Abstract

Differences in prosody behavior between individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and their typically developing peers have been considered a central feature of ASD since the earliest clinical descriptions of the disorder (e.g., Kanner, 1943/1973). Prosody includes pitch and volume among other dimensions of vocal-verbal behavior that discriminate responses of the listener; thus, people with ASD whose prosody has confusing or off-putting effects may have fewer social opportunities at work, at school, or in the community. The purpose of this review is to examine the state of the literature intervening on prosody with individuals with ASD and to provide recommendations for researchers who are interested in contributing to the scientific understanding of prosody.

Keywords: Autism, Prosody, Conversation, social skills

Level 1 autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is the current term from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), to describe people with symptoms of ASD and no comorbid intellectual disability who may meet the criteria for Asperger’s disorder under prior systems. People with Level 1 ASD experience limited educational, employment, and social opportunities despite having cognitive abilities comparable to their typically developing peers (e.g., Roessler et al., 1990; Scattone, 2008). Differences in prosody behavior between individuals with ASD and their typically developing peers have been considered a central feature of ASD since the earliest clinical descriptions of the disorder (e.g., Kanner, 1943/1973). Unlike people with comorbid ASD and intellectual disabilities, these individuals spend the majority of their time in environments where neurotypical people compose the dominant social group (Pinder-Amaker, 2014; VanBergeijk et al., 2008).

Nuernberger et al. (2013) proposed that the normative cognitive abilities of some individuals with ASD contribute to listener misattribution of conversational errors. For example, conversation partners may expect a college student with Level 1 ASD to understand that speaking in a loud and monotone voice makes people uncomfortable; therefore, neurotypical peers, professors, or employers may treat the student who persists in behaving this way as arrogant or malicious. Misattributions secondary to the juxtaposition of sophisticated vocabulary with acute social differences may contribute to the statistic that people with ASD are accused of harassment disproportionately more than their typically developing peers or their peers with other disabilities (Haskins & Silva, 2006; Stokes & Newton, 2004). Patrick (2008) and Hagland and Webb (2009) discussed how college students with and without ASD who demonstrate poor conversational skills are vulnerable to bullying, social rejection, or being judged by their peers as odd or annoying. Findings suggest that 94% of young adults with ASD report being shunned by peers in the past year (Little, 2001) and that conversational differences associated with ASD were significantly and positively correlated with reported victimization by peers (Forrest et al., 2020).

The behavior-analytic orientation asserts that a person’s learning history and their current environment are critical determinants of their social skills. For example, Skinner (1957) described a conversation as a verbal exchange wherein the listener provides stimuli that should at least partially control the speaker’s responses. Participants in a conversation reciprocally play the role of speaker and listener, and the conversational responses of each participant function as both antecedent and consequence stimuli for their partner’s behavior. For example, the speaker saying “How was your meeting?” functions as a discriminative stimulus for a response from the listener. The listener responding “Oh, it was great” functions as a consequence for the speaker’s question and, potentially, as a discriminative stimulus for the speaker’s next response. To date, behavior analysts have developed efficacious means to improve the conversational skills of people with ASD, including reciprocal, on-topic commenting (e.g., L. K. Koegel et al., 2014); asking questions or changing the topic discriminated by indices of partner disinterest (Mann & Karsten, 2020; Peters & Thompson, 2015); and apologizing, confirming tasks, or soliciting performance feedback discriminated by various work scenarios (Grob et al., 2019), among other responses.

Skinner (1957) described the autoclitic as verbal behavior that is dependent on other verbal behavior and that modifies the listener’s behavior in a particular way. For example, Palmer (1999) discussed how the differential use of stress and timing of pauses can function as autoclitics and alter the stimulus control of spoken utterances. A response of “Oh, it was great” to the query about a previous meeting, spoken slowly with a stress on the “oh,” may function to alert the listener that the meeting did not go well. However, differential tone and stress on the “great” could function to alert the listener that the meeting went very well. Research outside of behavior analysis also supports the notion that a person’s perception of a speaker is discriminated by the physical properties of their speech. For example, Rockwell (2000) studied typically developing speakers and listeners and found that conversation partners perceive phrases spoken at a higher pitch and a faster rate as excited, whereas they perceive the same phrase spoken slowly in a lower pitch as apprehensive or ironic. Srinivasan and Massaro (2003) found that typically developing individuals rely more heavily on auditory rather than visual cues to determine whether the same spoken phrase is a statement or a question. The form of the utterance alters the function of what the speaker says, and a precise effect on the listener is critical to social access and well-being.

“Prosody” is a term that refers to the physical properties of speech independent of the words that are said (Wingfield et al., 1989). Scholars within and across the disciplines of speech-language pathology and linguistics disagree regarding exactly which dimensions of speech the term “prosody” covers (see Peppe et al., 2009, and Kalathottukaren et al., 2017, for reviews). For the purposes of the current review, we will refer to “prosody” as any dimension of vocal-verbal speech apart from the individual phonetic segments that make up spoken words. Prosody includes dimensions of speech such as pitch, stress, and volume patterns (i.e., intonation), as well as temporal dimensions of speech (e.g., rate, length, and timing of pauses within and between utterances). Table 1 lists definitions of the dimensions of prosody as they appear in a well-established assessment for speech-language pathologists and linguists, the Prosody-Voice Screening Profile (PVSP; Shriberg et al., 1990).

Table 1.

Shriberg et al.’s (1990) definitions of selected prosody behaviors

| Behavior/dimension | Definition |

|---|---|

| Phrasing | The smoothness or fluency of speech (part- and whole-word repetitions and revisions) |

| Rate | The overall pace of speech (too slow or too fast as measured by syllables per second) |

| Stress | The relative emphasis on syllables and words (intensity, pitch, duration) |

| Loudness | The intensity with which utterances are produced (too soft, too loud) |

| Pitch | The average frequency of the voice in hertz (cycles per second) |

| Voice quality | The sound produced by the larynx (e.g., harsh, strained) |

| Resonance | The sound produced by the vocal tract (e.g., nasality vs. denasality; pharyngeal resonance) |

Descriptive studies have demonstrated differences between the prosody of individuals with Level 1 ASD and that of their neurotypical peers (e.g., Paul, Augustyn et al., 2005a; Paul, Shriberg, et al., 2005b). For example, Shriberg et al. (2001) found that trained observers coded the stress patterns of 56% of speakers with ASD and 12% of typically developing speakers as “inappropriate.” When asking their conversation partner for their opinion, participants with ASD were more likely to say, “What do YOU think?” whereas typically developing peers were more likely to say, “WHAT do you think?” Although the authors did not study the differential effects of these behaviors on listeners, the stress patterns of speakers with ASD were notably different from those of their peers. Shriberg, et al. (2001) also reported that the decibel level of utterances was lower and the pitch was higher for participants with ASD compared to typically developing participants. Documented differences between individuals with ASD and their matched peers also include the use of longer pauses between conversational terms (e.g., Paul et al., 2009; Rendle-Short, 2002) and less variable pitch patterns (Nakai et al., 2014). Although many studies describe differences in speech patterns between individuals with ASD and their typically developing peers, fewer studies report whether these prosodic differences are socially significant. Prior studies have demonstrated that listener tacts of speaker intention are discriminated by prosody (e.g., Cole et al., 2010; Cutler & Ladd, 2013; Rockwell, 2000; Tree & Meijer, 2000); however, researchers have yet to evaluate how utterances tacted as “excited” or “ironic” differentially affect listeners’ subsequent social behavior.

