Abstract

This paper is based on analyzing the process of green innovation inspiration and green innovation compensation effect after the implementation of environmental regulations by the Chinese Government. This paper tests the hypothesis using the evolutionary game model and studies the underlying behavioral characteristics of the government, enterprises, and the relevant influencing factors. These influencing factors further aid in examining the evolution law applicable on both sides, which are aligned with the dynamic replication equation and evolutionary equilibrium states under different situations. The key variables used in this study include the concentration of government’s environmental regulation, the cost of the regulations, economic penalties, enterprise’s green innovation-related income, expenditures, and the enterprise’s performance appraisal. Moreover, the results of this study reflect the system stability and equilibrium strategy on the proportion of retained earnings spent by enterprises on green innovation activities and the Government’s strict environmental regulations. In the process of game strategy selection between the government and enterprises, the net income and weight of eco-efficiency indicators of the enterprises actively carrying out green innovation activities play a decisive role. Moreover, there should be reduced weight of economic benefits and increase the economic sanctions and innovation subsidies of enterprise pollution behaviors. Furthermore, reduced cost of regulations and innovation expenditures help guide enterprises to rationally allocate superior resources to enhance green enterprise innovation and take the level of innovation to the point that it achieves a win-win green sustainable development of economic performance and environmental performance.

Keywords: Jinshan Yinshan, Environmental protection, Institutional innovation regulation, Sustainable green innovation, Evolutionary game

Introduction

The major global challenge is addressing ecological and environmental problems (McCallen et al. 2019). Therefore, historically, we can observe how human generation over time carried out the evolution of advanced research and program initiatives for sustainable environment development (Olawumi and Chan 2018). Under the guidance of environmental regulation policies, enterprises can achieve their market competitiveness and profitability and consciously integrate environmental responsibility into corporate strategy, production, and management processes to undertake environmental protection (Xie et al. 2019). The important aspect of saving resources is to incorporate environmental performance into the enterprise’s comprehensive performance evaluation system and achieve a complete improvement of corporate value (Cai and Li 2018; Jiang et al. 2019a). To maximize profits, seize market share, and gain competitive advantage, enterprises must rely on advanced technology (Moravcikova et al. 2017). Taking innovation as the driving force by relying on the Research and Development (R&D) and promoting green technologies to achieve green transformation from the source is an inevitable choice to support the economic sustainability of the economy (Wang et al. 2019a, b).

Green innovation has increasingly gained more attention and is seen as a vital strategy for achieving sustainable growth with extreme environmental pollution levels created by industrial enterprises (De Jesus and Mendonça 2018; Pan 2016). Green innovation strategies acknowledge that enterprises must generate consumer and company value and dramatically reduce their environmental impact by producing new products and processes (Soewarno et al. 2019). Green product innovation incorporates the creation of new products that operate as raw materials and minimize firms’ energy usage or serve as essential goods that support consumer health and allow consumers to save natural resources and protect the environment for future generations (Sdrolia and Zarotiadis 2019). Besides that, green process innovation is designed to help enterprises reuse goods and minimize environmental emissions during production through technological advancements (Fernando et al. 2019). Many businesses are hesitant to invest in green innovation because they see it as an expense that hampers profit maximization (Li et al. 2017a, b). Due to external constraints, more enterprises understand the value of green innovation, hence, the need for it. Many researchers and practitioners agree that corporate green innovation predominantly occurs in the context of serious external pressures in the form of environmental regulation by governments (Gunarathne and Lee 2019; Li et al. 2017a, b).

Environmental regulations are related to direct and indirect government measures, including regulatory rules, economic policies, and market process policies involving ecological resources (Song et al. 2020). Eco-regulation continued to place costs on polluters after the 1990s, eventually weakening their competitiveness in the global market (Wu et al. 2014). In contrast, this strategy has traditionally prompted a few clashes between economists and policymakers (Li 2019). The theory has been questioned over the past two decades by several researchers who argue that environmental regulations can often increase economic efficiency rather than boost net costs (Jaffe et al. 1995).

Michael Porter’s work entirely and firmly illustrates this view and is related to the “Porter hypothesis” (Porter 1991). The Porter hypothesis notes that environmental policy will enable businesses to promote green innovation and that design benefits will potentially outweigh environmental costs (Ramanathan et al. 2017). However, some empirical studies have shown that ecological regulation does not significantly affect green innovation; thus, Porter’s hypothesis remains controversial (Bernauer et al. 2007; Borsatto and Amui 2019; Rubashkina et al. 2015). There are contradictory findings in the existing literature with regard to the Porter hypothesis. As discussed above, it is only always the case that regulations will translate into innovation; indeed the well-designed regulations are required to have significant and positive influence on business innovation model and performance. It is also in accordance with market-based and performance-based environmental regulations. Based on the Porter hypothesis, Chen and Hu (2018) examined the value-capturing role of competitive strategy. The study put forth the argument that firms operational in highly competitive environments can only maximize the profits based on green innovation practices if they have rightfully selected the relevant competitive strategy. Therefore, to reap the maximum gains from green practices, it is of importance to closely look into competitive strategies including response strategy, low-cost leadership and differentiation strategy. Moreover, in view of Porter hypothesis, there are different conditions, internal and external mechanisms which do not state that innovation inevitably offsets the cost of regulation. It never claims that regulations are always free lunch. Indeed, as discussed below in the proposed model, there are different costs attached to regulations. In some instances, despite stringent regulations, green innovations are weighted higher and offset the cost of regulation, and in some cases, it might not be the case.

Additionally, another significant external factor influencing the course and intensity of enterprise innovation is primarily controlled by customer requirements (Chen et al. 2017). On the one side of the coin, changing competitive market could generate opportunities for sustainable business practices (Velter et al. 2020). The flipside of the coin, in some situations, it may also have a negative association with enterprise profitability (Taneja et al. 2016). Moreover, in the contemporary world, enterprises are being driven to offer green goods and services beneficial to human health and the environment with increased environmental awareness and ecological attitudes among customers (Hwang et al. 2020; Naderi and Van Steenburg 2018). Alternatively, firms are more likely to lose market share (Tang et al. 2018).

The internalization of compliance costs brought about by environmental regulation stimulates sustainable green innovation (Feng and Chen 2018), through increasing demand in green markets, promoting enterprise sustainable green innovation, reducing energy consumption, reducing pollution emissions, reducing operating costs, forming new growth points, improving market competitiveness, and promoting industrial development and structural adjustment (Carvalho et al. 2016; Porter and Van der Linde 1995a, b; Sarkar 2013; Yin et al. 2018). It allows achieving multi-dimensional development of ecological society, enhances comprehensive research on improving economic performance (Boons et al. 2013). However, environmental performance and social performance are still the focus of long-term debate in the academic community (Zimek and Baumgartner 2017). Based on the relevant theoretical research and empirical test of “Porter hypothesis” (Guarini 2020; Ramanathan et al. 2017; Van Leeuwen and Mohnen 2017; Zefeng et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019a, b, c; Zhou et al. 2019), this paper explores the mechanism of sustainable green innovation inspiration and innovation effect generation by taking into account the government and enterprises. This paper also studies the strategic choice of government environmental regulation and enterprises sustainable green innovation by constructing an evolution game model and considering China’s case.

