Abstract

Seventy-two strains of pediococci isolated from human clinical sources were characterized by conventional physiological tests, chromogenic enzymatic tests, analysis of whole-cell protein profiles (WCPP) by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and analysis of chromosomal DNA restriction profiles by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Conventional tests allowed identification of 67 isolates: 52 strains were identified as Pediococcus acidilactici, 15 strains were identified as Pediococcus pentosaceus, and 5 strains were not identified because of atypical reactions. Analysis of WCPP identified all isolates since each species had a unique WCPP. By the WCPP method, the atypical strains were identified as P. acidilactici (two strains) and P. pentosaceus (three strains). The chromogenic substrate test with o-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside differentiated all 54 strains of P. acidilactici (negative reactions) and 13 (72%) of 18 strains of P. pentosaceus (positive reactions). Isolates of both species were shown to be nonclonal as revealed by the genetic diversity when chromosomal DNA was analyzed by PFGE. Using WCPP as the definitive identification procedure, P. acidilactici (28 of 54 strains; 51.8%) was more likely than P. pentosaceus (4 of 18 strains; 22.3%) to be isolated from blood cultures.

Pediococci are lactic acid bacteria commonly found in fermented vegetables, in dairy products, and in meat (17, 18). Although eight species of Pediococcus were listed in the last edition of the Bergey's manual (11), more recent information indicates that only five species belong to the genus: Pediococcus acidilactici, Pediococcus damnosus, Pediococcus dextrinicus, Pediococcus parvulus, and Pediococcus pentosaceus (2, 3). The association of pediococcal isolates with human infections has recently been described, but their identification in the clinical laboratory can be incorrect due, in part, to difficulties in differentiating them from physiologically similar bacteria (4, 10, 19).

Among the five recognized species, P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceus have been isolated from sterile and nonsterile sites in immunocompromised patients, but their role in the pathogenesis of infections remains unclear (5, 13, 14). Recovery of P. acidilactici is more frequent than P. pentosaceus, and P. acidilactici has also been more frequently associated with cases of invasive infections, such as bacteremia, than P. pentosaceus (13). Furthermore, the members of the genus Pediococcus, as well as some other lactic acid bacteria, such as Leuconostoc and Lactobacillus spp., are intrinsically resistant to vancomycin, a characteristic that increases the need for a correct identification of these microorganisms (8, 9).

In the present work, we characterized 72 strains of pediococci isolated from human sources by conventional physiological tests. Three chromogenic tests based on the detection of enzymatic activities were also assayed for their usefulness in differentiating the species. Analysis of whole-cell protein profiles (WCPP) obtained by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), a method used to characterize and distinguish the different species of a variety of microorganisms, such as leuconostocs, enterococci, and other lactic acid bacteria (7, 15, 16), was used to identify the species. Additionally, we evaluated the use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) as a tool for the analysis of genomic diversity. The purpose of this study was to evaluate these methodologies for the identification and characterization of the pediococcal species and to determine if there were differences between the species of pediococci and clinical sources and infections caused by these bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

A total of 72 strains isolated from human clinical sources (32 from blood, 11 from stool, 5 from peritoneal fluid, 5 from urine, 4 from wounds, 3 from abscesses, 3 from catheters, 2 from bone infections, 1 from cerebrospinal fluid, 1 from liver biopsy, 1 from vaginal secretion, and four strains from unknown sources) between 1977 and 1996 were retrieved from the culture collection of the Streptococcus Laboratory, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and included in the present study. Reference strains of the different species of pediococci (P. pentosaceus ATCC 33316, P. pentosaceus ATCC 33314 [previously considered the type strain for P. acidilactici], P. acidilactici DSM 20284 [recently designated the type strain for P. acidilactici], P. dextrinicus ATCC 33087, P. damnosus, ATCC 29358, P. parvulus ATCC 19371), as well as Aerococcus viridans (ATCC 29273), Tetragenococcus halophilus (ATCC 33315), Enterococcus solitarius (ATCC 49428), were also included.

Conventional physiological identification.

