Abstract

PURPOSE:

More than half of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) experience a delay initiating guideline-adherent postoperative radiation therapy (PORT), contributing to excess mortality and racial disparities in survival. However, interventions to improve the delivery of timely, equitable PORT among patients with HNSCC are lacking. This study (1) describes the development of NDURE (Navigation for Disparities and Untimely Radiation thErapy), a navigation-based multilevel intervention (MLI) to improve guideline-adherent PORT and (2) evaluates its feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy.

METHODS:

NDURE was developed using the six steps of intervention mapping (IM). Subsequently, NDURE was evaluated by enrolling consecutive patients with locally advanced HNSCC undergoing surgery and PORT (n = 15) into a single-arm clinical trial with a mixed-methods approach to process evaluation.

RESULTS:

NDURE is a navigation-based MLI targeting barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT at the patient, healthcare team, and organizational levels. NDURE is delivered via three in-person navigation sessions anchored to case identification and surgical care transitions. Intervention components include the following: (1) patient education, (2) travel support, (3) a standardized process for initiating the discussion of expectations for PORT, (4) PORT care plans, (5) referral tracking and follow-up, and (6) organizational restructuring. NDURE was feasible, as judged by accrual (88% of eligible patients [100% Blacks] enrolled) and dropout (n = 0). One hundred percent of patients reported moderate or strong agreement that NDURE helped solve challenges starting PORT; 86% were highly likely to recommend NDURE. The rate of timely, guideline-adherent PORT was 86% overall and 100% for Black patients.

CONCLUSION:

NDURE is a navigation-based MLI that is feasible, is acceptable, and has the potential to improve the timely, equitable, guideline-adherent PORT.

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is diagnosed in 65,000 patients annually in the United States and results in 14,600 deaths per year.1 More than two thirds of patients are diagnosed with locally advanced disease,1 necessitating aggressive multimodal therapy consisting of combinations of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. For locally advanced HNSCC, National Comprehensive Care Network (NCCN) Guidelines recommend that postoperative radiation therapy (PORT) with or without concurrent chemotherapy should be initiated within 6 weeks of surgery.2 Numerous studies have demonstrated that delays starting PORT are associated with an increased risk of recurrence and mortality for patients with HNSCC.3-8 Unfortunately, more than half of White patients with HNSCC and nearly two thirds of Black patients experience a delay starting guideline-adherent PORT.7,9

Although timely, guideline-adherent PORT is critical to prevent excess mortality and racial disparities in survival, effective interventions to improve the delivery of timely, equitable PORT among patients with HNSCC are lacking.10,11 Patient navigation (PN), a patient-centered intervention that aims to eliminate barriers to health care in a culturally sensitive manner, is a potential strategy. PN has an extensive evidence base supporting its efficacy at decreasing delays and racial disparities in timely care for cancer screening, diagnostic resolution, and treatment initiation.12 However, the efficacy of PN at decreasing delays starting adjuvant therapy in sequential multimodal therapeutic paradigms is unclear.12,13 In addition, because delivering PORT for HNSCC is a complex process14 with barriers to care across multiple levels,15-17 an intervention to improve timely, guideline-adherent PORT should be multilevel in nature. Unfortunately, multilevel interventions (MLIs) to improve timely adjuvant therapy are poorly defined.18-20

The study’s objectives are to (1) describe the development of NDURE (Navigation for Disparities and Untimely Radiation thErapy), a navigation-based MLI to decrease delays and racial disparities in multimodal sequential HNSCC care and (2) evaluate its feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy.

METHODS

The study consisted of two phases. First, we developed NDURE using intervention mapping (IM).21 Second, we conducted a pilot clinical trial using a mixed-methods approach to evaluate NDURE’s feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy. The study was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Institutional Review Board and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04098458.

Development of NDURE

NDURE was developed using IM, a six-step, structured framework for developing complex health behavior change interventions (Table 1).21 In IM step 1, we created a logic model of the problem. A logic model of the problem is a graphical representation of the causal relationship between the health problem and its determinants. Our logic model of PORT delays was based on themes characterizing barriers to timely PORT that emerged from analyzing semi-structured interviews with patients (n = 27) and providers (n = 18). Barriers included the following: (1) lack of patient knowledge about guidelines for timely PORT, (2) travel burden for cancer care, (3) unclear communication between patient and providers, (4) insufficient care coordination between healthcare teams, (5) inability to track patients across fragmented healthcare systems, and (6) duplication and gaps in care resulting from ambiguity about professional roles.15

TABLE 1.

