Abstract

Protein–RNA interactions are of vital importance to a variety of cellular activities. Both experimental and computational techniques have been developed to study the interactions. Because of the limitation of the previous database, especially the lack of protein structure data, most of the existing computational methods rely heavily on the sequence data, with only a small portion of the methods utilizing the structural information. Recently, AlphaFold has revolutionized the entire protein and biology field. Foreseeably, the protein–RNA interaction prediction will also be promoted significantly in the upcoming years. In this work, we give a thorough review of this field, surveying both the binding site and binding preference prediction problems and covering the commonly used datasets, features and models. We also point out the potential challenges and opportunities in this field. This survey summarizes the development of the RNA-binding protein–RNA interaction field in the past and foresees its future development in the post-AlphaFold era.

Keywords: protein–RNA interaction, deep learning, protein structure, RNA structure

1 Introduction

Protein–RNA interactions are involved in a variety of cellular activities, such as gene expression regulations [1], post-transcriptional regulations [2] and protein synthesis [3]. The perturbation of such interactions can lead to fatal cellular dysfunction and diseases [4]. Owing to their importance, researchers have made significant efforts to understand the interactions [5] and the related molecular mechanism behind the processes [6, 7]. Because of the difficulty to perform high-throughput structural biological experiments in the last century, the progress of this field was slow [8]. However, with the development and advancement of high-throughput assays, such as the in vivo RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP)-seq [9] and crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP)-seq [10], and the in vitro RNACompete [11] and High-throughput systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (HT-SELEX) [12], we have witnessed the significant progress of this field as well as the large amount of accumulated data [2]. Computational methods emerge to analyze the data and accelerate the discovery [13–18].

Similar to the experimental techniques, which can be divided into the structure-based methods and the assay-based methods, the computational methods can also be classified into two categories, either predicting the RNA-binding sites on the protein surface [3, 19] or modeling the preferred RNA sequences of an RNA-binding protein (RBP) [20]. In the first category, people essentially resolve a binary classification problem. Given the protein, researchers want to predict whether it is an RBP, and if it is an RBP, at which amino acids (AAs) it can interact with an RNA. In the latter one, given a protein with the high-throughput assay experimental data, people extract the frequency of each nucleotide at each position on the preferred RNA sequences, using k-mer models [21], position weight matrix (PWM) models [1] or deep learning models [2]. If the computational method targets on genome-wide prediction, sometimes, it is also referred as the binding sites prediction on RNAs [22, 23], which may cause confusion to the readers. In the rest of the paper, binding sites prediction refers to predicting the RNA-binding sites on the protein surface, whereas the binding preference prediction refers to predicting the protein binding preference against RNA sequences. On the other hand, as both of the two main research directions are protein-centric [4], which means that there is intrinsic relation between the two research topics, researchers are also trying to predict both information simultaneously with a unified deep learning method [17].

Since the first computational method was proposed to tackle the interaction between RNA and protein specifically [24], a number of algorithms have been developed to handle the problems [3, 19, 25–27]. They can be divided into the following categories. Firstly, based on the assumption that similar structures may have similar function, people have used the template-based method to predict the binding sites [28–31] and the binding preference [32]. Although such methods can perform well on queries with homologs, they have difficulty in handling new sequences without homologs [33]. Secondly, people combine hand-crafted features, which will be discussed in the next paragraph, with shallow-learning methods, such as support vector machine (SVM) [34–37], logistic regression [38–41] and random forest [42, 43], to investigate the topic. The commonly used k-mer models [39] and PWM models [38] are classified into this category, because they are usually combined with logistic regression. Notice that this category of methods is still under active development [36, 37], even after the surge of deep learning, because it is difficult to represent and encode the raw structural information, which will be discussed in detail in this paper. The last category is the deep learning-based methods [2, 14, 17], which have been very popular in recent years. With such models, people only need to input the raw representation of the proteins or RNAs, and let the models learn and extract useful information by themselves. However, the transparency and interpretability of the models are usually questioned [44].

Within the above algorithms, people have been using various features, including the ones from both proteins and RNAs. Regarding the protein features, researchers have developed representations from sequences, such as sequence one-hot encodings [3], Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) [37, 45] and conservation entropy derived from PSSM. The physicochemical properties [46], including hydrophobicity, electrostatics and atom types, are also helpful. Although the individual local protein structural information, such as residue propensity and solvent accessibility (SA), has been adopted for a while [19], recently, researchers have shown that directly using the comprehensive local structural encoding can significantly improve the model’s performance [17, 47]. For example, people have used voxels [47] and graphs [48] to encode the protein 3D structures. In terms of the RNA features, the logic is similar to the protein ones. Regarding the sequence features, people have been using the sequence one-hot encodings [2, 14, 49], k-mer models [39] and PWM [38, 39]. However, unlike the protein secondary structures (SSs), RNA secondary structural information has been significantly emphasized, including both the predicted RNA SSs and the in vivo structure profiles [14, 35, 38, 40]. Meanwhile, the tertiary structures are also shown to be very important [50]. Despite the large variety of existing features, unfortunately, people have not taken full advantage of them for the following two reasons. Firstly, in the binding site prediction, people usually only consider the protein information, whereas in the binding preference prediction, people usually only consider the RNA information. Similar to drug-target interaction (DTI), the interactions between RNAs and proteins include at least two molecules, and using information from only one side could lead to inferior performance [51–53]. Secondly, the RNA and protein structural information has not been fully utilized as well, mainly due to the limitation of previous structure prediction methods and the unsatisfactory structure encoding methods.

In recent years, we have witnessed the significant improvement of both the structure determination methods [54] and prediction methods [33, 55–60]. Considering the success of the previous computational methods targeting protein–RNA interaction prediction based on structural information, it is foreseeable that researchers will make significant progress in this field (Figure 1). Given that, we review this field thoroughly in this paper, emphasizing the structural information. In this work, we also consider the protein–RNA interaction binding site and binding preference prediction simultaneously for the first time, considering their intrinsic relationship. We notice that there are some existing related reviews focusing on different aspects of this problem. More specifically, Pan et al. [61], Yan and Zhu [25] and Sagar and Xue [26] list the recently developed deep learning tools for predicting binding preference. Trabelsi et al. [20] evaluate the performance of different deep learning models on predicting the binding preference. Yan et al. [3], Si et al. [62] and Miao and Westhof [19] list and evaluate the tools for predicting binding sites on protein, whereas all the involved methods were developed before 2014, which means that the deep learning methods are not included. Hafner et al. [13], Ramanathan et al. [4], Licatalosi et al. [63], and Corley et al. [5] summarize the related biological experimental techniques to study the interactions as well as the biological insights and mechanism behind the interactions. More recently, Jamasb et al. [64] concluded the computational methods for protein–protein interaction site prediction with deep learning approaches. Also, the work of Day et al. [65], namely message passing neural processes (MPNPs), successfully improved the performance of the node classification task in the protein–protein interaction site prediction problem. It uses the protein structural data as the interacting residue graph, which thrives at lower sampling rates. Our work, which unifies two intrinsically related computational problems and highlights the importance of structural information, can provide new insights into the topic. Table 1 summarizes the main focuses of different review papers.

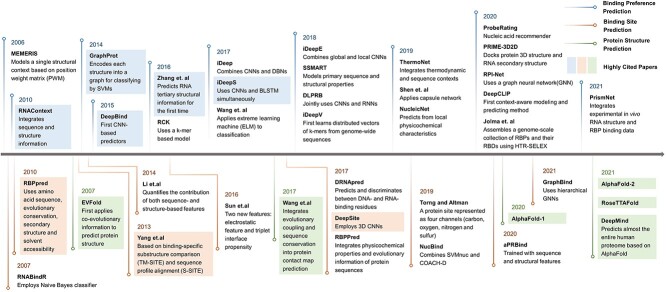

Figure 1.

An overview of important works related to binding site and binding preference prediction. Protein structure prediction methods are also included because of their rising importance in interaction prediction. The three categories are represented by different colored lines in chronological order. Highly cited papers are highlighted by corresponding colored boxes. Following the significant progress in the past years, this field will embrace great advancement in the upcoming years.

Table 1.

