Abstract

Clostridioides difficile is naturally resistant to high levels of lysozyme an important component of the innate immune defense system. C. difficile encodes both constitutive as well as inducible lysozyme resistance genes. The inducible lysozyme resistance genes are controlled by an alternative σ factor σV that belongs to the Extracytoplasmic function σ factor family. In the absence of lysozyme, the activity of σV is inhibited by the anti-σ factor RsiV. In the presence of lysozyme RsiV is destroyed via a proteolytic cascade that leads to σV activation and increased lysozyme resistance. This review highlights how activity of σV is controlled.

Keywords: σ factors, cell envelope, stress response, signal transduction, gene expression

Background

Lysozyme is a muramidase that cleaves the β-(1,4)-glycosidic bond between N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) and N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) residues of peptidoglycan, a cell wall polymer that protects bacteria from lysis due to turgor pressure [1]. Lysozymes are produced by many organisms and is an important component of the innate immune response [1]. Lysozymes fall into three broad families C-type (Chicken), G-type (Goose) and I-type (invertebrate) [1]. The most well-studied of these is hen egg white Iysozyme (HEWL) which belongs the C-type lysozyme family. HEWL is homologous to Human C-type lysozyme which is produced by humans in secretions like tears, saliva, and breast milk as well as the lysosomal granules of neutrophils and macrophages [1,2]. This review will focus on the sensing of C-type lysozymes by C. difficile and related organisms.

C. difficile is highly resistant to C-type lysozyme [3,4]. Studies have found that C. difficile is ~1000 times more resistant to lysozyme than the non-pathogenic endospore-forming relative Bacillus subtilis [4–6]. C. difficile is resistant to levels of lysozyme similar to those seen in other opportunistic pathogens and human commensals like Enterococcus faecalis [7,8]. While multiple factors contribute to the high level of lysozyme resistance in C. difficile [3,4,9,10], recent data suggests that peptidoglycan deacetylation is the single most important mechanism [4,11]. Removal of the acetyl group from NAG to produce glucosamine is a well-characterized lysozyme resistance mechanism [1,12], but in C. difficile the peptidoglycan deacetylases PdaV and PgdA exhibit redundant function. Loss of either gene results in a modest increase in lysozyme resistance, while loss of both renders C. difficile ~1000 fold more sensitive to lysozyme [4,11]. Expression of pdaV is highly induced by lysozyme and is dependent upon σV an Extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factor encoded as part of the pdaV operon [3,13]. Control of pgdA expression is not well understood but has been found to be induced ~2-fold by Iysozyme in a mostly σVindependent manner suggesting there may be other factors which contribute to control of pgdA expression [11].

ECF σ factors belong to the σ70 family and are defined by the presence of only the σ2 and σ4.2 domains, which bind the -35 and -10 regions of target promoters [14–17]. Like most ECF σ factors, the activity of σV is inhibited by an anti-σ factor, RsiV (Regulator of σV), which is encoded within the σ factor operon [13]. ECF σ factors are a large and diverse group of σ factors with over a 150 distinct families [18,19]. σV belongs to the ECF30 family of σ factors which, is found almost exclusively within Firmicutes [18,19].

Activation of σV

In C. difficile σV is required for resistance to C-type lysozyme including both HEWL and Human lysozyme [3,4,20,21]. However, σV is not required for resistance to cell wall active antibiotics like ampicillin, bacitracin, colistin, nisin or vancomycin [3]. Like other ECF σ factors σV is held inactive by the transmembrane anti-σ factor RsiV [13,22,23]. σV is activated by C-type lysozymes including HEWL and Human neutrophil lysozyme [3,4,10,11]. However, σV is not activated by antimicrobial peptides like bacitracin and polymyxin [10,13]. A thorough analysis of σV activation was carried out in B. subtilis, and it was found that only C-type lysozyme was able to activate σV but not any cell wall active antibiotics [5]. Surprisingly, other muramidases like mutanolysin and T4 lysozyme failed to activate σV [24]. Interestingly, enzymatically inactive human lysozyme activates σV in B. subtilis [24]. These data argue that it is not the enzymatic activity but rather the presence of C-type lysozyme that induces activation of σV. In E. faecalis, starvation, heat shock, and SDS were reported to increase activation of σV based on northern blots [25]. However the levels of induction observed are low when compared to lysozyme [25]. This suggests that while other conditions can have small effects on σV activity the physiologically relevant inducer for σV activity is C-type lysozymes.

