Abstract

Background

Testicular embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS) is a rare soft tissue tumor in children featured with high intra-tumoral heterogeneity. In this study, we aimed to comprehensively delineate the testicular ERMS intra-tumoral heterogeneity and tumor microenvironment.

Methods

Cell types and the corresponding marker genes were identified by single-nuclear RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). Functional states of different clusters were evaluated by uniform manifold approximation and projection and differentially expressed genes. Kaplan–Meier curve analysis was constructed according to the gene expression profile to determine the correlation between candidate marker genes and the overall survival and disease-free survival of patients with osteosarcoma from TCGA.

Results

A total of 8868 tumor cells and 10,147 normal cells were obtained from testicular ERMS tissues. The heterogeneous malignant subtype was composed of six subgroups (C1–C6) with differential proliferative and migratory potentials. Cell trajectory analysis revealed the C1 subgroup might be the starting cells of the tumor and transform into two different types of malignant cells, C2 and C5/6, during the development of RMS. The differentially expressed genes were closely related to cell adhesion and extracellular matrix signaling pathways. Furthermore, the interaction analysis between cell subgroups (macrophages and tumor cells, endothelial cells and tumor cells) demonstrated that collagen-related gene COL6A1 plays a key role from the initiation of ERMS to the entire process of malignant transformation.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a new insight in the understanding of the initiation and progression of testicular ERMS and have potential value in the development of markers for the diagnosis and stratification of testicular ERMS.

Keywords: embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma, intra-tumoral heterogeneity, biomarker, extracellular matrix, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Soft tissue tumors account for approximately 3% of childhood tumors and 1% of adult tumors.1 Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) mostly occurs in the head, neck, limbs, and trunk.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) divided RMS into embryonic RMS (ERMS) (including spindle cell RMS, grape cluster-like RMS and anaplastic RMS), and alveolar RMS (including solid and anaplastic and pleomorphic RMS). ERMS arising from the testis is extremely rare. Testicular ERMS is more common in adolescents and children < 20 years.3 The standard treatment for testicular ERMS is orchiectomy, combined with chemotherapy. Commonly used chemotherapy drugs are vincristine, actinomycin D and cyclophosphamide, which are important to prevent recurrence. Patients with ERMS with tumor diameter > 5 cm or aged > 10 years have a poor prognosis, and the 5-year survival rate is 30%. Primary testicular ERMS is generally considered to have a poor prognosis.4 Testicular ERMS has high heterogeneity and dynamic immunogenic characteristics, and it is difficult to find effective therapeutic targets.5

Traditional transcriptomics research is based on mixed cell populations and lacks sufficient resolution when determining specific cell types to elucidate the complexity of intratumoral heterogeneity in RMS. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has great value in revealing the intratumoral heterogeneity of multiple cancers and cell crosstalk with the tumor microenvironment (TME).6,7 We believe that a global single-cell portrait of how different cell types work together would help identify new pathways in testicular ERMS and eventually new therapeutics. In this study, we conducted snRNA-seq analysis in a testicular ERMS sample, and identified six major cell clusters. We also characterized the cellular characteristics of malignant cells and major TME cells. We further identified a cluster gene that affects known cancer pathways. Our study reveals a transcriptional landscape of the intratumoral heterogeneity in testicular ERMS and may have potential value in providing novel prognostic markers for testicular ERMS.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

This study included a patient (male, 16 years old) with ERMS, which was confirmed by immunohistochemical results (Ki-67 +++, Myogenin was partially positive, Myoglobin was individually positive, MyoD1 was weakly positive, Des was partially positive, CD56 was positive, SMA was negative, CK was negative, EMA was negative, S-100 was negative, and CD34 was negative). The tumor was located on the left testis with 6.5 cm diameter. Before surgery, the patient had not received any chemotherapy. The adjacent tissues (more than 2 cm from tumor margin) were used as normal control. The fresh tissues were stored at liquid nitrogen. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample Preparation of snRNA-Seq

The tissues were cut into 2 mm3 pieces, and transferred into 3mL of pre-cooled homogenization buffer, and incubated for 5 minutes. The tissues were homogenized into a pre-cooled 15 mL centrifuge tube. The tubes were centrifuged at 500g for 5 minutes at 4°C to collect the pellets. The pellets were resuspended with 1 mL blocking buffer and filtered with a 30 μm cell sieve. The cells were stained with trypan blue to estimate the cell viability. DAPI staining was used for cell count.

Library Preparation of snRNA-Seq

The library and snRNA-seq are completed by the Beijing Genomics Institute. Briefly, the single cell suspension concentration of the sample was adjusted to 1000 cells/μL. The suspension, magnetic beads, and oil droplets were added to the DNBelab C4 portable single cell device to form emulsion droplets under negative pressure. After demulsification, the mRNA captured by the magnetic beads was transcribed into cDNA, and the cDNA was further enriched and purified by PCR, and used for the library construction.

Primary Analysis of Raw Read Data

Raw reads were processed to generate gene expression profiles using CellRanger. Briefly, the adapter removal is processed according to the position of the adapter in the library; the reads after adapter removal are processed by CellRanger; CellRanger was able to statistics the quality of the reads. For example, when the Q30 value of Read1 or Read2 were less than 70%, a corresponding warning will be given; after the filtering is generated, the reads will map the reference genome after the conditions are met. CellRanger will filter the reads according to MappingQ. After filtering read one without poly T tails, valid cell barcode and UMI was extracted. Adapters and poly A tails were trimmed (fastp V1) before aligning read two to GRCh38 with ensemble version 92 gene annotation (fastp 2.5.3a and featureCounts 1.6.2).8 Reads with the same cell barcode, UMI and gene were grouped together to calculate the number of UMIs per gene per cell. The UMI count tables of each cellular barcode were used for further analysis. Cell type identification and clustering analysis using Seurat program.9 The Seurat program (http://satijalab.org/seurat/, R package, v.3.1.2) was applied for analysis of RNA-Sequencing data. UMI count tables were loaded into R using read.table function. Mt-genes cutoff was set to 50. Any cells with UMI and genes number larger than 98% of the maximum UMI and genes number were not be used for further analysis. After dimension reduction by RunPCA, resolution 2 was used to do the clustering.

Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Analysis

Differential gene expression (DEG) testing was performed using the FindMarkers function in Seurat with Wilcoxon test and p values were adjusted using Bonferroni correction. DEGs were filtered using a minimum log(fold change) of 0.25 and a maximum adjusted p value of 0.05 and were then ranked by average log(fold change) and FDR. Enrichment analysis for the functions of the DEGs was conducted using the clusterProfiler (v3.12.0) package. The gene sets were based on Gene Ontology terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways and analyzed by enrichKEGG and enrichGO. ggplot2 (Version:3.3.5) was used to draw the following result pictures.

Cell Type Annotation

In order to determine cell types, we combined unsupervised clustering and differential expression to compare top differentially expressed genes with cell type specific expression. We confidently identified broad categories among all cells, and further delineated cellular subtypes by isolating subsets (through in silico “gating”) of broadly defined cell types and re-analyzing with the same approach. For broad cell type annotation shown in Figure 1C, low-resolution clustering was performed using the FindClusters function with resolution 2 with the first 20 PCs to generate 33 clusters. Differential expression was performed using the FindAllMarkers function in Seurat with default parameters. To assign one of the 11 major cell types to each cluster, we scored each cluster by the normalized expressions of the following canonical markers: Spermatogonial (CPEB1, KIT, DMRT1), Spermatocytes (SYCP1, SMC1B), Spermatids (SPACA3, PRM1, CCNA1, SPAG6), Sperms (TNP1, PRM2), Sertoli cells (WT1, SOX9, CLDN11), Fibroblasts (DCN, LUM, COL1A1), Leydig cells (INSL3, STAR, CYP11A1), Myoid cells (ACTA2, PTCH1, MYH11), Endothelial cells (PECAM1, ENG, VWF, LYVE1), Macrophages (CD163, MRC1, CD14, GPNMB, MSR1), Cancer cells (COL5A2, COL6A1, COL6A2, EGFR, MYOG, DES). The results were manually examined to ensure the correctness of the results and visualized by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). The 11 major cell types were chosen by initial exploratory inspection of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of each cluster combined with literature study. The DEGs were generated by Seurat FindMarkers function. Cancer cells, Endothelial cells, and Macrophage’s subtype were determined using the ScaleData function in Seurat, and re-clustering at resolution (1.6) to obtain 6, 3 and 3 clusters respectively.

Figure 1.

Cell types in testicular ERMS identified by single cell transcriptomic analysis. (A) Workflow processing of specimens of testicular ERMS tumors for scRNA-seq. (B) Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes in genomic regions. (C) The uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot demonstrates main cell types in testicular ERMS. (D) The percentage of assigned cell types are summarized in normal and tumor tissues. (E) UMAP plot shows expression of specific markers in each cell type.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis

The potential functions of DEGs were analyzed by “clusterProfiler” R package 3.16.1. Pathways with p_adj value < 0.05 were considered as significantly enriched. DIAMOND software was used to compare ORF to Animal Transcription Factor Database (AnimalTFDB) to identify the coding ability of transcription factor. The GENIE3 package predicted a regulatory network based on the co-expression of regulators and targets. RcisTarget package searched for transcription factor binding motifs in the given data. Genes involved in the predicted regulatory network were defined as a gene set, and AUCell package calculated the auc value of the gene set to assess the activity of regulatory network in cells. For GSVA pathway enrichment analysis, the average gene expression of each cell type was used as input data using the GSVA package. The Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene sets were used as reference.10

Trajectory Analysis

To map differentiation/conversion of cell subtypes, pseudotime trajectory analysis was performed with Monocle2 software package (v2.8.0) in R95.11 Seurat v3.1.2 FindVairableFeatures was used in trajectory analysis for analyzing genes average expression, and DDRTree was used for dimension-reduction. The trajectory was visualized by plot_cell_trajectory. A branch expression analysis model (BEAM) analysis was used for generate cells branches into several groups with q values < 10−10. The plot_genes_branched_heatmap function was used for visualization.

Cell-Cell Interaction Score Calculation Using Cellphone DB

CellPhoneDB (Version 2.1.0) is a publicly available repository of curated receptors, ligands and their interactions and used to identify cellular communication across different cell types. After extracted the counts matrix and cell annotation, “cellphonedb method statistical_analysis” finished the whole analysis. After that, “cellphonedb plot dot_plot”, “cellphonedb plot heatmap_plot” and several commands were used to calculate and draw the results. R packages: psych (Version 2.0.12), qgraph (Version 1.6.9), igraph (Version 1.2.6), purrr (Version 0.3.4) were used to draw count network.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the difference, and differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

SnRNA-Seq Analysis and Cell Typing of Testicular ERMS

The tumor tissue and adjacent tissues of the patient were collected for snRNA-seq (Figure 1A). There were 8868 tumor cells and 10,147 normal cells for further analysis (Figure 1B). The unbiased clustering of cell composition was explored by PCA and visualized by UMAP (Figure 1C). According to the known specific marker genes, 11 main cell clusters were defined: macrophages, leydig cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, myoid cells, spermatocytes, sperms, spermatids, sertoli cells, spermatogonial cells, cancer cells (Figure 1C and D). The gene expression patterns in different cell clusters in testicular ERMS tissue were presented (Figure 1E). In addition, we also showed the expression pattern of each known cell marker gene through VlnPlot (Figure S1A), and differential gene expression analysis, thereby generating cluster-specific marker genes (Figure S1B–C).

