Abstract

Background

Recently, the value of natural products has been extensively considered because these resources can potentially be applied to prevent and treat coronavirus pneumonia 2019 (COVID-19). However, the discovery of nature drugs is problematic because of their complex composition and active mechanisms.

Methods

This comprehensive study was performed on flavonoids, which are compounds with anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects, to show drug discovery and active mechanism from natural products in the treatment of COVID-19 via a systems pharmacological model. First, a chemical library of 255 potential flavonoids was constructed. Second, the pharmacodynamic basis and mechanism of action between flavonoids and COVID-19 were explored by constructing a compound–target and target–disease network, targets protein-protein interaction (PPI), MCODE analysis, gene ontology (GO), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment.

Results

In total, 105 active flavonoid components were identified, of which 6 were major candidate compounds (quercetin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), luteolin, fisetin, wogonin, and licochalcone A). 152 associated targets were yielded based on network construction, and 7 family proteins (PTGS, GSK3β, ABC, NOS, EGFR, and IL) were included as central hub targets. Moreover, 528 GO items and 178 KEGG pathways were selected through enrichment of target functions. Lastly, molecular docking demonstrated good stability of the combination of selected flavonoids with 3CL Pro and ACEⅡ.

Conclusion

Natural flavonoids could enable resistance against COVID-19 by regulating inflammatory, antiviral, and immune responses, and repairing tissue injury. This study has scientific significance for the selective utilization of natural products, medicinal value enhancement of flavonoids, and drug screening for the treatment of COVID-19 induced by SARS-COV-2.

Keywords: Systems pharmacology, Natural products, Flavonoids, COVID-19, Molecular docking

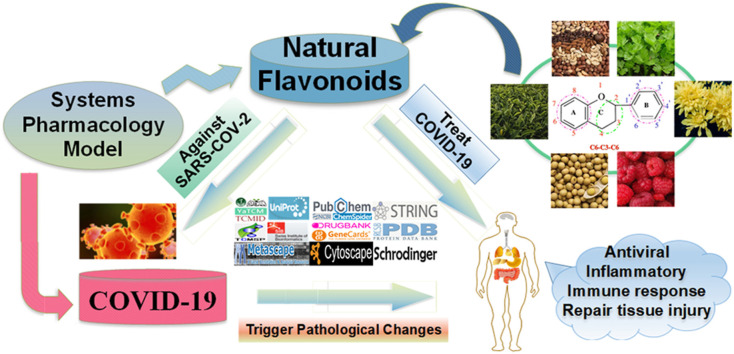

Graphical abstract

1. Background

The infectivity and fatality rate of coronavirus pneumonia 2019 (COVID-19) induced by SARS-COV-2 is significantly higher than that of other viral pneumonias. As of January 14, 2022, COVID-19, the third large-scale epidemic after severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), has infected 318 million people and caused 5.5 million deaths globally [1,2]. At present, the development and efficacy verification of specific therapeutics or vaccines still require balance speed with rigor. Moreover, elimination of pulmonary inflammation and repair of injury in patients with coronavirus infection are also important tasks [3]. Thus, it is essential to explore effective drugs with stable access and low economic costs.

Natural products (such as flavonoids, alkaloids, artemisinins, and peptides) with polypharmacological properties have shown great promise as novel therapeutics for various complex diseases [4]. The biological activities of these functional molecules against COVID-19 have been successfully explored. In the notice on issuing the diagnosis and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia trial version 1–8 and other treatment guidelines in China, more than 250 prescriptions and patent medicines, including natural products (with Western medicine), were added to the recommended drugs for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 [5]. By analyzing the frequency, compatibility principle, and action mechanism of recommended drugs, scientists have used natural products, especially flavonoids, as key compounds to reduce the incidence of severe or critical events, improve clinical recovery, and help alleviate symptoms such as cough or fever.

Flavonoids, which are typical compounds found in natural products, are widely distributed in nature and have a long history of medicinal and edible homology [6]. They not only exist in medicinal plants but also account for a large proportion of people's daily food and their adaptability to organisms has reached a certain level [7]. For the treatment of COVID-19, flavonoids can serve as an important resource based on their numerous pharmacological properties, such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, which have been verified by summary of comprehensive information and updated evidence for patients with various symptoms [8,9]. In addition, a series of specific in silico and in vitro experimental studies confirmed the mechanism of flavonoids in preventing and treating COVID-19 [10]. For example, baicalin and baicalein have been reported to inhibit coronavirus in infected Vero E6 cells, as determined by CCK-8 combined with qRT-PCR [11]. As some flavonoids have been used in practical applications to alleviate SARS-CoV-2 infection, a rapid and effective method is necessary to explore more active molecules in natural flavonoids and study their mechanisms of action.

Systems pharmacology is a holistic and systematic research method that uses a variety of group technologies, including systems biology, integration of computer virtual computing, high-throughput genomic analysis, and network databases [12,13]. In recent years, systems pharmacology has become an effective tool for revealing the regulatory network effect of biological targets and chemical entities of drugs in the body because of its emphasis on the comprehensiveness of drug interactions, which is consistent with the multi-target and multi-pathway characteristics of natural products [14,15]. In addition, as a research method combining physical and chemical principles with scientific calculation algorithms, molecular docking technology can predict the binding effect of natural flavonoids with COVID-19-related proteins and calculate the parameters of the binding mode, binding energy, and stability by computer simulation [16].

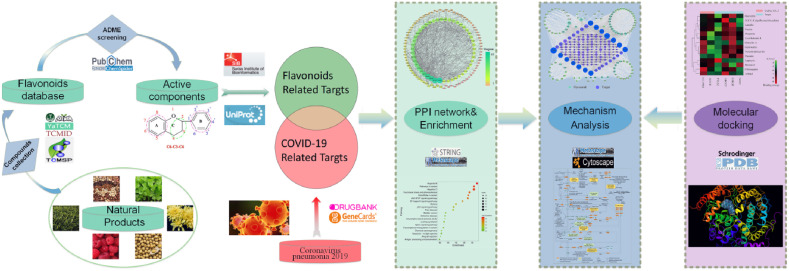

In this study, based on essential theory and clinical experience, a method of network pharmacology combined with molecular docking was adopted to demonstrate the advantages of effective substances in flavonoids against COVID-19 with the comprehensive regulation of multiple targets and pathways. By establishing a complete program with multi-disciplinary and multi-technology as shown in Fig. 1 , this study could manage natural product resources with high throughput and enhance the efficiency of screening compounds to enrich the drug library systematically. This exploration of the scientific value and mechanism of action of potential natural products can provide a novel approach for the development of new drugs and bioproducts for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Whole technical route of present research based on network pharmacology and molecular docking for revealing flavonoids against COVID-19 in multiple targets and pathways.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Compounds collection and screening

Natural flavonoids with pharmacological activity were retrieved from five TCM pharmacology databases including TCMSP (http://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php), TCMID (http://www.megabionet.org/tcmid), TCMIP (http://www.tcmip.cn/TCMIP), BATMAN-TCM (http://bionet.ncpsb.org.cn/batman-tcm/), and YaTCM (http://cadd.pharmacy.nankai.edu.cn/yatcm) [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. The structures of compounds were then compared with the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and PubChem CID was obtained [22]. According to ADME pharmacokinetic properties (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and exclusion) in TCMSP database, the chemical compounds satisfying oral bioavailability (OB) ≥30% and drug-likeness property (DL) ≥0.18 were selected as candidate active components [[23], [24], [25]]. Meanwhile, some compounds with low OB or DL were also selected because of their excellent pharmacological activities or high contents, such as puerarin, isoflavone, and others [[26], [27], [28]].

2.2. Potential target prediction and validation

The structure of candidate flavonoids was uniformly stored in SDF format using ChemBioDraw version 19.0 and the SMILES format was imported into the SwissTargetPrediction database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch), searching for similarities between targets to find the top 100 targets for each compound [29,30]. The attribute was set to “homo sapiens”. The specific parameter probability of each target was calculated during data processing. Protein targets with parameter probability ≥0 were standardized as UniProt ID in the UniProt protein database (https://www.uniprot.org) [31]. With “novel coronavirus pneumonia”, “novel coronavirus”, and other diseases related to COVID-19 as keywords, the potential targets were explored in the GeneCards database (https://www. genecards.org) [32]. A high score indicated that the target was closely related to the disease. In addition, the targets of four Western medicines (which have been used clinically for COVID-19 treatment), namely, lopinavir, ritonavir, chloroquine (no longer recommended), and arbidol were searched in the DrugBank database (https://www.drugbank.ca) for supplementation [33]. By comparing and removing the repeat targets in two databases, the COVID-19-related targets were obtained and standardized as UniProt ID. A Venn diagram was established to clarify the relationship between the two sets of potential target information using Venny version 2.1 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny). The intersection targets were selected as targets of natural flavonoids for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

2.3. PPI network and MCODE modules analysis

The intersection target was submitted to the STRING version 11.0 database (https://string-db.org) to construct protein-protein interaction (PPI) network mode [34,35]. The biological species was set to “Homo sapiens” and the minimum interaction threshold was set to “highest confidence (>0.9)”. Cytoscape version 3.8.0 was used to map relevant target information, thereby constructing the analysis network, removing isolated nodes, and retaining the largest connected subgraph [36]. High-correlation targets were obtained in terms of network degree-value and betweenness centrality. Furthermore, the Metascape platform (http://metascape.org) was used to explore biological process of interaction between potential targets [37]. The P-value was set to “<0.01”, the smallest count was set to “3”, and the enrichment factor was set to “>1.5”. According to the P-value after enrichment analysis, the top three functional modules were selected using the molecular complex detection (MCODE) plug-in [38].

