platforms that can be used to facilitate in-person social interaction may be an avenue for fostering new social connections. Additionally, encouraging participation in natural practice spaces for social interaction at work and in common interest groups may offer potential means for social interaction. Because adults with autism may desire spaces in which they can discuss their interests (Milton & Sims, 2016), these natural practice grounds, especially when related to common interest, may allow adults with autism to engage with others in a way that they prefer. For example, if an individual has an interest in gaming, participating in a gaming group would allow the individual to speak freely about their interest while engaging with others.

While encouraging the use of online platforms to facilitate in-person interaction and participation in common interest groups may be potential avenues for meaningful social connection, formalized support services also offered safe spaces for our participants to engage with others with developmental disabilities, and potentially develop closer relationships. Taken a step further, support groups could offer opportunities to organize social outings or discuss ways to meet new people. Additionally, individual therapy sessions could be utilized to practice social skills and discuss contexts in which these skills could be practiced. For example, clinicians could collaborate with clients to identify where they might practice social interactions in various contexts in the community including volunteer sites, the grocery store, or in the neighborhood, with or without a pet. Therapists could challenge clients to think about how they might interact with individuals in these locations. Additionally, therapists could assist clients to plan when the social outing would occur, how to self-manage their capacity for social interaction in the community, and create an exit strategy if the activity becomes overwhelming or overstimulating.

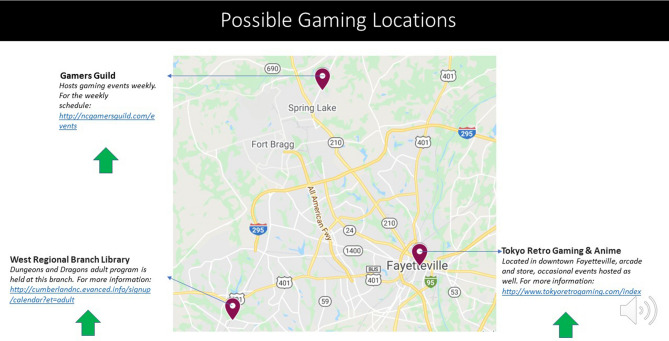

To increase community and social engagement, our research team created “personalized mapping profiles” for each participant, depicted in Figure 1. These profiles included locations visited during the study week, other important locations they noted that were not visited during the study week, approximately 10 new locations the participant could visit based on identified interests during the study interviews, and information about Meetup with approximately three suggested Meetup groups. A description of each new location, a color-coded map with its location relative to the participant’s home, and the website link was included in each profile. Creating similar mapping profiles could provide a visual representation of new locations of interest in community and provide new ideas for potential contexts for social interaction.

Fig. 1.

An example slide from the personalized mapping profiles developed for participants

Participants in the current study highlighted how they had both practiced social skills and found meaningful social connections in the workplace. Employment supports independence in the community and could potentially have the added benefit of developing social connection for autistic adults. Providing employment support to this population may have the benefit of fostering natural supports and providing a safe context for social practice. Referrals to vocational rehabilitation agencies or to support agencies with expertise in supported employment for autistic adults may increase employment attainment and social participation.

Future Directions

Although social networking promoted social engagement in many cases, participants also described having the majority of one’s friends out of town or online as a barrier to social interaction. Peter explained, “I haven’t spoken with most of my non-online friends in ages.... most of the friends I do have online are either somewhere across the ocean, somewhere on the other side of the country.” Similarly, Michael indicated he would like to attend parties and go to bars with friends but was not presently participating in those activities. When asked about barriers to these activities, he explained, “A lot of my friends are out of town,” and later described most of his friends were online. Because research has shown social connection is important to healthy aging (Michael et al., 1999; Uchino et al., 2001), it is worth noting that some participants described their social interactions as primarily online. Although beyond the scope of our research, understanding whether online friendships and interactions support healthy aging and well-being in autistic adults may be beneficial, and more research is needed in this area. Future research would benefit from a more comprehensive investigation into the quality, frequency, and meaning connected to online versus in-person social interactions and friendships, and important mechanisms supporting the development of these social connections. Because the connection between loneliness and an unmet need to belong is associated with suicidal ideation in autistic adults (Camm-Crosbie et al., 2019; Dow et al., 2021; Pelton et al., 2020), a specific focus on the impact of online and in-person social connections on mental health is needed.