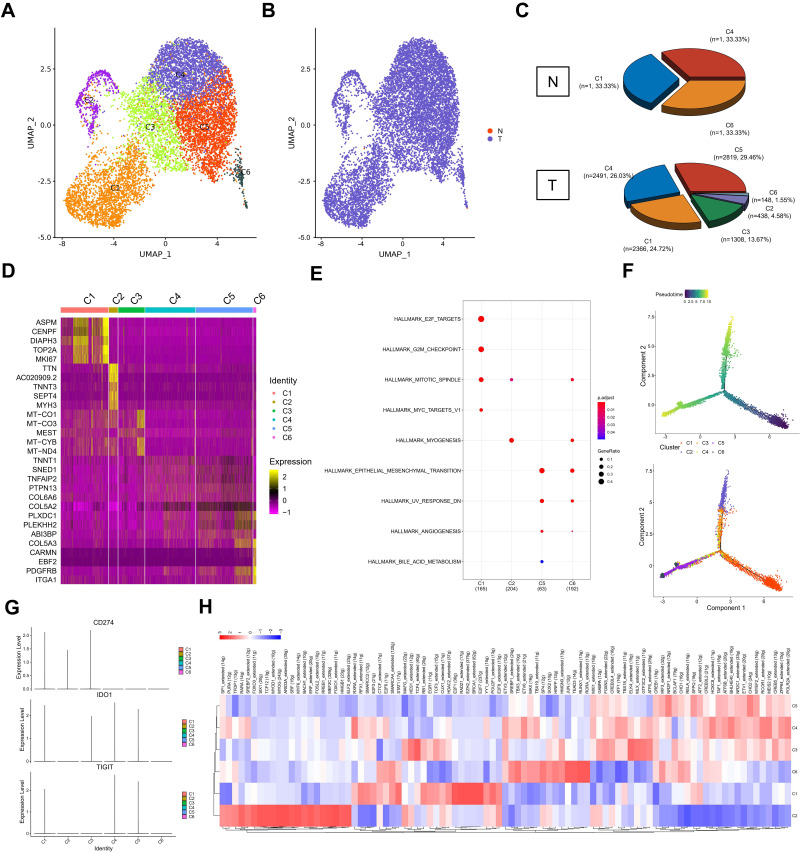

Trajectory Analysis of Different Subgroups from Testicular ERMS

According to UMAP analysis, the cells were divided into 6 subgroups (C1-C6, Figure 2A and B). In tumor tissues, C1 accounted for 24.72% (n=2366), C2 accounted for 4.58% (n=438), C3 accounted for 13.67% (n=1308), C4 accounted for 26.03% (n=2491), C5 accounted for 29.46% (n=2819), C6 accounted for 1.55% (n=148) (Figure 2C). Each subgroup has a set of specific marker genes to distinguish each subgroup (Figure 2D). We conducted a functional enrichment analysis for each subgroup. C1 subgroup was related to E2F targets, G2M checkpoints, mitotic spindles, and myc targets; C2 subgroup was mainly related to mitotic Spindle and myogenesis. C5 subgroup was mainly related to EMT, UV response and angiogenesis, and C6 subgroup was mainly related to mitotic spindle, myogenesis, EMT, and UV response (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Distinct clusters of malignant cells in testicular ERMS. (A and B) Six main malignant cell subclusters were identified by UMAP analysis. (C) The percentage of assigned cell types are summarized in normal and tumor tissues. (D) Heatmap of specific markers in each cell type. (E) The pathway enrichment of GSEA of the 9 hallmark gene sets in MSigDB database among the six subclusters. (F) Pseudotime was colored in a gradient from dark to light blue. The start of pseudotime is indicated by dark blue, the end of pseudotime by light blue (upper). Pseudotime trajectory of 6 subclusters was generated by Monocle2 (lower). (G) The key genes expression of immune checkpoint in 6 subclusters. (H) SCENIC analysis of 6 subclusters.

In order to study the origin of tumor cells in the occurrence of testicular ERMS, trajectory analysis was carried out on the cells of 6 subgroups. The C1 subgroup cells appeared at the beginning of the trajectory, and the C2 and C5/6 subgroups cells appeared at the end of the trajectory (Figure 2F), indicating that the C1 subgroup may be the initiating cells of tumors, and transformed into C2 and C5/6 malignant cells, during the development of testicular ERMS. Analysis of the expression of immune checkpoint-related genes found that CD274 (PD-L1) were highly expressed in C1, C2, and C3, IDO1 was highly expressed in C1, C3, C4, and C5, and TIGIT was highly expressed in C1, C4, and C5 (Figure 2G).

SCENIC analysis was used to determined which transcription factors were involved in the occurrence and development of testicular ERMS (Figure 2H). C1 cells highly expressed E2F1, RAD21, EZH2, BRCA1, E2F7, and C2 cells highly expressed RARA, FOXO3, ARID3A, HMGB1, and SRF. C5 subgroup highly expressed CREB, CHD2, IRF3. C6 subgroup cells highly expressed JUN, TEAD3, RUNX1 and RORA (Figure 2H). The downstream genes regulated by these transcription factors were displayed (Figure S2), which implies that these genes have potential role in the development of testicular ERMS.

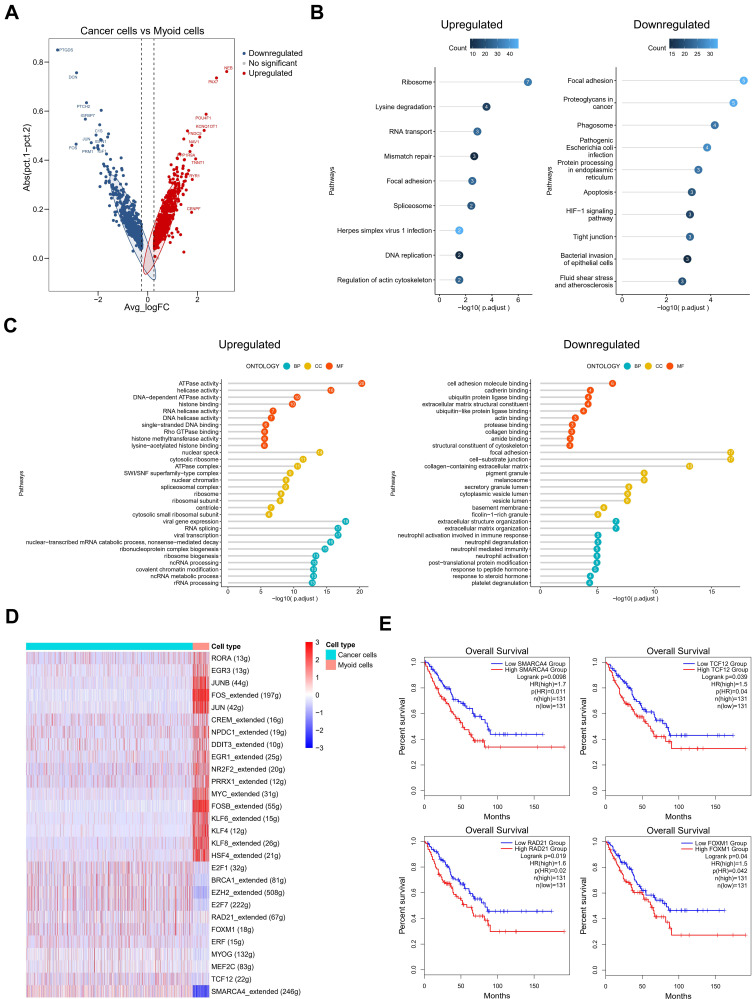

Cell Adhesion and Extracellular Matrix Organization are Activated During the Malignant Transformation of Myoid Cells in Testicular ERMS

