Abstract

Introduction

Although lateral locking plate has shown promising results in distal femur fracture, there are high rates of varus collapse and implant failure in comminuted metaphyseal and articular fractures. This systematic review evaluates the functional outcomes and complications of dual plating in the distal femur fracture.

Materials and methods

Manual and electronic search of databases (PubMed, Medline Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) was performed to retrieve studies on dual plate fixation in the distal femur fracture. Of the retrieved 925 articles, 12 were included after screening.

Results

There were one randomized-controlled, four prospective and seven retrospective studies. A total of 287 patients with 292 knees were evaluated (dual plating 213, single plating 76, lost to follow-up 3). The nonunion and delayed union rates following dual plate fixations were up to 12.5% and 33.3%, respectively. The mean healing time ranged from 11 weeks to 18 months. Good to excellent outcome was observed in 55–75% patients. There was no difference between the single plate and dual plate fixation with regards to the functional outcomes (VAS score, Neer Score and Kolmert's standard) and complications. Pooled analysis of the studies revealed a longer surgical duration (MD − 16.84, 95% CI − 25.34, − 8.35, p = 0.0001) and faster healing (MD 5.43, 95% CI 2.60, 8.26, p = 0.0002) in the double plate fixation group, but there was no difference in nonunion rate (9.2% vs. 0%, OR 4.95, p = 0.13) and blood loss (MD − 9.86, 95% CI − 44.97, 25.26, p = 0.58).

Conclusion

Dual plating leads to a satisfactory union in the comminuted metaphyseal and articular fractures of the distal femur. There is no difference between the single plate and dual plate with regards to nonunion rate, blood loss, functional outcomes and complications. However, dual fixation leads to faster fracture healing at the cost of a longer surgical duration.

Keywords: Supracondylar femur fracture, Comminution; metaphysis, Periprosthetic fracture, Locking plate, Medial plate, Distal femur plate, Double plate

Introduction

Distal femoral fractures represent 3–6% of femoral fractures and 0.4% of all fractures [1]. It has a bimodal age distribution with typical occurrence in the young individuals (around 20 years old, traffic or sport) and the older women (around 70 years old, fall at home, osteoporosis) [2, 3]. Surgical fixation in these fractures aims to achieve anatomical articular reduction, preservation of the blood supply, and rigid internal fixation to start early mobilization [3]. Although lateral locking plates can address these issues and are commonly used for such fractures, the nonunion rate can go up to 18–20% [3, 4]. The metaphyseal comminution, poor bone quality, and inadequate fixation lead to varus collapse and nonunion [5]. Augmentation of the lateral locked plate construct with a medial plate reduces the chances of failure [6–8].

The major concerns for medial plating are unfamiliar approach, proximity to the neurovascular bundle and belief among surgeons that it would compromise the medial vascularity. However, a recent study has abolished the concept of vascularity compromise with dual plating [9]. Rollick et al. reported that there was a 21.2% total reduction in the distal femoral arterial contribution after fixation with a lateral locked plate via lateral sub-vastus approach; however, a supplementary medial reconstruction plate (3.5 mm) fixation lead to a 25.4% total reduction in the vascularity [9]. It is evident that the majority of vascular insult secondary to open reduction and internal fixation of the distal femur occurs because of lateral locked plating and not from the addition of a medial plate. Other studies have also reported that there is a safe medial interval (up to about 16 cm proximal to the adductor tubercle) for plating with little danger to the femoral artery, nerve and their branches [10–12].

In addition to the lateral distal femoral plate, medial plating was first reported by Sander's et al. in 1991 [13]. They reported union all their patients who had a complex intraarticular fracture (C2, C3). Subsequently, multiple small cases series reported a satisfactory result [14–25]. Dual plating stabilizes both the columns of the distal femur and provides a stronger fixation in comminuted supracondylar femur fractures, low periprosthetic fracture and nonunions [25–29]. However, it is not recommended routinely for these fractures as the superiority to traditional lateral locked plating is not proven with regards to union rate, functional outcomes, and complications [3, 23]. Therefore, this systematic review was designed to evaluate the available literature on dual plating in distal femur fracture and compare the functional outcomes and complications with the single lateral locked plate.

Materials and Methods

Searches of Database

The guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) were followed to report this systematic review [30]. This study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021230418). Electronic searches of the medical literature databases including PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were done by three authors (SKT, PV, and NPM) on December 1, 2020. The following keywords were used in different combinations using Boolean operators: distal femur fracture, supracondylar femur fracture, single plating, lateral locking plate, dual plating, double plate, distal femur plating, and medial femoral plating. The search was limited to the English language and human beings (Table 1). The abstract of the retrieved articles was assessed to look for possible inclusion in the study. If the abstract was inadequate to give detailed information, the full text was extracted. Bibliographic details of the selected studies were manually searched to retrieve more articles. Any discrepancies in study inclusion were discussed among the authors, and a fourth author was consulted in case of disagreement.

Table 1.

Search strategy of PubMed database

| Keywords | Search strategy | No. of hits |

|---|---|---|

| Distal femur fracture, supracondylar femur fracture, single plating, dual plating, lateral locking plate, double plate, medial femoral plating Filters: Humans, English | ((("distal"[All Fields] OR "distalization"[All Fields] OR "distalize"[All Fields] OR "distalized"[All Fields] OR "distalizer"[All Fields] OR "distalizers"[All Fields] OR "distalizes"[All Fields] OR "distalizing"[All Fields] OR "distally"[All Fields] OR "distals"[All Fields]) AND ("femoral fractures"[MeSH Terms] OR ("femoral"[All Fields] AND "fractures"[All Fields]) OR "femoral fractures"[All Fields] OR ("femur"[All Fields] AND "fracture"[All Fields]) OR "femur fracture"[All Fields])) OR ("supracondylar"[All Fields] AND ("femoral fractures"[MeSH Terms] OR ("femoral"[All Fields] AND "fractures"[All Fields]) OR "femoral fractures"[All Fields] OR ("femur"[All Fields] AND "fracture"[All Fields]) OR "femur fracture"[All Fields]))) AND ((("single person"[MeSH Terms] OR ("single"[All Fields] AND "person"[All Fields]) OR "single person"[All Fields] OR "single"[All Fields] OR "singles"[All Fields]) AND ("bone plates"[MeSH Terms] OR ("bone"[All Fields] AND "plates"[All Fields]) OR "bone plates"[All Fields] OR "plate"[All Fields] OR "plate s"[All Fields] OR "plated"[All Fields] OR "plates"[All Fields] OR "plating"[All Fields] OR "platings"[All Fields])) OR ("dual"[All Fields] AND ("bone plates"[MeSH Terms] OR ("bone"[All Fields] AND "plates"[All Fields]) OR "bone plates"[All Fields] OR "plate"[All Fields] OR "plate s"[All Fields] OR "plated"[All Fields] OR "plates"[All Fields] OR "plating"[All Fields] OR "platings"[All Fields])) OR (("functional laterality"[MeSH Terms] OR ("functional"[All Fields] AND "laterality"[All Fields]) OR "functional laterality"[All Fields] OR "laterality"[All Fields] OR "lateral"[All Fields] OR "lateralisation"[All Fields] OR "lateralisations"[All Fields] OR "lateralise"[All Fields] OR "lateralised"[All Fields] OR "lateralises"[All Fields] OR "lateralising"[All Fields] OR "lateralities"[All Fields] OR "lateralization"[All Fields] OR "lateralizations"[All Fields] OR "lateralize"[All Fields] OR "lateralized"[All Fields] OR "lateralizes"[All Fields] OR "lateralizing"[All Fields] OR "laterally"[All Fields] OR "laterals"[All Fields]) AND ("locked"[All Fields] OR "locking"[All Fields] OR "lockings"[All Fields] OR "locks"[All Fields]) AND ("bone plates"[MeSH Terms] OR ("bone"[All Fields] AND "plates"[All Fields]) OR "bone plates"[All Fields] OR "plate"[All Fields] OR "plate s"[All Fields] OR "plated"[All Fields] OR "plates"[All Fields] OR "plating"[All Fields] OR "platings"[All Fields])) OR (("double"[All Fields] OR "doubled"[All Fields] OR "doubles"[All Fields] OR "doubling"[All Fields] OR "doublings"[All Fields]) AND ("bone plates"[MeSH Terms] OR ("bone"[All Fields] AND "plates"[All Fields]) OR "bone plates"[All Fields] OR "plate"[All Fields] OR "plate s"[All Fields] OR "plated"[All Fields] OR "plates"[All Fields] OR "plating"[All Fields] OR "platings"[All Fields])) OR (("medial"[All Fields] OR "mediale"[All Fields] OR "mediales"[All Fields] OR "medialisation"[All Fields] OR "medialise"[All Fields] OR "medialised"[All Fields] OR "medialization"[All Fields] OR "medializations"[All Fields] OR "medialize"[All Fields] OR "medialized"[All Fields] OR "medializes"[All Fields] OR "medializing"[All Fields] OR "medially"[All Fields] OR "medials"[All Fields]) AND ("femor"[All Fields] OR "femorals"[All Fields] OR "femur"[MeSH Terms] OR "femur"[All Fields] OR "femoral"[All Fields]) AND ("bone plates"[MeSH Terms] OR ("bone"[All Fields] AND "plates"[All Fields]) OR "bone plates"[All Fields] OR "plate"[All Fields] OR "plate s"[All Fields] OR "plated"[All Fields] OR "plates"[All Fields] OR "plating"[All Fields] OR "platings"[All Fields]))) | 235 |