The strains were tested for their phenotypic characteristics by conventional physiological tests according to previously described procedures (9, 20). The following tests were used: Gram staining, catalase production, vancomycin susceptibility, hydrolysis of l-pyrrolidonyl-β-naphtylamide, hydrolysis of l-leucine-β-naphtylamide, hydrolysis of esculin in the presence of bile, growth in broth containing 6.5% NaCl, production of gas from glucose in Mann-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) Lactobacillus broth, hydrolysis of arginine, and acid production from arabinose, maltose, sucrose, and trehalose. Serogrouping was carried out by the slide agglutination method using the Slidex Strepto kit (bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and by capillary precipitation tests using antigen extracts obtained by the Lancefield hot acid extraction procedure and streptococcal grouping antisera prepared at the CDC.

Enzymatic tests using chromogenic substrates.

Enzymatic activities were tested by using the three following substrates linked to chromogenic compounds: p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide, o-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, and p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). Substrates were dissolved in 0.067 M Sorensen buffer (Na2HPO4 and KH2PO4) at pH 8.0 to a final concentration of 0.1%. Aliquots of 0.5 ml were distributed, and heavy bacterial suspensions were prepared directly into the solutions. The tubes were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The appearance of a strong yellow color indicated a positive reaction, as a result of the enzymatic breakage of the chromogenic substrate (12).

Analysis of WCPP by SDS-PAGE.

Preparation of whole-cell protein extracts and analysis of profiles by SDS-PAGE were performed as previously described (15), with the following modifications: the strains were grown on MRS Lactobacillus broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing 1.5% agar and 5% sheep blood instead of Columbia blood agar plates; and bacterial cells were removed from the surface of an agar plate with a inoculating loop and suspended in 5 ml of sterile saline solution in order to get a suspension with turbidity adjusted to match that of an 8 McFarland density standard, centrifuged, and resuspended in 0.25 ml of an aqueous lysozyme solution (10 mg/ml). Protein profiles of the type strains of the different species were compared according to their percentages of similarity estimated by the Dice coefficient and clustered by the unweighted pair group method with averages (UPGMA) by using the Molecular Analyst Fingerprinting Plus software package, version 1.12, of the Image Analysis System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.).

Analysis of chromosomal DNA restriction profiles by PFGE.

Preparation of genomic DNA was based in a procedure previously described (22), with a few modifications. Briefly, bacteria were grown on plates containing MRS Lactobacillus broth (Difco) supplemented with 1.5% agar and 5% sheep blood instead of Todd-Hewitt broth. Bacterial suspensions were made in 4 ml of Pett IV buffer (PIV buffer; 1.0 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6]) in order to reach the McFarland 1 turbidity standard. The cells were harvested and suspended in 0.25 ml of PIV buffer. This suspension was mixed with an equal portion of 2.0% low-melting-temperature agarose (NuSieve GTG Agarose; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) and then distributed into plug molds (Bio-Rad). For lysis, plugs were placed in 2 ml of fresh lysis solution (containing 10 mg of lysozyme and 5 U of mutanolysin per ml). After overnight incubation at 37°C with gentle shaking, this solution was replaced with 2 ml of ESP solution (0.5 M EDTA [pH 8.0], 1% sodium lauroyl sarcosine, 0.1 mg of proteinase K per ml), followed by overnight incubation at 50°C with gentle shaking. The plugs were stored in ES solution (0.5 M EDTA [pH 8.0], 1% sodium lauroyl sarcosine) at 4°C until use. Before digestion, plugs were washed four times for 1 h each with 2 ml of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 0.1 mM EDTA). The DNA in the plugs was restricted with SmaI (P. pentosaceus) or NotI (P. acidilactici), according to the manufacturer's instructions (Boehringer Mannheim Corporation, Indianapolis, Ind.). The fragments were resolved by PFGE in 1.2% agarose gels in 0.5X Tris-borate-EDTA buffer, using a CHEF-DR III system (Bio-Rad). Distinct parameters were used to resolve P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceus DNA fragments. For P. acidilactici, the initial pulse was 1.5 s, the final pulse was 25 s, and the running time was 22 h. For P. pentosaceus, the initial pulse was 2 s, the final pulse was 25 s, and the running time was 21 h. Other parameters were the same for both species: temperature (11°C), voltage gradient (6 V/cm), and included angle (120°). The gels were stained with ethidium bromide, visualized with UV light, and photographed. PFGE profiles were compared according to their percentages of similarity estimated by the Dice coefficient and clustered by UPGMA by using the Molecular Analyst Fingerprinting Plus software package, version 1.12, of the Image Analysis System (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis.