While studies have addressed the effect of government and market pressures on enterprises’ green innovation, their contradictory and ambiguous findings indicate that the mechanisms through which corporations achieve sustainability under environmental regulatory pressure through green innovation demand further discovery. Firstly, very few studies in a rigorous research setting have applied environmental regulations and green innovation. Most of them discuss the impact of environmental regulation on the enterprise’s innovation but do not evaluate if external influences trigger green innovation. Secondly, several studies concentrate on firms operating in developed nations worldwide, such as the USA and Europe, and few concentrates on emerging and developing countries. Thirdly, many researchers provide empirical findings to address the environmental regulation impact on a firm’s innovation. Still, very few applied the evolutionary game to study it in detail. This study examines the various aspects of environmental regulation in enterprise decisions about whether to pursue green innovation and sustainable development to overcome the discussed research gaps. Specifically, we identify four scenarios: strict environmental regulation by the government and green enterprise innovation, stringent environmental regulation by the government and enterprise, no green innovation, no environmental regulation by the government and green enterprise innovation, no environmental regulation by the government, and enterprise no green innovation.

Specifically, we have studied Chinese enterprises to achieve a green transformation to pursue sustainable development for two reasons. First, to obtain ideas from the “Xi Jinping Jinshan Yinshan Ideology”. To understand and comprehend General Secretary Xi Jinping’s speech’s true spirit, there is need to understand the relationship between ecological environment protection and economic development. Ecological, environmental protection and economic growth go hand in hand, and there is a dialectical unity between the two. Second, China’s market is much less robust and mature as a large and developing economy than developed countries such as the USA (Glaeser and Henderson 2017). Therefore, it is rational to use Chinese industrial enterprises to analyze the effect of environmental regulation on green innovation.

This research provides three significant contributions to the literature on the adoption of green innovation sustainable development practices. First, our study promotes the perception of the homogenous strategies that enterprises pursue under government regulations to invest in green innovation. This study considers the lack of environmental regulatory research and green innovation behaviors of enterprises under the resource constraint dilemma, especially in China’s case. Second, this study provides a holistic context that exposes the dynamic ties between external pressures to invest in green innovation, as environmental regulations and green innovation are typically analyzed from a static perspective (Feng and Chen 2018; Hou et al. 2018; Shen et al. 2019; Yin et al. 2018). It is challenging to conclusively research the dynamic features of environmental regulations that affect green innovation in enterprises. China’s environmental protection system is a “multi-governing system of governance” directed by the central government and regulated by the local government and enterprises (Jinyu 2020; Li et al. 2019a, b). When enterprises adopt green innovation, both central and local governments must achieve long-term equilibrium in long-term asymmetric game behavior to represent a complex dynamic evolution process (Cheng et al. 2020; Liu and Yang 2018; Yu et al. 2019). Evolutionary game theory is a useful technique for studying both government and corporations’ features since, without strict rational assumptions, it adopts the framework of evolutionary processes, allowing it to be relevant to the actual situation seen and better reflect the natural evolution process strategies of the interest groups included (Jiang et al. 2019a, b, c). Third, from the perspective of the replicator dynamic evolutionary game, the results of this study examine enterprises’ decision-making process with green innovation in the presence of strict environmental regulations put in place by the government. This paper provides a theoretical framework for ecological construction and sustainable development and promotes industrial enterprises’ growth in developing countries following green innovation.

This paper is organized as follows. The “Literature review” section provides the literature review, identifies relevant research gaps, and discusses contribution in the existing literature. In the “Model construction” section, we build a dynamic evolutionary game model, including model assumptions, parameter setting, description, and pay-off matrix construction. In the “Analysis of evolutionary game model” section, the replicated dynamic equation is established, the evolution process is analyzed, and stability analysis is carried out. Finally, the “Discussion and limitations” section presents the study’s conclusions, implications, and limitations, from which we identify avenues for future research.

Literature review

Much research is conducted to explore the relationship between environmental regulations placed by the government and its corresponding enterprise’s innovative behavior. Scholars explored diverse approaches and methodologies to observe the government’s influence on enterprises when adopting innovation practices (El-Kassar and Singh 2019; Fernando et al. 2019; Guoyou et al. 2013; Rantala et al. 2018; Silvestre and Ţîrcă 2019; Yun and Liu 2019). However, game theory is considered a practical, proven technique to examine the relationship between environmental regulations by the firms, government and environmentally friendly practices (Chen et al. 2019; Namany et al. 2019). The book is written in 1944 by John von Neuman and Oskar Morgenstern entitled “Theory of Games and Economic Behavior” laid the foundation of game theory (Johnsen). But this book is limited to define an equilibrium concept considering two-person zero-sum games. However, in the dynamic world, the explained static form of Nash equilibrium cannot be of higher significance (Gibbons 1997; Grafton et al. 2017). John Maynard Smith was the pioneer in working on evolution methodology by taking the concept from biology (Rosales 2005). The evolutionary games primarily focus on the interaction of different players, stakeholders, or groups involved (Friedman 1998; Janssen and Ostrom 2006; Traulsen and Hauert 2009).

Moreover, evolutionary game theory is based on applying the traditional mathematical model of game theory to study animal conflicts’ dynamics, just like human conflicts (Du et al. 2020; Nowak and Sigmund 2004). After the emergence of the evolutionary game theory concept, it has been widely explored to examine the environment regulations (Gao and Fan 2019; Sun and Zhang 2019), green innovation (Cui et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020a, b, c, d), and policy-making (Babu and Mohan 2020; Fan and Hui 2020). Some scholars have explored the environmental regulations and the firm’s environmental sustainability behavior using the game theory approach and provided valuable insights (Li et al. 2018a, b; Uşar et al. 2019). These researchers findings can be divided under four categories: (i) the influence of government environmental regulations on enterprises sustainable green innovation, (ii) Xi Jinping’s Jinshan Yinshan Ideology, (iii) the use of traditional games to explore government and enterprise behavior under environmental regulations to achieve environmental sustainability; and (iv) the use of evolutionary games to study government and enterprise behavior under environmental regulations to achieve environmental sustainability.

Influence of government environmental regulations on enterprises sustainable green innovation

A traditional notion indicates that environmental regulation hinders firms’ choices by encouraging enterprises to spend more in the management of emissions through minimizing their income (Adams et al. 2016; Foss et al. 1995). However, some researchers have increasingly questioned this conventional ideology. The Porter hypothesis by Professor Michael Porter primarily presented a clear viewpoint on the challenged traditional notion (Adams et al. 2016). Porter (1991) believes that technological progress can be stimulated by relevant environmental regulation, reducing costs, and enhancing the overall product quality (Porter 1991; Porter and Van der Linde 1995a, b). Also, he pioneered the win-win paradox. He proposed that by making companies well-informed and able to take advantage of other lost opportunities to stimulate innovation, environmental regulation could encourage environmental benefits and sustainability (Porter and Van der Linde 1995a, b). Many environmental studies have since checked this hypothesis (He et al. 2020; Lanoie et al. 2011; Lanoie et al. 2008; Rubashkina et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2019). The ‘pollution first, treatment later’ proposition by the Porter hypothesis development model is likely to cause problems (Ramanathan et al. 2017). External laws become more strict, enforcing even higher costs in terms of interventions and pollution penalties. Through this, corporations can continue to exploit environmental regulations and refuse to obey them. Therefore, this seems not to be a sustainable paradigm that is viable. To tackle environmental regulations and promote sustainable growth, enterprises can simultaneously carry out innovative green initiatives to meet government needs and adhere to firm’s profit maximization objective (Guo et al. 2018a, b; Tseng et al. 2013).

