Abstract

Objective:

Preclinical studies points to the KCNQ2/3 potassium channel as a novel target for the treatment of depression. This study is the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial testing the effect of the KCNQ2/3 positive modulator ezogabine on reward circuit activity and clinical outcomes in subjects with depression.

Methods:

Depressed individuals (N=45) were assigned to a 5-week treatment period with ezogabine (900 mg daily; N=21) or placebo (N=24). Subjects underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) during a reward flanker task at baseline and following treatment; clinical measures of depression and anhedonia were also collected at weekly visits. The primary end-point was the change from baseline to week 5 in the ventral striatum (VS) activation during reward anticipation. Secondary endpoints included depression and anhedonia severity as measured by the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS), respectively.

Results:

The study did not meet its primary neuroimaging endpoint. Subjects randomized to ezogabine showed a numerical increase in VS response to reward anticipation following treatment compared to participants randomized to placebo from baseline to week 5 (t=1.85, DF=38, p=.07). Relative to placebo, ezogabine was associated with a significantly larger improvement in MADRS (t=−4.04, p<.001), SHAPS (t=−4.1, p<.001), and other clinical endpoints. Ezogabine was well tolerated and no serious adverse events occurred.

Conclusions:

Our study did not meet its primary neuroimaging endpoint, although the effect of treatment was significant on several secondary clinical endpoints. In aggregate the findings may suggest that future studies of the KCNQ2/3 channel as a novel treatment target for depression are warranted.

Introduction

Depressive disorders are common, chronic and debilitating conditions characterized by affective, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms (1). Anhedonia, the reduced ability to experience pleasure or lack of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli, is a core symptom of depression and is associated with worse outcome, poor response to antidepressant medication, and increased risk for suicide (2; 3). Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved oral medications for major depressive disorder (MDD) largely consist of agents targeting the monoamine system. This lack of mechanistic diversity likely is an important contributor the limitations in the efficacy of the available treatments. Rational drug discovery based on a mechanistic understanding of disease pathology promises to deliver more effective, targeted therapies (4; 5).

Dysfunction within the brain reward system is emerging as a core feature of depressive disorders, in particular giving rise to deficits in response to pleasure leading to anhedonia (4; 5). The mesolimbic dopaminergic system plays an important role in the pathophysiology of depression (6–8). Preclinical studies utilizing chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) –a well validated chronic stress model of depression –show that molecular and physiological perturbations within dopaminergic neurons projecting from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) [a component of the ventral striatum (VS)] characterize a susceptible, pro-depressive, and anhedonic phenotype (8; 9). Within these brain regions, a critical role was played by the voltage-gated potassium (K+) channels, the KCNQ (or KV7), which includes KCNQ1–5. These channels are important regulators of cell membrane excitability and have been explored as potential targets of drug discovery for several central nervous system (CNS) conditions (10–12). Specifically, among them KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 form homodimers and/or heterodimers (e.g., KCNQ2/3 channels) and constitute the M-type channels (voltage-gated and ligand-regulated K+ channels) that regulate neural excitability (11). Critically, in the CSDS model described above, mice that do not develop a depressive phenotype (i.e., resilient mice) show an up-regulation of voltage-gated potassium (K+) channels including the KCNQ3 channels within the VTA compared to mice manifesting the susceptible depressive/anhedonic phenotype (8; 13; 14). Moreover, the susceptible phenotype can be reversed through overexpression of KCNQ3 channels, direct VTA injection of various KCNQ channel openers, or peripheral daily administration of the selective KCNQ2/3 channel opener ezogabine, also known as retigabine (13; 15).

Overall, these data provide a rationale for investigating the KCNQ2/3 channel as a target for drug discovery for disorders characterized by depression and anhedonia. As an initial proof of concept translational study, our group conducted a 10-week open-label pilot study of the effects of ezogabine up to 900 mg daily on clinical symptoms and brain connectivity in subjects with MDD (16). In that study, ezogabine showed good tolerability and participants exhibited a significant improvement in clinical and behavioral measures of depression and anhedonia.

Herein we report the results of a two-site, randomized controlled proof-of-concept exploratory trial testing the effects of ezogabine compared to placebo on brain response during reward anticipation and on clinical and behavioral measures of depression and anhedonia in adults meeting current criteria for a unipolar depressive disorder with elevated levels of anhedonia at baseline. This study was designed to test the KCNQ2/3 channel as a viable target for novel drug discovery for depression and anhedonia. Following an experimental therapeutics approach, the effect of treatment on brain response to reward was selected as a translational measure of target engagement. The primary outcome measure of the study was a change in activation during reward anticipation within the bilateral VS from baseline to the primary outcome visit as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) during the incentive flanker task (IFT) (17). Secondary outcomes included clinical measures of depression and anhedonia.

Methods

Study Participants and Design

This was a multi-center, parallel double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. The study procedures were conducted at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. The institutional review boards at both institutions approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any study procedure. Study participants were recruited from web-based and newspaper advertising, as well as clinician referrals, between September 2017 and August 2019. Participants were compensated for their time and effort. The study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03043560). Participants were between the ages of 18 and 65 and met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (18) criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) or persistent depressive disorder (PDD), as assessed by a trained rater using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Text Revision (DSM-V-TR) Axis I Disorders –Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) (19). If a participant met concurrent criteria for both MDD and PDD in a current major depressive episode (MDE), MDD was indicated as primary diagnosis. To be eligible, participants were not receiving any psychotropic medications at the time of randomization and for the duration of the study and had to exhibit clinically significant anhedonia with at least moderate illness severity, as defined by a Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) (20) score ≥ 20 and a Clinical Global Impression Severity (CGI-S) (21) score of ≥ 4 at screening, respectively. Exclusionary diagnoses included any primary psychiatric diagnosis other than a depressive disorder as defined by DSM-5 [comorbid anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were allowed], lifetime diagnosis of a major cognitive disorder, or substance use disorder in the past six months. Additional exclusion criteria are described in the Supplementary Material.