Development of NDURE Using Intervention Mappinga,21

In IM step 2, we developed our logic model of change. A logic model of change is a graphical representation specifying who and what the intervention needs to change to improve the health problem. We outlined our clinical outcome (timely PORT) and developed evidence-based behavioral outcomes for providers (eg, timely referral and scheduling of key appointments), patients (eg, timely attendance at key appointments), and the environment (eg, improved care coordination),14,17 specifying determinants for each.

On the basis of discussions with physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, and patients, we used our logic model of change to design NDURE (IM step 3).18,19,22 These discussions defined the scope as change objectives for patients, teams, and the organization. The resulting intervention sequence started with education, goal-setting, and travel support at the initial surgical consultation. The discussions indicated that a clinic-based intervention was the optimal setting, that in-person contact was the optimal delivery method, and that points of intervention contact should facilitate case identification and care transitions. Perseverance, teamwork, and racial equity were selected as program themes. NDURE’s behavior change targets included knowledge, beliefs about consequences, social support, goals, intentions, and professional roles or identity. These behavior change targets were selected from the theoretical domains framework, a cross-disciplinary framework for behavior change interventions.23 Then we aligned targeted behavior change domains with intervention components using the Behaviour Change Wheel, a framework for characterizing behavior change interventions and linking them to targeted behaviors.24 For example, the behavior change domain knowledge was mapped to the intervention component education. Finally, we selected our techniques to achieve behavior change: persuasive communication, social support, goals and planning, and organizational modeling.25

To produce NDURE (IM step 4), we refined its structure and organization as we drafted, pretested, and refined program materials. We readied NDURE for implementation (IM step 5) and finalized the evaluation plan (IM step 6). NDURE is described following the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guidelines, which aim to improve the reporting of interventions.26

Evaluation of NDURE

We conducted a pilot single-arm, nonblinded, clinical trial using a mixed-methods approach to evaluate NDURE’s feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy. The trial, guided by PRECIS-2 (PRagmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary), was pragmatic in design and intent.27 Eligibility criteria included the following: (1) > 18 years of age, (2) self-reported White or Black race, (3) HNSCC diagnosis, (4) locally advanced clinical stage, (5) plan for surgery and PORT, and (6) no history of HNSCC radiation. Patients were excluded if (1) they failed to undergo surgery or (2) final pathology revealed no indication for PORT per NCCN Guidelines.2 Consecutive potential participants were screened using the electronic medical record (EMR), identified in the MUSC HN Clinic at their initial consultation, and enrolled following informed consent. Because delays starting PORT predominantly affect Blacks, they were oversampled (22% of the MUSC HNSCC population; 33% of the trial population).

The trial’s primary end point was accrual (proportion of eligible patients who accrued), which was chosen to ensure the feasibility of a planned RCT of NDURE versus usual care (UC) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04098458). Secondary end points to evaluate feasibility included study dropout and NDURE session completion. Consistent with prior PN studies, we evaluated navigator caseload (number of simultaneous navigated cases) and time allocation (direct: time directly interacting with the patient to address barriers [eg, providing education about timely PORT]; indirect: time not directly interacting with the patient [eg, documenting PORT care plans in the EMR and calling to (re)schedule appointments or track referrals]).28 NDURE’s acceptability to patients was measured using the Satisfaction with the Interpersonal Relationship with the Navigator Scale (PSN-I; range, 9-45; higher scores represent greater satisfaction)29,30 and a study-specific program evaluation instrument that used a 5-item Likert scale to rate NDURE’s utility, delivery, and effectiveness. Intervention fidelity was evaluated using a checklist mapped to intervention functions and audits of a random selection of NDURE sessions (33%) by the first author. The primary efficacy end point was PORT delay, defined per NCCN Guidelines as starting PORT more than 6 weeks postoperatively.2

We calculated frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean, median, SD, and range for continuous variables. For the primary end point (accrual), we calculated the proportion of eligible patients who were accrued (overall, White, and Black). Qualitative analysis of open-ended interviews with patients was completed using our established codebooks that focus on the content, format, delivery, and timing of clinic-based interventions.31 Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4. Power analysis, performed using the University of Iowa Binomial Distribution applet, revealed that for the hypothesized accrual rate of 60% (minimum accrual rate to ensure the feasibility of accrual for the forthcoming RCT of NDURE versus UC), NDURE was considered feasible if ≥ 15 of 25 eligible patients enrolled. We anticipated that accrual (n = 15) would be completed within 16 weeks (0.94 patients/wk).

