Abstract

Background:

Lithium, one of the few effective treatments for bipolar depression (BPD), has been hypothesized to work by enhancing serotonergic transmission. Despite preclinical evidence, it is unknown whether lithium acts via the serotonergic system. Here we examined the potential of serotonin transporter (5-HTT) or serotonin 1A receptor (5-HT1A) pre-treatment binding to predict lithium treatment response and remission. We hypothesized that lower pretreatment 5-HTT and higher pretreatment 5-HT1A binding would predict better clinical response. Additional analyses investigated group differences between BPD and healthy controls and the relationship between change in binding pre- to post-treatment and clinical response. 27 medication-free patients with BPD currently in a depressive episode received positron emission tomography (PET) scans using 5-HTT tracer [11C]DASB, a subset also received a PET scan using 5-HT1A tracer [11C]-CUMI-101 before and after eight weeks of lithium monotherapy. Metabolite-corrected arterial input functions were used to estimate binding potential, proportional to receptor availability. 14 patients with BPD with both [11C]DASB and [11C]-CUMI-101 pre-treatment scans and eight weeks of post treatment clinical scores were included in the prediction analysis examining the potential of either pre-treatment 5-HTT or 5-HT1A or the combination of both to predict post-treatment clinical scores.

Results:

We found lower pre-treatment 5-HTT binding (p=0.003) and lower 5-HT1A binding (p=0.035) were both significantly associated with improved clinical response. Pre-treatment 5-HTT predicted remission with 71% accuracy (77% specificity, 60% sensitivity), while 5-HT1A binding was able to predict remission with 85% accuracy (87% sensitivity, 80% specificity). The combined prediction analysis using both 5-HTT and 5-HT1A was able to predict remission with 84.6% accuracy (87.5% specificity, 60% sensitivity). Additional analyses BPD and controls pre- or post-treatment, and the change in binding were not significant and unrelated to treatment response (p>0.05).

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that while lithium may not act directly via 5-HTT or 5-HT1A to ameliorate depressive symptoms, pre-treatment binding may be a potential biomarker for successful treatment of BPD with lithium.

Clinical Trial Registration:

PET and MRI Brain Imaging of Bipolar Disorder Identifier: NCT01880957; URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01880957

Keywords: Bipolar Depression, Lithium, Prediction, PET, Serotonin Transporter, Serotonin-1A

Background:

Bipolar disorder, the 6th leading cause of disease burden worldwide, is a debilitating psychiatric condition characterized by periods of mania and depression. Bipolar depression (BPD), which clinically resembles major depression, poses a high risk for suicide. Two major obstacles in the treatment of BPD are our lack of understanding of its underlying neurocircuity, and the mechanism of action for existing treatments.

Lithium remains one of the first lines of therapy for treating both mania and depression in bipolar disorder(1). Lithium is used for long-term, prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder to prevent further occurrence of both mania and depression(2). A meta-analysis of five controlled trials found that lithium was 20% more effective in preventing recurrence of bipolar disorder than placebo(3). Interestingly, it has also proven extremely effective in reducing suicide attempts and mortality(4, 5). While many find near total resolution of symptoms following lithium treatment, more than 25% of patients show no clinical response(3). What is needed is a better understanding of lithium’s mood stabilizing mechanisms to identify a potential biomarker for successful treatment response.

Little is known about the cellular mechanisms underlying lithium’s effects on mood. A leading hypothesis is that lithium works by enhancing serotonergic transmission(6, 7). Previous studies have provided evidence for lithium’s effects on serotonergic synthesis(8), uptake(6, 7), receptor interactions(9), and perhaps most importantly serotonin (5-HT) release(10). Considering the serotonergic system is the site of action of some of the most successful antidepressants (serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs), it is plausible that lithium too works in concert with or directly upon the serotonergic system to exert its anti-depressant effects. Of interest is lithium’s effect on 5-HT uptake at the serotonin transporter (5-HTT). 5-HTT is the protein responsible for the termination of 5-HT in the synapse, and the target of SSRIs. Preclinical studies reveal increases in 5-HTT density (Bmax) in cortical regions following chronic lithium treatment(7), but not in subcortical regions known to be altered in BPD and major depression, including midbrain and amygdala(11, 12). Additionally, it has been suggested that a functional polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene increases the susceptibility to bipolar disorder(13), and can modulate lithium’s effectiveness as a mood stabilizer(14).

Of equal interest is the serotonin 1A receptor (5-HT1A) of which there are two types: 1) autoreceptors which reside in the raphe nucleus upon serotonergic cell bodies and dendrites, and 2) post-synaptic receptors which exist within terminal fields throughout the brain(15). SSRIs are thought to contribute to the desensitization of raphe 5-HT1A autoreceptors, thereby increasing 5-HT in the synapse, and eventually leading to changes in post-synaptic 5-HT1A, and an efficacious response. It is plausible, then, that lithium also affects 5-HT1A either pre- or post-synaptically to mediate treatment response. Indeed, preclinical studies reveal decreases in post-synaptic 5-HT1A the frontal cortex and hippocampus following lithium monotherapy(16, 17), while raphe 5-HT1A levels remain unchanged(17).

Neuroimaging is a promising tool for in vivo investigation of serotonergic proteins and their relationship with treatment response in BPD. Using Positron Emission Tomography (PET), our group has found higher 5-HT1A binding was associated with improved clinical response in BPD following 3 months of treatment with SSRIs (18). Further, we have found that that decreased 5-HTT binding in the amygdala was predictive of future remission in MDD (19), and that suicide attempters had lower midbrain 5-HTT binding as compared to nonattempters and controls(11). Here we examine the potential of pre-treatment 5-HTT (assessed with carbon 11–labeled 3-amino-4-(2-dimethylaminomethyl-phenylsulfanyl)- benzonitrile ([11C]DASB)) or 5-HT1A (assessed with partial agonist tracer carbon 11-labeled [O-methyl-(11)C]2-(4-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)butyl)-4-methyl-1,2,4-triazine-3,5(2H,4H)dione ([11C]-CUMI101)) binding to predict treatment response following eight weeks of standardized lithium monotherapy. We use cross-validated LASSO regression for robust estimation of brain regions with 5-HTT and 5-HT1A binding that predict treatment response and classify the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of these predictions.