Summary and comparison of the existing reviews on the studies of protein–RNA interaction. Sorted by the published year, the reviews are divided into different categories based on their main focuses: CLIP, RNA-binding sites, 3D structural information, DNA-binding specificity, RNA–protein interaction data and RNA-binding preferences

| Paper | Year | Journal | Main Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| [66] | 2012 | Nature Review Genetics | State-of-the-art Ultraviolet CLIP |

| [67] | 2018 | Molecular Cell | Rationale for each step in CLIP protocol and discuss the impact of variations technologies |

| [6] | 2019 | Nucleic Acids Research | Assessment of RNA SS and CLIP in detail |

| [13] | 2021 | Nature Reviews Methods Primers | Prospect of integrating data obtained by CLIP |

| [19] | 2015 | PLOS Computational Biology | Comprehensive assessment on RNA-binding sites prediction from multiple web servers, datasets, and protein-nucleic acid complexes |

| [62] | 2015 | International Journal of Molecular Sciences | Computational approaches for RBPs and RNA-binding sites prediction |

| [68] | 2016 | Biophysical Reviews | 3D structure of protein–RNA complexes at the atomic resolution |

| [69] | 2017 | Nature Reviews Molecular Biology | The coupling of RNA modifications and structures describe RNA–protein interactions at different steps of the gene expression process |

| [70] | 2018 | Genes | Computational methods for macromolecular docking and for scoring 3D structural models of ribonucleoprotein complexes |

| [1] | 2013 | Nature Biotechnology | Systematical comparison of protein’s DNA-binding specificity |

| [3] | 2016 | Briefing in Bioinformatics | RNA- or DNA-binding residues from protein sequences |

| [20] | 2019 | Bioinformatics | Deep learning architectures for predicting DNA- and RNA-binding specificity |

| [42] | 2015 | Briefings in Functional Genomics | Integrating RNA–protein interaction data with observations of post-transcriptional regulation |

| [71] | 2019 | Journal of Biological Chemistry | Statistical inference and machine-learning approaches for RBPs prediction, analysis of large-scale RNA–protein interaction datasets |

| [26] | 2019 | Protein and Peptide Letters | Computational predictors for RNA–protein interaction in the aspects of data, prediction, and input features |

| [63] | 2020 | Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews:RNA | RNA interactions with proteins and techniques measuring the kinetic dynamics of RNA–protein interactions in vitro |

| [4] | 2019 | Nature Methods | Comparison between RNA-centric and protein-centric experimental methods |

| [5] | 2020 | Molecular Cell | Protein–RNA molecular interactions & Software availability |

| [25] | 2020 | IEEE Access | Machine learning and deep learning approaches focusing on RNA-binding preference |

| [61] | 2020 | Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA | Prediction of RNA–protein interaction pairs and RBP binding preference |

This paper is organized as follows. In the second section, we give a clear description of the computational problems related to the interaction between proteins and RNAs. From the third section to sixth section, we review each component of the computational methods targeting against the above problems, including datasets (third section), features (fourth section), models (fifth section) and model evaluation (sixth section). In the seventh section, we provide a thorough review on the challenges and opportunities in this field. Although we emphasize on the importance of structural information to the interaction, for the completeness of this review, we also mention the methods only utilizing sequence encoding.

2 Computational problems for protein–RNA interaction

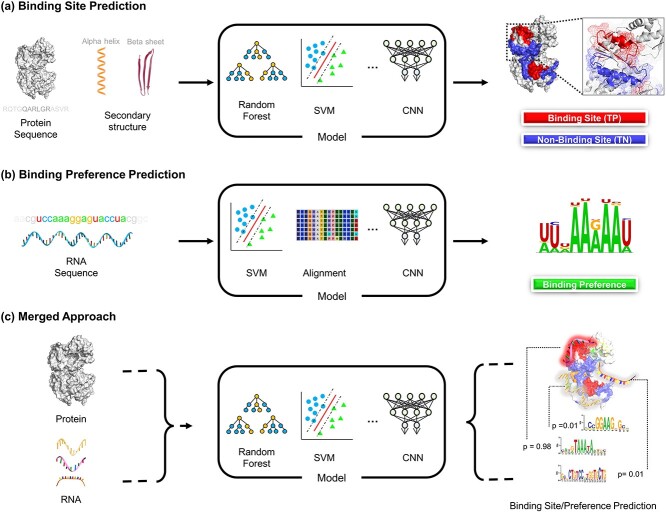

In this section, we are going to introduce the two kinds of computational problems related to the interaction between proteins and RNAs in detail. As discussed in the Introduction, we refer to the first one as the binding sites prediction and the second one as the binding preference prediction. We summarize the paradigms in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The different paradigms of studying the interactions between proteins and RNAs. A. Binding site prediction. Given the protein information, people predict which locations on the protein surface are the binding sites for RNAs. B. Binding preference prediction. For a given protein, the researchers have already determined the RNA sequences that can bind to the protein by experiments. Here, the models learn the statistical information from the input RNA sequences as the binding preference of that specific protein against RNAs. C. For studying the interaction more comprehensively, it is more desirable to consider the protein and RNA information, including both the sequence and structural information, simultaneously and predict both binding sites and binding preference.

2.1 Binding sites prediction

This problem is related to the first problem that people want to know when investigating the protein and RNA interaction. Given a protein, we first want to know whether this protein is an RBP or not. If it is not an RBP, we could stop here and save the computational resources for other proteins. If the protein is an RBP, people further want to know which AAs on the protein sequence can potentially interact with RNAs, which is related to the function of the protein. In other words, researchers want to predict the binding sites and binding positions on the protein surface for RNAs.

Usually, for this problem, people only consider the information from the protein side. The input is a protein, with either the sequence information or the structure information, or both. Then, researchers extract some features or define certain scoring functions with the above information. A machine learning model or an alignment-based method will thus be developed accordingly with an annotated database. The outputs are binary predictions, either at the protein level or the AA level. Usually, the methods based on structure have better performance on this problem than the sequence-based methods [19], as the local structure can determine whether the protein is accessible for interaction with other molecules.

2.2 Binding preference prediction

In this computational problem, we want to know more information about the interaction from the RNA side. The interaction involves two molecules, a protein, and an RNA. In the Section Binding sites prediction, we have investigated it from the protein side, determining which AAs can potentially interact with RNAs. In this problem, we study which RNAs can interact with a certain protein. If we describe the problem from the protein aspect, we want to know the binding preference of the protein against RNAs.

Although we want to predict the binding preference of an RNA-binding protein (RBP), seldom would researchers include the protein information in the prediction model. Usually, the training data are a set of RNA sequences or RNA SSs, which are proved to interact with a protein. Then, a machine learning model or a statistical motif model will be constructed based on the data. The inputs of these models are RNA features, and the models will predict whether they can interact with the protein. Notice that, in these models, people do not use the protein information explicitly. Instead, people believe a large amount of training RNA sequences can describe the target protein implicitly. However, recent studies [17, 31] show that the protein information can be used directly to predict the interaction preference, even without the high-throughput assay data.

3 Datasets for building the models

After defining the computational problems, we need to prepare the related data, which are the foundation for building computational models to resolve the above problems. The data can be divided into two categories, either the protein/RNA sequence data or the structure data. In this section, we give an overview of the data and the related databases. We also summarize the datasets in Table 2.

Table 2.

Accessible datasets for studying the interaction between proteins and RNAs

| Type | Dataset name | Samples | Availability | Benchmark Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence dataset | doRiNA [72] | 67 RBPs | https://dorina.mdc-berlin.de/ | iONMF [73] DeepBind [2] iDeep [91] iDeepS [92] iDeepE [22] GraphProt [35] deepnet-rbp [74] deepRAM [20] |

| iCount | 17 RBPs 5996 binding sites | https://icount.readthedo-cs.io/en/latest/index.html | iONMF [73] iDeepS [92] iDeepE [22] deepRAM [20] | |

| AURA 2 [75] | 256 RBPs 224,501 binding sites | http://aura.science.unitn.it/ | RNAcommender [93] iDeepE [22] | |

| CLIPdb [76] | 395 CLIP-seq 111 RBPs | http://clipdb.ncrnalab.org/ | deepnet-rbp [74] | |

| Protein structure dataset | PDB | 179,206 protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org | NucleicNet [17] aPRBind [45] GraphBind [48] |

| NPIDB | 8140 protein structures | https://npidb.belozers-ky.msu.ru/ | NucleicNet [17] | |

| AlphaFold DB | 23,391 predicted structures(Homo sapiens), all the UniRef90 proteins (over 100 million) | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ | – | |

| RNA secondary structure dataset | bpRNA | 102,318 SSs | http://bprna.cgrb.oregonstate.edu/ | – |

| RASP | – | http://rasp.zhanglab.net | – |

3.1 Sequence datasets

The protein sequences are usually used for predicting the binding sites, whereas the RNA sequences are used for predicting the binding preference. The techniques to sequence proteins are very mature, and the resulted data are stored in UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org), which is one of the most famous databases in bioinformatics.