2.4. GO function and KEGG pathways enrichment

In organisms, genes cannot perform their functions independently. Gene ontology (GO) function and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were used to provide a more systematic and comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of action [39,40]. The associated targets of the candidate flavonoids and COVID-19 were recorded on the Metascape. The input/analysis as species was set to “H.sapiens”, the P-value was set to “<0.01”. The main biological processes were corrected using the Bonferroni method and the correlation was estimated using the enrichment score (-log10 (P-value)). On the basis of the multi-system pathological changes in patients and the wide availability of natural flavonoids in this survey, the traditional single method of analyzing pathway correlation by P-value is prone to bias. Therefore, using the hierarchical clustering results of Metascape, cluster analysis for KEGG pathways was carried out in combination with the ClueGO plug-in to reduce the research deviation in network proximity analysis [41].

2.5. Network construction and analysis

The CytoHubba tool was applied to calculate three network topology parameters (degree-value of connection, betweenness, and closeness) of compounds and targets, thereby identifying key nodes. The green diamond nodes, blue circular nodes, and red hexagonal nodes represent active flavonoids, protein targets, and disease categories, respectively. The size and color depth of the nodes were correlated with three network topology parameters, namely, the degree-value of connection, betweenness, and closeness. The straight lines represent interaction while the degree-value and betweenness centrality reflect the betweenness of regulatory effects.

2.6. Molecular docking verification

The top four correlation targets and top ten correlation flavonoids in the network were used as the receptors and ligands respectively. 3CL Pro (PDBID: 6m2n) and ACEⅡ (PDBID: 1r4l) were used as COVID-19-related receptors because 3CL Pro is the main protease involved in virus replication and ACEⅡ is a cell receptor of SARS-COV-2 invading the human body [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46]]. Western medicine for COVID-19 was used as a positive control for ligands. The crystal structures of protein targets and compounds were obtained from the PDB protein database (http://www.rcsb.org/), and the scientific name of the source organism was set to “Homo sapiens” [47]. Schrodinger version 2018 software was used to conduct molecular docking between the ligand and the receptor [48]. After the standardized operation of dehydrogenation and water addition of the compound, the possibility and stability of docking were evaluated based on the space site and binding ability. A binding energy of less than −5 kJ/mol represents a good binding effect. The smaller the docking score, the higher binding rate between the receptor and ligand. The docking results verified the scientific nature of the study based on network pharmacology.

3. Result

3.1. Active compounds screening

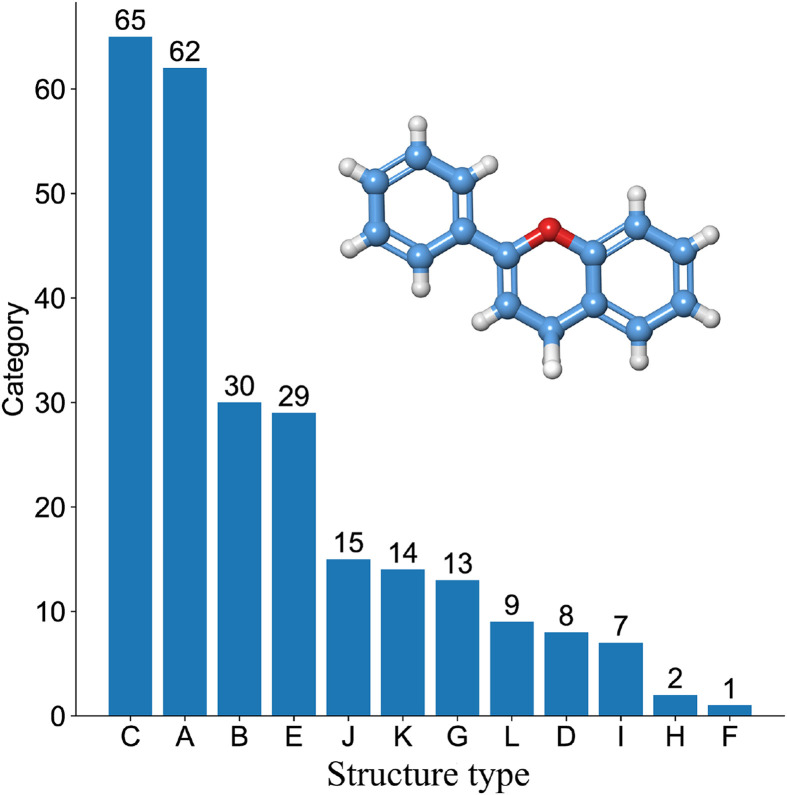

A chemical substance library containing 255 representative flavonoids was constructed and the active compounds were matched to specific pharmacokinetic parameters. The potential flavonoid category distributions are shown in Fig. 2 . Their parent nuclei were classified into 12 types depending on their flavonoid substitution sites and substituent types. The y-axis in Fig. 2 represents the number of candidate compounds in each category. The compounds with the highest proportions were flavones, flavonols, and chalcones. A total of 105 active compounds were obtained through OB ≥ 30% and DL ≥ 0.18 threshold screening or literature supplement. They were numbered according to their categories and their characteristic information is presented in Table 1 .

Fig. 2.

Distribution of structure type for 255 candidate flavonoids. The y-axis represented the number of candidate compounds in each category. A—Flavone; B—Flavanone; C—Flavonol; D—Flavanonl; E—Isoflavone; F—Isoflavanone; G— Chalcone; H—Dihydrochalcone; I—Anthocyanidin; J—Flavanol; K—Biflavonoid; L—Miscellaneous Flavonoid.

Table 1.

ADME characteristic information of 105 active flavonoids.

| Label | Compound | PubChem CID | OB/% | DL | Label | Compound | PubChem CID | OB/% | DL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Panicolin | 5320399 | 76.26 | 0.29 | C7 | Erianthin | 5320351 | 49.55 | 0.48 |

| A2 | Norartocarpetin | 72344 | 61.67 | 0.52 | C8 | Rhamnazin | 5320945 | 47.14 | 0.34 |

| A3 | Norartocarpetin | 5481970 | 54.93 | 0.24 | C9 | Quercetin | 5280343 | 46.43 | 0.28 |

| A4 | Corymbosin | 10970376 | 51.96 | 0.41 | C10 | Morin | 5281670 | 46.23 | 0.27 |

| A5 | IsoSinensetin | 632135 | 51.15 | 0.44 | C11 | Eupalitin | 5748611 | 46.11 | 0.33 |

| A6 | Sinensetin | 145659 | 50.56 | 0.45 | C12 | Galangin | 5281616 | 45.55 | 0.21 |

| A7 | Salvigenin | 161271 | 49.07 | 0.33 | C13 | Icaritin | 5318980 | 45.41 | 0.44 |

| A8 | 6-Hydroxyluteolin | 5281642 | 46.93 | 0.28 | C14 | Quercetagetin | 5281680 | 45.01 | 0.31 |

| A9 | Cirsiliol | 160237 | 43.46 | 0.34 | C15 | Axillarin | 5281603 | 42.60 | 0.37 |

| A10 | Oroxylin A | 5320315 | 41.37 | 0.23 | C16 | Eupatolitin | 5317291 | 42.55 | 0.37 |

| A11 | Pectolinarigenin | 5320438 | 41.17 | 0.30 | C17 | Kaempferol | 5280863 | 41.88 | 0.24 |

| A12 | Negletein | 471719 | 41.16 | 0.23 | C18 | Noranhydroicaritin | 5318624 | 38.04 | 0.53 |

| A13 | Baicalin | 64982 | 40.12 | 0.75 | C19 | Syringetin | 5281953 | 36.82 | 0.37 |

| A14 | Linarin | 5317025 | 39.84 | 0.71 | C20 | Herbacetin | 5280544 | 36.07 | 0.27 |

| A15 | Norwogonin | 5281674 | 39.40 | 0.21 | C21 | Gossypetin | 5280647 | 35.00 | 0.31 |

| A16 | Andrographin | 5318506 | 37.57 | 0.33 | D1 | Garbanzol | 442410 | 83.67 | 0.21 |

| A17 | Genkwanin | 5281617 | 37.13 | 0.24 | D2 | Taxifolin | 439533 | 57.84 | 0.27 |

| A18 | Luteolin | 5280445 | 36.16 | 0.25 | D3 | (±)-Fustin | 5317435 | 50.91 | 0.24 |

| A19 | Chrysoeriol | 5280666 | 35.85 | 0.27 | D4 | Astilbin | 119258 | 36.46 | 0.74 |

| A20 | Fortunellin | 5317385 | 35.65 | 0.74 | D5 | Engeletin | 6453452 | 36.27 | 0.70 |

| A21 | Acacetin | 5280442 | 34.97 | 0.24 | E1 | Formononetin | 5280378 | 69.67 | 0.21 |

| A22 | Pedalitin | 31161 | 34.02 | 0.31 | E2 | Licoricone | 5319013 | 63.58 | 0.47 |

| A23 | Baicalein | 5281605 | 33.52 | 0.21 | E3 | 3′-O-Methylorobol | 5319744 | 57.41 | 0.27 |

| A24 | Hypolaetin | 5281648 | 33.24 | 0.28 | E4 | Odoratin | 13965473 | 49.95 | 0.30 |

| A25 | IsoVitexin | 162350 | 31.29 | 0.72 | E5 | Isoflavone | 72304 | 49.03 | 0.13 |

| A26 | Diosmetin | 5281612 | 31.14 | 0.27 | E6 | 4′-7-Dihydroxy-3′-Methoxyisoflavone | 5319422 | 48.57 | 0.24 |

| A27 | Hispidulin | 5281628 | 30.97 | 0.27 | E7 | Calycosin | 5280448 | 47.75 | 0.24 |

| A28 | Wogonin | 5281703 | 30.68 | 0.23 | E8 | Irilone | 5281779 | 46.87 | 0.36 |

| A29 | Skrofulein | 188323 | 30.35 | 0.30 | E9 | Pratensein | 5281803 | 39.06 | 0.28 |

| A30 | Eupatorin | 97214 | 30.23 | 0.37 | E10 | Isoformononetin | 3764 | 38.37 | 0.21 |

| B1 | Hesperetin | 72281 | 70.31 | 0.27 | E11 | Irisolidone | 5281781 | 37.78 | 0.30 |

| B2 | Dihydrooroxylin | 25721350 | 66.06 | 0.23 | E12 | Puerarin | 5281807 | 24.03 | 0.69 |

