Abstract

BACKGROUND

Ampullary adenocarcinoma (AAC) is a rare neoplasm that accounts for only 0.2% of all gastrointestinal cancers. Its incidence rate is lower than 6 cases per million people. Different prognostic factors have been described for AAC and are associated with a wide range of survival rates. However, these studies have been exclusively conducted in patients originating from Asian, European, and North American countries.

AIM

To evaluate the histopathologic predictors of overall survival (OS) in South American patients with AAC treated with curative pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD).

METHODS

We analyzed retrospective data from 83 AAC patients who underwent curative (R0) PD at the National Cancer Institute of Peru between January 2010 and October 2020 to identify histopathologic predictors of OS.

RESULTS

Sixty-nine percent of patients had developed intestinal-type AAC (69%), 23% had pancreatobiliary-type AAC, and 8% had other subtypes. Forty-one percent of patients were classified as Stage I, according to the AJCC 8th Edition. Recurrence occurred primarily in the liver (n = 8), peritoneum (n = 4), and lung (n = 4). Statistical analyses indicated that T3 tumour stage [hazard ratio (HR) of 6.4, 95% confidence interval (CI) of 2.5-16.3, P < 0.001], lymph node metastasis (HR: 4.5, 95%CI: 1.8-11.3, P = 0.001), and pancreatobiliary type (HR: 2.7, 95%CI: 1.2-6.2, P = 0.025) were independent predictors of OS.

CONCLUSION

Extended tumour stage (T3), pancreatobiliary type, and positive lymph node metastasis represent independent predictors of a lower OS rate in South American AAC patients who underwent curative PD.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal neoplasms, Adenocarcinoma, Ampulla, Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Survival, South America

Core Tip: The pancreatobiliary type of ampullary adenocarcinoma, lymph node metastasis and T3 tumour stage (AJCC 8th Ed) are risk factors for lower overall survival in a South American population.

INTRODUCTION

Ampullary adenocarcinoma (AAC) is a rare neoplasm that represents 0.2% of all gastrointestinal cancers[1,2]. AAC has better prognosis and resection rates than pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)[3,4]. This may be partly explained by the early symptom of jaundice caused by its location in the ampulla of Vater[5,6]. Nevertheless, three different epithelia (duodenal, biliary, and pancreatic) are present in the ampullary region[7], and their derived malignancies display different clinical behaviours[8]. Kimura and colleagues classified AAC into two histologic subtypes: Pancreatobiliary (PB) and intestinal (INT)[9]. Other features, such as preoperative CA 19-9[7], imaging[10], molecular phenotype[11,12], genetic mutations[13-15], and the diagnosis and classification of AAC[16], have been correlated with overall survival (OS). Consequently, the anatomic paradigm has shifted towards the interaction between genetic and epigenetic factors that determine OS and relapse-free survival (RFS)[14,17]. This may explain the wide range of outcomes reported in different centres (5-year OS: 30%-70%)[2].

However, most of these studies have been conducted in European, Asian, and North American countries. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has evaluated the impact of the lymph node ratio in predicting OS among AAC patients in Latin America[18]. Therefore, we evaluated the histopathologic predictors in AAC patients who underwent curative pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) at the National Cancer Institute of Peru.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient selection

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in patients diagnosed with AAC who underwent curative (R0) PD between January 2010 and October 2020 at our tertiary centre. We specifically analysed histopathologic factors that influenced the patients’ overall survival. Our institutional review board approved this study (Protocol Number 21-17), according to the Declaration of Helsinki[19].

Histopathology

Double reads in a blinded manner by pathologists specializing in hepatobiliary cancers were applied to ensure the diagnosis of AAC and classification into INT intestinal (INT)- and pancreatobiliary (PB)-type according to Kimura et al[9,20].

Morphologically, INT-type tumours are reminiscent of colorectal adenocarcinoma, with solid nests, tall columnar cells, and elongated pseudostratified nuclei[21]. A significant proportion of INT-type is related to intestinal adenomas, which correlates with the adenoma-carcinoma sequence[22]. Conversely, PB-type adenocarcinomas are similar to extrahepatic bile duct and pancreatic duct adenocarcinomas. The glandular units have more pleomorphism than the intestinal type, with no evident nuclear pseudostratification, and they are separated by stroma[21]. Additionally, a mixed subtype has been described as having more than 25% of each INT and PB differentiation or with hybrid features, such as intestinal architecture with pancreatobiliary cytology[23,24]. Immunohistochemistry has led to a better classification of this mixed subtype; nevertheless, a standard definition has not been established[24,25]. In the present study, the following antibodies were used to determine the dominant type: MUC1 (#6151, BioSB, California, United States), MUC2 (#6158, BioSB, California, United States), CDX2 (MAD-000645QD-12, Vitro S.A., Spain), CK20 (MAD-0005105QD-12, Vitro S.A., Spain), and MUC5AC (MAD-000434QD-12, Vitro S.A., Spain). In cases of no definite conclusion, the tumour was classified as tubular into “other subtypes”.