Study Eligibility Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were proposed for this review: (1) the patients must have undergone distal femur plating by both medial and lateral plates, (2) The study can be a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or prospective study or retrospective study, (3) The study must have evaluated the union and clinical outcome after dual distal femur plating, (4) The study must have reported at least six months of follow-up or till radiographic union. The following studies were excluded: (1) pediatric distal femur fractures, (2) pathological fractures.

Outcome Measures

The primary objectives of this review were to compare the time to surgery from injury, incision and implants used, blood loss, mean operative time, time for healing, range of motion (ROM) and functional outcome. The secondary objectives were to look for complications and reoperations.

Data Collection

Data extraction (author, year of publication, study design, intervention, follow-up and outcome) was done by using a data extraction form by two authors (SKT, PV). The opinion of a third author was sought in case there was any disagreement between the authors.

Study Quality Assessment

The methodological quality and risk of bias of the studies were assessed by two authors (SKT and PV) individually using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (mCCS) [31]. The mCCS has two parts; part A has seven scales (study size, mean follow-up, surgical approach, type of study, description of the diagnosis, description of surgical technique, description of preoperative rehabilitation), and part B has two scales (outcome criteria and procedure of assessing the outcomes). Each of these scales has subscales with different allocated points. The total score ranges from 0 to 100, with a score of 100 indicating the highest study quality.

As per the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine [32], there were six retrospective case series (level IV evidence), one retrospective comparative study (level III), five prospective randomized-controlled and prospective cohort studies (level I and II).

Statistical Analysis

The extracted data from the comparative studies were analyzed using Review Manager (RevMan) V.5.3 [33]. For binary data, the odds ratio (OR) and for continuous data, mean difference (MD) or standard mean difference (SMD) was calculated. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The heterogeneity among the studies was assessed by Cochrane's Q (χ2 p < 0.10) and quantified by I2. I2 of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [34].

Results

Figure 1 shows the detailed steps for the literature search. A total of 925 studies were retrieved after manual and electronic searches, of which 12 studies were found to be eligible for review (Fig. 1). There were one randomized-controlled, four prospective and seven retrospective studies. There were three comparative studies between the single plate and dual plate groups. The demographic profiles, surgical details and inclusion–exclusion criteria have been provided in Tables 2 and 3. The 12 studies included a total of 292 knees (287 patients) (dual plating group 213, single plating group 76, lost to follow-up 3). The number of female patients was higher than male patients (male 113, female 174).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram showing methods of study recruitment

Table 2.

Demographic profiles of the included studies

| Study | Study design | No. of fracture (no of patients) | Age (range) in years |

Gender (M: F) | Associated injuries (%) | Obesity, smoking & comorbidities (%) | Fracture type | Intervention | Meantime to surgery | Mean follow-up (range) in months | mCCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanders 1991, USA | Retrospective study | 9 | 39.4 | 3:6 | – | – |

GA classification Closed:4 Open:5 (Gr II:2, Grade III:3) Muller's classification Type C2.3: 4 Type C3.3: 5 |

Condylar buttress plate on the lateral side and one medial plate | – | 26 (21–34) | 51 |

| Chapman 1999, USA | Retrospective study | 13 | 45.6 (25–81) | 5:8 | – | – |

GA classification Closed; 2 Open; 8 ( Gr IIIA: 7, IIIC: 1) Osteotomy: 3 Muller's classification Type A1: 1 Type A2; 1 Type A3: 2 Type C2: 3 Type C3: 1 Unknown/NA: 5 |

Lateral plate: 95° DCS/dome plunger screw 7, Condylar buttress plate 4, DCP/Alta broad plate 2 Anteromedial plate: DCP/Alta side plate in all |

15 (5–36 mo) | 28.38 (6–120) | 50 |

| Ziran et al. 2002, USA | Retrospective study | 36 (35 pts) | – | 21:14 | – | – |

GA classification Closed: 24 Open: 12 (Gr I: 4, Gr IIIA: 5, Gr IIIB: 1, Gr IIIC: 2) Muller's classification C2: 16 C3: 19 (two died, one lost to fu, two developed infection-one amputation) |

Lateral: blade plate 18, condylar plate 18 Anteriorly: reconstruction plate 10, DC plate 25 |

– | 7.7 (3–44) | 54 |

| Khalil 2012, Egypt | Prospective study | 12 | 33.5 (22–44) | 8:4 |

Minor head injuries– 5 (41.7%) Chest injuries –10 (83.3%) Abdominal injuries– 7 (58.3%) Upper limb injuries– 4 (33.4%) Ipsilateral lower limb injuries– 2 (16.7%) Contralateral lower limb injuries –4 (33.40%) Stable pelvic fractures– 5 (41.7%) Stable spinal fractures 3 (25%) Knee derangement–5 (41.7%) |

Overweight 5 (41.6%), Obese 2 (16.6%) Heavy smokers 5 (41.6%) |

GA classification Closed: 12 Muller's classification C3:12 Associated Hoffa: 7 (lateral 4, medial 3) |

Lateral: locked plate Medial: Contoured medial plate (reconstruction plate in 8, semitubular plate in 4) |

First week:8 2 wks:4 |

13.7 (11–18) | 54 |

| Dugan 2013, USA | Retrospective study | 15 (14 pts) | 41 (16–75) | 8:7 | All pts had multisystem injury (ISS ≥ 16) | – |

GA classification: All open fracture Grade IIIA: 10 Grade IIIB: 5 AO classification: Type C2: 7 Type C3: 8 |

1st stage: debridement + lateral locked plate + antibiotic beads 2nd stage: removal of beads and application of medial plate (small fragment combi-holes) + bone grafting/bone graft substitute |

1st stage: < 24 h Second stage: 3.6 mo (1–6 mo) |

Till radiographic union (4mo) | 46 |

| Holzman 2016, USA | Retrospective study | 23 (22 pts) | 58 (35–83) | 6:16 | – |

Obese 6 (27%) Smoker 7 (43.75%) Hypertension 11 (50%) Stroke 2 (9%) COPD 2 (9%) CVD 4 (18%) Mood disorder 7 (32%) Type 2 DM 2 (9%) Asthma 4 (18%) Osteoarthritis 5 (23%) Infected fracture site 1 (4.5%) Multiple myeloma 1 (4.5%) |

