Abstract

Despite declining rates over the past several decades, violence continues to be a pervasive public health problem. To date, we have very little knowledge about the factors at the outer layers of the social ecology that may serve to protect or exacerbate violence. The purpose of the present research is to identify community-level risk and protective correlates of multiple forms of violent crime. Official crime data were collected from 36 of the municipalities (92%) across the state of Rhode Island. Additionally, the research team identified 23 types of community establishments and identified the number of each for each of the 36 municipalities. Semipartial correlations were computed between the 23 community variables and each of nine types of violent crimes. While there were a number of significant results, only a few meaningful patterns were found. The number of transit stations was associated with all forms of sexual violence, sex trafficking, and general physical assault. Gun dealers were associated with domestic assault, child abuse, kidnapping, and assault with a weapon, but inversely related to sex trafficking. Boys and Girls Clubs were negatively associated with the number of assaults, assaults with a weapon, sexual assaults, sexual assaults on a child, sex trafficking, and kidnappings. Contrary to prior findings, the number of alcohol outlets was generally unrelated to violent crime. These findings must be interpreted with great caution given nature of the research design. However, this study provides an initial step to advance the research on community-level risk and protective factors for violence.

1. Introduction

Violence is a public health problem of global scale (Mercy et al., 2003). Prevention strategies focused at the outer levels of the social ecology have potential to reach a greater number of individuals thereby achieving greater population impact (Branas et al., 2011; Yen and Syme, 1999). Unfortunately, we have few evidence-based, outer layer prevention strategies for violence (Basile et al., 2016; David-Ferdon et al., 2016; Fortson et al., 2016; Niolon et al., 2017). This is partly due to the under-developed literature on risk and protective factors that exist beyond the individual and interpersonal layers of the social ecology. There is some evidence of community-level processes and characteristics that may give rise to violence such as residential instability or overcrowding, unemployment and concentrated poverty, and lack of positive relationships among residents (Basile et al., 2016; David-Ferdon et al., 2016; Fortson et al., 2016; Niolon et al., 2017). However, these processes are difficult to quantify and assess; and even more difficult to do so consistently across communities. Thus, knowledge about tangible structural components of communities, which may contribute to violence promotion or protective processes, may be informative to the development of community-level prevention strategies.

One structural community determinant that has been linked to violence is alcohol outlet density (AOD; e.g., Kearns et al., 2015). Generally, greater AOD in a community is associated with more violence in that community. This is not surprising given that AOD increases physical access to alcohol and risk of intoxication, a risk factor for violence (Duke et al., 2018). However, Resko et al. (2010) found AOD predicted adolescents’ violence, even after controlling for individual alcohol use, suggesting excess consumption alone does not explain the relationship between AOD and violence. Cunradi (2010) suggested AOD may represent a sign of neighborhood disorder and limited social control, which could decrease concern for consequences associated with violence and discourage others from intervening to prevent incidents. In other words, the physical attributes of a community may give rise to community norms, processes, and characteristics that potentiate violence. Conversely, some physical attributes may promote cultures that prevent violence. Community green spaces have shown to be protective against violence (Branas et al., 2011; Kuo, 2003). The presence of green spaces may promote social ties to the community and protect against norms that condone crime stemming from the visual appearance of neighborhood decay (e.g., Branas et al., 2011). Thus, developing prevention strategies pertaining to those community factors (e.g., reducing AOD, turning abandoned lots into green spaces), may effectively reduce violence.

Relatively few community structural determinants have been investigated in the literature on violence. And they have generally been examined in isolation from other structural determinants in that community. In the present study, we go beyond the typical community features to include a host of novel community attributes. We further explore their associations with violence while controlling for the association of the other structural determinants in the community. A study of this nature cannot demonstrate causal mechanisms. However, it may motivate future research that can provide insights on how to develop community-level prevention strategies and allocate the resources and research efforts to solve the violence problem.

2. Methods

2.1. Population density

Population density is the number of people per square mile. Population numbers for each municipality were taken from the 2010 Census. Land square mileage was obtained front official town websites on RI.gov.

