Abstract

Purpose:

Childhood adversity is associated with adverse health outcomes, in part due to its effects on healthy lifestyle. We examined whether psychological resilience to adversity may promote healthier behaviors and body weight in young adulthood.

Methods:

Data are from the Growing Up Today Study, a longitudinal cohort of young adults (n=3,767) who are children of participants of the Nurses’ Health Study II, a separate longitudinal cohort. After characterizing psychological resilience according to levels of adversity exposure before age 18 and young adult psychological health (defined by a composite of low psychological distress and high positive affect), we derived a categorical measure by cross-classifying adversity (exposed vs unexposed) and psychological health (high vs lower). We considered five outcomes self-reported at baseline (2010) and five years later: healthy body weight and four healthy lifestyle components including being a non-smoker, moderate alcohol consumption, regular physical activity, and healthy diet. Poisson regression models evaluated associations of each outcome with psychological resilience, comparing psychologically resilient individuals to those who were not resilient or who were unexposed to adversity, adjusting for relevant covariates.

Results:

We did not identify differences between psychologically resilient individuals and those unexposed to adversity who were psychologically healthy with respect to meeting recommendations for most healthy lifestyle components and associations were largely stable over time. Across most outcomes, non-resilient individuals were less likely to be healthy relative to resilient individuals.

Conclusions:

Psychological resilience may disrupt negative effects of childhood adversity on having a healthy lifestyle in young adulthood.

Keywords: psychological resilience, healthy lifestyle, body weight, young adulthood

Childhood adversity is shown to increase risk for chronic diseases, potentially via unhealthy biobehavioral factors [1]. Indeed, individuals who experience childhood adversity may be more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors like smoking, alcohol consumption, or physical inactivity [2] and have less healthy body weight, which all increase chronic disease risk. Psychological distress (e.g., depression, anxiety), which often occurs following adversity, is also associated with unhealthy biobehavioral outcomes [2]. In contrast, psychological resilience, or positive psychological functioning despite childhood adversity [3], may disrupt effects of adversity and distress by increasing engagement in health-related behaviors that reflect a healthy lifestyle. The underlying capacity enabling individuals to circumvent negative psychological sequelae of childhood adversity may extend to other health-relevant domains, including maintenance of healthy body weight [4]. Important insight may be gained by examining associations of psychological resilience with behaviors and body weight during early adulthood, a time when many psychopathologies onset [5] and health trajectories are solidified [6].

Consistent, abundant evidence shows the negative psychological, physical, and social consequences of adverse childhood experiences [7]. Despite widespread childhood adversity experiences, many individuals show positive psychological functioning following exposure, demonstrating psychological resilience [8]. Resilience is often considered a dynamic process influenced by multiple, interacting internal and external factors which underly the capacity for resilience across the lifecourse [9]. Psychological resilience encompasses two domains: significant adversity and positive psychological functioning, including both low distress and positive well-being [3]. Definitions and measurements of resilience vary, focusing on individual trait resiliency, processes unfolding over time, or demonstrated capacity or outcome [10], with most prior research focusing on resilience as an outcome and examining factors that influence resilience [11,12].

Some cross-sectional work has examined associations between resilience and healthier lifestyle, identifying a positive relationship between self-report trait measures of resilience and healthy outcomes [13–15]. Studies demonstrated that higher trait resilience was associated with lower smoking [15], drinking and drug use [13], healthier diets [14] and more physical activity [14]. While intriguing, this work has some limitations. Trait measures assess one’s perceived ability to recover from adversity, reflecting one’s concept of their personal resiliency but failing to explicitly account for adversity experiences and assess psychological health. Furthermore, some work suggests trait resilience and manifested resilience are not necessarily strongly correlated [16]. Additionally, cross-sectional studies are unable to disentangle directionality of effects.

The current study examined whether psychological resilience to childhood adversity predicted greater likelihood of engaging in healthy behaviors and having healthy body weight across young adulthood in a community-based cohort. Health-related factors shown to influence later chronic disease risk [17] were included as outcomes: smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, diet quality, and body weight. Extending the mostly cross-sectional studies in this area, we included repeated outcome measures and defined manifested resilience using information on childhood adversity and young adult psychological health, thereby measuring demonstrated capacity rather than one’s perceived resiliency [18]. As prior work suggests that absence of psychopathology does not necessarily indicate positive functioning [19], our measure of psychological health incorporated levels of both distress and positive well-being [8]. We also categorized individuals into groups according to levels of psychological resilience to adversity.

Two complementary approaches to modeling resilience from developmental psychology include person-focused (i.e., classifying individuals by relevant characteristics) and variable-focused (i.e., examining links between specific factors and outcomes) [18]. Using a person-focused approach, we characterized individuals into one of four phenotypes: resilient (adversity-exposed, high psychological health); non-resilient (adversity-exposed, lower psychological health); unfavorable psychological functioning without adversity; and positive psychological functioning without adversity. We hypothesized that resilience would “disrupt” harmful effects of adversity occurring before age 18, whereby resilient individuals would not differ from those with positive psychological functioning without adversity in their likelihood of being healthy on each outcome. We also expected resilient individuals would be more likely to be healthy on each outcome compared to non-resilient or those with unfavorable psychological functioning without adversity. Using a variable-focused approach, we examined independent and interactive effects of adversity exposure and psychological health on each outcome. We hypothesized that adversity would decrease while psychological health would increase likelihood of being healthy on each outcome, and that higher psychological health would buffer higher adversity (i.e., effect modification).

