Abstract

Meiotic drivers are genetic elements that break Mendel’s law of segregation to be transmitted into more than half of the offspring produced by a heterozygote. The success of a driver relies on outcrossing (mating between individuals from distinct lineages) because drivers gain their advantage in heterozygotes. It is, therefore, curious that Schizosaccharomyces pombe, a species reported to rarely outcross, harbors many meiotic drivers. To address this paradox, we measured mating phenotypes in S. pombe natural isolates. We found that the propensity for cells from distinct clonal lineages to mate varies between natural isolates and can be affected both by cell density and by the available sexual partners. Additionally, we found that the observed levels of preferential mating between cells from the same clonal lineage can slow, but not prevent, the spread of a wtf meiotic driver in the absence of additional fitness costs linked to the driver. These analyses reveal parameters critical to understanding the evolution of S. pombe and help explain the success of meiotic drivers in this species.

Research organism: S. pombe

eLife digest

The fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, is a haploid organism, meaning it has a single copy of each of its genes. S. pombe cells generally carry one copy of each chromosome and can reproduce clonally by duplicating these chromosomes and then dividing into two cells. However, when the yeast are starving, they can reproduce sexually. This involves two cells mating by fusing together to create a ‘diploid zygote’, which contains two copies of each gene. The zygote then undergoes ‘meiosis’, a special type of cell division in which the zygote first duplicates its genome and then divides twice. This results in four haploid spores which are analogous to sperm and eggs in humans that each contain one copy of the genome. The spores will grow and divide normally when conditions improve.

The genes carried by each of the haploid spores depend on the cells that formed the zygote. If the two ‘parent’ yeast had the same version or ‘allele’ of a gene, all four spores will have it in their genome. However, if the two parents have different alleles, only 50% of the offspring will carry each version. Although this is usually the case, there are certain alleles, called meiotic drivers, that are transmitted to all offspring even in situations where it is only carried by one parent. Meiotic drivers can be found in many organisms, including mammals, but their behavior is easiest to study in yeast.

Meiotic drivers known as killers achieve this by disposing of any ‘sister’ spores that do not inherit the same allele of this gene. This ‘killing’ can only happen when only one of the ‘parents’ carries the driver. This scenario is thought to rarely occur in species that inbreed, as inbreeding leads to both gene copies being the same. However, this does not appear to be the case for S. pombe, which contain a whole family of killer meiotic drivers, the wtf genes, despite also being reported to mainly inbreed.

To investigate this contradiction, López Hernández et al. isolated several genetically distinct populations of S.pombe. These isolates were grown together to determine how often the each one would outcross (mate with an individual from a different population) or inbreed. The results found that levels of inbreeding varied between isolates.

Next, López Hernández et al. used mathematical modelling and experimental evolution analyses to study how wtf drivers spread amongst these populations. This revealed that wtf genes spread faster in populations with more outcrossing. In some instances, the wtf driver was linked to a gene that could harm the population. In these cases, López Hernández et al. found than inbreeding could purge these drivers and stop them from spreading the dangerous alleles through the population.

López Hernández et al. establish a simple experimental system to model driver evolution and experimentally demonstrate how key parameters, such as outcrossing rates, affect the spread of these genes. Understanding how meiotic drivers spread is important, as these systems could potentially be used to modify populations important to humans, such as crops or disease vectors.

Introduction

Mating behaviors have long been a focus of art, literature, and formal scientific inquiry. This interest stems, in part, from the remarkable importance of mate choice on the evolution of species. Outcrossing and inbreeding represent distinct mating strategies that both have potential evolutionary benefits and costs (Glémin et al., 2019; Muller, 1932; Otto and Lenormand, 2002). For example, outcrossing (mating between individuals from distinct lineages) can be beneficial because it can help purge deleterious alleles from a line of descent, but it can also be costly as it can promote the spread of selfish genes (Burt and Trivers, 1998; Crow, 1988; Hurst and Werren, 2001; McDonald et al., 2016; Zeyl et al., 1996).

Meiotic drivers represent one type of selfish genetic element that relies on outcrossing to persist and spread in a population (Lindholm et al., 2016; Sandler and Novitski, 1957). These loci can manipulate the process of gametogenesis to bias their own transmission into gametes at the expense of the rest of the genome (Burt and Trivers, 2006). Meiotic drivers are often considered selfish or parasitic genes because they generally offer no fitness benefits to their hosts and are instead often deleterious or linked to deleterious alleles (Dyer et al., 2007; Higgins et al., 2018; Klein et al., 1984; Rick, 1966; Schimenti et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 1999; Wilkinson and Fry, 2001). As inbreeding is thought to inhibit the spread of selfish genes like drivers, drivers are predicted to be unsuccessful in species that rarely outcross (Burt and Trivers, 1998; Hurst and Werren, 2001). This assumption appears to be challenged in several fungal species, including the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Grognet et al., 2014; Hammond et al., 2012; Svedberg et al., 2021; van der Gaag et al., 2000; Vogan et al., 2021).

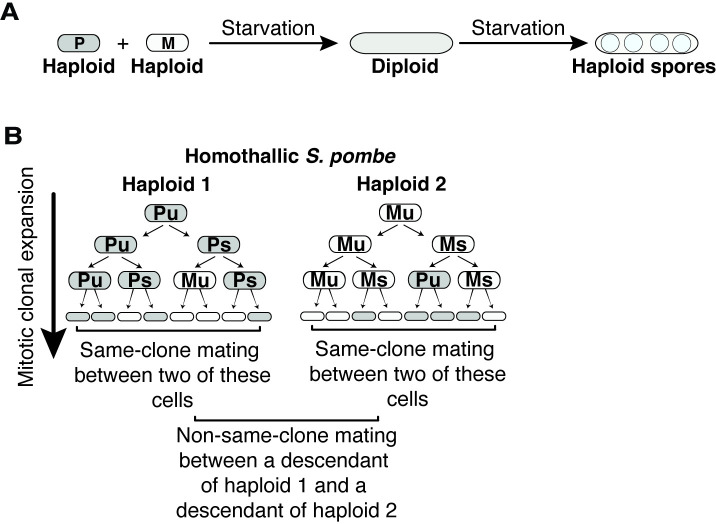

Generally, S. pombe cells grow as haploids and their mating (fusion of two haploids of opposite mating type) generates diploid zygotes that can then undergo meiosis to generate haploid progeny known as spores (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). Mating in S. pombe is widely thought to preferentially occur between daughter cells clonally derived from a common progenitor via a recent mitotic division, which we refer to as ‘same-clone mating’ (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B; Egel, 1977; Gutz and Doe, 1975; Miyata and Miyata, 1981; Billiard et al., 2012; Perrin, 2011). The support for this idea is described below. Despite this notion that S. pombe cells preferentially undergo same-clone mating (leading to inbreeding), S. pombe isolates host multiple meiotic drivers (Bravo Núñez et al., 2020b; Eickbush et al., 2019; Farlow et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2017; Nuckolls et al., 2017; Zanders et al., 2014).

In the wild, a minority of S. pombe strains are heterothallic, meaning they have a fixed mating type (h+ or h-; Gutz and Doe, 1975; Nieuwenhuis and Immler, 2016; Schlake and Gutz, 1993). Heterothallic S. pombe strains must mate with non-clonally related cells of the opposite mating type to complete sexual reproduction (Egel, 1977; Gutz and Doe, 1975; Leupold, 1949; Miyata and Miyata, 1981; Nieuwenhuis and Immler, 2016; Osterwalder, 1924; Schlake and Gutz, 1993). However, most isolates of S. pombe are homothallic, that is, they can switch between the two mating types (h+ and h-) during clonal expansion via mitosis (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B; Egel and Eie, 1987; Gutz and Doe, 1975; Klar, 1990; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2018; Singh and Klar, 2003). Homothallism in S. pombe enables mating to occur between cells clonally derived from the same progenitor via mitosis (Billiard et al., 2012). Mating can even occur between two cells produced by a single mitotic cell division (Egel, 1977; Gutz and Doe, 1975; Miyata and Miyata, 1981).

It is often assumed that homothallic fungi, like S. pombe, do not generally mate with non-clonally related cells. It is important to note, however, that homothallism in fungi does not inherently lead to mating between clonally related cells (Giraud et al., 2008). Under some conditions, such as when gametes are dispersed and finding a mate is costly, homothallism can be a beneficial strategy for outcrossing species as it ensures gamete compatibility (Billiard et al., 2012). In addition, population genetic analyses of one homothallic fungus, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, support that homothallism is compatible with frequent outcrossing (Attanayake et al., 2014).

Very little is known about the ecology of S. pombe in the wild, including how often S. pombe cells outcross (Jeffares, 2018). In the lab, the mating propensities of S. pombe have mostly been investigated in derivatives of a strain first isolated from French wine in 1921 (Osterwalder, 1924). In this work, we will refer to derivatives of this isolate as ‘Sp’. Distinct homothallic Sp strains can be induced to mate in the lab (i.e., outcrossed), but such crosses are significantly more challenging to execute than crosses between heterothallic isolates. The relative difficulty associated with outcrossing homothallic strains has been attributed to preferential same-clone mating (Ekwall and Thon, 2017; Forsburg and Rhind, 2006). Microscopy experiments have supported the idea that homothallic Sp haploids tend to undergo same-clone mating (Bendezú and Martin, 2013; Egel, 1977; Leupold, 1949; Miyata and Miyata, 1981). However, the precise level of same-clone mating when homothallic S. pombe cells are among nonclonal sexual partners has not, to our knowledge, been formally reported for any isolate.

Population genetic analyses have provided additional support for the notion that S. pombe inbreeds. There are two major S. pombe lineages that diverged between 2300 and 78,000 years ago (Tao et al., 2019; Tusso et al., 2019). Much of the sampled variation within the species represents different admixed hybrids of those two ancestral lineages resulting from an estimated 20–60 outcrossing events (Tusso et al., 2019). This low outcrossing rate could result from limited opportunities to outcross, preferential same-clone mating, or a combination of the two. It is important to note, however, that the outcrossing rate estimates in S. pombe are likely low as pervasive meiotic drive and decreased recombination in heterozygotes suppress the genetic signatures that are used to infer outcrossing (Bravo Núñez et al., 2020b; Hu et al., 2017; Nuckolls et al., 2017; Zanders et al., 2014).

Accounting for all these factors to generate a more accurate S. pombe outcrossing rate from population genetic data is currently an insurmountable obstacle for several reasons. First, the landscape of meiotic drivers and their suppressors is complex in that more than four drivers and more than eight suppressors of drive could be present in a given heterozygote produced by outcrossing (Eickbush et al., 2019; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a). Predicting how those factors will affect allele transmission is well beyond the capabilities of current population genetic models, even if the epistatic relationships within the drive systems were understood, which they currently are not. In addition to the drivers, S. pombe isolates contain an array of chromosomal rearrangements and other unknown barriers to recombination (Avelar et al., 2013; Brown et al., 2011; Jeffares et al., 2017; Tusso et al., 2019; Zanders et al., 2014). Importantly, recombination rates are also inextricably linked to the complex drive landscape because the presence of drivers also affects the recombination rate within viable offspring, independent of chromosomal rearrangements (Bravo Núñez et al., 2020b).

Given those limitations, the current laboratory knowledge and outcrossing rate estimates suggest that drivers would infrequently have the opportunity to act in S. pombe (Egel, 1977; Ekwall and Thon, 2017; Forsburg and Rhind, 2006; Gutz and Doe, 1975; Miyata and Miyata, 1981; Tusso et al., 2019). In fact, the notion that S. pombe infrequently outcrosses has even been used to challenge the idea that S. pombe meiotic drivers are truly selfish genes that persist due to meiotic drive (Sweigart et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the S. pombe genome houses numerous meiotic drive genes from the wtf gene family (Bravo Núñez et al., 2018; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a; Eickbush et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2017; Nuckolls et al., 2017).

