Abstract

PURPOSE:

Since Affordable Care Act (ACA) implementation in 2014, studies have demonstrated gains in insurance coverage for cancer survivors < 65 years. We assessed the impact of ACA implementation on financial barriers to care by stratifying survivors at age 65 years, when individuals typically become Medicare-eligible.

METHODS:

We used data from respondents with cancer in the 2009-2018 National Health Interview Survey. We identified 21,954 respondents representing approximately 7.4 million survivors, who were then age-stratified at age 65 years. Survey responses regarding financial barriers to medical care and medications were analyzed, and age-stratified multivariable logistic regression modeling was performed, which evaluated the impact of ACA implementation on these measures, adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic variables.

RESULTS:

After multivariable logistic regression, ACA implementation was associated with higher adjusted odds of Medicaid insurance (odds ratio [95% CI] 2.02 [1.72 to 2.36]; P < .0001) and lower adjusted odds of no insurance (0.57 [0.48 to 0.68]; P < .0001). Regarding financial barriers, ACA implementation was associated with lower adjusted odds of inability to afford medications (0.68 [0.59 to 0.79]; P < .0001), inability to afford dental care (0.83 [0.73 to 0.94]; P = .004), and delaying care (0.78 [0.69 to 0.89]; P = .002) in the 18-64 years group. Similarly, ACA implementation was associated with lower adjusted odds of secondary outcomes such as delaying refills, skipping doses, and anxiety over medical bills. Similar associations were not seen in the > 65 years group.

CONCLUSION:

Survivor-reported measures of financial barriers in cancer survivors age 18-64 years significantly improved following ACA implementation. Similar changes were not seen in the Medicare-eligible cohort, likely because of high Medicare enrollment and few uninsured.

INTRODUCTION

Implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) with Medicaid expansion and establishment of the health care marketplace in January 2014 radically altered the landscape of cancer care in the United States.1-3 Still, cancer survivors have greater difficulties in accessing and affording health care compared with adults without cancer.4,5 Cancer-specific financial barriers include escalating drug costs,6,7 treatment costs associated with high care utilization,8,9 and lost productivity, and unemployment because of symptoms and cancer treatment.10,11 Younger cancer survivors (18-64 years) have reduced affordability of health care compared with older survivors (> 65 years) because they generally do not qualify for Medicare absent rare exceptions and thus are more likely to be uninsured. Furthermore, younger survivors may be more reliant on their current employment income and less likely to have a safety net for significantly increased medical expenditures, rendering a catastrophic increase in expenditures from medical expenses devastating.12,13

Although ACA implementation is associated with an increase in insurance coverage and access to medical care in adult (> 18 years) cancer survivors,4,14-17 the association between the ACA and the financial burden and health care affordability experienced by survivors < 65 years is unclear. One study found that self-reported financial hardship indicators and out-of-pocket (OOP) costs decreased in survivors age 18-64 years between 2011 and 2016, whereas insurance premiums increased at the same time.18 Another study found that cancer survivors age 18-64 years with higher-income experienced significantly increased financial burden in the post-ACA period, whereas lower-income groups did not.19 Limitations of previous studies included the lack of data before 2010 to fully account for known temporal trends in affordability, difficulty in isolating the effect of the ACA on affordability, or examining all adult survivors without age stratification to control for the effects of having Medicare.4,18,19 Therefore, a better understanding of the age-related differences in the effects of ACA implementation on the financial burden of cancer survivors will inform future policy interventions.

Our study assessed survivor-reported measures of financial barriers in cancer survivors age 18-64 and > 65 years using data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), comparing pre- and post-ACA implementation periods. Previous NHIS studies had examined the impact of the ACA on all adult cancer survivors compared with control respondents without cancer, showing that cancer survivors were more likely to encounter financial barriers compared with the control population without cancer.4 However, whether this relationship holds true in the < 65 years population ineligible for Medicare and the > 65 years population eligible for Medicare remains to be studied. Thus, we focused exclusively on cancer survivors and defined age cutoffs based around Medicare eligibility. Furthermore, we present temporal trends of self-reported financial barriers from survey data across 20 years.

