As coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) takes its toll worldwide, from the perspective of noncommunicable disease (NCD) physicians and activists it feels as if the world has suddenly woken up to the fact that NCDs are important and have been neglected. NCDs no longer only affect the affluent and the elderly. Indeed, NCDs take a major toll on the world's poorest billion given the confluence of poverty-associated risk factors and inadequate access to screening, early diagnosis, and early treatment (1). NCDs kill 41 million people every year (71% of all deaths) (2).

The first United Nations High Level Meeting (UNHLM) on NCDs in 2011 highlighted that NCDs were the leading global cause of deaths, but as recently acknowledged at the third UNHLM on NCDs in 2018, despite small progress for some NCDs, action has not been sufficient. A major contributor to NCDs having been left behind is the fact that since 2000, only 1%–2% of development aid to low-income countries and low- and middle-income countries has been allocated toward NCDs despite their comprising over 75% of the disease-adjusted life year burden and being the leading causes of death (Figure 1) (3). This disproportion was likely driven in part by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which led countries to focus efforts on meeting the targets that excluded NCDs. Furthermore, infectious diseases may have been prioritized because they are typically thought to be acute, require urgent treatment, be relatively cheap and simple to treat, be reversible, be contagious, and affect vulnerable populations; from the donor perspective, the effect of targeted programs is relatively easy to measure within short time frames. Each of these criteria with the exception of the time required to assess program effect, however, can be argued to apply equally to NCDs and cannot, therefore, ethically or morally justify the differential and inequitable approach to communicable diseases versus NCDs taken thus far (Table 1) (4). The call is not to reduce or reallocate funding for communicable diseases but in parallel to increase funding for NCDs and optimize synergies between the approaches to communicable diseases and NCDs, such that efficiencies, quality of care, and the likelihood of sustainability are maximized.