Methods

Study Sample

Data are from the Growing Up Today Study I (GUTS1), a longitudinal cohort of young adults who are children of Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS2) participants, a separate longitudinal cohort. NHS2 began in 1989 involving biennial survey questionnaires, recruiting female registered nurses aged 25–42 in 15 US states resulting in 116,429 participants (24% response rate); additional details about the study recruitment and sample are described elsewhere [20]. In 1996, ~40,000 NHS2 participants with at least one child aged 9–14 were invited to enroll their children in GUTS1, resulting in 16,882 enrolled [21]. GUTS1 participants completed self-report questionnaires assessing health-related factors in 1996, annually until 2001, and approximately every two years thereafter.

As some of the resilience information was queried in 2010, this served as our study baseline (timeline in Appendix). Outcome information was assessed in 2010 and on one follow-up questionnaire in 2015. GUTS1 has had substantial attrition, with 51% (n=8,648) of the initial cohort participating by 2010. Among these participants, 6,631 (77%) had relevant exposure information and 4,158 (48%) also had complete outcome information. Due to low missingness on covariates (n=298, 7%), we conducted a complete case analysis excluding all individuals with any covariate missingness. We additionally excluded 93 individuals with serious youth health conditions (details in Appendix: Methods) for an analytic sample of 3,767 individuals. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Measures

Psychological resilience

Psychological resilience was defined by two domains: exposure to adversity before age 18 and young adult psychological health [22]. Childhood adversity was retrospectively reported in 2007 by participants, or prospectively by NHS2 participants (biennially from 1989 until GUTS1 participants were aged 18), and psychological functioning was reported in 2010 by participants. While adversity was assessed by respondents and their mothers at different times, prior work has demonstrated that reports of adversity tend to be valid and predictive of later health [23]. Moreover, ascertainment of childhood adversity occurred prior to measurement of psychological functioning in young adulthood, decreasing concerns that the latter could influence reporting of the former and permitting assessment of manifest psychological functioning in the context of adversity.

Childhood adversity included early-life psychosocial adversities that often co-occur, disrupt normative development, and negatively impact psychological health. Seven potential adversities included maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse [24,25], emotional abuse [24], sexual abuse [25], witnessing household abuse; reported by GUTS1 participants in 2007) and other psychosocial adversities (i.e., maternal depression, maternal divorce, maternal widowhood; reported by NHS2 participants biennially from 1989) occurring before age 18; that is, in childhood and/or adolescence. Individuals were classified as exposed or unexposed to each adversity (details in Appendix: Methods), similar to prior work in GUTS [26]. As no formal cut-offs for adversity exposure have been developed, binary adversity exposure was defined using a stringent cut-point of exposed (≥1 adversities) versus unexposed (no adversities), while continuous adversity was defined as a count of adversity types endorsed.

Following prior work seeking to assess the full continuum of psychological functioning [8,27], psychological health included measures of two forms of distress and of positive affect. Current psychological symptoms were reported in 2010 when GUTS1 participants were young adults, to determine psychological functioning after the relevant time period (i.e., childhood and adolescence) during which youth may have experienced adversity. Psychological distress included past week depressive (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale [28]) and anxiety symptoms (Worry/Oversensitivity Subscale, Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale [29]). Past month positive affect was assessed (Positive Affect Subscale, Mental Health Inventory [30]). There was modest item-level missingness (n=73 missing depression items, n=70 missing anxiety items, n=80 missing positive affect items). If participants completed a majority of items on each measure, total sum scores were imputed from the mean on completed items (see Appendix: Methods); otherwise, the measure was considered missing and participants were excluded. Distress scores were dichotomized as lower versus high according to clinical cut-points for depression (CES-D sum score≥10 [28]) and anxiety (Worry/Oversensitivity T-score>60 [29]). For positive affect, as standard cut-points are not established, the sample score was dichotomized to high (top tercile) versus lower (bottom two terciles) levels [31]. The dichotomy is conservative, designating only those with the highest positive affect as “high”. A composite continuous psychological health score was derived as the sum of z-scores of distress symptoms (inversed) and positive affect scores, higher scores indicate more positive functioning. Binary psychological health was defined as high (lower symptoms on both distress measures and high positive affect) versus lower (high symptoms on at least one distress measure or lower positive affect).

Categorical psychological resilience was cross-classified into four phenotypes using binary adversity exposure and binary psychological health [22]: resilient (adversity-exposed, high psychological health), non-resilient (adversity-exposed, lower psychological health), unfavorable psychological functioning without adversity (adversity-unexposed, lower psychological health), and positive psychological functioning without adversity (adversity-unexposed, high psychological health).

Healthy lifestyle components and body weight

Healthy lifestyle components included being a non-smoker (cigarettes), moderate alcohol consumption, regular physical activity, and healthy diet. Participants reported their behavior or other outcome information at baseline (or closest in time to baseline) in 2010 and again in 2015, except for diet which was measured at baseline only (among n=2,335). Outcomes were dichotomized as healthy versus unhealthy based on recommended adult levels, separately for baseline and follow-up (besides diet) [32,33]. See Appendix: Methods for variable derivations. Consistent with work using the Alternative Healthy Eating Index [34], healthy diet was the only healthy classification based on the sample distribution rather than external guidelines. Healthy body weight was determined using body mass index (BMI) derived from reports of height and weight (18.5 kg/m2<BMI<25 kg/m2); we also considered BMI as a continuous variable.