23 nonunion: atrophic 21 oligotrophic 2 (well-fixed, stable lateral locking plate with a satisfactory soft tissue envelope: 16 Failed lateral plate: 7 GA classification (initial injury) Closed 14 (13 pts) Open 8 |

Lateral: locked plate (previous fixed stable plate 16, revision of plate 7), Medial: medial locked plate |

16 mo | Median 18 (6–94) | 46 |

| Steinberg 2017, Israel | Retrospective study | 32 | 76 (44–101) | 6:26 | – | – |

22 acute fracture, 2 nonunion, 8 periprosthetic fracture GA classification Closed 33 Open 1 Muller's classification (24) Type A2: 1, Type A2: 2, Type A3: 7, Type C1: 4, Type C2: 7, Type C3: 3 Rorabeck-Taylor classification (8) Type 1: 1, Type 2: 7 |

Lateral locked plate and medial locked/LCDCP | 3.8 days (range, 0–11 days) | 12 | 58 |

| Imam 2017, Egypt | Prospective study | 16 | 36 ± 12.4 (18–59) | 11:5 |

Pelvic fracture 1 (6.25%) Cervical fracture 1 (6.25%) |

Overweight/obese 6 (37.5%) Smokers 7 (43.75%) Diabetes mellitus 2 (12.50%) Chronic liver disease 2 (12.50%) Hypertension 3 (18.75%) |

Muller’s/OTA classification Type C3: 16 |

Lateral locked plate with a low-contact-locked medial plate |

– | 11.5 ± 4.7 (6–24) | 60 |

| Bai 2018, China | Prospective study |

Total 60 (58 pts) Single plate: 48 Dual plate: 12 |

Single plate: ≤ 30 y: 8 (16.7%) 31–40 y: 8 (16.7%) 41–50 y: 10 (20.8%) ≥ 51 y: 22 (45.8%) Dual plate: ≤ 30 y: 1 (8.3%) 31–40 y: 4 (33.3%) 41–50 y: 4 (33.3%) ≥ 51 y: 3 (25.0%) |

Single plate-23:25 Dual plate–6:6 |

Single plate: 1 extra-location fracture 10 (20.8%) > 2 extra locations fracture 13 (27.1%) Double plate: 1 extra location fracture 2 (16.7%) > 2 extra locations fracture 0 |

– |

GA classification Single plate: Closed 23 (48.0%) Open Gr I: 9 (18.8%) Gr II: 11 (22.9%) Gr III: 5 (10.4%) Vascular injury 2 Combined external fixator: 7 Dual plate: Closed 1 (8.3%) Gr I: 5 (41.7%) Gr II: 5 (41.7%) Gr III: 1 (8.3%) Combined external fixator: 1 |

Single plate: Lateral locked plate Dual plate: lateral locked plate and medial anatomical plate or upper limb compression plate |

Single plate: 11 d Dual plate: 12 d |

15.9 | 73 |

|

Muller's/ AO-OTA classification Single plate: Type-A: 16 Type-B: 6 Type-C:26 Dual plate: Type-A: 0 Type-B: 0 Type-C: 12 |

|||||||||||

| Metwaly 2018, Egypt | Prospective cohort study | 23 | 69.6 (61–80) | 4:19 | Polytrauma excluded |

Smokers-2 (8.69%) DM- 15 (65.21%) ISHD on clopidogrel -7 (30.4%) COPD- 2 (8.69%) CLD- 5 (21.7%) |

AO-OTA Type 33-A3: 3 Type 33-C1: 2 Type 33-C2: 13 Type 33-C3: 5 |

Lateral and medial locked plate | 5 days | 14.1 | 64 |

| Zhang 2018, China | Prospective randomized study |

32 (fu of 29 pts, 3 lost to fu) Single plate 15, dual plate 14 |

Single plate: 57.93 ± 13.60 Dual plate: 59.07 ± 14.58 |

10:19 | Polytrauma excluded | NM |

Single plate Type A2/A3- 6 /9 Double plate Type A2/A3-5 /9 |

Single plate: 15 (lateral locked plate) Dual plate: 14 (lateral locking plate with medial DCP) |

– | 12 mo (29 pts, one from single plate and 2 from dual plate lost to fu) | 73 |

| Bologna 2019,USA | Retrospective study |

Total 21 Single plate 13, Dual plate 8 |

61 Single plate 54 (46–76) Dual plate 66.5 (55–78) |

2:19 | – |

Single plate: BMI 27.0 (24–30) Tobacco 5 (38%) DM 2 (15.4%) Dual plate: BMI 29.5 (28.5–32) Tobacco 3 (37.5%) DM 2 (25%)) |

GA classification Open 5 (single plate 4, dual plate 1) Muller's / AO-OTA classification: 33-C2: 7 (single plate 4,dual plate 3) 33-C3: 7 (single plate 5, dual plate 2) Periprosthetic fractures-7 (single plate 4, dual plate 3) |

Single plate 13 (lateral locked plate) Dual plate 8 (Lateral and medial locked plate) |

– |

12 (6–29) Single plate: 8 (6–15) Dual: 13 (11–22) |

46 |

Pts patients, Fu follow-up, GA Gustillo–Anderson Classification, CLD chronic liver disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DM diabetes mellitus, ISHD ischemic heart disease, BMI body mass index, DCP dynamic compression plate, LCDCP low-contact dynamic compression plate

Table 3.

Indications, surgical techniques and intraoperative parameters

| Study | Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Incision/implant | Bone graft (%) | Blood loss (ml) | Operative time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanders 1991, USA | Supracondylar fracture with intracondylar extension (> 18 years, C2.3, C3.3) |

Incision: single-incision by tibial tubercle osteotomy 2, double incision (lateral and medial approach) Implant: seven lateral condylar buttress plate and medial plate |

Bone graft from the iliac crest applied in all patients (100%) | – |

A single incision with TT osteotomy: 6 h 25 min (385 min) Dual incision: 6 h (360 min) Two-stage surgery: 3 h 30 min for lateral plate and 2 h 30 min for medial plate |

| Chapman 1999, USA | Supracondylar femur fracture nonunion following fracture or osteotomy (≥ 5 mo to 36 mo) |

Incision: anterior parapatellar approach of Henry 10, lateral approach 3 Implant: Lateral: 95° DCS/dome plunger screw 7, condylar buttress plate 4, DCP/Alta broad plate: two Anteromedial plate: DCP/Alta side plate in all |

Bone graft from the iliac crest applied in all patients (100%) | – | – |

| Ziran et al. 2002, USA | Displaced C2 and C3 (AO classification) distal femoral fractures |

Incision: anterior approach (lateral parapatellar approach) Implant: 18 blade plates and 18 condylar plates used laterally, ten reconstruction and 25 DC plates used anteriorly |

Bone grafting with allograft and demineralized bone matrix (DBM) was used in all but eight femurs | – | – |

| Khalil 2012, Egypt | Polytrauma, closed, comminuted distal femur fractures (C3) |

Incision: modification of the extensile olerud approach, (with TT osteotomy) Implant: contoured medial plate (reconstruction plate in 8, semitubular plate in 4) |

Augmentation of the bony defects by bone grafting (iliac) in all | – | – |

| Dugan 2013, USA | Polytrauma, open fractures, staged procedure, comminuted distal femur fracture (C, C3) |

Incision: extensile anterior approach as described by Henry Implant: lateral locked plate and medial side small fragment combi-holes |

Autologous graft from iliac crest/other sites in obese pts)BMP-2/BMP-7, in some cases additional allograft chips applied | – | – |

| Holzman 2016, USA | Distal femoral fracture nonunion, defined as an unhealed fracture with no radiographic signs of osseous union at a mean of 16 months following previously surgery with lateral plate |