The techniques to investigate the proteins’ binding preference against RNAs include the in vivo RIP-seq [9] and CLIP-seq [10], and the in vitro RNACompete [11] and HT-SELEX [12]. Although their experimental techniques and protocols are very different, the basic principles are the same, that is, to identify and isolate RNAs that a protein can interact with and then sequence those RNAs. Consequently, the outputs and the data from those experiments are RNA sequences. As this review does not focus on the experimental techniques, we refer the readers to the related reviews in case the readers are interested in them [6].

In Table 2, we list the related datasets. The doRiNA [72] contains 24 experiments of 21 RBPs, which are determined by experimental protocols including PAR-CLIP (Ago/EIF2C1-4, IGF2BP1-3, PUM2, Ago2-MNase, ELAVL1, ELAVL1-MNase, ELAVL1A, ESWR1, FUS, TAF15, MOV10) and CLIP-seq (TIAL1, Ago2, ELAVL1, eIF4AIII, SRSF1). On the other hand, iCount created the iCLIP dataset for 17 RBPs with 5996 binding sites. iONMF [73] analyzed the data from iCount and doRiNA, building a unified dataset, which has been widely used in different models, including iDeepE [22], deepnet-rbp [74] and deepRAM [20].

AURA 2 [75] collects the untranslated regions (UTRs) in mRNA sequences of 67 RBPs with 502,178 binding sites. Within the dataset, the number of binding sites for different RBPs is variant. To eliminate bias from imbalance positive sample distribution, iDeepE constructed RBP-47, removing 20 RBPs with less than 2000 positive sequences. However, the RBP-47 only provides the positive UTRs sequence. For generating the negative sample, the RBP-47 selects the UTRs from other RBPs, excluding the binding sites in the target RBPs. It is different from the strategy of doRiNA, which generates the negative samples by selecting random sites excluding positive binding sites in the same gene. Intuitively, the doRiNA’s tactic would be more rational and have a lower possibility of including false-negative samples. Theoretically, the CLIP-seq experiments detect regions as the binding sites of a gene and the other regions as unbinding sites, which means that experiments have verified the negative samples.

CLIPdb [76] is a database of various high-resolution binding sites for RBPs, collecting from published CLIP-seq data. It contains manually curated annotations from CLIP-seq studies acrossdifferent organisms with 395 CLIP-seq samples for 111 RBPs. In addition, CLIPdb also provides genome-wide binding sites for each dataset by a unified analysis. The resulted high-resolution binding site data from a large number of RBPs will benefit investigations on the coordination and competition of RBP binding mechanism. Because the binding sites of RBPs are identified by CLIP-seq and well-annotated in CLIPdb, its negative sampling setting is similar to that of doRiNA.

3.2 Structure datasets

Protein structure: For the protein structure, the most comprehensive database is Protein Data Bank (PDB; https://www.rcsb.org). Although the database does not contain the structure of all the RBPs and some parts of the RNAs may not be very clear, most of the existing structure datasets are extracted from structures of protein–RNA complexes from PDB [77]. Generally, the criterion of the AA in the protein being considered as RNA-binding in a co-crystal complex, is that at least one of its backbone atoms or side chains are within a certain distance from atoms of the RNA. Specifically, both 3.5Å and 5.0Å are the usual threshold [3].

Nucleic Acid-Protein Interaction Database (NPIDB) [78] collects structural information of all the DNA–protein and RNA–protein complexes available from PDB. The dataset followed the classification by the binding nucleic acids such as RNA (668), DNA (1671), RNA and DNA (504). On the other hand, ccPDB [79] provides a dataset of DNA/RNA-interacting proteins, including 417 DNA binding proteins and 282 RBPs, and identifies their DNA/RNA-interacting residues. In addition, ccPDB collects nucleotide–protein interactions such as ATP–, GTP–, NAD–, FAD–protein interactions, which may have the parallel physicochemical mechanism with RNA–protein interaction. RNA_T dataset [3] is also a benchmark dataset collected from PDB, which consists of 981 RBP chains with the distance cutoff of 3.5Å} (985 for 5Å). To alleviate the effect of chain replicates induced by strand truncation, the authors establish a dataset by removing chains with high sequence and structural similarities. The resulted dataset contains 175 representative and non-redundant (nr) RBP chains.

Meanwhile, homologous protein structures may cause bias in modeling. NucleicNet [17] has defined two homologous redundancy, internal redundancy and external redundancy. The internal redundancy is that multiple copies of the same RBP chain can exist within the same PDB entry due to the formation of homo- or hetero-multimeric complexes. The external redundancy is that homologous chains are shared across different PDB entries and dedicated to different binding RNA sequences. These redundant RNA-binding samples, sharing the homologous chains common in RNA-binding configurations and physicochemical environments, would introduce bias to the evaluation and cause the overstated generalizability power of the model. To remove the internal redundancy, the authors retain the best locally resolved component and discard the other homologous protein and RNA. For the external redundancy, PDB entries are clustered into groups where each entry is linked with others that share at least one RNA-binding chain with cutoff = 90% BLASTClust sequence homology [80]. For each cluster, the PDB entry with the best resolution is selected, turning the 483 valid PDB entries into 158 clusters. The authors select one representative entry for each cluster.

With the appearance of AlphaFold, Jumper et al. [58] provide AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, which contains 23,391 protein structures (Homo sapiens) and covers 98.5% of human proteome. Although it is a method of ab initio protein structure prediction, AlphaFold can already achieve a similar prediction accuracy and resolution as Cryo-EM on some proteins. This means structures of RBPs that have not been successfully resolved by experimental approaches may have already been predicted accurately by AlphaFold.

RNA SS: Although most of the developed binding preference prediction methods

only utilize the predicted SS, such as RNAstructure [81] or SPOT-RNA [82], to improve the

prediction performance, there are datasets containing the experimentally determined RNA

structures and in vivo profiles. Sun et al. [14] introduce in vivo click Selective

-hydroxyl acylation and profiling

experiment (icSHAPE) [83] to characterize the

single- and double-stranded regions of RNAs, which is crucial information to protein–RNA

interaction. Recently, RNA Atlas of structure probing (RASP) [84] collects transcriptome-wide RASP data through 18 experimental

methods such as DMS-seq, SHAPE-Seq, SHAPE-MaP, icSHAPE, etc.

-hydroxyl acylation and profiling

experiment (icSHAPE) [83] to characterize the

single- and double-stranded regions of RNAs, which is crucial information to protein–RNA

interaction. Recently, RNA Atlas of structure probing (RASP) [84] collects transcriptome-wide RASP data through 18 experimental

methods such as DMS-seq, SHAPE-Seq, SHAPE-MaP, icSHAPE, etc.

Intuitively, the experimental and well-annotated RNA SS provide precise and informative input to modeling. For instance, bpRNA [85] collects 102,318 known SSs from 7 different databases, including Comparative RNA Web Site [86], tmRNA Database [87], Signal Recognition Particle Database [88], Sprinzl tRNA Database, RNase P Database [89], RNA Family Database [90] and PDB. Besides, bpRNA introduces a novel annotation tool to parse complex pseudoknot-containing RNAs with seven annotations, such as stems, internal loops, bulges, multi-branched loops, external loops, hairpin loops and pseudoknots. Furthermore, bpRNA offers a high-quality subset of the database with sequence similarity lower than 90% identity, which helps the model solve the issue of training data replicates.

