Abstract

Topical menthol-based analgesics increase skin blood flow (SkBF) through transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) receptor-dependent activation of sensory nerves and endothelium-derived hyperpolarization factors. It is unclear if menthol-induced TRPM8 activation mediates a reflex change in SkBF across the dermatome in an area not directly treated with menthol. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of localized topical menthol application on SkBF across a common dermatome. We hypothesized that SkBF would be increased with menthol at the site of application and across the dermatome (contralateral limb) through a spinal reflex mechanism. In a double blind, placebo controlled, cross-over design, 15 healthy participants (7 men; age=22±1 yrs) were treated with direct application (3 ml over 8×13 cm) of 5% menthol gel (Biofreeze™) or placebo gel on the L4 dermatome, separated by 48 hours. Red blood cell flux was measured using laser Doppler flowmetry over the area of application, on the contralateral leg of the same dermatome, and in a separate dermatome (L5/S1) to serve as control. Cutaneous vascular conductance was calculated for each measurement site (CVC=flux/MAP). At baseline there were no differences in CVC between menthol and placebo gels, or among sites (all p>0.05). After 30±6 minutes, CVC increased at the treated site with menthol (0.12±0.02 vs. 1.36±0.19 flux/mmHg, p<0.01) but not the placebo (0.10±0.01 vs. 0.18±0.04 flux/mmHg, p=0.91). There was a modest increase in CVC at the contralateral L4 dermatome with menthol gel (0.16±0.04 vs. 0.29±0.06 flux/mmHg, p<0.01), but not placebo (0.11±0.02 vs. 0.15±0.03 flux/mmHg, p=0.41). There was no effect on SkBF from either treatments at the the L5/S1 control dermatome (both, p>0.05), suggesting the lack of a systemic response. In conclusion, menthol containing topical analgesic gels increased SkBF at the treated site, and modestly throughout the dermatome. These data suggest menthol-induced activation of the TRPM8 receptors induces an increase in SkBF across the area of common innervation through a localized spinal reflex mechanism.

Keywords: cross-over effect, cross-limb effect, menthol analgesics, skin blood flow

INTRODUCTION

The cross-limb effect, also known as cross-education and the cross-over effect, was first observed in 1894 and continues to be investigated as a clinical tool for a variety of treatments including, pain management, injury rehabilitation, and strength training (Hendy and Lamon, 2017). This phenomenon occurs when a stimulus elicits a response not only on the treated limb, but also on the contralateral untreated limb. For example, Jay et al. (2014) observed that utilizing a unilateral massage treatment for delayed onset muscle soreness resulted in a decreased soreness, not only in the massage-treated leg, but also the contralateral untreated leg, suggesting a cross-limb effect occurred (Jay et al., 2014). Specific mechanisms mediating this response are unclear; however, it has been postulated that there are central pathways involved (Hendy and Lamon, 2017; Ruddy and Carson, 2013). This physiological phenomenon has been observed with a number of stimuli including, acupuncture, electrical stimulation, skill and strength trainings (Farthing, 2009; Huang et al., 2015; Jay et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2010; Ruddy and Carson, 2013; Stöckel et al., 2016; Veldman et al., 2015). However, it is unknown if it occurs with the application of topical menthol containing analgesics.

Topical menthol containing analgesic gels are commonly used for the management of pain, a mechanism likely mediated through gate control mechanisms (Melzack, 1996). Menthol activates transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) receptors. When activated, TRPM8 receptors depolarize thermosensitive afferent nerves (McKemy et al., 2002). This results in the perception of a coolness sensation without an actual decrease in temperature (Binder et al., 2011; Lasanen et al., 2016). Furthermore, TRPM8 activation directly and indirectly inhibits nociceptors, masking pain sensations (Garrett, 2004; Janeen and Ken, 2002; Liu et al., 2013; Premkumar and Abooj, 2013). Our laboratory has shown that topically applied menthol containing gels elicit a coolness sensation for up to an hour after application (Craighead and Alexander, 2016). This sensation is accompanied by an increase in cutaneous blood flow. Immediately following application, blood flow rapidly increases, peaks at about 30 minutes, and remains elevated for ~45 minutes (Craighead and Alexander, 2016). The increase in cutaneous blood flow is mediated in part by nitric oxide, endothelium derived hyperpolarizing factors, and sensory nerves (Craighead et al., 2017).

