Abstract

The Indonesian government has made a policy requiring parents and children to work and study from home (WFH) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this policy was meant to limit the spread of the virus and its effects, it has caused psychological trauma, increased stress on parents, and raised child abuse. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the issue of child abuse during online learning, its underlying factors, and its implications on children's mental health. A descriptive qualitative method was used along with a survey technique utilizing Google Forms, involving 317 parents as respondents. The results showed that there was physical, emotional, and verbal child abuse and negligence during online learning. This happened because children were often assumed of neglecting studies and misusing gadgets. Furthermore, the stress levels in parents increased due to the dual role, i.e, working and being teachers at home.

Keywords: COVID-19, Child abuse, Early childhood, Online learning

COVID-19; Child abuse; Early childhood; Online learning.

1. Introduction

The entire world is fighting the transmission of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by Sars-CoV-2. Consequently, the whole community experiences trauma due to unpreparedness, incomplete health care system, and lockdown policy in dealing with the virus spread (Abdullah, 2020; Shammi et al., 2020). This negatively affects the economic, environmental, and social development and growth, as well as education system. The current policy requires everyone to work from home and even children to study from home. This new rule inevitably brings about a significant impact on parents and children. In addition to working from home, parents also assume additional responsibilities and duties to teach children at home. During the current pandemic, unemployed parents or those who have to work from home experience increased pressure in their businesses along with the task of guiding children to learn (Munastiwi and Puryono, 2021).

Indonesia closed all schools from early March 2020 resulted in around 60 million students studying at home. Schools were asked to facilitate learning from home using either government or private digital platforms that provide free content and online learning opportunities across regions (UNICEF, 2020). Cindy Vallely, the Executive Director of the Children Advocacy Center in Florida, was concerned about school closures due to the COVID-19 outbreak. She asserted that schools, in many cases, have become shelters for children, and their closures mean that their protective structure has more or less reduced (Vallely, 2020). These conditions give rise to many new conflicts, including increased domestic violence to spouses and children at home. Parents lose their source of income, worry about paying their bills, and many cannot manage their mentality. Consequently, they vent this anxiety by committing child abuse (Rosalin, 2020). Therefore, data show that stress and poverty are some triggering factors of child abuse and neglect (Jonson-Reid et al., 2020).

The pressure caused by the COVID-19 pandemic increases parents’ burden and stress level which results in verbal and physical child abuse. Pinching, threatening, and loud screaming at children are forms of child abuse committed unconsciously by parents when they cannot hold their emotions (Hadiwidjojo, 2020). Since its first outbreak in China between late 2019 and early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic profoundly affected the entire community lives and habits. The most affected countries, unavoidably face health crisis causing a long-term impact on their economic and social structure. Furthermore, there is a policy to enforce social restrictions, such as changing face-to-face learning at school environment to distance, home basis online learning (Favale et al., 2020). Thus, this pandemic obviously requires more space and time to interact in virtual learning conducted remotely (Chiodini, 2020).

Child abuse cases in Indonesia increased significantly in three weeks from March 12 to April 2, 2020. According to Leny Nurhayati Rosalin, Deputy for Child Development at the Ministry of Women's Empowerment and Child Protection, in a webinar entitled "The New Face of Early Childhood Education Programs in Indonesia Post-COVID-19 Pandemic: School and Family Synergy" organized by UHAMKA PGPAUD, held in Jakarta, Saturday, May 16, 2020, a total of 368 abuses were experienced by 407 children. Furthermore, she stated that many parents were not ready with the conditions to work and stay at home. Moreover, equal relations within family had not been established, and parents were not adequately prepared to be good caregivers (Kemenpppa, 2020).

Boserup et al. (2020) examined the alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that work-from-home policies and school closures increased child abuse cases in the household. According to the US Police Department, there was an increase in domestic violence in Portland by 22%, San Antonio by 18%, Jefferson County, Alabama by 27%, and New York City by 10% (Boserup et al., 2020). Research by Ghosh et al. (2020) maintains that children studying online are vulnerable of becoming violence victims in cyberspace. Lack of parental supervision during online learning may also lead them to suffer from mental and psycho-social disorders (harassment/bullying) (Ghosh et al., 2020). Furthermore, Nurfauziah et al. (2020) asserted that ineffective online learning and piled up school assignments produce stressful and bored children, and are even vulnerable to cyber-bullying crimes (Nurfauziah et al., 2020).

In Indonesia, an elementary school student, named LF, ran away from home. This 11-year-old and 5th-grade student ran away after being scolded by their mother for spending internet data on online assignments (Baihaqi, 2020). Elsewhere, a 14-year-old student from Kerala, India, reportedly committed suicide because she could not attend online classes due to the absence of smartphone or TV (Ramadhanty, 2020).

These cases show the prevalence of child abuse as a result of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study, nonetheless, examines broader factors regarding the relationship between online learning and child abuse. These factors could be the teachers, parents, or children's lack of knowledge about the online learning system which then trigger conflicts or it could also be caused by network and internet connection or even devices unavailability.

This study determines the relation of online learning on potential child abuse during work (WFH) and school from home (SFH) due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia.

1.1. Online learning during COVID-19 pandemic

Many schools worldwide are reducing access for direct interaction between students and teachers, forcing them to adopt technology for education survival (Kingsbury, 2021). Technology is essential in teaching and learning process particularly in the era of the industrial revolution 4.0. It motivates students and promotes efficient and productive interaction (Thorne, 2007). Moreover, online learning facilitates students to obtain quick and broad access to resources (Pannekoek, 2008) using internet networks. It supports students in having flexible learning schedules and interacting with teachers using mobile applications, such as video conference, telephone or live chat, zoom, or WhatsApp group.

