Abstract

The Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is an important cause of cervical lymphadenitis in children, and its incidence appears to be increasing in the United States and elsewhere. In areas where Mycobacterium tuberculosis is not prevalent, M. avium causes the vast majority of cases of mycobacterial lymphadenitis, although several other nontuberculous mycobacterial species have been reported as etiologic agents. This report describes the case of a child with cervical lymphadenitis caused by a nontuberculous mycobacterium that could not be identified using standard methods, including biochemical reactions and genetic probes. Direct 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing showed greater than 99% homology with Mycobacterium triplex, but sequence analysis of the 283-bp 16S-23S internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence showed only 95% identity, suggesting that it is a novel species or subspecies within a complex of organisms that includes M. triplex. Mycolic acid high-performance liquid chromatography analysis also identified this isolate as distinct from M. triplex, and differences in susceptibility to streptomycin and rifampin between this strain and M. triplex were also observed. These data support the value of further testing of clinical isolates that test negative with the MAC nucleic acid probes and suggest that standard methods used for the identification of mycobacteria may underestimate the complexity of the genus Mycobacterium. ITS sequence analysis may be useful in this setting because it is easy to perform and is able to distinguish closely related species and subspecies. This level of discrimination may have significant clinical ramifications, as closely related organisms may have different antibiotic susceptibility patterns.

The Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is an important cause of cervical lymphadenitis in children, and its incidence appears to be increasing in the United States and elsewhere. Surgical excision achieves a high cure rate, but complete excision is often not feasible. Antibiotic therapy may be of benefit in some cases (12, 13).

M. avium causes the vast majority of cases of lymphadenitis in these children, although several other nontuberculous mycobacterial species have been reported as etiologic agents, including M. bohemicum, M. celatum, M. genavense, M. haemophilum, M. heidelbergense, M. interjectum, M. intracellulare, M. lentiflavum, M. malmoense, and M. triplex (1, 6, 8–10, 12, 15, 19, 20). Species identification has generally been performed using biochemical tests and 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene sequence analysis. However, 16S rDNA sequence variability among selected mycobacterial species is limited. The 16S-23S rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) is transcribed, but it does not code for a functional product and therefore is not as highly conserved as 16S rDNA. This sequence heterogeneity may serve to differentiate mycobacterial species whose 16S rDNA sequences are closely related or identical.

Here we report the case of a child with cervical lymphadenitis due to a nontuberculous mycobacterium that could not be identified using standard methods: Direct 16S rDNA sequencing showed greater than 99% identity with M. triplex, but ITS sequence analysis suggests that it is a novel species or subspecies within a complex of organisms that includes M. triplex. M. triplex belongs to a group of slowly growing mycobacteria that resemble M. avium by conventional biochemical tests, but commercial nucleic acid probes designed to detect species of MAC are negative when tested against this group of organisms (6).

CASE REPORT

(This case was included in a previously reported study evaluating treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitis [12]).

A 4-year-old Caucasian girl was admitted to the hospital with a 1-week history of left preauricular erythematous swelling and a 1-day history of left submandibular swelling. Physical examination revealed a 2- by 2-cm warm, slightly tender left preauricular node and a 2.5- by 2.5-cm left submandibular node. She was treated with intravenous cefazolin with no response. She was taken to the operating room, where incision and drainage of the submandibular node and needle aspiration of the preauricular node were performed. An acid-fast stain of the material obtained was positive, and her antibiotics were switched to clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol. Over the next few months she had persistent drainage from the preauricular node, and both lesions developed an overlying violaceous hue. Rifampin was replaced by rifabutin. Five months after initial presentation, while on clarithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin, she developed left anterior cervical adenitis with an overlying violaceous hue. At this time her other lesions appeared to be healing. Surgical excision of anterior cervical nodes was performed, and clofazimine was added to her regimen. By 1 year, the older lesions had dried up, with scar tissue palpable on exam and a persistent overlying violaceous hue. Medications were then discontinued. Four years after initial presentation the patient's family reported that she had had no recurrences, that the preauricular area had healed completely, and that she was left with a faint scar in the cervical area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain.

The strain, designated RH 287, was isolated from a mycobacterial culture of the lymph node tissue of a child with lymphadenitis using standard methods at the Massachusetts State Tuberculosis Laboratory. Briefly, the specimen was decontaminated using the standard N-acetyl-l-cysteine and NaOH procedure followed by centrifugation. The sediment was then set up for growth on solid (Lowenstein-Jensen and Middlebrook 7H10) and liquid (MGIT; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) media. The positive culture was tested with a commercial MAC molecular probe (GenProbe, San Diego, Calif.).

Phenotypic analysis.

