ABSTRACT

Human parainfluenza virus 3 (HPIV3) belongs to the Paramyxoviridae, causing annual worldwide epidemics of respiratory diseases, especially in newborns and infants. The core components consist of just three viral proteins: nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), and RNA polymerase (L), playing essential roles in replication and transcription of HPIV3 as well as other paramyxoviruses. Viral genome encapsidated by N is as a template and recognized by RNA-dependent RNA polymerase complex composed of L and P. The offspring RNA also needs to assemble with N to form nucleocapsids. The N is one of the most abundant viral proteins in infected cells and chaperoned in the RNA-free form (N0) by P before encapsidation. In this study, we presented the structure of unassembled HPIV3 N0 in complex with the N-terminal portion of the P, revealing the molecular details of the N0 and the conserved N0-P interaction. Combined with biological experiments, we showed that the P binds to the C-terminal domain of N0 mainly by hydrophobic interaction and maintains the unassembled conformation of N by interfering with the formation of N-RNA oligomers, which might be a target for drug development. Based on the complex structure, we developed a method to obtain the monomeric N0. Furthermore, we designed a P-derived fusion peptide with 10-fold higher affinity, which hijacked the N and interfered with the binding of the N to RNA significantly. Finally, we proposed a model of conformational transition of N from the unassembled state to the assembled state, which helped to further understand viral replication.

IMPORTANCE Human parainfluenza virus 3 (HPIV3) causes annual epidemics of respiratory diseases, especially in newborns and infants. For the replication of HPIV3 and other paramyxoviruses, only three viral proteins are required: phosphoprotein (P), RNA polymerase (L), and nucleoprotein (N). Here, we report the crystal structure of the complex of N and its chaperone P. We describe in detail how P acts as a chaperone to maintain the unassembled conformation of N. Our analysis indicated that the interaction between P and N is conserved and mediated by hydrophobicity, which can be used as a target for drug development. We obtained a high-affinity P-derived peptide inhibitor, specifically targeted N, and greatly interfered with the binding of the N to RNA, thereby inhibiting viral encapsidation and replication. In summary, our results provide new insights into the paramyxovirus genome replication and nucleocapsid assembly and lay the basis for drug development.

KEYWORDS: HPIV3, nucleoprotein, phosphoprotein, crystal structure, allosteric effect

INTRODUCTION

Human parainfluenza virus 3 (HPIV3, also known as human respirovirus 3) belongs to the genus Respirovirus, a member of the family Paramyxoviridae that contains several highly pathogenic viruses, such as measles virus (MeV), Nipah virus (NiV), Hendra virus (HeV), Newcastle disease virus (NDV), and mumps virus (MuV) (1, 2). HPIV3, breaking out repeatedly during annual spring to early summer, is often associated with pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and bronchitis and causes a range of acute respiratory tract infections, particularly in newborns and infants (3, 4).

Like other members in the order Mononegavirales, HPIV3 is enveloped on the outside and contains an ∼17,000-nucleotide (nt)-long single-stranded genomic RNA inside, which is encapsidated by a nucleoprotein (N) and forms the highly ordered helical nucleocapsids (NCs). The helical NC is a template for viral transcription and replication (5). The phosphoprotein (P), RNA polymerase (L), and NC form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex, which is necessary for viral transcription and replication. As the largest protein of paramyxoviruses, the L contains all the polymerase activities and forms an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) complex with P (6). The P acts as a bridge to anchor the L to NC.

Like the Ns of other viruses in the family Paramyxoviridae, HPIV3 N is composed of an ordered NCORE region and an intrinsically disordered NTAIL region. The NCORE contains a globular N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal domain (CTD), flanked by NTARM and CTARM at its amino and carboxyl termini, respectively (7). Several structures of N of paramyxoviruses indicate that N has assembled or unassembled conformations. When expressed recombinantly, N binds to cellular RNAs to form NC assembly in a closed state. The RNA-binding site is on the groove between the NTD and CTD, and the NTARM and the CTARM are involved in binding to the neighboring N protomers (8). The NTAIL, due to its flexibility, is on the outside of NC and does not participate in NC assembly, but it can associate with P and adjust the looseness of NC and may further regulate the binding of the RdRp complex to RNA in NC (9–11). For paramyxoviruses, the RNA-binding groove faces the outside of the NC and determines the number of bases and the twist of RNA wrapped in each N (12–15). The P of paramyxoviruses has a modular structure containing three main stable domains: the N0 (unassembled form)-binding domain at the amino terminus, the multimerization domain (MD) that binds with L to form L-P complex (16–21), and the C-terminal domain (XD) that binds with the NTAIL serving as a bridge between NC and L (10, 22, 23). The binding and release of XD and NTAIL presumably make the RdRp complex move on the NC and synthesize RNA continuously (24, 25). The N0-binding domain of P acts as a specific chaperone, keeping N in an RNA-free conformation N0 and preventing the polymerization of N (26–28). Then, N0 is carried to the replication center by P, which is conducive to the encapsidation of synthetic RNA and avoids the degradation of RNA by host nucleases (12). However, the chaperoning mechanism of P to N and the conformational changes of N in genus Respirovirus are still a lack of knowledge.

To investigate the chaperone effect of P on N of HPIV3 and the mechanism of NC assembling, herein we reconstituted the N0-P complex and characterized its crystal structure at 3.23 Å. The complex is uniform both in solution and in crystal. The structure revealed that N0 is in an open conformation. The region (residues 22 to 42) of P is sufficient to bind with N0, and the interface between P and N0 is mainly formed by hydrophobic residues, with the binding affinity reaching a two-digit nanomolar level. Our structure-based mutagenesis experiments showed that the chaperone effect of P on N would be attenuated if conserved hydrophobic residues were mutated. Therefore, the interaction of N0-P can be used as a target for the development of antiviral drugs. We also developed a P-derived fusion peptide, which hijacked the N with 10-times higher affinity and interfered with the binding of the N to RNA, as a promising antiviral peptide inhibitor. Our data also contribute to a better understanding of the formation of NC. Based on structural analyses and bioassays, we suggested a reasonable model about the conformational transformation of N-binding RNA during viral replication.

RESULTS

The amino terminus of the HPIV3 P chaperones the N to form an unassembled N0-P complex.

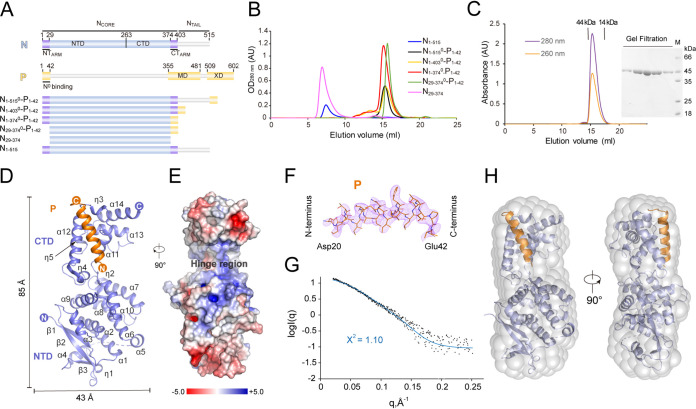

The interaction of N and P has been shown to play a critical role in the replication cycle of the virus. Previous studies indicated that the amino terminus of P can prevent premature N polymerization (29, 30). We expressed full-length N (residues 1 to 515), NTAIL removed (residues 1 to 403), and NTARM or CTARM truncated (residues 1 to 374 or 29 to 374) proteins in Escherichia coli, but the proteins formed inclusion bodies, which prevented us from obtaining significant amounts of soluble proteins. To improve the solubility of the proteins, we fused a dual His6 maltose-binding protein (MBP) tag to the N terminus of the proteins. The purified fusion proteins were soluble but formed aggregations that were eluted in the excluded volume of a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (Fig. 1A and B). Therefore, we reconstituted several variants of N0-P complex: peptide P1-42 encompassing the N0-binding region was fused to the C terminus of N proteins that truncated at the NTAIL, NTARM, or CTARM. The chimeras were purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography, followed by anion exchange and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), which indicated that the chimeras were monomeric in solution (Fig. 1A and B). The purified N0-P complexes migrated as a single band on SDS-PAGE. Because the absorbance ratio of the N29-3740-P1-42 complex at 260 and 280 nm was 0.56 (A260 nm/A280 nm), the protein sample might not contain nucleic acid (Fig. 1C). Further, by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) experiments (Table 1), the molecular weight of the reconstituted N29-3740-P1-42 complex was consistent with the monomeric result obtained from SEC. Together, these results verify that the first 42 residues of HPIV3 P maintain N0-P complex monodisperse, soluble, and free of nucleic acid.

FIG 1.

