Abstract

We report the isolation and characterization of a member of the family Enterobacteriaceae isolated from the gallbladder pus of a food handler. Conventional biochemical tests suggested Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi, but the isolate agglutinated with poly(O), 2O, 9O, and Vi Salmonella antisera but not with poly(H) or any individual H Salmonella antisera. 16S rRNA gene sequencing showed that there were two base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Montevideo, four base differences between the isolate and serotype Typhi, five base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium, and six base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Dublin, indicating that the isolate was a strain of S. enterica. Electron microscopy confirmed that the isolate was aflagellated. The flagellin gene sequence of the isolate was 100% identical to that of the H1-d flagellin gene of serotype Typhi. Sequencing of the rfbE gene, which encoded the CDP-tyvelose epimerase of the isolate, showed that there was a point mutation at position +694 (G→T), leading to an amino acid substitution (Gly→Cys). This may have resulted in a protein of reduced catalytic activity and hence the presence of both 2O and 9O antigens. We therefore concluded that the isolate was a variant of serotype Typhi. Besides antibiotic therapy and cholecystectomy, removal of all stones in the biliary tree was performed for eradication of the carrier state.

Despite the success of using the new “gold standard” of 16S rRNA sequencing for the classification and identification of bacterial strains in most bacterial genera (9, 12), most strains of Salmonella are classified under the species Salmonella enterica, as the number of base differences between different Salmonella strains is minimal (1). To date there is no good genotypic standard for classification within S. enterica, and further classification of S. enterica into serotypes is defined phenotypically by the possession of various somatic, flagellar, and capsular antigens. Therefore it is difficult to identify strains with ambiguous serotypic profiles and it is sometimes controversial to define a strain with an ambiguous serotypic profile as a new serotype or a variant of an existing serotype (5). In the present study, we describe the characterization of a Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi variant isolated from a patient with acute cholecystitis and cholangitis by a combination of conventional microbiological tests, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, electron microscopic study, flagellin gene sequencing, and CDP-tyvelose epimerase (rfbE) gene sequencing. The clinical and public health implications are also discussed.

All clinical data were collected prospectively as described in a previous publication (7). Clinical specimens were collected and handled according to standard protocols, and all suspect colonies were identified by standard conventional biochemical methods (8). In addition, the Vitek System (bioMerieux Vitek, Hazelwood, Mo.), the API system (bioMerieux Vitek), and the ATB Expression system (bioMerieux Vitek) were used for the identification of the bacterial isolate in this study.

Bacterial DNA extraction was modified from the previously published protocol (13). Briefly, 80 μl of NaOH (0.05 M) was added to 20 μl of bacterial cells suspended in distilled water and the mixture was incubated at 60°C for 45 min followed by the addition of 6 μl of Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), achieving a final pH of 8.0. The resultant mixture was diluted 100 times, and 5 μl of the diluted extract was used for PCR. PCR amplification and DNA sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene were performed according to the methods of previous publications (2, 14, 15). The bacterial DNA extract and control were amplified with 0.5 μM primers (LPW57, 5′-AGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′; LPW58, 5′-AGGCCCGGGAACGTATTCAC-3′) (Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.). The PCR product was gel purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). Both strands of the PCR product were sequenced twice with an ABI 377 automated sequencer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) using the PCR primers (LPW57 and LPW58) and additional primers designed from the sequencing data of the first round of sequencing reactions (LPW69, 5′-AGCACCGGCTAACTCCGT-3′; LPW70, 5′-AGTTTTAACCTTGCGG-3′). PCR amplification and DNA sequencing of the flagellin gene were performed according to a published protocol (4). The bacterial DNA extract and control were amplified and sequenced with oligonucleotide primers (LPW164, 5′-CAAGTCATTAATACAAACAGCC-3′; LPW165, 5′-TTAACGCAGTAAAGAGAGGAC-3′) (Gibco BRL). PCR amplification and DNA sequencing of the rfbE gene were performed according to a published protocol (11). The bacterial DNA extract and control were amplified and sequenced with oligonucleotide primers (LPW198, 5′-TGAAGTTGGTAGTGGAGAGG-3′; LPW199, 5′-TCCTCACGTCAGCTTCATCT-3′) (Gibco BRL). The sequences of the PCR products were compared with known 16S rRNA, flagellin, and rfbE gene sequences in the GenBank database by multiple sequence alignment using the CLUSTAL W program (10).