The online learning system is conducted virtually using the internet. The teaching and learning process is carried out using devices such as mobile phone, personal computer or laptop connected to internet network while students and teachers are at home. Teachers are expected to create simultaneous learning using groups on social media, such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram, or Zoom (Harnani, 2020).

Online learning is the process of implementing education using the internet (Kim, 2020). It is conducted remotely to enable children to access education from distance as well as a solution offered when they cannot attend school class. Online learning can also be defined as a process of employing network connected digital media, which can be arranged anywhere, anytime and under any circumstances in order to achieve educational goals (Dhawan, 2020). This has been a significant development in education, in which teachers and students do not need to interact directly face to face within school environment. This also helps education survival easier today during the pandemic (Marek et al., 2021). Therefore, parents, to a certain extent, do not need to worry about the constraints of the pandemic as online learning has been one of the solutions to today's educational problems.

Commonly, online learning in Indonesia uses electronic media, such as laptops, televisions, and smartphones via WhatsApp, zoom, or google meet. Teachers invite parents to join social media groups, such as WhatsApp, to deliver the learning materials. Furthermore, video calls are made using WhatsApp, Zoom, Google Meet, or other applications for virtual face-to-face meetings (Suhendro, 2020). As the pandemic began to slow down, offline learning was partly implemented following health protocols, yet the online learning still dominantly took place to prevent the virus from spreading in schools.

During the online learning, children should not be allowed to carry out the process without any assistance from parents since they still lack of knowledge of devices management and utilization, thus, parents' role is needed. Besides, assignments given by the teachers cannot be understood directly by the children. Therefore, parents are expected to provide instructions for children in completing assignments. Although parents have been charged with their own work and tasks, children still need their attention during this pandemic (Novianti and Garzia, 2020). This is because their socialization and direct interaction with their friends and the surrounding community is considerably limited. Therefore, parents' assistance and attention to their children's home-basis education is urgent to maintain their development and growth despite the space and social limitation.

On the other hand, teachers are also expected to improve innovation and creativity to help overcome the limitations of online learning (Limbers, 2020). Early childhood education teachers are anticipated to actively collaborate with parents to improve online learning methods that suit the children's development and growth needs. To some extent, online learning actually enhances innovative teaching and learning, where teachers and parents may discuss the best facilities which can be provided for children's education at home (Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021). Therefore, teachers and parents need to grasp comprehensive understanding on the fundamental concept of online learning activities to ensure optimal implementation of the process as well as optimal students' achievement.

Online learning is divided into Exploration, Elaboration, and Confirmation. Exploration facilitates children's learning process from not knowing to knowing. In exploration activities, parents and teachers involve children in finding and collecting information. They help children to enrich and manage information through the internet, facilitate and motivate their active participation, and encourage them to observe various indications. Meanwhile, elaboration activities promote children to work on assignments by describing their exploration results, deepening knowledge, concluding together, and presenting learning outcomes. In confirmation activities, teachers and parents provide feedback on the results of the children learning experience and give appreciation to strengthen them (Daryanto and Dwicahyono, 2014).

1.2. Child abuse

Depression, worry, negative emotions, and adults’ anxiety towards children are some of the risk factors of violence against children (Sakakihara et al., 2019). Child abuse is an act of harming children physically, psychologically, or socially. This could involve physical harm, verbal expressions, bullying, anger, discrimination, harassment, neglect, unloving act, or reduced attention (NSPCC, 2020). Child abuse affects their psychological, somatic, and social well-being and their development into adulthood. Various negative psychological and emotional consequences obtained by the victims will lead them to become a deviant adult having bad behaviour and committing the same abuse (Rerkswattavorn and Chanprasertpinyo, 2019). According to Newberger, child abuse is divided into Physical, Emotional, and Verbal and Neglect (Newberger, 1994).

Child physical abuse is a form of harsh treatment of a person against a child's body by punching, biting, burning, poisoning, strangling, slapping, or kicking. It causes diverse effects, such as bruises, fractures, injuries, and wounds (Mathews et al., 2020). The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines child physical abuse as the intentional use of physical force against children, resulting in or potentially causing physical injury (Mogaddam et al., 2016). Furthermore, children may suffer from permanent physical and mental harm. The victims are at risk of developing various problems, such as behavioural disorders, aggressiveness, depression, poor academics, sluggish performance, or decreased cognitive function (Christian, 2015).

Emotional abuse is an invisible non-physical treatment yet directly affects the inside feeling of the children. Child emotional abuse harms the children's mentality and impacts their emotional development (Kimber et al., 2019). This act involves belittling, blaming, threatening, frightening, discriminating, mocking, vilifying, and other forms of non-physical rejection (Norman et al., 2012). Additionally, emotional abuse refers to failing to educate children by not providing appropriate and supportive environment including actions that harm their health and emotional development (Subedi et al., 2020). Child emotional abuse harms behavioural, social, and physiological functioning, leaving lifelong scars in the children's lives.

Child verbal abuse is a harsh treatment using unpleasant words, such as insulting, scolding, shouting, or yelling (Schneider et al., 2020). This includes belittling and demeaning children with unpleasant intonation and embarrassing words (Coates et al., 2013), and harming their emotional and language development. Symptoms of separation anxiety, disturbed mood, forming and maintaining relationships difficulty, guilty feeling, distress, and self-destructive behaviour are common in verbally abused children (Ney, 1987).

Neglect is one type of child abuse leading to various consequences on their development. Although this type of treatment exists in every social class, and not all poor parents neglect their children, in fact, poverty is one of the risk factors (Pasian et al., 2020). Child neglect occurs because of poor supervision, inadequate and unavailable food, de-schooling, and lack of needed medical attention (Mulder et al., 2018).