Covariates

Baseline (reported in 1996) sociodemographic covariates included sex, age, race/ethnicity, and childhood socioeconomic status (SES; father’s educational attainment reported by NHS2 participants in 1999; see Table 1 for covariate levels).

Table 1.

Distribution of baseline covariates in the total sample and by psychological resilience in GUTS1 (N=3,767)

| Psychological Resilience | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Total Sample N (%) | Resilient N=800, 21.2% N (%) | Non-resilient N=2,022, 53.7% N (%) | Unfavorable Psychological Functioning without Adversity N=570, 15.1% N (%) | Positive Psychological Functioning without Adversity N=375, 10.0% N (%) |

| Age (Mean (SD)) | 25.3 (1.6) | 25.3 (1.6) | 25.3 (1.6) | 25.4 (1.7) | 25.3 (1.7) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 2,638 (70.0) | 556 (69.5) | 1,456 (72.0) | 370 (64.9) | 256 (68.3) |

| Male | 1,129 (30.0) | 244 (30.1) | 566 (28.0)) | 200 (35.1) | 119 (31.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 3,536 (93.9) | 746 (93.3) | 1,889 (93.4) | 543 (95.3) | 358 (95.5) |

| Non-White | 231 (6.1) | 54 (6.8) | 133 (6.6) | 27 (4.7) | 17 (4.5) |

| Father’s Education | |||||

| Some HS or HS Graduate | 512 (13.6) | 102 (12.8) | 298 (14.7) | 65 (11.4) | 47 (12.5) |

| 2-year College | 574 (15.2) | 115 (14.4) | 332 (16.4) | 78 (13.7) | 49 (13.1) |

| 4-year College or more | 2,681 (71.2) | 583 (72.9) | 1,392 (68.8) | 427 (74.9) | 279 (74.4) |

HS=high school.

Analyses

We assessed distributions of resilience, outcomes, and covariates. To determine overall differences in prevalence of being healthy on each outcome, we compared the prevalence for each outcome averaged over the two time points across resilience phenotypes using ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc comparisons. We also assessed whether individuals changed “healthy” status across time for each outcome.

The analytic sample (n=3,767) tended to be healthier than those excluded due to missing data (n=2,864), indicating potential selection bias. To mitigate this, analytic models included inverse probability weights to account for likelihood of being in the analytic sample [35], creating a pseudo-population reflecting the larger population (see Appendix: Methods).

Prevalence of being healthy for each outcome at baseline was high, ranging from 39% for healthy diet to 83% for physical activity. We conducted a series of repeated measures Poisson regressions with generalized estimating equations (GEE) to estimate the relative risk of being healthy versus unhealthy from baseline to follow-up [36,37]. Repeated measure GEE models determine marginal effects accounting for correlated, longitudinal data with robust variance [37] and for sibling clustering (n=667 had a sibling). Models included a time term (years since baseline), assessed effects of psychological resilience cross-sectionally on likelihood of being healthy at baseline, and evaluated rate of change in likelihood of being healthy over time (via resilience group-time interactions). Effect estimates are presented as risk ratios (RR), indicating the likelihood of meeting recommended healthy levels on each outcome associated with each independent variable (relative to the reference, e.g., resilient group). Because diet was measured only at baseline, diet was analyzed cross-sectionally. For models predicting healthy body weight, we excluded any women who were pregnant at baseline or follow-up (n=326) as pregnancy weight gain influenced BMI estimation.

Our primary analyses compared resilient to each other group; however, post-hoc Tukey analyses assessed all two-way comparisons of phenotypes. For each outcome, we ran two models, first adjusting for age (mean-centered), then including all covariates that are potential confounders. We examined potential effect modification by sex. We also ran repeated linear regressions with GEE examining resilience with continuous BMI.

Supplemental analyses were conducted with standardized continuous adversity exposure and psychological health, and their multiplicative interaction to determine whether the effect of adversity on each outcome differed by psychological health. Each predictor was assessed cross-sectionally (main effects) and longitudinally (adversity-, psychological health-, adversity-psychological health-time interactions).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, we used an alternative cutoff for resilience phenotypes to test the robustness of our a priori binary adversity exposure definition. We revised our definition of exposure as ≥2 adversities (n=1,719, 46%) and unexposed as ≤1 adversity. Second, we tested the robustness of our a priori cutoff for positive affect, using a higher threshold dichotomization by defining high (≥ median) versus lower (< median) levels. Third, for analyses with BMI (both healthy versus unhealthy body weight and continuous BMI) we conducted primary models excluding underweight individuals (n=153), which may represent a qualitatively different unhealthy process from overweight/obese; categorical outcome models effectively estimated the likelihood of being overweight/obese versus normal weight. Fourth, to account for the concurrent assessment of psychological resilience with baseline outcomes, we reran primary models adjusting for adolescent levels of healthy lifestyle and body weight (see Appendix). Analyses were conducted in SAS v9.4.

Results

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. The sample was predominantly female (70%) and white (94%), with a mean baseline age of 25.3 (range 22–29) and high childhood SES (71% of fathers completed 4-year college or graduate school).

