Visual Abstract

Keywords: dialysis, antisepsis, audit tool, bacteremia, catheter, checklist, hemodialysis, infection, outpatients, quality improvement, vascular access

Key Points

Converting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's existing catheter checklists to an electronic format improved the ease of collating data for use in facility Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings.

The educational content was formatted for easy access with a mobile device, which was readily available for viewing by patients and staff.

Streamlining the processes used by facilities to perform checklists and audits could increase uptake of this important intervention.

Abstract

Background

Performing catheter-care observations in outpatient hemodialysis facilities are one of the CDC's core interventions, which have been proven to reduce bloodstream infections. However, staff have many competing responsibilities. Efforts to increase and streamline the process of performing observations are needed. We developed an electronic catheter checklist, formatted for easy access with a mobile device, and conducted a pilot project to determine the feasibility of implementing it in outpatient dialysis facilities.

Methods

The tool contained the following content: (1) patient education videos; (2) catheter-care checklists (connection, disconnection, and exit-site care); (3) prepilot and postpilot surveys; and (4) a pilot implementation guide. Participating hemodialysis facilities performed catheter-care observations on either a weekly or monthly schedule and provided feedback on implementation of the tool.

Results

The pilot data were collected from January 6 through March 12, 2020, at seven participating facilities. A total of 954 individual observations were performed. The catheter-connection, disconnection, and exit-site steps were performed correctly for most individual steps; however, areas for improvement were (1) allowing for appropriate antiseptic dry time, (2) avoiding contact after antisepsis, and (3) applying antibiotic ointment to the exit site. Postpilot feedback from staff was mostly favorable. Use of the electronic checklists facilitated patient engagement with staff and was preferred over paper checklists, because data are easily downloaded and available for use in facility Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement (QAPI) meetings. The educational video content was a unique learning opportunity for both patients and staff.

Conclusions

Converting the CDC's existing catheter checklists to electronic forms reduced paperwork and improved the ease of collating data for use during QAPI meetings. An additional benefit was the educational content provided on the tablet, which was readily available for viewing by patients and staff while in the hemodialysis facility.

Introduction

In the United States, >480,000 patients receive in-center hemodialysis at >6500 outpatient facilities (1). Infection is the second leading cause of death among patients on dialysis. The unique characteristics that may predispose to infection risk in this vulnerable population are the immunocompromised state of patients with ESKD, the requirement for frequent access to the bloodstream, and the shared treatment setting with exposure to other patients and staff. This risk is further increased by the high prevalence of central venous catheters (CVCs), which disproportionately contributes to bloodstream infections (BSIs) when compared with arteriovenous fistulas and grafts (2). In 2017, CVCs were the vascular access type in 80% of incident patients and they remained in use in approximately 19% of patients 1 year after hemodialysis initiation (1).

Patients on dialysis rely on their providers to follow best practices to prevent infection-related complications, hospitalizations, and death. To minimize these complications, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed a list of nine core interventions to prevent BSIs (3). Adherence to these core interventions has been associated with a 54% reduction in BSIs that was sustained over 4 years (4,5). One of the core interventions is quarterly performance of vascular access care observations, including catheter connection, disconnection, and exit-site care. The CDC currently provides audit tools on its website to print for use in dialysis facilities. Streamlining the processes used by facilities to perform checklists and audits could increase uptake of this important intervention. Understanding patients’ acceptability of electronic audits and whether this format could be used to further engage patients in their care could also improve facility uptake. Recently, members of the Vascular Access Workgroup, from the American Society of Nephrology's (ASN's) Nephrologists Transforming Dialysis Safety (NTDS) workgroup, developed an electronic chairside catheter checklist (ECC), which was formatted for easy access with a mobile device (e.g., tablet), and conducted a pilot to determine the feasibility in implementing this tool in outpatient hemodialysis facilities.

Materials and Methods

Development of the ECC and Associated Materials

Members of the ECC core development team included a patient with ESKD, a project specialist from the ASN-NTDS, two nephrologists, and an infection-prevention subject matter expert from the CDC. The ECC core team developed the tool using Google Forms. Tablets were provided that contained four icons on the home screen pertaining to the ECC: (1) patient education videos; (2) catheter-care checklists; (3) prepilot and postpilot surveys; and (4) general information, including a pilot implementation guide, a concise information sheet for staff, and an informational flyer for patients. (Figures 1–3)

Figure 1.