Following screening (Day −28 –Day −1), subjects who met all eligibility criteria returned to the clinics to complete the baseline assessments and undergo randomization (Day 0, Baseline). Baseline assessments included clinical evaluations, the Probabilistic Reward Task (PRT) (22; 23) and MRI scanning. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of the treatment arms (ezogabine, placebo) in a 1:1 fashion under double-blind conditions and entered the treatment period. Placebo tablets and ezogabine were encapsulated to preserve the study blind and were administered at a comparable frequency. During the treatment period, ezogabine was titrated according to the FDA guidelines until reaching a maximum target dose of 300 mg three times daily (900 mg/day) at week four. This dosage was selected based on evidence showing that ezogabine achieves adequate brain levels and has demonstrated efficacy for seizure disorder between 600 mg and 1,200 mg daily (24). The 900 mg daily dosage shows comparable efficacy and better tolerability compared to the 1200 mg dose for seizures according to the FDA package inset. Moreover, our pilot study utilized the 900 mg dose, which demonstrated preliminary efficacy and good tolerability. The treatment period consisted of five study visits (Study Visit 0–5), which culminated in the primary outcome visit (Study Visit 5), where participants completed clinician-administered and self-report questionnaires and underwent the second and final MRI scan and PRT assessment. At each visit, participants also completed self-report and clinician-administered rating scales performed by trained raters, and met with a study psychiatrist, blinded to the treatment assignment, who assessed suicidal thinking and behavior, adverse events (AE), and changes in concomitant medications. Medication compliance was assessed throughout the study using pill count, patient diary and subject report, and drug plasma levels on the primary outcome visit (Study Visit 5). Following this visit, participants were instructed to taper the study medication over three weeks according to the FDA recommended guidelines (during which they received weekly phone calls from a member of the study team to assess compliance and side effects) and returned to the clinic for a final study exit visit. The total duration of subject participation was up to 14 weeks. See Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material for study flow diagram.

The primary outcome measure of the study was a change in activation during reward anticipation (reward cue > neutral) within the bilateral VS from baseline (Study Visit 0) to the primary outcome visit (Study Visit 5) as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) during the incentive flanker task (IFT) (17). Secondary outcome measures included clinical symptoms of depression and anhedonia. Depression severity was measured using the clinician-rated Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (25) and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR) (26). Anhedonia severity was assessed using both the SHAPS, a validated 14-item self-report questionnaire that focuses on hedonic responses (20), and the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS) (27), a validated self-report that yields specific sub-scores of anticipatory pleasure and consummatory pleasure. In addition, the degree of change in interest or pleasure from a specific experience relative to the past was explored with the Specific Loss of Interest and Pleasure Scale (SLIPS) (28), while anhedonia related to social situations was explored with the Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale (ACIPS) (29). Global illness improvement and severity were evaluated at each visit by a study clinician using the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement and –Severity (CGI-I/S) scales (21). Suicidal ideation and behavior were measured using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (30). AEs were summarized according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) system organ class and preferred terms. Safety and tolerability were assessed by discontinuation rate, frequency of AEs, and change in score on the C-SSRS. Clinical raters completed standardized rater training at each site and achieved inter-rater reliability >90% for the MADRS. Additional secondary outcomes included change in behavioral measures of reward learning through a computer-based task, the PRT. Methods and results of ezogabine compared to placebo on the PRT are reported in Supplementary Material.

MRI Acquisition and Processing

All MRI data were acquired with a Siemens 3T MAGNETOM Skyra scanner using a 32-channel head coil at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Prisma with a 64-channel head coil at Baylor College of Medicine. Scans included an anatomical T1-weighted scan and a task-based functional scan with the IFT. The anatomical T1-weighted images were acquired with a magnetization-prepared 2 rapid gradient echo (MP2RAGE) sequence, which collects 2 volumes after each inversion for improved image quality (TR=4000 ms, TE=1.9, inversion 1/2 time=633/1860, FOV=186×162, voxel resolution= 1×1×1 mm), and the functional scan for task performance was collected with a multi-echo multiband accelerated echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence (TR=882 ms, TEs=11.0, 29.7, 48.4, 67.1, multi-band factor=5, FOV=560×560, voxel resolution= 3×3×3 mm, flip angle=45). Functional scans were preprocessed and denoised for motion and physiological noise using multi-echo independent component analysis (MEI-CA). Multi-echo functional MRI data was decomposed into independent components and scaled against TE. Components with high TE-dependence are considered blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD)-like whereas components with low TE-dependence are considered noise-like (31; 32). Removal of non-BOLD components allows robust data denoising for motion, physiological and scanner artifacts (31; 32).