Prosody is likely the result of consequences across three levels of selection (Skinner, 1981). Idiosyncratic differences in prosody such as an individual’s total pitch range are constrained by the biological structure of the lungs, larynx, and vocal tract through which speech is produced (Casper & Leonard, 2006). Similarly, localized brain damage can result in disordered prosody (i.e., aprosodia; Leung et al., 2017), further suggesting that prosody behavior has neurological constrictions. Daily interactions provide ample anecdotal evidence that a neurotypical person’s verbal community shapes prosody behaviors discriminated by various environmental conditions. For example, English speakers use a different pitch when they ask a question compared to when they make an assertion (Liberman et al., 1967). Further, characteristic and differential use of prosody is evidenced across languages (e.g., Itahashi et al., 1994; Thompson & Balkwill, 2006), suggesting that changes in the function of language signaled by prosody are selected at the societal level and differentially reinforced by the verbal community during an individual’s lifetime.

Despite debate around the quantitative dimensions of speech that compose prosody, authors have acknowledged the functional role of prosody behavior across disciplines. For example, speech-language pathologists McAlpine et al. (2014) described prosody as “aspects of language that we use to communicate, modify, or highlight the meaning of a spoken message” (p. 1092). Similarly, cognitive psychologists Nadig and Shaw (2012) stated, “By varying prosodic features such as pitch and speech rate, speakers can portray additional meaning about their emotional state and modulate their communicative intent” (p. 499). From a behavior-analytic perspective, prosody contributes to the operant function of an utterance (e.g., Krantz, 2000; Palmer, 1999) within the autoclitic frame (Skinner, 1957). For example, “get out” can function as either a mand for the listener to leave or a tact that the listener just said something interesting; the listener’s subsequent response is discriminated by aspects of the speaker’s prosody, among other variables, that in the past preceded punishment or reinforcement for particular responses.

The behavior-analytic orientation is helpful when conceptualizing the function of prosody because the “meaning” of an utterance is equivalent to its effect on a member of the speaker’s verbal community. By focusing on functional determinants of behavior in the environment, behavior analysts can identify the variables controlling prosody and affect changes that may help individuals with Level 1 ASD access opportunities associated with a higher quality of life (e.g., jobs, relationships). Skinner (1957) asserted, “What happens when a man speaks or responds to speech is clearly a question about human behavior and, hence, a question to be answered with the concepts and techniques of psychology as an experimental science of behavior” (p. 5).

Some researchers have suggested that atypical prosody is a contributor to poor social outcomes. Paul et al. (2005a, b) measured the prosody performance of individuals with ASD using the PVSP (Shriberg et al., 1990), one of many software programs that objectively measure when prosody performance falls outside of typical parameters. Investigators found a positive correlation between atypical prosody performance and caregiver ratings of social competence as measured by a standardized semistructured interview (Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales–Survey Form; Sparrow et al., 1984) and a structured behavioral assessment (e.g., Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic; Lord et al., 2000). Taken together, these data illustrate opportunities to address prosody differences among people with Level 1 ASD, but past research falls short of demonstrating the conditions under which specific prosody differences contribute to poor social outcomes.

The behavior-analytic orientation is well suited to build on the descriptive work of previous researchers by evaluating interventions that may help people with Level 1 ASD achieve more adaptive prosody and, thereby, allow them to participate in more frequent and mutually fulfilling conversations. The purpose of this article is to review what is currently known about altering prosody behavior using an experimental science of behavior.

Method

Studies were identified through a computer search of PsycInfo, PubMed, and Google Scholar using the keywords “high-functioning autism,” “autism,” and “Asperger’s” with the terms “conversation,” “conversation deficits,” “prosody,” “conversation behavior,” “social communication,” “voice volume,” “tone,” “intonation,” “resonance,” “pitch,” “affect,” “affective responding,” and “speech pattern.” To be included in the current review, articles had to (a) appear in a peer-reviewed journal outlet; (b) include at least one participant described as having high-functioning autism, Asperger’s disorder, or ASD with a report of an IQ > 70 or who carried a diagnosis characterized by social impairments but who spent the majority of their time in neurotypical settings; (c) describe at least one result in terms of a measure of prosody (i.e., a physical property of vocal-verbal speech outside of the words said); and (d) use either a group or single-subject research design to evaluate change in the prosody variable as a function of the intervention.

The computer search returned 187 articles. Reviews of the Method section of each article resulted in the exclusion of 171 articles (24 articles did not include at least one relevant participant; 147 did not include a measure of prosody). Of the remaining 26 articles, 15 were excluded as they did not use a group or single-subject experimental design to evaluate change in the prosody variable as a function of the intervention. The reference lists of the 11 remaining articles were examined to identify additional articles the met the criteria for inclusion but that were not returned by the original database search. This step resulted in the identification of 4 additional articles for a total of 15 articles included in the present review (Table 2).

Table 2.

Articles included for review

| Article | Prosody variable(s) | Definition(s) of prosody variable(s) provided by authors | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beaulieu et al. (2014) | Interrupting | Participant did not make vocal initiations while the confederate spoke. | BST, including visual feedback |

| Charlop et al. (2010) | Volume, intonation | Participant exhibited contextually appropriate intonation and volume (e.g., exclamation, loud/authoritative). | Video modeling |

| Daou et al. (2014) | Volume, intonation | Participant exhibited contextually appropriate intonation and volume (e.g., expressing empathy with a sad/low voice). | Reinforcement, prompting, script fading, and shaping |

| Dotson et al. (2010) | Tone of voice | Participant maintained an appropriate, positive voice tone. | Group instruction BST and differential reinforcement |

| Volume | Participant maintained an appropriate voice volume (i.e., loud enough that the observer and peer could hear but not loud enough to cause a disruption). | ||

| Gena et al. (2005) | Latency to respond | Participant emitted target responses within 5 s of scenario presentation. | In vivo modeling, video modeling, reinforcement, and prompting |

| Tone of voice | Participant exhibited a contextually appropriate tone of voice (e.g., showing sympathy, appreciation, or approval). Responses of appreciation and disapproval required a higher and more animated tone of voice; responses of sympathy required a lower and flatter tone. | ||

| Koegel and Frea (1993) | Affect | Participant used affect that was relevant to the conversation. | Discrimination training and self-monitoring in a natural setting |

| Volume | Participantvoice remained at a level compatible with the setting. | ||

| Leaf et al. (2012) | Interrupting | Participant interrupted appropriately (wait for a break, say “excuse me,” state person’s name, say “sorry for interrupting,” etc.). | Discrimination training |

| Nuernberger et al. (2013) | Interrupting | Participant did not interrupt. | BST |

| Palmen et al. (2008) | Latency to respond | Participant emitted target response within 5 s of an experimenter utterance. | Discrimination training, role-play, and feedback |

| Radley et al. (2015 | Volume, speech pacing | Participant used an appropriate voice with volume appropriate for the setting and even-paced speech. | Video-based instructions and models, discrimination training, self-monitoring, and role-play |

BST behavioral skills training

Results

Prosody Targets

Of the 15 included studies, 9 addressed temporal dimensions of conversation such as latency to respond (Gena, Couloura, & Kymissis, 2005; Palmen et al., 2008; Thiemann & Goldstein, 2001; Tiger et al., 2007), rate of speaking (e.g., Simmons et al., 2016), and interrupting (Beaulieu et al., 2014; Leaf et al., 2012; Nuernberger et al., 2013; Schmidt & Stichter, 2012). Seven studies measured global dimensions of behavior that were referred to as intonation (Charlop et al., 2010; Daou et al., 2014), affect (Gena et al., 2005; R. L. Koegel & Frea, 1993), and tone of voice (Dotson et al., 2010; Radley et al., 2015). Similarly, Sansosti and Powell-Smith (2008) addressed the volume of speech by including “not shouting” in their global dimension of appropriate conversation responses. The lack of a universally accepted definition of prosody (Peppe, McCann, Gibbon, O'Hare, & Rutherford, 2009; Shattuck-Hufnagel & Turk, 1996) is evinced by the varying labels of prosody behavior adopted in prior studies. Researchers described variations in pitch as varied “intonation” (Gena et al., 2005), “affect” (Daou et al., 2014), and “tone of voice” (Dotson et al., 2010). Further, definitions of prosody overlap with respect to the included dimensions of vocal-verbal behavior. For example, Charlop et al. (2010) defined stress in terms of the relative volume of words in an utterance, whereas, in the speech literature, speech stress has been defined as the relative emphasis given to a syllable through differential use of tempo, air density, phoneme group portioning, and diphthong use (see Hansen & Patil, 2007, for a discussion on the challenges related to defining stress, specifically).

