Abstract

Purpose

Schizophrenia is a chronic, serious, and disabling mental disorder that affects how an individual thinks, feels, and behaves. With the availability of effective antipsychotic medications, the care of people with schizophrenia has shifted from psychiatric hospitals to outpatient treatment and caregivers, including family members. Caregivers are an often-overlooked target for education but may be a key resource to enhance patient education and foster greater adherence to treatment. This study sought to examine the burdens faced by caregivers and determine their specific educational needs.

Methods

A survey instrument was developed and fielded to 96 caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in the United States (September–October 2019) via online communities and caregiver newsletters. Survey responses were organized into specific topics: symptoms exhibited when diagnosed, current treatment options and use of long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic medications, treatment adherence attitudes, barriers for caregivers and patients, informational resources utilized, and caregiver information and educational topics.

Results

Caregivers identified hallucinations, delusions, disorganized behavior, thought disorder, and aggression as the most worrisome symptoms of schizophrenia. Most caregivers felt that they act as a mediator between the medical team and the patient and that they are responsible for the patient’s adherence to treatment. Caregivers report that a schizophrenia diagnosis has strained their own emotional health, reduced their ability to have a satisfying personal life, and disrupted their family life. Caregivers generally had fewer barriers caring for patients receiving LAI antipsychotic treatments than caring for patients not receiving such treatments. Caregivers were interested in learning more about new treatments, coping strategies, and understanding specific symptoms.

Conclusion

Caregivers need help recognizing, understanding, and managing specific and common symptoms of schizophrenia. Information about strategies to handle these symptoms would be beneficial. Caregivers also want information on new and emerging therapies, which may help facilitate discussions with clinicians about different treatment options.

Keywords: long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications, symptom management, emotional health, treatment adherence, families

Plain Language Summary

Caregivers play an important role in managing patients with schizophrenia but sometimes do not receive education targeted specifically to them. As a result, caregivers may be lacking important information that they need in order to care for the patient. For example, caregivers may not understand the benefits of long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic medications. This study aimed to identify the information needed by caregivers to care for patients with schizophrenia and understand how caregivers typically receive information about this illness.

Ninety-six caregivers completed a survey about the following topics on caring for patients with schizophrenia: symptoms experienced by patients, treatment options for schizophrenia, knowledge about LAI antipsychotic medications, patient adherence to treatment, barriers and stressors for patients and caregivers, informational resources for caregivers, and educational needs for caregivers.

Caregivers showed interest in learning about schizophrenia and its treatments. Instead of asking members of their healthcare team or community groups for help, caregivers mostly searched online for resources. Furthermore, caregivers mentioned that caring for patients with schizophrenia caused emotional strain and disruptions in their personal lives. These problems were less worrisome for caregivers of patients receiving LAI antipsychotic medications than for caregivers of patients not receiving LAI antipsychotic medications. Caregivers also expressed concerns about managing symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations.

Together with online resources, healthcare teams and community groups can provide support to caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Education for caregivers should focus on available treatments and the management of common symptoms of schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic, serious, and disabling mental disorder that affects how an individual thinks, feels, and behaves, with an estimated 20.9 million affected individuals worldwide.1,2 Because schizophrenia is a complex disease, patients present with a variety of symptoms, including “positive symptoms,” such as delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behavior, thought disorder, and hostility; “negative symptoms,” such as social withdrawal, lack of pleasure/interest in everyday life, and loss of motivation; and cognitive impairment.3 Quality of life of patients along with their caregivers can be greatly impacted by these symptoms. Schizophrenia can result in severe disability and increased risk of premature death, further impacting families and caregivers.4

The mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia is pharmacotherapy, particularly with antipsychotic medications. However, some patients may have persistent symptoms despite continued use of antipsychotic medications, while others may have difficulty adhering to these treatments for various reasons, such as the avoidance of adverse effects, the perception that treatment is ineffective or not necessary, and the stigma associated with treatment. Alternatives to oral medications are long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic medications, which were first introduced in the 1960s. They are a recommended treatment option for patients with multiple relapses who have a history of non-adherence to oral antipsychotic medications as well as for those who prefer LAI antipsychotic medications over oral antipsychotic medications for routine maintenance treatment.5–9 Recent research suggests that LAI antipsychotic medications could be useful in managing early-phase or first-episode disease9–11 and may be more effective than oral antipsychotic medications in preventing relapse and reducing hospitalization rates.12–14 In addition, switching from an oral antipsychotic to an LAI can provide a meaningful and significant improvement in caregiver burden, as demonstrated in a post hoc analysis of two large randomized multicenter studies originally conducted as part of the clinical development program for paliperidone palmitate three-monthly.15

Over time, care of persons with schizophrenia has shifted from inpatient to outpatient treatment with lay caregivers, such as family members, significant others, or close friends shouldering much of the responsibility in the outpatient setting.16 Even though caregivers of patients with schizophrenia can be a key resource to promote treatment adherence and further patient education, they are an often-overlooked audience for education, creating missed opportunities for contributing to and enhancing treatment.17 Consequently, we designed and conducted a survey study to assess the specific educational needs of caregivers of people with schizophrenia.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

A survey instrument was developed to understand the current challenges and needs within the caregiver community (Supplemental Data). The caregiver survey was distributed via email in September/October 2019 to e-newsletter lists of patient caregivers and other social media outlets. Western Institutional Review Board (Puyallup, WA, USA) exempted the research project from institutional review board oversight under Common Rule 45 CFR § 46.104(d)(2) (the research only included interactions involving survey procedures or interview procedures, and there were adequate provisions to maintain participant privacy and confidentiality). Respondents provided informed consent prior to completing the survey.

Assessment

The survey results were categorized into the following components: (1) symptoms exhibited when diagnosed, (2) current treatment options and use of LAI antipsychotic medications, (3) treatment adherence attitudes, (4) barriers for caregivers and patients with schizophrenia, (5) informational resources utilized, and (6) caregiver information and educational topics. A 5-point Likert scale was used to evaluate caregiver opinions.

For symptoms exhibited when diagnosed, caregivers were asked to select from a list of which symptoms were present at diagnosis along with selecting the top three symptoms that were most worrisome when the patient required hospital admission and also when the patient was not in the hospital. Caregivers were also asked about the treatments that the patients were currently taking and those that they had previously taken. The use of LAI antipsychotic medications was probed as a treatment option, for potential barriers and issues, and for the perceptions of this formulation. Caregiver attitudes toward treatment were assessed by evaluating their opinions on treatment effectiveness, tolerability, and perceived patient’s satisfaction with treatment efficacy and side effects. Additional attitudes assessed opinions on whether patients were taking their medication as prescribed, and caregivers’ ability to act as mediators with patients’ medical teams and their perceived responsibility for maintaining patient adherence to treatment. Caregivers were also asked to rate the importance of various barriers and stressors on themselves, such as disruption of family life, strain on physical health, and increased financial burden. When ascertaining the use of informational resources, caregivers could select all relevant resource types, including internet-based, local community–based, and materials received from a healthcare professional. Caregivers were finally asked about their interest in learning more about schizophrenia and about providing care for individuals with schizophrenia; they were also asked to describe what educational/informational topics would provide the most value to them. For additional details, see Supplemental Data.

Statistical Methods

The data were analyzed using a combination of qualitative (eg, relationship to patient, type of caregiving support, and symptoms of schizophrenia) and quantitative (eg, years since schizophrenia diagnosis, ratings of attitudes regarding treatment options, ratings of barriers and issues) methodology that included descriptive data analysis, open-ended data coding, sub-analyses conducted to understand differences in decision-making using key demographic variables (using chi-square and t-tests), and linear regression analyses to determine key drivers of factors causing increased barriers to care.