The development of this win-win strategy helped researchers examine the positive results of two innovation sources: process innovation and product innovation (Cherrafi et al. 2018; Rodrigues et al. 2020; Xie et al. 2019). In line with the principle of green innovation, firms are expanding sustainably not only by modifying their existing technology in manufacturing processes, but also by creating new green products (Albort-Morant et al. 2018; Awan et al. 2019; Fernando et al. 2019). Myriad ways of innovation contribute to various solutions for innovation. However, green process innovation relates to the concept of technological advancement and emissions reduction caused by manufacturing (Fernando and Wah 2017; Guo et al. 2018a, b; Yuan and Xiang 2018). This breakthrough has helped minimize resource use, facilitated the recycling of raw materials, and improved energy usage ratios (Wong et al. 2020; Xie et al. 2019). Process substitutes, therefore, result in lowering production costs and reducing emissions (Wong et al. 2020). The creation of innovative and improved goods and services requires green product innovation (Dangelico et al. 2017; Fernando et al. 2019). Such new products do not jeopardize human health, their manufacturing practices comply with environmental protection standards, and their waste is safe to regenerate and recycle resources (Gu et al. 2019). As a result, in addition to lower emission costs, commodity substitutes are primarily caused by income from the supply of green goods to markets (Jemai et al. 2020). In short, the profits that enterprises reap from green processes and product innovation would outweigh their expenses for regulation or investment in innovation (Li et al. 2019a, b; Wong et al. 2020).

The study of enterprises to achieve the green transformation to pursue sustainable development can obtain ideas from the “Smiling Curve” (Qing 2005; Shin et al. 2012). Enterprises pursue green in continuous development; we should pay attention to the process transformation in the manufacturing process, and reduce the pollution prevention cost and operation cost through green innovation, thereby increasing the added value. In different production modes, the added value curve shows the alternating smile curve. Thus, the smile curve can be expanded into a more complicated form, such as a U-shaped, inverted U-shaped (inverted smile curve) and linear type, respectively, indicating the corresponding values’ distribution under different technological innovation levels (Lin et al. 2019a, b). In general, enterprises based their research and development investment decisions on core innovations to increase enterprises’ relative added value.

According to the theoretical guidance of the smile curve model, enterprises rely on technological innovation. It effectively reduces energy consumption levels, improves production operation efficiency, reduces production costs, continuously increase product added value, and ultimately promote green transformation up-gradation to achieve sustainable development (Liu and Lin 2019; Qu et al. 2020; Yu 2019). Moreover, sustainable green innovation refers to the combination of technological, organizational, and institutional changes that can improve the ecological environment while significantly improving products (or services), production processes, organizational structures, or institutional arrangements (Adenle et al. 2019; Fernando et al. 2019; Jnr 2020). Unlike traditional technological innovation, sustainable green innovation pursues the comprehensive benefits of economic benefits, environmental benefits, and social benefits (Aboelmaged and Hashem 2019; Ge et al. 2018). Whether an enterprise innovates and adopts what type of innovation, the innovation’s performance is still affected by multiple factors. The European Union’s “Measuring Green Innovation” project considers the characteristics of green innovation, the characteristics of innovation, and the environment for innovation (market, environmental policy) (Bhatti and Sulaiman 2020; Kunapatarawong and Martínez-Ros 2016).

Also, public perception of the environment and government regulations’ enforcement are emerging as a driving force for enterprises to employ sustainability practices like green supply chain management and green innovation. The research carried out by Seman et al. (2019) presented empirical evidence by collecting data from 123 manufacturing organizations with ISO 14001 certifications using the Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) methodology. The findings demonstrated the substantial improvement of environmental performance by adopting green supply chain management and green innovation activities under the government's environmental regulations.

As a case study, Zhang et al. (2020a, b, c, d) analyzed environmental regulations and their effect on urban green innovation using Xian (China). Initially, the Slacks-based measure of directional distance functions (SBM-DDF) model was used to assess Xi’an’s green-innovation efficiency from 2003 to 2016, followed by regression testing green innovation impact under three environmental regulations, including supervision, market-based, and voluntary regulations. Empirical results show that market-based and voluntary regulations stimulate green innovation more effectively than control regulations. In contrast, environmental regulations and green innovation performance often have inverted non-linear U-shape interactions.

Feng and Chen (2018) analyze the effect of green innovation (split into green product innovation and green craft innovations) on green industrial growth, based on the theory of systemic interduality. They used the function and mechanism of environmental regulation (divided into administrative environmental regulation, market-based environmental regulation, and regulatory public participation). The empirical results from data gathered from the 30 provinces of China show that China’s overall industrial growth output has varied dramatically.

Xi Jinping’s Jinshan Yinshan ideology

The assumption that “green water and green hills are Jinshan Yinshan” is based on China’s national conditions and predicts future trends (Jia et al. 2018). It explains that despite China’s liberating and developing productive forces for a long, it is still the critical task of the principal stage of socialism, which is profoundly involved in correcting it. The assertion that “it is better to have green water and green mountains” indicates that human self-reflection and the abandonment of industrial civilization mark the arrival of the “ecological era” (Lu 2016). It contributes Eastern wisdom and the Chinese program to the community of human destiny (Shimin 2018). We should understand its rich connotation from multiple angles in the specific practice exploration of the relationship between economic development and ecological environment protection (Jinshan Yinshan, green water, and green mountains).

Building an ecological civilization is not about abandoning economic development (Geall and Ely 2018). Although ecological civilization inherently contains economic development and economic development is the proper meaning of ecological civilization, when it comes to ecological civilization construction, most of the existing literature only pays attention to green water or green mountains, ignoring and rejecting Jinshan Yinshan’s complementary effect (Zhang et al. 2018). In the modern era, harmony between man and nature is considered the basic strategy of socialism with Chinese characteristics (Jinping 2017). The socialism with Chinese characteristics that the Chinese want to build is the natural green hill and green water that can cultivate human beings’ material and spiritual civilization. For this reason, the real harmony between man and nature is the original meaning of ecological civilization. Therefore, the real ecological civilization is not to develop but to develop with low consumption, high efficiency, and high quality. We can neither seek development at the expense of the environment nor can we only talk about environmental protection at the expense of abandoning development while guarding the “green waters and green mountains”. In short, life is rich, but ecological degradation is not an ecological civilization. It is necessary to realistically balance the relationship between economic development and sustainable environmental protection, and grasp the “degree” and actively explore new ways of high-quality development based on ecological priority and sustainable green development.

Application of traditional games to explore government and enterprise behavior under environmental regulations to achieve environmental sustainability

Some scholars have researched the domain of government environmental regulations and enterprise resource constraint dilemmas. Most scholars studied environmental pollution using game theory. The first game theory used in the study of acid contamination in Europe’s trans-administrative regions was Maler (Mäler and De Zeeuw 1998). He has produced frameworks for up to 27 countries and found that “unilateral payment” is required for cooperation between countries. In the study of the strategy of the US/Mexico border water treatment scheme, (Frisvold and Caswell 2000) used game theory. Dungumaro and Madulu (2003) addressed the favorable position and relevance of the framework for public engagement to protect the environment. A game model of the pollution behavior of international duopoly countries in developing countries has been developed by (Yanase 2009). Following a comparative study of the two environmental policy instruments, namely the carbon tax and the regulation of power, he indicated that stringent pollution policies improve international companies’ competitiveness. Also, he noted that some game strategies deviate from their socially optimal level the effect of environmental policies in developing countries, and carbon tax games significantly impact the pollution and social welfare situation of developing countries.

Hottenrott and Rexhäuser (2015) claimed that tax-based environmental policy benefits enable organizations to implement innovative environmental management technologies. In contrast, advancements in environmental technology lower the amount of harm to the environment and induce a crowding effect. Under the influence of government financial interference, Hafezalkotob (2015) developed a price competition model of two supply chains, one green and one conventional. One manufacturer and one retailer are included in each supply chain. Under different decision-making mechanisms, the centralized or decentralized arrangement, they considered three different government approaches involving the supply chain materials, suppliers, and retailers. They studied the impact of government tariffs on the preferred approaches of the players. By taking into consideration the government as a critical player in the game, a Stackelberg game model was proposed to examine the influence of government financial interventions on the rivalry between two-tier supply chains, green and non-green, and to study the restriction impact of the government budget on the corporation’s environmental damage-reducing practices.