Participant Characteristics

Characteristics of participants in the included studies provide insight into the unique needs of people with ASD for whom prosody behavior is a concern. The ages of participants at the time of the studies ranged from 4 years old (Leaf et al., 2012) to 23 years old (Nuernberger et al., 2013). Collectively, researchers described participants who demonstrated sophisticated social-communication repertoires in baseline. For example, the participant in Beaulieu et al. (2014) was a college student with a diagnosis of a learning disability who solicited help with his conversation skills. Although these authors do not specify whether the participant solicited help for prosody behavior (interrupting) specifically, his self-referral suggests that the participant had cognitive and social repertoires sufficiently refined (a) to identify that professional help would be valuable and (b) to ask for help from an appropriate source (i.e., his campus student disability services department). Other researchers included scores from standardized language assessments prior to treatment that suggest sophisticated communication repertoires. For example, Sansosti and Powell-Smith (2008) recruited participants with a current diagnosis of ASD but no communication concerns as evidenced by the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals, third edition. Taken together, participants from included studies had sophisticated social-communication repertoires, and yet they struggled to meet the social demands of their environments.

Researchers modified commonly used intervention procedures to ensure they were appropriate for the sophisticated cognitive and verbal repertoires of their participants. For example, to allow for a natural flow within the rehearsal plus feedback component of behavioral skills training (BST), Beaulieu et al. (2014) used visual feedback by removing a glass bead from the table contingent on participant interruption. The number of glass beads available per conversation decreased as the participant’s level of interruptions approached socially adaptive levels.

Approaches to Operationalizing Prosody

Behavior analysts are committed to operationalizing behavior to allow for analytic conclusions about (a) the effects of the independent variable on the target behavior (i.e., treatment efficacy) and (b) direct and systematic replications of procedures, both in research and in practice. Strong operational definitions are objective, clear, and complete (Kazdin, 2011). Four prior studies (Beaulieu et al., 2014; Charlop et al., 2010; Dotson et al., 2010; Tiger et al., 2007) included objective criteria for measuring prosody in their operational definitions. Past definitions of interrupting illustrate the importance of including objective criteria. Nuernberger et al. (2013) scored a response correct if the participant “didn’t interrupt.” Beaulieu et al. (2014), by contrast, defined interrupting as vocal initiations emitted while the confederate spoke. Further, their definition included additional clarifying detail in that positive feedback (e.g., “hmm-hmm,” or “yeah”) did not qualify as an interruption. Without measurable examples and nonexamples of what constitutes interrupting, subjective rater interpretations are possible, limiting the potential utility of those definitions for other researchers. Similarly, Tiger et al. (2007) measured latency from the end of the experimenter’s question to the time the participant completed his response. Readers can interpret the results of Beaulieu et al. and Tiger et al. with confidence because their data reflect direct and reliable measures of behavior as opposed to subjective reports of change.

Notably, none of the seven studies that addressed intonation-related dimensions (e.g., pitch, volume) included objective, physical measures of speaker behavior. Rather, investigators assessed intonation-related dimensions of prosody based on the subjective judgment of the data collector: not “shouting” (p. 167; Sansosti & Powell-Smith, 2008), “maintained positive voice tone” (p. 202; Dotson et al., 2010), and “affect that was relevant to the present conversation” (p.371; R. L. Koegel & Frea, 1993). When researchers included objective and measurable definitions of appropriate intonation, they did not directly assess the participant’s behavior. For example, Dotson et al. (2010) defined appropriate volume as the utterance being loud enough that the observer and peer could hear its content, but not loud enough to cause a reaction from other classmates. Daou et al. (2014) included descriptions of pitch in their definitions (e.g., “lively,” “sad tone”), but they did not quantify the behaviors of interest directly; rather, these authors measured observer ratings of appropriate intonation. Daou et al. described the challenge of operationally defining prosody: “These social stimuli are difficult to describe, but easily recognizable” (p. 484).

Investigators who used indirect behavioral measures contributed less information about treatment efficacy to the literature base. Of the studies included in this review, 53% relied on rater assessment of appropriate prosody as their primary dependent variable (Daou et al., 2014; Dotson et al., 2010; Gena et al., 2005; R. L. Koegel & Frea, 1993; Nuernberger et al., 2013; Radley et al., 2015; Schmidt & Stichter, 2012). In these studies, the observer scored the participant’s response as correct if the response was emitted with volume (e.g., R. L. Koegel & Frea, 1993; Radley et al., 2015) or intonation (e.g., Gena et al., 2005) deemed appropriate for the setting by the data collector. Investigators reported changes in observer ratings postintervention, but the precise behaviors that contributed to this change warrant further investigation.

Experimental Control in Studies Intervening on Prosody

A high order of experimental control allows researchers to draw conclusions regarding the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable (Sidman, 1988). Each of the studies included in the current review employed a single-subject design to demonstrate the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable(s); however, only 20% reported on the impact of the independent variable on the prosody variable specifically (Beaulieu et al., 2014; Charlop et al., 2010; Tiger et al., 2007). Results of this review reveal that when prosodic dimensions are addressed in treatment, they are often members of a broader response class that is scheduled for differential reinforcement (73% of studies: Charlop et al., 2010; Daou et al., 2014; Dotson et al., 2010; Gena et al., 2005; Leaf et al., 2012; Nuernberger et al., 2013; Palmen et al., 2008; Radley et al., 2015; Sansosti & Powell-Smith, 2008; Schmidt & Stichter, 2012; Thiemann & Goldstein, 2001). For example, Dotson et al. (2010) required participants to maintain an appropriate voice tone and volume in addition to appropriate body posture, proximity, and eye contact throughout the interaction in order to contact reinforcement. Investigators who collapse prosody variables into broader responses classes contribute less information regarding the efficacy of the independent variable for changing prosody. For example, the degree to which prosody, in particular, was a concern before and after treatment is unclear when investigators only report on the broader response class. Subsequent discussion of independent variables and treatment outcomes, therefore, focuses on the three prior studies that report a direct measure of prosody (i.e., Beaulieu et al., 2014; Charlop et al., 2010; Tiger et al., 2007).

Two prior researchers programmed contingencies to address a dimension of prosody and experimentally evaluated the effects of intervention on prosody. Tiger et al. (2007) targeted a single dependent variable (latency to respond), as this was the primary conversation concern for the participant. Beaulieu et al. (2014) addressed one prosody dimension (rate of interrupting) and two non-prosody-related conversation dimensions (rate of questions and observer rating of content specificity) that were of concern for their participant. Tiger et al. used a reversal design to demonstrate the efficacy of differential reinforcement of short and long response latencies. These investigators obtained a high order of experimental control; when differential reinforcement was available for short or long latencies, responses quickly conformed to the contingency in place. Beaulieu et al. used a multiple-baseline design with an embedded reversal to sequentially apply peer-mediated BST across prosody and nonprosody variables. Intervention was immediately successful in decreasing interruptions to rates commensurate with those observed among typically developing peers. Baseline levels of interrupting did not recover when baseline conditions were reinstated; however, the multiple-baseline arrangement demonstrated a change in each of the dependent variables when and only when intervention was applied.