It is generally believed that myoid cells are the starting cells of RMS. We further analyzed the changes in the gene expression profile of myoid cells. Compared with tumor cells, myoid cells highly expressed NEB, PAX7, and TNNT1, and lowly expressed PTGDS, DCN, IGFBP7, and JUN (Figure 3A). KEGG analysis revealed that the up-regulated genes were associated with Ribosome, RNA transport, mismatch repair and focal adhesion, while the down-regulated genes were associated with Focal adhesion, Proteoglycans in cancer and Phagosome (Figure 3B). GO term analysis showed that the up-regulated genes were associated with ATPase activity, ATPase complex, and RNA splicing, while the down-regulated genes were associated with cell adhesion molecule binding, focal adhesion, and extracellular matrix organization (Figure 3C), suggesting that cell adhesion and extracellular matrix organization are important signaling pathway for the malignant transformation of myoid cells.

Figure 3.

The role of the myoid cells in testicular ERMS. (A) The DEGs in cancer cells and myoid cells were identified using edgeR package. Red spots indicate upregulated genes; blue spots indicate downregulated genes; grey spots indicate no significant change in genes. (B) The pathway terms enrichment for DEGs in cancer cells and myoid cells. (C) The enriched biological processes for DEGs in cancer cells and myoid cells. (D) SCENIC analysis of cancer cells and myoid cells. (E) Kaplan-Meier plot predicting overall survival rate of sarcoma patients based on the expression changes of 4 downregulated transcription factors in myoid cells.

In order to further determine the predictive role of specific differential genes in the survival and prognosis of testicular ERMS, we showed the differentially expressed genes in myoid cells through heatmap (Figure S3A). SCENIC analyzed the differentially expressed transcription regulons (Figure 3D) and found that SMARCA4, TCF12, RAD21, and FOXM1 were significantly down-regulated in myoid cells (Figure S3B). Analysis of soft tissue sarcoma data from TCGA found that the overall survival of patients with high expression of SMARCA4, TCF12, RAD21, and FOXM1 was significantly reduced (Figure 3E), suggesting that these transcription factors play an important role in the malignant transformation of myoid cells.

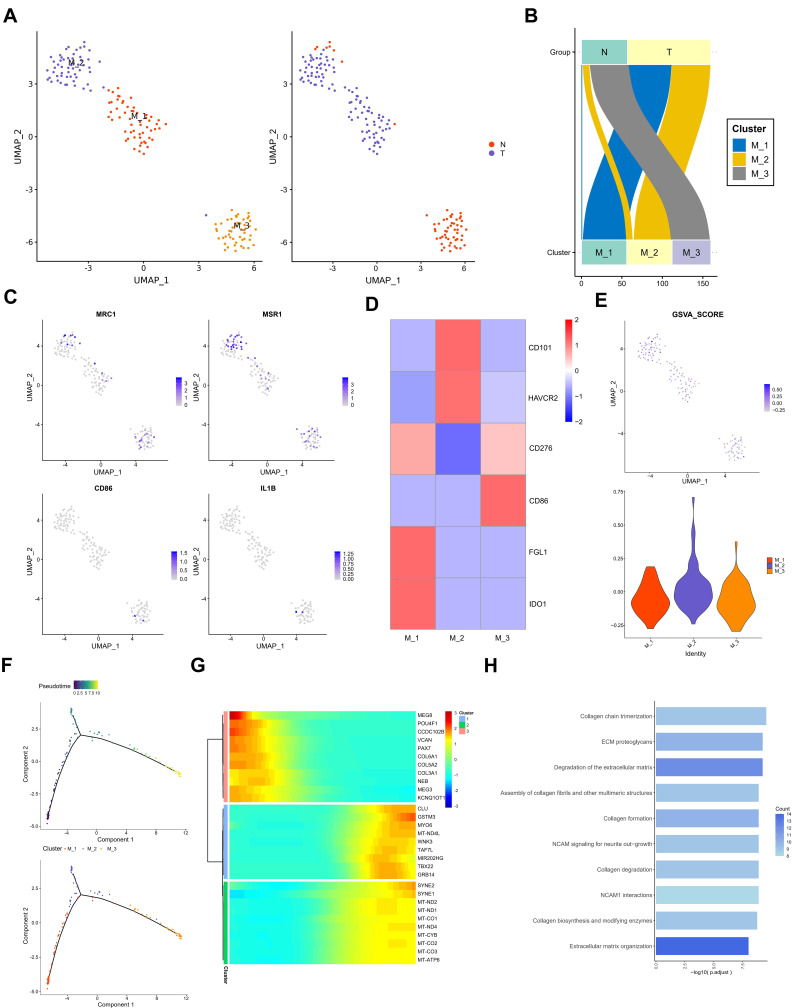

Collagen Pathway and Extracellular Matrix Pathway are Activated in Macrophages

In order to further analyze the role of different subtypes of macrophages in testicular ERMS, macrophages were divided into 3 subgroups (M1, M2, and M3) by UMAP. Among them, tumor cells mainly included M1, M2 subgroups, and the adjacent normal tissues contained M3 subgroup (Figure 4A and B). Analysis of macrophage surface receptors revealed that MRC1 is mainly expressed in M2 and M3, MSR1 was expressed in M1, M2, and M3, and CD86 and IL1B were expressed in M3 (Figure 4C). The expression of immune checkpoint-related molecules in the subgroups were showed in the heatmap. FGL1 and IDO1 were highly expressed in the M1 subgroup, CD101 and HAVCR2 were highly expressed in the M2 subgroup, and CD86 was highly expressed in the M3 subgroup (Figure 4D). The GSVA analysis was performed to estimate the activity of immune checkpoint-related molecules. M2 subgroup has a higher GSVA score, suggesting that the M2 subgroup has a higher immune activity (Figure 4E). The trajectory analysis showed that M1 subgroup located at the beginning of the trajectory, and M2 and M3 subgroups appear at the end of the trajectory (Figure 4F). These findings indicate that the M1 subgroup of cells may be the starting cells and may transform into the two types of malignant cells, ultimately promoting the development of testicular ERMS.