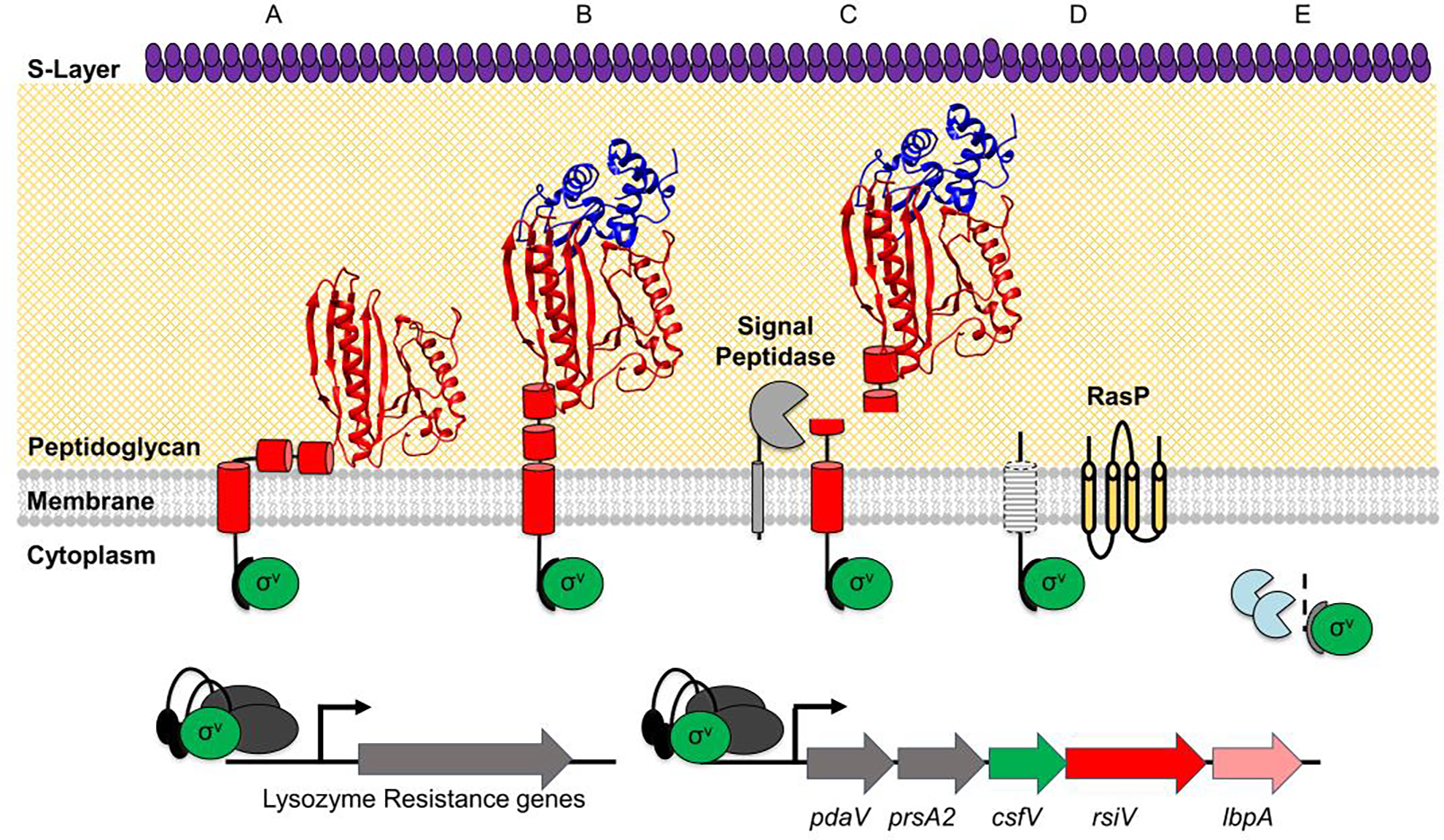

Most ECF σ factors are inactive and require an activation step [14,16–18]. The activity of different families of ECF σ factors are controlled by a variety of mechanisms including; phosphorylation, conformational change of the anti-σ factor which releases the σ factor, partner switching in which an anti-anti-σ factor binds to the anti-σ factor inducing σ factor release, or proteolytic destruction of the anti-σ factor [14,16–18] (Fig. 1). In C. difficile and related organisms, the anti-σ factor RsiV inhibits the activity of σV in the absence of lysozyme [13,23,25] (Fig. 1A). In B. subtilis, C. difficile, and E. faecalis activation of σV is dependent upon the proteolytic destruction of RsiV via two sequential proteolytic steps [20,26,27] (Fig. 1C and 1D). In the presence of lysozyme, RsiV is cleaved at site-1 by signal peptidases [24,26] (Fig. 1C). Once cleaved at site-1, the intramembrane protease RasP cleaves RsiV at site-2 [21,24] (Fig. 1D). This releases the N-terminal ~50 amino acids of RsiV (Fig. 1E). This RsiV fragment is degraded by unidentified cytosolic protease(s) (Fig. 1E). This degradation results in free σV which, can interact with RNA polymerase and direct RNA polymerase to target promoters in the σV regulon (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Model of σV activation.

The σ factor σV is shown in green, the anti-σ factor RsiV is shown in red with cartoon cylinders representing the unsolved residues 1–75. Signal peptidase (Sip) is shown in light gray, the site two protease RasP is shown in yellow, and lysozyme is shown in blue. A) In the absence of lysozyme, RsiV is resistant to signal peptidase cleavage via the interaction of two amphipathic helices with the membrane that restrict access to the cleavage site. In this state RsiV sequesters σV activity and prevents transcription of σV-dependent genes. B) Once RsiV binds lysozyme, the amphipathic helices are forced out of the membrane. C) Signal peptidase is able to access the cleavage site and cleave RsiV to site-1. D) The remaining transmembrane portion of RsiV is cleaved within the membrane by the site-2 protease RasP. E) RsiV is further degraded by cytosolic proteases. FThis allows σV to interact with RNA polymerase dark grey and promote transcription of σV-dependent genes.

This proteolytic signaling cascade is directly activated by lysozyme, with RsiV tightly binding to lysozyme with a binding affinity of ~50 nM. Thus, RsiV functions as a lysozyme receptor, as evidenced by the co-crystal structure of B. subtilis RsiV bound to HEWL. This structure reveals that RsiV binds the active site and substrate-binding site of HEWL [24]. This argues that RsiV is acting as a lysozyme receptor. This was further supported by the co-crystal structure showing RsiV bound to HEWL [28]. In this structure RsiV binds to the active site and substrate-binding site of HEWL, the most conserved regions of C-type lysozyme [28]. Mutational analysis of RsiV revealed that mutations which disrupt the RsiV-HEWL interaction blocked degradation of RsiV and thus blocked activation of σV [28]. Thus, the binding of RsiV to HEWL is the signal that leads to σV activation. While this work was done using the B. subtilis RsiV homolog, both C. difficile and E. faecalis RsiV directly bind HEWL [24].