Prosody dimensions always co-occur with other dimensions of speech and conversational behavior. Therefore, it may be of greater social import for future researchers to arrange contingencies for a broader class of conversational behaviors, but to measure and report changes per component response in order to evaluate the impact of the independent variable. The third study that demonstrates a high order of experimental control illustrates this approach. Charlop et al. (2010) defined and measured a prosody dimension (observer rating of appropriate intonation), a content dimension (appropriate comments), and two nonvocal dimensions (observer rating of appropriate gestures and facial expressions) within the response class of conversational behaviors. These authors used a multiple-baseline design across participants to evaluate the effects of video modeling, and they measured and reported on each member of the response class of interest. During baseline, raters rarely scored the intonation of the participants as appropriate. Following the introduction of video modeling and differential reinforcement, raters scored five different intonation patterns of the participant as appropriately discriminated by five different stimulus conditions. For example, in one condition, the investigators showed the participants a preferred toy and scored a correct response if they emitted an exclamation perceived by the experimenter as positive and if the word “cool” was louder than other words. Conversely, in a second condition, the investigator removed a toy and scored the participant’s utterance as correct if they emitted an exclamation in a loud voice perceived by the experimenter as negative.

Social Acceptability of Procedures and Validity of Outcomes

Baer et al. (1968) articulated that the responsibility of the applied behavior analyst is to support socially significant change. Therefore, it is important to discuss the degree to which past studies assessed the social acceptability of treatment goals, treatment procedures, and changes in prosody according to participants and other relevant stakeholders (e.g., contextually relevant social partners). Beaulieu et al. (2014) was the only study that included steps before intervention to ensure the ecological validity of targeted skills—that is, the degree to which the treatment goals would be consistent with the performance of typical peers and presumably more socially acceptable to peers or other secondary stakeholders. Specifically, these authors observed typically developing peers conversing and found that typically developing peers interrupted at an average rate of 3.9 per min. These authors then designed the intervention to bring rates of interrupting down to a level commensurate with typically developing peers. Neither Beaulieu et al. nor other prosody studies in this review describe the degree to which participants with Level 1 ASD had opportunities to influence the treatment goals. At a minimum, participants or their legal guardians must have approved the treatment goals and procedures in each study during the informed consent process; additional assessment and collaborative procedures are necessary to shed light on the social acceptability of prosody-related treatment goals. Of the three prior studies that demonstrated a functional relation between intervention and a precise measure of prosody, only Beaulieu et al. contributed data regarding the participant’s ratings of the social acceptability of their procedures and outcomes. Therefore, the social validity of intensive prosody interventions among people with Level 1 ASD is not currently well understood.

Treatment outcomes are socially valid when they result in the consumer of the intervention achieving greater access to personally significant reinforcers. Three prior researchers measured the social acceptability of treatment outcomes with secondary stakeholders (Beaulieu et al., 2014; Charlop et al., 2010; R. L. Koegel & Frea, 1993); however, none of the studies included in this review isolated the impact of changes to prosody, assessed the social acceptability of outcomes with participants with ASD, or assessed the social validity of outcomes in terms of increased access to social reinforcement. For example, Beaulieu et al. (2014) recruited three peers who were unfamiliar with the participant to watch 5-min videos of him conversing pre- and posttreatment. Peers who were not aware of the purpose of the study rated the participant’s overall conversational skills on a 7-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores indicating a more favorable rating. The mean score for the baseline video was 2.3 of 7, and the mean score posttreatment was 5.3 of 7. Similarly, Charlop et al. (2010) reported improved naive observer ratings of participant behavior posttreatment.

Generalization

Each of the prior studies that reported on prosody performance specifically measured behavior change outside of the training context. Charlop et al. (2010) showed that stimulus intonation generalized across different people in different rooms using similar but not identical stimuli (e.g., a different preferred toy was taken from the participant). Beaulieu et al. (2014) observed participants having posttreatment conversations with untrained peers and documented rates of interrupting similar to those achieved in treatment. Tiger et al. (2007) noted generalization of the targeted short response latency to a category of questions that had never contacted differential reinforcement. These authors applied the differential reinforcement contingency (differential reinforcement of short latency) to easy and difficult questions, but not to questions of medium difficulty (i.e., math questions that the participant had learned to complete, but that often required paper and pencil to reach a solution). However, short latencies occurred in response to questions of medium difficulty. Specifically, the participant said “I don’t know” with a latency similar to posttreatment responses in the targeted conditions, providing evidence of generalization.

Applied research addresses behaviors that are socially important to the participants’ quality of life and to society (e.g., Baer et al., 1968). Results of this review suggest that the selected target behaviors align with available comparative data between individuals with ASD and typically developing peers. Descriptive and comparative data shed light on group-level differences that society tacts as important based on diagnostic classifications, but knowledge of typical prosody should be used in conjunction with behavioral assessments to ensure the social significance of the goal at the individual level. For example, Beaulieu et al. (2014) used a variety of sources and assessment methods to inform target selection (e.g., participant and caregiver interviews, direct observations of the participant conversing, and results from prior research).

Prior studies have demonstrated that peers (Beaulieu et al., 2014) and undergraduate students (Charlop et al., 2010) rated participant conversation skills more favorably posttreatment. Although improved ratings from peers evince the social validity of the general outcomes, the relationship between these improved ratings and peers’ acceptance of people who engage in typical versus atypical patterns of prosody behavior remains an empirical question.

Prior studies have demonstrated that changes in prosody persist outside of the training context. However, researchers have yet to demonstrate the ecological validity of generalization conditions. For example, Charlop et al. (2010) showed that behavior change generalized to similar settings and materials (e.g., experimenter removing a different preferred toy). However, the authors did not evaluate the extent to which training and generalization conditions mirror the conditions that participants encounter in their daily lives; therefore, it is not currently known whether context-appropriate intonation would be evoked under conditions the participant regularly encounters. Further, maintenance data were not reported in any of the prior studies.

The prosody of typically developing individuals is discriminated by context (see Degand & Simon, 2009). Therefore, it is important that investigators study necessary conditions to produce posttraining prosody behavior discriminated by an ecologically valid range of conditions. For example, Tiger et al. (2007) reported undesirable generalization of short latencies to questions of medium difficulty (i.e., saying “I don’t know” quickly rather than solving the problem and then answering). This result suggests that responding to medium-difficulty questions was not under the ideal compound control of the contingency for short latencies and a correct response at strength. The authors reestablished the desired stimulus control by delivering differential consequences for both response latency and response accuracy on medium-difficulty and low-difficulty questions. Undesirable generalization reported by Tiger et al. highlights the importance of designing interventions that ensure prosody behaviors are discriminated by those circumstances in which people with ASD will experience the greatest applied value of the change in their behavior.

Discussion

The results of this review indicate that a relatively small number of studies targeting the conversational skills of individuals with Level 1 ASD addressed prosody. Though the body of literature on improving prosody for people with ASD is small, the results of prior studies are promising. The findings of this review indicate that prosody behavior can be altered through the manipulation of environmental variables, and that changes in prosody may persist across similar but untrained settings.

Prosody researchers have the opportunity to treat behavior long considered concomitant with a diagnosis of ASD. To advance research on the assessment and treatment of prosody, we encourage researchers who study conversational skills to include prosody as a primary or secondary dependent variable. Past researchers (e.g., Beaulieu et al., 2014; Charlop et al., 2010) provide a model for how prosody behavior can be evaluated and addressed concurrently with other dimensions of speech without sacrificing experimental control.

