Summary

Background

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) encodes 37 genes necessary for synthesizing 13 essential subunits of the oxidative phosphorylation system. mtDNA alterations are known to cause mitochondrial disease (MitD), a clinically heterogeneous group of disorders that often present with neuropsychiatric symptoms. Understanding the nature and frequency of mtDNA alterations in health and disease could be a cornerstone in disentangling the relationship between biochemical findings and clinical symptoms of brain disorders. This systematic review aimed to summarize the mtDNA alterations in human brain tissue reported to date that have implications for further research on the pathophysiological significance of mtDNA alterations in brain functioning.

Methods

We searched the PubMed and Embase databases using distinct terms related to postmortem human brain and mtDNA up to June 10, 2021. Reports were eligible if they were empirical studies analysing mtDNA in postmortem human brains.

Findings

A total of 158 of 637 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were clustered into the following groups: MitD (48 entries), neurological diseases (NeuD, 55 entries), psychiatric diseases (PsyD, 15 entries), a miscellaneous group with controls and other clinical diseases (5 entries), ageing (20 entries), and technical issues (5 entries). Ten entries were ascribed to more than one group. Pathogenic single nucleotide variants (pSNVs), both homo- or heteroplasmic variants, have been widely reported in MitD, with heteroplasmy levels varying among brain regions; however, pSNVs are rarer in NeuD, PsyD and ageing. A lower mtDNA copy number (CN) in disease was described in most, but not all, of the identified studies. mtDNA deletions were identified in individuals in the four clinical categories and ageing. Notably, brain samples showed significantly more mtDNA deletions and at higher heteroplasmy percentages than blood samples, and several of the deletions present in the brain were not detected in the blood. Finally, mtDNA heteroplasmy, mtDNA CN and the deletion levels varied depending on the brain region studied.

Interpretation

mtDNA alterations are well known to affect human tissues, including the brain. In general, we found that studies of MitD, NeuD, PsyD, and ageing were highly variable in terms of the type of disease or ageing process investigated, number of screened individuals, studied brain regions and technology used. In NeuD and PsyD, no particular type of mtDNA alteration could be unequivocally assigned to any specific disease or diagnostic group. However, the presence of mtDNA deletions and mtDNA CN variation imply a role for mtDNA in NeuD and PsyD. Heteroplasmy levels and threshold effects, affected brain regions, and mitotic segregation patterns of mtDNA alterations may be involved in the complex inheritance of NeuD and PsyD and in the ageing process. Therefore, more information is needed regarding the type of mtDNA alteration, the affected brain regions, the heteroplasmy levels, and their relationship with clinical phenotypes and the ageing process.

Funding

Hospital Universitari Institut Pere Mata; Institut d'Investigació Sanitària Pere Virgili; Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PI18/00514).

Keywords: Mitochondrial DNA, Mitochondrial diseases, Neurological diseases, Psychiatric diseases, Ageing, Postmortem

Abbreviations: mtDNA, Mitochondrial DNA; MitD, Mitochondrial disease/s; NeuD, Neurological disease/s; PsyD, Psychiatric disease/s; pSNV, Pathogenic single nucleotide variant; CN, copy number; DEL, deletion

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The human mitochondrial genome consists of a 16,569 bp molecule present in almost all cell types with some exceptions, the most significant being erythrocytes. On average, there are approximately 1,000 mtDNA molecules in a human cell, but the specific mtDNA CN depends on the energy requirements of each cell. Brain tissue has a high energy requirement, which leads to a large number of mitochondria in the brain.1 It is known that alterations in mtDNA cause MitD, a clinically heterogeneous group of disorders that arise as a consequence of mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction. The clinical characteristics of MitD show enormous variability, and although they can affect a single organ, most of them involve multiple organ systems often presenting with neurological disturbances. Moreover, there is increasing evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegeneration,2 in the development of psychiatric symptoms,3 and in the brain ageing process.4,5 The aims of this study were a) to determine the specific diagnoses or health conditions in which the presence of mtDNA alterations has been assessed in the human postmortem brain and b) to identify and summarize the specific mtDNA defects reported. For these purposes, we conducted a PubMed and Embase search for articles published before June 10, 2021, using several search strings and keywords, including postmortem, brain, neuron, glia, mtDNA, variant, mutation, and deletion.

Added value of this study

Our systematic review identified that mtDNA alterations have been investigated in human postmortem brain samples associated with ageing and disease, mostly in individuals with MitD, neurological, or psychiatric diagnoses. We report a comprehensive summary of the identified mtDNA alterations organized into three clinical categories (MitD, NeuD and PsyD) plus a miscellaneous clinical group and two further categories, including ageing and technical issues. pSNVs, alterations in mtDNA CN and mtDNA deletions have been reported in MitD. In NeuD, most of the studies investigated the presence of mtDNA deletions or differences in mtDNA CN between affected and nonaffected individuals, with conflicting results, while few studies evaluated mtDNA pSNVs. Similarly, pSNVs and altered mtDNA CNs were not consistently evaluated in PsyD; in contrast, several studies identified mtDNA deletions in some patients. Finally, mtDNA deletions have been recurrently associated with ageing. We also identified some studies that have explored mtDNA gene expression, oxidation and methylation.

Implications of all the available evidence

Among the three types of well-known mtDNA alterations (pSNVs, mtDNA CN and mtDNA rearrangements) that are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, only one or two of them were investigated in most studies. Most studies reported mtDNA alterations, demonstrating their presence in the postmortem brain of patients with MitD, NeuD and PsyD and the ageing process. With the currently available molecular techniques and bioinformatic tools, it is crucial to further investigate the presence of all types of mtDNA alterations in postmortem brain samples of patients with MitD, NeuD and PsyD in all age groups and in healthy individuals to shed light on the role of mtDNA in brain function, disease development and the ageing process. These studies should be conducted with current validated techniques to obtain unambiguous data regarding mtDNA alterations and associated heteroplasmy levels and are particularly relevant when measuring mtDNA CN. Because mitochondria can be acknowledged as a therapeutic target for ameliorating brain function, it is crucial to decipher the role of all types of mtDNA variations in health and disease.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

Mitochondria are membrane-bound organelles that generate most of the chemical energy needed to power the cell's biochemical reactions; this energy is stored as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules. Two distinct bilayer membranes separate the matrix of the mitochondria from the cytosol—the smooth outer membrane and the highly folded inner membrane—forming invaginated structures called cristae. In these cristae, ATP synthesis takes place by the oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS) through oxidoreductase complexes I-IV of the electron transport chain (ETC) and the ATP synthase enzyme of complex V. Mitochondria act as a signalling hub regulating cellular processes relevant to cell differentiation, cell proliferation, apoptosis and the immune response.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 The mitochondrial proteome is estimated to contain 1,500 proteins, most of which are under nuclear genome control.

Human mtDNA consists of a 16,569 bp circular DNA molecule that is maternally inherited and whose sequence and gene organization were published in 1981.11,12 It encodes 37 genes, including 13 protein subunits of the respiratory chain, 2 ribosomal units (rRNAs 12S and 16S) and 22 transfer (tRNA) genes. mtDNA also contains a noncoding control region of approximately 1,200 bp in length and is known as the displacement loop (D-loop) region, which regulates mtDNA transcription and replication. The 13 resulting proteins are crucial for the proper function of the respiratory chain even though they represent only a small fraction of the ∼100 subunits that constitute complexes I-V.13 Another peculiar feature of mtDNA is polyploidy. A uniform collection of mtDNA copies—either completely normal mtDNA or completely mutant mtDNA—is known as homoplasmy, while heteroplasmy refers to different proportions of normal and mutant mtDNA in a mitochondrion, cell, organ or tissue. The amount of mtDNA in a cell, known as the mtDNA content or mtDNA CN, usually varies from hundreds to thousands14 and depends on the cell function and the cell response to endogenous and exogenous agents.15 Tissues with high energy requirements contain large amounts of mitochondria in their cells and, accordingly, a high mtDNA CN. The central nervous system, cardiac and skeletal muscles, endocrine system, and liver and renal systems are among those with the highest energy requirements.10

mtDNA is composed of double-stranded DNA, comprising heavy strands (H) and light strands (L). The H-strand, which is guanine-rich, encodes 28 genes, while the L-strand, which is cytosine-rich, encodes the remaining 9 genes. Several characteristics differ between the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes: mtDNA is circular, small, has no introns, is not enveloped with proteins and is maternally inherited; in contrast, nuclear DNA (nDNA) is linear, has a large number of nucleotides (∼3.3 billion bp), has introns, is packaged into chromatin, undergoes recombination and is biparentally inherited. Both mtDNA and nDNA use the same deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) for DNA replication, and although mtDNA follows the universal codon usage rules when coding sequences are translated into proteins, there are some specific deviations: UGA codes for tryptophan instead of a stop codon, AGA and AGG are also stop codons, and AUA codes for methionine. Additionally, some nucleotide bases exhibit functional overlap between two genes, as they are the last base of one gene and the first base of the next gene.16 In the mitochondrial matrix, mtDNA forms nucleoids with mitochondrial transcription factor A, which acts to provide structure to the mtDNA genome.

Finally, the mtDNA mutation rate (the speed at which mutations are introduced) is much higher than that of nDNA. In animals, it is estimated that the mutation rate in mtDNA is ∼25-fold higher than that in nDNA.17 In humans, based on the appearance of de novo mtDNA variants in human pedigree studies, an ∼10-fold higher rate in mtDNA than in nDNA has been suggested.18 The molecular damage to mtDNA is thought to be due to the high levels of reactive oxygen species present in the mitochondrion, the high mtDNA replication levels, and the high coding rate of mtDNA, which is ∼93%.19 Additionally, this higher mutation rate suggests that many mtDNA variants may be subjected to poor selection, which can occur at the germline level or at the somatic level throughout life, implying that even though a specific variant is not detected in blood, a tissue commonly used in genetic testing, it cannot be ruled out that the variant is not present in other tissues or organs. Correspondingly, mtDNA alterations can lead to cellular energy impairment that might cause a disease or be implicated in the physiopathology of age-associated diseases or the ageing process itself.20

mtDNA and human ageing

The decline of mitochondrial functioning has been largely implicated in the ageing process and is characterized by a reduced density of mitochondria and reduced mitogenesis.21 In fact, the ageing process is strongly linked to noninherited mtDNA changes, mainly point variants and large deletions, that increase in frequency with age.22, 23, 24 Such changes, which originate as replication errors, accumulate in postmitotic tissues during ageing, leading to increased proportions of impaired mitochondria that may differ between cells and tissues.25 In the ageing brain, dysfunctional synaptic mitochondria leading to impaired neurotransmission and cognitive failure26 have been amply demonstrated,27,28 and mtDNA deletions correlate with mitochondrial respiratory chain malfunction.27,28 Thus, elucidating the temporal and spatial distribution of mutated mtDNA in the brain might resolve important questions regarding the importance of mtDNA changes in the ageing process.