Results

Characteristics of Caregivers

The study sample consisted of 96 caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Mean caregiver age was 58 years, and the mean patient age was 45 years, with a mean time since symptom onset of 17 years and a mean time since diagnosis of 14 years (Table 1). Most caregivers of patients with schizophrenia were parents, spouses/partners, or other family members (94%), with 54% residing in a suburban area (Table 1). The most common types of support they provided included coordinating medical care (74%), taking patients to medical appointments (73%), performing household tasks (71%), and managing finances (71%); they also supervised medication administration (67%), drove for errands (67%), and did shopping (66%) (Table 1). On average, caregivers spent 31 h per week providing care for patients with schizophrenia. Slightly more than one-third of caregivers (37%) spent 1–10 h per week providing care, with the remainder spending more than 10 h per week.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Caregivers

| Characteristic | Caregiver (N=96) |

|---|---|

| Mean caregiver age, years (SD) | 58 (11.5) |

| Mean patient age, years (SD) | 45 (19.6) |

| Years since symptom onset, mean (SD) | 17 (13.4) |

| Years since diagnosis, mean (SD) | 14 (14.3) |

| Relationship to patient, % | |

| Parent | 57 |

| Family (non-parent) | 25 |

| Spouse/partner | 12 |

| Paid caregiver | 6 |

| Type of support provided by caregiver, % | |

| Coordinating medical care | 74 |

| Taking to medical appointments | 73 |

| Household tasks | 71 |

| Managing finances | 71 |

| Driving for errands | 67 |

| Medication supervision | 67 |

| Shopping | 66 |

| Participating in recreational activities | 49 |

| Other | 32 |

| Residence, % | |

| Urban | 21 |

| Suburban | 54 |

| Rural | 25 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

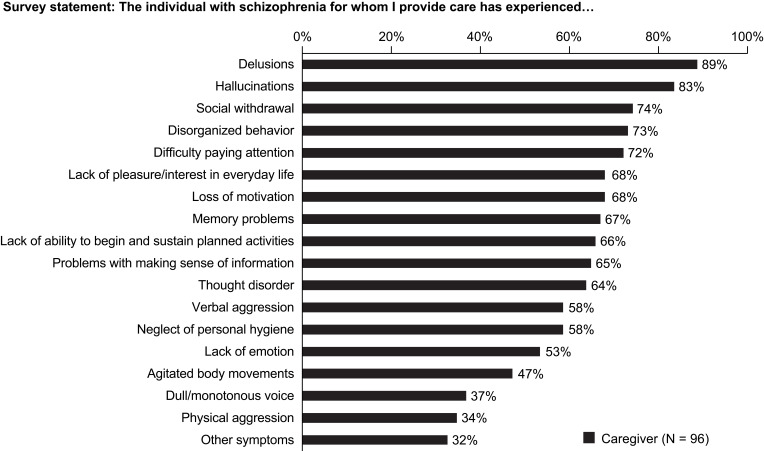

Symptoms Exhibited When Diagnosed

When the patients were first diagnosed, the most common symptoms caregivers reported were delusions (89%) and hallucinations (83%), followed by social withdrawal (74%), disorganized behavior (73%), and difficulty paying attention (72%; Figure 1). For caregivers, the most worrisome symptoms when hospital admission was required were delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behavior, thought disorder, verbal aggression, and physical aggression (data not shown). The most worrisome schizophrenia symptoms when the patient was not in the hospital were similar but also included the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as social withdrawal, lack of pleasure/interest in everyday life, and loss of motivation (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Symptoms exhibited when diagnosed.a

Note: aSurvey included definitions for hallucinations, delusions, disorganized behavior, and thought disorder.