Dialysis care checklist. This is the appearance of the initial screen on the tool. The observer selects their title and which procedure they will be observing. APRN, advanced practice registered nurse; NTDS, Nephrologists Transforming Dialysis Safety; PA, physician assistant.

Figure 2.

Dialysis care checklist (second screen). Example of how one of several observations appear on the tool. This is the first observation for catheter connection procedure.

Figure 3.

Educational resources for patients are available to select on the tool for viewing. A variety of CDC infection prevention topics is included.

Patient education videos about hand hygiene, catheter-associated BSIs, catheter-care technique, and the “Clean Hands Count Campaign” were included on the tablets (6–11). To further engage and educate patients about the catheter-care process, a handheld mirror was provided to patients to view the procedures.

Three checklists were developed on the basis of the CDC's audit tools (6): catheter connection, disconnection, and exit-site care. Catheter-care videos were embedded in the tool for staff education. A watch was provided so observers could time specific steps.

Prepilot data were collected from team leaders on how facilities were currently conducting observations of catheter care, including who was responsible for performing the observations, which paper forms were used, and how many were completed in the 3 months before pilot initiation. Participating patients completed prepilot surveys using the tool and provided information on how they would rate their baseline knowledge of catheter connection, disconnection, and exit-site care protocols; their duration of catheter dependence; any past catheter-related infections; and comfort level in reminding staff to perform hand hygiene.

Postpilot surveys (entered into the tool) collected feedback from team leaders, other staff observers, and patients about implementation of the ECC tool, including the perceived benefits of use, barriers encountered, and if it contributed to delays in hemodialysis, changed staff technique, or improved patient knowledge or engagement.

Participating Facilities and Staff Performing Observations

Participation in the pilot was voluntary; individual hemodialysis facilities affiliated with members of the NTDS were invited to participate, and these included both for-profit and not-for-profit, freestanding hemodialysis facilities, which were situated in different geographic regions of the United States. This project was reviewed by human subjects at the CDC and deemed to be nonresearch. Before implementation of the pilot, approval was obtained from the owners of the hemodialysis facilities.

Participating facilities identified a team leader to teach staff how and when to use the ECC, to speak to patients about the ECC and introduce them to educational materials, and to encourage staff use of the ECC throughout the duration of the pilot. Observers included staff familiar with the steps involved in catheter care, such as registered nurses, physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners, physicians, and dialysis technicians. Facilities were asked to complete the checklists at least monthly for each patient. Observers were provided information on how to address a colleague when a step was missed.

In December 2019, the ECC core team conducted two 1-hour webinars to provide pilot facilities instructions on how to use tool. A 3-month pilot was planned, from January 1, 2020 until March 31, 2020; however, the pilot was stopped prematurely due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on March 12, 2020.

Data Collection and Analysis

Results from all participating hemodialysis facilities were collected by the NTDS Vascular Access Workgroup. No patient identifiers were collected, and each facility was deidentified. Data were downloaded from the ECC tool into Microsoft Excel and then analyzed using Stata 14.0.

An observation was defined as completion of a checklist step (i.e., catheter connection, disconnection, or exit-site care). The specific steps were summarized and described as completed or not completed. If a staff member required a reminder to complete a step, it was counted as not completed or missed. The number of times checklist results were reviewed (e.g., for quality-improvement purposes) or procedure videos were viewed were summarized. All surveys were recorded as a five-point Likert scale.

Data that were normally distributed and where the sample size was large are reported as means±SDs. Results are reported as percentages where appropriate. Non-normally distributed data with a small sample size (e.g., the number of catheter patients per week) were reported as the median (interquartile range). Because this was a descriptive feasibility project, no statistical analysis was performed.