Most individuals (75%) experienced some childhood adversity, with 29% exposed to one, 23% to two, and 23% to three or more adversities. Common adversities were emotional abuse (50%), maternal depression (38%) and witnessing household violence (38%). Only 31% of the sample had high psychological health, regardless of adversity exposure. Regarding resilience phenotypes, 21% of the sample was adversity-exposed and resilient, 54% adversity-exposed and non-resilient, 15% adversity-unexposed with unfavorable psychological functioning, and 10% adversity-unexposed with positive psychological functioning.

Most of the sample was healthy with respect to each behavior and BMI (Table A1). Baseline outcomes were modestly inter-correlated, with correlations highest between smoking and alcohol consumption (r=0.26). Most individuals (76–86% across outcomes) maintained the same status (healthy or unhealthy) on each outcome over time.

Psychological resilience with healthy lifestyle components and body weight

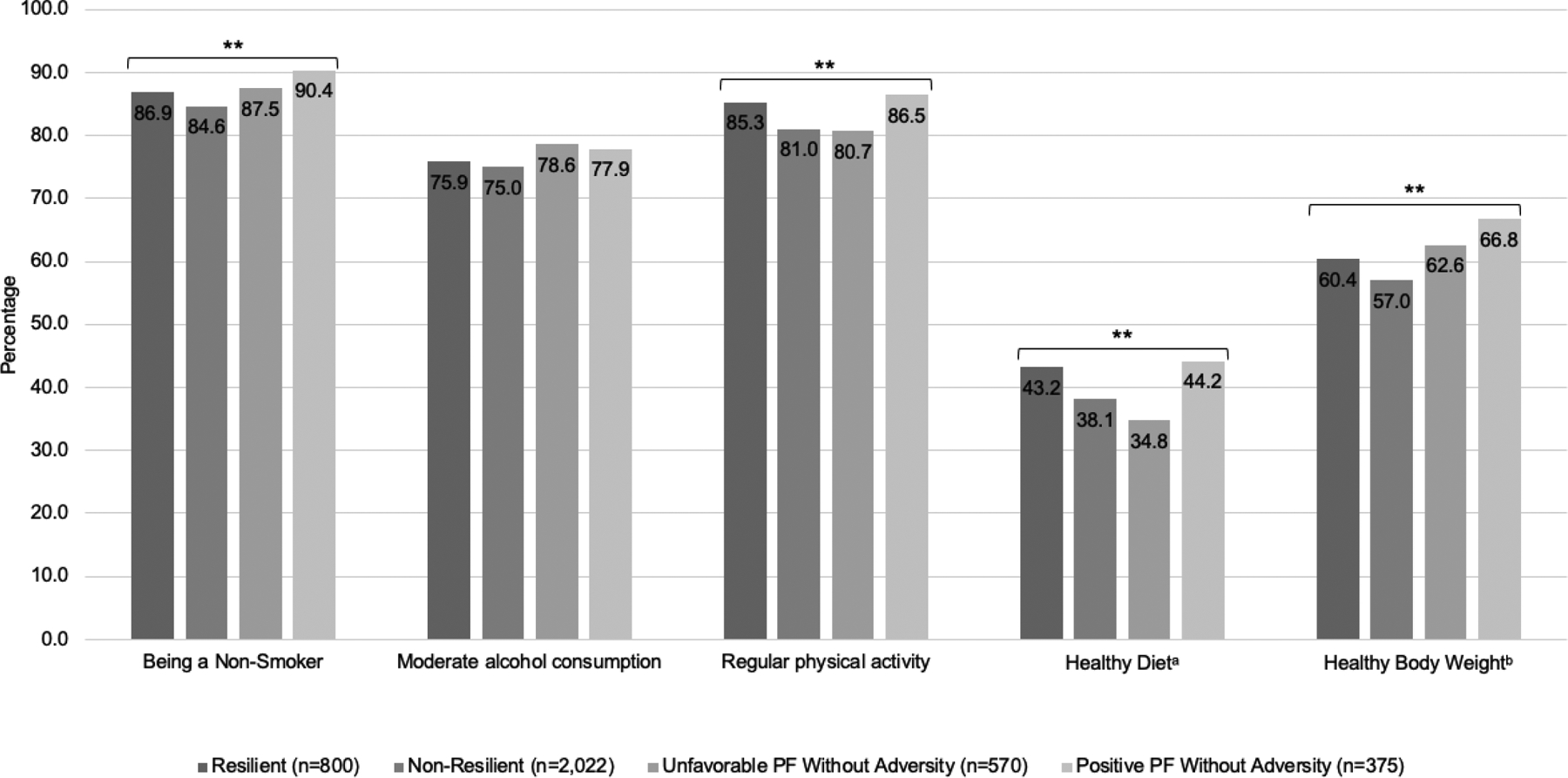

In bivariate models, the prevalence of each outcome averaged across time by resilience phenotypes (Figure 1) differed for smoking, physical activity, diet, and body weight, with differences most evident between non-resilient individuals and those adversity-unexposed with positive psychological functioning (Table A1: phenotypes comparisons).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of healthy lifestyle components and body weight averaged across baseline and follow-up by psychological resilience phenotype (n=3,767)

Displaying p-values for F-statistic tests of homogeneity in healthy lifestyle component and body weight status prevalence averaged from baseline to follow-up across resilience phenotypes.