Current Treatment Options and Use of LAI Antipsychotic Medications

Caregivers reported oral antipsychotic medications (79%), psychotherapy (43%), and LAI antipsychotic medications (18%) as the most common current treatments (Supplemental Figure 1). The most common past treatments were psychotherapy (34%), oral antipsychotic medications (25%), and LAI antipsychotic medications (21%; Supplemental Figure 1).

In this survey, 33% of caregivers reported having a conversation with a doctor or other healthcare provider about an injectable medication to help the patient with managing symptoms and preventing relapse. Most (50–76%) of the time, the conversation was initiated by healthcare providers, but sometimes the caregivers made the first inquiries.

For potential issues regarding the use of LAI antipsychotic medications instead of oral medications, caregivers of patients with schizophrenia who had no LAI antipsychotic treatment history identified higher cost of injectable medication compared with oral medication as the most important barrier to use, followed by lack of information about what the medication does and lack of control over the medication (Supplemental Figure 2). On the other hand, those caring for patients with LAI antipsychotic treatment history identified a lack of information about what the medication does as the most important barrier to use, followed by a lack of control over the medication and a higher cost of injectable medication compared with oral medication (Supplemental Figure 2). Caregivers of patients who were or were not currently using an LAI antipsychotic medication agreed that these are as safe as other medications for schizophrenia management (mean score: 3.6 and 3.1 on a 5-point Likert scale, respectively; Supplemental Figure 3). Even though they agreed that society stigmatizes people with schizophrenia (mean score: 4.5 and 4.3), they did not think that the societal stigma toward schizophrenia is worse for individuals who receive their treatment by injection versus orally (mean score: 2.1 and 2.6, respectively; Supplemental Figure 3).

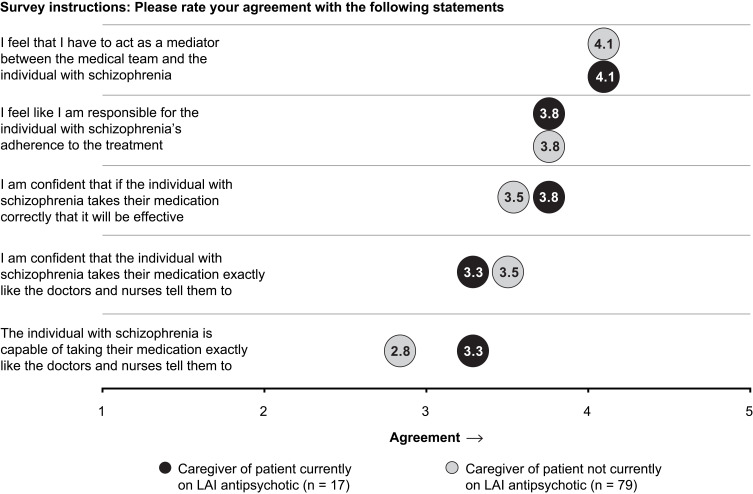

Treatment Adherence Attitudes

Caregivers reported that they act as a mediator between the medical team and the patient (mean score: 4.1) and that they are responsible for the patient’s therapeutic adherence (mean score: 3.8) regardless of whether the patient was or was not currently using an LAI antipsychotic medication (Figure 2). Caregivers of patients currently receiving an LAI antipsychotic medication were more likely to agree that a patient with schizophrenia is capable of taking their medication exactly as the doctors and nurses instructed (mean score: 3.3) versus patients not currently receiving an LAI antipsychotic medication (mean score: 2.8; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Treatment adherence attitudes.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable.