METHODS

The nationally representative NHIS is an ongoing, in-person, cross-sectional household survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized, and nonmilitary US population conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics. We obtained NHIS data for 1999-2018 from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series.20 The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from review as NHIS data are deidentified.

We identified 21,954 respondents age 18 years or older with self-reported previous diagnosis of cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer), representing approximately 7.4 million cancer survivors in the United States from 2009-2018. We defined 2009-2018 as the primary time period of interest as this time period covers 5 years before and after the implementation of the ACA in 2014. We stratified by age (18-64 and > 65 years) because of Medicare eligibility at 65 years. Observations were probability-weighted to produce population estimates and adjust for the combination of survey data from multiple years.

We identified and defined four primary outcomes from survey questions (data available from 1999-2018), including the inability in the past 12 months to afford necessary dental care, medications, and medical care, and having delayed necessary medical care because of cost. To further assess for the effect of ACA on insurance, we also designated two self-reported insurance statuses, Medicaid coverage and no insurance, as primary outcomes. Univariate analyses were performed for the defined study period of 2009-2018, followed by multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for factors selected a priori on the basis of the Andersen Behavioral Model.21 Models included an ACA variable dichotomized as pre-ACA (2009-2013) versus post-ACA implementation (2014-2018) and selected factors (age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education level, income level, health insurance status, health status, functional limitations, and geographic region). To account for collinearity, we included an ACA-by-time interaction variable in initial modeling; however, this variable was not statistically significant (Wald's P > .05) and was omitted from final analyses.

We conducted additional analyses to assess for differences in primary outcomes across geographic regions and time. First, as state-level data are not directly accessible via NHIS, we used the four defined geographic regions in the NHIS public use files, which all included states that did and did not expand Medicaid between 2014 and 2018.22 The multivariate modeling described above was additionally analyzed within these geographic regions. Second, to assess the significance of pre- and post-ACA findings in the broader context of longitudinal temporal trends, we collated weighted percentages of the identified primary outcomes in graphical form across 20 years of data from 1999 to 2018.

We further identified several other outcomes of financial barriers and designated them as secondary outcomes because of time-limited data availability (data only available from 2011 to 2017 or 2018). These included asked doctor for lower-cost medication, needed but could not afford necessary follow-up care, delayed refilling prescriptions to save money, worried about paying medical bills, skipped medication doses to save money, had problems in paying or unable to pay medical bills, took less medication to save money, and needed but could not afford specialist care in the past 12 months. Multivariable logistic regressions were performed on these secondary outcomes in the same manner as the primary outcomes.

All analyses were appropriately weighted and stratified for survey design. Pearson's chi-squared test with Rao-Scott correction and two-sample difference in means t-test were conducted for univariate categorical and continuous variables, respectively. P < .05 indicated statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics, 2009-2018