Incentive flanker task during functional MRI

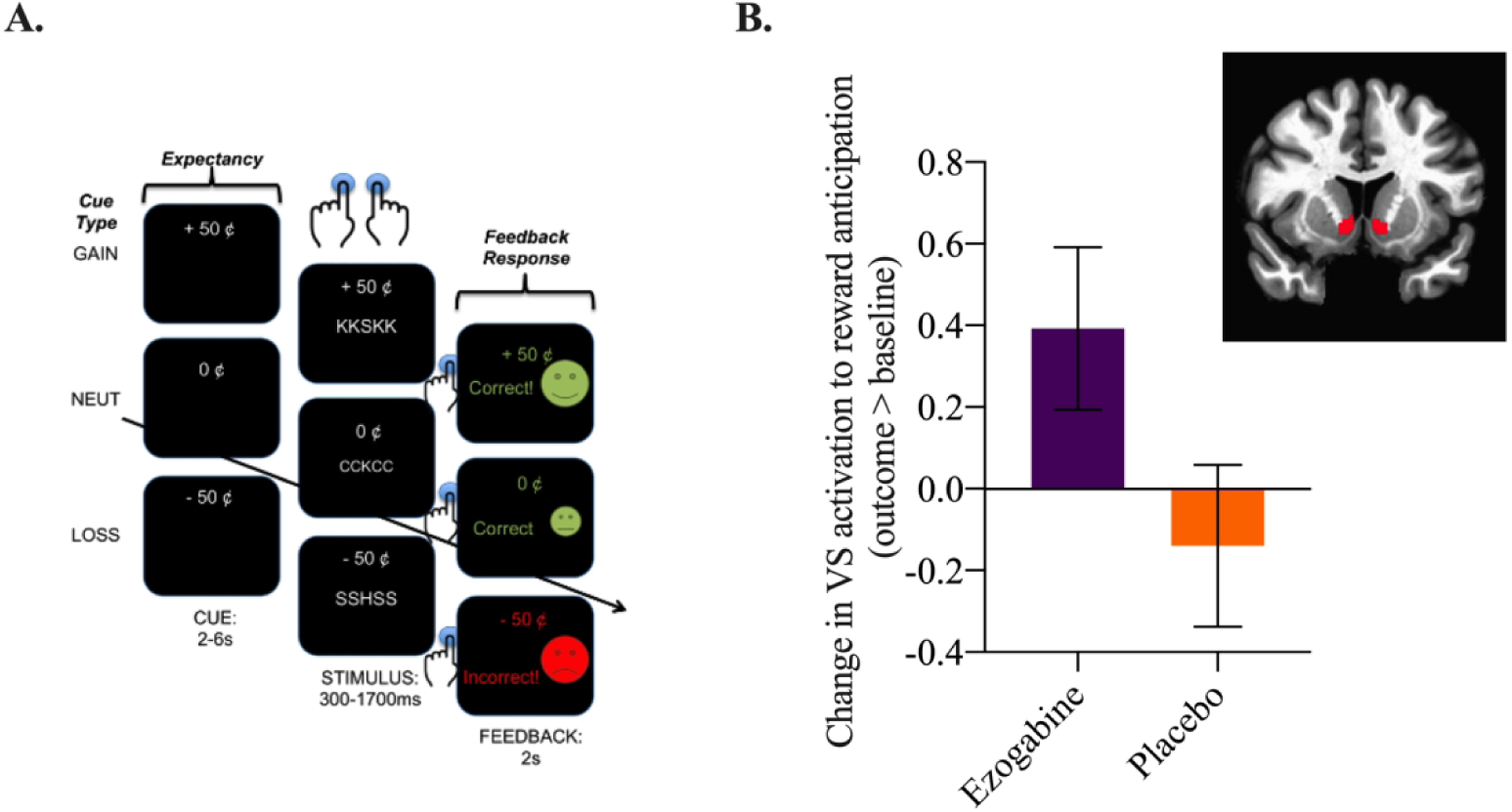

The IFT, like the Monetary Incentive Delay task [MID, (33)], permits discrete modeling of brain activity during anticipation of an incentive (17). Each trial begins with a monetary cue (reward/loss/neutral) followed by a string of five letters. Participants were instructed to press one of two buttons to identify the center letter. Success requires accurate identification of the target within a specific response period, titrated based on performance during a practice session. Feedback on performance including both text reading ‘Correct!’ or ‘Incorrect!’ and the total value of any money won or lost followed. There were 120 trials (40 each of reward, loss, and neutral) presented in pseudorandom order and equally divided across 4 runs of approximately 6 min each. Task-based modeling was conducted using AFNI (34) and FSL (35) software. Subject-level general linear models included regressors for onsets for cue type (reward/loss/neutral), flanker stimuli, and feedback. The duration of each cue varied between 2 and 6 seconds and was modeled with AFNI’s dmBLOCK function and convolved with the hemodynamic response function. As noted above, the primary outcome for the study utilized reward anticipation computed as the contrast of reward cue compared to neutral cue (reward cue > neutral). The loss cue was contrasted against the neutral cue in order to explore whether effects were specific to anticipation of potential reward. Parameter estimates for these contrasts were extracted within the VS ROI (from the Harvard-Oxford subcortical structures atlas provided by FSL, labeled ‘Nucleus Accumbens’) (35), for each subject and entered into statistical analyses. A description of the task is available in the Supplementary Material.

Statistical Analyses

Based on pilot data, a total sample size of N=48 was chosen to provide 85% power to detect a between-groups difference in means of 0.8 standard deviations assuming a correlation of 0.6 between a pair of measurements made on the same subject. The primary imaging outcome and all clinical measures assessed at multiple time points were analyzed using linear mixed effects models with a single random intercept term treating time as discrete or continuous as appropriate. AEs rates were compared between treatment groups using Poisson regression. Continuous baseline clinical and demographic characteristics were summarized using means or medians and compared by group using t-tests or Wilcoxon tests, as appropriate; discrete baseline characteristics were summarized by count and percentage and compared using a Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Correlation between measures was computed using Pearson r and Spearman rank for parametric and non-parametric distribution, respectively. A two-sided significance level of 0.05 was set for all comparisons. No correction was made for multiple comparisons. Effect sizes for differences in mean change from baseline to outcome between treatment arms were computed as Cohen’s d (36). Sensitivity analyses examined the effect of missing data by using a) the highest observed value and b) the lowest observed value for all missing primary outcome observations. All analyses were done on an intent-to-treat (ITT) basis and completed with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Seventy participants were assessed for eligibility; of those, 45 individuals were eligible for randomization and entered into the double-blind trial, and represent the ITT analyzed sample. Enrollment ended at n=45 participants randomized prior to reaching the targeted sample of n=48 due to exhaustion of the available supply of study drug. See Table 1 for a summary of the clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample. Dropout rates were low and did not differ significantly between groups; of the 45 randomized participants, 42 completed the primary outcome, yielding a retention rate of 93.3%.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Demographic Characteristics | Ezogabine (n=21) | Placebo (n=24) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age at enrollment, M (SD) | 44.4 | (13.6) | 38.9 | (14.3) | .19 |

| Gender, Male, n (%) | 11 | (52.4) | 12 | (50) | .87 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White/Caucasian | 12 | (57.1) | 12 | (50) | .63 |

| Black/African American | 5 | (23.8) | 7 | (29.2) | .68 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6 | (28.6) | 9 | (37.5) | .78 |

| Employment, n (%) | |||||

| at least Part-Time | 9 | (42.9) | 14 | (58.3) | .30 |

| Educational Attainment, n (%) | |||||

| At least some college | 15 | (71.4) | 21 | (87.5) | .18 |

| Relationship Status, n (%) | |||||

| Single, Never Married | 8 | (38.1) | 13 | (54.2) | .28 |

|

| |||||

| Depression Characteristics | |||||

|

| |||||

| Primary Diagnosis, n (%) | .34 | ||||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 21 | (100) | 23 | (95.8) | |

| Persistent Depressive Disorder | 0 | (0) | 1 | (4.2) | |

| Major Depressive Episode, n (%) | |||||

| Current | 21 | (100) | 22 | (91.7) | .36 |

| Age at Onset (years), M (SD) | 28.3 | (15.6) | 21.7 | (11.5) | .11 |

| Current Depressive Episode | |||||

| Duration in Months, Median (IQR) | 72 | (6–180) | 24 | (9.5–54) | .47 |

|

| |||||

| Psychiatric diagnoses | |||||

|

| |||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder, n (%) | 11 | (52.3) | 10 | (41.6) | .47 |

| PTSD, n (%) | 4 | (19) | 8 | (33.3) | .28 |

IQR, interquartile range; M, means; PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder; SD, Standard deviation. Race and ethnicity were reported by the study participants.

Across the whole sample, compliance with study medication as measured by pill count was 96% at the primary outcome visit (Study Visit 5) and was greater than 95% at each study visit. Blood samples were collected at the primary outcome visit (Study Visit 5) to determine plasma levels of ezogabine and N-acetyl-ezogabine. For further details, see the Supplementary Material that includes also Figure S2. Consort Chart Representing Patient Flow by Study Arm, ezogabine versus placebo.