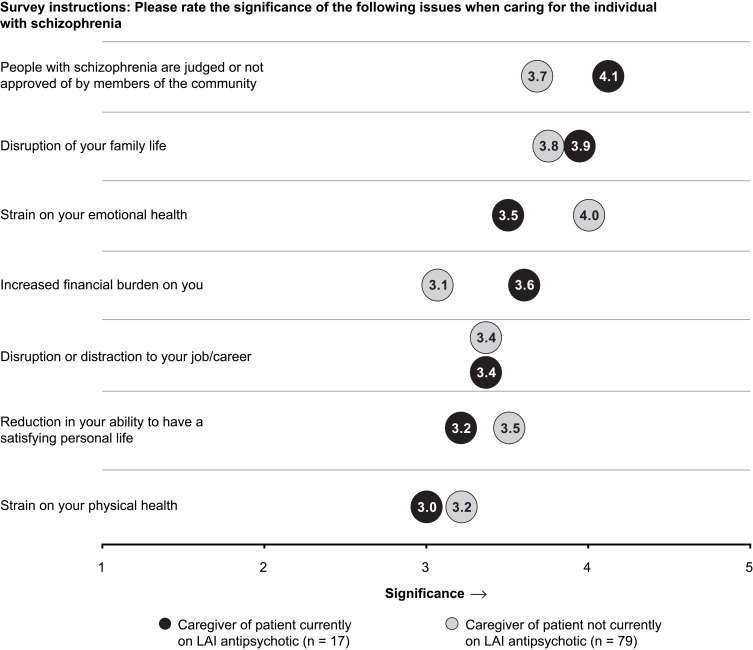

Barriers for Caregivers and Patients with Schizophrenia

The most significant barriers when caring for an individual with schizophrenia were judgment or lack of approval by members of the community, disruption in family life, and strain on emotional health (Figure 3). Caregivers of patients using LAI antipsychotic medications experienced less strain on their emotional health (mean score: 3.5 versus 4.0) and less inability to have a satisfying personal life (mean score: 3.2 versus 3.5) than those caring for patients not using those treatments (Figure 3). However, caregivers of patients receiving LAI antipsychotic medications reported more financial burden (mean score: 3.6 versus 3.1), and judgment/lack of approval by members of the community (mean score: 4.1 versus 3.7; Figure 3). Caregivers of patients using LAI antipsychotic medications reported some barriers as less noteworthy than those caring for patients not using these treatments; specifically, they identified fear of needles, higher cost of injectable medication, lack of control over medication, and lack of information about what the medication does as barriers (Supplemental Figure 2). Regression analyses were performed to determine if any specific demographic or descriptor could predict increased overall burden for caregivers; the only significant predictor was if the patient experienced delusions or expressed physical aggression (data not shown). No other attitude or demographic, including patient or caregiver age, predicted higher burden for caregivers.

Figure 3.

Barriers for caregivers and patients with schizophrenia.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable.

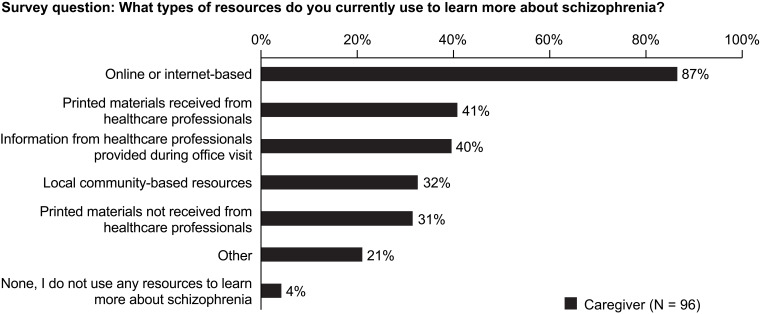

Information and Resources Needed and Utilized

Nearly one-half (49%) of caregivers indicated that they used online support resources regularly, and about one-third (38%) used community services regularly. Additionally, about one-half of caregivers (51%) strongly agreed or agreed that local community support resources were inadequate sources of help or encouragement, while about one-quarter (26%) of caregivers strongly agreed or agreed that online support resources were inadequate sources of help or encouragement.