The monitoring and implementation issue between government and corporations under the green supply chain environment was modeled using a bargaining game model (Mahmoudi and Hafezalkotob 2015). Their quantitative simulation found that the costs and benefits of green supply chain management implementation and government subsidies and fines directly impact the strategies. Considering the government’s reward-penalty system, Wang et al. (2015) concluded that the greater the reward-penalty intensity, the lower the emissions level. Another game model showed that the subsidy rate has a more substantial impact than the tax rate on growing income and enhancing product sustainability (Madani and Rasti-Barzoki 2017).

Chinese scholars conducted relatively late research in this field, mainly after 2000. Early in 2001, Naixi (2001) examined the problem of pollution control by applying prisoner’s dilemma in China’s enterprises and clarified, in the context of game theory, the cause of the ‘tragedy of commons’ environmental use of public resources without government oversight (Naixi 2001). Zhao and Li (2003) explained the benefit of information asymmetries and lack of other resource limitations or incentives urge contaminants and local administrators to provide their supervisors with inaccurate information. From a game theory viewpoint, Ling (2010) looked at the topic of government environmental policy based on the knowledge gap. Another scholar studied the problems of environmental regulation and economic growth extensively and in detail, focusing on statistical and econometric approaches, game theory, and the theory of environmental economics (Wang and Chen 2010). He spoke about several concerns about conspiracy concerns in the “emission tax” control and emission auctioneers. Zhang and Liu (2013) applied game theory to research a green supply chain at three levels, where market demand corresponds with the commodity’s green value. Four different game models were constructed: cooperative decision-making, a three-level leader-follower game, Stackelberg game I, and Stackelberg game II. It followed comparing the models’ outcomes. They examine cooperative and non-cooperative conditions in a green supply chain and noticed that when all supply chain members agree to form a cooperative association, the overall profit attains the maximum level.

Zhang et al. (2019a, b, c) merged gaming and holistic governance theory to research urban agglomeration relations in China. He analyzed policies and methods to foster organized intergovernmental game governance in urban agglomerations of China. Jiang et al. (2019a, b, c) have applied extensively new economic analysis methods, such as the theory of public finances, the theory of fiscal decentralization, and game theory. They also used significant statistical evidence to support and address the inconsistency in environmental governance between tax and local governments’ control.

Application of evolutionary games to study government and enterprise behavior under environmental regulations to achieve environmental sustainability

Institutional theory is frequently used in environmental management literature to understand the external pressures which make companies greener (Bouma and van der Veen 2002; Delmas and Toffel 2004; Grob and Benn 2014; Zsidisin et al. 2005). In general, firms survive based on market ecosystems and existing stakeholders from the prevailing (Moore 1993). Other participants typically affect their behavior. Thus, enterprises must respond to changes in their external environments (Daddi et al. 2016; Damert and Baumgartner 2018; Eti-Tofinga et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018). The high level of resource consumption and environmental pollution, especially in emerging economies, outsurfaced with industrial enterprises (de Jesus Pacheco et al. 2018; Rafindadi et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2020a, b, c, d). If corporations could fairly quickly satisfy external demands by using comprehensive production models (Jennings and Zandbergen 1995; Lin et al. 2019a, b). Nevertheless, with environmental concerns growing intense, public perception of the environment’s safety has increased considerably (Alons 2017; Kang et al. 2017).

Institutional theory suggests that enterprises have to comply with existing social laws and environmental conservation beliefs to thrive (Jennings and Hoffman 2017). These laws and convictions can be reflected in formal government legislation or policies or informal conditions such as market pressures (Haslam and Godfrid 2020). Therefore, governments and markets (customers) play a crucial role in the green behavior of enterprises. The institutional theory explains why enterprises have to be green and the evolutionary theory can decide how enterprises can become green and respond to external competition changes.

The evolutionary game theory argument is grounded in life science concepts and biological evolution (Nowak and Sigmund 2004). In real-world applications, it is difficult for either enterprises or governments to behave correctly because of external and internal environments. Both corporations and governments go through a phase of observation, imitation, knowledge spillovers, and learning from each other while making decisions (Mahmood and Rufin 2005; Nieto and Quevedo 2005). To construct the dynamic replicator equation, traditional game theory expanded by incorporating the biological optimization technique, mutation mechanism, and selection mechanism (Ma and Krings 2011; Sandholm 2020). It is best suited to take this phase into account. As the outside world changes rapidly, living things must evolve instead of waiting for the ecosystem to change for them (Pique et al. 2018; Stanley 2020). The concept of “the survival of the fittest” refers to the need for biological survival and business development (von Sydow 2016). Organizations need to make adjustments to meet evolving regulations and consumer requirements (McDermott 2020). Such changes also involve the creation of new items, which can be called inventions.

Tian et al. (2014) extended a system dynamics model based on evolutionary game theory to direct subsidy policies to facilitate green supply chain management in the Chinese automotive manufacturing industry. The evolutionary game theory was used to examine the relationship between government, enterprises, and customers. Their study found that producers’ subsidies to support green supply chain management diffusion are higher than those for consumers. Moreover, in a low-carbon network environment, Chen and Hu (2018) developed a complex model of an evolutionary game between government and businesses and studied the influence of government incentives for enterprises. Barari et al. (2012) applied the evolutionary game method to research the rivalry and cooperation process between the producer and the retailer given the restricted rationality of participating participants, and searched for the balance between net profits and low-carbon production. Another scholar developed a novel dynamic carbon emission factor based on the non-linear dynamic evolution model, and developed an evolutionary game model concerning carbon emissions (Xiaomeng et al. 2015). Fan et al. (2017) built evolutionary game models based on the established small-world network structure, respectively, under conditions with and without government supervision between government and enterprises, and evaluated the optimal supervision strategy and the corresponding optimal probability of supervision.

Therefore, the evolutionary theory may predict that firm investment in green innovation could play a critical role in environmental regulation reactions. In order for businesses to invest further in technical changes to the manufacturing process or the design and production of new goods, either production processes or final products must be adaptable to change (Cooper 2019; Edeh et al. 2020; Perey et al. 2018). Nevertheless, enterprises’ primary objective is to adapt to external challenges such as government environmental regulations through green innovation to accomplish long-term sustainable growth. The evolutionary game model was based on evaluating the government’s policies in all of the above literature. The researchers typically believed that policy parameter settings are static and constant for government tax subsidies. Perhaps a few researchers proposed that the decision variables should be interpreted as government policies, set up an evolutionary game model to determine a stable evolution strategy, and introduced a unique dynamic evolutionary factor. There is still much room to study the dynamic replicator equation’s local stability under different constraint conditions by taking into account dynamic tax and subsides under bilateral dynamic modeling.

Augmented contribution to the literature

After a detailed look at the existing literature covering the diverse spectrum of government environmental regulations and enterprises’ green innovation behavior, our essential contribution is based on three dimensions. Firstly, the government and enterprises, the two-game players, are evaluated based on bounded rationality. Secondly, we have considered the government and enterprises’ equilibrium stable strategies under different scenarios. Thirdly, the available literature provides possible directions based on theoretical concepts or either the empirical findings. Significantly, few scholars have addressed this issue based on the game model, especially the replicator dynamic evolutionary game model.

Model construction

Problem description

There are massive economic and environmental shifts in China (Jiang et al. 2019a, b, c; Liang and Yang 2019; Pang et al. 2019). Economic growth has long been put above ecological sustainability by the development paradigm, rendering China one of the most polluted countries (Bekun et al. 2020; Carpio-Thomas 2020; Wu et al. 2019). However, the goals of China’s economic growth and protection of the environment have begun to change (Sun 2016; Xue et al. 2018). The government has put more focus on conserving resources and environmental sustainability (Guo et al. 2018a, b). The Chinese government specifically pointed out in the 13th Five Year Plan (2016–2020) that achieving sustainable development is essential (Wang et al. 2020a, b). The national government regularly sends monitoring teams to optimize the ecological landscape. For Chinese enterprises, environmental regulations are becoming critical, but most enterprises still doubt the effect of environmental regulations (Hou et al. 2018). Therefore, there is a compelling idea that many enterprises tend not to follow green innovation strategies to escape environmental regulations. China offers an insightful context in which scholars can examine the relationship between government environmental regulations and green innovation by enterprises.

