Abstract

Background

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments have implemented preventive measures towards reducing infections. These conditions can affect the mental health of children and adolescents; however, this has not yet been fully explored.

Objective

The aim of the study was to analyze changes in symptomatology and positive emotions in Argentine children and adolescents since the onset of isolation, based on parent/caregiver report. We analyzed differences based on gender, age, socioeconomic status (SS) and containment measure (and their interactions); their associations with symptomatology and positive affect of parents/caregivers; and the moderating effects of sociodemographic factors on these associations.

Method

A total of 1205 caregivers responded to a survey regarding the mental health of children and adolescents under their care. They also completed a set of anxiety, depression, and affect measures about themselves.

Results

A considerable proportion of parents/caregivers perceived changes in their children’s and adolescents’ mental health compared to before the pandemic. Increased levels of anxiety-depression, aggression-irritability, impulsivity-inattention, and dependence-withdrawal were reported, as well as alterations in sleeping and eating habits, and a reduction in positive affect. Differences were observed according to their age and containment measure. Finally, we found correlations between parents/caregivers’ symptomatology and that reported about their children or adolescents. Gender, age and SS moderated some of these relationships.

Conclusions

Continued monitoring of child and adolescent mental health is a fundamental necessity. We recommend the implementation of early intervention strategies to prevent the escalation of serious mental health problems, particularly in those groups that have been most adversely affected since the onset of the pandemic.

Keywords: Mental health, Children, Adolescents, COVID-19

Introduction

On March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) claimed that the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus could be characterized as a pandemic. As a consequence, several governments around the world implemented a number of containment measures against the disease, such as school closures, social distancing and/or quarantine at home (Loades et al., 2020). In Argentina, the national government decreed a highly strict isolation (phase 1) on March 20, in terms of reducing social mobility throughout the territory until April 12 (Decree 297/ 2020). Only minimum mobility was allowed, in order to obtain food, medicinal products and cleaning supplies, with the exception of those people who worked in activities and services declared essential. Cultural, recreational and sports events, and face-to-face classes in all levels of education were suspended in order to avoid attendance and agglomeration of people. Later on, depending on the sanitary situation in each area, different phases started being implemented to gradually allow greater mobility, but maintaining the suspension of activities which promote the agglomeration of people.

It has been shown that pandemics can have an impact on child health beyond the effects of infection through behavioral, environmental, and socioeconomic pathways (Fan et al., 2021). Particularly, children and adolescents’ mental health can be affected by these measures. Distancing from relatives, peers and teachers, routine changes, less physical exercise and outdoor activities, and greater exposure to screens, can compromise their emotional well-being (Urbina-García, 2020; Xiang et al., 2020). Also, the pandemic context brings a heightened risk for problematics such as child maltreatment (Lee et al., 2021) and malnutrition (Zemrani et al., 2021); as well as study problems (Wang et al., 2021a, b) and—especially for adolescents—concerns regarding graduation and learning (Duan et al., 2020), family health, finances and personal projects for the future (Van de Groep et al., 2020). In these contexts, children and adolescents tend to develop feelings of sadness, anger, frustration and boredom, symptoms of anxiety and depression, sleeping and eating disorders, as well as disruptive behaviors (Brooks et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020).

Specifically in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of studies regarding the mental health of children and adolescents have been carried out in different countries. Cross-sectional studies have reported a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression, among which feelings of loneliness, sadness, hopelessness, loss of interest, unwillingness, boredom, low energy, loss of appetite, nervousness, worry, distress and fear stood out (García de Avila et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Orgilés et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020; Rosen et al., 2020; Saurabh & Ranjan, 2020; Xie et al., 2020; Zhou et al.; 2020). At the same time, symptoms of regression and greater dependence were found, such as clinginess, not sleeping alone, worsening of vocabulary and enuresis (Jiao et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020). In addition, symptoms of hyperactivity and inattention, such as restlessness, distraction and concentration difficulties, have been identified (Cusinato et al., 2020; Jiao et al., 2020; Orgilés et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020); as well as symptoms related to behaviors linked to aggression-irritability such as disobedience, excessive demands on parents and/or caregivers and sudden mood swings (Jiao et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020). Finally, other studies registered changes in sleeping and eating habits: children and adolescents had sleeping problems (Di Giorgio et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020); they slept more hours than usual, and ate more (Orgilés et al., 2020).

Also, longitudinal studies that examined within-person changes from before to during the COVID pandemic found significant increases in mental health symptoms, and a worsening of individual and family general well-being. For example, Hussong et al. (2021) observed increases in overall mental health symptoms in young adolescents, not fully attributable to developmental processes. In the same line, Feinberg et al. (2021) found changes with large effect sizes for externalizing (d = 1.59) and internalizing problems (d = 1.31); in this study, the proportion of children rated in the clinical range increased by 2.5 in internalizing problems, and by 4 in externalizing problems, in comparison to pre-pandemic levels.

On the other hand, some studies have reported positive effects, by identifying an increase in behaviors oriented towards keeping a routine, performing prosocial activities, bonding affectively and reflecting upon valuing social life (Romero et al., 2020). Another study (Van de Groep et al., 2020) found that during lockdown adolescents showed improved social-cognitive perspective-taking and vigor, and this yielded a willingness to benefit others, with a high sensitivity to need and deservedness. Furthermore, Tang et al. (2021) found that children and adolescents perceived benefits from home quarantine, leading to less psychological distress and higher life satisfaction; 21.4% of their sample reported being more satisfied with their lives during the pandemic than before. However, another study investigated changes in positive emotions since the beginning of the pandemic, and parents reported that their children looked less calm and reflective than before (Pisano et al., 2020).

Although previous studies have revealed the presence of psychopathological indicators in children and adolescents during the pandemic (Racine et al., 2020), many of these studies have not analyzed different dimensions of symptomatology in the same sample with a wide age range, and few have additionally studied changes in positive emotions. Thus more studies are still needed to contribute to a more solid and precise knowledge of the pandemics effects and scope. In this regard, the research question is: did parents and caregivers observe changes (increases, decreases) in the symptoms and positive emotions of children and adolescents since the isolation by COVID-19 began? Accordingly, the first objective of this work was to analyze the existence of changes in clinical symptomatology and positive emotions in children and adolescents aged 3–18 years old, as reported by their parents and caregivers, since the beginning of isolation. It was expected for parents and caregivers to report an increase in clinical symptomatology and a decrease in positive emotions since restraint measures were initiated (Hypothesis 1).

Secondly, sociodemographic factors such as gender, age or socioeconomic status (SS) have shown a modulating role on child psychopathology. For example, it is more common for girls to have internalizing symptoms, while boys exhibit more externalizing problems (Flores et al., 2020). This may be due, among other factors, to different developmental patterns, and interaction with parents, environment, culture and family education (Navarro-Pardo et al., 2012). Also, it is more common for young children to present more impulsivity-inattention symptoms, and adolescents to have more anxiety-depression symptoms and less positive affect (e.g., Park et al., 2014; Griffith et al., 2021). This is probably linked to the evolutionary stages of development (Baeyens et al., 2005) which results in less self-control and various physical, psychological, social and hormonal changes during puberty (Áláez Fernández et al., 2000). In fact, certain specific groups tend to present more symptoms than others. For example, in early childhood boys have presented higher levels of behavioral problems than do girls (Owens, 2016), and adolescent girls higher levels of depression than boys (Keenan & Hipwell, 2005). Regarding SS, studies have shown that lower SS is associated with unfavorable mental health among children and adolescents (e.g.; Aber et al., 2000; Nagy-Pénzes et al., 2020). It has been proposed that SS predicts access to resources, which in turn may influence mental health (Mackenbach, 2012).

In the context of the pandemic, previous studies have also analyzed the role of these sociodemographic factors in the clinical symptomatology of children and adolescents. Regarding gender, while some studies have found no effects on psychopathological variables (i.e. Domínguez-Álvarez et al., 2020; García de Avila et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020), others reported that women exhibited a greater number of symptoms specially in anxiety and depression (i.e., Duan et al. 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Oosterhoff et al., 2020; Zhou, et al., 2020), and that young boys showed a higher risk of oppositional-defiant and aggressive problems (Schmidt et al., 2021). Regarding age, some studies found no differences (i.e., Garcia de Avila et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Oosterhoff et al., 2020), while others found differences depending on the type of symptoms. For example, some studies reported that children from 3 to 6 years old showed a greater number of behavior problems and hyperactive behaviors (Domíguez-Álvarez et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Romero et al., 2020), clinginess and fear of contagion within family members (Jiao et al., 2020), while older children and adolescents had more symptoms of anxiety and depression (Liang, et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020), as well as inattentive behaviors (Jiao et al., 2020). Concerning SS, lower SS and higher perceived economic impact have been associated with a higher number of symptoms (Domínguez-Álvarez et al., 2020; Oosterhoff et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020; Saurabh & Ranjan, 2020; Zhou et al., 2020) although other studies found no association between SS and mental health (Dong et al., 2020; Spinelli et al., 2020). Additionally, some studies have found that children who were allowed to walk within the framework of the containment measures presented lower levels of symptomatology (Orgilés et al., 2020) while others showed no effect of containment measures (Jiao et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020).