mtDNA and disease

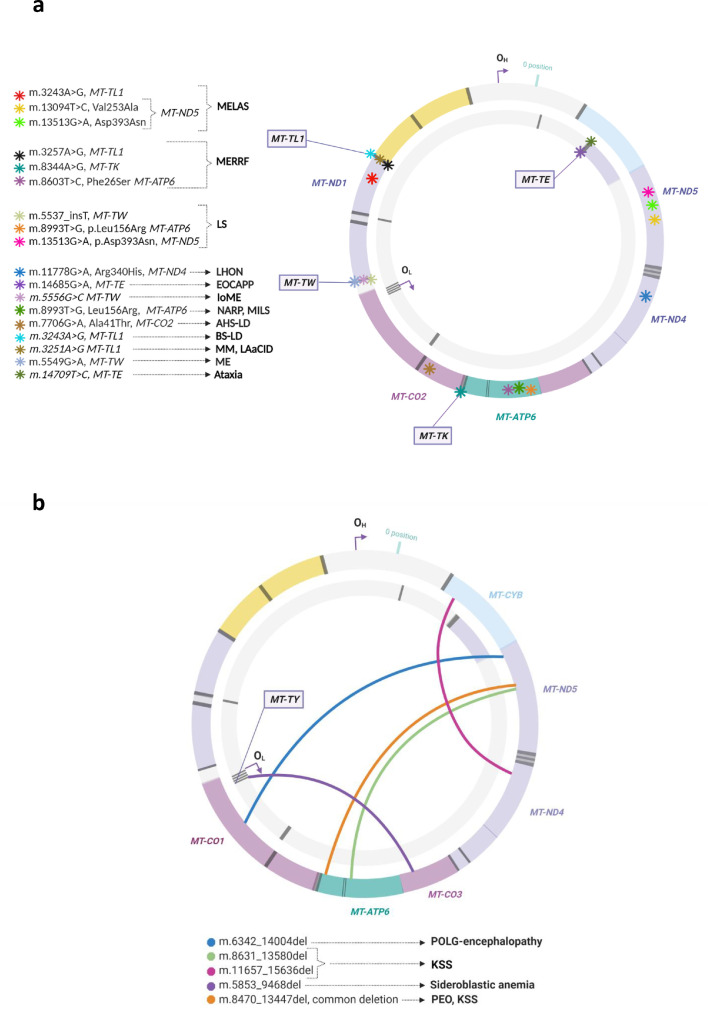

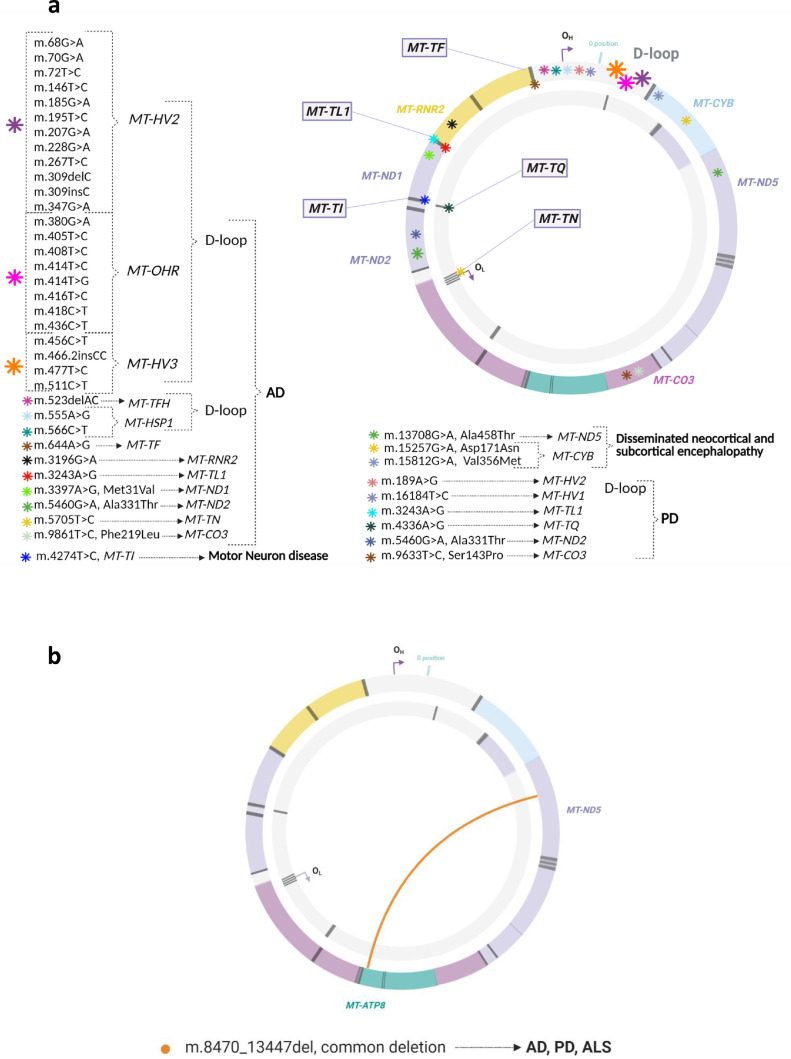

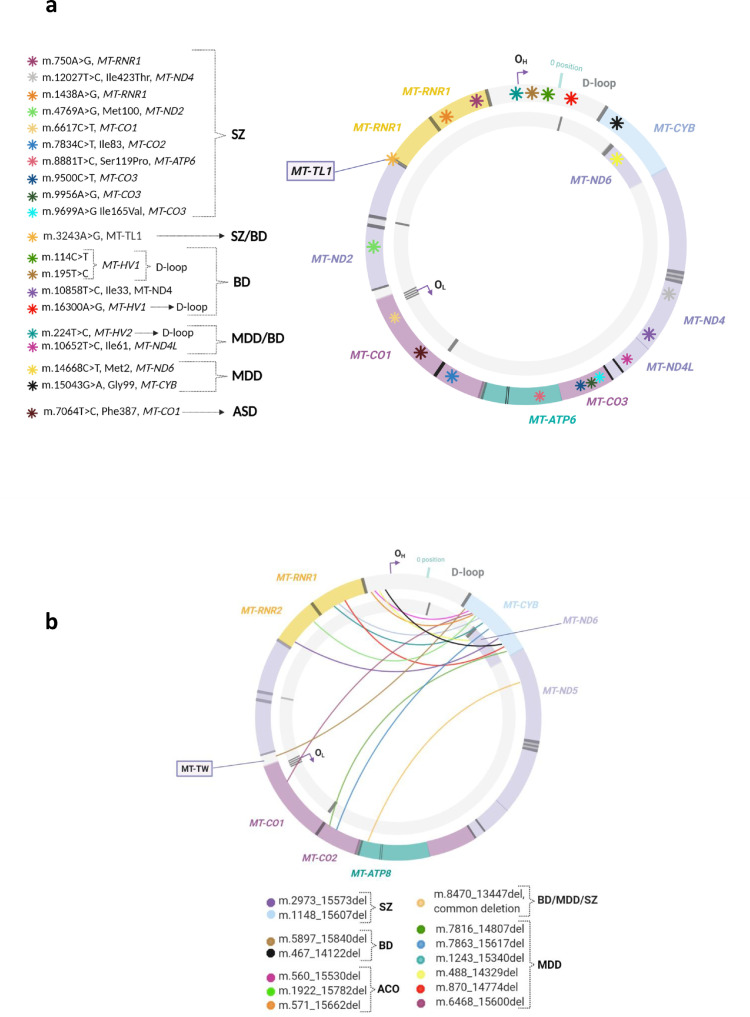

Given the nature of the genetic material and the dual genomic control of mitochondria, alterations occurring either in the nDNA or mtDNA sequence can potentially cause mitochondrial functional defects. Indeed, some are known to cause very heterogeneous diseases that together are called primary mitochondrial disease (MitD). More than 300 nuclear genes are known to cause MitD, although most adult patients exhibit variants in mtDNA. The mechanisms involved in these nuclear genes involve assembly factors, mitochondrial structure, coenzyme Q biosynthesis, protein synthesis, and mtDNA maintenance.29,30 However, this review focuses on MitDs associated with mtDNA pathogenic variants that include pathogenic single nucleotide variants (pSNVs), mtDNA rearrangements (mostly deletions), and altered mtDNA CNs. They can be either maternally inherited or occur de novo, and their pathogenic role can be established by taking advantage of the association between each variant and a specific phenotype.31 This was investigated by a recent analysis of 265 mtDNA SNVs in 483,626 individuals from the United Kingdom (UK) biobank, which has allowed the identification of 260 new mtDNA-phenotype associations, including type 2 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, adult height, and liver and renal biomarkers. Notably, this study identified a key role for mtDNA common and rare SNV variation (only homoplasmic) in many quantitative human traits and disease risks, with a particular emphasis on cardiometabolic and neurodegenerative diseases.32 mtDNA pSNVs can be observed in homoplasmy or heteroplasmy, while mtDNA deletions are always heteroplasmic, since within the deleted region, mtDNA consistently contain one or more tRNAs indispensable for the translation of the protein-associated mtDNA genes, which are essential for life. Known mtDNA pSNVs lead to syndromes such as mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibres (MERRF), neuropathy, ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa (NARP), and Leigh syndrome (LS).33, 34, 35, 36 mtDNA rearrangements are responsible for Kearns–Sayre syndrome (KSS), progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO), and Pearson's syndrome.37 These are considered the most typical MitDs associated with mtDNA alterations; however, there are many other diseases and human characteristics related to mtDNA variation, such as diabetes and hypertension, as well as ageing.31 In fact, it has been estimated that 1 out of 3,500–6,000 individuals are affected by or are at risk of developing a MitD.38,39 Human phenotypes associated with mtDNA alterations include extremely severe diseases that can be present from infancy to adulthood and can affect a single organ or multiple tissues, and most of them are included as rare diseases (ORPHANET, https://www.orpha.net/). In June 2021, the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (https://omim.org) catalogue40 included 33 phenotypic descriptions (Supplementary Table 1) in which the molecular basis is known to be associated with mtDNA alterations. The catalogue also included the 37 mtDNA genes (Supplementary Table 2) containing several allelic variants associated with human conditions. In addition, the human mitochondrial genome database (https://www.mitomap.org41) includes a large and growing number of variants, some of which are related to a wider constellation of phenotypes. Among the reported mtDNA base substitution disease variants, 431 entries are located in rRNA or tRNA genes, and 481 are located in coding regions or the noncoding (D-loop) control region. These include 52 rRNA/tRNA and 43 coding/D-loop variants that have been confirmed as pathogenic (on March 2021).41, 42, 43, 44 However, it is worth mentioning that most of the variants seem to have no effect and have been widely used as haplotype markers in evolutionary anthropology and population history, genetic genealogy, and forensic science in addition to medical genetics.45 Moreover, a group of phenotypes known as mtDNA maintenance defects or mitochondrial depletion syndromes must be noted; these are characterized by mtDNA depletion and/or the presence of multiple mtDNA deletions, resulting in inadequate energy production.46 These mtDNA defects are caused by pathogenic variants located in one of the 20 nuclear-encoded genes that are involved in mtDNA maintenance.47, 48, 49 The involvement of nuclear gene defects causing mitochondrial depletion syndromes is beyond the scope of this review and is discussed elsewhere.50,51 Another aspect that must be considered is that an altered mtDNA CN is associated with mitochondrial function and dysfunction, and consequently, several conditions have been associated with either increases or decreases in the mtDNA content.52