RESULTS

Development of NDURE

NDURE is a navigation-based MLI targeting barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT at the patient, healthcare team, and organizational levels (Fig 1). Consistent with best practices for the development and evaluation of complex interventions,32,33 key NDURE functions (the intervention’s basic purposes, in bold) and selected forms (specific strategies customized to local context necessary to carry out each function) are described below.

FIG 1.

NDURE intervention components. NDURE is a navigation-based, MLI targeting determinants of timely, guideline-adherent PORT following surgery for HNSCC with intervention components at the patient (dark blue), healthcare team (red), and organizational levels (teal). NDURE, Navigation for Disparities and Untimely Radiation thErapy; PORT, postoperative radiation therapy.

Function 1: Improve patient knowledge about Guidelines for timely PORT and associated care processes. The navigator meets face-to-face with patients at three NDURE sessions to (1) educate patients about NCCN Guidelines for timely PORT using the NDURE patient resource guide, (2) provide a personalized risk estimate of PORT delay using a validated nomogram34, (3) explain the oncologic consequences of PORT delay, and (4) describe the healthcare utilization steps necessary to start PORT.14

Function 2: Minimize the burden of travel for HNSCC care. The navigator provides patients with information about travel resources, offers travel assistance through community-based programs, and provides travel-associated financial support.

Function 3: Improve communication between patient and providers regarding intentions and goals for timely, guideline-adherent PORT. NDURE standardizes the process for initiating the discussion of the expectation for PORT as part of the treatment package (need for PORT and choice of PORT facility) to the surgical consultation (standardized timing) for all patients with locally advanced HNSCC (standardized patient population) to facilitate patient and provider goal-setting and alignment of intentions.

Function 4: Enhance coordination of care between healthcare teams during care transitions and about treatment sequelae. The NDURE navigator meets with the patient, caregiver, and HN providers at three NDURE sessions to generate (and update) a PORT care plan. The NDURE PORT care plan is an EMR-based document that (1) captures clinical factors and the care delivery processes necessary to start PORT, (2) describes the patient’s barriers to timely PORT15, and (3) documents the patient’s personalized barrier reduction plan.

Function 5: Track referrals to ensure timely scheduling of appointments and patient attendance across fragmented healthcare systems. The NDURE navigator systemically tracks referrals to ensure that clinical encounters necessary for PORT are scheduled in a timely fashion by providers, attended by patients, and rearranged as dictated by changes in the treatment timeline (eg, hospital readmission). Referral tracking is documented in an EMR-based patient timeline.

Function 6: Restructure the organization to clarify roles and responsibilities for care processes associated with PORT delivery to avoid duplication and gaps in care. The NDURE navigator is assigned sole responsibility for making all referrals and appointments to radiation and medical oncology, dentistry, and oral surgery.

NDURE is delivered by a single dedicated navigator according to the NDURE manual, which outlines the duties necessary for optimal delivery. The NDURE navigator was hired into a separate new position for the trial and selected on the basis of her social work background. Following structured, evidence-based training,35,36 the navigator was embedded within the HN surgery team, participated in weekly multidisciplinary tumor board, and coordinated with other teams involved in PORT delivery. Direct contact between the NDURE navigator and patient occurs via three clinic-based, face-to-face NDURE sessions lasting 30-60 minutes each. The three NDURE sessions coincide with the presurgical consult, hospital discharge, and first postoperative visit, time points chosen to facilitate case identification and coordination across care transitions. During each NDURE session, the navigator delivers patient education and creates or updates the PORT care plan. Referral tracking and follow-up occurs through asynchronous contact between the navigator, patient, and healthcare organizations between NDURE sessions.