Taking the above into account, the research question was: did changes in symptomatology and positive emotions observed by parents and caregivers during the current pandemic context vary according to the aforementioned sociodemographic factors and/or according to their possible interaction? Therefore, the second objective of this work was to analyze whether changes in symptomatology and positive emotions of children and adolescents in the context of the pandemic, as reported by parents and caregivers varied as a function of gender, age, SS, and containment measure. We also aimed to analyze whether these factors interact with each other to explain changes in clinical symptomatology and positive emotions in specific groups. Symptoms and positive emotions were expected to vary according to sociodemographic factors and their interaction (Hypothesis 2). Specifically, girls were expected to have more symptoms of anxiety and depression than boys, and boys were expected to have more symptoms of impulsivity, aggressiveness, and irritability than girls (Hypothesis 2.1). Young children were expected to have more symptoms of impulsivity, inattention, and regression than adolescents, whereas adolescents were expected to have more symptoms of anxiety and depression, and less positive affect than young children (Hypothesis 2.2). For SS, children and adolescents from families with lower SS were expected to present more symptoms (Hypothesis 2.3). Children and adolescents who were in the distancing phase were expected to present fewer symptoms and more positive emotions than those who remained in strict isolation (Hypothesis 2.4). Regarding the interaction effects, it was expected that (a) adolescent girls would present more symptoms of anxiety and depression than the rest of the groups, and that (b) young boys would present more symptoms of impulsivity and inattention than the rest of the groups (Hypothesis 2.5).

Third, an association between symptoms and emotions in parents and caregivers with symptoms and emotions of their children and adolescents has been documented (e.g., Phares et al., 2009; Van Der Bruggen et al., 2008 ); possibly due to genetic factors, but also due to mutual influence and daily interactions (Phares & Compas, 1992). Children’s well-being in adverse situations is influenced by the levels of distress experienced by parents (Morris et al., 2012). Although the evidence is still limited, some studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic have reported that parents’ and caregivers’ concerns and fears about the pandemic, as well as their symptoms of anxiety, distress and depression are related to the presence of a greater number of symptoms in children and adolescents in their care (Domínguez- Álvarez et al., 2020; Orgilés et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020; Rosen et al., 2020; Yeasmin et al., 2020). However, a broader range of symptoms could be analyzed and positive emotions could be included. We therefore raised the following research problem: Was there a relationship between parents’ and caregivers’ symptomatology, positive emotions and concerns about the pandemic with their children’s and adolescents’ symptomatology and positive emotions? Thus, the third aim of this study was to analyze whether parents’ and caregivers’ symptomatology and positive emotions were associated with children’s and adolescents’ symptomatology and positive affect. It was expected that parents’ and caregivers’ symptomatology and positive affect would be associated with children’s and adolescents’ symptomatology and positive emotions (Hypothesis 3). Specifically, we expected that greater symptomatology in parents and caregivers to be associated with greater symptomatology and lower positive affect in children and adolescents (Hypothesis 3.1). In turn, we expected that higher positive affect in parents and caregivers would be related to fewer symptoms and greater positive emotions in children and adolescents (Hypothesis 3.2).

Fourth, it has been previously reported that relationships between parental and child mental health may vary as a function of sociodemographic factors, such as age, gender, or family SS (Rutter et al., 2003; Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al., 2007, 2008). For example, the relationship between parental depressive symptoms and the same symptoms in children has been reported to be stronger in boys than in girls (Watson et al., 2012) with boys being more affected by their parents’ symptoms. It has also been shown that the associations between parents and caregivers symptomatology and that of children becomes stronger in older children and adolescents because parents and children influence one another, but this becomes more evident over the years (Connell & Goodman, 2002). Finally, it has been reported that parents of higher SS are more capable of adapting their behavior to their children’s needs than parents of lower SS (Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al., 2007), and concerning containment measures, it has been reported that adults, children and adolescents in strict isolation presented higher levels of symptomatology than those in less strict circumstances (Jassim et al., 2021; Orgilés et al., 2020). Regarding the pandemic context, one study analyzed the moderation effect of sociodemographic factors on some of these relations. Romero et al. (2020) found a moderation effect of age, in the sense that parenting distress affected child prosocial involvement but only for older children. They did not find a moderation effect of gender. Therefore, the research question was: did parent–child mental health relations in the current pandemic context vary by gender, age, SS and containment measure? The fourth objective was to analyze whether these relationships vary according to gender, age, SS and containment measure. Sociodemographic factors were expected to moderate some of these relationships (Hypothesis 4). We expected that these relationships would be stronger for boys than for girls (for depressive symptoms; Hypothesis 4.1); and for older children and adolescents than for younger children (Hypothesis 4.2). Regarding SS, these relations were expected to be stronger in children and adolescents of lower SS families than in higher SS families (Hypothesis 4.3); and among children and adolescents who were in strict isolation compared with those who were in distancing phase (Hypothesis 4.4).

In summary the current literature provides evidence of the effects that the COVID-19 pandemic is having on the mental health of children and adolescents, as well as its variability according to sociodemographic and family factors. Nonetheless, no study on the subject has been carried out in Argentina. Likewise, only a limited number of studies have included different dimensions of mental health and positive effects. Furthermore, few studies have covered the effect of adults’ emotional state on the children and adolescents in their care (i.e., Rosen et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020; Orgilés et al., 2020; Domínguez-Álvarez et al., 2020), and no study has analyzed whether this relationship is moderated by sociodemographic factors. This study aimed to analyze changes in symptomatology and positive emotions in Argentinian children and adolescents since the onset of isolation; its variability according to gender, age, SS and containment measure (and their interactions); its associations with symptomatology and positive affect of parents and caregivers; and the moderating effects of sociodemographic factors on those associations. We expected to obtain information in order to detect at-risk groups and vulnerable families, and to provide evidence-based effective guidelines for the development and implementation of programs that promote the well-being of children and adolescents. The evidence provided here could result in useful resources for the current situation, and for possible future outbreaks.

Method

Design and Participants

A cross-sectional study was carried out. A total of 1205 parents and caregivers responded to an online survey that inquired about the mental health of their children and adolescents. As in other studies conducted in contexts of isolation (Romero et al., 2020; Spinelli et al., 2020), we decided to have primary caregivers respond about their children’s mental health. This was due to multiple reasons: the wide age range (children and adolescents between 3 and 18 years old), the need to compare different age groups, and the need to eliminate the problems in data analysis that arise when comparing different forms of measurement (self-reports and informants reports). Related to this, evidence suggests that self- and informant-reports may each provide valid indices of an individual’s emotional response tendencies, but predict different aspects of those tendencies (Lieberman et al., 2016). In addition to that, parents and caregivers are reliable and valid informants (e.g., Fendrich et al., 1991), the hetero-report is an accepted and widely used method by the scientific community (e.g., Cusinato et al., 2020), and it is more feasible for parents and caregivers to respond about their children and adolescents in an isolation context (without the possibility of face-to-face interviews).

The information was provided mainly by mothers (82.9%), then fathers (10.9%) and, to a lesser extent, by other family members (grandparents 2.2%, siblings 1.7%, uncles/aunts 1.5%, parents’ partners 0.8%). Each adult responded for only one of the children or adolescents in his or her care. Information was obtained for 1205 children and adolescents from 3 to 18 years old, out of which 574 (47.5%) were girls, 624 (51.8%) were boys and 9 children (0.7%) were identified with a different gender by their parents. The children and adolescents were distributed into 5 age groups according to different schooling cycles and ages: 19.3% belonged to kindergarten (3–5 years); 23.8% were in the first cycle of primary school (6–8 years); 24.7% were in the second cycle of primary school (9–11 years); 17.8% were in the basic cycle of secondary education (12–14 years) and 14.4% belonged to the oriented cycle of secondary education (15–18 years). Regarding containment measures, 27.5% were in strict isolation at the time of data collection, while 72.5% were in the social distancing phase. Finally, 60.7% attended private management schools and 39.3% attended public management schools. Information about the SS of 832 of them was gathered; 12.25% belonged to families with medium SS, 42.42% to a medium-high SS and 45.31% to a high SS. Families with a low or medium-low SS were not identified in the sample.