MitD refers to a heterogeneous group of phenotypes; the common clinical features include ptosis, external ophthalmoplegia, proximal myopathy and exercise intolerance, cardiomyopathy, sensorineural deafness, optic atrophy, pigmentary retinopathy, and diabetes mellitus. Regarding the central nervous system, phenotypes include fluctuating encephalopathy, seizures, dementia, migraine, stroke-like episodes, ataxia, and spasticity. Some MitD types affect only a single organ, while many others involve multiple organ systems,36,37 leading to clinical heterogeneity, a hallmark of MitD. The organs/tissues most often affected in MitD are the brain and skeletal muscle, but the heart, liver, peripheral nerves, gastrointestinal tract and endocrine system can also be involved. Therefore, it is relevant to identify the mtDNA defects present in the brain, their nature and prevalence, and the correlation between the genetic defects and the postmortem neuropathologic features to advance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of mitochondrial function in disease. Within this systematic review, we aim to summarize the main mtDNA alterations reported in postmortem human brain samples and the related phenotypes.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

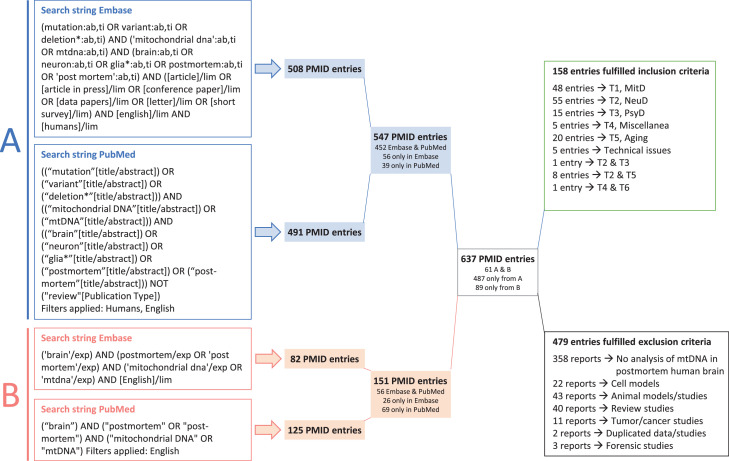

We examined PubMed and Embase for English language articles published from inception to June 10, 2021 using two search strings combining the following keywords: postmortem/post-mortem, brain, mitochondrial DNA/mtDNA, mutation, variant, deletion, neuron and glia, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.53 The specific search strings in both databases are shown in Figure 1. We examined the retrieved titles and abstracts and selected empirical studies based on the eligibility criteria. The literature search strategy, data collection, data extraction and appraisal were conducted independently by three authors (AV-P, JT and BKB). When there was no agreement, a fourth author (LM) contributed to gain consensus. The abstraction and summary of the main results of the studies were first performed independently by one of the three main authors and revised by the remaining authors.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for selecting published articles for review. The two search strategies used, the number of articles with PMID numbers obtained for each of them, and the result of combining them are shown. Those that met the inclusion criteria and those that were excluded and the groups to which they were assigned are indicated. The final number of articles included in each group after manual inclusion of references is indicated in brackets.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were included only if they reported results of mtDNA analyses in postmortem human brain tissue and were written in English. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) studies that did not report the results of mtDNA analyses in postmortem human brain tissue, ii) cell models, iii) animal models; iv) review studies; v) studies focused on brain tumours or cancer, vi) studies that reported duplicated data; or vii) forensic studies. No other restrictions were applied.

Review process

The combined search yielded 637 potentially eligible studies. Abstracts or full articles (if the eligibility criteria were not clearly stated in the abstract) were screened to decipher eligibility. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart depicting the specific information at the different stages of the systematic review, and Supplementary Table 3 provides the PRISMA checklist of items to include when reporting a systematic review.53 We discarded 479 reports, and a detailed examination was performed on the 158 remaining records and on others obtained from hand-searching references.

Data extraction

From eligible articles, we recorded the name of the first author, PMID number, publication year, number of patients and controls analysed, age, sex, disease or condition, brain region, technique used, main results regarding mtDNA variants, mtDNA CN and/or mtDNA rearrangements reported, and additional information.

Pathogenicity assignment of mtDNA variants

Pathogenicity status was collected based on the information present in the Mitomap and ClinVar databases when available.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in the study design, in the collection and interpretation of data, in the report writing, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Characteristics of the examined studies

The manuscripts fulfilling the inclusion criteria could be ascribed to the following 6 categories: 1) mitochondrial diseases (MitD), 2) neurological diseases (NeuD), 3) psychiatric diseases (PsyD), 4) other clinical conditions included in a miscellaneous group, 5) ageing, and 6) technical issues. Some reports could be ascribed to two groups, as they presented results from more than one category, and others were manually included after reading specific references of the included studies. A summary of the relevant data, number of evaluated subjects, age, sex, brain region/s studied, techniques used, and mtDNA alterations reported are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, while the technical issues are summarized at the end of this section. We screened the variants for putative pathogenic characteristics, and a selection of presumably pathogenic mtDNA variants is shown in Table 6, with pathogenicity information obtained from public databases.

Table 1.

Studies reporting the results of mtDNA analyses in postmortem brain samples of patients with mitochondrial diseases (MitD).

| Study reference (PMID) |

Patient/control characteristics | Disease (nuclear gene) |

Brain region | Technique | mtDNA alteration in brain | Additional information | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N P/C |

Age (y) in P/C |

Sex in P/C |

Variant | mtDNA CN | Rearrangements | |||||

| Laine-Menéndez et al. 2021 (34070501) |

1/1 | 43/37 | F/F | MM (TK2, c.323C>T, p.Thr108Met) |

FCtx, TCtx, OCtx, Hi, Amg, Th, Hy, Cb, pons, spinal |

qPCR | NR | No differences in mtDNA CN between P and C in brain tissue | NR | Low mtDNA content was observed in skeletal muscle, liver, kidney, small intestine, and particularly in the diaphragm. Heart and brain tissue did not show differences. mtDNA deletions were observed in skeletal muscle and diaphragm |

| Scholle et al. 2020 (32085658) |

1 | 46 | F | Optic neuropathy, sensorineural hearing loss and diabetes mellitus type I. Not MELAS | Pu, Cd, Mb, Th, Hy, Gic, GP, visual Ctx, pons, medulla oblongata, Ver, spinal, WM | RFLP, qPCR |

m.3243A>G, MT-TL1 Mutation load: >75% |

Higher heteroplasmy levels significantly correlated with lower mtDNA CN | NR | 60% level of heteroplasmy in the biceps brachii muscle |

| Geffroy et al. 2018 (29454073) |

1 | 32 | F | MELAS | NA | Fluorescence RFLP | m.3243A>G, MT-TL1 Mutation load: 92.1% |

NR | NR | - |

| Gramegna et al. 2018 (29348134) |

1/3 | 36/ Age-matched |

1/NA | MNGIE (TYMP, c.457G>A, p.G153S) |

FCtx, SN | NA | NR | mtDNA depletion in frontal GM and WM, and SN | NR | Severe mtDNA depletion in the P, also in smooth muscle and endothelial cells |

| Lax et al. 2016 (25786813) |

5 | 45 | 4M, 6F | MELAS MERRF |

FCtx, TCtx, OCtx | Pyrosequencing | MELAS, m.3243A>G, MT-TL1 MERRF, m.8344A>G, MT-TK Mutation load range (%): MELAS 79–94; MERRF 87–93 |

NR | NR | Mutation load did not vary between brain regions |

| Tzoulis et al. 2014 (24841123) |

8/15 | Infantile and adult/ age-matched C |

NA | ME (POLG) |

SN, SNC | qPCR, Long-range PCR, NGS |

The overall burden of mtDNA point mutations present at a frequency >0.2% was higher in P than in C in MT-HV2 and MT-CO3 and associated with disease duration | In homogenate tissue, apparent 20–30% mtDNA depletion was present in infantile P. Microdissected SN neurons showed a 40% lower mtDNA CN than the neurons of age-matched C | Neurons of both P and C harbored mtDNA DELs in the homogenate. In microdissected neurons mtDNA DELs were more prominent in P with longer disease duration | mtDNA analyses conducted in laser microdissected neurons and homogenate tissue |

| Giordano et al. 2014 (24369379) |

4/8 | 71/68 | NA | LHON | Optic nerve | NA | m.11778G>A, p.Arg340His, MT-ND1, present in affected P and unaffected carriers | Unaffected female carrier had a higher mtDNA CN than two C | NR | Unaffected mutation carriers showed higher mitochondrial DNA CN than their affected relatives and C |

| Lax et al. 2013 (23334599) |

1 | 45 | F | Early-onset cataracts, ataxia and progressive paraparesis | Optic nerve, basal ganglia, Cb, medulla oblongata, pons |

Sequencing, pyrosequencing |

m.14685G>A, MT-TE. Mutation load range (%): medulla oblongata 82, basal ganglia 68, Cb 58, pons 51, optic nerve 44 |

NR | NR | - |

| Tzoulis et al. 2013 (23625061) |

2/4 | 34/58 | NA | ME (POLG) |

Mesencephalon pons, Th, Str | Long-range PCR, nested PCR, qPCR |

NR | P neurons contained 50–60% lower mtDNA CNs than age-matched C neurons | DELs were detectable in P and C, and appeared to be more prominent in P | - |

| Lax et al. 2012 (22491194) |

3/1 | 53/- | M/- | KSS and ME (POLG, p.A467T, p.X1240Q; POLG, p.G848S, p.W748S) |

Dt WM and GM | Long-range PCR, sequencing, qPCR | NR | NR | The P with KSS showed the single m.11657_15636del (3978 bp) and heteroplasmy levels in WM were higher than the 60% threshold, thus considered pathogenic. In this P, heteroplasmy levels in WM where higher than in GM. The P with POLG mutations showed multiple mtDNA DELs, and heteroplasmy levels were lower than in the P with KSS |

mtDNA analyses conducted in laser microdissected regions. The P with KSS showed decreased immunoreactivity of complex I and COX compared with complex II |

| Lax et al. 2012 (22249460) |

14/- | 42/- | 5M/9F | MELAS (7), MERRF (1), MELAS/LS (1), KSS (1), Ataxia-retinopathy, arPEO (3) | Dt, CbCtx, IO | qPCR, pyrosequencing | m.3243A>G; m.8344A>G; m.14709T>C; m.13094T>C. Mutation load range %: IO 44–93, CbCtx 47–95, Dt 51–95 | NR | Single and multiple large-scale mtDNA DELs. Mutation load %: IO 68, CbCtx 20–68, Dt 25–44 | Neuronal cell loss occurred independently of the level of mutated mtDNA present within surviving neurons |

| Brinckmann et al. 2010 (20976001) |

1/4 | 16/16-32 | F/NA | MERRF | Mcer, Ox, Mb, Th, Cd, GP, Pu, Ic, Hy, Hi, sensomotor Ctx, visual Ctx, WM, Chpx, Ver, folia of Cb, medulla of Cb, pons, SN | qPCR, pyrosequencing | m.8344A>G, MT-TK. Mutation load (%) Mcer 98, Ox 97, Mb 94, Th 89, Cd 95, GP 94, Pu 95, Ic 95, Hy 94, Hi 94, sensomotor Ctx 96, visual Ctx 96, white matter 95, Chpx 100, Ver 97, folia of Cb 97, medulla of Cb 93, pons 95, SN 91 |

mtDNA CN increased between 3–7-fold in affected brain tissues compared to nonaffected tissues | NR | Mutation load (%): Skeletal muscles 97–98, diaphragm 97, external ocular muscles 95, heart 93, renal cortex 99, renal medulla 95, adrenal cortex 100, lung 98, liver 67, pancreas 73, spleen 98, stomach 98, ileum 97, bladder 100, uterus 100, ovary 100, adipose tissue 99, skin 100 |

| Sanaker et al. 2010 (19744136) |

1 | 64 | M | loME | OCtx, TCtx, CbCtx | Sequencing, PCR-RFLP | m.5556G>C, MT-TW. Mutation load (%): Octx 34, TCtx 32, CbCtx 12 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): skeletal muscle 70, heart muscle 27, kidney 26, liver 27, adrenal cortex 5, pancreas 8, lung 2, spleen 4 |

| Zsurka et al. 2008 (18716558) |

1/30 | 17/28 | M/NA | ME (POLG) |

NA | Long-range PCR, qPCR |

NR | Progressive decrease of mtDNA CN in the disease course in P but not significantly different from that in C | Presence of the m.6342_14004del (7662 bp) | - |

| Götz et al. 2008 (18819985) |

2/2 | NA | NA | MDS (Patient 1: TK2, c.739C>T, p.R172W Patient 2: TK2, c.898C>T, p.R225W) |