| B3 | Butin | 92775 | 65.94 | 0.21 | F1 | Violanone | 44446884 | 80.24 | 0.30 |

| B4 | Liquiritin | 503737 | 65.69 | 0.74 | G1 | Licochalcone A | 5318998 | 40.79 | 0.29 |

| B5 | Naringenin | 439246 | 59.29 | 0.21 | G2 | Okanin | 5281294 | 98.81 | 0.20 |

| B6 | Isoxanthohumol | 513197 | 56.81 | 0.39 | G3 | Licochalcone B | 5318999 | 76.76 | 0.19 |

| B7 | Alpinetin | 821279 | 55.23 | 0.20 | I1 | Delphinidin | 128853 | 40.63 | 0.28 |

| B8 | Norkurarinol | 44563159 | 51.28 | 0.64 | I2 | Pelargonidin | 440832 | 37.99 | 0.21 |

| B9 | Pinocembrin | 68081 | 64.72 | 0.18 | I3 | Petunidin | 441774 | 30.05 | 0.31 |

| B10 | Farrerol | 91144 | 42.65 | 0.26 | J1 | Proanthocyanidin B1 | 11250133 | 67.87 | 0.66 |

| B11 | Pinostrobin | 6950539 | 41.92 | 0.20 | J2 | LeucoPelargonidin | 3286789 | 57.97 | 0.24 |

| B12 | Neoponcirin | 16760075 | 41.24 | 0.72 | J3 | Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) | 65064 | 55.09 | 0.77 |

| B13 | Carthamidin | 188308 | 41.15 | 0.24 | J4 | Catechin | 9064 | 54.83 | 0.24 |

| B14 | Poriol | 301798 | 38.45 | 0.24 | J5 | (+)-Epicatechin gallate | 5276454 | 53.57 | 0.75 |

| B15 | IsoBavachin | 193679 | 36.57 | 0.32 | J6 | LeucoCyanidin | 440833 | 30.84 | 0.27 |

| B16 | Poncirin | 45359875 | 36.55 | 0.74 | J7 | LeucoDelphinidin | 44563331 | 30.02 | 0.31 |

| B17 | Liquiritigenin | 114829 | 32.76 | 0.18 | L1 | Aureusidin | 5281220 | 53.42 | 0.24 |

| C1 | Azaleatin | 5281604 | 54.28 | 0.30 | L2 | Sumatrol | 442824 | 70.92 | 0.91 |

| C2 | Patuletin | 5281678 | 53.11 | 0.34 | L3 | Silydianin | 11982272 | 59.65 | 0.76 |

| C3 | Fisetin | 5281614 | 52.6 | 0.24 | L4 | Phaseollidin | 119268 | 52.04 | 0.53 |

| C4 | Kumatakenin | 5318869 | 50.83 | 0.29 | L5 | Cyclomulberrochromene | 5481969 | 36.79 | 0.87 |

| C5 | Eupatin | 5317287 | 50.8 | 0.41 | L6 | Karanjin | 100633 | 69.56 | 0.34 |

| C6 | Isorhamnetin | 5281654 | 49.6 | 0.31 |

A—Flavone; B—Flavanone; C—Flavonol; D—Flavanonl; E—Isoflavone; F—Isoflavanone; G—Chalcone; H—Dihydrochalcone; I—Anthocyanidin; J—Flavanol; K—Biflavonoid; L—Miscellancous Flavonoid.

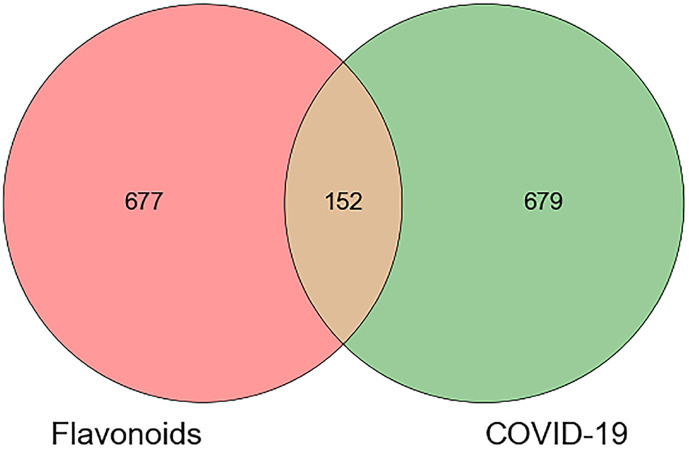

3.2. Target prediction and validation

A total of 829 protein targets with parameter probability >0, which were related to 105 active compounds, were screened. 792 COVID-19 targets and 44 Western medicine targets were retrieved. After removing duplicates, a total of 831 COVID-19 disease-related targets were identified. After Venn mapping (Fig. 3 ), 152 intersection targets were obtained for all the 105 active flavonoids as shown in Table 2 . Their characteristics are presented in Table S1. The targets covered a variety of categories with enzymes, kinases, and signaling pathways accounting for a high proportion.

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram of flavonoids and COVID-19-related targets.

Table 2.

152 potential targets of natural flavonoids against COVID-19.

| NO. | Gene Symbol | Uniprot ID | NO. | Gene Symbol | Uniprot ID | NO. | Gene Symbol | Uniprot ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ABCB1 | P08183 | 52 | EIF2AK3 | Q9NZJ5 | 103 | MAPT | P10636 |