Instruments

Psychopathological Symptoms in Children and Adolescents

A selection of items from the parent report form of the CBCL and CBCL 1½–5 was made, in their Argentinian adaptations (Samaniego, 2008; Vázquez & Samaniego, 2017). The items selected were the ones that were more closely related to the current situation and that belonged to the subscales of the symptoms that had greater prevalence in the pandemic context according to the literature reviewed: anxiety and depression, withdrawal, aggressiveness, attention problems and items related to sleep and eating difficulties.

In order to assess how the isolation and social distancing measures affected the behavior of children and adolescents, caregivers scored the items comparing each conduct to the usual behavior prior to the pandemic using a Likert-type scale of three options (1 = less, 2 = the same or I have never seen this behavior-, 3 = more), similar to other studies (e.g., Orgilés et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020). Preliminary analyses were carried out to verify the validity of the scale adaptation. We performed an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) through a parallel analysis with optimal implementation. The EFA suggested retaining two factors that explained 43% of the variance. The factors were extracted using the unweight least squares (ULS) method, and a Promax rotation was applied. Factor loads were greater than 0.30 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). We then tested different models using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The model that presented the best fit (X2(204) = 693.65; p < 0.01; NFI = 0.98; NNFI 0.99; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.05) was a hierarchical model of four first order factors and two second order factors. First order factors were named as follows: anxiety-depression (α = 0.64; e.g., “Cries a lot”, “Unhappy, sad, or depressed”), dependence-withdrawal (α = 0.64; e.g., “Acts too young for his/her age”, “Clings to adults or too dependent”), aggression-irritability (α = 0.81; e.g., “Argues a lot”, “Temper tantrums or hot temper”) and impulsivity- inattention (α = 0.63; e.g., “Can’t sit still, restless, or hyperactive”, “Inattentive or easily distracted”). Items related to sleep and eating difficulties were retained, but considered in a separate way as additional items (not included in any subscale).

Positive Affect

The Positive Affect subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) for Children was administered (Laurent et al., 1999), in its Argentinian adaptation (Schulz Begle et al., 2009). The subscale includes items such as happiness, tranquility, and joy. To assess the changes in these emotions since the beginning of the isolation period, a Likert-type scale of five options was used (from 1 = has a lot less, to 5 = has a lot more). The psychometric properties (internal, convergent, and concurrent validity and reliability) of the adapted version for Argentinian children were adequate (Schulz Begle et al., 2009).

Anxiety Symptoms in Parents and Caregivers

The state anxiety subscale of the Spanish adaptation of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger et al., 1970; Spielberger et al., 1999) was used. This subscale is a self-report measure that consists of 20 items that assess anxiety as a state (transitory condition). Each item is answered in 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = nothing to 3 = a lot. Example items are “I am concerned now about possible future misfortune” or “I feel distressed”. This instrument has shown satisfactory levels of internal consistency α = 0.84–0.93 (Riquelme & Buela-Casal, 2011).

Depression Symptoms in Parents and Caregivers

The Spanish adaptation (Sanz et al., 2005; Sánz & Vázquez, 2011) of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) was used. The BDI-II is a self-report measure that assesses the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. It consists of 21 items that indicate symptoms such as sadness, frequent crying, guilt, pessimism, among others. The respondents have to choose one out of four statements (0–3) that represent increasing levels of severity of that symptom (e.g., [0] “I don’t cry any more than I used to”, [1] “I cry more than I used to”, [2] “I cry over every little thing”, [3] “I feel like crying but I can’t”), and they are asked to consider how they felt during the past two weeks. The BDI-II has adequate reliability (α = 0.89, Sanz et al., 2003) and validity (Beltrán et al., 2012; Sanz & Vázquez, 1998).

Affectivity of Parents and Caregivers

The Spanish adaptation (López-Gómez et al., 2015) of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) was used. The PANAS includes two subscales, Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect (NA). Each subscale consists of 10 items that express affects such as “active”, “nervous”, or “ashamed”. Respondents have to indicate to what extent they feel each one on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = not at all or very slightly to 5 = very much). The internal consistency of the test ranged from α = 0.83 to 0.92 (López-Gómez et al., 2015).

Concerns of Parents and Caregivers About the Situation

Five ad-hoc items were designed to assess the degree of people’s concern and worry about different situations related to the pandemic. Participants were asked how concerned they were about issues such as “the economic impact of the pandemic on my household”, “the emotional impact of the situation in my children”, “having to do homework with my children” or “changes in my social life and that of my family members”. People responded on a 4-point scale (from 1 = I am not concerned to 4 = I am very concerned) with an additional response option for those to whom the situation did not apply (“this situation does not apply to me”).

Sociodemographic Variables Related to Gender, Age and SS of the Families

Close ended questions were used to explore children’s gender and age, and parents’ and caregivers’ educational level and occupation type. Educational level was classified according to a scale based on the Argentinian education system (Pascual et al., 1993) and the occupational level was classified according to the Occupational Prestige Scale EGO 70 (Sautú, 1989), also created for the Argentinian context. SS was calculated using the Hollingshead Index of Socioeconomic Status (2011) which is adequate for our region (Pascual et al., 1993).

Procedure and Ethical Considerations

This study is part of a major longitudinal study regarding mental health in general population (Canet-Juric et al., 2020) in which a social media survey in three times was distributed. Particularly in time 2, most participants who have children and adolescents in their care reported concerns about their mental health; therefore the initial research objective (mental health in adults, Canet-Juric et al., 2020) was extended by inviting these caregivers and parents to respond to an online survey on the mental health of their children and adolescents. Additionally, this survey remained open and available online and different people accessed it through social networks.

The survey took place during June 2020 (between the 5th and the 28th of that month). By this moment, a social distancing regime with sanitary protocols was initiated in most of the Argentinian territory, where the viral circulation was minimal (phase 4); while the rest of the territory—mainly the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area—continued under an isolation regime (phase 3). The difference between both regimes is that distancing allows the gradual opening of commercial activities and permissions for outdoor recreation without time or distance restrictions. In both cases, attendance at educational institutions, public shows and places of entertainment behind closed doors (restaurants, cinemas, and theaters) were prohibited.

A proportion of these parents and/or caregivers had previously responded to the first survey (n = 832) of the major longitudinal study which included questions about their SS (between March 22 and March 25); to the second one (n = 627) which inquired about their concerns over the pandemic situation (between April 3 and 9, when the entire national territory was under mandatory strict isolation (phase 1); and to the third one (n = 632), which contained questions about their own affective responses (between May 6 and 31), when most of the national territory went into a social distancing regime which allowed people to leave their homes (phase 4) and another part of the territory was still under isolation (phase 3).

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles for research with human subjects recommended by the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013), as well as the ethical guidelines for research with human participants of the American Psychological Association (2010). Participation was voluntary and informed consent of the participants was mandatory. They were informed that they could interrupt their participation and abandon the study at any time without negative consequences of any kind. Contact information of the research group was also provided in order to clarify doubts that may arise in relation to the care of rights in research contexts. All study protocols were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the National University of XXX.

Data Analysis Plan

Descriptive analyses were done calculating the mean, standard deviations, range, minimum, maximum, skewness and kurtosis of the variables under study. A correlation analysis was also performed, using Pearson’s coefficient r among all variables. A descriptive analysis of response frequencies was carried out to determine if there were changes (increase, decrease, no change) in the presence of each of the symptoms and emotions since the beginning of the pandemic. To analyze whether these changes vary according to the gender and age of the children, the SS of the family and the containment measure in place, the means of the mental health dimensions of the children and adolescents were compared through the use of the t test or one-way ANOVA as appropriate. Then, to analyze the existence of interaction between these factors factorial ANOVA was used. Effect sizes were calculated through the use of Cohen’s d statistic or partial eta squared (η2p2) as appropriate. To analyze the relationship between the caregivers’ and their children’s mental health dimensions, multiple linear regression models were made. Finally, to analyze whether this association may be moderated by the sociodemographic factors mentioned above, moderation analyses were performed. To do this, factors were coded as dummy variables and then new variables were created by multiplying the dummy variables by the mental health variables in caregivers. It was taken as evidence of moderation the significance of the interaction coefficient for the sociodemographic variables of two groups (i.e., gender and containment measure), and the significance of the change in F for the variables with more than two groups (i.e., age groups and SS) in the model that includes the terms of the interaction with respect to the previous ones (Warner, 2013). All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software (Version 25.0).