The wtf drivers destroy the meiotic products (spores) that do not inherit the driver from a heterozygote. Each wtf drive gene encodes both a Wtfpoison and a Wtfantidote protein that, together, execute targeted killing of the spores that do not inherit the wtf driver (Hu et al., 2017; Nuckolls et al., 2017). In the characterized wtf4 driver, the Wtf4poison protein assembles into toxic protein aggregates that are packaged into all developing spores. The Wtf4antidote protein co-assembles with Wtf4poison only in the spores that inherit wtf4 and likely neutralizes the poison by promoting its trafficking to the vacuole (Nuckolls et al., 2020). Spore killing by wtf drivers leads to the loss of about half of the spores and almost exclusive transmission (>90%) of the wtf driver from a heterozygote (Hu et al., 2017; Nuckolls et al., 2017). Despite their heavy costs to the fitness of heterozygotes, the drivers are successful in that all assayed S. pombe isolates contain multiple wtf drivers (4–14 drivers; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a; Eickbush et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2017). In addition to those drivers, the S. pombe isolates also contain between 8 and 17 suppressors of drive that encode only a Wtfantidote protein.

In this work, we exploited the tractability of S. pombe to better understand how mating phenotypes, particularly inbreeding propensity, could affect the spread of a meiotic driver in this species. Despite limited genetic diversity among isolates, we observed natural variation in inbreeding propensity and other mating phenotypes. Some natural isolates preferentially undergo same-clone mating in the presence of a potential outcrossing partner, whereas others mate more randomly. Additionally, we found that the level of same-clone mating can be altered by cell density and affected by the available sexual partners. This is important as it highlights that our measured values in the lab are not meant to indicate precise levels of outcrossing that would occur under unknown natural conditions.

To explore the effects that varying mating phenotypes could have on the spread of a wtf driver in a population, we used both mathematical modeling and an experimental evolution approach. We found that, while the spread of a wtf driver could be slowed by the observed levels of same-clone mating, the driver could still spread in the absence of linked deleterious traits. We incorporated our observations into a model in which rapid wtf gene evolution and occasional outcrossing facilitate the maintenance of wtf drivers. More broadly, this study illustrates how the success of drive systems is impacted by mating phenotypes.

Results

Same-clone mating propensity differs among S. pombe natural isolates

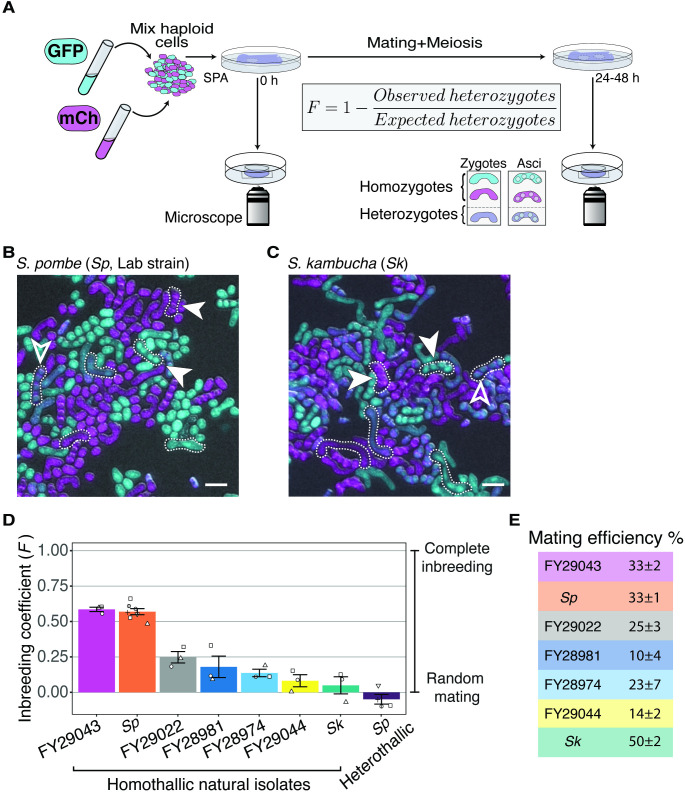

To quantify mating propensities of homothallic S. pombe strains in the presence of other potential homothallic sexual partners, we first generated fluorescently tagged strains to easily observe mating via microscopy (Figure 1A). We marked strains with either GFP or mCherry (both constitutively expressed and integrated at the ura4 locus). We then mixed equal proportions of GFP-expressing and mCherry-expressing haploid cells and plated them on a medium (SPA) that induces one round of mating and meiosis. We imaged the cells immediately after plating to measure the starting frequency of both parent types. We then imaged again 24–48 hr later when many cells in the population had mated to either form zygotes or fully developed spores. We inferred the genotypes (homozygous or heterozygous) of each zygote and ascus (spore sac) based on their fluorescence (Figure 1A). Homozygotes were produced by mating of two cells carrying the same fluorophore, while heterozygotes were produced by mating between a GFP-labeled and an mCherry-labeled cell (Figure 1B and C). Finally, we calculated the inbreeding coefficient (F) by comparing the observed frequency of heterozygotes to the frequency expected if mating was random (F = 1–observed heterozygotes/expected heterozygotes; Figure 1A). Exclusive mating between cells with the same fluorophore, random mating, and exclusive mating between cells with different fluorophores would yield coefficients of 1, 0, and –1, respectively (Hartl and Clark, 2007). This assay occurs in a specific laboratory context, so the conditions differ from those in the wild. Importantly, however, we assay all strains under the same conditions, so the assay is sufficient to explore possible variation in mating phenotypes between different isolates of S. pombe.

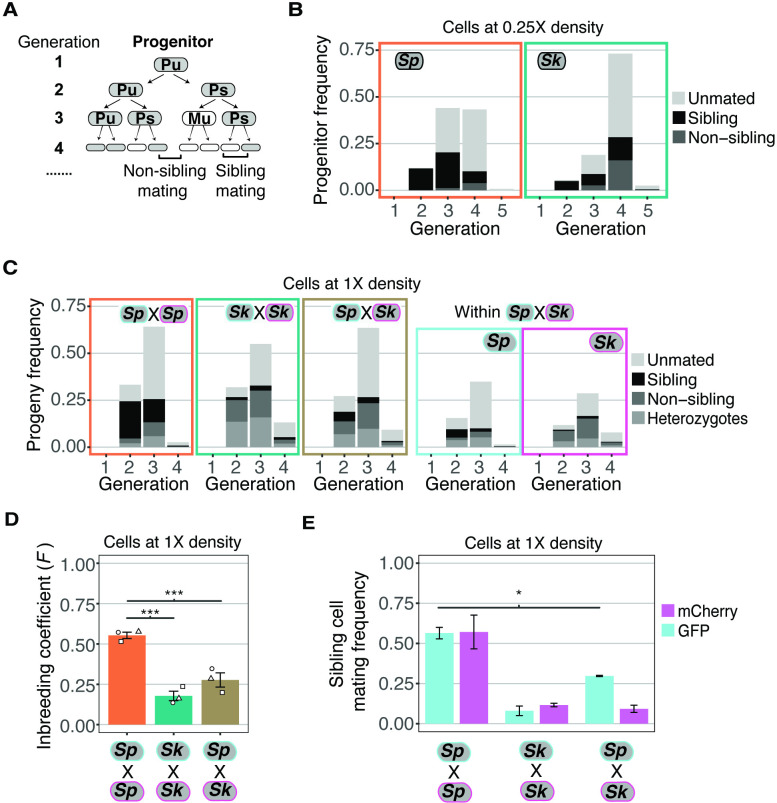

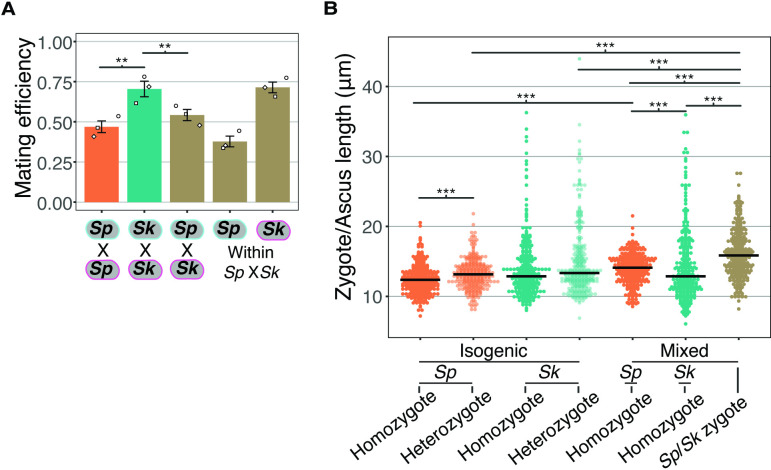

Figure 1. Inbreeding coefficients vary between homothallic isolates of Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

(A) Experimental strategy to quantify mating patterns between mixed homothallic isolates. GFP (cyan)- and mCherry (magenta)-expressing cells were mixed and placed on SPA medium that induces mating and meiosis. An agar punch from this plate was imaged to assess the initial frequencies of each haploid strain. After incubation at 25°C for at least 24 hr, another punch was imaged to determine the number of homozygous and heterozygous zygotes/asci based on their fluorescence. The inbreeding coefficient (F) was calculated using the formula shown. (B and C) Representative images of the mating in Sp (B) and Sk (C) isolates after 24 hr. Filled arrowheads highlight examples of homozygous asci whereas open arrowheads highlight heterozygous asci. A few additional zygotes are also outlined with dotted lines in the images. Scale bars represent 10 µm. (D) Inbreeding coefficient of homothallic natural isolates and complementary heterothallic (h+,h- mCherry and h+,h- GFP) Sp lab strains. At least three biological replicates per isolate are shown (open shapes). (E) Mating efficiency of the isolates shown in (D) (%) ± standard error from three biological replicates of each natural isolate.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Sexual cycle of Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Inbreeding coefficients can be affected by cell density.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Homothallism of natural isolates.

Figure 1—figure supplement 4. Density variation in plated cells.

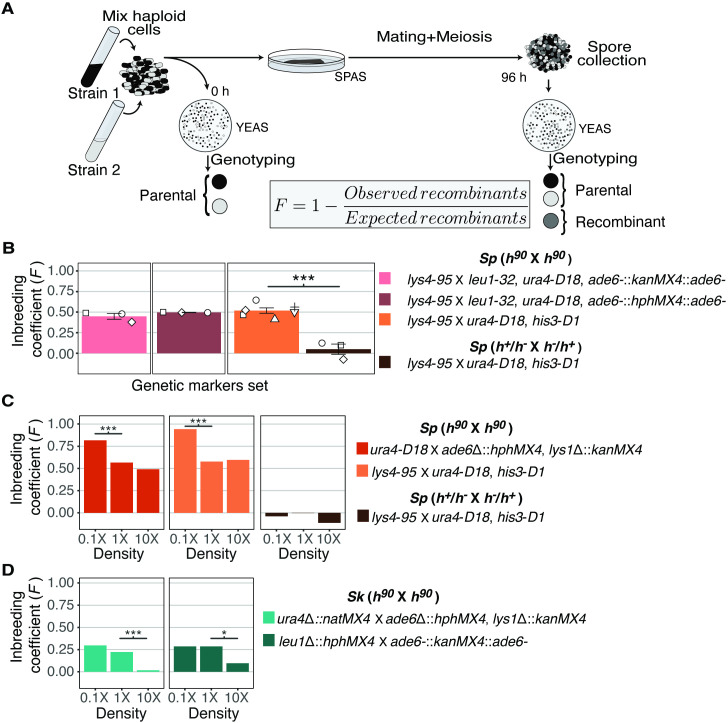

In homothallic cells of the common lab isolate, Sp, we measured an average inbreeding coefficient of 0.57 using our microscopy assay (Figure 1B and D). As a control, we also assayed a mixed heterothallic population containing roughly equal amounts of GFP-expressing and mCherry-expressing cells of both mating types. We expected this control population to exhibit random mating between GFP- and mCherry-expressing cells, as heterothallic cells cannot undergo same-clone mating. We did observe random mating of this mixed heterothallic population (F = −0.05), which helps validate our assay (Figure 1D). To further validate our microscopy results, we also assayed Sp cells using an orthogonal approach employing traditional genetic markers. For this analysis, we mixed haploid cells on supplemented SPA medium (SPAS) to induce them to mate and undergo meiosis. We then manually genotyped the progeny and used the fraction of recombinant progeny to calculate inbreeding coefficients (Figure 1—figure supplement 2A). The average inbreeding coefficients measured using the genetic assay were very similar to the values we measured using the microscopy assay (0.49 for homothallic Sp cells; Figure 1—figure supplement 2B). Together, our results confirm and quantify previous observations of non-random mating in homothallic Sp cells (Bendezú and Martin, 2013; Egel, 1977). In addition, we demonstrate that our fluorescence assay provides a powerful tool to quantify mating events.