Resection was classified as R0 when the 1-mm width of the surgical margin was free of neoplastic cells[26]. Tumour and nodal staging were categorized according to the AJCC 8th Edition.

PD

PD was considered the treatment of choice because it was demonstrated to be a more radical approach to achieve satisfactory lymph node clearance and tumour-free surgical margins[27]. Patients were eligible for surgery after a comprehensive evaluation. The clinical parameters included performance and nutritional status, anatomy, and tumour extension (evaluated with contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging). CA19-9 Levels were monitored within one month before surgery. We also assessed the vascular structures of the mesenteric and celiac axes along the diameter of the pancreatic duct.

Our surgical approach has been described previously[28]. In brief, the procedure was carried out using level 2 mesopancreas resection[29], and the pancreatic stump was managed using Blumgart, duct-to-mucosa, or modified dunking (at the discretion of the surgeon). In all cases, two Blake drains were placed around the pancreaticojejunostomy. Prophylactic octreotide was not used. External stents were applied in patients with a high risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula[30].

Adjuvant therapy

Patients with adjuvant therapy (AT) were interpreted as those who received chemotherapy (two or more courses), radiotherapy (with or without a sensitizing chemotherapy drug), or a combination of both. The AT regimen was left at the discretion of treating physicians, according to the best evidence available and/or institutional protocol.

Patient follow-up

Follow-ups and patient check-ups were performed on postoperative days 15, 30, and 90. computed tomography (CT) scans and CA 19-9 tests were scheduled every 4 mo after the index procedure during the first year, every 6 mo during the second year, and annually from the third year onward. The National Database for Civil Status (RENIEC) was solicited to determine the fate of patients. OS (months) was monitored from the date of surgery to the date of death or last follow-up, and patients with no events were censored. Any event (recurrence or death) was recorded during the follow-up. The cut-off for the last follow-up was 60 mo.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as medians (interquartile ranges), and categorical variables were reported as counts (percentages). For the univariate analysis, the log-rank test was used, and the histopathologically relevant variables were integrated into a Cox regression model. Statistical analyses were performed with an alpha significance level of 0.05 using IBM SPSS v.25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Study population

From 2010 to 2020, 297 PDs were performed at the National Cancer Institute of Peru. Patients with R1/R2 resection, unavailable slides for revision, incomplete medical records, or synchronic neoplasms were excluded from the study. All patients included in the study underwent R0 resection. After a thorough revision of the medical files, 83 patients were included in the present study. Clinical, laboratory, and operative patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median age of the patient cohort was 59 years [interquartile range (IQR), 49-67], with a predominance of women (ratio = 1.3). The mean follow-up time was 39 mo. Twenty-five patients (30%) died during the follow-up period.

Table 1.

Clinical, laboratory and operative patient characteristics (n = 83)

| Clinical, laboratory and operative patient characteristics (n = 83) | |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 59 (49–67) |

| Sex, male/female, n (%) | 36 (43)/47 (57) |

| Perioperative transfusion, n (%) | 21 (25) |

| Haemoglobin in g/L, median (IQR) | 115 (108–127) |

| Platelet count in 109/L, median (IQR) | 285 (243–372) |

| International Normalized Ratio, median (IQR) | 1.06 (1.01–1.15) |

| Serum glucose in mmol/L, median (IQR) | 5.1 (4.8–5.7) |

| Serum creatinine in mmol/L, median (IQR) | 53 (47–65) |

| Serum albumin in g/L, median (IQR) | 38.1 (32–41.1) |

| Serum total bilirubin in µmol/L, median (IQR) | 23.9 (12.9–60) |

| Serum CA 19-9 in IU/mL, median (IQR) | 26.3 (10–91.4) |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | |

| Pylorus-preserving PD, n (%) | 69 (83) |

| Whipple procedure, n (%) | 14 (17) |

IQR: Interquartile range; PD: Pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Histopathologic characteristics