Results

Descriptive and Correlation Analyses

The range, minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation values for all dimensions of mental health (both for children and adolescents and parents and caregivers) and participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Regarding the correlation analyses through Pearson’s r coefficient, it can be observed that all the mental health variables of parents and/or caregivers and those variables related to concerns are correlated in the expected ways with the mental health variables of children and adolescents (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the mental health dimensions and participants characteristics

| Range | Min. | Max. | M | SD |

Gender N(%) |

Age N(%) |

SS N(%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children and adolescents mental health dimensions informed by parents and/or caregivers | Impulsivity-inattention | 2.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 2.26 | 0.36 |

Girls: 572 (47.5) Boys: 624 (51.8) Others: 9 (0.7%) |

3–5: 233 (19.3) 6–8: 289 (24) 9–11: 270 (22.4) 12–14: 216 (17.9) 15–18: 197 (16.3) |

Medium: 102 (12.25) Medium high: 353 (42.42) High: 377 (45.31) |

| Dependence-withdrawal | 1.75 | 1.25 | 3.00 | 2.28 | 0.37 | ||||

| Anxiety-depression | 1.83 | 1.17 | 3.00 | 2.27 | 0.31 | ||||

| Aggression-irritability | 1.88 | 1.13 | 3.00 | 2.27 | 0.33 | ||||

| Positive affect | 41.67 | 8.43 | |||||||

| Parents and/or caregivers mental health dimensions | Anxiety | 51.15 | 2.00 | 53.15 | 23.14 | 9.87 |

Mothers: 999 (82.9) Fathers: 132 (10.9) Others: 74 (6.2) |

Range=60 Min. = 19; Max. = 79 M = 41.94 DS = 7.57 |

|

| Depression | 45.00 | 0.00 | 45 | 10.25 | 7.86 | ||||

| Positive affect | 37.00 | 10.00 | 47.00 | 24.79 | 7.81 | ||||

| Negative affect | 33.00 | 10.00 | 43.00 | 17.81 | 6.72 | ||||

| Concerns | 15.00 | 0.00 | 15.00 | 6.25 | 3.20 |

The asymmetry and kurtosis values are mostly located within ± 1, and only some within ± 2, which is considered acceptable to characterize the distributions of the different levels of the variables as normal (Field, 2013; George & Mallery, 2016). Only the parents and caregivers’ depression score showed a kurtosis which was above ± 2. SS social status

Table 2.

Correlations between the variables under study

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents and caregivers mental health dimensions | 1. Anxiety | – | 0.73** | 0.83** | − 0.60** | 0.40** | 0.32** | 0.23** | 0.14** | 0.38** | 0.24** | 0.23** | 0.14** | 0.31** | 0.26** | − 0.34** |

| 2. Depression | – | 0.75** | − 0.62** | 0.28** | 0.22** | 0.15** | 0.13** | 0.32** | 0.18** | 0.24** | 0.16** | 0.22** | 0.24** | − 0.23** | ||

| 3. Negative affect | – | − 0.46** | 0.37** | 0.24** | 0.23** | 0.15** | 0.37** | 0.25** | 0.23** | 0.20** | 0.27** | 0.28** | − 0.22** | |||

| 4. Positive affect | – | − 0.22** | − 0.24** | − 0.07 | − 0.14** | − 0.19** | − 0.11 | − 0.25** | − 0.18** | − 0.26** | − 0.25** | 0.31** | ||||

| 5. Total concerns | – | 0.54** | 0.71** | 0.60** | 0.66** | 0.72** | 0.21** | 0.14** | 0.22** | 0.17** | − 0.19** | |||||

| 5.1 Home economic situation | – | 0.26** | 0.09** | 0.29** | 0.17** | 0.12** | 0.10* | 0.10* | 0.12** | − 0.13** | ||||||

| 5.2 Emotional impact on children | – | 0.17** | 0.57** | 0.41** | 0.14** | 0.08* | 0.17** | 0.11** | − 0.10* | |||||||

| 5.3 Children’s school homework | – | 0.28** | 0.42** | 0.12** | 0.11** | 0.12** | 0.09* | − 0.12** | ||||||||

| 5.4 Emotional impact itself | – | 0.42** | 0.14** | 0.07 | 0.12** | 0.11** | − 0.04 | |||||||||

| 5.5 Changes in one’s social life | – | 0.13** | 0.06 | 0.15** | 0.12** | − 0.13** | ||||||||||

| Children and adolescents mental health dimensions informed by parents and caregivers | 6. Impulsivity-inattention | – | 0.44** | 0.49** | 0.65** | − 0.32** | ||||||||||

| 7. Dependence-withdrawal | – | 0.39** | 0.56** | − 0.08** | ||||||||||||

| 8. Anxiety-depression | – | 0.51** | − 0.48** | |||||||||||||

| 9. Aggression-irritability | – | − 0.27** | ||||||||||||||

| 10. Positive affect | – |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0 .01

First Objective: Analysis of Changes Perceived by Parents and Caregivers

Parents and caregivers were expected to report an increase in clinical symptomatology and a decrease in positive emotions since the initiation of restraint measures (Hypothesis 1). The percentages corresponding to the frequencies observed by parents and caregivers in each item of children’s and adolescents’ mental health dimensions are shown in Table 3. The majority of parents and caregivers stated that they did not observe changes in the behaviors and emotions of their children and adolescents since the initiation of containment measures (e.g., “Cannot sit quietly”: 62.3% of parents and caregivers stated “same as before”; “Disobeys”: 66.3%; “Interest”: 55.4%, etc.). Nevertheless, a high percentage of parents and caregivers (around 35–46.5%) reported an increase in several clinical indicators. Children and adolescents were described by their parents and caregivers as exhibiting behaviors such as arguing (46.5%), being irritable (45.8%), fighting (41.6%), throwing tantrums (40.7%) and getting easily frustrated (35.4%) (aggression-irritability). They were also described as demanding more attention (45.8%) and being more attached (39.1%) (dependence-withdrawal). Sudden mood swings (38.6%) and greater concentration difficulties (36.5%) (impulsivity-inattention) were also stated by parents and caregivers. Greater tension, nervousness (42.4%), fear and anxiety (36.3%) (anxiety-depression) were also reported. With regard to changes in sleeping and eating habits, an increase was reported in indicators such as eating a lot (28.9%), having problems falling asleep (35.9%) and sleeping a lot (33.9%). Similarly, a high percentage of parents and caregivers (around 39–52%) reported a decrease in many of positive emotions: liveliness (39.4%), tranquility (40.8%), enthusiasm (41.7%), liveliness (39.4%) and being active (52%).

Table 3.

Proportion of parents and/or caregivers’ responses (in percentages) for each item related to children and adolescents behavior and affect

| Less than before | Same as before | More than before | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impulsivity-inattention | |||

| Cannot focus or pay attention for a long time | 5.6 | 57,8 | 36.5 |

| Cannot sit quietly; is restless or hyperactive | 7.6 | 62.3 | 30 |

| Acts without thinking | 4.6 | 76.3 | 19.2 |

| Mood or feelings change suddenly | 1.8 | 59.6 | 38.6 |

| Dependence-withdrawal | |||

| Acts as if he/she was underage | 6.6 | 71.6 | 21.8 |

| Is too dependent or attached to adults | 7.6 | 53.4 | 39.1 |

| Demands a lot of attention | 4.8 | 49.4 | 45.8 |

| Likes drawing attention or playing the clown | 2.3 | 70.5 | 27.1 |

| Aggression-irritability | |||

| Argues a lot | 6.1 | 47.5 | 46.5 |

| Destroys his/her things and/or the things of those who live with him/her | 2.3 | 89 | 8.7 |