Figure 4.

The role of macrophages in testicular ERMS. (A) UMAP plot demonstrates the 3 subgroups of macrophages in testicular ERMS. (B) The percentage of assigned cell types are summarized in normal and tumor tissues. (C) UMAP plot shows expression of macrophages markers in each subgroup. (D) Heatmap showing the key genes expression of immune checkpoint in 3 subgroups. (E) GSVA analysis for immune checkpoint molecules in 3 subgroups of macrophages. (F) Pseudotime was colored in a gradient from dark to light blue. The start of pseudotime is indicated by dark blue, the end of pseudotime by light blue (upper). Pseudotime trajectory of 3 subgroups of macrophages was generated by Monocle2 (lower). (G) Top 10 DEGs with expression levels that changed the most over the pseudotime trajectory are shown. Color key from blue to red indicates low to high. (H) The pathway terms enrichment for top 10 DEGs in 3 subgroups of macrophages.

We studied the transcription regulon and signaling pathway patterns in the progression trajectory of macrophages (Figure S4A and B). We clustered the top 100 genes using pseudotime trajectory analysis into 3 patterns (Figure 4F). Among them, the expression of collagen-related genes COL6A1, COL3A1 and COL5A2 in cluster 3 were high at the initial stage and low at the end stage. The MYO6, TAF7L, and GRB14 of cluster 1 were mainly enriched at the end of progression. The genes, including SYNE2 and mitochondria-related genes, in cluster 2 lowly expressed at the beginning and highly expressed at the end (Figure 4G). Functional enrichment analysis showed that macrophages in testicular ERMS were closely related to collagen pathway and extracellular matrix pathway (Figure 4H), suggesting that these two pathways are key pathways for macrophages to promote the progression of testicular ERMS.

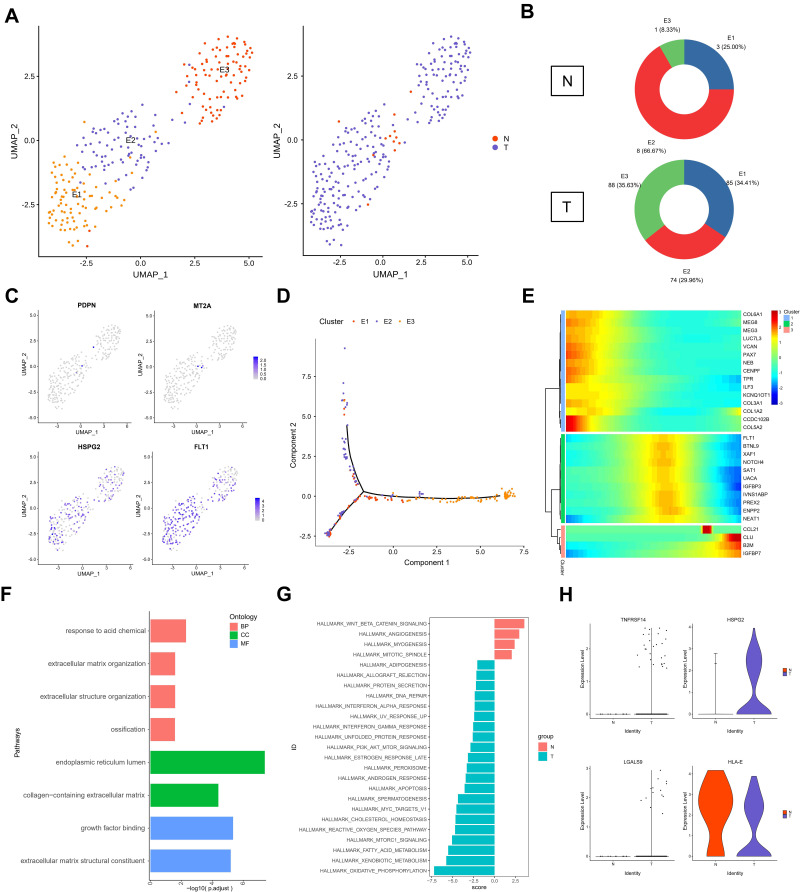

The Role of Endothelial Cell Subtypes in Testicular ERMS

Endothelial cells have a critical role in the metastasis of ERMS. In order to analyze the role of subgroups of endothelial cells in the progression of testicular ERMS, endothelial cells were divided into 3 subgroups (E1, E2, and E3) by UMAP (Figure 5A). Normal tissues mainly expressed E2 subgroup cells (66.7%), and all three types of endothelial cells were expressed in tumor tissues (E1, 34.41%; E2, 29.96%; E3, 35.63%) (Figure 5B). Analysis of endothelial cell markers found that the vascular endothelial cell marker FLT1 and tumor endothelial cell marker HSPG2 were expressed in three types of cells, and the lymphatic endothelial cell marker PDPN and the normal endothelial cell marker MT2A expression were weaker in E2 cells (Figure 5C). Trajectory analysis found that the E1 and E2 subgroup cells appeared at the beginning, and the E3 subgroup cells appeared at the end (Figure 5D). These findings indicate that the E1 and E2 subgroups of cells transform into E3 cells during the progression of ERMS to promote tumor progression. We further clustered the top 100 differential genes using pseudotime trajectory analysis, and clustered these genes into 3 expression patterns (Figure 5E). The highly expressed genes in cluster 1 at the initial stage of ERMS included the collagen-related genes COL6A1, COL5A2, COL3A1, and COL1A2. The highly expressed genes in cluster 2 at the middle stage of ERMS included IGFBP3, NOTCH4, and NEAT1 in cluster 2. The genes in cluster 3, including CCL21, CLU, B2M and IGFBP7, showed low expression levels at the beginning and high expression levels at the end (Figure 5E). Functional enrichment analysis showed that the main pathways that endothelial cells participate in the progression of testicular ERMS include extracellular matrix organization, collagen-containing extracellular matrix, and extracellular matrix structural constituent pathways (Figure 5F), and were closely associated with PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling and Oxidative Phosphorylation pathways (Figure 5G). In addition, the immune activating factor TNFRSF14 and the pro-angiogenic factor LGALS9 were highly expressed in tumor endothelial cell (Figure 5H).