4 Model inputs and structure encodings

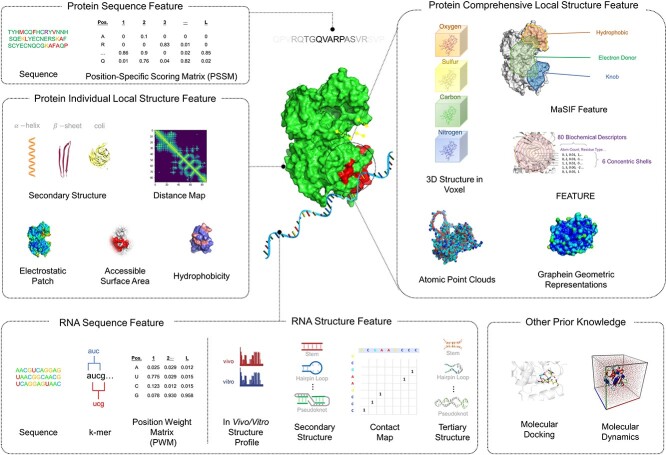

The feature and representation of the protein and RNA molecules are crucial for the downstream prediction performance. In this section, we summarize the commonly used encodings of protein and RNA features, including both sequence encoding and structure encoding. We also use Figure 3 and Table 3 as a summary.

Figure 3.

Summary of features from proteins and RNAs, as well as prior knowledge, that can be used to study the interaction between the two molecules.

Table 3.

Summary and comparison of the representative works for studying the protein–RNA interaction. A more comprehensive list is in the Appendix

| Paper | Year | Prediction | Model | Feature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature encoding format | Feature Information | ||||

| [134] | 2004 | Binding site | Fully-connected NN | Feature vector | Sequence composition, sequence neighbourhood, SA |

| [40] | 2006 | Binding preference | PWM | Single-stranded motif finding | RNA sequence and SS |

| [38] | 2010 | Binding preference | PWM | Learning a motif model to build structure annotations | RNA sequence and SS |

| [28] | 2013 | Binding site | Clustering, maximum voting | Structure alignment | Binding-specific substructure, sequence profile |

| [35] | 2014 | Binding preference | SVM | Graph-kernel | RNA sequence and SS |

| [135] | 2014 | Binding site | artificial neural network (ANN) | Feature vector | Sequence, evolutionary conservation, surface deformations, SA, side chains |

| [2] | 2015 | Binding preference | CNN | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence |

| [39] | 2016 | Binding preference | PWM | k-mer embedding | RNA SS |

| [50] | 2016 | Binding preference | Multimodal deep belief networks (DBNs) | Restricted Boltzmann machines, replicated softmax | RNA sequence, SS, tertiary structure |

| [41] | 2017 | Binding site | HMM and logistic regression | PSSM and feature vector | AA sequence, SS, SA, putative intrinsic disorder and evolutionary information |

| [136] | 2017 | Binding site | 3D CNN | 3D Voxel | Protein 3D structure with atom properties |

| [92] | 2018 | Binding preference | CNN+LSTM | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence and SS |

| [30] | 2018 | Binding site | Docking | Structure modeling | Sequence and structure |

| [22] | 2018 | Binding preference | Global and local CNN | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence |

| [137] | 2018 | Binding preference | CNN+RNN | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence and SS |

| [47] | 2019 | Binding site | 3D CNN | 3D Voxel | Atom types, Van der Waals radii |

| [17] | 2019 | Binding site and preference | CNN | Feature vector | Physicochemical characteristics of protein structure surface |

| [34] | 2020 | Binding preference | SVM | k-mer embedding | RNA sequence and structure |

| [48] | 2021 | Binding site | GNN | Graph, feature vector | Pseudo-positions, atomic features, SS, evolutionary conversation |

4.1 RNA sequence encodings

One-hot encoding: The RNA sequence can be encoded into a 4

L matrix, of which columns

correspond to the presence of

L matrix, of which columns

correspond to the presence of  and

and  (padding, if necessary) [94]. Given an RNA

sequence

(padding, if necessary) [94]. Given an RNA

sequence  with

with

nucleic acids, and the one-hot encoding

matrix M for the sequence is:

nucleic acids, and the one-hot encoding

matrix M for the sequence is:

|

(1) |

where  is the index of nucleic acids;

is the index of nucleic acids;

is an ordered list of

is an ordered list of

. For the padding sequences,

the four nucleic acids are assumed to be equally distributed and

. For the padding sequences,

the four nucleic acids are assumed to be equally distributed and  is for the padding

nucleotide

is for the padding

nucleotide  in the one-hot matrix.

in the one-hot matrix.

k-mer embedding: The RNA sequence is split into overlapping

-mers [38] of length

-mers [38] of length  using a sliding window with stride

using a sliding window with stride

. The frequency of each

. The frequency of each

-mer will be directly used as the feature,

leading to the loss of contextual information. Subsequently, the word2vec [95] algorithm was applied to extract the additional

contextual feature of

-mer will be directly used as the feature,

leading to the loss of contextual information. Subsequently, the word2vec [95] algorithm was applied to extract the additional

contextual feature of  -mer. The word2vec method is an

unsupervised learning algorithm that maps

-mer. The word2vec method is an

unsupervised learning algorithm that maps  -mers from the vocabulary

to vectors of real numbers in a low-dimensional space. The embedding representation of

-mers from the vocabulary

to vectors of real numbers in a low-dimensional space. The embedding representation of

-mers is computed in such a way that their

context is preserved, i.e. word2vec produces similar embedding vectors for

-mers is computed in such a way that their

context is preserved, i.e. word2vec produces similar embedding vectors for

-mers that tend to co-occur or be similar.

Generally, the

-mers that tend to co-occur or be similar.

Generally, the  -mer representation is more informative

than one-hot encoding [74, 96], whereas the word2vec algorithm provides contextual

information by learning the statistical information of

-mer representation is more informative

than one-hot encoding [74, 96], whereas the word2vec algorithm provides contextual

information by learning the statistical information of  -mer

co-occurrence relationships in the input sequences.

-mer

co-occurrence relationships in the input sequences.

4.2 RNA structure encoding

RNA SS: RNA SS offers the local and geometric patterns in two approaches, depending on whether there is an available protein–RNA complexes structure in the PDB. If the structure is available, the explicit SS can be calculated by using an assignment approach, such as RNAstructure [81]. If the structure is unavailable, the predicted SS can be obtained by using a SS prediction algorithm, such as SPOT-RNA [82], RNAshapes [97] and E2Efold [98]. For the RNA SS stored in bpRNA [85], bpseq file reveals the base pair connection of the RNA.

In vivo structure profile: RNA in vivo

structure profile is produced by icSHAPE [14],

which is used to characterize the single- and double-stranded regions of RNAs [99]. The raw data of icSHAPE can be processed by the

bioinformatic tool, icSHAPE-pipe [100]. In

brief, raw reads are first collapsed to delete Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) duplicates,

and the adapters are trimmed. Next, the clean reads are mapped to the human genome using

STAR with the default parameters. Then, icSHAPE scores can be calculated using

icSHAPE-pipe, resulting in a  matrix with the value ranging

from 0 to 1.

matrix with the value ranging

from 0 to 1.

Tertiary structure: Once given the RNA sequence and the corresponding secondary structural information, JAR3D [101] can align possible tertiary structural motifs to R3DMA [102], which contains 253 representative hairpin loop motifs and 276 representative internal loop motifs. For encoding RNA tertiary structure, the target RNA sequence is first predicted into the probable SS using RNAshapes [97]. Then, all the hairpin and internal loops that overlap the viewpoint region would be fed to JAR3D to calculate the probabilities of folding into the predefined tertiary structural motifs. Subsequently, RNA tertiary structure can be encoded into a binary vector of 529 dimensions, corresponding to 253 hairpin loop motifs and 276 internal loop motifs in the R3MDA.

4.3 Protein sequence encoding

One-hot encoding: The protein sequence can be encoded into a

x

x matrix,

of which columns correspond to the presence of 20 standard AAs, such as

matrix,

of which columns correspond to the presence of 20 standard AAs, such as

The encoding process is similar

to that of RNA.

The encoding process is similar

to that of RNA.

Pseudo AA composition: To consider the order information of protein sequence, researchers introduced pseudo-AA composition[103] to represent AAs composition information and AAs order information. It is a combination of a set of discrete sequence correlation factors and the 20 components of the conventional AA composition.