Caregivers used a variety of resources to learn more about schizophrenia. The most common informational resource used by caregivers was online or internet-based resources (87%; Figure 4); the primary website visited was www.nami.org (National Alliance on Mental Illness [NAMI]). Other resources used included printed materials received from healthcare professionals (41%) and information from healthcare professionals provided during office visits (40%; Figure 4). Less frequently used resources were local community–based resources (32%), printed materials from sources other than healthcare professionals (31%), and other (21%; Figure 4). Four percent of caregivers responded that they did not use any resources to learn more about schizophrenia (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Informational resources utilized.

Caregiver Information and Educational Topics

Caregivers were interested in learning more about schizophrenia and its treatment (mean score: 4.3) and about providing care for individuals with schizophrenia (mean score: 4.2). When asked what informational or educational topic(s) related to schizophrenia and its treatment would be most valuable, caregivers indicated that information on new medications, coping as a caregiver, understanding specific symptoms, housing and helping patients become independent, and establishing support groups in their areas would be helpful. For new medications, caregivers were interested in how the efficacy of new medications for schizophrenia compares with standard medications. A specific coping concern was how to manage living with and helping a patient with schizophrenia, especially when they are not willing to take medication. Negative symptoms were noted as typically not being addressed despite the impact on day-to-day functioning. For becoming independent, supports for behavioral change, motivation, and confidence to act independently were described as desirable. Support groups for addressing issues of loneliness and dating for people with schizophrenia were identified as unmet needs within the community.

Discussion

In this survey, caregivers identified hallucination, delusion, disorganized behavior, thought disorder, and aggression symptoms as the most worrisome when patients with schizophrenia required hospital admission. When the patient was out of the hospital, caregivers were also worried about negative symptoms, such as anhedonia, social withdrawal, and loss of motivation. Caregivers of patients currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications (versus caregivers of patients not currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications) were more likely to view the treatment for schizophrenia as effective, with tolerable side effects, but less likely to believe that patients were satisfied regarding the side effects of their treatment. Most caregivers felt that they act as a mediator between the medical team and the patient and that they are responsible for the patient’s adherence to any treatments for schizophrenia. Caregivers of patients currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications (versus caregivers of patients not currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications) were more likely to feel that patients are capable of being adherent to their medication. Most caregivers believed that a schizophrenia diagnosis has led to strain on their own emotional health, reduced their ability to have a satisfying personal life, and disrupted their family life. The burden of caring for a patient with schizophrenia may have been further influenced by the older age of the caregivers in this study (mean 58 years) with the majority of caregivers being parents of the individual under their care (57%). However, caregivers of patients currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications also generally had fewer barriers to care than those with patients not receiving LAI antipsychotic medications, except for financial burden. Increased burden was not linked to any specific demographic but was associated with caring for patients who have delusions and/or physical aggression. Caregivers of patients who have LAI antipsychotic treatment history indicated fewer barriers to use of injectable therapy.

The results of this survey study suggest a need for greater educational efforts for lay caregivers (eg, family members, significant others, or close friends) of patients with schizophrenia. Specifically, these findings revealed that the most needed educational efforts should focus on helping caregivers identify and cope with specific common symptoms of schizophrenia; sharing information on new and emerging therapies to facilitate discussions with clinicians; and helping promote treatment adherence and patient education. These results may be especially relevant given the paucity of literature addressing the educational needs of those who care for patients with schizophrenia.17

Symptoms of schizophrenia can be a source of distress for caregivers.18 In this survey, caregivers identified several positive symptoms that are worrisome when the patient needs to be admitted to the hospital, as well as both positive and negative symptoms that are worrisome when the patient is not in the hospital. They expressed the need for help in recognizing, understanding, and managing specific common symptoms of schizophrenia; particularly, delusions and aggression. Therefore, information about strategies to handle these symptoms when they arise would be beneficial.