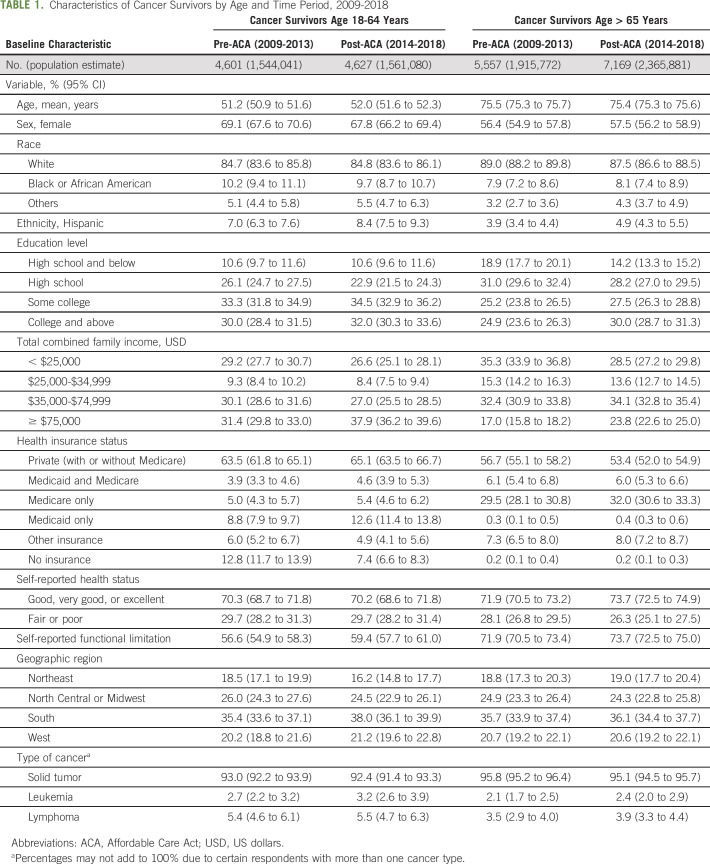

We identified 9,228 respondents with cancer age 18-64 years and 12,726 respondents with cancer age > 65 years, representing 3.1 million and 4.3 million survivors, respectively. Baseline demographics, including all the covariates selected for the multivariable models, are shown for both groups stratified by pre- (2009-2013) and post-ACA (2014-2018) time periods in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Cancer Survivors by Age and Time Period, 2009-2018

Among survivors age 18-64 years, the percentage of Medicaid-only enrollees increased from 8.8% in the pre-ACA to 12.6% in the post-ACA period. Similarly, the rate of uninsured in this cohort significantly dropped in the post-ACA period, from 12.8% to 7.4%. By contrast, the rates of Medicaid-only (0.3%-0.4%) and no insurance (0.2%- 0.2%) did not significantly change in the Medicare-eligible group.

Logistic Regression Modeling for Effect of ACA Implementation on Primary Outcomes, 2009-2018

Univariate analyses demonstrated significant associations between ACA implementation and primary outcomes in the survivors age 18-64 years group (all P = .0001 or lower; data not shown). After multivariable logistic regression adjusting for respondent demographic and socioeconomic factors (Table 2), survivors age 18-64 years were less likely, after ACA implementation, to have no insurance (OR [95% CI], 0.57 [0.48 to 0.68]; P < .0001), be unable to afford medications (0.68 [0.59 to 0.79]; P < .0001), delay care because of cost (0.78 [0.69 to 0.89]; P = .002), and be unable to afford dental care (0.83 [0.73 to 0.94]; P = .004). Inability to afford medical care did not reach statistical significance in this group, although it trended toward improvement after the ACA (0.88 [0.75 to 1.03]; P = .10). Finally, survivors in this cohort were significantly much more likely to have Medicaid insurance following ACA implementation (2.02 [1.72 to 2.36]; P < .0001).

TABLE 2.

Association of Affordable Care Act Implementation With Primary Outcomes Stratified by Age, Before and After Multivariable Adjustmenta

When assessing the same outcomes following adjustment in the Medicare-eligible group, inability to afford necessary medications worsened (1.35 [1.10 to 1.66]; P = .004) and inability to afford necessary dental care increased (1.30 [1.10 to 1.53]; P = .002). Medicaid enrollment was more likely in the post-ACA period (1.28 [1.07 to 1.52]; P = .006), whereas other assessed outcomes were not significant.

Geographic Differences in Primary Outcomes of NHIS Regions, 2009-2018

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for the primary outcomes stratified by NHIS geographic regions are shown in Figure 1. Each of the four geographic regions contained states that did and did not expand Medicaid between 2014 and 2018, the time interval from ACA implementation to the end of our study period. Within the national model, the region covariate variable was significant in five of the six primary outcomes. The corresponding ORs of the regional models were similar in magnitude to the national model, with no clear trend between the regions with a significant proportion of states that expanded Medicaid (eg, northeast) and regions with a significant proportion of states that did not (eg, south).

FIG 1.