From the above perspective, theoretical and empirical findings are based on the Porter hypothesis, smile curve modeling, and theories supporting green innovation. When the government restricts enterprises through environmental regulation, enterprises can increase investment in sustainable green research and development and actively carry out sustainable green innovation activities to meet regulatory requirements. However, there are specific case scenarios when enterprises can also accept government economic sanctions without adopting green innovation technologies. Therefore, in response to the choice of enterprises’ green innovation behavior, the government can carry out strict environmental regulations; it can either impose economic sanctions on environmental pollution in terms of fines and penalties or provide subsidies on innovative behaviors. In some cases, the government might choose to neglect environmental regulations. Thus, it is a game problem related to the government’s environmental regulation policies and enterprises’ green innovation practice.

Basic assumptions

Based on the above discussed, the following model assumptions are proposed:

Due to information asymmetry, limited rational cognition, analytical reasoning, and decision-making, both the government and enterprises are assumed bounded rational. In the evolutionary game, at the initial stages, all players of the game do not influence counter players.

The strategic space for the government is strict environmental regulations and neglected by environmental regulations. Stringent environmental regulations mean that the government has placed strict rules and laws to protect the environment, and enterprises not adhering to the government policies will fall prey to economic sanctions and penalties. In contrast, neglected environmental regulations imply no strict laws and fines imposed by the government to restrict environmental degradation. When the government chooses to have strict environmental regulations, then have to incur the cost in terms of providing government's green innovation subsidy S. When the government carries out strict environmental regulations, then enterprises also need to make green innovation investment I, to avoid the government economic sanctions against polluting enterprises W. The concentration of government environmental regulation is σ2. To cater to economic and ecological externalities, it is assumed that π1 (0 < π1 < 1) represents the economic external effect coefficient, and π2 (0 < π2 < 1) represents the ecological external effect coefficient.

The strategic space for enterprises is positive green innovation and negative green innovation. Positive green innovation refers to the enterprises incurring the cost by investing in green innovation and getting the benefit of green innovation subsidy S by the government. By having this, B is the ecological benefit of enterprises green innovation, σ1 the concentration of enterprise innovation, μ0 is the economic benefits of green innovation, λ1 (0 < λ1 < 1) is the weights of the economic indicators in the enterprise’s comprehensive performance evaluation, λ2(0 < λ2 < 1) is the weights of the ecological indicators in the enterprise’s thorough performance evaluation. In contrast, the negative green innovation refers to enterprises not adopting the green innovation investment under strict and neglected environmental regulations. Under this scenario, enterprises prefer to incur the W the economic sanctions against polluting the environment. Based on this, μ1 is the economic benefit of non-green innovation, L is the ecological environment loss caused by the enterprise’s non-green innovation.

The probability of enterprises carrying out green innovation activities is α ε [0,1] and as a function of time t. The probability of enterprises not carrying out green innovation activities is 1-α ε [0,1] and as a function of time t.

The probability of implementing strict environmental regulations by the government is β ε [0,1] and as a function of time t. The probability of neglected environmental regulations by the government is 1-β ε [0,1] and as a function of time t.

The meanings and descriptions of the specific notations used in this paper are shown in Table 1. Based on the above basic assumptions, the evolutionary game’s pay-off matrix is established, as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Major notations

| Notations | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| W | The government’s economic sanctions against polluting enterprises |

| S | The government’s green innovation subsidy |

| R | The government’s environmental regulations |

| I | The green innovation investment of the enterprise that is the economic benefit or loss that the enterprise squeezes out in the process of green innovation; it could also be referred to the opportunity cost of green innovation |

| σ1 | The concentration of enterprise innovation |

| σ2 | The concentration of government environmental regulation |

| μ0 | The economic benefits of green innovation |

| μ1 | The economic benefits of non-green innovation |

| B | The ecological benefit of the enterprise’s green innovation |

| L | The ecological environment loss caused by the company’s non-green innovation |

| λ1(0 < λ1 < 1) | The economic indicators’ weights in the enterprise’s comprehensive performance evaluation |

| λ2(0 < λ2 < 1) | The ecological indicators’ weights in the enterprise’s comprehensive performance evaluation |

| π1(0 < π1 < 1) | The economic external effect coefficient |

| π2(0 < π2 < 1) | The ecological external effect coefficient |

| α ε [0,1] | The probability of enterprises carrying out green innovation activities is α ε [0,1], and as a function of time t>. |

| β ε [0,1] | The probability of implementing strict environmental regulations by the government is β ε [0,1], and as a function of time t. |

| 1-α | The probability of negative green innovation activities |

| 1-β | The probability of the government is negligent in environmental regulation. |

Table 2.

Game payment matrix of enterprise green innovation and government environmental regulation

| Government | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strict environmental regulation (β) | Neglected by environmental regulations (1- β) | ||

| Enterprise | Positive Green innovation (α) |

−I + S + λ1μ1 + λ2B -R-S+ π1μ1+π2B |

-I + σ2S + λ1μ1+ λ2B -σ2R - σ2S + π1μ1+ π2B |

| Negative Green innovation (1- α) |

-σ1I – W + λ1μ0- σ1λ2L -R + W + π1μ0- σ1π2L |

-σ1I + λ1μ0- σ2W - σ1λ2L -σ2R + π1μ0+ σ2W - σ1π2L |

|

According to the above model assumptions and parameter descriptions, the hybrid strategy is used to summarize both players’ game payment matrix, as follows (Table 2). Based on this, it is possible to obtain the average return and replication dynamic equation for government and enterprises. Equations derived for both of the models are further explained in detail in the Appendix.

Analysis of evolutionary game model

Replicated dynamic equations and evolution stabilization strategy

In the evolutionary game, both the enterprises and government are decision-makers with limited rationality (Zhu et al. 2018). Therefore, it is difficult to obtain the optimal strategy in the initial stages. The best strategy solution is only possible with continuous trial and error game (Gao and Zhao 2020). Likewise, the equilibrium is not representing the one-time choice. Indeed, based on constant adjustments and improvement. Even after achieving the equilibrium point, it tends to deviate (Lindgren 1992). Thus, to carefully analyze and predict the game outcomes between the enterprises and government, it is suggested to adopt the most suitable methodology. The “replication dynamics” is referred as the mechanism that will simulate and depict the learning and dynamic adjustment process and based on this “evolutionary stability strategy” is considered desirable for reviewing the stability and dynamic evolutionary phases (Zhang et al. 2020a, b, c, d). This study constructs the replicated dynamic equations, which is followed by the analysis of evolutionary stabilization strategies.

It is assumed, enterprises actively carry out the expected benefits of green innovation activities by referring UG1, the expected return for green innovation is UG2, and the average expected return is UG.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Then, using Equations (1)–(3), the enterprise replication dynamic equation in the evolutionary game constructed by formula as follows:

| 4 |

By Solving

| 5 |

| 6 |

According to Equations (5) and (6), the replication dynamic system of enterprise green innovation behavior is constructed as follow:

| 7 |

| 8 |

Equilibrium point and stability analysis

Three scenarios are considered for analysis:

Analysis of enterprise evolution and stability strategy (scenario 1)

Analysis of the government's evolutionary stability strategy (scenario 2)

Stability analysis for evolutionary system strategy (scenario 3)

The possible solutions for above stated three scenarios are detailed in the Appendix.