2. Method

This study focused on abuses committed by parents accompanying their children's learning at home while working from home. Stress occurred because of increasing demands on office work and difficulties in accompanying children's learning. These factors have triggered child physical, verbal, and emotional abuse, as well as neglect.

Primary data were collected through interviews and questionnaires distributed to parents, while secondary data were sourced from online media. The data needed were difficulties experienced by parents and children during the pandemic, and child abuse committed by parents.

A total of 317 respondents spread across several cities in Indonesia participated in this study. They comprise of parents openly selected based on the ownership of children aged 3–12 years and their ability to fill out a questionnaire distributed through Google Forms. Based on their experience assisting children in online learning, they were expected to provide the information needed. Respondents data comes from various regions in Indonesia, Information can be seen in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Respondent distribution.

| No | Original City of Respondents | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Yogyakarta | 164 |

| 2. | Jakarta | 6 |

| 3. | South Sumatera | 42 |

| 4. | West Java | 13 |

| 5. | Central Java | 43 |

| 6. | East Java | 39 |

| 7. | Riau | 2 |

| 8. | Lampung | 1 |

| 9. | South Kalimantan | 1 |

| 10. | West Kalimantan | 1 |

| 11. | Central Sulawesi | 1 |

| 12. | Gorontalo | 2 |

| 13. | North Sumatera | 2 |

| 317 |

Data collection started with desk review from secondary sources through online news on child abuse and neglect during the pandemic. Furthermore, information on parents' experience of accompanying children to study at home and data on child abuse was collected through questionnaires distributed via google forms on WhatsApp groups, Facebook, Instagram networks of colleagues, family, neighbors, and teacher groups. Google form was used due to social restrictions (lockdown policy), making it impossible to walk around in the field. To complete the survey data obtained, the parents and children were interviewed by chatting or recording voice notes on WhatsApp.

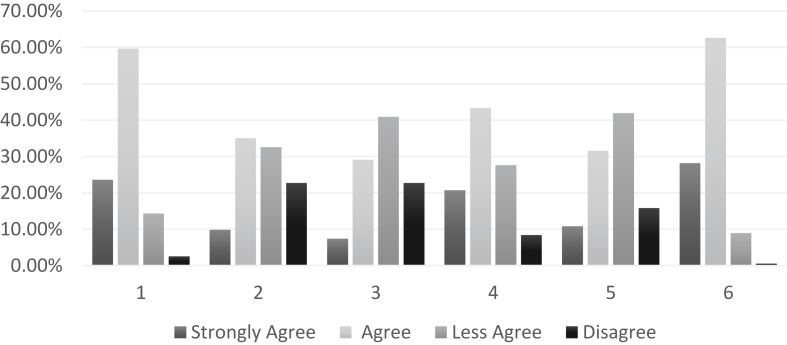

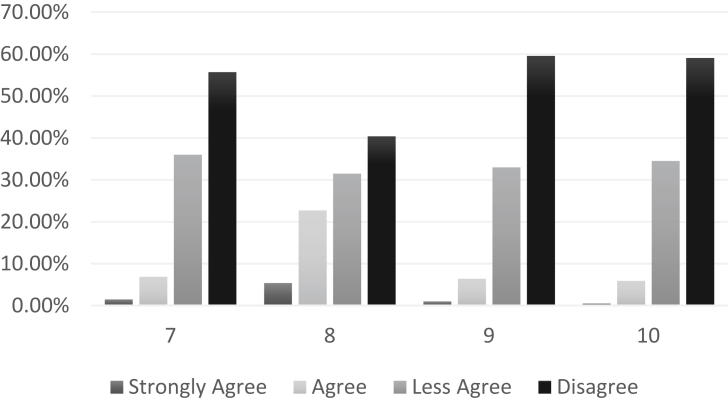

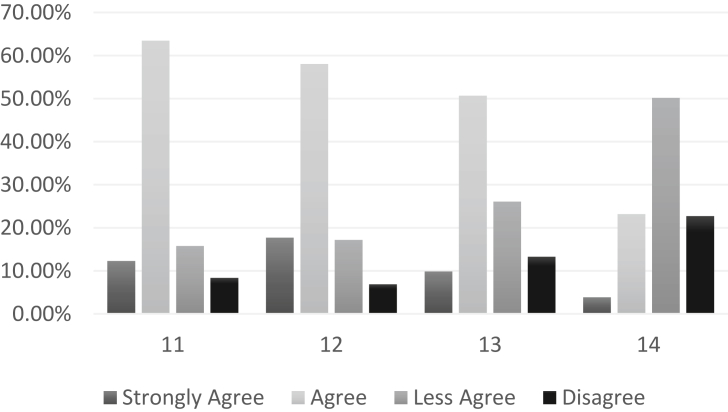

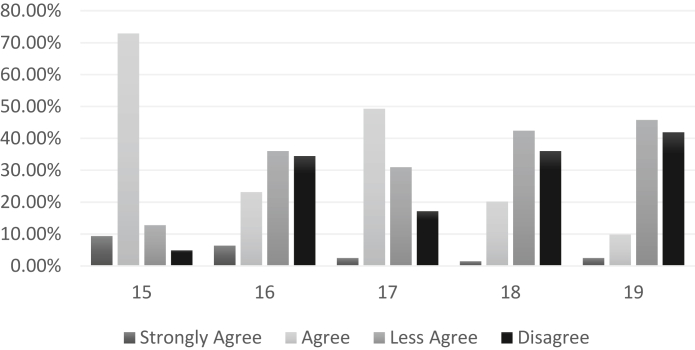

The data were then analyzed following the Miles and Huberman (2020) stages, including reduction, display, and verification. The questionnaire results are presented in a bar graph (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, and Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7). Furthermore, classified data were analyzed by interpretation method. Figure 1 presents the parents' experience of accompanying their children in online learning. Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 show child abuse experience, while Table 2 displays the factors causing child abuse.