As per the proposed aims of the NIH Grant: R01MH090276 our goals were to investigate the potential of 5-HTT or 5-HT1A binding to predict treatment response following 8 weeks of lithium treatment. Additional grant aims sought to determine pre-treatment differences in 5-HTT or 5-HT1A binding between groups and assess whether change in binding pre-to-post treatment related to clinical response. We predicted pretreatment 5-HTT and 5-HT1A binding would be predictive of clinical response following lithium treatment. We theorized that lithium would alleviate depressive symptoms by exerting its effects in the synapse, by increasing 5-HT release, leading to homeostatic upregulation of cortical (anterior cingulate cortex) but not subcortical (midbrain and amygdala) 5-HTT, and downregulation of post-synaptic 5-HT1A but not in the somatodendritic raphe region. We hypothesized that these lithium-induced alterations would associate with better clinical response.

Methods:

Subjects/Treatment

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC), Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), Yale University Medical Center (Yale), and Stony Brook University (SBU). All participants provided written, informed consent. Recruitment occurred from March 2008 through June 2017.

BPD group: 27 adults met DSM-IV criteria for bipolar depression, (assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I)(20) and psychiatrist interview). All subjects were medication-free for a minimum of 3 weeks prior to treatment initiation; approximately 30% of the sample was medication naïve upon enrollment. Exclusion criteria for patients with BPD were: 1. other major psychiatric disorders (not including eating disorders or phobias), 2. substance abuse for the past two months, 3. recent dependence within the past six months (except cannabis use disorders), 4. IV drug use in the past five years, 5. MDMA use more than 15 times in the past 10 years or any use in the past month(21), 6. satisfactory response to psychiatric medications or lack of response to a trial of adequate dose/duration of lithium, 7. active suicidality, 8. electroconvulsive therapy within the past six months, 9. pregnancy, currently lactating, planning to conceive during the course of the study, or abortion in the past two months, 10. significant physical illness, 11. neurological disease/prolonged loss of consciousness, 12. any magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contraindications, 13. medicinal patch that cannot be removed, and 14. lacking capacity to consent. Inclusion criteria for patients with BPD were: 1. a score of ≥15 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17; inclusion only)(22), 2. the ability to stop all drugs that would likely interact with the serotonergic system for three weeks prior to scanning, and 3. being between 18 and 70 years of age.

In addition to patients with BPD, 28 healthy adult volunteers (HV) were enrolled. Primary inclusion criteria for HV were no lifetime history of Axis I disorders (other than specific phobias or adjustment disorder) and being between 18 and 70 years of age. Additional exclusion criteria not overlapping with patients with BPD include: having a first-degree relative with a history of major depression (if participant was < 44 years old), history of suicide attempt, and two or more first degree relatives with a history of substance dependence (if participant was < 27 years old).

Clinical Procedures

Following baseline PET and MRI scans and assessment with the HDRS-24-item (HDRS-24), treatment was initiated with lithium monotherapy as previously described(23). In brief: days 1–3: 300mg 2x/day, days 4–7: 300mg every morning and 600mg every night; titration to a therapeutic plasma level of 0.8–1.2 mEq/l. Following eight weeks of treatment, patients were rescanned with PET and MRI and reassessed with the HDRS-24.

PET Scanning Protocol

Preparation and scanning of [11C]DASB (24) [11C]-CUMI-101(25) was performed as previously described. In brief, PET images were acquired on an ECAT EXACT HR+ scanner (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, Tennessee) at either CUMC, BNL or Yale. Following a 10-minute transmission scan, [11C]-CUMI-101 was injected as an intravenous bolus and emission data was collected for 120 minutes after which time subjects exited the scanner for a short break (approximately two hours, six additional [11C] half-lives, approximately twelve half-lives in total). Following a short break, a 10 minute transmission scan was collected and [11C]-DASB was injected as an intravenous bolus; emission data was collected for 100 minutes.

Image Processing

[11C]DASB(11, 26) and [11C]-CUMI-101(25) image analysis was performed as previously described. In brief, frame-wise rigid body registration to a reference frame was performed to correct the PET data for motion using the FMRIB linear image registration tool (FLIRT). We check this motion correction algorithm using movies that compare the original PET frames to the motion corrected PET frames. The mean motion-corrected frame was then co-registered to the MRI. Finally, probabilistic regions of interest (ROIs) were generated for each subject and applied to the PET data.

Quantitative Analysis

Automated arterial blood sampling was performed for the first 7 minutes of the PET acquisition, followed by manual arterial sampling thereafter. A metabolite-corrected input function was generated from the full sampling arterial data (linear fit to the peak and a sum of three exponentials thereafter) or a validated simultaneous estimation algorithm was used to compute the metabolite-corrected arterial input function using a single venous or arterial blood sample(23, 27). Time activity curves were fit with likelihood estimation in graphical analysis (LEGA) as previously described(28) to obtain estimates of optimal binding potential measures: VT/fP (VT= total distribution volume, fP = tracer plasma free fraction) for [11C]-DASB(29) and BPf (Bavail/Kd, where Bavail is receptor availability and 1/Kd is the affinity) for [11C]-CUMI-101(25). Standard errors (SE), which assess the goodness-of-fit of the binding data, were computed using an in-house implementation of bootstrapping via resampled residuals from the fit PET brain data, as previously described(30), The SEs were used to weight the subsequent linear mixed effects models. That is, the higher the confidence in the fit, the lower the SE, and the more heavily the data point is weighted.