Position-specific scoring matrix: PSSM [104] introduces evolutionary information into the RNA-binding site prediction.

PSSM quantifies the conservation of residues, as the binding residues are shown to be

conserved in the sequence. The encoding can be conducted by PSI-BLAST [105], where the query sequence is aligned to the NCBI nr sequence

database, resulting in a matrix of  . Each value in

the matrix represents the frequency of a specific AA at a particular position in the

multiple sequence alignment [106, 107].

. Each value in

the matrix represents the frequency of a specific AA at a particular position in the

multiple sequence alignment [106, 107].

4.4 Protein structure encoding

Local structure: Individual local structural information included SS [40], interface propensity (IP) [108], accessible surface area (ASA) [109], electrostatic patches (EP) [110] and distance map (DM) [111]. The SS reveals primary structural information, which has 3/8-class

labeling systems. Dictionary of SS of protein [112] assigns eight SS states to AAs, including  -helix G, alpha-helix H, pi-helix I,

beta- bridge B, beta-strand E, beta-turn T and coil C. SPIDER3 [109] converts the 8-class assignment into the 3-class assignment,

where Helix H is composed of G, H and I; Beta strand B is composed of B and E; Coil (C) is

composed of T and C. Li et al. [108] introduce IP, the residue-nucleotide propensities with SS information of

proteins and RNAs. The propensity of a specific residue-nucleotide pair is calculated from

its observed probability at interfaces divided by its expected probability. The IP of a

residue type with a particular class of SSs is represented as an average value of its

pairwise propensities for the four kinds of nucleic acids. ASA is a kind of widely used

feature for RNA-binding site prediction, which can be calculated by NACCESS [113] when the protein structure is available in PDB.

For the protein absent in the PDB, there are several predictive methods, such as ASAquick

[114] and RNAsol [115] to predict ASA. EP can describe the protein surface charge

status, which is an important factor in RNA-binding process. Generally, RNA-binding

interfaces on protein are more likely to be positively charged, and the electrostatic

feature can be calculated by PatchFinderPlus [116]. DM can efficiently represent contacted structural information by

residue-pairwise distance matrix, which can be calculated by SPOT-Contact [117]. DM has been applied for protein profile

prediction, such as solubility [118] and DTI

[53].

-helix G, alpha-helix H, pi-helix I,

beta- bridge B, beta-strand E, beta-turn T and coil C. SPIDER3 [109] converts the 8-class assignment into the 3-class assignment,

where Helix H is composed of G, H and I; Beta strand B is composed of B and E; Coil (C) is

composed of T and C. Li et al. [108] introduce IP, the residue-nucleotide propensities with SS information of

proteins and RNAs. The propensity of a specific residue-nucleotide pair is calculated from

its observed probability at interfaces divided by its expected probability. The IP of a

residue type with a particular class of SSs is represented as an average value of its

pairwise propensities for the four kinds of nucleic acids. ASA is a kind of widely used

feature for RNA-binding site prediction, which can be calculated by NACCESS [113] when the protein structure is available in PDB.

For the protein absent in the PDB, there are several predictive methods, such as ASAquick

[114] and RNAsol [115] to predict ASA. EP can describe the protein surface charge

status, which is an important factor in RNA-binding process. Generally, RNA-binding

interfaces on protein are more likely to be positively charged, and the electrostatic

feature can be calculated by PatchFinderPlus [116]. DM can efficiently represent contacted structural information by

residue-pairwise distance matrix, which can be calculated by SPOT-Contact [117]. DM has been applied for protein profile

prediction, such as solubility [118] and DTI

[53].

For the comprehensive local structural information, atom features within concentric

shells or grid boxes are introduced to describe the physicochemical environment in a

specific physical space, which can be calculated by FEATURE [119] or AutoDock [120].

In FEATURE, 80 physicochemical properties (e.g. negative/positive charges, hydrophobicity,

SA) on atoms of the protein with 7.5Å of a grid point in a radial distribution are divided

into six concentric shells of spheres, resulting in a  matrix. AutoDock utilizes an

atom-channel (carbon-, oxygen-, nitrogen-, sulfur-) framework to define a local 20Å

cubical box to state the presence of carbon, oxygen, sulfur and nitrogen atoms in a

corresponding atom type channel, divided into 1Å cubical voxel, resulting in a

matrix. AutoDock utilizes an

atom-channel (carbon-, oxygen-, nitrogen-, sulfur-) framework to define a local 20Å

cubical box to state the presence of carbon, oxygen, sulfur and nitrogen atoms in a

corresponding atom type channel, divided into 1Å cubical voxel, resulting in a

matrix.

MaSIF [121], dMaSIF [122] and Graphein [123]

apply geometric deep learning on protein structure surface. MaSIF emphasizes the

significance of the protein surface, and presents a method to encode geometric features

(shape index and distance-dependent curvature) and chemical features (hydropathy,

continuum electrostatics and free electrons/protons) on the surface with the geodesic

radius of 9Å or 12Å, resulting in a

matrix.

MaSIF [121], dMaSIF [122] and Graphein [123]

apply geometric deep learning on protein structure surface. MaSIF emphasizes the

significance of the protein surface, and presents a method to encode geometric features

(shape index and distance-dependent curvature) and chemical features (hydropathy,

continuum electrostatics and free electrons/protons) on the surface with the geodesic

radius of 9Å or 12Å, resulting in a  matrix.

Instead of using surface mesh, dMaSIF employs atomic point cloud representation to extract

task-specific geometric and chemical features. Graphein is an efficient tool for

constructing graph and surface-mesh representation of protein structures.

matrix.

Instead of using surface mesh, dMaSIF employs atomic point cloud representation to extract

task-specific geometric and chemical features. Graphein is an efficient tool for

constructing graph and surface-mesh representation of protein structures.

Global structure: Global structural information is rarely used in RNA-binding site prediction since the interaction is regarded as a local recognition problem. However, global structural information may play an important role in identifying RBP in future applications. Ishiguro et al. [124] introduce supernodes to connect other nodes in the graph representing the compound structure. Proteins with the neighbor-radius contact map could be encoded in a similar way [125].

5 Computational models

After encoding the proteins and RNAs, we need to build and train a model to perform the interaction prediction. We divide the methods into two categories, either template-based and shallow-learning methods or deep learning methods, which will be introduced in detail in this section. Table 3 also summarizes the models of different representative works.

5.1 Template-based and shallow-learning models

The template-based approach, which is similar to homology modeling, is applied for the binding site prediction with known homologous structures. The models, such as DBD-Threader [126] and SPOT-Seq [82], can directly adopt the known knowledge without feature extraction and mainly rely on the protein structure alignment process. However, for the protein without known homologous structure, the approach is incapable of solving this situation. It is hard for the template-based approach to copy specific sites from few homologous cases. On the other hand, the shallow-learning methods attempt to generalize common rules learned from the known experience of a dataset [3]. Because of their satisfactory performance and good interpretability, shallow-learning approaches, such as SVM, random forest, logistic regression, decision tree and naïve Bayes, have been widely used in RNA-binding sites and binding preference prediction [36, 43]. Although shallow-learning methods are very powerful in terms of interpolation, the prediction of extrapolation can not be guaranteed since the predefined feature limits the module learning from the raw data. The predefined feature provides a explicit but fixed insight of the learning module. However, with the increasing amount of data, the feature extraction procedure can be flexible and learned by the model, so-called deep learning. Generally, deep learning methods yield higher performance of the binding site and binding preference prediction, especially for sophisticated protein [2]. It will be introduced in the following section in detail. On the other hand, several works, including RNABindRPlus [127] and RBRDetector [128], are attempting to incorporate both template-based and shallow-learning approaches to improve the performance.

5.2 Deep learning models

The existing methods emphasize the importance of sequence information. DeepBind [2] is the first deep learning approach for RNA-binding

preference prediction, which employs a single layer of convolution. DeepBind demonstrates

the powerful capability of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) as well as their ability

to detect the known motifs. DeepBind takes only the RNA sequences as inputs and identifies

the preference of RBPs. Based on DeepBind, DeeperBind [129] introduces the long short-term memory (LSTM) layers into the DeepBind

architecture to learn the long-range dependency between the sequence features extracted by

the CNN layers. iDeepS [92] also combines CNN and

recurrent neural network (RNN) layers since both of them are helpful for performance, and

extra RNA structural motifs are also integrated into the model. iDeepE [22] feeds the local and global sequence information into CNNs,

and demonstrates that multiple overlapping fixed-length sub-sequences (similar to

-mer) provide informative feature for the

binding preference prediction. DeepRAM [20]

comprehensively evaluates the model based on CNNs, RNNs, and hybrid CNN/RNN architectures,

revealing that the hybrid frameworks outperform the former two architectures. Besides,

DeepCLIP [49] also employs 1D convolution layers

and bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) to capture the mutation profile of protein–RNA binding

preference. However, single input of sequence limits the model capacity to capture the

authentic mechanism of RNA–protein interaction.

-mer) provide informative feature for the

binding preference prediction. DeepRAM [20]

comprehensively evaluates the model based on CNNs, RNNs, and hybrid CNN/RNN architectures,

revealing that the hybrid frameworks outperform the former two architectures. Besides,

DeepCLIP [49] also employs 1D convolution layers

and bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) to capture the mutation profile of protein–RNA binding

preference. However, single input of sequence limits the model capacity to capture the

authentic mechanism of RNA–protein interaction.

With the developing insight of RNA–protein interaction, RNA structural information is

discovered to exerts an important role in the binding mechanism. Thus, in order to predict

binding site, deepnet-rbp [50] utilized a

multi-modal deep learning framework. It systematically integrated RNA primary sequences,

predicted SSs from RNAshapes, and tertiary structural features extracted by JAR3D. As for

RNA-binding preference prediction, DLPRB [130]

also took the advantage of the predicted SSs to explore RNA structural contexts. The

PrismNet [14] considered that there are a large

number of structurally variable sites across the cell lines. Consequently, icSHAPE [100] was introduced in PrismNet to describe the

in vivo structural profile with  matrix (see the section In

vivo structure profile). The PrismNet encodes the sequence with the one-hot

encoding and extra in vivo structure scores as the fifth dimension.

Besides, PrismNet applied a squeeze-and-excitation module [131] to adaptively calibrate convolutional channels of

channel-wise attention and residual blocks, and capture the joint sequence-and-structural

binding determinants.

matrix (see the section In

vivo structure profile). The PrismNet encodes the sequence with the one-hot

encoding and extra in vivo structure scores as the fifth dimension.

Besides, PrismNet applied a squeeze-and-excitation module [131] to adaptively calibrate convolutional channels of

channel-wise attention and residual blocks, and capture the joint sequence-and-structural

binding determinants.

In addition, the protein local structural environment of the binding sites is also crucial to the RNA–protein interaction. Torng and Altman [47] applied 3D CNNs to protein structure information, generated by AutoDock or FEATURE, and provided the comparable performance as the former RNA–protein interaction binding site prediction method. Furthermore, NucleicNet [17] considered the RNA-binding issue from the perspective of three-dimensional protein structure, which is extracted in units of residues. In order to extract RNA-binding properties in various locations on protein structure, the FEATURE [132] framework is used to encode physicochemical properties on the grid point of protein surfaces. For each viewpoint, a high-dimensional feature vector for six concentric shells of spheres with 80 physicochemical properties for each shell will be generated. Furthermore, the NucleicNet predictor used the hierarchical classification of residue sites, first for binding or not, if affirmative, the possible type of RNA constituent binding to the location.

To efficiently capture such structural information of RNA and protein local environment, many studies applied graph neural networks (GNNs) to extract the comprehensive features. RPI-Net [96] employed an end-to-end learning approach with GNN from the sequences and structures of RNAs, which provide dense information for binding site prediction. For the graph construction of protein structural context, GraphBind [133] defined a sliding sphere in the 3D space for the target residue and applied a Hierarchical GNN to learn the latent patterns of structural and physicochemical characteristics for binding residue recognition.

6 Model evaluation

After building the model, the last step is evaluating the performance of the model to help the users understand the usefulness and weak points of the propose methods. In this section, we summarize the commonly used evaluation criteria in this field.

6.1 Cross-fold and cross-dataset validation

Cross-fold (3-, 5-, 10-fold) validation is usually used to evaluate the performance of models with metrics of the area under the receiver operating characteristic and F1 score. For the 10-fold cross-validation, the dataset would be divided into 10-folds, and for each time, 9-folds of them are used for training while the left one is for testing. One problem is that many works are evaluated using data within a specific protein category, indicating that the models only learn protein-specific features instead of general binding features, which limits the application of the models. To assess the generalizability of the model, people should also use cross-dataset validation, which means that general models should be established and evaluated with protein data from different categories and different sources [20].

6.2 Structure visualization

The specific patterns inferred from these models can be visualized as the sequence logo diagrams (Weblogo [138]) for the RBP. Generally, these patterns can be regarded as the RNA motifs, which can be mapped to the RNA-binding motif dataset, CISBP-RNA (8056 records of RBP binding motifs) [139]. Besides, the RNA-binding motifs with particular SSs, including stems, multiloops, hairpins, internal loops, and dangling, are prone to access the surface of RBPs. Thus, the structural information extracted from the model can explain their binding tendency.

6.3 In vitro and in vivo experimental validation

RNAcompete assay (RNAC) [140] is a large-scale

in vitro experiment that uses the epitope-tagged RBP to competitively

select RNA sequences from a designed pool. In NucleicNet [17], the authors obtain 7-mer RNA-binding profiles summarized as

a  -score for the individual RNA sequence. The

RBPs with both available RNAC data and PDB structure, such as PABPC1, PCBP2, PTBP1,

RBFOX1, SNRPA, SRSF2, TARDBP and U2AF2, are tested. The results suggest that NucleicNet is

capable of differentiating between the top and bottom ten sequences indicated by RNAC

Z-scores. Thus, RNAC is suitable to evaluate the model performance. In

vivo experimental validation in PrismNet [14] is to distinguish the relevant affinity of the given RBPs, such as SND1 with

specific conformation (hairpin) or single-stranded conformation. With different

melting-and-folding treatments to perturb RNA structure without altering the sequence, the

authors can obtain two conformations of the given RNA, the one refolding into the hairpin

structure and the other retaining single-stranded conformation. PrismNet predicts that a

double-stranded binding site for SND1, which is consistent with the in

vivo affinity experiment.

-score for the individual RNA sequence. The

RBPs with both available RNAC data and PDB structure, such as PABPC1, PCBP2, PTBP1,

RBFOX1, SNRPA, SRSF2, TARDBP and U2AF2, are tested. The results suggest that NucleicNet is

capable of differentiating between the top and bottom ten sequences indicated by RNAC

Z-scores. Thus, RNAC is suitable to evaluate the model performance. In

vivo experimental validation in PrismNet [14] is to distinguish the relevant affinity of the given RBPs, such as SND1 with

specific conformation (hairpin) or single-stranded conformation. With different

melting-and-folding treatments to perturb RNA structure without altering the sequence, the

authors can obtain two conformations of the given RNA, the one refolding into the hairpin

structure and the other retaining single-stranded conformation. PrismNet predicts that a

double-stranded binding site for SND1, which is consistent with the in

vivo affinity experiment.

7 Challenges and opportunities

We may encounter several challenges when modeling the interaction between proteins and RNAs. In terms of the inputs to the models, we need to think of how to encode structural information more efficiently and even considering the dynamic structural information. Regarding the model, we should design novel deep learning models, which can process multi-modality data effectively, including the information from proteins and RNAs, as well as our prior knowledge. Furthermore, people also care about the model interpretability, that is, what leads the model to make a specific prediction. Revisiting the protein–RNA interaction problem and advancement in the related fields, we may want to resolve some more sophisticated but appealing tasks. For instance, because of the recent breakthrough in the protein structure prediction field, it becomes increasingly possible to perform high-resolution Ab initio protein–RNA interaction prediction with only the protein sequence information. Finally, based on the predicted interaction results, people are also eager to design specific molecules with high binding affinity against the target molecule. In this section, we discuss the challenges and the potential opportunities in this field in detail.

7.1 Structure encodings

As discussed above, structural information is critical to predicting the protein–RNA interaction accurately. However, how to encode the structural information efficiently remains to be an open question. Because deep learning models are also useful to perform feature selection, when encoding the structural information, we should try to preserve as much raw information as possible, especially the spatial information.

Regarding the protein structure, some traditional ways of encoding, such as 3/8-class protein SS, lose too much raw information. FEATURE [17], defining shells around a location in the 3D space and summarizing the physicochemical properties within each shell, is another popular method. However, using such an encoding, we cannot differentiate the properties within each shell. In the machine learning field, people usually use 3D voxels, point clouds, and polygon mesh to represent 3D objects. 3D voxel encoding is similar to the 2D pixel. And it was shown to be better than FEATURE in predicting the functional domain of proteins [47]. However, because we extend the representation to another axes, we need to design a more efficient algorithm for handling the increasing dimension. Polygon mesh representation collects vertices, edges, and faces to define the surface of the protein structure. The combination of such a representation and geodesical CNN is shown to extract the fingerprint of the protein surface, which can be used to predict the interaction between different molecules [121]. Point cloud methods sample points from the 3D object, using the coordinates of those points to represent the structure of the object. Although it has not been widely applied in this field, it has shown great power in the computer vision field for 3D object classification and segmentation.

In terms of the RNA structure, people usually use the SS profile to encode them, indicating whether each base is single-strand or double-strand. However, this encoding loses too much information. For example, we would not know which base forms the hydrogen bond with the other specific base. Recently, researchers have shown that predicting the RNA SS by predicting the contact map matrix can boost the performance significantly [98]. A similar idea can be applied to the protein–RNA interaction prediction. Meanwhile, using the graph to represent the RNA SS is another natural approach [96]. However, we need to specify which information we want to extract from the graph. In addition, a thermodynamic study revealed the vital role of non-canonical bases in RNA structure formation and stability [141]. For example, in the non-canonical base purine, hydrogen replaces the exocyclic amino group of Adenine. This replacement leads to the Purine-Uracil pair containing only one hydrogen bond instead of two hydrogen bonds in the Adenine-Uracil pair, which could affect the stability of the structure. Ideally, these ubiquitous non-canonical bases should be included in structure encoding.

Despite the specific encoding that we may use from the machine learning field, we still need to consider the chemical background of the problem. The structures in the atom-scale are different from the 3D objects in real life. Although we may use rigid bodies to approximate and model them, they are not rigid bodies. The physicochemical properties [17] should be considered when we design the methods.

7.2 Dynamic structure information

Another fundamental property of biomolecules that most machine learning methods fail to consider is their dynamics. As we know, biomolecules are not static, rigid bodies. Every part of the molecule is continuously moving and oscillating in high frequency. The apo protein structures would not stay in the state with the lowest energy all the time. Instead, they may change from one sub-optimal state to another from time to time. When it comes to the interaction between two molecules, such as the interaction between proteins and RNAs, the situation will be even more complex. For example, some molecules, such as Argonaute, need to undergo substantial conformation change to bind to RNA sequences. The other proteins may also have conformation changes once incorporating RNAs. This phenomenon leads to two difficulties when we model the protein–RNA interaction. Firstly, the structure database that we rely on is not perfect for providing the structural information that we need. Simply removing the RNA structure from the protein–RNA complex may not reveal the actual protein apo structure. Secondly, failing to model molecule dynamics may lead to the performance degradation of the machine learning method when we apply the method to real-life problems. To resolve the above challenges, we should use both the PDB structures and the information from molecular dynamic simulation. In practice, we may consider the state of a molecule at each time point as a screenshot. The entire protein dynamics trajectory can be considered as a video. Deep learning techniques to process videos, such as multi-instance learning, would be helpful to resolve this challenge.

7.3 Incorporating prior knowledge

In addition to the data, researchers have accumulated expertise and prior knowledge about this problem. For example, we know that Aquifex aeolicus Ribonuclease III (Aa-RNase III) is most likely bind with double-stranded RNAs. Incorporating such knowledge into the machine learning model can further boost the model’s prediction performance and usefulness. There are multiple ways to achieve that. We can manipulate the data prepared for training the model by up-sampling the class favored by the prior knowledge. When we train the model, such knowledge could be incorporated into the model implicitly. But we should handle the data carefully to avoid overfitting. On the other hand, we may design a specific machine learning model that explicitly incorporates prior knowledge. For example, by embedding constraint optimization as a module into the deep learning model [98], we can reduce the data size requirement for training a deep learning model.

7.4 Using information from both RNA and protein

In the previous studies, when predicting the binding sites on the protein surface, people usually only use the information from the protein. On the other hand, researchers often only use the RNA information when modeling the protein’s binding preference to the RNA sequences. Because the interaction is related to both molecules, it is more desirable to consider both when modeling the process. However, as protein and RNA are different molecules, it is not reasonable to use just one deep learning model to process them. Instead, we should use multi-modality models. Essentially, for each molecule, we have a deep learning module to extract features from it. Then, the features can be combined to perform the final prediction. In practice, we may pre-train each module separately first and then fine-tune all the modules together in an end-to-end fashion. By considering the two molecules simultaneously, we do not have to train a model for each protein, and we are more likely to obtain one general model, which deciphers the principle behind protein–RNA interaction.

7.5 Model interpretability for structural modeling

It is always difficult to explain deep learning models. For the bio-molecular sequence analysis, after the investigation in the past few years, people have proposed a number of methods to explain the prediction of deep learning models [44, 142, 143]. Such explanations converge with the motif discovery techniques before the surge of deep learning. However, for the prediction at the structure level, the explanation is much more difficult. In the structure field, we encounter a serious dilemma between explanation and performance, no matter utilizing deep learning or not. For example, those methods with a strong physicochemical foundation and carefully designed force fields usually have inferior performance compared with the machine learning-based methods. Before the wide usage of deep learning in this field, threading and similarity-based methods are also often used. Although such methods cannot handle queries without homologs, researchers know when they will work and when they will not. However, after deep learning methods are applied to this field, people will use them by default because of their superior performance, although researchers cannot explain what physicochemical and structural biology knowledge are used by the model to perform the prediction. Currently, the request for model interpretability in the structure field is not very urgent because people were still struggling with the performance before the appearance of AlphaFold2 [58]. However, with the fast performance improvement, it is foreseeable that the demand for an explanation of the model will soon increase. The model explanation techniques from the machine learning field can be used to identify, which input features influence the final prediction. However, such an explanation is too trivial for this field. Building the connection between the feature and the biological insight would be a more interesting problem, requiring more effort from the researchers.

7.6 High-resolution prediction

When predicting the binding sites on the protein surface, researchers usually annotate at the amino acid (AA) level. Regarding the binding preference against the RNA sequences, the resolution is usually until the nucleotide. From the structural aspect, the above prediction resolution is still too low. In reality, when studying the interaction between proteins and RNAs, we want to know the exact binding pocket and even the binding location on the protein and RNA surface. With such information, we can understand the functional mechanisms of those important proteins, such as Ago and CRISPR-associated proteins. Some recent works are trying to increase the resolution of the prediction [17, 121]. More works can be done to improve the existing methods further. For example, although Lam et al. [17] generate grid points on the protein surface and predicts at the grid point level, which increases the prediction resolution significantly on the protein side, the authors have not considered the information from the RNA side at all. Consequently, the method is unable to determine the sequence and orientation of the binding RNA precisely. Introducing features from the RNA structure should increase the prediction resolution for the RNA, although the entire framework needs to be redesigned. As discussed in the previous sections, with more advanced structural encoding techniques and frameworks considering both protein and RNA information, the prediction resolution would be increased significantly in the near future.

7.7 Ab initio prediction

Currently, when predicting the interaction between proteins and RNAs with structural information, people usually assume that we have already known the protein structure. However, in reality, determining the protein and RNA structure is not a trivial task. Even if we can determine the structure of molecules in nature by biological experiments, it is almost impossible to resolve the structure of molecules with mutations, which is important for drug discovery and development. Under that circumstance, it is desirable that we can predict everything from the protein and RNA sequences, which is referred as Ab initio prediction here. With the sequences, we may first predict the 3D structures of proteins and RNAs. Then, based on the predicted structures, we will further predict their interactions. Although this research paradigm seems to be computational daunting and may accumulate errors in the multiple steps, it becomes increasingly appealing with the rapid development of the protein structure prediction algorithms in recent years. For example, AlphaFold2 [58] can already achieve a similar prediction accuracy and resolution as Cryo-EM on some proteins. For RNAs, recently proposed deep learning-based method, namely, Atomic Rotationally Equivariant Scorer [144], has significantly improved prediction of RNA structures. Eventually, we can use one end-to-end deep learning model to address the two steps all at once. If we could predict the structural interaction details only using the sequence information, gene regulation and drug discovery investigation will be accelerated significantly.

7.8 From prediction to design

After determining the molecular structure, we want to know the molecular function, that is, how a specific molecule can interact with another. However, only investigating their function is not our ultimate goal. Eventually, we want to design particular molecules with desirable functions so that to resolve the problems that we encounter in real life, such as curing diseases. As the performance of prediction models has been improved significantly in recent years, researchers are increasingly interested in designing. For instance, people have been using deep learning to optimize the CRISPR guide RNA design [145, 146]. Deep learning has also shown its power in designing new antimicrobial peptide [147]. Regarding this specific topic of protein–RNA interaction, people are especially interested in designing RNA sequences with high binding affinity to protein, similar to the CRISPR guide RNA designing mentioned above. Moreover, a suitable guide RNA for Ago can also increase the gene knock-down efficiency [17]. In addition to the commonly used generative models, such as generative adversarial network (GAN) [148] and variational auto-encoder [149], recently, differentiable algorithms [98] and energy models [150] have drawn great attention in the machine learning field, which is potentially useful for designing problems in the protein–RNA interaction field.

8 Conclusion

The interactions between different molecules are essential for biological processes in our body. Among them, the RBP–RNA interactions are of great interest to researchers, considering their central role in gene expression regulation [1, 151]. People have developed a number of computational tools and methods to facilitate the study of the RBP–RNA interaction, usually predicting the binding sites and binding preference. However, as we discussed in detail in the review, because of the limitation of the previous data, researchers usually only consider the sequence information and auxiliary structural information to perform the prediction. Considering the recent progress of AlphaFold and the tremendous amount of structure data produced by it [60], the study of the RBP–RNA interactions will be promoted significantly by deep learning methods [17, 152] operating directly on the structure data.

Funding

The work was supported by the Fund of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (4937025, 4937026, 5501517, 5501329); King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). [BAS/1/1624-01, FCC/1/1976-23-01, FCC/1/1976-26-01, REI/1/0018-01-01, REI/1/4216-01-01, REI/1/4437-01-01, REI/1/4473-01-01, URF/1/4098-01-01, REI/1/4742-01-01].

Appendix Table

Table 4.

A comprehensive summary and comparison of the representative works for studying the protein–RNA interaction

| Paper | Year | Prediction | Model | Feature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature encoding format | Feature Information | ||||

| [134] | 2004 | Binding site | Fully-connected NN | Feature vector | Sequence composition, sequence neighbourhood, SA |

| [40] | 2006 | Binding preference | PWM | Single-stranded motif finding | RNA sequence and SS |

| [38] | 2010 | Binding preference | PWM | Learning a motif model to build structure annotations | RNA sequence and SS |

| [28] | 2013 | Binding site | Clustering, maximum voting | Structure alignment | Binding-specific substructure, sequence profile |

| [135] | 2014 | Binding site | ANN | Feature vector | Sequence, evolutionary conservation, surface deformations, SA, side chains |

| [35] | 2014 | Binding preference | SVM | Graph-kernel | RNA sequence and SS |

| [29] | 2014 | Binding site | Decision tree | Score ranking | Electrostatic and evolutionary features of residues |

| [2] | 2015 | Binding preference | CNN | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence |

| [39] | 2016 | Binding preference | PWM | k-mer embedding | RNA SS |

| [32] | 2016 | Binding preference | Template | Sequence, structure alignment and transformation matrix | Sequence and structure |

| [43] | 2016 | Binding site | Random Forest | Euclidean distance | Electrostatic feature, triplet interface propensit, PSSM, geometrical and physicochemical properties |

| [50] | 2016 | Binding preference | Multimodal DBNs | Restricted Boltzmann machines, replicated softmax | RNA sequence, SS, tertiary Structure |

| [41] | 2017 | Binding site | HMM and logistic regression | PSSM and feature vector | AA sequence, SS, SA, putative intrinsic disorder and evolutionary information |

| [23] | 2017 | Binding preference | Deep boosting | k-mer embedding | RNA sequence |

| [136] | 2017 | Binding site | 3D CNN | 3D Voxel | Protein 3D structure with atom properties |

| [153] | 2017 | Binding preference | CNN | PSSM and k-mer embedding | Protein and RNA sequence |

| [36] | 2017 | Binding site | SVM | Feature vector | Physicochemical and evolutionary information of protein sequences |

| [92] | 2018 | Binding preference | CNN+LSTM | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence and SS |

| [154] | 2018 | Binding preference | Greedy search | k-mer embedding | RNA sequence and structure |

| [30] | 2018 | Binding site | Docking | Structure modeling | Sequence and structure |

| [22] | 2018 | Binding preference | Global and local CNN | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence |

| [30] | 2018 | Binding site | CNN | Feature Vector | Hydrophobicity, normalized van der Waals volume, polarity, polarizability, charge and polarity of side chain |

| [37] | 2019 | Binding site | SVM | PSSM and feature vector | Protein sequence and structure |

| [137] | 2018 | Binding preference | CNN+RNN | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence and SS |

| [155] | 2019 | Binding preference | CNN | k-mer embedding and one-hot encoding | RNA sequence and SS |

| [47] | 2019 | Binding site | 3D CNN | 3D Voxel | Atom types, Van der Waals radii |

| [156] | 2019 | Binding preference | Capsule Network[157] | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence and SS |

| [17] | 2019 | Binding site and preference | CNN | Feature vector | Physicochemical characteristics of protein structure surface |

| [158] | 2020 | Binding preference | Recommendation system | FastText[159] | Protein and RNA sequence |

| [160] | 2020 | Binding preference | Alignment | PSSM | RNA sequence and SS |

| [45] | 2020 | Binding site | CNN | PSSM and feature vector | Sequence, structure, IP, physicochemical, topology, evolutionary properties and residue fluctuation dynamics |

| [96] | 2020 | Binding preference | GNN | One-hot encoding, k-mer embedding and PSSM | RNA sequence and SS |

| [34] | 2020 | Binding preference | SVM | k-mer embedding | RNA sequence and structure |

| [49] | 2020 | Binding preference | CNN+BiLSTM | One-hot encoding | RNA Sequence |

| [48] | 2021 | Binding site | GNN | Graph, feature vector | Pseudo-positions, atomic features, SS, evolutionary conversation |

| [14] | 2021 | Binding preference | SENet[131] | One-hot encoding | RNA sequence and SS |

Abbreviations Definitions

Table 5.

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| AA | Amino acid |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional LSTM |

| CLIP | Crosslinking and immunoprecipitation |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| DBN | Deep belief network |

| DM | Distance map |

| DTI | Drug-target interaction |

| EP | Electrostatic patches |

| GAN | Generative adversarial network |

| GNN | Graph neural network |

| icSHAPE | in vivo click Selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation and profiling experiment |

| IP | Interface propensity |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| MPNPs | Message passing neural processes |

| NPIDB | Nucleic Acid-Protein Interaction Database |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| PSSM | Position-specific scoring matrix |

| PWM | Position weight matrix |

| RASP | RNA atlas of structure probing |

| RBP | RNA-binding protein |

| RNAC | RNAcompete assay |

| RNN | Recurrent neural network |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| UTRs | Untranslated regions |

Junkang Wei is a master student in Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). His research interest focuses on protein-molecule interaction and drug discovery.

Siyuan Chen is a Ph.D. candidate in Computer Science at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). His research lies in the intersection between computer science and biology.

Licheng Zong is a Ph.D. candidate in Computer Science and Engineering at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). His research concentrates on the intersection between deep learning and bioinformatics.

Xin Gao is a Professor at Computational Bioscience Research Center (CBRC), King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). His research group focuses on bioinformatics, computational biology, machine learning, and big data.

Yu Li is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). His research group focuses on the intersection between machine learning, healthcare and bioinformatics, developing novel machine learning methods to resolve the computational problems in biology and healthcare, especially the structured learning problems.

Contributor Information