Biochemical tests were performed using standard methods (16). Susceptibility testing was performed using the proportion method on solid media and in liquid broth medium (BACTEC; BD Biosciences) (16). Mycolic acid analysis was performed at the mycobacteriology laboratory of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention according to established procedures (2). Briefly, whole cells of mycobacteria were saponified in methanolic potassium hydroxide solution and autoclaved for 1 h at 121°C. The saponified sample was acidified with concentrated HCl and water (1:1) and extracted from the aqueous solution with chloroform. The mycolic acids were derivatized to bromophenacyl esters with para-bromophenacyl-8 (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, Ill.). The derivatized sample was separated by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a C18 column using a gradient elution of methanol and methylene chloride (3). The chromatographic pattern generated by this method was matched to standard HPLC patterns of authentic species using relative retention time ratios for peaks calculated by the chromatographic software. The ratios were derived using a high-molecular-weight standard (Ribi ImmunoChem Research, Inc., Hamilton, Mont.) as the reference peak.

Genotypic analysis.

Cultures were inoculated from Lowenstein-Jensen slants into Middlebrook 7H9 medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.5% albumin. 0.085% NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 80. Liquid cultures were grown for 2 to 4 weeks. Mycobacterial DNA was isolated using N-cetyl-N,N,N-trimethylammonium bromide as described previously (21). For the ITS PCR, primers 16S (5′ TTGTACACACCGCCCGTCA) and 23S (5′ CGATGCCAAGGCATCCACC), as described previously (4), were used to amplify a 490-bp product from 2 to 5 μl (40 to 80 ng as estimated from ethidium bromide-stained gels) of each mycobacterial DNA sample using the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). This amplicon includes the entire ITS region and flanking 16S and 23S rDNA. PCRs were carried out in a total volume of 50 μl with 0.5 μM (each) primer, 250 μM (each) nucleotide, 5 μl of 10× buffer (with 15 mM MgCl2), and 0.5 μl of enzyme (3.5 U/μl). At least one negative control (sterile water) was included with each set of PCRs. PCR products were purified for sequencing using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.).

Sequencing was performed on ABI 373A and 377 automated DNA sequencers using Taq dye terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) at the core sequencing facility of the Children's Hospital Mental Retardation Research Center. The 16S primer was used for initial sequencing. If ambiguous bases were seen, the 23S primer was used for a sequencing reaction on the complementary strand to resolve the ambiguity. The sequence was compared to ITS DNA sequences in GenBank, and analysis was performed using Sequencher (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Mich.).

PCR amplification of 16S rDNA was done with oligonucleotides 5′ GAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG and 5′ AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA, as described previously (5, 17). Direct sequencing was performed on an ABI 373A sequencer. The sequence of 16S hypervariable region A was compared to 16S rDNA information in GenBank.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank nucleotide accession number of the 16S-23S ITS sequence of this isolate is AF-214587. The accession number of the M. triplex ITS sequence is AF334028.

RESULTS

The isolate grew as slightly yellow, smooth colonies within 24 days when incubated at 37°C. No growth was seen at 22 or 45°C. The isolate did not hybridize with the commercially available genetic probe for MAC (GenProbe). The results of susceptibility testing and biochemical reactions of this strain, compared to those of M. avium and M. triplex, are shown in Table 1. These results are consistent with this organism being similar to, yet distinct from, these species.

TABLE 1.

Biochemical analysis and drug susceptibility of strain RH 287 compared to those of M. avium and M. triplex

| Characteristic | Resultsa for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| RH 287 | M. avium (8) | M. triplex (6, 8) | |

| Pigmentation | Yellow | None | None |

| Growth at: | |||

| 22°C | − | + | − |

| 45°C | − | − | − |

| NaCl tolerance | − | − | − |

| Catalase at 68°C | + | ± | + |

| Tween hydrolysis | − | − | − |

| Urease | + | − | + |

| Niacin production | − | − | − |

| Nitrate reduction | − | − | + |

| Arylsulfatase (3 days) | − | − | − |

| Pyrazinamidase | − | ± | N/A |

| Susceptibility to: | |||

| Isoniazid (1 μg/ml) | R | R | R |

| Streptomycin (2 μg/ml) | S | R | R |

| Ethambutol (5 μg/ml) | R | R/S | R/S |

| Rifampin (1 μg/ml) | S | R/S | R |

R, resistant; S, susceptible; R/S, variable susceptibility; N/A, not available; ±, variable. References are in parentheses.