| 2 | ABCC1 | P33527 | 53 | ENPP1 | P22413 | 104 | MCL1 | Q07820 |

| 3 | ABCG2 | Q9UNQ0 | 54 | EP300 | Q09472 | 105 | NAE1 | Q13564 |

| 4 | ACEⅡ | Q9BYF1 | 55 | ERN1 | O75460 | 106 | NFKB1 | P19838 |

| 5 | ADAM17 | P78536 | 56 | EZR | P15311 | 107 | NOS2 | P35228 |

| 6 | ADAMTS1 | Q9UHI8 | 57 | F10 | P00742 | 108 | NOS3 | P29474 |

| 7 | ANPEP | P15144 | 58 | F2 | P00734 | 109 | NPEPPS | P55786 |

| 8 | APOD | P05090 | 59 | FCER2 | P06734 | 110 | NR1I2 | O75469 |

| 9 | BAD | Q92934 | 60 | FGF2 | P09038 | 111 | PARP1 | P09874 |

| 10 | BAK1 | Q16611 | 61 | FGFR2 | P21802 | 112 | PI4KB | Q9UBF8 |

| 11 | BAX | Q07812 | 62 | FGFR3 | P22607 | 113 | PIK3CA | P42336 |

| 12 | BCL2 | P10415 | 63 | FKBP1A | P62942 | 114 | PIK3CB | P42338 |

| 13 | BCL2A1 | Q16548 | 64 | FOS | P01100 | 115 | PIK3CD | O00329 |

| 14 | BCL2L1 | Q07817 | 65 | G6PD | P11413 | 116 | PIK3CG | P48736 |

| 15 | BCL2L2 | Q92843 | 66 | GAPDH | P04406 | 117 | PIK3R1 | P27986 |

| 16 | BRD4 | O60885 | 67 | GOT1 | P17174 | 118 | PITRM1 | Q5JRX3 |

| 17 | CASP3 | P42574 | 68 | GPT | P24298 | 119 | PLA2G4A | P47712 |

| 18 | CASP6 | P55212 | 69 | GSK3A | P49840 | 120 | PLAT | P00750 |

| 19 | CASP8 | Q14790 | 70 | GSK3B | P49841 | 121 | POR | P16435 |

| 20 | CAT | P04040 | 71 | GSTM1 | P09488 | 122 | PPARG | P37231 |

| 21 | CCL2 | P13500 | 72 | GUSB | P08236 | 123 | PRKACA | P17612 |

| 22 | CCNA2 | P20248 | 73 | HDAC2 | Q92769 | 124 | PRKCA | P17252 |

| 23 | CCND1 | P24385 | 74 | HMOX1 | P09601 | 125 | PRKCB | P05771 |

| 24 | CCND3 | P30281 | 75 | HPGDS | O60760 | 126 | PRKCE | Q02156 |

| 25 | CCNE1 | P24864 | 76 | HSP90B1 | P14625 | 127 | PTGS1 | P23219 |

| 26 | CD4 | P01730 | 77 | HSPA5 | P11021 | 128 | PTGS2 | P35354 |

| 27 | CD40LG | P29965 | 78 | HSPB1 | P04792 | 129 | RB1 | P06400 |

| 28 | CDK2 | P24941 | 79 | ICAM1 | P05362 | 130 | RELA | Q04206 |

| 29 | CDK4 | P11802 | 80 | IFNB1 | P01574 | 131 | SERPINE1 | P05121 |

| 30 | CDKN1B | P46527 | 81 | IFNG | P01579 | 132 | SIGMAR1 | Q99720 |

| 31 | CHEK2 | O96017 | 82 | IKBKB | O14920 | 133 | SIRT1 | Q96EB6 |

| 32 | COMT | P21964 | 83 | IL1A | P01583 | 134 | SLC6A4 | P31645 |

| 33 | COQ8B | Q96D53 | 84 | IL1β | P01584 | 135 | SLC28A3 | Q9HAS3 |

| 34 | CREB1 | P16220 | 85 | IL2 | P60568 | 136 | SLC29A1 | Q99808 |

| 35 | CRP | P02741 | 86 | IL4 | P05112 | 137 | SOD1 | P00441 |

| 36 | CTSB | P07858 | 87 | IL6 | P05231 | 138 | STAT1 | P42224 |

| 37 | CTSL | P07711 | 88 | IL10 | P22301 | 139 | STAT3 | P40763 |

| 38 | CXCL2 | P19875 | 89 | IMPDH1 | P20839 | 140 | STAT6 | P42226 |

| 39 | CXCL8 | P10145 | 90 | IMPDH2 | P12268 | 141 | SUMO1 | P63165 |

| 40 | CXCL10 | P02778 | 91 | IRF1 | P10914 | 142 | TBK1 | Q9UHD2 |

| 41 | CXCL11 | O14625 | 92 | IRF3 | Q14653 | 143 | TGFB1 | P01137 |

| 42 | CYP1A1 | P04798 | 93 | ITGAL | P20701 | 144 | TLR9 | Q9NR96 |

| 43 | CYP1A2 | P05177 | 94 | JAK1 | P23458 | 145 | TNF | P01375 |

| 44 | CYP2C9 | P11712 | 95 | LCK | P06239 | 146 | TP53 | P04637 |

| 45 | CYP2C19 | P33261 | 96 | LDHA | P00338 | 147 | TTR | P02766 |

| 46 | CYP3A4 | P08684 | 97 | LGALS3 | P17931 | 148 | TUBB3 | Q13509 |

| 47 | CYP3A7 | P24462 | 98 | MAPK1 | P28482 | 149 | TXN | P10599 |

| 48 | DNMT1 | P26358 | 99 | MAPK3 | P27361 | 150 | VCP | P55072 |

| 49 | DPP4 | P27487 | 100 | MAPK8 | P45983 | 151 | VEGFA | P15692 |

| 50 | EGFR | P00533 | 101 | MAPK14 | Q16539 | 152 | VIM | P08670 |

| 51 | EGR1 | P18146 | 102 | MAPKAPK2 | P49137 |

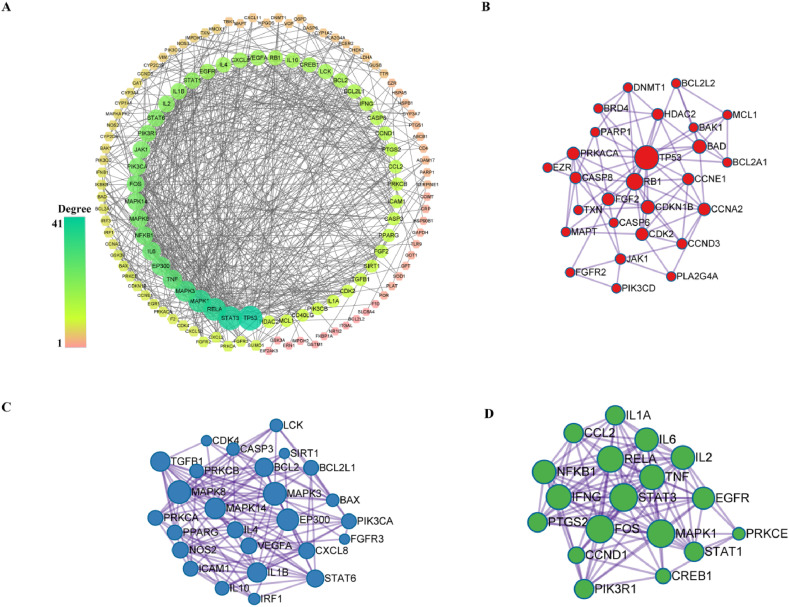

3.3. PPI network and MCODE module analysis

The number of edges and the average node degree-values in the PPI network were 643 and 8.46, respectively. Additionally, 52 protein targets were greater than the average degree-value. Furthermore, topological parameters were calculated using the CytoHubba tool, as shown in Fig. 4 A. On the basis of degree-value of the close constituent relationship, the top three functional modules with abundant biological processes were obtained after enrichment analysis. The results showed that the same family of targets (MAPK, IL, and PTGS) commonly gathered into a functional module in Fig. 4B–D. Meanwhile, different genes coordinate with each other to complete a series of biochemical reactions. The MCODE in our research performs highly correlated biological functions, such as viral carcinogenesis, apoptosis, and regulation of cytokine production.

Fig. 4.

PPI network and MCODE modules of intersection targets. (A) An overall view of the whole PPI network. (B–D) Three high correlation MCODE in PPI network. The size and color depth of node were correlated with three network topology parameters (degree-value of connection, betweenness, and closeness).

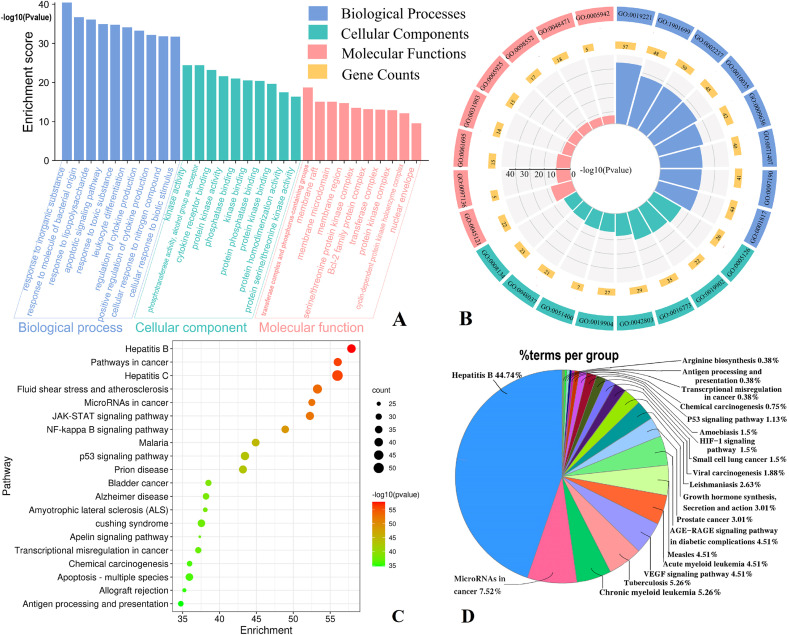

3.4. GO function and KEGG pathways enrichment

A total of 515 GO items were obtained, including 360 biological processes (BP) items, 76 cellular components (CC) items, and 92 molecular functions (MF). The top ten correlation terms for each category are shown in Fig. 5 A. Furthermore, Fig. 5B shows the distribution of the three types of GO item clusters. The position of target gene products in cells were mainly distributed in membrane rafts, membrane microdomains, transferring enzyme complexes, and sticking to a variety of cell membranes. Biological processes were mainly involved in cellular responses to inorganic substances, molecules of bacterial origin, toxic substances, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Molecular function mainly involved cytokines receptors, protein phosphatase binding, and protein kinase activity. The enrichment score of the three highly correlated items, which comprised apoptosis signaling pathways, leukocyte differentiation, and regulation of cytokine production, also exceeded 33 (Fig. 5A). In addition, 178 KEGG pathways were identified through annotation analysis and the top 20 pathways are shown in Fig. 5C. The color and size of the circle represent the P-value and target counts, respectively. The KEGG pathways with high correlation were hepatitis B, pathways in cancer, hepatitis C, fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis, microRNAs in cancer, JAK-STAT signaling pathway, and NF-kappaβ signaling pathway. KEGG pathway clusters analysis (Fig. 5D) showed that 44.74% of the pathways were involved in the hepatitis B cluster, while other high-correlation clusters included microRNAs in cancer, chronic myeloid leukemia, tuberculosis, and VEGF signaling pathway.

Fig. 5.

GO function and KEGG pathway enrichment of intersection targets. (A) Enrichment diagram of BP, CC, and MF terms. The vertical axis represents the enrichment score. (B) The cluster analysis of high correlation GO terms. (C) The bubble diagram of KEGG Pathway. The smaller the P-value (the redder the color), the higher the enrichment score. (D) The cluster analysis of KEGG pathway. The size of the region represents the proportion of pathways.

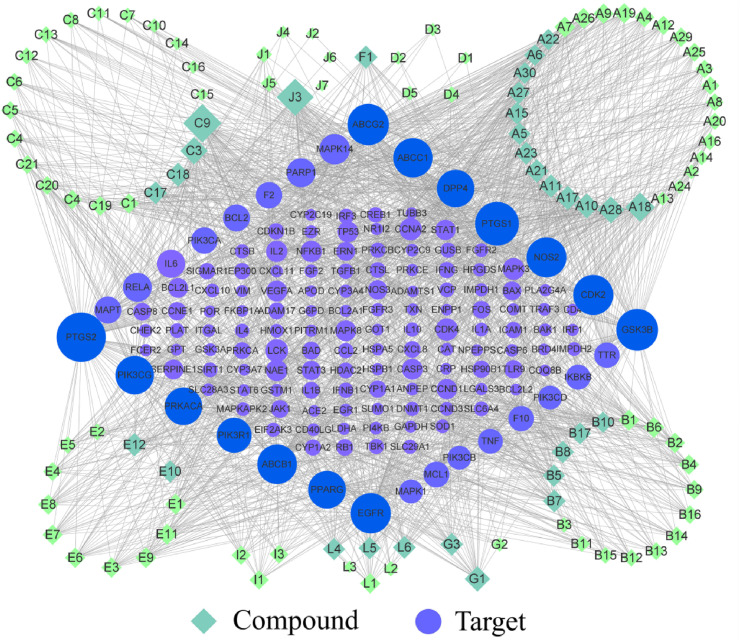

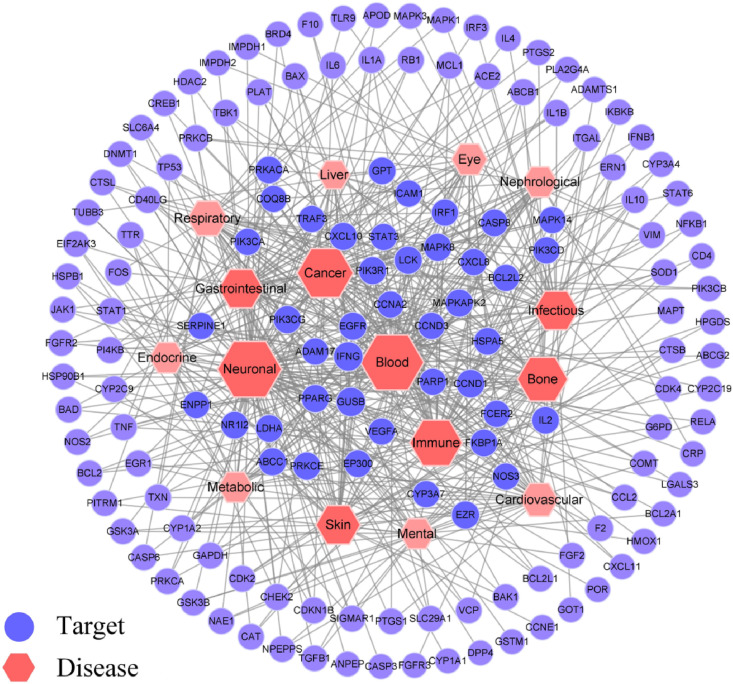

3.5. Network construction and analysis

Candidate flavonoids and potential targets were imported into Cytoscape to build a compound–target (C–T) network as shown in Fig. 6 . Quercetin (C9) and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG, J3), which are also two of the most abundant polyphenols in edible plants, connected 57 and 51 proteins in the C–T network, respectively. Luteolin (A18), fisetin (C3), wogonin (A28), licochalcone A (G1), oroxylin A (A10), genkwanin (A17), puerarin (E12), and noranhydroicaritin (C18) also showed strong pharmacological activities. In the network, the degree-value of 30 active components were greater than the median, and their structures are shown in Fig. S1. The targets with significant correlation were PTGS2, PTGS1, ABCG2, GSK3β, ABCB1, ABCC1, NOS2, EGFR, CDK2, PIK3CG, and PPARG. In addition, a target–disease (T–D) network was built with the summarized targets and corresponding disease information. Disease categories in Fig. 7 closely related to potential targets were concentrated in neuronal, blood, cancer, immune, and infectious diseases, which were highly consistent with the pathological characteristics of patients. Network displayed targets had a significant influence on the respiratory tract, cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal organ, and skin.

