Visual Abstract

Abstract

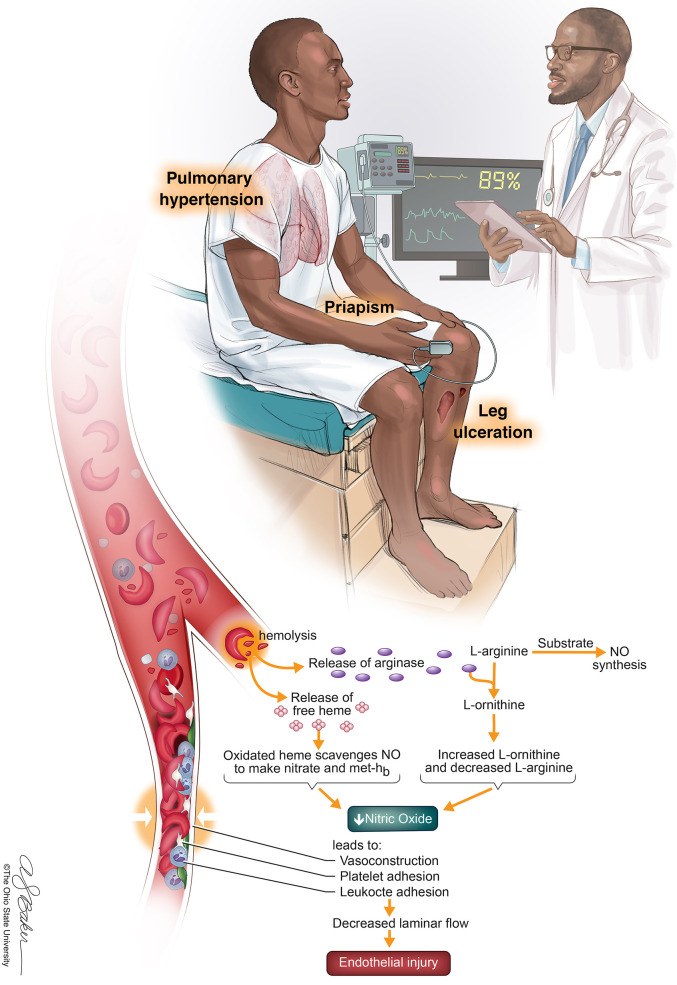

Sickle cell disease is a disorder characterized by chronic hemolytic anemia and multiorgan disease complications. Although vaso-occlusive episodes, acute chest syndrome, and neurovascular disease frequently result in complication and have well-documented guidelines for management, the management of chronic hemolytic and vascular-related complications, such as priapism, leg ulcers, and pulmonary hypertension, is not as well recognized despite their increasing reported prevalence and association with morbidity and mortality. This chapter therefore reviews the current updates on diagnosis and management of priapism, leg ulcers, and pulmonary hypertension.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate the types of priapism presenting in patients with SCD and understand current therapeutic and preventative regimens

Understand phenotypic presentation of and current therapeutic options for chronic leg ulcerations

Be familiar with the current screening, diagnostic, and therapeutic recommendations for pulmonary hypertension in SCD

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a β-hemoglobinopathy that is hallmarked by red blood cell (RBC) sickling and chronic hemolytic anemia. Point mutations in both β-globin genes lead to an unstable hemoglobin molecule (HbS),1 which polymerizes into chains to form a “sickled” shape. This ultimately causes vaso-occlusion, intravascular hemolysis, and endothelial dysfunction. Although the complications of SCD are broad, there are recognized overlapping “subphenotypes” of the disease. The high hemoglobin/high viscosity subtype is associated with increased episodes of acute chest syndrome (ACS) and vaso-occlusive episodes (VOEs),2 whereas the hyperhemolytic subtype is associated with increased vascular complications such as priapism, leg ulceration, and pulmonary hypertension.2-4 This chapter reviews the definitions, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of those vascular complications.

CLINICAL CASE

A 24-year-old man with SCD (genotype hemoglobin SS) presents to a clinic to establish care with an adult hematologist. He followed regularly with his pediatric hematologist and is currently taking hydroxyurea, folic acid, and cholecalciferol. His SCD-related complications include elevated transcranial Doppler velocity, 3 episodes of ACS, and once-yearly VOE hospitalizations. At today's visit, he reports new episodes of painful, intermittent erections that occur about 4 nights per week and last about 3 to 4 hours. They awaken him from sleep and sometimes resolve with rigorous exercise.