A 63-year-old Chinese man was admitted to the hospital in January 2000 because of right upper quadrant pain of the abdomen for 1 day. Examination showed that he was afebrile (37.1°C), with tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen and a positive Murphy's sign (interruption of the patient's deep inspiration when the physician's fingers were pressed deeply below the right costal margin). The hemoglobin was 14.0 g/dl; the total white cell count was 16.1 × 109/liter with 89.4% neutrophil, 5.5% lymphocyte, and 5.0% monocyte; and the platelet count was 166 × 109/liter. The serum bilirubin was 30 μmol/liter, alkaline phosphatase was 131 U/liter, alanine aminotransferase was 349 U/liter, and aspartate aminotransferase was 198 U/liter. The serum urea, creatinine, albumin, and globulin levels were within normal limits. Ultrasound examination of the hepatobiliary system revealed a liver of normal size and echogenicity. The gallbladder was distended (12 cm in length), with a stone seen in the neck of it. The intrahepatic ducts were prominent. The sonographic Murphy's sign was positive. A clinicoradiological diagnosis of acute cholecystitis and cholangitis was made. Blood culture was taken and empirical intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5 g every 8 h) was administered.

Emergency cholecystectomy and exploration of the biliary tree were performed on the day after admission. A histological section of the gallbladder wall showed features of acute on chronic cholecystitis with prominent mucosal infoldings, Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses, and thickened blood vessels. There were also foci of mucosal ulceration and polymorph infiltration. Pus from the gallbladder was sent for bacterial culture. A gram-negative, nonmotile rod with colonies 4 mm in diameter was recovered on blood agar, chocolate agar, and MacConkey agar after 24 h of incubation at 37°C in ambient air. It fermented glucose, reduced nitrate, and did not produce cytochrome oxidase, typical of a member of the Enterobacteriaceae family. Standard conventional biochemical tests, the Vitek system (GNI+) (bioMerieux Vitek), the API system (20E) (bioMerieux Vitek), and the ATB Expression system (ID 32 GN) (bioMerieux Vitek) all showed that the biochemical profile of the strain was compatible with serotype Typhi (Table 1). However, the isolate agglutinated with poly(O), 2O (by tube agglutination with antiserum diluted to 1:320) and 9O (by tube agglutination with antiserum diluted to 1:160), and Vi Salmonella antisera (Murex Biotech Ltd., Temple Hill, Dartford, United Kingdom) but not with poly(H) or any individual H Salmonella antisera. A scanning electron micrograph of the gallbladder pus isolate showed straight, slender, aflagellated rods. The strain was sensitive to ampicillin, cephalothin, cefuroxime, gentamicin, cotrimoxazole, ciprofloxacin, cefoxitin, ceftriaxone, piperacillin-tazobactam, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ceftazidime, amikacin, and imipenem. Blood culture was negative. Piperacillin-tazobactam was continued for a total of 14 days. Two consecutive stool cultures performed 48 h after the cessation of the antibiotic were negative. The patient has remained asymptomatic up to the time of writing, 240 days from discharge.

TABLE 1.

Biochemical profile and identification of the gallbladder pus isolate from a patient with acute cholecystitis and cholangitis by conventional biochemical tests and the ATB ID 32 GN, Vitek GNI+, and API 20E systems

| Biochemical reaction or enzyme | Presence (+) or absence (−) of reaction or enzyme by:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional test | ATB ID 32 GN | Vitek GNI+ | API 20E | |

