Abstract

Germination by C. difficile spores is an essential step in pathogenesis. Spores are metabolically dormant forms of bacteria that resist severe conditions. Work over the last 10 years has elucidated that C. difficile spores germinate thorough a novel pathway. This review summarizes our understanding of C. difficile spore germination and the factors involved in germinant recognition, cortex degradation and DPA release.

Keywords: Clostridioides difficile, spore, Germination, pseudoprotease, DPA

Introduction

Germination by Clostridioides difficile spores is an essential step in the pathogenesis of this anaerobic, Gram-positive, spore-forming pathogen [1]. The small molecules that serve as signals to stimulate the germination process, germinants, are sensed by the subtilisin-like Csp proteins. In C. difficile, CspA and CspC are pseudoproteases whose activation upon germinant binding is hypothesized to relieve repression of the CspB protease. CspB then activates a cortex lytic enzyme, SleC, by cleaving the inhibitory pro-peptide. SleC then degrades the spore cortex layer (a protective layer of modified cell wall, degradation of which is critical for resumption of spore metabolic activity) which leads to core hydration and exit of spores from dormancy [2–4]. The disruption of the germination initiation pathway, either by triggering germination under sub-optimal conditions (i.e., in the presence of a protective gut microbiome), or by preventing germination altogether, could be a strategy to prevent the establishment of CDI. Indeed, this strategy is showing promise in animal models of CDI [5–8]. This review will summarize the current state of research into C. difficile spore germination, from the stage of spore dormancy up to the re-establishment of metabolic processes in a newly germinated cell, and how its disruption affects the treatment of CDI.

Spore structure

C. difficile spores have a complex structure that allows them to adhere to surfaces and resist adverse environmental conditions [9–11]. The outermost exosporium layer is composed of proteins and glycoproteins (i.e., BclA1, BclA2, BclA3, CdeA, CdeC, and CdeM). It is of variable thickness, and is believed to have a role in the spore interaction and attachment with the host intestinal epithelium [12–15]. The exosporium surrounds the coat layer, which is composed of layers of protein serving as a barrier for enzymes and damaging chemicals [16]. The coat is built upon the outer spore membrane, a membrane that is thought to be largely permeable during spore dormancy [17,18]. The outer spore membrane surrounds the cortex, a thick layer of modified peptidoglycan [19]. Under the cortex is the germ cell wall, a peptidoglycan layer destined to become the cell wall during outgrowth of a vegetative cell from a germinated spore, and the inner spore membrane, an immobile, low-permeability membrane that serves as a barrier to damaging chemicals [20,21]. The spore core contains DNA, RNA, proteins, and other components necessary for re-establishment of metabolic processes upon germination. The core has a low water content and increased levels of 1:1 chelate of Ca2+ with pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (CaDPA), which provide C. difficile (and spores derived from all other studied endospore forming bacteria) with remarkable heat resistance [22–27].

Germinants

Like all endospore-forming bacteria, C. difficile spores require the presence of small molecule compounds, germinants, to stimulate the cascade of events that trigger germination [28]. C. difficile spores activate germination in response to host-derived bile acids [29,30]. Bile acids are synthesized in the liver using cholesterol as a scaffold. The two primary bile acids, cholate and chenodeoxycholate, are further modified via conjugation with either taurine or glycine (e.g., taurocholate is generated from cholate and taurine) [31,32]. Cholate-derivatives are the most effective bile acid germinants, while chenodeoxycholate is a competitive inhibitor of cholic acid-mediated germination [29,30,33–37]. During GI transit, approximately 5% of the total amount of bile acids reach the large intestine where they are deconjugated and then metabolized by 7α-dehydroxylation by the native microbiota to generate secondary bile acids [31,32]. Upon antibiotic treatment, or during gut dysbiosis, the members of the colonic flora that mediate this metabolism are lost and this results in sufficient taurocholate concentrations (coupled with the increased pH) to germinate the spores [38–40]. It should be noted that certain conditions like obesity may significantly affect the severity of CDI by altering the ratio of primary to secondary bile acids present in the gut, with the increased levels of primary bile acids favoring the persistence of C. difficile and worsening the clinical outcomes [41]. Another way by which diet may influence CDI is by altering colonic pH levels. Recent work suggests that C. difficile germination is highly sensitive to even slight pH level variations, with the optimal pH for germination being greater than pH 6.2, and that particular diets, i.e., those high in fiber, may lower the colonic pH below the optimum, thereby reducing spore germination and outgrowth [38,42].