2.2. Crime data

Violence data were collected from official incident records of police districts in the incorporated municipalities of Rhode Island. Police chiefs and/or administrative officials in charge of official crime records for all 39 Rhode Island municipalities were contacted to request official incident reports of all crimes occurring between November 25, 2015 and May 23, 2016. Three municipalities did not provide sufficient records for the present analysis. The final sample contained violent crime data from 36 municipalities.

Given our focus on violence, all nonviolent crimes (e.g., warrant issues, drug charges, etc.) were excluded from analysis. Data collection resulted in 27,888 charges of violent crimes. These do not all reflect distinct events as some incidents could have resulted in multiple charges. Crimes comprised 77 different specific criminal charges across the 36 municipalities comprising nine categories of violent crimes: 1) Homicide; 2) Assault; 3) Assault with a Weapon; 4) Domestic Assault; 5) Sexual Assault; 6) Sexual Assault on a Child; 7) Sex Trafficking; 8) Child Abuse and Neglect; and 9) Kidnapping. Supplement A provides details about the specific criminal charges aggregated beneath each outcome variable.

2.3. Community variables

The research team identified 23 types of establishments as possible community-level correlates of violence (see Table 1). Each variable was measured as a simple count of the number of those establishments in a municipality. The list of community variables derived from 1) existing research (e.g., Branas et al., 2011; Gardner and Brooks-Gunn, 2009; Kearns et al., 2015; Kuo, 2003), 2) community features hypothesized to promote collective efficacy and social cohesion (Wilkins et al., 2014), or 3) establishments that could promote norms condoning violence. Addresses were collected using online databases and browser searches. Data were collected from reliable resource lists and organizational databases affiliated with local services including United Way of Rhode Island, the state rape crisis center, town city and clerk’s offices, Providence City Hall’s license administrator, the Rhode Island GIS open access database (RIGIS), gun dealer directories, shelter guides, the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, the Department of Developmental Disabilities, local hospital records and administrators, healthgrades.com, and FindHelp211. Research staff reviewed and confirmed locations using comprehensive internet searches, phone calls, and travel to the address of the community site.

Table 1.

Semipartial correlations between community variables and violent crimes.

| Homicide | Assault | Assault with weapon | Domestic Assault | Sex assault | Sex assault on child | Sex trafficking | Child Abuse & Neglect | Kidnap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic violence resources | 0.16 | .35 b | .40 c | .34 b | 0.01 | .18 a | .24 c | .38 b | 0.15 |

| Family/child protective services | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.17 | −0.14 | .32 c | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.18 |

| Advocacy organizations | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −.16d | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −.32 b |

| Libraries | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.14 | −0.16 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.07 |

| Places of worship | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.13 |

| Outdoor recreation | −0.01 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −.17 a | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.12 |

| Boys & girls clubs | −0.01 | −.28 a | −.19d | −0.12 | −.23 a | −.30 c | −.16 a | −0.22 | −.21 a |

| YMCAs | −.27 a | −.24d | −0.13 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.10 | −.15 a | −0.12 | 0.04 |

| Grocery stores | 0.27 | −0.09 | −0.13 | −0.09 | −0.04 | —.17 a | −.14 a | −.17 | −0.20 |

| Gun dealers | −0.08 | 0.01 | .28 a | .36 b | −0.03 | 0.11 | −.15 a | .28 a | .21 a |

| Alcohol outlets | −.35a | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.17 |

| Strip clubs | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.07 | −.23 a | 0.13 | .14 a | 0.18 | −0.16 |

| Sex shops | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.03 | 0.00 | .33 c | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.05 | .34 c |

| Transit stations | 0.16 | .37b | −0.03 | −0.12 | .25 b | .19 a | .16 a | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Doctors’ Office / medical Services | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.09 | .20 a | .15 a | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Homeless shelters | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.12 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.18 |

| Hospitals | −0.01 | −.38 b | .23d | .43 c | −0.02 | −0.05 | −.17 a | 0.20 | .38 c |

| Pawn shops | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.04 | .24 b | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.03 | .31 c |

| Substance use treatment centers | 0.20 | −.21d | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.10 | −.20 a | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.10 |

| Fire stations | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.13 | −0.11 | 0.04 | −.16 d | −.12d | −.26d | −0.07 |

| Museums | 0.03 | −0.22 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.08 |

| Pain treatment centers | 0.00 | −0.15 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −.25 b | −0.09 | 0.07 | −0.03 | −.36 c |

| Food pantries | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.15 | −0.17 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.17 | 0.05 |

Note. Bolded numbers reflect significant findings;

= p < .05;

= p < .01;

= p < .005;

= p < .07.