While many participants reported no barriers to participation during the study week, some participants noted additional barriers of transportation, expense, and weather, as well as lack of motivation, energy, or people to do things with as interfering with social participation. At times, as Renee noted, it was a combination of factors,

Like if I had, if I had more friends like I would probably do more; [if] people were asking me, ‘Hey you wanna go do blah blah blah?’ I probably would. But I don’t really have any like, real friends right now. And I get exhausted from having to work.

Mental health, sensory, and organizational challenges were also reported as barriers to planned or desired activities during the study week. More research is needed to further examine how different types of barriers can be addressed to support a full range of social participation in autistic adults.

Conclusion

The current study suggests considerations of well-being and feelings of belonging in autistic adults should not be limited to measures of the number and quality of friendships alone. Rather, as researchers and clinicians, we may need to change the questions we are asking regarding the range of types of connections with others and community contexts that collectively contribute to social participation. As autistic adults navigate social experiences, the current study found evidence of individuals using a variety of in-person and online community contexts to intentionally practice and improve their social participation skills. In addition, current findings support autistic adults used specific apps to facilitate in-person meet ups, at times merging the preference for online communication with the desire for in-person connection. These results suggest exploring new ways to tailor interventions to support the range of desired social participation preferences of autistic adults. These findings may be a first step in research on the role of the range of social connections and healthy aging or well-being in autistic adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Laura Klinger, Ph.D. and The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill TEACCH Autism Program’s research team for their feedback on an early draft of this manuscript. This paper was presented at the 20th annual National Council on Rehabilitation Education Conference (NCRE), July 17, 2020. This study was made possible through funding from The National Institute of Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (#90SFGE0008-01-00). Assistance for this project was also provided by the UNC Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (NICHD; P50 HD103573; PI: Joseph Piven). The data management aspects of the project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Contributions

Dara Chan contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by all authors. Dara Chan and Julie Doran completed the data analysis and contributed to the manuscript writing. Osly Galobardi aided in data collection, analysis and interpreting the results. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dara Chan and Julie Doran. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Dara Chan has received primary support for this project from a Switzer Fellowship from The National Institute of Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (#90SFGE0008-01-00). Assistance for this project was also provided by the UNC Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (NICHD; P50 HD103573; PI: Joseph Piven). The project described was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Achat H, Kawachi I, Levine S, Berkey C, Coackley E, Colditz G. Social networks, stress and health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 1998;7(8):735–750. doi: 10.1023/A:1008837002431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ashida S. Differential associations of social support and social connectedness with structural features of social networks and the health status of older adults. Journal of Aging and Health. 2008;20(7):872–893. doi: 10.1177/0898264308324626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill J. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12(6):855–866. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatell N. From cure to community: Transforming notions of autism. Journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology. 2010;38(1):33–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1352.2009.01080.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S. Editorial Perspective: Neurodiversity—a revolutionary concept for autism and psychiatry. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2017;58(6):744–747. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Shulman C, Agam G. Peer interaction and loneliness in high-functioning children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33(5):489–507. doi: 10.1023/a:1025827427901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Solomon M, Aviezer A, Heung K, Gazit L, Brown J, Rogers SJ. Children with autism and their friends: A multidimensional study of friendship in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(2):135–150. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlow C, Rosqvist H, O’Dell L. Exploring the potential for social networking among people with autism: challenging dominant ideas of ‘friendship’. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research. 2015;17(2):188–193. doi: 10.1080/15017419.2013.859174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calder L, Hill V, Pellicano E. ‘Sometimes I want to play by myself’: Understanding what friendship means to children with autism in mainstream primary schools. Autism. 2012;17(3):296–316. doi: 10.1177/1362361312467866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camm-Crosbie L, Bradley L, Shaw R, Baron-Cohen S, Cassidy S. ‘People like me don’t get support’: Autistic adults’ experiences of support and treatment for mental health difficulties, self-injury and suicidality. Autism. 2019;23(6):1431–1441. doi: 10.1177/1362361318816053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causton-Theoharis J, Ashby C, Cosier M. Islands of loneliness: Exploring social interaction through the autobiographies of individuals with autism. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;47(2):84–96. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-47.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Data & statistics on autism spectrum disorder. Retrieved April 3, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