Results

Of the ten outpatient hemodialysis facilities invited to participate in the ECC pilot, seven agreed. The main reasons cited for declining to participate included lack of adequate staffing and time restraints. The participating facilities included five hospital-affiliated units (four with Emory Healthcare in Atlanta, GA, and one with Altru Health System in Grand Forks, ND) and two units that were affiliated with DaVita Kidney Care in New York City, New York (Bronx). The four Atlanta clinics performed at least monthly observations, whereas the three other units performed weekly.

Prepilot Data

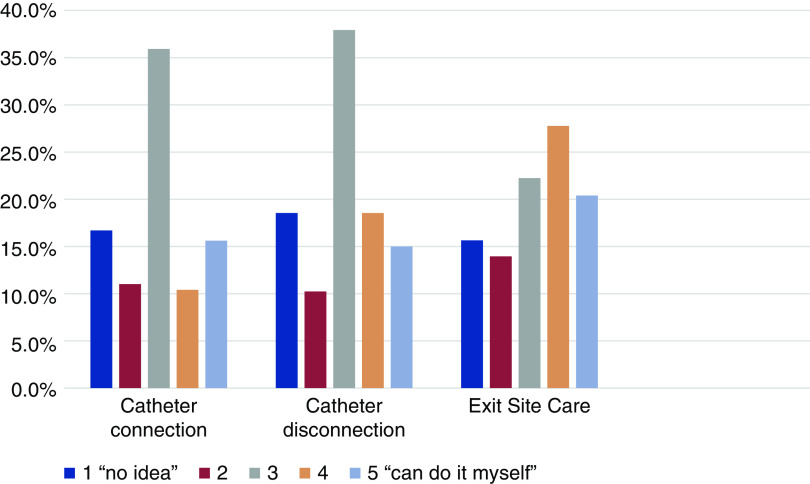

Baseline prepilot data provided by the facility team leaders are provided in Table 1. In the 3 months preceding the implementation of the pilot, the total number of catheter-dependent patients treated weekly at all seven pilot facilities combined was 176 patients, and the median number treated per week at each hemodialysis facility was 26 (range, 17–36) patients. In the prepilot period, the mean number of catheter connections, disconnections, and exit-site care observations was 12 per month for each observation type, (range between 1–5 and >20). The baseline patient prepilot survey data are provided in Figure 4 and Table 2. A total of 108 patients completed the prepilot survey using the tool, and 17 (16%) reported having had a catheter-related infection in the past. The duration of catheter use was <1 month (13%), 1–6 months (36%), 6–12 months (19%), and >12 months (32%). Most patients rated their knowledge of the protocol for catheter procedures as “average.” Almost all patients (93%) reported they felt comfortable reminding hemodialysis staff to perform hand hygiene.

Table 1.

Results of prepilot, team-leader surveys

| Facility | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Median number of CVC patients per week | 34 | 17 | 28 | 22 | 36 | 26 | 13 |

| Total patient audits per month for months 1–3 (prepilot CVC connection) | 1–5 | 6–10 | >20 | 1–5 | >20 | 1–5 | 1–5 |

| Total patient audits per month for months 1–3 (prepilot CVC disconnection) | 1–5 | 6–10 | >20 | 1–5 | >20 | 1–5 | 1–5 |

| Total patient audits per month for months 1–3 (prepilot CVC exit-site care) | 1–5 | 6–10 | >20 | 1–5 | >20 | 1–5 | 1–5 |

CVC, central venous catheter.

Figure 4.

Prepilot survey of patient knowledge about catheter-care procedures. Responses to the question “how would you rate your knowledge about the steps the staff take to connect and disconnect your catheter, and about the protocol for exit-site care?” Most patients report an "average" knowledge about catheter care procedures.

Table 2.

Results of prepilot patient surveys

| Facility | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Patient respondents, N | 13 | 16 | 4 | 29 | 17 | 13 | 16 |

| How would you rate your knowledge about the steps the staff take to connect your CVC at the start of treatment? | 3.08 (1.44) | 3.38 (1.02) | 4.25 (0.96) | 3.34 (1.14) | 2.41 (1.12) | 3.46 (1.45) | 2.38 (1.12) |

| How would you rate your knowledge about the steps the staff take to disconnect your CVC at the end of treatment? | 3.08 (1.44) | 3.06 (1.06) | 4.25 (0.96) | 3.28 (1.22) | 2.41 (1.06) | 3.54 (1.45) | 2.31 (1.14) |

| How would you rate your knowledge about the protocol for CVC exit-site care? | 3.85 (1.28) | 3.43 (1.15) | 4.00 (1.41) | 3.41 (1.3) | 2.88 (1.27) | 3.31 (1.65) | 2.31 (1.14) |

Surveys used the Likert scale with one representing “I have no idea what they are doing” to five representing “I could do it myself.” Data reported as the mean (SD). CVC, central venous catheter.