If the lateral plate was stable: medial locking plate through the medial parapatellar approach If lateral plate had failed: two-stage reconstruction. First, the lateral plate was removed and a new lateral locking plate fixed through the lateral approach. Second, consisted of medial locked plating and bone grafting through medial parapatellar approach (median after 91 d) |

Autogenous BG (16 PICBG, 6 RIA) in 21 pts (91.3%, additional BMP-7 in 4 and BMP-2 in 2), 2 DBM(8.69%) | – | – |

| Steinberg 2017, Israel |

Non–union, nonunion following hardware failure, poor bone quality, Type A3, C3, according to AO/OTA classification and very low supracondylar and periprosthetic fractures |

Incision: double incision (lateral and medial) Implant: lateral locked plate, medial locked/ non-locking plate |

– | – | – |

| Imam 2017, Egypt |

Patients > 18 years, presenting with type C3 distal femoral fractures, with no absolute medical contraindications to surgery, without associated neurovascular compromise prior to surgery Patients with preoperative neuromuscular compromise in the symptomatic extremity, and those presenting with other types of distal femoral fractures or pathological fractures were excluded |

Incision: extended anterior incision (medial parapatellar) Implant: lateral distal femoral locked plate with a countered medial plate non-locking (proximal tibial plate in ten cases and distal tibial plate in six cases) |

Bone grafting (iliac) required in 10 cases (62.5%), small articular osteochondral fragment fixation was performed using surgical sutures or mosaicplasty (12.5%, 2/16) | 565.6 ± 99.5 (400–750) |

213.6 ± 25.8 min (160–260) |

| Bai 2018,China | Fractures within 9 cm of the articular surface of distal femoral(open/closed), (C1, C2 and C3) |

Single plate: Lateral locked plate through the anterolateral incision Double plate: medial and lateral incision. Lateral locked plate and anatomical plate on the medial side of the distal femur or upper limb compressing plate |

Single plate: 19 (40.4%) bone grafting-autogenous iliac bone 2 (4.2%), artificial bone 15 (31.3%), combined bone grafting 2 (4.2%) Double plate: 11 (91.7%) bone grafting- autogenous iliac bone 7 (58.3%), artificial bone 1 (8.3%), combined bone grafting 3 (25.0%) (p = 0.002) |

Single plate: 513 Double plate: 814 (p = 0.270) |

Single plating 145 min Double plating 180 min (p = 0.170) |

| Metwaly 2018, Egypt |

Osteoporotic geriatric patients (> 60yrs) with isolated distal femoral fractures were included Poly traumatized, open fractures, fractures type 33-A1, 33-A2, and 33-B were excluded |

Incision: midline anterior skin incision was done followed by either a medial or lateral parapatellar approach Implant: locked lateral distal femoral plate and medial locked plate |

No primary grafting, autologous bone graft needed in 4 (17.4%) cases after 6 months for showing no signs of union progression | – |

148 min (117–193 min) |

| Zhang 2018, China |

AO/OTA 33A2, 33A3 in adult patients, were included Exclusion criteria: polytrauma, pathological fracture, malignancy-related fracture, periprosthetic fracture |

Single plate group: lateral distal femur locking plate Double plating group: lateral and medial incision (through minimal dissection of vastus medialis), lateral locking plate with medial DCP |

– |

Single plate group: 220.00 ± 45.51 Double plate group: 228.57 ± 50.81 (p = 0.636) |

Single plate group: 88.00 ± 13.99 min Double plate group: 104.29 ± 9.39 min (p = 0.001) |

| Bologna 2019,USA |

Patients > 18 years of age with distal femur fracture (AO/OTA 33–C2/ 33–C3 or periprosthetic fracture with significant metaphyseal comminution) and at least 6 months of follow-up Patients with simple fracture patterns, alternative fixation methods, and inadequate follow-up were excluded |

Single plating: lateral distal femoral locking plate using a lateral approach Dual plating: extensile parapatellar approach, Lateral locked plate, a straight locking plate contoured to the medial surface |

– | – | – |

D days, weeks weeks, mo months, MUA manipulation under anesthesia, ORIF open reduction and internal fixation, HO heterotopic ossification

Study and Patient Characteristics

Three studies compared the single plate with dual plate [21, 23, 24]; the remaining nine studies evaluated the outcomes of dual plating only [13–20, 22]. The patients recruited in the studies were mostly young and middle-aged (> 16 years), whereas Metwaly et al. recruited only the geriatric distal femur fracture with age > 60 years [22]. The mean age in the study by Steinberg et al. was also 76 years indicating the elderly fracture cohort predominately[19]. Only one study did not mention the age of the patients [15]. The patients in both single pate and dual plate groups were homogenous with regards to age, gender, BMI, other baseline characters and associated injury in the operated knee. There were more female patients than males in eight studies (Table 2).

Ten studies recruited patients with acute fracture [13, 15–17, 19–24] and two studies included distal femur nonunion [14, 18]. The study by Dugan et al. included only open fractures where the debridement, antibiotic bead application and lateral plate fixation was performed in the first stage, and the medial plate application with bone grafting was performed in the second stage [17]. The nonunion was defined as an unhealed fracture with no radiographic signs of the osseous union after a mean follow-up of 16 months following previous surgery with lateral plate only. The study by Zhang et al. [23] excluded periprosthetic distal femur fracture, whereas Steinberg et al. [19] and Bologna et al. [24] included periprosthetic fractures. Other studies did not mention it (probably no periprosthetic fracture). Khalil et al. [16] and Dugan et al. [17] exclusively studied the polytrauma patients who had closed fractures and open fractures, respectively. However, Metwaly et al. [22] and Zhang et al. [23] had excluded polytrauma patients from their study. The associated head, chest and abdominal injuries in polytrauma patients were varying from 41 to 83%. Bai et al. noted an increased incidence of multiple associated fractures (> 2) in the single plating group compared to dual plating [21]. Imam et al. [20], Zhang et al. [23] and Steinberg et al. [19] excluded pathological fracture from their study, whereas other studies didn't mention about this. The indications of dual plating were comminuted articular or metaphyseal distal femur fractures, periprosthetic fracture with significant metaphyseal comminution, geriatric fracture and nonunion. The dual plating was preferred for C2, C3, A2 and A3 fractures (Muller/AO classification) in the recruited studies.

Time to Surgery from Injury, Incision, Implants and Bone Graft Used

Four studies included patients who were operated on within two weeks from the injury [16, 19, 21, 22], whereas two studies included distal femur nonunion with a mean time from injury to surgery of > 5 months [14, 18]. The remaining studies did not mention the time from injury to surgery. Dugan et al. operated through a staged procedure [17]. The first stage of debridement and lateral plate fixation was performed within 24 h, and the second stage of medial column fixation was done after 3.6 months.

Two incisions were used for dual plating in five studies [13, 18, 19, 21, 23]. A single midline incision was used in eight studies [13–17, 20, 22, 24], out of which three studies used tibial tubercle osteotomy [13, 16, 17]. Holzman et al. [18], in their study on double plating for distal femur nonunion, used a single-stage medial approach if the previous lateral distal femur plate was intact. The authors performed a two-stage procedure if the lateral plate had failed, including plate removal and lateral plate fixation in the first stage and medial plating with bone grafting in the second stage. Similarly, Dugan et al. fixed the lateral plate in the first stage of debridement and medial plate during the second stage after a mean period of 3.6 months when soft tissue has healed and infection is controlled [17]. All studies published after 2002 used a distal femur locking plate on the lateral side, but the fixation on the medial side was performed using different plates ranging from countered non-locking plates to anatomical medial locking plates. The medial plates used in the studies were dynamic compression plate (DCP), low contact dynamic compression plate (LCDCP), countered reconstruction plate, countered semitubular plate, anatomical medial locked plate, countered proximal tibial plate, countered distal tibial plate, anatomical non-locked medial plate, upper limb compression plate and straight locking plate countered to the medial side. The recent studies preferred putting a locking plate on the medial side and a lateral locked plate (Fig. 2) [18, 22, 24].