The Epi info, version 6, software (CDC) was used to analyze the distribution of pediococcal species according to the source of isolation by the chi-square test.

RESULTS

Conventional physiological identification.

The clinical isolates included in this study were catalase-negative, gram-positive cocci arranged in pairs or tetrads. They all were resistant to vancomycin, positive for l-leucine aminopeptidase activity and hydrolysis of esculin in the presence of bile, and negative for pyrrolidonyl arylamidase activity. The presence of group D antigen was a variable characteristic, occurring in 48 (67%) of the 72 isolates. Additional physiologic characteristics of the strains are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Physiological characteristics of Pediococcus strains included in this study

| Strain | Presence (+) or absence (−) of characteristic

|

No. of isolates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production of acid from:

|

Arginine hydrolysis | Salt tolerancea | |||||

| Arabinose | Maltose | Sucrose | Trehalose | ||||

| Reference strains | |||||||

| P. acidilactici | + | − | − | + | + | − | 1 |

| P. pentosaceus | + | + | − | + | + | + | 1 |

| P. dextrinicus | − | + | + | − | − | + | 1 |

| P. damnosus | − | + | + | + | − | − | 1 |

| P. parvulus | − | − | − | − | − | + | 1 |

| Clinical isolates | |||||||

| P. acidilactici | + | − | − | + | + | + | 38 |

| P. acidilactici | + | − | − | − | + | + | 13 |

| P. acidilactici | + | − | + | + | + | + | 2b |

| P. acidilactici | + | + | − | + | + | + | 1c |

| P. pentosaceus | + | + | − | + | + | + | 15 |

| P. pentosaceus | + | + | + | + | + | + | 3b |

Growth in broth containing 6.5% of NaCl.

Strains not clearly identified because of positive reactions in sucrose broth.

This strain showed typical physiological traits characteristic of P. pentosaceus. However, the protein profile, the results of the chromogenic tests, and the size range of DNA fragments were typical of P. acidilactici. DNA-DNA hybridization experiments (data not shown) confirmed its identification as P. acidilactici.

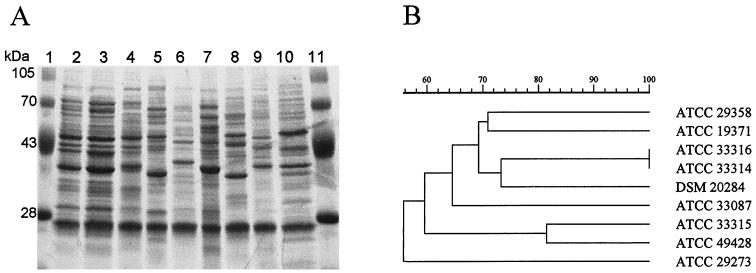

Analysis of WCPP by SDS-PAGE.

Reference strains of the five species belonging to the genus Pediococcus were clearly distinguished from each other (Fig. 1A). Reference strains of T. halophilus and A. viridans, which constitute species that had previously been considered as belonging to the genus Pediococcus, also had distinct WCPP. All of the 72 clinical isolates were identified by this method, either as P. acidilactici (54 strains) or P. pentosaceus (18 strains). The atypical isolates (sucrose positive) had protein profiles similar to that of P. acidilactici (two strains) or P. pentosaceus (three strains). If acid production from sucrose is considered a variable characteristic for these two species, all but one of the isolates (strain 1259-87) can be correctly identified as P. acidilactici or P. pentosaceus by physiological tests.

FIG. 1.

(A) SDS-PAGE profiles of whole-cell protein extracts of Pediococcus and related species. Lanes 1 and 11, molecular mass markers; lane 2, P. pentosaceus ATCC 33316; lane 3, P. pentosaceus ATCC 33314 (previously considered the type strain for P. acidilactici); lane 4, P. acidilactici DSM 20284 (recently designated the type strain for P. acidilactici); lane 5, P. dextrinicus ATCC 33087; lane 6, P. damnosus, ATCC 29358; lane 7, P. parvulus ATCC 19371; lane 8, A. viridans ATCC 29273; lane 9, T. halophilus ATCC 33315; lane 10, E. solitarius ATCC 49428. (B) Dendrogram resulting from computer-assisted analysis of the protein profiles shown in panel A. The scale represents the average percentage of similarity.