ECC Pilot Results

The pilot data were collected from January 6 through March 12, 2020. The observations were performed by a registered nurse, nurse practitioner, PA, physician, or dialysis technician. (Figure 5) A total of 954 individual observations were performed during the pilot period using the ECC tool: observations were made in CVC connection (n=361), disconnection (n=305), or exit-site care (n=288) (Table 3). Over the pilot period, the range of observations in facilities A–D (monthly observations) was between 21 and 124, and was between 218 and 276 in facilities E–G (weekly observations).

Figure 5.

Type of observer using the electronic catheter checklist for each pilot facility. In facilities A–E, nursing staff and technicians performed the majority of observations. In facilities F and G, most observations were performed by nursing staff, physician assistants or technicians.

Table 3.

Results of the electronic catheter checklist pilot project

| Facility | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Total observations or reviews (viewing results or procedure videos), N | 29 | 83 | 21 | 124 | 224 | 276 | 218 |

| CVC connection, N (%) | 10 (35) | 27 (33) | 9 (43) | 42 (34) | 81 (36) | 122 (38) | 70 (32) |

| CVC disconnection, N (%) | 6 (21) | 31 (37) | 8 (38) | 44 (36) | 60 (27) | 82 (30) | 74 (34) |

| CVC exit-site care, N (%) | 11 (38) | 25 (30) | 4 (19) | 38 (31) | 71 (32) | 69 (25) | 70 (32) |

| View checklist results, N (%) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (5) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Watch proper procedure videos, N (%) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) |

CVC, central venous catheter.

The proportion of steps completed correctly for each CVC observation for all pilot facilities combined is provided in Figures 6–8. Most steps were performed correctly. Steps in which there were lapses in technique, requiring the observer to remind staff of the recommended antiseptic protocol, were: (1) allowing for appropriate antiseptic dry time during catheter connection (10%) and disconnection (5%), (2) avoiding contact after antisepsis during exit-site care (28%), and (3) applying antibiotic ointment to the catheter exit site (27%).

Figure 6.

Catheter connection observation results (n=361). The step for which there was a lapse in technique was allowing for the "appropriate antiseptic dry time". All other catheter connection steps were performed as recommended in >99% of the time.

Figure 7.

Catheter disconnection procedures (N=305). The step for which there was a lapse in technique was allowing for the "appropriate antiseptic dry time". All other catheter disconnection steps were performed as recommended in >99% of the time.

Figure 8.

Catheter exit-site procedures (n=288). The steps for which there was a lapse in technique were "avoiding contact after antisepsis" and "applying antibiotic ointment". *One facility did not routinely use antibiotic ointment which explains this finding. All other steps were performed as recommended in >94% of the time.

The products used for catheter care varied across facilities. All four facilities in Atlanta used Tego connectors, which are changed weekly. In the two New York hemodialysis facilities, the CVC hub caps were changed with each treatment and replaced with ClearGuard HD (Pursuit Vascular, Maple Grove, MN) antimicrobial caps. In the Grand Forks facility, the hub cap was replaced by a 3M Curos cap weekly. The antiseptic product most commonly used for skin antisepsis was chlorhexidine gluconate with 70% alcohol, followed by sodium hypochlorite and 70% isopropyl alcohol. One facility reported using normal saline for exit-site care in a patient who had refused “chemicals” and antiseptic agents. Use of antibiotic ointment at the catheter exit site was part of the routine care at six of the seven hemodialysis facilities and adherence was 100%. One of the two facilities in New York did not include antimicrobial ointment as part of the routine catheter care and reserved its use for exit-site infections (observed in only 3% of procedures).