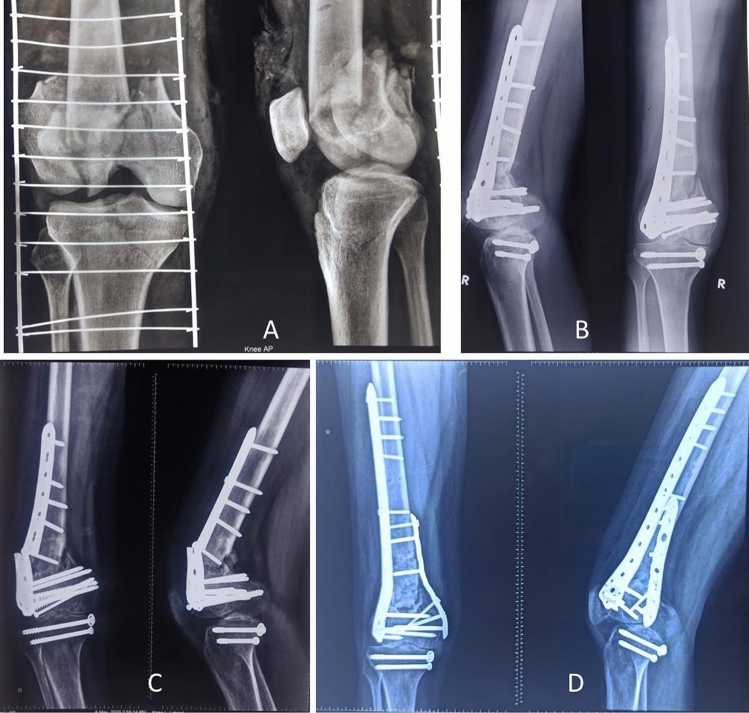

Fig. 2.

A, 41-year-male with comminuted distal femur fracture (C3); B 3 months after open reduction and internal fixation with lateral locked plate, the fracture didn't unite; C, 7 months later, he was referred to us with distal femur nonunion and broken implant; D; Four months after dual plating (lateral and medial locked plate) the fracture united, but the patient had restricted range of motion

Eight studies used primary bone grafting/ bone graft substitutes along with dual plating [13–18, 20, 21]; one study (Metwaly et al. [22]) used it after six months for no signs of the progressive union as a secondary procedure, and three studies did not mention about bone graft [19, 23, 24]. The autogenous bone graft was harvested from the iliac crest in all eight studies [13–18, 20, 21]. The reamer-irrigator-aspirator (RIA) system was used for harvesting the graft in one study [18]. One study (Ziran et al.) used allograft mixed with DBM [15], and four studies used bone morphogenic protein (BMP), DBM or artificial bone [15, 17, 18, 21]. Bai et al. noted significantly increased use of bone graft in the dual plate group (91.7%) compared to the single plate group (40.4%) [21].

Blood Loss and Mean Operative Time

Three studies [20, 21, 23] mentioned intraoperative blood loss (mean blood loss in dual plating ranged from 228 to 814 ml), and five studies reported the mean operative time [13, 20–23]. The mean time for dual plating was ranging from 104 to 385 min. Bai et al. [21] and Zhang et al. [23] compared the blood loss and operative time between single and double plate groups. There was no significant difference between these two groups in mean intraoperative blood loss (Bai et al. [21] 513 vs 814 ml, p-value 0.270; Zhang et al. [23] 220 vs 228 ml, p-value 0.636). The study by Zhang et al. [23] reported a significant difference in operative time between the single plate and double plate groups (88 min vs 104 min, p = 0.001); however, Bai et al. [21] found no significant difference in mean operative time between the groups (140 min vs 180 min, p = 0.170).

Pooled analysis of the studies did not find a significant difference in blood loss between single and double plate fixations (MD − 9.86, 95% CI − 44.97, 25.26, p = 0.58, I2 = 14%); however, the surgical duration was significantly high in the double plate fixation group (MD − 16.84, 95% CI − 25.34, − 8.35, p = 0.0001, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot diagram shows the nonunion rate, blood loss, surgical duration and healing time between the single plate fixation and double plate fixation group

Nonunion, Delayed Union, Time for Healing and Range of Motion (ROM)

The nonunion rate following dual plating in distal femur fracture was ranging from 0 to 12.5%, and the incidence of the delayed union was up to 33.3% (Table 4). However, pooled analysis of three studies comparing single plate vs double plate did not show any difference in the nonunion rate (9.2% vs 0%, OR 4.95 [95% CI 0.62–39.83], p = 0.13) (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Functional outcomes and complications

| Study | Nonunion/ delayed union (%) | Time for healing | Hospital stay | ROM % | Pain, walking ability, return to work (%) | Axial alignment/ malunion (%) | Functional score (%) | Complications (%) | Reoperations (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanders 1991, USA |

NU 0 DU 0 |

6.7 mo (5–9 mo) |

< 90°: 3 (33.3%) 90–100°: 5 (55.5%) > 100°: 1 (11.1%) Flexion contracture of 5° in 4 pts (44.4%) |

Pain: 1 pain free (11.1%), 6 occasional pain (66.6%), 2 pain on walking (22.2%), no one had pain at rest Walking: 1 unlimited (11.1%), 7 for 30–60 min (77.7%), 1 for 15 min (11.1%) (3 with cane support) Work: 1 joined back (11.1%), 5 changed (55.5%), 2 needed assistance at home (22.2%) and one had neurological problem sec to HI (11%) |

Intra op: anatomical reductions 7 (77.7%), non-anatomical reductions 2 (22.2%) Deformity after healing: posterior angulation of 5° 1 (11.1%) |

Sanders score Good-5 (55%) Fair-4 (45%) Partial wt bearing with cane 8 (88.8%) Complete wt bearing 1 (11.1%) |

- No loosening or failure of the plates occurred. There were no wound complications |

||

| Chapman 1999, USA |

NU 1 (7.69%) DU 0 |

8.38 mo (4–20 mo) | 1.3°(5–7°) to 102°(10–135°) |

Return to full activity 6 (46.1%) Walker/crutches/LLD/vocational rehab: 5 (38.5%) NM 2 (15.4) |

Loss of 30° flexion: 1 (7.69%) Infection: 1 (7.69%) Loosening, proximal plate; 15-degree varus Malunion: 1 (7.69%) |

Reoperation 4 (30.8%) | |||

| Ziran 2002, USA |

NU 3 (8.3%) DU 0 |

24/36 healed in 16 wks |

5° (5°–35°) to 100° (20°–130°) flexion |

Reductions were near anatomic (< 2 mm step-off, < 5° varus, and < 1 cm shortening) in all but 3 pts |

Knee stiffness 5 (13.8%) Reoperation 3 (8.3%) Infection 1 (2.7%) |

MUA 5 (13.8%) Reoperation 3 (8.3%) |

|||

| Khalil 2012, Egypt |

NU 0 DU 4 (33.3%) |

18.3 weeks (12–28 wks), Tibial tuberosity osteotomy healing time 10.5 wks |

Restricted knee motions in five cases (≤ 110°) (41.6%) |

Pain and walking: pain of variable degree and walking disability in three patients (25%) Work: Change of work in 4 pts (33.3%) |

Reductions were near Anatomic (< 2 mm step-off, < 5° varus, and < 1 cm shortening) in all patients |

Sanders score Excellent 2 (16.7%) Good 5 (41.7%) Fair 3 (25%) Poor 2 (16.7%) |

Superficial Infection: 2 (16.7%) Delayed wound healing: 2 (16.7%) Delayed tibial tuberosity osteotomy healing for > 12 wks: 2 (16.7%) Severe knee stiffness (≤ 95°): 2 (16.7%) Pain in iliac crest donor site 3 AP laxity of knee 5 |