The survey results also support the potential benefits of LAI antipsychotic medications, which remain an important therapeutic option in the treatment of schizophrenia.10 Literature supporting benefits for caregivers include a pooled analysis of two double-blind, randomized Phase 3 studies of an LAI antipsychotic medication in which caregiver burden improved significantly when patients switched from oral antipsychotic medications to LAI antipsychotic medications, with less impact on leisure days and fewer hours spent in caregiving (p < 0.001).15 In this study, caregivers of patients currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications were more likely than caregivers of patients not currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications to report that treatment was effective, with tolerable side effects. Other positive impacts of using LAI antipsychotic medications were that caregivers reported having fewer barriers caring for patients, they perceived them as safe as other treatments, and that the societal stigma was not worse for individuals receiving injections rather than oral medication. Despite caregiver support for LAI antipsychotic medications, less than one-quarter of caregivers reported that patients under their care used these medications, and only one-third reported having a conversation with a doctor or other healthcare provider about an injectable medication to help manage symptoms and prevent relapse. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies suggesting that LAI antipsychotic medications are underutilized.9,10

As reported by caregivers in this survey, several barriers to the use of LAI antipsychotic medications were reported, such as cost of injectable medication, lack of information regarding the medication’s therapeutic action, and lack of control over the medication. These findings underscore the need for educational efforts for caregivers that focus on LAI antipsychotic medications as treatment options.

Treatment non-adherence is a major obstacle to the treatment of schizophrenia, as about half of patients discontinue treatment during the course of their illness.19–21 Strategies to improve this major problem include caregiver education.19 The importance of the caregiver to the patient’s therapeutic adherence was highlighted in this study because most caregivers reported that they act as a mediator between the medical team and the patient and that they feel responsible for the patient’s adherence to treatment. Those caring for patients currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications were more likely than caregivers of patients not currently receiving LAI antipsychotic medications to feel that individuals are capable of being adherent to their medication.

There were several limitations in this study. The survey was distributed to caregivers via e-newsletter lists and other social media outlets, which may have excluded caregivers of patients with schizophrenia who were not online or social media users (eg, selection bias). In addition, caregivers from certain demographic groups (ie, socioeconomic status and education level) or who cared for patients with certain clinical characteristics (ie, more severe disease and more comorbidities) may have been more likely to respond to the survey. Furthermore, caregiver opinions were reported with descriptive statistics only, which limits the interpretation to only those surveyed and cannot be generalized to the complete population of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. The use of a 5-point Likert scale to evaluate caregiver opinions may have failed to capture additional information, and open-ended data coding may have further simplified nuanced responses because of categorization.

This survey also informs us of how information can be best provided to caregivers. Caregivers appear to prefer online resources to find information about schizophrenia; therefore, targeting online educational programs could provide additional value. Caregivers were also interested in information on new and emerging therapies. This information may help caregivers discuss different treatment options with the patient’s medical team; particularly, clinicians who incorrectly assume that patients and caregivers are reluctant to try new treatment modalities. Education and resources to help establish local support groups may be beneficial for caregivers and individuals with schizophrenia and, in turn, could provide solutions for caregiving and important information on resources for independent living. Increasing awareness of existing resources, such as programs offered by NAMI (http://nami.org) and Mental Health America (https://www.mhanational.org), should be encouraged.

Conclusions

In this survey, caregivers report that their own emotional health has been impacted, reducing their ability to have a satisfying personal life. However, caregivers generally had fewer barriers caring for patients receiving LAI antipsychotic treatments than caring for patients not receiving such treatments. Educational needs of caregivers of people with schizophrenia were further identified, including the desire for more information about the disorder and optimal medication use.

Acknowledgments

Professional medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Jennifer DiNieri, PhD, and Brian Haas, PhD, CMPP, of Ashfield MedComms, part of UDG Healthcare PLC, and supported by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc. The authors take full responsibility for the content of this article. This paper was presented at the Psych Congress 2020 as a poster presentation. The poster (poster 140) can be found at https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/pcn/posters/educational-needs-caregivers-patients-schizophrenia-results-national-survey-study

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc.