The checklist results were reviewed on 19 occasions. The majority of these occurred at the three facilities that performed weekly audits (12 views at facility E, three views at facility F, three views at facility G), and in one facility that performed monthly observations (one view at facility A). The "best practice" procedural videos were viewed by staff twice.

Postpilot Feedback

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the postpilot surveys were not completed. Team leaders provided feedback during a virtual town-hall meeting in October 2020. The electronic format was preferred over the paper forms, because data analysis was automatic and viewing the data in an aggregate format was “convenient.” Paper audit tools had the risk of being misplaced and required separate calculations to perform an analysis for use at the monthly facility meeting. In addition, the ECC tool could be modified more easily by individual facilities to reflect facility-specific practices.

The additional staffing time required to perform frequent observations was challenging. Each observation required an average of an additional 10–15 minutes per patient. One team leader, assigned to conduct weekly observations, stated the pilot effort accounted for as much as 40% of her time on the days she was conducting the observations. Another leader stated that weekly scheduling of observations “was an extremely time-consuming process.” To protect their time, the team leaders enlisted other hemodialysis staff to perform observations; however, motivation quickly waned because it added to their heavy workload, without additional compensation.

Additional challenges included the timing of observations: (1) missing catheter-connection steps for patients with early morning start times; (2) nursing staff having to notify the observer when catheter care will occur; and (3) multiple patients undergoing care simultaneously, limiting the ability to observe all.

Staff reported improved patient engagement. At one facility, the staff found the ECC observations to be a learning opportunity for assessing gaps in patient knowledge about catheter care. The tool also facilitated communication from the nursing staff to the patients on the challenges of adherence to optimal antiseptic technique. Team leaders offered to assist the patients in selecting the educational videos available on the tool; however, in some instances, patients were disinterested and declined.

Participating facilities provided the following suggestions for optimizing future use of the ECC: (1) limit observations to a monthly or quarterly schedule, (2) recruit multiple staff members to share responsibility for performing audits, and (3) provide additional staff compensation for time required to perform observations.

Discussion

The CDC core interventions, which include the use of catheter-care observations, have been proven to be effective in reducing rates of hemodialysis catheter–associated BSIs (3–5,12), and checklists have been used for the prevention of BSIs in other settings (13,14). We explored whether converting catheter-care checklists to an electronic format facilitated performance of observations in busy outpatient hemodialysis facilities.

Staff noted some benefits to the electronic format. The reduction in paperwork and improved ease of collating data for use during facility Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings was widely noted to be a benefit. The staff also noted that the electronic format allowed for easier transfer of data into the national database for reporting purposes. The data collected during the pilot were reviewed more frequently in the three facilities assigned to a schedule of weekly observations, whereas only one facility assigned to perform monthly observations reviewed their facility's results. This finding may have been due to limited data available in those facilities performing less frequent observations and early termination of the pilot. Another advantage to the electronic tool is that individual steps could be easily modified by the individual facility, such as type of antiseptic agent used, type of catheter hub device, and type of antibiotic ointment or dressing applied at the exit site.

Although the CDC educational videos provide “best-practice” instructions for staff, they were infrequently used. This may be because the staff completing the audits were already familiar with the steps and did not feel they needed the additional instruction. Furthermore, viewing the videos in real time is likely impractical given how quickly the steps occur during catheter care. Ideally, staff would view the videos before performing observations.

The prepilot survey revealed that the extent of patients’ knowledge about catheter-care steps was wide ranging, from “no idea” to “proficient in self-care.” Educating patients about the correct methods for performing each step, and the importance of performing meticulous catheter care, is central to improving patient safety. In general, use of the ECC tool provided opportunities to engage patients in discussions. However, experiences varied by facility regarding patient interest in watching the videos. Utilization of the ECC tool for patient education will require that the staff have time to illustrate its content to patients. In the future, allowing patients to use the tool independently may increase video viewings and opportunities for patient engagement and education. The educational content available in the tool may be easily modified or developed by individual facilities to better meet their specific patient needs.