Quadricepsplasty: 2 (16.7%) MUA: 2 (16.7%) |

|

| Dugan 2013, USA |

NU 0 DU 0 |

4 mo (2–8 mo) | – | 2° (0–10) to 88° (40°–120°) | – |

Immediate postop: tibiofemoral angle 4.8° (1 to 11°) After healing: 5° (6 to 13°) |

– | Knee stiffness, but the exact number not mentioned | – |

| Holzman 2016, USA | NU 1 (4.3%) |

12 months after the medial locking plate surgery |

Complete /partial wt bearing: 19 pts (20 NU fu) (86.36%) Independent ambulation: 13 (59%) Support of a cane or walker/wheelchair: 5 (22.72%) Wheelchair ambulator owing to multiple myeloma: 1 (4.54%) |

6 complications (26%) Symptomatic medial plate 2 (8.6%) Symptomatic medial and lateral plate 1 (4.34%) Non-healing surgical Incision, knee Arthrofibrosis, Symptomatic medial and lateral plate: 1 (4.34%) Skin breakdown of BG harvest site: 1 (4.34%) Persistent nonunion with broken lateral plate 1 (4.34%) |

Implant removal-4 (18%), one pt had associated Quadricepsplasty (4.34%) | ||||

| Steinberg 2017, Israel |

NU 2 (6.25%) DU 1 (3.1%) |

Radiographically- mean of 12 weeks (range, 6 to 21 weeks) and clinically within 11 weeks (range, 6–17 weeks) | 11.6 d |

Flexion: 85°–120° Extension: 0–20° |

8° valgus in one patient (3.12%) |

Delayed union-1 (3.1%) (Re-surgery with BG) Shaft #(re-surgery with a longer plate) Superficial infection 2 (6.2%) Deep infection 1 (3.1%) |

5 (15.62%) (wound complications 3 (9.3%), delayed union 1 (3.1%), shaft fracture 1 (3.1%)) |

||

| Imam 2017, Egypt |

NU 2 (12.5%) DU 1 (6.25%) |

Radiological union time was 6.0 ± 3.5 mo (3–14 mo) |

114.6° ± 21.8° Range 70°–140° |

Normal alignment No varus/valgus |

Sanders score- Poor- 2 (12.50%) Fair -3 (18.75%) Good- 7 (43.75%) Excellent- 4 (25%) |

No complications 12 (75.0%) Failure 1 (6.25%) Infection 2 (12.5%) Delayed union 1 (6.25%) |

4 (Revision 1 (6.25%), debridement 2 (12.50%), re-graft 1 (6.25%)) |

||

| Bai 2018,China |

Single plate: NU 1 (2%) Dual plate: NU 0 |

Single plate: 14.3 mo Dual plate: 18 mo (p = 0.559) |

32 d |

Kolmert's standard Single plate Excellent 15 (31.3%) Good 24 (50.0%) Fair 7 (14.6%) Poor 2 (4.2%) Dual plate Excellent 4 (33.3%) Good 5 (41.7%) Fair 2 (16.7%) Poor 1 (8.3%) (p = 0.692) |

Single plate Nonunion 1 (2.1%) Dual plate Nonunion-0 |

||||

| Metwaly 2018, Egypt |

NU 0 DU 4 (17.4%) |

9 mo (3–12 mo) |

9 d |

All pts regained their knee range of motion that was 3° to 5° less compared to contralateral non-fractured side |

EQ-5D-5L score 83.8 (72–92) |

Screw breakage or cut-out 6 (26%) Superficial wound infection 2 (8.7%) DVT 1 (4.3%) |

4 (17.4%) cases needed autologous bone graft after 6 months because of no signs of union progression |

||

| Zhang 2018, China |

Single plate NU 0 DU 0 Dual plating NU 0 DU 0 |

17 weeks for both groups (p = 0.652) |

Single plate 121.33 ± 8.55 Dual plate 120.00 ± 9.41 (p = 0.692) |

VAS pain score Single plate 0.17 ± 0.31 Dual plate 0.25 ± 0.38 (p = 0.521) |

Neer score Single plate 87.20 ± 3.71 Dual plate 86.86 ± 3.74 (p = 0.806) |

Single plate Superficial infection 1 (6.6%) Death 1 (6.6%)(after 6mo due to pneumonia) Implant prominence 1 (6.6%) Dual plate DVT 1 (7.1%) Implant prominence 1 (7.1%) |

|||

| Bologna 2019,USA |

Single plate NU 6 (46.1%) DU 3 (23%) Dual plating NU 0 DU 0 (p = 0.0049) |

Single Plate 12.5 weeks (8.0–20.0) Dual plating 7 wks (6.25–7.0) (p = 0.0012) |

Single plate 100° (92.5°–115°) Dual plate 90° (70°–90°) (p = 0.036) |

No significant difference in the time to weight-bearing between the single (8.0 wks) and the dual (7.90 wks) plating groups (p = 0.32) |

Single plate: Nonunion 6 (46.2%) Delayed union 3 (23%) Reoperation 4 (30.8%) Revision ORIF 4 (30.8%) Knee stiffness 0 Infection 1 (6.1%) Dual plate: Nonunion 0 (0%) Delayed union 0 (0%) Reoperation 2 (25%) Revision ORIF 0 (30.8%) Knee stiffness 2 (25%) HO 2 (25%) |

Single plate: 4 (30.7%) (bone grafting) Dual plate: 2 (25%) (arthroscopic adhesiolysis 1, MUA 1) |

NU nonunion, DU delayed union, D days, weeks weeks, mo months, MUA manipulation under anesthesia, ORIF open reduction and internal fixation, HO heterotopic ossification, BG bone grafting

The mean healing time for the distal femur fracture using dual plates ranged from 11 weeks to 18 months. Three studies [21, 23, 24] compared the mean healing time in distal femur fracture treated with single and double plates. Bologna et al. found a significant difference in mean healing time between the two treatment groups [24]. The double plate group healed earlier (12.5 vs 7 weeks, p = 0.0012), but there was no significant difference between the groups in time to start the full weight-bearing. However, the other two studies found no significant difference in healing time between these two groups (Bai et al. [21] 14.3 months vs 18 months, p-value 0.559; Zhang et al. [23] 17 weeks for both groups, p-value 0.652). The pooled analysis of the studies reported earlier healing in the dual plating group compared to single plate fixation (MD 5.43, 95% CI 2.60, 8.26, p = 0.0002, I2 = 0%).

The range of motion was less than normal following dual plate fixation in the distal femur fracture. Sanders et al. [13] reported < 90° flexion in 33.3% of patients and flexion contracture of 5° in 44% of patients. Khalil et al. [16] found the restriction of motion (< 110°) in 42% of patients. Metwaly et al. [22] reported 3° to 5° less ROM in geriatric patients after dual plating. Two studies (Zhang et al. [23], Bologna et al. [24]) compared knee ROM between the two treatment groups. Bologna et al. [24] found significantly higher ROM in single plate groups (p = 0.036); two patients of double plate group in their series developed knee stiffness, one required manipulation under anesthesia, and the other required arthroscopic lysis of adhesions. Zhang et al. [23] compared the knee ROM between single and double plate groups at different time intervals (at 1 month, 3 months,6 months, and 1 year) in the postoperative period but found no significant difference (1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year—p 0.548, 0.403, 0.719 and 0.692, respectively).

Functional Outcome

The functional outcomes were evaluated using Sander's score, Neer's score and Kolmert's standard. Good to excellent outcome was observed in 55%–75% patients following dual plate fixation. The outcomes were better with the use of a medial locking plate. Zhang et al. [23] compared the VAS score and Neer score between the single plate and double plate groups at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months and 1 year following surgery and found no significant difference. Bologna et al. [24] compared the time for full weight bearing in these two groups. They found no significant difference in the time to weight-bearing between the single (8.0 weeks, range 8.0–12.5 weeks) and dual (7.90 weeks, range 6.25–10.0 weeks) plate groups (p = 0.32). Bai et al. [21] compared Kolmert's standard in both these two treatment groups but reported no significant difference in good–excellent postoperative knee function between them (p = 0.692) (Table 4).