Structure of HPIV3 N0-P complex. (A) Schematic representation of HPIV3 N and P constructs used in this study. NTD, N-terminal domain of NCORE; CTD, C-terminal domain of NCORE; NTARM, N-terminal arm of N; CTARM, C-terminal arm of N; MD, multimerization domain of P; XD, X domain of P. (B) The size-exclusion chromatogram (SEC) of various HPIV3 N0-P complexes. The samples were run on Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL. N1-515, full-length protein; N1-403, NTAIL is truncated; N1-374, both CTARM and NTAIL are truncated; N29-374, NTAIL, NTARM, and CTARM are truncated. Due to the low solubility of individual expression, N1-515 and N29-374 were fused to a dual His6 maltose-binding protein (MBP) tag at the N terminus. N1-515 and N29-374 proteins were still aggregated after the tag was cut. (C) SEC of HPIV3 N29-3740-P1-42 chimera. The right panel shows Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE of protein from SEC peak. Lane M, molecular mass markers (kDa). Elution volumes of the protein standards on a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column are marked at the top of the figure, respectively. (D) View in cartoon representation of the HPIV3 N0-P structure. The N0 and P peptides are shown in slate and orange, respectively. Secondary structure elements are labeled. (E) Electrostatic surface potential of HPIV3 N0-P complex at ±5 kT/e: red (acidic), white (neutral), and blue (basic). (F) The “omit” Fo − Fc differential electron density map of P in the N0-P complex, contoured at 2.5 σ. (G) Analysis of the N29-3740-P1-42 complex by SAXS. Comparison of small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) experimental data (black) and calculated scattering profiles (blue) from the crystal structure of HPIV3 N29-3740-P1-42. The theoretical curve was calculated and fit to the experimental data using CRYSOL (62). (H) Ab initio model of the complex. The crystal structure of the complex fits well with the ab initio models calculated from SAXS data. OD260 nm, optical density at 260 nm.

TABLE 1.

Statistics of SAXS analysis

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.033 |

| Beam size (μm) | 320 × 43 |

| Exposure time (s) | 1 per frame |

| Camera length (m) | 2.68 |

| Temp (K) | 283 |

| q-measurement range (Å−1) | 0.007 to 0.355 |

| Concentrations (mg/mL) | 1.0 |

| No. collected images | 20 |

| Structural parameters | |

| I(0) (cm−1) (from P(r)) | 14.7 ± 0.1 |

| Rg (Å) (from P(r)) | 27.9 ± 0.2 |

| I(0) (cm−1) (from Guinier) | 15.2 ± 0.27 |

| Rg (Å) (from Guinier) | 29.0 ± 0.7 |

| Dmax (Å) | 86.0 |

| Porod vol Vp (Å3) | 49,300.0 |

| Molecular mass (kDa) | |

| Calculated from Porod vol Vp | 40.9 |

| Calculated from protein sequence | 42.0 |

| Calculated from program SAXS MoW | 43.9 |

| Software employed | |

| Primary data reduction | BioXTAS-RAW (58) |

| Data processing | GNOM (59) |

| Ab initio analysis | DAMMIN (60) |

| Computation of model scattering | CRYSOL (62) |

| Validation and averaging | DAMAVER (61) DAMSEL (61) DAMFILT (61) SUPCOMB (63) |

Crystal structure of the HPIV3 N0-P complex.

To explore the relationship between function and structure of N and P, we expressed and purified several HPIV3 N0-P complexes. After extensive crystallization trials, we luckily obtained crystals of N29-3740-P1-42 complex that could be used for diffraction. The HPIV3 N0-P complex was crystallized in the space group I422. We determined the structure at a resolution of 3.23 Å by molecular replacement using the MeV N-RNA complex structure (Protein Data Bank [PDB] code 6H5Q) (31) as a template (Fig. 1D; Table 2). The final structural model contained a chimeric molecule in the asymmetric unit. The amino acid sequence of the N29-3740-P1-42 chimera structure was traced from P residues 20 to 42 and from N residues 29 to 374 except residues 136 to 153. The data collection and model refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics of HPIV3 N29-3740-P1-42

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength | 0.979 |

| Space group | I 4 2 2 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 117.1, 117.1, 143.2 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0 to 3.23 (3.29 to 3.23)a |

| Rmerge (%) | 9.8 (61.3) |

| Mean I/σ (I) | 18.1 (1.8) |

| CC1/2 | 1.0 (0.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (99.5) |

| Total no. of reflections | 56,267 |

| Unique reflections | 8,248 (395) |

| Multiplicity | 6.8 (5.3) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0 to 3.23 (3.29 to 3.23) |

| No. of reflections | 7,630 (399) |

| Rwork (%)b | 21.9 |

| Rfree (%)c | 23.8 |

| No. of atoms | 2,708 |

| Protein | 2,654 |

| Water | 54 |

| Avg B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 51.25 |

| Water | 26.66 |

| RMSD | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.411 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Favored regions | 98.8 |

| Allowed regions | 1.2 |

| Disallowed regions | 0 |

Statistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Rwork = Σ(‖Fp(obs)| − |Fp(calc)‖)/Σ|Fp(obs)|.

Rfree is an R factor for a preselected subset (5%) of reflections that was not included in refinement.

The overall structure of HPIV3 N29-3740-P1-42 adopts a bean-like architecture with approximate dimensions of 85 Å in height and 43 Å in width (Fig. 1D). The HPIV3 NCORE mainly contains two major domains, the NTD (residues 29 to 263) and the CTD (residues 264 to 374), both of which are predominantly α-helices. The NTD domain is formed by α1 helix to α10 helix, two 310 helices η1 and η2, and three β-sheets β1 to β3 (Fig. 1D). The CTD domain is formed by α11 helix to α14 helix and three 310 helices, η3 to η5. Electrostatic analysis revealed that the electrostatic surface charge is distributed asymmetrically with negative charge clusters at the NTD and CTD domains, defining a basic hinge region that provides a putative site for RNA binding (Fig. 1E). P20-42 forms a helix about 24 Å long, binding to the groove formed by the α11, η3, and α12 helices of the N (Fig. 1D and F). SAXS experiments reveal that the complex conformation in the crystal is consistent with that in the solution (Fig. 1G and H).

The residues 22 to 42 of P is sufficient to interact with N.

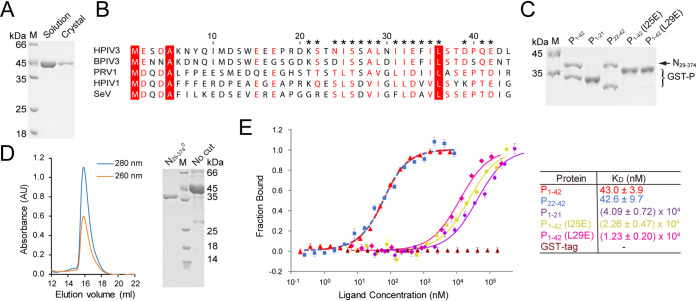

The residues 1 to 19 of P were not traceable in the electron density map, but proteins from several crystals were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and only one band was found at 44 kDa (Fig. 2A), consistent with the chimeric molecular weight, indicating no obvious degradation during crystallizing. Thus, the region (residues 1 to 19) of P may be flexible. In addition, the primary sequence alignment of P in respiroviruses implies that the conserved region bound to N may be located at residues 22 to 42 of HPIV3 P (Fig. 2B). To evaluate the role of the region (residues 1 to 21) of P in N0 binding, we performed pulldown assays of N29-374 when coexpressed with glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged P1-42 and its truncations (Fig. 2C). P1-42 and truncation P22-42 could efficiently bind N29-374, while the P1-21 truncation could not. The differences in affinity require further determination. To obtain RNA-free and P-free N0, we designed and expressed a mutated chimeric protein N-TEV-P1-42 (L29E) (His6 tag at its C terminus) in E. coli. After being cleaved by tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, the protein was further purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography, followed by anion exchange and SEC (Fig. 2D). Microscale thermophoresis (MST) binding experiments showed that residues 1 to 21 of P had little effect on the affinity between N29-374 and P1-42 (Fig. 2E). Thus, residues 22 to 42 of P are sufficient to interact with N.

FIG 2.

The P22-42 is enough to bind N0. (A) SDS-PAGE of HPIV3 N0-P complex in solution (lane 2) and crystal (lane 3). Lane M, molecular mass markers (kDa). (B) Alignment of the P peptide of typical respiroviruses. Asterisks represent residues binding to N0. The identical residues are highlighted in red, and similar residues are in red type. The following viral proteins were used: HPIV1 (human respirovirus 1) P (UniProtKB-P32530), SeV P (P14252), PRV1 (porcine respirovirus 1) P (S5LVM8), BPIV3 (bovine respirovirus 3) P (P06163), and HPIV3 P (P06162). (C) Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE of GST pulldown of N29-374 by GST-P1-42 or its mutants when coexpressed in E. coli. Lane M, molecular mass markers (kDa). Note that some mutations affect electrophoretic migration rates in SDS-PAGE (7). (D) SEC of HPIV3 N29-3740 (right panel) Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE of protein from the SEC peak (lane N29-3740). Lane M, molecular mass markers (kDa). The lane labeled “No cut” shows crudely purified protein that has not been cleaved by TEV enzyme. (E) Measurement of the binding affinity of the P peptide or mutations with N29-3740 by microscale thermophoresis (MST). The experiments were repeated three times.

