Highlights

-

•

In average risk patients, positive stool-test denotes more CRC risk vs screening COL.

-

•

Patient costs may deter follow-up COL participation after a positive stool-test.

-

•

Estimated LYG from follow-up COL are 3× higher vs screening COL.

-

•

4x more CRC cases and 2× more CRC deaths averted by follow-up vs screening COL.

-

•

Coverage policies should be revised to remove cost barriers for follow-up COL.

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; CRC-AIM, Colorectal Cancer and Adenoma Incidence and Mortality Microsimulation Model; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; LYG, life-years gained; mt-sDNA, multitarget stool DNA

Keywords: Adenoma, Colorectal cancer, Colonoscopy, Life-years gained, Screening, Simulation model, Stool-based test

Abstract

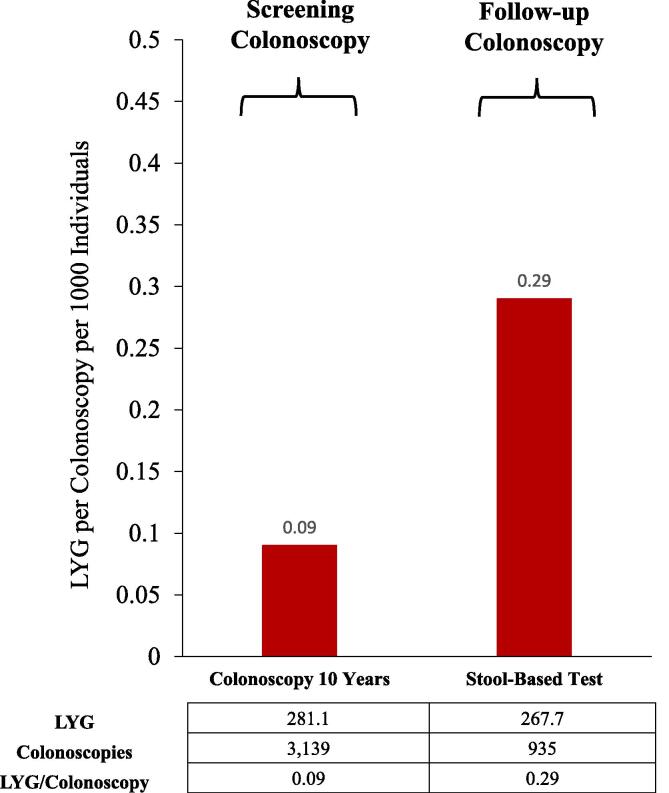

Screening colonoscopies for colorectal cancer (CRC) are typically covered without patient cost-sharing, whereas follow-up colonoscopies for positive stool-based screening tests often incur patient costs. The objective of this analysis was to estimate and compare the life-years gained (LYG) per average-risk screening colonoscopy and follow-up colonoscopy after a positive stool-based test to better inform CRC coverage policy and reimbursement decisions. CRC outcomes from screening and follow-up colonoscopies versus no screening were estimated using CRC-AIM in a simulated population of average-risk individuals screened between ages 45–75 years. The LYG/colonoscopy per 1000 individuals was 0.09 for screening colonoscopy and 0.29 for follow-up colonoscopy. 0.01 and 0.04 CRC cases and 0.01 and 0.02 CRC deaths were averted per screening and follow-up colonoscopies, respectively. Coverage policies should be revised to encourage individuals to complete recommended screening processes.

1. Introduction

The ability of screening to decrease colorectal cancer (CRC) morbidity and mortality is well established. The Affordable Care Act requires that several CRC screening modalities, including colonoscopy and non-invasive stool-based tests (e.g., multitarget stool DNA [mt-sDNA] or fecal immunochemical test [FIT]) be covered with no consumer cost-sharing for average-risk age-eligible individuals. However, cost barriers remain for some individuals with an initial positive stool-based test that requires a follow-up colonoscopy to complete the CRC screening process. Coverage policies that impose this type of financial disincentive may deter CRC screening participation (Fendrick et al., 2021b). The objective of this analysis was to estimate and compare the life-years gained (LYG) per average-risk screening colonoscopy and follow-up colonoscopy after a positive stool-based test to better inform CRC coverage policy and reimbursement decisions.

2. Methods

The Colorectal Cancer and Adenoma Incidence and Mortality Microsimulation Model (CRC-AIM) was used to estimate outcomes resulting from (a) screening colonoscopy and (b) follow-up colonoscopy after an initial positive stool-based test. CRC-AIM simulates the natural history of adenomas to carcinoma and incorporates features of available CRC screening strategies (e.g. screening interval, adherence, test sensitivity, test specificity, and complications). Details of the CRC-AIM model, including validation and the natural history and screening component assumptions, have been reported previously (Piscitello et al., 2020, Description and Validation of the Colorectal Cancer, 2020).