PF=psychological functioning

a Data is cross-sectional (outcome is reported at baseline only), and n for analysis is 2,335

b n for analysis is 3,441 (excluding those who were pregnant)

**p<.05

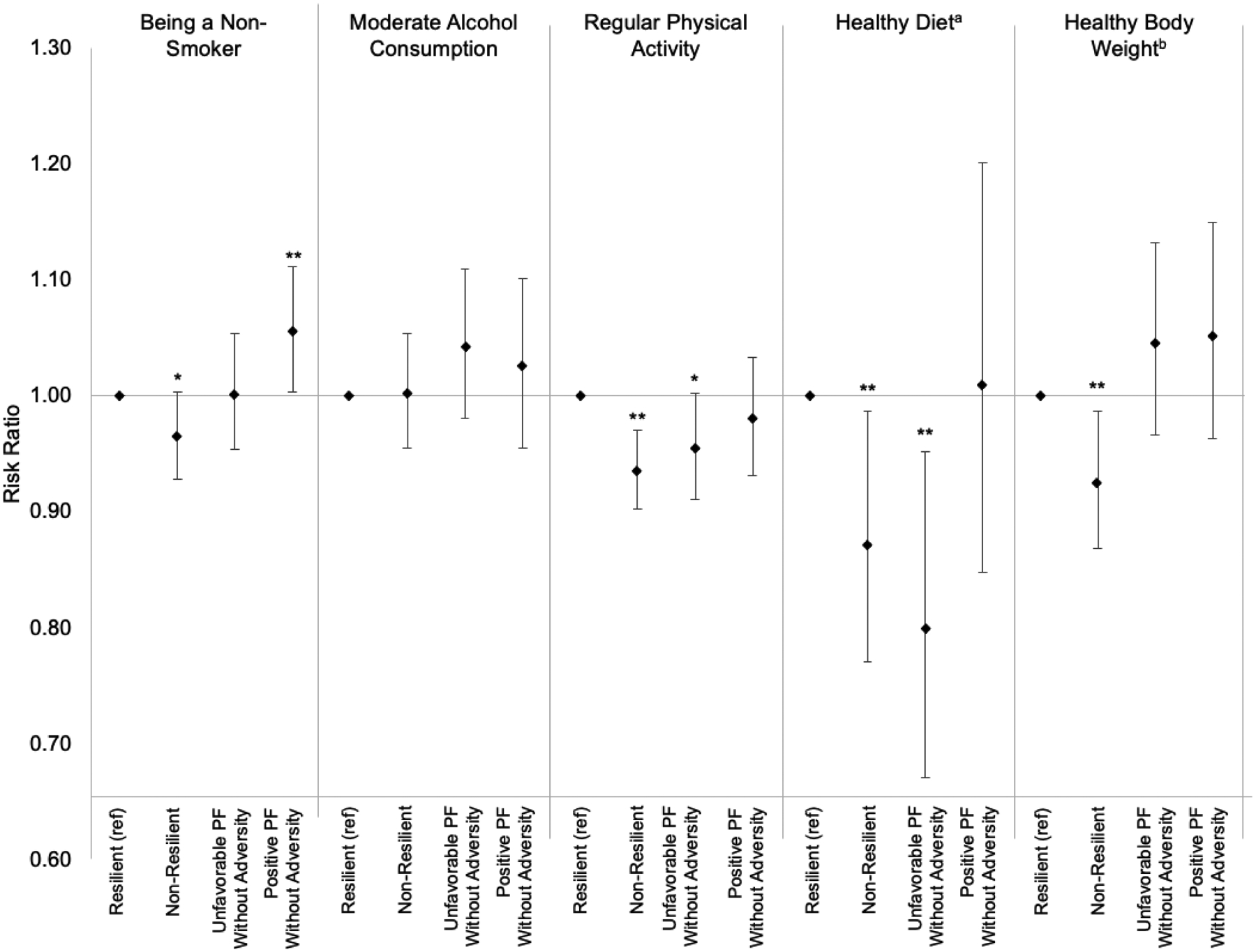

Accounting for time and covariates (Figure 2, Table 2), likelihood of being healthy on all outcomes at baseline except smoking did not differ between individuals with positive psychological functioning who did and did not experience adversity. Compared to resilient individuals, non-resilient were less healthy with respect to physical activity, diet, and body weight (marginal for smoking p=0.07). Individuals with unfavorable psychological functioning without adversity had lower likelihood of healthy diet and regular physical activity (marginal p=0.06) than resilient individuals. We did not find any effect modification by sex.

Figure 2.

Estimated main effects of psychological resilience on individual healthy lifestyle components and body weight from 2010 to 2015 from repeated measures Poisson regression models with GEE (n=3,767)

Displaying RR (risk ratios) and 95% confidence intervals. Models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and father’s educational attainment, and included time and resilience-time interactions

PF=psychological functioning. GEE=generalized estimating equations.

a Data is cross-sectional (outcome is reported at baseline only), and n for analysis is 2,335

b n for analysis is 3,441 (excluding those who were pregnant)

**p<.05, *p<.10

Table 2.