Geographic analysis of primary outcomes in respondents age 18-64 years from 2009 to 2018, stratified by NHIS geographic regions. States in blue represent states that expanded Medicaid from 2014 to 2018. The table indicates ORs of the primary outcomes via multivariable modeling within defined geographic regions. Bold ORs indicate statistical significance with P < .05. AL, Alabama; AK, Alaska; AZ, Arizona; AR, Arkansas; CA, California; CO, Colorado; CT, Connecticut; DE, Delaware; DC, District of Columbia; FL, Florida; GA, Georgia; HI, Hawaii; ID, Idaho; IL, Illinois; IN, Indiana; IA, Iowa; KS, Kansas; KY, Kentucky; LA, Louisiana; ME, Maine; MD, Maryland; MA, Massachusetts; MI, Michigan; MN, Minnesota; MS, Mississippi; MO, Missouri; MT, Montana; NE, Nebraska; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; NV, Nevada; NH, New Hampshire; NJ, New Jersey; NM, New Mexico; NY, New York; NC, North Carolina; ND, North Dakota; OR, odds ratio; OH, Ohio; OK, Oklahoma; OR, Oregon; PA, Pennsylvania; PR, Puerto Rico; RI, Rhode Island; SC, South Carolina; SD, South Dakota; TN, Tennessee; TX, Texas; UT, Utah; VT, Vermont; VA, Virginia; VI, Virgin Islands; WA, Washington; WV, West Virginia; WI, Wisconsin; WY, Wyoming.

Temporal Trends in Primary Outcomes of Financial Barriers, 1999-2018

Weighted estimates by year for the four primary outcomes of financial barriers for the two age cohorts are shown in Figure 2. Survivors age 18-64 years experienced increased financial burden compared with Medicare-eligible survivors across the entire time period, both before and after ACA implementation. However, there was an observed significant decline in all measures in the 18-64 years cohort following ACA implementation in 2014. By contrast, rates observed for the Medicare-eligible cohort remained relatively stable in the pre- and post-ACA periods.

FIG 2.

Trends of health care unaffordability in cancer survivors from 1999 to 2018, stratified by age group.

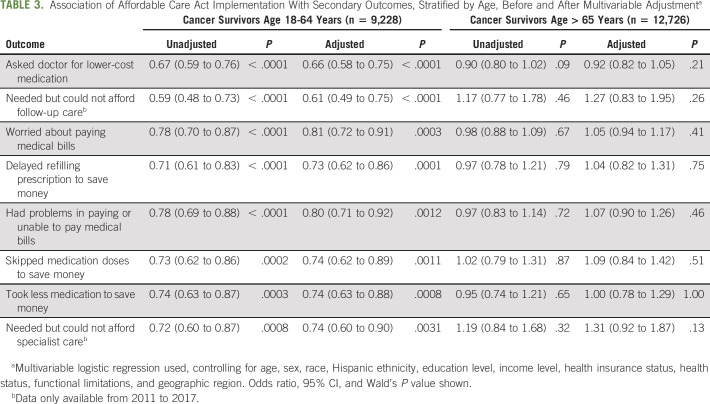

Logistic Regression Modeling for Effect of ACA Implementation on Secondary Outcomes, 2011-2017/2018

Univariate analyses demonstrated significant associations between ACA implementation and secondary outcomes in the survivors age 18-64 years group (all P = .0008 or lower; data not shown). After multivariable analysis (Table 3), survivors age 18-64 years were less likely, after ACA implementation, to ask doctors for lower-cost medication (0.66 [0.58 to 0.75]; P < .0001), not be able to afford necessary follow-up care (0.61 [0.49 to 0.75]; P < .0001), be worried about paying medical bills (0.81 [0.72 to 0.91]; P = .0003), delay refilling prescriptions to save money (0.73 [0.62 to 0.86]; P = .0001), have problems in paying medical bills (0.80 [0.71 to 0.92]; P = .0012), skip medication doses to save money (0.74 [0.62 to 0.89]; P = .0011), take less medication to save money (0.74 [0.63 to 0.88]; P = .0008), and need but could not afford specialist care (0.74 [0.60 to 0.90]; P = .0031). Conversely, none of these outcomes exhibited a significant change in the Medicare-eligible population after ACA implementation.