The binding of lysozyme to RsiV initiates site-1 cleavage and degradation of RsiV. In B. subtilis RsiV is cleaved after the classic A-X-A motif [24,26,29,30]. Changing the alanine of the signal peptidase recognition site at position -1 to a tryptophan blocks site-1 cleavage of RsiV [24]. SipS and SipT are two redundant but essential signal peptidases that are required for site-1 cleavage of RsiV in B. subtilis [26]. Notably, SipS and cleave RsiV only weakly at site-1 in vitro [26]. However, in the presence of lysozyme, signal peptidase cleavage of RsiV at site-1 is greatly enhanced [26]. This is dependent upon the concentration of lysozyme suggesting that the binding of lysozyme to RsiV allows signal peptidase to cleave RsiV at site-1 and initiate σV activation. Interestingly, in C. difficile, the cleavage site appears shifted compared to B. subtilis and mutational analysis reveals the cleavage site is likely V-X-A [24]. In contrast in E. faecalis the cleavage site is more similar to B. subtilis [24].

Evidence from B. subtilis, C. difficile, and E. faecalis shows that site-1 cleavage of RsiV by signal peptidase is the rate-limiting step for σV activation. Cleavage at site-1 is controlled by binding of RsiV to lysozyme. This binding allows signal peptidase to cleave RsiV. However, activity of signal peptidases is not known to be regulated. Thus, RsiV must avoid cleavage by signal peptidase in the absence of lysozyme. Recent evidence suggests RsiV is able to evade cleavage in the absence of lysozyme because the signal peptidase cleavage site is embedded in the membrane as it is part of an amphipathic helix [31]. Indeed placing charged residues on the hydrophobic face of the amphipathic helix resulted in activation of σV in the absence of lysozyme [31]. Importantly substituted cysteine accessibility labeling revealed that the amphipathic face of the helix is inaccessible to labelling by a membrane impermeable reagent [31]. However, upon binding to lysozyme the amphipathic surface was able to be labeled. This argues that RsiV avoids signal peptidase cleavage in the absence of lysozyme because the cleavage site is embedded in the membrane. Upon binding lysozyme, the cleavage site is displaced from the membrane allowing signal peptidase to cleave RsiV at site-1 (Fig. 1). The structure of the extracellular lysozyme binding domain of RsiV bound the HEWL has been solved however the structure of full length RsiV in the presence or absence of lysozyme is not known [28]. Thus, the conformational change that occurs in RsiV when it binds to lysozyme to allow site-1 cleavage and σV activation remains an unanswered question.