Though bile acids are necessary to stimulate C. difficile spore germination in vitro, they are not sufficient and a co-germinant signal is required [3,29,35,36,43,44]. Several amino acids can function as C. difficile spore co-germinants, but glycine is the most efficient amino acid co-germinant (calcium can also function as a co-germinant) [3,29,36,44]. Recent work by Leslie and colleagues [45] has shown that pre-colonization with a non-toxigenic C. difficile strain depletes glycine in the mouse gut and this prevents subsequent establishment of infection when spores derived from a toxigenic, C. difficile strain are used to infect. Their work suggests that despite the capability of other amino acids to stimulate spore germination in vitro, glycine is an important in vivo spore co-germinant.

Because spores, unlike vegetative cells, are insensitive to the toxic actions of antibiotics, one strategy to eradicate C. difficile in the gut is to initiate germination with the administration of germinants, while simultaneously administering antibiotics to kill the resulting vegetative cell [46]. This ‘germinate to eradicate’ strategy could be a potential avenue for the prevention of recurring CDI [47]. Alternatively, compounds that block the initiation of spore germination have potential in preventing C. difficile infection. By blocking the initiation of spore germination, all subsequent downstream events (e.g., outgrowth, vegetative growth, toxin production and sporulation) are prevented. This strategy has been shown to be effective in animal models of CDI [6–8].

Initiating C. difficile spore germination

CspC

In most endospore-forming bacteria, germinants are recognized at the inner spore membrane by Ger-type germinant receptors (e.g., GerAA – GerAB – GerAC) [48]. C. difficile does not encode the Ger-type germinant receptors and instead recognizes germinants using the CspA, CspB, and CspC proteins [1,37,43,49–53]. Prior to work done in C. difficile, the Csp proteins were best studied in Clostridium perfringens. In C. perfringens, CspA, CspB and CspC are subtilisin-like serine proteases and are hypothesized to remove the inhibitory propeptide from the cortex-degrading enzyme, pro-SleC [54–57]. Interestingly, in C. difficile, cspB and cspA have been translationally fused, and cspC is encoded downstream of the cspBA gene. Again, unlike what is found in C. perfringens, C. difficile CspA and CspC have lost their catalytic triad and are, thus, pseudoproteases [1,43,49–53].

In an ethylmethane sulfonate (EMS) screen to identify germination-null strains, single point mutations in C. difficile cspC were found to abrogate spore germination in response to bile acids and another (CspCG457R) altered germinant specificity by inducing germination in response to chenodeoxycholate, a primary bile acid that is normally an inhibitor of germination [1,30,33]. These results suggested that despite its loss of catalytic activity, the C. difficile CspC pseudoprotease still functioned to regulate germination in response to bile acids, potentially as a regulatory inhibitor of the CspB protease [1,37]. In recent work, Rohlfing and colleagues [50] crystallized the C. difficile CspC protein and used the data provided by this structure to probe regions of the protein and test how mutations in these regions altered C. difficile spore germination. Interestingly, they found that the CspCG457R mutation described previously was hypersensitive to both bile acid-mediated germination (i.e., taurocholate) and the co-germinant signal (i.e., glycine or arginine) [50]. Moreover, the authors found that the a strain harboring a mutation in a neighboring amino acid (CspCR456G) was also hypersensitive [50]. Despite this, not all cspC mutations altered sensitivities to both stimulatory molecules, and the authors found that CspCD429K led to increased bile acid sensitivity but not to sensitivity to the co-germinant signal [13]. Surprisingly, restoration of the catalytic site residues to CspC decreased protein stability and thus led to decreased germination [49]. These results suggest that CspC is a signaling point for C. difficile spore germination or that, potentially, CspC makes contact with the other germinant receptors and these mutations alter the binding to these proteins.