Statistical Analysis

T-tests were used to examine demographic characteristics. Binding outcomes were log-transformed to stabilize region-wise variance and to fulfill normality assumptions of subsequent models, as previously described(11). For 5-HTT binding data, a model was fit for the a priori regions of interest: midbrain, amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex. For 5-HT1A binding data, separate models were fit for: 1. the a priori somatodendritic region (raphe nucleus) and 2. the a priori post-synaptic regions (12 previously validated ROIs: anterior cingulate, amygdala, cingulate, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, insula, medial prefrontal cortex, occipital cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, parietal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, and temporal cortex)(31). All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 3.3.3 (http://www.R-project.org).

Prediction of Treatment Response

To investigate whether pre-treatment binding predicted treatment response, a model was fit with the subject-wise pre-treatment aggregate score of 5-HTT binding in the 3 a priori regions and pre-treatment HDRS-24 as fixed effects. Post-treatment HDRS-24 was the model outcome and subject was fit as a random effect. The model was repeated with each of the three a priori ROIs in separate models as well.

To investigate whether pre-treatment 5-HT1A binding predicted treatment response, separate models were fit with (1) pre-treatment a priori raphe nucleus 5-HT1A binding as a fixed effect, and (2) a subject-wise pre-treatment aggregate score of 5-HT1A binding in the 12 a priori post-synaptic regions (together) as a fixed effect. In addition to the subject-level aggregate score for pre-treatment 5-HT1A binding, each of the post-synaptic a priori ROIs were fit in separate models to see if specific regions were driving the results.

All models were also repeated using the dichotomous remission status variable (remitter vs. non-remitter, where remitter is defined a priori by HDRS-24 <10 post-treatment and a reduction of greater than or equal to 50% in HDRS-24 pre-to-post treatment(26)) to determine if pre-treatment binding predicted those who would remit following 8 weeks of lithium treatment.

Next, LASSO linear regression (Glmnet package (ORIGINAL CITE); R Core Team, 2016. Vienna, Austria; ORIGINAL LINK) was used to predict the continuous post-treatment HDRS-24 scores with the independent variables: HDRS-24 pre-treatment score and binding data in each of the a priori regions (amy, acn, mid for 5-HTT and the raphe, as well as the 12 post-synaptic regions, for 5-HT1A). LASSO regression is a method that uses penalized maximum likelihood estimation to fit generalized linear models(32) and is commonly used in psychiatric research(33–35). LASSO regression is particularly beneficial when a dataset contains multiple, potentially inter-correlated predictors, which is common with brain imaging data, because the approach enforces model sparsity by selecting the most relevant predictors and shrinking the other coefficients to zero5. The tuning parameter lambda within the LASSO regression framework was selected via 10 repetitions of 5-fold cross-validation(36). The final models retained all variables with coefficients greater than zero. Prediction of the dichotomous remission status variable was not performed here due to sample size limitations in the 5-fold cross-validation step. Therefore, the HDRS-24 post-treatment scores for each participant were extracted from the selected LASSO regression prediction models and were used to classify each participant as a remitter or non-remitter (using the criteria described above). Post-hoc predictive accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity metrics were computed based on the predicted and true HDRS-24 post-treatment scores as previously defined(37).

The above models were then repeated to determine if combining the pre-treatment 5-HTT aggregate score with the 5-HT1A post-synaptic aggregate score and 5-HT1A raphe nucleus binding metrics into one model would explain more of the variance in treatment response than any measure alone.

Pre- or Post-Treatment Group Differences

To investigate differences in binding between HV and patients with BPD before treatment, or patients with BPD post-lithium treatment, linear mixed models were fit with [11C]DASB or [11C]-CUMI-101 binding as the model outcome and group (HV, BPD pre-treatment; or HV, BPD post-treatment), site, region, and sex (for [11C]-CUMI-101 models only) as fixed effects, and subject as a random effect.

Lithium Treatment Effects

To investigate the effect of lithium on binding in patients with BPD, linear mixed models were fit with either [11C]DASB or [11C]-CUMI-101 binding as the model outcome, with pre- or post-treatment status, region, site, or sex (for [11C]-CUMI-101 models only) as fixed effects. Random effects were subject and scan nested within subject.

Associations with Clinical Response

To investigate the relationship between clinical response to lithium and alterations in binding in patients with BPD, linear mixed models were fit with post-treatment HDRS-24 as the model outcome with binding and pre-treatment HDRS-24 as fixed effects. For [11C]DASB data, a subject-level aggregate score for pre-to-post change in imaging was created across all three a priori regions and included as a fixed effect. For [11C]-CUMI-101 analyses, raphe binding was fit in a separate model, and a subject-level aggregate score for pre-to-post change in imaging was created for the post-synaptic regions and included as a fixed effect.

Results:

Sample Characteristics

Summary statistics of clinical variables for the [11C]DASB and [11C]-CUMI-101 clinical sample is presented in Table 1. Of the 27 patients with BPD scanned with [11C]DASB at pre-treatment, 19 went on to complete the lithium trial, and received post-treatment scans. Each subject’s pre- and post-scans were conducted at the same site. HDRS-24 scores significantly decreased following lithium treatment in the [11C]DASB subsample from 27.1 (±4.9) to 15.4 (±9.0) (p<0.001), where 27.8% achieved remission. We found no significant differences in fP (free tracer in plasma) between pre- and post-lithium treatment. Prediction analyses for the [11C]DASB sample were conducted on the 14 patients with BPD that had eight weeks of post-treatment HDRS-24 data. Mean injected dose across participants scanned with [11C]DASB was 522.2 MBq (Range 158.0 MBq – 754.4 MBq).