The drawbacks cited by staff regarding use of the ECC tool primarily reflected the challenges of performing observations in general and were not directly related to the electronic format. Staff had to complete their other duties and perform observations, and the time required for this was considerable. All team leaders agreed that weekly observations demanded too much time away from patient-care responsibilities, and that performing observations monthly or every 3 months, as is currently recommended by the CDC, was preferred. Recruiting and training more frontline staff members to perform observations may increase the likelihood that performing the observations monthly becomes standard practice in the future and may provide additional education and training. Once staff feel more familiar with the ECC, there may be more interest to further explore additional educational features (e.g., videos).

During the pilot-project period, we found a high degree (>95%) of adherence to most catheter-care steps. This may be attributable to the Hawthorne effect, where the observer's presence improves adherence to antiseptic practice and improves patient safety. However, some areas for improvement were identified. One is the need to educate staff on appropriate antiseptic drying time, performed correctly in only 90% of cases, which required a reminder by the observer in the remaining 10%. One way to address this deficiency is to make best-practice information for each product in use at the facility more readily available to staff. This information can be reviewed regularly in facility staff meetings or posted in the dialysis station on a laminated card that can be disinfected. In addition, the electronic tool can be customized to add facility-specific information on such practices.

Limitations of the project included the relatively short duration, which was further decreased when the COVID-19 pandemic started to consume staff time. The pilot was implemented in only seven facilities and there was common ownership across some of the facilities, so variations in facility policies or practices that might increase or decrease acceptability of tool may not have been identified. This was an observational feasibility project and was not powered to determine efficacy. The postpilot surveys were not completed, and feedback was obtained in a town-hall format, limiting the ability to assess some components of the implementation, such as how patients rated their catheter-care knowledge postimplementation.

In summary, the utilization of an ECC to perform chairside audits in hemodialysis facilities was preferred over existing paper audit tools. Furthermore, the ECC provided aggregated, real-time data that could be shared during the facility Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings. An additional unique aspect of the ECC tool is the incorporation of educational videos available to patients and staff. Unfortunately, the electronic format did not alleviate required staff time, one of the primary barriers to performing observations. Adequate support for hemodialysis staff and protection of their time to perform ECC observations are necessary to prevent task stacking and to improve catheter care.

Disclosures

L. Golestaneh reports receiving compensation from the Cardiovascular Research Foundation for fulfillment of duties as a member of the clinical events committee for the Spyral Hypertension trials, sponsored by Medtronic; and receiving honoraria from Horizon Pharmaceuticals. A. Kliger reports having consultancy agreements with ASN and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; having other interests/relationships with ASN and Renal Physicians Association; being a scientific advisor for, or member of, Qualidigm (quality-improvement organization); and receiving honoraria for lectures, seminars, and webinars from several universities, medical schools, and professional organizations. M. Mokrzycki reports receiving compensation from the Cardiovascular Research Foundation for fulfillment of duties as a member of the Clinical Events Committee for the following clinical trials: Medtronic Global Simplicity Registry, Medtronic Spyral HTN On/Off Meds, RECOR MEDICAL/RADIANCE II, Medtronic Spyral Dystal trial, and BOA GARNET trial; and receiving honoraria from Spherix Global Insights. V. Niyyar reports receiving honoraria as invited faculty for Albert Einstein–Montefiore and KidneyCon; receiving honoraria for being an invited speaker for the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology (ASDIN), American Society of Nephrology (ASN), ASN Highlights, and National Kidney Foundation; receiving honoraria from Ardea Biosciences; having previous consultancy agreements with Ardea Biosciences, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (finished December 2018), and Lesinurad; being a scientific advisor for, or member of, the ASDIN (as president elect, previously secretary treasurer and councilor, chair, US certification committee, Hemodialysis Vascular Access certification committee), ASN Committee of Continuing Professional Development – 2018, ASN Interventional Nephrology Advisory Group, and Kidney Health Initiative – ASN/Food and Drug Administration (as member of the graft committee); having other interests/relationships with Commdex Consulting; receiving honoraria for serving on the renal event adjudication committee for Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; receiving honoraria for being on the advisory board for Lesinurad. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was supported by funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to ASN, contract # 200-2016-88832.