The interaction between N0 and the amino terminus of P is mainly hydrophobic.

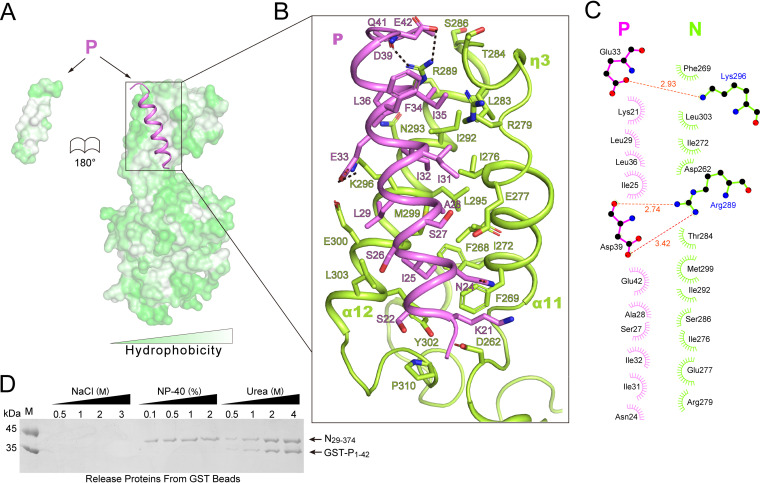

The crystal structure shows that the P20-42 docks to the hydrophobic pocket formed by the helices α11, η3, and α12 of the CTD domain of N0 (Fig. 3A and B) (32). The buried surface area in the crystallized complex is about 800 Å2, and the interface is mostly composed of hydrophobic residues (Fig. 3B and C). Most residues of P20-42, such as Ile-25, Leu-29, Ile-31, Ile-32, and Ile-35, form hydrophobic interaction with N0, and two residues of P20-42 form hydrogen bonds with N0. The hydrophobic interface was also determined by screening dissociation of N0 from P1-42 under different conditions (Fig. 3D). The screening conditions involve hydrophobic and ionic interactions. NaCl concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 3 M did not cause the release of N0, whereas conditions containing Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) did. Conditions containing urea of different concentrations led to denaturing and releasing the complex from agarose beads (Fig. 3D). These results are consistent with those of MeV (7). Thus, hydrophobic interactions make a major contribution to N0-P complex formation. We also coexpressed N29-374 and GST-P1-42, as well as its mutants. Wild-type P1-42 efficiently bound N29-374, whereas mutants at the core hydrophobic interface with negatively charged residues (I25E or L29E) greatly reduced their binding to N (Fig. 2C, lanes 5 and 6). Consistently, MST binding experiments also showed that these two mutations in P significantly reduced the affinity for N (Fig. 2E).

FIG 3.

Hydrophobic interaction between N0 and P. (A) The hydrophobic surface of N0 and P peptide (purple cartoon). (B) Closeup view of the binding interface between N0 and P peptide. The interaction residues are shown as sticks, respectively. Oxygen is shown in red, and nitrogen is shown in blue. Hydrogen bonds are represented by black dotted lines. (C) Details of the interactions between the N0 and P peptides were calculated by Ligplot, setting hydrogen-bonds parameters, maximum distances D-A of 3.5 Å and H-A of 2.7 Å, and hydrophobic contacts parameters. Maximum and minimum distances were 3.9 and 2.9 Å, respectively (32). (D) The effect of buffer components on the binding of N to P. SDS-PAGE profile of proteins released from GST-P1-42 and N29-374 complex bound to GST beads, when subjected to different conditions. The dosages (final concentrations) are listed at the top. Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) caused N0 to release from GST-P1-42. Urea induced the denaturation of the complex to release from agarose beads.

Unique features of HPIV3 N0-P structure.

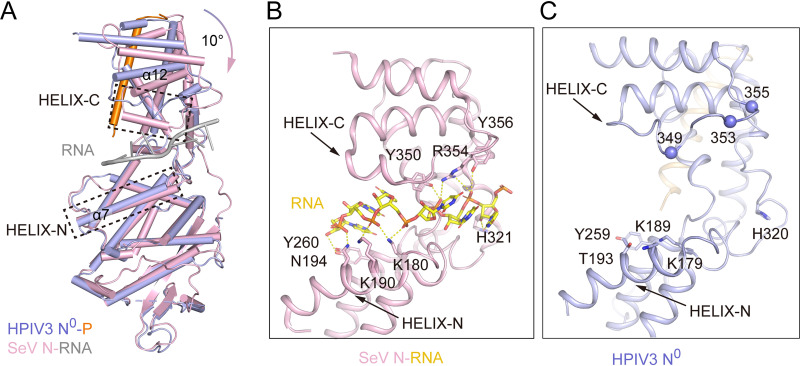

When we prepared the manuscript, several closed states of Sendai virus (SeV) N-RNA structure were published online (33). The sequence identity of the N between HPIV3 and SeV is 59%, which allows us to use the helical NC of SeV as the NC of HPIV3 to compare and analyze the assembled and unassembled conformations of HPIV3 N. The structures of HPIV3 unassembled N0 and SeV assembled N in NC are similar with the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 2.0 Å (HPIV3 N0 as the reference, all residue coverage). The RMSD values are 1.1 Å for the NTD domain and 1.7 Å for the CTD domain (HPIV3 NTD and CTD as the reference, all residue coverage), but there is an ∼10° relative rotation of these two domains around the hinge region (Fig. 4A). Theoretically, the RNA-binding groove of N in the HPIV3 N0-P is open with the CTD domain lift up and has a larger cavity volume, readying to bind single-stranded RNA (ssRNA). However, the binding positions of P and ssRNA are opposite at the N, so P does not directly block the RNA-binding site. The N has no sequence specificity for RNA binding, and the two motifs located in the NTD and CTD domains (HELIX-N and HELIX-C) form a tweezers-like structure, which is critical for binding RNA. In these two motifs of SeV N, the residues (K180, K190, N194, Y260, H321, Y350, R354, and Y356) that form hydrogen bonds/salt bridges with the RNA phosphate backbone are almost conserved in the HPIV3 N0. However, due to the conformational difference and the deflection of the side chains of these residues, none of these residues on HPIV3 N0 is in the right position to bind RNA (Fig. 4B and C).

FIG 4.

Structural superposition of HPIV3 N0-P and SeV N-RNA shows conformational changes. (A) Structural comparisons of HPIV3 N0-P and SeV N-RNA complex (PDB code 6M7D) (33). HPIV3 N0 (slate), HPIV3 P (orange), SeV N (pink), and RNA (gray) were bound to SeV N. The key motifs HELIX-N (motif of NTD domain) and HELIX-C (motif of CTD domain) involved in RNA binding were framed by black dotted lines. Superposing at their NTD domains shows their respective CTDs at an angle of about 10°. (B) Closeup view of RNA-binding groove of SeV N in its closed conformation. Conserved residues (K180, K190, N194, Y260, H321, Y350, R354, and Y356) involved in RNA binding are shown as sticks, and hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dotted lines. (C) The closeup view of RNA-binding groove of HPIV3 N0. The residues that correspond to those in panel B are shown. Structure superimpositions were carried out using DALI (http://ekhidna2.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali/). Using the HPIV3 N0 as the reference, an RMSD value of 2.0 Å was obtained over all residue coverage.

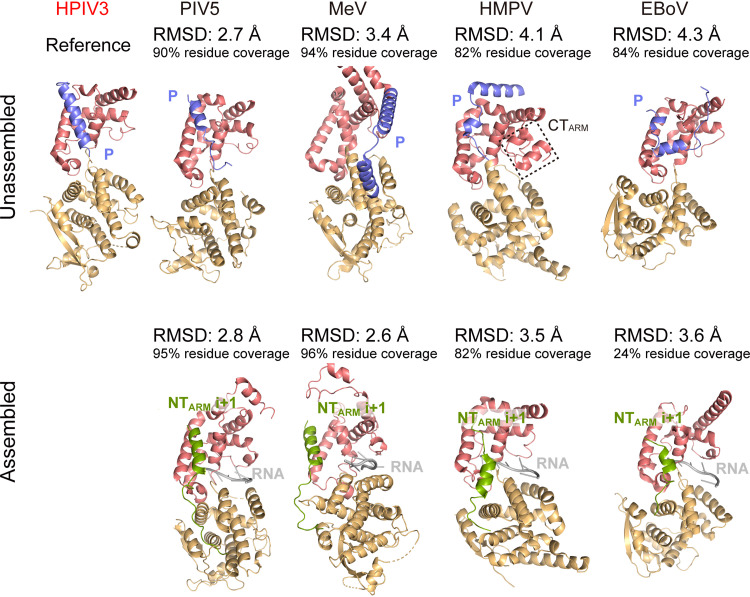

The assembled (N-RNA) and unassembled (N0-P) structures of the N of some viruses in the order Mononegavirales have been resolved (2, 7, 12, 15, 31, 34–37). The structures of N in unassembled and assembled states of other viruses (MeV, parainfluenza virus 5 [PIV5], human metapneumovirus [HMPV], and Ebola virus [EBoV]) were compared with HPIV3 N0, respectively (Fig. 5). The NTD and CTD domains of N at the unassembled state of all these viruses are relatively rotated and far away from each other; in particular, the CTD and NTD of MeV N have about 40° relative rotation in the open and closed conformations (7). However, the DALI server calculation indicated that the HPIV3 N0 structure in the open state is similar to the assembled N of SeV and those viruses, revealing that HPIV3 N might not undergo significant conformational changes during NC assembly and has a unique mechanism (Fig. 4 and 5) (38).