Table 1:

Sample Characteristics

| [11C]-DASB (N=19) | [11C]-CUMI-101 (N=13) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPD Pre-Lithium | BPD Post-Lithium | p-value | BPD Pre-Lithium | BPD Post-Lithium | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 34.0 ± 12.3 | -- | -- | 30.5 ± 10.5 | -- | -- |

| Sex (% female) | 47.4% | -- | -- | 46.2% | -- | -- |

| HDRS-24 | 27.3 ± 4.9 | 15.5 ± 8.7 | <0.001 | 26.8 ± 4.4 | 15.9 ± 9.2 | 0.001 |

| HDRS-17 Baseline (Inclusion Criteria) |

21.1 ± 4.1 | -- | -- | 21.9 ± 3.8 | -- | -- |

| % Remitted* | -- | 26.3% | -- | -- | 23.1% | -- |

| Free Fraction (fp) | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.27 |

| Reference Region Binding** | -- | -- | -- | 6.2 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 1.7 | 0.61 |

Abbreviations: HDRS – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, BPD = bipolar depression

remission defined as <10 on HDRS-24 post-treatment and >= 50% reduction in HDRS-24 from pre to post-treatment

Region: cerebellar grey matter VT (volume of distribution)

Of the 27 patients with BPD scanned with [11C]DASB, 21 of these patients with BPD also received [11C]-CUMI-101 pretreatment scans, and 13 of those went on to receive post-treatment [11C]-CUMI-101 scans. Each subject’s pre- and post-scans were conducted at the same site. HDRS-24 scores also significantly decreased in the [11C]-CUMI-101 subsample following lithium treatment in the whole group from 26.8 (±4.4) to 15.9 (±9.2) (p=0.001) on average, where 23.1% subjects achieved remission. We found no significant differences in fP (free tracer in plasma) between pre- and post-lithium treatment in either sample, and no significant difference in reference region binding (grey matter of the cerebellum) for the [11C]-CUMI-101 sample between pre- and post-lithium treatment groups (p>0.05) (this was not analyzed for the [11C]DASB sample as no ideal reference exists for this region). Prediction analyses were conducted on the 14 patients with BPD that had eight weeks of post-treatment HDRS-24 data. Mean injected dose across participants scanned with [11C]CUMI was 547.4 MBq (Range 127.8 MBq – 751.5 MBq).

Prediction of Treatment Response

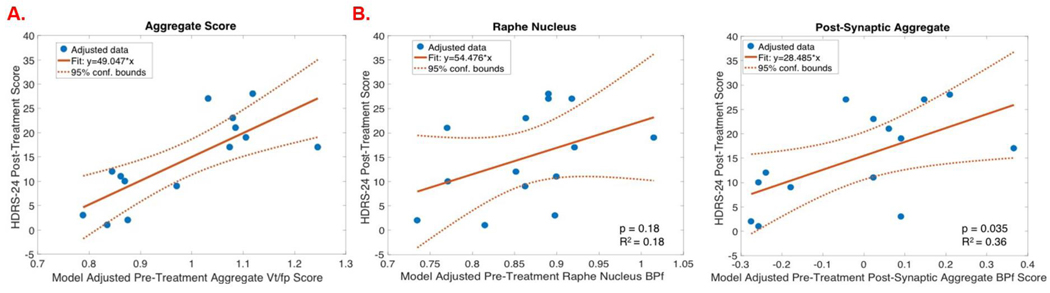

The pre-treatment 5-HTT aggregate score (composite score of the three a priori regions) was found to be a significant predictor of treatment response (F=14.83, p=0.003) (Fig 2A). Anterior cingulate, amygdala, and midbrain pre-treatment 5-HTT binding were each found separately to be significant predictors of lithium treatment response (anterior cingulate: p=0.005; amygdala: p=0.015; midbrain: p=0.003; Fig 1A/B). With 10 repetitions of 5-fold cross-validation, the LASSO linear regression analysis using pre-treatment 5-HTT binding across the a priori regions and pre-treatment HDRS-24 indicated that all entered independent variables (amygdala, midbrain, anterior cingulate and pre-treatment HDRS-24 score) were statistical predictors of post-treatment HDRS-24, agreeing with the previous linear models. Extracting predicted HDRS-24 estimates from the model (using the aggregate score across all three a priori regions), remission status was predicted with 71.4% accuracy, 77.8% specificity, and 60% sensitivity.

Figure 2A:

Regression plots of model adjusted pre-treatment VT/fP (X-axis) by HDRS-24 post-treatment score (Y-axis) for the brain regions selected as significant predictors of treatment response with penalized logistic regression.

2B. Regression plots of model adjusted BPF (X-axis) by HDRS-24 post-treatment score (Y-axis) for the brain regions selected as significant predictors of treatment response with penalized logistic regression (elasticnet).

Figure1A:

Regression plots of model adjusted VT/fP (X-axis) by HDRS-24 post-treatment score (Y-axis) in the brain regions selected as significant predictors of treatment response with penalized logistic regression (elasticnet). Model β estimate shown in solid orange lines, with the model 95% confidence intervals in dashed orange lines (n=14).

1B: VT /fP [11C]DASB voxel maps from single subjects representing range of clinical response.

1C: Regression plots showing model adjusted BPF [11C]CUMI-101 binding potential (X-axis) by HDRS-24 post-treatment score (Y-axis) in the regions selected as significant predictors of treatment response with penalized logistic regression (elastic-net). Model β estimate shown in solid orange lines, with the model 95% confidence intervals in dashed orange lines (n=14).

1D: Single subject voxel-wise BPF [11C]CUMI-101 voxel maps representing range of clinical response.