Functional MRI data

Of the 45 subjects enrolled, all had a pre-treatment fMRI scan, and 40 (88%) had both a pre-treatment and post-treatment fMRI scan. Functional MRI data during the IFT were processed and analyzed for the 40 subjects with valid pre- and post-treatment data. Three subjects did not complete study primary outcome and two subjects were excluded due to failure to make any responses during the task. At baseline, groups did not differ in their performance accuracy (percentage errors for ezogabine: 10.4±10.3%; for placebo: 9.5±8.3%, p=0.77). Likewise, there was no difference in performance accuracy at the outcome visit (percentage errors for ezogabine: 8.1±8.2%; for placebo: 6.1±5.1%, p=0.51).

The effect of treatment on change in VS activation to reward from baseline to outcome was not significant; subjects randomized to ezogabine showed a numerical increase in VS activation following treatment compared to participants randomized to placebo (estimate=0.52, SEM=0.28; DF=38, t=1.85, p=.07; Figure 1). The effect size for the difference in change in means was Cohen’s d=0.58. An exploratory analysis conducted adding site as a random effect did not alter the results (estimate=0.53, SEM=0.28, DF=38, p=.07). There was no significant group difference in VS activation during loss anticipation from baseline to outcome (p=0.73). Exploratory whole-brain corrected analyses revealed no significant clusters for drug*time (controlling for site, age, and sex; whole-brain cluster-corrected FWE p<0.05, voxelwise p<0.001, K>25).

Figure 1. Effect of Treatment with Ezogabine Compared to Placebo on Activation of the Ventral Striatum to Reward Anticipation in Subjects with Depression and Anhedonia during the Incentive Flanker Task.

A. Schematic representation of the Incentive Flanker Task (IFT) used during the fMRI to measure brain responses to reward expectancy (or anticipation) and feedback response (or consumption). Anticipation of and response to loss can also be examined. B. Change in activation to reward anticipation (reward cue > neutral cue) during the IFT from baseline to the primary outcome visit (outcome > baseline) in the ezogabine (n=18) and placebo groups (n = 22) within the VS. Values reflect means with associated standard error of the mean (SEM). Ventral striatum (VS)/nucleus accumbens (NAc) region of interest (ROI).

Symptom Change

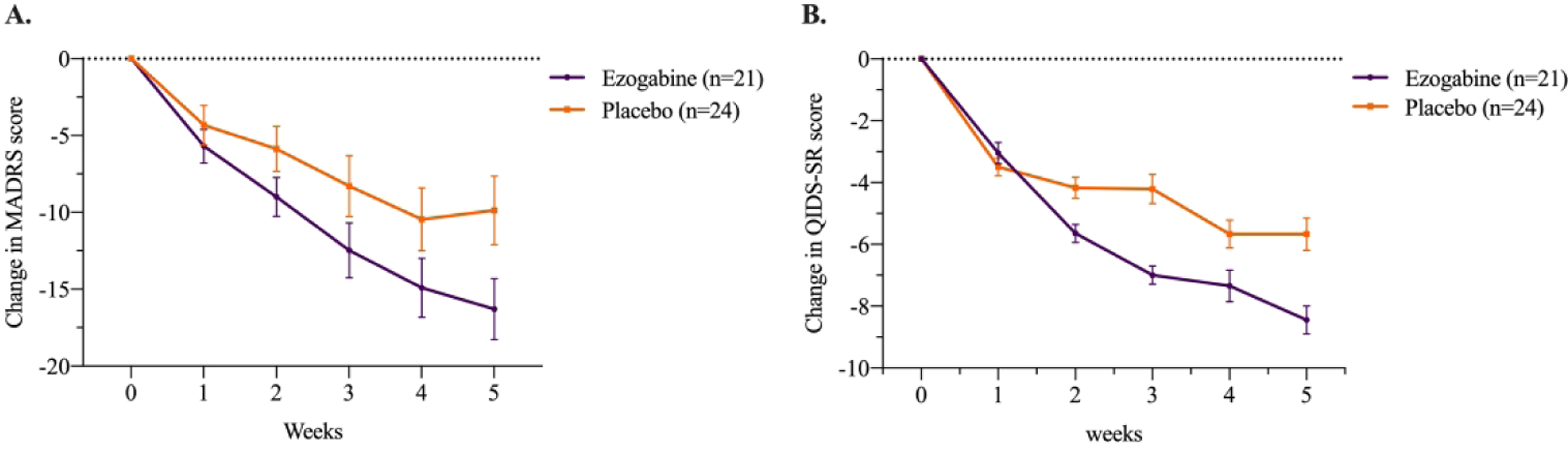

Ezogabine compared to placebo was associated with a large improvement in depression as measured by the MADRS (t=−4.04, DF=213, p<.001, Figure 2; Table 2). The mean change in MADRS from baseline to endpoint was 15.9±8.9 and 8±10.4 for ezogabine and placebo, respectively. The mean difference in MADRS score between baseline and primary outcome visit was −7.9±3.0 and the effect size for the difference in change in means for MADRS was Cohen’s d=0.76. The response rate (greater than or equal to 50% reduction in MADRS score for baseline to the primary outcome visit) was 61.9% (13/21) and 37.5% (9/24) for ezogabine and placebo, respectively. The remission rate (MADRS score below 10 at the primary outcome visit) was 38.1% (8/21) and 20.8% (5/24) for ezogabine and placebo, respectively. The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) based on remission rate was equal to 6, while the NNT based on response rate was equal to 4.

Figure 2. Effect of Treatment with Ezogabine Compared to Placebo on Depression Severity in Subjects with Depressive Disorder and Anhedonia.

Change in MADRS and QIDS-SR scores during clinical trial of ezogabine/placebo in subjects with depression (n = 45). Values reflect means with associated standard error of the mean (SEM). MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology - Self-Report.

Table 2.