Under scenario 1, according to the method proposed by Friedman (Friedman 1998), when F’(α) < 0, F (α∗)=0, α* is the dynamic evolutionary stability strategy (ESS), and the possible equilibrium point of the dynamic system (α∗, β∗). Based on the above model assumptions and looking into reality, when the government strengthens environmental supervision and increases the concentration of environmental regulation to a certain level, in the dynamic evolution game system, the optimal strategy choice of the enterprise is “actively carry out green innovation”. Likewise, when the government is neglected by environmental regulation, the economic penalties accepted by enterprises due to environmental pollution are less. In such a situation, the dynamic evolution game system, the optimal strategy choice of enterprises is “negative green innovation”. Moreover, when the enterprise’s positive green innovation benefits outweigh the costs, it implies that the government is higher than the strength of the enterprise’s strict environmental regulation. Therefore, enterprise’s active green innovation is a stable equilibrium strategy. And if the government’s environmental regulation is lower than the evolutionary stable equilibrium strategy is “Enterprises will not carry out green innovation”.

Under scenario 2, the government strategic choices under replication dynamic equations when it comes to different value ranges are analyzed. It explains as the probability of green innovation increases; the government gradually reduces the concentration of environmental regulation as the optimal evolution strategy. Likewise, when the probability of green innovation becomes less and less, the government increases the concentration of environmental regulation as the optimal evolution strategy.

Under scenario 3, the stability analysis for an evolutionary system strategy is viewed. The DetJ and TrJ expressions corresponding to the equilibrium points of the enterprise and government games are shown in (Table 3). The DetJ and TrJ symbols of each equilibrium points Jacobian matrix and the dynamic evolutionary game stability analysis results are shown in (Table 4) under different options as below:

φ1>0, φ3>0 (scenario 3a)

φ1>0, φ3<0 (scenario 3b)

φ1<0,φ2<0,φ3<0 (scenario 3c)

φ1<0,φ2<0,φ3>0 (scenario 3d)

φ1<0,φ2>0,φ3<0 (scenario 3e)

φ1<0,φ2>0,φ3>0 (scenario 3f)

Table 3.

Equilibrium points of the enterprise and government with Jacobian matrix DetJ and TrJ expressions

| Equilibrium points E (α, β ) | Types | Equality result |

|---|---|---|

| E1(0,0) | Det J | [-I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] (1 - σ2)(W – R) |

| Tr J | [-I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] + (1 - σ2)(W – R) | |

| E2 (0,1) | Det J | -[( 1 - σ2 )(S + W) -I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] (1 - σ2)(W – R) |

| Tr J | [( 1 - σ2 )(S + W) -I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] + (1 - σ2)(W – R) | |

| E3 (1,0) | Det J | [-I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] (1 - σ2)(S + R) |

| Tr J | -[-I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] - (1 - σ2)(S + R) | |

| E4 (1,1) | Det J | -[( 1 - σ2 )(S + W) -I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] (1 - σ2)(S + R) |

| Tr J | -[( 1 - σ2 )(S + W) -I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] + (1 - σ2) (S + R) | |

| E5 (α∗, β∗) | Det J | -(1- α∗) (1 − β∗) [-I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] (1 - σ2)(W – R) |

| Tr J | 0 |

Table 4.

The local stability analysis result

| Sr # | Condition | Equation-type/analysis result | Balance point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1(0,0) | E2 (0,1) | E3 (1,0) | E4 (1,1) | E5 (α∗, β∗) | |||

| 1 | φ1>0, φ3>0 | Det J | + | - | + | - | - |

| Tr J | + | indefinite | - | indefinite | 0 | ||

| result | Unstable | Saddle point | ESS | Saddle point | Saddle point | ||

| 2 | φ1>0, φ3<0 | Det J | - | + | + | - | + |

| Tr J | indefinite | + | - | indefinite | 0 | ||

| result | Saddle point | Unstable | ESS | Saddle point | Saddle point | ||

| 3 | φ1<0,φ2<0,φ3<0 | Det J | + | - | - | + | - |

| Tr J | - | indefinite | indefinite | + | 0 | ||

| result | ESS | Saddle point | Saddle point | Unstable | indefinite | ||

| 4 | φ1<0,φ2<0,φ3>0 | Det J | - | + | - | + | + |

| Tr J | indefinite | - | indefinite | + | 0 | ||

| result | Saddle point | ESS | Saddle point | Unstable | Saddle point | ||

| 5 | φ1<0,φ2>0,φ3<0 | Det J | + | + | - | + | - |

| Tr J | - | + | indefinite | + | 0 | ||

| result | ESS | Unstable | Saddle point | Unstable | Saddle point | ||

| 6 | φ1<0,φ2>0,φ3>0 | Det J | - | - | - | - | + |

| Tr J | indefinite | indefinite | indefinite | indefinite | 0 | ||

| result | Saddle point | Saddle point | Saddle point | Saddle point | Center point | ||

The necessary and sufficient conditions for the asymptotic stability of the system dynamic evolution are: Det (J) > 0, Tr(J) <0, unstable when Det(J)>0, Tr(J)>0 point. The DetJ and TrJ expressions corresponding to the equilibrium points of the enterprise and government games are shown in (Table 3).

The DetJ and TrJ symbols of each equilibrium point’s Jacobian matrix and the dynamic evolutionary game stability analysis results are shown in Table 3.

Under scenario 3a, when the government is neglected by environmental regulation and the net income of the enterprise actively carries out positive green innovation. Thus, the evolutionary stability strategy is when the government strictly enforces the net benefit of environmental regulation. When the government’s environmental regulation level is low, the enterprises’ active development of the net income of green innovation is positive. It will increase the enterprises’ willingness to innovate, spontaneously increase the investment in green innovation, increase the green technology research and development, improve the level of green technology, reduce the production process and pollution emissions. Even if the net income of the government’s strict environmental regulation is positive. It might be because of the high-concentration regulations, and the positive attitude of enterprises, the government’s environmental regulation will gradually decrease. It will increasingly neglect the environmental supervision of enterprises. After continuous dynamic gaming, the enterprise actively carried out green innovation activities. For the government, there is no need to improve the level of environmental regulation. If the government has higher economic penalties for enterprise ecological damage, and have an increase in the weight of ecological performance appraisal indicators in comprehensive performance appraisal. It will make it easier to motivate enterprises to actively carry out green innovation activities and take the initiative to undertake the responsibility of ecological civilization construction. At the same time, to save environmental regulation expenditures, the government gradually relaxed supervision and lowered the level of environmental regulation. It also reflects the application of Porter’s theory that explains that the cost of green innovation is not stable overtime, there is accumulation and growth of firms’ innovation capability. Therefore, based on Porter’s theory, firms benefit from green innovation and it is dependent on its relative advantage in market competition.

Under scenario 3b, the government is neglected by environmental regulation, and the net income of the enterprise actively carries out negative green innovation. Thus, the evolutionary stability strategy remains the same as in scenario 1, that is when the government strictly enforces the net benefit of environmental regulation at E3 (1,0).

Under scenario 3c, the government’s net income from environmentally regulated enterprises actively carrying out green innovation activities is negative. The government’s high-concentration environmental protection net income is negative, and the government does not conduct high-concentration in environmental regulation. There is a negative return to the enterprises’ active green innovation activities. Thus, the evolutionary stability strategy will now move at E1(0,0).

Under scenario 3d, the government’s net income from environmentally regulated enterprises actively carrying out green innovation activities is negative. The government”s high-concentration environmental protection net income is negative. Still, the government does conduct high-concentration in environmental regulation, and there is a positive return of the enterprises’ active green innovation activities. Thus, the evolutionary stability strategy will now move at E2 (0,1).