Ctx, Cb, Basal ganglia | qPCR | NR | Severe brain mtDNA depletion in patients with R172W but not with R225W mutation. Higher mtDNA content in the Cb of the patient with R2 25W mutation |

NR | mtDNA depletion present in muscle and liver in all patients |

| Rojo et al. 2006 (16525806) |

1 | 64/- | M | NARP-MILS | Pu, brain stem, Th, Ctx | Southern blot, PCR-RFLP |

m.8993T>G, p.Leu156Arg, MT-ATP6 Mutation load (%): brain stem and Ctx 89, Pu and Cb 90, Th 91 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): blood 75, muscle 87 |

| Betts et al. 2006 (16866982) |

2 | 47 | F | MELAS | Chpx, Hi, CbCtx, Dt, GPI, OCtx, FCtx, GPI |

PCR-RFLP using radiolabeled nucleotides |

MELAS, m.3243A>G, MT-TL1 Mutation load in patient 1 and 2, respectively (%): chpx 81 and NA, Hi 79 and 92, CbCtx 54 and 96, Dt 75 and NA, GPI 70 and 93, Octx 69 and 93, FCtx NA and 92 |

NR | NR | Mutation load was higher in COX-deficient than in COX-positive microdissected cells from Hi, chpx and skeletal muscle. Mutation load varied considerably between different cells of the same region |

| Matthes et al. 2006 (16856911) |

1 | 19 | M | Sideroblastic anemia | NA | Long-range PCR, sequencing, qPCR | NR | NR | Presence of the m.5853_9468del (3614 bp). Mutation load (%): 70 |

Mutation load (%): Liver 90, skeletal muscle 75, pancreas 85, peripheral blood 80 |

| Ferrari et al. 2005 (15689359) |

1/2 | 19/age-matched | M/- | AHS (POLG1, c.1399G>A, p.A467T) |

NA | NA | NR | 30% mtDNA content reduction | NR | - |

| Pistilli et al. 2003 (14608542) |

1 | 36/- | F | KSS | FCtx, PCtx, TCtx, OCtx, Cb, basal ganglia, brain stem | Sequencing, Southern blot, competitive PCR using radiolabeled nucleotides | NR | NR | Presence of the m.8631_13580del (4949 bp). DEL load (%): FCtx 54; Octx 54; TCtx 58; PCtx 59; basal ganglia 75; Cb 88 |

- |

| Uusimaa et al. 2003 (12612282) |

1 | 7/- | F | AHS-like disease | NA | CSGE + sequencing, PCR-RFLP using radiolabeled nucleotides |

m.7706G>A, p.Ala41Thr, MT-CO2. Mutation load: 91% |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): blood 87, heart 87 |

| Kirby et al. 2003 (14520659) |

3 | 31 | 2M, 1F | LS | Medulla oblongata, pons, Cb, basal ganglia, Th, midbrain, Hi, FCtx, Chpx | PCR-RFLP with radiolabeled nucleotides | m.13513G>A, p.Asp393Asn, MT-ND5 Mutation load (%): 73 |

NR | NR | - |

| Jiang et al. 2002 (12174968) |

1 | - | - | LS | NA | NA | m.8993T>G, Leu156Arg, MT-ATP6 Mutation load (%): 89 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): muscles 85, lymphocytes 72 |

| De Kremer et al. 2001 (11241464) |

1/20 | 4/NA | 1/NA | Barth syndrome-like disorder | NA | PCR-RFLP sequencing |

m.3243A>G, MT-TL1. The mutation was heteroplasmic in brain but not quantified |

NR | NR | The mutation was also heteroplasmic in all the tissues analyzed: blood, skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and liver |

| Moslemi et al. 1999 (10408540) |

1 | 61 | F | PEO | WM, FCtx, Th, Pu Cd, SN, CbCtx | Long-range PCR, Southern blot | NR | NR | Multiple DELs (25), most of them were less than 8 kb. The CbCtx showed the lowest mutation load %. The common DEL was found in all the specimens | DELs present in all brain regions, skeletal muscle samples and myocardium |

| Nagashima et al. 1999 (10208283) |

1 | 43 | F | LS | FCtx | PCR-RFLP | m.8993T>G, p.Leu156Arg, MT-ATP6. Mutation load (%): 95 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): liver 98, muscle 90, heart 91, kidney 99, pancreas 93 |

| Santorelli et al. 1998 (9851442) |

1 | 12 | F | MERRF | NA | Sequencing with radiolabeled nucleotides | m.8344A>G, MT-TK, mutation load (%): 92%. m.8603T>C, Phe26Ser, MT-ATP6, m.3257A>G MT-TL1 |

NR | NR | - |

| Di Trapani et al. 1997 (9266144) |

1 | 27/- | M | MELAS | NA | PCR-RFLP | m.3243A>G, MT-TL1. Mutation load: 84% |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): liver 79, kidney 86, skeletal muscle 83, cardiac muscle 83 |

| Zhou et al. 1997 (9315896) |

1 | 14 | F | MERRF | CbCtx, Dt, IO, FLV | PCR-RFLP | m.8344A>G, MT-TK. Mutation load (%): between 81 and 98. Similar % in soma, neuropil, glia and homogenate tissue. |

NR | NR | Analyses of homogenate issue and individual neurons |

| Suomalainen et al. 1997 (9153451) |

2 | 67 | F | adPEO | FCtx, TCtx, Cd, Cb | Southern blot | NR | NR | Multiple DELs ranging from 0.5 kb to 10.0 kb DEL load (%): FCtx 50, TCtx 40, Cd 60, Cb 10 |

Mutation load (%): Skeletal muscle 50, kidney 10, liver 10 |

| Santorelli et al. 1997a (9299505) |

1 | 45 | M | MELAS | NA | PCR-RFLP | m.13513G>A, p.Asp393Asn, MT-ND5. Mutation load (%): 73 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): muscle 68 |

| Santorelli et al. 1997b (9266739) |

1 | 1.4 | M | MM, LS | Basal ganglia, SN, brain stem | Southern blot PCR-RFLP sequencing |

m.5537_insT MT-TW. Mutation load (%): ≥98 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%) in other tissues: >95 |

| Kaido et al. 1996 (8870835) |

1 | 53/- | F | MELAS | FCtx, Pu, GP | Southern blot | m.3243A>G, MT-TL1. Mutation load (%): FCtx 89, Pu 86, GP 80 |

NR | NR | - |

| Sanger et al. 1996 (8652018) |

1 | 14/- | F | MERRF | CbCtx, FCtx, Cd, Pu | PCR-RFLP using radiolabeled-nucleotides |

m.8344A>G, MT-TK. Mutation load (%): CbCtx 97, FCtx 88, Cd 88, Pu 88 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): blood 75, muscle 86–93, spinal cord 83, medulla 87 |

| Melberg et al. 1996 (8937533) |

1 | 20 | M | MELAS-like syndrome | FCtx | Southern blot for variants m.3243A>G and m.8344A>G | No presence of these two variants | NR | NR | - |

| Houshmand et al. 1996 (8786060) |

1 | 14 | F | MM, lactic acidosis and complex I deficiency | NA | PCR-RFLP | m.3251A>G MT-TL. Mutation load (%): 90 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): muscle 94, fibroblast 93, heart 79, liver 80 |

| Oldfors et al. 1995 (8525809) |

1 | 18/- | M | MERRF | FCtx, PCtx, TCtx, OCtx, frontal WM, Pu, pallidum, Th, pons, IO, CbCtx, Dt | PCR-RFLP using radiolabeled-primer | m.8344A>G, MT-TK. Mutation load (%): FCtx 95, PCtx 95, TCtx 95, Octx 95, Pu 96, pallidum 96, Th 94, pons 94, IO 94, low. Brain stem 94, CbCtx 95, Dt 93 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): skeletal muscle 97, myocardium 97, aorta 97, subcutaneous adipose tissue 95, liver 95, pancreas 91, spleen 95, lymph node 93, bone marrow 94, testis 99, adrenal gland 97, thyroid gland 98 |

| Nelson et al. 1995 (7695240) |

1 | 53/- | M | ME | Ctx, Cb | Southern blot | m.5549G>A, MT-TW Mutation load (%): Ctx 87, Cb 88 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): blood 40, muscle 83–86, myocardium 93, kidney 93, lung 79, liver 77, optic nerve 51 |

| Brockington et al. 1995 (7561952) |

1 | 41 | M | KSS | TCtx, OCtx, Cb | Southern blot | NR | NR | Presence of the common DEL. DEL load (%): TCtx 62, OCtx 70, Cb 17 |

Mutation load (%): quadriceps 91, psoas 72, diaphragm 75, cardiac muscle 25, kidney 21, liver 84, lung 18, spleen 0, testis 0, blood 0 |

| Sweeney et al. 1994 (8133313) |

1 | 18 | M | LS | Cb, CbCtx | PCR | m.8993T>G, p.Leu156Arg, MT-ATP6 Mutation load (%): Cb 97, CbCtx 97 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): blood 81, quadriceps muscle 99, extraocular muscle 97, cardiac muscle 97, liver 99, kidney 98, blood 72 |

| MacMillan et al. 1993 (8351017) |

2 | 24 | F | MELAS | PCtx GM, Octx GM, PCtx WM, Cd, Cb, pons, | PCR-RFLP | m.3243A>G, MT-TL1. Mutation load (%): PCtx GM 79, Octx GM 80, PCtx WM 62, Cd 73, Cb 72, pons 70 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): psoas muscle 82, oculomotor muscle 59, cardiac atrium 86, myocardium 67, oesophagus 84 |

| Love et al. 1993 (8326463) |

2 | 23, 16 | F | MELAS | FCtx, TCtx, pons, PCtx, OCtx | PCR-RFLP, sequencing with radiolabeled primers | Case 1: m.3243A>G, MT-TL1. Mutation load (%): FCtx 46, TCtx 40, PCtx 33, pons 30. Not detected in OCtx. Case 2: neither m.3243A>G nor m.3271T>C, MT-TL1, was present. |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%) in case 1: liver 78, thenar muscle 77, myocardium 73. Poor correlation between mutation load and distribution of histological lesions |

| Tanno et al. 1993 (8170566) |

2 | 29, 30 | M, F | MERRF | FCtx, TCtx, CbCtx | PCR-RFLP | 8344A>G, MT-TK. Mutation load (%): FCtx 97, TCtx 98, CbCtx 97 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): heart 96, kidney 96, adrenal gland 93, liver 94, muscle 96–99, leukocytes 93 |

| Shiraiwa et al. 1993 (8138807) |

1 | 27 | F | MELAS | FCtx, TCtx, PCtx, OCtx, Cd, Pu, pallidum, Th, frontal WM, Pit, CbCtx, Dt | PCR | m.3243A>G, MT-TL1. Mutation load (%): Pit 95; FCtx, TCtx, PCtx and Octx 85–88; Cd, Pu, pallidum and WM 73–79 |