| Disobeys | 6.5 | 66.3 | 27.2 |

| Gets jealous easily | 3 | 71.4 | 25.6 |

| Fights | 4 | 54.4 | 41.6 |

| Is moody or throws tantrums | 3.6 | 55.7 | 40.7 |

| Behaves in a noisy, loud way | 2.9 | 67.4 | 29.7 |

| Gets easily frustrated | 3.9 | 60.7 | 35.4 |

| Seems obstinate, moody or irritable | 3.2 | 51 | 45.8 |

| Anxiety-depression | |||

| Cries a lot | 3.6 | 64.5 | 32 |

| Is nervous, tense | 4.7 | 53 | 42.4 |

| Is too fearful or gets anxious | 3.7 | 60 | 36.3 |

| Seems unhappy, sad or depressed | 3.9 | 68.6 | 27.5 |

| Worries too much about everything | 4.8 | 75.9 | 19.3 |

| Is inactive, sluggish or lacks energy | 4.6 | 63.6 | 31.8 |

| Sleep and eating difficulties | |||

| Has nightmares | 3.8 | 77 | 19.2 |

| Eats too much | 5.8 | 65.3 | 28.9 |

| Sleeps little | 14.3 | 72.9 | 12.9 |

| Sleeps a lot | 5.5 | 60.7 | 33.9 |

| Eats little | 9.3 | 84.7 | 6 |

| Wakes up often during the night | 3.7 | 76.7 | 19.6 |

| Has trouble sleeping | 2 | 62.2 | 35.9 |

| Positive affect | |||

| Interest | 34.7 | 55.4 | 9.9 |

| Attention | 34.4 | 55.9 | 9.7 |

| Enthusiasm | 41.7 | 49.8 | 8.5 |

| Happiness | 29.8 | 57.7 | 12.5 |

| Strength | 24.7 | 62.2 | 13.1 |

| Energy | 34.8 | 42.7 | 22.5 |

| Tranquility | 40.8 | 49.1 | 10 |

| Forcefulness | 15.9 | 47.8 | 36.3 |

| Joy | 24.6 | 61.6 | 13.9 |

| Activity | 52 | 33.4 | 14.6 |

| Pride | 15.4 | 72.3 | 12.4 |

| Pleased | 25.6 | 62 | 12.4 |

| Charm | 39.6 | 53.4 | 7.1 |

| Audacity | 29.1 | 55.9 | 14.9 |

| Liveliness | 39.4 | 49 | 16.1 |

Second Objective: Analyses of Differences in Mental Health Dimensions According to Sociodemographic Factors and Their Interaction

Symptoms and positive emotions were expected to vary according to sociodemographic factors and their interaction (Hypothesis 2). The analyses for the different dimensions, according to the factors considered, are presented below. Table 4 shows the means and standard deviations of the mental health dimensions for each sociodemographic variable.

Table 4.

Mean differences in the mental health dimensions of children and adolescents

| Factor | n (%) | Impulsivity-inattention | Dependence-withdrawal | Anxiety-depression | Aggression-irritability | Positive affect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Girl | 572 (47.5) | 2.26 (0.35) | 2.28 (0.38) | 2.28 (0.32) | 2.27 (0.34) | 41.87 (8.39) |

| Boy | 624 (51.8) | 2.25 (0.38) | 2.27 (0.36) | 2.26 (0.30) | 2.27 (0.33) | 41.51 (8.46) |

| Other | 9 (0.7%) | |||||

| Age group | ||||||

| 3–5 years old | 233 (19.3) | 2.28 (0.36) | 2.52 (0.34) | 2.27 (0.28) | 2.40 (0.35) | 45.43 (7.52) |

| 6–8 years old | 289 (24) | 2.36 (0.37) | 2.38 (0.33) | 2.29 (0.30) | 2.35 (0.32) | 42.78 (8.22) |

| 9–11 years old | 270 (22.4) | 2.31 (0.35) | 2.26 (0.36) | 2.30 (0.33) | 2.28 (0.32) | 40.18 (8.35) |

| 12–14 years old | 216 (17.9) | 2.16 (0.36) | 2.08 (0.35) | 2.23 (0.31) | 2.18 (0.32) | 39.91 (7.87) |

| 15–18 years old | 197 (16.3) | 2.11 (0.32) | 2.07 (0.25) | 2.23 (0.30) | 2.11 (0.26) | 39.55 (8.78) |

| Social status | ||||||

| Medium | 102 (12.25) | 2.26 (0.36) | 2.26 (0.37) | 2.28 (0.32) | 2.30 (0.34) | 42.47 (9.83) |

| Medium High | 353 (42.42) | 2.26 (0.35) | 2.27 (0.37) | 2.29 (0.31) | 2.28 (0.32) | 41.52 (8.17) |

| High | 377 (45.31) | 2.25 (0.36) | 2.29 (0.39) | 2.27 (0.30) | 2.26 (0.34) | 41.93 (7.97) |

| Regime | ||||||

| Isolation | 331 (27.5) | 2.27 (0.38) | 2.29 (0.39) | 2.30 (0.31) | 2.29 (0.34) | 40.47 (8.26) |

| Distancing | 874 (72.5) | 2.25 (0.36) | 2.27 (0.37) | 2.26 (0.30) | 2.27 (0.33) | 42.12 (8.45) |

Gender

We expected girls to have more symptoms of anxiety and depression than boys, and boys to have more symptoms of aggression and irritability than girls (Hypothesis 2.1). No significant differences in mental health dimensions by gender were observed: impulsivity-inattention, t(1194) = 0.67, p = 0.50, d = 0.03; dependence-withdrawal, t(1194) = 0.67, p = 0.49, d = 0.03; anxiety-depression, t(1194) = 1.36, p = 0.17, d = 0.07; aggression-irritability, t(1194) = 0.07, p = 0.93, d < 0.01; positive affect, t(1194) = − 0.73, p = 0.46, d = 0.04.

Age Group

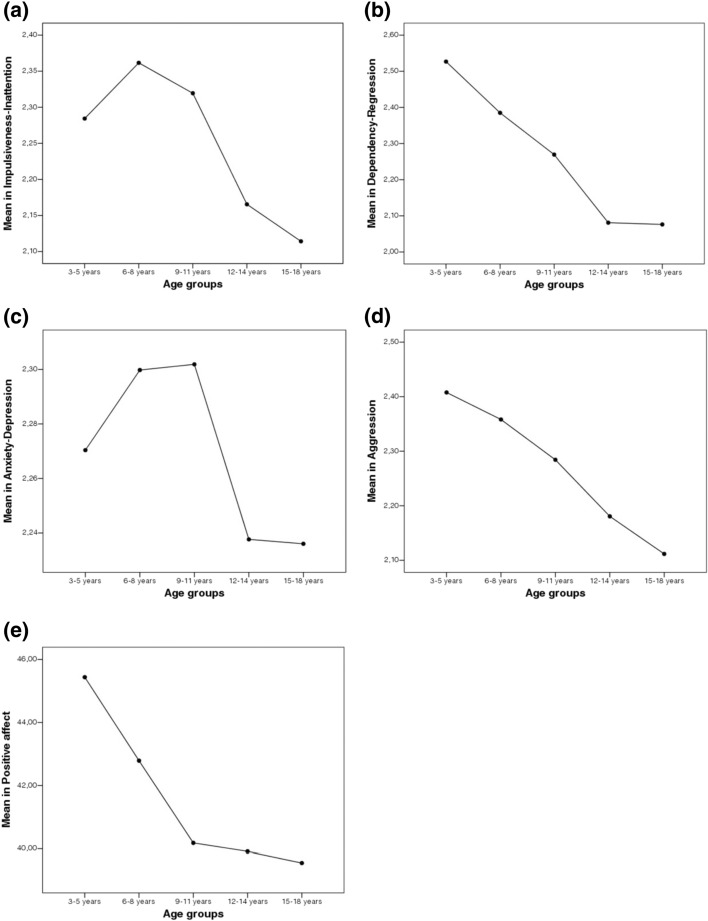

Young children were expected to present more symptoms of impulsivity, inattention, and regression than adolescents, and adolescents were expected to have more symptoms of anxiety and depression and less positive affect than young children (Hypothesis 2.2). Significant differences in all mental health dimensions were observed: impulsivity-inattention, F(4,1200) = 19.81, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.06; dependence-withdrawal, F(4,1200) = 74.54, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.19; anxiety-depression, F(4,1199) = 2.51, p = 0.04, η2p > 0.01; aggression-irritability, F(4,1200) = 31.90, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.09; positive affect, F(4,1200) = 21.83, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.06. Statistically significant mean differences and medium to large effect sizes were observed among age groups in all mental health dimensions, except for anxiety-depression. The mean plots (see Fig. 1) show that children from 3 to 8 years possess the highest means in all the variables, and smaller means are observed among the groups of older children and adolescents. Unlike the rest of the dimensions, anxiety-depression showed the highest means for children between the ages of 9 and 11. Young children aged 3–8 years had the highest means in impulsivity-inattention, dependence-withdrawal and aggression-irritability. But as for adolescents, preadolescents aged 9–11 years (not older children) showed the highest means in anxiety-depression. Older children and adolescents (9–18 years old) presented the most notable decreases in positive affect.