CspBA

Encoded upstream of C. difficile cspC is cspBA. CspBA is produced as a translational fusion between the cspB and cspA genes, and undergoes interdomain processing that involves the removal of a ~10 kDa long N-terminal domain separating CspBA into the CspB protease and the CspA pseudoprotease [52,53]. CspA undergoes further processing by the YabG protease [43,52]. Deletion or disruption of cspB or cspA prevents spore germination indicating that the CspA pseudoprotease, like the CspC pseudoprotease, is important for C. difficile spore germination [43,51]. The role of CspB in C. difficile spore germination is clear. It must cleave the inhibitory pro-peptide from the cortex degrading enzyme, pro-SleC, to trigger germination [51,53].

Mutations in C. difficile cspA also prevent spore germination. However, the mechanism by which C. difficile CspA functions during germination is complex. Disruption of the cspA portion of the cspBA gene prevents the incorporation of CspC into the developing spore suggesting that CspA and CspC may interact at some point during spore development, or that CspA is important for CspC stability in the dormant spore, or both [43,51,52]. Moreover, a C. difficile yabG mutant strain resulted in spores that no longer responded to a co-germinant and germinated in response to bile acids only [43]. In this strain, CspBA is no longer efficiently processed into the CspB and CspA forms (the interdomain processing of CspBA was weak in this strain) [43]. Moreover, small deletions in cspA, near the hypothesized YabG processing site within CspA [cspBAΔ537–571 or cspBAΔ581–584 (an SRQS deletion)], resulted in a strain whose spores could germinate in response to taurocholate only. However, unlike the yabG mutant, spores derived from a cspBAΔ537–571 strain could still respond to co-germinants [43]. This latter work led to the hypothesis that C. difficile CspA functions as the co-germinant receptor for C. difficile spore germination [43].

SleC

The C. difficile cortex lytic enzyme, SleC, is essential for spore germination [4]. SleC is deposited into the spore as an inactive zymogen (pro-SleC) [53,55]. Upon germinant and co-germinant recognition by CspA and CspC [1,37,43,49–52], CspB is activated (somehow) and CspB cleaves the inhibitory pro-peptide from SleC, thereby activating it [53]. SleC acts on the muramic-δ-lactam (MDL) residues that are uniquely found in the cortex layer and then degrades the cortex peptidoglycan layer. The degradation of the spore cortex permits the release of DPA from the spore core, in exchange for water [58,59]. Though SleC is the major spore cortex lytic enzyme, its ability to hydrolyze the cortex is dependent on the modification of the cortex peptidoglycan by GerS and CwlD, permitting SleC to recognize the substrate targeted for hydrolysis [60,61]. Interestingly, removal of the inhibitory pro-peptide is not required for in vitro degradation of muramic-δ-lactam-containing peptidoglycan – CspB activation of SleC may be required in C. difficile spores for proper lytic activity [62].