Raphe nucleus pre-treatment 5-HT1A binding did not significantly predict treatment response (p=0.18; ). The pre-treatment 5-HT1A aggregate score (across the 12 post-synaptic regions) significantly predicted treatment response (F=5.74, p=0.035; Fig 2B). A subset of the 12 post-synaptic regions were found to be significant predictors of treatment response when fit in separate models (amygdala: p=0.016, hippocampus: p=0.015, parahippocampal gyrus: p=0.013, temporal cortex: p=0.039; (Fig 1C/D)). With 10 repetitions of 5-fold cross-validation, the LASSO linear regression analysis using 5-HT1A binding across the a priori regions and pre-treatment HDRS-24 selected amygdala, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus as statistical predictors of post-treatment HDRS-24 (coefficients of all other entered independent variables were shrunk to zero), agreeing with the previous linear models. Extracting predicted HDRS-24 estimates from this model (using the aggregate score across all terminalpost-synaptic field regions), remission status was predicted with 85.7% accuracy, 87.5% sensitivity, and 80% specificity.

Combined logistic regression analyses using pre-treatment 5-HTT and 5-HT1A binding(38) across the a priori regions and pre-treatment HDRS-24 selected a subset of regions (amygdala, midbrain, and parahippocampal gyrus) and pre-treatment HDRS-24 score as significant predictors of post-treatment HDRS-24, partially agreeing with the previous linear models. Extracting predicted HDRS-24 post-treatment estimates from the model, remission status was predicted with 84.6% accuracy, 87.5% specificity, and 60% sensitivity, slightly lowering the predictive accuracy of 85.7% obtained using 5-HT1A binding alone.

Group Differences

No significant differences emerged in binding between controls and pre-treatment ([11C]-DASB: F=0.35, p=0.56; [11C]-CUMI raphe: F=2.24, p=0.14, post-synaptic: F=0.60, p=0.44); or control and post-treatment BPD groups in any region ([11C]-DASB: F=1.69, p=0.20; [11C]-CUMI raphe: F=2.11, p=0.15, post-synaptic: F=0.78, p =0.38).

Associations with Clinical Response

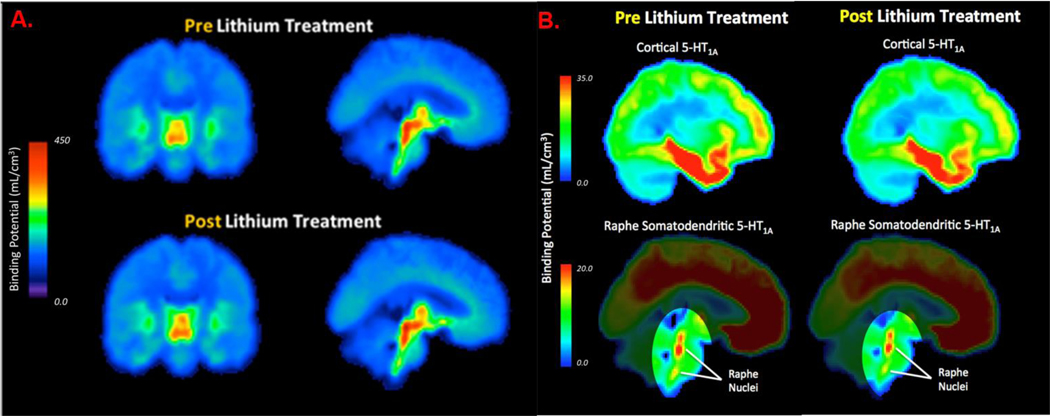

Post-lithium-treatment [11C]DASB or [11C]-CUMI-101 binding did not significantly differ from binding in pre-treatment scans in the a priori [11C]DASB regions (F=1.41, p=0.25; Fig 3A) or in the a priori [11C]-CUMI-101 regions (raphe: F=0.43, p=0.52; post-synaptic regions: F=0.26, p=0.62; Fig 3B), respectively.

Figure 3A:

Group-wise averaged VT /fP voxel maps displaying lithium effect on [11C]DASB 5-HTT binding, where pre-treatment is in top pane and post-treatment is in bottom pane.

3B: Group-wise averaged BPF voxel maps displaying lithium effect on [11C]-CUMI-101 5-HT1A binding, where pre-treatment is in left pane and post-treatment is in right pane.

There was no significant relationship between the change in [11C]DASB binding pre- to post treatment and lithium treatment response (F=1.27 p=0.28; Fig 4A) or the change in [11C]-CUMI-101 binding pre- to post-treatment (raphe: F=1.26, p=0.28; post-synaptic regions: F=1.25, p=0.30 for aggregate score; Fig 4B).

Figure 4A:

Regression plots of model adjusted VT/fP (X-axis) by the change in HDRS-24 score (Y-Axis) in a representative a priori region (n=19).

4B: Regression plots showing model adjusted BPF (X-axis) and the change in HDRS-24 score (Y-Axis) in representative a priori regions: Raphe Nucleus (somatodendritic), Hippocampus (post-synaptic) (n=13).

Discussion

Prediction of Treatment Response

Here we find that 5-HT1A binding before lithium treatment, both as an aggregate score across all 12 a priori post-synaptic regions together, and temporal cortex regions independently (amygdala, hippocampus, parahippocampal grys), was predictive of post-treatment clinical response following 8-weeks of lithium treatment with over 85% accuracy. The temporal lobes (including amygdala and hippocampal formation) have been previously implicated in mood disorders such as unipolar and/or bipolar depression(39, 40), and have been found to be differentially responsive to antidepressant treatment(18, 41, 42). Additionally, previous studies from our lab have found that higher 5-HT1A binding (including in temporal regions) were associated with improved clinical response following 3 months of treatment with SSRIs (18). We also found that 5-HTT binding before lithium treatment, both as an aggregate score across all a priori regions, and each region independently, was able to predict post-treatment clinical response with over 70% accuracy. This accuracy is improved to almost 85% when both 5-HTT and 5-HT1A were included in the predictive model; however, the predictive accuracy of the combined serotonergic metrics was not better than 5-HT1A alone.