FIG 5.

The structures of N from different viruses in Mononegavirales. The upper and lower panels show the unassembled and assembled Ns, respectively. The NTD domain and CTD domain of N are shown in light orange and dark salmon, respectively. P is shown in slate), NTARM of N(i + 1) is shown in green, and RNA is shown in gray. The following viral structures were used: PDB code PIV5 (Paramyxoviridae), unassembled (5WKN), assembled (4XJN); MeV (Paramyxoviridae), unassembled (5E4V), assembled (6H5Q); HMPV (Pneumoviridae), unassembled (5FVD), assembled (5FVC); EBoV (Filoviridae), unassembled (6OAF), assembled (5Z9W) (2, 7, 12, 31, 35–37). Structure superimpositions were carried out using DALI. Using the HPIV3 N0 as the reference, the RMSD value and residue coverage are marked.

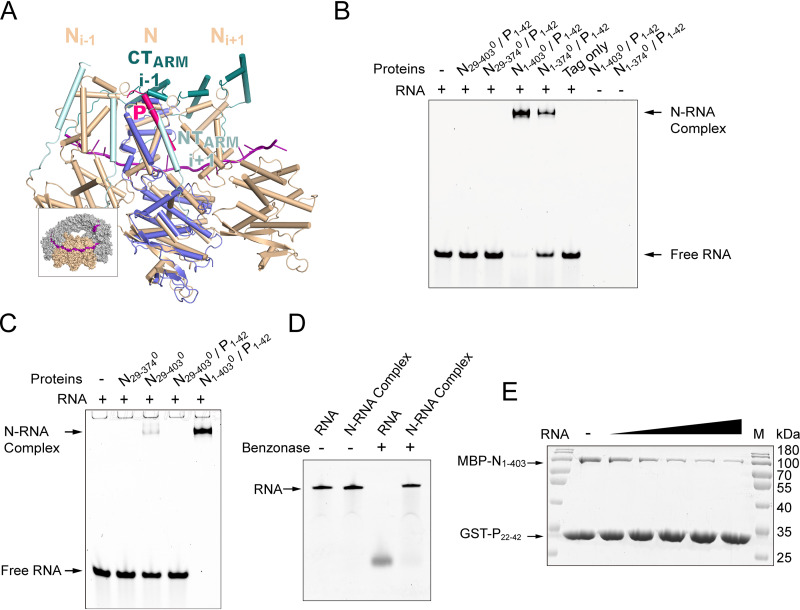

The mechanism of HPIV3 N binding to RNA.

To further understand the binding of HPIV3 N to RNA, a model for the assembled state of HPIV3 NC was built according to the helical NC of SeV (Fig. 6A). The comparison between N0-P and N-RNA showed that the P peptide and NTARM of Ni+1 protomer competed for the same binding site (Fig. 6A). NTARM provides several important binding sites for the assembly of adjacent N. In the SeV NC-like structure, the binding interface area between NTARM of Ni+1 protomer and adjacent N protomer exceeds 1,000 Å2 by several hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and hydrophobic interactions. Therefore, the P peptide maintains the monomeric state of N by interfering with the interaction between N protomers. However, in the N-RNA closed state, the nucleic acid induces the conformational changes of the N protomers and the association between the N protomers, making them arrange in an orderly manner along with the RNA. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiment for N0-P of NiV showed that the flexible resonances of NTARM and CTARM disappeared, but the resonances of P could be detected upon the addition of RNA (39). Therefore, we hypothesized that P might be replaced by NTARM of adjacent N within the coparticipation of NTARM and CTARM of adjacent Ns during NC assembly. To verify our hypothesis, we tried electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) experiments. The results showed when different truncations of the N in the unassembled state of N0-P were incubated with RNA, all the fragments containing the NTARM bound RNA (Fig. 6B). Fragment N1-403 containing both NTARM and CTARM had a higher binding ability than fragment N1-374 containing NTARM alone (Fig. 6B). Fragment N29-403 that contained only CTARM could bind to RNA weakly when the P peptide was removed (Fig. 6C). However, fragment N29-374, in the absence of both NTARM and CTARM, hardly bound to RNA even if P was removed (Fig. 6C). In addition, N protected RNA from degradation by nucleases (Fig. 6D). Moreover, competitive binding experiments further illustrated that the addition of RNA does cause P peptide to dissociate from N (Fig. 6E). Therefore, in the process of N binding to RNA, NTARM is the main competitor of P peptide, and CTARM will further promote the position exchange of P with NTARM. Because the binding sites of P and RNA on N are different, RNA-binding or P-binding switches the closed or open conformations conveniently.

FIG 6.

The mechanism of HPIV3 N binding to RNA. (A) Superposition of HPIV3 N0-P with a SeV N protomer in helical NC. SeV N is in wheat, NTARM is in cyan, CTARM is in dark teal, RNA is in purple, HPIV3 N0 is in slate, and HPIV3 P peptide is in hot pink. The inset shows the localization of the SeV three N protomers within the NC. Structure superimpositions were carried out using PyMOL. Using the HPIV3 N0-P as the reference, the RMSD value between SeV N-RNA (PDB code 6M7D) and HPIV3 N0 is 2.0 Å over all residue coverage. (B) EMSA of different HPIV3 N truncations in N0-P with ssRNA. The amino terminus of N and P are fused with the MBP and glutathione S-transferase (GST) tags, respectively. Lane 1 shows ssRNA. Lanes 2 to 6 show ssRNA incubated with N29-4030/P1-42 (lane 2), N29-3740/P1-42 (lane 3), N1-4030/P1-42 (lane 4), N1-3740/P1-42 (lane 5), and MBP tag and GST-P1-42 (lane 6). Lanes 7 and 8 show only N1-4030/P1-42 and N1-3740/P1-42. The bound and free ssRNAs were labeled on the side. The ssRNA was detected by the FAM signal. The experiments were repeated three times. (C) EMSA of HPIV3 N0 truncations with ssRNA. Lane 1, ssRNA only. Lanes 2 to 5, ssRNA incubated with N29-3740 (lane 2), N29-4030 (lane 3), N29-4030/P22-42 (lane 4), and N1-4030/P22-42 (lane 5). (D) RNA or N-RNA complex was digested with benzonase nuclease and analyzed by a 20% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel. N-RNA complex was obtained by incubating N1-4030/P1-42 complex with ssRNA. The experiments were repeated three times. (E) Affinity competitions of ssRNA and P for N. The coexpressed MBP-N1-403 and GST-P22-42 were incubated and bound with the GST beads, and then increasing concentrations of ssRNA were added. Lane M, prestained protein ladder.

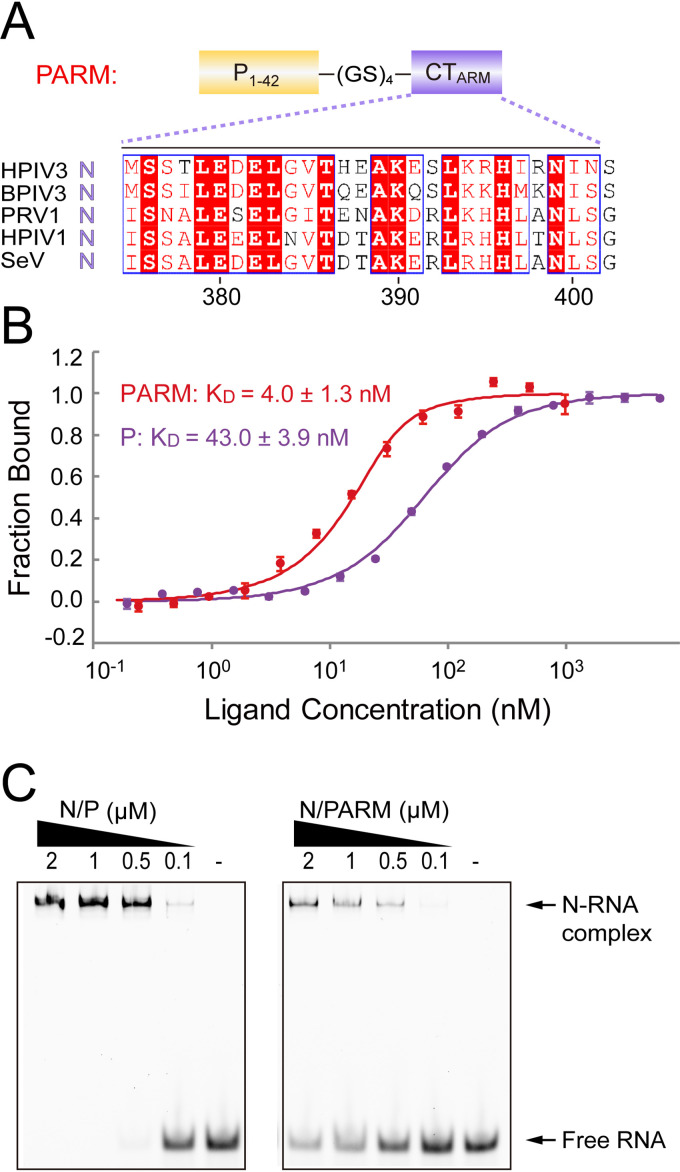

P-derived peptide as an antirespirovirus inhibitor.