Change in Clinical Outcomes Following Treatment with Ezogabine or Placebo in Subjects with Depressive Disorder and Anhedonia

| Ezogabine Mean (SD) | Placebo Mean (SD) | Estimate | SEM | DF | t | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Primary outcome | Difference | Baseline | Primary outcome | Difference | ||||||

| MADRS | 28.3 (6.1) | 12.7 (8.7) | 15.9 (8.9) | 26.8 (5.1) | 18.5 (10.1) | 8 (10.4) | −1.49 | 0.37 | 213 | −4.04 | <.001 |

| QIDS-SR | 16 (3.2) | 7.5 (5.2) | 8.5 (5.1) | 15.2 (4.1) | 9.5 (6.4) | 5.5 (5.3) | −0.65 | 0.21 | 213 | −3.1 | .002 |

| SHAPS | 38.7 (8.1) | 27.5 (8.5) | 10.3 (10.9) | 33.7 (6) | 30 (10.9) | 3.4 (10.0) | −1.55 | 0.38 | 212 | −4.1 | <.001 |

| TEPS-A | 26.3 (8.3) | 37.3 (10.5) | 10.5 (10.5) | 28.6 (8.7) | 32.4 (11.5) | 3.8 (8.7) | 1.33 | 0.39 | 213 | 3.4 | <.001 |

| TEPS-C | 24.8 (8.1) | 32.2 (6) | 6.6 (9.4) | 25.6 (7.6) | 29.9 (10.5) | 3.9 (6.5) | 0.64 | 0.32 | 213 | 2.0 | .049 |

| SLIPS | 32.3 (9.8) | 16.3 (16.7) | 15.8 (13.7) | 28.8 (10.4) | 21.5 (16.8) | 7.5 (14.5) | −1.79 | 0.53 | 213 | −3.4 | <.001 |

| ACIPS | 46.1 (15.1) | 65.1 (22.8) | 17.8 (18.6) | 53.7 (15) | 59 (23.5) | 5.6 (18.1) | 2.77 | 0.72 | 213 | 3.8 | <.001 |

| CGI-S | 4.4 (0.5) | 2.6 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.2) | 4.6 (0.6) | 3.3 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.2) | −0.1 | 0.05 | 214 | −2.2 | .026 |

| CGI-I | 4 (0.2) | 2.1 (1) | 2.0 (1.0) | 4 (0.4) | 2.8 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.3) | −0.15 | 0.05 | 214 | −2.9 | .004 |

Table 2 reports clinical outcomes during the study. Left: Descriptive statistics are provided for observed values for each measure. Right: Summary statistics reported are computed based on the mixed model and the values correspond to the interaction term, as described in the manuscript. Abbreviations: ACIPS, Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression Scale; DF, degree of freedom; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology –Self Report; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean; SHAPS, Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale; TEPS, Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS-A anticipatory subscale; TEPS-C consummatory subscale); SLIPS, Specific Loss of Interest and Pleasure Scale. For descriptive purposes we report the means at baseline (week 0, pre-treatment) and primary outcome (week 5, post-treatment) for the secondary outcome measures.

Similarly, compared to placebo, ezogabine was associated with a significant improvement in depression as measured by the QIDS-SR (t=−3.1, DF=213, p=.002). The mean difference in QIDS-SR scores between baseline and primary outcome visit was −3.0±0.7, corresponding to a medium-large effect size (Cohen’s d=0.56; Figure 2).