| Nitrate reduction | + | + | ||

| β-galactosidase | − | − | − | |

| Arginine dihydrolase | − | − | − | |

| Lysine decarboxylase | + | + | + | |

| Ornithine decarboxylase | − | − | − | |

| Utilization of: | ||||

| Citrate | − | − | − | |

| Malonate | − | − | − | |

| Acetamide | − | |||

| Propionate | − | |||

| Caprate | − | |||

| Valerate | − | |||

| Histidine | − | |||

| 2-Ketogluconate | − | |||

| 3-Hydroxybutyrate | − | |||

| 4-Hydroxybenzonate | − | |||

| Proline | + | |||

| N-Acetylglucosamine | + | |||

| Itaconate | − | |||

| Suberate | − | |||

| Acetate | − | |||

| Lactate | + | |||

| Alanine | − | |||

| 5-Ketogluconate | − | |||

| Glycogen | − | |||

| 3-Hydroxybenzoate | + | |||

| Serine | + | |||

| H2S | + | + | + | |

| Urease | − | − | − | |

| Tryptophan deaminase | − | − | ||

| Indole | − | − | ||

| Acetoin | − | |||

| Gelatinase | − | |||

| Glucose fermentation | + | |||

| Glucose oxidation | + | + | ||

| Fermentation or oxidation of: | ||||

| Glucose | + | + | ||

| Mannitol | + | + | + | + |

| Inositol | − | − | − | − |

| Sorbitol | + | + | + | + |

| Rhamnose | − | − | − | − |

| Sucrose | − | − | − | − |

| Melibiose | + | + | + | |

| Amygdalin | − | |||

| Arabinose | − | − | − | − |

| Lactose | − | − | ||

| Maltose | + | + | + | |

| Xylose | + | + | ||

| Raffinose | − | − | ||

| Adonitol | − | − | ||

| Dulcitol | − | |||

| Fucose | − | |||

| Ribose | + | |||

| Salicin | − | − | ||

| Indoxyl-β-d-glucoside metabolism | − | |||

| Glucose fermentation in the presence of p-coumaric | + | |||

| Esculin hydrolysis | − | |||

| Polymyxin B resistance | − | |||

| 2,4,4′-Trichloro-2′-hydroxydiphenylether resistance | − | |||

| Identification (S. enterica serotype) | Typhi | Typhi (95.2%) | Typhi (99%) | Typhi (99.9%) |

PCR of the 16S rRNA gene of the bacteria showed a band at 1,381 bp. There were 2 base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Montevideo (GenBank accession no. AF227867), 4 base differences between the isolate and serotype Typhi (GenBank accession no. Z47544), 5 base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium (GenBank accession no. AF227869), 6 base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Dublin (GenBank accession no. AF227868), 13 base differences between the isolate and Salmonella species (GenBank accession no. X80676), 25 base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Paratyphi A (GenBank accession no. U88546), 25 base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Paratyphi C (GenBank accession no. U88548), and 29 base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis (GenBank accession no. U90318), indicating that the isolate was a strain of S. enterica.

PCR of the flagellin gene of the bacteria showed a band at 1,515 bp. There was no base difference between the flagellin gene sequence of the isolate and that of serotype Typhi (GenBank accession no. L21912), and there were 33 base differences between the isolate and Salmonella enterica serotype Muenchen (ATCC 8388) (GenBank accession no. X03395), showing that the flagellin gene of the isolate is the same as the H1-d flagellin gene of serotype Typhi.

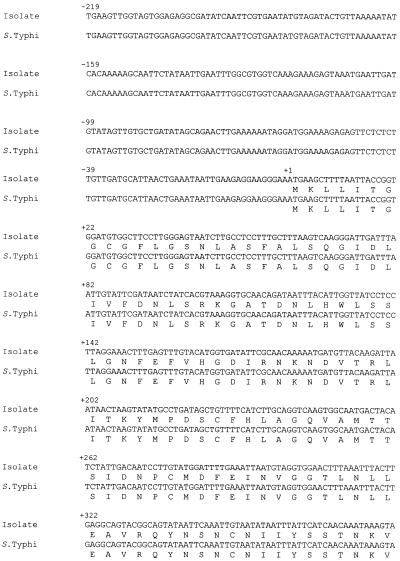

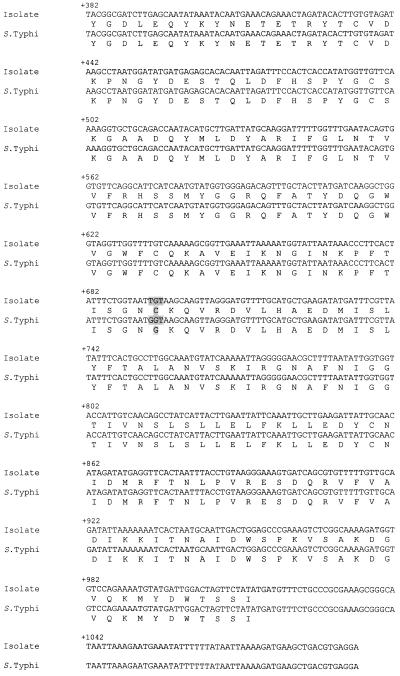

PCR of the rfbE gene of the bacteria showed a band at 1,313 bp. The base sequences and the deduced amino acid sequences of the purified bands and the corresponding regions in serotype Typhi (GenBank accession no. M29682) are shown in Fig. 1. There was a point mutation at position +694 (G→T), changing the codon in the isolate from GGT to TGT, and hence there was an amino acid substitution (Gly→Cys).