Figure 5.

The role of endothelial cells in testicular ERMS. (A) UMAP plot demonstrates the 3 subgroups of endothelial cells in testicular ERMS. (B) The percentage of assigned cell types are summarized in normal and tumor tissues. (C) UMAP plot shows expression of endothelial cells markers in each subgroup. (D) Pseudotime trajectory of 3 subgroups of endothelial cells was generated by Monocle2. Heatmap showing the key genes expression of immune checkpoint in 3 subgroups. (E) pseudotime trajectory analysis were divided endothelial cells into 3 clusters based on the DEGs expression trend. Color key from blue to red indicates low to high. (F) The enriched biological processes for DEGs in 3 subgroups of endothelial cells. (G) GSVA analysis in 3 subgroups of endothelial cells. (H) The key genes expression of immune activation in 3 subgroups of endothelial cells.

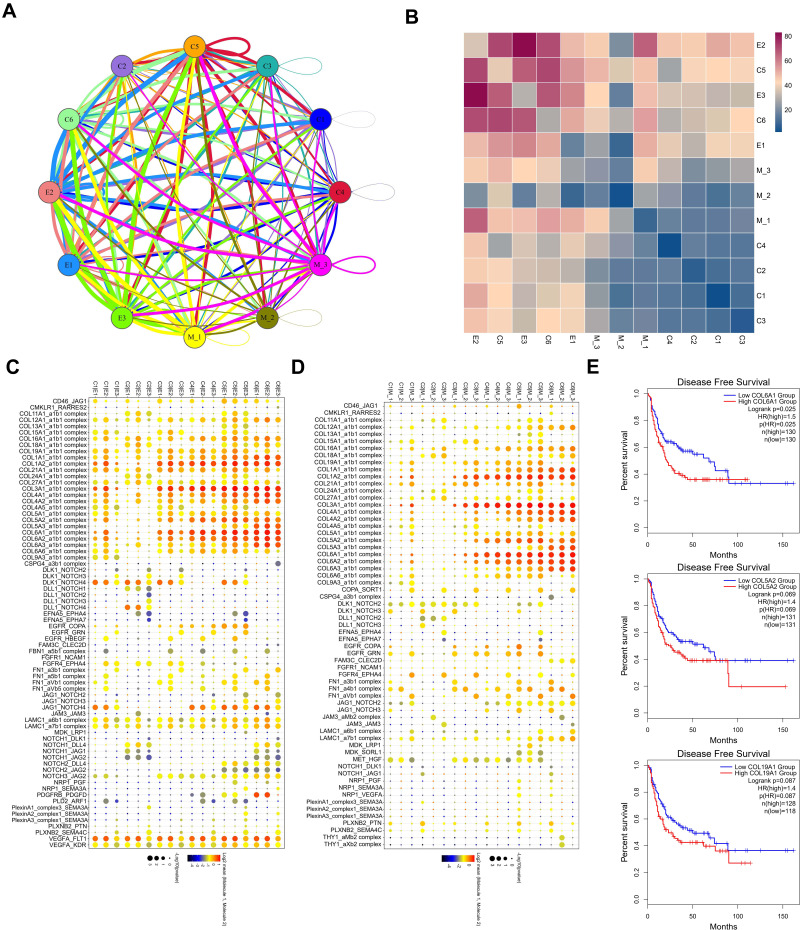

Interactions Between Subgroups

The above results analyze the role of each subpopulation of cells in the progression of testicular ERMS. However, the interaction between them is unclear. We further analyzed the interaction between the subpopulations of cells and the role of these relationships in the progression of testicular ERMS. We showed the interactions between cells in each subpopulation (Figure 6A), among which the interactions between E2 and E3, C5, and C6 were stronger (Figure 6B). Functional enrichment analysis revealed that Collagen pathway-related genes exhibited high levels of expression in cell interactions of various subgroups, especially COL6A1 in C1/E2, C3/E1, C3/E2, C3/E3, C4/E1/ E2/E3, C5/E1/E2/E3, C6/E1/E2/E3 and C3/M1/M2/M3, C4/M1/M2/M3, C5/M1/M2/M3, C6/M1/M2/ M3 showed high expression during the interaction process (Figure 6C and D), suggesting that COL6A1 plays a key role in the whole process from the initiation of testicular ERMS to the malignant transformation. Analysis of soft tissue sarcoma data from TCGA found that the overall survival of patients with high COL6A1 expression was significantly lower than that of patients with low COL6A1 expression (Figure 6E), confirming that COL6A1 is a marker of poor prognosis and may promote the progression of testicular ERMS.

Figure 6.

The interaction between subgroups. (A) the interactions between each subpopulation were showed. (B) The interactions score between each subpopulation were showed. (C and D) The core genes in the interactions between each subpopulation. (E) Kaplan-Meier plot predicting disease-free survival rate of sarcoma patients based on the expression changes of COL6A1.

Discussion

For accurate stratification and early detection of RMS, more specific and sensitive markers are needed.12,13 However, since highly heterogeneous, genes changes in certain cell populations in RMS would be hidden by the traditional normalized data processing method of RNA-seq. SnRNA-seq is a promising tool to study the heterogeneity of RMS.14 To the best of our knowledge, the study on the heterogeneity of testicular ERMS by snRNA-seq has not been reported. In this study, we performed snRNA-seq using testicular ERMS tissues and identified six clusters (C1-C6). According to the analysis of the trajectory analysis, the C1 subgroup may be the starting cells of the tumor and transform into two different types of malignant cells, C2, and C5/6 during the development of RMS.