3. Analysis

Evidence indicates population density is associated with violence (Browning et al., 2010; Christens and Speer, 2005; Harries, 2006; Regoeczi, 2002). We statistically removed the variance in violent crime outcomes associated with population density by regressing each violence outcome on the mean-centered population size (i.e., number of people) and mean-centered land square mileage of each municipality, as well as their interaction term. We saved the residuals from each of these regressions as new outcome variables. The residuals represent that variance in violence outcomes that is unrelated to population density. We next computed semi-partial correlations between each violence outcome residual and the 23 community variables. The semi-partial correlation analysis controls for nonorthogonality among the community variables and provides the variance in the violence outcome that is associated with one community variable above and beyond the other 22 community variables.

4. Results

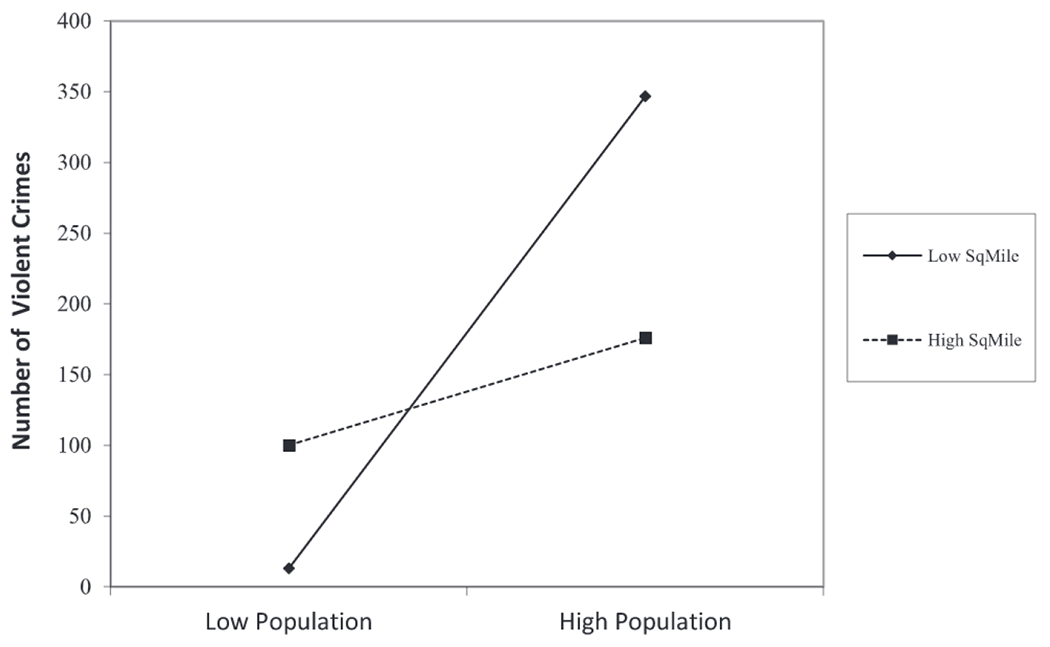

Fig. 1 illustrates the relationship among population rate, land square mileage, their interaction (i.e., population density), and violent crime. As the number of people per square mile increases the number of violent crimes increases.1

Fig. 1.

The effect of population density on violent crimes in Rhode Island. The interaction indicates that as the number of people per square mile of land increases so too does the number of violent crimes. Low Population reflects 1 standard deviation below mean population size (i.e., number of people); High Population reflects 1 standard deviation above the mean population size; Low SqMile reflects 1 standard deviation below the mean land square mileage; High SqMile reflects 1 standard deviation above the mean land square mileage.

