Abstract

Recent genetic approaches have demonstrated that genetic factors contribute to the pathologic origins of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nevertheless, the exact pathophysiological mechanism for most cases remains unclear. Recent studies have demonstrated alterations in pathways of protein homeostasis, proteostasis, and identified several proteins which are misfolded and/or aggregated in the brains of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders, thus providing early evidence that disrupted proteostasis may be a contributing factor to their pathophysiology. Unlike neurodegenerative disorders in which massive neuronal and synaptic losses are observed, proteostasis impairments in neuropsychiatric disorders do not lead to robust neuronal death but likely act via loss and gain of function effects to disrupt neuronal and synaptic functions. Furthermore, abnormal activation of or overwhelmed ER and mitochondrial quality control pathways may exacerbate the pathophysiological changes initiated by impaired proteostasis, as these organelles are critical for proper neuronal functions and involved in the maintenance of proteostasis. This perspective article reviews recent findings implicating proteostasis impairments in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders, and explores how neuronal and synaptic functions may be impacted by disruptions in protein homeostasis. A greater understanding of the contributions by proteostasis impairment in neuropsychiatric disorders will help guide future studies to identify additional candidate proteins and new targets for therapeutic development.

Introduction

Neuropsychiatric disorders including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), schizophrenia (SZ), bipolar disorder (BD), and major depressive disorder (MDD) affect a substantial population worldwide and altogether represent a significant healthcare issue with great socioeconomic impact. Whilst approximately 1-2% of the general population is estimated to be affected by ASD (1.85%) (1), SZ (<1%) (2–6), and BD (2.6%) (7), recent data from the United States revealed that about 7% of the adult population and approximately 14% of adolescents experienced at least one major depressive episode in a year (8). Through traditional linkage analyses of families with a medical history of neuropsychiatric disorders, genetic factors have been known for decades to play a significant role in the pathophysiological process. With the advent of whole genome and exome sequencing studies, our understanding of the genetic factors causing these disorders have charted significant progress. Notably, de novo (absent from both parents and siblings) point mutations and copy number variations (CNVs) are frequently identified from patients with neuropsychiatric disorders, thus helping to explain many sporadic cases in which there are no family history of the disorders (9). Furthermore, whereas rare de novo CNVs and point mutations disrupting protein structure/function often have larger effect sizes and therefore may contribute directly to pathophysiology, such massive sequencing studies have also identified many common variants that on their own may not exert a heavy pathogenic burden but collectively confer enhanced risk. Therefore, such observations suggest that these disorders are polygenic and highly complex in nature, and that genetic factors alone may not fully account for all cases. As a result, recent studies have begun to explore the impairment of protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, as a putative mechanism which may contribute to the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Disruption of protein homeostasis in neuropsychiatric disorders

In broad terms, proteostasis is maintained at multiple levels during the lifetime of a protein. Given that most cellular functions are mediated by proteins, dysregulation of proteostasis is known to have detrimental consequences. The correct folding and assembly of proteins into monomers and multimeric complexes are central to their normal functions. During and following protein synthesis, various intra- and inter-molecular interactions dictate how the polypeptide chain will be organized into its unique three-dimensional structure (10). However, due to many interconvertible conformational states, proteins can be entrapped into non-native conformations by energetic barriers. In addition to influence by such intrinsic properties, environmental factors including temperature, pH, and salt concentration can also alter protein conformations and influence their misfolding and aggregation potentials. Therefore, a number of cellular quality control mechanisms including co- and post-translational processes assist polypeptide chains to adopt their native structures (Figure 1). For instance, the unfolded protein response (UPR) and integrated stress response (ISR) pathways are primarily activated via stress signals triggered by aberrant protein folding inside the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and in turn act to slow down de novo protein synthesis and enhance protein folding capacity (Figure 2). Aside from such homeostatic measures, degradative pathways such as autophagy and ubiquitin proteasomal system (UPS) can be used for the removal of unnecessary or damaged proteins (11). Specially, if protein misfolding and/or unfolding occurs inside the ER, ER-associated degradation (ERAD) is used for the retro-translocation of the polypeptide chain out of the ER and sent to the UPS for degradation (12). In addition, proper proteostasis also includes the regulation of post-translational modifications, such as proteolytic cleavage, phosphorylation, and acetylation, that can affect protein-protein interactions and enzymatic activities involved in various cellular signaling pathways. Notably, these post-translation modifications also have been demonstrated to have profound influence on the conformational dynamics and stability of proteins, thereby further disturbing proteostasis (13–15). Impaired proteostasis may occur when the aforementioned homeostatic mechanisms are impaired by genetic and non-genetic factors, potentially allowing aberrant protein conformational states to progress into soluble oligomers and insoluble aggregates. Altogether, it is clear that maintenance of protein homeostasis is critically important to proper cellular functions.

Figure 1. Homeostatic pathways against protein misfolding and aggregation.

Various mechanisms have been developed by the cell to protect against protein misfolding and aggregation. During and following mRNA translation, chaperones assist the nascent polypeptide chain via co-translational and post-translational mechanisms to fold properly into the correct “native” three-dimensional conformations. Once correctly folded, proteins can carry out their functions as monomeric proteins or multimeric protein complexes. However, they may become unfolded due to cellular stresses and require chaperones to return to their native conformations or shuttle for removal by proteasomal or autophagic degradation. If such misfolded proteins are not recognized by chaperones for refolding or degradation in a timely manner or the aforementioned cytoprotective mechanisms have been overwhelmed, these misfolded proteins may assume non-native conformations. Such non-native conformations remain as non-functional monomers or form soluble oligomers which could have functional properties different from their native monomeric counterparts. Furthermore, additional interacting proteins may be sequestered into these conformationally-altered species via heterotypic interactions and result in network-wide proteostatic disruptions.

Figure 2. ER stress and aberrant overactivation of ER quality control pathways.

Cell surface and secreted proteins are typically translated by ribosomes and imported into the ER in a co-translational manner. Misfolded proteins, due to pathologic mutations or reduced protein folding capacity in the ER, may disrupt ER-Golgi trafficking, which results in the ER accumulation of affected proteins, and increase ER-associated degradation (ERAD). Both of these could have negative effects as the expression and subcellular localization required for proper cell functions may be greatly impacted. Furthermore, the resulting ER stress consequently initiates the unfolded protein response (UPR), which triggers PERK, ATF6, and/or IRE1α-dependent pathways to enhance the ER protein folding capacity. Meanwhile, the overload in this protein folding capacity is reduced by suppressing global protein synthesis through the phosphorylation of eIF2α. Chronic eIF2α phosphorylation due to persistent ER stress may have detrimental effects as de novo protein synthesis is required for various types of synaptic plasticity and thereby disrupt the proper functioning of affected neurons.

Much of our current knowledge concerning proteostasis impairments in the brain derives from extensive work focussed on neurodegenerative disorders. Decades-old observations from post-mortem human brain samples of patients suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), Huntington’s Disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) have revealed protein misfolding and aggregation to be the principal culprits (16). Each of these diseases is characterized by the visible formation of insoluble proteinaceous deposits of a disease-associated protein such as amyloid beta (Aβ), α-synuclein, huntingtin, and TDP-43, respectively, in affected neurons. The formation of such insoluble aggregates is the result of an imbalance between protein misfolding/aggregation and cellular cytoprotective mechanisms, which is frequently caused by either disease-associated mutations (e.g., α-synuclein A53T) (17) or alterations in their processing pathways (e.g., γ-secretase cleavage of APP by presenilin 1/2) (18–21). The aggregated protein in turn accumulates in a time-dependent manner and disrupts normal cellular functions. With time, the affected neurons ultimately succumb to apoptotic or other forms of cell death and manifest as the corresponding neurodegenerative disorder following substantial neuronal loss (22).