The presence of high conservation of N and P in the genus Respirovirus could facilitate the development of inhibitors to treat infections. To increase the binding affinity, we tested several mutations of P but failed (data not shown). Therefore, we tried other kinds of mutations. Because the P peptide and the CTARM of adjacent Ni-1 protomer within the NC are relatively close in three-dimensional structure (Fig. 6A) and the CTARM participates in binding N to stabilize the NC, we hypothesize that the fusion of the CTARM to the P peptide might increase the binding affinity to N. To verify this hypothesis, we designed and purified a peptide (named PARM) in which the P1-42 peptide and the CTARM were connected by a (GS)4 linker and observed an ∼10-fold increased binding affinity to N (KD, PARM: 4.0 ± 1.3 nM versus P: 43.0 ± 3.9 nM) (Fig. 7A and B). We next assessed the effect of the PARM in the process of N binding to RNA. In the presence of PARM, the binding ability of N to RNA was significantly reduced (Fig. 7C). For the virus, the appropriately medium affinity between N and P is very important for NC assembly, because P needs to depart from N at the right time under the combined action of adjacent N protein and RNA. However, the PARM has greatly strengthened its connection with N and inhibits the binding of N to RNA; that is, the PARM hijacks N. Because of the essential role of N in viral RNA transcription and replication, the PARM with affinity in the low nanomolar range might be used as an antiviral peptide inhibitor targeting N.

FIG 7.

P-derived peptide targets N stronger than P peptide. (A) Schematic representation of the peptide PARM. Sequence alignment of the conserved CTARM of the genus Respirovirus. The identical residues are background-shaded red in blue squares, and similar residues are red text in blue squares. The following vrial proteins were used: HPIV1 N (UniProtKB-P26590), SeV N (Q07097), PRV1 N (S5LSJ0), BPIV3 N (P06161), and HPIV3 N (P06159). (B) Measurement of the binding affinity of the PARM and P1-42 peptide with N29-3740 by MST. The experiments were repeated three times. (C) EMSA of HPIV3 N1-403/P1-42 (abbreviated as “P”) and N1-403/PARM with ssRNA. PARM bound N stronger than P, inhibiting the binding of RNA to N. The concentration of ssRNA was kept constant at 0.1 μM, while the concentration of protein increased gradually.

DISCUSSION

In our structure, the P locates at the CTD domain of N0, which is consistent with all published N0-P structures. We provided evidence demonstrating that residues 22 to 42 of HPIV3 P are enough to maintain the N at an unassembled conformation. Although we were not able to get the structure of HPIV3 P1-19 due to the lack of density map, via MST and GST pulldown experiments we proved that the region has little effect on N0 binding (Fig. 2). In the structure of the HPIV3 N0-P complex, N0 is unassembled and in an open conformation, suggesting that the conformational change induced in HPIV3 N upon binding RNA might be more subtle than is the case in MeV, PIV5, EBoV, and HMPV (Fig. 5).

The chaperone functions of P.

Based on our solved structures, when the key hydrophobic residues of P in the interface are mutated to negatively charged ones, the affinity of P mutants to N0 would be significantly reduced, indicating the compromised chaperone function of these P mutants. It came to us that we can obtain a P-free N0 with the help of this weak chaperone function. By coexpressing with these P mutants, the RNA-free and P-free HPIV3 N0 was successfully obtained, and thus the affinity value of N0 binding to P was measured at the first time (Fig. 2D and E). Because the interacting residues between P and N0 are conserved in the family Paramyxoviridae, this method might be applied to other paramyxoviruses.

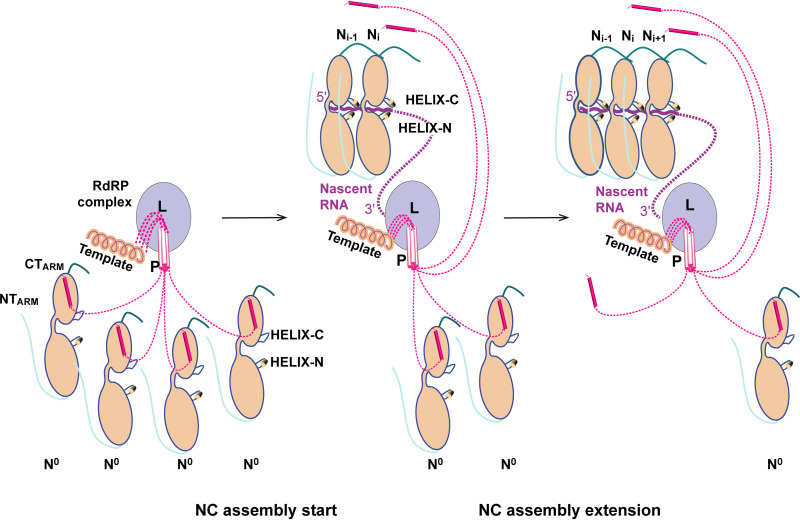

The chaperone P is very important for virus replication. Because the RdRp complex cannot recognize the naked RNA and the nascent RNA needs to be protected from degradation by the host, the P carries the N0 to the replication center, encapsulating sense RNA and offspring RNA (12). The P and the NTARM of the Ni+1 protomer in NC might share a partially overlapping binding site at the CTD domain of N (Fig. 6A). In the process of N0-P binding to RNA, N will undergo a conformational change. The HELIX-C, which is a loop and very flexible originally, might be induced by RNA to form a helix to stabilize RNA, and the side chains of the HELIX-N will rearrange (Fig. 4). Therefore, we suggest a reasonable model for the conformational transition of N-binding RNA during viral replication (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

Schematic model of nucleocapsid (NC) assembly. The L (light blue) and P (pink) proteins form RdRp (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) complex. The C-terminal domain of P binds to template (solenoid shape), and the N-terminal domain of P binds to N0 (wheat). RNA is shown in purple. RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

In this model, RNA is synthesized by the L-P complex and extended in the direction of 5′-end to 3′-end. The N0 is carried by the P and binds to RNA from the 5 '-end, but only one N0 protein is not enough to bind RNA. The P continues to carry more N0 to the replication center. When there are more than two N0, the CTARM of Ni-1 binds to the CTD domain of Ni, and the NTARM of Ni exchanges with the P on Ni-1, and then the P is released. In the participation of RNA, the Ni-1 grasps the RNA through conformational changes of these two motifs (HELIX-C and HELIX-N) at the hinge region and becomes closed (Fig. 8). Once Ni-1 completes the binding of RNA, it will promote the same conformational change of its tightly bound Ni. The next P will begin to be dissociated under the spatial conflict of CTARM, and more RNA will be bound. The binding process of Ni will be greatly strengthened by the NTARM of Ni+1 when Ni+1 is carried to the RNA synthesis site. This triggers a subsequent chain effect, leading to the extension of the nucleocapsid assembly (Fig. 8). Our model is supported by the following phenomena. First, the P of SeV that belongs to the same genus as HPIV3 is a tetramer (16, 20). Therefore, the P can carry four Ns to the replication site at the initial stage of NC assembly. Second, MeV N bound 6-nt ssRNA to form NC, but one 6-nt ssRNA was distributed in grooves of two Ns in NC, indicating that two Ns are jointly involved in the binding of the ssRNA (31).

The N0-P interface as an antiviral target.