Results of semi-partial correlation analysis are presented in Table 1. Generally, only four community variables demonstrated a pattern of association with violence. The number of domestic violence (DV) resources in a community correlated positively with six out of nine violent crime categories; the number of transit stations positively correlated with four out of nine violent crimes, including all types of sex offenses (sexual assault, sexual assault on a child, and sex trafficking); and the number of gun dealers correlated positively four of nine outcomes, but negatively correlated with sex trafficking. Notably, the number of Boys and Girls Clubs in a community was negatively associated with 5 of nine violence outcomes.

5. Discussion

Findings indicate that several community attributes were associated with a range of violent crimes. Contrary to previous research (e.g., Branas et al., 2011; Kearns et al., 2015), the number of alcohol outlets and green spaces/outdoor recreation sites were generally unrelated to violence. Alcohol outlets demonstrated a negative association with homicide while outdoor recreation was negatively associated with sexual assault. These may well be chance findings. It is not clear why AOD would be protective against violence given the well-established link between alcohol and violence (Duke et al., 2018). The number of DV resources was positively correlated with several violence outcomes, likely as a consequence of the amount violence in those areas. The number of gun dealers in a community was positively correlated with assaults with a weapon, domestic assaults, child abuse, and kidnapping. Conversely, it was negatively associated with sex trafficking. The mechanism through which the presence of gun dealers would dissuade sex trafficking is unclear. This could reflect a chance finding but additional research with more rigor is needed to understand these associations. Notably, transit stations were associated with all forms of sexual violence and sex trafficking as well as general physical assault. Connections to sex trafficking are to be expected given that transit stations may be used to transport victims and that these sites may also serve as places to sell sex to travelers. In fact, recent research using spatial clustering techniques found that sex trafficking was predicted by, among other variables, proximity to the interstate highway (Mletzko et al., 2018). Further exploration of how transit stations might contribute to other forms of violence is warranted.

Another pattern that emerged was the potential protective effect of Boys and Girls Clubs (BGCs), which were negatively associated with the number of assaults, assaults with a weapon, sexual assaults, sexual assaults on a child, sex trafficking, and kidnappings. This is somewhat consistent with the findings of Gardner and Brooks-Gunn (2009). These authors identified six types of youth-serving organizations and found that adolescents from communities with more types of organizations experienced less exposure to community violence. However, these authors did not assess the actual number of youth-serving organizations in the community as we did here. They simply examined how many different types of organizations were in the community, making it difficult to determine whether certain organizations are more relevant to violence than are others. In our study, only BGCs were negatively correlated with violence; this did not extend to the same degree to YMCAs, which also serve youth among other populations. It unclear whether these institutions have a true protective effect in their communities, or if they are a marker of some other community factor that protects against violence. Future research could explore the culture and practices of the BGCs and the characteristics of the communities that have such clubs to determine if a protective factor can be identified and replicated.

Our findings must be considered in the context of several important limitations. The study used a simple correlational design and analysis which, undeniably, precludes speculation about causal relationships. Additionally, we were not able account for incidents resulting in multiple violent charges in our data or violence that is never reported to the criminal system. Crimes included here are highly variable in the likelihood of being reported to police. Some crimes like homicide are surely more veridical than violent crimes that are domestic for example. It is unknown how this could affect results. Further, given the number of analyses and the small sample size, there are undoubtedly type 1 errors. Because of these factors, we strongly stress the limited interpretation that can be applied to these nascent findings. Nevertheless, this is the first analysis to look at so many of these community variables and to do so simultaneously.

An important next step that could remedy some of these limitations is the conduct of research that integrates spatial mapping and time of event using this expanded set of structural community predictors. This may elucidate how and why certain community determinants contribute to or prevent violence. For example, the present analysis suggested a protective association between BGCs and violence. This might be due to reduced opportunity for violence because youth are engaged in prosocial activities with adults instead of engaging in unmonitored social activities. Alternatively, it may be that the presence of pro-youth agencies in a community communicates positive norms about investment in youth which protect against violence. If violence reductions correspond with the operating hours for BGCs it would support the opportunity hypothesis. Alternatively, if a spatial relationship exists independent of time it could support the social norms hypothesis.