TABLE 3.

Association of Affordable Care Act Implementation With Secondary Outcomes, Stratified by Age, Before and After Multivariable Adjustmenta

DISCUSSION

In a nationally representative sample of cancer survivors, the post-ACA implementation period is associated with a significant reduction in reported financial barriers to care among younger cancer survivors (18-64 years) who were predominantly not covered by Medicare. Survivors in this cohort reported significantly decreased inability to afford medications, medical care, and dental care after ACA implementation. Furthermore, they had less trouble in affording medication and were less likely to skip doses or delay refills after ACA implementation. Finally, they were also less likely to be worried or have problems in paying medical bills following ACA implementation.

There was a significant decrease in the proportion of cancer survivors age 18-64 years lacking insurance coverage following ACA implementation. At the same time, an increase in Medicaid enrollment in this group was seen. Our findings concur with previous studies that ACA implementation increased insurance coverage in cancer survivors1,4 and extend research by quantifying the decreases in indicators of financial hardship and burden in cancer survivors age 18-64 years following ACA implementation and showing that the decreases are sustained for several years following 2014.18,19

Financial burden, also termed financial toxicity, can be understood in cancer survivors on the basis of two components—objective financial burden and subjective financial distress.23 Our results demonstrate that patient-reported outcomes of health care affordability (related to objective burden of cancer care) decreased in the post-ACA implementation period. Subjective financial distress also decreased, as evidenced by the reduction in anxiety over paying medical bills. This is notable in light of the reported more than two million cancer survivors who skipped necessary medical services because of cost in the pre-ACA period.24 Using our population estimates for reference and comparing between pre- and post-implementation periods, the ACA improved the affordability of medical care and medication for an estimated 57,000 and 92,000 cancer survivors who may not be Medicare-eligible, respectively.

Several outcome measures that we assessed reflect medication access and cost. The cost of novel oral oncologic therapy in the United States is significantly higher than that of other countries, and patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy incur nearly four times per-person costs of those not receiving chemotherapy.5,25 Furthermore, younger cancer survivors are more likely to alter their prescription drug use compared with elderly cancer survivors and those without a cancer history.26 Medicaid expansion increased access to health care resources, including prescription drugs, in previously uninsured survivors,27 and our findings broadly reflect this trend. Previous research on the increase of copayments on Medicaid cancer survivors showed that they were especially susceptible to OOP costs.28 Economically under-resourced individuals will modify their health-seeking behavior according to cost; our findings may reflect the alleviation of financial burden because of previously uninsured younger cancer survivors acquiring coverage.18,29-31

We did not see significant changes in most of the outcomes from pre- to post-ACA implementation periods in the Medicare-eligible (> 65 years) cancer survivor group, likely owing to overwhelmingly high Medicare enrollment, which did not significantly change across studied time periods. Demonstrated increasing inability to afford dental care in the Medicare population was likely due to escalating costs of dental care over time, compounded by traditional Medicare not covering outpatient dental care.32,33 The observed inability to afford medications in the Medicare-eligible in the post-ACA era is more complex, as the closing of the Medicare Part D doughnut hole as a provision of the ACA34 should work to alleviate medication cost burden in this population. However, the ACA failed to cap cost sharing in the Part D catastrophic coverage phase, which can potentially negate the savings achieved by the reduction of the doughnut hole coverage gap, especially as novel oral cancer therapy becomes increasingly common and expensive.35-37 Unfortunately, our model using survey data cannot capture this degree of complexity or whether the medications mentioned by respondents are specifically oncologic; thus, further study is warranted.