DPA release

In C. difficile and other spore-forming organisms, pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (dipicolinic acid [DPA]) is chelated in 1:1 ratio with Ca2+ (Ca-DPA)and packaged into the spore in large amounts at the expense of water. DPA is largely responsible for spore wet heat resistance, although it is not required for C. difficile spore formation and germination [20,21,25,27]. For the spore metabolic processes to resume, DPA must be released from the core in exchange for water. During dormancy, the cortex prevents the osmotic expansion of the spore core, thereby preventing the release of DPA [26,59,63]. In B. subtilis the proteins encoded by the spoVA operon (SpoVAA-AB-AC-AD-AEa-AEb-AF) play a role in DPA packaging and release. C. difficile encodes three orthologues of the spoVA operon, SpoVAC, SpoVAD, and SpoVAE. In B. subtilis, SpoVAD binds to DPA and is likely important in the packaging of DPA into the developing spore, a spoVAEa mutation causes only a slight germination defect, and the role of spoVAEb is unclear [64,65]. The mechanosensing protein, SpoVAC, is embedded in the inner spore membrane and, presumably, serves as the channel through which DPA is packaged into the spore core during sporulation and released during germination [26,66]. Recent work has shown that C. difficile SpoVAD and SpoVAE interact at inner spore membrane and, along with SpoVAC, hypothesized to form a complex required for packaging of DPA, which is perhaps applicable to other spore-forming organisms utilizing spoVA operon [67]. There is evidence that the DPA packaging into the spore core may be under regulation of other genes besides those in spoVA operon in C. difficile. Spores from strains lacking CD3298, an AAA+ ATPase, contain <1% of DPA found in spores of wild-type strains, similar to SpoVAC/SpoVAD/SpoVAE mutants, potentially indicating a role of CD3298 in DPA transport into the forespore during sporulation [44].Upon activation of SleC, degradation of the spore cortex results in the loss of ‘constraint’ on the inner spore membrane resulting in the activation of the mechanosensing SpoVAC protein and release of DPA from the core, in exchange for water (an ‘outside – in germination pathway) [26,59]. The rehydrated core then begins metabolic activity, and the spore eventually develops into a vegetative cell. This order of events is inverted from what is observed during B. subtilis spore germination. In B. subtilis, germinant recognition by the Ger-type germinant receptor leads to release of DPA and the released DPA can activate degradation of the cortex layer (an ‘inside – out’ germination pathway) because DPA directly activates the CwIJ cortex lytic enzyme [26,48,59,68].