Repeated measures Poisson regression models with GEE for psychological resilience with resilience-time interactions predicting individual healthy lifestyle components and body weight from 2010 to 2015 (n=3,767)

| Being a Non-Smoker | Moderate Alcohol Consumption | Regular Physical Activity | Healthy Dieta | Healthy Body Weightb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Adjusted | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) |

| Resilient | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Non-resilient | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) d | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.93 (0.90, 0.97) d | 0.88 (0.77, 0.99) | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) c d |

| Unfavorable PF without Adversity | 1.00 (0.94, 1.05) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.12) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) e | 0.80 (0.67, 0.95) | 1.04 (0.96, 1.13) |

| Positive PF without Adversity | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.85, 1.21) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.15) |

| Time | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | -- | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) |

| Non-resilient X Time | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | -- | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) |

| Unfavorable PF without Adversity X Time | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | -- | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) |

| Positive PF without Adversity X Time | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | -- | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) |

| Covariate Adjusted | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) |

| Resilient | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Non-resilient | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) d | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.97) d | 0.87 (0.77, 0.99) | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) c d |

| Unfavorable PF without Adversity | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.11) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.00) e | 0.80 (0.67, 0.96) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) |

| Positive PF without Adversity | 1.06 (1.00, 1.11) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.10) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.85, 1.20) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.15) |

| Time | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | -- | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) |

| Non-resilient X Time | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | -- | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) |

| Unfavorable PF without Adversity X Time | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | -- | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) |

| Positive PF without Adversity X Time | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | -- | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) |

Cell entries are risk ratios (RR) for each resilience category vs. resilient [referent] and 95% Confidence Intervals. Models adjust for inverse probability weights for loss to follow-up. Covariates are age, sex, race/ethnicity, and father’s educational attainment.

Effects p<.05 are bolded. Effects p<.10 are italicized.

GEE=generalized estimating equations. PF=psychological functioning.

Analysis is cross-sectional (outcome is reported at baseline only) and n for analysis is 2,335

n for analysis is 3,441 (excluding pregnant women)

Tukey post-hoc comparisons:

Non-resilient vs. unfavorable PF without adversity is significantly different (p<.05)

Non-resilient vs. positive PF without adversity is significantly different (p<.05)

Unfavorable PF without adversity vs. positive PF without adversity is significantly different (p<.05)

Considering change over time in likelihood of being healthy on each outcome, likelihood of being a non-smoker, moderate alcohol consumption, and regular physical activity increased over time for everyone, indicated by elevated (RRs>1.0) time effects (Table 2). Considering whether resilience phenotypes predicted differential change in likelihood of being healthy on each outcome over follow-up, patterns were similar between phenotypes for smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity (no significant resilience-time interactions). However, individuals with positive psychological functioning who did not versus did experience adversity had a higher likelihood of maintaining or attaining healthy body weight over time (RRpositive psychological functioning without adversityXtime=1.02, p=.02), such that resilient individuals were less likely to be healthy by follow-up.

To further explore body weight findings, we compared continuous BMI levels across resilience phenotypes (Table A2). Average baseline BMI was slightly higher among individuals with positive psychological functioning who did versus did not experience adversity. Time and resilience-time interaction estimates suggested BMI slightly increased similarly for everyone and resilience was unassociated with differential rate of BMI change. However, because resilient individuals had higher baseline BMI, with even a small weight gain they were more likely to develop unhealthy BMI during follow-up.

Findings using continuous adversity, psychological health, and their interaction produced results largely consistent with primary models (Table A3). Higher adversity was associated with lower likelihood of being healthy on all outcomes except diet; better psychological health was associated with higher likelihood of being healthy on all outcomes except alcohol consumption, though adversity-psychological health interactions were not significant.

Findings that characterized resilience using a higher threshold adversity classification (Table A4, Figure A2) and using a less conservative positive affect classification (Table A5, Figure A3) were consistent with primary models. Associations were mostly unchanged after excluding underweight individuals (data not shown). In sensitivity analyses adjusting for adolescent/young adult levels of each outcome, findings were largely similar to primary analyses although differences between resilience groups in smoking were attenuated (Tables A6 and A7; Appendix Results).

Discussion

We investigated whether psychological resilience to childhood adversity was associated with likelihood of meeting recommended guidelines on lifestyle components and body weight in young adulthood [32–34]. Results mostly confirmed our hypothesis that resilient and adversity unexposed, positive psychological functioning phenotypes would be similar. Individuals who manifested psychological resilience had healthy behaviors and body weight strikingly similar to peers with positive psychological functioning unexposed to childhood adversity. Such results suggest later psychological health may largely buffer harmful effects of adversity on healthy lifestyle and body weight, though some minimal residual negative impact may occur. Findings supported our hypothesis that individuals with unfavorable psychological functioning with or without adversity would be less likely than resilient individuals to meet recommended guidelines across outcomes, with most differences evident among non-resilient individuals. Of note, individuals with unfavorable psychological functioning with or without adversity exposure did not significantly differ on most outcomes, suggesting psychological distress is a critical factor for predicting less healthy lifestyle or body weight.

Our findings are largely consistent with similar cross-sectional work that did not incorporate adversity into resilience operationalization. For example, one study of 20,700 adolescents conceptualized resilience based on self-reported positive factors like happiness, confidence, and social support, and found a 1-unit increase in resilience was associated with 5% less smoking, 6% lower alcohol consumption, and 4% lower drug use [13]. Several of our findings are particularly noteworthy. Compared to a nationally representative young adult sample, alcohol consumption, physical activity and healthy body weight levels were comparable, but GUTS1 participants were less likely to smoke [38,39]. However, compared to trends in other work whereby individuals entering young adulthood become less healthy [40], our sample became modestly healthier with respect to smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity over follow-up. Changes in likelihood of meeting healthy guidelines over time did not differ by resilience group, and several explanations are possible. First, resilience may not influence change in lifestyle over time, but rather may impact lifestyle earlier in life, resulting in average differences but not subsequent changes. Second, our follow-up may be too limited; effects may manifest over longer time periods or at different ages.