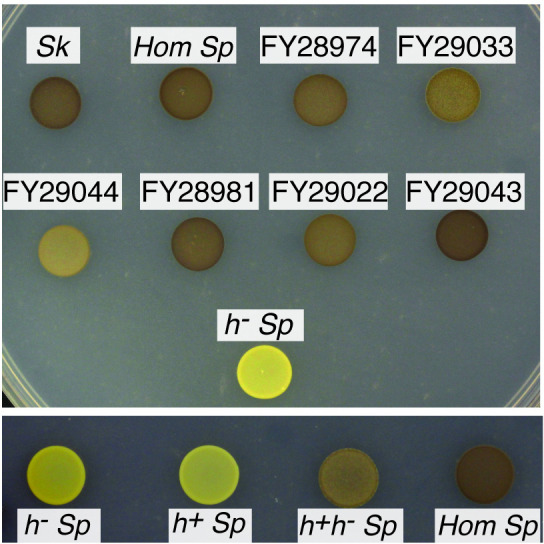

We next extended our analyses to other S. pombe natural isolates collected from the wild. We assayed six additional isolates, FY29043, FY29022, FY28981, FY28974, FY29044, and Schizosaccharomyces kambucha (Sk), using our fluorescence microscopy assay. We chose these isolates because they each contain different fractions of the two inferred ancestral S. pombe lineages (Tusso et al., 2019). In addition, the strains we chose are homothallic, sporulated well, were non-clumping, and we were able to transform them with the GFP and mCherry markers described above (Figure 1—source data 1, Figure 1—figure supplement 3; Jeffares et al., 2015). We found that the measured inbreeding coefficients varied significantly between the different natural isolates (Figure 1D). The phenotype of FY29043 was similar to Sp, but other S. pombe isolates, including Sk, mated more randomly (Figure 1D). We also observed variation in mating efficiency ranging from 10% of cells mating in FY28981 to 50% of cells mating in Sk (Figure 1E).

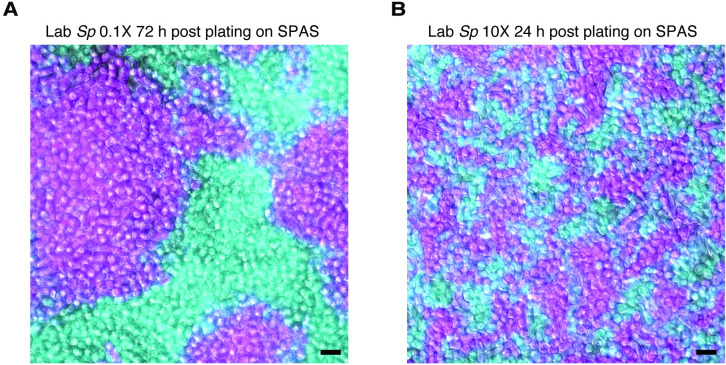

Given that S. pombe cells are immobile, we thought that cell density could affect their propensity to undergo same-clone mating. To test this, we compared the inbreeding coefficients of both homothallic Sp and Sk isolates at three different starting cell densities: our standard mating density (1×), high density (10×), and low density (0.1×). Because crowding prevented us from assaying high-density cells using our microscopy approach, we used the genetic assay for each condition. We found that inbreeding coefficients were higher in both Sp and Sk isolates when cell densities were lower (Figure 1—figure supplement 2C and D). This is likely because cells plated at low density tended to be physically distant from potential sexual partners that were not part of the same clonally growing patch of cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 4). However, a control population consisting of mixed heterothallic Sp cells (h+ and h- cells of two different genotypes mixed in equal proportions) that cannot mate within a clonal patch of cells showed near random mating between the two genotypes at all cell densities assayed (Figure 1—figure supplement 2C). Overall, these experiments demonstrate that inbreeding coefficients vary within S. pombe homothallic isolates and can be affected by cell density.

Additional phenotypes associated with reduced inbreeding coefficients in Sk

We next used time-lapse imaging to explore the origins of the different inbreeding coefficients, focusing on the Sp and Sk isolates. Previous work claimed that Sk cells have reduced mating-type switching efficiency, based on levels of the DNA break (double-strand break site [DSB]) that initiates switching (Singh and Klar, 2002). A mutation at the mat-M imprint site was proposed to be responsible for the reduced level of DSBs (Singh and Klar, 2003).

We reasoned that less mating-type switching could lead to less same-clone mating, as a small population of cells clonally derived from the same progenitor via mitosis would be less likely to contain cells of compatible mating types. This would promote cells mating outside their clonal lineage. One can see evidence consistent with this phenomenon in our experiments varying the cell density of homothallic Sp cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 2C-D). Specifically, we observed more random mating when cells were at higher density, which likely results from more opportunity for cells to mate outside their clonal lineage. We aspired to directly compare mating type switching rates between Sp and Sk cells, although such direct assays have not, to our knowledge, been done in any strain background. We attempted to develop a direct assay using previously described cytological reporters of mating type. The reporters have been used to assay ratios of h + and h- cells in a population (Jakočiūnas et al., 2013, Maki et al., 2018), but we found they were not well-suited for following switching events live in time-lapse imaging in our hands (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A).

Because of this, we decided to further explore the possible differences in mating-type switching frequencies indirectly using time-lapse assays, similar to those used to originally determine the patterns of mating-type switching in Sp (Miyata and Miyata, 1981). As in the classic study of Miyata and Miyata, 1981, we used the first mating event as an imperfect proxy for when cells were capable of mating (i.e., they had a partner of the opposite mating type). For these assays, we tracked the fate of individual homothallic founder cells plated on SPA at low density (0.25× to our standard mating density used above) to quantify how many mitotic generations occurred prior to the first mating event. When the first mating event occurred, we recorded the proportion of the cells present that mated (prior to the appearance of cells from next mitotic generation). We also recorded the relationships between the cells that did mate (Figure 2A). Specifically, we scored whether the mated cells were the product of a single mitotic division. Historically, these have been called ‘sister cells’ in the S. pombe mating literature, although we use the term ‘sibling cells’ to be gender neutral (e.g., Miyata and Miyata, 1981). We did not consider cells that were born in mitotic generations past the one in which mating first occurred (Figure 2A). For example, if cells within a given lineage first mated at generation 3, we scored the relationships between those mated cells and recorded how many unmated cells remained at the end of generation 3 (even if descendants of the unmated cells eventually mated). We then did not consider that lineage any further, so lineages in which cells first mated at generation 2 are not represented in the generation 3 data.

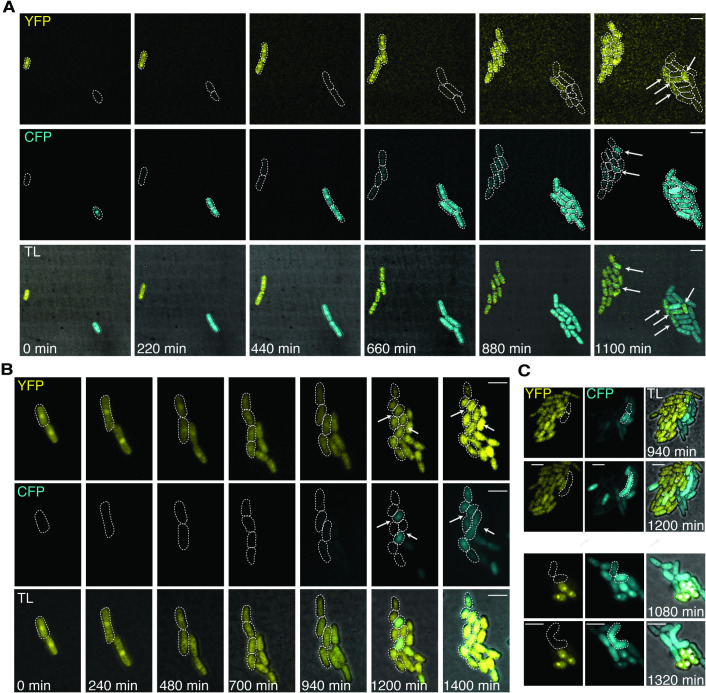

Figure 2. Variation between mating behaviors in Sp and Sk cells.

(A) Schematic showing cell divisions, switching, and mate choice in Sp. Mitotic generations are shown on the left. Cells are either h+ (P) or h- (M) and their status is switchable (s) or unswitchable (u). (B) Division and mating phenotypes of wildtype Sp and Sk cells plated at low cell density (0.25×) on SPA plates. Single founder cells and their descendants were monitored through time-lapse imaging. Mating patterns were categorized until the end of the generation in which the first mating event occurred. The data presented were pooled from two independent time-lapses in which over 400 founder cells were tracked. (C) Division and mating phenotypes of fluorescently labeled Sp and Sk cells plated at standard (1×) density on SPA plates. Individual cells were monitored until the population reached a typical mating efficiency for the specific cross and the mate choice of their progeny and the mitotic generation of those events was classified. The cells labeled with GFP are indicated with a cyan line around the cell whereas the mCherry-labeled cells are outlined in magenta. Pooled data from two independent experiments are presented, with 286 cells scored from each experiment. In the cross of Sp (GFP) and Sk (mCherry), we present an additional plot (far right) in which the fate of each founder is separated by isolate. (D) Inbreeding coefficient calculated from still images of cells plated at 1× density on SPA. *** indicates p-value < 0.005, multiple t-test, Bonferroni corrected. At least three biological replicates per isolate are shown (open shapes). (E) Breakdown of sibling cell mating by fluorophore in the indicated crosses from C. * indicates p-value = 0.04, one-tailed t-test comparing isogenic and mixed Sp cells from two videos.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Mating-type switching dual reporter assay using mating-type-specific promoters in Sp.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Mating-type locus variation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe isolates.

Figure 2—figure supplement 3. Variation in cell division and asci phenotypes in natural isolates.

Figure 2—figure supplement 4. Mating efficiency and asci length of Sp/Sk heterozygotes.

Figure 2—figure supplement 5. Mostly additive phenotypes in crosses between natural isolates.

Figure 2—video 1. Homothallic Sp mating video.

Figure 2—video 2. Homothallic Sk mating video.

Classic work characterizing mating-type switching patterns in Sp found that one in a group of four clonally derived cells will have the opposite mating type relative to the other three cells. A newly switched cell will be compatible to mate with close relatives, most typically its sibling cell (Figure 2A; Miyata and Miyata, 1981). Under the same switching model, a smaller portion of cells derived from a single division could be of opposite mating types and thus sexually compatible. For example, if one considers switchable cells (e.g., Ps in Figure 2A), they must divide only once to generate a pair of mating-competent cells. In Sp cells, we observed mating among the clonal descendants of some progenitor cells after a single mitotic division (i.e., at generation 2). By the third generation, we observed mating among the descendants of more than half of the progenitor cells. Almost all the observed mating events were between sibling cells (Figure 2A and B). These observations are consistent with published work assaying mating patterns within lineages of clonal Sp cells (Bendezú and Martin, 2013; Klar, 1990; Miyata and Miyata, 1981).

Sk cells plated at 0.25× density on SPA divided significantly more than Sp cells prior to the first mating (Wilcox rank sum test; p < 0.005 Figure 2B). Sk progenitor cells most frequently started mating at the fourth mitotic generation (Figure 2B). This phenotype is consistent with less mating-type switching as more generations would be required on average to produce a cell with the opposite mating type (Singh and Klar, 2002). In addition, many mating events were between non-sibling cells. This phenotype can also be explained indirectly by reduced mating-type switching. Specifically, after cells undergo several divisions, they generate non-linear cell clusters in which comparably more non-sibling cells are in close proximity (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A-B). This clustering could lead to more non-sibling mating than when cells are mating-competent after fewer divisions and the low number of cells are largely arranged linearly.