NR | NR | - |

| Tatuch et al. 1992 (1550128) |

1 | 0.6 | F | LS | NA | Southern blot PCR-RFLP |

m.8993T>G, p.Leu156Arg, MT-ATP6. Mutation load (%): >95 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): >95 in fibroblasts, kidney and liver |

| Suomalainen et al. 1992 (1634620) |

1 | 60 | F | PEO and MDD | FCtx, basal ganglia | Southern blot PCR |

NR | NR | Presence of several DELs. Most of the DEL breakpoints were between ∼m.11,900 and m.12,600. DEL sizes between ∼2.0 to 10 kb | Mutation load (%): kidney 10, liver 20, extraocular muscle 40, heart 40, vastus lateralis muscle 60. No DELs in blood |

| Lombes et al. 1991 (1849240) |

3 | 5, 2, 0.5 | M | LS and COX deficiency | NA | Southern blot Northern blot |

NR | mtDNA/nDNA content was higher in P than in C (in P3, 4.6 times higher) | No mtDNA DEL detected | mRNA levels of the mtDNA encoded COX subunits was decreased compared to the nDNA encoded subunits |

| Ciafoloni et al. 1991 (1922812) |

1 | 26 | M | MELAS | NA | Southern blot PCR-RFLP |

m.3243A>G, MT-TL1 Mutation load (%): 84 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): muscle 83, liver 79, heart 83, kidney 86 |

| Enter et al. 1991 (1684568) |

1 | 12 | F | MELAS | NA | Southern blot PCR-RFLP |

m.3243A>G, MT-TL1 Mutation load (%): 80 |

NR | NR | Mutation load (%): cardiac muscle 70, skeletal muscle 30, liver 70, diaphragm 60 |

| Bordarier et al. 1990 (2359483) |

1 | 17 | F | KSS | NA | Southern blot | NR | NR | DEL located between positions ∼ m.8,200 and m.13,000 (±400 bp) | The DEL was also found in muscle and spinal cord |

C: control; DEL: deletion; F: female; GM: gray matter; M: male; mtDNA CN: mitochondrial DNA copy number; N: number of subjects; NA: information not available; NR: not reported; P: patient; y: years; WM: white matter.

ad/arPEO: autosomal dominant/autosomal recessive progressive external ophthalmoplegia; AHS: Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome; KSS: Kearns-Sayre syndrome; LHON: Leber hereditary optic neuropathy; LoME: late onset mitochondrial encephalomyopathy; LS: Leigh's syndrome; MDD: major depressive disorder; MDS: mitochondrial depletion syndrome; ME: mitochondrial encephalomyopathy; MELAS: mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes; MERRF: myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers; MILS: maternally inherited LS; MM: mitochondrial myopathy; MNGIE: mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy; NARP: neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa; POLG: DNA polymerase subunit gamma, TK2: thymidine kinase 2.

Amg: amigdala; Cb: cerebellum; CbCtx: cerebellar cortex; Cd: caudate nucleus; Chpx: choroid plexus; Ctx: cortex; Dt: dentate nucleus; FCtx: frontal cortex; FLV: frontal horn of the lateral ventricle; Gic: internal capsula, genu; GP: globus pallidus; GPI: internal globus pallidus; Hi: hippocampus; Hy: hypothalamus; Ic: internal capsule; IO: inferior olive; Mb: mammillary bodies; Mcer: middle cerebral artery; OCtx: occipital cortex; Ox: optic chiasm; PCtx: parietal cortex; Pit: pituitary gland; Pu: putamen; SN: substantia nigra; SNC: substantia nigra, pars compacta; Spinal: spinal cord; Str: striatum; TCtx: temporal cortex; Th: thalamus; Ver: vermis of cerebellum.

CSGE: conformation-sensitive gel electrophoresis; NGS: next-generation sequencing; qPCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; RFLP: restriction fragment length polymorphism.

ATP6: ATP synthase subunit 6; CO2: cytochrome c oxidase II; CO3: cytochrome c oxidase III; HV2: hypervariable segment 2; MT-: mitochondrially encoded gene; ND1: NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 1; TE: tRNA-Glu; TK: tRNA-Lys; TL1: tRNA-Leu 1; TW: tRNA-Trp.

Table 2.

Studies reporting results of the mtDNA analyses in postmortem brain samples of patients with neurological diseases (NeuD).

| Study reference (PMID) |

Patient/control characteristics |

Disease (N) |

Brain region | Technique | mtDNA alteration | Additional findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N P/C |

Age (y) in P/C | Sex (M/F) |

Variant | mtDNA CN | Rearrangements | |||||

| Castora et al. 2020 (31561357) |

40/40 | NA | NA | AD (40) | PCtx, TCtx, Cd, Hi | PCR-RFLP | 6 AD P showed the m.9861T>C variant compared to none in C. Mutation load %: between 11 and 95 |

NR | NR | m.9861T>C was found in multiple regions, with the highest mutation load % occurring in PCtx and TCtx |

| Chen et al. 2020 (31689514) |

20/15 | 49-81/75 | 21/14 | MD (12) PD (8) C (15) |

SN | qPCR | NR | High mtDNA CN in healthy aged TH-positive neurons of C, despite showing similar DEL levels as P with PD. mtDNA CN was significantly lower in neurons of P with MD showing mtDNA point mutations or multiple deletions and in P with PD. Data showed evidence of mtDNA depletion in PD neurons, with large individual diversity in cases. |

DELs in MT-ND4 were detected in healthy TH-positive neurons of aged C. Comparable DEL levels in MT-ND4 were found in the cases with multiple mtDNA DELs and in P with PD. Prominent MT-ND1 DELs were detected in neurons from cases with multiple DELs. They were also present in older C and P with PD; however, with lower levels. |

- |

| Kim et al. 2020 (32005289) |

34/25 | NA | NA | ALS (34) AD (10) C (15) |

Ctx | Aldehyde reactive probe-based assay, ELISA |

NR | NR | NR | Apurinic/apyrimidinic sites (abasic sites) did not differ between ALS and C. Levels of oxidized mtDNA did not differ between ALS and C. mtDNA analyses were conducted in laser-microdissected neurons |

| Thubron et al. 2019 (31388037) |

44/30 | 79/77 | 36/38 | AD (34) MCI (10) NCI (30) |

PCtx, FCtx, Cb | qPCR | NR | 48% mtDNA CN reduction in PCtx of nondiabetic AD vs. nondiabetic NCI. No reduction observed in diabetic AD compared to diabetic NCI |

NR | The lowest mtDNA CN level was observed in Cb, the highest in PCtx, both in NCI. Higher mtDNA CN was observed in all brain regions of diabetic vs. nondiabetic cases, irrespective of cognitive status |

| Alvarez-Mora et al. 2019 (30887649) |

2/3 | 93,97/73-83 | NA | FXTAS (1) no-FXTAS (1) C (3) | Ver, Dt, PCtx, TCtx, Th, Cd, Hi | ddPCR | NR | mtDNA CN in Ver, Dt, PCtx and TCtx was descreased in FMR1 premutation carriers with FXTAS than in C but no differences were detected in Th, Cd and Hi. P with FXTAS showed lower mtDNA CN than Cs | NR | - |

| Soltys et al. 2019 (30359878) |

10/20 | 82/80 | 11/19 | AD (10) HpC (10) C (10) |

Cb, TCtx | RMC assay, ddPCR |

mtDNA mutation frequencies were similar in all three groups in both brain regions | mtDNA CN depletion observed in TCtx of AD P vs. HpC or C. No mtDNA CN variation in Cb between all three groups |

NR | - |

| Strobel et al. 2019 (30475765) |

22/10 | 75/70 | 16/16 | AD (22) C (10) |

Hi, Cb | qPCR | NR | NR | In C, higher rates of mtDNA DELs were observed in astrocytes and microglia of the Hi compared to brain stem and Cb | - |

| Bury et al. 2017 (29149768) |

6/6 | 76/84 | Ratio 5:1 | PD (6) C (6) |

PPN | qPCR | NR | Significant mtDNA CN increase in PPN cholinergic neurons from PD P (10.7%) vs. those from C (7.0%) | mtDNA DEL levels were significantly increased in PPN cholinergic neurons from PD P (21.6%) vs. those from C (17.2%) | mtDNA DELs correlated with Braak staging in PD |

| Wei et al. 2017 (28153046) |

902/ 461 |

69/59 | 765/ 598 |

AD (282) CJD (181) DLB-PD (89) FTD-ALS (236) Other (114) C (461) |

Cb, Ctx, other | Exome sequencing | No evidence of disease association with homoplasmic or heteroplasmic rare variants | mtDNA CN was significantly lower in AD and CJD P. Positive correlation between age and mtDNA CN in CJD P |

NR | No correlation between mean levels of heteroplasmy, total number of heteroplasmic variants or variant pathogenicity score with age or disease group |

| Nido et al. 2018 (29257976) |

2/NA | NA | NA | PD (2) | SN | NGS | Sequence heteroplasmy was significantly different between deleted and nondeleted mtDNA populations for 4/55 of the DELs. 11.3% of the analysed positions had a heteroplasmic frequency significantly different between deleted and nondeleted mtDNA populations |

NR | The 20 microdissected neurons showed 373 unique DELs (only 31 previously annotated). Each neuron contained on average 38.2 ± 29.8 distinct DELs. Mean size deletion was 5080 ± 2367 bp. The common DEL was detected in 15/17 neurons and was the most prevalent DEL in 6 neurons | 20 single laser-microdissected neurons were evaluated |

| Flones et al. 2017 (29270838) |

18/11 | 79/74 | 17/12 | PD (18) C (11) |

FCtx, SN, Cb, Hi, Pu | qPCR | NR | There was no significant difference between C and PD for mtDNA CN in Pu or Hi | Only dopaminergic neurons from the SN harboured significantly higher mtDNA DEL levels | 1189 single laser-microdissected neurons were evaluated. Neuronal complex I deficiency did not correlate with mtDNA damage |

| Dölle et al. 2016 (27874000) |

10/22 | 82/56 | 21/11 | PD (10) C (22) |

SN, FCtx, CbCtx | qPCR, NGS-(4,767 bp) | The mean load of heteroplasmic SNVs was 33.14%/1,000bp per neuron, and most of these clustered in the low-frequency spectrum in both PD and C. The overall burden of heteroplasmic SNVs was similar in PD and C. The proportion of G:C to T:A transversions was also similar in the two groups |

mtDNA CN was similar in PD and C in SN; however, the subset of neurons with high mtDNA depletion (<10,000 copies/cell) was 14% in PD and 2.7% in C (p=0.01). No differences were observed in FCtx or CbCtx |

SN neurons from PD contained significantly higher mtDNA DEL levels than C. The proportion of neurons with DEL levels exceeding 60%, was 21.4% in PD and 10.8% in C. mtDNA DEL levels were generally low in frontal neurons and Cb of both PD and C |

871 single laser-microdissected neurons were evaluated. In SN but not in FCtx or CbCtx, DELs and mtDNA CN showed a positive correlation with age; DEL was a predictor of mtDNA CN |

| Chen et al. 2016 (27299301) |

13/12 | 81/82 | NA | AD (13) C (12) |

FCtx | NGS, qPCR |

Similar heteroplasmy levels were observed in some mtDNA positions in AD P and C | NR | DELs were increased in AD P (9%) vs. C (2%). Rearrangement rate was higher in AD P (18%) than in C (7%). The common DEL was detected in most samples but at low % (1.5%) |