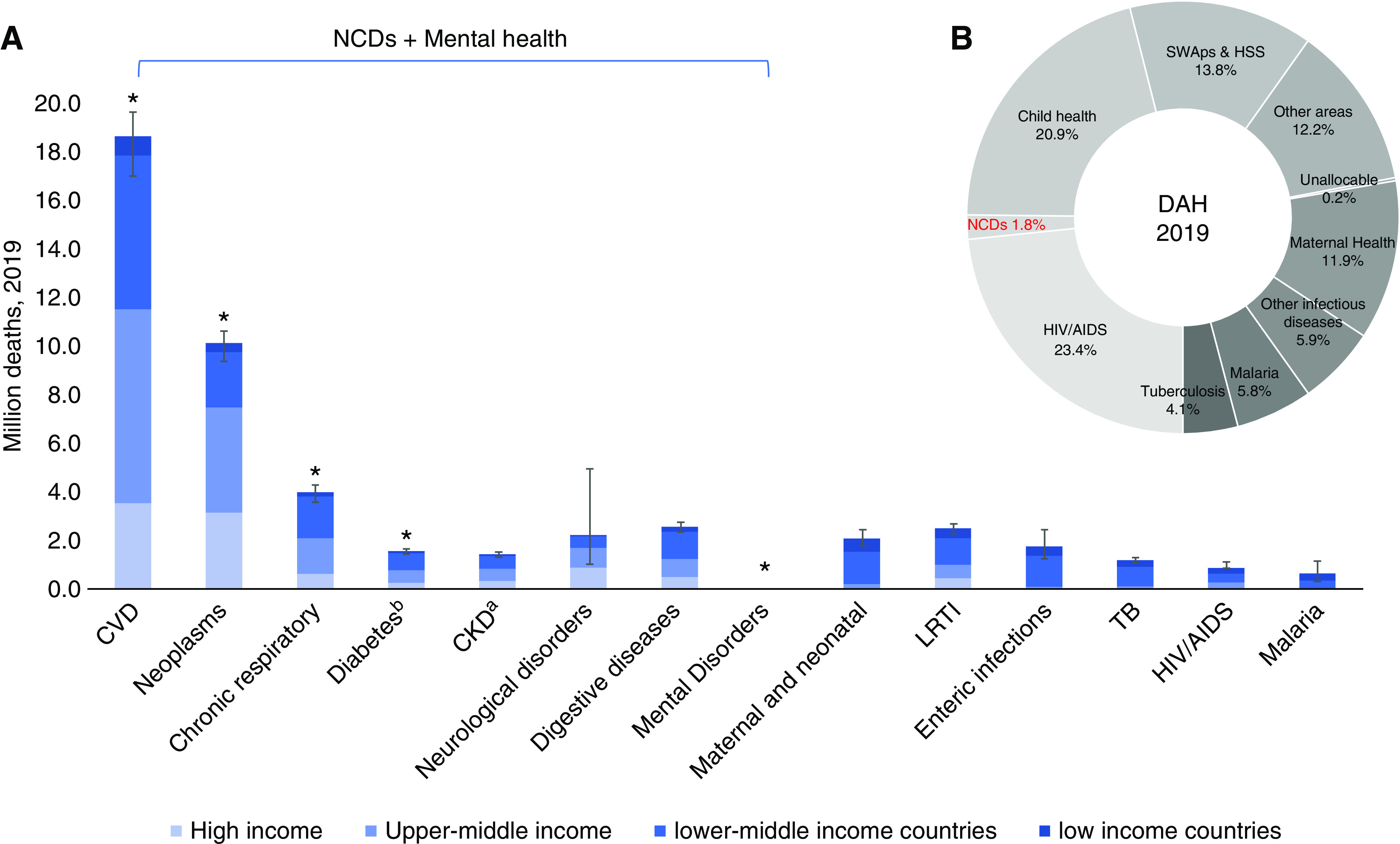

Figure 1.

Distribution of leading causes of total global deaths and related allocation of Development Assistance for Health in 2019. (A) Total deaths by leading disease groups stratified by World Bank country income category in 2019. Error bars indicate upper and lower limits for global totals. (B) The relative allocations of total development assistance for health (DAH) transferred in 2019. Total DAH transferred in 2019 was United States $41 billion; this included United States $730 million (1.8%) for all noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including mental health. Suballocation of the United States $730 million transferred for NCDs included mental health (21.1%), other NCDs (45.9%), health systems support (HSS; 7.9%), human resources (16.1%), and tobacco (9%). DAH refers to financial and in-kind resources distributed by major health development agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and countries to low- and middle-income countries, with the goal of improving or maintaining health. Data were obtained from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/fgh/ and https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. CVD, cardiovascular disease including stroke; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; SWAp, sector-wide approach; TB, tuberculosis. aCKD deaths exclude deaths from AKI and deaths among those not able to access dialysis/transplantation (estimated 2–7 million in 2010) (5); global mortality attributed to reduced kidney function was 3.16 million in 2019. bDiabetes deaths exclude the contribution to mortality from other disorders attributed to elevated fasting blood sugar (6.5 million in 2019). *Current global priority NCDs.

Table 1.

Potential reasons why infectious diseases may historically have been prioritized over noncommunicable diseases and their relevance to both disease groups

| Potential Justification | Communicable Diseases | Noncommunicable Diseases |

| Preventable | ✓ | ✓ With Best Buys, HPV vaccination (e.g., hypertension, cervical cancer) |

| Acute reversible disease | ✓ | ✓ With early diagnosis and treatment (e.g., AKI, myocardial infarction, acute stroke) |

| Curable | ✓ | ✓ With early diagnosis and treatment (e.g., cervical cancer, AKI, GN) |

| Chronically controllable | ✓ | ✓ With UHC and access to essential diagnostics and medicines (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, CKD) |

| Contagious | ✓ | ✓ Socially and environmentally (e.g., obesity, diabetes, chronic lung disease) |

| Cost effective | ✓ | ✓ For example, Best Buys save money and lives |

| Affects most vulnerable | ✓ | ✓ Highest premature mortality in LMICs, children largely overlooked |

| Individuals are not considered to blame | ✓ | ✓ Healthy choices are limited for the most vulnerable (e.g., food deserts in poor urban areas) |

| Amenable to vertical programs | ✓ | X Requires health system–wide approach of access to good quality care across the life course |

| Quick win for donors | ✓ | X Requires long-term view |

World Health Organization Best Buys are at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259232. ✓, applicable; HPV, human papilloma virus; UHC, universal health coverage; LMICs, low- and middle-income countries; X, not applicable. Adapted from ref. 4, with permission.