Sensory nerves are anatomically classified into thirty distinct dermatomes where each dermatome is innervated by a common spinal nerve (Whitman and Adigun, 2020). Menthol-induced cutaneous vasodilation is partially mediated by sensory nerves in the direct area of application. However, it is unclear if this effect is present across the dermatome in areas where menthol is not in direct contact with the skin. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine if menthol application would elicit a cross-limb effect in the same area of sensory innervation. It was hypothesized that the application of a menthol containing gel would increase cutaneous blood flow and neurosensory thresholds for nociceptors in the contralateral, untreated area of the same dermatome.

METHODS

All participants completed the study protocol after providing written and oral informed consent. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of Pennsylvania State University and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects were apparently healthy, recreationally active (≥150 min/week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity), nonsmokers, and did not present with any chronic disease, including past or present peripheral nerve damage.

An adapted American Society of Heating Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) thermal sensation visual analog scale, which presented a spectrum of temperature sensations from cold to hot, was used to measure perceptive thermal sensation (Gilani et al., 2015). Participants were shown this scale and asked to directly mark their current sensation of temperature. Cutaneous blood flow was measured via laser Doppler flowmetry (VP12; Moor Instruments, Wilmington, DE and normalized to mean arterial pressure via automated brachial artery cuff (Connex Spot Monitor; Welch Allyn, Skaneateles Falls, NY) as cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC = flux/mmHg). At the sites of cutaneous blood flow measurement, local skin temperature was held constant throughout the protocol at 33°C (SH02 and VHP2; Moor Instruments, Wilmington, DE). Finally, in a subset of participants (n=9) a neurometer (Neurotron Inc., Baltimore, Maryand USA) was used to measure current perception thresholds (CPT) (Katims et al., 1989; Takekuma et al., 2000). Three nerve fibers were targeted: unmyelinated C fibers (dull pain and temperature sensations, 5Hz), myelinated Aδ fibers (pain, temperature, and pressure sensations, 250 Hz) and myelinated Aβ fibers (touch, pressure, and cold sensations, 2000 Hz) (Inceu and Veresiu, 2015). The intensity of the transcutaneous transmitted frequency was slowly increased until the participant indicated the onset of a tingling sensation, signifying the neurosensory threshold. The average of three thresholds was taken for each targeted nerve fiber. Thermal sensation and CPT measurements were performed on the menthol-gel treated L4 dermatome and on the contralateral untreated L4 dermatome. Cutaneous blood flow measurements were performed on the treated L4 dermatome, the contralateral untreated L4 dermatome, as well as the contralateral mid-calf in the S1/L5 dermatome to serve as a control (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic displaying experimental set up including the treated (menthol or placebo) L4 dermatome (solid blue box), the untreated contralateral L4 dermatome (striped blue box), and the control (untreated) L5/S1 dermatome (open circle). The treatments (menthol or placebo), as well as the treated and untreated legs were randomized at the first experimental visit, and kept consistent for the second visit. Figure created by BioRender.

In a double-blind randomized placebo control protocol, participants completed two experimental visits where they received a 5% menthol gel or a placebo. The placebo resembled the appearance and smell of the menthol gel, but did not contain menthol. Inactive ingredients of both gels included: aloe barbadensis leaf extract, arctium lappa root (burdock) extract, arnica montana flower extract, blue 1, boswellia carterii resin extract, calendula officinalis extract, camellia sinensis leaf extract, isopropyl alcohol, ispropyl myristate, melissa officinalis (lemon balm) leaf extract, silicia, tocopheryl acetate, triethanolamine, water, and yellow 5. Visits were separated by a minimum of 48 hours. After resting in a semi-supine position for 10 minutes, baseline cutaneous blood flow, thermal sensation, and CPT measurements were taken. Three milliliters of gel was evenly applied over an 8 by 13 cm area in the L4 dermatome, proximal and lateral to the knee (Fig 1). The treated limb was randomized and kept consistent for both experimental visits. Cutaneous blood flow was continuously recorded for 40 minutes. CPT measurements were repeated at minute 40. Thermal sensation was measured at 10, 20, and 30 minutes after gel application. All experiments were performed in a temperature controlled laboratory of 20–22°C. Participants were instructed to wear a cotton t-shirt and loose-fitting shorts to both experimental visits.