Different numbers and types of mtDNA rearrangement fragments were detected depending on the sequencing coverage depth |

| Gatt et al. 2016 (26853899) |

81/33 | 79/80 | 67/47 | PD (41) PDD (40) C (33) |

PFCtx | qPCR | NR | mtDNA CN was significantly reduced (18%) in PDD vs. C. Nonsignificant decrease was observed in PD |

NR | Although mtDNA CN was reduced in PDD, mitochondrial biogenesis was unaffected, as the expression of mitochondrial proteins in PDD and C was similar |

| Blanch et al. 2016 (26776077) |

26/18 | NA | 23/21 | AD (16) PD (10) C (18) |

Ent, SN | PQ, qPCR |

NR | NR | NR | Increased 5-methylcytosine levels observed in the D-loop in Ent of AD P vs. C. Lower 5-methylcytosine levels observed in the D-loop in SN of PD P vs. C |

| Coxhead et al. 2016 (26639157) |

180/40 | 78/77 | 128/92 | IPD (180) C (40) |

SNC, FCtx | NGS | The mean heteroplasmic variant burden differed between PD P and C in both SNC and FCtx | NR | NR | Nonsignificant correlation of heteroplasmy with age. Increased heteroplasmic variation was observed in COX genes |

| Grunewald et al. 2016 (26605748) |

10/10 | 76/75 | 5/5 | IPD (10) C (10) |

SN | qPCR | NR | mtDNA CN was reduced (73.1%) in IPD P vs. C. 7S D-loop mtDNA CN was reduced (91%) in IPD P vs. C |

mtDNA DEL prevalence did not differ between IPD P and C | - |

| Rice et al. 2014 (24448779) |

10/9 | 79/59 | 12/22 | AD (10) | Hi | qPCR | NR | mtDNA CN was significantly reduced in PyNs from AD. CN in other neuronal cells was not significantly different between P/C | Deletion levels were not significant | - |

| Azakli et al. 2014 (23872536) |

1/0 | 36 | 0/1F | MTLE-HS (1) | Hi (6 regions) | Pyrosequencing | The number of heteroplasmic variants was higher in the CA2 region and accumulated in MT-ND2, MT-ND3 and MT-ND5 genes. m.3563insC, p.Trp86>fs was suggested to be studied in other MTLE-HS patients |

NR | NR | Hi contained more heteroplasmic variants than blood |

| Müller et al. 2013 (23566333) |

14/14 | 78/73 | NA | PD (7) AD (7) C (14) |

SN, Hi | qPCR | NR | In PD, mtDNA CN did not differ significantly between LB+ and LB- neurons. In AD, mtDNA CN did not differ significantly between tau protein+ and tau protein- neurons |

In SN, DEL levels differed between P with LB+ neurons (40.5%), LB- neurons (31.8%) and C (25.6%), p<0.005. In Hi, DEL levels did not differ between groups, independent of disease status and cell type (tau protein + or -) |

2–6 single laser-microdissected neurons were evaluated per patient/control |

| Krishnan et al. 2012 (21925769) |

10/6 | 76/76 | NA | AD (10) C (6) |

Hi | qPCR, Long-range PCR + sequencing |

NR | NR | mtDNA DEL levels were higher in COX-deficient neurons (57%) than in COX-normal neurons (9%) in AD P and in C (48% and 24%, respectively). No differences were observed in COX-deficient neurons from AD P and C. mtDNA DELs ranged in size from 3670 to 6088 bp. mtDNA DELs accumulated with age |

- |

| Keeney et al. 2010 (20504367) |

10/7 | NA | NA | ALS (10) AD (1) C (6) |

Cb, Ctx | qPCR | NR | There were no differences in ND2 CN between P and C | There was an approximate doubling of DELs for ND4 and a consistent increase for CO3. Two P showed greater abundance in ND4 DELs with higher CN levels. Purkinje neurons showed low levels of DELs | Single laser-microdissected neurons from cervical spinal cord, anterior gray matter and Cb were evaluated |

| Naydenov et al. 2010 (20740286) |

32/31 | 75/71 | NA | PD (32) | Pu, Cb | qPCR | NR | Dopamine led to a 25% downregulation of mtDNA levels and L-Dopa caused an increase in mtDNA levels. In dyskinetic-PD, lower mtDNA levels in early disease processes were found. Pu showed a 50% reduction and a significant negative correlation with L-DOPA/year |

Pu from dyskinetic-PD showed a higher % of deletions and a correlation with mtDNA levels (↓mtDNA levels↑mtDNA deletions in PD and dyskinetic-PD) | - |

| Coskun et al. 2010 (20463402) |

38/25 | NA | NA | AD (13) DS (11) DSAD (14) C (25) |

FCtx | PNA campling PCR, qPCR, sequencing-(1,115 bp) | The frequency of mtDNA control region mutations was significantly higher in AD than in C. m.414T>G/ was found in 65% of AD but not in C, and in 57% of DSAD but not in DS. Other heteroplasmic mutations common in AD reported: m.68G>A, m.70G>A, m.72T>C, m.185G>A, m.207G>A, m.228G>A, m.309delC, m.309insC, m.408T>C, m.414T>C, m.418C>T, m.466.2insCC |

mtDNA CN of AD brains was significantly lower than age-matched C. Additionally, mtDNA CN of DSAD was significantly lower than age-matched C. mtDNA CN declined with age in C |

NR | AD-like neuropathology was present in AD and DSAD but not in DS. The frequency of somatic mutations in the regulatory control region increased with age in the normal brain (p=0.0029). The MT-ND6 to MT-ND2 transcript ratio did not change with age but was significantly lower in AD, DSAD and DS compared to C. Thus, reduced mtDNA L-strand transcription level was associated with intellectual disability and dementia. β-Secretase activity was associated with some mtDNA alterations |

| Campbell et al. 2010 (21446022) |

13/10 | 55/74 | NA | MS (13) C (10) |

Ctx | Long-range PCR, qPCR, sequencing | NR | NR | DELs were evident in 66% of normal appearing gray matter regions and in 53% of lesioned regions of MS P and in 16% of C. Multiple DELs were observed t in respiratory-deficient laser microdissected pooled neurons when compared to neurons with intact complex IV activity. Heteroplasmy DEL levels were also increased in respiratory-deficient neurons compared to neurons with intact complex IV activity | Single laser-microdissected neurons from WM and GM were evaluated. No differences in DEL heteroplasmy levels between WM and GM. DELs were supposed to be pathogenic because they contained MT-CO1 and MT-CO2 catalytic subunits |

| Arthur et al. 2009 (19775436) |

8/10 | 78/67 | 12/6 | sPD (8) C (10) |

FCtx and SN | Surveyor nuclease assay, qPCR | Nonsignificant variation in heteroplasmy levels between sPD P and C | No differences in mtDNA CN between sPD P and C | NR | - |

| Aliev et al. 2008 (18827923) |

NA | NA | NA | AD | Ctx, Hi, Endothelial cells |

Cytological in situ hybridization | NR | NR | 5 kb mtDNA DEL was localised in lysosomes of P but not in neuronal cell bodies. The main location of these DELs was in lysosomes, but not in other neuronal cell compartments |

DEL detection was achieved by electron microscopy ultrastructural visualisation of immune-positive gold particle clusters |

| Bender et al. 2008 (18604467) |

9/8 | 76/71 | 10/7 | AD (9) C (10) |

Pu, FCtx, SN | qPCR | NR | NR | DEL levels were higher in AD SN (32%) than in FCtx (13%) and Pu (14%) but did not differ from that of C (SN 35%, FCtx 14% and Pu 14%) | 1530 single laser-microdissected neurons were evaluated. There was no difference in mtDNA DEL levels per brain region between groups |

| Hakonen et al. 2008 (18775955) |

4/9 | 23/44 | 9/6 | IOSCA (4) C (9) (CFTR, c.1523A>G, p.Y508C) |

Ctx, Cb | Long-range PCR, qPCR, Southern blot, sequencing | IOSCA P did not show increased mtDNA point mutation load in affected tissues | mtDNA depletion was present in Ctx and Cb of IOSCA P | No mtDNA DEL was detected in IOSCA P | mtDNA CN decreased by 5–20% in brain and 10–70% in liver of IOSCA P compared to C but similar amounts were observed in skeletal muscle |

| Reeve et al. 2008 (18179904) |

6/5 | 77/78 | NA | PD (5) PEO (1) C (5) |

SN | Long-range PCR | NR | NR | Various DELs were found in P and C, there was no difference in the distribution nor in the types of DEL breakpoints detected between groups | Single laser-microdissected neurons from SN were evaluated |

| Blokhin et al. 2008a (18566918) |

5/9 | 38-53/ 34-80 |

8/6 | MS (5) C (9) |

FCtx, PCtx, OCtx | qPCR | NR | No differences in mtDNA CN between COX+ neurons, COX- neurons and neurons of chronic active plaques in MS. mtDNA CN in WM did not differ between MS P and C. In MS, mtDNA CN in neurons of GM was higher than in cells of other regions |

NR | mtDNA CN decreased with age in both MS P and C |

| Blokhin et al. 2008b (18286391) |

5/12 | 38-53/ 34-80 |

8/6 | MS (5) C (12) |

FCtx, PCtx, OCtx | qPCR | NR | NR | No pathology-related accumulation of mtDNA DELs was observed when comparing distinct brain specimens from MS or when comparing MS and C. The rate of mtDNA DELs was higher in COX- than in COX+ cells |

Proportion of mtDNA DELs correlated with age |

| Borthwick et al. 2006 (16358336) |

1/0 | 73 | M | MND (1) | FCtx, Pons, spinal cord | Sequencing, PCR-RFLP with radiolabeled nucleotides | m.4274T>C in MT-TI. Mutation load %: FCtx 45%, Pons 37%. | NR | NR | Single laser-microdissected motor neurons were evaluated. Mutation levels were significantly higher in all COX-deficient than in COX-positive motor neurons |

| Bender et al. 2006 (16604074) |

15/8+8 | 76/77 | NA | PD (15) C (8+8) |

Hi, SN | Long-range qPCR, sequencing | Nonpathogenic m.189A>G, m.16184T>C and m.9633T>C variants were detected | NR | In SN, mtDNA DEL levels did not differ between PD (52.3%) and aged C (43.3%); however, they differed in the Hi (17.8% in PD and 14.3% in C), p=0.0002. DEL levels correlated with age | 50 single laser-microdissected neurons were evaluated. The level of mtDNA DELs was significantly greater in COX-deficient neurons |

| Wang et al. 2006 (16405502) |

8/6 | 90/81 | NA | MCI (8) C (6) |

FCtx, TCtx, PCtx, Cb | GC/MS-SIMA | NR | NR | NR | Levels of multiple oxidised bases were significantly higher in FCtx, TCtx and PCtx of MCI P than in C |

| Wang et al. 2005 (15857398) |

8/8 | 85/84 | 8/8 | AD (8) C (8) |

FCtx, TCtx, PCtx, Cb | GC/MS-SIMA | NR | NR | NR | Levels of multiple oxidised bases were significantly higher in FCtx, TCtx and PCtx of AD P than in C. mtDNA had ∼10-fold higher levels of oxidised bases than nDNA |

| Aliyev et al. 2005 (15760652) |

NA | NA | NA | AD | Hi | Cytological in situ hybridization | NR | NR | 5 kb mtDNA DELs were mostly localised in lysosomal structures but not in neuronal cell bodies. There was a 3-fold increase of mtDNA DEL in AD compared to C |