Findings of this review tentatively reveal that even when interventions result in measurable changes to conversational behaviors including prosody, social validity ratings may remain low. For example, Thiemann and Goldstein (2001) noted an increase in appropriate comments (a broad response class that included latency to comment) following treatment. However, adult observers rated the quality of participant comments posttreatment as somewhat less than average for age group. These data highlight the need to understand the precise impact of changes in prosody on socially important outcomes.

We suggest that researchers look to descriptive and comparative research from fields outside of behavior analysis to identify prosody behaviors that warrant further attention (e.g., Filipe et al., 2014; Grossman et al., 2010; Scharfstein et al., 2011). Studies included in this review addressed dimensions of atypical prosody suggested by prior descriptive studies of people with ASD, yet other dimensions remain unstudied. For example, Shriberg et al. (2001) noted discrepancies between individuals with ASD and their typically developing peers related to the use of stress within multisyllabic words (e.g., saying “IMprint” when “imPRINT” is the more typical stress pattern). Results of this review reveal that researchers have yet to analyze the conditions under which prosody differences contribute to poor social outcomes. We encourage researchers to continue conducting comparative and descriptive studies to shed light on the prosody differences and contexts associated with differential social outcomes. Although the goal is not to alter the prosody behavior of individuals to be commensurate with that of their neurotypical peers, the behavior of socially skilled peers should be described in order to understand which discrepancies could result in decreased reinforcement opportunities for individuals with ASD. Bijou et al. (1968) described the importance of such descriptive field studies for pinpointing variables researchers should manipulate in experimental field studies. For example, researchers could measure and compare the prosody of individuals with ASD who are matched on age, IQ, and expressive language scores, but who differ in social outcomes such as level of employment, relationship status, and level of education. Researchers may gain valuable information from a similar comparison between neurotypical people and people with ASD. Such descriptive assessments would likely identify variables related to social outcomes that warrant further analysis.

Findings of this review inform suggestions for future researchers that orbit around three categories: suggestions for refining measurement techniques, suggestions for analyzing the function of prosody behaviors within the four-term operant contingency, and suggestions for evaluating additional independent variables to change prosody behavior.

Suggestions for Selecting Targets and Measuring Prosody Behavior

Researchers from outside the field of behavior analysis have operationalized and categorized topographical features of speech into measurable units and have developed automated methods for measuring prosody. In order to augment the contribution of behavior analysis to the scientific understanding of prosody, behavior-analytic researchers should refine their operational definitions and measurement systems for prosody.

All but one of the included studies relied on clinical judgment to select the prosody response for intervention. Beaulieu et al. (2014) used a combination of clinical judgment and normative data to select targets for intervention. Clinical judgment is likely sufficient in determining whether some dimensions of prosody are in need of intervention (e.g., latency between words, rate, volume). For other dimensions of prosody (e.g., stress patterns, pitch contours), behavior analysts are advised to gain expertise with objective measures of prosody from colleagues in speech-language pathology to determine whether intervention is warranted and, if so, the point at which they achieve a measurable and meaningful change.

A scientific study of behavior requires the precise measurement of the physical events that compose the behavior (i.e., the behavioral dimension of applied behavior analysis; Baer et al., 1968). Although relevant to the study of prosody, rater assessment of appropriateness is a measure of the observer’s behavior rather than the behavior of the speaker. Ratings of the appropriateness of prosody are commonly used across disciplines (e.g., speech-language pathology: Shriberg et al., 2001; psychology: Paul et al., 2009). By focusing on listener ratings, however, researchers miss the opportunity to identify which dimensions of the speaker’s behavior have a differential effect on the listener. Researchers must tact the physical properties of prosody behavior that alter the function of verbal behavior in order to design interventions that will result in improved listener ratings.

It is possible that behavior analysts have excluded physical properties of prosody from operational definitions because the instruments used to measure sound waves are in the professional purview of speech-language pathology, linguistics, and neurology. Researchers from these fields have developed software to measure, analyze, and display pitch, volume, and stress patterns quickly and reliably. Acoustical spectrographs and other automated measurement methods offer a practical alternative to direct observation of prosody behaviors. For example, Bonneh et al. (2011) analyzed the pitch and volume patterns of individuals with ASD using the VoiceBox speech-processing toolbox (Brookes, 2011). Similarly, Nadig and Shaw (2012) analyzed audio clips using Praat software (available for free download; Boersma & Weenink, 2008). These tools are portable and can be used for data collection in more naturalistic settings. In a case study of transgender voice changes during testosterone therapy, Cler et al. (2020) measured the hertz range of pitch during 3- to 4-hr samples of the participant’s workday using an accelerometer the participant applied to his neck with double-sided tape and a pocket recorder. Incorporating such portable technology in future research would strengthen the behavioral dimension of a scientific evaluation of prosody.

Results of this review indicate that investigators who study prosody typically do not measure physical dimensions of behavior. Krantz (2000) suggested that behavior-analytic researchers may have prioritized other conversational skills over prosody dimensions because of a lack of measurement methods, but the last 20 years gave way to marked advances in software and recording technology. We encourage researchers to consider including measurement technology developed by other fields to improve the behavioral rigor and analytical contributions of their investigations. For example, the Sonneta Voice Monitor 3.0 (MintLeaf Software Inc., 2017) is a mobile application that measures sound pressure level in decibels (e.g., volume) and pitch in hertz and that calculates and displays the average, minimum, maximum, range, and standard deviation for pitch and sound level, as well as the maximum duration of an utterance. Incorporating this technology would allow researchers to operationally define and objectively measure prosody while systematically modifying the environment.