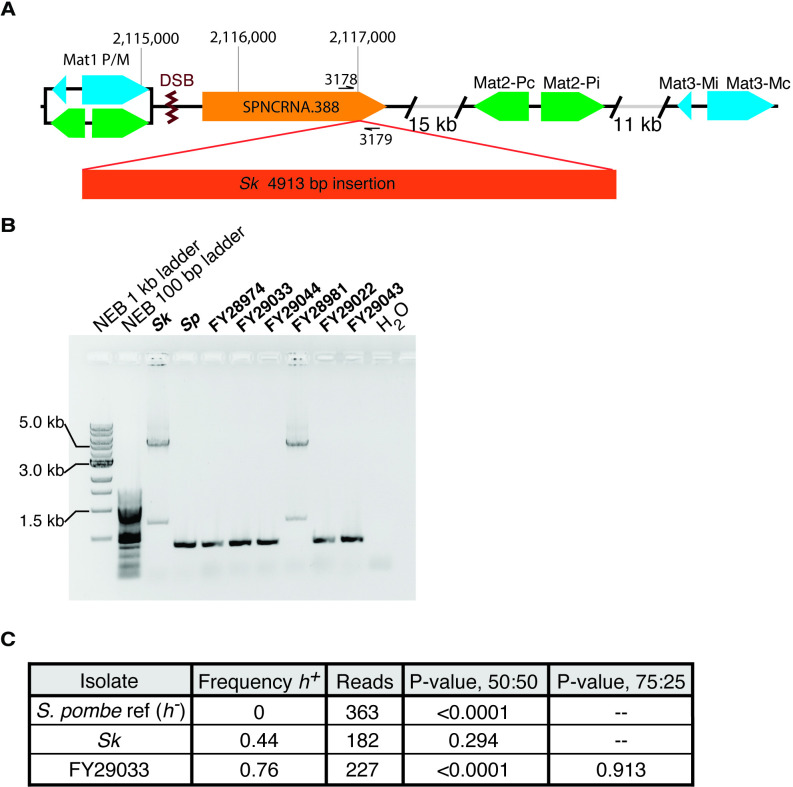

To better understand the differences between Sp and Sk, we compared the sequence of the mating-type locus in the two isolates as many distinct alleles have been identified (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2018). Consistent with previous work, we found that the mating-type regions of Sp and Sk are highly similar (Singh and Klar, 2002). However, using a previously published mate-pair sequencing dataset, we discovered an ~5 kb insertion of nested Tf transposon sequences in the Sk mating-type region (Eickbush et al., 2019). We confirmed the presence of the insertion using PCR (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A-B). We also found evidence consistent with the same insertion in FY28981, which also mates more randomly than Sp (Figure 2—figure supplement 2B, Figure 1D). We did not, however, formally test if the insertion affects mating phenotypes. Even if it does have an effect, it is insufficient to explain all the mating variation we observed as FY29044 mates randomly, yet it lacks the insertion (Figure 1D and Figure 2—figure supplement 2B).

To further explore the hypothesis that decreased mating-type switching efficiency in Sk could contribute to the mating differences we observed (Figure 2B), we carried out time-lapse analyses of cells, at our standard 1× cell mating density. We reasoned that at this density, any given cell is likely to have a cell of opposite mating type nearby, even if mating-type switching is infrequent. We again used mixed populations of GFP- and mCherry-expressing cells to facilitate the scoring of mating patterns (Figure 2C, Figure 2—video 1 supplement 1). We found that the Sp cells predominantly mated in the second and third mitotic generations and most mating events were between sibling cells (Figure 2C).

The mating behavior of Sk cells changed more dramatically between 0.25× density and the higher 1× density. Whereas Sk cells tended to first mate in the fourth generation at 0.25× density, at 1× density Sk cells, like Sp, generally mated in the second and third mitotic generations (Figure 2C, Figure 2—video 2 supplement 2). Additionally, we observed significantly reduced levels of mating between Sk sibling cells at 1× density relative to 0.25× (10% and 56%, respectively; Figure 2E and B). These phenotypes are consistent with reduced mating-type switching in Sk. Specifically, our data suggest that Sk cells do not need to undergo more divisions before they are competent to mate. Rather, the additional divisions that occurred at 0.25× density in Sk could have been necessary to produce a pair of cells with opposite mating types. At 1× density, additional divisions are not expected to be required as additional non-sibling compatible partners are available.

It is important to note, however, that our experiments combined with the previous work showing fewer switching-initiating DSBs in Sk (Singh and Klar, 2002), support, but do not conclusively demonstrate that mating-type switching occurs less frequently in Sk. In particular, our assays to understand switching frequencies use mating as a proxy for switching, which is not ideal. Therefore, reduced switching in Sk represents a promising model that remains to be tested. Still, our results conclusively demonstrate the key point that the mating phenotypes previously measured in Sp do not apply to all S. pombe isolates. Despite very little genetic diversity, S. pombe isolates maintain significant natural variation in key mating phenotypes (Jeffares et al., 2017).

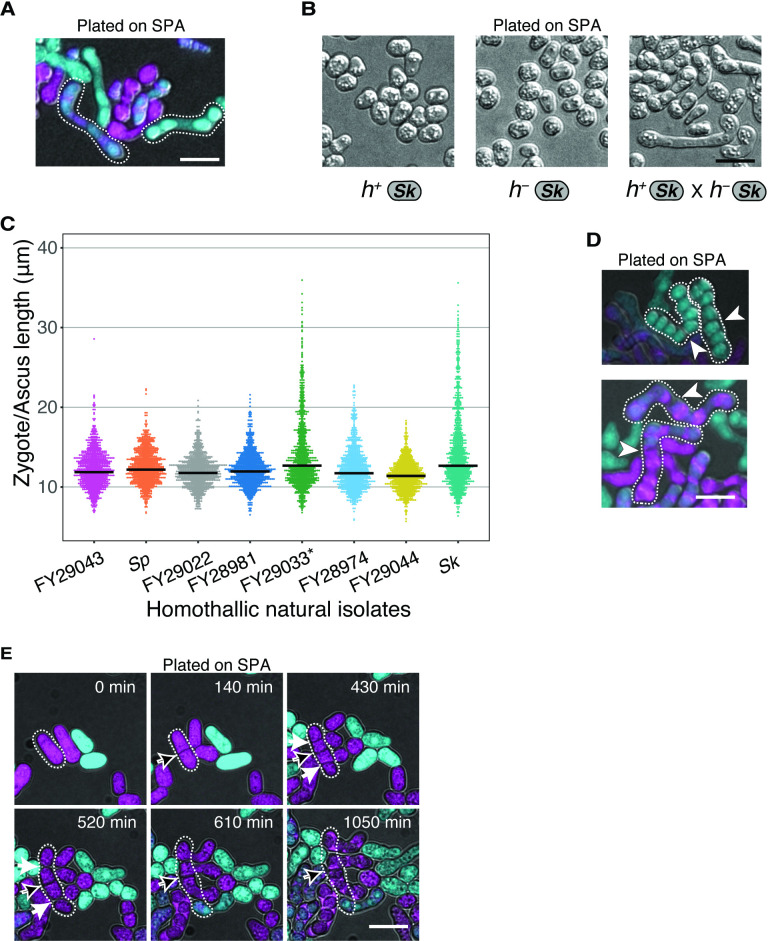

Ascus variation

While assaying inbreeding cytologically, we noticed that the Sk natural isolate displayed tremendous diversity in ascus size and shape (Figure 1C, Figure 2—figure supplement 3A, Figure 2—video 2). This was due to high variability in the size of the mating projections, known as shmoos. Sk produced long shmoos only in response to cells of the opposite mating type and not as a response to nitrogen starvation alone (Figure 2—figure supplement 3B). The long Sk shmoos motivated us to quantify asci length across all the natural isolates described above. We found that most isolates generated zygotes or asci that were ~10–15 μm, similar to Sp. The majority of Sk zygotes and asci also fell within this range, but ~25% of Sk zygotes and asci were longer than 15 μm, with some exceeding 30 μm (Figure 2—figure supplement 3C). We also assayed zygote/ascus length in an additional natural isolate in which we were unable to quantify inbreeding due to a clumping phenotype (FY29033). This isolate also showed populations of long asci, like Sk (Figure 2—figure supplement 3C).

Additionally, we occasionally noticed a fused asci phenotype in Sk (Figure 2—figure supplement 3D). Time-lapse analyses of mating patterns, described above, revealed these fused asci can result from an occasional disconnect between mitotic cycles and the physical separation of cells (Figure 2—figure supplement 3E). This phenotype is reminiscent of adg1, adg2, adg3, and agn1 mutants in Sp that have defects in cell fission (Alonso-Nuñez et al., 2005; Gould and Simanis, 1997; Sipiczki, 2007). Although we observed this phenotype in all time-lapse experiments using Sk cells, the prevalence of this phenotype varied greatly between experiments. We rarely observed this phenotype in Sp cells. We did not analyze time-lapse images of the other natural isolates, where this phenotype is most easily observed, so it is unclear if this septation phenotype occurs in other natural isolates.

Mating phenotypes are affected by available mating partners

We next assayed if the mating preferences of S. pombe isolates Sp and Sk were invariable, or if they could be affected by the available mating partners due to mating incompatibilities (Seike et al., 2019b). To test this idea, we used both still and time-lapse imaging of cells mated at 1× density on SPA. For these experiments, we mixed fluorescently labeled Sp and Sk cells in equal frequencies.

We observed in experiments employing still images that the overall inbreeding coefficient of the mixed Sk/Sp population of cells was intermediate between single-isolate crosses and mixed crosses (Figure 2D). In time-lapse experiments, we observed that Sk cells maintained low levels of mating between sibling cells in the mixed Sk/Sp population (9.2% compared to 9.8% in a homogeneous population; Figure 2E). Among the Sp cells, mating between sibling cells decreased significantly from 56.8% to 29.7% in the mixed mating environment (Figure 2E; t-test, p = 0.04). Together, these results suggest that Sk cells can interfere with the ability of Sp cells to undergo same-clone mating. Although sibling cell mating preference changed, we did not observe a significant decrease in the mating efficiency of Sp cells in a mixed Sp/Sk population relative to a pure Sp population (Figure 2—figure supplement 4A). Instead, the mating efficiency in the mixed Sp/Sk population was intermediate of those observed in pure Sp and Sk populations, indicating these isolates do not affect each other’s ability to mate.

We were intrigued by the idea that long shmoos (mating projections) of Sk could contribute to its ability to disrupt Sp sibling mating. We were unable to address this idea directly. We did, however, find that Sk/Sp matings produce significantly longer zygotes/asci than either Sk/Sk or Sp/Sp matings (Figure 2—figure supplement 4B). This was true even when we compared Sk/Sp zygote/ascus length to the length of heterozygous Sk/Sk or heterozygous Sp/Sp zygotes/asci. While this result does not prove that long Sk shmoos disrupt Sp sibling mating, it does show that long shmoos tend to be used in these outcrossing events.