Although the ACA included important national provisions such as establishment of state health insurance exchanges, individual premium subsidies, employer mandates, and payment reforms,1,38 Medicaid expansion was adopted on state level.39,40 Although the NHIS public use data do not allow for a direct comparison between Medicaid expanded and nonexpanded states, analysis of the NHIS regions, which included a mixture of both types of states, did not demonstrate a significant impact of geography on study outcomes. This indicates that the overarching effects of the ACA may be greater than those of Medicaid expansion on the state level alone or that a regional analysis is not sensitive enough to capture these differences. Nonetheless, the concordance of the region-specific ORs to that of the national model suggests that there were no clear geographic disparities among the four regions in regard to the primary outcomes.

We present a longitudinal view of temporal trends for the assessed primary outcomes of financial barriers across 20 years from 1999 to 2018 (Fig 2). Because of the wide array of confounders including political, economic, and demographic changes over such an extended period, we believe that quantitative analyses may be misleading, but there is merit in examining long-term trends. We found that younger (18-64 years) cancer survivors have always experienced a greater degree of financial burden compared with those who are Medicare-eligible (> 65 years) and the demonstrated improvement in these measures, as shown by declines in the post-ACA implementation period (2014-2018), is especially notable. In this group, ACA implementation appears to have contributed to the decrease of financial barriers to the lowest estimated levels in 20 years and significantly offset increased medical financial burden because of insurance instability during the Great Recession period (2007-2009).41 By contrast, measures of financial barriers remained relatively stable for the Medicare-eligible population. Whether these improvements persist remains to be seen, especially with the abolishment of the ACA individual mandate in 2017, ongoing legal challenges to the ACA, and economic fallout secondary to the novel coronavirus pandemic.42-44

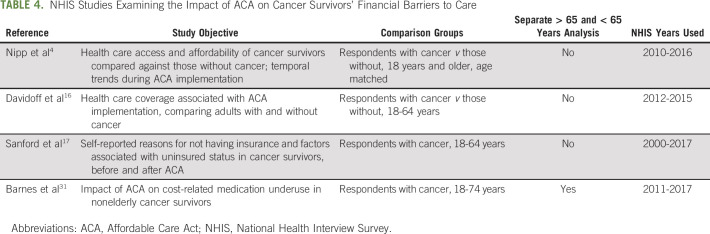

Our study extends previous work by directly comparing the impact of ACA implementation on reported financial barriers in cancer survivors age 18-64 years against those age > 65 years. Previous NHIS studies had not been able to fully examine this relationship because of selection of control group without cancer,4,16 lack of age stratification,4,16,17 or limited follow-up interval following implementation (Table 4).4,16 We used multivariable logistic regression to directly measure the contribution of ACA implementation via assessment of the pre- and post-ACA periods, 5 years before and after ACA implementation in 2014. Subsequently, these findings were placed within the context of geography and long-term trends across 20 years. The composite results underscore the marked impact that the ACA has had on drastically changing long-standing financial barriers to care in cancer survivors < 65 years.

TABLE 4.

NHIS Studies Examining the Impact of ACA on Cancer Survivors' Financial Barriers to Care

There were several limitations to the study. First, NHIS is based on self-reported outcomes and there is no direct linkage to objective financial measures. However, patient-reported outcomes relating to financial burden are validated measures and provide an additional layer of patient-level adjustment not captured in quantitative dollar measures of OOP cost.18,45 Second, the data set is cross-sectional and not a longitudinal cohort, so only population associations across distinct timepoints can be reported. Significantly, we did not have medical information regarding cancer type, stage, or treatment received, which directly affects health care expenditure over time. Finally, it was not possible to differentiate between cancer-specific and general medical care; thus, we were unable to attribute changes in outcomes directly to cancer care. However, the ACA has demonstrated impact beyond cancer care in survivors,46 and the reported outcomes provide a global snapshot of the challenges faced by a vulnerable population chronically experiencing high health care expenditures.46,47

In conclusion, in a nationally representative sample of cancer survivors, ACA implementation was associated with significant reduction in financial barriers to care of cancer survivors age 18-64 years with increased rates of having health insurance and reduced inability to afford needed medical treatment and medications. Corresponding reductions were not evident in cancer survivors age > 65 years.