Contrary to our previous findings and our hypothesis, the relationship we found was between lower 5-HT1A pre-treatment binding and post-treatment HDRS-24 score as well (the hypothesized) lower 5-HTT pre-treatment binding and post-treatment HDRS-24 score. That is, those subjects with the lowest 5-HTT levels (greatest pre-synaptic serotonergic abnormality, but smallest post-synaptic abnormality) find the greatest benefit from lithium treatment. Our data, then, is consistent with the idea that lithium may act in the pre-synapse to ameliorate depressive symptoms, though potentially not via the candidate proteins examined here.

Interestingly, in both 5-HT1A, 5-HTT, and the combination analysis, the amygdala was found to be a region of significant potential. This is noteworthy, as the amygdala is known to be integral to emotional regulation, especially in relation to BPD(43). Moreover, amygdalar abnormalities including structural and functional changes have been seen in patients with BPD as compared to controls(43). Our group has previously found that decreased 5-HTT binding in the amygdala was predictive of future remission in MDD(19). It is possible the amygdala represents a niche for serotonergic abnormalities present in depression, despite the heterogeneity of the condition. Future work will be necessary to further test this hypothesis.

Taken together with our previous findings(18), we find 5-HT1A levels before treatment could be useful in determining successful treatment course (either via SSRIs or lithium) in BPD. If alterations to 5-HT1A binding do prove to be predictive of treatment outcome, this could have great clinical utility, aiding in treatment selection. Data such as those presented here are the first steps toward personalized treatment plans that will increase the likelihood of treatment success and eventual remission.

Lithium Treatment Response

Despite preclinical evidence suggesting elevations in 5-HTT and downregulation of 5HT1A following lithium exposure(6, 16, 44) we found, in vivo, that lithium monotherapy does not significantly alter 5-HTT or 5-HT1A binding either cortically or subcortically post-treatment. As there was no change in post-treatment binding, it is not surprising that no relationship was found between the change in binding pre-to-post lithium treatment and clinical response. Given that previous studies did not report a relationship between 5-HTT binding and polymorphisms of the 5-HTT gene(12, 45), we did not look at genotype of study participants, and think that this is unlikely to drive this finding.

5-HTT and 5-HT1A Binding in Bipolar Depression: Comparison to Previous Findings

As expected, and recapitulating our previous findings(46), here we find no differences in 5-HTT [11C]-DASB binding between unmedicated patients with BPD and healthy controls. This is inconsistent with a large body of evidence showing dysfunction in 5-HTT as a marker of depression(12, 47). It is possible that a difference in 5-HTT [11C]-DASB binding between depressed patients with BPD and controls is small. If this is true, then the outcome is not likely to be clinically relevant to BPD as a whole. Further, our findings indicate that in this sample of patients with BPD, 5-HT1A binding was not significantly different from healthy controls, contrary to our previous findings 5-HT1A antagonist, [11C]-WAY100635(31). There are several differences between this sample and the previous sample that could contribute to discrepant findings: 1. the previous study found a sex-depending interaction (in males), however the smaller sample size in the current study precluded this type of analysis; 2. the previous study used an antagonist tracer [11C]-WAY100635, whereas we used a partial agonist tracer [11C]-CUMI-101; differences in the two findings could represent a difference in low affinity 5-HT1A (perhaps 5-HT1A availability) that we do not see when specifically examining the high-affinity state. 3. the previous sample was predominantly medication exposed (only 5% medication naïve) whereas we have a higher proportion of medication naïve subjects (38%), though not enough to test their hypothesis that medication naïve patients with BPD would demonstrate exaggerated 5-HT1A differences from controls. We posit that the decreased 5-HTT and elevated 5-HT1A, from previous studies may not be trait markers for BPD, but could be state marker of a specific subset of patients (e.g. males) and a receptor subgroup (e.g. low affinity 5-HT1A). Future studies with larger, and more heterogeneous patients cohorts can test these hypotheses.

Lithium’s Mechanism of Action: An Update

How, then, does lithium work to stabilize mood? It is possible that lithium modulates treatment response via alternative serotonergic mechanisms. For example, it is possible lithium acts indirectly to inhibit 5-HT1B synaptic autoreceptors (via inhibition of GSK3β), thereby increasing serotonin release(48). This model is further complicated by the fact that 5-HT1A receptors have been shown to mediate the relationship between serotonin release and GSK3β inhibition(49), and 5-HTT (serotonin transporter) levels are regulated by 5-HT1B receptor expression. This is consistent with our findings that lithium treatment most benefits subjects with pre-synaptic serotonergic abnormalities (low 5-HTT would allow for prolonged 5-HT in the synapse if 5-HT release is increased). PET studies with 5-HT1B radiotracers, such as [11C]AZ10419369, would help determine whether lithium acts through 5-HT1B to mediate treatment response. Alternatively, it is possible that lithium’s effects are much more complex, leading to changes in a number of systems(50). In this hypothesis, lithium would alter the overall excitation-inhibition balance(51), thereby stabilizing mood. Future studies would be needed to test these and other mechanistic models of lithium’s mood stabilizing effects.

Despite our finding that lithium may not act directly by changing 5-HTT or 5-HT1A density, it is still possible that pretreatment 5-HT1A levels could provide valuable information about a subset of participants that will find symptom relief following Lithium treatment. This leaves us with two interesting avenues to follow-up with: 1) Is there some follow-up time post Lithium treatment where 5-HT1A or 5-HTT density is in fact changed – will we find pre-post differences following a longer follow-up period; 2) What is the upstream target of Lithium, how does it affect clinical symptoms, and how does this target interact/mediate serotonergic tone.