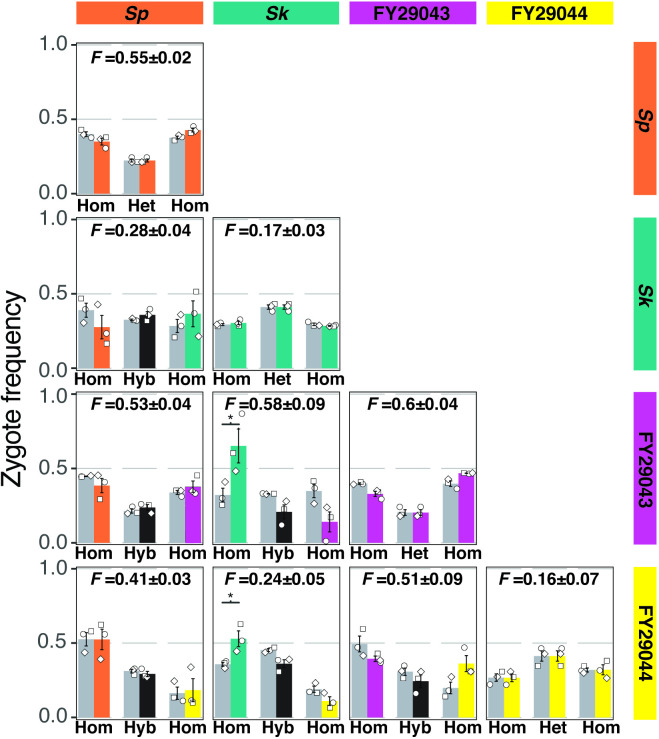

We next extended our analyses by assaying mating efficiency and inbreeding coefficients in all pairwise combinations of Sp, Sk, FY29043, and FY29044 using still images of mated cells. After adjusting for mating efficiencies and parental inbreeding coefficients (see Materials and methods), the phenotypes we observed in these crosses were mostly additive, in that they were intermediate to the pure parental strain phenotypes (Figure 2—figure supplement 5). The two exceptions were in the crosses between Sk and the isolates FY20943 and FY20944. Sk formed more Sk/Sk homozygotes than expected in the two crosses (one-tailed t-test, p = 0.043 and p = 0.038, respectively), suggesting that Sk cells may not be fully sexually compatible with FY20943 and FY20944 (Figure 2—figure supplement 5). However, the magnitude of the effect was small in both cases and the statistical significance is lost after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Overall, our observations indicate that mating phenotypes of a given isolate can be affected by different mating partners. Importantly, however, our results suggest mating incompatibilities are unlikely to have a major role in limiting outcrossing within S. pombe.

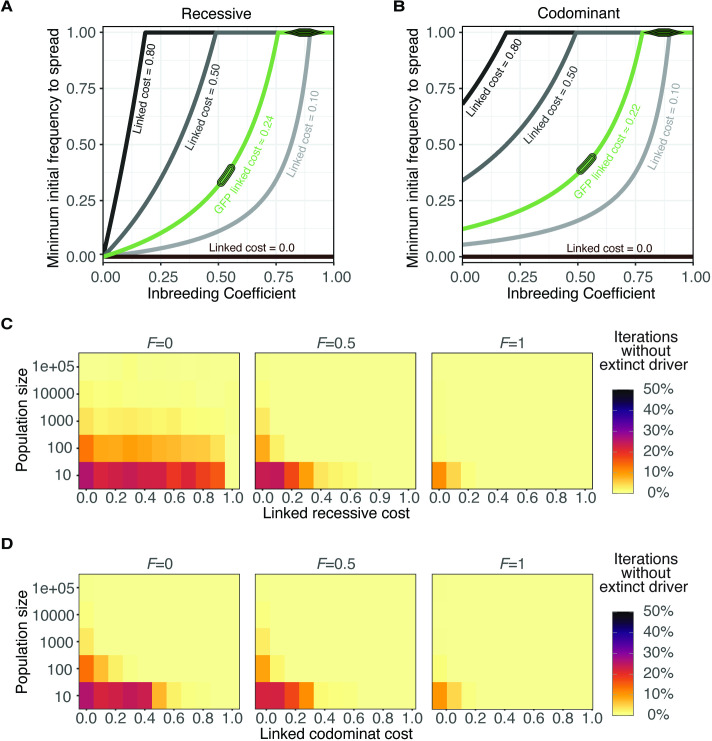

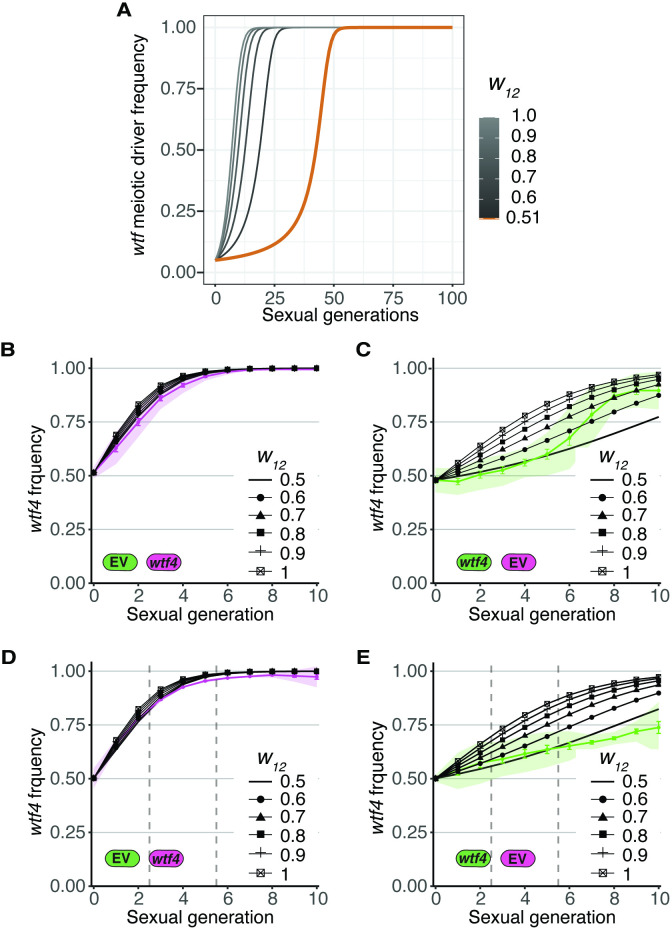

Population genetics modeling of the effect of inbreeding on a wtf meiotic driver

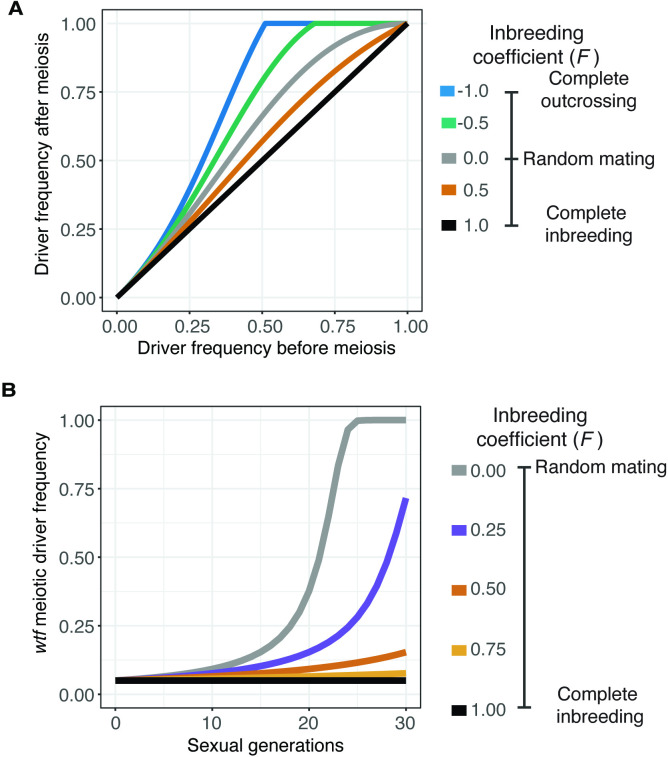

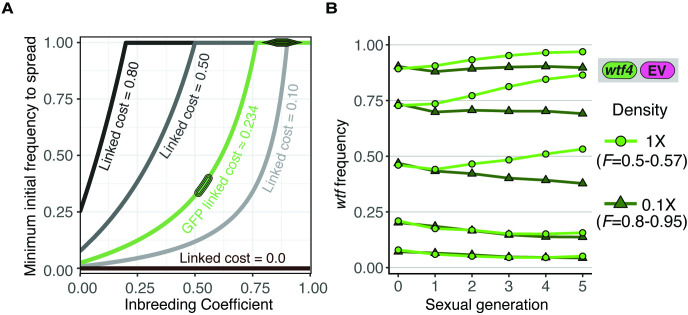

We next wanted to test how the observed range of inbreeding coefficients would affect the spread of a wtf driver in a population. To do this, we first used population genetic modeling. We used the meiotic drive model presented by J Crow, but we also introduced an inbreeding coefficient (Hartl and Clark, 2007; Crow, 1991) (see Materials and methods for a full description of the model). The model considers a population with two possible alleles at the queried locus and no genetic drift. We assumed a wtf driver would exhibit 98% drive (transmission to 98% of spores) in heterozygotes based on measured values for the Sk wtf4 driver (Nuckolls et al., 2017). We assumed that all genotypes have the same fitness during haploid cell growth. For diploid cells induced to produce spores, we assumed homozygotes have a fitness of 1 (e.g., maximal fitness), whereas wtf driver heterozygotes have a fitness of 0.51, since meiotic drive destroys nearly half of the spores (Nuckolls et al., 2017). The inbreeding coefficient dictates the frequency of heterozygotes and thus the frequency at which the wtf driver can act. We varied the inbreeding coefficient (F) from 1 (all matings generate homozygotes) to –1 (all matings generate heterozygotes).

We used the model to calculate the predicted change in the frequency of a wtf driver after only one sexual generation (Figure 3A). We also calculated the spread of a wtf driver in a population from a 5% starting frequency (Figure 3B) and from lower starting frequencies (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A) over generations of sexual reproduction. If we used an inbreeding coefficient of 1, the frequency of the driver does not increase after sexual reproduction or spread in a population over time (Figure 3A and B). No change in driver frequency was expected because no heterozygotes are produced under this condition, so no drive can occur. The wtf driver has the greatest advantage if the inbreeding coefficient is –1, as all matings generate heterozygotes. Under all other conditions, including the range of inbreeding coefficients we measured experimentally in S. pombe natural isolates, some heterozygotes form. The wtf driver thus increases in frequency over generations of sexual reproduction, even when the driver starts at very low (anything greater than 0) frequencies (Figure 3A and B and Figure 3—figure supplement 1A, see Materials and methods) (Crow, 1991). This model predicts that wtf drivers can spread under the modeled conditions if some non-same-clone mating occurs, even if it is infrequent. This observation is consistent with previous theoretical analyses demonstrating that inbreeding can slow the spread of meiotic drivers (Martinossi-Allibert et al., 2021).

Figure 3. Inbreeding is predicted to slow the spread of a wtf driver.

We assumed a 0.98 transmission bias favoring the wtf driver and a fitness of 0.51 in wtf+/wtf- heterozygotes. We assumed that homozygote fitness is 1. We simulated the spread of a wtf driver for 30 generations. (A) Change of wtf meiotic driver frequency after a single meiosis assuming varying levels of inbreeding. (B) The spread of a wtf driver in a population over time assuming varying levels of inbreeding.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Spread of a wtf driver under varying initial frequencies and population sizes.

We next wanted to consider the spread of a wtf driver under conditions in which genetic drift could occur (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B and C). To do this, we simulated populations of different sizes (10–100,000 total individuals) that started with one driver. We followed the population for 1000 generations of mating and spore formation. We randomly selected surviving ‘haploids’ to populate the next generation to keep the population size fixed. We assumed that all genotypes have equal fitness during haploid cell growth. For mathematical simplicity, we assumed complete drive and a corresponding fitness of 0.5 in heterozygous diploids. We again assumed that both types of homozygous diploids had a fitness of 1. We also varied the inbreeding coefficient from 0 (random mating) to 1 (all matings generate homozygotes). Surprisingly, we found that the probability of a driver’s success was related to population size, similar to the recent results of Martinossi-Allibert et al., 2021. Specifically, the driver was most likely to be maintained in the smaller populations and in populations with more random mating due to the driver’s positive effect on its own allele transmission (Figure 3—figure supplement 1C). In larger populations in which the drivers started at a lower initial frequency, the drive allele generally took a long time to increase its frequency compared to the alternate allele, or it was lost due to drift. This was especially true when inbreeding coefficients were high (Figure 3—figure supplement 1C).