DEL detection was achieved in neurons by electron microscopy ultrastructural visualization of immune-positive gold particle clusters |

| Coskun et al. 2004 (15247418) |

23/40 | NA | NA | AD (23) C (40) |

FCtx | PNA-clamped PCR, RT-qPCR, sequencing-(669 bp) | Frequency of heteroplasmic variants in the mtDNA control region showed a 63% increase in P with AD compared to C (p<0.01). In P 80 years and older this increase was 130%. m.414T>G proved to be specific for AD brains. m.146T>C, m.195T>C and m.477T>C showed heteroplasmic levels up to 70–80% in P with AD aged between 74 and 83 years |

There was a significant 50% mtDNA CN reduction in AD compared to C | NR | Paper focused on studying the mtDNA control region. Variants identified in brains of P with AD were preferentially located in known functional transcription and replication elements and were also frequently present at exceptionally high proportions. P with AD showed reduced MT-ND6 mRNA expression |

| Mawrin et al. 2004 (15036587) |

4/4 | 61/57 | 3/5 | AD (1) PD (1) FTD-MND (1) DLB (1) C (4) |

FCtx, OCtx, TCtx, Hi, SN, Cb, basal ganglia, brain stem | qPCR | NR | NR | In FTD-MND, high levels of the common DEL were found in the brain stem, FCtx and TCtx. In DLB, they were observed in OCtx. In PD and AD, no increase of the common DEL was observed. In PD, high levels of common DEL were observed in SN after normalisation for the mtDNA deletion in Cb. The lowest levels of the common DEL were found in the Cb |

Levels of the common DEL were markedly raised with increasing age |

| Mawrin et al. 2003 (12924443) |

7/3 | NA | NA | ALS (7) C (3) |

Ctx, brain stem | PCR | NR | NR | Common DEL levels did not differ between ALS and C. Common DEL levels increased with age |

Single laser-microdissected neurons were evaluated |

| Aliev et al. 2003 (14503022) |

NA | 57-93/54-85 | NA | AD | Hi, TCtx, Cb, FCtx | In situ hybridization | NR | NR | mtDNA DEL showed a 3-fold increase in AD compared to C. The majority of these DELs were found in mitochondria-derived lysosomes |

DEL detection was achieved by electron microscopy ultrastructural visualisation of immune-positive gold particle clusters |

| Gu et al. 2002 (12125742) |

24/4 | 77/81 | 17/11 | PD (8) AD (6) DLB (6) MSA (4) C (4) |

SN, Ctx, Hi, Cb (in 5 PD) Hi (in 5 AD) |

Long-range PCR + FIGE Southern blot |

NR | NR | The number of mtDNA DEL/rearrangements in SN of P with PD was significantly higher than that in other groups. In PD, the number of mtDNA DEL/rearrangements did not differ between the other brain regions studied. No significant increase was observed in the total number of DEL/rearrangements in the Hi of AD P |

The average number of rearranged forms in patients with PD, AD, MSA, DLB and C was 10.8, 5.7, 4.8, 4.8 and 6.0, respectively |

| Zhang et al. 2002 (12039426) |

26/21 | NA | NA | PD (7) MSP-A (4) PSP (4) DLB (4) AD (7) C (21) | SN, other midbrain regions | ISH | NR | NR | Common DEL accumulated in neurons but not glia in both the SN and other midbrain regions with no differences between P and age-matched controls | - |

| Simon et al. 2001 (11352572) |

38/44 | NA | NA | AD (8) PD (27) MSA (4) C (44) |

Ctx, FCtx, OCtx, TCtx, PCtx | PCR-RFLP, sequencing | No presence of the m.414T>G variant. mtDNA variants reported in AD: m.267T>C, m.347G>A, m.380G>A, m.405T>C, m.416T>C, m.436C>T, m.456C>T, m.511C>T, m.523delAC, m.555A>G, m.566C>T and m.644A>G |

NR | NR | No further investigation in the pathogenicity of these mutations was made |

| de la Monte et al. 2000 (10950123) |

37/25 | 76/78 | NA | AD (37) C (25) |

TCtx | PCR with radiolabeled nucleotides | NR | mtDNA CN levels were significantly lower in AD P than in C although several AD cases showed high levels of mtDNA CN | NR | - |

| Chang et al. 2000 (10873587) |

20/20 | 82/71 | NA | AD (20) C (20) |

PCtx, Hi, Cb | PCR with radiolabeled nucleotides, PCR-RFLP | Point mutation frequencies were 2 to 3-fold higher in PCtx, Hi and Cb of AD P than in C. Point mutation frequencies did not differ between brain regions |

NR | Common DEL levels of AD did not differ from the C. Common DEL frequency was 15 to 25-fold lower in Cb than Ctx in both AD and C |

In blood, point mutation frequencies were not elevated in AD. No correlation was found between age and common DEL frequency in AD and C |

| Dhaliwal et al. 2000 (10943712) |

6/4 | 72/83 | NA | ALS (6) C (4) |

FCtx, TCx | PCR | NR | NR | Common DEL levels were higher in FCtx than in TCtx in both ALS and C. The relative difference in the two brain regions was >11-fold higher in ALS than in C | In ALS, there was no correlation between duration of disease and common DEL levels in the two brain regions |

| Ito et al. 1999 (10051601) |

1/NA | 81/NA | 1M/NA | AD (1) | SN, GP | PCR | NR | NR | The common DEL was detected in SN and GP | Percentage load of the m.3243A>G, MT-TL1 was 0.04% and 0.05% in cybrids obtained from SN and GP, respectively. m.3243A>G, MT-TL1 and the common DEL was not detected in blood |

| Hatanpaa et al. 1998 (9729244) |

5/4 | 83/72 | 2M/2M | AD (5) C (4) |

Motor Ctx, midtemporal Ctx | Northern blot | NR | NR | NR | COXIII mRNA expression was lower in midtemporal Ctx of AD P than in C |

| Haferkamp et al. 1998 (9561330) |

2/0 | 54/0 | 0/2 | Disseminated neocortical and subcortical encephalopathy | Brain stem | PCR | Both patients revealed the same homoplasmic variants at positions m.13708G>A and m.15257G>A. Patient 2 also carried an homoplasmic variant at position m.15812G>A | NR | NR | - |

| Ozawa et al. 1997 (9196054) |

1/1 | 65/65 | 1F/1F | PD (1) ALS (1) |

Str | PCR | NR | NR | Presence of 134 DEL in the P with PD and 98 DEL in the P with ALS | The ALS patient was considered a C individual in this study |

| Hamblet & Castora. 1997 (9357554) |

9/9 | 68/66 | NA | AD (9) C (9) |

TCtx | PCR Southern blot |

NR | NR | Mean % of the Common DEL in AD P and C was 0.059 and 0.009, respectively, a 6.5-fold significant change | - |

| Kösel et al. 1997 (9380043) |

4/4 | 74/73 | 7/1 | PD (4) C (4) |

SN, Ctx, CbCtx, Pu, Cb | PCR, PCR-RFLP | m.4336A>G homoplasmic in 1PD. m.5460G>A heteroplasmic (95% mutation load) in 1C |

NR | DEL levels in CbCtx were 50 to 200-fold lower compared to SN, and 12 to 23-fold greater in Pu than in Cb | - |

| Hutchin et al. 1997 (9425253) |

65/76 | 76/71 | NA | AD (65) C (76) |

NA | PCR-RFLP | Frequencies of the analysed variants: m.3196G>A, m.3397A>G and m.8021A>G were not detected in P or in C, m.4336A>G was only present in 1.7% of the C, m.5460G>A was present in 3.1% of P and 2.6% of C, m.5705T>C was present in 1.5% of AD P but not in C |

NR | NR | - |

| Janetzky et al. 1996 (8738945) |

48/19 | 75/71 | NA | AD (48) C (19) |

FCtx, Ent, Hi | Nested, allele-specific PCR, sequencing |

m.5460G>A, p.Ala331Thr, MT-ND2 was present in 6 AD cases (4 homo- and 2 heteroplasmic, with a mutation load of 5%). Not present in C |

NR | NR | - |

| Schnopp et al. 1996 (8937782) |

2/2 | NA | NA | PD (2) C (2) |

FCtx, PCtx, TCtx, OcCtx, Hi, Pu, Th, Cd, CbCtx, CC, SN, among others | PCR-RFLP | Ratios of the m.5460G>A, varied between 44% and 98% in the brain regions studied. No differences were observed when comparing WM and GM, or between PD P and C | NR | NR | - |

| Kösel et al. 1996 (8723226) |

21/77 | 74/72 | 45/53 | PD (21) C (77) |

SN, Ctx, Cb, Pu | PCR-RFLP | m.5460G>A heteroplasmic variant was found in 4/21 PD P and in 5/77 C. m.4336A>G homoplasmic variant was present in 1 PD P |

NR | NR | - |

| Chen et al. 1995 (7599213) |

3/3 | 27-42/ 27-42 |

3/3 | HD (3) C (3) |

Pu, OCtx, Cd | Competitive PCR | NR | NR | Similar levels of the common DEL in the three regions when comparing HD P and C. Lower levels of the common DEL in Pu and OCtx |

- |

| Cavelier et al. 1995 (8530074) |

33/9 | 80/72 | 20/22 | AD (33) C (9) |

FG, Cd, FCtx, OCtx, PCtx | Competitive PCR | NR | NR | Similar % of the common DEL in AD P (0.01–2.9) and C (0.003–2.0). Levels of the common DEL were higher in Cd than in FG |

No correlation between COX activity and the common DEL levels |

| Mecocci et al. 1994 (7979220) |

13/12 | 71/75 | 15/10 | AD (13) C (12) |

FCtx, TCtx, PCtx, Cb | PCR | NR | NR | NR | The amount of oxidised mtDNA showed a threefold increase in PCtx of AD P vs. C |

| Reichmann et al. 1993 (8393094) |

7/7 | 77/77 | 8/6 | AD (7) C (7) |

PCtx, Ent | PCR | NR | NR | DELs larger than 500 bp were discarded | - |

| DiDonato et al. 1993 (8232940) |

1/1 | 72/62 | 1M/1M | PD (1) C (1) |

SN, Hi, OCtx, Th, FCtx, Pu, GP, CbCtx, R, LC | qPCR | NR | NR | The SN showed the highest proportion of the common DEL (3.16%), while CbCtx showed the lowest (0.02%) | - |

| Blanchard et al. 1993 (8347829) |

6/6 | 80/64 | 7/5 | AD (6) C (6) |

FCtx | PCR | NR | NR | Similar mtDNA DEL levels were observed in AD (0.14%) and C (0.12%) | - |

| Lestienne et al. 1991 (2013767) |

1/1 | NA | NA | PD (1) C (1) |

Pu, SN, Ctx | PCR | NR | NR | The common DEL was present in PD P and in C | - |

| Lestienne et al. 1990 (2120389) |

15/5 | 60–85/NA | NA | PD (15) C (5) |

Pu. SN, FCtx | Southern blot | NR | NR | No DELs were identified | - |

| Schapira et al. 1990 (1979656) |

6/6 | NA | NA | PD (6) C (6) |

SN | RFLP Hybridization using a radiolabeled probe | NR | NR | No DELs were identified | - |

| Ikebe et al. 1990 (2390073) |

5/6 | 68/55 | 6/5 | PD (5) C (6) |

FCtx, Str | PCR | NR | NR | Proportion of deleted mtDNA to normal mtDNA was lower in FCtx than in the Str of both PD and C | - |

C: control; DEL: deletion; F: female; GM: gray matter; M: male; mtDNA CN: mitochondrial DNA copy number; N: number of subjects; NA: information not available; NR: not reported; P: patient; TH: tyrosine hydroxylase; y: years; WM: white matter.