Genes related to the initiation and progression of ERMS were detected in the C1 subgroup, which highly expressed genes closely related to cell proliferation and cell cycle, including assembly factor for spindle microtubules (ASPM), centromere protein F (CENPF), diaphanous-related formin 3 (DIAPH3), DNA topoisomerase II alpha (TOP2A), and marker of proliferation Ki-67 (MKI67). ASPM regulates microtubule dynamics at spindle poles.15 CENPF associates with the centromere-kinetochore complex, which is related to cell cycle, mitotic and G2/M transition.16 DIAPH3 is involved in actin remodeling and regulates cell movement and adhesion.17 TOP2A has been a target of several anticancer agents and was associated with drug resistance, TOP2A was increased in melphalan resistant rhabdomyosarcoma.18 MKI67 encodes a nuclear protein that is associated with and may be necessary for cellular proliferation. The proliferative activity by topoisomerase II-alpha immunohistochemistry decreased after chemotherapy for ERMS.19 Cytodifferentiation and decreased proliferative activity are associated with favorable outcomes in RMS; Unchanged or increased post-therapeutic proliferative activity suggests an aggressive biologic potential in ERMS.20 The C2 subgroup expressed marker genes titin (TTN), troponin T3 (TNNT3), septin 4 (SEPT4), myosin heavy chain 3 (MYH3). These genes are closely related to the proliferation and differentiation of skeletal muscles.21,22 All-trans retinoic acid changed the cellular morphology of RMS cells.23 Therefore, we speculate that C2 is a unique cell cluster for evaluating the malignancy potential of ERMS.

We further analyzed the difference in gene expression profiles of tumor cells and myoid cells.24 The differentially expressed genes were closely related to cell adhesion and extracellular matrix (ECM) signaling pathways. The changes of ECM signaling pathway genes are related to the development, invasion and metastasis of a variety of tumors, including testicular tumors.25,26 This suggests that ECM signals may be involved in the progression of testicular ERMS. Compared with myoid cells, PAX7 was highly expressed in tumor cells. PAX7 is a transcriptional regulator of mammalian muscle progenitor cells implicated in the pathogenesis of RMS.27,28 It is possible that PAX genes conferred the metastatic potential of testicular ERMS.29 In this study, the SCENIC analysis of the differential expression transcription factors found that SMARCA4, TCF12, RAD21, and FOXM1 were significantly downregulated in myoid cells. Patients with ERMS having high FOXM1 expression exhibited a shorter survival, and FOXM1 knockdown inhibited cell migration of RMS cell lines.30 RAD21 plays a role in DNA double-strand break repair and apoptotic pathways.31 SMARCA4 is a catalytic ATPase subunit that associated with cellular transformation.32 SMARCA4 bound the 3ʹUTR of miR-27a, which was regulated in muscles by the myogenic transcription factors MYF6, MYOD and MEF2C (which aligns with RMS features); knockdown of SMARCA4 or pharmacological inhibition of its bromodomain activity increased the expression of miR-27a in RMS.33

RMS is derived from striated muscle cells or mesenchymal cells differentiated into striated muscle cells. At present, the molecular mechanism of the occurrence and development of ERMS is not yet understood. Patients with RMS with local infiltration and hematogenous and lymphatic metastases have a poorer prognosis.34 We analyzed the relationship between macrophages and ERMS tumor cells. The macrophages derived from ERMS were divided into three subgroups (ie, M1, M2, M3) by UMAP. Trajectory analysis suggested that the M1 subgroup may be the initiating cells and transformed into M2 and M3 malignant cells. Collagen-related genes, including COL6A1, COL5A2, and COL3A1 in M3 subtype macrophages were highly expressed in the initial stage, but demonstrated low expression in the final stage. Similarly, when we analyzed the relationship between endothelial cells and ERMS tumor cells, we also found that the collagen-related genes COL6A1, COL5A2, and COL3A1 of the E1 subtype endothelial cells were highly expressed at the initial stage. The analysis of the interaction between the subgroups of cells found that the E2 subgroup of endothelial cells and the E3 subgroup of endothelial cells, C5 subgroup, and C6 subgroup have a strong interaction. These results indicate that collagen-related signaling pathways play important roles in macrophages and endothelial cells and promote the development of testicular ERMS.

ECM molecules play a key role in tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Tumor cells degrade the ECM by secreting various enzymes to invade and metastasize to surrounding and distant tissues, and promote tumor microvasculature.35,36 Collagen, one of the main components of the ECM is an important tissue barrier for cell migration, participates in cell survival and apoptosis, determines cell shape and controls cell differentiation and cell migration.37,38 Collagen VI A1 (COL6A1) is widely present in all connecting tissues. Studies have shown that COL6A1 can trigger signaling pathways related to apoptosis, inflammation, and tumor progression. COL6A1 knockout mice demonstrated a significant reduction in primary breast tumor growth.39 The interaction of COL6A1-NG2 participates in the metastasis and growth of human soft tissue sarcoma through dynamic cytoskeletal changes and Akt signaling.40 In this study, COL6A1 was highly expressed during the interaction between various cell types in ERMS tissue. Therefore, results suggest that COL6A1 plays a key role from the initiation of ERMS to the entire process of malignant transformation.

We focused on testicular embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma and it is an extremely rare sarcoma. It is difficult to collect samples from other parts, so we can only analyze one sample in this study. However, collecting more samples and verifying the findings in this article through experiments will promote the development of ESRM treatment targets and prognostic markers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report at the first time the testicular ERMS heterogeneity through snRNA-seq. Meanwhile, we provide important data resources for the follow-up researchers. We find that testicular ERMS tissue is composed of six different types of cells, which have different roles in the initiation and development of testicular ERMS. In addition, we found collagen-related gene such as COL6A1 played a key role in the development of testicular ERMS. Our findings provide a new insight in the understanding of the initiation and progression of testicular ERMS, and have potential value in the development of markers for the diagnosis and stratification of testicular ERMS.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by supported by Changsha Municipal Natural Science Foundation (kq2014033), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81802668, 82172832), Hunan Province Science Foundation for Young scientists of China (2020JJ5893), Wisdom Accumulation and Talent Cultivation Project of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (YX202108).