Analysis of protein profiles of the type strains resulted in a dendrogram (Fig. 1B) showing that the average percentages of similarity between strains of different species were lower than 75%. Percentages of similarity lower than 60% were found when protein profiles of Pediococcus species were compared to those of strains that belonged to the genus in the past. A percentage of similarity higher than 80% was found between the protein profiles of the type strain of T. halophilus and the type strain of E. solitarius.

Enzymatic tests using chromogenic substrates.

Enzymatic activity profiles are showed in Table 2. For practical purposes we recommend that only a strong, clear-cut, color change should be interpreted as a positive reaction. Since we considered weak changes of color as negative reactions, we found that strains belonging to P. acidilactici did not show enzymatic activity, while most of the P. pentosaceus strains had activity over the three substrates tested. However, five strains of P. pentosaceus did not show positive reactions to any substrate. Among the atypical strains (sucrose positive), the two P. acidilactici strains had negative reactions, while two of three P. pentosaceus strains had positive reactions. One maltose-positive strain (1259-87), identified as P. acidilactici by WCPP and confirmed by DNA-DNA hybridization experiments (data not shown), had typical negative reactions in all chromogenic substrates.

TABLE 2.

Differentiation of P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceus by using tests with substrates linked to chromogenic compounds

| No. of strains

|

Reactiona on substrate:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. acidilactici | P. pentosaceus | p-Nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | o-Nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | p-Nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide |

| 0 | 12 | + | + | + |

| 28 | 2 | − | − | − |

| 4 | 0 | +/− | +/− | +/− |

| 1 | 1 | − | +/− | +/− |

| 3 | 0 | − | − | +/− |

| 2 | 1 | +/− | − | − |

| 1 | 0 | +/− | +/− | − |

| 0 | 1 | − | + | − |

| 15 | 1 | − | +/− | − |

Score: −, negative reaction; +, positive reaction; +/−, weak reaction (considered negative for practical purposes).

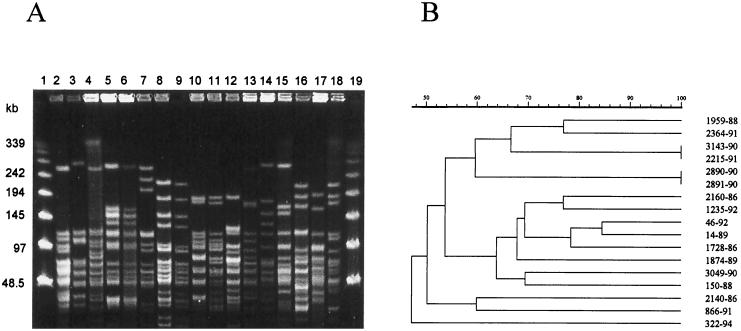

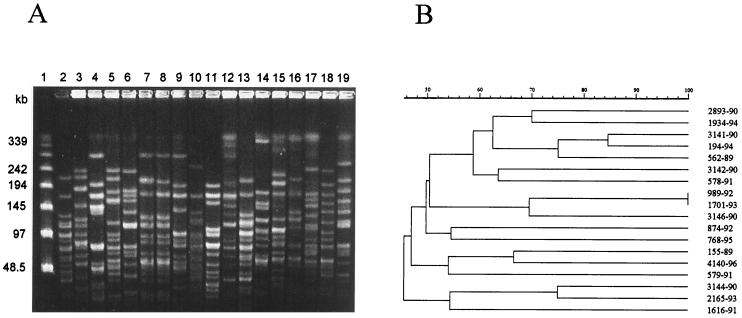

Analysis of chromosomal DNA restriction profiles by PFGE.

By using a different enzyme according to the species, 14 distinct SmaI-PFGE profiles were found among 18 strains of P. pentosaceus (Fig. 2). For P. acidilactici, 45 different NotI-PFGE profiles were found among the 49 strains tested (Fig. 3). Dendrograms generated from computer-assisted analysis of the PFGE profiles (Fig. 2B and 3B) showed no major clustering of any particular group of isolates, including those recovered from blood, that constituted the most frequent source of isolation (Table 3). The large genetic diversity probably reflected the heterogeneity of the period of time (1977 to 1996) and the geographic areas (22 states in the United States) where these strains were isolated.

