The World Health Organization defines acupuncture (zhen) in their 2007 glossary1 as: “the insertion of needles into humans or animals for remedial purposes or its methods.” The term ‘acupuncture’ was first coined in the 1680s, ‘acu’ is derived from the Latin ‘acus’, needle, so that the word means ‘needle puncture.’2 While the notion of acupuncture as a method of inserting needles into the body to help treat symptoms is a commonly held opinion, is this understanding and definition correct?

The term translated as ‘acupuncture’ in Chinese is ‘zhen’ (Japanese ‘shin’, Korean ‘chim’) [see Box 1 for characters], a noun that means needle or pin. The character zhen is a composite of two characters: ‘jin’ which means ‘gold or metals in general’, and ‘xian’ which means ‘together, all, completely, united’. The two components together as zhen came to refer to metal objects used in treatment. Neither the character nor the components of the character imply or mean insertion into the body. But the earliest etymological dictionary in China describes zhen in relation to sewing [Box 2], which implies insertion of some kind; while the tool used for sewing cloth may need to be sharp and thin like a needle, the tool for sewing thick leather is usually thicker and can be non-sharp, even blunt as it is pushed through pre-made holes. The term can thus refer to a variety of metal tools some of which are inserted. A term commonly found in the Neijing that refers to the act of insertion (of needles) is the character ‘ci’, a verb meaning to stab, to prick. [see Boxes 1 and 2]. In his overview of the discussion of needling, Unschuld highlights that the term ci is specifically used in the Neijing to refer to inserting needles.3 When zhen were first described as treatment devices in the Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine), circa 100 BCE, nine types of zhen were described.4 Among the nine zhen, the round-pointed needle and spoon needle were not intended for penetration of the skin but to be used by pressing or massaging acupuncture points or meridians,5, 6, 7 and detailed illustrations of the non-penetrating needles is shown in the paper by Kim and colleagues.7 With one of the nine zhen, the thinnest needle the ‘haozhen’, ‘hair’ or filiform needle, becoming dominant and most commonly inserted into the body, the other eight are less commonly used, but remain in use in Asia and the West.1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 We thus immediately see a problem with the choice of the term ‘acupuncture’ as translation for the term ‘zhen’ since some ‘zhen’ tools are not inserted when used in treatment. The WHO glossary describes the two types of needles that are not inserted into the body,1 but like other publications, it does not draw attention to the potential inaccuracy and misleading use of the term ’acupuncture’ to refer to the use of these non-inserted tools. It has been common practice for words to come into daily use regardless of their actual meaning. English speaking atheists will be surprised to learn that when they say ‘goodbye’ to someone they are saying ‘God be with you.’2 Many such words with different meanings are used in daily discourse. While the term ‘acupuncture’ has de facto become the word that refers to a family of medical procedures that involve needles and commonly involve recourse to traditional Chinese or East Asian concepts like ‘qi’, ‘yin-yang’, ‘meridians’ and so on, 5,6 the misunderstanding implicit in this word can be problematic for researchers. Here, we continue to use the term ‘acupuncture’ since it has fallen into common use, but our intended use is as a term that refers to a broader family of therapies that employ zhen tools. We propose that there should at least be an academic discussion of whether the continued use of the term ‘acupuncture’ is appropriate or whether a better term should be developed that is not so misleading or at variance with historical and modern practice methods.

Box 1. – Chinese characters.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Box 2. – zhen, ci meaning.

The Shuowen Jiezi, etymological dictionary from circa CE 100 describes zhen in relation to sewing (metal [tool] to make whole [all]) and ci as a thorn, to prick or stab, (resulting in) vertical injury (like a knife)

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

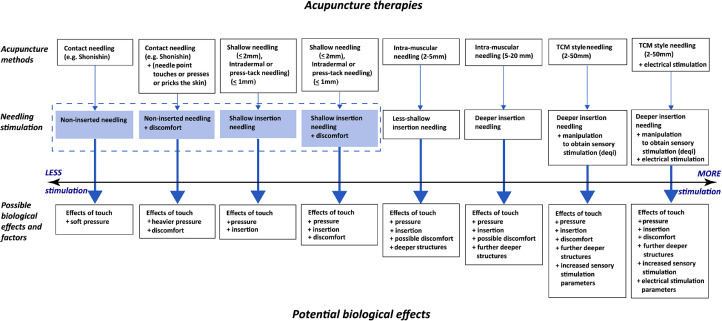

1. Examples of the varieties of contemporary ‘acupuncture’ methods

-

-

Round ended, blunt tools or sharp pointed needles with touch or light pressure applications (Japanese Shonishin, contact needling, sanshin), 7,9,11, 12, 13, 14 using thin needles (0.12–0.18 mm gauge) without insertion common in Japanese Meridian Therapy.12,15, 16, 17

-

-

Round ended, blunt tools or sharp pointed needles with pressure, potentially with discomfort or pricking sensations (e.g. Shonishin, contact needling, Toyohari) .7,9, 10, 11, 12

-

-

Thin needles (0.12–0.18 mm gauge) shallowly inserted (1–3 mm) e.g. the Japanese ‘chishin method,’8,15,18 or short thin needles (0.20 mm gauge) inserted shallowly and taped to remain in place.8,19 Of the latter two varieties are common, intradermal needles (usually 3–6 mm long) with needle inserted 1–3 mm subcutaneously, just beneath the skin (depth ≤1 mm)8,20 and press-tack needles (Japanese pyonex) inserted to depths of 0.3 mm, 0.6 mm, 0.9 mm and so on. Usually these are applied with no discomfort, but occasionally they cause pricking or discomfort8 [https://www.pyonex.info/testimonial.html]. Recent developments include special semipermanent needles placed in the ears in military rehabilitation settings.21

-

-

Thin needles inserted a little deeper (2–5 mm) and sometimes further (5–20 mm), usually intramuscularly without deliberate sensory stimulation (e.g. Japanese chishin needling), 8 but occasionally triggering some discomfort or sensory stimulation.8,22,23

-

-

Somewhat thicker needles (≥0.20 mm gauge) inserted often deeper and with manual manipulation so as to deliberately elicit sensory stimulation – called ‘deqi’ – often inducing a twitch in the muscle (TCM style needling methods).24,25 This has become the more common method taught in China and in most Western acupuncture schools.

-

-

Slightly thicker needles (≥0.20 mm gauge) inserted often deeper (2–50 mm) with manual manipulation so as to deliberately elicit sensory stimulation, and then with electrical stimulation added to the needles (electroacupuncture). The parameters of electrical stimulation can be varied by frequency and intensity, giving a range of different treatment approaches and effects.26,27

Fig. 1 summarises the above types of needling methods, moving from non-inserted on the left to more deeply inserted with strong stimulation on the right, it also suggests likely effects triggered by each.

Fig. 1.

Acupuncture techniques and their potential biological effects. Shaded boxes denote that the most common sham acupuncture techniques use non-penetrating and shallow insertion needling and are likely to inadvertently trigger the same biological effects as the non-penetrating and shallow insertion needling forms of acupuncture. TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

2. Research implications

It has been routine for clinical and laboratory researchers to assume that when they are investigating ‘acupuncture’ that they are studying the physiological effects and/or the clinical effects of needle insertion. We have seen above both in the meaning of the term ‘zhen’ and the formulation of ‘zhen’ as therapy, that insertion is not implicit or required. Making that distinction is found in some modern publications, as a few researchers have sought to differentiate the methods they investigated from what is understood as ‘acupuncture’, coining terms like ‘contact needling,’9,13,14 when investigating Japanese non-insertion treatment methods in the practice of acupuncture. While a good example of how to state clearly what is done, the field as a whole needs to pay more attention to this. It has also been suggested that when needles are inserted, we can distinguish between the ‘hard’ acupuncture methods found for example in China and the ‘soft’ acupuncture methods found in Western countries,28 to make clear what kind of needling techniques are being applied. This distinction can be seen in Fig. 1, where those on the right side would constitute more of the ‘hard’ more stimulating style and those moving to the left the ‘soft’ less stimulating style.

Another common assumption of laboratory and clinical researchers investigating acupuncture is that the needling should elicit the sensory stimulation of deqi. While there is a recognition that this is not necessarily required,29 it is still a commonly held belief guiding research on acupuncture,30 with additional questions about understanding the nature of deqi.30,31

It is also commonly assumed that there should be a general mechanism or set of mechanisms by which acupuncture should work, but with such a range of different types of technique used we must expect large differences according to the types of structures and tissues stimulated and whether the technique causes e.g. nociceptive input.32 Fig. 1 gives an overview of the potential biological responses triggered: on the left are soft, non-penetrating techniques, moving to the right models techniques as they become progressively deeper or more stimulating; we can expect additional mechanisms triggered as we move from left to right, see the illustrations and discussions of Zhang and colleagues.32

In the formulation of scientific acupuncture studies, it is fundamental that the researchers demonstrate an accurate and comprehensive understanding of the topic they are investigating. Furthermore, a number of key problems might arise from deficits in this understanding.

-

a

It is problematic to assume that the effects of acupuncture arise only after insertion of the needles

-

b

It is problematic to assume that the effects of acupuncture arise only after eliciting the sensory stimulation associated by e.g. TCM practitioners inducing deqi

-

c

These problematic assumptions led to the selection of techniques that sought to avoid the sensory stimulation associated with deqi and/or that avoid insertion of the skin as sham techniques in controlled clinical trials.33,34 These are inappropriate as ‘sham’ control treatments since they employ a number of physiological pathways that are known to be involved in the practice of acupuncture,32,35 making them potentially incapable of controlling for placebo effects – see also Fig. 1. The non-inserted sham interventions have also been found to be effective beyond placebo effects36 and the tools for their use appear to reduce the effectiveness of the test or ‘real’ acupuncture compared to inserted sham treatment methods.37 These active and potentially clinically effective ‘sham’ interventions result in underestimation of the effects of and bias against acupuncture.33,38,39

-

d

It is not clear what has been controlled for in sham comparison trials.40 It is often assumed that the sham treatment is a placebo treatment.41,42 When the trial does not find a statistically significant difference between treatment groups researchers and many reading those trials draw the questionable conclusion that acupuncture effects are primarily due to the placebo effect.

-

e

Hence analysis of results from sham-controlled studies have influenced the accurate estimation of treatment effect size, potentially leading to faulty conclusions.

-

f

Acupuncture studies usually test one of many acupuncture techniques and then draw conclusions about ‘acupuncture’ in general. At the very least researchers should state explicitly what it is that they investigated: for example ‘TCM acupuncture’, ‘contact needling’, ‘Electro-acupuncture’, ‘Japanese press-tack needles’, ‘Shonishin’ and discuss their results relative to that, with necessary documentation to support their statements.29,43 While the STRICTA guidelines29 for reporting clinical trials push researchers into being more specific about what was done in their trial, this remains a problem. This issue is relevant for systematic reviews and meta-analyses as well. One can conduct a meta-analysis of a class of medication such as ‘anti-depressants’ and draw conclusions about whether anti-depressants are effective or not. There may be sufficient data about a single anti-depressant to permit singling it out and drawing additional conclusions about that medicine. Similarly, one can perform a review of acupuncture trials and draw conclusions about ‘acupuncture’ as a whole. If one of the treatment methods has sufficient data to permit singling it out, it may also be possible to draw conclusions about it. In sum, just as a clinical trial of one type of antidepressant cannot draw conclusions about all antidepressants, so too trials of one acupuncture treatment method cannot draw conclusions about all acupuncture treatment methods.

-

g

More fundamental problems arise for scientific studies of acupuncture. If knowledge of what constitutes the practice of zhen therapies is constrained due to faulty assumptions from an understanding of what the term ‘acupuncture’ means, deeper problems arise in how scientific questions, hypotheses and null-hypotheses are developed.44 This cuts to the core of the scientific method. Take for example clinical research of a pharmaceutical substance. Clinical investigations of the substance are only begun after the chemical composition and the properties of that chemical have been without error described and studied.45 It is inconceivable that clinical studies of that pharmaceutical substance would begin before these fundamental steps and requirements had been met. If we now examine clinical studies in acupuncture, we immediately encounter significant challenges: There is a paucity of basic research including academic studies about the nature of acupuncture, so that clinical and laboratory research are often insufficiently informed and researchers operate with inaccurate assumptions.43,46 In addition to the documentation needed to validate treatment claims29,43,46 Fonnebo and colleagues propose in their description of a research framework for complementary therapies like acupuncture, that acupuncture trials can proceed without definitive knowledge of mechanism while additional laboratory studies continue to establish those mechanisms.45 Although there is an acknowledged difficulty associated with defining the precise mechanisms of acupuncture due to the complexity of potential mechanisms that can be involved,32,40 there remain unrecognised problems regarding what constitutes the nature and practice of ‘acupuncture.’ The research community has not devoted enough effort to exploring what it is that they are investigating. It is not enough to cite the expertise of a single individual nor the consensus of a single group if the goal is to study the field of acupuncture rather than a single member of the family of acupuncture treatment methods.

3. Conclusions

While research on acupuncture has increased, especially in the last 20 years, core issues about what is acupuncture, as described in this paper, have been omitted or poorly addressed. They were neither present in the early days of acupuncture research nor have they fully been understood in contemporary acupuncture research. This has created significant problems for research on acupuncture, in particular clinical research efforts that attempt to control for placebo effects using sham acupuncture.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this article.

Ethical statement

There are no ethical issues with this article.

Data availability

There are no available data beyond that cited in the references.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Stephen Birch: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Myeong Soo Lee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Tae-Hun Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Terje Alraek: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

All the authors are part of the journal's editorial board but it was externally reviewed and they had no bearing on the editorial process. There are no other conflicts of interest regarding this paper.

References

- 1.WHO Western Pacific Region . World Health Organization; 2007. WHO International Standard Terminologies on Traditional Medicine in the Western Pacific Region. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Websters . 2nd edition. Collins World; USA: 1978. New Twentieth Century Dictionary. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unschuld P.U., Nei Huang Di, Wen Jing Su. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2003. Nature, Knowledge, Imagery in an Ancient Chinese Medical Text. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unschuld P.U, Huang Di Nei, Jing Ling Shu . University of California Press; Berkeley: 2016. The Ancient Classic On Needle Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu G.D., Needham J. Cambridge University Press; 1980. Celestial lancets, a History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birch S., Felt R.L. Elsevier Health Sciences; 1999. Understanding Acupuncture. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim H.J., Lee K.H., Yang G.Y. Illustrations of the nine types of needles based on Huangdi's internal classic Ling-shu. J Acupunct Res. 2019;36(1):38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birch S., Ida J. Paradigm Publications; Brookline: 1998. Japanese Acupuncture: A Clinical Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chant B.C.W., Madsen J., Coop P., Dieberg G. Contact tools in Japanese acupuncture: an ethnography of acupuncture practitioners in Japan. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2017;10(5):331e339. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song S.Y., Wang X.J., Zhang J.B., Gu Y.Y., Hou X.F. The origin, development and mechanisms of special acupuncture needle tools for cutaneous region. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2019;44(7):533–537. doi: 10.13702/j.1000-0607.190015. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shonishin Birch S. 2nd edition. Thieme Medical Publishers; Stuttgart: 2016. Japanese Pediatric Acupuncture. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukushima K. Toyo Hari Medical Association; 1991. Meridian Therapy: A Hands-on Text On Traditional Japanese Hari Based On Pulse Diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa K., Ogawa M., Nishijima K., Tsuda M., Nishimura G. Efficacy of contact needle therapy for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/928129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogawa-Ochiai K., Takebe T., Iwahashi M., et al. The efficacy of a traditional Japanese acupuncture method, contact needle therapy (CNT), on peripheral blood flow of the skin. Artificial Life and Robotics. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10015-020-00615-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shudo D. Eastland Press; Seattle: 1990. Japanese Classical Acupuncture: Introduction to Meridian Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikeda T., Ikeda M. Kampo In Yo Kai; Imahari City: 1991. Zo Fu Keiraku Kara Mita Yakuho to Shinkyu. Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ono B. Ido no Nippon; Yokosuka city: 1988. Keiraku Chiryo Shinkyu Rinsho Nyumon. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oleson T. Ed 3. Churchill Livingstone; London: 2003. Auriculotherapy Manual: Chinese and Western systems of Ear Acupuncture. [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Connor J., Bensky D. Eastland Press; Seattle: 1981. Acupuncture: a Comprehensive Text. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu J.H., Shepherd R. In: Acupuncture in Modern Medicine. Chen LI, Cheng TO, editors. Intech Open books; 2013. Fu's subcutaneous needling: a modern style of acupuncture? https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/43314. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy C.E., Casler N., FitzGerald D.B. Battlefield acupuncture: an emerging method for easing pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;97(3):e18–e19. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldry P.E. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1989. Acupuncture Trigger Points and Musculoskeletal Pain. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldry P. Superficial versus deep dry needling. Acup Med. 2002;20(2–3):78–81. doi: 10.1136/aim.20.2-3.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng X.N. Foreign Languages Press; Beijing: 1987. Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maciocia G. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1994. The Practice of Chinese medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulett G.A., Han S.P., Han J.S. Electroacupuncture: mechanisms and clinical application. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pomeranz B., Berman B. In: Basics of Acupuncture. Stux G, Berman B, Pomeranz B, editors. Springer; Berlin: 2003. Scientific basis of acupuncture; pp. 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y.M. Who has the final say on the dose of acupuncture? Comment on the article by Tu et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(6):1089–1090. doi: 10.1002/art.41664. Epub 2021 May 7. PMID: 33497025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macpherson H., Altman D.G., Hammerschlag R., et al. on behalf of the STRICTA revision group. Revised standards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT Statement. Acupunct Med. 2010;28(2):83–93. doi: 10.1136/aim.2009.001370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birch S. Historical and clinical perspectives on de qi: exposing limitations in the scientific study of de qi. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21(1):1–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai X.S., Tong Z. A study on the classification and the ‘catching’ of the ‘arrived qi’ in acupuncture. J Trad Chinese Med. 2010;30:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z.J., Wang X.M., McAlonan G.M. Neural acupuncture unit: a new concept for interpreting effects and mechanisms of acupuncture. Evid Based Compl Alternat Med. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/429412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birch S., Lee M.S., Kim T.H., Alraek T. Historical perspectives on using sham acupuncture in acupuncture clinical trials. Integrat Med Res. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2021.100725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chae Y. The dilemma of placebo needles in acupuncture research. Acupunct Med. 2017;35(5):382–383. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2017-011394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chae Y., Lee Y.S., Enck P. How Placebo needles differ from Placebo pills? Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:243. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang C.S., Tan H.Y., Zhang G.S., Zhang A.L., Xue C.C., Xie Y.M. Placebo devices as effective control methods in acupuncture clinical trials: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim T.H., Lee M.S., Alraek T., Birch S. Acupuncture in sham device controlled trials may not be as effective as acupuncture in the real world: a preliminary network meta-analysis of studies of acupuncture for hot flashes in menopausal women. Acupunct Med. 2020;38(1):37–44. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2018-011671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appleyard I., Lundeberg T., Robinson N. Should systematic reviews assess the risk of bias from sham–placebo acupuncture control procedures? Eur J Integr Med. 2014;6:234–243. [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacPherson H., Vertosick E., Lewith G., Linde K., Sherman K.J., Witt C.M., et al. Influence of control group on effect size in trials of acupuncture for chronic pain: a secondary analysis of an individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e93739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langevin H.M., Wayne P.M., Macpherson H., et al. Paradoxes in acupuncture research: strategies for moving forward. eCAM. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/180805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Streitberger K., Friedrich-Rust M., Bardenheuer H., et al. Effect of acupuncture compared with placebo-acupuncture at P6 as additional antiemetic prophylaxis in high-dose chemotherapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: a randomized controlled single-blind trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:2538–2544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu X., Hamilton K.D., McNicol E.D. Acupuncture for pain in endometriosis. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2011;(9) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007864.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Birch S. Testing the claims of traditionally based acupuncture. Complem Ther Med. 1997;5(3):147–151. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Birch S., Lewith G. Acupuncture Research. Elsevier; 2008. Acupuncture research: the story so far; pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fønnebø V., Grimsgaard S., Walach H., et al. Researching complementary and alternative treatments – the gatekeepers are not at home. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Birch S. Issues to consider in determining an adequate treatment in a clinical trial of acupuncture. Complem Ther Med. 1997;5:8–12. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no available data beyond that cited in the references.