Sixty-nine percent of patients had developed INT-type AAC (69%), 23% PB-type AAC, and 8% other subtypes (including five patients with the tubular subtype and two patients with the tubular subtype with signet ring cells). Approximately 40% of cases demonstrated pancreatic invasion (T3 tumour stage), and 40% of patients had lymph node metastasis. Thirty-four (41%), 20 (24%), and 29 (35%) patients had stage I, II, and III disease, respectively. The histopathological characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Histopathologic characteristics (n = 83)

| Histopathologic characteristics (n = 83) | |

| Tumour size in mm, median (IQR) | 27 (17–40) |

| Subtype, n (%) | |

| Intestinal | 57 (69) |

| Pancreatobiliary | 19 (23) |

| Others | 7 (8) |

| Tumour status, n (%) | |

| T1 | 7 (8) |

| T2 | 44 (53) |

| T3 | 32 (39) |

| Number of lymph nodes assessed, median (IQR) | 17 (12–24) |

| Lymph node status, n (%) | |

| N0 | 50 (60) |

| N1 | 22 (26) |

| N2 | 11 (14) |

| Differentiation, n (%) | |

| Well differentiated | 25 (30) |

| Moderately differentiated | 53 (64) |

| Poorly differentiated | 5 (6) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 30 (36) |

| Perineural invasion | 26 (31) |

IQR: Interquartile range.

Use of AT

Twenty-four patients received AT (15 patients underwent chemotherapy, two patients underwent radiotherapy, and seven patients were subjected to both treatments). The most frequently employed chemotherapy regimen included gemcitabine, which was administered to 20 patients (24%). When chemoradiotherapy was applied, a dose of 4500 cGy in 25 sessions was administered using capecitabine as a sensitizing agent.

The evaluation of AT on OS was impaired by the heterogeneity of the AT regimen and the number of patients. Therefore, we decided not to include the AT variable in the survival analysis.

Patterns of recurrence

Recurrent distant metastases were diagnosed during the postoperative period in the liver (n = 12), peritoneum (n = 8), and lung (n = 7). Additionally, lymph node recurrences around the superior mesenteric artery and the retroperitoneal space were primarily observed in one and two patients, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recurrence patterns after pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 19)

|

Organs involved

|

|

||||

|

Distant metastasis, n (%)

|

(A) First organ

|

(B) Second organ

|

(C) Third organ

|

A + B + C

|

%

|

| Liver | 8 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 32 |

| Peritoneum | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 22 |

| Lung | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 19 |

| Supraclavicular lymph node | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Bone | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Suprarenal gland | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Sub-table total | 30 | 81 | |||

| Lymph nodal recurrence, n (%) | |||||

| Celiac trunk | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Hepatic hilum | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Mesenteric lymph nodes | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |

| Retroperitoneal lymph nodes | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | |

| Sub-table total | 7 | 19 | |||

| Total | 37 | 100 | |||

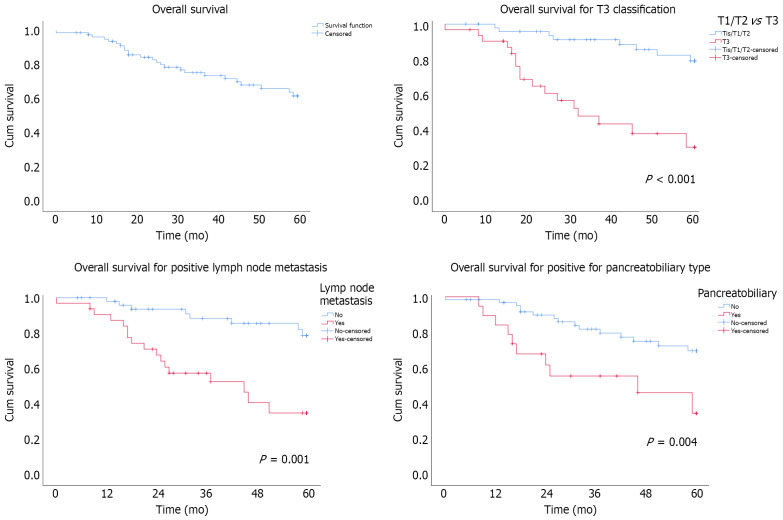

Overall survival and prognostic factors

The 5-year OS rate in the cohort was 62% (Figure 1). Applying the Cox regression model, three predictive factors were identified, i.e., T staging, lymph node metastasis, and PB type. Time and outliers had no impact on these independent factors, according to the modelling Supplementary Figures (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Survival probability of patients with adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Table 4.