Interestingly, a growing list of studies using post-mortem brain samples or blood collected from patients with neuropsychiatric disorders have identified changes indicative of alterations in proteostasis. Specifically, protein expression changes in regulators of autophagy (23–25), UPS (26–34), and ER quality control (ERQC) pathways (35–42) have been associated with patients diagnosed with ASD, schizophrenia, bipolar, and major depressive disorders (Table 1). In fact, protein levels of critical regulators of autophagy such as Atg7, Beclin 1, LC3, and p62/SQSTM1 have been shown to be reduced in BD and SZ patients; whereas increases in mRNA transcripts of ATG12, BECN1, and MAP1LC3A/B/C were observed in MDD (23–25). Notably, previous studies have revealed that many components of the UPS, ranging from ubiquitin itself, E2 and E3 enzymes, to subunits of the proteasome, are downregulated in SZ patients (27–29,31–34). Furthermore, it should be noted that reduced proteasomal degradative activities were observed in post-mortem brain samples from SZ patients (26), and several recent studies have observed either increased levels of ubiquitinated (43,44) or insoluble proteins (44) from a subset of SZ brain samples; further implicating proteasomal dysfunction in the disorder. Importantly, the study that identified increases of both ubiquitinated and insoluble proteins in SZ brains was able to replicate the finding in three distinct sample sets from independent brain banks (44). Furthermore, mass spectrometric analyses revealed that insoluble proteins were enriched in neurons and may exhibit cell type specificity. In addition, multiple studies have revealed alteration of UPR and ERAD pathways for ASD, BD, MDD, and SZ. Gene expression analyses have found upregulation of various components of the UPR and ERAD pathways in patient-derived tissue samples (35–40,42). In contrast, two studies demonstrated reduced UPR activation in response to tunicamycin-induced ER stress using lymphocytes collected from BD patients (41,45). The discrepancy between these studies may reflect a difference between the response to acute and chronic ER stress, but suggest that ER quality control is dysregulated in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders. Altogether, these findings from clinical samples indicate that disrupted proteostasis is observed in neuropsychiatric disorders, but precisely how proteostasis impairments contribute to their pathophysiology remains elusive.

Table 1.

Alterations in proteostasis pathways observed in brain or blood samples from patients with neuropsychiatric disorders

| Disorder | Pathway affected | Genes/proteins affected | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autism spectrum disorder | ERQC | ATF4, ATF6, CHOP, IRE1, PERK, total and spliced XBP1 mRNA ↑ | (40) |

| Bipolar disorder | Autophagy | MAP1LC3A, SQSTM1 mRNA ↓ mRNA ↓ LC3, p62/SQSTM1 proteins ↓ | (25) |

| ERQC | phospho-EIF2α, CHOP, GRP78 proteins ↓ (lymphocytes subjected to tunicamycin-induced ER stress) | (45) | |

| CHOP, XBP1 mRNA ↓ (lymphocytes subjected thapsigarcin- or tunicamycin-minduced ER stress) | (41) | ||

| BIP mRNA ↑ Total and unspliced XBP1 mRNA ↓ | (39) | ||

| Major depressive disorder | Autophagy | ATG12, BECN1, LC3 mRNA (isoform not specified) ↑ | (24) |

| ERQC | BIP, CHOP, EDEM1, XBP1 mRNA ↑ | (35) | |

| Calreticulin, GRP78, GRP94 protein ↑ (suicide subjects only) | (38) | ||

| ATF4C, GRP78, GRP94 mRNA ↑ (suicide subjects only) | (42) | ||

| Schizophrenia | Autophagy | BECN1 mRNA ↓ BCL2 mRNA ↑ | (23) |

| ADNP mRNA ↑ ADNP2 mRNA ↑ | |||

| ATG7 protein ↓ | (33) | ||

| ERQC | BIP protein ↑ PERK protein ↓ phopho-IRE1α ↓ XBP1 mRNA splicing ↑ | (37) | |

| EDEM2, HRD1, UGGT2 protein ↑ | (36) | ||

| ATF4, PERK protein ↓ | (88) | ||

| UPS | Trypsin-like activity (nucleus) ↓ Chymotrypsin-like activity (cytosol) ↓ | (26) | |

| 19S regulatory particle subunits Rpt1, Rpt3, Rpt6 protein ↓ 11S regulatory particle α subunit protein ↓ | (27) | ||

| HERPUD1, PSMA1, PSMB6, PSMC6, PSMD8, PSMD9, PSME1, UBB, UBE2D1, UBE2D3, UCHL1 mRNA ↓ UBL4A mRNA ↑ | (28) | ||

| PSMA1, UCHL1, USP9X mRNA ↓ | (34) | ||

| UBE2N mRNA ↓ | (29) | ||

| UBE2K mRNA and protein ↑ | (30) | ||

| UBE3B mRNA and protein ↓ | (31) | ||

| UCHL1, USP14 mRNA ↓ | (32) | ||

| NEDD4, PIAS3 RNF7, UBA3, UBA6, UFL1, protein ↓ | (33) |

Notably, unlike in neurodegenerative disorders, there have yet to be reports of visible aggregates in post-mortem brain samples of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders. Instead, proteins are described to be conformationally-altered on a biochemical basis in that they are reported to be increased in detergent-insoluble fractions of patient-derived samples (46–49) or display aggresome-like punctate subcellular localizations upon overexpression in immortalized cell lines or primary neurons (47,50–53). It remains to be seen whether this trend will continue to hold true while additional conformationally-altered proteins are identified and linked to these disorders in future studies. Importantly, unlike neurodegenerative disorders, neuropsychiatric disorders are not typically degenerative in nature, as robust neuronal cell death is not typically detected. Furthermore, in vivo prion-like spread of visible protein aggregates is not generally observed in neuropsychiatric disorders. These observations likely reflects a difference in the biochemical and biophysical properties of the pathogenic proteins involved. Such differences may be the critical features that distinguish between aggregation-prone proteins in these disorders and the proteins responsible for neurodegenerative disorders. The substantial loss of specific neurons in neurodegenerative disorders suggests that treatment may require therapeutic strategies such as stem cell replacement (54) or trans-differentiation (55) for full recovery. In contrast, the absence of extensive neuronal cell death in neuropsychiatric disorders provides a glimpse of hope that these conditions are potentially reversable if impaired proteostasis can be restored.

Loss and gain of function effects by protein misfolding and aggregation in preclinical studies

Whilst the abovementioned studies have observed changes in protein degradation or stress pathways in patient-derived samples, there have also been direct identification of proteins that are increased in the detergent-insoluble fractions generated from subsets of post-mortem human brain samples of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders compared to healthy controls. This list of conformational-altered proteins includes DISC1 (47,49,53), dysbindin-1 (47), collapsin response mediator protein 1 (CRMP1) (48), Trio-binding protein 1 (TRIOBP-1) (50), and GABAA receptor-associated proteins (GABARAPs) (46). In addition, other studies have also demonstrated disease-associated mutations in DISC1 (53), neuronal PAS domain protein 3 (NPAS3) (52), and DEAD-box helicase 3 X-linked (DDX3X) (51) to enhance their aggregation potentials. The elucidation of how conformational alterations of these proteins impair neuronal and synaptic functions will provide important mechanistic insight into how disrupted proteostasis may ultimately cause neuropsychiatric disorders.