Fig. 1.

Mean plots for each mental health dimension (a–d) in children and adolescents by age group

Social Status

Regarding SS, children and adolescents from families with lower SS were expected to present more symptoms (Hypothesis 2.3). No significant differences in the dimensions of mental health were observed: impulsivity-inattention, F(2,829) = 0.07, p = 0.93, η2p < 0.01; dependence-withdrawal, F(2,829) = 0.31, p = 0.73, η2p < 0.01; anxiety-depression, F(2,829) = 0.49, p = 0.60, η2p < 0.01; aggression-irritability, F(2,829) = 0.89, p = 0.40, η2p < 0.01; positive affect, F(2,829) = 0.57, p = 0.56, η2p < 0.01.

Containment Measure

Children and adolescents who were in the distancing phase were expected to present fewer symptoms and more positive emotions than those who were still in strict isolation (Hypothesis 2.4). Significant differences in two mental health dimensions were observed: anxiety-depression, t(1203) = 1.95, p = 0.05, d = 0.12; and positive affect, t(1203) = − 3.04; p = 0.002, d = − 0.19. No significant differences were observed in the other dimensions: impulsivity-inattention, t(1203) = 0.72, p = 0.46, d = 0.04; dependence-withdrawal, t(1203) = 0.82, p = 0.41, d = 0.05; aggression-irritability, t(1203) = 1.14, p = 0.25, d = 0.07. Children and adolescents in strict isolation presented higher means of anxiety-depression (but not the other dimensions) and less means of positive affect compared to those who were going through the distancing phase (see Table 4).

Interaction Between Factors

We expected that adolescent girls would present greater symptoms of anxiety and depression than the rest of the groups; and that young boys would present more symptoms of impulsivity and inattention than the rest of the groups (Hypothesis 2.5). These interaction effects were not observed (Model for anxiety-depression: F(9,1185) = 1.66, p = 0.09, η2p = 0.01, R2 adjusted = 0.00; Interaction: F(4,1186) = 0.77, p = 0.54; η2p = 0.00; Model for impulsivity-inattention: F(9,1186) = 9.29, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.06, R2 adjusted = 0.05; Interaction: F(4,1186) = 1.15, p = 0.33; η2p = 0.00). Due to this, we decided to explore possible interaction effects by combining the different factors with each other for all dimensions of mental health of children and adolescents (i.e., gender * age, gender * SS, gender * containment measure, age * SS, age * measure of containment, and medical of containment by SS for each of the mental health dimensions). Just a single interaction effect between factors emerged. Gender and age showed interaction effect for the dependence-withdrawal dimension, Model: F(9,1186) = 35.19, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.20, R2 adjusted = 0.21; Interaction: F(4,1186) = 3.51, p < 0.01; η2p = 0.12. Gender differences were observed in the youngest group of children, specifically girls aged 3–5 (girls M = 2.58, SD = 0.03; boys M = 2.47, SD = 0.03; Difference in means = 0.10, SD = 0.04, p = 0.04) and boys aged 6–8 (boys M = 2.43, SD = 0.02; girls M = 2.33, SD = 0.02; Difference in means = 0.10, SD = 0.04, p = 0.04) presented the highest levels of dependence-withdrawal. No support was found for the original hypothesis, but a singular interaction effect was observed.

Third objective: Relationship with Mental Health Dimensions of Parents and Caregivers

We expected that parents’ and caregivers’ symptoms and positive affect would be associated with children’s and adolescents’ symptoms and positive emotions (Hypothesis 3). Although the predictive capacity of each model was relatively low, four dimensions of parents’ and caregivers’ mental health had explanatory power over dimensions of their children’s and adolescents’ mental health, controlling for the possible effect of sociodemographic factors (see Table 5). Specifically, higher symptomatology in parents and caregivers was expected to be related to higher symptomatology and lower positive affect in children and adolescents (Hypothesis 3.1). Analyses showed that parents’ and caregivers’ anxiety was associated with greater anxiety-depression and less positive affect in the children and adolescents in their care. The negative affect of parents and caregivers was associated with greater dependence-withdrawal and aggression-irritability in children and adolescents. Parental and caregiver concerns were only marginally associated with greater impulsivity-inattention in children (p = 0.06). As for parent and caregiver positive affect, it was expected to be related to fewer symptoms and greater positive emotions in children and adolescents (Hypothesis 3.2). Positive parental and caregiver affect was associated with less impulsivity-intention, dependence-withdrawal, and greater positive affect in children and adolescents.

Table 5.

Relationship between mental health dimensions in parents or caregivers and mental health dimensions in children and adolescents

| Impulsivity-inattention | Dependence-withdrawal | Anxiety-depression | Aggression-irritability | Positive affect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(9,372) = 7.10; p < 0.001; R2 adjusted = 0.12 | F(9,372) = 15.35; p < 0.001; R2 adjusted = 0.25 | F(9,372) = 5.18; p < 0.001; R2 adjusted = 0.09 | F(9,372) = 10.81; p < 0.001; R2 adjusted = 0.18 | F(9,372) = 10.29; p< 0.001; R2 adjusted = 0.18 | |

| Gender | − 0.02 | − 0.06 | − 0.06 | − 0.02 | − 0.00 |

| Age | − 0.21*** | − 0.44*** | − 0.04 | − 0.33*** | − 0.20*** |

| Social status | − 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | − 0.05 | − 0.10* |

| Regime | − 0.02 | − 0.02 | − 0.00 | − 0.02 | 0.08 † |

| Anxiety | − 0.08 | − 0.15 | 0.20* | − 0.00 | − 0.32*** |

| Depression | 0.06 | − 0.01 | − 0.04 | − 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Negative affect | 0.16 | 0.19* | 0.07 | 0.23** | 0.07 |

| Concerns | 0.09 † | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | − 0.06 |

| Positive affect | − 0.14* | − 0.15* | − 0.09 | − 0.11 | 0.15* |

†p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Fourth Objective: Moderating Effects of Sociodemographic Factors on Parent–Child Mental Health Relationships

We expected sociodemographic factors to moderate some of the parent–child mental health relationships (Hypothesis 4). Moderating analyses of the various sociodemographic factors are presented below.

Moderating Effect of Gender

It was expected that parents and caregivers’ depression symptoms would be associated with children and adolescents’ depression symptoms, and that this relationship would be stronger for boys than girls (Hypothesis 4.1). This expected effect was not observed, F(3,620) = 12.73, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.05; β of the interaction= 0.08, p = 0.26. Therefore, it was decided to explore the moderator effect of gender on the relationships between the remaining mental health dimensions of parents and children. Two statistically-significant moderation effects were found. Gender moderated the relationship between depression in caregivers and positive affect in children and adolescents, F(3,620) = 13.36, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.05; β of the interaction = − 0.15, p = 0.04. Thus, a higher level of depression was associated with less positive affect, being this more pronounced among boys than girls. The regression slope was more pronounced in the boys group, indicating that depression of parents and caregivers affected them to a greater extent. Gender also moderated the relationship between positive affect of parents and caregivers, and aggression-irritability in children and adolescents, F(3,620) = 16.15, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.06, β of the interaction = 0.29, p = 0.03. A higher level of positive affect was associated with less aggression-irritability, and this relation was stronger for girls than boys. The regression slope was more pronounced in the girls group, indicating that they benefited more from the positive affect of their parents and caregivers.

Moderating Effect of Age

It was expected parent–child mental health relationships would be stronger in older children and adolescents than in younger children (Hypothesis 4.2). Four moderation effects of age were observed on the relationship between parents and caregivers mental health and the positive affect and dependence-withdrawal of children and adolescents. Higher levels of anxiety, F(9,618) = 18.11, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.19, Change in F = 3.31, p = 0.01, depression, F(9,618) = 12.38, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.13, Change in F = 3.76, p < 0.001, and negative affect, F(9,618) = 12.66, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.14, Change in F = 3.45, p = 0.008, of parents and caregivers were associated with less positive affect in children and adolescents. These associations were weaker for children aged 3–5 than the rest of age groups (i.e., 6 years of age and older). In other words, the regression slope is always less steep for children aged 3–5, indicating that they were less affected by their parents and caregivers’ symptoms. Regarding dependence-withdrawal, a higher level of depression in parents and caregivers was associated with greater dependence-withdrawal in all age groups, F(9,618) = 22.86, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.23, Change in F = 2.84, p = 0.02, but children aged 9–11 were more affected. The regression slope is more pronounced for this group, indicating that depression in caregivers affects them more than the rest of the age groups.