Study Strengths, Limitations, & Future Directions

The strengths of this study include a longitudinal treatment and PET imaging design, a comprehensive PET protocol that takes into account pre- and post-synaptic measures of serotonergic function in each subject, and full quantification PET methods that are not biased by reference region estimates. Limitations include: 1. a small sample size, which precludes investigation into interaction factors, such as sex or BPD subtype; 2. a short washout duration (limited to 3 weeks for ethical reasons), which may not be sufficient to abate treatment effects, though the length of time required for this is unknown and many studies are confounded by heterogenous medication use; 3. scans for both patients and controls conducted across multiple sites, though, importantly, all pre- and post-treatment scans within-participant were conducted at the same site and multiple sites provide a more representative sample.

Conclusion

Understanding the mechanism of one of the few effective treatments for BPD is of great importance and will help to determine a biological marker for treatment response. We find, though lithium may not act directly modulate 5-HTT or 5-HT1A levels, pretreatment 5-HT1A binding is predictive of post-treatment remission status. Future studies should further evaluate 5-HT1A PET as a potential biomarker for lithium treatment response.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study coordinators Kristin Kolb, Sunia Choudhury, Kalynn Gruenfelder, Robert Lopez, Meghan Leonhardt, and study nurse practitioners Sally South and Colleen Oliva. We would also like to thank the Yale PET Center for radiotracer synthesis, PET scanning, and blood analysis. Finally, we thank the Center for Understanding Biology using Imaging Technology (CUBIT) image analysts at SBU for their work in data importing, analysis, and quality control.

Funding

The National Institute of Mental Health provided funding for this study (R01MH090276, PI: Ramin Parsey, MD, PhD).

List of abbreviations:

- BPD

Bipolar Depression

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- 5-HTT

Serotonin Transporter

- 5-HT1A

Serotonin-1A receptor

- HV

healthy volunteer

- SSRI

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor

- CUMC

Columbia University Medical Center

- BNL

Brookhaven National Laboratory

- Yale

Yale University Medical Center

- SBU

Stony Brook University

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – version IV

- HDRS-24

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale – 24 item

- LEGA

Likelihood Estimation in Graphical Analysis

- VT

Distribution Volume

- fP

Free Fraction in Plasma

- BPF

Binding Potential

- SCID

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

Footnotes

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC), Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), Yale University Medical Center (Yale), and Stony Brook University (SBU). All participants provided written, informed consent. Recruitment occurred from March 2008 through June 2017.