Priapism

Definition, types, prevalence, and pathophysiology

Priapism is defined as an erection lasting greater than 4 hours. Priapism can occur in patients with SCD of all ages but may peak between 20 and 25 years of age.5 In SCD, increased RBC sickling occurs within the corpus cavernosa, possibly as a result of abnormal endothelial adherence, relative acidosis during sleep and during erection, and deficient erection control mechanisms involving an impaired nitric oxide–cyclic GMP pathway.6 Priapism is characterized as low flow (ischemic) or high flow (nonischemic/arterial). Nonischemic priapism is caused by trauma and damage to the cavernosal artery and is not a urologic emergency as there is no lasting damage to penile tissue. Ischemic priapism, however, can cause lasting tissue damage and requires prompt urologic evaluation. When ischemic priapism lasts less than 4 hours and recurs, it is referred to as stuttering. Both stuttering and ischemic priapism are described as painful, which can help differentiate them from nonischemic priapism.7

Management

Although increased hydration and pain management can be attempted for priapism lasting less than 4 hours,8 first-line therapy for acute ischemic priapism is decompression via aspiration, followed by intracavernous injection (ICI) of sympathomimetic agents.7,9 Penile blood is then sent for blood gas testing to confirm etiology, although in patients with SCD, it is often ischemic. Sympathomimetics work via α-mediated vasoconstriction within the corpus cavernosa, and urologic data suggest that aspiration plus ICI is more effective than aspiration alone.7 These data were supported in a prospective study of 15 patients with sickle cell anemia.8

RBC exchange transfusions have also been shown to be safe and effective in both acute and preventative management of priapism.10 There have been previously described adverse effects characterized by cerebral vascular events ( Association of SCD, priapism, exchange transfusion, and neurological events syndrome) in this setting,11,12 but it is thought to be more related to posttransfusion hemoglobin and associated increased viscosity, rather than the actual transfusion itself.

Although no other therapies have been shown to be effective in large trials for the acute management of priapism, case reports suggest some therapies may be effective in the preventative setting. A 2017 Cochrane review analyzing the data on these therapies, which included ephedrine, sildenafil, stilboestrol, and etilefrine, found no difference in efficacy between treatment and placebo in the prevention of recurrent priapism.13 Oral sympathomimetics such as ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and etilefrine work systemically via the same mechanism as sympathomimetic ICI. Other proposed therapies disrupt the abnormal nitric oxide–cGMP pathway and include phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors such as sildenafil and tadalfil. Although some case reports support their use for reduction in recurrence with long-term dosing,13,14 the data on the use of sildenafil in pulmonary hypertension (PH) raise concern for increased VOEs with its use.15 Hormonal therapies suppress androgenic effects on penile erection9 and include GNrH agonists, estrogens, antiandrogens, and ketoconazole. Despite reported success in preventing recurrent priapism events, significant adverse effects include erectile dysfunction, mood changes, and hot flashes and potential for cardiovascular complications.9,14 Baclofen, a selective γ-aminobutyric acid receptor agonist, was effective in treatment for sleep-related priapism in a UK cohort study but was not effective in the SCD cohort.14

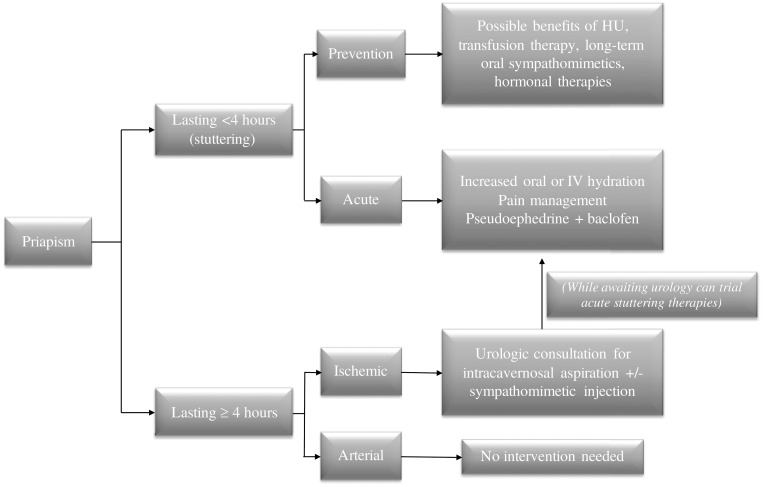

Although none of these therapies have been investigated for detumescence in acute priapism episodes, they have been anecdotally used with some success. The combination of pseudoephedrine and baclofen has been particularly effective in some patients within our practice and can be trialed while awaiting (but should not delay) urology consultation (Figure 1). Regarding the mainstays of SCD therapies, the direct effect of hydroxyurea on priapism has not been well studied. There are, however, case reports suggesting hydroxyurea and transfusion are beneficial in preventing recurrent episodes of stuttering priapism.16,17

Figure 1.