Inbreeding and linked deleterious alleles can suppress the spread of wtf drivers

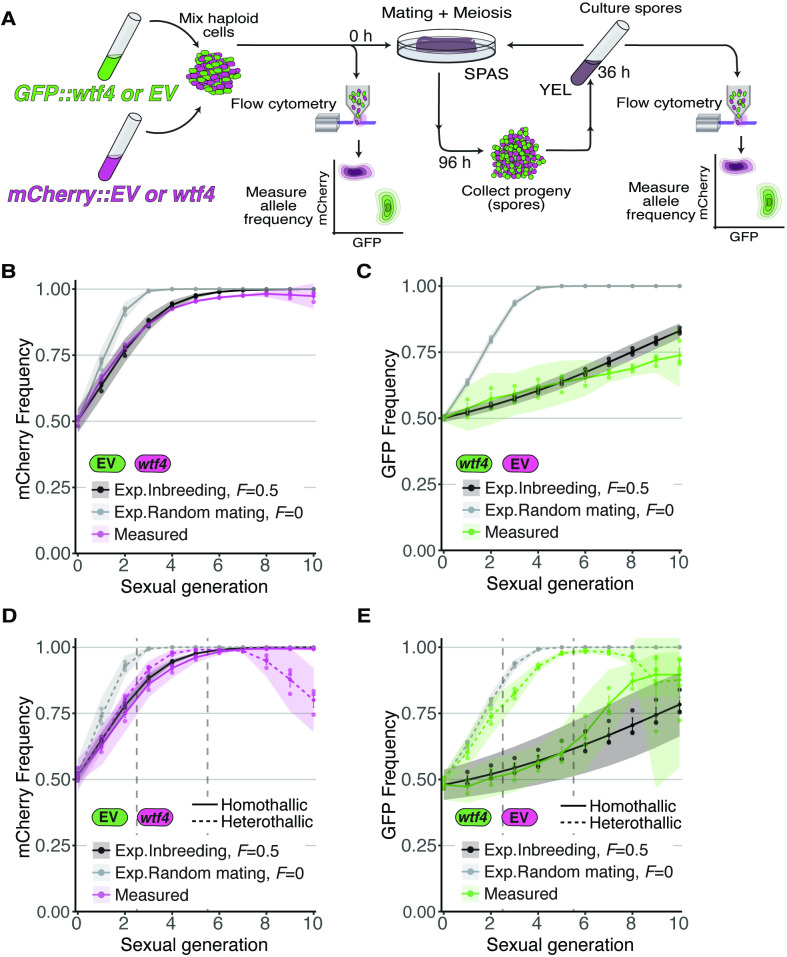

We next wanted to test if our predictions reflect the behavior of wtf drive alleles in a laboratory population of Sp cells over many generations. To do this, we constructed an experimental evolution system employing the GFP and mCherry fluorescent markers described above to measure changes in allele frequencies in a population over time using cytometry. To mark drive alleles, we linked the fluorescent markers with the Sk wtf4 driver and integrated the whole construct at the ura4 locus in Sp (Nuckolls et al., 2017). For non-driving alleles, we used GFP or mCherry integrated at the ura4 locus without a linked wtf gene. We call the non-wtf alleles ‘empty vector’. We started the experimental evolution populations with a defined ratio of GFP- and mCherry-expressing cells. We then induced a subset of the population to mate and sporulate followed by collection and culturing of the progeny (spores). From these cells, we remeasured GFP and mCherry frequencies using flow cytometry, and we initiated the next round of mating and meiosis (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Inbreeding slows the spread of the wtf4 meiotic driver in homothallic strains.

(A) Experimental strategy to monitor allele frequency through multiple generations of sexual reproduction. GFP (green) and mCherry (magenta) markers are used to follow empty vector (EV) alleles or the wtf4 meiotic driver. Starting allele frequencies and allele frequencies after each round of sexual reproduction were monitored using cytometry. (B) Homothallic population with mCherry marking wtf4 and GFP marking an EV allele. Allele dynamics were predicted using drive and fitness parameters described in the text assuming an inbreeding coefficient of 0.5 (black lines) and random mating (inbreeding coefficient of 0; gray lines). The individual spots represent biological replicates and the shaded areas around the lines represent 95% confidence intervals. (C) Same experimental setup as in (B), but with mCherry marking the EV allele and GFP marking wtf4. (D–E) Repeats of the experiments shown in (B) and (C) with two alterations. First, these experiments tracked heterothallic populations (dotted lines) in addition to homothallic cells (solid lines). Second, the populations were sorted by cytometry at generations 3 and 5 (vertical long-dashed lines) to remove non-fluorescent cells.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Loss of fluorescent markers in experimental evolution analyses.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Allele transmission in homozygous control homothallic and heterothallic populations.

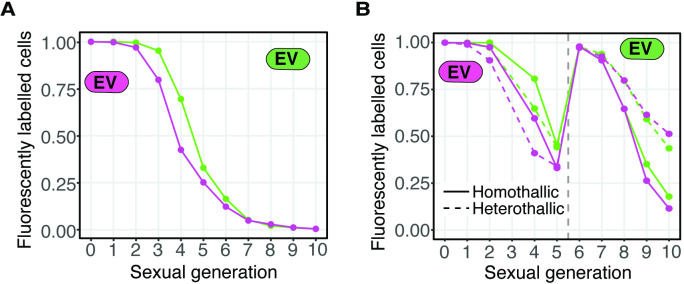

Because our experiments rely on comparing the frequency of GFP- and mCherry-expressing cells over time, we needed to test the relative fitness of the markers. We found that both fluorescent markers were lost from all our experimental populations over time (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A-B). This was likely because insertion of the markers disrupted the ura4 gene and cells that excised the marker reverted the ura4 mutation and thereby gained a fitness benefit. We therefore only considered fluorescent cells for our analyses and stopped the experiments when more than 95% cells lacked a fluorescent marker. In addition, in one set of experiments we also sorted cells at defined timepoints to remove non-fluorescent cells from our populations (Figure 4D–E, Figure 4—figure supplement 1B and Figure 4—figure supplement 2C-D, described below).

To assay for potential differences in the fitness costs of GFP and mCherry markers, we carried out our analyses in two control populations without drive. One control population lacked the Sk wtf4 driver while the other had Sk wtf4 linked to both fluorescent markers. For both types of controls, we analyzed homothallic (inbreeding coefficient ~0.5) and mixed heterothallic (inbreeding coefficient ~0) cell populations (Figure 1D). We found in most cases that the number of mCherry-expressing cells increased at the expense of GFP-expressing cells over time (Figure 4—figure supplement 2A-D). The notable exception was in heterothallic populations containing Sk wtf4 linked to both fluorophore alleles, where we did not observe a different cost of the GFP allele compared to mCherry (Figure 4—figure supplement 2D). The origin of the differential fitness between mCherry and GFP alleles and why this cost was not observed in the one heterothallic population are both unclear. We did not determine the cause of the differences between them.

To allow us to predict expected allele frequencies more accurately, we wanted to obtain a gross estimate of the fitness cost of the GFP-marked alleles relative to the mCherry-marked alleles in our experiments. To do this, we used the first six generations of data from our control crosses (Figure 4—figure supplement 2) to fit a maximum likelihood model in which all parameters were fixed except the fitness values of GFP/mCherry heterozygotes and GFP/GFP homozygotes. We found that the fitness cost of the GFP in homozygotes was 0.234 (see Materials and methods). We found the dominance of the GFP cost was 0.083 (low fitness cost of GFP in GFP/mCherry heterozygotes). We then used these costs, calculated from our controls without meiotic drive, to calculate expected values in our experimental analyses in which drive can occur (Figure 4B–E).

For our experiments competing Sk wtf4 with an empty vector allele, we first assayed populations in which the alleles both started at 50% frequency. In homothallic (inbreeding coefficient ~0.5) populations, we observed that wtf4 alleles spread in the population over several generations of sexual reproduction. The driver spread faster when linked to mCherry than when linked to GFP, presumably due to the aforementioned fitness costs linked to GFP (Figure 4B–C). In both cases, the rate of spread of the allele was very close to our model’s predictions if we assumed an inbreeding coefficient of 0.5 (black lines, Figure 4B–C) and differed considerably from the model’s predictions assuming random mating (inbreeding coefficient = 0; gray lines, Figure 4B–C).

We saw similar spread of wtf4 in homothallic populations in a set of repeat experiments in which we sorted the cell populations twice to remove non-fluorescent cells (Figure 4D and E). In these experiments, we also assayed mixed heterothallic populations with an equal mix of GFP- and mCherry-marked cells from both mating types. As described above, these mixed heterothallic populations show random mating (inbreeding coefficient ~0) between GFP- and mCherry-labeled cells (Figure 1D). In the mixed heterothallic populations, the wtf4 driver spread significantly faster than in homothallic cells. In generations 1–6, the spread of wtf4 was very similar to that predicted by our model if we assumed random mating (inbreeding coefficient = 0). In later generations, our observations did not fit the model well. We suspect extensive loss of fluorescent cells, especially those with mCherry, and the resulting decrease in population size could contribute to this effect (Figure 4D and E; Figure 4—figure supplement 1).

We compared our data to a model in which driver heterozygotes have a fitness of 0.51, but we also considered variants of the model in which heterozygotes have fitness greater than 0.5, as can occur with spore killers in Podospora anserina (Vogan et al., 2021; Martinossi-Allibert et al., 2021). In S. pombe, an increase in driver heterozygote fitness could occur if the driving alleles benefit from drive beyond the benefits gained directly by killing spores bearing the alternate allele. For example, the surviving meiotic products could theoretically gain fitness during spore development by scavenging increased resources from the killed meiotic products (Nauta and Hoekstra, 1993). We found that increasing heterozygote fitness beyond 0.51 decreased the fit of our data to the model (Figure 5—figure supplement 2), suggesting wtf drivers do not gain additional benefits beyond killing spores bearing the alternate allele.

Overall, our results demonstrate that our population genetics model with driver heterozygote fitness at 0.51 is good at describing the spread of wtf4 in our experimental population, particularly in the first few generations. Our results also confirm that inbreeding coefficients near 0.5 slow, but do not stop, the spread of drivers in a population.