Figure 1.

Graphics about statements on online learning. Parents' responses to the online learning process are 1) During the pandemic, parents accompanied their children in online learning at home, 2) Parents and their children have difficulty using online learning media (Smartphone/Laptop/Computer) while studying from home, 3) Parents have difficulty finding information on the internet about their children's school's daily assignments, 4) The internet network or quota at home is fulfilled during online learning, 5) The assignments given by the teacher are too heavy for the children, 6) Parents always appreciate every child that succeeds in online learning.

Figure 2.

Graphics about statements of child physical abuse. Parents’ responses to child physical abuse are 7) Parents punish (pinching) their children when they neglect or refuse to conduct online assignments, 8) Parents punish (pinching) their children if they use gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) too long, 9) Parents have once forcibly taken (seized) the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) when the study time was over, 10) Parents have once hit their children as they failed to obey the rules of studying or they refused to learn.

Figure 3.

Graphics about statements of child emotional abuse. Child Emotional Abuse contains statements of 11) Parents have been angry if their children use gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) to play games, instead of completing online learning, 12) Parents were forced to take the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) when it exceeded the learning time limit, 13) Parents threatened their children not to give them the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) anymore if they still violate the rules, 14) Parents have once had to shout to their children when they refused to learn.

Figure 4.

Graphics about statements of child verbal abuse. Statements of Child Verbal Abuse are 15) Parents criticized their children if they misused the internet not for online learning, 16) Parents strengthened their children to be enthusiastic about learning by comparing them with their colleagues, 17) Parents told their children to stop crying when they refused to follow the rules, 18) Parents accused their children of using the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) too often that they forgot about their assignments, 19) Parents called their children lazy once they failed to complete the assignment.

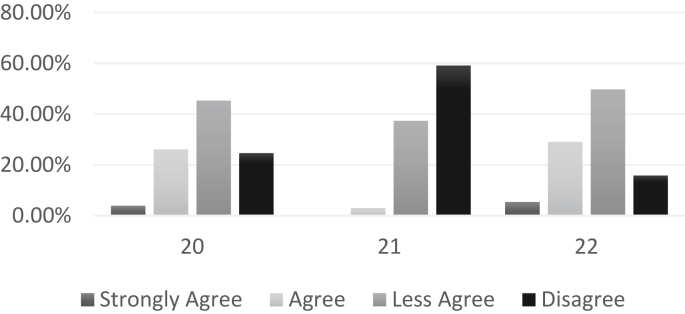

Figure 5.

Graphics about statements of child neglect. Statements of Child Neglect are 20) Parents allowed their children to insist on using the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop), although they had passed the study time limit, 21) Parents allowed their children to use the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) for a long time, provided they did not cry, 22) Parents left my children to complete their assignments on their own when they were busy at work.

Table 2.

Parent's response to online learning.

| Aspect | Question | Parents' response | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploration | During the pandemic, I accompanied children in online learning at home | Most parents accompany their children in online learning during work from home (WFH) and school from home (SFH) | 59.6% of parents agree to accompany their children to study, and 2.5% disagree |

| My children and I have difficulty using online learning media (Smartphone/Laptop) while studying from home. | Most parents have difficulty using media during online learning. | 35% of parents agree they have difficulty using learning media during online learning, while 22.7% disagree | |

| I have difficulty finding information on the internet about my children's school's daily assignments | Most parents have no difficulty finding information about their children's school assignments through the internet. | 40.9% of parents disagree of having difficulty with the internet, and 7.4% agree. | |

| My internet network or quota at home is fulfilled during online learning | Most parents and children have a fulfilled quota and internet network during online learning at home | 43.3% of parents agree that they do not experience quota and internet problems, while 8.4% disagree | |

| Elaboration | The internet network or quota at my home is fulfilled during online learning | Most parents and children feel unburdened with the assignments given by the teacher | 41.9% disagree that the assignment given by the teacher is too heavy, while 10.8% agree |

| Confirmation | I always appreciate my children once they complete a session of online learning | Most parents give credit for the success of their children's online learning achievement | 62.6% of parents give appreciation compared to 1% who do not give appreciation |

Table 3.

Child physical abuse.

| Aspect | Question | Parents' response | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child physical abuse | I punished (pinching) my children if they neglected or refused to complete online assignments. | Most parents do not pinch their children if they neglect their online assignment | Only 1.5% of parents agree that they have pinched their children and 55.7% disagree. |

| I punished (pinching) my children if they used gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) too long. | Most parents do not pinch their children when they use gadgets for too long. | Only 5.4% of parents agree they have pinched their children when they use gadgets excessively, and 40.4% disagree. | |

| I have once forcibly taken (seized) the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) when the study time was over | Most parents do not take gadgets forcibly when their children's study time is over | 6.4% of parents agree they have taken gadgets by force when their children's study time is over, and 59.6% disagree | |

| I have once hit my children as they failed to obey the rules of studying or they refused to learn | Most parents never hit the children that do not obey the study rules | 5.9% of parents agree they have hit the children that do not obey the study rules, and 59.1% disagree |

Table 4.