How I treat priapism. For episodes lasting greater than 4 hours, urgent urologic consultation for prompt aspiration +/- sympathomimetic injection is recommended. For stuttering episodes, it is reasonable to attempt increased hydration and pain management. Long-term oral sympathomimetics may be beneficial in the prevention of recurrent episodes, as well as therapy with hydroxyurea (HU) or chronic transfusions. Hu, hydroxyurea; IV, intravenous.

Novel therapies

A phase 2 single-arm trial is currently investigating the efficacy and safety of crizanlizumab in the management of SCD-related priapism (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03938454). Crizanlizumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting the leukocyte adhesion modulator P-selectin and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019 to reduce VOEs in SCD.2

CLINICAL CASE (Continued)

The patient is diagnosed with stuttering priapism and is started on daily baclofen for prevention. The frequency of episodes decreases over 2 years, and he remains clinically stable for the next 10 years. However, he now reports a new, recurrent wound on his inner right ankle.

Leg ulcers

Definition, types, prevalence, and pathophysiology

The prevalence of sickle cell leg ulcers (SCLUs) is unknown, but many patients report their first ulcer by the second decade of life. The proposed pathophysiology in SCD involves predisposing vasculopathy, local skin insult, pain-mediated neurogenic inflammation, and low tensile strength of scar tissue.3 SCLUs are often located in the lower extremities, specifically where there is poor circulation, thin skin, and less subcutaneous fat (eg, perimalleolar).3,4 Ulcers can be singular, stuttering, or chronic and frequently recur at the site of previous ulcerations. A distinguishing feature from other venous ulcers is the presence of pain.3 Prior trauma is a potential predisposing factor.3,18 Other associated factors include HbSS genotype,3,19 male sex, age older than 20 years, and reduced hemoglobin F (HbF) levels.19 There has been prior debate in the literature as to the role of hydroxyurea and predisposition to SCLUs. However, several large reviews have disputed this. Of the 505 patients being screened for pulmonary hypertension, 39% were taking hydroxyurea. There was no statistical difference in prevalence of leg ulcers among patients with and without hydroxyurea.20

Management

There are various proposed interventions for SCLUs, including pharmaceutical treatments (vascular, antioxidants, growth factors, HbF synthesis stimulators), topical treatments (wound care, antibiotics, growth factors, steroids), and surgical/nonpharmaceutical agents. A 2020 Cochrane review found 6 randomized control trials (RCTs) investigating these therapies.4 One study investigating isoxsuprine, a vascular agent, had mixed results when evaluating complete ulcer closure. Of the 30 patients, only 23.9% healed (of those, 63.6% treatment vs 36.4% placebo), 36.9% had improved ulcers (47% treatment vs 53% placebo), 15.2% had no change, and 23.9% had deterioration of ulcers.4,21 Arginine butyrate, an HbF stimulator, demonstrated 30% complete closure compared with 8% in the standard local care arm.4,22