Moderating Effect of SS

It was expected that these relations would be stronger in children and adolescents of lower SS families than those of higher SS (Hypothesis 4.3). On the one hand, a higher level of positive affect in parents and caregivers was associated with less impulsivity, F(5,622) = 9.97, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.06, Change in F = 3.18, p = 0.04, and less aggression-irritability, F(5,622) = 10.85, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.07, Change in F = 3.07, p = 0.04, in children and adolescents to a greater extent for those having a medium-high and high SS. These groups presented the steepest slopes, which indicate that the positive affect of their parents and caregivers benefited them more than children and adolescents of medium SS. On the other hand, contrary to expectations, higher levels of both negative affect and concerns of parents and caregivers were associated respectively with less positive affect, F(5,622) = 9.09, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.06, Change in F = 3.38, p = 0.03), and with greater dependence-withdrawal, F(5,608) = 4.61, p < 0.001, R2 adjusted = 0.02, Change in F = 2.90, p = 0.05. These associations were stronger for those having a medium-high and high SS, with more pronounced slopes, which indicates that the negative affect and concerns of their parents and caregivers affected them more than their peers of medium SS.

Moderating Effect of Containment Measure

It was expected that these relationships would be stronger among children and adolescents who were in strict isolation than those who were in the distancing phase (Hypothesis 4.4). No support for these hypotheses was found (for all models β of the interaction p > 0.05). Containment measure did not moderate any of these relationships.

Discussion

The first objective of this work was to analyze the presence of changes in psychopathological symptomatology and positive emotions in children and adolescents aged 3–18 years as reported by their parents and caregivers since the onset of isolation. It was expected for parents and caregivers to report an increase in clinical symptomatology and a decrease in positive emotions since the initiation of restraint measures. The results showed that many children did not present changes in symptomatology during the confinement. Nevertheless, a high percentage of parents and caregivers (around 35–46.5%) reported an increase in several clinical indicators. Children and adolescents were described by their parents and caregivers as showing greater irritability and behaviors such as arguing, fighting, throwing tantrums and getting easily frustrated (aggression-irritability); they were also described as demanding more attention and being more attached (dependence-withdrawal); and having sudden mood swings and greater concentration difficulties (impulsivity-inattention), and greater tension, nervousness, fear and anxiety (anxiety-depression). As regards changes in sleeping and eating habits, increases in indicators such as eating a lot, having trouble falling asleep and sleeping a lot were reported. They also reported observing decreases in positive emotions such as liveliness, tranquility, enthusiasm and being active. These results show changes in the mental health dimensions of children and adolescents after the beginning of the isolation period, specifically increases in symptomatology and decreases in positive emotions since the introduction of containment measures, as stated in the literature (Racine et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020). It has been indicated that changes in habits and routines, as a result of a prolonged and massive restriction on social contact for children and adolescents, leads to discomfort and psychological effects (Witt et al. 2020) which can explain these increases in symptoms and decreases in positive emotions.

The second objective of this work was to analyze differences in mental health dimensions according to sociodemographic factors and their interaction. Differences were observed only for two sociodemographic factors: age groups and containment measures. Regarding age, young children were expected to have more symptoms of impulsivity, inattention, and regression than adolescents. In fact, the highest prevalence of symptoms was reported by parents and caregivers of children aged between 3 and 8. This is linked to the evolutionary stages of development (Baeyens et al., 2005), and has been reported in previous studies in the actual pandemic context (Domíguez-Álvarez et al., 2020; Jiao et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020). Adolescents were expected to present more symptoms of anxiety and depression than young children. However, our data indicate that the highest levels of anxiety-depression were reported in children aged between 9 and 11. Under regular circumstances, 9–11 years-old children are characterized by an increase in academic demands that usually results in higher levels of anxiety and discomfort (e.g., Punaro & Reeve, 2012). In addition to these characteristics, the increase in academic demands in the pandemic context (e.g., virtual learning; Surkhali & Garbuja, 2020) could explain these results. Finally, adolescents were expected to show less positive affect than younger children. Older children and adolescents presented the most notable decreases in positive affect, which is consistent with normative patterns of change in youth positive affect across the adolescent transition (Griffith et al., 2021). In summary, the results regarding age differences are consistent with what was expected according to developmental stages and the results of other studies in the actual pandemic context. However, special attention should be given to children between 9 and 11 years old since they had the highest levels of anxiety and depression.

Regarding containment measures, children and adolescents who were in the distancing phase were expected to present fewer symptoms and more positive emotions than those who were still in strict isolation. Differences related to containment measures were observed, in the sense that the children and adolescents who were in isolation during data collection were evaluated by their parents and caregivers as presenting higher levels of anxiety-depression and lower levels of positive affect compared to children in the distancing phase. This goes in line with a study conducted in Italy and Spain, that found lower levels of symptomatology in children in Italy, who had been granted permissions by the government to go for walks accompanied by an adult at the time of data collection. Containment measures which provide the possibility of going on recreational outings may allow children to be more active and this may have a favorable impact on their well-being (Orgilés et al., 2020).

In regard to the interaction between the sociodemographic factors, a singular effect was found. Gender differences were observed only in the younger subjects. Specifically, girls aged between 3 and 5 and boys between 6 and 8 exhibited a greater dependence-withdrawal. It has been reported that the youngest children exhibit more behaviors linked to dependence-withdrawal in the pandemic context (Pisano et al., 2020), and it has been indicated that dependent behaviors can be more frequent in girls based on traditional gender stereotypes (e.g., Whiting & Edwards, 1973). This could explain why girls aged between 3 and 5 were seen as more dependent than boys their age in our results. It is important to note that children between 6 and 8 are in the first stage of primary school in this health emergency context which implies virtual learning. Some studies found that young children have academic gender stereotypes by which they believe that boys have less skills, motivation and self-regulation than girls, and that these stereotypes negatively affect boys academic performance (Hartley & Sutton, 2013). It has been suggested that these stereotypes could be inferred from parents and adults (McKown & Strambler, 2009). This may explain why boys aged between 6 and 8 were rated by their parents and caregivers as acting more underage, dependent and demanding attention, and could constitute a special group for education interventions.

The third objective was to analyze whether symptomatology and positive emotions in parents and caregivers were associated with symptomatology and positive affect in children and adolescents. It was expected that greater symptoms in parents and caregivers would be related to greater symptoms and less positive affect in children and adolescents. Results showed that parent and caregiver anxiety was associated with greater anxiety-depression and less positive affect in children and adolescents; and parent and caregiver negative affect was associated with greater dependence-withdrawal and aggression-irritability in children and adolescents (parent and caregiver concerns were only marginally associated with greater impulsivity-inattention). These results are consistent with literature (e.g.; Duhig & Phares, 2009; Van Der Bruggen et al., 2008) and recent studies in the context of pandemic (Domínguez-Álvarez et al., 2020; Duhig & Phares, 2009; Orgilés et al., 2020; Phares & Compas, 1992; Rosen et al., 2020; Van Der Bruggen et al., 2008). Notably, it has been reported that stress is a mediating factor in these relationships (e.g., Weijers et al., 2018). By understanding the current health emergency situation due to COVID-19 as a highly stressing factor in itself, with an impact on the exercise of parenting (Lee et al., 2021), it can be understood that these associations are present in the pandemic context.

Regarding parents’ and caregivers’ positive affect, it was expected that greater positive affect would be related to fewer symptoms and greater positive emotions in children and adolescents. Results showed that it was associated with less impulsivity-inattention, dependence-withdrawal and greater positive affect in children and adolescents. These results are related to those obtained in the study of Romero et al. (2020) on the effects of confinement on Spanish children. These authors found an association between specific positive parenting practices and child positive outcomes. These results showed that mental health of parents and caregivers is related to their children’s mental health dimensions and contribute to understanding the importance of parent-related variables to children’s adaptation and well-being in the context of a crisis.