As the focus on the NCD burden has increased in recent years, inequities within the approach to NCDs themselves have, however, also arisen. Since 2008, the global response to NCDs has concentrated on four and then five major contributors to NCD morbidity and mortality (cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and mental health), but this approach overlooks many other NCDs, some of which are leading killers in some regions, such as kidney disease in Oceania and Central America (5). From the response to the MDGs, it is clear that if countries are given specific disease targets to meet and report on, other diseases are likely to be relatively neglected. The focus on these priority NCDs is not wrong but should not be interpreted as exclusive. Many people living with one NCD have another NCD. Indeed, people with kidney disease tend to have the highest rates of comorbidities (6). People living with NCDs, including kidney disease, are also frequently affected by infectious diseases, either acutely due to their enhanced susceptibility to infection and severity, as we are witnessing daily in the COVID-19 pandemic, or through chronic infections, such as HIV, tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C, and human papilloma virus, which may cause chronic disease. Furthermore, exposure to systemic discrimination and structural violence enhances vulnerability and therefore, susceptibility to NCDs, as well as increasing risk of exposure to infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, tuberculosis, and COVID-19) and disease severity (7). NCDs themselves, in turn, enhance disadvantage and vulnerability through chronic ill health and exacerbation of poverty (8). NCDs, like kidney disease, are, therefore, at the epicenter of the cycle of risk for infections, worsening health, poverty, and vulnerability. NCDs are complex and require a holistic, comprehensive, and long-term view toward prevention and optimal management, which has thus far been lacking in many places globally. The inextricable interdependencies of social and political context, structural violence, and both communicable diseases and NCDs have been described as “syndemic vulnerability” (9)—a new approach is urgently needed to tackle this paradigm systematically and effectively.

It is important to recognize that NCD risk, including kidney disease risk, begins in utero and is amplified throughout the life course. A holistic approach to wellness, as highlighted by the sustainable development goals (SDGs), offers the opportunity to stem the tide of NCDs at the source. Babies born preterm or with low birth weights are at increased risk of NCDs (10). This risk can be mitigated through adherence to healthy lifestyles and mitigation of the social determinants of ill-health throughout the life course. Healthy women and girls who are well nourished, are educated, are safe, and have equal opportunities are more likely to have planned pregnancies, have healthy babies, have healthier children and families, and earn more (10). Prevention of NCDs should be facilitated through ensuring freedom from discrimination and structural violence, regulation of the commercial determinants of health and environmental pollution, ensuring equitable access to public health, primary and antenatal care, equal education and opportunities for all, and affordable healthy foods, as well as safe environments and fair employment opportunities. Prevention of NCDs should begin in utero and continue throughout life to strive toward healthy people living in healthy cities on a healthy planet. Comprehensive multisectoral action is required, beyond the health system.

Effective management of NCDs requires a horizontal integrated approach within the health system. Achieving universal health coverage (UHC) will be key to improving access to care, but NCDs, most especially kidney disease, remain major causes of catastrophic health expenditure even when UHC is in place (11). UHC is, therefore, not sufficient to ensure sustainable access to NCD care (11). Close attention to the delivery of quality care (the lack of which is a major cause of NCD deaths [12]) is critical, incorporating adequate training and support of the health care workforce as well as ensuring reliable infrastructure and supplies. People living with NCDs receive most of their care through self-care; people, therefore, need to be empowered with knowledge and the means with which to look after themselves and manage their diseases, having access not only to primary care, which is the first step, but also, to healthy food, education, lack of discrimination, safe living and work environments, and (psycho-)social support. Simultaneous multisectoral attention is required to address the social determinants of health as major amplifiers of NCD risk and severity, as highlighted by the SDGs, to ultimately alleviate poverty and to create opportunities for individuals to maximize their well-being.

The NCD community is heartened by the strong call to “Build Back Better” and strengthen health systems worldwide to incorporate sustainable and effective approaches to manage and reduce the NCD burden. The need for an ethical approach to policy making and priority setting regarding NCDs has been highlighted by the World Health Organization High Level Commission for NCDs (13) as a prerequisite to enhance equity. The economic and disease burden arguments to tackle NCDs are strong (1,14) but alone, have not thus far been enough to motivate concerted action. Building Back Better may be easier said than done but should be possible with deliberate and patient action.

Equity, across diseases, ethnicities, age, sex, and countries, must be a core goal of the “Building Back Better” strategy for NCDs on the basis of ethical, medical, economic, and public health grounds. Funding and efforts must not be diverted away from infectious diseases, which as COVID-19 has glaringly demonstrated, continue to require attention—but simultaneously, funding and cooperation for NCDs must be increased. Debates regarding access to the potential COVID-19 vaccines highlight that these could be considered “public goods”—everyone should have a right of access at a fair price. Such sentiments and any processes developed should serve as a blueprint upon which to advocate for similarly equitable and affordable access to a spectrum of many other lifesaving treatments, especially those for NCDs ranging from basic antihypertensives and insulin to dialysis, transplantation, cancer treatment, and many others, which have thus far remained out of reach for many in lower-income settings. International and multisectoral action and solidarity are needed now to accelerate global progress toward UHC and toward achievement of the SDGs, such that prevention of NCDs, including kidney disease, and access to equitable and quality care can become a global reality (15).