Through previous studies based on proteins associated with neurodegenerative disorders and the abovementioned studies on proteins which are misfolded or aggregated in neuropsychiatric disorders, the common molecular mechanism underlying their pathophysiology may be the loss and gain of functions of the protein of interest. The increase in insoluble protein due to misfolding effectively reduces the functional protein pool, as they can no longer assume the correct three-dimensional structures to properly perform their functions. In addition, reduced solubility may also affect their subcellular localization such that they are no longer in the proper locations to carry out their normal functions. For example, the misfolding of DISC1 was found to disrupt the interaction with nuclear distribution protein nudE-like 1 (NUDEL/NDEL1), which depends on an oligomeric state of DISC1 (49,56). Functionally, this interaction has been shown to be critical to DISC1’s function in regulating microtubular dynamics (57) and resulted in schizophrenia-like behavioural deficits when it was disrupted in mouse models (58–60). In addition, the overexpression of full-length wild-type DISC1 in a transgenic rat model was also shown to result in aggregation and mislocalization of DISC1. Such changes may have limited the functional pool available to mediate its functions in regulating dopamine homeostasis (61), the disruption of which contributed to anxiogenic-like behaviour (62) and deficits in learning and memory (63,64).

Alternatively, proteostasis impairments causing protein misfolding and aggregation have also been shown to have gain of function effects that disrupt neuronal functions. As the term implies, such effects cannot be recapitulated simply by the reduction or deletion of the aggregation-prone protein of interest but are caused by the enhanced recruitment and sequestration of interacting proteins into the misfolded and aggregated assemblies formed by the conformationally-altered proteins. An example of this observation is the abnormal enhancement in interaction between p62 and GABARAPs in autophagy-deficient neurons (46,65). p62 belongs to a group of proteins which act as autophagic cargo receptors that recognize ubiquitinated proteins and target them to autophagosomes for degradation through interactions with LC3 (66). In these studies, autophagy was impaired in Atg7 knockout (KO) or Ulk2 heterozygous mice, which consequently led to the accumulation and formation of p62+ aggregates and thus they, along with its cargo, no longer can be degraded by autophagy. The aggregates in turn sequester and effectively reduce the functional pool of GABARAPs required for the proper trafficking of GABAA receptors to the cell surface. The resulting reduction of surface GABAA receptors decreased inhibitory GABAergic neurotransmission, thereby disrupting excitatory-inhibitory (E-I) balance in affected brains and causing ASD and SZ-like behavioural deficits. A similar gain of function effect was observed for purified DISC1+ aggresomes (47), as they could recruit and sequester heterologous dysbindin, a protein previously linked to SZ (67). Although the functional consequences of this aberrant sequestration was not determined, the authors speculated that the mislocalization and reduction of a significant soluble pool of dysbindin would likely have compromised its functions.

As demonstrated by these studies, the interplay or co-aggregation between distinct proteins is of interest, since they could result in much broader effects. Notably, in addition to being sequestered into aggregates formed by proteins associated with neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., huntingtin and TDP-43) (68,69), DISC1 itself has also been demonstrated to enhance the aggregation propensity of other proteins such as dysbindin and CRMP1 (47,48). Given the intrinsic ability of DISC1 to form aggregates spontaneously (68) and interact with various proteins (70), it will be of interest to examine which interacting partners are also sequestered and differentially aggregated in the brains of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders. For instance, studies have shown how alterations in cellular environment can influence the propensity of DISC1 to undergo misfolding and aggregation. It was previously demonstrated that the level of dopamine can enhance DISC1 aggregation (61), and a recent study revealed that viral infection increases the expression of α-synuclein and DISC1 by disrupting their clearance via autophagy, thereby tipping the balance towards their aggregation (71). Furthermore, functional studies to examine how the conformationally-altered proteins and other proteins which were secondarily recruited into them impact neuronal functions will provide novel insights into how impaired proteostasis ultimately leads to pathophysiological changes.

Finally, it should be noted that there have also been demonstrations of “functional” aggregates of proteins such as CPEB and Orb2 (72–74). Whereas the discussion presented here on protein misfolding and aggregation primarily focused on their detrimental effects on neuronal and synaptic functions relating to neuropsychiatric disorders, some regulated conformational changes to functional prion-like aggregates or amyloids are required for proper brain functions. Many important questions regarding the distinguishing features between functional and disease-causing protein aggregates and the molecular mechanisms underlying their conformational switches remain to be addressed (72,73). New insights into these functional aggregates will provide a better understanding of the misfolding and aggregation of proteins associated with neuropsychiatric disorders, and perhaps lead to novel strategies to prevent or reverse the aberrant conformational changes of the disease-causing proteins.

Potential involvement of ER and mitochondria quality control pathways

Aside from direct effects caused by misfolded and aggregated proteins due to the aforementioned loss and gain of function mechanisms, disturbances in proteostasis may further disrupt neuronal and synaptic functions by overwhelming cellular cytoprotective pathways. We will next discuss about two signalling pathways which normally provide the cell with additional means to maintain proteostasis but, once overwhelmed, may become vulnerable and consequently exacerbate the pathology of neuropsychiatric disorders.

As described previously, alterations in ER quality control pathways have been observed in both post-mortem brain samples or leukocytes collected from SZ (36,37), BD (39,41,45), and MDD (35,38,42) patients. These pathways, including ERAD and UPR, are activated due to ER stress caused by protein misfolding within the ER (Figure 2). ETPR consists of three major pathways involving activating transcription factor (ATF6), inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endoribonuclease 1α (IRE1α), and PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) (74). Whereas the ATF6 and IRE1α pathways mainly act to enhance the ER protein folding capacity via transcriptional mechanisms, PERK induces an ATF4-dependent transcriptional response but also activates ISR, which suppresses global protein synthesis in a eIF2α-dependent manner (75). Notably, by using patient-derived samples from various neurodegenerative disorders, these pathways were previously shown to be activated in response to the increased ER stress caused by proteostasis impairments and contribute to the disorders (76–80). Their aberrant activation may therefore contribute to neuropsychiatric disorders in a similar manner.

Although it remains unclear precisely how abnormal activation of these ER quality control pathways disrupts neuronal functions and contribute to pathophysiology, there is evidence that hints at their involvements in neuropsychiatric disorders. Several ASD-associated mutations in synaptic cell adhesion molecules such as neuroligin-3 and −4, CNTNAP2, and CADM1 were found to impair their trafficking to the cell surface and cause them to accumulate in the ER, thereby activating UPR (81–86). Notably, the synaptic deficits of NLGN3 R451C mutant mice were rescued by suppressing one of the downstream UPR pathways (86), thus highlighting its potential involvement. Furthermore, ER stress induced by tunicamycin treatment alone was found to elicit social behavioural deficits and abnormal hyperactive brain connectivity in an UPR-dependent manner (87). By contrast, protein levels of PERK and ATF4 were observed to be reduced in SZ patients and forebrain-specific PERK deletion resulted in SZ-associated behavioural deficits (88). Together, these studies indicate that disturbances in ER-mediated protein folding and trafficking caused by abnormal ER stress response may contribute to the development of neuropsychiatric disorders, and therefore warrants further investigations.