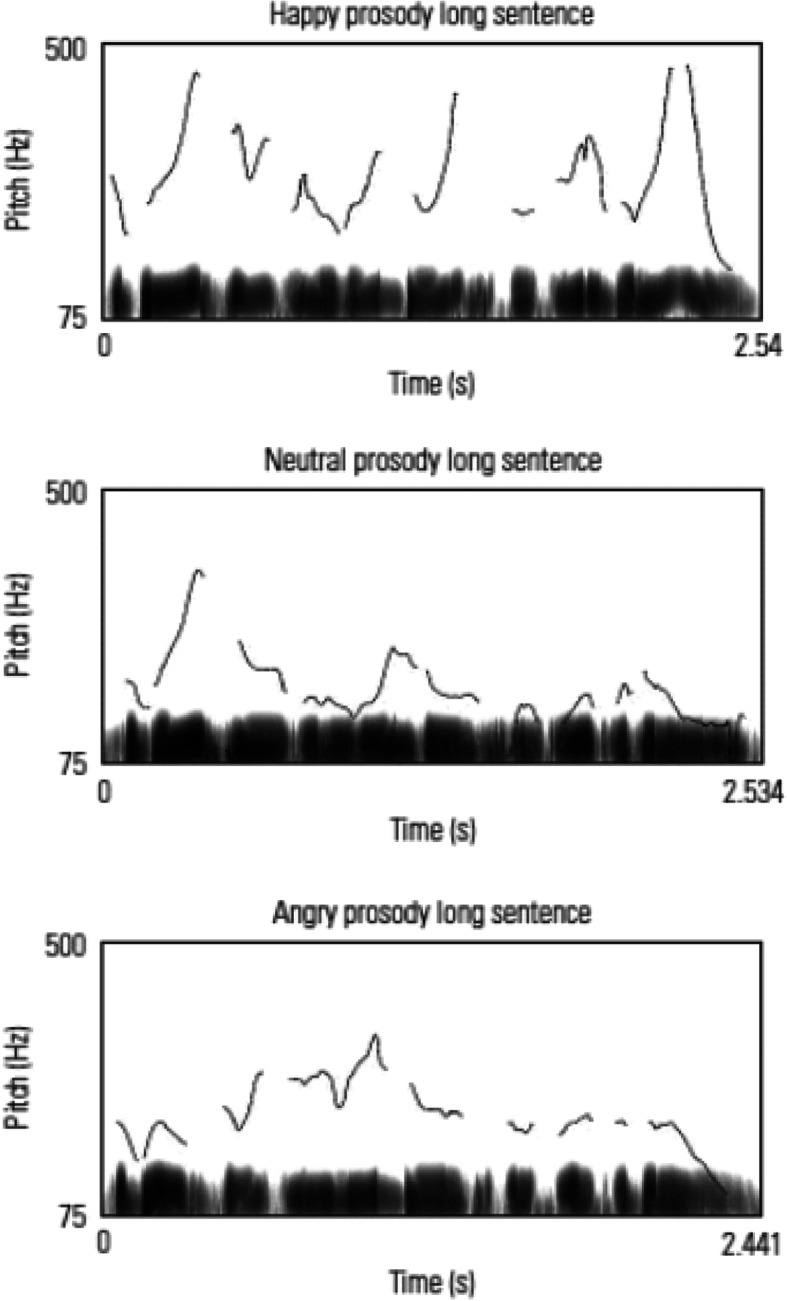

See Fig. 1 for reprinted spectrograms from Chiew and Kjelgaard (2017) as an illustration of how behavior analysts may more objectively describe and display changes in prosody in future research. The purpose of the study was to analyze the accuracy and latency of auditory-visual matching responses between speech samples and icons corresponding to each of the three emotions, comparing results between 13 children with ASD and 17 typically developing children. Each spectrogram illustrates (a) the frequency or sound wave cycles per second (in hertz), interpreted as pitch over time, and (b) the amplitude of sound (the degree of contrast between the black/gray speech signal and white background), interpreted as volume over time. Chiew and Kjelgaard used Praat software and low-pass filtering (i.e., obscuring the words or lexical-semantic content while preserving the prosodic “contours”) on speech samples delivered with angry, neutral, and happy prosody. This technique may also prove useful to behavior analysts who wish to separate the effects of prosody from the topic or word choice when assessing the clinical importance of prosody differences in future research.

Fig. 1.

Spectrograms of prosodic contours for a neurotypical English-language speaker from Chiew and Kjelgaard (2017). Note. From “The Perception of Affective Prosody in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Typical Peers,” by J. Chiew and M. Kjelgaard, 2017, Clinical Archives of Communication Disorders, 2(2), p.133. Chiew and Kjelgaard is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Suggestions for Evaluating the Function of Prosody Behaviors

Researchers who objectively measure prosody then have the opportunity to evaluate various environmental manipulations on prosody and any resulting impact on the social inclusion of individuals with ASD. For example, researchers could evaluate the role of prosody changes on improved employment, educational, or social outcomes for individuals with ASD. We suggest that researchers consider the following assessment and analysis conditions in future studies of prohibitive patterns of prosody behavior.

To better understand the stimulus conditions that discriminate the prosody behavior of socially skilled individuals, researchers could consider measuring the physical dimensions of prosody (e.g., volume and pitch patterns, speech rate, length and timing of pauses) across a variety of antecedent stimulus conditions. For example, to what degree does the pitch of socially skilled individuals vary when talking with a romantic interest compared to talking with a friend or coworker? Data from such a descriptive assessment would help inform when and how a person with ASD can alter their prosody to convey romantic interest. Further, researchers could use information on typical prosody in discrimination training for people with ASD to help bring prosody under appropriate stimulus control (e.g., detecting when a conversation partner may have a romantic vs. a platonic interest). We suggest that applied researchers work toward an understanding of the functional relation between prosody and socially important conditions for individuals with ASD as doing so will facilitate the identification and amelioration of prosody behaviors, allowing individuals with ASD to maximize their valued reinforcers.

Speech-language pathologists have made strides in the measurement and operational definition of prosody responses, and behavior-analytic researchers could capitalize on these gains by incorporating this technology into future research. We suggest that researchers work toward a functional understanding of the naturally occurring controlling variables for prosody behavior of typically developing individuals. Using technology that allows for the in situ measurement of prosody dimensions (e.g., Speak Up for Parkinson’s by Sandcastle is a mobile application that provides visual feedback on voice volume, measured in real time, allowing for objective measurement and in situ adjustment of contingency delivery), researchers could systematically manipulate consequences such as changing the topic or asking questions contingent on changes in prosody. Data yielded from such an analysis would shed light on the autoclitic role that differential prosody serves and facilitate the identification of naturally occurring controlling variables for prosody behavior.

The documented prosody differences between individuals with ASD and their typically developing peers likely contribute to unfavorable social and employment outcomes characteristic of this population, but the functional role of various prosody behaviors under socially important conditions is not currently understood (e.g., getting a job, chatting with a romantic interest and securing a date). We suggest that researchers systematically evaluate the contribution of prosody differences to social integration issues in order to identify dimensions of speech that warrant further analysis. For example, researchers could manipulate physical properties of speech (e.g., pitch contours, volume, rate, pauses between words) using a speech software tool and measure relevant listener responses (e.g., preference for various job candidates, desire to interact with the person socially) as a function of objective prosody changes. Further, the relative contribution of prosody to socially significant outcomes of individuals with ASD could be evaluated by documenting prosody differences in individuals with ASD who do and do not succeed in contacting valuable reinforcers (e.g., securing a job, advocating for themselves, making a date).

Suggestions for Additional Independent Variables to Change Prosody

Researchers who are interested in addressing prosody should continue to develop strategies to make socially significant changes in conversational opportunities and outcomes for people with ASD. We urge researchers to identify and evaluate strategies to enable participants to contact reinforcement across a wide set of stimulus conditions. For example, prosody behaviors correlated with empathetic, enthusiastic, grateful, or assertive emotional states are more or less likely to mediate and produce social reinforcers in certain circumstances. For example, the professional or personal nature of the relationship, the public versus private context for the conversation, and the casual versus sensitive nature of the topic at hand may impact whether prosody with an empathetic affect would evoke the listener’s continued participation or escape responses.

Interventions focused on bringing prosody under appropriate discriminative control will likely increase the social access and quality of life for individuals with ASD. First, researchers could identify the stimulus conditions that discriminate the prosody of socially skilled individuals. Second, researchers could design interventions that establish those stimulus conditions as discriminative stimuli for differential use of specific prosody patterns, increasing the probability of individuals with ASD contacting reinforcement in conversations. Researchers previously established vocal (e.g., Davis et al., 2009; Mason et al., 2012) and nonvocal partner behavior (e.g., Peters & Thompson, 2015) as discriminative stimuli for the conversational responses of young adults and children with ASD. For example, Peters and Thompson (2015) used BST to teach children with ASD two responses (i.e., asking a question and changing the topic) to regain conversation-partner interest. Peters and Thompson established responses to disinterest under the stimulus control of normative nonvocal cues such as yawning or eye rolling. The researchers then differentially reinforced the trained responses with termination of conversation partner disinterest. It is feasible that similar interventions would function to bring prosody behavior under desired stimulus control.

Individuals with ASD would likely benefit from instruction that expands their self-management repertoires, allowing them to tact their own behavior in the moment and to reflect on the effects of their prosody on a listener. Researchers from the fields of audiology and speech-language pathology (e.g., Kalinowski et al., 2004) have developed an ear-level prosthetic device that provides an echo of a person’s own vocal performance at a slight delay. This device has been successful in treating the stuttering behavior of neurotypical adolescents and adults and may be useful in supporting individuals as they learn to tact their own prosody behavior. Many apps have undergone prototype testing to provide feedback on prosody during conversational exchanges (e.g., Sonneta Voice Monitor by MintLeaf Software Inc., 2017). Behavior analysts should consider partnering with app designers in the early stages both to benefit from their technical expertise and to evaluate how feedback from the apps can combine with other treatment components in an efficacious and socially acceptable manner. After searching the literature, we are not aware of experimental evaluations of either of the aforementioned software apps. In addition to pursuing technology-based solutions for problematic prosody, future studies could teach individuals with ASD to solicit feedback from trusted sources on how supportive, empathetic, or interested they seem in particular conversations and to adjust performance based on this feedback.