Wound care

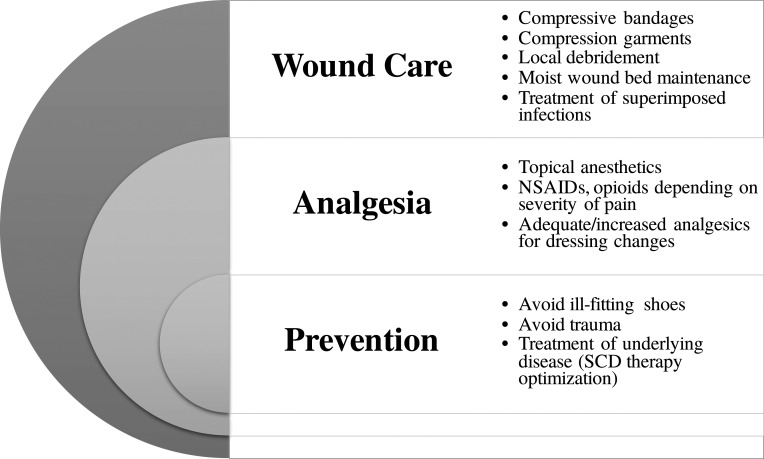

Local wound care is crucial to treating SCLUs and involves debridement, infection control, and maintenance of a moist wound environment.19 Appropriate compressive bandages and garments (eg, stockings) and Unna boots are important in maintaining a moist environment for healing (Figure 2). Topical antibiotics are not routinely recommended due to risk of contact sensitization, bacterial resistance, and lack of moisture balance.19

Figure 2.

Multimodal approach to SCLUs. The treatment of leg ulcers requires comprehensive wound care, adequate analgesics, and preventative measures. NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Pain management

SCLUs cause significant pain and morbidity, and management should include adequate analgesic therapy. Topical anesthetics may be used, but severe pain frequently warrants opioid therapy. Neuropathic pain may respond to selective serotonin receptor inhibitors, pregabalin, gabapentin, or tricyclic antidepressants. Given the chronicity of some ulcers, they may require chronic, not just acute, regimens.19

Transfusions

Chronic transfusions decrease HbS percentage, RBC sickling, and hemolysis-related pathology. Transfusions have been used in both acute and preventative settings19 for SCLUs and as perioperative support for patients who require surgery.3 There are no RCTs to determine goal hemoglobin, HbS percentage, or duration of therapy. Generally, a 6-month trial is used to evaluate for response, and if the response is positive, transfusions are continued until complete ulcer closure.18

Novel therapies

A phase 2 triple-blind RCT assessing the tolerability and efficacy of topical sodium nitrate is under way (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02863068), after the 2014 phase 1 cohort trial results were promising and demonstrated a significant increase in periwound blood flow, as well as dose-dependent decreases in SCLU size.23

In addition, a double-blind RCT is evaluating the safety and efficacy of intradermal deferoxamine patches (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04058197).

CLINICAL CASE (Continued)

Our patient's ulcer completely resolved with wound care and a short transfusion protocol. He required a 6-month dose increase in his chronic pain regimen and did not have any further recurrences over the past 6 years. At his office visit today, he notes worsening dyspnea with regular activities and increasing fatigue.

Pulmonary hypertension

Presentation and diagnosis

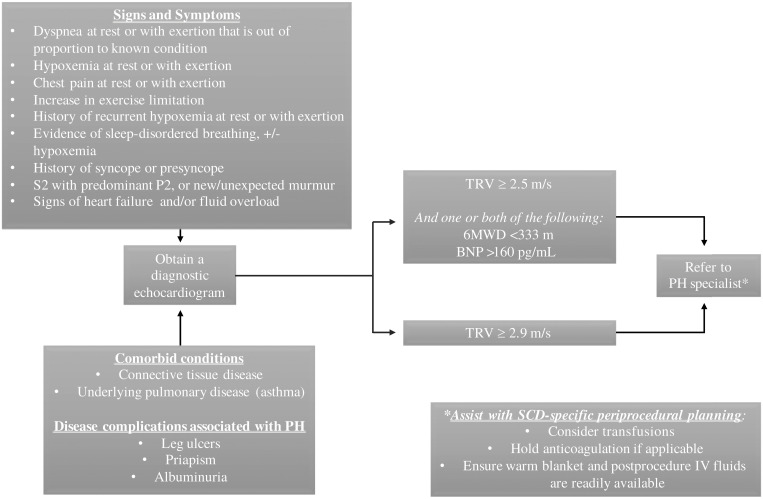

Progressive dyspnea on exertion or exercise limitations, especially with exertional hypoxia, should prompt further investigation for PH.24 On examination, patients may have signs of right heart failure, including elevated jugular venous pulsation, accentuated or fixed S2 splitting, tricuspid regurgitation (TR) murmur, and/or peripheral edema.