Consent for publication

N/A

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Fountoulakis KN, Vieta E, Sanchez-Moreno J, Kaprinis SG, Goikolea JM, Kaprinis GS. Treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder: a critical review. Journal of affective disorders. 2005;86(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geddes JR, Burgess S, Hawton K, Jamison K, Goodwin GM. Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American journal of psychiatry. 2004;161(2):217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hou L, Heilbronner U, Degenhardt F, Adli M, Akiyama K, Akula N, et al. Genetic variants associated with response to lithium treatment in bipolar disorder: a genome-wide association study. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387(10023):1085–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benard V, Vaiva G, Masson M, Geoffroy PA. Lithium and suicide prevention in bipolar disorder. L’Encephale. 2016;42(3):234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song Jie, Sjölander Arvid, Joas Erik, Bergen Sarah E., Runeson Bo, Larsson Henrik ,, et al. Suicidal Behavior During Lithium and Valproate Treatment: A Within-Individual 8-Year Prospective Study of 50,000 Patients With Bipolar Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;174(8):795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carli M, Afkhami-Dastjerdian S, Reader TA. Effects of a Chronic Lithium Treatment on Cortical Serotonin Uptake Sites and 5-HT1A Receptors. Neurochemical Research. 1997;22(4):427–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carli M, Reader TA. Regulation of central serotonin transporters by chronic lithium: an autoradiographic study. Synapse (New York, NY). 1997;27(1):83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho AKS, Loh HH, Craves F, Hitzemann RJ, Gershon S. The effect of prolonged lithium treatment on the synthesis rate and turnover of monoamines in brain regions of rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1970;10(1):72–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treiser S, Kellar KJ. Lithium: effects on serotonin receptors in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;64(2–3):183–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pei Q, Leslie RA, Grahame-Smith DG, Zetterstrom TS. 5-HT efflux from rat hippocampus in vivo produced by 4-aminopyridine is increased by chronic lithium administration. Neuroreport. 1995;6(5):716–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller JM, Hesselgrave N, Ogden RT, Sullivan GM, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ, et al. PET quantification of serotonin transporter in suicide attempters with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):287–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oquendo MA, Hastings RS, Huang YY, Simpson N, Ogden RT, Hu XZ, et al. Brain serotonin transporter binding in depressed patients with bipolar disorder using positron emission tomography. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007;64(2):201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collier DA, Stober G, Li T, Heils A, Catalano M, Di Bella D, et al. A novel functional polymorphism within the promoter of the serotonin transporter gene: possible role in susceptibility to affective disorders. Molecular psychiatry. 1996;1(6):453–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serretti A, Malitas PN, Mandelli L, Lorenzi C, Ploia C, Alevizos B, et al. Further evidence for a possible association between serotonin transporter gene and lithium prophylaxis in mood disorders. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2004;4(4):267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Garcia AL, Newman-Tancredi A, Leonardo ED. 5-HT(1A) [corrected] receptors in mood and anxiety: recent insights into autoreceptor versus heteroreceptor function. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(4):623–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuta T, Segawa T. Chronic effects of imipramine and lithium on postsynaptic 5-HT1A and 5HT1B sites and on presynaptic 5-HT3 sites in rat brain. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1988;47(2):107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQuade R, Leitch MM, Gartside SE, Young AH. Effect of chronic lithium treatment on glucocorticoid and 5-HT1A receptor messenger RNA in hippocampal and dorsal raphe nucleus regions of the rat brain. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18(4):496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lan MJ, Hesselgrave N, Ciarleglio A, Ogden RT, Sullivan GM, Mann JJ, et al. Higher Pretreatment 5-HT(1A) Receptor Binding Potential in Bipolar Disorder Depression is Associated with Treatment Remission: A Naturalistic Treatment Pilot PET Study. Synapse (New York, NY). 2013;67(11): 10.1002/syn.21684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ananth MR, DeLorenzo C, Yang J, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. Decreased Pretreatment Amygdalae Serotonin Transporter Binding in Unipolar Depression Remitters: A Prospective PET Study. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2018;59(4):665–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I) and Axis II Disorders (SCID II). Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2011;18(1):75–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts CA, Jones A, Montgomery C. Meta-analysis of molecular imaging of serotonin transporters in ecstasy/polydrug users. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2016;63:158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartlett EA, Ananth M, Rossano S, Zhang M, Yang J, Lin S, et al. Quantification of Positron Emission Tomography Data Using Simultaneous Estimation of the Input Function: Validation with Venous Blood and Sample Size Considerations. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2018;In Revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogden RT, Ojha A, Erlandsson K, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. In vivo quantification of serotonin transporters using [(11)C]DASB and positron emission tomography in humans: modeling considerations. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2007;27(1):205–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milak MS, DeLorenzo C, Zanderigo F, Prabhakaran J, Kumar JS, Majo VJ, et al. In vivo quantification of human serotonin 1A receptor using 11C-CUMI-101, an agonist PET radiotracer. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(12):1892–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller JM, Oquendo MA, Ogden RT, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. Serotonin transporter binding as a possible predictor of one-year remission in major depressive disorder. Journal of psychiatric research. 2008;42(14):1137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogden RT, Zanderigo F, Choy S, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. Simultaneous estimation of input functions: an empirical study. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2010;30(4):816–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogden RT. Estimation of kinetic parameters in graphical analysis of PET imaging data. Statistics in medicine. 2003;22(22):3557–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsey RV, Kent JM, Oquendo MA, Richards MC, Pratap M, Cooper TB, et al. Acute occupancy of brain serotonin transporter by sertraline as measured by [11C]DASB and positron emission tomography. Biological psychiatry. 2006;59(9):821–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogden RT, Tarpey T. Estimation in regression models with externally estimated parameters. Biostatistics. 2006;7(1):115–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan GM, Ogden RT, Oquendo MA, Kumar JS, Simpson N, Huang YY, et al. Positron emission tomography quantification of serotonin-1A receptor binding in medication-free bipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):223–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;33(1):1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haenisch F, Cooper JD, Reif A, Kittel-Schneider S, Steiner J, Leweke FM, et al. Towards a blood-based diagnostic panel for bipolar disorder. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2016;52:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pripp AH, Stanisic M. Association between biomarkers and clinical characteristics in chronic subdural hematoma patients assessed with lasso regression. PloS one. 2017;12(11):e0186838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramsay IS, Ma S, Fisher M, Loewy RL, Ragland JD, Niendam T, et al. Model selection and prediction of outcomes in recent onset schizophrenia patients who undergo cognitive training. Schizophrenia research Cognition. 2018;11:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tibshirani R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological). 1996;58(1):267–88. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parikh R, Mathai A, Parikh S, Chandra Sekhar G, Thomas R. Understanding and using sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2008;56(1):45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ananth M, Bartlett EA, DeLorenzo C, Lin X, Kunkel L, Vadhan N, et al. Effects of Lithium Monotherapy on the Serotonin-1A Binding and Prediction of Treatment Response in Bipolar Depression. Submitted to AJP. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim CS, Baldessarini RJ, Vieta E, Yucel M, Bora E, Sim K. Longitudinal neuroimaging and neuropsychological changes in bipolar disorder patients: review of the evidence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37(3):418–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price JL, Drevets WC. Neurocircuitry of Mood Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;35:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hajek T, Cullis J, Novak T, Kopecek M, Höschl C, Blagdon R, et al. Hippocampal volumes in bipolar disorders: opposing effects of illness burden and lithium treatment. Bipolar disorders. 2012;14(3):261–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheline YI, Barch DM, Donnelly JM, Ollinger JM, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA. Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50(9):651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garrett A, Chang K. The role of the amygdala in bipolar disorder development. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(4):1285–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Odagaki Y, Koyama T, Matsubara S, Matsubara R, Yamashita I. Effects of chronic lithium treatment on serotonin binding sites in rat brain. Journal of psychiatric research. 1990;24(3):271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shioe K, Ichimiya T, Suhara T, Takano A, Sudo Y, Yasuno F, et al. No association between genotype of the promoter region of serotonin transporter gene and serotonin transporter binding in human brain measured by PET. Synapse (New York, NY). 2003;48(4):184–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller JM, Everett BA, Oquendo MA, Ogden RT, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. Positron Emission Tomography Quantification of Serotonin Transporter Binding in Medication-Free Bipolar Disorder. Synapse (New York, NY). 2016;70(1):24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perry EK, Marshall EF, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Perry RH. Decreased imipramine binding in the brains of patients with depressive illness. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1983;142:188–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polter AM, Li X. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 is an Intermediate Modulator of Serotonin Neurotransmission. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2011;4:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Zhu W, Roh MS, Friedman AB, Rosborough K, Jope RS. In vivo regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK3beta) by serotonergic activity in mouse brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(8):1426–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malhi GS, Tanious M, Das P, Coulston CM, Berk M. Potential mechanisms of action of lithium in bipolar disorder. Current understanding. CNS drugs. 2013;27(2):135–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riad M, Garcia S, Watkins KC, Jodoin N, Doucet E, Langlois X, et al. Somatodendritic localization of 5-HT1A and preterminal axonal localization of 5-HT1B serotonin receptors in adult rat brain. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2000;417(2):181–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]