Teaching generalized imitation of appropriate intonation may be beneficial to improve the conversational access and outcomes of people with ASD. This suggestion comes with a caveat related to ecological validity, as the consequences available for matching intonation likely vary depending on a constellation of partner-provided and environmental-contextual cues. For example, it may be socially acceptable to lower one’s voice volume to a decibel level that is commensurate with a conversation partner under certain conditions, such as when a conversation partner is sharing a secret in a loud room. Conversely, matching the high pitch and rapid rate of speech (i.e., an excited tone) of a conversation partner may be perceived as mocking under certain conditions. Gathering information related to how, when, and why socially skilled individuals use certain prosody in conjunction with the development and evaluation of intervention techniques will facilitate ecologically and socially valid changes in prosody behavior. Although a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of the current review, we suggest that ASD researchers look to innovative methodologies designed to change the prosody behavior of other populations (e.g., second-language learners; Niebuhr et al., 2017).

Finally, readers should interpret the results of this review in light of at least two limitations. First, our focus on the conversational skills of people with Level 1 ASD meant that our search yielded just one example of treatment research with a participant diagnosed with a non-ASD disability (i.e., learning disability not otherwise specified; Beaulieu et al., 2014). Future reviews may extend our findings by including additional search terms related to non-ASD populations that experience long-term concerns with their social repertoires and outcomes (e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; Sciberras et al., 2009). A second limitation of this review is secondary to the wide range of terms that researchers use to describe maladaptive prosody and closely related behaviors; it is possible that our search results were artificially constrained by too narrow a range of search terms. For example, speech-language pathologists have a large literature base of studies addressing pragmatic language deficits of people with ASD (see Parsons et al., 2017, for a review of treatment research with children with ASD). Pragmatic language is a broad term that encompasses communicative, social, and emotional aspects of responding including, for example, nonvocal communication (e.g., proximity between conversation partners, gestures) and social-emotional attunement (attending to others’ emotions and responding with appropriate affect). Parsons et al. (2017) included the term “prosody” in their description of documented pragmatic language deficits of adolescents with ASD from Paul et al. (2009). Due to overlapping and evolving terms used to describe the conversational deficits of people with ASD, the present review may have omitted relevant experiments that used the broader term “pragmatic language” yet targeted one or more dimensions of prosody. One bit of evidence that lends support to this hypothesis is that we identified 25% of our included studies by reviewing the reference lists from other included studies.

In summary, Mesibov (1992) and Van Bourgondien and Woods (1992) anecdotally reported that it is the vocal presentation of individuals with ASD that most immediately creates an impression of “oddness.” Treating prosody differences may help some people with ASD communicate more effectively, increasing their access to socially mediated opportunities and reinforcers in school, leisure, and work contexts. Results of this review demonstrate that socially significant changes in prosody behavior can result from carefully arranged learning environments. Therefore, we encourage researchers to build on the work of prior investigators and to continue developing conceptually systematic and socially valid prosody interventions for people with Level 1 ASD. Those who contribute to a scientific understanding of prosody may very well identify functional relations with generality to additional populations for whom prosody may limit personally important reinforcers (e.g., individuals who stutter) and contexts (e.g., employment, leadership, negotiating, and advocacy).

Author Note

Charlotte Mann https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4372-4394 is now at the University of St. Joseph. Amanda Karsten is now at Grand Valley State University. We thank Dr. Rachel Thompson, Dr. David Palmer, and Dr. Greg Hanley for their comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Charlotte C. Mann prepared this manuscript, supervised by Amanda M. Karsten, in partial fulfillment of requirements for the doctor of philosophy degree at Western New England University.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There were no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

No human subjects served as participants for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.) 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 91–97. 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu L, Hanley GP, Santiago JL. Improving the conversational skills of a college student with peer-mediated behavioral skills training. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s40616-013-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijou SW, Peterson RF, Ault MH. A method to integrate descriptive and experimental field studies at the level of data and empirical concepts. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(2):175–191. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2008). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 5.0.35) [Computer program]. https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/

- Brookes, M. (2011). VOICEBOX: Speech Processing Toolbox for MATLAB. http://www.ee.ic.ac.uk/hp/staff/dmb/voicebox/voicebox.html

- Bonneh YS, Levanon Y, Dean-Pardo O, Lossos L, Adini Y. Abnormal speech spectrum and increased pitch variability in young autistic children. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2011;4:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper JK, Leonard R. Understanding voice problems: A physiological perspective for diagnosis and treatment. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charlop, M. H., Dennis, B., Carpenter, M. H., & Greenberg, A. L. (2010). Teaching socially expressive behaviors to children with autism through video modeling. Education and Treatment of Children, 33(3), 371–393. 10.1353/etc.0.0104

- Chiew J, Kjelgaard M. The perception of affective prosody in children with autism spectrum disorders and typical peers. Clinical Archives of Communication Disorders. 2017;2(2):128–141. doi: 10.21849/cacd.2017.00157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cler GJ, McKenna VS, Dahl KL, Stepp CE. Longitudinal case study of transgender voice changes under testosterone hormone therapy. Journal of Voice. 2020;34(5):748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J, Mo Y, Baek S. The role of syntactic structure in guiding prosody perception with ordinary listeners and everyday speech. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2010;25(7–9):1141–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2019.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler A, Ladd DR, editors. Prosody: Models and measurements. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Daou N, Vener SM, Poulson CL. Analysis of three components of affective behavior in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014;8(5):480–501. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KM, Boon RT, Cihak DF, Fore C. Power cards to improve conversational skills in adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2009;25(1):12–22. doi: 10.1177/1088357609354299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Degand L, Simon AC. Mapping prosody and syntax as discourse strategies: How basic discourse units vary across genres. In: Barth-Weingarten D, Dehe N, Wichmann A, editors. Where prosody meets pragmatics. Emerald Group Publishing; 2009. pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- Dotson WH, Leaf JB, Sheldon JB, Sherman JA. Group teaching of conversational skills to adolescents on the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010;4(2):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filipe MG, Frota S, Castro SL, Vicente SG. Atypical prosody in Asperger syndrome: Perceptual and acoustic measurements. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(8):1972–1981. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, D. L., Kroeger, R. A., & Stroope, S. (2020). Autism spectrum disorder symptoms and bullying victimization among children with autism in the United States. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 560–571. 10.1007/s10803-019-04282 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gena A, Couloura S, Kymissis E. Modifying the affective behavior of preschoolers with autism using in-vivo or video modeling and reinforcement contingencies. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35(5):545–556. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grob, C. M., Lerman, D. C., Langlinais, C. A., & Villante, N. K. (2019). Assessing and teaching job-related social skills to adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(1), 150–172. 10.1002/jaba.503 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grossman RB, Bemis RH, Skwerer DP, Tager-Flusberg H. Lexical and affective prosody in children with high-functioning autism. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010;53(3):778–793. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagland C, Webb Z. Working with adults with Asperger syndrome: A practical toolkit. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JHL, Patil S. Speech under stress: Analysis, modeling, and recognition. In: Muller C, editor. Speaker classification. Springer; 2007. pp. 108–137. [Google Scholar]