Evaluation of NDURE

Fifteen eligible patients were enrolled into the trial. Overall, 67% of the participants were White, 20% had Medicaid or no health insurance, 33% lived alone, and 33% reported high school graduate as their highest level of education. Most patients had oral cavity cancer (87%), pathologic American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage IV HNSCC (93%), and underwent microvascular reconstruction (93%). Half of patients experienced fragmentation of care between the surgical and radiation facilities (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the Patients With Locally Advanced HNSCC Enrolled Into the Single-Arm Trial of NDURE (N = 15)

The rate of PORT delay, defined per NCCN Guidelines as > 6 weeks after surgery, was 14% (2/14). The two patients who experienced a delay started PORT 47 and 55 days postoperatively. One had two separate readmissions (postoperative hemorrhage and pneumonia); the other was readmitted on postoperative day 36 with a displaced gastrostomy tube and peritonitis. All the Black patients (n = 5) initiated PORT in a guideline-adherent fashion. The median time-to-PORT for the overall cohort (n = 14) was 38 days (SD, 7.71).

The accrual rate was 88% (15/17; primary end point), and accrual was completed in 19 weeks (0.79 patients/wk). No patients withdrew from the trial (n = 0). Of 15 patients enrolled, 14 (93%) completed all three NDURE sessions. One patient did not complete the final NDURE session because of a non–study-related death prior to commencing PORT. The navigator's mean caseload was 3.5 concurrent patients (range, 1-5). The mean navigator time to deliver three NDURE sessions was 231 minutes/patient (range, 210-330). Mean direct time was 96 minutes (range, 90-135), and mean indirect time was 135 minutes (range, 120-195) (Appendix Fig A1, online only). One patient required significantly more time (330 minutes overall) as a result of additional indirect time coordinating care after a readmission with a displaced gastrostomy tube and peritonitis.

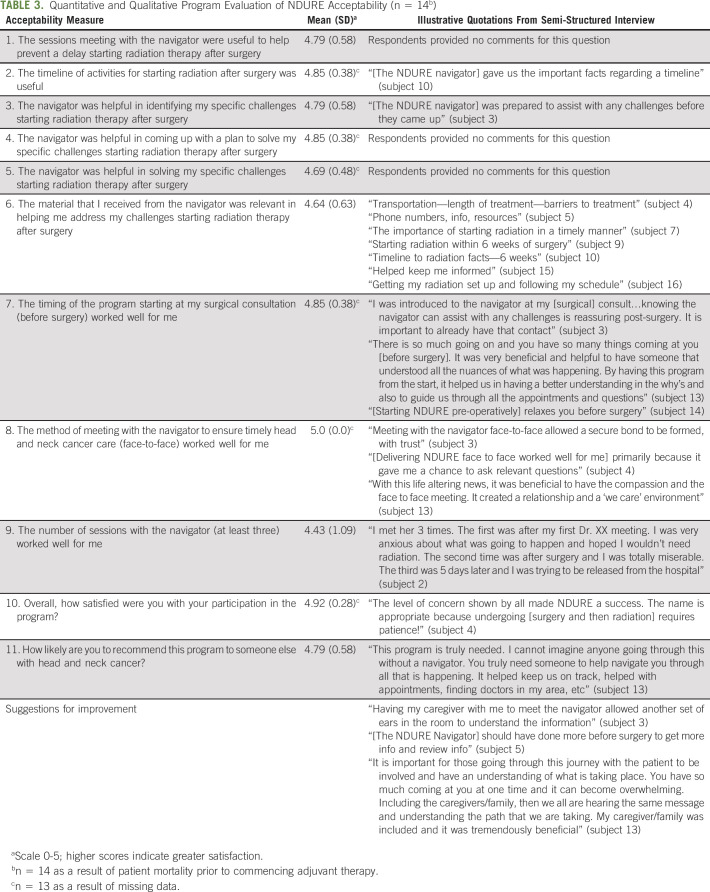

The mean PSN-I was 38 (SD, 2.9; scale from 9 to 45). Table 3 presents the acceptability data from the quantitative program evaluation and qualitative data from semi-structured interviews with NDURE participants. One hundred percent of patients reported moderate or strong agreement that the NDURE navigator was helpful in solving specific challenges starting PORT. One hundred percent of patients moderately or strongly agreed that starting NDURE at the surgical consultation was optimal. Overall, 92% of participants (12/13) were highly satisfied with NDURE and 86% of participants (12/14) were highly likely to recommend NDURE to other patients with HNSCC. The two participants who were not highly likely to recommend NDURE reported being unaware of the behind the scenes care coordination to initiate timely PORT in the setting of fragmented care across healthcare systems.