FIG. 1.

Base sequences and deduced amino acid sequences of purified bands from PCR and the corresponding regions in serotype Typhi. A point mutation at position +694 (G→T) changed the codon in the isolate from GGT to TGT and caused an amino acid substitution (Gly→Cys).

The gold standard for identification of serotype Typhi relies on both biochemical and serological methods. In the presence of contradictory phenotypic findings, a wrong diagnosis can lead to undesirable clinical or public health consequences. In this study, we used genotypic methods to further characterize a Salmonella strain isolated from the gallbladder pus of a patient with acute cholecystitis and cholangitis. Conventional biochemical tests as well as all three commercially available kits showed that the isolate was compatible with serotype Typhi. However, there were several phenotypic characteristics that were contrary to the identity of serotype Typhi. The isolate was nonmotile, which was subsequently confirmed by a lack of flagella, using electron microscopy, and a lack of flagellar antigens. Furthermore, the isolate reacted with 2O antiserum, which should not occur with serotype Typhi. Further genotypic tests were then performed to define the speciation of the isolate and whether it was a novel serotype of S. enterica or just a variant of serotype Typhi. 16S rRNA gene sequencing confirmed that the isolate was S. enterica. Although the isolate did not possess any flagella, flagellin gene sequencing showed that the isolate actually possessed the H1-d flagellin gene, which showed 100% base identity with the sequence of the H1-d flagellin gene of serotype Typhi. Furthermore, rfbE gene sequencing showed that the isolate possessed an rfbE gene mutant, which could explain why it was both 2O and 9O positive. Based on the combination of the results of these phenotypic and genotypic tests, we conclude that the isolate was a variant of serotype Typhi rather than a new serotype of S. enterica.

Variations of the flagellar antigen in serotype Typhi have been described in the literature. Recently, in one report, four nonmotile strains of serotype Typhi were described (4). Restriction fragment length polymorphism of the fliC gene in all four strains revealed a pattern similar to that of the flagellin gene of serotype Typhi, showing that flagellin genes were indeed present in the isolates. Three of the isolates were H−, whereas the fourth was rough. Besides a complete absence of flagellar antigen, another variant of serotype Typhi, found only in Indonesia, has also been described (5). In this variant, instead of the H1-d antigen, it possessed the H1-j antigen. The authors attributed this to a deletion of 261 bp in the central antigenic determinant part in the H1-d flagellin gene, due to an intragenic recombination involving an 11-bp direct repeat. In addition, some of the Indonesia variants also possessed an additional flagellar antigen, z66, although the nature of this antigen was not well characterized.

We speculate that the possession of both 2O and 9O somatic antigens in our isolate can be due to a mutant CDP-tyvelose epimerase with reduced activity. Group A and group D strains of Salmonella have paratose and tyvelose, respectively, as the immunodominant sugar in their somatic antigens, which are otherwise identical (11). They differ only in the final steps in the biosynthesis of the sugars. Paratose synthase (encoded by rfbS), present in both groups A and D, catalyzes the final step in the synthesis of CDP-paratose. CDP-tyvelose epimerase, active only in group D strains, in turn converts CDP-paratose to CDP-tyvelose. rfbE is present in a mutant form in group A strains, in which the gene sequences were identical to that of rfbE except for the loss of one of four consecutive thymine residues, leading to a frameshift mutation and premature termination, accounting for the absence of CDP-tyvelose epimerase in group A strains. In our gallbladder pus isolate, there was a point mutation in the rfbE gene, leading to an amino acid substitution (Gly→Cys) from a nonpolar to a polar amino acid. This may result in a partially active CDP-tyvelose epimerase, which can convert some CDP-paratose to CDP-tyvelose, leading to the presence of both 2O and 9O somatic antigens.