Screening colonoscopy every 10 years, triennial mt-sDNA, and annual FIT screening strategies (including follow-up colonoscopy after a positive stool-based test and surveillance colonoscopies) were simulated for average-risk individuals free of diagnosed CRC at age 40 and screened between ages 45–75 years, in accordance with national guidelines (Davidson et al., 2021, Wolf et al., 2018, Shaukat et al., 2021). Predicted LYG, CRC cases, and CRC deaths per 1000 individuals were compared with no screening. The overall stool-based test LYG/colonoscopy ratio was calculated using the weighted average of the LYG and number of colonoscopies with mt-sDNA and FIT, scaled by their estimated use in the US general population as indicated by 2018 National Health Interview Survey data (Cancer trends progress report, 2020). Sensitivity analyses examined simulated unscreened and previously screened (by colonoscopy or stool test beginning at age 45 years) Medicare populations (ages 65–75 years).

3. Results

The LYG/colonoscopy per 1000 individuals was 0.09 for screening colonoscopy and 0.29 for follow-up colonoscopy (Fig. 1). The number of CRC cases averted/colonoscopy was 0.01 for screening colonoscopy and 0.04 for follow-up colonoscopy. The number of CRC deaths averted/colonoscopy was 0.01 for screening colonoscopy and 0.02 for follow-up colonoscopy.

Fig. 1.

Predicted life-years-gained (LYG) per screening colonoscopy or follow-up colonoscopy for positive stool-based tests in individuals screened from ages 45–75. Data are per 1000 individuals.

In sensitivity analyses of Medicare-age beneficiaries, the estimated LYG/colonoscopy for follow-up colonoscopy was approximately 3- to 4-fold higher than for screening colonoscopy (0.38 vs 0.13 LYG/colonoscopy unscreened; 0.17 vs 0.04 LYG/colonoscopy previously screened).

4. Discussion

Colonoscopy is an essential tool in the effort to reduce CRC burden. Unfortunately, many Americans face cost-sharing for a clinically indicated colonoscopy following a positive stool-based test, which may deter use of this potentially life-saving intervention (Fendrick et al., 2021b). The estimated LYG/colonoscopy was approximately 3-fold higher for procedures performed in follow-up of a positive stool-based screening test when compared with screening colonoscopy. Similarly, an estimated 4-fold more CRC cases and 2-fold more CRC deaths were averted with the follow-up colonoscopy than the screening colonoscopy. As non-invasive CRC screening modalities are preferred by some patients, and their use has increased because of the COVID-19 pandemic, coverage policies should be revised to encourage – not dissuade – individuals to complete the screening process as recommended (Davidson et al., 2021).

These analyses intentionally assumed 100% adherence to all screening colonoscopies and stool-tests to demonstrate that even in an ideal setting of perfect adherence, follow-up colonoscopy results in a greater increase in favorable predicted outcomes than screening colonoscopy. Previous CRC-AIM analyses have demonstrated that incorporating more realistic adherence rates could further widen the magnitude in predicted outcomes between screening and follow-up colonoscopies (Piscitello et al., 2020, Fendrick et al., 2021a). Similar to our findings, other microsimulation analyses have found that predicted LYG increased for FIT use in Medicare beneficiaries when it was assumed that removing patient cost-sharing for a follow-up colonoscopy increased adherence to initial screening, follow-up colonoscopy, and surveillance colonoscopies (Peterse et al., 2017).

We estimate that a colonoscopy performed following a positive stool-based screening test produces substantially more clinical benefit than when colonoscopy is performed as an initial CRC screening test. This finding was robust for average-risk (45–75 years) and Medicare-age (65–75 years) populations. Failure to complete the CRC screening process after an individual has been identified at increased risk of CRC leads to suboptimal clinical outcomes and inefficient use of resources. A retrospective study of veterans ages 50–75 years between 1999 and 2010 reported that of those with an abnormal fecal occult blood test or FIT (n = 400,169), 44% (n = 175,482) did not receive a follow-up colonoscopy (San Miguel et al., 2021). Lack of a follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months after a positive mt-sDNA test has been reported to reach up to 28% (Cooper et al., 2021). These data support the removal of cost barriers and implementation of other tactics that encourage – not discourage – follow-up colonoscopies after a positive stool-based screening result to further reduce the burden of CRC.