Susan D. Goold

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: A simulation exercise (CHAT) that I coinvented, when others pay to use it, results in royalties to me, my coinventor, and our institutions. My own royalty receipts in the past 2 years have been < $1,000 USD

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

C.T.S. was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (T32-CA-236621).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Christopher T. Su, Dolorence Okullo, Deborah A. Levine, Susan D. Goold

Administrative support: Deborah A. Levine, Susan D. Goold

Collection and assembly of data: Christopher T. Su, Dolorence Okullo, Stephanie Hingtgen

Data analysis and interpretation: Christopher T. Su, Dolorence Okullo

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Affordable Care Act and Cancer Survivors’ Financial Barriers to Care: Analysis of the National Health Interview Survey, 2009-2018

The following represents disclosure information provided by the authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Susan D. Goold

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: A simulation exercise (CHAT) that I coinvented, when others pay to use it, results in royalties to me, my coinventor, and our institutions. My own royalty receipts in the past 2 years have been < $1,000 USD

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhao J, Mao Z, Fedewa SA, et al. The Affordable Care Act and access to care across the cancer control continuum: A review at 10 years CA Cancer J Clin 70165–1812020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikpay SS, Tebbs MG, Castellanos EH.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion and gains in health insurance coverage and access among cancer survivors Cancer 1242645–26522018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Lin CC, Davidoff AJ, et al. Changes in insurance coverage and stage at diagnosis among nonelderly patients with cancer after the Affordable Care Act J Clin Oncol 353906–39152017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nipp RD, Shui AM, Perez GK, et al. Patterns in health care access and affordability among cancer survivors during implementation of the Affordable Care Act JAMA Oncol 4791–7972018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nardi EA, Wolfson JA, Rosen ST, et al. Value, access, and cost of cancer care delivery at academic cancer centers J Natl Compr Canc Netw 14837–8472016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seymour EK, Ruterbusch JJ, Winn AN, et al. The costs of treating and not treating patients with chronic myeloid leukemia with tyrosine kinase inhibitors among Medicare patients in the United States Cancer 12793–1022021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winn AN, Keating NL, Dusetzina SB.Factors associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor initiation and adherence among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic myeloid leukemia J Clin Oncol 344323–43282016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang X, Laliberté F, Germain G, et al. Real-world characteristics, treatment patterns, healthcare resource use and costs of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the United States Oncologist 26e817–e8262021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vyas A, Madhavan SS, Sambamoorthi U, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs during the initial phase of care among elderly women with breast cancer J Natl Compr Canc Netw 151401–14092017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bubis LD, Davis L, Mahar A, et al. Symptom burden in the first year after cancer diagnosis: An analysis of patient-reported outcomes J Clin Oncol 361103–11112018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Boer AG, Taskila T, Ojajärvi A, et al. Cancer survivors and unemployment: A meta-analysis and meta-regression JAMA 301753–7622009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehnert A.Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 77109–1302011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han X, Zhao J, Zheng Z, et al. Medical financial hardship intensity and financial sacrifice associated with cancer in the United States Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 29308–3172020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soni A, Sabik LM, Simon K, et al. Changes in insurance coverage among cancer patients under the Affordable Care Act JAMA Oncol 4122–1242018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss HA, Havrilesky LJ, Zafar SY, et al. Trends in insurance status among patients diagnosed with cancer before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act JCO Oncol Pract 14e92–e1022018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidoff AJ, Guy GP, Hu X, et al. Changes in health insurance coverage associated with the Affordable Care Act among adults with and without a cancer history: Population-based national estimates Med Care 56220–2272018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sanford NN, Lam MB, Butler SS, et al. Self-reported reasons and patterns of noninsurance among cancer survivors before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act, 2000-2017. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:e191973. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong YR, Smith GL, Xie Z, et al. Financial burden of cancer care under the Affordable Care Act: Analysis of MEPS-experiences with cancer survivorship 2011 and 2016 J Cancer Surviv 13523–5362019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segel JE, Jung J.Coverage, financial burden, and the patient protection and Affordable Care Act for patients with cancer JCO Oncol Pract 15e1035–e10492019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.IPUMS http://www.ipums.org