Fig. 6.

C-T network of active flavonoids and associated targets. The size and color depth of node were correlated with three network topology parameters (degree-value of connection, betweenness, and closeness).

Fig. 7.

T-D network of associated targets and significant disease categories. The size and color depth of node were correlated with three network topology parameters (degree-value of connection, betweenness, and closeness).

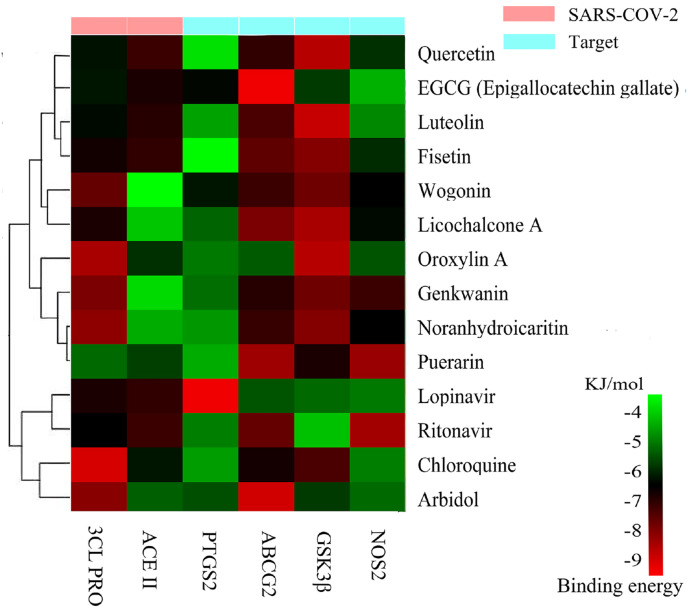

3.6. Molecular docking verification

The crystal structures of the top four correlation protein targets were obtained in PDB to serve as receptors, which included PTGS2 (PDBID: 5f19), ABCG2 (PDBID: 5omy), GSK3β (PDBID: 6y9r), and NOS2 (PDBID: 5xn3). The docking results showed that the flavonoids, as a typical example of natural products, with 3CL Pro and ACEⅡ generally reflected the combination of good stability capacity, some even better than clinical medicine. Specific binding energy is shown in Fig. 8 , and the change in color from green to red indicates a change in combination effect from low to high. The binding energy values (kJ/mol) of molecular docking between the ligands and receptors are shown in Table S2. A recent study on surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) binding showed that compounds with good binding ability to 3CL Pro included EGCG (J3) and other flavonoids, such as quercetin (C9), kaempferol (C17), luteolin (A18), isorhamnetin (C6), and wogonin (A28), which also verified the rationality of the docking results [49].

Fig. 8.

Molecular docking of flavonoids binding with targets and their binding energy.

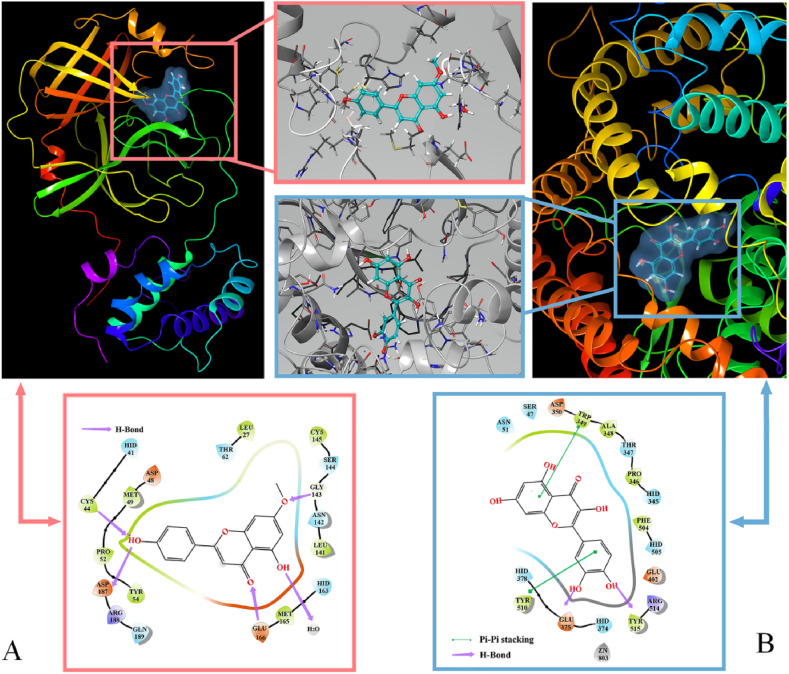

The active site of the protein was centered on the active site of the original ligand in the crystal structure. Given the high homology of the conformation of flavonoids, the binding effects (binding sites and forces) between flavonoids and COVID-19-related proteins were predominantly similar. As an example (Fig. 9 A), for the 3CL Pro combined with genkwanin (A17), the hydroxyl groups formed hydrogen bonds with residues of ASP187, and CYS44 at the active site of 3CL hydrolase, while carbonyl and methyl also interacted with GLU166 and GLY143. When ACEⅡ was combined with quercetin (C9) in Fig. 9B, Pi-Pi stacking between the benzene ring, TRP349 and TYR510 was the key relationship. The hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups, TYR515, and GLU375 were indispensable. These interactions promoted the stable binding of small flavonoid molecules to their active sites, thereby inhibiting protein activity [[50], [51], [52]]. Such active flavonoids could be used as potential inhibitors to block 3CL Pro and ACEⅡ combined with related targets at the molecular level, which could inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication.

Fig. 9.

Combination effects between flavonoids and COVID-19-related proteins. (A) Combination effect between genkwanin with 3CL Pro. (B) Combination effect between quercetin with ACEⅡ.

4. Discussion

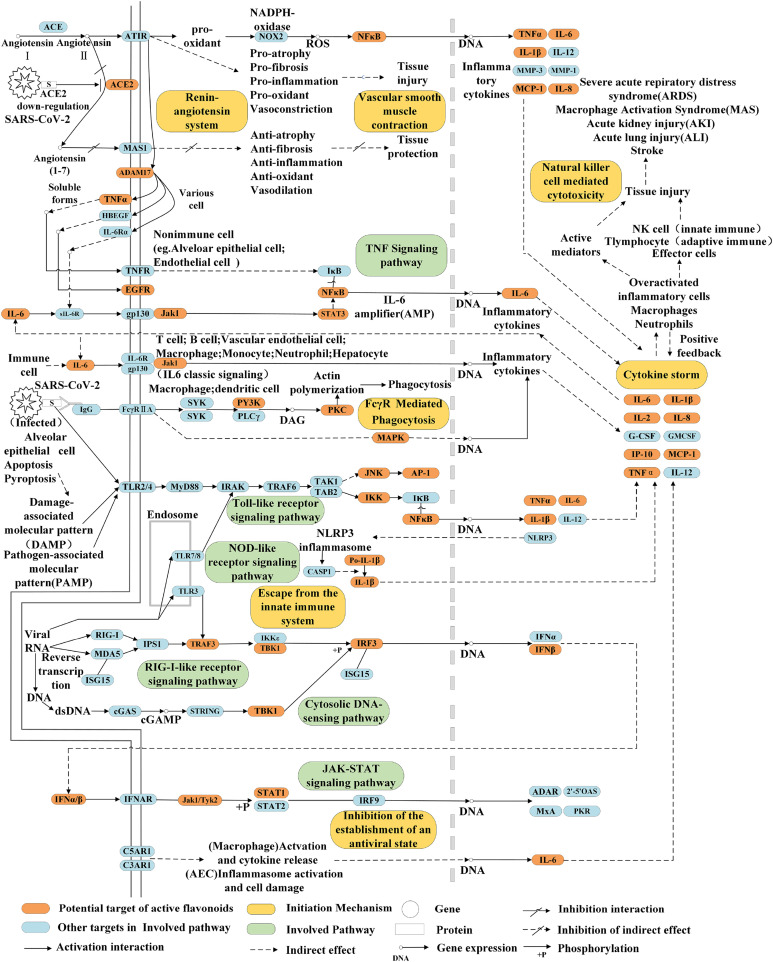

A total of 105 active compounds in the C-T network were widely distributed among natural flavonoids and most of them were closely related to multiple targets. PTGS (PTGS2, PTGS1), GSK3β, ABC (ABCG2, ABCB1, ABCC1), NOS (NOS2, NOS1), EGFR, IL (IL6, IL1β), blood coagulation factor (F2, F10), and other family targets were located at the center of the network, which gathered into the biological module. Association rules and compatibility network analysis indicated that distinct flavonoids could act together with the same target whereas multiple targets could be easily controlled by the same compound. This material base indicated that multiple flavonoid components could regulate multiple symptoms by applying to multiple targets in different pathways. Consistent with autopsy reports of patients, the network also showed that COVID-19 is involved in infection, inflammation, immune response, blood coagulation, tissue injury, and genetic polymorphism [53]. Fig. 10 shows the expression and regulatory interaction of flavonoid-related targets in pathways. The mechanisms of action were divided into inflammatory, antiviral, immune regulation, and tissue injury repair.