TABLE 3.

Quantitative and Qualitative Program Evaluation of NDURE Acceptability (n = 14b)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe the development of NDURE, a navigation-based MLI targeting barriers to timely, guideline-adherent PORT at the patient, healthcare team, and organizational levels. We also demonstrate that NDURE is feasible, is acceptable to patients with HNSCC, and has the potential to improve the rate of timely, equitable, guideline-adherent PORT.

One key study implication is the extension of MLI research along the cancer care continuum. Sequential multimodal cancer therapy (eg, surgical resection followed by adjuvant therapy) with timely initiation of adjuvant therapy is the dominant paradigm for numerous malignancies including HNSCC, colorectal cancer,37 breast cancer,38 and pancreatic cancer.39 Although there is a robust literature describing MLIs to improve cancer screening, treatment initiation, and survivorship care, MLI targeting barriers to timely sequential multimodal cancer care are less well-defined.18-20 The development of NDURE addresses this gap and presents key functions of an MLI that may be applied to improve the delivery of timely adjuvant therapy for other cancer types.

The program evaluation data support the feasibility and acceptability of NDURE as a clinically integrated MLI with high potential for sustained implementation. Although the sample size is small, our accrual rates (88% overall; 100% for Black participants) were high, no participants dropped out, and participants reported a high likelihood of recommending NDURE. In addition, the high accrual data in the setting of a pragmatic clinical trial recruiting consecutive patients show NDURE’s excellent reach. Although we were unable to assess adoption in this single-site design, the process evaluation data suggest that NDURE has the potential for sustained implementation outside of a clinical trial.40

Failure to deliver timely, guideline-adherent PORT is a major quality gap for HNSCC7,10,11 that affects more than 50% of patients7 and disproportionately burdens Blacks.9 Historically, the association of PORT delays with mortality has been mixed.8,41-43 However, a number of recent studies have demonstrated a strong association between delays initiating guideline-adherent PORT and overall survival for patients with HNSCC treated with modern therapeutic paradigms (eg, IMRT and adjuvant concurrent chemoradiation)3,5,7,44,45, a finding corroborated in a recent systematic review.4 Regardless of the association with mortality, PORT delays remain an important aspect of clinical care because of their influence on the perceived quality of care and association with higher rates of recurrence.6,7,41

These data suggest that NDURE has the potential to increase the rate of timely, guideline-adherent PORT for patients with HNSCC and decrease racial disparities in delay. Although the trial was not powered to detect a difference in the rate of PORT delay relative to historical controls, the observed rate of PORT delay in this trial (14%) compares favorably with published national rates (55%),9 historical data from our institution (45%),14 and data from other academic medical centers.16,17,46,47 NDURE also demonstrated promise as an intervention to decrease racial disparities in PORT delay. The rate of PORT delay among Black patients in NDURE was 0% (0/5), whereas PORT delay rates among Blacks are 65% nationally9 and 57% historically from our institution.14 On the basis of these data, NDURE merits further study as a promising intervention to decrease delays and racial disparities starting PORT.

Our study contains a number of limitations. Consistent with its pilot nature and primary feasibility end point, the study had a small sample size and single-site, single-arm design. Additional research is necessary to evaluate NDURE’s impact in a larger sample, compare NDURE with a control group to assess its efficacy, and evaluate contextual factors that influence NDURE’s implementation in other settings. The effectiveness of each NDURE component, necessity of implementing the entire bundle, and potential interaction between components (eg, synergy) are all unknown and should be explored.18 Data about NDURE’s cost are also lacking. Finally, despite recruiting patients consecutively from the clinical practice of all HN oncology providers at our institution, patients with advanced oral cavity cancer undergoing microvascular reconstruction were overrepresented. This sampling bias reflects the fact that the trial (1) excluded patients with prior RT (eg, salvage laryngectomy) and (2) only included patients planning to undergo a surgical-based paradigm (eg, two patients with oropharynx cancer who underwent surgery and PORT were not enrolled because they initially planned to undergo nonsurgical management). Although the type of patients who were overrepresented in this trial are at the highest risk for PORT delays34 (further highlighting NDURE’s efficacy), future studies should enroll a more heterogeneous distribution of HNSCC subsites.