Conservatively assuming an effect size of d=1.0 (Craighead and Alexander, 2016; Craighead et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2019), we determined (power = 0.80, α = 0.05) a sample size of n=10 would be sufficient to determine a meaningful physiological difference of 10% between sites with a standard deviation of the difference of 10% (Faul et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 1986; Johnson et al., 1984). Data were recorded at 1,000 HZ and analyzed offline (Powerlab and LabChart; AD Instruments). Paired t-tests or repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to analyze group differences (IBM SPSS Statistics v25). When appropriate, Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons were performed and corrected for multiple comparisons. Effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated for main effects of treatment by calculating the mean difference between treatments divided by the standard deviation (Cohen, 2013). Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation, and significance was set a priori at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 15 young healthy participants (8W, age: 22 ± 3 years, BMI: 24 ± 2 kg/m2, heart rate: 62 ± 7 bpm) completed the study. All participants were normotensive (systolic: 113 ± 10 mmHg and diastolic: 69 ± 4 mmHg) and not taking any medication that could alter neural, cardiovascular, or metabolic function, with the exception of oral contraceptives (n=3). The phase of menstrual cycle was controlled within, but not between women participants.

Thermal sensation

All participants marked neutral/0 for baseline thermosensation for both visits and at both limbs. Post-application, both gels elicited a colder sensation on the treated leg compared to the contralateral, untreated leg (Fig 2, all p < 0.01). On the treated leg, the 5% menthol gel elicited a greater colder sensation compared to the placebo at 10, 20, and 30 minutes post-application (all p < 0.01). This cold sensation did not differ between 10, 20, and 30 minutes post-application (all p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Both placebo (open circles; 10min d=0.95, 20min d=0.57, and 30min d=0.86) and 5% menthol (closed circles; 10min d=2.04, 20min d =1.58, and 30min d =1.54) gels elicited a colder sensation on the treated leg (panel A) compared to the untreated, contralateral leg (panel B) at all time points post-application. On the treated leg (panel A), the menthol gel elicited a colder sensation compared to the placebo at all time points (10min d=1.41, 20min d=1.29, and 30min d=1.1). On the contralateral, untreated leg (panel B), there was no difference between gels. Some of the error bars cannot be seen as they are smaller than the represented mean symbol. *P < 0.01 vs. Placebo; †P < 0.01 vs. Contralateral, Untreated L4.

Cutaneous blood flow

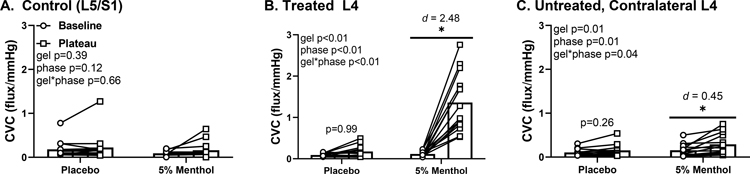

Baseline CVC did not differ between visits (p = 0.96) or sites (p = 0.38). At both the treated L4 dermatome and the untreated, contralateral L4 dermatome, CVC increased with 5% menthol treatment (Fig 3, both p < 0.01). This increase in skin blood flow started at 16 ± 5 minutes, plateaued at 30 ± 6 and persisted for the remainder of the study (40 minutes). There was no difference in CVC on the control L5/S1 dermatome for either gels (p = 0.64). Furthermore, there were no differences from pre-to-post treatment with the placebo gel on either the treated L4 (p = 0.91) or the untreated, contralateral L4 dermatome (p = 0.41).

Figure 3.

Baseline (circles) and 40 minutes post-gel application (squares) cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC). There was no difference pre-to-post treatment in the control site (panel A) for either gels. CVC increased at both the treated L4 dermatome (panel B) and the untreated, conralateral L4 dermatome with 5% menthol treatment (panel C). *p<0.01 baseline vs. plateau.