Fig. 10.

Underlying mechanisms of flavonoids in the treatment of COVID-19. Ingredients from flavonoids attenuate the symptoms by acting on inflammatory, antiviral, and immune regulation and repairing tissue injury.

4.1. Inflammatory

With the deepening of viral infections, cytokine storms have occurred in patients. Such events cause the uncontrolled release of excessive inflammatory factors by immune cells, which attack immune organs, and affect blood and circulatory systems [54]. Clinical investigations showed that 82.1% and 36.2% of the patients had lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, respectively. Pneumonia was observed in 79.1% of the patients and ground-glass opacity (50%) was the most frequent chest computed tomography finding. These results suggested that inflammatory storms and subsequent tissue damage were the most critical factors [55]. Therefore, as a key cytokine that triggers inflammatory storms, IL6 was used as an early warning indicator for severe cases in notice of issuing the diagnosis and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia trial (trial version 8). TNF, CCL2, IL2, CXCL10, IL1β, and other important inflammatory mediators are closely related to many biological processes [56]. Typically, the aggravation of inflammatory reactions generates mucus production and collagen deposition in the respiratory tract and even causes death through acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Thus, inflammation-associated proteins were at the center of the network and inflammation-related KEGG pathways accounted for a large proportion. First, flavonoids reduce the expression of inflammatory genes in cells at the translational and transcriptional levels. For instance, wogonin (A28) interfered with the nuclear localization sequence and amplicon of NF-κβ, thereby affecting the mRNA transcription of inflammatory factors in macrophages [57]. In addition, bioactive immunomodulatory compounds such as fisetin (C3) decrease the number of infiltrating neutrophils and affect the self-renewal, division, proliferation, and survival of immune cells (such as monocyte and dendritic cells) [58]. Furthermore, the enrichment scores of the Toll-like receptor and TNF signaling pathways in Fig. 5C were 31.8 and 35.2, respectively, which indicated that flavonoids were beneficial for regulating the two pathways as shown in Fig. 10. Flavonoids not only affect inflammasome activation but also interfere with the synthesis of protein complexes such as MAPK and NF-κβ. The expression intensity of inflammatory storms can be suppressed by flavonoids to achieve an anti-inflammatory effect in three ways.

4.2. Antiviral

The main active mechanism is conventional therapy with symptomatic support. The use of antiviral drugs to control outbreaks of infectious diseases is not a long-term strategy [59]. For instance, studies have shown that chloroquine potentially increases the frequency of cardiac side effects in patients [60]. Flavonoids have demonstrated antiviral activity against various viruses in animal models of varying diseases. First, active ingredients are beneficial for resisting the invasion and secretion of viruses, thereby inhibiting their infection in cells [61,62]. Furthermore, flavonoids interfere with the replication, transcription, and translation of the coronavirus RNA genome [10]. They mainly affect the function of intracellular organelles (endoplasmic reticulum, endosome, and others) or the secretion of protein factors (kinases, enzymes, and others) [63]. This process blocks the synthesis of viral proteins and the assembly of virus particles. Moreover, flavonoids are helpful in directional regulation to induce apoptosis and pyroptosis in infected host cells [64]. Flavonoids assist the activation of complements to secret membrane attack complex (MAC), forming hydrophilic membrane-penetrating channels that alter intracellular osmotic pressure, and contribute to cell disintegration [65,66]. These lesions affect FcγR-mediated phagocytosis or form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), ultimately eliminating the virus. For instance, kaempferol (C17) and its derivatives inhibit the 3A ion channel of SARS-CoV, thereby reducing viral release [67]. Quercetin (C9) and wogonin (A28) affect plaque formation in different influenza virus strains [68,69]. Similarly, numerous compounds targeting proteins (PTGS, DPP4, and CASP) can inhibit coronavirus replication both before and after viral infection [70]. The regulation of GSK3β and TNF by these compounds affects the phosphorylation of various proteins and the transformation of apoptotic factors, respectively [71,72]. In enrichment analyses, cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway, JAK-AKT signaling pathway, and RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway showed statistically significant differences compared with the others. These results indicated that flavonoids tended to establish antiviral states through these pathways which recognize SARS-COV-2 and generate immune responses [64,73]. In summary, the broad-spectrum antiviral effect of flavonoids is based on their multi-target synergistic characteristics.

4.3. Immune regulation

Rapid increases in viral factor levels following SARS-CoV-2-infected mammals, resulting in immune dysfunction contained pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) and damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP). Overexpression of natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity causes fever, diarrhea, and even serious complications such as macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Moreover, 76% of the surveyed patients in Jinyintan Hospital still had symptoms and the antibody level decreased generally after six months of discharge [74]. Therefore, three tasks of restoring the immune response include inhibiting the destruction of the innate immune system, maintaining homeostasis to alleviate abnormal symptoms, and regulating energy metabolism to promote nutrition absorption. Flavonoids have unique and significant advantages for these processes. By regulating the expression of PTGS family targets in the C–T network center, these ingredients affect the biosynthesis of prostaglandins and mediate a series of cellular activities [75,76]. Flavonoids also regulate cell receptors through target genes (DPP4, FOS, MAPK, and others), assisting the normal stress, differentiation and transformation of lymphocytes (monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells). For instance, licochalcone A (LCA, G1), a natural chalcone isolated from the root of licorice, plays a pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative roles in various cancer cell lines [77]. Furthermore, flavonoids are beneficial for stabilizing a number of functional cofactors such as glucosidase, convertase, and NADPH-oxidase, which gradually achieve adaptive immunity [78]. For example, fisetin (C3) triggers the activation of caspase-3 and caspase-8 and the lysis of polymerase (ADP-ribose), contributing to the induction of apoptosis [79]. Noranhydroicaritin (C18) is a typical tyrosinase inhibitor that regulates autophagy [80]. Moreover, flavonoids can remarkably contribute to the field of secretion and transportation of cellular substances. For instance, oroxylin A (A10) and other compounds can interact with solute carrier transporters and ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC) [81]. Notably, overexpression of ABC family targets results in increased effusion and decreased intracellular accumulation of natural products such as anticancer drugs and other drugs, leading to the failure of anticancer and antibacterial chemotherapy [82]. Therefore, the high frequency of targeting ABC with flavonoids in the C–T network is expected to be a breakthrough in the development of stable therapy for COVID-19. In addition, flavonoids possessed positive feedback for membrane fusion, actin polymerization, and endocytosis to eliminate the adverse effects of metabolic syndrome.

4.4. Repairing tissue injury

Among the multi-directional injuries resulting from SARS-COV-2, the most significant is the respiratory system. Viruses invade the respiratory mucosa through veins, thereby infecting alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) and other non-immune cells. Subsequently, an imbalance between oxidation and antioxidation is an important pathological mechanism of pulmonary fibrosis. Excessive cytokines production by inflammatory storms triggers acute lung injury (ALI). In addition to inhibiting the release of inflammatory cytokines, many flavonoids affect the biological and physical properties of the cell membrane, thereby directly reducing oxidative stress injury in the lung [83]. More compounds indirectly ameliorate pathological changes by regulating targets and signaling pathways. For instance, components treat hypertonic pulmonary edema through the VEGF signaling pathway and inhibit “epithelial–interstitial transformation” to alleviate pulmonary fibrosis through NOS family targets [84]. Furthermore, the combination of the S protein of SARS-COV-2 spike and ACEⅡ receptor on the cell surface promote the secretion of angiotensin (Ⅰ) and angiotensin (Ⅱ). This phenomenon concurrently inhibits the secretion of angiotensin (1–7). These pathological changes dysregulate the coagulation cascade, produce thrombosis, compromise blood supply, and damage the blood vessels and myocardial system [85]. Flavonoids, which have good binding energy with ACEⅡ and have a major impact on the renin–angiotensin system, can down-regulate the binding degree between viruses and cells at the molecular level. They also participate in angiogenesis and maintain the integrity of vascular development. For instance, quercetin (C9) significantly inhibited intercellular communication between gap junctions, thereby achieving myocardial protection [86]. Naringenin (B5) inhibits VGEF-induced angiogenesis by inhibiting the activity of the double-pore channel [87]. Coagulation assays of many compounds show a prolonged activation time of partial fibrinogen thrombin, and blood coagulation factor, which is also widely reflected in the network, thereby maintaining blood homeostasis and wound healing [88]. As EGCG has neuroprotective effects against nerve injury [89,90], flavonoids are effective options for repairing different histopathological damages in the T–D network, such as stroke and acute kidney injury (AKI).

The physiological activity and structure–activity relationship of flavonoids warrant further investigation. As a result of the difficulty of central ring connection, the lack of carbon double bonds, and other unstable factors, flavones (with the carbon ring double bond), flavonols (with hydroxyl), isoflavones (special benzene ring connection position), and chalcone have a high proportion of active compounds. In addition, on the basis of central epoxidation and the presence of specific hydroxyl groups, a slight change in the structure may affect the molecular dynamics and pharmacokinetics even if the molecular weights are similar. For instance, quercetin (C9), galangin (C12), and kaempferol (C17) have distinct efficacies with different numbers of -OH groups on a ring. Most of the 105 active compounds in our study were hydrophobic flavonoids, and the connected aglycones had planar structures. Common substitutions are hydroxyl, methyl, carbonyl, and glycoside. However, a few of them, such as norkurarinol (B8) and puerarin (E12), have a more complex structures. The glycoside linkage location is relatively fixed and the main linkage types are O-glycoside and C-glycoside. Pharmacokinetic properties of glycosides are associated with their structure. The latter usually has low solubility and difficult hydrolysis due to its stable C-glycoside. Flavonoid glycosides usually contain one or two glycoside residues, most of which are derivatives of the known glycogen structures. This finding indicated that the chemical structure of flavonoids exhibited a certain regularity. After calculating the binding energy value (kJ/mol) and analyzing the docking effect of 64 groups in Table S2, different flavonoids showed conservative or similar binding conformations across the active site of the same receptor, indicating that similar physiological activities of flavonoids were closely related to their highly homologous structures [91,92]. For instance, co-treatment with luteolin (A18) and kaempferol (C17) enhances the inhibitory effect on the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes [93]. This unique material foundation can reasonably strengthen the compatibility effect.