In summary, NDURE is a navigation-based MLI targeting determinants of timely, guideline-adherent PORT following surgery for HNSCC developed using strong intervention development techniques. NDURE is feasible and acceptable to patients with HNSCC and has the potential to improve timely, equitable, guideline-adherent PORT. Additional research is necessary to evaluate fully NDURE’s efficacy and explore factors influencing its implementation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the head and neck oncology providers throughout South Carolina for their assistance in developing and refining the study intervention.

Appendix

FIG A1.

NDURE navigator time utilization. Time spent by the NDURE navigator per patient. The x-axis lists each patient sequentially by subject ID (excluding the patient who suffered a postoperative mortality) with subject 1 being the first enrolled into the trial. The height of the full bar reflects the overall time spent with each patient by the NDURE navigator, the upper portion of each bar represents the direct time (face-to-face directly interacting with the patient to address barriers; eg, providing education about timely PORT and providing travel support) and lower portion of each bar represents the indirect time (time not directly interacting with the patient; eg, documenting PORT care plans in the EMR and calling to (re)schedule appointments or track referrals). EMR, electronic medical record; NDURE, Navigation for Disparities and Untimely Radiation thErapy; PORT, postoperative radiation therapy.

Evan M. Graboyes

Other Relationship: National Cancer Institute

John M. Kaczmar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Regeneron

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented as a virtual abstract at the AACR Virtual Conference, 13th AACR Conference, The Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved.

SUPPORT

Supported by K12CA157688 and K08CA237858 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and DDCF2015209 from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to Dr Graboyes and by grant P30CA138313 from the NCI to the Biostatistics Shared Resource of the Hollings Cancer Center.

CLINICAL TRIAL INFORMATION

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Evan M. Graboyes, Katherine R. Sterba, Brian Nussenbaum, Courtney H. Marsh, David M. Neskey, John M. Kaczmar, Anand K. Sharma, Chanita Hughes-Halbert

Financial support: Evan M. Graboyes

Administrative support: Evan M. Graboyes, Jessica McCay, Courtney H. Marsh, Chanita Hughes-Halbert

Provision of study materials or patients: Evan M. Graboyes, David M. Neskey, Terry A. Day

Collection and assembly of data: Evan M. Graboyes, Katherine R. Sterba, Elizabeth A. Calhoun, Jessica McCay, Courtney H. Marsh, Jennifer Harper, Terry A. Day

Data analysis and interpretation: Evan M. Graboyes, Katherine R. Sterba, Hong Li, Graham W. Warren, Anthony J. Alberg, Elizabeth A. Calhoun, Brian Nussenbaum, Nosayaba Osazuwa-Peters, David M. Neskey, John M. Kaczmar, Jennifer Harper, Terry A. Day, Chanita Hughes-Halbert

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Development and Evaluation of a Navigation-Based, Multilevel Intervention to Improve the Delivery of Timely, Guideline-Adherent Adjuvant Therapy for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Evan M. Graboyes