In addition, the global shutdown of protein synthesis induced by phosphorylated eIF2α can lead to deficits in synaptic plasticity (89–91) and in turn contribute to the pathophysiological changes that occur in neuropsychiatric disorders. Notably, aberrant UPR/ISR activation leading to increased eIF2α phosphorylation has been shown to contribute to the pathophysiology in neurodegenerative disorders, as genetic and pharmacologic inhibitions of eIF2α were previously demonstrated to reverse learning and memory deficits in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease (92–96). To date, two studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of pharmacological inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation in mouse models of neuropsychiatric disorders (97,98), thereby revealing a detrimental role of eIF2α phosphorylation in their pathophysiology. Further work to examine whether inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation provides rescue effects in additional animal models or iPSC-derived cell models will be crucial in understanding how the aberrant eIF2α phosphorylation by UPR/ISR overactivation contributes to the pathophysiology of these disorders.

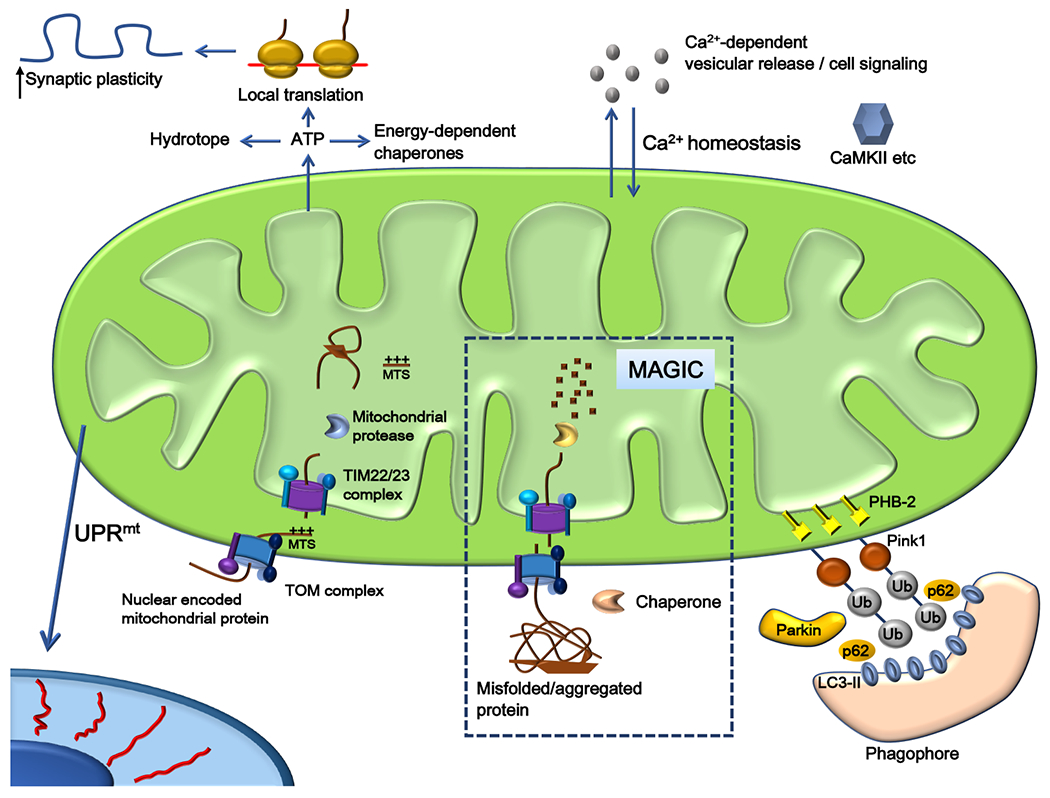

Aside from the endoplasmic reticulum, the mitochondrion is another organelle of interest that may be affected by disrupted proteostasis and contribute to neuropsychiatric disorders. Recent studies have revealed the mitochondrion to be involved in proteostasis in a direct manner (Figure 3). Specifically, a recent study identified ATP as a hydrotrope and demonstrated its ability to directly prevent liquid-liquid phase separation and protein aggregation (99). As such, mitochondrial ATP production may be crucial for protein homeostasis. In addition, a process termed mitochondria as guardian in cytosol (MAGIC) was recently described in yeast that can import a suite of aggregation-prone cytosolic proteins into the mitochondria for their degradation (100). Because most mitochondrial proteins are encoded by the nuclear genome, they are typically translated in the cytosol and imported into the mitochondria via the translocases of the outer membrane (TOM) and the inner membrane (TIM) complexes (101). An elaborate network of proteases and chaperones then ensures proper folding and targeting of these imported proteins to the different mitochondrial compartments. In particular, MAGIC utilizes the TOM (Tom70 and Tom40) and TIM (Tim23) complexes to import cytosolic protein aggregates and degrades them using the mitochondrial protease Pim1. In human cells, a similar pathway involving the FUNDC1-HSC70 interaction and LONP1 mitochondrial protease was found to be crucial for the translocation and degradation of mitochondrion-associated protein aggregates (MAPAs) (102). Hence, there appears to be an evolutionarily-conserved pathway that allows the mitochondrion to provide an additional means to deal with cytosolic protein aggregates when cytosolic proteostasis is impaired. Notably, the import of cytosolic protein aggregates into the mitochondria also allows for their temporary storage and subsequent bulk removal via mitophagy, the process through which whole mitochondria are degraded by autophagy (103).

Figure 3. Involvement and vulnerability of mitochondria.

Nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins are normally imported by the TOM/TIM complexes and processed into mature proteins by mitochondrial proteases. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) is triggered by a decline in mitochondrial protein import to compensate and correct for these changes. Recently, a process called MAGIC was shown to utilize the mitochondrial protein import machinery to transport misfolded and aggregated proteins into the mitochondria for degradation. This was further hypothesized as a means to ensure proper removal of misfolded and aggregated proteins as the mitochondria can be selectively removed via mitophagy. However, the import of problematic proteins into the mitochondria may also lead to mitochondrial dysfunctions if they are not properly dealt with in a timely manner. Critical mitochondrial functions such as Ca2+ homeostasis and ATP production may be disrupted and further disturb neuronal functions such as vesicular release and local translation, and could in turn greatly impact neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity, respectively.

However, the mitochondrion’s ability to handle misfolded and aggregated proteins, either formed internally or imported from the cytosol, is not unlimited. Hence, a mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt), which involves mitochondria-to-nucleus communication to initiate a transcriptional program to restore mitochondrial proteostasis, is triggered upon mitochondrial dysfunction (104–108). Notably, UPRmt and mitochondrial functions were dysregulated in response to Aβ-induced proteotoxic stress and UPRmt induction provided protective effects (109), thus implicating mitochondria in coping with impaired proteostasis. It will be of interest to examine in patient samples for abnormal UPRmt activation or alterations to the pathway as an additional marker of proteostasis impairment since it has yet to be examined in the context of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Given the mitochodrion’s direct role in proteostasis via MAGIC and UPRmt, disruptions of proteostasis in affected neurons could potentially overwhelm such pathways and in turn affect mitochondrial functions. While mitochondrial defects have traditionally been associated with various neuropathies and myopathies, recent studies have identified mitochondrial dysfunctions in patient samples and animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders, most notably for BD and ASD (110–119). Since the mitochondrion has been shown to directly dysregulate neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity through its involvement in ATP production and calcium homeostasis (120–127), mitochondrial dysfunction may further exacerbate the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders by impairing such functions.