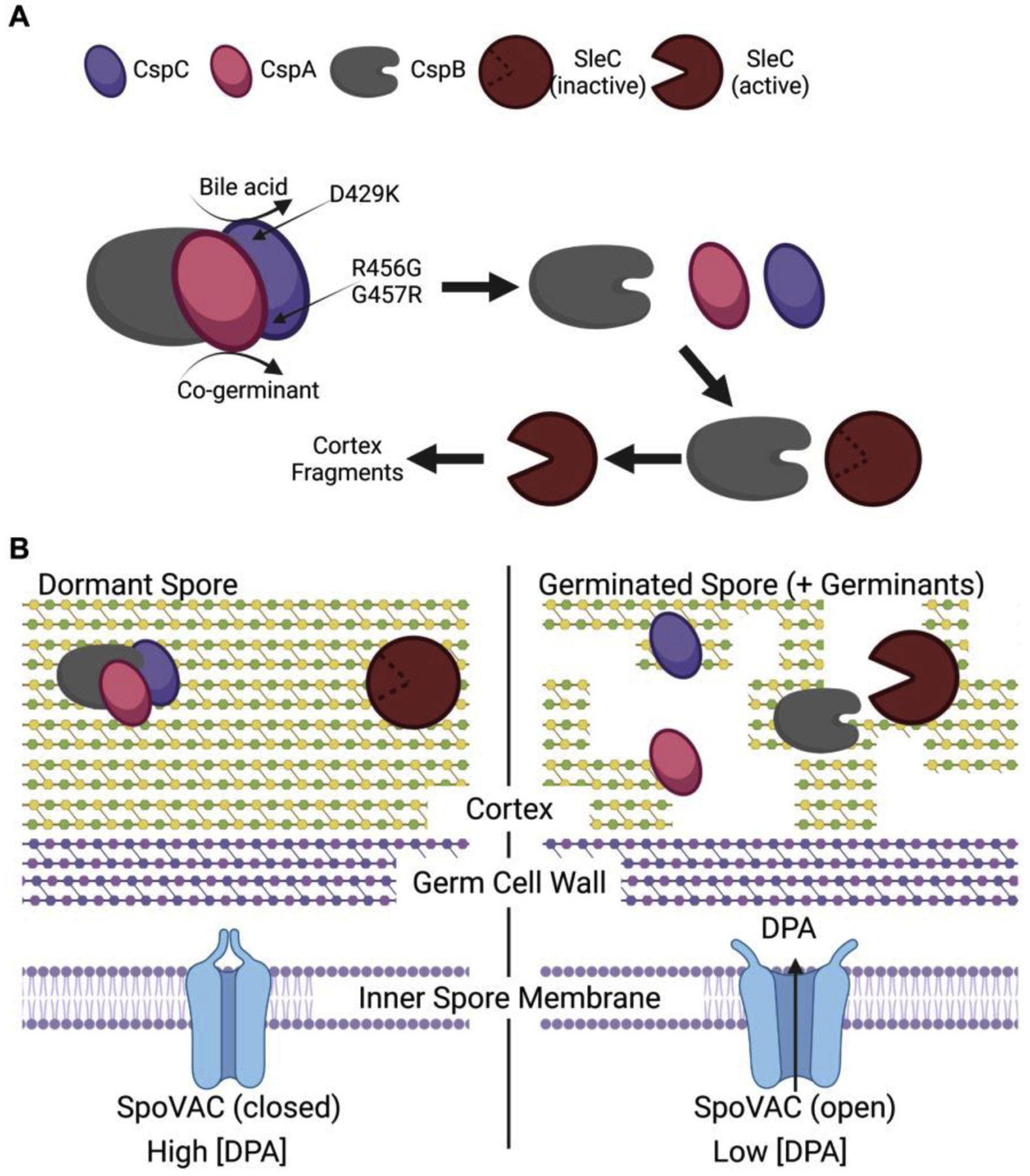

Hypothesized model for C. difficile spore germination

In a working / potential model for C. difficile spore germination, the CspB protease is held in an inactive state by the CspA and CspC pseudoproteases (Figure 1A and 1B). In this complex, the interaction of the three proteins regulates spore germination in response to exogenous signals. Upon recognition of the bile acid by CspC and the co-germinant by CspA, these proteins disassociate from CspB (Figure 1A). The liberated CspB is free to process pro-SleC into its active form resulting in degradation of the spore cortex layer (Figure 1A and 1B). Based on the data provided by Rohlfing and colleagues [50], we hypothesize that CspCD429 is near the CspB and CspA binding interfaces and the D429K allele is hypersensitive to the TA germinant and calcium co-germinant due to instability of these surfaces (Figure 1A) [50]. The CspCR456 and CspCG457 amino acids may be located near the binding interface with CspA and with CspB because the CspCR456G and CspCG457R alleles are hypersensitive to both bile acid germinants and amino acid co-germinants [1,50]. We hypothesize that this leads to destabilization of the CspA/CspC and the CspC/CspB binding interface and thus weakening the overall complex. In a yabG mutant strain, CspA is not processed from CspB and thus is not positioned in the complex to regulate spore germination in response to co-germinants [43].

Figure 1. Working model for C. difficile spore germination.

(A) The CspC and CspA pseudoproteases bind to and inhibit the CspB protease from gaining access to the cortex-degrading SleC zymogen. Upon germinant sensing, CspC and CspA disassociate from CspB resulting in CspB cleaving the inhibitory pro-peptide from pro-SleC. Activated SleC degrades the spore cortex. (B) In a dormant spore, the mechanosensing membrane protein, SpoVAC, is in a closed state and prevents the release of the large amounts of DPA from the spore core. Upon degradation of the spore cortex layer, a change in osmolarity is perceived at the inner spore membrane and this results in SpoVAC opening to release DPA. Created with Biorender.com.

In a dormant spore, the SpoVAC mechanosensing protein is in a closed state and prevents the release of the large depot of CaDPA from the spore core (Figure 1B). Upon activation of germination, SleC degrades the spore cortex layer. This results in an osmotic shift that is perceived at the inner spore membrane and SpoVAC opens to release DPA from the core (Figure 1B).