Other Relationship: National Cancer Institute

John M. Kaczmar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Regeneron

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society Cancer facts & figures 2020. 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Head and Neck Cancers. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graboyes EM, Garrett-Mayer E, Ellis MA, et al. Effect of time to initiation of postoperative radiation therapy on survival in surgically managed head and neck cancer Cancer 1234841–48502017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graboyes E, Kompelli A, Neskey D, et al. Association of treatment delays with survival for patients with head and neck cancer JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145166–1772019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho AS, Kim S, Tighiouart M, et al. Quantitative survival impact of composite treatment delays in head and neck cancer Cancer 1243154–31622018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen MM, Harris JP, Orosco RK, et al. Association of time between surgery and adjuvant therapy with survival in oral cavity cancer Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1581051–10562018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer JD, Speedy SE, Ferris RL, et al. National evaluation of multidisciplinary quality metrics for head and neck cancer Cancer 1234372–43812017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ang KK, Trotti A, Brown BW, et al. Randomized trial addressing risk features and time factors of surgery plus radiotherapy in advanced head-and-neck cancer Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 51571–5782001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graboyes EM, Garrett-Mayer E, Sharma AK, et al. Adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for time to initiation of postoperative radiation therapy for patients with head and neck cancer Cancer 1232651–26602017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houlton JJ.Defining optimal treatment times in head and neck cancer care: What are we waiting for? JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145177–1782019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teng MS, Gupta V.Timely adjuvant postoperative radiotherapy: Racing to a PORT in the storm JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1441114–11152018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardo BM, Zhang X, Beverly Hery CM, et al. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient navigation programs across the cancer continuum: A systematic review Cancer 1252747–27612019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guadagnolo BA, Dohan D, Raich P.Metrics for evaluating patient navigation during cancer diagnosis and treatment: Crafting a policy-relevant research agenda for patient navigation in cancer care Cancer 1173565–35742011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janz TA, Kim J, Hill EG, et al. Association of care processes with timely, equitable postoperative radiotherapy in patients with surgically treated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1441105–11142018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graboyes E, Hughes Halbert C, Li H, et al. Barriers to the delivery of timely, guideline-adherent adjuvant therapy among patients with head and neck cancer JCO Oncol Pract 161417–14322020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sykes KJ, Morrow E, Smith JB, et al. What is the hold up?—Mixed-methods analysis of postoperative radiotherapy delay in head and neck cancer Head Neck 422948–29572020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Divi V, Chen MM, Hara W, et al. Reducing the time from surgery to adjuvant radiation therapy: An Institutional Quality Improvement Project Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 159158–1652018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Clauser SB, et al. In search of synergy: Strategies for combining interventions at multiple levels J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 201234–412012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taplin SH, Yabroff KR, Zapka J.A multilevel research perspective on cancer care delivery: The example of follow-up to an abnormal mammogram Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 211709–17152012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute Multilevel interventions in cancer care delivery: Follow-up to abnormal screening tests (R01 clinical trial optional) 2020. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/pa-17-495.html

- 21.Eldredge L, Markham C, Ruiter R, et al. Planning Health Promotion Interventions: An Intervention Mapping Approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: Understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 20122–102012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions Ann Behav Med 4681–952013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, et al. The PRECIS-2 tool: Designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ. 2015;350:h2147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: Methods, protocol, and measures Cancer 1133391–33992008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Freund KM, et al. Structural and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with cancer-related care measure: A multisite patient navigation research program study Cancer 117854–8612011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Winters PC, et al. Psychometric development and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with interpersonal relationship with navigator measure: A multi-site patient navigation research program study Psychooncology 21986–9922012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graboyes EM, Maurer S, Park Y, et al. Evaluation of a novel telemedicine-based intervention to manage body image disturbance in head and neck cancer survivors Psychooncology 291988–19942020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The New Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute P-COR Standards for studies of complex interventions. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards#Complex

- 34.Levy DA, Li H, Sterba KR, et al. Development and validation of nomograms for predicting delayed postoperative radiotherapy initiation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146455–4642020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calhoun EA, Whitley EM, Esparza A, et al. A national patient navigator training program Health Promot Pract 11205–2152010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bryant DC, Williamson D, Cartmell K, et al. A lay patient navigation training curriculum targeting disparities in cancer clinical trials J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 2268–752011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brezden-Masley C, Polenz C.Current practices and challenges of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2349–582014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chavez-MacGregor M, Clarke CA, Lichtensztajn DY, et al. Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with breast cancer JAMA Oncol 2322–3292016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ma SJ, Oladeru OT, Miccio JA, et al. Association of timing of adjuvant therapy with survival in patients with resected stage I to II pancreatic cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e199126. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM.Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework Am J Public Health 891322–13271999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang J, Barbera L, Brouwers M, et al. Does delay in starting treatment affect the outcomes of radiotherapy? A systematic review J Clin Oncol 21555–5632003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris JP, Chen MM, Orosco RK, et al. Association of survival with shorter time to radiation therapy after surgery for US patients with head and neck cancer JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144349–3592018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshak G, Popovtzer A.Is there any significant reduction of patients' outcome following delay in commencing postoperative radiotherapy? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1482–842006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tam M, Wu SP, Gerber NK, et al. The impact of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy timing on survival of head and neck cancers Laryngoscope 1282326–23322018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mazul AL, Stepan KO, Barrett TF, et al. Duration of radiation therapy is associated with worse survival in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2020;108:104819. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graboyes EM, Gross J, Kallogjeri D, et al. Association of compliance with process-related quality metrics and improved survival in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142430–4372016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graboyes EM, Townsend ME, Kallogjeri D, et al. Evaluation of quality metrics for surgically treated laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1421154–11632016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs Health Educ Q 15351–3771988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]