- Dow D, Morgan L, Hooker J, Michaels M, Joiner T, Woods J, Wetherby A. Anxiety, depression, and the interpersonal theory of suicide in a community sample of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Suicide Research. 2021;25(2):297–314. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1678537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmose M. Understanding loneliness and social relationships in autism: The reflections of autistic adults. Nordic Psychology. 2020;72(1):3–22. doi: 10.1080/19012276.2019.1625068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SFN, Kasari C. Friendships in children with developmental disabilities. Early Education & Development. 1998;9(4):341–355. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed0904_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Marvin A, Lounds Taylor J, Warren Z, Anderson C, Law P, Law J, Lipkin P. Characterizing the daily life, needs, and priorities of adults with autism spectrum disorder from interactive autism network data. Autism. 2015;19(7):794–804. doi: 10.1177/1362361315583818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A, Maietta R. Rapid turn around qualitative research. Research Talk, Inc.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henniger NA, Taylor JL. Outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: A historical perspective. Autism. 2012;17(1):103–116. doi: 10.1177/1362361312441266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick, S., Datti, P. (2020). Neuro-competence: A multicultural counseling competence model for autism spectrum disorder. The 20th annual National Council on Rehabilitation Education Conference, Online

- Howlin P, Taylor JL. Addressing the need for high quality research in autism in adulthood. Autism. 2015;19(7):771–773. doi: 10.1177/1362361315595582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y, Foley K, Troller J. Aging well on the autism spectrum: the perspectives of autistic adults and carers. International Psychogeriatrics. 2017;29(12):2033–2046. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Locke J, Gulsrud A, Rotheram-Fuller E. Social networks and friendships at school: Comparing children with and without ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41(5):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M, Duff H, Kelly S, McHugh Power J, Brennan S, Lawlor B, Loughrey D. The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby A, Baranek G, Fox L. Longitudinal predictors of outcomes for adults with autism spectrum disorder: Systematic review. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2016;36(2):55–64. doi: 10.1177/1539449216650182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M, Orsmond G, Cohn E, Coster W. Friendship characteristics and activity patterns of adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2013;17(4):481–500. doi: 10.1177/1362361311416380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam G, Holden E, Fitzpatrick M, Raffaele Mendez L, Berman K. “Different but connected”: Participatory action research using photovoice to explore well-being in autistic young adults. Autism. 2020;24(5):1246–1259. doi: 10.1177/1362361319898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A, Perry A. Outcomes in adolescents and adults with autism: A review of the literature. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(4):1271–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Locke J, Ishijima E, Kasari C, London N. Loneliness, friendship quality and the social networks of adolescents with high-functioning autism in an inclusive school setting. Journal of Research in Special Education Needs. 2010;10(2):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01148.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ, Smith LE, Hong J, Makuch R, Greenberg JS, Malick MR. Evaluation of an activities of daily living scale for adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal. 2013;6(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek M. Social media use among adults with autism spectrum disorders. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(4):1709–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek M. Loneliness, friendship, and well-being in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2014;18(3):223–232. doi: 10.1177/1362361312474121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek M, Wenstrup C. Television, video game and social media use among children with ASD and typically developing siblings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(6):1258–1271. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1659-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum M, LaVesser P, Berg C. Participation in daily activities of young adults with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(3):987–997. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2642-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConachie H, Wilson C, Mason D, Garland D, Parr J, Rattazzi A, Rodgers J, Skevington S, Uljarevic M, Magiati I. What is important in measuring quality of life? Reflections by autistic adults in four countries. Autism in Adulthood. 2020;2(1):4–12. doi: 10.1089/aut.2019.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehling M, Tasse M. Empirically derived model of social outcomes and predictors for adults with ASD. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2014;52(4):282–295. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael Y, Colditz G, Coakley E, Kawachi I. Health behaviors, social networks, and healthy aging: Cross-sectional evidence from the Nurses’ Health Study. Quality of Life Research. 