Cox regression model analysis for predictors of overall survival

| Variables | Hazard ratio |

95%CI

|

P value | |

|

Lower

|

Upper

|

|||

| Age in yr | 0.355 | |||

| Tumour size in mm | 1.03 | 1 | 1.06 | 0.059 |

| Histopathologic subtype | ||||

| Intestinal/other types | ||||

| Pancreatobiliary type | 2.7 | 1.2 | 6.2 | 0.025 |

| T classification | ||||

| T1-T2 | ||||

| T3 | 6.4 | 2.5 | 16.3 | < 0.001 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 4.5 | 1.8 | 11.3 | 0.001 |

| Differentiation grade | 0.54 | |||

| Well differentiated | ||||

| Moderately differentiated | 0.268 | |||

| Poorly differentiated | 0.755 | |||

| Perineural invasion | 0.517 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.26 | |||

CI: Confidence interval.

Impact of the T tumour classification

Univariate analysis showed lower OS in patients with T3 classification (P < 0.001). The 5-year OS rates were 80% in T1/T2 patients and 30% in T3 patients, with a median OS of 30% in the latter group. According to the multivariate analysis, T3 patients had an HR of 6.4 (95%CI: 2.5-16.3, P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Effect of lymph node invasion

Patients with lymph node metastases (N+) had a lower survival rate than those with no lymph node invasion (N0) (P = 0.001). The 5-year OS rates in the N+ and N0 groups were 38% and 80%, respectively. The median OS was 46 mo in the N+ group. The HR was 4.5 (95%CI: 1.8-11.3, P = 0.001) (Figure 1).

Influence of the histopathologic subtype

PB-type patients had a lower OS than patients with INT or other subtypes (P = 0.004). The 5-year OS rate for PB-type patients was 38%, whereas patients with INT or other subtypes had a 5-year OS rate of 70%. The median OS was 46 mo in PB-type patients, whereas the OS in the intestinal/other group was not reached during the follow-up period. The HR was 2.7 (95%CI: 1.2-6.2, P = 0.025) in PB-type patients (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, the present study represents the first retrospective histopathologic work on AAC performed in a tertiary centre in South America, in which PD and the multimodal approach are standard. Our findings indicate that T3 tumour classification (pancreatic invasion), positive lymph node metastasis, and PB type are independent prognostic factors of OS in AAC patients treated with PD (R0).

Various factors have previously been described to be associated with AAC patient outcomes. In a meta-analysis, Zhou and colleagues identified age (> 65 years old), tumour size (> 20 mm), poor differentiation, PB-type, pT3-T4 stage diseases, lymph node metastasis, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, pancreatic invasion, and positive surgical margins as independent factors associated with lower survival[32]. However, Koprowski and colleagues claimed that histotypes were not correlated with OS and concluded that disease stage was the primary determinant of patient outcomes[33]. In this study, the authors report 32% locoregional recurrence, despite the median number of retrieved lymph nodes and the low number of patients with R1 resection. Moreover, Quero and collaborators recently corroborated this finding about no difference between INT- and PB-types, but higher overall and recurrence-free survivals with excision of the mesopancreas[34].

Since AT allocation is based on tumour and nodal stages, we decided to consider these variables in the Cox model. We further stratified the patient cohort according to histopathologic subtypes (i.e., INT, PB, and "others"). Of note, we did not observe the mixed subtype in our cohort from South America, contrasting with the studies published in other regions of the world[16,31].

Our model supports the predictive impact of the histology of AAC on survival in a patient cohort from South America. In our hands, PB type, pT3 stage, and lymph node metastases were associated with lower OS; other variables scrutinized were not significantly associated with OS. The low rate of locoregional recurrence reported in our cohort could be partly explained by the application of level 2 mesopancreas resection, in accordance with the data by Quero and collaborators[34].

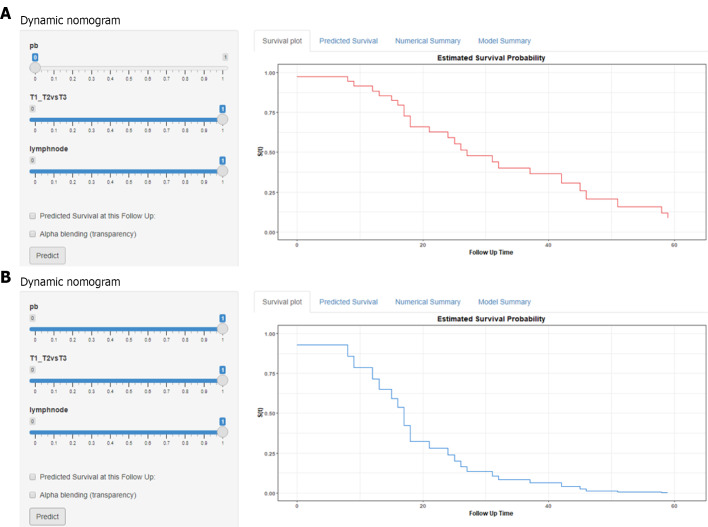

AAC has been documented to have a better prognosis than PDAC. However, the present study suggests that there are detrimental factors associated with subgroups of AAC patients, with OS rates comparable to PDAC (Figure 2). In this regard, our data suggest that a better outcome would be primarily explained by the biology of the tumour and secondarily by its location. Hence, assessing the impact of AT in high-risk patients is of utmost relevance. In the ESPAC-3 study, which included 428 patients with periampullary adenocarcinoma, the use of chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil /leucovorin or gemcitabine) demonstrated a benefit in OS (HR 0.75) but no greater effectiveness based on the histological type[35]. Additionally, a multicentre retrospective analysis did not report any benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in AAC patients, including those with high-risk criteria (N+ or advanced stages T3 and T4)[36]. Other studies have provided more contrasting results on the impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on OS[31,37-39]. Regarding adjuvant radiotherapy, benefits have essentially been analysed among PDAC patients, preventing definite conclusions in AAC patients[40-42]. A recent meta-analysis showed that AT, especially chemoradiotherapy, was associated with increased OS among patients with PB-type or high-risk factors[43].

Figure 2.

Comparison of survival probability between the intestinal/other (A) and pancreaticobiliary (B) types in patients with pT3 and pN+ adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater.

There is a lack of specific guidelines for AAC, except one that comprises the management of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas[44]. The authors recommend AT in patients with high-risk features (pancreatic invasion, lymph node metastasis, and perineural invasion) but did not specify any regimen. The predictive ability of mutation driver mutations (e.g., TP53, KRAS, and ELF3) in AAC histotypes has not been studied in great detail[45]. The characterization of AAC patient subgroups, based on their molecular alterations, would provide information on the choice of AT after radical surgery.

There are some limitations to recognize in the present study. Our primary AAC patient population displayed a high perioperative mortality rate (10 patients were excluded from this study), which we addressed and analysed previously[28]. We consider this a very important drawback, in addition to the retrospective design of the study. Another weakness was the heterogeneity in the multimodal management of the patients, which is reflected in international practices[31,39,46]. Therefore, we decided not to evaluate the impact of AT, as few patients would have been included in each group. Accordingly, further prospective studies are required because of the limited evidence available to date.

CONCLUSION

PB type, T3 tumour stage, and positive lymph node metastasis are independent predictors of lower survival in South American patients with ampullary adenocarcinoma treated by curative pancreaticoduodenectomy. Further evaluation of adjuvant and multimodal treatments is warranted, especially in patients with these high-risk factors.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Ampullary adenocarcinoma (AAC) is a rare neoplasm that has not been studied previously in South American countries.

Research motivation

AAC might have different patterns of recurrence and overall survival than what has been reported in centres from Europe, Asia or North America.

Research objectives

To identify risk factors and their impact on overall survival in patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for AAC.

Research methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study and analysed histopathologic predictors of survival in a Cox regression model.

Research results

Nearly two-thirds of patients had the intestinal-type AAC and around 25% had the Pancreatobiliary (PB)-type AAC. However, overall survival (OS) was lower for the latter subtype. Independently of the T3 and N+ tumour stage.

Research conclusions

Patients with PB-type AAC, T3 and N+ tumour stage are at higher risk of lower survival after curative PD.

Research perspectives

Identification of high-risk patients would guide the clinicians for the use of AT. Further studies are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Pr. Lorenzo-Bermejo J for his valuable support in the review of the statistical methods.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: Our institutional review board approved this study (Protocol Number 21-17), according to the Declaration of Helsinki19.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was waived by the IRB (IRB No. 21-17).

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflicts of interest to be declared.

Data sharing statement: According to the institutional policy, no data from our patients would be shared.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: May 10, 2021

First decision: August 9, 2021

Article in press: January 13, 2022

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Peru

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Andrejic-Visnjic B, Mirshahi M, Yamada T S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Ramiro Manuel Fernandez-Placencia, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Section, Department of Abdominal Surgery, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru. ramirofp02@gmail.com.

Paola Montenegro, Department of Medical Oncology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Melvy Guerrero, Department of Pathology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Mariana Serrano, Department of Medical Oncology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Emperatriz Ortega, Department of Medical Oncology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Mercedes Bravo, Department of Pathology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Lourdes Huanca, Department of Pathology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Stéphane Bertani, International Joint Laboratory of Molecular Anthopological Oncology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru; Unite Pharmacochim & Pharmacol Dev, UMR152, F-31062 Toulouse, France.

Juan Manuel Trejo, Department of Radiation Oncology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Patricia Webb, Department of Pathology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Jenny Malca-Vasquez, Department of Radiation Oncology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Luis Taxa, Department of Pathology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Alberto Lachos-Davila, Department of Radiation Oncology, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Juan Celis-Zapata, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Section, Department of Abdominal Surgery, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Carlos Luque-Vasquez, Department of Abdominal Surgery, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Eduardo Payet, Department of Abdominal Surgery, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Eloy Ruiz, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Section, Department of Abdominal Surgery, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

Francisco Berrospi, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Section, Department of Abdominal Surgery, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplasicas, Lima 15038, Peru.

References

- 1.Askew J, Connor S. Review of the investigation and surgical management of resectable ampullary adenocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:829–838. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, Manunga J Jr, Tomlinson JS, Reber HA, Ko CY, Hines OJ. Survival after resection of ampullary carcinoma: a national population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1820–1827. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9886-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron JL, He J. Two thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandrasegaram MD, Chiam SC, Chen JW, Khalid A, Mittinty ML, Neo EL, Tan CP, Dolan PM, Brooke-Smith ME, Kanhere H, Worthley CS. Distribution and pathological features of pancreatic, ampullary, biliary and duodenal cancers resected with pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:85. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0498-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommerville CAM, Limongelli P, Pai M. Survival analysis after pancreatic resection for ampullary and pancreatic head carcinoma: An analysis of clinicopathological factors. J Surg Oncol . 2009;100:651–656. doi: 10.1002/jso.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris-Stiff G, Alabraba E, Tan YM, Shapey I, Bhati C, Tanniere P, Mayer D, Buckels J, Bramhall S, Mirza DF. Assessment of survival advantage in ampullary carcinoma in relation to tumour biology and morphology. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okano K, Oshima M, Yachida S, Kushida Y, Kato K, Kamada H, Wato M, Nishihira T, Fukuda Y, Maeba T, Inoue H, Masaki T, Suzuki Y. Factors predicting survival and pathological subtype in patients with ampullary adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:156–162. doi: 10.1002/jso.23600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng-Pywell R, Reddy S. Ampullary Cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99:357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura W, Futakawa N, Yamagata S. Different Clinicopathologic Findings in Two Histologic Types of Carcinoma of Papilla of Vater. Japanese J Cancer Res . 1994;85:161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1994.tb02077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoen H, Kim JH, Hur BY, Ahn SJ, Jeon SK, Choi SY, Lee KB, Han JK. Prediction of tumor recurrence and poor survival of ampullary adenocarcinoma using preoperative clinical and CT findings. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:2433–2443. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overman MJ, Soifer HS, Schueneman AJ, Ensor J Jr, Adsay V, Saka B, Neishaboori N, Wolff RA, Wang H, Schnabel CA, Varadhachary G. Performance and prognostic utility of the 92-gene assay in the molecular subclassification of ampullary adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:668. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2677-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schueneman A, Goggins M, Ensor J, Saka B, Neishaboori N, Lee S, Maitra A, Varadhachary G, Rezaee N, Wolfgang C, Adsay V, Wang H, Overman MJ. Validation of histomolecular classification utilizing histological subtype, MUC1, and CDX2 for prognostication of resected ampullary adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:64–68. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shroff S, Overman MJ, Rashid A, Shroff RT, Wang H, Chatterjee D, Katz MH, Lee JE, Wolff RA, Abbruzzese JL, Fleming JB. The expression of PTEN is associated with improved prognosis in patients with ampullary adenocarcinoma after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1619–1626. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0418-OA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim BJ, Jang HJ, Kim JH, Kim HS, Lee J. KRAS mutation as a prognostic factor in ampullary adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis and review. Oncotarget. 2016;7:58001–58006. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valsangkar NP, Ingkakul T, Correa-Gallego C, Mino-Kenudson M, Masia R, Lillemoe K. D, Fernández-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL, Liss AS, Thayer SP. Survival in ampullary cancer: potential role of different KRAS mutations. Surg (United States) . 2015;157:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.08.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asano E, Okano K, Oshima M, Kagawa S, Kushida Y, Munekage M, Hanazaki K, Watanabe J, Takada Y, Ikemoto T, Shimada M, Suzuki Y Shikoku Consortium of Surgical Research (SCSR) Phenotypic characterization and clinical outcome in ampullary adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:119–127. doi: 10.1002/jso.24274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park HM, Park SJ, Han SS, Hong SK, Hong EK, Kim SW. Very early recurrence following pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with ampullary cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e17711. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lino-Silva LS, Gómez-Álvarez MA, Salcedo-Hernández RA, Padilla-Rosciano AE, López-Basave HN. Prognostic importance of lymph node ratio after resection of ampullary carcinomas. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9:1144–1149. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2018.07.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura W, Futakawa N, Zhao B. Neoplastic diseases of the papilla of Vater. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s00534-004-0894-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowitz Lothe IM, Kleive D, Pomianowska E, Cvancarova M, Kure E, Dueland S, Gladhaug IP, Labori KJ. Clinical relevance of pancreatobiliary and intestinal subtypes of ampullary and duodenal adenocarcinoma: Pattern of recurrence, chemotherapy, and survival after pancreatoduodenectomy. Pancreatology. 2019;19:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lisita Rosa VD, Maris Peria F, Ottoboni Brunaldi M. Carcinoma of Ampulla of Vater: Carcinogenesis and Immunophenotypic Evaluation. J Clin Epigenetics. 2017;03(03):1-5. DOI:10.21767/2472-1158.100059. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmermann C, Wolk S, Aust DE, Meier F, Saeger HD, Ehehalt F, Weitz J, Welsch T, Distler M. The pathohistological subtype strongly predicts survival in patients with ampullary carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12676. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49179-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ang DC, Shia J, Tang LH, Katabi N, Klimstra DS. The utility of immunohistochemistry in subtyping adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1371–1379. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F, Shen D, Ma Y, Song Q, Wang H. Identification of ampullary carcinoma mixed subtype using a panel of six antibodies and its clinical significance. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119:295–302. doi: 10.1002/jso.25311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verbeke CS, Menon KV. Redefining resection margin status in pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:282–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amini A, Miura JT, Jayakrishnan TT, Johnston FM, Tsai S, Christians KK, Gamblin TC, Turaga KK. Is local resection adequate for T1 stage ampullary cancer? HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:66–71. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez-Placencia R, Berrospi-Espinoza F, Uribe-Rivera K, Medina-Cana J, Chavez-Passiuri I, Sanchez-Bartra N, Paredes-Galvez K, Luque-Vasquez Vasquez C, Celis-Zapata J, Ruiz-Figueroa E. Preoperative Predictors for 90-Day Mortality after Pancreaticoduodenectomy in Patients with Adenocarcinoma of the Ampulla of Vater: A Single-Centre Retrospective Cohort Study. Surg Res Pract . 2021;2021:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2021/6682935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue Y, Saiura A, Yoshioka R, Ono Y, Takahashi M, Arita J, Takahashi Y, Koga R. Pancreatoduodenectomy With Systematic Mesopancreas Dissection Using a Supracolic Anterior Artery-first Approach. Ann Surg. 2015;262:1092–1101. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ecker BL, McMillan MT, Asbun HJ, Ball CG, Bassi C, Beane JD, Behrman SW, Berger AC, Dickson EJ, Bloomston M, Callery MP, Christein JD, Dixon E, Drebin JA, Castillo CF, Fisher WE, Fong ZV, Haverick E, Hollis RH, House MG, Hughes SJ, Jamieson NB, Javed AA, Kent TS, Kowalsky SJ, Kunstman JW, Malleo G, Poruk KE, Salem RR, Schmidt CR, Soares K, Stauffer JA, Valero V, Velu LKP, Watkins AA, Wolfgang CL, Zureikat AH, Vollmer CM Jr. Characterization and Optimal Management of High-risk Pancreatic Anastomoses During Pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2018;267:608–616. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moekotte AL, Malleo G, van Roessel S, Bonds M, Halimi A, Zarantonello L, Napoli N, Dreyer SB, Wellner UF, Bolm L, Mavroeidis VK, Robinson S, Khalil K, Ferraro D, Mortimer MC, Harris S, Al-Sarireh B, Fusai GK, Roberts KJ, Fontana M, White SA, Soonawalla Z, Jamieson NB, Boggi U, Alseidi A, Shablak A, Wilmink JW, Primrose JN, Salvia R, Bassi C, Besselink MG, Abu Hilal M. Gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy in subtypes of ampullary adenocarcinoma: international propensity score-matched cohort study. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1171–1182. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou YM, Liao S, Wei YZ, Wang SJ. Prognostic factors and benefits of adjuvant therapy for ampullary cancer following pancreatoduodenectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Surg. 2020;43:1133–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Affi Koprowski M, Sutton TL, Brinkerhoff BT, Grossberg A, Sheppard BC, Mayo SC. Oncologic outcomes in resected ampullary cancer: Relevance of histologic subtype and adjuvant chemotherapy. Am J Surg. 2021;221:1128–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quero G, Fiorillo C, De Sio D, Laterza V, Menghi R, Cina C, Schena CA, Rosa F, Galiandro F, Alfieri S. The role of mesopancreas excision for ampullary carcinomas: a single center propensity-score matched analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2021;23:1557–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2021.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neoptolemos JP, Moore MJ, Cox TF, Valle JW, Palmer DH, McDonald AC, Carter R, Tebbutt NC, Dervenis C, Smith D, Glimelius B, Charnley RM, Lacaine F, Scarfe AG, Middleton MR, Anthoney A, Ghaneh P, Halloran CM, Lerch MM, Oláh A, Rawcliffe CL, Verbeke CS, Campbell F, Büchler MW European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid or gemcitabine vs observation on survival in patients with resected periampullary adenocarcinoma: the ESPAC-3 periampullary cancer randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:147–156. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim HS, Jang JY, Yoon YS, Park SJ, Kwon W, Kim SW, Han HS, Han SS, Park JS, Yoon DS. Does adjuvant treatment improve prognosis after curative resection of ampulla of Vater carcinoma? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2020;27:721–730. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamarajah SK. Adjuvant radiotherapy following pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary adenocarcinoma improves survival in node-positive patients: a propensity score analysis. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:1212–1218. doi: 10.1007/s12094-018-1849-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ecker BL, Vollmer CM Jr, Behrman SW, Allegrini V, Aversa J, Ball CG, Barrows CE, Berger AC, Cagigas MN, Christein JD, Dixon E, Fisher WE, Freedman-Weiss M, Guzman-Pruneda F, Hollis RH, House MG, Kent TS, Kowalsky SJ, Malleo G, Salem RR, Salvia R, Schmidt CR, Seykora TF, Zheng R, Zureikat AH, Dickson PV. Role of Adjuvant Multimodality Therapy After Curative-Intent Resection of Ampullary Carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:706–714. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narang AK, Miller RC, Hsu CC. Evaluation of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy for ampullary adenocarcinoma: The Johns Hopkins Hospital - Mayo Clinic collaborative study. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:126. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Regalla DKR, Jacob R, Manne A, Paluri RK. Therapeutic options for ampullary carcinomas. A review. Oncol Rev. 2019;13:440. doi: 10.4081/oncol.2019.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonet M, Rodrigo A, Vázquez S, Carrizo V, Vilardell F, Mira M. Adjuvant therapy for true ampullary cancer: a systematic review. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22:1407–1413. doi: 10.1007/s12094-019-02278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miura JT, Jayakrishnan TT, Amini A, Johnston FM, Tsai S, Erickson B, Quebbeman EJ, Christians KK, Evans DB, Gamblin TC, Turaga KK. Defining the role of adjuvant external beam radiotherapy on resected adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of vater. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:2003–2008. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vo NP, Nguyen HS, Loh EW, Tam KW. Efficacy and safety of adjuvant therapy after curative surgery for ampullary carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg (United States) . 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kondo S, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Miyakawa S, Tsukada K, Nagino M, Furuse J, Saito H, Tsuyuguchi T, Yamamoto M, Kayahara M, Kimura F, Yoshitomi H, Nozawa S, Yoshida M, Wada K, Hirano S, Amano H, Miura F Japanese Association of Biliary Surgery; Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery; Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. Guidelines for the management of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas: surgical treatment. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:41–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mafficini A, Amato E, Cataldo I, Rusev BC, Bertoncello L, Corbo V, Simbolo M, Luchini C, Fassan M, Cantù C, Salvia R, Marchegiani G, Tortora G, Lawlor RT, Bassi C, Scarpa A. Ampulla of Vater Carcinoma: Sequencing Analysis Identifies TP53 Status as a Novel Independent Prognostic Factor and Potentially Actionable ERBB, PI3K, and WNT Pathways Gene Mutations. Ann Surg. 2018;267:149–156. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chavez MT, Sharpe JP, O'Brien T, Patton KT, Portnoy DC, VanderWalde NA, Deneve JL, Shibata D, Behrman SW, Dickson PV. Management and outcomes following pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2017;214:856–861. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]