The interaction of N0 and P is very important for the life cycle of the virus. Disruption of the interaction between N0 and P could lead to failure of viral RNA encapsidation and degradation of viral RNA, inhibiting viral growth (12, 40). The importance of the N in viral transcription and replication makes it an attractive target for developing broad-spectrum antiviral inhibitors. In fact, the N of other negative-strand viruses as a drug target has been maturely studied. For example, small-molecule replication inhibitors were developed by targeting the nucleoprotein (NP) of the influenza virus, triggering NP aggregation and inhibiting its nuclear accumulation (41, 42). The amino terminus of P of NiV, RSV, and EBoV binding to N0 as a peptide inhibitor can effectively inhibit virus replication in cells (40, 43, 44). The modification of RSV P containing three domains (oligomerization, L-binding, and nucleocapsid binding) has maximum inhibitory activity (45). In response to the N and P interaction of EBoV and RSV, a range of small-molecule inhibitors have been identified by high-throughput screens (46, 47). Thus, the development of small-molecule inhibitors or peptide drugs to interfere with the binding of N and P provides a new strategy for antiviral therapy. Here, the P-derived PARM peptide inhibitor we designed is also aimed at the N0-P interface (Fig. 7). It was verified in vitro to interfere with the assembly of N and RNA by hijacking the N. Furthermore, PARM can be fused with a nuclease to design a peptide drug conjugate (PDC), like capsid-nuclease fusion proteins (48, 49). The PDC may not only inhibit the binding of N to RNA but also carry the nuclease to the virus replication center to degrade the virus RNA by using the targeting effect of PARM to N, causing a more in-depth antiviral effect (48, 49). Due to the high conservation of P and N of the genus Respirovirus, the PARM may have broad-spectrum antiviral activity, which requires further in vivo experiments to illustrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression, and purification.

All constructs were derived from reverse-transcribed N gene (GenBank accession number D10025.1) (N45D mutation) and P gene (GenBank accession number M14932.1) of HPIV3 strain NIH 47885 (a gift from Mingzhou Chen). Various fragments of genes for N or P were PCR-amplified and subcloned into pET28a (for N-terminal His6 tag or dual His6-MBP fusion tag) or pGEX-6P-1 (for N-terminal GST-tag) vectors via the BamH I/XhoI restriction sites with a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site as a previous publication for recombinant protein expressions (50).

For the N29-3740-P1-42 chimera connected by a (GS)4 linker, the N29-374 and P1-42 coding sequences were amplified by PCR to generate megaprimers with overlapping sequences. Then, the megaprimers were annealed and extended. The product was subcloned into the bacterial pET28a expression vector, which contained a TEV protease cleavage site following the N-terminal His6 tag and a stop codon introduced at the 3′-end. Mutations in the P constructs were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis.

Proteins were expressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) (Merck Millipore). Cells were grown at 37°C until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 to 1.0. Expression was induced by supplementing 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and was allowed to proceed for 12 h at 16°C. The cells were collected by low-speed centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Bis-tris propane, pH 8.4, 1 M NaCl, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). The cells were lysed by sonication and centrifuged at 40,200 × g for 45 min to separate the cell debris. The supernatant was collected and applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) column or GST affinity column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed three column volumes, and the protein was eluted by using imidazole in concentrations ranging from 20 to 300 mM in buffer (20 mM Bis-tris propane, pH 8.4, 1 M NaCl) or using 10 mM reduced glutathione (GSH). The eluted protein fractions were concentrated with Millipore Amicon Ultra 30-kDa-cutoff spin concentrators to remove imidazole or GSH. The N-terminal His6 tag was then cleaved by TEV protease overnight at 4°C, and the protein was further purified by anion exchange (Q Sepharose, GE Healthcare). The elution was then applied to a size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare). The major peak fractions were pooled and concentrated as described above. All the protein purification procedures were performed at 4°C.

For the coexpression of the N and P constructs, pET28a-N and pGEX-6P-1-P plasmids were cotransformed into BL21(DE3) cells (Merck Millipore). Protein expression and purification process were similar to that described above. Briefly, after cell growth, expression, and ultrasonic disruption, the supernatant was collected and applied to a GST affinity column (GE Healthcare). Then, the elution was further purified by ion-exchange chromatography followed by SEC in buffer (20 mM Bis-tris propane, pH 8.4, 1 M NaCl).

Only inclusion bodies or aggregations were formed when N proteins were expressed alone. To obtain the homogeneous N0 protein, the mutant P1-42 (L29E), which interacted with N weakly and worked as a compromised chaperone, was fused to N. The pET28a-N-TEV-P1-42 (L29E) (a His6 tag at the C terminus) plasmids were constructed and transformed into BL21(DE3) cells. After induction by IPTG, the cells were collected, resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Bis-tris propane, pH 8.4, 1 M NaCl, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1 mM PMSF), and then lysed by sonication. The protein was purified in three steps. The cleared supernatant, supplemented with 20 mM imidazole, was loaded to an NTA resin. The resin was washed with three column volumes buffer (20 mM Bis-tris propane, pH 8.4, 1 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole) and eluted in 5 column volumes elution buffer (20 mM Bis-tris propane, pH 8.4, 1 M NaCl, 400 mM imidazole). After being cleaved by TEV protease, the eluent was applied to an NTA resin, and the flowthrough (contains only N0) was concentrated with Millipore Amicon Ultra 30-kDa-cutoff spin concentrators and loaded on ion exchange (Q Sepharose, GE Healthcare), followed by Superdex Increase 200 10/300 GL column. Thus, we purified the N29-3740 and N29-4030. However, the N0 truncations containing NTARM (residues 1 to 28) led to the formation of inclusion bodies or aggregations, with almost no homogeneous proteins obtained, which could not be purified a step further.

Crystallization and structure determination.

The purified protein was concentrated to about 10 mg/mL. Crystals of the N29-3740-P1-42 chimeric protein were grown by sitting-drop vapor diffusion (4°C) by mixing 1 μl of protein with 1 μl of reservoir (15% [wt/vol] polyethylene glycol 3350, 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.0, 0.1 M magnesium chloride, 5 mM nickel (II) chloride) after 2 weeks, but the diffraction was poor. The diffraction qualities were not improved after extensive optimization by various concentrations and species of precipitants, buffer, salt, additives, and detergents. After the long-standing trials, final crystals were grown by seeding at 4°C with a solution containing 20% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 6000, 0.1 M cacodylic acid sodium, pH 6.5, 20 mM nickel (II) chloride. All crystals were cryoprotected in mother liquor containing 25% (wt/vol) glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The diffraction data were collected on Beamlines BL17U1 and BL19U1 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. All of the data were processed using HKL2000 (51).

The structure was determined by molecular replacement (MR) using BALBES (52) in the CCP4, and the best solution stopped at Rwork/Rfree values of 0.374/0.450 using MeV N (PDB code 6H5Q) (31) as a search model. The model was then manually built using the program COOT (53) and refined using REFMAC5 (54) in iterative cycles. The structure was finally refined to 3.23 Å in the space group I422, with an Rwork of 21.9% and an Rfree of 23.8%. Coordinates and structure factor amplitudes have been deposited in the PDB under accession number 7EV8. The data collection and processing statistics are summarized in Table 2. To confirm the conformation of NTD relative to CTD, we split the N structure of 5E4V (7) into two domains, NTD and CTD, and deleted the flexible loop of NTD. The CTD domain structures both with and without the P structure were tried. The modified structures were used as search models, but the results of MR from BALBES were still very bad. We then used PHASER-MR (full-featured) in PHENIX (55) to MR and set ensemble1 with NTD and ensemble2 with CTD, and the strategy was set to first search ensemble1 and then search ensemble2. The initial solution was seemingly rational, with log-likelihood gain/translation function Z-score (LLG/TFZ) values of 159/11.9, and the primitive density map had a relatively clear outline. We manually adjusted the initial structure in COOT and optimized it with REFMAC5; the Rwork/Rfree values were 0.413/0.456. After more than 90 cycles of manual rebuilding and refining, the best solution stopped at Rwork/Rfree values of 0.217/0.256. All structural figures were prepared by using the PyMOL program (56).

N0-P heterocomplex interaction experiments.

To detect the interaction between different P constructs and N29-3740, all of the P constructs were coexpressed with N29-374. The cells were lysed by sonication in buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1 mM PMSF). The cleared lysates were incubated with glutathione beads for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times and then eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione. Protein elution was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

For the dissociation of N29-3740-P1-42 in different solutions, pET28a-N29-374 and pGEX-6P-1-P1-42 were cotransformed and coexpressed, and then the complex was bound to glutathione beads (Thermo Scientific). To test the stability of the complex, the beads were eluted with different buffers: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 supplemented with one of the following: NaCl at 0.5, 1, 2, or 3 M; NP-40 at 0.1, 0.5, 1, or 2%; or urea at 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 M. The supernatant of the released proteins was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

For the competition between RNA and P for N, about 200 nM MBP-N1-403 and GST-P22-42 complex was bound to glutathione beads in a 500-μl mixture buffer (containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA). After three times washes with the mixture buffer, the beads were incubated with the increasing concentrations (0, 20, 100, 200, 500, and 1,000 nM) of single-stranded RNA (sequence: 5′-[6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)]-AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA-3′; the poly(A) sequence was used because N is not specific to RNA sequence) in a 200-μl mixture buffer overnight at 4°C, separately. The beads were washed three times and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

EMSAs.

About 0.2 μM ssRNA (sequence is shown above) was incubated with 2 μM different MBP-N constructs and GST-P1-42 complex in a 20-μl reaction mixture (containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 6% [vol/vol] glycerol) overnight at room temperature, and 4 μl of the mixture was then separated on a 7% native polyacrylamide gel (80:1) in 0.5 × TBE buffer (45 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA). The FAM-ssRNA signal was detected by 488-nm excitation.