5. Data availability

CRC-AIM demonstrates the approach by which existing CRC models can be reproduced from publicly available information and provides a ready opportunity for interested researchers to leverage the model for future collaborative projects or further adaptation and testing. To promote transparency and credibility of this new model, we have made available CRC-AIM’s formulas and parameters on a public repository (https://github.com/CRCAIM/CRC-AIM-Public).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

A. Mark Fendrick: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Bijan J. Borah: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. A. Burak Ozbay: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Leila Saoud: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Paul J. Limburg: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: A.M. Fendrick has been a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Centivo, Community Oncology Association, Covered California, EmblemHealth, Exact Sciences, Freedman Health, GRAIL, Harvard University, Health & Wellness Innovations, Health at Scale Technologies, MedZed, Penguin Pay, Risalto, Sempre Health, the State of Minnesota, U.S. Department of Defense, Virginia Center for Health Innovation, Wellth, and Zansors; has received research support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Gary and Mary West Health Policy Center, Arnold Ventures, National Pharmaceutical Council, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the State of Michigan, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. B.J. Borah has nothing to disclose. L. Saoud and A.B. Ozbay are employees of Exact Sciences Corporation. P.J. Limburg serves as Chief Medical Officer for Screening at Exact Sciences through a contracted services agreement with Mayo Clinic. Dr. Limburg and Mayo Clinic have contractual rights to receive royalties through this agreement.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Erin P. Scott, PhD, of Maple Health Group, LLC, funded by Exact Sciences Corporation. These data were presented at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) Annual Meeting, Virtual Meeting, 2020.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided through a contract with Exact Sciences Corporation. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. Exact Sciences Corporation contributed to the study design, data analysis, interpretation of the data, and writing of the report.

Contributor Information

A. Mark Fendrick, Email: amfen@med.umich.edu.

Bijan J. Borah, Email: Borah.Bijan@mayo.edu.

A. Burak Ozbay, Email: bozbay@exactsciences.com.

Leila Saoud, Email: lsaoud@exactsciences.com.

Paul J. Limburg, Email: limburg.paul@mayo.edu.

References

- Cancer trends progress report. Online summary of trends in US cancer control measures: Colorectal cancer screening. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH, DHHS; 2020 [cited 2021 May 4]. Available from: https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/colorectal_cancer.

- Cooper G.S., Grimes A., Werner J., Cao S., Fu P., Stange K.C. Barriers to follow-up colonoscopy after positive FIT or multitarget stool DNA testing. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021;34(1):61–69. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.01.200345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K.W., Barry M.J., Mangione C.M., Cabana M., Caughey A.B., Davis E.M., Donahue K.E., Doubeni C.A., Krist A.H., Kubik M., Li L.i., Ogedegbe G., Owens D.K., Pbert L., Silverstein M., Stevermer J., Tseng C.-W., Wong J.B. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Jama. 2021;325(19):1965. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Description and Validation of the Colorectal Cancer and Adenoma Incidence & Mortality (CRC-AIM) Microsimulation Model [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.02.966838v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fendrick, A.M., Fisher, D.A., Saoud, L., et al., 2021a. Impact of Patient Adherence to Stool-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening and Colonoscopy Following a Positive Test on Clinical Outcomes. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.). In Press. 10.1158/1940-6207.capr-21-0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fendrick A.M., Princic N., Miller-Wilson L.-A., Wilson K., Limburg P. Out-of-Pocket Costs for Colonoscopy After Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening Among US Adults With Commercial and Medicare Insurance. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(12):e2136798. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.36798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterse E.F.P., Meester R.G.S., Gini A., Doubeni C.A., Anderson D.S., Berger F.G., Zauber A.G., Lansdorp-Vogelaar I. Value Of Waiving Coinsurance For Colorectal Cancer Screening In Medicare Beneficiaries. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2017;36(12):2151–2159. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piscitello A., Saoud L., Fendrick A.M., Borah B.J., Hassmiller Lich K., Matney M., Ozbay A.B., Parton M., Limburg P.J., Picone G.A. Estimating the impact of differential adherence on the comparative effectiveness of stool-based colorectal cancer screening using the CRC-AIM microsimulation model. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0244431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Miguel Y., Demb J., Martinez M.E., Gupta S., May F.P. Time to Colonoscopy After Abnormal Stool-Based Screening and Risk for Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):1997–2005.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat A., Kahi C.J., Burke C.A., Rabeneck L., Sauer B.G., Rex D.K. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Colorectal Cancer Screening 2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021;116(3):458–479. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A.M.D., Fontham E.T.H., Church T.R., Flowers C.R., Guerra C.E., LaMonte S.J., Etzioni R., McKenna M.T., Oeffinger K.C., Shih Y.-C., Walter L.C., Andrews K.S., Brawley O.W., Brooks D., Fedewa S.A., Manassaram-Baptiste D., Siegel R.L., Wender R.C., Smith R.A. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68(4):250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.21457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

CRC-AIM demonstrates the approach by which existing CRC models can be reproduced from publicly available information and provides a ready opportunity for interested researchers to leverage the model for future collaborative projects or further adaptation and testing. To promote transparency and credibility of this new model, we have made available CRC-AIM’s formulas and parameters on a public repository (https://github.com/CRCAIM/CRC-AIM-Public).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

A. Mark Fendrick: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Bijan J. Borah: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. A. Burak Ozbay: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Leila Saoud: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Paul J. Limburg: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.