σV Regulon

Like most cell stress response systems, σV is induced by a stress and in turn induces genes required for responding to this stress. The regulon of σV has been defined in several Gram-positive bacteria including B. subtilis, E. faecalis and C. difficile [3,6,27,32] and a consensus sequence (-35 tgaAAC and -10 CGTC) has been identified for ECF30-dependent promoters, which includes σV[19]. In each of these organisms the regulon is small (3–5 operons depending on the organism), and the most highly induced genes are those in the sigV-rsiV operons [3,6,27]. In E. faecalis activation of σV induces expression of the sigV-rsiV operon as well as pgdA which encodes a peptidoglycan deacetylase [7,27]. In B. subtilis σV activation leads to a large increase in expression of oatA (O-acetyltransferase) and yrhK (unknown function) which are part of the sigV-rsiV operon [6,32]. OatA increases lysozyme resistance likely by adding an acetyl group to the O6 position of NAM [33,34]. C. difficile does not encode homologs of OatA however like B. subtilis the C. difficile sigV (csfV) operon is the mostly highly induced and encodes genes which modify peptidoglycan. These include pdaV (peptidoglycan deacetylase), prsA2 (peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase), rsiV (anti-σ factor) and lbpA (lysozyme-binding protein). LbpA is a homolog of RsiV that lacks the σV binding domain. LbpA can directly bind to and inhibit lysozyme activity much like RsiV [4,28]. In response to lysozyme these genes are induced >10-fold in wild type C. difficile. In a csfV mutant induction lysozyme fails to induce expression of these genes and the basal level of expression of these genes decreases ~10-fold. There are a few additional genes outside the csfV operon which are induced by σV including two genes of unknown function cd0738 and cd0739, as well as an operon cd1606–1611, which encodes a predicted GntR-like regulator (CD1606) and a ABC transporter system (CD1607–1611) [3]. In addition, Woods et al found that expression of the dlt operon was induced by lysozyme in σV-dependent manner [10]. Of these genes only pdaV, rsiV, lbpA and dlt have been implicated in lysozyme resistance [3,4,10,11]. Consistent with activation of σV being controlled by lysozyme, the σV regulons from multiple organisms show that the major σV-regulated genes encode either deacetylases of NAG or O-acetylases of NAM which can increase lysozyme resistance.

Role of Noise in σV activation

Recent work in B. subtilis shows that activation of σV at the single-cell level is heterogenous. This heterogeneity is more pronounced under in response to low levels of lysozyme and at higher levels activation is more uniform [35]. Interestingly in B. subtilis it was found that cells with higher basal levels of σV resulted in faster and more consistent σV activation [35]. In C. difficile the basal level of expression of csfV operon is higher than in B. subtilis [4,36]. Because of the autoregulatory nature of ECF σ factors like σV, this increased level of basal expression may lead to reduced noise. This is consistent with observations showing generally uniform responses at the single cell level in C. difficile [36]. It is unclear why basal levels of expression are higher in C. difficile but could be due to changes near the signal peptidase (site-1) cleavage site [24].

Unanswered questions

In addition to not understanding how lysozyme displaces the amphipathic helices to allow for signal peptidase to cleave RsiV and activate σV, it is also not known how the σV system is turned off in the absence of lysozyme. There are two possibilities, neither of which have been addressed yet. The first is that RsiV is produced at higher levels compared to σV and newly synthesized RsiV binds to and inhibits free σV. Another possibility is that free σV is inherently unstable and thus is turned over rapidly by cytosolic proteases. In this case newly synthesized RsiV binds to newly synthesized σV inhibiting its activity and the activated σV is destroyed over time by cytosolic proteases.