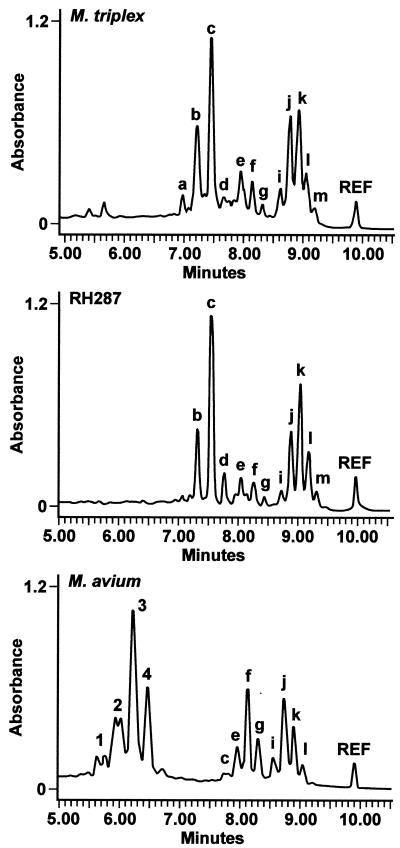

The HPLC mycolic acid pattern for this isolate was reported to be that of an unidentified mycobacterium species. The chromatographic pattern did not match that of any species described in the HPLC standard method manual but resembled that of a group of organisms designated SAV by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2). The SAV organisms are mycobacteria which exhibit mycolic acid patterns similar to those of M. simiae, M. lentiflavum, and M. triplex but which biochemically are consistent with the M. avium complex (6). Among these species, the HPLC pattern of this isolate most closely resembled that of M. triplex (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of HPLC chromatogram of RH 287 to those of M. triplex and M. avium.

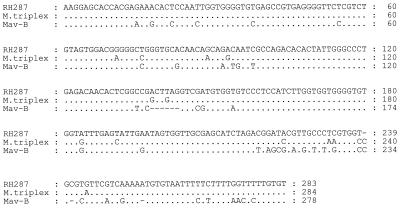

Because the biochemical and HPLC results were not definitive, genotypic testing was done. Examination of the 142 bp of 16S rDNA hypervariable region A of the isolate we studied revealed a 99.6% similarity to that of M. triplex (6). However, the 283-bp ITS sequence of this strain was unique, showing 95% identity with the ITS region of the M. triplex type strain, which is 100% identical to the one other reported M. triplex ITS sequence (18). The ITS sequence of this isolate showed 81% similarity to the most common M. avium ITS sequence, which has been designated the Mav-B sequevar (Fig. 2) (11).

FIG. 2.

16S-23S ITS sequence alignment of RH 287, M. triplex, and M. avium Mav-B.

DISCUSSION

Standard biochemical and molecular probe analysis could not assign isolate RH 287 to a known mycobacterial species. The probe for MAC was negative, and the biochemical tests, while similar to those for M. avium and M. triplex, were not definitive, with the most obvious differences being the presence of pigmentation and susceptibility to streptomycin and rifampin. The HPLC mycolic acid pattern and 16S rDNA sequence for this isolate most closely resembled those of M. triplex. Most mycobacterial species show a unique signature sequence in hypervariable region A within the 16S ribosomal gene; however, M. kansasii and M. gastri have identical 16S rDNA sequences, as do M. ulcerans and M. marinum. In addition, members of the M. tuberculosis complex have identical 16S rDNA sequences (14).

Because of the high degree of sequence similarity of the 16S rDNA genes of several mycobacterial species, further sequence analysis of the 16S-23S ITS region was performed. These results revealed a level of difference similar to that between species within the MAC. For example, the ITS sequence of the most common M. avium sequevar, Mav-B, differs by 6% from that of M. intracellulare sequevar Min-A and by between 5 and 11% from those of various sequevars of a third group of MAC strains (7). A study comparing the ITS sequences of 17 mycobacterial species revealed that the lowest level of ITS sequence divergence between any two species is 4%, which represents a 13-nucleotide difference between the ITS sequence of M. triplex and that of M. genavense (18). Therefore, the 5% difference between the ITS sequence of RH 287 and that of M. triplex, combined with the results of biochemical and mycolic acid testing, indicates that this strain represents a unique species or subspecies within a complex of organisms that includes M. triplex. Although the ITS sequences of the M. triplex type strain and the other reported M. triplex isolate are identical, because few isolates of this species have been studied, it remains possible that there is a range of variation in M. triplex ITS sequences that will link this species to the novel isolate described in this report.

As demonstrated in this study, standard biochemical testing used for the identification of mycobacteria may underestimate the complexity of the genus Mycobacterium. Our data support the importance of further testing of clinical isolates that test negative to the MAC probe. In the clinical setting, obtaining reliable susceptibility data is paramount, but studies to identify the organism may be valuable as well. ITS sequence analysis may be beneficial in this setting because it is rapid and easy to perform and is able to distinguish closely related species and subspecies. This type of analysis may prove to have important clinical ramifications, as closely related organisms may have different antibiotic susceptibility patterns. For example, the isolate we studied was susceptible to streptomycin and rifampin, whereas M. triplex is resistant to these two drugs (6, 8).