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Hao Bo, 1172881652@qq.com) on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University (2021KYKS-46). The patient and his guardian have provided written informed consent.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Gamboa AC, Gronchi A, Cardona K. Soft-tissue sarcoma in adults: an update on the current state of histiotype-specific management in an era of personalized medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):200–229. doi: 10.3322/caac.21605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kashi VP, Hatley ME, Galindo RL. Probing for a deeper understanding of rhabdomyosarcoma: insights from complementary model systems. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(7):426–439. doi: 10.1038/nrc3961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caballero Mora FJ, Munoz Calvo MT, Garcia Ros M, et al. Tumores testiculares y paratesticulares en la infancia y adolescencia. [Testicular and paratesticular tumors during childhood and adolescence]. An Pediatr. 2013;78(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2012.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley KS. Pediatric genitourinary tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23(3):297–302. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283458613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed HU, Arya M, Muneer A, Mushtaq I, Sebire NJ. Testicular and paratesticular tumours in the prepubertal population. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(5):476–483. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70012-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuart T, Satija R. Integrative single-cell analysis. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(5):257–272. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiselev VY, Andrews TS, Hemberg M. Challenges in unsupervised clustering of single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(5):273–282. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0088-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(7):923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(5):411–420. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meijer RJ, Goeman JJ. Multiple testing of gene sets from gene ontology: possibilities and pitfalls. Brief Bioinform. 2016;17(5):808–818. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabnis AJ, Guerriero CJ, Olivas V, et al. Combined chemical-genetic approach identifies cytosolic HSP70 dependence in rhabdomyosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(32):9015–9020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603883113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang SC, Ghossein RA, Bishop JA, et al. Novel PAX3-NCOA1 fusions in biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma with focal rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(1):51–59. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qian J, Olbrecht S, Boeckx B, et al. A pan-cancer blueprint of the heterogeneous tumor microenvironment revealed by single-cell profiling. Cell Res. 2020;30(9):745–762. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0355-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson MB, Sun X, Kodani A, et al. Aspm knockout ferret reveals an evolutionary mechanism governing cerebral cortical size. Nature. 2018;556(7701):370–375. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0035-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lokody I. Signalling: FOXM1 and CENPF: co-pilots driving prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(7):451. doi: 10.1038/nrc3772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stastna J, Pan X, Wang H, et al. Differing and isoform-specific roles for the formin DIAPH3 in plasma membrane blebbing and filopodia formation. Cell Res. 2012;22(4):728–745. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman HS, Dolan ME, Kaufmann SH, et al. Elevated DNA polymerase alpha, DNA polymerase beta, and DNA topoisomerase II in a melphalan-resistant rhabdomyosarcoma xenograft that is cross-resistant to nitrosoureas and topotecan. Cancer Res. 1994;54(13):3487–3493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith LM, Anderson JR, Coffin CM. Cytodifferentiation and clinical outcome after chemotherapy and radiation therapy for rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38(6):398–404. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coffin CM, Rulon J, Smith L, Bruggers C, White FV. Pathologic features of rhabdomyosarcoma before and after treatment: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(12):1175–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonin PN, Scrable H, Shimada H, Cavenee WK. Muscle-specific gene expression in rhabdomyosarcomas and stages of human fetal skeletal muscle development. Cancer Res. 1991;51(19):5100–5106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborn M, Hill C, Altmannsberger M, Weber K. Monoclonal antibodies to titin in conjunction with antibodies to desmin separate rhabdomyosarcomas from other tumor types. Lab Invest. 1986;55(1):101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barlow JW, Wiley JC, Mous M, et al. Differentiation of rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines using retinoic acid. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47(6):773–784. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters K, Caracciolo JT, Henderson-Jackson E, Binitie O. Myopericytoma/myopericytomatosis of the lower extremity in two young patients: a recently designated rare soft tissue neoplasm. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13(1):275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bo H, Cao K, Tang R, et al. A network-based approach to identify DNA methylation and its involved molecular pathways in testicular germ cell tumors. J Cancer. 2019;10(4):893–902. doi: 10.7150/jca.27491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bo H, Fan L, Li J, et al. High expression of lncRNA AFAP1-AS1 promotes the progression of colon cancer and predicts poor prognosis. J Cancer. 2018;9(24):4677–4683. doi: 10.7150/jca.26461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charville GW, Varma S, Forgo E, et al. PAX7 expression in rhabdomyosarcoma, related soft tissue tumors, and small round blue cell neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(10):1305–1315. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parham DM, Barr FG. Classification of rhabdomyosarcoma and its molecular basis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20(6):387–397. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182a92d0d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blake J, Ziman MR. Aberrant PAX3 and PAX7 expression. A link to the metastatic potential of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and cutaneous malignant melanoma? Histol Histopathol. 2003;18(2):529–539. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wan X, Yeung C, Kim SY, et al. Identification of FoxM1/Bub1b signaling pathway as a required component for growth and survival of rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72(22):5889–5899. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng H, Zhang N, Pati D. Cohesin subunit RAD21: from biology to disease. Gene. 2020;758:144966. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Q, Lian JB, Stein JL, Stein GS, Nickerson JA, Imbalzano AN. The BRG1 ATPase of human SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling enzymes as a driver of cancer. Epigenomics. 2017;9(6):919–931. doi: 10.2217/epi-2017-0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bharathy N, Berlow NE, Wang E, et al. The HDAC3-SMARCA4-miR-27a axis promotes expression of the PAX3: FOXO1fusion oncogene in rhabdomyosarcoma. Sci Signal. 2018;11(557). doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau7632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C. Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma: recent advances and prospective views. J Dent Res. 2012;91(4):341–350. doi: 10.1177/0022034511421490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker M, Moczar M, Poupon MF, Moczar E. Solubilization and degradation of extracellular matrix by various metastatic cell lines derived from a rat rhabdomyosarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;77(2):417–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almacellas-Rabaiget O, Monaco P, Huertas-Martinez J, et al. LOXL2 promotes oncogenic progression in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma independently of its catalytic activity. Cancer Lett. 2020;474:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haydn T, Kehr S, Willmann D, Metzger E, Schule R, Fulda S. Next-generation sequencing reveals a novel role of lysine-specific demethylase 1 in adhesion of rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(12):3435–3449. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu YF, Matsuo N, Sumiyoshi H. Yoshioka H. Sp7/Osterix is involved in the up-regulation of the mouse pro-alpha1(V) collagen gene (Col5a1) in osteoblastic cells. Matrix Biol. 2010;29(8):701–706. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iyengar P, Espina V, Williams TW, et al. Adipocyte-derived collagen VI affects early mammary tumor progression in vivo, demonstrating a critical interaction in the tumor/stroma microenvironment. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1163–1176. doi: 10.1172/JCI23424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cattaruzza S, Nicolosi PA, Braghetta P, et al. NG2/CSPG4-collagen type VI interplays putatively involved in the microenvironmental control of tumour engraftment and local expansion. J Mol Cell Biol. 2013;5(3):176–193. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]