Complications and Reoperations

The infection rate in the dual plate fixation of distal fracture was reported in 0 to 16.7% patients (Table 4). In the comparative study, there was no difference in infection between single and dual plate groups. Knee stiffness was observed in up to 25% of patients following dual plating. Ziran et al. [15] reported that the associated injuries to the extremities interfere with physical therapy of the knee and causes stiffness. Bologna et al. [24] reported better ROM in the single plate group than the dual plate group. Three studies reported hardware prominence and implant breakage. Metwaly et al. [22] reported screw breakage and cut out in 26% of patients, whereas Holzman et al. [18] reported 8.6% incidence of medial plate prominence. Zhang et al. [23] found an equal incidence of implant prominence in both single and double plate groups (one patient in each group). The reasons for reoperations or return to the operation theater were manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) for knee stiffness, quadricepsplasty, wound debridement, implant removal and revision ORIF or bone grafting. A maximum of 16.7% of patients needed MUA and quadricepsplasty in one study. In the comparison of single and dual plate groups, Bologna et al. [24] noted a significant difference in the nonunion and delayed union. There were six nonunions and three delayed unions in the single plate group but no nonunions or delayed unions in the double plate group (0.0049). However, Zhang et al. [23] and Bai et al. [21] did not notice such differences in their comparative studies. Bologna et al. [24] reported revision ORIF in four patients in the single plate group; however, none of the patients needed revision ORIF in the double plate group (p − 0.13). Zhang et al. [23] compared the complications between distal femur fracture treated with single plating and dual plating. They found no significant differences in complication rate between the two groups (p = 1.000).

Discussion

This systematic review revealed that dual plating leads to a satisfactory union in comminuted distal femur fractures, low supracondylar periprosthetic fractures, geriatric fracture and nonunions. The review failed to find any difference between the single plate and dual plate with regards to functional outcomes and complications. The meta-analysis of the comparative studies reported no difference in nonunion rate and blood loss between the single plate and double plate fixation groups. However, double plate fixation had a longer surgical duration and lesser fracture healing time. The findings of this systematic review are limited by the inclusion of different types of fracture (but definitely with appropriate indication), different medial implants and different outcome assessment methods.

After a detailed analysis of the studies, the indications of dual plating in the distal femur fracture are clear. As per AO classification, it was used for A2, A3, C1, C2 and C3 fractures of the distal femur. Similarly, few studies opted for the dual plate in very low periprosthetic fracture and nonunion following previous plate fixation for the above type of comminuted metaphyseal or articular fractures [10, 19]. Rajasekaran et al. applied an objective method for dual plate fixation [5]. After correction of the lower limb alignment at the fracture site, if the medial void was more than two cms, they advised for medial plating with bone grafting.

Several surgical approaches have been adopted in the literature; both medial and lateral approaches, the anterior medial/lateral parapatellar approach and modification of the extensile Olerud approach with TT osteotomy [14–25]. The extensile approach with TT osteotomy is probably not advisable as there is no additional advantage of this approach compared to the anterior parapatellar approach in terms of visualization and ease of fixation to the articular part and the medial and lateral surfaces. TT osteotomy is indicated only when there is extensive fibrosis in the distal part of the femur because of repeated surgery, and the patella cannot be everted or mobilized [35]. The most common fixation technique was the fixation of the plates on the medial and lateral surface of the distal femur [13, 16–24]. However, Ziran et al. and Chapman et al. placed the plates on the lateral surface and anterior surface (anteromedial) of the distal femur through the lateral parapatellar approach [14, 15]. Ziran et al. observed arthrofibrosis in 14% of their patients [15]. They believed that associated injuries in the extremities restricted an early rehabilitation and associated extensive damage to the suprapatellar tissue contributed to the stiffness. However, the placement of the anterior plate beneath the quadriceps cannot be excluded as a cause for a high stiffness rate in their series. They stressed on the meticulous repair of the suprapatellar pouch to prevent adhesions between the quadriceps and bone surface.

The comparative studies included in this review were ideal candidates for dual plating [21, 23, 24]. Accordingly, the findings of the limited meta-analysis reveal whether dual plating is superior to single plating or not. Bologna et al. included articular distal femur fracture with extensive metaphysical comminution (OTA-AO classification, 33-C2 or 33-C3) in addition to periprosthetic fracture, but Zhang et al. recruited only comminuted metaphyseal fractures (OTA 33-A2, 33-A3) [23, 24]. The study by Bai et al. followed a different strategy; their decision was based on intraoperative findings. After fixation of the lateral locked plate, they applied a varus force, and if it was positive, they proceeded for dual plating [21]. However, after fixation of a lateral locked plate, no one would expect a noticeable movement at the fracture site with the varus force. The whole of the lateral locked plate and screws act as a single unit, and it is usually rigid enough to resist any movement. It fails over a period of time when repetitive loading occurs on the construct. "How much force was applied?", "what was the duration of force application?" and "how did the authors appreciate the movement" remained debatable? This intraoperative assessment method does not seem appropriate. Instead, a preoperative decision for dual plating should be taken based on radiographic (X-ray, CT scan) fracture pattern [10, 27].

Most of the studies in this review augmented their dual fixation with bone grafting. Bottlang et al. evaluated lateral locking plate fixation strength in a fracture model with a bone defect of about 1 cm. They noted a cortical displacement of < 0.3 mm with an axial force of 400 N, and it was within the acceptable range of micro-movement (0.2–1 mm). Therefore, the intraoperative bone graft is recommended for bone defects of > 1 cm [36].

Several biomechanical studies have proven that dual plate fixation provides more rigid stability to the distal femur fracture when compared to a single plate [6–8]. However, critical damage to the medial vascularity by the medial approach and plate fixation was not observed in the previous studies [9]. In agreement with this, the finding of the current meta-analysis of the comparative studies revealed faster healing (mean difference 5.4 weeks) with dual plate fixation without additional risk of excessive intraoperative blood loss. However, the surgical duration was significantly longer in the double plate fixation group. Although a better union rate ((9.2% in single plate group vs 0% in double plate group) was observed with dual plate fixation, it was statistically insignificant. Undoubtedly, the dual plate provides rigid stability by stabilizing both the columns of the distal femur and preserving the vascularity on the medial side. One would expect the restriction of motion in dual plate fixation because of overstuffing and fibrosis with two incisions. In this review, most of the case series revealed a lesser range of motion [13, 15, 16, 22], but one comparative study failed to notice any difference between the single and dual plate fixation groups [23]. Recently, Beeres et al. reported minimally invasive double plating osteosynthesis for the periprosthetic distal femur fracture and nonunions [10]. The main advantage of this technique is early postoperative weight bearing even in the elderly frail patient in addition to minimal surgical dissection.

This review revealed a comparable functional outcome between the dual plate and single plate fixation [21, 23, 24]. Although isolated case series on dual plating showed an increased risk of infection (reported up to 16.7%) and knee stiffness (up to 25%) [16, 19, 20, 22, 23], the comparative studies did not notice such a difference. Overall there was no difference in complication rate between the single and dual plate fixation groups.

Although this systematic review synthesizes important information, there are certain limitations. Most of the studies are retrospective in nature, and the sample size is small. The recruited patients in the studies are from different age groups, and there are variations in surgical approach, fracture characteristics, type of implant and outcome assessment methods. The patient recruited in the studies were from a heterogeneous population. One study excluded periprosthetic fracture [23], whereas two studies included these fractures [19, 24]. Other studies did not mention it (probably no periprosthetic fracture). Some studies included only closed fractures, and others considered both closed and open fractures. The duration of presentation after trauma also differed markedly. The medial plate application in few studies was performed during the revision procedure. The numbers of comparative studies are also less.