The majority of cases of MAC lymphadenitis are caused by M. avium isolates belonging to the Mav-B sequevar (11). The isolate we describe here must be added to a long list of organisms similar to M. avium that have been identified as causes of lymphadenitis in children (1, 6, 8–10, 12, 15, 19, 20). Important questions regarding the epidemiology and pathogenesis of disease caused by these organisms remain to be answered. It is unknown, for example, whether these species share virulence mechanisms with M. avium that allow them to cause similar clinical disease. It is also unknown whether the higher frequency of isolation of M. avium in this setting is because this species is more virulent than others or because it is more prevalent in the environment to which these children are exposed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

R.H. was supported by the Warren-Whitman-Richardson Fellowship of Harvard Medical School and a National Institutes of Health training grant (T32AI-07061-22).

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong K, James R, Dawson D, Francis P, Masters B. Mycobacterium haemophilum causing perihilar or cervical lymphadenitis in healthy children. J Pediatr. 1992;121:202–205. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler W, Floyd M, Silcox V, Cage G, Desmond E, Duffey P, Guthertz L, Gross W, Jost K, Ramos L, Thibert L, Warren N. Standard method for HPLC identification of mycobacteria. Washington, D.C.: Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler W, Jost K, Kilburn J. Identification of mycobacteria by high performance liquid chromatography. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2468–2472. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2468-2472.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Smet K, Brown I, Yates M, Ivanyi J. Ribosomal internal transcribed spacer sequences are identical among Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex isolates from AIDS patients, but vary among isolates from elderly pulmonary disease patients. Microbiology. 1995;141:2739–2747. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-10-2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards U, Rogall T, Blocker H, Emde M, Bottger E. Isolation and direct sequencing of entire genes. Characterization of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:7843–7853. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.19.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Floyd M, Guthertz L, Silcox V, Duffey P, Jang Y, Desmond E, Crawford J, Butler W. Characterization of an SAV organism and proposal of Mycobacterium triplex sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2963–2967. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2963-2967.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frothingham R, Wilson K. Sequence-based differentiation of strains in the Mycobacterium avium complex. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2818–2825. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2818-2825.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas W, Butler W R, Kirschner P, Plikaytis B B, Coyle M B, Amthor B, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J, Salfinger M, Crawford J T, Bottger E C, Bremer H J. A new agent of mycobacterial lymphadenitis in children: Mycobacterium heidelbergense sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3203–3209. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3203-3209.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haase G, Kentrup H, Skopnik H, Springer B, Bottger E. Mycobacterium lentiflavum: an etiologic agent of cervical lymphadenitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1245–1246. doi: 10.1086/516958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haase G, Skopnik H, Batge S, Bottger E. Cervical lymphadenitis caused by Mycobacterium celatum. Lancet. 1994;344:1020–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91680-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazra R, Lee S-H, Maslow J, Husson R. Related strains of Mycobacterium avium cause disease in children with AIDS and in children with lymphadenitis. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1298–1303. doi: 10.1086/315378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hazra R, Robson C, Perez-Atayde A, Husson R. Lymphadenitis due to nontuberculous mycobacteria in children: presentation and response to therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:123–129. doi: 10.1086/515091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inderlied C, Kemper C, Bermudez L. The Mycobacterium avium complex. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:266–310. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirschner P, Springer B, Vogel U, Meier A, Wrede A, Kiekenbeck M, Bange F-C, Bottger E. Genotypic identification of mycobacteria by nucleic acid sequence determination: report of a 2-year experience in a clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2882–2889. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2882-2889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberek V, Soravia C, Ninet B, Hirschel B, Siegrist C-A. Cervical lymphadenitis caused by Mycobacterium genavense in a healthy child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:269–270. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199603000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nolte F, Metchock B. Mycobacterium. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 400–437. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogall T, Wolters J, Flohr T, Bottger E. Towards a phylogeny and definition of species at the molecular level within the genus Mycobacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:323–330. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-4-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth A, Fischer M, Hamid M, Michalke S, Ludwig W, Mauch H. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S–23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:139–147. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.139-147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Springer B, Kirschner P, Rost-Meyer G, Schroder K-H, Kroppenstedt R, Bottger E. Mycobacterium interjectum, a new species isolated from a patient with chronic lymphadenitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3083–3089. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3083-3089.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tortoli E, Bartoloni A, Manfrin V, Mantella A, Scarparo C, Bottger E. Cervical lymphadenitis due to Mycobacterium bohemicum. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:210–211. doi: 10.1086/313600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Soolingen D, Hermans P W M, de Haas P, Soll D R, van Embden J. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2578-2586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]