1999;8(8):711–722. doi: 10.1023/a:1008949428041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton D, Sims T. How is a sense of well-being and belonging constructed in the accounts of autistic adults? Disability & Society. 2016;31(4):520–534. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2016.1186529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison K, DeBrabander K, Jones D, Faso D, Ackerman R, Sasson N. Outcomes of real world social interaction for autistic adults paired with autistic compared to typically developing partners. Autism. 2020;24(5):1067–1080. doi: 10.1177/1362361319892701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller E, Schuler A, Yates G. Social challenges and supports from the perspective of individuals with Asperger syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. Autism. 2008;12(2):173–190. doi: 10.1177/1362361307086664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers E, Davis BE, Stobbe G, Bjornson K. Community and social participation among individuals with autism spectrum disorder transitioning to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(8):2373–2381. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2403-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond G, Shattuck P, Cooper B, Sterzing P, Anderson K. Social participation among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(11):2710–2719. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1833-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond G, Wyngaarden Krauss M, Mailick Seltzer M. Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34(3):245–256. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000029547.96610.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J, Asher S. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(4):611–621. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelton M, Crawford H, Robetson A, Rodgers J, Baron-Cohen S, Cassidy S. Understanding suicide risk in autistic adults: Comparing the interpersonal theory of suicide in autistic and non-autistic samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020;50(10):3620–3637. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, Perlman D. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Petrina N, Carter M, Stephenson J, Sweller N. Friendship satisfaction in children with autism spectrum disorder and nominated friends. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47(2):384–392. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2970-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Fuller E, Kasari C, Chamberlain B, Locke J. Social involvement of children with autism spectrum disorders in elementary school classrooms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux A, Shattuck P, Cooper B, Anderson K, Wagner M, Narendorf S. Postsecondary employment experiences among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(9):931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley E, Chandler S, Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Loucas T, Charman T. The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2012;6(3):1126–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schalkwyk G, Marin C, Ortiz M, Rolison M, Qayyum Z, McPartland J, Lebowitz E, Volkmar F, Silverman W. Social media use, friendship quality, and the moderating role of anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47(9):2805–2813. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick F, Leppanen J, Tchanturia K. The friendship questionnaire, autism, and gender differences: A study revisited. Molecular Autism. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0295-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen HC, Mohr Jensen C, Lauritsen MB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the long-term overall outcome of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2016;133(6):445–452. doi: 10.1111/acps.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M. Online gaming, loneliness and friendships among adolescents and adults with ASD. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;79:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tint A, Maughan AL, Weiss JA. Community participation of youth with intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2016;61(2):168–180. doi: 10.1111/jir.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin M, Drager K, Richardson L. A systematic review of social participation for adults with autism spectrum disorders: Support, social functioning, and quality of life. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014;8(3):214–229. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B, Holt-Lunstad J, Uno D, Flinders J. Heterogeneity in the social networks of young and older adults: Prediction of mental health and cardiovascular reactivity during acute stress. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;24(4):361–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1010634902498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YI, Solomon PL. Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities in supportive independent housing: A conceptual model and methodological considerations. Mental Health Services Research. 2002;4(1):13–28. doi: 10.1023/A:1014093008857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood L, Martin K, Christian H, Nathan A, Lauritsen C, Houghton S, Kawachi I, McCune S. The pet factor–companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation and social support. PloS one. 2015;10(4):e0122085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]