Although right heart catheterization (RHC) is the gold standard of diagnosis, its invasiveness has led to the development of more practical prognostic tools to predict the presence of PH. TR maximum velocity on echocardiogram can estimate pulmonary arterial systolic pressure. A TR velocity (TRV) more than 2.5 m/s was demonstrated to predict the presence of PH,24 and recent studies have shown that greater than 50% of patients with a TRV of 2.9 m/s are diagnosed with PH on RHC.25 Elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels are also associated with the presence of PH, and elevated N-terminal-pro-BNP levels are an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with SCD.24,26,27 A 2011 prospective study in France found that in patients with a TRV from 2.5 to 2.8 m/s, NT-pro-BNP more than 164, and a 6-minute walk distance less than 333 m, the positive predictive value of diagnosing PH on RHC was 62% (false-positive rate of 7%).28

Screening

Despite the association of PH with increased mortality, there is no consensus regarding screening guidelines, partially due to the lack of evidence demonstrating treatment benefit.29 The American Thoracic Society published guidelines in 2014 regarding risk stratification, screening, and management of PH in patients with SCD. Based on evidence that suggested 13% of patients with a normal echocardiogram develop an elevated TRV after 3 years of follow-up,30 the American Thoracic Society recommended a screening echocardiogram every 1 to 3 years in all patients with SCD.31 However, follow-up studies suggest that the rate of progression to PH may actually be slower.32 The most recent National Institutes of Health and American Society of Hematology guidelines recommend against routine screening in asymptomatic patients with SCD33,34 and recommend obtaining a diagnostic echocardiogram only for symptomatic patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

How I approach PH screening. Every patient with SCD should be screened for “red-flag” signs and symptoms of PH at routine visits (when there is no acute illness present). Any red-flag sign/symptom, or the presence of certain comorbidities or disease-specific complications, should be further evaluated with a diagnostic echocardiogram. A moderately elevated TRV, or a mild elevation with other prognostic factors, should warrant further referral to a specialist. IV, intravenous; 6MWD, 6-minute walk distance.

Definition, types (groups), prevalence, and pathophysiology

PH is defined as a resting mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) more than 25 mm Hg by RHC.24 In SCD, recurrent hemolysis and its disruption of the vascular endothelium ultimately leads to smooth muscle proliferation and adventitial fibroblast accumulation.35 This, in turn, leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance, right ventricular (RV) dysfunction, and decreased cardiac output.36 The prevalence of PH is thought to be 6% to 10% in SCD36 and can be further characterized by the location of hypertension relative to the capillary system.

Precapillary or pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is defined by a mPAP greater than 25 mm Hg and normal left ventricular end-diastolic pressure less than 15 mm Hg and falls under PH group I. Postcapillary or pulmonary venous hypertension is defined by an mPAP greater than 25 mm Hg with an elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure higher than 15 mm Hg,24 and it can be further grouped into PH World Health Organization groups II to V based on etiology. Pre- and postcapillary are distributed evenly in patients with SCD, and patients often have features of both.25,35

Management

PAH-specific therapies include the following.

Endothelin-receptor antagonists

Endothelin 1 is a potent vasoconstrictor that is elevated in SCD. The Randomized, Placebo- Controlled, Double-Blind, Multicenter, Parallel Group Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Bosentan in Patients With Symptomatic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Associated With Sickle Cell Disease (ASSET)-1 and -2 trials in 2009 were designed to investigate the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of bosentan, an endothelin 1 receptor antagonist, in patients with PAH and PH, respectively. Unfortunately, both trials were terminated early due to slow enrollment. However, the limited data obtained demonstrated tolerability and increased exercise tolerance,37 which were further supported by the findings of Minniti et al38 in 2009. In that cohort study, patients with RHC-confirmed PH receiving bosentan or ambrisentan had reduced BNP levels, reduced TRVs, and improved 6-minute walk test.

PDE-5 inhibitors

Although sildenafil has been shown to decrease TRV and BNP,39 a 2011 multicenter trial of sildenafil was stopped prematurely due to increased hospitalization for VOEs. Potential contributions to these events include lack of SCD therapy optimization prior to the intervention and sildenafil-specific mechanisms that may cause myalgias and inflammatory pain.15

Other PAH therapies

Prostanoids (epoprostenol, treprostinil, iloprost, beraprost) have not specifically been studied in SCD but have shown benefit in non-SCD patients with PH.40 In addition, 1 case study demonstrated decreased pulmonary arterial systolic pressure in 10 patients treated with 5 days of L-arginine.41

PH therapies

Intensification of SCD-specific therapies

The direct benefit of hydroxyurea on PH has not been studied, but it reduces episodes of VOEs and ACS, both of which are associated with an increase in PA pressures. Hydroxyurea should therefore indirectly decrease the risk of acute right-sided heart failure and death in patients with underlying PH.24 The effect of chronic transfusions on PH has also not been formally studied; however, because it reduces complications of SCD similar to hydroxyurea, it should theoretically improve outcomes in patients with underlying PH.