AD: Alzheimer's disease; ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CJD: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease; DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies; DS: Down's syndrome; DSAD: Down's syndrome and dementia; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; HD: Huntington disease; HpC: high-pathology control subjects, individuals who meet criteria for high AD neuropathologic changes but remain cognitively normal; IOSCA: infantile onset spinocerebelar ataxia; IPD: idiopathic Parkinson's disease; LB: Lewy bodies; MCI: mild-cognitively impaired; MD: mitochondrial disease; MND: motor neuron disease; MS: multiple sclerosis; MSA: multiple system atrophy; MSA-P: MSA-parkinsonian type; MTLE-HS: mesial temporal lobe epilepsy-hippocampal sclerosis; NCI: noncognitively impaired controls; NFT: neurofibrillary tangles; PD: Parkinson's disease; PDD: PD with dementia; sPD: sporadic PD; PEO: progressive external ophthalmoplegia; PSP: progressive supranuclear palsy.

Cb: cerebellum; CbCtx: cerebellar cortex; CC: corpus callosum; Cd: caudate nucleus; Ctx: cortex; Ent: entorhinal cortex; FCtx: frontal cortex; FG: frontal gyrus; GP: globus pallidus; Hi: hippocampus; IO: inferior olive; LC: locus coeruleus; PCtx: parietal cortex; PFCtx: prefrontal cortex; PPN: pedunculopontine nucleus; SN: substantia nigra; SNC: substantia nigra pars compacta; OCtx: occipital cortex; Pu: putamen; R: red nucleus; Str: striatum; TCtx: temporal cortex; Th: thalamus; Ver: vermis of cerebellum.

ddPCR: digital-droppled PCR; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FIGE: field inversion gel electrophoresis; GC/MS-SIMA: gas chromatography/mass spectrometry with selective ion monitoring analysis; NGS: next-generation sequencing; PQ: pyrosequencing; qPCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; RMC: random mutation capture; RFLP: restriction fragment length polymorphism; RT-qPCR: reverse transcription qPCR.

COX: cytochrome c oxidase; D-loop: displacement loop; MT-: mitochondrially encoded gene; ND2: NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 2; TL1: tRNA-Leu 1.

Table 3.

Studies reporting the results of mtDNA analyses in postmortem brain samples of patients with psychiatric diseases (PsyD).

| Study reference (PMID) |

Patient/Control characteristics | Disease (N) |

Brain region | Technique | mtDNA alteration in brain | Additional information | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N P/C |

Age (y) in P/C |

Sex M/F |

Variant | mtDNA CN | Rearrangements | |||||

| Fries et al. 2019 (31746071) |

32/32 | 45/47 | P: 15/17 C: 19/13 |

BD (32) | Hi | qPCR | NR | Less mtDNA CN in BD P vs. C. Significant correlations between telomere length and mtDNA CN |

NR | mtDNA CN was not correlated with chronological age |

| Hjelm et al. 2019 (30869147) |

39/2 | 46 | 33/8 | SZ (12) BD (10) MDD (9) ADO (8) C (2) |

ACCtx, DLPFCtx, Hi, Pu, Cd |

Long-range PCR and NGS, exome sequencing, splice-break pipeline, qPCR, Sanger sequencing |

NR | NR | The study identified 4489 DELs: 513 with size range 7–8 kb and 127 with size of approximately 50 bp; 346 unique; 12 out of the 30 most frequent DELs were previously described. 13 high-impact DELs (read rate ≥ 5%) were present in 14 brain tissue samples of 9 subjects with psychiatric diagnoses. The group of subjects with SZ or BD had a higher DLPFCtx/ACCtx DEL ratio than the group of C, MDD or ADO subjects. The highest DEL burdens occurred in two subjects with MDD. The common DEL was neither the most frequent nor the most abundant |

Brain samples contained significantly more DELs and higher cumulative read percentages than blood samples. The 13 high-impact DELs detected in the brain were not detected in the blood. Many individual DELs had significant positive correlations with age The highest DEL burdens were observed in MDD P, at higher levels than KKS muscle |

| Bodenstein et al. 2019 (31797868) |

66/37 | Hi C: 60 BD: 59 SZ: 62 BA24 and Cb C: 71 BD: 72 SZ:69 PFCtx C: 72 BD: 65 SZ: 71 |

NA | SZ (35) BD (31) C (37) |

Hi, BA24, Cb, PFCtx | qPCR | NR | BD group had significantly higher mtDNA content for MT- ND4 and MT-ND5 in Hi tissue compared to C. Cb of patients with BD or SZ also had higher mtDNA CN than BA24 region of the same patients | No significant alteration in the accumulation of the common mtDNA DEL across the brain regions and groups | BA24 and Cb tissues came from the same patients |

| Otsuka et al. 2017 (28600518) |

20/25 | SV: 52 C: 58 |

SV:11/9 C: 19/6 |

SV (20) C (25) |

DLPFCtx | qPCR | NR | Significantly lower mtDNA CN in the DLPFC of SV compared to C (p = 0.0044) | NR | In the DLPFCtx of SV, significantly shorter telomere length was reported (p = 0.0014) |

| Rollins et al. 2018 (29594135) |

53/41 | BD: 46 SZ: 41 C: 58 |

BD: 13/13 SZ: 24/3 C: 35/6 |

BD (26) SZ (27) C (41) |

PFCtx | qPCR with SYBR green and TaqMan probes | NR | BD and SZ groups displayed a significant increase in mtDNA CN (p= 0.028 and p= 0.025, respectively) | No significant decrease in mtDNA common DEL in PFCtx of patients with SZ. Female subjects displayed 60% increase in the accumulation of the common DEL |

Complex I ELISA data indicated that the brains of SZ and BD had fewer functional mitochondria with larger amounts of mtDNA compared to controls |

| Mamdani et al. 2014 (25270547) |

30/10 | MDD: 48 BD: 52 SZ: 47 C: 46 |

MDD: 3/7 BD: 5/5 SZ: 5/5 C: 7/3 |

MDD (10) BD (10) SZ (10) C (10) |

ACCtx, Amg, Cd, DLPFCtx, Hi, Ac, OFCtx, Pu, SN, and Th | qPCR, Sanger sequencing | NR | NR | Common DELs in SZ were significantly decreased, mostly in dopaminergic regions, compared to MDD, BD and C. | Possible impacts of antipsychotic and antidepressant medications were not quantified. |

| Torrell et al. 2013 (23355257) |

45/15 | SZ: 45 BD: 43 MDD: 47 C: 48 |

SZ: 9/6 BD: 9/6 MDD: 9/6 C: 9/6 |

SZ (15) BD (15) MDD (15) C (15) |

OCtx | qPCR | NR | No differences in mtDNA CN were observed between study groups | NR | MT-ND1 gene expression was increased in BD P vs. C |

| Gu et al. 2013 (24002085) |

14/12 | ASD: 11 C: 11 |

ASD: 11/3 C: 9/3 |

ASD (14) C(12) |

FCtx | RT-PCR | NR | A significant increase of mtDNA CN in ASD subjects compared with C. | MT-ND4 deletion was found in 44% of the ASD group, and 33% of them also had Cyt B deletion. | |

| Tang et al. 2013 (23333625) |

20/25 | ASD: 2–67 C: 2–60 |

ASD: 18/3 C: 22/2 |

ASD (20) C (25) |

TL | MitoChip assay, qPCR | m.7064T>C, Phe387, MT-CO1 | No changes in mtDNA CN (studied in 8 ASD P and 8 C) | No presence of large-scale DELs or duplications. | |

| Sequeira et al. 2012 (22723804) |

3 cohorts Co 1: 4/7 Co 2: 29/6 Co 3: 6/17 |

Co 1: SZ: 53 C: 57 Co 2: SZ: 44 BD: 50 MDD: 51 C: 53 Co 3: SZ: 41 BD: 57 MDD: 41 C: 52 |

Co 1: SZ: 2/3 C: 2/4 Co 2: SZ: 11/3 BD: 9/3 MDD: 11/4 C: 60/16 Co 3: SZ: 2/2 BD: 3/1 MDD: 4/1 C: 16/7 |

Co 1: SZ (5) C (6) Co 2: SZ (14) BD (11) MDD (15) C (76) Co 3: SZ (4) BD (4) MDD (5) C (10) |

Co 1: ACCtx, Amg, Cd, DLPFCtx, Ac, OFCtx, Pu, SN, Th Co 2: DLPFCtx Co 3: DLPFCtx |

NGS, Affymetrix 6.0 SNP chip, qPCR |

149 homoplasmic novel or rare variants: 7 not previously reported (5 synonymous variants, 1 in the D-loop, 1 in a tRNA). 88% transitions and 11% transversions. Higher number of transitions and transversions in MDD vs. C and vs. SZ or BD. The m.195T>C, MT-HV2 and m.16519T>C, D-Loop were underrepresented in pooled SZ and BD vs. C. |

NR | In the DLPFCtx, the common DEL levels were significantly increased in P with BD, marginally increased in P with MDD and not increased in P with SZ vs. C. Higher levels of the common DEL in SN and Cd. The common DEL levels were correlated with age |

Certain brain regions accumulated somatic mutations at higher levels than the blood. |

| Ichikawa et al. 2012 (22030097) |

28 | 63.1 | 20/8 | SZ | FCtx | Sanger sequencing, allele-specific PCR | Homoplasmic substitutions m.8881T>C and m.9699 A>G were detected exclusively in SZ patients. Unregistered m.6617 C>T and m.9500 C>T substitutions with 50% heteroplasmy were found in a brain sample from a single patient. m.9956 A>G was also found as a homoplasmic variant in a brain sample of an SZ patient, while it was heteroplasmic in controls. | NR | NR | m.7196C>A was detected in SZ patients' brain tissue in both a homoplasmic and heteroplasmic state; it was also detected in blood samples of SZ patients and in blood samples of controls as a homoplasmic variant. |

| Rollins et al. 2009 (19290059) |

41/36 | BD: 50 SZ:45 MDD: 51 C: 53 |

SZ: 11/3 BD: 9/3 MDD: 11/4 C: 31/5 |

SZ (14) BD (12) MDD (15) C (36) |

DLPFCtx | Affymetrix mtDNA resequencing array, SNaPshot and allele-specific RT- PCR |

The rate of synonymous base pair substitutions in the coding regions of the mtDNA was 22% higher in P with SZ vs. C. One MDD P carried a homoplasmic mutation in DLPFC at m.10652T>C, Ile61, MT-ND4L, and two P with SZ showed less than 1% heteroplasmy. Low levels of heteroplasmic nonsynonymous mutations were found in the brain. Several mtDNA variants were significantly associated with specific psychiatric disorders: m.114T>C, m.195C>T, m.10652T>C and m.16300G>A with BD; m.750A>G, 1438A>G and 4769A>G with SZ; and 10652C>T, 14668T>C and 15043A>G with MDD. |