Under scenario 3e, the government’s net income from environmentally regulated enterprises actively carrying out green innovation activities is negative. The government’s high-concentration environmental protection net income is positive. Still, the government does not conduct high-concentration in environmental regulation, and there is a negative return of the enterprises’ active green innovation activities. Thus, the evolutionary stability strategy will now move at E1(0,0) as in the case of scenario 3c.

Under scenario 3f, the government’s net income from environmentally regulated enterprises actively carrying out green innovation activities is negative, the government’s high-concentration environmental protection net income is positive, and the government conducts high-concentration in the environmental regulation. There is a positive return to the enterprises’ active green innovation activities. In the dynamic game evolution system, there is no evolutionary stable equilibrium strategy between the two sides of the game, and the central point (α∗, β∗) is obtained. According to the asymmetric evolution game analysis, when the enterprise replicates the dynamic equation F(α)=0, α = 0 and α = 1 are the two stable equilibrium points of the dynamic game system. If the initial state β<β*, then α =0 is the stable equilibrium state point; otherwise, the equilibrium point is α = 1. The same reason can be analyzed by the government’s replication dynamic equations and equilibrium points. At this point, both sides of the game adopt a hybrid strategy, and the final result of the evolutionary game depends on the initial state level and the critical value (α∗, β∗) because when the government strictly controls the cost of environmental regulation, it will strengthen the level of regulation.

However, although the comprehensive benefits of actively promoting green innovation are not high, the government will face strict environmental regulations and high economic sanctions. Green innovation investment reduces pollution emissions by improving the level of green technology innovation. After a long-term dynamic evolutionary game process, it constitutes a mixed dynamic strategy between the government and the enterprise. As enterprises pay more attention to the level of ecological and environmental protection, and there is an increase in the government’s environmental regulations. The government gradually loosens the pollution supervision of enterprises; subsequently, when the company finds that the government’s environmental regulation concentration is declining and the income from negative green innovation activities is high, it will reduce green innovation investment.

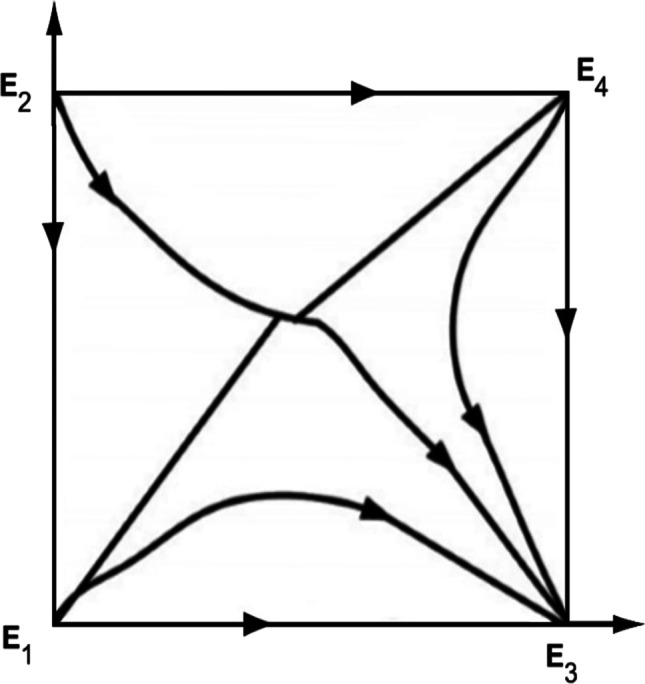

In summary, in the process of game strategy selection between the government and enterprises, the net income and β* of the enterprises actively carrying out green innovation activities play a decisive role. Therefore, it is suggested to improve the weight of eco-efficiency indicators in the comprehensive performance appraisal level of enterprises, moreover, to reduce the weight of economic benefits and increase the economic sanctions and innovation subsidies of enterprise pollution behaviors. Furthermore, to reduce the cost of regulations and innovation expenditures, and help guide enterprises to rationally allocate superior resources to enhance green enterprise innovation and take the level of innovation to the point that it achieves a win-win green sustainable development of economic performance and environmental performance. All of the above discussion is reflected in the following phase diagram of the dynamic evolution game in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Dynamic evolution game phase diagram

Discussion and limitations

Discussion

The effect of environmental regulation on green innovation is affected by factors such as regulatory policy type, strength level, green innovation technology characteristics, and performance evaluation index system for the enterprises (Borsatto and Amui 2019; Chen et al. 2017; Dong et al. 2014; Feng and Chen 2018; Wong 2013). The adoption of green innovation technology depends mainly on the size of the net income (Chen et al. 2017). When the payment of positive green innovation is greater than the negative innovation income, regardless of the concentration level of government environmental regulation, enterprises tend to increase investment in green innovation and actively carry out green innovation. If strict environmental regulation benefits are insufficient to compensate for environmental regulation expenditures, the government is neglecting environmental regulations. In the long run, the game’s initial state level based on the human rationale economics hypothesis and the incentive-constrained relationship are also important factors influencing the choice of strategy (Balbus et al. 2018).

Considering bounded rationality in the evolutionary game process, the enterprise group does not choose the game’s initial state’s optimal strategy (Chen and Hu 2018). The government environmental regulation behavior is an essential institutional constraint guiding the enterprise to carry out green innovation. The formulation of the regulatory policy should consider both short-term and long-term, mandatory and incentive, partial and holistic, post-governance and ex-ante prevention, to guide enterprises to form final behavioral decisions through continuous dynamic optimization and adjustment the dynamic game process (Corredor Waldron 2017; Fontes and Freires 2018). According to the level of comprehensive performance, the level of innovation of green innovation is determined (Peng et al. 2020; Wang and Yang 2020). The coordinated control of emission reduction and end-of-pipe management in the production process is realized (Yu et al. 2020), and the intensive and efficient green growth model is pursued, and the main synergy in the ecological environment governance change is finally realized.

On the other side of the coin developing the economy will not necessarily destroy the ecological environment. The traditional Chinese view is that economic development and environmental protection are mutually exclusive (Hu et al. 2018). The ultimate result of human economic growth is environmental pollution and ecological deterioration (Marten 2001). Moreover, to actively develop the economy, it is necessary to pay the price of decay and environmental damage. Otherwise, the economy will lose the opportunity to develop. The relationship between ecological environment protection and economic development has changed from phase to phase from a conscious act through the new economic normalization of industrialization, information development, urbanization, agricultural modernization, and urbanization. The science and technology of green, low-carbon, and circular development are fully infiltrating and fully integrated into the productive forces at a rate of every minute and every month (Yong et al. 2020; Zang and Su 2019). The formation of advanced green technologies and ecological technologies has contributed to the widespread rise of green eco-industries (Colombelli and Quatraro 2019). The foundation of this transformation is the change of the environmental protection system and management methods, maximizing the use of market economic advantages, and actively encouraging economic entities to internalize the ecological environment issues into enterprises’ decision-making process. Just as enterprises consider labor and capital costs before making decisions, variables use eco-environmental factors as a decision-making factor to promote a win-win situation for eco-environmental protection and economic development.

Ecological priority is not equal to environmental uniqueness (Liang et al. 2018). In short, the construction of ecological civilization is a complex system engineering, which requires a long-term construction process, cannot be immediate, and must act under natural laws and economic laws. It is necessary to promote the construction of ecological civilization as a systematic project, coordinate resource conservation, environmental restoration, environmental governance, and promote the organic integration of the concept of ecological civilization with the construction of economic, political, cultural, and social fields, and truly make a society based on “Jinshan Yinshan”.