Findings with body weight were consistent with national trends [41], as our sample overall became less healthy. While this change appeared more pronounced among resilient individuals relative to those unexposed to adversity with positive psychological functioning, this was likely because the resilient group had slightly higher BMI at baseline. Overall, having a healthy body weight and changes in weight over time were mostly similar between these phenotypes. Worth noting, few individuals had both adversity and high psychological health, potentially due to our stringent criteria. However, in sensitivity analyses requiring higher number of adversity experiences to meet criteria for exposure or lowering the threshold for high positive affect, overall findings were similar.

Individuals who are psychologically resilient after childhood adversity may have more effective self-regulation, including appropriately responding in cognitive, affective, and behavioral domains in a given context. Specifically, greater resilience may promote more attentional control, emotion regulation, and resisting impulses, ultimately promoting healthier behavior [19].

There are several limitations to note. While some adversities were reported by mothers, others were retrospectively reported by participants and subject to recall bias. However, even retrospectively reported experiences were reported three years before psychological health was assessed and both adversity and psychological health were assessed well before the second follow-up. Psychological health was indexed with two distress and one positive domain. It is preferable to have comparable measures of positive and negative functioning, although prior work has found even slightly unbalanced psychological measures can be informative [27]. We specifically examined young adult psychological health to capture functioning after childhood adversity would have occurred; however, youth psychological health more proximate to adversity is another important indicator of resilience and future studies should examine concurrent relationships between adversity and psychological symptoms with health outcomes. Outcomes were also self-reported, although self-reported health behaviors are generally accurate [42] and similar measures were previously validated in a related cohort [43]. Baseline outcomes were assessed concurrent with psychological functioning in 2010, thereby introducing the possibility of reverse causation in this association. However, follow-up outcomes five years later were assessed to improve temporal ordering of exposures and outcomes, and to determine potential change in behaviors or body weight over time associated with exposures. Additionally, sensitivity analyses adjusted for healthy lifestyle and body weight prior to exposure measurement resulted in similar findings, providing further evidence against reverse causation. Due to data availability, baseline physical activity was assessed prior to assessment of resilience variables and is therefore findings regarding these relationships could be more strongly subject to concerns about reverse causality. Sample attrition limited power and increased risk of selection bias; however, inverse probability weighting should attenuate selection bias concerns. While some of our estimated effects of resilience with outcomes were modest, prior work has demonstrated attention to factors with small effect sizes can translate into meaningful population level impact if associations affect many individuals in the population or if many small effects act in concert to create composite effects [44]. Given our findings are from a mostly white and higher SES sample, generalizability to more diverse populations may be limited. Marginalized communities experience greater adversity in conjunction with other social disadvantage; our more advantaged sample may have faced fewer adversities and also had more resources that promote psychological resilience. Further, because they are children of nurses, relative to the general population participants in this study may have higher awareness of health and healthy behaviors. As it is possible that associations between adversity, psychological health, and health outcomes would be even more pronounced in populations that have experienced greater adversity and have less healthy behavior patterns, future research should examine associations in more diverse samples.

Our findings that psychological resilience to adversity in young adulthood may increase the likelihood of subsequently having healthier lifestyle and body weight extend the literature in several ways. We considered a comprehensive resilience measure and repeated assessments of biobehavioral factors relevant for health promotion [6]. Rather than assessing one’s perceived resilience, our measure captured demonstrated capacity by incorporating adversity and psychological health using markers of negative and positive functioning. Despite a relatively short follow-up, we found modest associations linking resilience with multiple health-related outcomes. Our findings suggested that harmful effects of childhood adversity on health are not inevitable and may be offset among individuals who show resilience. Interventions that promote resilience among adversity-exposed youth or promote healthy behavior among less resilient young adults who experienced adversity have the potential to improve healthy lifestyle patterns in young adults. For example, structural school- or family-based youth interventions involving promotion of parent-child connections, parental well-being, or school-based mindfulness show promise in promoting resilience [45]. Policies or interventions which promote resilience to childhood adversity may benefit not only mental health, but also long-term physical health. Future studies should determine if the promotive benefit of resilience we found translates to reducing chronic disease risk and if so, psychological resilience in young adulthood may represent a key psychosocial capacity for promoting long-term health.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contribution.

Achieving psychological resilience, or manifesting positive psychological health following childhood adversity, may promote healthy lifestyle behaviors and body weight in young adulthood. Promoting resilience following childhood adversity may result in healthier behavior and weight status, setting positive physical health trajectories across the lifecourse.