Child emotional abuse.

| Aspect | Question | Parents' response | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child emotional abuse | I have been angry if my children use gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) to play games, instead of completing online learning | Most parents scold and yell at their children when they misuse gadgets to play online games | 63.5% of parents are angry when their children misuse their gadgets to play online games, while 8.4% are not angry |

| I was forced to take the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) when it exceeded the learning time limit | Most parents immediately take gadgets from their children when they exceed the study time limit | 58.1% of parents immediately take gadgets from their children, and 6.9% do not | |

| I threatened my children not to give them the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) anymore if they still violate the rules | Most parents threaten not to provide gadgets or laptops when their children violate the rules of online learning | 50.7% of parents threaten not to give gadgets or laptops when their children violate the rules, and 13.3 did not | |

| I have once had to shout to my children when they refused to learn. | Most parents disagree to shout at their children to be obedient in learning | 50.2% of parents disagree to shout at their children to be obedient in learning, and 23.2% still do it |

Table 5.

Child verbal abuse.

| Aspect | Question | Parents' response | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child verbal abuse | I criticized my children if they misused the internet not for online learning | Most parents criticize children when using the internet not for online learning | 72.9% of parents criticize their children when using the internet not following online learning and 4.9% do not |

| I strengthened my children to be enthusiastic about learning by comparing them with their colleagues | Most parents disagree to motivate children by comparing them with others | 36% of parents disagree to motivate their children by comparing them with others, and 23.2% still do | |

| I told my children to stop crying when they refused to follow the rules | Most parents tell their children to stop crying when they do not want to follow the rules. | 49.3% of parents tell their children to stop crying when they do not want to follow the rules, and 17.2% let them | |

| I accused my children of using the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) too often that they forgot about their assignments forgetting about their assignments. | Most parents disagree of accusing their children who are failing to carry out their assignments because they play too much on gadgets. | 42.4% of parents disagree, accusing their child of failing to carry out their assignments because they play too much on gadgets, and 20.2% still do | |

| I called my children lazy once they failed to complete the assignment | Most parents do not agree to call their children lazy when they fail to complete assignments | 45.8% of parents disagree calling their children lazy when they fail to complete the task, and 9.9% still do |

Table 6.

Child neglect.

| Aspect | Question | Parents' response | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child neglect | I allowed my children to insist on using the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop), although they had passed the study time limit | Most parents disagree of letting the children that insist on using mobile phone or laptop after finishing study | 45.3% of parents disagree of letting their children continue using mobile phone or laptops after studying, and 26.1% agree. |

| I allowed my children to use the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) for a long time, provided they did not cry | Most parents disagree of allowing their children to use gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) for a long time, provided they did not cry | 59.1% of parents disagree of allowing their children to use gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) for a long time, provided they did not cry, while 3% neglect it. | |

| I left my children to complete their assignments on their own when I was busy at work. | Most parents disagree of leaving their children completing their assignments on their own when the parents are busy working | 49.8% of parents disagree of letting their children complete their assignments on their own when the parents are busy at work, while 29.1% agree. |

Table 7.

Causing factors of parents to commit child abuse.

| Aspect | Question | Parents' response | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | Children watched videos (YouTube) which are not supposed for learning | Most parents agree to commit verbal and emotional abuse as their children watch videos outside the learning subject. | 78.9% of parents commit child verbal and emotional abuse because children watch videos outside the learning materials, while 21.1% do not. |

| During online learning, children were lazy to study | Most parents agree to commit verbal and emotional abuse because children are lazy to study | 71.1% of parents state that children are increasingly lazy to study through online learning at home, while 28.9% answer the opposite. | |

| Children could not complete the assignments independently from home | Most parents agree to commit verbal and emotional abuse because children are not independent | 65.8% of parents state that their children are not independent while at home, while 34.2% state the opposite. | |

| Parents | Parents experienced work pressure during the COVID-19 pandemic | Most parents agree to commit verbal and emotional abuse because there is increasing work pressure | 68.4% of parents state that one reason for child emotional abuse is work pressure, while 31.6% believes it is not. |

| Parents could not manage time of working and assisting their children study | Most parents agree to commit verbal and emotional abuse because they cannot manage time. | 66.7% of parents cannot manage time properly between working while teaching their children at home, while 33.3% state the opposite. | |

| Parents were tired of working and assisting their children to study | Most parents agree to commit verbal and emotional abuse because they are tired of working and assisting children studying from home | 78.9% of parents are tired of working while assisting their children to study at home, while 21.1% state the opposite. |

2.1. Research instruments and measurements

The research instrument was formulated based on five parts, including online learning, child physical abuse, emotional abuse, verbal abuse, and neglect. The questionnaire comprised of a number of questions covering information about the children's and parents' experiences during online learning was then structured on the ground of the research instrument. Statements regarding online learning are as follows:

-

(1)

During the pandemic, I accompanied my children in online learning at home,

-

(2)

My children and I had difficulty using online learning media (Smartphone/Laptop/Computer) while studying from home,

-

(3)

I had difficulty finding information on the internet about my children's school's daily assignments,

-

(4)

My internet network or quota at home was fulfilled during online learning,

-

(5)

The assignments given by the teacher were too heavy for the children.

-

(6)

I always appreciated my children once they accomplished a session of online learning.

Statements on the experience of child physical abuse:

-

(7)

I punished (pinching) my children if they neglected or refuse to complete online assignments

-

(8)

I punished (pinching) my children if they used gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) too long

-

(9)

I have once forcibly taken (seized) the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) when the study time was over

-

(10)

I have once hit my children as they failed to obey the rules of studying or they refused to learn

Statements regarding the experience of child emotional abuse:

-

(11)

I have been angry if my children use gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) to play games, instead of completing online learning

-

(12)

I was forced to take the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) when it exceeded the learning time limit

-

(13)

I threatened my children not to give them the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) anymore if they still violate the rules

-

(14)

I have once had to shout to my children when they refused to learn

Statements on the experience of child verbal abuse:

-

(15)

I criticized my children if they misused the internet not for online learning

-

(16)

I strengthened my children to be enthusiastic about learning by comparing them with their colleagues

-

(17)

I told my children to stop crying when they refused to follow the rules

-

(18)

I accused my children of using the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) too often that they forgot about their assignments

-

(19)

I called my children lazy once they failed to complete the assignment

Statements regarding the experience of child neglect:

-

(20)

I allowed my children to insist on using the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop), although they had passed the study time limit

-

(21)

I allowed my children to use the gadgets (mobile phone/laptop) for a long time, provided they did not cry

-

(22)

I left my children to complete their assignments on their own when I was busy at work.