FIG. 2.

(A) PFGE profiles of chromosomal DNA of P. pentosaceus strains after digestion with SmaI. Lanes 1 and 19, molecular size markers (in kilobases, lambda DNA concatemers ranging from 48.5 to 1,018.5 kb); lanes 2 to 19, clinical isolates of P. pentosaceus. Lane 2, 1728-86; lane 3, 2140-86; lane 4, 2160-86; lane 5, 3143-90; lane 6, 2215-91; lane 7, 866-91; lane 8, 2890-90; lane 2891-90; lane 10, 3049-90; lane 11, 46-92; lane 12, 150-88; lane 13, 14-89; lane 14, 1959-88; lane 15, 2364-91; lane 16, 1235-92; lane 17, 322-94; lane 18, 1874-89. (B) Dendrogram resulting from computer-assisted analysis of the PFGE profiles shown in panel A. The scale represents the average percentage of similarity.

FIG. 3.

(A) PFGE profiles of chromosomal DNA of P. acidilactici strains after digestion with NotI. Lane 1, molecular size markers; lanes 2 to 19, clinical isolates of P. acidilactici. Lane 2, 3141-90; lane 3, 3142-90; lane 4, 3144-90; lane 5, 3146-90; lane 6, 874-92; lane 7, 989-92; lane 8, 1701-93; lane 9, 2165-93; lane 10, 194-94; lane 11, 768-95; lane 12, 155-89; lane 13, 562-89; lane 14, 2893-90; lane 15, 578-91; lane 16, 579-91; lane 17, 1616-91; lane 18, 1934-94; lane 19, 4140-96. (B) Dendrogram resulting from computer-assisted analysis of the PFGE profiles shown in panel A. The scale represents the average percentage of similarity.

TABLE 3.

Clinical sources and diagnosis and/or infections associated with the Pediococcus isolates included in this study

| Clinical source | Strains associated with different clinical conditionsa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P. acidilactici

|

P. pentosaceus

|

|||

| No. (%) | Condition(s) (no. of strains) | No. (%) | Condition(s) (no. of strains) | |

| Blood | 28 (51.8) | Congestive heart failure (1), endocarditis (1), septicemia (5), peritonitis (1), peptic ulcer (1), Hickman line infection (1), bone marrow transplant (1), cellulitis (1), unknown (16) | 4 (22.3) | Coronary artery disease (1) septicemia (1), unknown (2). |

| Stool | 8 (14.8) | Diarrhea (7), unknown (1) | 3 (16.7) | Diarrhea |

| Peritoneal fluid | 4 (7.4) | Rectal carcinoma (1), fistula (1), colitis (1), peritonitis (1) | 1 (5.5) | Peritonitis |

| Abscess | 3 (5.5) | Rectal carcinoma (1), Crohn's disease (2) | ||

| Urine | 3 (5.5) | UTI (1), unknown (2) | 2 (11.1) | Unknown |

| Wound | 2 (3.7) | Enteritis (1), unknown (1) | 2 (11.1) | Pneumonia (1), unknown (1) |

| Catheter | 3 (16.7) | Abdominal surgery (1), coronary artery disease (1), unknown (1) | ||

| Bone | 1 (1.9) | Bone cyst | 1 (5.5) | Bone infection |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | 1 (1.9) | Unknown | ||

| Liver biopsy | 1 (1.9) | Liver transplant | ||

| Vaginal secretion | 1 (1.9) | Vaginitis | ||

| Unknown | 2 (3.7) | 2 (11.1) | ||

| Total | 54 | 18 | ||

UTI, urinary tract infection.

Analysis of the distribution of pediococcal species according to the source of isolation.

Isolates of both species were recovered from a variety of clinical sources (Table 3). Significant differences (P < 0.05) were only observed between rates of isolation of P. acidilactici (28 of 54 isolates; 51.8%) and P. pentosaceus (4 of 18 isolates; 22.3%) from blood.

DISCUSSION

In view of the physiological characteristics of the clinical isolates included in the present study, 52 of the 72 isolates were identified as P. acidilactici and 15 were identified as P. pentosaceus. On the basis of the results of conventional physiological tests only, the identification of five strains remained questionable because of positive reactions in sucrose broth and did not match the characteristics of the other species of pediococci. According to the current keys for differentiation and identification of Pediococcus (9), the two arabinose-positive pediococcal species (P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceus), which are the most frequently associated with human sources, should be negative for the production of acids from sucrose. However, our findings indicated that variation in this characteristic is possible among isolates of these two pediococcal species.