Acknowledgments

The team leaders who performed the observations were Linda Mathew (PA), Dulce Balcacer (PA), Forest Rawls (CCHT-A, CHT, FNKF), and Rodella Broxton (LPN). The medical directors at each hemodialysis facility were: Dr. Maria Coco, Dr. Adeola Haastrup, Dr. Jeff Sands, Dr. Janice Lea, Dr. Tahsin Masud, and Dr. James Someren.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US CDC.

Author Contributions

V. Bren Asp, L. Golestaneh, A. Kliger, M. Mokrzycki, V. Niyyar, and S. Novosad reviewed and edited the manuscript; V. Bren Asp, K. Leigh, M. Mokrzycki, V. Niyyar, and S. Novosad were responsible for project administration; L. Golestaneh and M. Mokrzycki were responsible for formal analysis; A. Kliger, K. Leigh, M. Mokrzycki, V. Niyyar, S. Novosad, and Q. Taylor conceptualized the study; A. Kliger, K. Leigh, V. Niyyar, and Q. Taylor were responsible for methodology; A. Kliger, M. Mokrzycki, and V. Niyyar provided supervision; K. Leigh was responsible for resources and software; K. Leigh and M. Mokrzycki were responsible for visualization; K. Leigh, M. Mokrzycki, and V. Niyyar were responsible for data curation; M. Mokrzycki was responsible for investigation and wrote the original draft.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System: Annual Data Report, 2020. Available at: https://adr.usrds.org/2020. Accessed October 31, 2020.

- 2.Nguyen DB, Shugart A, Lines C, Shah AB, Edwards J, Pollock D, Sievert D, Patel PR: National healthcare safety network (NHSN) dialysis event surveillance report for 2014. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1139–1146, 2017. 10.2215/CJN.11411116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Dialysis safety core interventions, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/dialysis/prevention-tools/core-interventions.html. Accessed November 24, 2019

- 4.Patel PR, Yi SH, Booth S, Bren V, Downham G, Hess S, Kelley K, Lincoln M, Morrissette K, Lindberg C, Jernigan JA, Kallen AJ: Bloodstream infection rates in outpatient hemodialysis facilities participating in a collaborative prevention effort: A quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 322–330, 2013. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yi SH, Kallen AJ, Hess S, Bren VR, Lincoln ME, Downham G, Kelley K, Booth SL, Weirich H, Shugart A, Lines C, Melville A, Jernigan JA, Kleinbaum DG, Patel PR: Sustained infection reduction in outpatient hemodialysis centers participating in a collaborative bloodstream infection prevention effort. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37: 863–866, 2016. 10.1017/ice.2016.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campaign Safe Care: Proper hand hygiene, 2012. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tZnKlFtAUDw&feature=youtu.be. Accessed June 14, 2019

- 7.SCCMEDIATV : Hand hygiene saves lives – CDC Video, 2012. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CUoht_RmF4&feature=youtu.be. Accessed June 14, 2019

- 8.Campaign Safe Care: Preventing bloodstream infections, 2012. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFROH5rvWOY&feature=youtu.be. Accessed June 14, 2019

- 9.FAQs about "Catheter-Associated Bloodstream Infections". Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/bsi/BSI_tagged.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2019

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Preventing bloodstream infections in outpatient hemodialysis patients, 2013. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0zhY0JMGCA. Accessed June 14, 2019

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Speak up—Video for patients, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/dialysis/patient/speak-up-video.html. Accessed November 24, 2020

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Dialysis safety core interventions, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/dialysis/prevention-tools/core-interventions.html. Accessed November 24, 2019

- 13.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, Sinopoli D, Chu H, Cosgrove S, Sexton B, Hyzy R, Welsh R, Roth G, Bander J, Kepros J, Goeschel C: An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 355: 2725–2732, 2006. 10.1056/NEJMoa061115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wichmann D, Belmar Campos CE, Ehrhardt S, Kock T, Weber C, Rohde H, Kluge S: Efficacy of introducing a checklist to reduce central venous line associated bloodstream infections in the ICU caring for adult patients. BMC Infect Dis 18: 267, 2018. 10.1186/s12879-018-3178-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]