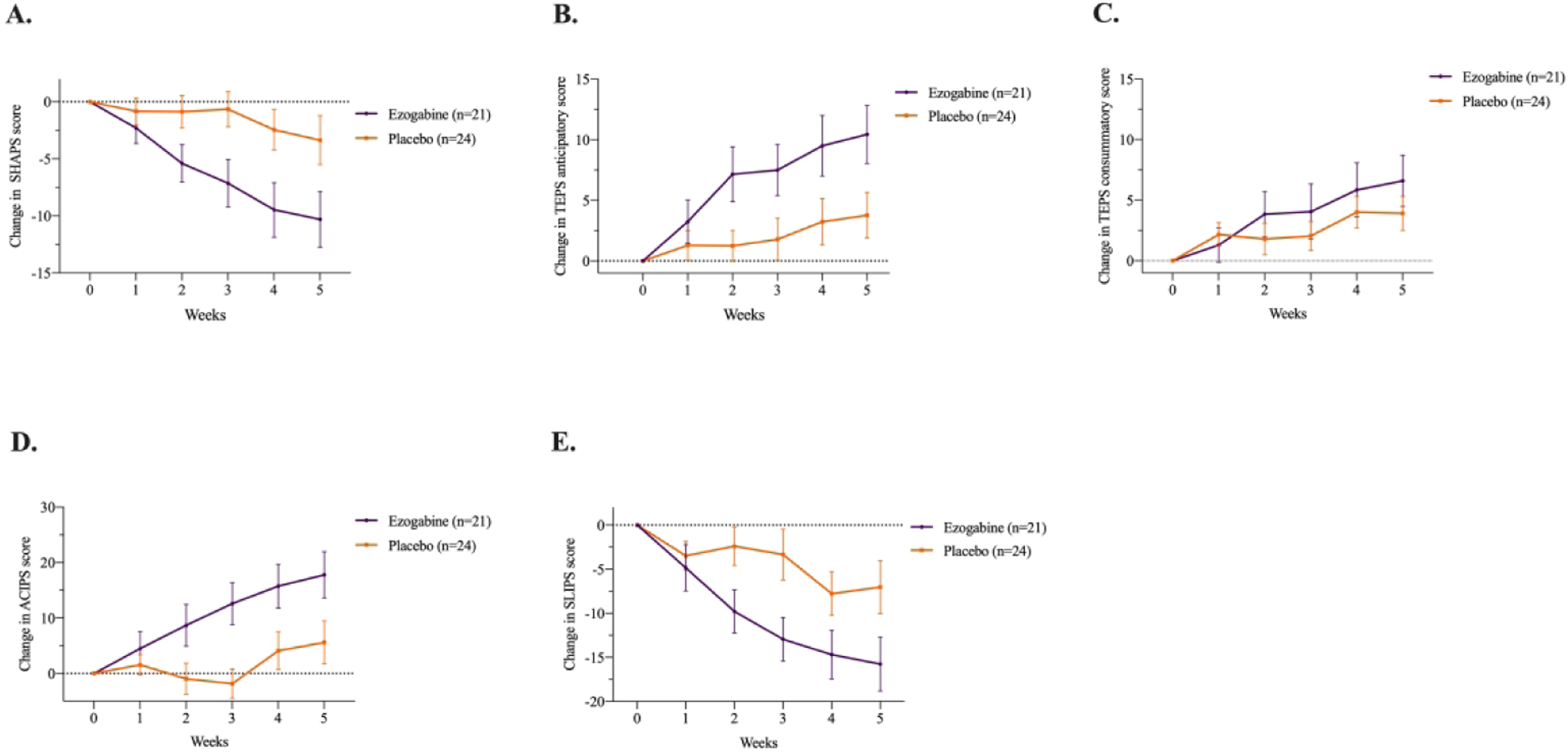

Compared to placebo, ezogabine was associated with a large improvement in hedonic capacity as measured by the SHAPS (t=−4.1, DF=212, p<.001; Table 2 and Figure 3) and the anticipatory subscale of the TEPS (t=3.4, DF=213, p<.001; Table 2 and Figure 3). A smaller benefit for ezogabine over placebo was observed for the consummatory subscale of the TEPS (t=2.0, DF=213, p=.05, Table 2 and Figure 3). Mean difference in SHAPS, anticipatory subscale of the TEPS, and consummatory subscale of the TEPS scores between baseline and primary outcome visit were −6.9±3.2, 6.7±3.1, and 2.7±2.5, respectively. The associated Cohen’s d showed a large effect size for the difference in change in means for SHAPS and the anticipatory subscale of the TEPS (Cohen’s d=0.64 and 0.66, respectively) and a small-medium effect on the consummatory subscale of the TEPS (Cohen’s d=0.34). Consistently, significant benefit for ezogabine over placebo was also observed for anhedonia as measured by the ACIPS (t=3.8, DF=213, p<.001) and SLIPS (t=−3.4, DF=213, p<.001). Within subjects randomized to ezogabine, change in VS activation to reward anticipation from baseline to outcome was correlated with change in anticipatory anhedonia as measured by the TEPS (ρ= 0.49, p=0.04), such that increased VS activation was associated with higher response to pleasure. This association was not observed across the whole sample (ρ=0.12, p=0.45).

Figure 3. Effect of Treatment with Ezogabine Compared to Placebo on Symptoms of Anhedonia in Subjects with Depressive Disorder and Anhedonia.

Change in SHAPS, anticipatory and consummatory sub-scores of the TEPS, ACIPS, and SLIPS scores during clinical trial of ezogabine/placebo in subjects with depression (n = 45). Values reflect means with associated standard error of the mean (SEM). SHAPS, Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale; TEPS, Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale; ACIPS, Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale; SLIPS, Specific Loss of Interest and Pleasure Scale.

Finally, ezogabine compared to placebo was associated with a significant benefit in terms of both global illness severity (CGI-S, t=−2.2, DF=214, p=.026) and global illness improvement (CGI-I, t=−2.9, DF=214, p=.004). See Table 2 for details regarding clinical outcomes.

Safety and tolerability

No serious AEs occurred in the course of the trial. The most common AEs were dizziness and headache; only two AEs reached statistical significance (dizziness and confusion) and both were higher in the ezogabine group. In the ezogabine group, the most common AE was dizziness, which had an incidence rate of 39.7/100 patient-months. Within the placebo group the most common AEs were headache (12/100 patient-months), dizziness (8.6/100 patient-months) and nausea (8.6/100 patient-months). Due to the occurrence of AEs, four study participants in the ezogabine group failed to achieve the highest dose (900 mg/day) and remained at 750 mg/day (n=2), 600 mg/day (n=1), and 450 mg/day (n=1); however no subject in the ezogabine group discontinued the study due to AEs. One case of retinal abnormality (operculated retinal hole) not described at screening was reported in one participant randomized to ezogabine at the ophthalmologist visit during study exit. No elongation of the QT interval (operationalized as a QT interval over 500 milliseconds or a 60-milliseconds increase in the QT interval from baseline) was observed during the study. In the overall sample there was no emergence of serious suicidal ideation compared to baseline, as defined by an increase in the maximum suicidal ideation score to three or greater on the C-SSRS during the trial. No participants experienced emergence of suicidal behavior during the study. A summary of study AEs is reported in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

Discussion

We report the results of the first randomized controlled trial investigating the effect of a KCNQ2/3 channel opener on brain and clinical measures linked to depression and anhedonia in humans. The primary neuroimaging endpoint of the study, the effect of treatment with ezogabine compared to placebo on VS response to reward, was not met. Treatment with ezogabine compared to placebo was associated with significant improvements in clinician and self-report measures of both depression and anhedonia, as well as on measures of global illness severity. Improvement in response to reward within the VS was positively associated with improvement in anticipatory pleasure among subjects treated with ezogabine. Ezogabine was generally well tolerated and no serious AEs occurred during the trial.

Following an experimental medicine approach, the effect of treatment with a KCNQ2/3 channel opener on brain response to reward was selected as a translational measure of target engagement. Preclinical studies highlight KCNQ channels as a potential novel drug target for the treatment of depressive disorders and anhedonia (13; 14). Within the context of the CSDS model described above, upregulation of KCNQ3 channels is observed within VTA dopamine neurons of mice resilient to stress, and genetic and pharmacologic enhancement of KCNQ3 channel function in these neurons both normalizes pathological hyperactivity of these dopamine neurons and reverses depressive behaviors in susceptible mice. Hyperactivity within the VTA-NAc circuit in susceptible mice appears to be driven by intrinsic changes in channel function that lead to a hyperpolarization-activated cation channel-mediated current. In contrast, resilient mice are characterized by a stable firing that is homeostatically maintained by K+ channels. As demonstrated by Friedman et al. (13), KCNQ channels contribute to K+ channels activity in resilient mice. The direct potentiation of KCNQ channels in susceptible mice was able to normalize the pathogenic hyperactivity of VTA dopaminergic neurons and produce antidepressant effects at the behavioral level. A recent study by Feng et al. (37) replicated these findings using a chronic high fat diet induced model of neuroinflammation that results in depressive-like behavior.

In line with the research domain criteria (RDoC) initiative put forward by the National Institute of Mental Health, we selected a specific neurobehavioral domain of functioning relevant to depression as the dependent outcomes for our study, namely the positive valence system that encompasses reward anticipation. Depressed individuals show deficits in the capacity to anticipate pleasurable stimuli (38), as assessed through self-report scales and laboratory-based measures (39). Individuals with depression show abnormal responses to reward expectancy within a well-defined cortico-striatal reward circuit encompassing the VS (and the NAc), VTA and prefrontal cortex (40–42). These altered responses appear to normalize with antidepressant treatment in several small studies (43; 44), consistent with the preclinical work described above. A recent randomized controlled trial of the selective kappa opioid receptor (KOR) antagonist JNJ-67953964 demonstrated a significant increase in VS activation during reward anticipation using the MID and fMRI compared with placebo in patients with anhedonia across a spectrum of mood and anxiety disorders (45). The current study utilized a similar methodology, including the use of fMRI with the IFT (a reward task similar to the MID) to measure the hypothesized effect of treatment on the reward circuit operationalized with a ROI-based approach focusing on the VS. In contrast to Krystal et al, our study failed to show a significant effect of treatment on the VS. In addition, while our study did show beneficial effects of treatment on several secondary clinical outcomes, the clinical benefit of the intervention in Krystal et al was less clear. There are important differences between the two studies, which may have contributed to the somewhat divergent findings. Regarding the discrepancy of the effect of treatment on VS response to reward, it should be noted that our sample size was approximately onehalf of that of Krystal et al, raising the possibility that the lack of a significant finding in our study represents a type II error. In fact, the standardized mean effect of treatment on VS response was 0.58 in both studies.