Analysis of WCPP obtained by SDS-PAGE proved to be a reliable tool for the differentiation and identification of Pediococcus strains since isolates of each species corresponded to a unique and distinguishable protein profile. The type strain of E. solitarius was included, since a close relationship between this species and T. halophilus has been proposed (3). The similarity between the protein profiles obtained for these two strains is an additional indication on that E. solitarius and T. halophilus are highly related and may constitute a single taxon. Also, according to the results of protein profile analysis, strain ATCC 33314 had a protein profile typical of P. pentosaceus instead of P. acidilactici. This observation is in accordance with results of DNA-DNA hybridization experiments as previously documented by other authors (1, 21). The high correlation of the results obtained by WCPP analysis with those obtained by DNA-DNA hybridization (1, 21) and 16S rRNA sequences analysis (3) indicates the effectiveness of using this phenotypic method for the identification of pediococcal species.

Results of enzymatic activity testing indicate that the three chromogenic substrates evaluated may be helpful as additional tools for differentiating the two species of pediococci that are predominant in human clinical specimens. The addition of one more test is important, since up to now the differentiation of these two species, based on physiological grounds, is related to a single characteristic (production of acid from maltose) which was shown to be variable at least in one species, although predominantly positive in P. pentosaceus and predominantly negative in P. acidilactici. We particularly recommend the test for the detection of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside because it gave one more positive reaction for P. pentosaceus strains when compared to the other two tests and because the endpoint color for a positive test was stronger, allowing better discrimination between positive (strong yellow) and negative (no color or pale yellow) results.

Analysis of chromosomal DNA restriction profiles showed a large variety of PFGE profiles, indicating the nonclonal nature of isolates belonging to either of the two species identified and demonstrating the discriminatory power of the typing procedures evaluated. It should be pointed out that the initial PFGE experiments were done with strains belonging to both species, after digestion with the same restriction endonuclease (SmaI) and under the same conditions. Chromosomal DNA from P. pentosaceus strains had profiles composed of fragments with sizes ranging from 50 to 500 kb, while P. acidilactici strains generated multiple fragments with sizes smaller than 50 kb. In an attempt to improve the reliability of P. acidilactici analysis by this technique, another rare-cutting endonuclease (NotI) was used. PFGE profiles generated by NotI were composed of fragments ranging from 50 to 500 kb, allowing better conditions for analysis of DNA restriction profiling in this species. These significant differences in the size of DNA fragments generated by a given enzyme may be related to species-specific differences in the number of restriction sites and, therefore, may be useful as markers to differentiate between species. Differences in chromosomal DNA fragments generated by PFGE were previously described for species of enterococci (6).

Among the 72 clinical isolates, 54 were identified as P. acidilactici and 18 were identified as P. pentosaceus, which yields a ratio of isolation of P. acidilactici to P. pentosaceus of 3:1. Regarding the clinical source and clinical infections, the single case of subacute bacterial endocarditis was caused by P. acidilactici. Although both pediococcal species had been isolated from different sites (Table 3), 28 (51.8%) strains of P. acidilactici were isolated from blood, in contrast with only 4 (22.3%) strains of P. pentosaceus. These differences are statistically significant (P < 0.05) and indicate that P. acidilactici is more likely to be associated with bacteremia than P. pentosaceus.

In conclusion, the present report provides data on the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of pediococcal isolates sent for identification at the CDC over an extended period of time. Despite remaining uncommon as etiological agents, these vancomycin-resistant bacteria are gaining importance as opportunistic agents associated with human infections. In clinical laboratory settings, they may still be misidentified as variants of established human pathogens, such as the enterococci, or reported as unidentified gram-positive cocci. The documentation of isolates with uncommon or atypical physiological characteristics reinforces the need for using additional methods for accurate identification of these microorganisms. In the present study, the inclusion of an additional physiological test (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside), as well as the analysis of protein profiles, were shown to be useful for the characterization of pediococcal species isolated from human sources. The use of such methods will contribute to the accurate identification and consequently to the elucidation of the role of these bacteria as infectious agents, since more precise data will be generated. These methods described for analysis of the genetic diversity may be important in clarifying aspects related to the acquisition and transmission of infections caused by these microorganisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP), and Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia (MCT/PRONEX) (Brazil).