Disclosures

V.A. Luyckx reports honoraria as an invited speaker at the German Nephrology Meeting, a speaker at Grand Rounds Brigham and Women's Hospital Renal Division and Visting Professor in Nephrology at the University of Miami; she is a member of the Advocacy Committee of the International Society of Nephrology and serves on the on editorial boards of CJASN, Current Opinion in Nephrology, Kidney360, Seminars in Nephrology and Nature Reviews Nephrology; she reports royalties from Elsevier as co-editor of the textbook The Kidney.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the author(s) and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or Kidney360. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Author Contributions

V.A. Luyckx conceptualized the study, was responsible for data curation, and wrote the original draft.

References

- 1.Bukhman G, Mocumbi AO, Atun R, Becker AE, Bhutta Z, Binagwaho A, Clinton C, Coates MM, Dain K, Ezzati M, Gottlieb G, Gupta I, Gupta N, Hyder AA, Jain Y, Kruk ME, Makani J, Marx A, Miranda JJ, Norheim OF, Nugent R, Roy N, Stefan C, Wallis L, Mayosi B; Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission Study Group: The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission: Bridging a gap in universal health coverage for the poorest billion. Lancet 396: 991–1044, 2020. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31907-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization : Noncommunicable diseases: Key facts, 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. Accessed October 5, 2020

- 3.Allen LN: Financing national non-communicable disease responses. Glob Health Action 10: 1326687, 2017. 10.1080/16549716.2017.1326687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luna F, Luyckx VA: Why have non-communicable diseases been left behind? Asian Bioeth Rev 12: 5–25, 2020. 10.1007/s41649-020-00112-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration: Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395: 709–733, 2020. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Manns BJ, Klarenbach SW, James MT, Ravani P, Pannu N, Himmelfarb J, Hemmelgarn BR: Comparison of the complexity of patients seen by different medical subspecialists in a universal health care system. JAMA Netw Open 1: e184852, 2018. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaya S, Yeboah H, Charles CH, Otu A, Labonte R: Ethnic and racial disparities in COVID-19-related deaths: Counting the trees, hiding the forest. BMJ Glob Health 5: e002913, 2020. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stutzin Donoso F: Chronic disease as risk multiplier for disadvantage. J Med Ethics 44: 371–375, 2018. 10.1136/medethics-2017-104321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willen SS, Knipper M, Abadía-Barrero CE, Davidovitch N: Syndemic vulnerability and the right to health. Lancet 389: 964–977, 2017. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30261-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe : Good maternal nutrition. The best start in life, 2016. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/313667/Good-maternal-nutrition-The-best-start-in-life.pdf?ua=1. Accessed October 5, 2020

- 11.Jan S, Laba TL, Essue BM, Gheorghe A, Muhunthan J, Engelgau M, Mahal A, Griffiths U, McIntyre D, Meng Q, Nugent R, Atun R: Action to address the household economic burden of non-communicable diseases. Lancet 391: 2047–2058, 2018. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30323-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, Danaei G, García-Saisó S, Salomon JA: Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: A systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet 392: 2203–2212, 2018. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31668-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishtar S, Niinistö S, Sirisena M, Vázquez T, Skvortsova V, Rubinstein A, Mogae FG, Mattila P, Ghazizadeh Hashemi SH, Kariuki S, Narro Robles J, Adewole IF, Sarr AD, Gan KY, Piukala SM, Al Owais ARBM, Hargan E, Alleyne G, Alwan A, Bernaert A, Bloomberg M, Dain K, Frieden T, Patel VH, Kennedy A, Kickbusch I; Commissioners of the WHO Independent High-Level Commission on NCDs: Time to deliver: Report of the WHO independent high-level commission on NCDs. Lancet 392: 245–252, 2018. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31258-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization : Saving lives, spending less: A strategic response to noncommunicable diseases, 2018. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272534. Accessed October 5, 2020

- 15.Taylor AL, Habibi R, Burci GL, Dagron S, Eccleston-Turner M, Gostin LO, Meier BM, Phelan A, Villarreal PA, Yamin AE, Chirwa D, Forman L, Ooms G, Sekalala S, Hoffman SJ: Solidarity in the wake of COVID-19: Reimagining the international health regulations. Lancet 396: 82–83, 2020. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31417-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]