Concluding remarks

The last 10 years have marked significant advances in our understanding of how C. difficile spores germinate. The identification of the proteins required to initiate the spore germination process and how these proteins / processes differ compared to what is observed in B. subtilis has led to a proposed novel “outside – in” germination pathway. However, despite these advances, much remains to be understood. It is unclear if CspB, CspA and CspC interact in dormant spores and how the identified alleles contribute to germinant recognition is biochemically unknown. Moreover, it is interesting that mutations in cspA can block the import or stability of CspC in the spore. Is CspA merely required for CspC stability or is CspA influencing the packaging of CspC into the spore? A biochemical understanding of spore germination is likely to shed light on many of these questions.

Highlights.

C. difficile spore germination is regulated by two pseudoproteases.

The CspC germinant receptor and pseudoprotease regulates bile acid and co-germinant recognition.

C. difficile spore germination proceeds through an “outside – in” pathway.

Inhibiting germination has shown promise in preventing disease in animal models.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank other members of the Sorg laboratory for their helpful comments during the preparation of this manuscript. Due to space limitations, we could not address all aspects of C. difficile spore germination and thus apologize to those authors whose work was not included in this review. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01AI116895). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Francis MB, Allen CA, Shrestha R, Sorg JA: Bile acid recognition by the Clostridium difficile germinant receptor, CspC, is important for establishing infection. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9:e1003356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● In this work, Francis and colleagues conducted an EMS screen to identify strains that failed to respond to taurocholate as a germinant. This led to the identification of point mutations in the cspC gene. Site-directed mutatgenesis of the cspC gene led to a strain whose spores could not respond to taurocholate as a spore germinant. A separate EMS screen identified a mutation in cspC (G457R) that resulted in a strain that germinated in response to chenodeoxycholate (an inhibitor of spore germinaton). Finally, the authors show that germination by C. difficile spores in required for robust infection in an hamster model of CDI

- 2.Lawler AJ, Lambert PA, Worthington T: A revised understanding of Clostridioides difficile spore germination. Trends in Microbiology 2020, 28:744–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shrestha R, Sorg JA: Hierarchical recognition of amino acid co-germinants during Clostridioides difficile spore germination. Anaerobe 2018, 49:41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns DA, Heap JT, Minton NP: SleC is essential for germination of Clostridium difficile spores in nutrient-rich medium supplemented with the bile salt taurocholate. J. Bacteriol 2010, 192:657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akoachere M, Squires RC, Nour AM, Angelov L, Brojatsch J, Abel-Santos E: Indentification of an in vivo inhibitor of Bacillus anthracis spore germination. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282:12112–12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howerton A, Patra M, Abel-Santos E: A new strategy for the prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. J Infect Dis 2013, 207:1498–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howerton A, Seymour CO, Murugapiran SK, Liao Z, Phan JR, Estrada A, Wagner AJ, Mefferd CC, Hedlund BP, Abel-Santos E: Effect of the synthetic bile salt analog CamSA on the hamster model of Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● In this article, Howerton and colleagues build upon their prior work with CamSA, a potent inhibitor of C. difficile spore germination. Prior work has shown that CamSA is a competitive inhibitor of cholate-mediated spore germination. Here, the authors find the treatment of hamsters with 300 mg / kg CamSA significantly delayed CDI compared to controls. This is no easy feat in the hamster model of CDI as hamsters are exquisitely sensitive to C. difficile infection and diease. Their work shows that preventing in vivo spore germination is a viable strategy to prevent the onset of CDI.