The role of the other ECF σ factors in C. difficile is not known. ECF σ factors have been implicated in resistance to many antimicrobials [37–39]. Most C. difficile strains encode three ECF σ factors although some strains carry four ECF σ factors [18]. Of these two ECF σ factors are conserved amongst nearly all sequenced C. difficile isolates csfT and sigV (csfV) [13]. To date no role for the other ECF σ factors has been described. Understanding the role of these other C. difficile ECF σ factors will provide insight into the stresses encountered by C. difficile during its life cycle and may provide targets for future therapeutic interventions.

Highlights:

The anti-sigma factor RsiV is a receptor for lysozyme

Binding of Lysozyme to RsiV triggers degradation of RsiV and activation of σV

Activation of σV increases lysozyme resistance

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Declarations of Competing Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Callewaert L, Michiels CW: Lysozymes in the animal kingdom. Journal of Biosciences 2010, 35:127–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters CWB, Kruse U, Pollwein R, Grzeschik K-H, Sippel AE: The human lysozyme gene. European Journal of Biochemistry 1989, 182:507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho TD, Williams KB, Chen Y, Helm RF, Popham DL, Ellermeier CD: Clostridium difficile extracytoplasmic function σ factor σV regulates lysozyme resistance and is necessary for pathogenesis in the hamster model of infection. Infection and immunity 2014, 82:2345–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaus GM, Snyder LF, Müh U, Flores MJ, Popham DL, Ellermeier CD: Lysozyme resistance in Clostridioides difficile is dependent on two peptidoglycan deacetylases. Journal of Bacteriology 2020, 202:e00421–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho TD, Hastie JL, Intile PJ, Ellermeier CD: The Bacillus subtilis Extracytoplasmic Function σ Factor σV Is Induced by Lysozyme and Provides Resistance to Lysozyme. Journal of bacteriology 2011, 193:6215–6222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guariglia-Oropeza V, Helmann JD: Bacillus subtilis σ(V) confers lysozyme resistance by activation of two cell wall modification pathways, peptidoglycan O-acetylation and D-alanylation of teichoic acids. Journal of bacteriology 2011, 193:6223–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hébert L, Courtin P, Torelli R, Sanguinetti M, Chapot-Chartier MP, Auffray Y, Benachour A: Enterococcus faecalis constitutes an unusual bacterial model in lysozyme resistance. Infection and Immunity 2007, 75:5390–5398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Jeune A, Torelli R, Sanguinetti M, Giard J-CC, Hartke A, Auffray Y, Benachour A: The extracytoplasmic function sigma factor SigV plays a key role in the original model of lysozyme resistance and virulence of Enterococcus faecalis. PloS one 2010, 5:e9658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirk JA, Gebhart D, Buckley AM, Lok S, Scholl D, Douce GR, Govoni GR, Fagan RP: New class of precision antimicrobials redefines role of Clostridium difficile S-layer in virulence and viability. Science Translational Medicine 2017, 9:eaah6813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woods EC, Nawrocki KL, Suárez JM, McBride SM: The Clostridium difficile Dlt Pathway Is Controlled by the Extracytoplasmic Function Sigma Factor σ V in Response to Lysozyme. Infection and Immunity 2016, 84:1902–1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coullon H, Rifflet A, Wheeler R, Janoir C, Boneca IG, Candela T: Peptidoglycan analysis reveals that synergistic deacetylase activity in vegetative Clostridium difficile impacts the host response. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295:16785–16796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vollmer W: Structural variation in the glycan strands of bacterial peptidoglycan. FEMS microbiology reviews 2008, 32:287–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho TD, Ellermeier CD: PrsW is required for colonization, resistance to antimicrobial peptides, and expression of extracytoplasmic function σ factors in Clostridium difficile. Infection and immunity 2011, 79:3229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sineva E, Savkina M, Ades SE: Themes and variations in gene regulation by extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2017, 36:128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmann JD: Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors and defense of the cell envelope. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2016, 30:122–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho TD, Ellermeier CD: Extra cytoplasmic function σ factor activation. Current opinion in microbiology 2012, 15:182–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmann JD: The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Advances in microbial physiology 2002, 46:47–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casas-Pastor D, Müller RR, Jaenicke S, Brinkrolf K, Becker A, Buttner MJ, Gross CA, Mascher T, Goesmann A, Fritz G: Expansion and re-classification of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factor family. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staroń A, Sofia HJ, Dietrich S, Ulrich LE, Liesegang H, Mascher T: The third pillar of bacterial signal transduction: classification of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor protein family. Molecular microbiology 2009, 74:557–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hastie JL, Williams KB, Ellermeier CD: The activity of σV, an extracytoplasmic function σ factor of Bacillus subtilis, is controlled by regulated proteolysis of the anti-σ factor RsiV. J Bacteriol 2013, 195:3135–3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varahan S, Iyer VS, Moore WT, Hancock LE: Eep Confers Lysozyme Resistance to Enterococcus faecalis via the Activation of the Extracytoplasmic Function Sigma Factor SigV. Journal of bacteriology 2013, 195:3125–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zellmeier S, Hofmann C, Thomas S, Wiegert T, Schumann W: Identification of sigma(V)-dependent genes of Bacillus subtilis. FEMS microbiology letters 2005, 253:221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshimura M, Asai K, Sadaie Y, Yoshikawa H: Interaction of Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors with the N-terminal regions of their potential anti-sigma factors. Microbiology 2004, 150:591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hastie JL, Williams KB, Sepúlveda C, Houtman JC, Forest KT, Ellermeier CD: Evidence of a Bacterial Receptor for Lysozyme: Binding of Lysozyme to the Anti-σ Factor RsiV Controls Activation of the ECF σ Factor σV. PLoS Genetics 2014,10:el004643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benachour A, Muller C, Dabrowski-Coton M, Le Breton Y, Giard J-C, Rincé A, Auffray Y, Hartke A: The Enterococcus faecalis sigV protein is an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor contributing to survival following heat, acid, and ethanol treatments. Journal of bacteriology 2005,187:1022–35.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro AN, Lewerke LT, Hastie JL, Ellermeier CD: Signal peptidase is necessary and sufficient for site-1 cleavage of RsiV in Bacillus subtilis in response to lysozyme. Journal of Bacteriology 2018, 200:JB.00663–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parthasarathy S, Wang X, Carr KR, Varahan S, Hancock EB, Hancock LE: SigV mediates lysozyme resistance in Enterococcus faecalis via RsiV and PgdA. Journal of Bacteriology [date unknown], 0:JB.00258–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hastie JL, Williams KB, Bohr LL, Houtman JC, Gakhar L, Ellermeier CD: The Anti-sigma Factor RsiV Is a Bacterial Receptor for Lysozyme: Co-crystal Structure Determination and Demonstration That Binding of Lysozyme to RsiV Is Required for σV Activation. PLOS Genetics 2016, 12:el006287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antelmann H, Tjalsma H, Voigt B, Ohlmeier S, Bron S, van Dijl JM, Hecker M: A proteomic view on genome-based signal peptide predictions. Genome research 2001, 11:1484–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paetzel M, Karla A, Strynadka NCJ, Dalbey RE: Signal peptidases. Chemical Reviews 2002, 102:4549–4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewerke LT, Kies PJ, Müh U, Ellermeier CD: Bacterial sensing: A putative amphipathic helix in RsiV is the switch for activating σV in response to lysozyme. PLoS genetics 2018, 14:el007527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asai K, Yamaguchi H, Kang C, Yoshida K, Fujita Y, Sadaie Y: DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma factors of extracytoplasmic function family. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2003, 220:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bera A, Herbert S, Jakob A, Vollmer W, Götz F: Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant? The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Molecular microbiology 2005, 55:778–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laaberki M-H, Pfeffer J, Clarke AJ Dworkin J: O-Acetylation of peptidoglycan is required for proper cell separation and S-layer anchoring in Bacillus anthracis. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011, 286:5278–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwall CP, Loman TE, Martins BMC, Cortijo S, Villava C, Kusmartsev V, Livesey T, Saez T, Locke JCW: Tunable phenotypic variability through an autoregulatory alternative sigma factor circuit. Mol Syst Biol 2021, 17:e9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ransom EM, Ellermeier CD, Weiss DS: Use of mCherry Red Fluorescent Protein for Studies of Protein Localization and Gene Expression in Clostridium difficile. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2015, 81:1652–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woods EC, McBride SM: Regulation of antimicrobial resistance by extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Microbes and Infection 2017, 19:238–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butcher BG, Helmann JD: Identification of Bacillus subtilis sigma-dependent genes that provide intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial compounds produced by Bacilli. Molecular microbiology 2006, 60:765–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellermeier CD, Losick R: Evidence for a novel protease governing regulated intramembrane proteolysis and resistance to antimicrobial peptides in Bacillus subtilis. Genes & development 2006, 20:1911–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]