- 21. Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services use: A systematic review of studies from 1998-2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012;9:Doc11. doi: 10.3205/psm000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Geocodes; 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/rdc/geocodes/geowt_nhis.htm [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS.The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: Understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment CA Cancer J Clin 68153–1652018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, et al. Forgoing medical care because of cost: Assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States Cancer 1163493–35042010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savage P, Mahmoud S, Patel Y, et al. Cancer drugs: An international comparison of postlicensing price inflation JCO Oncol Pract 13e538–e5422017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng Z, Han X, Guy GP, et al. Do cancer survivors change their prescription drug use for financial reasons? Findings from a nationally representative sample in the United States Cancer 1231453–14632017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahendraratnam N, Dusetzina SB, Farley JF.Prescription drug utilization and reimbursement increased following state Medicaid expansion in 2014 J Manag Care Spec Pharm 23355–3632017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subramanian S.Impact of Medicaid copayments on patients with cancer: Lessons for Medicaid expansion under health reform Med Care 49842–8472011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winkelman TNA, Segel JE, Davis MM.Medicaid enrollment among previously uninsured Americans and associated outcomes by race/ethnicity-United States, 2008-2014 Health Serv Res 54297–3062019suppl 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer 1193710–37172013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes JM, Johnson KJ, Adjei Boakye E, et al. Impact of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on cost-related medication underuse in nonelderly adult cancer survivors Cancer 1262892–28992020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willink A, Schoen C, Davis K.Dental care and Medicare beneficiaries: Access gaps, cost burdens, and policy options Health Aff (Millwood) 352241–22482016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hung M, Lipsky MS, Moffat R, et al. Health and dental care expenditures in the United States from 1996 to 2016. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shrank WH, Choudhry NK.Time to fill the doughnuts—Health care reform and Medicare Part D N Engl J Med 364598–6012011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trish E, Xu J, Joyce G.Medicare beneficiaries face growing out-of-pocket burden for specialty drugs while in catastrophic coverage phase Health Aff (Millwood) 351564–15712016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon MS, Cole AL, Dusetzina SB.Out-of-Pocket spending under the Affordable Care Act for patients with cancer Cancer J 23175–1802017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wineinger NE, Zhang Y, Topol EJ. Trends in prices of popular brand-name prescription drugs in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e194791. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chernew ME, Conway PH, Frakt AB.Transforming Medicare's payment systems: Progress shaped by the ACA Health Aff (Millwood) 39413–4202020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Colditz GA, Kozower BD, et al. Association of Medicaid expansion under the patient protection and Affordable Care Act with non-small cell lung cancer survival JAMA Oncol 61289–12902020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moss HA, Wu J, Kaplan SJ, et al. The Affordable Care Act's Medicaid expansion and impact along the cancer-care continuum: A systematic review J Natl Cancer Inst 112779–7912020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gai Y, Jones K. Insurance patterns and instability from 2006 to 2016. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:334. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05226-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiedler M.The ACA's individual mandate in retrospect: What did it do, and where do we go from here? Health Aff (Millwood) 39429–4352020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agarwal SD, Sommers BD.Insurance coverage after job loss—The importance of the ACA during the covid-associated recession N Engl J Med 3831603–16062020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moss HA, Han X, Yabroff KR, et al. Declines in health insurance among cancer survivors since the 2016 US elections. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e517. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30623-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) Cancer 123476–4842017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Angier HE, Marino M, Springer RJ, et al. The Affordable Care Act improved health insurance coverage and cardiovascular-related screening rates for cancer survivors seen in community health centers Cancer 1263303–33112020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guy GP, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, et al. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States J Clin Oncol 313749–37572013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]