- 8.Yip C, Okada NC, Howerton A, Amei A, Abel-Santos E: Pharmacokinetics of CamSA, a potential prophylactic compound against Clostridioides difficile infections. Biochem Pharmacol 2021, 183:114314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards AN, Karim ST, Pascual RA, Jowhar LM, Anderson SE, McBride SM: Chemical and stress resistances of Clostridium difficile spores and vegetative cells. Front Microbiol 2016, 7:1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi LT, Welsch A, Hawkins J, Baillie L: The effect of hospital biocide sodium dichloroisocyanurate on the viability and properties of Clostridium difficile spores. Lett Appl Microbiol 2017, 65:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer C, Hutt LP, Burky R, Joshi LT: Biocide resistance and transmission of Clostridium difficile spores spiked onto clinical surfaces from an American health care facility. Appl Environ Microbiol 2019, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero-Rodríguez A, Troncoso-Cotal S, Guerrero-Araya E, Paredes-Sabja D, Ellermeier CD: The Clostridioides difficile cysteine-rich exosporium morphogenetic protein, CdeC, exhibits self-assembly properties that lead to organized inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli. mSphere 2020, 5:e01065–01020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pizarro-Guajardo M, Calderón-Romero P, Romero-Rodríguez A, Paredes-Sabja D: Characterization of exosporium layer variability of Clostridioides difficile spores in the epidemically relevant strain R20291. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Gonzalez F, Milano M, Olguin-Araneda V, Pizarro-Cerda J, Castro-Cordova P, Tzeng SC, Maier CS, Sarker MR, Paredes-Sabja D: Protein composition of the outermost exosporium-like layer of Clostridium difficile 630 spores. J Proteomics 2015, 123:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro-Córdova P, Mora-Uribe P, Reyes-Ramírez R, Cofré-Araneda G, Orozco-Aguilar J, Brito-Silva C, Mendoza-León MJ, Kuehne SA, Minton NP, Pizarro-Guajardo M, et al. : Clostridioides difficile spore-entry into intestinal epithelial cells contributes to recurrence of the disease. bioRxiv 2020:2020.2009.2011.291104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Driks A, Eichenberger P: The spore coat. In The Bacterial Spore: from Molecules to Systems. Edited by: American Society of Microbiology; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freer JH, Levinson HS: Fine structure of Bacillus megaterium during microcycle sporogenesis. J Bacteriol 1967, 94:441–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crafts-Lighty A, Ellar DJ: The structure and function of the spore outer membrane in dormant and germinating spores of Bacillus megaterium. J Appl Bacteriol 1980, 48:135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popham DL, Helin J, Costello CE, Setlow P: Analysis of the peptidoglycan structure of Bacillus subtilis endospores. J Bacteriol 1996, 178:6451–6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowan AE, Koppel DE, Setlow B, Setlow P: A soluble protein is immobile in dormant spores of Bacillus subtilis but is mobile in germinated spores: implications for spore dormancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100:4209–4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunde EP, Setlow P, Hederstedt L, Halle B: The physical state of water in bacterial spores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106:19334–19339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paredes-Sabja D, Shen A, Sorg JA: Clostridium difficile spore biology: sporulation, germination, and spore structural proteins. Trends Microbiol 2014, 22:406–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamroskovic J, Chromikova Z, List C, Bartova B, Barak I, Bernier-Latmani R: Variability in DPA and calcium content in the spores of Clostridium species. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berendsen EM, Boekhorst J, Kuipers OP, Wells-Bennik MH: A mobile genetic element profoundly increases heat resistance of bacterial spores. ISME J 2016, 10:2633–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donnelly ML, Fimlaid KA, Shen A: Characterization of Clostridium difficile spores lacking either SpoVAC or dipicolinic acid synthetase. J Bacteriol 2016, 198:1694–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis MB, Sorg JA: Dipicolinic acid release by germinating Clostridium difficile spores occurs through a mechanosensing mechanism. mSphere 2016, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Setlow P: Spore resistance properties. Microbiol Spectr 2014, 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen A: Clostridioides difficile spore formation and germination: New insights and opportunities for intervention. Annu Rev Microbiol 2020, 74:545–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL: Bile salts and glycine as cogerminants for Clostridium difficile spores. J Bacteriol 2008, 190:2505–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL: Chenodeoxycholate is an inhibitor of Clostridium difficile spore