Treatment of comorbidities

Patients who have concurrent right heart failure or albuminuria can be treated with diuretics but cautiously, given the possibility of volume depletion and increased RBC sickling.24,31 In addition, patients with underlying sleep apnea and thrombotic disease should be managed accordingly.

Novel therapies

A phase 2 double-blind RCT is evaluating the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of riociguat (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02633397) in patients with SCD. Several of the secondary outcome measures specifically relate to markers of PH.

In addition, a phase 3 randomized parallel-arm trial is evaluating the effect of RBC exchange therapy compared with standard of care on cardiovascular risk (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04084080). Secondary outcomes specifically evaluate the effect on markers of PH.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Roberta C.G. Azbell: no conflicts to disclose.

Payal Chandarana Desai: consultant for GBT for grant review; advisory board for Forma; funding from the National Institutes of Health, University of Tennessee, and University of Pittsburgh; and speaker for Novartis.

Off-label drug use

Roberta C.G. Azbell: During the discussion of prevention of recurrent priapism, we discuss the off-label use of oral sympathomimetics, baclofen, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, hormonal therapies (GnRH agonists, estrogens, antiandrogens), ketoconazole, hydroxyurea, and exchange transfusion. With regard to management of SCLUs, we discuss the off-label use of exchange transfusions, hydroxyurea, topical sodium nitratre, and intradermal deferoxamine patches. We discuss the off-label use of hydroxyurea in pulmonary hypertension.

Payal Chandarana Desai: During the discussion of prevention of recurrent priapism, we discuss the off-label use of oral sympathomimetics, baclofen, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, hormonal therapies (GnRH agonists, estrogens, antiandrogens), ketoconazole, hydroxyurea, and exchange transfusion. With regard to management of SCLUs, we discuss the off-label use of exchange transfusions, hydroxyurea, topical sodium nitratre, and intradermal deferoxamine patches. We discuss the off-label use of hydroxyurea in pulmonary hypertension.