We thank Carlos Ausberto B. de Souza and Marilene Ramos da Silva of the Instituto de Microbiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Back W, Stackebrandt E. DNS/DNS homologiestudien innerhalb der Gattung Pediococcus. Arch Microbiol. 1978;118:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosley, G. S., P. L. Wallace, C. W. Moss, A. Steigerwalt, D. Brenner, J. M. Swenson, G. A. Herbert, and R. R. Facklam. 1990. Phenotypic characterization, cellular fatty acid composition and DNA relatedness of aerococci and comparison to related genera. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:416–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Collins M D, Williams A M, Wallbanks S. The phylogeny of Aerococcus and Pediococcus as determined by 16S rRNA sequences analysis: description of Tetragenococcus gen. nov. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;70:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(05)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colman G, Efstratiou A. Vancomycin-resistant leuconostoc, lactobacilli and now pediococci. J Hosp Infect. 1987;10:1–3. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(87)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corcoran G D, Gibbons N, Mulvihill T E. Septicaemia caused by Pediococcus pentosaceus: a new opportunistic pathogen. J Infect. 1991;23:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(91)92190-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donabedian S, Chow J W, Shlaes D M, Green M, Zervos M J. DNA hybridization and contour-clamped homogeneous electric field electrophoresis for identification of enterococci to the species level. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:141–145. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.141-145.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliott J A, Facklam R R. Identification of Leuconostoc spp. by analysis of soluble whole-cell protein patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1030–1033. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1030-1033.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facklam R, Hollis D, Collins M D. Identification of gram-positive coccal and coccobacillary vancomycin-resistant bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:724–730. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.724-730.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facklam R, Elliott J A. Identification, classification and clinical relevance of catalase-negative, gram-positive cocci, excluding the streptococci and enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:479–495. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Facklam R, Pigott N, Franklin R, Elliott J. Evaluation of three disk tests for identification of enterococci, leuconostocs, and pediococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:885–887. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.885-887.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garvie E I. Genus Pediococcus. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharp M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1986. pp. 1075–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendrickson D A, Krenz M M. Reagents and stains. In: Ballows A, Hausler W I Jr, Hermann K L, Isenberg H D, Shadomy H J, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. pp. 1289–1314. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mastro T D, Spika J S, Lozano P, Appel J, Facklam R R. Vancomycin-resistant Pediococcus acidilactici: nine cases of bacteremia. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:956–960. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.5.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maugein J, Crouzit P, Mahkoul P C, Fourche J. Characterization and antibiotic susceptibility of Pediococcus acidilactici strains isolated from neutropenic patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:383–385. doi: 10.1007/BF01962083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merquior V L C, Peralta J M, Facklam R R, Teixeira L M. Analysis of electrophoretic whole-cell protein profiles as a tool for characterization of Enterococcus species. Curr Microbiol. 1994;28:149–153. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patarata L, Pimentel M S, Pot B, Kersters K, Faia A M. Identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Portuguese wines and musts by SDS-PAGE. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;76:288–293. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pederson C S. The genus Pediococcus. Bacteriol Rev. 1949;13:224–232. doi: 10.1128/br.13.4.225-232.1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raccach M. Pediococci and biotechnology. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1987;14:291–309. doi: 10.3109/10408418709104442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruoff K L, Kuritzkes D R, Wolfson J S, Ferraro M J. Vancomycin-resistant gram-positive bacteria isolated from human sources. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2064–2068. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.2064-2068.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruoff K L. Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, Stomatococcus, and miscellaneous gram-positive cocci that grow aerobically. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 306–315. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanasupawat S, Okada S, Kozaki M, Komagata K. Characterization of Pediococcus pentosaceus and Pediococcus acidilactici and replacement of the type strains of P. acidilactici with the proposed neotype DSM 20284. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:860–863. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teixeira, L. M., M. G. S. Carvalho, V. L. C. Merquior, A. G. Steigerwalt, D. J. Brenner, and R. R. Facklam. 1997. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Vagococcus fluvialis, including strains isolated from human sources. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2778–2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]