Conclusion

Despite the complexity of neuropsychiatric disorders, genetic studies during the past decades have clarified a genome-wide landscape of genetic risk for these disorders. Nonetheless, genetic factors still cannot explain the full pathology of many sporadic cases. Accordingly, it is important to consider how cellular environments impact protein structure, and in turn the propensity for protein misfolding and aggregation. Although these cellular environmental factors alone unlikely trigger proteostasis impairments and result in pathophysiology, they may be disease modifying factors that enhances susceptibility or influence severity of the disorders. Further understanding of how genetic and cellular environmental factors conceitedly impact proteostasis will provide new insights into how they ultimately contribute to the observed pathophysiologic changes.

The involvement of impaired proteostasis in neuropsychiatric disorders reviewed here helps to explain, at least in part, the complex nature of these disorders. The additive effects of multiple subtle perturbations in protostasis combine together to result in system-wide deficits through various loss and gain of function mechanisms which are inherent to protein misfolding and aggregation. Recent studies have implicated impaired proteostasis to be a key underlying mechanisms for these disorders and illustrated how such disruptions may contribute to the pathophysiological process. Historically, the study of various neurodegenerative disorders began with traditional microscopic observations of insoluble proteinaceous deposits in affected neuronal subpopulations using biopsy and post-mortem brain samples from patients, which was followed by molecular dissection of such insoluble materials. The molecules identified in this process are now regarded as key leads for mechanistic understanding and biomarkers for neurodegenerative disorders. We may optimistically hope for similar success in research on neuropsychiatric disorders in the future. In order to achieve this goal, a continued search for additional disease-associated aggregation-prone proteins may be fruitful. Since neuropsychiatric disorders are not characterized by visible protein aggregates via histological analyses, future efforts to identify new aggregation-prone proteins involved in pathophysiology will need to be made primarily through biochemical approaches. By utilizing unbiased approaches such as epitope discovery and quantitative mass spectrometry like those employed to identify CRMP1 and GABARAPL2 (46,48), novel aggregation-prone candidate proteins and their interactomes can be identified using brain samples from patients and iPSC-derived neurons or brain organoids (128).

In addition to identifying new pathogenic aggregation-prone proteins, it will be critical to determine precisely how the changes in protein abundance, conformation, and/or aggregation status identified in patient samples (Table 1) ultimately impact protein homeostasis, and in turn disturb neuronal and synaptic functions. Once additional proteins have been validated for their associations with the disorders, they can in turn be used as a biochemical endophenotype through which patients may be classified into subgroups for mechanistic studies to better understand the causes and consequences of the underlying disturbances in proteostasis. Such an experimental strategy may provide a possible means of establishing these candidate aggregation-prone proteins as new markers for research and possibly for diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge funding support from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan (20H00501, 20H04720, 19H04763), Takeda Science Foundation, Nakatani Foundation, RIKEN Aging Project, AMED Brain/MINDS Project (JP21dm0207001, M.T.), National Institutes of Mental Health (MH-092443, MH-094268, MH-105660, MH-107730), Stanley, RUSK, S-R foundations (A.S.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures

The authors reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, EdS1 Washington A, Patrick, et al. (2020): Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. Mmwr Surveill Summ 69: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreno-Küstner B, Martín C, Pastor L (2018): Prevalence of psychotic disorders and its association with methodological issues. A systematic review and meta-analyses. Plos One 13: e0195687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J (2005): A Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Schizophrenia. Plos Med 2: e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai PR, Lawson KA, Barner JC, Rascati KL (2013): Estimating the direct and indirect costs for community- dwelling patients with schizophrenia. J Pharm Heal Serv Res 4: 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WU EQ, SHI L, BIRNBAUM H, HUDSON T, KESSLER R (2006): Annual prevalence of diagnosed schizophrenia in the USA: a claims data analysis approach. Psychol Med 36: 1535–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IRH, Gagnon E, Guyer M, et al. (2005): The Prevalence and Correlates of Nonaffective Psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biol Psychiat 58: 668–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005): Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiat 62: 617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Administration SA and MHS (2019): Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veltman JA, Brunner HG (2012): De novo mutations in human genetic disease. Nat Rev Genet 13:565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dill KA, Ozkan SB, Shell MS, Weikl TR (2008): The protein folding problem. Annu Rev Biophys 37: 289–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciechanover A, Kwon YT (2015): Degradation of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic targets and strategies. Exp Mol Med 47: e147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meusser B, Hirsch C, Jarosch E, Sommer T (2005): ERAD: the long road to destruction. Nat Cell Biol 7: 766–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y-J, Xu Y-F, Cook C, Gendron TF, Roettges P, Link CD, et al. (2009): Aberrant cleavage of TDP-43 enhances aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc National Acad Sci 106: 7607–7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lv L, Li D, Zhao D, Lin R, Chu Y, Zhang H, et al. (2011): Acetylation Targets the M2 Isoform of Pyruvate Kinase for Degradation through Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy and Promotes Tumor Growth. Mol Cell 42: 719–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson LM, Aiken CT, Kaltenbach LS, Agrawal N, Illes K, Khoshnan A, et al. (2009): IKK phosphorylates Huntingtin and targets it for degradation by the proteasome and lysosome. J Cell Biology 187: 1083–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross CA, Poirier MA (2004): Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med 10: S10–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conway KA, Harper JD, Lansbury PT (1998): Accelerated in vitro fibril formation by a mutant α-synuclein linked to early-onset Parkinson disease. Nat Med 4: 1318–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, Suzuki N, et al. (1996): Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 2: 864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duff K, Eckman C, Zehr C, Yu X, Prada CM, Perez-tur J, et al. (1996): Increased amyloid-beta42(43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1. Nature 383: 710–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borchelt DR, Ratovitski T, Lare J van, Lee MK, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, et al. (1997): Accelerated Amyloid Deposition in the Brains of Transgenic Mice Coexpressing Mutant Presenilin 1 and Amyloid Precursor Proteins. Neuron 19: 939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borchelt DR, Thinakaran G, Eckman CB, Lee MK, Davenport F, Ratovitsky T, et al. (1996): Familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Abeta1-42/1-40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 17: 1005–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fricker M, Tolkovsky AM, Borutaite V, Coleman M, Brown GC (2018): Neuronal Cell Death. Physiol Rev 98: 813–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merenlender-Wagner A, Malishkevich A, Shemer Z, Udawela M, Gibbons A, Scarr E, et al. (2015): Autophagy has a key role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 20:126–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alcocer- Gómez E, Casas- Barquero N, Núñez- Vasco J, Navarro- Pando JM, Bullón P (2017): Psychological status in depressive patients correlates with metabolic gene expression. CNS Neurosci Ther 23: 843–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scaini G, Barichello T, Fries GR, Kennon EA, Andrews T, Nix BR, et al. (2019): TSPO upregulation in bipolar disorder and concomitant downregulation of mitophagic proteins and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Neuropsychopharmacology 44: 1291–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott MR, Meador-Woodruff JH (2019): Intracellular compartment-specific proteasome dysfunction in postmortem cortex in schizophrenia subjects. Mol Psychiatry 25: 776–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott MR, Rubio MD, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH (2015): Protein Expression of Proteasome Subunits in Elderly Patients with Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 41: 896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altar CA, Jurata LW, Charles V, Lemire A, Liu P, Bukhman Y, et al. (2005): Deficient Hippocampal Neuron Expression of Proteasome, Ubiquitin, and Mitochondrial Genes in Multiple Schizophrenia Cohorts. Biol Psychiatry 58: 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vawter MP, Crook JM, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR, Becker KG, Freed WJ (2002): Microarray analysis of gene expression in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Schizophr Res 58: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meiklejohn H, Mostaid MS, Luza S, Mancuso SG, Kang D, Atherton S, et al. (2019): Blood and brain protein levels of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2K (UBE2K) are elevated in individuals with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 113: 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohlbrenner EA, Shaskan N, Pietersen CY, Sonntag K-C, Woo T-UW (2018): Gene expression profile associated with postnatal development of pyramidal neurons in the human prefrontal cortex implicates ubiquitin ligase E3 in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia onset. J Psychiatr Res 102: 110–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Middleton FA, Mirnics K, Pierri JN, Lewis DA, Levitt P (2002): Gene Expression Profiling Reveals Alterations of Specific Metabolic Pathways in Schizophrenia. J Neurosci 22: 2718–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubio MD, Wood K, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH (2013): Dysfunction of the ubiquitin proteasome and ubiquitin-like systems in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 38: 1910–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vawter MP, Barrett T, Cheadle C, Sokolov BP, Wood WH, Donovan DM, et al. (2001): Application of cDNA microarrays to examine gene expression differences in schizophrenia. Brain Res Bull 55: 641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nevell L, Zhang K, Aiello AE, Koenen K, Galea S, Soliven R, et al. (2014): Elevated systemic expression of ER stress related genes is associated with stress-related mental disorders in the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 43: 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim P, Scott MR, Meador-Woodruff JH (2018): Abnormal expression of ER quality control and ER associated degradation proteins in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 197: 484–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim P, Scott MR, Meador-Woodruff JH (2021): Dysregulation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in elderly patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 26: 1321–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bown C, Wang J-F, MacQueen G, Young LT (2000): Increased Temporal Cortex ER Stress Proteins in Depressed Subjects Who Died by Suicide. Neuropsychopharmacology 22: 327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bengesser SA, Reininghaus EZ, Dalkner N, Birner A, Hohenberger H, Queissner R, et al. (2018): Endoplasmic reticulum stress in bipolar disorder? — BiP and CHOP gene expression- and XBP1 splicing analysis in peripheral blood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 95: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crider A, Ahmed AO, Pillai A (2017): Altered Expression of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Related Genes in the Middle Frontal Cortex of Subjects with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mol Neuropsychiatry 3: 85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.So J, Warsh JJ, Li PP (2007): Impaired Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response in B-Lymphoblasts From Patients With Bipolar-I Disorder. Biol Psychiatry 62: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshino Y, Dwivedi Y (2020): Elevated expression of unfolded protein response genes in the prefrontal cortex of depressed subjects: Effect of suicide. J Affect Disord 262: 229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bousman CA, Luza S, Mancuso SG, Kang D, Opazo CM, Mostaid MdS, et al. (2019): Elevated ubiquitinated proteins in brain and blood of individuals with schizophrenia. Sci Rep 9: 2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nucifora LG, MacDonald ML, Lee BJ, Peters ME, Norris AL, Orsburn BC, et al. (2019): Increased Protein Insolubility in Brains From a Subset of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 176: 730–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfaffenseller B, Wollenhaupt-Aguiar B, Fries GR, Colpo GD, Burque RK, Bristot G, et al. (2014): Impaired endoplasmic reticulum stress response in bipolar disorder: cellular evidence of illness progression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 17: 1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hui KK, Takashima N, Watanabe A, Chater TE, Matsukawa H, Nekooki-Machida Y, et al. (2019): GABARAPs