The identification of the organism in this study was important because it would have major clinical and public health implications. If the organism was a strain of nontyphoidal Salmonella, the patient was suffering only from an ordinary acute cholecystitis and cholangitis caused by a member of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Antibiotic treatment and cholecystectomy would be sufficient. On the other hand, if the organism was a serotype Typhi adapted solely to humans (as it was in our patient), the patient had typhoidal salmonellosis and was probably a chronic serotype Typhi carrier. Besides antibiotic therapy and cholecystectomy, removal of all stones in the biliary tree should be performed for eradication of the carrier state (6), as residual stones may act as footholds for the serotype Typhi due to bacterial biofilm formation. Furthermore, eradication of the serotype Typhi must be confirmed by two consecutive negative stool cultures as the patient had to handle and prepare food while working at a construction site.

The lack of a single genotypic “gold standard” for classification within S. enterica will remain a problem in the near future. Classification by 16S rRNA sequences showed limited usefulness below the species level. It has been shown that 23S rRNA sequences are more variable and can be used to separate the diphasic serotypes S. enterica subspecies I and VI from the monophasic serotypes subspecies IIIa and IV (3). However, further classification within subspecies was difficult. Although the flagellar gene(s) may be sequenced as in the present study, genotypic definitions of somatic antigens are much more difficult, as carbohydrate variations often involve a whole cascade of genes. In the future, when more sequence data for the various Salmonella serotypes are available, the use of DNA chip technology may enable the construction of an oligonucleotide array consisting of multiple flagellin genes as well as genes encoding the various enzymes for the synthesis of the somatic antigens. Then genotypic classification of serotypes may be made possible.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA, flagellin, and rfbE gene sequences of the S. enterica strain in the present study were submitted to GenBank and given accession numbers AF332600, AF332601, and AF332602, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the Committee of Research and Conference Grants, The University of Hong Kong.

We thank Raymond Tsang for his invaluable advice on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brenner F W, Villar R G, Angulo F J, Tauxe R, Swaminathan B. Salmonella nomenclature. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2465–2467. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2465-2467.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheuk W, Woo P C Y, Yuen K Y, Yu P H, Chan J K C. Intestinal inflammatory pseudotumor with regional lymph node involvement: identification of a new bacterium as the etiologic agent. J Pathol. 2000;192:289–292. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH767>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen H, Nordentoft S, Olsen J E. Phylogenetic relationships of Salmonella based on rRNA sequences. J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:605–610. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dauga C, Zabrovskaia A, Grimont P A D. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of some flagellin genes of Salmonella enterica. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2835–2843. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2835-2843.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frankel G, Newton S M C, Schoolnik G K, Stocker B A D. Intragenic recombination in a flagellin gene: characterization of the H1-j gene of Salmonella Typhi. EMBO J. 1989;8:3149–3152. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freitag J L. Treatment of chronic typhoid carrier by cholecystectomy. Public Health. 1973;32:869. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luk W K, Wong S S Y, Yuen K Y, Ho P L, Woo P C Y, Lee R A, Chau P Y. Inpatient emergencies encountered by an infectious disease consultative service. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:695–701. doi: 10.1086/514591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen G J, Woese C R. Ribosomal RNA: a key to phylogeny. FASEB J. 1993;7:113–123. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.8422957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verma N, Reeves P. Identification and sequence of rfbS and rfbE, which determine antigenic specificity of group A and group D Salmonellae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5694–5701. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5694-5701.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woese C R. There must be a prokaryote somewhere: microbiology's search for itself. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:1–9. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.1-9.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woo P C Y, Lo C Y, Lo S K, Siau H, Peiris J S M, Wong S S Y, Luk W K, Chan T M, Lim W W, Yuen K Y. Distinct genotypic distributions of cytomegalovirus (CMV) envelope glycoprotein in bone marrow and renal transplant recipients with CMV disease. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:515–518. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.5.515-518.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woo P C Y, Leung P K L, Leung K W, Yuen K Y. Identification by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing of an Enterobacteriaceae species from a bone marrow transplant recipient. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:211–215. doi: 10.1136/mp.53.4.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo P C Y, Tsoi H W, Leung K W, Lum P N L, Leung A S P, Ma C H, Kam K M, Yuen K Y. Identification of Mycobacterium neoaurum isolated from a neutropenic patient with catheter-related bacteremia by 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3515–3517. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3515-3517.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]