Benzonase digestions.

About 0.2 μM ssRNA (used in EMSA) was incubated with 2 μM MBP-N1-403 and GST-P1-42 complex overnight at room temperature to form an N-RNA complex. The ssRNA and N-RNA complex were digested by benzonase (final concentration, 0.01 mg/mL) for 1 h at 30°C. Digested samples were visualized by running a 20% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel, and the FAM-ssRNA signal was detected by 488-nm excitation.

Microscale thermophoresis.

The binding affinities between P1-42 and N29-3740 were measured using the Monolith NT.115 (NanoTemper Technologies). The N29-3740 protein was fluorescently labeled according to the manufacturer's procedure of RED fluorescent dye NT-647. Wild-type and mutated GST-P1-42 proteins were mixed with labeled N29-3740 in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA). After incubation for 10 min, the samples were loaded into silica capillaries (NanoTemper Technologies), and temperature-induced fluorescence changes were measured at 24°C by using 20% light-emitting diode (LED) power and 40% MST power. Data analysis was performed by using NTAnalysis software (NanoTemper Technologies). There is 95% confidence, and the Kd value is within the given range. The values of faction bound are transformed from the original MST data “Fnorm.” The experiments were repeated three times.

Small-angle X-ray scattering.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) data were collected at Beamline BL19U2 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) following previously published methods (57). N29-3740-P1-42 was subjected to SEC in the buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol). The scattering data from the buffer alone were measured before and after each sample measurement. The average of the scattering data was used for background subtraction using RAW (58). The ATSAS packages were used for subsequent data processing (59). Ab initio low-resolution bead models of the N29-3740-P1-42 were generated from the scattering curves using the program DAMMIN (60). Twenty independent models were aligned, averaged, and filtered with SUPCOMB, DAMFILT, DAMSEL, and DAMAVER (61). The fitting of the theoretical scattering curves between models and the experimental data were calculated using CRYSOL (62). All figures were generated with PyMOL (56). The final statistics for data collection and scattering-derived parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Data availability.

Final refined coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession code 7EV8.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff of Beamlines BL19U1, BL19U2, and BL17U1 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for the excellent technical assistance. We thank Mingzhou Chen for generously providing reverse-transcribed N and P genes of the HPIV3 wild-type isolate.

This work was supported financially by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2018YFE0113100) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31872713 and 32071210).

Contributor Information

Zhongzhou Chen, Email: chenzhongzhou@cau.edu.cn.