3. Results and findings

3.1. Aspects of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

The forms of online learning carried out during the pandemic are categorized into exploration, elaboration, and confirmation. These three categorizations are obtained from the questionnaire distributed to parents, as shown in Figure 1.

In terms of exploration activities, parents and teachers involve children in finding information using technology, such as computers or laptops and smartphones. Furthermore, in elaboration, parents assist children in answering the assignments. In confirmation, parents provide feedback on children's learning outcomes through motivation, praises, and gifts. The data obtained from parents' and children's responses during online learning uncovers this experience, as shown in Table 2.

3.2. Aspects of child physical abuse

Relatively few parents committed physical abuse during online learning, such as hitting, pinching, or pushing. Furthermore, they controlled themselves, though they experienced many obstacles when assisting their children in online learning. This is indicated by the data shown in Figure 2.

Based on the questionnaire results, most parents still give a good care to and love their children and do not exercise child physical abuse during online learning. This is shown in Table 3.

3.3. Aspects of child emotional abuse

These results show that online learning impacts child emotional abuse through anger or screams, foreclosure, threats, and shouts. The data found a high level of child emotional abuse, as shown in Figure 3.

The survey shows a high child emotional abuse during online learning. Most parents yelled, forcefully took, threatened, and shouted at their children when they used gadgets not for the sake of online learning. This is presented in Table 4.

3.4. Aspects of child verbal abuse

This study reveals the state of child abuse during online learning. Child verbal abuse has been committed by parents or guardians during the period of work from home (WFH) and school from home (SFH) throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. This is indicated by the survey data in Figure 4.

The result of the survey shows high child verbal abuse during online learning. Most parents criticized, compared children to others, rebuked, and accused children for being lazy. This can be seen from the parents' statements in Table 5.

3.5. Aspects of neglect

The findings are that most parents do not neglect their children during online learning. This is evidenced by the survey results in Figure 5.

The survey shows that child neglect during online learning is quite low. Most parents disagree neglecting their children, as shown in Table 6.

3.6. Causes of child abuse: why parents commit abuse

The results show the occurrence of child verbal and emotional abuse. Child abuse committed by parents is quite high, with a number of causative factors as described in Table 7.

Children are necessitated to use mobile phones or laptops as learning media during online learning. In many cases, they watch YouTube videos out of the learning materials during the learning time and do not pay attention the assignments or lessons delivered by the teacher which triggers their parents' anger. This is in line with one of respondent's statement stating that:

“I often find my children watching videos which is not for their age, and I usually get angry because of this. I told them: 'Dear, please stop playing with your phone! It has been too long. Give me that cell phone, or I will not give it again forever.' I actually allowed my children to use their mobile phones for the purpose of their study, to complete assignments from school and of course for entertainment purposes as well, so that they won't get bored while at home. In fact, they use the mobile phone not for studying or watching learning materials, but they watch un-educative scenes inappropriate for their age. My children also play games more often instead of completing their assignments. This annoys me so much.”

Working and educating children are nevertheless the responsibility of every parent, even during the COVID-19 pandemic which bears multiple obstruction. Concurrent working and teaching has been one of the cause of child emotional and verbal abuse. This is because tired parents produce higher emotional feelings which lead to unloving acts to the children. These children, who actually need more attention at home, consequently become the victim.

4. Discussion

Parents working from home while at the same time children studying from home has, to some extent, increased the attachment between them. Although the workload escalates, parents assume more demand and responsibility for their children's online education at home. Online learning, as a matter of fact, increases parents' digital literacy, indicated by the provision effort for online facilities and frequent information searching through internet connection either for their personal purposes or for their children's assignment completion. This is in accordance with Purnama's et al. (2021) statement that online learning through internet media helps students work efficiently (Purnama et al., 2021).

The result of the survey shows that there are still parents who commit physical violence to children during online learning which resulted from the increasing workload and work pressures during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is in line with the results of a survey conducted by the Indonesian Child Protection Commission (KPAI) that macro-physical violence against children still occurs during online learning even though the intensity is lower compared to emotional violence. Physical violence such as beatings is accounted for only 10%, while emotional violence, such as children being scolded, has been accounted for 56% (KPAI, 2021). In this case, no matter how small, the act of violence should not occur to any children. Brown (2020) suggests that the role of parents is to reduce children's stress levels, provide optimum support for their safety, self-exploration, and excellence during online learning at home (Brown et al., 2020).

Furthermore, this study also reveals the occurrence of emotional violence against children committed by parents during online learning due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic, undeniably, bears psychological trauma to parents and children. Furthermore, unreadiness in adapting for new habits raises emotional stress and some related attitudes. Carrying out online learning while playing online games and watching unrelated-to-learning contents is inevitable during the pandemic. As a consequence, this will likely lead to the state of anger and aggravation, or the act of yelling and shouting as an expression of psychological trauma that occurs spontaneously. This is consistent with Abdullah's opinion (2020) that the pandemic brings about psychological trauma which further causes domestic violence (Abdullah, 2020).

Child verbal abuse also reflects psychological trauma during the pandemic. Parents often criticize their children's learning outcomes as a form of dissatisfaction expression. This act reduces children's mental health, produces self-inferiority, depression, and uncomfortable feeling as they perceive that their work is always wrong. Consequently, their insecurity affects their self-efficacy in subsequent developments. This is in line with Kerns and Brumariu (2014), who stated that insecurity contributes to children's anxiety and other mental problems (Kerns and Brumariu, 2014).

On one hand, seen from the parents' perspective, online learning does not necessarily reflect children's neglect. Parents embrace dual role during pandemic i.e., working from home to be able to survive and assisting children schooling from home. The former which is considered as the main task by parents has occasionally been misinterpreted by children as giving less attention and learning assistance. In addition, parents are not prepared and do not master the learning materials delivered by teachers. This also implies that the pandemic has added new role to parents that is being school teachers at home.

Parents feel increasing pressured as they have to carry out dual role as teachers at home while accomplishing heavy workloads received from their workplace. Although parents usually feel tired after work, are not prepared in terms of mental, physical, and knowledge mastery, they still have to assist and be their children offline teacher explaining school lessons. As a result, they commit child abuse during online learning in the period of COVID-19 pandemic. Scarpellini et al. (2021) stated that 72.2% of parents in Italy, especially mothers, are against changing their role to become teachers in online learning (Scarpellini et al., 2021). This is where children may misperceive their parents in online learning at home.

Child abuse occurs because of new phenomenon that is studying and working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education which is usually carried out in schools and managed by teachers, has been inevitably replaced at home handled by parents. The children's task is to simultaneously attend online learning delivered by the teachers and offline learning guided by the parents. These two aspects i.e., parents and children, to a certain extent, each of which contribute in forming child abuse.

On the other hand, viewed from the children's perspective, they cannot concentrate on online learning and rather play online games or watch YouTube which are not related to the learning materials. Therefore, child abuse can also be experienced as a result of children being less independent while learning online. In fact, their inability to independently complete the assignments is caused by limited information, communication, and understanding of the online and offline instructions delivered by teachers and parents, respectively.

5. Conclusion

Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in children's psychological trauma which further led to mental health vulnerabilities and child abuse. This study initially argues that the change from face-to-face to online learning has created stress among parents and children due to the lack of readiness. The findings show that child verbal and emotional abuse committed by parents was increasing during the online learning. The economic pressure experienced by parents due to the lockdown policy, lack of digital literacy, and unpreparedness as a 'new teacher' are common stressors manifested through child abuse. Therefore, a thorough investigation on this problem is crucial as it may lead to vulnerability of children's mental health. Social restrictions (lockdown) policy and school closures have been enforced by government without any direct assistance to families. This study suggests the importance of involving parents as the main partners besides teachers in educational success.

This study further raises a question on empowering parents in light of children learning assistance both in pandemic and normal period. It is then suggested that parents are required to continuously improve understanding and knowledge during the pandemic to provide learning assistance for their children. The underlying factors triggering child abuse should be minimized to facilitate the development of children's mental health as well as their academic achievement. This study has limitations, especially in terms of extracting information, which mostly focused on parents. Therefore, further study will likely focus on children, teachers, and environmental perspective. Moreover, due to the importance of these findings, policymakers should consider multiple impacts of online learning following the prolonged school closures and social restrictions and review the importance of systemic support for children's mental health and family resilience.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Suyadi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Issaura Dwi Selvi: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by LPPM (Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat) / Indonesian Institute of Research and Community Service (LPPM).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abdullah I. COVID-19: threat and fear in Indonesia. Psychol. Trauma: Theo. Res. Pract. Pol. 2020 doi: 10.1037/tra0000878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baihaqi A. Detik News; 2020. Siswi SD Kabur Usai Dimarahi Ibu Karena Habiskan Pulsa Untuk Daring. [Google Scholar]

- Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020;38(12):2753–2755. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.M., Doom J.R., Lechuga-Peña S., Watamura S.E., Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodini J. Online learning in the time of COVID-19. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;34:101669. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian C.W. 2015. Clinical Report Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care the Evaluation of Suspected Child Physical Abuse. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates E.E., Dinger T., Donovan M., Phares V. Adult psychological distress and self-worth following child verbal abuse. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma. 2013;22(4):394–407. [Google Scholar]

- Daryanto, Dwicahyono A. In: Pengembangan Perangkat Pembelajaran (Silabus, RPP, PHB, Bahan Ajar) first ed. Purwanto D., editor. Gava Media; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan S. Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Favale T., Soro F., Trevisan M., Drago I., Mellia M. Campus traffic and e-Learning during COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Network. 2020;176:107290. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R., Dubey M.J., Chatterjee S., Dubey S. Impact of COVID -19 on children: special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatr. 2020;72(3) doi: 10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadiwidjojo V.I. 2020. Covid-19 Dan Kekerasan Ke Anak Yang Meningkat.https://republika.co.id/berita/qbnmuq328/covid19-dan-kekerasan-ke-anak-yang-meningkat [Google Scholar]

- Harnani S. 2020. EFEKTIVITAS PEMBELAJARAN DARING DI MASA PANDEMI COVID-19.https://bdkjakarta.kemenag.go.id/berita/efektivitas-pembelajaran-daring-di-masa-pandemi-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M., Drake B., Cobetto C., Ocampo M.G. Washington University; St. Louis: 2020. Child Abuse Prevention Month in the Context of COVID-19 [Center for Innovation in Child Maltreatment Policy, Research and Training] [Google Scholar]

- Kemenpppa . 2020. TANTANGAN ORANG TUA HADAPI ERA NEW NORMAL.https://www.kemenpppa.go.id/index.php/page/read/29/2771/tantangan-orang-tua-hadapi-era-new-normal [Google Scholar]

- Kerns K.A., Brumariu L.E. Is insecure parent-child attachment a risk factor for the development of anxiety in childhood or adolescence? Child Develop. Perspect. 2014;8(1) doi: 10.1111/cdep.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Vol. 52. 2020. Learning and teaching online during covid-19: experiences of student teachers in an early childhood education practicum; pp. 145–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber M., McTavish J.R., Couturier J., Le Grange D., Lock J., MacMillan H.L. Identifying and responding to child maltreatment when delivering family-based treatment—a qualitative study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019;52(3):292–298. doi: 10.1002/eat.23036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury I. Online learning: how do brick and mortar schools stack up to virtual schools? Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10450-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KPAI . Komisi Perlindungan Anak Indonesia; 2021. Hasil survei Pemenuhan hak dan Perlindugan anak pada masa Pandemi COVID-19. bankdata.kpai.go.id. [Google Scholar]

- Limbers C.A. 2020. Factors Associated with Caregiver Preferences for Children’s Return to School during the COVID-19 Pandemic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek M.W., Sheng Chew C., Teknologi Mara U., Alam S., Vivian Wu W.-C. Teacher experiences in converting classes to distance learning in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Dist Educ. Technol. 2021;19(1) [Google Scholar]

- Mathews B., Bromfield L., Walsh K. Comparing reports of child sexual and physical abuse using child welfare agency data in two jurisdictions with different mandatory reporting laws. Soc. Sci. 2020;9(5):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mogaddam M., Kamal I., Merdad L., Alamoudi N. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of dentists regarding child physical abuse in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;54:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder T.M., Kuiper K.C., van der Put C.E., Stams G.J.J.M., Assink M. Risk factors for child neglect: a meta-analytic review. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;77:198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munastiwi E., Puryono S. Unprepared management decreases education performance in kindergartens during Covid-19 pandemic. Heliyon. 2021;7(5) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberger E.H. Understanding of child abuse and neglect. J. Am. Coll. Dent. 1994;61(1):26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ney P.G. Does verbal abuse leave deeper scars: a study of children and parents. Can. J. Psychiatr. 1987;32(5):371–378. doi: 10.1177/070674378703200509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman R.E., Byambaa M., De R., Butchart A., Scott J., Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novianti R., Garzia M. Parental engagement in children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Teach. Learn. Elemen. Educ. 2020;3(2) [Google Scholar]

- NSPCC . 2020. Definitions and Signs of Child Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Nurfauziah M.A., Raharjo S.T., Krisnani H. 2020. Dampak Pembelajaran Daring Terhadap Anak Selama Pandemi Covid-19. Researchgate.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342353957_DAMPAK_PEMBELAJARAN_DARING_TERHADAP_ANAK_SELAMA_PANDEMI_COVID-19 [Google Scholar]

- Pannekoek F. second ed. Athabasca University; AU: 2008. THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF ONLINE LEARNING. [Google Scholar]

- Pasian M.S., Benitez P., Lacharité C. Child neglect and poverty: a Brazilian study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020;108:104655. [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel S., Chhetri R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Educ. Future. 2021;8(1):133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Purnama S., Ulfah M., Machali I., Wibowo A., Narmaditya B.S. Does digital literacy influence students’ online risk? Evidence from covid-19. Heliyon. 2021;7(April) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhanty R. 2020. Takut Tak Bisa Ikut Belajar Online, Siswi 14 Tahun Bunuh Diri.Www.Dream.Co.Idhttps://www.dream.co.id/unik/siswa-14-tahun-bunuh-diri-karena-ketakutan-tak-bisa-hadiri-kelas-online-200611k.html [Google Scholar]

- Rerkswattavorn C., Chanprasertpinyo W. Prevention of child physical and verbal abuse from traditional child discipline methods in rural Thailand. Heliyon. 2019;5(12) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosalin L.N. 2020. Kekerasan Terhadap Anak Meningkat Selama Pandemi Covid-19.https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1343008/kekerasan-terhadap-anak-meningkat-selama-pandemi-covid-19/full&view=ok [Google Scholar]

- Sakakihara A., Haga C., Kinjo A., Osaki Y. Association between mothers’ problematic Internet use and maternal recognition of child abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;96 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpellini F., Segre G., Cartabia M., Zanetti M., Campi R., Clavenna A., Bonati M. Distance learning in Italian primary and middle school children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. BMC Publ. Health. 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11026-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F.D., Loveland Cook C.A., Salas J., Scherrer J., Cleveland I.N., Burge S.K. Childhood trauma, social networks, and the mental health of adult survivors. J. Interpers Violence. 2020;35(5–6):1492–1514. doi: 10.1177/0886260517696855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shammi M., Bodrud-Doza M., Towfiqul Islam A.R.M., Rahman M.M. COVID-19 pandemic, socioeconomic crisis and human stress in resource-limited settings: a case from Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2020;6(5) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subedi S., Davison C., Bartels S. Analysis of the relationship between earthquake-related losses and the frequency of child-directed emotional, physical, and severe physical abuse in Haiti. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;106(March 2019):104509. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhendro E. Strategi pembelajaran pendidikan Anak Usia Dini di Masa pandemi covid-19. Golden Age: J. Ilmiah Tumb. Kemb. Anak. Usia Dini. 2020;5(3):133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne K. 2007. Blended Learning: How to Integrate Online and Traditional Learning. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . 2020. Covid-19 and Children in Indonesia.https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/id/laporan/covid-19-dan-anak-anak-di-indonesia [Google Scholar]

- Vallely C. 2020. Anak-anak Rentan Menjadi Korban Kekerasan Selama Pandemi.https://www.voaindonesia.com/a/anak-anak-rentan-menjadi-korban-kekerasan-selama-pandemi-/5482823.html [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.