Acknowledgements:

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank the Channing Division of Network Medicine Biorepository and Growing Up Today Study (GUTS) team of investigators for their contributions to this paper and the thousands of young people across the country participating in the GUTS cohort. This study was funded by NIH grants HD057368 and HD066963. Kristen Nishimi was supported by T32 MH 017119-33, the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness Dissertation Research Award and the VA Data Science Fellowship at the San Francisco VA Healthcare System. Brent Coull was supported by NIH ES000002. Kristen Nishimi made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and to data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the article. Karestan Koenen, Brent Coull, and Laura Kubzansky made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study, revised the article for important intellectual content, and read and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript. The article contents have been presented as a student poster by Kristen Nishimi at the at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Annual Meeting in Boston, MA, November 2019. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Abbreviations:

- GUTS1

Growing Up Today Study I

- NHS2

Nurses’ Health Study II

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression

- BMI

body mass index

- SES

socioeconomic status

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- RR

relative risk

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts of interest were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- [1].Suglia SF, Koenen KC, Boynton-Jarrett R, Chan PS, et al. Childhood and Adolescent Adversity and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137(5):e15–e28. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, et al. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart’s content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychol Bull 2012;138(4):655–691. doi: 10.1037/a0027448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007;20(4):359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lawrence EM, Mollborn S, Hummer RA. Health lifestyles across the transition to adulthood: Implications for health. Soc Sci Med 2017;193:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Petruccelli K, Davis J, Berman T. Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child abuse & neglect 2019;97:104127. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bonanno GA, Diminich ED. Annual Research Review: Positive adjustment to adversity--trajectories of minimal-impact resilience and emergent resilience. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines 2013;54(4):378–401. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cicchetti D Resilience under conditions of extreme stress: a multilevel perspective. World Psychiatry 2010;9(3):145–154. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Choi KW, Stein MB, Dunn EC, Koenen KC, et al. Genomics and psychological resilience: a research agenda. Mol Psychiatry 2019;24(12):1770–1778. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0457-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wright MOD, Masten AS, Narayan AJ. Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In: Handbook of resilience in children. Springer; 2013:15–37. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Infurna FJ, Luthar SS. Re-evaluating the notion that resilience is commonplace: A review and distillation of directions for future research, practice, and policy. Clin Psychol Rev 2018;65:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ali MM, Dwyer DS, Vanner EA, Lopez A. Adolescent propensity to engage in health risky behaviors: the role of individual resilience. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010;7(5):2161–2176. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7052161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gage GS. Social Support and Positive Health Practices in Black Late Adolescents. Clin Nurs Res 2017;26(1):93–113. doi: 10.1177/1054773815594579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Goldstein AL, Faulkner B, Wekerle C. The relationship among internal resilience, smoking, alcohol use, and depression symptoms in emerging adults transitioning out of child welfare. Child Abuse Negl 2013;37(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nishimi K, Choi KW, Cerutti J, Powers A, et al. Measures of adult psychological resilience following early-life adversity: how congruent are different measures? Psychological medicine 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chomistek AK, Chiuve SE, Eliassen AH, Mukamal KJ, et al. Healthy lifestyle in the primordial prevention of cardiovascular disease among young women. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2015;65(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Masten AS. Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol 2001;56(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kubzansky L, Boehm JK, Segerstrom SC. Positive Psychological Functioning and the Biology of Health . Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2015;9(12):645–660. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Origin, Methods, and Evolution of the Three Nurses’ Health Studies . Am J Public Health 2016;106(9):1573–1581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Solomon CG, Willett WC, Carey VJ, Rich-Edwards J, et al. A prospective study of pregravid determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA 1997;278(13):1078–1083. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550130052036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Masten AS, Burt KB, Roisman GI, Obradovic J, et al. Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: continuity and change. Dev Psychopathol 2004;16(4):1071–1094. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Reuben A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Belsky DW, et al. Lest we forget: comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines 2016;57(10):1103–1112. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. The American journal of psychiatry 1994;151(8):1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, et al. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse Negl 1998;22(4):249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, et al. Childhood gender nonconformity: a risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics 2012;129(3):410–417. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Kasper JD, et al. Emotional vitality among disabled older women: The Women’s Health and Aging Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1998;46(7):807–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc 1991;20(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mattison RE, Bagnato SJ, Brubaker BH. Diagnostic utility of the revised children’s manifest anxiety scale in children with DSM-III anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 1988;2(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(88)90021-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Veit CT, Ware JE Jr. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51(5):730–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Keyes CL. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav 2002;43(2):207–222. doi: 10.2307/3090197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].US Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. In: US Department of Agriculture, ed. 5th ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [33].US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. In: Office of Disease Prevention & Health Promotion, ed. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ford ES, Bergmann MM, Boeing H, Li C, et al. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and all-cause mortality among adults in the United States. Prev Med 2012;55(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res 2013;22(3):278–295. doi: 10.1177/0962280210395740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wang M Generalized estimating equations in longitudinal data analysis: a review and recent developments. Advances in Statistics 2014;2014:303728. doi: 10.1155/2014/303728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Olson JS, Hummer RA, Harris KM. Gender and Health Behavior Clustering among U.S. Young Adults. Biodemography Soc Biol 2017;63(1):3–20. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2016.1262238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Saydah S, Bullard KM, Imperatore G, Geiss L, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors among US adolescents and young adults and risk of early mortality. Pediatrics 2013;131(3):e679–e686. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mulye TP, Park MJ, Nelson CD, Adams SH, et al. Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 2009;45(1):8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lee H, Lee D, Guo G, Harris KM. Trends in body mass index in adolescence and young adulthood in the United States: 1959–2002. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 2011;49(6):601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, et al. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hawkins M, Tobias DK, Alessa HB, Chomistek AK, et al. Objective and Self-Reported Measures of Physical Activity and Sex Hormones: Women’s Lifestyle Validation Study. J Phys Act Health 2019;16(5):355–361. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2018-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Roberts BW, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, et al. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological science 2007;2(4):313–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Twum-Antwi A, Jefferies P, Ungar M. Promoting child and youth resilience by strengthening home and school environments: A literature review. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 2020;8(2):78–89. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2019.1660284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.