This study has several limitations. The primary limitation of this study is the small sample size. As noted above, our negative finding on the primary outcome may reflect a type II error since the effect went in the hypothesized direction, only very narrowly missed the alpha threshold of 0.05, and the significant effects of treatment on the clinical outcomes suggest that the intervention may have activity at depression-relevant brain targets. Our study suggests that investigators should power studies to detect effects of treatment on brain targets in a range that includes 0.58 standard deviation units since this was the effect size observed in both the current study and in Krystal et al. Studies utilizing limited sample sizes may consider alternative statistical approaches such as utilizing a more lenient alpha level, utilizing a futility design, or utilization a Bayesian approach. Other limitations in our study include the enrollment of medication-free subjects suffering from a broader unipolar depressive phenotype with clinically significant anhedonia that can limit the generalizability of the findings. Further, the short treatment duration in the current study (4-week titration plus 1-week at target dose) precludes conclusions regarding longer-term efficacy or tolerability. Finally, since the study lacked a healthy non-depressed control group at baseline, it is unknown if patients in the trial had abnormally low VS activity in response to reward prior to treatment.

In conclusion, this is the first randomized, placebo-controlled study investigating the antidepressant effect of the KCNQ2/3-selective channel opener ezogabine in subjects with unipolar depression. Based on these findings, larger randomized controlled trials of KCNQ2/3 channel openers in depressive disorders are warranted to explore their potential as a viable treatment for depressive disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R61MH111932. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional funding for this study was provided by the Ehrenkranz Laboratory for Human Resilience, a component of the Depression and Anxiety Center for Discovery and Treatment at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

We would like to thank the research pharmacists at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center, including Ivy Cohen, Biju Johnson, Alla Khodzhayeva, and Giuseppe Difiore for their extensive work on this project.

Authors’ Disclosures. In the past 5 years, Dr. Murrough has provided consultation services and/or served on advisory boards for Allergan, Boehreinger Ingelheim, Clexio Biosciences, Fortress Biotech, FSV7, Global Medical Education (GME), Impel Neuropharma, Janssen Research and Development, Medavante-Prophase, Novartis, Otsuka, and Sage Therapeutics. In the past 12 months, Dr. Murrough has provided consultation services and/or served on advisory boards for Boehreinger Ingelheim, Clexio Biosciences, Global Medical Education (GME), and Otsuka. Dr. Murrough is named on a patent pending for neuropeptide Y as a treatment for mood and anxiety disorders and on a patent pending for the use of ezogabine and other KCNQ channel openers to treat depression and related conditions. The Icahn School of Medicine (employer of Dr. Murrough) is named on a patent and has entered into a licensing agreement and will receive payments related to the use of ketamine or esketamine for the treatment of depression. The Icahn School of Medicine is also named on a patent related to the use of ketamine for the treatment of PTSD. Dr. Murrough is not named on these patents and will not receive any payments. Dr. Collins is a paid independent rater for Medavante-Prophase. Dr. Jha has received contract research grants from Acadia Pharmaceuticals and Janssen Research & Development, and honoraria for CME presentations from North American Center for Continuing Medical Education and Global Medical Education. In the past five years, Dr. Iosifescu has received consulting fees from Alkermes, Axsome, Centers for Psychiatric Excellence (COPE), Global Medical Education, MyndAnalytics (CNS Response), Jazz, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Precision Neuroscience, Sage, Sunovion, and has received research support (through his academic institutions) from Alkermes, Astra Zeneca, Brainsway, LiteCure, Neosync, Roche, Shire. Dr. Mathew is supported through the use of facilities and resources at the Michael E. Debakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Texas. Dr. Mathew has served as a consultant to Alkermes, Allergan, Axsome Therapeutics, Clexio Biosciences, EMA Wellness, Greenwich Biosciences, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Perception Neuroscience, Praxis Precision Medicines, Sage Therapeutics, Seelos Therapeutics, and Signant Health. He has received research support from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals and VistaGen Therapeutics. Dr. Swann is supported through the use of facilities and resources at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston. He has grant support from the Department of Defense, Veterans Administration, and American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. He has served as a consultant for Otsuka and Lundbeck and received royalties from Oxford University Press. Dr. Ming-Hu Han is named on a patent pending for the use of ezogabine (KCNQ channel opener) to treat depression and related conditions. Over the past three years, Dr. Pizzagalli has received consulting fees from Akili Interactive Labs, BlackThorn Therapeutics, Boehreinger Ingelheim, Compass Pathway, Posit Science, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals; one honorarium from Alkermes; stock options from BlackThorn Therapeutics; and funding from NIMH, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Dana Foundation, and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pizzagalli has a financial interest in BlackThorn Therapeutics, which has licensed the copyright to the Probabilistic Reward Task through Harvard University. Dr. Pizzagalli’s interests were reviewed and are managed by McLean Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. All the other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests

Footnotes

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03043560.