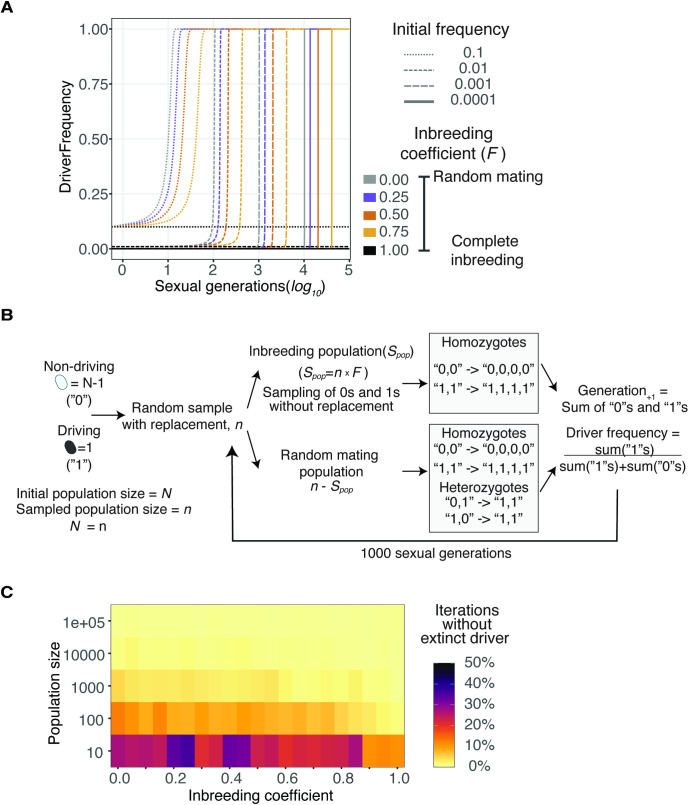

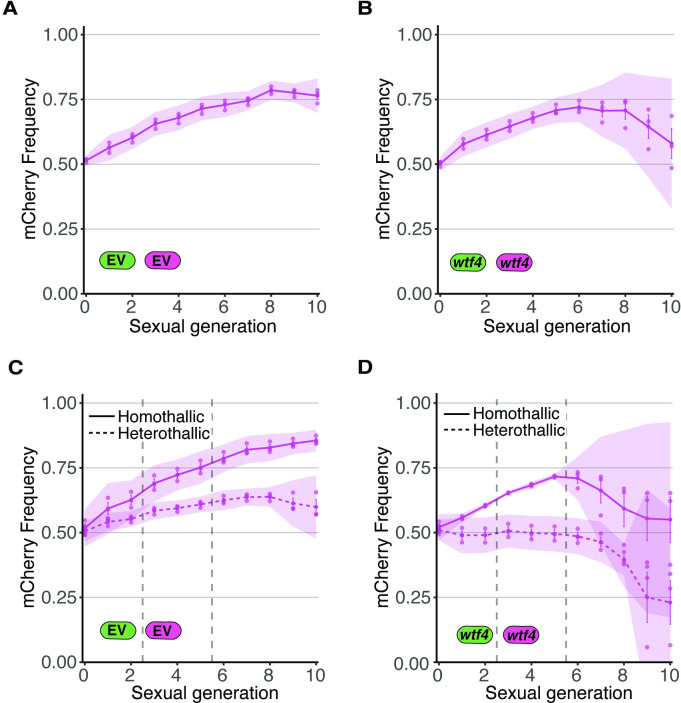

Meiotic drivers tend to accumulate linked deleterious alleles in nature (Atlan et al., 2004; Dyer et al., 2007; Finnegan et al., 2019; Fishman and Saunders, 2008; Higgins et al., 2018; Lyon, 2003; Olds-Clarke, 1997; Schimenti et al., 2005; Unckless et al., 2015; Wilkinson and Fry, 2001; Wu, 1983). While the linkage of individual drivers to deleterious alleles in S. pombe has not been extensively investigated, driving alleles in the Sk isolate are linked to a chromosomal translocation that decreases fitness in heterozygotes (Zanders et al., 2014). Similar chromosomal rearrangements involving chromosome 3, which houses most wtf genes, are common in S. pombe, so it is likely drivers are frequently linked to rearrangements (Bowen et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2011; Avelar et al., 2013). We therefore used the population genetic model to calculate the ability of a driver to spread when tightly linked to alleles with fitness costs ranging from 0 to 0.8. We also varied the inbreeding coefficient from 0 (random mating) to 1 (no heterozygotes are produced).

We found that, in the absence of additional linked costs, wtf drivers are predicted to spread in a population at all initial frequencies greater than 0 (Figure 5A). As described above, this spread is slowed by inbreeding, but is not stopped until inbreeding coefficients reach 1 (no heterozygotes are produced). When the driver is burdened by additional fitness costs, it can still spread in a population. Importantly, however, as the fitness costs of linked deleterious alleles increase, the driver must start at a higher initial frequency to spread. If the fitness costs are recessive or close to recessive (dominance coefficient h near 0), a driver can invade at low frequencies in a randomly mating population, but a driver would require a higher initial frequency to spread in an inbreeding population (inbreeding coefficients > 0; Figure 5A, Figure 5—figure supplement 1A). If the fitness costs are partially dominant (50% dominance), the drivers require a higher initial frequency to spread, even with random mating (Figure 5—figure supplement 1B).

Figure 5. Inbreeding purges wtf drivers with linked deleterious alleles.

(A) Modeling the predicted impacts of inbreeding, the fitness of the driving haplotype, and the initial frequency of the driver on the spread of a wtf driver linked to a deleterious allele with low dominance (h = 0.083) in a population. The circle indicates the predicted initial frequency necessary for the GFP:wtf4+ allele to spread in a population when mated at standard (1×) density where F = 0.5. The diamond indicates the predicted initial frequency necessary for the GFP:wtf4+ allele to spread in a population when mated at low (0.1×) density where F = 0.8–0.95 measured in Figure 1—figure supplement 2C. (B) Experimental analyses of the impacts of inbreeding and the initial driver frequency on the spread of the GFP:wtf4+ allele in a population. A single biological replicate was used for each initial frequency and inbreeding condition.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Evolution of wtf meiotic drivers in populations for recessive and codominant costs.

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. Assessing if wtf+ spores gain fitness as a result of spore killing.

In finite populations in which drift can occur, we also observed that linked costs could limit the maintenance of a driver particularly in populations that inbreed (inbreeding coefficients > 0; Figure 5—figure supplement 1C,D). This is in line with previous modeling and can be explained because the cost of the deleterious allele is fixed, but the benefit a driver gains from drive is frequency dependent (Drury et al., 2017; Martinossi-Allibert et al., 2021; Nauta and Hoekstra, 1993).

We next tested these predictions experimentally using the Sk wtf4 allele linked to GFP in homothallic cells. As described above, the GFP allele is linked to an unknown deleterious trait (estimated 1.9% and 23.4% cost in heterozygotes and homozygotes, respectively). We varied the inbreeding coefficients of the populations by assaying cells mated at 1× and 0.1× density. As reported above, homothallic cells mated at 1× density exhibit an inbreeding coefficient of 0.5–0.57, but that is increased to 0.8–0.95 by mating the cells at low (0.1×) density (Figure 1D, Figure 1—figure supplement 2B and C ). Consistent with the predictions of our model, we observed in the experimental populations that the driver failed to spread when the initial frequency was less than 0.25 (Figure 5B). When the wtf4:GFP allele was found in roughly half of the population, it could spread when the inbreeding coefficient was low but decreased in frequency when the inbreeding coefficient was increased (Figure 5B). Similar, but less dramatic, effects were observed at higher initial frequencies of the wtf4:GFP allele. Altogether, our experimental analyses are consistent with the predictions of our model and show that both inbreeding and linked deleterious alleles can impede the spread of a wtf meiotic driver.

Discussion

Natural variation in mating phenotypes in S. pombe

Mating phenotypes, particularly the outcrossing rate, are key parameters that affect the evolution of species (Muller, 1932; Otto and Lenormand, 2002). We sought to explore mating phenotypes in S. pombe to better understand the evolution of the wtf gene family found in this species. Although genetic variation within S. pombe is limited, past studies found variation in mating efficiency and uncovered genetic diversity of the mating-type locus (Jeffares et al., 2015; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2018; Rhind et al., 2011; Singh and Klar, 2002). In this work, we assayed mating in an array of homothallic S. pombe natural isolates under a variety of laboratory conditions. Similar to previous work, we found Sp mating efficiency close to 40% and observed variable mating efficiencies for natural isolates (Merlini et al., 2016; Seike et al., 2019a). In addition, we quantified the propensity of natural isolates to undergo same-clone mating when given the opportunity to mate with non-clonally related cells. We found this trait, as measured using an inbreeding coefficient, was variable between natural isolates and could be affected by cell density or available sexual partners.

All of the S. pombe natural isolates we studied are homothallic and thus capable of same-clone mating. Despite this, we found that all isolates underwent some non-same-clone mating. In addition, some isolates, like Sk, showed considerable non-same-clone mating (inbreeding coefficient near 0) under standard mating conditions. This provides additional data supporting homothallism is compatible with outcrossing between non-clonally related isolates (Attanayake et al., 2014). In addition, S. pombe asci undergo a programmed degeneration process (endolysis) shortly after spore formation (Encinar del Dedo et al., 2009). This presumably frees spores to potentially distribute (in wind, water, or associated with animals) separate from the other spores produced in the same meiosis. The physical independence of S. pombe spores could also facilitate outcrossing in this homothallic fungus (Billiard et al., 2012).

We did not definitively identify the molecular mechanisms underlying the variation in mating phenotypes we observed. Our data is, however, consistent with a model in which less frequent mating-type switching in the Sk isolate contributes to more random mating in Sk than in the common lab isolate, Sp. Specifically, if switching is less frequent in Sk, sibling cells are less likely to be compatible to mate. Incompatibility of sibling cells opens the possibility for mating with other, perhaps non-clonally derived, cells in the population. Singh and Klar were the first to propose that Sk switched less frequently than Sp when they noticed less of the DNA break that initiates switching (Singh and Klar, 2002). We discovered a large, nested insertion of transposon sequences in the mating-type locus of Sk, and we posit that this insertion could contribute to reduced DNA break formation and, potentially, decreased mating-type switching. It is important to note, however, that not all strains that mate randomly share this transposon insertion. We also stress that, as in previous work (e.g., Miyata and Miyata, 1981), we did not directly assay switching rates and instead used mating events to infer information about switching. The long shmoos we observed in Sk may also contribute to more random mating in this isolate, as the long shmoo may increase the available number of partners within range.

Additional previously described natural variation that we did not functionally explore may also contribute to differences in inbreeding propensity in S. pombe. For example, heterothallic natural isolates are predicted to exclusively undergo non-same-clone mating with cells of the opposite mating type (Jeffares et al., 2015; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2018). In addition, homothallic isolates with atypical mating-type loci with extra copies of the mat cassettes could grow into populations that are biased toward one mating type (Nieuwenhuis and Immler, 2016). Indeed, we analyzed the presumably expressed mating-type locus (mat1) in several isolates for which we had nanopore sequencing data and found an approximate 3:1 excess of the h+ allele in FY29033 (Figure 2—figure supplement 2C). The excess of one mating type is predicted to also facilitate non-same-clone mating.

It is important to note that our study does not address the actual frequency of outcrossing in S. pombe populations in the wild. Very little is known about the ecology of fission yeast, including how frequently genetically distinct isolates are found in close enough proximity to mate (e.g., closer than ~40 µm apart) (Jeffares, 2018). Outcrossing rates have been estimated using genomic data, but those estimates generally assume both that heterozygous recombination rates will match those observed in pure Sp and that allele transmission is Mendelian (Farlow et al., 2015; Tusso et al., 2019). Although these genomic estimates are reasonable, neither of these assumptions is consistent with empirical analyses (Bravo Núñez et al., 2020b; Hu et al., 2017; Zanders et al., 2014). These assumptions have, therefore, likely led to an underestimation of the true outcrossing rate.

The effect of mating-type phenotypes on the spread of wtf meiotic drivers

To understand the evolution of the wtf drive genes, it is not necessarily essential to understand how frequently significantly diverged natural isolates, like those assayed in this work, mate. Instead, it is important to understand how often a driver is found in a heterozygous state. We suspect that heterozygosity for wtf drivers does not absolutely require outcrossing between more distantly related strains. This is because the wtf gene family, particularly the genes involved in meiotic drive, exhibit extremely rapid evolution. Even though genetic diversity within S. pombe is low (<1% average DNA sequence divergence in non-repetitive regions), the wtf genes present in different isolates tend to be largely distinct (Eickbush et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2017; Jeffares et al., 2015; Rhind et al., 2011). The number of wtf genes per isolate varies from 25 to 38 wtf genes (including pseudogenes), and even genes found at the same locus can be dramatically different (e.g., <61% coding sequence identity between alleles of wtf24) (Eickbush et al., 2019). For example, wtf22 is a predicted pseudogene in one strain, a predicted antidote in another strain, and is predicted to encode distinct drivers (i.e., mutually killing) in two more strains. There is only one wtf locus where all four strains that were surveyed each contain a meiotic driver, wtf4 (Eickbush et al., 2019). Still, we do not consider this a fixed driver because the sequence of wtf4 is different in each strain, which, in all cases tested, leads to a distinct drive phenotype (Bravo Núñez et al., 2018; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020b; Eickbush et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2017). For example, because Sk wtf4 and Sp wtf4 have different sequences, the antidote of Sk wtf4 does not neutralize Sp wtf4 and vice versa (Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a). The rapid evolution of wtf genes is driven largely by non-allelic gene conversion within the family and expansion or contraction of repetitive sequences within the coding sequences of the genes (Eickbush et al., 2019).

Because wtf genes generally provide no protection against wtf drivers with distinct sequences, the variation in wtf gene sequences has profound consequences (Bravo Núñez et al., 2018; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a; Hu et al., 2017). Even small sequence changes in wtf drivers can cause the birth and death of drivers. When a cell bearing a novel wtf driver mutation mates with a cell without the mutation, the driver is heterozygous, and thus, drive can occur and the novel allele can potentially spread through the otherwise largely homogeneous population. Given fission yeast cells have no inherent mobility, the novel drive alleles could arise within small isolated subpopulations (demes) in which drivers have an increased possibility of establishing, as was formally described by Martinossi-Allibert et al., 2021.