dysfunction by autophagy deficiency in adolescent brain impairs GABAA receptor trafficking and social behavior. Sci Adv 5: eaau8237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ottis P, Bader V, Trossbach SV, Kretzschmar H, Michel M, Leliveld SR, Korth C (2011): Convergence of Two Independent Mental Disease Genes on the Protein Level: Recruitment of Dysbindin to Cell-Invasive Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 Aggresomes. Biol Psychiatry 70: 604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bader V, Tomppo L, Trossbach SV, Bradshaw NJ, Prikulis I, Leliveld SR, et al. (2012): Proteomic, genomic and translational approaches identify CRMP1 for a role in schizophrenia and its underlying traits. Hum Mol Genet 21: 4406–4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leliveld SR, Bader V, Hendriks P, Prikulis I, Sajnani G, Requena JR, Korth C (2008): Insolubility of disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 disrupts oligomer-dependent interactions with nuclear distribution element 1 and is associated with sporadic mental disease. J Neurosci 28: 3839–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bradshaw NJ, Bader V, Prikulis I, Lueking A, Müllner S, Korth C (2014): Aggregation of the protein TRIOBP-1 and its potential relevance to schizophrenia. PLoS One 9: e111196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lennox AL, Hoye ML, Jiang R, Johnson-Kerner BL, Suit LA, Venkataramanan S, et al. (2020): Pathogenic DDX3X Mutations Impair RNA Metabolism and Neurogenesis during Fetal Cortical Development. Neuron 106: 404–420.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nucifora LG, Wu YC, Lee BJ, Sha L, Margolis RL, Ross CA, et al. (2016): A Mutation in NPAS3 That Segregates with Schizophrenia in a Small Family Leads to Protein Aggregation. Mol Neuropsychiatry 2: 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leliveld SR, Hendriks P, Michel M, Sajnani G, Bader V, Trossbach S, et al. (2009): Oligomer assembly of the C-terminal DISC1 domain (640-854) is controlled by self-association motifs and disease-associated polymorphism S704C. Biochemistry 48: 7746–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schweitzer JS, Song B, Herrington TM, Park T-Y, Lee N, Ko S, et al. (2020): Personalized iPSC-Derived Dopamine Progenitor Cells for Parkinson’s Disease. New Engl J Med 382: 1926–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qian H, Kang X, Hu J, Zhang D, Liang Z, Meng F, et al. (2020): Reversing a model of Parkinson’s disease with in situ converted nigral neurons. Nature 582: 550–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Narayanan S, Arthanari H, Wolfe MS, Wagner G (2011): Molecular Characterization of Disrupted in Schizophrenia-1 Risk Variant S704C Reveals the Formation of Altered Oligomeric Assembly. J Biol Chem 286: 44266–44276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamiya A, Kubo K, Tomoda T, Takaki M, Youn R, Ozeki Y, et al. (2005): A schizophrenia-associated mutation of DISC1 perturbs cerebral cortex development. Nat Cell Biol 7: 1167–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hikida T, Jaaro-Peled H, Seshadri S, Oishi K, Hookway C, Kong S, et al. (2007): Dominant-negative DISC1 transgenic mice display schizophrenia-associated phenotypes detected by measures translatable to humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 14501–14506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pletnikov MV, Ayhan Y, Nikolskaia O, Xu Y, Ovanesov MV, Huang H, et al. (2008): Inducible expression of mutant human DISC1 in mice is associated with brain and behavioral abnormalities reminiscent of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 13: 173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li W, Zhou Y, Jentsch JD, Brown RAM, Tian X, Ehninger D, et al. (2007): Specific developmental disruption of disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1 function results in schizophrenia-related phenotypes in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 18280–18285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trossbach SV, Bader V, Hecher L, Pum ME, Masoud ST, Prikulis I, et al. (2016): Misassembly of full-length Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 protein is linked to altered dopamine homeostasis and behavioral deficits. Mol Psychiatry 21: 1561–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang A-L, Chao OY, Yang Y-M, Trossbach SV, Müller CP, Korth C, et al. (2019): Anxiogenic-like behavior and deficient attention/working memory in rats expressing the human DISC1 gene. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 179: 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaefer K, Malagon- Vina H, Dickerson DD, O’Neill J, Trossbach SV, Korth C, Csicsvari J (2019): Disrupted- in- schizophrenia 1 overexpression disrupts hippocampal coding and oscillatory synchronization. Hippocampus 29: 802–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang A-L, Fazari B, Chao OY, Nikolaus S, Trossbach SV, Korth C, et al. (2017): Intranasal dopamine alleviates cognitive deficits in tgDISC1 rats which overexpress the human DISC1 gene. Neurobiol Learn Mem 146: 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sumitomo A, Yukitake H, Hirai K, Horike K, Ueta K, Chung Y, et al. (2018): Ulk2 controls cortical excitatory—inhibitory balance via autophagic regulation of p62 and GABAA receptor trafficking in pyramidal neurons. Hum Mol Genet 147: 728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun J-A, Outzen H, et al. (2007): p62/SQSTM1 Binds Directly to Atg8/LC3 to Facilitate Degradation of Ubiquitinated Protein Aggregates by Autophagy. J Biol Chem 282: 24131–24145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Straub RE, Jiang Y, MacLean CJ, Ma Y, Webb BT, Myakishev MV, et al. (2002): Genetic Variation in the 6p22.3 Gene DTNBP1, the Human Ortholog of the Mouse Dysbindin Gene, Is Associated with Schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 71: 337–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tanaka M, Ishizuka K, Nekooki-Machida Y, Endo R, Takashima N, Sasaki H, et al. (2017): Aggregation of scaffolding protein DISC1 dysregulates phosphodiesterase 4 in Huntington’s disease. J Clin Invest 127: 1438–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Endo R, Takashima N, Nekooki-Machida Y, Komi Y, Hui KK-W, Takao M, et al. (2018): TAR DNA-Binding Protein 43 and Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 Coaggregation Disrupts Dendritic Local Translation and Mental Function in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Biol Psychiatry 84: 509–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Camargo LM, Collura V, Rain J-C, Mizuguchi K, Hermjakob H, Kerrien S, et al. (2006): Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 Interactome: evidence for the close connectivity of risk genes and a potential synaptic basis for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 12: 74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marreiros R, Müller-Schiffmann A, Trossbach SV, Prikulis I, Hänsch S, Weidtkamp-Peters S, et al. (2020): Disruption of cellular proteostasis by H1N1 influenza A virus causes α-synuclein aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117: 6741–6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Otzen D, Riek R (2019): Functional Amyloids. Csh Perspect Biol 11: a033860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rayman JB, Kandel ER (2017): Functional Prions in the Brain. Csh Perspect Biol 9: a023671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walter P, Ron D (2011): The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334: 1081–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N (2009): Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron 61: 10–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chang RCC, Wong AKY, Ng H-K, Hugon J (2002): Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2alpha (eIF2alpha) is associated with neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport 13: 2429–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoozemans JJM, Haastert ESV, Eikelenboom P, Vos RAI de, Rozemuller JM, Scheper W (2007): Activation of the unfolded protein response in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 354: 707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoozemans JJM, Veerhuis R, Haastert ESV, Rozemuller JM, Baas F, Eikelenboom P, Scheper W (2005): The unfolded protein response is activated in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 110: 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bando Y, Onuki R, Katayama T, Manabe T, Kudo T, Taira K, Tohyama M (2005): Double-strand RNA dependent protein kinase (PKR) is involved in the extrastriatal degeneration in Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Neurochem Int 46: 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peel AL, Rao RV, Cottrell BA, Hayden MR, Ellerby LM, Bredesen DE (2001): Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR, binds preferentially to Huntington’s disease (HD) transcripts and is activated in HD tissue. Hum Mol Genet 10: 1531–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fujita E, Dai H, Tanabe Y, Zhiling Y, Yamagata T, Miyakawa T, et al. (2010): Autism spectrum disorder is related to endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by mutations in the synaptic cell adhesion molecule, CADM1. Cell Death Dis 1: e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Comoletti D, Jaco AD, Jennings LL, Flynn RE, Gaietta G, Tsigelny I, et al. (2004): The Arg451Cys-Neuroligin-3 Mutation Associated with Autism Reveals a Defect in Protein Processing. J Neurosci 24: 4889–4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang C, Milunsky JM, Newton S, Ko J, Zhao G, Maher TA, et al. (2009): A neuroligin-4 missense mutation associated with autism impairs neuroligin-4 folding and endoplasmic reticulum export. J Neurosci 29: 10843–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ulbrich L, Favaloro FL, Trobiani L, Marchetti V, Patel V, Pascucci T, et al. (2015): Autism-associated R451C mutation in neuroligin3 leads to activation of the unfolded protein response in a PC12 Tet-On inducible system. Biochem J 473: 423–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Falivelli G, Jaco AD, Favaloro FL, Kim H, Wilson J, Dubi N, et al. (2012): Inherited genetic variants in autism-related CNTNAP2 show perturbed trafficking and ATF6 activation. Hum Mol Genet 21: 4761–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Trobiani