Despite these limitations, this systematic review affirms that dual plating has an excellent union rate in the indicated cases. It is indicated in comminuted distal femur fractures, periprosthetic fracture with significant metaphyseal comminution and nonunion. It is recommended for C2, C3, A2 and A3 fractures (AO classification). The available limited evidence supports that there is no significant difference between the single plate and double plate regarding union rate, functional outcome, intraoperative blood loss and complications. However, the dual plate fixation leads to faster fracture healing at the cost of a longer surgical duration.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standard statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gwathmey FW, Jr, Jones-Quaidoo SM, Kahler D, Hurwitz S, Cui Q. Distal femoral fractures: Current concepts. Journal of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2010;18(10):597–607. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201010000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinet O, Cordey J, Harder Y, Maier A, Bühler M, Barraud GE. The epidemiology of fractures of the distal femur. Injury. 2000;31(Suppl 3):C62–C63. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)80034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gangavalli AK, Nwachuku CO. Management of distal femur fractures in adults: An overview of options. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2016;47(1):85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricci WM, Streubel PN, Morshed S, Collinge CA, Nork SE, Gardner MJ. Risk factors for failure of locked plate fixation of distal femur fractures: An analysis of 335 cases. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2014;28(2):83–89. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31829e6dd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajasekaran RB, Jayaramaraju D, Palanisami DR, Agraharam D, Perumal R, Kamal A, Rajasekaran S. A surgical algorithm for the management of recalcitrant distal femur nonunions based on distal femoral bone stock, fracture alignment, medial void, and stability of fixation. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2019;139(8):1057–1068. doi: 10.1007/s00402-019-03172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontenot PB, Diaz M, Stoops K, Barrick B, Santoni B, Mir H. Supplementation of lateral locked plating for distal femur fractures: A biomechanical study. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2019;33(12):642–648. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park KH, Oh CW, Park IH, Kim JW, Lee JH, Kim HJ. Additional fixation of medial plate over the unstable lateral locked plating of distal femur fractures: A biomechanical study. Injury. 2019;50(10):1593–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, Li J, Zhang H, Wang M, Li L, Zhou J, Guo H, Li Y, Tang P. Biomechanical assessment of single LISS versus double-plate osteosynthesis in the AO type 33–C2 fractures: A finite element analysis. Injury. 2018;49(12):2142–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rollick, N.C., Gadinsky, N.E., Klinger, C.E., Kubik, J.F., Dyke, J.P., Helfet, D.L., & Wellman, D. S. (2020) The effects of dual plating on the vascularity of the distal femur. The Bone & Joint Journal 102-B(4), 530–538. 10.1302/0301-620X.102B4.BJJ-2019-1776 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Beeres FJP, Emmink BL, Lanter K, Link BC, Babst R. Minimally invasive double-plating osteosynthesis of the distal femur. Operative Orthopädie und Traumatologie. 2020;32(6):545–558. doi: 10.1007/s00064-020-00664-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiamton C, Apivatthakakul T. The safety and feasibility of minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO) on the medial side of the femur: A cadaveric injection study. Injury. 2015;46(11):2170–2176. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JJ, Oh HK, Bae JY, Kim JW. Radiological assessment of the safe zone for medial minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis in the distal femur with computed tomography angiography. Injury. 2014;45(12):1964–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanders R, Swiontkowski M, Rosen H, Helfet D. Double-plating of comminuted, unstable fractures of the distal part of the femur. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1991;73(3):341–346. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199173030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman MW, Finkemeier CG. Treatment of supracondylar nonunions of the femur with plate fixation and bone graft. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1999;81(9):1217–1228. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199909000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziran BH, Rohde RH, Wharton AR. Lateral and anterior plating of intra-articular distal femoral fractures treated via an anterior approach. International Orthopaedics. 2002;26(6):370–373. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0383-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khalil A-S, Ayoub MA. Highly unstable complex C3-type distal femur fracture: can double plating via a modified Olerud extensile approach be a standby solution? Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 2012;13(4):179–188. doi: 10.1007/s10195-012-0204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dugan TR, Hubert MG, Siska PA, Pape HC, Tarkin IS. Open supracondylar femur fractures with bone loss in the polytraumatized patient—Timing is everything! Injury. 2013;44(12):1826–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holzman MA, Hanus BD, Munz JW, O'Connor DP, Brinker MR. Addition of a medial locking plate to an in situ lateral locking plate results in healing of distal femoral nonunions. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2016;474(6):1498–1505. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4709-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinberg EL, Elis J, Steinberg Y, Salai M, Ben-Tov T. A double-plating approach to distal femur fracture: A clinical study. Injury. 2017;48(10):2260–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imam MA, Torieh A, Matthana A. Double plating of intra-articular multifragmentary C3-type distal femoral fractures through the anterior approach. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology. 2018;28(1):121–130. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-2014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai Z, Gao S, Hu Z, Liang A. Comparison of clinical efficacy of lateral and lateral and medial double-plating fixation of distal femoral fractures. Science and Reports. 2018;8(1):4863. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23268-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metwaly RG, Zakaria ZM. Single-incision double-plating approach in the management of isolated. Closed Osteoporotic Distal Femoral Fractures: Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2018;9:1–8. doi: 10.1177/2151459318799856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Wei Y, Yin W, Shen Y, Cao S. Biomechanical and clinical comparison of single lateral plate and double plating of comminuted supracondylar femoral fractures. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2018;84(2):141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bologna MG, Claudio MG, Shields KJ, Katz C, Salopek T, Westrick ER. Dual plate fixation results in improved union rates in comminuted distal femur fractures compared to single plate fixation. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2019;15(18):76–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2019.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebraheim NA, Buchanan GS, Liu X, Cooper ME, Peters N, Hessey JA, Liu J. Treatment of distal femur nonunion following initial fixation with a lateral locking plate. Orthopaedic Surgery. 2016;8(3):323–330. doi: 10.1111/os.12257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebraheim NA, Martin A, Sochacki KR, Liu J. Nonunion of distal femoral fractures: A systematic review. Orthopaedic Surgery. 2013;5(1):46–50. doi: 10.1111/os.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dougherty PJ. CORR Insights(®): Addition of a medial locking plate to an in situ lateral locking plate results in healing of distal femoral nonunions. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2016;474(6):1506–1507. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4745-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sain A, Sharma V, Farooque KVM, Pattabiraman K. Dual Plating of the Distal Femur: Indications and Surgical Techniques. Cureus. 2019;11(12):e6483. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jazrawi LM, Kummer FJ, Simon JA, Bai B, Hunt SA, Egol KA, Koval KJ. New technique for treatment of unstable distal femur fractures by locked double-plating: Case report and biomechanical evaluation. Journal of Trauma. 2000;48(1):87–92. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutton B, Wolfe D, Moher D, Shamseer L. Reporting guidance considerations from a statistical perspective: overview of tools to enhance the rigour of reporting of randomized trials and systematic reviews. Evidence Based Mental Health. 2017;20:46–52. doi: 10.1136/eb-2017-102666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longo UG, Rizzello G, Loppini M, Locher J, Buchmann S, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Multidirectional Instability of the Shoulder: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2431–2443. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Available from https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence

- 33.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014. Accessed March 05, 2021.

- 34.Zlowodzki, M., Poolman, R. W., Kerkhoffs, G. M., Tornetta, P., & Bhandari, M., International Evidence-Based Orthopedic Surgery Working Group. How to interpret a meta-analysis and judge its value as a guide for clinical practice. Acta Orthop. 78(5), 598–609. 10.1080/17453670710014284. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Khlopas A, Samuel LT, Sultan AA, Yao B, Billow DG, Kamath AF. The olerud extensile anterior approach for complex distal femoral fractures: a systematic review. The Journal of Knee Surgery. 2019 doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bottlang M, Feist F. Biomechanics of far cortical locking. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S21–S28. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318207885b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]