Rebecca Ellis Dutch, University of Kentucky College of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henrickson KJ. 2003. Parainfluenza viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 16:242–264. 10.1128/CMR.16.2.242-264.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal M, Leser GP, Kors CA, Lamb RA. 2018. Structure of the paramyxovirus parainfluenza virus 5 nucleoprotein in complex with an amino-terminal peptide of the phosphoprotein. J Virol 92:e01304-17. 10.1128/JVI.01304-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeGroote NP, Haynes AK, Taylor C, Killerby ME, Dahl RM, Mustaquim D, Gerber SI, Watson JT. 2020. Human parainfluenza virus circulation, United States, 2011–2019. J Clin Virol 124:104261. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branche AR, Falsey AR. 2016. Parainfluenza virus infection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 37:538–554. 10.1055/s-0036-1584798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vainionpää R, Hyypiä T. 1994. Biology of parainfluenza viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 7:265–275. 10.1128/CMR.7.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das K, Arnold E. 2015. Negative-strand RNA virus L proteins: one machine, many activities. Cell 162:239–241. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guryanov SG, Liljeroos L, Kasaragod P, Kajander T, Butcher SJ. 2015. Crystal structure of the measles virus nucleoprotein core in complex with an N-terminal region of phosphoprotein. J Virol 90:2849–2857. 10.1128/JVI.02865-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutsche I, Desfosses A, Effantin G, Ling WL, Haupt M, Ruigrok RW, Sachse C, Schoehn G. 2015. Near-atomic cryo-EM structure of the helical measles virus nucleocapsid. Science 348:704–707. 10.1126/science.aaa5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen MR, Communie G, Ribeiro EA, Jr, Martinez N, Desfosses A, Salmon L, Mollica L, Gabel F, Jamin M, Longhi S, Ruigrok RW, Blackledge M. 2011. Intrinsic disorder in measles virus nucleocapsids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:9839–9844. 10.1073/pnas.1103270108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rey FA, Communie G, Habchi J, Yabukarski F, Blocquel D, Schneider R, Tarbouriech N, Papageorgiou N, Ruigrok RWH, Jamin M, Jensen MR, Longhi S, Blackledge M. 2013. Atomic resolution description of the interaction between the nucleoprotein and phosphoprotein of Hendra virus. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003631. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox RM, Krumm SA, Thakkar VD, Sohn M, Plemper RK. 2017. The structurally disordered paramyxovirus nucleocapsid protein tail domain is a regulator of the mRNA transcription gradient. Sci Adv 3:e1602350. 10.1126/sciadv.1602350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alayyoubi M, Leser GP, Kors CA, Lamb RA. 2015. Structure of the paramyxovirus parainfluenza virus 5 nucleoprotein-RNA complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:E1792–E1799. 10.1073/pnas.1503941112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Omari K, Dhaliwal B, Ren J, Abrescia NG, Lockyer M, Powell KL, Hawkins AR, Stammers DK. 2011. Structures of respiratory syncytial virus nucleocapsid protein from two crystal forms: details of potential packing interactions in the native helical form. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 67:1179–1183. 10.1107/S1744309111029228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albertini AA, Wernimont AK, Muziol T, Ravelli RB, Clapier CR, Schoehn G, Weissenhorn W, Ruigrok RW. 2006. Crystal structure of the rabies virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex. Science 313:360–363. 10.1126/science.1125280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green TJ, Zhang X, Wertz GW, Luo M. 2006. Structure of the vesicular stomatitis virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex. Science 313:357–360. 10.1126/science.1126953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarbouriech N, Curran J, Ruigrok RW, Burmeister WP. 2000. Tetrameric coiled coil domain of Sendai virus phosphoprotein. Nat Struct Biol 7:777–781. 10.1038/79013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox R, Pickar A, Qiu S, Tsao J, Rodenburg C, Dokland T, Elson A, He B, Luo M. 2014. Structural studies on the authentic mumps virus nucleocapsid showing uncoiling by the phosphoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:15208–15213. 10.1073/pnas.1413268111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenni S, Bloyet LM, Diaz-Avalos R, Liang B, Whelan SPJ, Grigorieff N, Harrison SC. 2020. Structure of the vesicular stomatitis virus L protein in complex with its phosphoprotein cofactor. Cell Rep 30:53–60.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horwitz JA, Jenni S, Harrison SC, Whelan SPJ. 2020. Structure of a rabies virus polymerase complex from electron cryo-microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:2099–2107. 10.1073/pnas.1918809117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdella R, Aggarwal M, Okura T, Lamb RA, He Y. 2020. Structure of a paramyxovirus polymerase complex reveals a unique methyltransferase-CTD conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:4931–4941. 10.1073/pnas.1919837117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan J, Qian X, Lattmann S, El Sahili A, Yeo TH, Jia H, Cressey T, Ludeke B, Noton S, Kalocsay M, Fearns R, Lescar J. 2020. Structure of the human metapneumovirus polymerase phosphoprotein complex. Nature 577:275–279. 10.1038/s41586-019-1759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloyet LM, Schramm A, Lazert C, Raynal B, Hologne M, Walker O, Longhi S, Gerlier D. 2019. Regulation of measles virus gene expression by P protein coiled-coil properties. Sci Adv 5:eaaw3702. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingston RL, Hamel DJ, Gay LS, Dahlquist FW, Matthews BW. 2004. Structural basis for the attachment of a paramyxoviral polymerase to its template. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:8301–8306. 10.1073/pnas.0402690101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du Pont V, Jiang Y, Plemper RK. 2019. Bipartite interface of the measles virus phosphoprotein X domain with the large polymerase protein regulates viral polymerase dynamics. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007995. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolakofsky D. 2016. Paramyxovirus RNA synthesis, mRNA editing, and genome hexamer phase: a review. Virology 498:94–98. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curran J, Marq JB, Kolakofsky D. 1995. An N-terminal domain of the Sendai paramyxovirus P-protein acts as a chaperone for the NP protein during the nascent chain assembly step of genome replication. J Virol 69:849–855. 10.1128/JVI.69.2.849-855.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huber M, Cattaneo R, Spielhofer P, Orvell C, Norrby E, Messerli M, Perriard JC, Billeter MA. 1991. Measles virus phosphoprotein retains the nucleocapsid protein in the cytoplasm. Virology 185:299–308. 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanchard L, Tarbouriech N, Blackledge M, Timmins P, Burmeister WP, Ruigrok RW, Marion D. 2004. Structure and dynamics of the nucleocapsid-binding domain of the Sendai virus phosphoprotein in solution. Virology 319:201–211. 10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De BP, Hoffman MA, Choudhary S, Huntley CC, Banerjee AK. 2000. Role of NH2- and COOH-terminal domains of the P protein of human parainfluenza virus type 3 in transcription and replication. J Virol 74:5886–5895. 10.1128/jvi.74.13.5886-5895.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang S, Cheng Q, Luo C, Yin L, Qin Y, Chen M. 2018. An alanine residue in human parainfluenza virus type 3 phosphoprotein is critical for restricting excessive N0-P interaction and maintaining N solubility. Virology 518:64–76. 10.1016/j.virol.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desfosses A, Milles S, Jensen MR, Guseva S, Colletier JP, Maurin D, Schoehn G, Gutsche I, Ruigrok RWH, Blackledge M. 2019. Assembly and cryo-EM structures of RNA-specific measles virus nucleocapsids provide mechanistic insight into paramyxoviral replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:4256–4264. 10.1073/pnas.1816417116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. 1995. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng 8:127–134. 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang N, Shan H, Liu M, Li T, Luo R, Yang L, Qi L, Chu X, Su X, Wang R, Liu Y, Sun W, Shen QT. 2021. Structure and assembly of double-headed Sendai virus nucleocapsids. Commun Biol 4:494. 10.1038/s42003-021-02027-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leyrat C, Yabukarski F, Tarbouriech N, Ribeiro EA, Jr, Jensen MR, Blackledge M, Ruigrok RW, Jamin M. 2011. Structure of the vesicular stomatitis virus N0-P complex. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002248. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landeras-Bueno S, Oda SI, Norris MJ, Li Salie Z, Guenaga J, Wyatt RT, Saphire EO. 2019. Sudan ebolavirus VP35-NP crystal structure reveals a potential target for pan-filovirus treatment. mBio 10:e00734-19. 10.1128/mBio.00734-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugita Y, Matsunami H, Kawaoka Y, Noda T, Wolf M. 2018. Cryo-EM structure of the Ebola virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature 563:137–140. 10.1038/s41586-018-0630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renner M, Bertinelli M, Leyrat C, Paesen GC, Saraiva de Oliveira LF, Huiskonen JT, Grimes JM. 2016. Nucleocapsid assembly in pneumoviruses is regulated by conformational switching of the N protein. Elife 5:e12627. 10.7554/eLife.12627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holm L, Rosenström P. 2010. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W545–W549. 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milles S, Jensen MR, Communie G, Maurin D, Schoehn G, Ruigrok RW, Blackledge M. 2016. Self-assembly of measles virus nucleocapsid-like particles: kinetics and RNA sequence dependence. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 55:9356–9360. 10.1002/anie.201602619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yabukarski F, Lawrence P, Tarbouriech N, Bourhis JM, Delaforge E, Jensen MR, Ruigrok RW, Blackledge M, Volchkov V, Jamin M. 2014. Structure of Nipah virus unassembled nucleoprotein in complex with its viral chaperone. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21:754–759. 10.1038/nsmb.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kao RY, Yang D, Lau LS, Tsui WH, Hu L, Dai J, Chan MP, Chan CM, Wang P, Zheng BJ, Sun J, Huang JD, Madar J, Chen G, Chen H, Guan Y, Yuen KY. 2010. Identification of influenza A nucleoprotein as an antiviral target. Nat Biotechnol 28:600–605. 10.1038/nbt.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerritz SW, Cianci C, Kim S, Pearce BC, Deminie C, Discotto L, McAuliffe B, Minassian BF, Shi S, Zhu S, Zhai W, Pendri A, Li G, Poss MA, Edavettal S, McDonnell PA, Lewis HA, Maskos K, Mörtl M, Kiefersauer R, Steinbacher S, Baldwin ET, Metzler W, Bryson J, Healy MD, Philip T, Zoeckler M, Schartman R, Sinz M, Leyva-Grado VH, Hoffmann HH, Langley DR, Meanwell NA, Krystal M. 2011. Inhibition of influenza virus replication via small molecules that induce the formation of higher-order nucleoprotein oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:15366–15371. 10.1073/pnas.1107906108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leung DW, Borek D, Luthra P, Binning JM, Anantpadma M, Liu G, Harvey IB, Su Z, Endlich-Frazier A, Pan J, Shabman RS, Chiu W, Davey RA, Otwinowski Z, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2015. An intrinsically disordered peptide from Ebola virus VP35 controls viral RNA synthesis by modulating nucleoprotein-RNA interactions. Cell Rep 11:376–389. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galloux M, Gsponer N, Gaillard V, Fenner B, Larcher T, Vilotte M, Riviere J, Richard CA, Eleouet JF, Le Goffic R, Mettier J, Nyanguile O. 2020. Targeting the respiratory syncytial virus N0-P complex with constrained alpha-helical peptides in cells and mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e00717-20. 10.1128/AAC.00717-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hara K, Yaita K, Khamrin P, Kumthip K, Kashiwagi T, Eleouet JF, Rameix-Welti MA, Watanabe H. 2020. A small fragmented P protein of respiratory syncytial virus inhibits virus infection by targeting P protein. J Gen Virol 101:21–32. 10.1099/jgv.0.001350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Easton V, Mcphillie M, Garcia-Dorival I, Barr JN, Edwards TA, Foster R, Fishwick C, Harris M. 2018. Identification of a small molecule inhibitor of Ebola virus genome replication and transcription using in silico screening. Antiviral Res 156:46–54. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ouizougun-Oubari M, Pereira N, Tarus B, Galloux M, Lassoued S, Fix J, Tortorici MA, Hoos S, Baron B, England P, Desmaele D, Couvreur P, Bontems F, Rey FA, Eleouet JF, Sizun C, Slama-Schwok A, Duquerroy S. 2015. A druggable pocket at the nucleocapsid/phosphoprotein interaction site of human respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol 89:11129–11143. 10.1128/JVI.01612-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Natsoulis G, Boeke JD. 1991. New antiviral strategy using capsid-nuclease fusion proteins. Nature 352:632–635. 10.1038/352632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X, Jia R, Pan Y, Wang M, Chen S, Zhu D, Liu M, Zhao X, Yang Q, Wu Y, Zhang S, Liu Y, Zhang L, Yin Z, Jing B, Huang J, Tian B, Pan L, Yu Y, Ur Rehman M, Cheng A. 2019. Therapeutic effects of duck Tembusu virus capsid protein fused with staphylococcal nuclease protein to target Tembusu infection in vitro. Vet Microbiol 235:295–300. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao Y, Zhang Q, Lang Y, Liu Y, Dong X, Chen Z, Tian W, Tang J, Wu W, Tong Y, Chen Z. 2017. Human apo-SRP72 and SRP68/72 complex structures reveal the molecular basis of protein translocation. J Mol Cell Biol 9:220–230. 10.1093/jmcb/mjx010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. 2011. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:235–242. 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long F, Vagin AA, Young P, Murshudov GN. 2008. BALBES: a molecular-replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 64:125–132. 10.1107/S0907444907050172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:486–501. 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. 2011. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:355–367. 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liebschner D, Afonine PV, Baker ML, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Croll TI, Hintze B, Hung LW, Jain S, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner RD, Poon BK, Prisant MG, Read RJ, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, Sammito MD, Sobolev OV, Stockwell DH, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev AG, Videau LL, Williams CJ, Adams PD. 2019. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 75:861–877. 10.1107/S2059798319011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexander N, Woetzel N, Meiler J. 2011. bcl::Cluster: a method for clustering biological molecules coupled with visualization in the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. IEEE Int Conf Comput Adv Bio Med Sci 2011:13–18. 10.1109/ICCABS.2011.5729867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu Y, Chen Z, Fu Y, He Q, Jiang L, Zheng J, Gao Y, Mei P, Chen Z, Ren X. 2015. The amino-terminal structure of human fragile X mental retardation protein obtained using precipitant-immobilized imprinted polymers. Nat Commun 6:6634. 10.1038/ncomms7634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nielsen SS, Toft KN, Snakenborg D, Jeppesen MG, Jacobsen JK, Vestergaard B, Kutter JP, Arleth L. 2009. BioXTAS RAW, a software program for high-throughput automated small-angle X-ray scattering data reduction and preliminary analysis. J Appl Crystallogr 42:959–964. 10.1107/S0021889809023863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Petoukhov MV, Franke D, Shkumatov AV, Tria G, Kikhney AG, Gajda M, Gorba C, Mertens HD, Konarev PV, Svergun DI. 2012. New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Crystallogr 45:342–350. 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Svergun DI. 1999. Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys J 76:2879–2886. 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77443-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Volkov VV, Svergun DI. 2003. Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J Appl Crystallogr 36:860–864. 10.1107/S0021889803000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. 1995. CRYSOL: a program to evaluate X-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J Appl Crystallogr 28:768–773. 10.1107/S0021889895007047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kozin MB, Svergun DI. 2001. Automated matching of high- and low-resolution structural models. J Appl Crystallogr 34:33–41. 10.1107/S0021889800014126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Final refined coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession code 7EV8.