Bibliography

- 1.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJL, Vos T, Whiteford HA: Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013; 10:e1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wardenaar KJ, Giltay EJ, van Veen T, Zitman FG, Penninx BWJH: Symptom dimensions as predictors of the two-year course of depressive and anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disord 2012; 136:1198–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moos RH, Cronkite RC: Symptom-based predictors of a 10-year chronic course of treated depression. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 1999; 187:360–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anacker C: Fresh approaches to antidepressant drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov 2014; 9:407–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millan MJ, Goodwin GM, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Ove Ögren S: Learning from the past and looking to the future: Emerging perspectives for improving the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 2015; 25:599–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB: The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007; 64:327–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gershon AA, Vishne T, Grunhaus L: Dopamine D2-like receptors and the antidepressant response. Biol. Psychiatry 2007; 61:145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan V, Han M-H, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Laplant Q, Graham A, Lutter M, Lagace DC, Ghose S, Reister R, Tannous P, Green TA, Neve RL, Chakravarty S, Kumar A, Eisch AJ, Self DW, Lee FS, Tamminga CA, Cooper DC, Gershenfeld HK, Nestler EJ: Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell 2007; 131:391–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Juarez B, Ku SM, Koo JW, Ferguson D, Tsai H-C, Pomeranz L, Christoffel DJ, Nectow AR, Ekstrand M, Domingos A, Mazei-Robison MS, Mouzon E, Lobo MK, Neve RL, Friedman JM, Russo SJ, Deisseroth K, Nestler EJ, Han M-H: Rapid regulation of depression-related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature 2013; 493:532–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong Q, Gao Z, Wang W, Li M: Activation of Kv7 (KCNQ) voltage-gated potassium channels by synthetic compounds. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2008; 29:99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang HS, Pan Z, Shi W, Brown BS, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, Dixon JE, McKinnon D: KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel subunits: molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science 1998; 282:1890–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wulff H, Castle NA, Pardo LA: Voltage-gated potassium channels as therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2009; 8:982–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman AK, Juarez B, Ku SM, Zhang H, Calizo RC, Walsh JJ, Chaudhury D, Zhang S, Hawkins A, Dietz DM, Murrough JW, Ribadeneira M, Wong EH, Neve RL, Han M-H: KCNQ channel openers reverse depressive symptoms via an active resilience mechanism. Nat. Commun 2016; 7:11671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman AK, Walsh JJ, Juarez B, Ku SM, Chaudhury D, Wang J, Li X, Dietz DM, Pan N, Vialou VF, Neve RL, Yue Z, Han M-H: Enhancing depression mechanisms in midbrain dopamine neurons achieves homeostatic resilience. Science 2014; 344:313–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Sun H, Ding J, Niu C, Su M, Zhang L, Li Y, Wang C, Gamper N, Du X, Zhang H: Selective targeting of M-type potassium Kv 7.4 channels demonstrates their key role in the regulation of dopaminergic neuronal excitability and depression-like behaviour. Br. J. Pharmacol 2017; 174:4277–4294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan A, Costi S, Morris LS, Van Dam NT, Kautz M, Whitton AE, Friedman AK, Collins KA, Ahle G, Chadha N, Do B, Pizzagalli DA, Iosifescu DV, Nestler EJ, Han M-H, Murrough JW: Effects of the KCNQ channel opener ezogabine on functional connectivity of the ventral striatum and clinical symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stern ER, Welsh RC, Fitzgerald KD, Gehring WJ, Lister JJ, Himle JA, Abelson JL, Taylor SF: Hyperactive error responses and altered connectivity in ventromedial and frontoinsular cortices in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2011; 69:583–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, Research Version; SCID-5-RV). Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association; 2015; [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snaith RP, Hamilton M, Morley S, Humayan A, Hargreaves D, Trigwell P: A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1995; 167:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busner J, Targum SD: The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007; 4:28–37 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pizzagalli DA, Jahn AL, O’Shea JP: Toward an objective characterization of an anhedonic phenotype: a signal-detection approach. Biol. Psychiatry 2005; 57:319–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pizzagalli DA, Iosifescu D, Hallett LA, Ratner KG, Fava M: Reduced hedonic capacity in major depressive disorder: evidence from a probabilistic reward task. J. Psychiatr. Res 2008; 43:76–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Large CH, Sokal DM, Nehlig A, Gunthorpe MJ, Sankar R, Crean CS, Vanlandingham KE, White HS: The spectrum of anticonvulsant efficacy of retigabine (ezogabine) in animal models: implications for clinical use. Epilepsia 2012; 53:425–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery SA, Asberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Ninan PT, Kornstein S, Manber R, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Keller MB: The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2003; 54:573–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gard DE, Kring AM, Gard MG, Horan WP, Green MF: Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophr. Res 2007; 93:253–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winer ES, Veilleux JC, Ginger EJ: Development and validation of the Specific Loss of Interest and Pleasure Scale (SLIPS). J. Affect. Disord 2014; 152–154:193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gooding DC, Pflum MJ: The assessment of interpersonal pleasure: introduction of the Anticipatory and Consummatory Interpersonal Pleasure Scale (ACIPS) and preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 2014; 215:237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ: The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011; 168:1266–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kundu P, Inati SJ, Evans JW, Luh W-M, Bandettini PA: Differentiating BOLD and non-BOLD signals in fMRI time series using multi-echo EPI. Neuroimage 2012; 60:1759–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kundu P, Brenowitz ND, Voon V, Worbe Y, Vértes PE, Inati SJ, Saad ZS, Bandettini PA, Bullmore ET: Integrated strategy for improving functional connectivity mapping using multiecho fMRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013; 110:16187–16192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Varner JL, Hommer D: Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport 2001; 12:3683–3687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox RW: AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput. Biomed. Res 1996; 29:162–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Smith SM: FSL. Neuroimage 2012; 62:782–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J: Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New Jersey, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng M, Crowley NA, Patel A, Guo Y, Bugni SE, Luscher B: Reversal of a Treatment-Resistant, Depression-Related Brain State with the Kv7 Channel Opener Retigabine. Neuroscience 2019; 406:109–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McFarland BR, Klein DN: Emotional reactivity in depression: diminished responsiveness to anticipated reward but not to anticipated punishment or to nonreward or avoidance. Depress. Anxiety 2009; 26:117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olino TM, McMakin DL, Dahl RE, Ryan ND, Silk JS, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Forbes EE: “I won, but I’m not getting my hopes up”: depression moderates the relationship of outcomes and reward anticipation. Psychiatry Res. 2011; 194:393–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein J, Pan H, Kocsis JH, Yang Y, Butler T, Chusid J, Hochberg H, Murrough J, Strohmayer E, Stern E, Silbersweig DA: Lack of ventral striatal response to positive stimuli in depressed versus normal subjects. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006; 163:1784–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang W-N, Chang S-H, Guo L-Y, Zhang K-L, Wang J: The neural correlates of reward-related processing in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. J. Affect. Disord 2013; 151:531–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pizzagalli DA, Holmes AJ, Dillon DG, Goetz EL, Birk JL, Bogdan R, Dougherty DD, Iosifescu DV, Rauch SL, Fava M: Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2009; 166:702–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoy M, Schlagenhauf F, Sterzer P, Bermpohl F, Hägele C, Suchotzki K, Schmack K, Wrase J, Ricken R, Knutson B, Adli M, Bauer M, Heinz A, Ströhle A: Hyporeactivity of ventral striatum towards incentive stimuli in unmedicated depressed patients normalizes after treatment with escitalopram. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 2012; 26:677–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ossewaarde L, Verkes RJ, Hermans EJ, Kooijman SC, Urner M, Tendolkar I, van Wingen GA, Fernández G: Two-week administration of the combined serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor duloxetine augments functioning of mesolimbic incentive processing circuits. Biol. Psychiatry 2011; 70:568–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krystal AD, Pizzagalli DA, Smoski M, Mathew SJ, Nurnberger J, Lisanby SH, Iosifescu D, Murrough JW, Yang H, Weiner RD, Calabrese JR, Sanacora G, Hermes G, Keefe RSE, Song A, Goodman W, Szabo ST, Whitton AE, Gao K, Potter WZ: A randomized proof-of-mechanism trial applying the “fast-fail” approach to evaluating κ-opioid antagonism as a treatment for anhedonia. Nat. Med 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.