Despite the noteworthy limitations, this study provides an initial step to advance the research on community-level risk and protective factors for violence. This fills an important gap, since less is known about community and societal level factors - particularly protective factors - for different forms of violence compared to individual and relationship level factors (Basile et al., 2016; David-Ferdon et al., 2016; Fortson et al., 2016; Niolon et al., 2017). Additionally, it is the first study to use such a broad list of correlates while controlling for covariance among them. We believe this is the key strength of this research. It is our hope that other researchers will attempt to further investigate and expand the research on these community correlates in other data to help build the evidence base on community-level factors that can protect against violence.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Because of space constraints, we present a figure depicting results of the aggregate of all violent crimes.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106380.

References

- Basile KC, DeGue S, Jones K, Freire K, Dills J, Smith SG, Raiford JL, 2016. STOP SV: A Technical Package to Prevent Sexual Violence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Branas CC, Cheney RA, MacDonald JM, Tam VW, Jackson TD, Ten Have TR, 2011. A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. Am. J. Epidemiol 174 (11), 1296–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Byron RA, Calder CA, Krivo LJ, Kwan MP, Lee JY, Peterson RD, 2010. Commercial density, residential concentration, and crime: land use patterns and violence in neighborhood context. J. Res. Crime Delinq 47 (3), 329–357. [Google Scholar]

- Christens B, Speer PW, 2005. Predicting violent crime using urban and suburban densities. Behavior and Social Issues 14 (2), 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, 2010. Neighborhoods, alcohol outlets and intimate partner violence: Addressing research gaps in explanatory mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 7 (3), 799–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David-Ferdon C, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Dahlberg LL, Marshall KJ, Rainford N, Hall JE, 2016. A Comprehensive Technical Package for the Prevention of Youth Violence and Associated Risk Behaviors. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Duke AA, Smith KM, Oberleitner L, Westphal A, McKee SA, 2018. Alcohol, drugs, and violence: a meta-meta-analysis. Psychol. Violence 8 (2), 238. [Google Scholar]

- Fortson BL, Elevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, Alexander SP, 2016. Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect: A Technical Package for Policy, Norm, and Programmatic Activities. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, Brooks-Gunn J, 2009. Adolescents’ exposure to community violence: are community neighborhood youth organizations protective? J. Commun. Psychol 37 (4), 505–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries K, 2006. Property crimes and violence in United States: an analysis of the influence of population density. Int. J. Crim. Justice Sci 1, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns MC, Reidy DE, Valle LA, 2015. The role of alcohol policies in preventing intimate partner violence: a review of the literature. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 76, 21–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo FE, 2003. Social aspects of urban forestry: the role of arboriculture in a healthy social ecology. J. Arboric. 29 (3), 148–155 (29(3). [Google Scholar]

- Mercy JA, Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB, 2003. Violence and health: the United States in a global perspective. Am. J. Public Health 92, 256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mletzko D, Summers L, Arnio AN, 2018. Spatial patterns of urban sex trafficking. J. Crim. Just 58, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Niolon PH, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: A technical package of programs, policies, and practices. In: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Regoeczi WC, 2002. The impact of density: the importance of nonlinearity and selection on flight and fight responses. Social Forces 81 (2), 505–530. [Google Scholar]

- Resko SM, Walton MA, Bingham CR, Shope JT, Zimmerman M, Chermack ST, Cunningham RM, 2010. Alcohol availability and violence among inner-city adolescents: A multi-level analysis of the role of alcohol outlet density. American journal of community psychology 46 (3-4), 253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins N, Tsao B, Hertz M, Davis R, Elevens J, 2014. Connecting the dots: An overview of the links among multiple forms of violence. In: Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Oakland. Prevention Institute, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Yen IH, Syme SL, 1999. The social environment and health: a discussion of the epidemiologic literature. Annu. Rev. Public Health 20 (1), 287–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]