Limitations

This paper provides many significant highlights on the emerging issues for a sustainable economy where there is a need to protect the environment and simultaneously cater to human needs with ever-increasing population growth over time. Therefore, this paper primarily concentrated on the relationship between the government’s environmental regulations and the enterprise green innovation behavior. However, this study has certain limitations. Firstly, this research is based on a dynamic evolutionary game theory by considering government and enterprises. The econometric empirical findings do not support the two players and their hypothesis due to panel data’s limited availability. Secondly, government environmental regulations and enterprises’ green innovation practices vary across regions and industries. For instance, some industries are less prone to generate pollution and are located in part, which is more developed. It is suggested that future researchers should conduct comparative analysis across sectors and regions. Thirdly, in this study, we have holistically considered green innovation practices rather than separately. We have also catered for green product innovation and green process innovation, which in some cases are not studied distinctively.

Conclusion, implications, and future research directions

Conclusion and policy implications

This paper tests the hypothesis using the evolutionary game model and studies the underlying behavioral characteristics of the government, enterprises, and the relevant influencing factors to analyze the process of green innovation inspiration and green innovation compensation effect after implementing environmental regulations by the Chinese government. These influencing factors further aid in examining the evolution law applicable on both sides, aligned with the dynamic replication equation and evolutionary equilibrium states under different situations. Moreover, this study’s results reflect that the system stability and equilibrium strategy on the proportion of retained earnings spent by enterprises on green innovation activities and the Government’s strict environmental regulations.

This study offers insightful ideas for having a significant environmental regulation policy and understanding of teaching enterprise sustainable green innovation capabilities to develop a new spectrum of succeeding in environmental protection through dynamic and well-coordinated economic, social and technological developments. Moreover, it should be realized that since the reform and opening up in China, with the continuous improvement of people’s material living standards and consumption levels, the people have been looking forward to “satisfaction” to “environmental protection” from “survival” to “ecology”, to high-quality ecological products (Romm 2018). The concept of “Jinshan Yinshan” is a rich development of the connotation of people’s livelihood, reflecting the response to the expectations of the masses and highlighting the people-oriented feelings of people’s livelihood. Simultaneously, the theory guiding the practice of ecological civilization construction must be accepted, understood, and welcomed by the masses.

Based on the proposed model of this study, some practical analysis at sector/industry level, firm level, and in innovation field are proposed by having environmental innovation as the dependent variable in the empirical studies and variations in the key explanatory variables.

At the industrial/sectoral level, the effects of changes in regulations with respect to sector-specific environmental innovation activities can be examined overtime. Generally, regulations are designed and applied to overall industry. However, its application, spillover effect and outcomes vary across the industrial sectors.

At firm level, applying the proposed model and testing the hypothesis would provide the evidence of decision-making behavior at firm level. It is difficult to conduct longitudinal studies due to limited data availability. However, testing the proposed scenarios in a single sector and country can possibly generate interesting findings. It might also support the argument proposed by Porter hypothesis that firms operational in highly competitive environments can only maximize the profits based on green innovation practices if they have rightfully selected the relevant competitive strategy.

Concentration on innovation aspect, as proposed in the model there can be possibly both the positive and negative externalities with respect to innovation. There are multiple domains of a product and process that can be altered. Therefore, it would be interesting for firms both on individual and sector level to compare and contrast the variations in regulation by keeping the environmental innovation constant and vice-verse.

Based on the key findings of this paper, some policy implications are proposed as follow for the decision-making authorities across the globe, which includes government, enterprises, investors, competitors, and other relevant stakeholders, etc.:

Environmental protection and sustainable development are critical aspects of accelerated economic growth. The government should play a vital role and promote the “Jinshan Yinshan” ideology by creating awareness among producers and consumers.

It is recommended that by signing off the collective understandings among the game’s involved stakeholders, there is a possibility of achieving a win-win situation by minimizing the environmental loss and maximizing the output. All the key players should be taken in the loop before imposing the governmental environmental regulation to avoid the market information asymmetry.

Based on the above proposed model, it is suggested to prioritize the role of green economies in achieving market competitive position and creating a win-win situation.

To conclude, the ecological civilization’s construction is a political declaration made by the Communist Party of China in the new historical period. It is a concrete manifestation of the party’s ruling for the people, which is the longing for the people to live a good life. It is to build a beautiful China and realize the Chinese nation its core beauty. The concrete measures for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese dream are a robust response to the masses’ voice for improving the quality of the environment. Therefore, we must closely follow the major contributions in Chinese society. Firmly grasp the new characteristics of contemporary China and global ecological civilization construction from a strategic height. By not forgetting the initial heart, keep in mind their respective mission, which regularly promotes human and nature, economic development, and ecological, environmental protection. It is one of the new modernization patterns and pathways to adopt by many developing and emerging economies with more or less similar initial conditions.

Future research direction

It is suggested for future researchers to determine the influence of environmental regulations placed by government impact on enterprise’s greens innovation behavior on long-term panel data to provide empirical evidence for the proposed hypothesis. Moreover, future studies should incorporate the regional and all industries analysis to provide a holistic review. This study is limited to China, although the topic is of global concern; therefore, it is encouraged to have comparative analysis between developed and developing economies to learn, explore, and practice better sustainable ecological development. Furthermore, the government acts as a key player by setting environmental regulations and influencing enterprises’ green innovation practices. The outbreak of Covid-19 pandemic has opened up a new dimension to deeper explore the topic as the global economy suffered from massive supply chain disruptions. There is a shift from globalization to localization, and it significantly influenced the enterprise resource constraint dilemma. It would be interesting for future researchers to explore how the environmental quality improved without imposing any stringent environmental regulations in the industrial halt during the peak of Covid-19 pandemic. However, the market forces and other stakeholders, such as investors and future pandemics should also be considered game players to develop a trilateral evolutionary game dynamic. Future studies should also conduct the simulation analysis for a better presentation of the proposed hypothesis.

Appendix

Average return and the dynamic replication equations

Hypotheses: expected return and dynamic equations

Main hypothesis

Enterprises actively carry out the expected benefits of green innovation activities is referred to as UG1, the expected return for green innovation is UG2, and the average expected return is UG.

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

Then, using equation (1-3), the enterprise replication dynamic equation in the evolutionary game constructed by formula as follows:

| 12 |

By Solving

| 13 |

| 14 |

According to equation (5) and (6), the replication dynamic system of enterprise green innovation behavior is constructed as follow:

| 15 |

| 16 |

Evolutionary and stability analysis of the game model

Analysis of enterprise’s evolutionary stability strategy (scenario 1)

When F’(α) < 0, F (α∗)=0, α* is the dynamic evolutionary stability strategy (ESS), and the possible equilibrium point of the dynamic system (α∗, β∗).According to the dynamic replication equation

| 17 |

| 18 |

By having α∗=0 or by α∗=1 , . β∗ is the corporate behavior strategy in different value ranges.

When , 0 ≤ β∗ ≤ 1 when established, F(α) ≡ 0, F’(α) = 0, is stable for all α-axis levels, indicating that all α values are balanced.

When ,F(α) = 0, then α= 0 or α = 1 is the two equilibrium state points of F(α). Evolutionary stability strategy requires F’(α) < 0, which is discussed in different situations.

When , when F’ (1) < 0, then α* =1 is the globally unique evolutionary stabilization strategy.

When , when F’ (0) < 0, at this point α*=0 is the globally unique evolutionary stabilization strategy.

If the government’s environmental regulation probability is , the probability that enterprises choose innovative strategies is stable.

-

3.

When [ I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] <0, It satisfies [I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] < λ2B, explains that the enterprise's positive green innovation benefits outweigh the costs.

-

4.

When [I (1 - σ1) + σ2(S + W) + λ1(μ1 − μ0) + λ2B + σ1λ2L] > 0, The total revenue of the enterprise's green innovation is less than the total expenditure. In case 0 < β < 1, when β < constantly established, then F’ (0) < 0, then α=0 is the optimal strategy for dynamic systems.

Analysis of the government's evolutionary stability strategy (scenario 2)

According to the government's replication dynamics equation,

| 19 |

| 20 |