References

- 1.Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010; 376(9757):2018-2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ofori-Acquah SF. Sickle cell disease as a vascular disorder. Expert Rev Hematol. 2020;13(6):645-653. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2020.1758555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minniti CP, Kato GJ. How we treat sickle cell patients with leg ulcers clinical cases 40th anniversary issue. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(1):22-30. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martí-Carvajal AJ, Knight-Madden JM, Martinez-Zapata MJ. Interventions for treating leg ulcers in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(12):CD008394. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008394.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emond AM, Holman R, Hayes RJ, Serjeant GR. Priapism and impotence in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140(11):1434-1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bivalacqua TJ, Burnett AL. Priapism: new concepts in the pathophysiology and new treatment strategies. Curr Urol Rep. 2006;7(6):497-502. doi: 10.1007/s11934-006-0061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, et al; Members of the Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel; American Urological Association. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol. 2003;170(4, pt 1):1318-1324. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000087608.07371.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantadakis E, Ewalt DH, Cavender JD, Rogers ZR, Buchanan GR. Outpatient penile aspiration and epinephrine irrigation for young patients with sickle cell anemia and prolonged priapism. Blood. 2000;95(1):78-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broderick GA. Priapism and sickle–cell anemia: diagnosis and nonsurgical therapy. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):88-103. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballas SK, Lyon D. Safety and efficacy of blood exchange transfusion for priapism complicating sickle cell disease. J Clin Apher. 2016;31(1):5-10. doi: 10.1002/jca.21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel JF, Rich MA, Brock WA. Association of sickle cell disease, priapism, exchange transfusion and neurological events: ASPEN syndrome. J Urol. 1993;150(5, pt 1):1480-1482. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35817-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rackoff WR, Ohene-Frempong K, Month S, Scott JP, Neahring B, Cohen AR. Neurologic events after partial exchange transfusion for priapism in sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 1992;120(6):882-885. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81954-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chinegwundoh FI, Smith S, Anie KA. Treatments for priapism in boys and men with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9): CD004198. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004198.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson MJ, McNeillis V, Chiriaco G, Ralph DJ. Rare disorders of painful erection: a cohort study of the investigation and management of stuttering priapism and sleep-related painful erection. J Sex Med. 2021;18(2):376-384. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machado RF, Barst RJ, Yovetich NA, et al; walk-PHaSST Investigators and Patients. Hospitalization for pain in patients with sickle cell disease treated with sildenafil for elevated TRV and low exercise capacity. Blood. 2011;118(4):855-864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-306167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anele UA, Mack AK, Resar LMS, Burnett AL. Hydroxyurea therapy for priapism prevention and erectile function recovery in sickle cell disease: a case report and review of the literature. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46(9):1733-1736. doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0737-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan A, Jam'a A, Al Dabbous IA. Hydroxyurea in the treatment of sickle cell associated priapism. J Urol. 1998;159(5):1642. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199805000-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2004;17(8):410-416. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200410000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ladizinski B, Bazakas A, Mistry N, Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Salcido R. Sickle cell disease and leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25(9):420-428. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000419408.37323.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minniti CP, Taylor JG VI, Hildesheim M, et al.. Laboratory and echocardiography markers in sickle cell patients with leg ulcers. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(8):705-708. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serjeant GR, Howard C. Isoxsuprine hydrochloride in the therapy of sickle cell leg ulceration. West Indian Med J. 1977;26(3):164-166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMahon L, Tamary H, Askin M, et al.. A randomized phase II trial of arginine butyrate with standard local therapy in refractory sickle cell leg ulcers. Br J Haematol. 2010;151(5):516-524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minniti CP, Gorbach AM, Xu D, et al.. Topical sodium nitrite for chronic leg ulcers in patients with sickle cell anaemia: a phase 1 dose-finding safety and tolerability trial. Lancet Haematol. 2014;1(3):e95-e103. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3026(14)00019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ataga KI, Klings ES. Pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease: diagnosis and management. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014(1):425-431. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordeuk VR, Castro OL, Machado RF. Pathophysiology and treatment of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2016;127(7):820-828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-618561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machado RF, Anthi A, Steinberg MH, et al.. Risk of death in sickle cell disease. Vasc Med. 2006;296(3):310-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machado RF, Hildesheim M, Mendelsohn L, Remaley AT, Kato GJ, Gladwin MT. NT-pro brain natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of death in the cooperative study of sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(4):512-520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parent F, Bachir D, Inamo J, et al.. A hemodynamic study of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(1):44-53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, et al.. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA. 2014;312(10):1033-1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ataga KI, Moore CG, Jones S, et al.. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with sickle cell disease: a longitudinal study. Br J Haematol. 2006;134(1):109-115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klings ES, Machado RF, Barst RJ, et al; American Thoracic Society Ad Hoc Committee on Pulmonary Hypertension of Sickle Cell Disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: diagnosis, risk stratification, and management of pulmonary hypertension of sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(6):727-740. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0065ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desai PC, May RC, Jones SK, et al.. Longitudinal study of echocardiography-derived tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2013;162(6):836-841. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liem RI, Lanzkron S, D Coates T, et al.. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for sickle cell disease: cardiopulmonary and kidney disease. Blood Adv. 2019;3(23):3867-3897. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease: expert panel, 2014. Accessed 26 May 2019. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/sickle-cell-disease-report 020816_0.pdf

- 35.Wood KC, Gladwin MT, Straub AC. Sickle cell disease: at the crossroads of pulmonary hypertension and diastolic heart failure. Heart. 2020;106(8):562-568. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-314810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potoka KP, Gladwin MT. Vasculopathy and pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308(4):L314-L324. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00252.2014.-Sickle [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barst RJ, Mubarak KK, Machado RF, et al; ASSET study group. Exercise capacity and haemodynamics in patients with sickle cell disease with pulmonary hypertension treated with bosentan: results of the ASSET studies. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(3):426-435. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minniti CP, Machado RF, Coles WA, Sachdev V, Gladwin MT, Kato GJ. Endothelin receptor antagonists for pulmonary hypertension in adult patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(5):737-743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Machado RF, Martyr S, Kato GJ, et al.. Sildenafil therapy in patients with sickle cell disease and pulmonary hypertension. Br J Haematol. 2005;130(3):445-453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Machado RF, Gladwin MT. Chronic sickle cell lung disease: new insights into the diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(4):449-464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morris CR, Morris SM Jr, Hagar W, et al.. Arginine therapy: a new treatment for pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(1):63-69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-967OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]