L, Favaloro FL, Castro MAD, Mattia MD, Cariello M, Miranda E, et al. (2018): UPR activation specifically modulates glutamate neurotransmission in the cerebellum of a mouse model of autism. Neurobiol Dis 120: 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crider A, Nelson T, Davis T, Fagan K, Vaibhav K, Luo M, et al. (2018): Estrogen Receptor β Agonist Attenuates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Changes in Social Behavior and Brain Connectivity in Mice. Mol Neurobiol 55: 7606–7618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Trinh MA, Kaphzan H, Wek RC, Pierre P, Cavener DR, Klann E (2012): Brain-specific disruption of the eIF2α kinase PERK decreases ATF4 expression and impairs behavioral flexibility. Cell Rep 1: 676–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Costa-Mattioli M, Gobert D, Stern E, Gamache K, Colina R, Cuello C, et al. (2007): eIF2α Phosphorylation Bidirectionally Regulates the Switch from Short- to Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity and Memory. Cell 129: 195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Costa-Mattioli M, Gobert D, Harding H, Herdy B, Azzi M, Bruno M, et al. (2005): Translational control of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory by the eIF2α kinase GCN2. Nature 436: 1166–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Prisco GVD, Huang W, Buffington SA, Hsu C-C, Bonnen PE, Placzek AN, et al. (2014): Translational control of mGluR-dependent long-term depression and object-place learning by eIF2α. Nat Neurosci 17: 1073–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ma T, Trinh MA, Wexler AJ, Bourbon C, Gatti E, Pierre P, et al. (2013): Suppression of eIF2α kinases alleviates Alzheimer’s disease-related plasticity and memory deficits. Nat Neurosci 16: 1299–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Devi L, Ohno M (2014): PERK mediates eIF2α phosphorylation responsible for BACE1 elevation, CREB dysfunction and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 35: 2272–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang W, Zhou X, Zimmermann HR, Cavener DR, Klann E, Ma T (2016): Repression of the eIF2α kinase PERK alleviates mGluR-LTD impairments in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 41: 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Segev Y, Barrera I, Ounallah-Saad H, Wibrand K, Sporild I, Livne A, et al. (2015): PKR Inhibition Rescues Memory Deficit and ATF4 Overexpression in ApoE ε4 Human Replacement Mice. J Neurosci 35: 12986–12993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Couturier J, Paccalin M, Lafay-Chebassier C, Chalon S, Ingrand I, Pinguet J, et al. (2012): Pharmacological inhibition of PKR in APPswePS1dE9 mice transiently prevents inflammation at 12 months of age but increases Aβ42 levels in the late stages of the Alzheimer’s disease. Carr Alzheimer Res 9: 344–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kabir ZD, Che A, Fischer DK, Rice RC, Rizzo BK, Byrne M, et al. (2017): Rescue of impaired sociability and anxiety-like behavior in adult cacna1c-deficient mice by pharmacologically targeting eIF2α. Mol Psychiatry 22: 1096–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhu PJ, Khatiwada S, Cui Y, Reineke LC, Dooling SW, Kim JJ, et al. (2019): Activation of the ISR mediates the behavioral and neurophysiological abnormalities in Down syndrome. Science 366: 843–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patel A, Malinovska L, Saha S, Wang J, Alberti S, Krishnan Y, Hyman AA (2017): ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science 356: 753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ruan L, Zhou C, Jin E, Kucharavy A, Zhang Y, Wen Z, et al. (2017): Cytosolic proteostasis through importing of misfolded proteins into mitochondria. Nature 443: 787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pfanner N, Warscheid B, Wiedemann N (2019): Mitochondrial proteins: from biogenesis to functional networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20: 267–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li Y, Xue Y, Xu X, Wang G, Liu Y, Wu H, et al. (2019): A mitochondrial FUNDC1/HSC70 interaction organizes the proteostatic stress response at the risk of cell morbidity. EMBO J 38: e98786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kissová I, Deffieu M, Manon S, Camougrand N (2004): Uth1p Is Involved in the Autophagic Degradation of Mitochondria. J Biol Chem 279: 39068–39074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhao Q, Wang J, Levichkin IV, Stasinopoulos S, Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ (2002): A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells. EMBO J 21: 4411–4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yoneda T, Benedetti C, Urano F, Clark SG, Harding HP, Ron D (2004): Compartment-specific perturbation of protein handling activates genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. J Cell Sci 117: 4055–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nargund AM, Pellegrino MW, Fiorese CJ, Baker BM, Haynes CM (2012): Mitochondrial Import Efficiency of ATFS-1 Regulates Mitochondrial UPR Activation. Science 337: 587–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Haynes CM, Yang Y, Blais SP, Neubert TA, Ron D (2010): The Matrix Peptide Exporter HAF-1 Signals a Mitochondrial UPR by Activating the Transcription Factor ZC376.7 in C. elegans. Mol Cell 37: 529–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu Y, Samuel BS, Breen PC, Ruvkun G (2014): Caenorhabditis elegans pathways that surveil and defend mitochondria. Nature 508: 406–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sorrentino V, Romani M, Mouchiroud L, Beck JS, Zhang H, D’Amico D, et al. (2017): Enhancing mitochondrial proteostasis reduces amyloid-β proteotoxicity. Nature 552: 187–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kato TM, Kubota-Sakashita M, Fujimori-Tonou N, Saitow F, Fuke S, Masuda A, et al. (2018): Ant1 mutant mice bridge the mitochondrial and serotonergic dysfunctions in bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 23: 2039–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Licznerski P, Park H-A, Rolyan H, Chen R, Mnatsakanyan N, Miranda P, et al. (2020): ATP Synthase c-Subunit Leak Causes Aberrant Cellular Metabolism in Fragile X Syndrome. Cell 182: 1170–1185.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Kato T (2005): Altered expression of mitochondria-related genes in postmortem brains of patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, as revealed by large-scale DNA microarray analysis. Hum Mol Genet 14: 241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kasahara T, Kubota M, Miyauchi T, Noda Y, Mouri A, Nabeshima T, Kato T (2006): Mice with neuron-specific accumulation of mitochondrial DNA mutations show mood disorder-like phenotypes. Mol Psychiatry 11: 577–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kasahara T, Takata A, Kato TM, Kubota-Sakashita M, Sawada T, Kakita A, et al. (2016): Depression-like episodes in mice harboring mtDNA deletions in paraventricular thalamus. Mol Psychiatry 21: 39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kanellopoulos AK, Mariano V, Spinazzi M, Woo YJ, McLean C, Pech U, et al. (2020): Aralar Sequesters GABA into Hyperactive Mitochondria, Causing Social Behavior Deficits. Cell 180: 1178–1197.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Goh S, Dong Z, Zhang Y, DiMauro S, Peterson BS (2014): Mitochondrial dysfunction as a neurobiological subtype of autism spectrum disorder: evidence from brain imaging. JAMA Psychiatry 71: 665–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Giulivi C, Zhang Y-F, Omanska-Klusek A, Ross-Inta C, Wong S, Hertz-Picciotto I, et al. (2010): Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism. JAMA 304: 2389–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shen M, Wang F, Li M, Sah N, Stockton ME, Tidei JJ, et al. (2019): Reduced mitochondrial fusion and Huntingtin levels contribute to impaired dendritic maturation and behavioral deficits in Fmr1-mutant mice. Nat Neurosci 22: 386–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Weisz ED, Towheed A, Monyak RE, Toth MS, Wallace DC, Jongens TA (2017): Loss of Drosophila FMRP leads to alterations in energy metabolism and mitochondrial function. Hum Mol Genet 27: 95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lewis TL, Kwon S-K, Lee A, Shaw R, Polleux F (2018): MFF-dependent mitochondrial fission regulates presynaptic release and axon branching by limiting axonal mitochondria size. Nat Comms 9: 5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ashrafi G, Juan-Sanz J de, Farrell RJ, Ryan TA (2020): Molecular Tuning of the Axonal Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uniporter Ensures Metabolic Flexibility of Neurotransmission. Neuron 105: 678–687.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rangaraju V, Lauterbach M, Schuman EM (2019): Spatially Stable Mitochondrial Compartments Fuel Local Translation during Plasticity. Cell 176: 73–84.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gazit N, Vertkin I, Shapira I, Helm M, Slomowitz E, Sheiba M, et al. (2016): IGF-1 Receptor Differentially Regulates Spontaneous and Evoked Transmission via Mitochondria at Hippocampal Synapses. Neuron 89: 583–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kwon S-K, Sando R, Lewis TL, Hirabayashi Y, Maximov A, Polleux F (2016): LKB1 Regulates Mitochondria-Dependent Presynaptic Calcium Clearance and Neurotransmitter Release Properties at Excitatory Synapses along Cortical Axons. PLoS Biol 14: e1002516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Vaccaro V, Devine MJ, Higgs NF, Kittler JT (2016): Miro1-dependent mitochondrial positioning drives the rescaling of presynaptic Ca2+ signals during homeostatic plasticity. EMBO Rep 18: 231–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hall CN, Klein-Flügge MC, Howarth C, Attwell D (2012): Oxidative phosphorylation, not glycolysis, powers presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms underlying brain information processing. J Neurosci 32: 8940–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rangaraju V, Calloway N, Ryan TA (2014): Activity-driven local ATP synthesis is required for synaptic function. Cell 156: 825–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Amin ND, Pa§ca SP (2018): Building Models of Brain Disorders with Three-Dimensional Organoids. Neuron 100: 389–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]