With the improvement in natural product extraction and separation detection methods, the acquisition and analysis of high-purity functional monomers have become simple and inexpensive. The comprehensive utilization of natural resources such as flavonoids and the promotion of their medicinal value have important scientific and economic significance. Among the 30 active ingredients with degree-value greater than the median, a few compounds in relevant studies have been shown to participate in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Studies and applications on the remaining active compounds are limited, indicating that flavonoids have great potential for mining space in drug development. This study confirmed that the protein targets had a significant effect on the regulation of expression and organization distribution, while the active function of targets and the expression of pathways were highly dependent on the flavonoid structure and the pathological mechanism of COVID-19. These results indicated that flavonoids, as an alternative therapeutic or preventive option, could enhance the clinical treatment of infectious diseases. Considering the diversity of flavonoid aglycones and glycosyls, the influence of synergistic pharmacological activities caused by these connection positions and connection methods will be the focus of further research.

5. Conclusion

This study systematically revealed the overall efficacy and intervention characteristics of 105 natural flavonoids and 152 COVID-19 related targets, which integrated compound screening, target prediction, PPI network and MCODE analysis, C–T and T–D network construction, GO function, KEGG pathway enrichment, and molecular docking. The unique synergistic effects of compounds such as flavones and flavonols were also highlighted by their homologous structures and functional groups. Combined with the clinicopathological features, the mechanisms of flavonoids in treating COVID-19 by regulating inflammation, antiviral, immunity, and tissue injury repair were further summarized. Our study provides a new strategy for exploring the unique antiviral activity, biological safety, and multitarget characteristics of natural flavonoids in vivo and in vitro. Thus, this study is beneficial for developing effective and economical innovative drugs or health products for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2021-MS-299) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770725).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105241.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization, WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/, (accessed January 2022).

- 2.Robson B. Computers and viral diseases. Preliminary bioinformatics studies on the design of a synthetic vaccine and a preventative peptidomimetic antagonist against the SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV, COVID-19) coronavirus. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozturk T., Talo M., Yildirim E.A., Baloglu U.B., Yildirim O., Acharya U.R. Automated detection of COVID-19 cases using deep neural networks with X-ray images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020;121 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:770–803. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, Notice On Issuing The Diagnosis And Treatment Protocol For Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia, http://www. nhc.gov.cn/xcs/xxgzbd/gzbd_index.shtml, (accessed January 2022).