- Haskins BG, Silva JA. Asperger’s disorder and criminal behavior: Forensic-psychiatric considerations. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online. 2006;34(3):374–384. doi: 10.1080/13218710902887483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itahashi, S., Zhou, J. X., & Tanaka, K. (1994). Spoken language discrimination using speech fundamental frequency. [Paper presentation] Third International Conference on Spoken Language Processing, Yokohama, Japan. https://www.isca-speech.org/archive/archive_papers/icslp_1994/i94_1899.pdf

- Kalathottukaren RT, Purdy SC, Ballard E. Prosody perception and production in children with hearing loss and age-and gender-matched controls. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2017;28(4):2832–2894. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski J, Guntupalli VK, Stuart A, Saltuklaroglu T. Self-reported efficacy of an ear-level prosthetic device that delivers altered auditory feedback for the management of stuttering. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2004;27(2):167–170. doi: 10.1097/01.mrr.0000128063.76934.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2(3), 217–250. [PubMed]

- Kazdin AE. Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings. 2. Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel, R. L., & Frea, W. D. (1993). Treatment of social behavior in autism through the modification of pivotal social skills. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(3), 369–377. 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Koegel LK, Park MN, Koegel RL. Using self-management to improve the reciprocal social conversation of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(5):1055–1063. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1956-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz PJ. Commentary: Interventions to facilitate socialization. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(5):411–413. doi: 10.1023/A:1005595305911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf JB, Tsuji KH, Griggs B, Edwards A, Taubman M, McEachin J, Leaf R, Oppenheim-Leaf ML. Teaching social skills to children with autism using the cool versus not cool procedure. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;47(2):165–175. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JH, Purdy SC, Tippett LJ, Leao SH. Affective speech prosody perception and production in stroke patients with left-hemispheric damage and healthy controls. Brain and Language. 2017;166:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman AM, Cooper FS, Shankweiler DP, Studdert-Kennedy M. Perception of the speech code. Psychological Review. 1967;74(6):431–461. doi: 10.1037/h0020279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little, L. (2001). Peer victimization of children with Asperger spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(9), 995–996. 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Pickles A, Rutter M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30(3):205–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1005592401947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CC, Karsten AM. Efficacy and social validity of procedures for improving conversational skills of college students with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(1):402–421. doi: 10.1002/jaba.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RA, Rispoli M, Ganz JB, Boles MB, Orr K. Effects of video modeling on communicative social skills of college students with Asperger syndrome. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2012;15(6):425–434. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2012.704530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine A, Plexico LW, Plumb AM, Cleary J. Prosody in young verbal children with autism spectrum disorder. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science & Disorders. 2014;41:120–132. doi: 10.12963/csd.15256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mesibov, G. B. (1992). Treatment issues with high-functioning adolescents and adults with autism. In High-functioning individuals with autism (pp. 143-155). Springer, Boston, MA.

- MintLeaf Software Inc. (2017). Sonneta voice monitor (Version 3.0) [Mobile app]. https://sonneta-voice-monitor-ios.soft112.com/

- Nadig, A., & Shaw, H. (2012). Acoustic and perceptual measurement of expressive prosody in high-functioning autism: Increased pitch range and what it means to listeners. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42 (4), 499–511. 10.1007/s10803-011-1264-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nakai Y, Takashima R, Takiguchi T, Takada S. Speech intonation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Brain and Development. 2014;36(6):516–522. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr, O., Alm, M. H., Schümchen, N., & Fischer, K. (2017). Comparing visualization techniques for learningsecond language prosody: first results. International Journal of Learner Corpus Research, 3(2), 250–277. 10.1075/ijlcr.3.2.07nie

- Nuernberger JE, Ringdahl JE, Vargo KK, Crumpecker AC, Gunnarsson KF. Using a behavioral skills training package to teach conversation skills to young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7(2):411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmen A, Didden R, Arts M. Improving question asking in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Effectiveness of small group training. Autism. 2008;12(1):83–98. doi: 10.1177/1362361307085265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer DC. A call for tutorials on alternative approaches to the study of verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1999;16:49–55. doi: 10.1007/BF03392947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons L, Cordier R, Munro N, Joosten A, Speyer R. A systematic review of pragmatic language interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(4):Article e0172242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick NJ. Social skills for teenagers and adults with Asperger syndrome: A practical guide to day-to-day life. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Paul R, Augustyn A, Klin A, Volkmar F. Perception and production of prosody by speakers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:205–220. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-1999-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R, Shriberg LD, McSweeney J, Cicchetti D, Klin A, Volkmar F. Brief report: Relations between prosodic performance and communication and socialization ratings in high functioning speakers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35(6):861–869. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R, Orlovski SM, Marcinko HC, Volkmar F. Conversational behaviors in youth with high-functioning ASD and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:115–125. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0607-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppe S, McCann J, Gibbon F, O’Hare A, Rutherford M. Receptive and expressive prosodic ability in children with high-functioning autism. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;50:1015–1028. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/071). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters LC, Thompson RH. Teaching children with autism to respond to conversation partners’ interest. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48(3):544–562. doi: 10.1002/jaba.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder-Amaker, S. (2014). Identifying the unmet needs of college students on the autism spectrum. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 22(2), 125–137. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000032 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Radley KC, Ford WB, McHugh MB, Dadakhodjaeva K, O’Handley RD, Battaglia AA, Lum JD. Brief report: Use of superheroes social skills to promote accurate social skill use in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45:3048–3054. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendle-Short J. Managing interaction: A conversation analytic approach to the management of interaction by an 8 year-old girl with Asperger’s syndrome. Issues in Applied Linguistics. 2002;13(2):161–186. doi: 10.5070/L4132005061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell P. Lower, slower, louder: Vocal cues of sarcasm. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2000;29:483–495. doi: 10.1023/A:1005120109296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler RT, Brolin DE, Johnson JM. Factors affecting employment success quality of life: A one year follow-up of students in special education. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals. 1990;13(2):95–107. doi: 10.1177/088572889001300201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sansosti FJ, Powell-Smith KA. Using computer-presented social stories and video models to increase the social communication skills of children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2008;10(3):162–178. doi: 10.1177/1098300708316259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scattone D. Enhancing the conversation skills of a boy with Asperger’s disorder through Social Stories™ and video modeling. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(2):395–400. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfstein LA, Beidel DC, Sims VK, Finnell LR. Social skills deficits and vocal characteristics of children with social phobia or Asperger’s disorder: A comparative study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:865–875. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C, Stichter JP. The use of peer-mediated interventions to promote the generalization of social competence for adolescents with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s syndrome. Exceptionality. 2012;20(2):94–113. doi: 10.1080/09362835.2012.669303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sciberras E, Roos LE, Efron D. Review of prospective longitudinal studies of children with ADHD: Mental health, educational, and social outcomes. Current Attention Disorders Reports. 2009;1(4):171–177. doi: 10.1007/s12618-009-0024-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck-Hufnagel S, Turk AE. A prosody tutorial for investigators of auditory sentence processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1996;25(2):193–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01708572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Kwiatkowski J, Rasmussen C. Prosody-Voice Screening Profile (PVSP): Scoring forms and training materials. Communication Skill Builders; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Paul R, McSweeny JL, Klin A, Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR. Speech and prosody characteristics of adolescents and adults with high-functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44:1097–1115. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/087). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman, M. (1988). Tactics of scientific research: Evaluating data in psychology. Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies.

- Simmons ES, Paul R, Shic F. Brief report: A mobile application to treat prosodic deficits in autism spectrum disorder and other communication impairments: A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(1):320–327. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Selection by consequences. Science. 1981;213(4507):501–504. doi: 10.1126/science.7244649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow S, Balla D, Ciccetti D. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Survey Form) American Guidance Service; 1984. [Google Scholar]