Neurosensory CPT

Baseline CPTs did not differ between visits (Table 1, all p > 0.05). Post-gel application neurosensory thresholds were not different between gels or sites for any of the targeted fiber types (Table 1, all p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Current Perception Thresholds

| Treated L4 | Contralateral, Untreated L4 | P-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Menthol | Placebo | Menthol | |||

|

| ||||||

| Unmyelinated C Fibers, 5 Hz | Baseline | 59 ± 37 | 43 ± 33 | 63 ± 47 | 41 ± 31 | Gel p=0.06 Phase p=0.23 |

| Plateau | 64 ± 42 | 53 ± 39 | 50 ± 34 | 55 ± 57 | Interaction 0.37 | |

|

| ||||||

| Myelinated Aδ, 250 Hz | Baseline | 78 ± 52 | 58 ± 46 | 74 ± 51 | 48 ± 24 | Gel p=0.20 Phase p=0.41 |

| Plateau | 79 ± 58 | 59 ± 46 | 65 ± 37 | 68 ± 50 | Interaction p=0.39 | |

|

| ||||||

| Myelinated Aβ, 2000 Hz | Baseline | 203 ± 135 | 192 ± 145 | 198 ± 91 | 201 ± 88 | Gel p=0.64 Phase p=0.64 |

| Plateau | 209 ± 136 | 181 ± 116 | 215 ± 105 | 214 ± 81 | Interaction p=0.72 | |

DISCUSSION

The main findings from this study were that topical 5% menthol based topical analgesic application (BioFreeze™) (1) elicited a cold sensation on the treated area of the dermatome but not on the untreated area of the same dermatome on the contralateral side, (2) increased cutaneous blood flow on the treated area of the dermatome and the untreated contralateral side of the same dermatome, albeit cutaneous blood flow increased to a greater extent in the area directly treated, and (3) did not alter CPTs. These data suggest menthol-induced activation of the TRPM8 receptors induces an increase in skin blood flow across the area of common innervation through a local spinal reflex mechanism.

Cold sensation

In this study, topical application of a 5% menthol-based topical analgesic elicited a cold sensation similar to what has been previously observed (Craighead and Alexander, 2016). There was a significant cold sensation reported at 10 minutes post-application that persisted throughout the 30 minutes of monitoring. The proposed mechanism for this response is the activation of TRPM8 channels on sensory nerves within the skin (Craighead and Alexander, 2016). TRPM8 receptors are polymodal non-selective cationic channels that are activated by cold between 25°C and 10°C (Buijs and McNaughton, 2020). In addition to temperature-mediated activation, TRPM8 receptors have a menthol binding site mediating the perception of a cold sensation (Xu et al., 2020). TRPM8 receptors are involved in a variety of acute and chronic pain conditions and may be downregulated with tissue injury and in the face of heightened inflammation (Andersson et al., 2004; Linte et al., 2007; Premkumar et al., 2005). Menthol-based topical analgesics are common in clinical and athletic settings, but their precise mechanism of action and how they may modulate sensory feedback across the dermatome of innervation are unclear.

Our data indicate that the application of a 5% menthol-based topical analgesic is relatively quick acting and lasts at least 30 minutes. Previously, we reported that a cooling sensation peaked at 10 minutes and was present for 5–60 minutes post-application (Craighead et al., 2017). Interestingly, in the present study the placebo gel also elicited a mild cold sensation albeit to a lesser extent compared to the 5% menthol-based gel. This is most likely attributed to evaporation of the placebo gel. We found no alterations in the thermal sensation in the contralateral untreated side of the dermatome indicating that a thermal sensation cross-limb effect does not extend to the contralateral dermatome.

Cutaneous blood flow

Similar to our prior studies, we observed an increase in cutaneous blood flow in the area of skin treated with the 5% menthol-based gel (Craighead and Alexander, 2016; Craighead et al., 2017). This rise in blood flow started at 16 ± 5 minutes, plateaued at 30 ± 6 minutes and persisted for the remainder of the study (40 minutes). The increase in cutaneous blood flow mediated directly by menthol occurs via multiple mechanisms. Our laboratory (Craighead and Alexander, 2016) has previously demonstrated that TRPM8-activation via topical menthol application increased the blood flow response to post-occlusion reactive hyperemia (PORH), an endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factors (EDHFs) and sensory nerve-mediated vasodilatory stimuli (Lorenzo and Minson, 2007). Further, concurrent topical menthol and lidocaine application, resulted in an attenuated baseline and PORH-induced vasodilation, suggesting a role of sensory nerves in menthol-mediated blood flow regulation (Craighead and Alexander, 2016). Subsequent experiments utilizing direct pharmacological inhibition via intradermal microdialysis confirmed EDHFs, sensory nerves, as well as nitric oxide, as down-stream mediators underlying TRPM8-induced vasodilation (Craighead et al., 2017).