- 6.Tapas A., Sakarkar D., Kakde R. Flavonoids as nutraceuticals: a review. Trop. J. Pharmaceut. Res. 2008;7:1089–1099. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v7i3.14693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crozier A., Jaganath I.B., Clifford M.N. Dietary phenolics: chemistry, bioavailability and effects on health. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:1001–1043. doi: 10.1039/B802662A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva Antonio A., Wiedemann L.S.M., Veiga-Junior V.F. Natural products' role against COVID-19. RSC Adv. 2020;10:23379–23393. doi: 10.1039/D0RA03774E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang K., Zhang P., Zhang Z., Youn J.Y., Zhang H., Cai H.L. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in the treatment of viral infections: efficacies and mechanisms. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russo M., Moccia S., Spagnuolo C., Tedesco I., Russo G.L. Roles of flavonoids against coronavirus infection. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020;328 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su H., Yao S., Zhao W., Li M., Liu J., Shang W., Xie H., Ke C., Gao M., Yu K., Liu H., Shen J., Tang W., Zhang L., Zuo J., Jiang H., Bai F., Wu Y., Ye Y., Xu Y. Discovery of baicalin and baicalein as novel, natural product inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease in vitro. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.13.038687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins A.L. Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:682–690. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu F., Ding Y., Guo Y., Liu B., Kou Z., Xiao W., Zhu J. Anti-osteoporosis effect of Epimedium via an estrogen-like mechanism based on a system-level approach. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;177:148–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao L.I., Zhang B. Traditional Chinese medicine network pharmacology: theory, methodology and application. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2013;11:110–120. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(13)60037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Y., Ding Y., Xu F., Liu B., Kou Z., Xiao W., Zhu J. Systems pharmacology-based drug discovery for marine resources: an example using sea cucumber (Holothurians) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng X.-Y., Zhang H.-X., Mezei M., Cui M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2012;7:146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ru J., Li P., Wang J., Zhou W., Li B., Huang C., Li P., Guo Z., Tao W., Yang Y., Xu X., Li Y., Wang Y., Yang L. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminf. 2014;6:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue R., Fang Z., Zhang M., Yi Z., Wen C., Shi T. TCMID: traditional Chinese medicine integrative database for herb molecular mechanism analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41 doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu H.Y., Zhang Y.Q., Liu Z.M., Chen T., Lv C.Y., Tang S.H., Zhang X.B., Zhang W., Li Z.Y., Zhou R.R., Yang H.J., Wang X.J., Huang L.Q. ETCM: an encyclopaedia of traditional Chinese medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D976–D982. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z., Guo F., Wang Y., Li C., Zhang X., Li H., Diao L., Gu J., Wang W., Li D., He F. BATMAN-TCM: a bioinformatics analysis tool for molecular mechANism of traditional Chinese medicine. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep21146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li B., Ma C., Zhao X., Hu Z., Du T., Xu X., Wang Z., Lin J., YaTCM Yet another traditional Chinese medicine database for drug discovery. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:600–610. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S., Thiessen P.A., Bolton E.E., Chen J., Fu G., Gindulyte A., Han L., He J., He S., Shoemaker B.A., Wang J., Yu B., Zhang J., Bryant S.H. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1202–D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashita F., Hashida M. Silico approaches for predicting ADME properties of drugs. Drug Metabol. Pharmacokinet. 2004;19:327–338. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.19.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu X., Zhang W., Huang C., Li Y., Yu H., Wang Y., Duan J., Ling Y. A novel chemometric method for the prediction of human oral bioavailability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:6964–6982. doi: 10.3390/ijms13066964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipinski C.A. Rule of five in 2015 and beyond: target and ligand structural limitations, ligand chemistry structure and drug discovery project decisions. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;101:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manach C., Scalbert A., Morand C., Rémésy C., Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;79:727–747. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y., Zhang H., Peng C. Puerarin: a review of pharmacological effects. Phyther. Res. 2014;28:961–975. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birt D.F., Hendrich S., Wang W. Dietary agents in cancer prevention: flavonoids and isoflavonoids. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;90:157–177. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(01)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W357–W3664. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gfeller D., Michielin O., Zoete V. Shaping the interaction landscape of bioactive molecules. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:3073–3079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bateman A. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1049. D506–D515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stelzer G., Rosen N., Plaschkes I., Zimmerman S., Twik M., Fishilevich S., Stein T.I., Nudel R., Lieder I., Mazor Y., Kaplan S., Dahary D., Warshawsky D., Guan‐Golan Y., Kohn A., Rappaport N., Safran M., Lancet D. The GeneCards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformat. 2016;54 doi: 10.1002/cpbi.5. 1.30.1-1.30.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wishart D.S., Feunang Y.D., Guo A.C., Lo E.J., Marcu A., Grant J.R., Sajed T., Johnson D., Li C., Sayeeda Z., Assempour N., Iynkkaran I., Liu Y., MacIejewski A., Gale N., Wilson A., Chin L., Cummings R., Le Di, Pon A., Knox C., Wilson M. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D., Junge A., Wyder S., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Doncheva N.T., Morris J.H., Bork P., Jensen L.J., Von Mering C. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vella D., Marini S., Vitali F., Di Silvestre D., Mauri G., Bellazzi R. MTGO: PPI network analysis via topological and functional module identification. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5499. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23672-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software Environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A.H., Tanaseichuk O., Benner C., Chanda S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bader G.D., V Hogue C.W. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinf. 2003;4:1–27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., Davis A.P., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S., Eppig J.T., Harris M.A., Hill D.P., Issel-Tarver L., Kasarskis A., Lewis S., Matese J.C., Richardson J.E., Ringwald M., Rubin G.M., Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanehisa M., Goto S., Kawashima S., Okuno Y., Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Hackl H., Charoentong P., Tosolini M., Kirilovsky A., Fridman W.H., Pagès F., Trajanoski Z., Galon J., ClueGO A Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.-H., Nitsche A. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dai W., Zhang B., Jiang X.-M., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., Xie X., Jin Z., Peng J., Liu F. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science. 2020;368(80-):1331–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towler P., Staker B., Prasad S.G., Menon S., Tang J., Parsons T., Ryan D., Fisher M., Williams D., Dales N.A. ACE2 X-ray structures reveal a large hinge-bending motion important for inhibitor binding and catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17996–18007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311191200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su H., Yao S., Zhao W., Li M., Liu J., Shang W., Xie H., Ke C., Hu H., Gao M. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities in vitro of Shuanghuanglian preparations and bioactive ingredients. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020;41:1167–1177. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0483-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robson B. COVID-19 Coronavirus spike protein analysis for synthetic vaccines, a peptidomimetic antagonist, and therapeutic drugs, and analysis of a proposed achilles' heel conserved region to minimize probability of escape mutations and drug resistance. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020;121 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu K., Borrelli K.W., Greenwood J.R., Day T., Abel R., Farid R.S., Harder E. Docking covalent inhibitors: a parameter free approach to pose prediction and scoring. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:1932–1940. doi: 10.1021/ci500118s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du A., Zheng R., Disoma C., Li S., Chen Z., Li S., Liu P., Zhou Y., Shen Y., Liu S., Zhang Y., Dong Z., Yang Q., Alsaadawe M., Razzaq A., Peng Y., Chen X., Hu L., Peng J., Zhang Q., Jiang T., Mo L., Li S., Xia Z. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, an active ingredient of Traditional Chinese Medicines, inhibits the 3CLpro activity of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;176:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iftikhar H., Ali H.N., Farooq S., Naveed H., Shahzad-ul-Hussan S. Identification of potential inhibitors of three key enzymes of SARS-CoV2 using computational approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020;122 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rameshkumar M.R., Indu P., Arunagirinathan N., Venkatadri B., El-Serehy H.A., Ahmad A. Computational selection of flavonoid compounds as inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main protease, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and spike proteins: a molecular docking study. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021;28:448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C., Liu S., Zhao P., Liu H., Zhu L., Tai Y., Bai C., Gao T., Song J., Xia P., Dong J., Zhao J., Wang F.S. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.L., Hui D.S.C., Du B., Li L.J., Zeng G., Yuen K.Y., Chen R.C., Tang C.L., Wang T., Chen P.Y., Xiang J., Li S.Y., Wang J.L., Liang Z.J., Peng Y.X., Wei L., Liu Y., Hu Y.H., Peng P., Wang J.M., Liu J.Y., Chen Z., Li G., Zheng Z.J., Qiu S.Q., Luo J., Ye C.J., Zhu S.Y., Zhong N.S. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.06.20020974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li X., Xu S., Yu M., Wang K., Tao Y., Zhou Y., Shi J., Zhou M., Wu B., Yang Z., Zhang C., Yue J., Zhang Z., Renz H., Liu X., Xie J., Xie M., Zhao J. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;146:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kong Z., Shen Q., Jiang J., Deng M., Zhang Z., Wang G. Wogonin improves functional neuroprotection for acute cerebral ischemia in rats by promoting angiogenesis via TGF-β1. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019;7 doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.10.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim J.H., Kim M.Y., Kim J.H., Cho J.Y. Fisetin suppresses macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses by blockade of Src and Syk. Biomol. Ther. 2015;23:414–420. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2015.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barh D., Tiwari S., Weener M.E., Azevedo V., Góes-Neto A., Gromiha M.M., Ghosh P. Multi-omics-based identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection biology and candidate drugs against COVID-19, Comput. Biol. Med. 2020;126 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Borba M.G.S., Val F.F.A., Sampaio V.S., Alexandre M.A.A., Melo G.C., Brito M., Mourão M.P.G., Brito-Sousa J.D., Baía-da-Silva D., Guerra M.V.F., Hajjar L.A., Pinto R.C., Balieiro A.A.S., Pacheco A.G.F., Santos J.D.O., Naveca F.G., Xavier M.S., Siqueira A.M., Schwarzbold A., Croda J., Nogueira M.L., Romero G.A.S., Bassat Q., Fontes C.J., Albuquerque B.C., Daniel-Ribeiro C.T., Monteiro W.M., Lacerda M.V.G. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nowakowska Z. A review of anti-infective and anti-inflammatory chalcones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007;42:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao L.H., Jiang Y.-M., Shi J., Tomas-Barberan F.A., Datta N., Singanusong R., Chen S.S. Flavonoids in food and their health benefits. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2004;59:113–122. doi: 10.1007/s11130-004-0049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xian Y., Zhang J., Bian Z., Zhou H., Zhang Z., Lin Z., Xu H. Bioactive natural compounds against human coronaviruses: a review and perspective. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;10:1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liskova A., Samec M., Koklesova L., Samuel S.M., Zhai K., Al-Ishaq R.K., Abotaleb M., Nosal V., Kajo K., Ashrafizadeh M. Flavonoids against the SARS-CoV-2 induced inflammatory storm. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Middleton E., Kandaswami C., Theoharides T.C. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:673–751. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ren J., Zhang A.-H., Wang X.-J. Traditional Chinese medicine for COVID-19 treatment. Pharmacol. Res. 2020;155 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ren J., Lu Y., Qian Y., Chen B., Wu T., Ji G. Recent progress regarding kaempferol for the treatment of various diseases. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019;18:2759–2776. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo Q., Zhao L., You Q., Yang Y., Gu H., Song G., Lu N., Xin J. Anti-hepatitis B virus activity of wogonin in vitro and in vivo. Antivir. Res. 2007;74:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kawabata K., Mukai R., Ishisaka A. Quercetin and related polyphenols: new insights and implications for their bioactivity and bioavailability. Food Funct. 2015;6:1399–1417. doi: 10.1039/c4fo01178c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reinhold D., Brocke S. DPP4-directed therapeutic strategies for MERS-CoV. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014;14:100–101. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70696-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dobson-Stone C., Polly P., Korgaonkar M.S., Williams L.M., Gordon E., Schofield P.R., Mather K., Armstrong N.J., Wen W., Sachdev P.S., Kwok J.B.J. GSK3B and MAPT polymorphisms are associated with grey matter and intracranial volume in healthy individuals. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spratte J., Princk H., Schütz F., Rom J., Zygmunt M., Fluhr H. Stimulation of chemokines in human endometrial stromal cells by tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ is similar under apoptotic and non-apoptotic conditions. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018;297:505–512. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Havsteen B.H. The biochemistry and medical significance of the flavonoids. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;96:67–202. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00298-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Gu X., Kang L., Guo L., Liu M., Zhou X., Luo J., Huang Z., Tu S., Zhao Y., Chen L., Xu D., Li Y., Li C., Peng L., Li Y., Xie W., Cui D., Shang L., Fan G., Xu J., Wang G., Wang Y., Zhong J., Wang C., Wang J., Zhang D., Cao B. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O'Leary K.A., de Pascual-Tereasa S., Needs P.W., Bao Y.-P., O'Brien N.M., Williamson G. Effect of flavonoids and vitamin E on cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) transcription. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2004;551:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim H.P., Son K.H., Chang H.W., Kang S.S. Anti-inflammatory plant flavonoids and cellular action mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004 doi: 10.1254/jphs.CRJ04003X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu C.P., Lusvarghi S., Hsiao S.H., Liu T.C., Li Y.Q., Huang Y.H., Hung T.H., Ambudkar S.V. Licochalcone A selectively resensitizes ABCG2-overexpressing multidrug-resistant cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:1461–1472. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hua F., Zhou P., Wu H.Y., Chu G.X., Xie Z.W., Bao G.H. Inhibition of α-glucosidase and α-amylase by flavonoid glycosides from Lu’an GuaPian tea: molecular docking and interaction mechanism. Food Funct. 2018;9:4173–4183. doi: 10.1039/c8fo00562a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ying T.H., Yang S.F., Tsai S.J., Hsieh S.C., Huang Y.C., Bau D.T., Hsieh Y.H. Fisetin induces apoptosis in human cervical cancer HeLa cells through ERK1/2-mediated activation of caspase-8-/caspase-3-dependent pathway. Arch. Toxicol. 2012;86:263–273. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0754-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim J.H., Cho I.S., So Y.K., Kim H.H., Kim Y.H. Kushenol A and 8-prenylkaempferol, tyrosinase inhibitors, derived from Sophora flavescens. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018;33:1048–1054. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1477776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lu L., Guo Q., Zhao L. Overview of oroxylin A: a promising flavonoid compound. Phyther. Res. 2016;30:1765–1774. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.He S.-M., Li R., Kanwar J.R., Zhou S.-F. Structural and functional properties of human multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1) Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;18:439–481. doi: 10.2174/092986711794839197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Margina D., Ilie M., Manda G., Neagoe I., Mocanu M., Ionescu D., Gradinaru D., Ganea C. Quercetin and epigallocatechin gallate effects on the cell membranes biophysical properties correlate with their antioxidant potential. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2012;31:47–55. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2012_005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duarte J., Francisco V., Perez-Vizcaino F. Modulation of nitric oxide by flavonoids. Food Funct. 2014;5:1653–1668. doi: 10.1039/c4fo00144c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Suri J.S., Puvvula A., Biswas M., Majhail M., Saba L., Faa G., Singh I.M., Oberleitner R., Turk M., Chadha P.S. COVID-19 pathways for brain and heart injury in comorbidity patients: a role of medical imaging and artificial intelligence-based COVID severity classification: a review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.103960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim Y.-J., Seo S.G., Choi K., Kim J.E., Kang H., Chung M.-Y., Lee K.W., Lee H.J. Recovery effect of onion peel extract against H 2 O 2 -induced inhibition of gap-junctional intercellular communication is mediated through quercetin. J. Food Sci. 2014;79:H1011–H1017. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pafumi I., Festa M., Papacci F., Lagostena L., Giunta C., Gutla V., Cornara L., Favia A., Palombi F., Gambale F., Filippini A., Carpaneto A. Naringenin impairs two-pore channel 2 activity and inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04974-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Choi J.-H., Kim Y.-S., Shin C.-H., Lee H.-J., Kim S. Antithrombotic activities of luteolin in vitro and in vivo. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2015;29:552–558. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Khalatbary A.R., Khademi E. The green tea polyphenolic catechin epigallocatechin gallate and neuroprotection. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020;23:281–294. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2018.1500124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mhatre S., Naik S., Patravale V. A molecular docking study of EGCG and theaflavin digallate with the druggable targets of SARS-CoV-2. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;129 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ngwa W., Kumar R., Thompson D., Lyerly W., Moore R., Reid T.-E., Lowe H., Toyang N. Potential of flavonoid-inspired phytomedicines against COVID-19. Molecules. 2020;25:2707. doi: 10.3390/molecules25112707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jo S., Kim S., Kim D.Y., Kim M.-S., Shin D.H. Flavonoids with inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020;35:1539–1544. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2020.1801672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kitakaze T., Makiyama A., Nakai R., Kimura Y., Ashida H. Kaempferol modulates TCDD-and t-BHQ-induced drug-metabolizing enzymes and luteolin enhances this effect. Food Funct. 2020;11:3668–3680. doi: 10.1039/c9fo02951f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.