The fourth objective was to analyze whether these parent–child mental health relationships vary according to gender, age, SS and containment measure. It was expected that sociodemographic factors moderate some of those relationships. Two moderation effects by gender were found. Higher levels of parents’ depression were associated with less positive affect, making this relation more pronounced among boys than girls. This indicates that boys were more affected than girls regarding the depression levels of their parents and caregivers. Typical patterns of gender differences show that girls tend to exhibit a greater number of internalizing symptoms (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008); however, when caregivers have depression symptoms, this pattern may change and boys may have more internalizing symptoms (Watson et al., 2012). Here, the more depression symptoms parents and caregivers presented, the greater was the decrease of the boys’ positive affect, which is consistent with previous research in non-pandemic contexts. Also, higher levels of parents and caregivers’ positive affect was associated with less aggression-irritability, making this effect stronger on girls. Thus, the positive affect of parents and caregivers benefited girls more than boys. It has been indicated that threat perception is a distinctive characteristic of these behaviors and that it is more present in boys (Bettencourt & Miller, 1996). That could explain why even though positive affect of parents and caregivers reduces aggression-irritability behaviors, it does so to a lesser extent among boys. These results of gender moderation are relatively consistent with previous patterns reported in the literature (Rutter et al., 2003).

A moderation effect of age was also observed. First, anxiety, depression, and negative affect of parents and caregivers were associated with less positive affect in all age groups but to a lesser extent in children aged 3–5 years. This could indicate that the symptoms experienced by adults affected them less than the rest of the age groups. Other studies in non-pandemic contexts have reported similar results, in the sense that the associations between the symptomatology of caregivers and that of children become stronger in older children and adolescents because parents and children influence one another but it becomes more evident the course of the years (Connell & Goodman, 2002). Secondly, depression in parents and caregivers was associated with greater dependence-withdrawal in all age groups, but especially in children aged 9–11, indicating that depression in their caregivers affected them more than the rest of the age groups. This result, added to the previous that children aged 9–11 presented higher averages of anxiety-depression among all age groups, shows a greater vulnerability in this age group in the current health emergency context.

Finally, moderation effects related to SS were observed. On the one hand, higher positive affect of parents and caregivers was associated with less impulsivity-inattention and aggression-irritability in children and adolescents, but to a greater extent in those belonging to a medium-high and high SS. The positive affect of their parents and caregivers benefitted them more than children and adolescents of medium SS. These results are in line with studies conducted in non-pandemic contexts that report parents of higher SS are more capable of adapting their behavior to their children’s needs than parents of lower SS (Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al., 2007).

On the other hand, contrary to expectations, parents and caregivers’ negative affect and concerns were associated with less positive affect and more dependence-withdrawal in children and adolescents, mostly in those having medium-high and high SS. This suggests that they were more affected by their parents and caregivers’ negative affect and concerns than children of medium SS. This seemingly contradictory result must be considered in light of studies in Latin America and the actual pandemic context. It has been reported that working Latin-American mothers of high SS showed a greater number of hostile and coercive behaviors at home (Weis & Toolis, 2010), contributing to a more stressful and hostile environment. It has been suggested that the participation of women in the workforce could conflict with traditional gender roles of childcare for this culture. In the actual context, women experience higher levels of stress, probably in an attempt to reconcile working and family life (Zamarro & Prados, 2021). Importantly, this situation is taking place not only in Argentina (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2020) but around the world (Rajkumar, 2020). Taking this into consideration may help understanding why negative affect and concerns of medium-high and high SS parents and caregivers affect their children and adolescents more than families with medium SS.

This study had several limitations. The first one was related to the cross-sectional design, which does not allow for the collection of evidence of causality. In this respect, we will continue to follow up the participants, with the aim of obtaining information about changes in the mental health variables analyzed. Secondly, data collection was done online and through the snowball sampling approach, mainly through social networks (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter), which could have introduced a bias in the sample. In fact, one of the limitations of the study is that the sample does not represent individuals belonging to a low or medium-low SS, which makes it impossible to generalize the results and apply them to the whole Argentinian population. Third, information about children and adolescents’ mental health was only reported by their parents and caregivers. In better evaluation circumstances, it would be advisable to include other informants (e.g., teachers, other family members or responsible adults, the children themselves aged 9 years and older). Despite these limitations, the study was conducted on a large sample of Argentinian families during the implementation of different isolation and containment measures.

Conclusions

In summary, our results show that a considerable proportion of parents and caregivers perceive changes in their children’s emotional state and behaviors compared to before the pandemic. Particularly, they reported increased levels of aggression-irritability, dependence-withdrawal, impulsivity-inattention and anxiety-depression, in their children and adolescents. They also reported changes in sleeping and eating habits and decreases in positive emotions.

Regarding age groups, children aged 3–8 years old were the most affected by these increases (impulsivity-inattention, aggression-irritability, dependence-withdrawal), and older children and adolescents showed the most pronounced declines in positive affect. Particular attention should be paid to children aged 9–11 years showing the largest increases in anxiety-depression.

On the other hand, children and adolescents in the distancing phase presented less symptoms of anxiety-depression and more positive emotions than their peers in strict isolation. It is probable that having containment measures that contemplate short outings or walks alleviate the potential undesirable effects of containment measures (Orgilés et al., 2020).

Concerning specific groups, girls aged 3–5 years old and boys aged 6–8 years old presented marked increases in dependence-withdrawal behaviors. Particular attention should be paid to boys 6–8 regarding education, due to the stage of primary school in which they are during this health emergency context.

Results also showed the mental health of parents and caregivers was related to their children’s mental health dimensions. Specifically, parents’ and caregivers’ anxiety was associated with greater anxiety-depression and less positive affect in children and adolescents; and parents’ and caregivers’ negative affect was related with greater dependence-withdrawal and aggression-irritability in children and adolescents. Regarding parents’ and caregivers’ positive affect, it was associated with less impulsivity-inattention, dependence-withdrawal and greater positive affect in children and adolescents. Parent-related mental health dimensions are important to children’s adaptation and well-being in the actual pandemic context and could be targets of related interventions (e.g., Wang et al., 2021a, b).

These parent–child mental health relationships were affected by gender, age and SS of children and adolescents. Parents and caregivers’ depression affected boy’s positive affect more than girls. Also, higher levels of parents and caregivers’ positive affect was associated with less aggression-irritability, being this effect stronger for girls than boys. Usual variations based on gender may not be altered by this health emergency context. Concerning age groups, anxiety, depression, and negative affect of parents and caregivers were associated with less positive affect in all age groups but to a lesser extent in children aged 3–5 years, which is consistent with what is reported in the literature. Finally, depression in parents and caregivers was associated with greater dependence-withdrawal in all age groups, but especially children aged between 9 and 11. This result, added to the children aged 9 to 11 showing higher averages of anxiety-depression, indicates a greater vulnerability in this age group in the current health emergency context.

Regarding SS, higher positive affect of parents and caregivers was associated with less impulsivity-inattention and aggression-irritability in children and adolescents, but to a greater extent in those belonging to a medium-high and high SS in line with pre-pandemic studies. Contrary to expectations, negative affect and concerns of parents and caregivers were associated with less positive affect and greater dependence-withdrawal in children and adolescents, mostly in those having a medium-high and high SS. This result alerts about the need to be attentive to the stress of working mothers with medium-high and high SS and how it affects their children and adolescents.

Most of these findings are in line with those previously reported in the literature. Efforts to safeguard the psychological health of children and adolescents should take careful consideration of the mental health status of their parents and caregivers, along with the possibility of short walks during isolation which may contribute to alleviating stress. Special attention should be paid in this pandemic context, particularly in Argentina, to boys aged 6–8 years (who are in the first stage of primary school and presented higher levels of dependence-withdrawal), to children aged between 9 and 11 years (who presented the highest levels of anxiety and depression and were the most affected by their parents’ and caregivers’ depression levels) and to those children and adolescents from medium-high and high SS whose parents and caregivers presented higher levels of negative affect and concerns about pandemic. It is expected that these results will provide information to other researchers, social agents, and policy makers to develop effective guidelines for COVID-19 and possible future outbreaks with the aim of promoting mental health care in children and adolescents.

Undoubtedly, this should be one of the central focal points for planning, designing and implementation of public policies and strategies to face the pandemic side effects. Based on our results about children and adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak in Argentina, we highly recommend that those institutions devoted to mental health care of children and adolescents work on the implementation of prevention and early intervention strategies, while being prepared for a possible increase in the demands for mental health related problems in children and adolescents.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Argentina, within the framework of the “Program for the Articulation and Federal Strengthening of Capacities in Science and Technology COVID-19” (Reference: EX-2020-18944823-APN-DDYGD#MECCYT).

Availability of data and materials