In the present study we observed a small-to-modest (d=0.45) increase in cutaneous blood flow in the same dermatome on the contralateral limb that was not directly treated with the 5% menthol gel. We did not observe any changes in cutaneous blood flow in the control L5/S1 dermatome. To our knowledge, we are the first to examine a menthol-induced cross-limb effect on cutaneous blood flow in humans. Previous research examining the cross-limb effect has primarily investigated its impact on strength, mobility, and pain management from a variety of stimuli such as unilateral resistance training, acupuncture, and massage (Huang et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2007; Jay et al., 2014; Tillu et al., 2001; Veldman et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2012). For example, strength training cross-limb effects on average results in a strength increase in the untrained contralateral limb that is equal to a quarter to half of that of the trained one (Carroll et al., 2006). The most proposed mechanisms include central neural pathway alterations (Carroll et al., 2006). Similarly, given sensory nerve involvement in local blood flow responses to TRPM8-induced cutaneous vasodilation, we postulate cutaneous blood flow cross-limb effects are mediated via a central neural pathway. However, future experiments elucidating these mechanisms are needed.

Neurosensory CPT

There was no change in the neurosensory thresholds in response to 5% menthol application in either the treated or contralateral side of the dermatome. It is unlikely that this small application of topical menthol induced a large enough alteration in afferent activity that would result in a change in efferent outflow to the vasculature. However, our observations in the present study are limited by our methodology, as neurometers do not directly measure nerve activity. Therefore, future studies should employ more specific and direct neural measurements to determine the effect of menthol gel on nerve activity.

Conclusions/Perspectives

In summary, we found that the topical application of 5% menthol gel: (1) elicited a cold sensation on the treated, but not the contralateral untreated, dermatome, (2) increased cutaneous blood flow in both the treated dermatome and modestly in the untreated contralateral dermatome, suggesting a cross-limb effect, and (3) did not alter neurosensory CPT. The findings of this study are important when designing studies investigating topical menthol analgesics. It is common to use within-person control designs for these studies, but given the skin blood flow cross-limb effect, may be inappropriate for future study designs. When investigating the cutaneous blood flow response to a topical agent, especially if containing menthol, choosing a control site that is located in the same dermatome, whether on the ipsilateral or contralateral limb, will be problematic, as it may reflect the cross-limb effect and not represent a true non-treated control site. A control site that is located in a different dermatome would be ideal to ensure a true control response is being observed. The results of this study also have implications for clinical pain management, as menthol gel is commonly used for this purpose. If one has an invasive injury that does not permit the direct application of topical menthol analgesics, the topical menthol agent could be applied in the same dermatome to illicit an increase in skin blood flow. This response would promote healing of the injury, and potentially reduce pain. In the present study we did not observe alterations in neurosensory CPT with topical menthol gel; however, our participants were free from any skin or musculoskeletal injury at the time of testing. These results may differ if gel application and subsequent experimental testing was following an injury or during pain (e.g. muscle cramp, muscle strain, or delayed onset muscle soreness). Future studies are needed to specifically investigate the potential cross-limb effect of pain management of topical menthol analgesics.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Arthur Minahan and Rachel Pitman for their technical assistance.

Funding

provided by Performance Health and NIH T-32-5T32AG049676 (GAD)