Previous work assayed the strength of drive and the associated fitness reduction due to heterozygous wtf drivers (Bravo Núñez et al., 2018; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a; Hu et al., 2017; Nuckolls et al., 2017). Those data, along with the inbreeding coefficients measured in this study, allowed us to mathematically model the spread of a wtf meiotic driver in an S. pombe population. Our modeling showed that the inbreeding coefficients we observed in S. pombe could slow the spread of a wtf driver. In the absence of drift, however, even the highest inbreeding coefficients we observed in S. pombe do not halt the spread of a driver, except in cases where the driver is found in low frequencies and linked to a deleterious allele. Given the tractability of S. pombe, we were also able to test the predictions of the model experimentally. Overall, our experimental results were quite similar to the model’s predictions discussed above. This suggests that our model encompasses all critical parameters. In addition, our experiments show how the wtf drivers can persist and spread in S. pombe, even if outcrossing is infrequent. The variation of mating phenotypes also indicates that the rate of spread of a wtf driver is expected to vary between different populations of S. pombe.

Overall, our results are consistent with previous empirical and modeling studies of meiotic driver dynamics in populations. For example, like our fortuitously deleterious GFP allele, meiotic drivers are often linked to deleterious alleles that can hitchhike with the driver (Atlan et al., 2004; Dyer et al., 2007; Finnegan et al., 2019; Fishman and Saunders, 2008; Higgins et al., 2018; Lyon, 2003; Olds-Clarke, 1997; Schimenti et al., 2005; Unckless et al., 2015; Wilkinson and Fry, 2001; Wu, 1983). The added costs reduce the spread of drivers, which can lead a population to harbor a driver at stable intermediate frequency (Dyer and Hall, 2019; Finnegan et al., 2019; Fishman and Kelly, 2015; Hall and Dawe, 2018; Manser et al., 2011). Additionally, inbreeding can be selected as it increases fitness in a population when a driver is recessive lethal (cost ~1, h = 0), such as in synthetic drive systems (Bull, 2016).

S. pombe as a tool to experimentally model complex drive dynamics

To conclude, we would like to highlight the potential usefulness of the S. pombe experimental evolution approach developed for this study. With this system, we were able to observe the effects of altering allele frequencies, inbreeding rate, and fitness of a driving haplotype. In the future, this system could be used to experimentally explore additional questions about drive systems. For example, one could experimentally model meiotic drivers that bias sex ratios by linking the driver to the mating-type locus in a heterothallic population. In addition, one could explore the evolution of complex multi-locus drive systems employing combinations of multiple wtf meiotic drivers or drivers and suppressors. This tool could lead to novel insights about natural drivers, but it may also be particularly useful for exploring potential evolutionary trajectories of artificial gene drive systems (Burt and Crisanti, 2018; Drury et al., 2017; Price et al., 2020; Wedell et al., 2019).

Materials and methods

Generation of Ura4-integrating vectors and fluorescent strains

We introduced the fluorescent genetic markers into the genome using plasmids that integrated at the ura4 locus. To generate the integrating plasmids, we first ordered gBlocks from IDT (Coralville, IA) that contained mCherry or GFP under the control of a TEF promoter and ADH1 terminator (Hailey et al., 2002; Sheff and Thorn, 2004). We digested the gBlocks with SpeI and ligated the GFP cassette into the SpeI site of pSZB331 and the mCherry cassette into the SpeI site of pSEZB332 (alternate clone of pSZB331; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020b) to generate pSZB437 and pSZB882, respectively. We then linearized the plasmids with KpnI and transformed them into S. pombe using the standard lithium acetate protocol (Schiestl and Gietz, 1989). We independently transformed the isolates GP50 (S. pombe), S. kambucha, FY28974, FY28981, FY29022, FY29033, FY29043, and FY29044. We were unsuccessful in transforming FY28969, FY29048, and FY29068. FY29033 was not included in the inbreeding analyses due to its proclivity to clump. The homothallic and heterothallic strains carrying mCherry or GFP were transformed using the same method.

To add Sk wtf4 to the Sp genome, we again used a ura4-integrating plasmid. To generate this plasmid, we amplified Sk wtf4 from SZY13 using the oligos 688 and 686. We digested the amplicon with SacI and ligated into the SacI site of pSZB332 to generate pSZB716 (Bravo Núñez et al., 2020a; Bravo Núñez et al., 2020b). We then separately introduced the GFP and mCherry gBlocks into the SpeI site of pSZB716 to generate pSZB904 and pSZB909, respectively. We introduced the resulting plasmids into yeast as described above.

Crosses

We performed crosses using standard approaches (Smith, 2009). We cultured each haploid parent to saturation in 3 mL YEL (0.5% yeast extract, 3% dextrose, and 250 mg/L adenine, histidine, leucine, lysine, and uracil) for 24 hr at 32°C. We then mixed an equal volume of each parent (700 μL each for individual homothallic strain, 350 μL for heterothallic parents), pelleted and resuspended in an equal volume of ddH2O (1.4 mL total), then plated 200 μL on SPA (1% glucose, 7.3 mM KH2PO4, vitamins, and agar) for microscopy experiments or SPAS (SPA +45 mg/L adenine, histidine, leucine, lysine, and uracil) for genetics experiments. We incubated the plates at 25°C for 1–4 days, depending on the experiment (see figure legends for exact timing). When we genotyped spore progeny, we scraped cells off of the plates and isolated spores after treatment with B-Glucuronidase (Sigma) and ethanol as described in Smith, 2009.

Iodine staining

We grew haploid isolates to saturation in 3 mL YEL overnight at 32°C. We washed the cells once with ddH2O then resuspended them in an equal volume ddH2O. We then spotted 10 μL of each strain onto an SPAS plate, which we then incubated at 25°C for 4 days prior to staining with iodine (VWR iodine crystals) vapor (Forsburg and Rhind, 2006).

Mating-type locus assembly and PCR

We used mate-pair Illumina sequencing reads to assemble the mating-type locus of S. kambucha with previously published data (Eickbush et al., 2019). We assembled the mating-type locus using Geneious Prime software (https://www.geneious.com; last accessed March 18, 2019) using an analogous approach to that described to assemble wtf loci (Eickbush et al., 2019).

DNA extraction for nanopore sequencing

To extract DNA for nanopore sequencing, we used a modified version of a previously developed protocol (Jain et al., 2018). We pelleted 50 mL of a saturated culture and proceeded as described, with the addition of 0.5 mg/mL zymolyase to the TLB buffer immediately prior to use.

Nanopore sequencing and assembly

We used a MinION instrument and R9 MinION flow cells for sequencing. For library preparation, we used the standard ligation sequencing prep (SQK-LSK109), including end repair using the NEB End Prep Enzyme, FFPE prep using the NEB FFPE DNA repair mix, and ligation using NEB Quick Ligase. We did not barcode samples and thus used each flow cell for a single genome. We used guppy v2.1.3 for base calling. We removed sequencing adapters from the reads using porechop v0.2.2 and then filtered the reads using filtlong v0.2.0 to keep the 100× longest reads. We then error corrected those reads, trimmed the reads and de novo assembled them using canu v1.8 and the ovl overlapper with a predicted genome size of 13 mb and a corrected error rate of 0.12 (Koren S et al., 2017). Base called reads are available as fastq files at the SRA under project accession number PRJNA732453.

In order to count allele frequency within the active mat locus, we mapped raw reads back to the corresponding de novo assembly using graphmap v0.5.2 and processed using samtools v1.12 (Li et al., 2009; Sović et al., 2016). We then visually observed the reference-based assemblies using IGV v2.3.97 to count the number of h + and h- alleles present at the active mating type locus with anchors to unique sequence outside the mat locus (Robinson et al., 2011).

Measuring inbreeding coefficients by microscopy

We mixed haploid parents (a GFP- and an mCherry-expressing strain) in equal proportions on SPA as described above. We then left the plate to dry for 30 min and then took a punch of agar from the plate using a 1271E Arch Punch (General Tools, Amazon). We then inverted the punch of agar into a 35 mm glass bottomed dish (No 1.5 MatTek Corporation). We used this sample to count the initial frequency of the two parental types. We then imaged a second punch of agar taken from the same SPA plate after 24 hr incubation at 25°C for homothallic cells and 48 hr for heterothallic cells. Each biological replicate was constituted by a separate cross.

To image the cells, we used an AXIO Observer.Z1 (Zeiss) widefield microscope with a 40× C-Apochromat (1.2 NA) water-immersion objective. We excited mCherry using a 530–585 nm bandpass filter which was reflected off an FT 600 dichroic filter into the objective and collected emission using a long-pass 615 nm filter. To excite GFP, we used a 440–470 nm bandpass filter, reflected the beam off an FT 495 nm dichroic filter into the objective and collected emission using a 525–550 nm bandpass filter. We collected emission onto a Hamamatsu ORCA Flash 4.0 using µManager software. We imaged at least three different fields for each sample as each technical replicate.

We used cell shape to identify mated cells (zygotes and asci) and used fluorescence to identify the genotype of each haploid parent. To measure both fluorescence and the length of asci, we used Fiji (https://imagej.net/Fiji) software to hand-draw five pixel-width lines through the length of each zygote or ascus. After subtracting background using a rolling ball background subtraction with width 50 pixels, we then measured the average intensity for the GFP and mCherry channels. When measuring the log10 ratio of GFP over mCherry, the mCherry homozygotes have the lowest ratio, homozygotes for GFP the highest ratio, and heterozygotes intermediate.

To calculate the inbreeding coefficient, we used the formula F = 1 − (observed heterozygotes/expected heterozygotes). We used Hardy-Weinberg expectations to calculate the expected frequency of heterozygotes (2p(1p)) for each sample, where ‘p’ is the fraction of mCherry+ cells and (1-p) is the fraction of GFP+ cells measured prior to mating (Hartl and Clark, 2007).

Visualizing mating and meiosis using time-lapse microscopy

For time-lapse imaging of cells mated at 1× density (Figure 2C), we prepared cells using the agar punch method described above. For cells at 0.25× density (Figure 2B), we used the same approach, except we cultured cells in 3 mL EMM (14.7 mM C8H5KO4, 15.5 mM Na2HPO4, 93.5 mM NH4Cl, 2% w/v glucose, salts, vitamins, minerals) then washed three times with PM-N (8 mM NA2HPO4, 1% glucose, EMM2 salts, vitamins, and minerals) before plating cells to SPA. While imaging the cells, we added a moistened kimwipe to the MatTek dish to maintain humidity. We sealed the dish lids on with high-vacuum grease (Corning). We imaged cells using either a Ti Eclipse (Nikon) coupled to a CSU W1 Spinning Disk (Yokagawa), or a Ti2 (Nikon) widefield using the 60× oil immersion objective (NA 1.45), acquiring images every ten minutes for 24–48 hr, using a 5 × 5 grid pattern with 10% overlap between fields. The Ti Eclipse was used for one replicate each of the 1× crosses and the Ti2 was used for all remaining experiments. We used an Okolab stage top incubator to maintain the temperature at 25°C. For the Ti2 (widefield) data we excited GFP through a 470/24 nm excitation filter and collected through an ET515/30 m emission filter. For mCherry on this system, we excited through a 550/15 nm excitation filter and collected through an ET595/40 m emission filter. For the Ti Eclipse (confocal) data, we excited GFP with a 488 nm laser and collected its emission through an ET525/36 m emission filter. For mCherry on this system, we excited with a 561 nm laser and collected through an ET605/70 m emission filter.

To monitor mating in 1× crosses (Figure 2C-E), we recorded the number of divisions and mating choice of the progeny of 286 cells until an expected mating efficiency for the population being filmed was attained. The expected mating efficiency was calculated from still images of the same crosses. We recorded two videos of each cross.

To monitor the number of divisions required before mating could occur in 0.25× cultures (Figure 2B), around 200 individual cells were monitored through the duration of the generation in which the first mating event occurred. If cells failed to mate, they were monitored throughout the duration of the movie. If a cell or its mitotic offspring interacted with a neighboring cell cluster, it was not included in the analysis. We recorded two videos for each isolate.

Calculation of mating efficiency

We calculated mating efficiency from microscopic images using the following formula: