Keywords: microglia, LOAD, Alzheimer's, TREM2

Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by the presence of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), neuronal and synaptic loss and inflammation of the central nervous system (CNS). The majority of AD research has been dedicated to the understanding of two major AD hallmarks (i.e. Aβ and NFTs); however, recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) data indicate neuroinflammation as having a critical role in late-onset AD (LOAD) development, thus unveiling a novel avenue for AD therapeutics. Recent evidence has provided much support to the innate immune system's involvement with AD progression; however, much remains to be uncovered regarding the role of glial cells, specifically microglia, in AD. Moreover, numerous variants in immune and/or microglia-related genes have been identified in whole-genome sequencing and GWAS analyses, including such genes as TREM2, CD33, APOE, API1, MS4A, ABCA7, BIN1, CLU, CR1, INPP5D, PICALM and PLCG2. In this review, we aim to provide an insight into the function of the major LOAD-associated microglia response genes.

1. Background

1.1. Late-onset Alzheimer's disease and immune risk

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disorder and the most prevalent cause of dementia. It is currently estimated to affect more than 5 million people and is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States [1]. Likely beginning decades before symptoms of cognitive impairment first manifest, AD pathology is classified by the accumulation of extracellular amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and intracellular hyper-phosphorylated tau tangles. Underlying these hallmarks are glial cell activation and neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction and ultimately neurodegeneration and brain atrophy [2]. Until recently, neuroinflammation and innate immune activation were assumed to play a purely responsive role to AD pathology; however, recent genomic data have provided a framework of support for the causative role of immune cells in AD development.

Generally, AD can be classified into two groups based on the age of onset. Less than 1–2% of AD cases are of a familial nature and can present as early onset before the age of 65 with a rapid onset of disease progression [3,4]. Identification of these familial mutations in amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin-1 (PSEN1, the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase involved in APP cleavage) has provided immense insight into disease aetiology [5]. Conversely, the majority of AD cases are classified as sporadic or late-onset AD (LOAD), affecting individuals greater than 65 years of age. Age is the biggest risk factor for developing LOAD [6,7]. In addition, the presence of recently identified LOAD-risk alleles has shown to play a significant role in AD development, with a heritability estimate of 60–80% [8].

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and genetic linkage studies over the past decade have helped identify numerous allelic loci associated with LOAD. The alleles identified in these studies are more common in the general population but are less penetrant and confer a smaller risk of developing AD, as compared to familial AD mutations [9,10]. These studies, as well as early histological data from patient brain tissue, have provided considerable evidence for the involvement and activation of the immune system in AD pathology [11,12]. Moreover, recent whole-genome sequencing methods have highlighted many immune-related genes and variants as risk factors for AD, including TREM2, CD33, APOE, API1, MS4A, ABCA7, BIN1, CLU, CR1, INPP5D, PICALM and PLCG2. Of the more than 40 identified risk variants for AD, a majority of risk alleles are enriched in myeloid and microglia cell enhancers, underscoring significant microglial involvement in AD disease progression (figure 1) [13–19]. While identified variants confer only a small contribution to AD compared to AD risk genes APP and PSEN1, these studies emphasize the significance of microglial involvement in disease development [10,13]. Genomic and functional studies indicate that microglia not only play a reactionary role in AD pathology, but also are themselves a causative factor in initial AD development and progression.

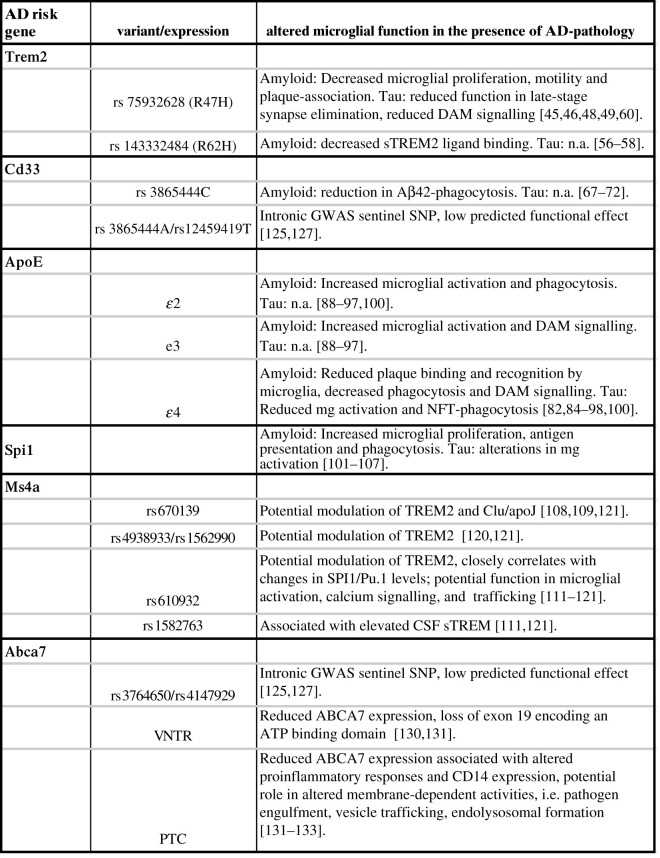

Figure 1.

AD risk variants and associated effect on altered microglial function in the presence of AD pathology. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DAM, disease-associated microglia; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

However, while genetic data are critical for the initial identification of microglial involvement in AD, research remains necessary to unveil specific functions through which these cells confer risk for AD. Since the identification of these microglial-related LOAD-associated genes, much research has gone into providing insight into the function of these genes. Ultimately, understanding microglial-specific roles in AD will allow for the development of novel disease-modifying therapies. This review aims to provide functional insight into LOAD-associated microglial genes.

1.2. Microglia in AD

Microglia, the brain-resident macrophages, play critical roles in central nervous system (CNS) innate immunity. Microglia are key players in the immune response, which can be briefly summarized as (i) initial pathogen surveillance, (ii) phagocytosis and (iii) degradation and responsive signalling [20–22]. Functional studies highlight various genes as they contribute to these distinct processes within the immune response and further, changes in protein function throughout different stages of disease progression.

Recent studies have been directed at unveiling the distinct ways in which microglia are involved in AD-related immune processes. As stated previously, microglial contribution to AD can be summarized into distinct stages, the first of which is initial pathogen surveillance. This first step is initiated when distinct signalling molecules (i.e. pathogens, dystrophic neurites, protein aggregates) identify and bind target-recognizing receptors (i.e. TREM2, CD33) on microglia. Distinct ligand–receptor combinations drive differential signalling, resulting in the modulation of various functions [21]. For example in the case of AD, targets such as Aβ or neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are recognized by toll like-receptors (TLRs) resulting in a proinflammatory cytokine storm associated with the release of cytokines or effector molecules (i.e. TNF, IL-1, NO), while recognition of cell debris or dystrophic neurites by microglial TREM2 receptors is associated with a phagocytic response along with an increase in TGFβ and IL10 signalling [23]. After initial recognition, microglial uptake of pathogenic targets may be initiated; the plasma membrane extends and encloses around the target forming a vesicular phagosome. This nascent phagosome subsequently fuses with lysosomes forming a phagolysosome. Lastly, digestion occurs within the phagolysosome where the target is degraded. Following this, byproducts must be either stored or recycled by the phagocytic cell [20]. Further, microglia respond to pathogenic targets through responsive signalling, through altered cytokine production and gene expression.

Recent evidence has highlighted a subset of microglia with a disease-associated gene signature. Disease-associated microglia (DAM), were first identified through a comprehensive single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of immune cells isolated from the 5xFAD mouse model of AD [24]. These cells express microglial markers such as Iba1, Cst3 and Hexb, but have downregulation of homeostatic markers like P2ry12, P2ry13, Cx3cr1, CD33 and Tmem119 [25]. Furthermore, they display an upregulation of Trem2, Tyrobp, Ctsd, Apoe and Lpl, which are genes involved in phagocytic and lysosomal functions of microglia, as well as lipid metabolism [9]. Subsequent studies have identified similar DAM profiles in human AD post-mortem tissue, as well as in other mouse models of neurodegeneration including APP/PS1, PS2APP, tau P301 L and P301S, ALS mouse models, MS models and ageing mouse models. Alterations in DAM gene expression are associated with differential microglial function [26–33].

2. Microglial risk factors and their functional relevance

2.1. TREM2

TREM2 is an immunoreceptor expressed on myeloid cells, including microglia. Whole-genome sequencing identified rs75932628, the TREM2 R47H variant, in 2013. This is thought to be a loss-of-function single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and increases the risk of developing AD by approximately 2- to 4-fold [34–36]. Additionally, higher levels of soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with AD carrying this SNP has been correlated with disease progression [37]. Rs143332484 (R62H) was identified in 2014 as a significant risk modifier for AD [38], but its function in AD progression is not known. There is some evidence that sTREM2 containing either SNP that causes an arginine to histidine substitution is less effective than WT sTREM2 at activating microglia and promoting survival [39]. Both SNPs are known to result in reduced stability and impaired ligand binding. Additionally, two novel transcripts apart from the canonical long-form of TREM2 have been identified in human post-mortem brains that may add to the functional relevance of TREM2 in AD [40].

Though the physiological function of TREM2 is not completely understood, reported TREM2 ligands include lipidated apolipoprotein E (APOE), an aforementioned AD-associated gene and Aβ oligomers, both of which are components of amyloid plaques [14,41–43]. TREM2 signalling pathways, specifically via TYROBP/DAP12, underscore its role in a number of microglial-related cellular functions including inhibition of proinflammatory signalling and phagocytic uptake, as well as cell proliferation and survival [44]. High-resolution microscopy has revealed that TREM2 and DAP12 are highly concentrated in processes adjacent to Aβ plaques in the AD brain, suggesting an enrichment of ‘active’ TREM2 signalling [14,45]. DAP12 is an adaptor protein that associates with TREM2, and contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) [46]. Upon ligand binding, the ITAM is phosphorylated, leading to the recruitment of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk). Subsequent downstream signalling via activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3 K) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) has been shown to result in elevation of intracellular Ca2+ through the release of IP3-gated Ca2+ stores and subsequent signalling cascade [47].

Initially, the AD-associated TREM2 mutations were assumed to result in a loss-of-function phenotype. In vitro experiments have shown that TREM2−/− microglia have impaired phagocytic capacity [48]. Several in vivo studies have shown that loss of TREM2 function or the presence of the R47H allele in amyloid-dependent AD mouse models increases plaque seeding and restricts the ability of microglia to proliferate and physically associate with plaques to form a microglia barrier [49]. This can lead to a reduction of plaque compaction leading to a diffuse plaque morphology, and a subsequent increase in neuritic dystrophy [45,47,50,51]. Interestingly, other studies using younger mice have shown that a TREM2 deficiency early on reduces Aβ pathology [51,52]. Further, a lack of TREM2 seems to worsen the phenotype of an amyloid-dependent AD mouse model but not their WT littermates, and this outcome is also based on their APOE genotype [41]. Conversely, elevated TREM2 expression in the 5xFAD mouse model has been shown to reduce the amyloid burden and improve memory performance. TREM2-overexpressing microglia also show a dampening of proinflammatory gene expression and an upregulation of many genes linked to phagocytosis, and are also seen to be more phagocytic in vitro [32,53]. TREM2-mediated phagocytosis is critical for Aβ and neuronal debris clearance in AD [43,48]. These findings consistently suggest that TREM2 signalling is important for microglial phagocytosis, proliferation and recognition and clustering around plaques, but the exact mechanism through which TREM2 affects AD pathology may be disease stage-dependent [32,37,42–44,53,54].

In addition to full-length TREM2, there is increasing evidence that sTREM2 may also be involved in microglial dynamics and response to AD pathology. sTREM2 is the soluble form of TREM2 produced by proteolytic cleavage of TREM2 by metalloproteases ADAM10/17 [37,48]. In vitro data suggest sTREM2 enhances microglial viability and helps trigger inflammatory responses by activating the Akt–GSK3β–β-catenin and NF-κB signalling pathways [54]. Levels of sTREM2 have been found to be elevated in AD, and carriers of the R47H TREM2 mutation present even higher levels of CSF sTREM2 while maintaining similar surface expression on cells. Intriguingly, a recent study found a correlation between higher CSF sTREM2 levels and an attenuation of risk of future cognitive decline in APOE4 carriers [55]. This suggests that sTREM2 may be protective and that signalling via sTREM2 may be yet another pathway through which TREM2 can influence neuroinflammation and AD pathology [37,56,57].

Taken together, this body of evidence indicates that TREM2 signalling via DAP12 is necessary for the recognition of toxic species like Aβ, initiating microglial activation in the AD brain, as well as enhancing proliferation and survival of microglia leading to a sustained microgliosis response. This, in turn, is crucial for phagocytosis of Aβ and clearance of neuronal debris. This also brings to light the fact that certain features of immune activation are indeed beneficial in the context of neurodegenerative disease, and that the response itself depends on the timeline of disease progression.

In parallel, TREM2's effect on tau-related disease progression has also been investigated. Importantly, levels of sTREM2 in the CSF of AD patients positively correlated with total tau and p-tau in the CSF [37,58]. Homozygous deletion of TREM2 in PS19 mice that overexpress the human P301S mutation has been shown to be protective against neurodegeneration, as well as prevent microglia activation, without affecting tau pathology [28,59]. On the other hand, Sayed et al. [59] showed that TREM2 haploinsufficiency in the PS19 model confers increased brain atrophy, exaggerated tau pathology, and an increase in proinflammatory markers suggesting a dose-dependent response of TREM2 in PS19 mice. Further, TREM2−/−hTau mice (a less aggressive tauopathy model) were found to display decreased microgliosis, similar to TREM2−/−;PS19 mice; however, tau pathology was worsened. These data suggest that TREM2's contribution to pathology is disease stage dependent, and that TREM2 may play multiple roles in initial disease development versus late-stage disease progression. During the initial stages of tau pathology, in the absence of neurodegeneration (i.e. hTau mice), reduced TREM2 function is suggested to promote tau pathology, whereas decreased TREM2 function in late-stage disease progression (i.e. PS19 mice) proves to be protective against neurodegeneration. Further, mice expressing the R47H mutations exhibit reduced tau pathology and neurodegeneration [60]. Studies indicate that this effect is in large part due to alterations in microglial activation, as mice showed reduced expression of DAM genes as well as phagolysosomal marker CD68. Impaired microglial phagocytosis was hypothesized to be responsible for reduced neurodegeneration, as studies have shown that microglial TREM2 is required for synapse elimination in brain development [61]; R47H microglia showed reduced engulfment of postsynaptic elements, namely the complement protein C1q [60]. Moreover, Dejanovic et al. has previously reported a large increase in complement C1q in neuronal synapses of PS19 mice and AD patients, and a rescue of tau-induced synaptic loss by C1q antibodies. Synaptic C1q was found to be associated with dysregulated microglial phagocytosis of synapses in vivo and decreased synapse density in vitro [31].

2.2. CD33

CD33 is another transmembrane immunoreceptor expressed on myeloid cells including microglia, and another top-ranked AD-associated risk gene. CD33 expression is found to be elevated in AD patients' brains, in microglial cells and in infiltrating macrophages [62,63]. It was first implicated in AD in 2008, when the minor allele (G) of rs3826656 was reported as a risk factor for LOAD [64,65]. The major allele (C) rs3865444 risk variant of CD33 was first identified in 2011 and is associated with elevated CD33 expression and reduced TREM2 expression in the brain as well as increased amyloid burden [66]. Functionally, studies show this variant to increase microglial activation and decrease Aβ phagocytosis. On the other hand, the minor allele (A) rs3865444 and rs12459419 variants yield a non-functional version of CD33 due to alternative splicing and loss of the sialic acid-binding domain, and have been described as a protective variants because they preserve the cell's ability to recognize, bind and clear Aβ [9,62,63,67–70].

CD33 (Siglec-3) is a member of the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglec) family of receptors, and recognizes sialic acid residues as its ligands, such as sialylated glycans found on pathogens [71]. CD33 harbours an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM), which is the main route for inhibitory signal transduction in cells. ITIM-immunoreceptors in microglia are involved in the modulation of various cellular functions including phagocytosis, cytokine release and apoptosis. Upon ligand binding, the ITIM of CD33 is phosphorylated and acts as a docking site for phosphatases such as SHP1/2. Subsequently, this leads to downstream dephosphorylation of other cellular proteins such as PI3 K (that are conversely activated by ITAM signalling), leading to an inhibition of cellular activity and of functions such as phagocytosis [72–74]. Importantly, the aforementioned TREM2-ITAM signalling opposes CD33-ITIM signalling, and acts downstream of CD33 signalling [74].

Research indicates that AD brains have constitutively activated CD33 signalling, with microglial cells demonstrating an upregulation of CD33 expression that correlated with plaque burden [62]. Sialic-acid bearing glycoproteins and glycolipids are found to colocalize to and adorn amyloid plaques, thereby activating CD33 signalling. This in turn encourages ITIM-associated inhibitory signalling, resulting in the ‘masking’ of plaques against microglial recognition, thereby reducing phagocytosis and clearance. Additionally, CD33 signalling inhibits the release of inflammatory cytokines and proliferation by microglia, which are part of the microglial response to AD pathology [73,75]. Unsurprisingly, CD33 ablation in amyloid models of AD enhances phagocytosis and results in reduced Aβ plaque burden [62,74]. Targeting mouse CD33 using a miRNA in the APP/PS1 amyloid model has been seen to be effective at reducing plaque burden early on (two months), but not later in the disease (eight months) [76]. RNA-seq in the CD33−/− 5xFAD mouse has revealed that genes related to phagocytosis, activation and cytokine signalling were upregulated, and that this was dependent on downstream TREM2 signalling [74]. Follow-up research is necessary to tease out the exact mechanism of interaction between CD33 and TREM2.

Independent groups have found that unlike its effects on amyloid, having higher CD33 brain expression is not associated with tau-pathology associated Braak score, and that carrying the major allele (C) rs3865444 allele seems to have no repercussions on tangle formation [77,78]. However, while little has been shown of the relationship between tau and CD33, NFTs have been shown to present sialic acid residues, suggesting a potential interaction [79].

2.3. APOE

APOE, while primarily secreted by astrocytes, is also produced by activated microglia surrounding amyloid plaques [33,80–83]. APOE polymorphic alleles (ε2, ε3, ε4) have been identified as critical genetic determinants of AD risk, with the APOE ε4 allele showing the strongest genetic risk for LOAD (and more common than FAD mutations), followed by ε3, while ε2 has displayed protective effects [84–86]. A single copy of APOE ε4 has been shown to increase the risk for developing AD 4-fold, while homozygous carriers show an approximate 12-fold increased risk for AD [84,85]. On the other hand, the rare APOE ε2 allele is protective [86]. It is still unclear whether the presence of the APOEε4 allele leads to a toxic gain of function or loss of protective function. As a secreted lipoprotein, apoE is involved in cholesterol metabolism. Moreover, it has also been identified as an amyloid-associated protein and found to be present abundantly in plaques, indicating a direct association between the two [33,80–83,87].

Studies in animal models of AD have suggested that apoE isoforms differentially impact Aβ deposition and clearance by microglia, as well as NFT formation [88,89]. As further proof of allelic contribution to AD risk, APOE alleles have been found to impact the efficacy of passive anti-Aβ immunization, suggesting that the different alleles could affect microglial phagocytic capabilities of Aβ [90]. Post-mortem analysis has indicated that both AD patients and healthy controls harbouring the APOE ε2/ε3 genotype have decreased amyloid deposition, whereas APOEε4 carriers have more abundant amyloid [91]. Additionally, increased neuroinflammatory markers were found in APOE ε4 carriers and in corresponding mouse models. Further, apoE levels are lowest in APOE ε4 mouse models, and apoE is known to contribute to anti-inflammatory signalling [92]. Additionally, APOE ε4 primary microglia secrete 3–5 times less apoE and more TNFα than APOE ε2 microglia, suggesting that the presence of APOE ε4 drives microglia to a higher inflammatory state [93].

Differences in APOE allele function may be due to a variety of biochemical and physical changes induced by amino acid alterations. ApoE ε4 has reduced lipidation compared to ApoE ε3 and ApoE ε2, and also a lower affinity for apoE receptors, one of which is TREM2. Impaired binding of Aβ-apoE and TREM2 may potentially affect both microglial recognition of amyloid pathogens and subsequent clearance of plaques [94,95]. A recent in vivo study comparing the transcriptomic response of microglial cells exposed to either e3 or e4 lipoproteins along with Aβ, showed that the addition of ε3 lipoproteins to Aβ led to a more active transcriptional response and a higher upregulation of DAM genes in comparison to e4 lipoproteins. ε4-expressing microglia also showed reduced Aβ uptake, which was further aggravated by a TREM2 deficiency in these cells. Impaired binding of allelic variation in apoE thus contributes to differences in apoE-Aβ binding; Thus, the ε4 isoform is hypothesized to negatively impact TREM2-dependent Aβ binding in microglia, which may result in impaired microglial activation and a dampened phagocytic response. Lastly, the apoE ε4 isoform also induces a slower response by microglial processes toward apoE containing Aβ, suggesting apoE's contribution to microglial activation, motility or cytoskeleton reorganization [96]. Another study has shown that genetic risk variants TREM2 R47H and APOE ε4 act by reducing the responsiveness of microglia toward amyloid, which was associated with elevated pathology [42].

Additionally, while it is clear that APOE genotype contributes greatly to amyloid deposition, APOE's effect on tau remains contested. Human studies suggest that APOE ε4 carriers, in the presence of amyloid, have higher tau burdens in vulnerable AD brain regions, as opposed to non-carriers [97]. In vivo studies point to the ε4 allele as having the most deleterious effects in tau transgenic mice, opposed to ε2 and ε3. APOE ε4 has been shown to aggravate neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in the PS19 tau transgenic mouse model, while APOE knockout is protective against neurodegeneration [98]. Further, this effect was shown to be specifically driven by microglia, as allelic differences contributed primarily to microglial activation and neurodegeneration, and complete ablation of microglia by PLX3397, an inhibitor of the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R, necessary for microglial survival) in male APOE ε4 PS19 mice completely protected these mice from neurodegeneration [89,99]. More recently, Shi et al. [100] have demonstrated a novel apoE knockout model that overexpresses the apoE metabolic receptor LDLR (low-density lipoprotein receptor, responsible for mediating clearance of apoE lipoproteins) and that reduces brain apoE when crossed to PS19 mice, which results in decreased tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Nine month-old apoE KO transgenic mice showed reduced intracellular microglial apoE, as well as reduced microglial activation and CD68 staining. Suppression of microglial activation was found to be driven by enhanced microglial cell catabolism, as sequencing experiments highlighted enrichment of lysosomal enzymes and proteins involved in cellular degradation including Lhmn, Ctss, Ctsk, Heb, Man2b1, Lamp1, Lamp2, Abca2. Further, apoE deficiency was shown to reduce microglial mTOR activation, likely due to enhanced catabolic activity. Additionally, sequencing of cultured primary microglia from LDLR transgenic mice showed significant reduction in DAM and proinflammatory gene expression as well as MHC-related gene expression, and conversely, upregulation of ion channels and neurotransmitter receptors [100].

2.4. SPI1/PU.1

SPI1, implicated in LOAD through differential network analysis, is highly expressed in immune cells, specifically microglia and macrophages. Several variants at the SPI1 locus have been identified and studies linking risk variants to gene expression indicate that variants that confer higher SPI1 expression are linked to increased risk for AD. The minor allele (G) rs1057233 lies near the SPI1 gene locus and is associated with lower expression of SPI1 in monocytes and macrophages and shows association with delayed AD onset [101]. It also influences the expression of other AD risk genes [14,102]. This SNP was previously identified in the context of systemic lupus erythematosus and was found to alter miRNA binding [103].

RNA sequencing data implicate SPI1 in the AD immune response, as increased SPI1 is associated with the upregulation of AD-associated immune and interferon-response genes. SPI1 encodes PU.1, a key transcription factor and master regulator of myeloid cell development and microglial gene expression and activation. In macrophages, PU.1 overexpression leads to increased GM-CSF and M-CSF expression (crucial factors for macrophage proliferation), as well as increased proliferation [104]. Transcriptomic analysis of reduced PU.1 gene expression in primary glial cell cultures has highlighted PU.1's contribution to innate and adaptive immune responses, specifically in the involvement of antigen presentation and phagocytosis [105]. In the BV2 mouse microglial cell line, expression of microglial genes such as Irf8, Runx1, Csf1r, Csf1, Il34, Aif1 (Iba1), Cx3cr1, Trem2 and Tyrobp, some of which already cited in this article as risk factors for AD, were found to be regulated by SPI1 [106].

Recent studies that have sought to characterize the effects of PU.1 modulation in vitro using mouse BV2 cells have reported that increased PU.1 expression leads to cells becoming more resistant to cell death and more prone to converting to an inflammatory phenotype, which could be detrimental to neighbouring cells of the brain. On the other hand, PU.1 knock-down had an opposing effect and made microglial cells more vulnerable to cell death, but also reduced inflammatory signalling. BV2 cells with reduced PU.1 expression also had increased expression of lipid metabolism genes such as ApoE, and an overall repressed homeostatic gene expression profile, which aligned to the DAM signature described earlier in this review [107]. In line with previous reports, PU.1-overexpressing cells showed increased uptake of a variety of substrates such as zymosan, myelin and apoptotic cells [9,101,105,107]. Additionally, silencing PU.1 in primary human microglia results in changes in gene expression, particularly in a network of AD-associated genes involved in immune functions, such as phagocytosis and antigen presentation [105]. Overall, these studies validate PU.1 as a positive regulator of phagocytic uptake and suggest that PU.1 overexpression primes microglial cells for an exaggerated inflammatory immune response. Further, while the aforementioned research provides promising in vitro results, further in vivo and in situ data are necessary to fully characterize the role of PU.1 in a more relevant disease model. The current hypothesis is that reduced expression of PU.1 may be beneficial due to an increased turnover and replenishment of microglial cells following apoptotic cell death in response to neuropathology, as well as turning on a more active and protective state. Further work is necessary to define the role of SPI1/PU.1 in tauopathy.

2.5. MS4A

The membrane-spanning 4-domain subfamily A (MS4A) gene cluster harbours 18 genes, of which MS4A4A, MS4A4E, MS4A6A and MS4A6E have been implicated in AD [9,69]. The main SNPs that have been identified as having an association with AD are rs670139 in MS4A4E, rs4938933 and rs1562990 within the region between MS4A4E and MS4A4A, and rs610932 in MS4A6A [68,108,109]; increased expression of MS4A6A is associated with higher amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tau tangle burden [77]. Further, binding motifs within MS4A4A and MS4A6A have been identified for transcription factor PU.1, and PU.1/SPI1 correlate closely with changes in MS4A4A and MS4A6A [77]. MS4A transmembrane proteins are found to be expressed in microglia and macrophages, as well as in peripheral immune cells. While their function in the brain is still poorly understood, they have been cited for their roles in calcium homeostasis, endocytosis and trafficking and cell signalling [110,111].

MS4A proteins are known to be involved in calcium signalling. MS4A1 is part of the Ca2+-permeable cation channel, and MS4A2 regulates mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and increases downstream calcium signalling [112,113]. Given their conserved protein structure, other members of the MS4A family may share similar functions. Alterations in calcium signalling during the early stages of AD have also been seen in human subjects and experimental mouse models [114,115].

The MS4A gene cluster has also been reported to be involved in brain immune system function. Overexpression of the MS4A gene family increases T cell activation, and also regulates apoptosis and survival of activated T cells [116,117]. Activated T cells have been found in the healthy brain as well as under neuroinflammatory conditions, and T cell activation can influence the trafficking of additional T cells across the blood--brain barrier (BBB). This in turn has been shown to increase microglial activation and production of inflammatory cytokines during AD progression [118,119].

More recently, genome-wide analysis for genetic modifiers of CSF sTREM2 has identified two SNPS in the MS4A4A gene that modify CSF sTREM2 concentrations. Rs1582763 was found to be associated with elevated CSF sTREM2 and reduced AD risk. It has previously been associated with delayed onset of AD [9,101]. On the other hand, rs6591561 was found to be associated with reduced CSF sTREM2 and increased AD risk and accelerated onset. Functional studies in human macrophage cultures provide support for a modulatory relationship between MS4A4A and sTREM2, with MS4A4A overexpression resulting in elevated sTREM2 and vice versa. MS4A4A was also found to colocalize with TREM2 in the cytoplasm of human macrophages, further validating an interaction between the two proteins [56]. Overall, these findings suggest that MS4A4A may promote TREM2 processing and subsequent microglial signalling and thus play a role in LOAD-pathogenesis. In addition, MS4A2 is known to contain an ITAM motif in its protein sequence, which may potentially lead to downstream activation signalling in microglia [120,121].

2.6. ABCA7

GWAS have identified the ATP-binding cassette transporter A7 (ABCA7) as a risk gene for LOAD. Both common and rare risk variants in ABCA7, including intronic, VNTR and PTC mutations have been found to be enriched in AD patients, with loss-of-function variants increasing disease risk [121,122]. Both genetic and epigenetic ABCA7 markers show significant correlation with AD endophenotypes including amyloid deposition, brain atrophy and cognitive decline [68,122,123].

ABCA7 is part of an ABC transporter superfamily and is involved in lipid metabolism, specifically in the transfer of phospholipids to apolipoproteins (i.e. APOE and APOJ/CLU) and in the transport of lipids across membranes [106,124–126]. ABCA7 knockout mice display altered brain phospholipid profiles. Moreover, genome-wide analysis of genetically modified ABCA7 mouse models has identified an enrichment of cellular membrane homeostasis pathways [122]. Altered lipid metabolism is likely to affect endolysosomal pathways through functions such as vesicle trafficking and is likely to affect phagocytic and degradative capabilities.

The highest expression of ABCA7 in the brain has been found in microglia. Recent research has brought to light ABCA7's involvement in microglial phagocytosis [127], since ABC transporters show high homology to ced-7, the cell corpse engulfment gene in Caenorhabditis elegans known to phagocytose apoptotic cells [128]. Studies show that ABCA7−/− peritoneal macrophages and immune cells in ABCA7 knockout mice have diminished phagocytic capabilities [129]. ABCA7 deletion in AD mouse models has shown increased amyloid deposition and decreased phagocytic uptake of oligomeric Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in both macrophages and microglia, without changing microglial activation status [122,130]. Further, increased levels of ABCA7 promote microglial phagocytosis and clearance of Aβ, presumably through the C1q complement pathway [106,107,122,124,130]. Interestingly, the involvement of ABCA7 in microglial phagocytosis is thought to affect Aβ aggregates rather than soluble Aβ, as evidenced by microdialysis studies [122].

Aikawa et al.'s research further implicates ABCA7 in the microglial immune response to AD pathogenesis. ABCA7 haplodeficiency in mice was shown to be associated with increased Aβ and CD14 accumulation in microglial cells within enlarged lysosomes. This dysregulation of CD14 trafficking potentially leads to a reduced activation of the NF-kB pathway, without affecting the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and DAM markers [131] (figure 2).

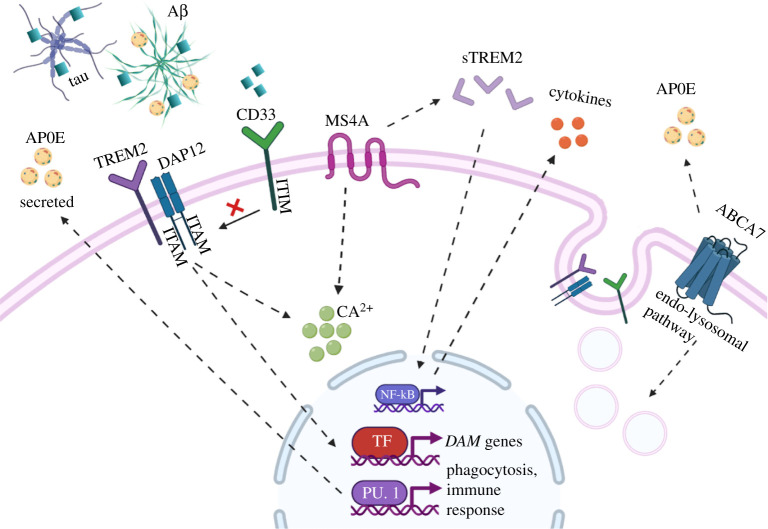

Figure 2.

Putative functions of LOAD-associated genes in microglial cells. Microglial response to pathogenic targets such as Aβ and tau begins with initial recognition via receptors such as TREM2. TREM2 signals through DAP12 to affect intracellular calcium signalling and DAM gene expression, which leads to functional outputs such as inflammatory signalling and phagocytic uptake of targets. CD33 detects sialylated targets (blue squares) and is an inhibitor of phagocytosis and opposes TREM2 signalling. sTREM2 is cleaved from full-length TREM2 and is also involved in NF-kB signalling and inflammatory response. MS4A is a transmembrane protein that is known to influence calcium signalling and modulate TREM2 processing into sTREM2. ABCA7 is a transporter protein and there is evidence that it affects the endolysosomal function and metabolism of lipids, which can affect APOE. APOE is involved in cholesterol metabolism and is found to associate with Aβ plaques, affecting their interaction with TREM2. (Created with BioRender.com.)

2.7. Additional microglial-related LOAD genes

Additionally, several other genes identified by GWAS have been reviewed for their immune-related roles in AD, including CR1, ApoJ/Clu and PLCG2, yet more studies are still necessary to identify specific functional contributions. Briefly, complement receptor 1 (CR1) expressed in glial cell populations, has been identified through GWAS as a risk factor for AD; complement factors are highly reviewed for their immune-related contribution to AD. Moreover, microglial expression of complement proteins and receptors has been shown to play a critical role in dystrophic neurite and pathogen recognition and clearance [132]. CR1 acts as the key receptor for complement protein C3B, and studies show Aβ42 binding of C3b, ultimately bridging Aβ to CR1 and phagocytes. Inhibition of CR1 reduces microglial phagocytosis of Aβ and studies link AD-related mutations in CR1 to decreased Aβ clearance in CSF [133]. Apolipoprotein J (apoJ, also known as clusterin/Clu) is also a risk variant in AD [108]. Studies show upregulation of apoJ to be associated with amyloid plaques, NFT-positive dystrophic neurites and surrounding activated microglia in the AD brain [43]. Apolipoproteins have been associated with Aβ fibrillization and opsonization-related clearance; apoJ has been reported to bind soluble Aβ and Aβ aggregates [134,135]. Researchers have found that microglia may engulf Aβ more efficiently in the presence of lipoproteins including LDL and apoJ, and that the uptake of lipoprotein–Aβ complexes by microglia is TREM2-dependent. ApoJ is a reported ligand of TREM2, and TREM2−/− microglia show reduced internalization of apoJ [43,136]. Moreover, in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that exogenous apoJ activates microglia [137]. Additionally, PLCG2, a member of the phospholipase Cy family, is highly expressed in microglial cells. Identification of a PLCG2 rare variant, P522R, is associated with decreased risk of AD; this polymorphism results in an increase in PLCy2 enzyme activity [138]. Expression of PLCG2 is increased in microglia surrounding amyloid plaques [139]. Further, PLCG2 is also known to colocalize with TREM2, and is assumed to be involved in TREM2 downstream signalling [139,140].

Further, GWAS has identified other genes such as SORL1 for potential roles in microglial phagocytosis, while other genes such as GRN and PICALM are implicated in endolysosomal regulation and pathogen degradation. Functional studies are still necessary to piece apart the exact roles of these genes in microglial-related pathways [10,13]. Moving forward, in order to understand the contribution of novel immune gene variants in LOAD, more relevant models of disease must be assessed [141]. Currently, the majority of AD mouse models focus on the expression of rare familial amyloid-related mutations in APP and Presenilin, or of tau-related gene overexpression [142]. However, newly identified rare and common risk variants in LOAD require novel mouse models for further investigation [16,83,143].

3. Conclusion

As outlined in this review, genetic studies (i.e. GWAS, expression network analyses) of AD pathogenesis have underscored the significance of microglia in LOAD development and progression. Research has shown that identified gene variants in microglia have roles in a variety of microglial functions, including but not limited to pathogen identification, phagocytosis, phagolysosomal digestion and immune signalling. Moreover, work in human and AD mouse models has shown that these genes (i.e. Trem2) can play conflicting roles, protective or detrimental, depending on the stage of disease development and progression, making it critical to understand the specific time-dependent roles in effects of risk variants in AD [144]. Functional genomics as well as the identification of coding gene variants thus provide a framework of support for the hypothesis that microglia play a causative role in AD development, rather than a purely responsive reaction triggered by AD pathology.

Furthermore, the majority of research on AD therapeutics has been geared towards targeting AD hallmarks (i.e. amyloid and tau); however, emerging data have unveiled novel pathways in immune cell function, ultimately helping shed light on alternative routes for therapeutic intervention. Preliminary research has helped to unpack some of the functions associated with AD risk genes. However, continued exploration is necessary to better comprehend the full functional spectrum of disease variants in microglia, for the purpose of identifying novel and effective targets for AD therapy.

Acknowledgement

Authors also acknowledge the MSK Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (grant no. P30 CA008748), Mr William H. Goodwin and Mrs Alice Goodwin and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, the Experimental Therapeutics Center of MSKCC and the William Randolph Hearst Fund in Experimental Therapeutics.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional information.

Authors' contributions

L.A.J.: Conceptualization, investigation, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; T.J.: conceptualization, investigation, project administration, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; Y.-M.L.: conceptualization, project administration, resources, writing—review and editing.

Competing interests

Y.-M.L. is co-inventor of intellectual property (assay for gamma-secretase activity and screening method for gamma-secretase inhibitors) owned by MSKCC and licensed to Jiangsu Continental Medical Development.

Funding

This work is supported by NIH grant nos. R01NS096275 (Y.-M.L.), RF1AG057593 (Y.-M.L.), R01AG061350 (Y.-M.L.), the JPB Foundation (Y.-M.L.), the MetLife Foundation (Y.-M.L.), Cure Alzheimer's Fund (Y.-M.L.). The Edward and Della L. Thome Memorial Foundation (Y.-M.L.) and Coins for the Alzheimer's Research Trust (Y.-M.L.).

References

- 1.James BD, Leurgans SE, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Yaffe K, Bennett DA. 2014. Contribution of Alzheimer disease to mortality in the United States. Neurology 82, 1045-1050. ( 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000240) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Strooper B, Karran E. 2016. The cellular phase of Alzheimer's disease. Cell 164, 603-615. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.056) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubois B, et al. 2016. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement. 12, 292. ( 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayeux R. 2003. Epidemiology of neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26, 81-104. ( 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.043002.094919) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekris LM, Yu CE, Bird TD, Tsuang DW. 2010. Genetics of Alzheimer disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 23, 213-227. ( 10.1177/0891988710383571) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Teri L, Schellenberg GD, van Belle G, Jolley L, Larson EB. 2002. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch. Neurol. 59, 1737-1746. ( 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1737) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campion D, et al. 1999. Early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation spectrum. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 65, 664-670. ( 10.1086/302553) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Fratiglioni L, Johansson B, Mortimer JA, Berg S, Fiske A, Pedersen NL. 2006. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 168-174. ( 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.168) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambert JC, et al. 2013. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Genet. 45, 1452-1458. ( 10.1038/ng.2802) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karch CM, Goate AM. 2015. Alzheimer's disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol. Psychiatry 77, 43-51. ( 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frost GR, Li YM. 2017. The role of astrocytes in amyloid production and Alzheimer's disease. Open Biol. 7, 170228. ( 10.1098/rsob.170228) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heneka MT, et al. 2015. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 14, 388. ( 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efthymiou AG, Goate AM. 2017. Late onset Alzheimer's disease genetics implicates microglial pathways in disease risk. Mol. Neurodegener. 12, 1-12. ( 10.1186/s13024-017-0184-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sims R, et al. 2017. Rare coding variants in PLCG2, ABI3, and TREM2 implicate microglial-mediated innate immunity in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Genet. 49, 1373-1384. ( 10.1038/ng.3916) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunkle BW, et al. 2019. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer's disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat. Genet. 51, 414-430. ( 10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandey RS, Graham L, Uyar A, Preuss C, Howell GR, Carter GW. 2019. Genetic perturbations of disease risk genes in mice capture transcriptomic signatures of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 50. ( 10.1186/s13024-019-0351-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long JM, Holtzman DM. 2019. Alzheimer disease: an update on pathobiology and treatment strategies. Cell 179, 312-339. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McQuade A, Blurton-Jones M. 2019. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease: exploring how genetics and phenotype influence risk. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 1805-1817. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.01.045) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Der Lee DI, et al. 2019. Mutated nucleophosmin 1 as immunotherapy target in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 774-785. ( 10.1172/JCI97482) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flannagan RS, Jaumouillé V, Grinstein S. 2012. The cell biology of phagocytosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 7, 61-98. ( 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132445) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arcuri C, Mecca C, Bianchi R, Giambanco I, Donato R. 2017. The pathophysiological role of microglia in dynamic surveillance, phagocytosis and structural remodeling of the developing CNS. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10, 1-22. ( 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00191) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Márquez-Ropero M, Benito E, Plaza-Zabala A, Sierra A. 2020. Microglial corpse clearance: lessons from macrophages. Front. Immunol. 11, 506. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00506) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neumann H, Takahashi K. 2007. Essential role of the microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 (TREM2) for central nervous tissue immune homeostasis. J. Neuroimmunol. 184, 92-99. ( 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deczkowska A, Keren-Shaul H, Weiner A, Colonna M, Schwartz M, Amit I. 2018. Disease-associated microglia: a universal immune sensor of neurodegeneration. Cell 173, 1073-1081. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butovsky O, et al. 2014. Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 131-143. ( 10.1038/nn.3599) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiu IM, et al. 2013. A neurodegeneration-specific gene-expression signature of acutely isolated microglia from an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Cell Rep. 4, 385-401. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holtman IR, et al. 2015. Induction of a common microglia gene expression signature by aging and neurodegenerative conditions: a co-expression meta-analysis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 3, 1-8. ( 10.1186/s40478-015-0203-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leyns CEG, et al. 2017. TREM2 deficiency attenuates neuroinflammation and protects against neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11 524-11 529. ( 10.1073/pnas.1710311114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ofengeim D, et al. 2017. RIPK1 mediates a disease-associated microglial response in Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E8788-E8797. ( 10.1073/pnas.1714175114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajami B, et al. 2018. Single-cell mass cytometry reveals distinct populations of brain myeloid cells in mouse neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration models. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 541-551. ( 10.1038/s41593-018-0100-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dejanovic B, et al. 2018. Changes in the synaptic proteome in tauopathy and rescue of tau-induced synapse loss by C1q antibodies. Neuron 100, 1322-1336. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiller KJ, et al. 2018. Microglia-mediated recovery from ALS-relevant motor neuron degeneration in a mouse model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 329-340. ( 10.1038/s41593-018-0083-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olah M, et al. 2018. A transcriptomic atlas of aged human microglia. Nat. Commun. 9, 1-8. ( 10.1038/s41467-018-02926-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guerreiro R, et al. 2013. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 117-127. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jonsson T, et al. 2013. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 107-116. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sierra A, Abiega O, Shahraz A, Neumann H. 2013. Janus-faced microglia: beneficial and detrimental consequences of microglial phagocytosis. Front. Cell Neurosci. 7, 1-22. ( 10.3389/fncel.2013.00006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suárez-Calvet M, et al. 2019. Early increase of CSF sTREM2 in Alzheimer's disease is associated with tau related-neurodegeneration but not with amyloid-β pathology. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 1-14. ( 10.1186/s13024-018-0301-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang T, et al. 2014. Upregulation of TREM2 ameliorates neuropathology and rescues spatial cognitive impairment in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 2949-2962. ( 10.1038/npp.2014.164) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhong L, et al. 2017. Soluble TREM2 induces inflammatory responses and enhances microglial survival. J. Exp. Med. 214, 597-607. ( 10.1084/jem.20160844) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Del-Aguila JL, et al. 2019. TREM2 brain transcript-specific studies in AD and TREM2 mutation carriers. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 1-13. ( 10.1186/s13024-019-0319-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fitz NF, Wolfe CM, Playso BE, Biedrzycki RJ, Lu Y, Nam KN, Lefterov I, Koldamova R. 2020. Trem2 deficiency differentially affects phenotype and transcriptome of human APOE3 and APOE4 mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 1-21. ( 10.1186/s13024-019-0350-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen AT, et al. 2020. APOE and TREM2 regulate amyloid-responsive microglia in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 140, 477-493. ( 10.1007/s00401-020-02200-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeh FL, Wang Y, Tom I, Gonzalez LC, Sheng M. 2016. TREM2 binds to apolipoproteins, including APOE and CLU/APOJ, and thereby facilitates uptake of amyloid-beta by microglia. Neuron 91, 328-340. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colonna M. 2003. Trems in the immune system and beyond. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 445-453. ( 10.1038/nri1106) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan P, et al. 2016. TREM2 haplodeficiency in mice and humans impairs the microglia barrier function leading to decreased amyloid compaction and severe axonal dystrophy. Neuron 90, 724-739. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.05.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lanier LL, Corliss BC, Wu J, Leong C, Phillips JH. 2007. Immunoreceptor DAP12 bearing a tyrosine-based activation motif is involved in activating NK cells. Nature 391, 3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colonna M, Wang Y. 2016. TREM2 variants: new keys to decipher Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 201-207. ( 10.1038/nrn.2016.7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleinberger G, et al. 2014. TREM2 mutations implicated in neurodegeneration impair cell surface transport and phagocytosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 243ra86. ( 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009093) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng-Hathaway PJ, et al. 2018. The Trem2 R47H variant confers loss-of-function-like phenotypes in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 1-12. ( 10.1186/s13024-017-0233-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ulrich JD, et al. 2014. Altered microglial response to Aβ plaques in APPPS1-21 mice heterozygous for TREM2. Mol. Neurodegener. 9, 1-9. ( 10.1186/1750-1326-9-20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jay TR, Hirsch AM, Broihier ML, Miller CM, Neilson LE, Ransohoff RM, Lamb BT, Landreth GE. 2017. Disease progression-dependent effects of TREM2 deficiency in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 37, 637-647. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2110-16.2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jay TR, et al. 2015. TREM2 deficiency eliminates TREM2+ inflammatory macrophages and ameliorates pathology in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. J. Exp. Med. 212, 287-295. ( 10.1084/jem.20142322) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang T, Yu JT, Hu N, Tan MS, Zhu XC, Tan L. 2014. CD33 in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 49, 529-535. ( 10.1007/s12035-013-8536-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhong L, et al. 2018. Amyloid-beta modulates microglial responses by binding to the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2). Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 1-12. ( 10.1186/s13024-018-0247-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franzmeier N, et al. 2020. Higher CSF sTREM2 attenuates ApoE4- related risk for cognitive decline and neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 2, 1-10. ( 10.1186/s13024-020-00407-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piccio L, et al. 2016. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 is higher in Alzheimer disease and associated with mutation status. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 925-933. ( 10.1007/s00401-016-1533-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piccio L, et al. 2008. Identification of soluble TREM-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid and its association with multiple sclerosis and CNS inflammation. Brain 131, 3081-3091. ( 10.1093/brain/awn217) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halaas NB, et al. 2020. CSF sTREM2 and tau work together in predicting increased temporal lobe atrophy in older adults. Cereb Cortex 30, 2295-2306. ( 10.1093/cercor/bhz240) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sayed FA, et al. 2018. Differential effects of partial and complete loss of TREM2 on microglial injury response and tauopathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10 172-10 177. ( 10.1073/pnas.1811411115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gratuze M, et al. 2020. Impact of TREM2R47H variant on tau pathology-induced gliosis and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 4954-4968. ( 10.1172/JCI138179) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Filipello F, et al. 2018. The microglial innate immune receptor TREM2 is required for synapse elimination and normal brain connectivity. Immunity 48, 979-991. ( 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Griciuc A, et al. 2013. Alzheimer's disease risk gene cd33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid beta. Neuron 78, 631-643. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Malik M, Simpson JF, Parikh I, Wilfred BR, Fardo DW, Nelson PT, Estus S. 2013. CD33 Alzheimer's risk-altering polymorphism, CD33 expression, and exon 2 splicing. J. Neurosci. 33, 13 320-13 325. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1224-13.2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bertram L, Tanzi RE. 2008. Thirty years of Alzheimer's disease genetics: the implications of systematic meta-analyses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 768-778. ( 10.1038/nrn2494) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bertram L, et al. 2008. Genome-wide association analysis reveals putative Alzheimer's disease susceptibility loci in addition to APOE. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 623-632. ( 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chan G, et al. 2015. CD33 modulates TREM2: convergence of Alzheimer loci. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1556-1558. ( 10.1038/nn.4126) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carrasquillo MM, et al. 2011. Replication of EPHA1 and CD33 associations with late-onset Alzheimer's disease: a multi-centre case-control study. Mol. Neurodegener. 6, 1-9. ( 10.1186/1750-1326-6-54) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hollingworth P, et al. 2011. Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Genet. 43, 429-435. ( 10.1038/ng.803) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Naj AC, et al. 2011. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Genet. 43, 436-441. ( 10.1038/ng.801) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.dos Santos LR, et al. 2017. Validating GWAS variants from microglial genes implicated in Alzheimer's disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 62, 215-221. ( 10.1007/s12031-017-0928-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Freeman SD, Kelm S, Barber EK, Crocker PR. 1995. Characterization of CD33 as a new member of the sialoadhesin family of cellular interaction molecules. Blood 85, 2005-2012. ( 10.1182/blood.V85.8.2005.bloodjournal8582005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lajaunias F, Dayer J-M, Chizzolini C. 2005. Constitutive repressor activity of CD33 on human monocytes requires sialic acid recognition and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mediated intracellular signaling. Eur. J. Immunol. 35, 243-251. ( 10.1002/eji.200425273) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crocker PR, McMillan SJ, Richards HE. 2012. CD33-related siglecs as potential modulators of inflammatory responses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1253, 102-111. ( 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06449.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Griciuc A, et al. 2019. TREM2 acts downstream of CD33 in modulating microglial pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 103, 820-835. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.06.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tateno H, Li H, Schur MJ, Bovin N, Crocker PR, Wakarchuk WW, Paulson JC. 2007. Distinct endocytic mechanisms of CD22 (Siglec-2) and Siglec-F reflect roles in cell signaling and innate immunity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 5699-5710. ( 10.1128/MCB.00383-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Griciuc A, et al. 2020. Gene therapy for Alzheimer's disease targeting CD33 reduces amyloid beta accumulation and neuroinflammation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 29, 2920-2935. ( 10.1093/hmg/ddaa179) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karch CM, Jeng AT, Nowotny P, Cady J, Cruchaga C, Goate AM. 2012. Expression of novel Alzheimer's disease risk genes in control and Alzheimer's disease brains. PLoS ONE 7, e50976. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0050976) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bradshaw EM, et al. 2013. CD33 Alzheimer's disease locus: altered monocyte function and amyloid biology. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 848-850. ( 10.1038/nn.3435) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nagamine S, Yamazaki T, Makioka K, Fujita Y, Ikeda M, Takatama M, Okamoto K, Yokoo H, Ikeda Y. 2016. Hypersialylation is a common feature of neurofibrillary tangles and granulovacuolar degenerations in Alzheimer's disease and tauopathy brains. Neuropathology 36, 333-345. ( 10.1111/neup.12277) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rangaraju S, et al. 2018. Quantitative proteomics of acutely-isolated mouse microglia identifies novel immune Alzheimer's disease-related proteins. Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rangaraju S, et al. 2018. Identification and therapeutic modulation of a pro-inflammatory subset of disease-associated-microglia in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 24. ( 10.1186/s13024-018-0254-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fernandez CG, Hamby ME, McReynolds ML, Ray WJ. 2019. The role of APOE4 in disrupting the homeostatic functions of astrocytes and microglia in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 14. ( 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huynh T-P V, et al. 2019. Lack of hepatic apoE does not influence early Aβ deposition: observations from a new APOE knock-in model. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 37. ( 10.1186/s13024-019-0337-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ward A, Crean S, Mercaldi CJ, Collins JM, Boyd D, Cook MN, Arrighi HM. 2012. Prevalence of apolipoprotein E4 genotype and homozygotes (APOE e4/4) among patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 38, 1-17. ( 10.1159/000334607) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Najm R, Jones EA, Huang Y. 2019. Apolipoprotein E4, inhibitory network dysfunction, and Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 1-13. ( 10.1186/s13024-019-0324-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. 1993. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science 261, 921-923. ( 10.1126/science.8346443) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Safieh M, Korczyn AD, Michaelson DM. 2019. ApoE4: an emerging therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease. BMC Med. 17, 1-17. ( 10.1186/s12916-019-1299-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. 2009. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 63, 287-303. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shi Y, Manis M, Long J, Wang K, Sullivan PM, Remolina Serrano J, Hoyle R, Holtzman DM. 2019. Microglia drive APOE-dependent neurodegeneration in a tauopathy mouse model. J. Exp. Med. 216, 2546-2561. ( 10.1084/jem.20190980) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pankiewicz JE, Baquero-Buitrago J, Sanchez S, Lopez-Contreras J, Kim J, Sullivan PM, Holtzman DM, Sadowski MJ. 2017. APOE genotype differentially modulates effects of anti-Aβ, passive immunization in APP transgenic mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 12, 12. ( 10.1186/s13024-017-0156-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Z, Shue F, Zhao N, Shinohara M, Bu G. 2020. APOE2: protective mechanism and therapeutic implications for Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 63. ( 10.1186/s13024-020-00413-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vitek MP, Brown CM, Colton CA. 2009. APOE genotype-specific differences in the innate immune response. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1350-1360. ( 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lanfranco MF, Sepulveda J, Kopetsky G, Rebeck GW. 2021. Expression and secretion of apoE isoforms in astrocytes and microglia during inflammation. Glia 69, 1478-1493. ( 10.1002/glia.23974) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ruiz J, et al. 2005. The apoE isoform binding properties of the VLDL receptor reveal marked differences from LRP and the LDL receptor. J. Lipid Res. 46, 1721-1731. ( 10.1194/jlr.M500114-JLR200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G. 2012. Apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein E receptors: normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fitz NF, et al. 2021. Phospholipids of APOE lipoproteins activate microglia in an isoform-specific manner in preclinical models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Commun. 12, 1-18. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-20314-w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Weigand AJ, Thomas KR, Bangen KJ, Eglit GML, Delano-Wood L, Gilbert PE, Brickman AM, Bondi MW. 2021. APOE interacts with tau PET to influence memory independently of amyloid PET in older adults without dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 17, 61-69. ( 10.1002/alz.12173) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shi Y, et al. 2017. ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature 549, 523-527. ( 10.1038/nature24016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mancuso R, et al. 2019. Stem-cell-derived human microglia transplanted in mouse brain to study human disease. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 2111-2116. ( 10.1038/s41593-019-0525-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shi Y, et al. 2021. Overexpressing low-density lipoprotein receptor reduces tau-associated neurodegeneration in relation to apoE-linked mechanisms. Neuron 106, 2413-2426. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.05.034) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huang K-L, et al. 2017. A common haplotype lowers PU.1 expression in myeloid cells and delays onset of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1052-1061. ( 10.1038/nn.4587) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tansey KE, Cameron D, Hill MJ. 2018. Genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease is concentrated in specific macrophage and microglial transcriptional networks. Genome Med. 10, 1-10. ( 10.1186/s13073-018-0523-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hikami K, et al. 2011. Association of a functional polymorphism in the 3’-untranslated region of SPI1 with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 63, 755-763. ( 10.1002/art.30188) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Celada A, Borràs FE, Soler C, Lloberas J, Klemsz M, van Beveren C, McKercher S, Maki RA. 2021. The transcription factor PU.1 is involved in macrophage proliferation. J. Exp. Med. 184, 61-69. ( 10.1084/jem.184.1.61) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rustenhoven J, et al. 2018. PU.1 regulates Alzheimer's disease-associated genes in primary human microglia. Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 1-16. ( 10.1186/s13024-018-0277-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Satoh J-I, Asahina N, Kitano S, Kino Y. 2014. A comprehensive profile of ChIP-Seq-based PU.1/Spi1 target genes in microglia. Gene Regul. Syst. Biol. 8, 127-139. ( 10.4137/GRSB.S19711) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pimenova AA, Herbinet M, Gupta I, Machlovi SI, Bowles KR, Marcora E, Goate AM. et al. 2021. Alzheimer's-associated PU.1 expression levels regulate microglial inflammatory response. Neurobiol. Dis. 148,105217. ( 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105217) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Harold D, et al. 2009. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Genet. 41, 1088-1093. ( 10.1038/ng.440) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Antúnez C, et al. 2011. The membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A (MS4A) gene cluster contains a common variant associated with Alzheimer's disease. Genome Med. 3, 33. ( 10.1186/gm249) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zuccolo J, et al. 2013. Expression of MS4A and TMEM176 genes in human B lymphocytes. Front. Immunol. 4, 195. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00195) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cruse G, Beaven MA, Music SC, Bradding P, Gilfillan AM, Metcalfe DD. 2015. The CD20 homologue MS4A4 directs trafficking of KIT toward clathrin-independent endocytosis pathways and thus regulates receptor signaling and recycling. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 1711-1727. ( 10.1091/mbc.E14-07-1221) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Polyak MJ, Li H, Shariat N, Deans JP. 2008. CD20 homo-oligomers physically associate with the B cell antigen receptor: dissociation upon receptor engagement and recruitment of phosphoproteins and calmodulin-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18 545-18 552. ( 10.1074/jbc.M800784200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ma J, Yu JT, Tan L. 2015. MS4A cluster in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 51, 1240-1248. ( 10.1007/s12035-014-8800-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Etcheberrigaray R, Hirashima N, Nee L, Prince J, Govoni S, Racchi M, Tanzi RE, Alkon DL. 1998. Calcium responses in fibroblasts from asymptomatic members of Alzheimer's disease families. Neurobiol. Dis. 5, 37-45. ( 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0176) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.LaFerla FM. 2002. Calcium dyshomeostasis and intracellular signalling in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 862-872. ( 10.1038/nrn960) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Xu H, Yan Y, Williams MS, Carey GB, Yang J, Li H, Zhang GX, Rostami A. 2010. MS4a4B, a CD20 Homologue in T cells, inhibits T cell propagation by modulation of cell cycle. PLoS ONE 5, 1-12. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0013780) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yan Y, Li Z, Zhang GX, Williams MS, Carey GB, Zhang J, Rostami A, Xu H. 2013. Anti-MS4a4B treatment abrogates MS4a4B-mediated protection in T cells and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Apoptosis 18, 1106-1119. ( 10.1007/s10495-013-0870-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Howie D, et al. 2009. MS4A4B is a GITR-associated membrane adapter, expressed by regulatory T cells, which modulates T cell activation. J. Immunol. 183, 4197-4204. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.0901070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Walsh JT, Zheng J, Smirnov I, Lorenz U, Tung K, Kipnis J. 2014. Regulatory T cells in central nervous system injury: a double-edged sword. J. Immunol. 193, 5013-5022. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.1302401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Eon Kuek L, Leffler M, Mackay GA, Hulett MD. 2016. The MS4A family: counting past 1, 2 and 3. Immunol. Cell Biol. 94, 11-23. ( 10.1038/icb.2015.48) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Deming Y, et al. 2019. The MS4A gene cluster is a key modulator of soluble TREM2 and Alzheimer's disease risk. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, 1-19. ( 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau2291) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sakae N, et al. 2016. ABCA7 deficiency accelerates amyloid-β generation and Alzheimer's neuronal pathology. J. Neurosci. 36, 3848-3859. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3757-15.2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.De Roeck A, Van Broeckhoven C, Sleegers K. 2019. The role of ABCA7 in Alzheimer's disease: evidence from genomics, transcriptomics and methylomics. Acta Neuropathol. 138, 201-220. ( 10.1007/s00401-019-01994-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Jehle AW, et al. 2006. ATP-binding cassette transporter A7 enhances phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and associated ERK signaling in macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 174, 547-556. ( 10.1083/jcb.200601030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hayashi M, Abe-Dohmae S, Okazaki M, Ueda K, Yokoyama S. 2005. Heterogeneity of high density lipoprotein generated by ABCA1 and ABCA7. J. Lipid Res. 46, 1703-1711. ( 10.1194/jlr.M500092-JLR200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kim B, Backus C, Oh S, Hayes JM, Feldman EL. 2009. Increased tau phosphorylation and cleavage in mouse models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Endocrinology 150, 5294-5301. ( 10.1210/en.2009-0695) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li H, Karl T, Garner B. 2015. Understanding the function of ABCA7 in Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43, 920-923. ( 10.1042/BST20150105) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wu YC, Horvitz HR. 1998. The C. elegans cell corpse engulfment gene ced-7 encodes a protein similar to ABC transporters. Cell 93, 951-960. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81201-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tanaka N, Abe-Dohmae S, Iwamoto N, Yokoyama S. 2011. Roles of ATP-binding cassette transporter A7 in cholesterol homeostasis and host defense system. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 18, 274-281. ( 10.5551/jat.6726) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kim WS, Li H, Ruberu K, Chan S, Elliott DA, Low JK, Cheng D, Karl T, Garner B. 2013. Deletion of Abca7 increases cerebral amyloid-β accumulation in the J20 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 33, 4387-4394. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4165-12.2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Aikawa T, et al. 2019. ABCA7 haplodeficiency disturbs microglial immune responses in the mouse brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 23 790-23 796. ( 10.1073/pnas.1908529116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Schafer DP, et al. 2012. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron 74, 691-705. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Brouwers N, et al. 2012. Alzheimer risk associated with a copy number variation in the complement receptor 1 increasing C3b/C4b binding sites. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 223-233. ( 10.1038/mp.2011.24) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Martin-Rehrmann MD, Hoe H-S, Capuani EM, Rebeck GW. 2005. Association of apolipoprotein J-positive β-amyloid plaques with dystrophic neurites in Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurotox. Res. 7, 231-241. ( 10.1007/BF03036452) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Koudinov AR, Berezov TT, Kumar A, Koudinova NV. 1998. Alzheimer's amyloid beta interaction with normal human plasma high density lipoprotein: association with apolipoprotein and lipids. Clin. Chim. Acta 270, 75-84. ( 10.1016/S0009-8981(97)00207-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.De Retana SF, et al. 2019. Peripheral administration of human recombinant ApoJ/clusterin modulates brain beta-amyloid levels in APP23 mice. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 11, 42. ( 10.1186/s13195-019-0498-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xie Z, Harris-White ME, Wals PA, Frautschy SA, Finch CE, Morgan TE. 2005. Apolipoprotein J (clusterin) activates rodent microglia in vivo and in vitro. J. Neurochem. 93, 1038-1046. ( 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03065.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Takalo M, et al. 2020. The Alzheimer's disease-associated protective Plcγ2-P522R variant promotes immune functions. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 52. ( 10.1186/s13024-020-00402-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Magno L, et al. 2019. Alzheimer's disease phospholipase C-gamma-2 (PLCG2) protective variant is a functional hypermorph. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 11, 1-11. ( 10.1186/s13195-019-0469-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Magno L, Bunney TD, Mead E, Svensson F, Bictash MN. 2021. TREM2/PLCγ2 signalling in immune cells: function, structural insight, and potential therapeutic modulation. Mol. Neurodegener. 16, 22. ( 10.1186/s13024-021-00436-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Preuss C, et al. 2020. A novel systems biology approach to evaluate mouse models of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 15, 67. ( 10.1186/s13024-020-00412-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gallardo G, Wong CH, Ricardez SM, Mann CN, Lin KH, Leyns CEG, Jiang H, Holtzman DM. 2019. Targeting tauopathy with engineered tau-degrading intrabodies. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 1-12. ( 10.1186/s13024-019-0340-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Green C, Sydow A, Vogel S, Anglada-Huguet M, Wiedermann D, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM, Hoehn M. 2019. Functional networks are impaired by elevated tau-protein but reversible in a regulatable Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 13. ( 10.1186/s13024-019-0316-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Frost GR, Jonas LA, Friend LY-M. 2019. Friend, foe or both? Immune activity in Alzheimer's disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 337. ( 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00337) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional information.