REFERENCES

- Andersson DA, et al. , 2004. TRPM8 activation by menthol, icilin, and cold is differentially modulated by intracellular pH. Journal of Neuroscience. 24, 5364–5369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder A, et al. , 2011. Topical High-Concentration (40%) Menthol—Somatosensory Profile of a Human Surrogate Pain Model. The Journal of Pain. 12, 764–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs TJ, McNaughton PA, 2020. The Role of Cold-Sensitive Ion Channels in Peripheral Thermosensation. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll TJ, et al. , 2006. Contralateral effects of unilateral strength training: evidence and possible mechanisms. J Appl Physiol (1985). 101, 1514–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, 2013. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Craighead DH, Alexander LM, 2016. Topical menthol increases cutaneous blood flow. Microvasc Res. 107, 39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead DH, et al. , 2017. Mechanisms and time course of menthol-induced cutaneous vasodilation. Microvasc Res. 110, 43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farthing JP, 2009. Cross-education of strength depends on limb dominance: implications for theory and application. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 37, 179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, et al. , 2009. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 41, 1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett WE Jr., 2004. Cold gel reduced pain and disability in minor soft-tissue injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 86, 1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilani S, et al. , 2015. Thermal Comfort Analysis of PMV Model Prediction in Air Conditioned and Naturally Ventilated Buildings. Energy Procedia. 75, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Hendy AM, Lamon S, 2017. The Cross-Education Phenomenon: Brain and Beyond. Frontiers in physiology. 8, 297–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L-P, et al. , 2015. Unilateral intramuscular needling can improve ankle dorsiflexor strength and muscle activation in both legs. Journal of exercise science and fitness. 13, 86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LP, et al. , 2007. Bilateral effect of unilateral electroacupuncture on muscle strength. J Altern Complement Med. 13, 539–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inceu GV, Veresiu IA, 2015. Measurement of current perception thresholds using the Neurometer((R)) - applicability in diabetic neuropathy. Clujul Med. 88, 449–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeen MH, Ken DS, 2002. Acute Effect of 2 Topical Counterirritant Creams on Pain Induced by Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. 11, 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jay K, et al. , 2014. Specific and cross over effects of massage for muscle soreness: randomized controlled trial. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 9, 82–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JM, et al. , 1986. Effect of local warming on forearm reactive hyperaemia. Clin Physiol. 6, 337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JM, et al. , 1984. Laser-Doppler measurement of skin blood flow: comparison with plethysmography. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 56, 798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katims JJ, et al. , 1989. Current perception threshold. Reproducibility and comparison with nerve conduction in evaluation of carpal tunnel syndrome. ASAIO Trans. 35, 280–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasanen R, et al. , 2016. Menthol concentration in topical cold gel does not have significant effect on skin cooling. Skin Res Technol. 22, 40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, et al. , 2010. The ipsilateral motor cortex contributes to cross-limb transfer of performance gains after ballistic motor practice. J Physiol. 588, 201–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linte RM, et al. , 2007. Desensitization of cold- and menthol-sensitive rat dorsal root ganglion neurones by inflammatory mediators. Experimental Brain Research. 178, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, et al. , 2013. TRPM8 is the principal mediator of menthol-induced analgesia of acute and inflammatory pain. Pain. 154, 2169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo S, Minson CT, 2007. Human cutaneous reactive hyperaemia: role of BKCa channels and sensory nerves. The Journal of physiology. 585, 295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKemy DD, et al. , 2002. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature. 416, 52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R, 1996. Gate control theory: On the evolution of pain concepts. Pain Forum. 5, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar LS, Abooj M, 2013. TRP channels and analgesia. Life Sci. 92, 415–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar LS, et al. , 2005. Downregulation of transient receptor potential melastatin 8 by protein kinase C-mediated dephosphorylation. Journal of Neuroscience. 25, 11322–11329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy KL, Carson RG, 2013. Neural pathways mediating cross education of motor function. Front Hum Neurosci. 7, 397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöckel T, et al. , 2016. Motor learning and cross-limb transfer rely upon distinct neural adaptation processes. Journal of neurophysiology. 116, 575–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekuma K, et al. , 2000. Age and gender differences in skin sensory threshold assessed by current perception in community-dwelling Japanese. J Epidemiol. 10, S33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillu A, et al. , 2001. Unilateral versus bilateral acupuncture on knee function in advanced osteoarthritis of the knee--a prospective randomised trial. Acupunct Med. 19, 15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldman MP, et al. , 2015. Direct and crossed effects of somatosensory electrical stimulation on motor learning and neuronal plasticity in humans. European journal of applied physiology. 115, 2505–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman PA, Adigun OO, Anatomy, Skin, Dermatomes. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing StatPearls Publishing LLC., Treasure Island (FL), 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ST, et al. , 2019. Sunscreen or simulated sweat minimizes the impact of acute ultraviolet radiation on cutaneous microvascular function in healthy humans. Exp Physiol. 104, 1136–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, et al. , 2020. Molecular mechanisms underlying menthol binding and activation of TRPM8 ion channel. Nature Communications. 11, 3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, et al. , 2012. Bilateral effects of 6 weeks’ unilateral acupuncture and electroacupuncture on ankle dorsiflexors muscle strength: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 93, 50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]