Abbreviations

LAI, long-acting injectable; SD, standard deviation.

Disclosure

EB, GDS: research study support: Teva Pharmaceuticals. LC: consultant: AbbVie, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Axsome Therapeutics, BioXcel Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cadent Therapeutics, Eisai, Impel NeuroPharma, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, Luye Pharma Group, Lyndra Therapeutics, Medavante-ProPhase, Merck, Neurocrine Biosciences, Noven, Osmotica Pharmaceutical, Otsuka, Relmada Therapeutics, Sage Therapeutics, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, University of Arizona, and one-off ad hoc consulting for individuals/entities conducting marketing, commercial, or scientific scoping research. Speaker: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Eisai, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Sage, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and continuing medical education activities organized by medical education companies such as Medscape, NACCME, Neuroscience Education Institute, Vindico Medical Education, and universities and professional organizations/societies. Stocks (small number of shares of common stock): Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer purchased more than 10 years ago. Royalties: Wiley (Editor-in-Chief, International Journal of Clinical Practice, through end of 2019); UpToDate (reviewer); Springer Healthcare (book); and Elsevier (Topic Editor, Psychiatry, Clinical Therapeutics). MM, MS: employment, stock: Teva Pharmaceuticals. SS: Nothing to disclose. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, et al. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1195–1203. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel KR, Cherian J, Gohil K, Atkinson D. Schizophrenia: overview and treatment options. P T. 2014;39(9):638–645. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCutcheon RA, Reis Marques T, Howes OD. Schizophrenia – an overview. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(2):201–210. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Citrome L. New second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(7):767–783. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2013.811984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Citrome L. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics update: lengthening the dosing interval and expanding the diagnostic indications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(10):1029–1043. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2017.1371014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Citrome L. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: what, when, and how. CNS Spectr. 2021;26(2):118–129. doi: 10.1017/S1092852921000249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(9):868–872. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.177901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heres S, Lambert M, Vauth R. Treatment of early episode in patients with schizophrenia: the role of long acting antipsychotics. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(Suppl 2):1409–1413. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(14)70001-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl 3):1–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15032su1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Limandri BJ. Long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications: why aren’t they used as often as oral formulations? J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2019;57(3):7–10. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20190218-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang SC, Liao DL, Huang CY, Hsu CC, Cheng SL, Shao YJ. The effectiveness of long-acting injectable antipsychotics versus oral antipsychotics in the maintenance treatment of outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2020;35(3):e2729. doi: 10.1002/hup.2729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957–965. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah A, Xie L, Kariburyo F, Zhang Q, Gore M. Treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization and costs among schizophrenia patients treated with long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics. Adv Ther. 2018;35(11):1994–2014. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0786-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gopal S, Xu H, McQuarrie K, et al. Caregiver burden in schizophrenia following paliperidone palmitate long acting injectables treatment: pooled analysis of two double-blind randomized phase three studies. NPJ Schizophr. 2017;3(1):23. doi: 10.1038/s41537-017-0025-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rofail D, Regnault A, le Scouiller S, Lambert J, Zarit SH. Assessing the impact on caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: psychometric validation of the Schizophrenia Caregiver Questionnaire (SCQ). BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:245. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0951-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svettini A, Johnson B, Magro C, et al. Schizophrenia through the carers’ eyes: results of a European cross-sectional survey. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22(7):472–483. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dillinger RL, Kersun JM. Caring for caregivers: understanding and meeting their needs in coping with first episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;14(5):528–534. doi: 10.1111/eip.12870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaudhari B, Saldanha D, Kadiani A, Shahani R. Evaluation of treatment adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2017;26(2):215–222. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_24_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):892–909. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindström E, Bingefors K. Patient compliance with drug therapy in schizophrenia. Economic and clinical issues. PharmacoEconomics. 2000;18(2):106–124. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200018020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]