germination. J Bacteriol 2009, 191:1115–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB: Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res 2006, 47:241–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB, Bajaj JS: Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2014, 30:332–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorg JA, Sonenshein AL: Inhibiting the initiation of Clostridium difficile spore germination using analogs of chenodeoxycholic acid, a bile acid. J Bacteriol 2010, 192:4983–4990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Francis MB, Allen CA, Sorg JA: Muricholic acids inhibit Clostridium difficile spore germination and growth. PLoS One 2013, 8:e73653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramirez N, Liggins M, Abel-Santos E: Kinetic evidence for the presence of putative germination receptors in Clostridium difficile spores. J Bacteriol 2010, 192:4215–4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howerton A, Ramirez N, Abel-Santos E: Mapping interactions between germinants and Clostridium difficile spores. J Bacteriol 2011, 193:274–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharjee D, Francis MB, Ding X, McAllister KN, Shrestha R, Sorg JA: Reexamining the germination phenotypes of several Clostridium difficile strains suggests another role for the CspC germinant receptor. Journal of Bacteriology 2016, 198:777–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kochan TJ, Shoshiev MS, Hastie JL, Somers MJ, Plotnick YM, Gutierrez-Munoz DF, Foss ED, Schubert AM, Smith AD, Zimmerman SK, et al. : Germinant synergy facilitates Clostridium difficile spore germination under physiological conditions. mSphere 2018, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theriot CM, Koenigsknecht MJ, Carlson PE Jr., Hatton GE, Nelson AM, Li B, Huffnagle GB, J ZL, Young VB: Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Commun 2014, 5:3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buffie CG, Bucci V, Stein RR, McKenney PT, Ling L, Gobourne A, No D, Liu H, Kinnebrew M, Viale A, et al. : Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature 2015, 517:205–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jose S, Mukherjee A, Horrigan O, Setchell KDR, Zhang W, Moreno-Fernandez ME, Andersen H, Sharma D, Haslam DB, Divanovic S, et al. : Obeticholic acid ameliorates severity of Clostridioides difficile infection in high fat diet-induced obese mice. Mucosal Immunology 2021, 14:500–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuille S, Mackay WG, Morrison DJ, Tedford MC: Drivers of Clostridioides difficile hypervirulent ribotype 027 spore germination, vegetative cell growth and toxin production in vitro. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2020, 26:941.e941–941.e947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrestha R, Cochran AM, Sorg JA: The requirement for co-germinants during Clostridium difficile spore germination is influenced by mutations in yabG and cspA. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15:e1007681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● This study conducted an EMS screen to identify C. difficile strains with altered co-germinant requirements. The authors found mutation in the gene coding for the YabG protease. Site-directed yabG mutants resulted in a strain whose spores could not resonse to co-germinants and germinated in response to taurocholate only. Building upon this the authors found that small mutations in the cspA gene (a 4 codon deletion) resulted in a strain whose spores did not require co-germinants to germinate. The authors concluded that CspA is the co-germinant receptor for C. difficile spores.

- 44.Kochan TJ, Somers MJ, Kaiser AM, Shoshiev MS, Hagan AK, Hastie JL, Giordano NP, Smith AD, Schubert AM, Carlson PE Jr., et al. : Intestinal calcium and bile salts facilitate germination of Clostridium difficile spores. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13:e1006443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Kochan and colleagues found that, in addition to the known amino acid co-germinants, exogenous calcium could function as a co-germinant with taurocholate to stimulate C. difficile spore germination. The authors built upon this by showing that calcium chelation prevented C. difficile spore germination and that calcium is an important in vivo factor for C. difficile spore germination

- 45.Leslie JL, Jenior ML, Vendrov KC, Standke AK, Barron MR, O’Brien TJ, Unverdorben L, Thaprawat P, Bergin IL, Schloss PD, et al. : Protection from lethal Clostridioides difficile infection via intraspecies competition for cogerminant. mBio 2021, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● Leslie and colleages found that pre-colonization of CDI-susceptible mice with a low virulence C. difficile strain prevented colonization of a super-invading, highly toxigenic C. difficile strain. The protection afforded by the strain that colonized the mice first was independent of the microbiota or the host’s immune response. The authors went on to show that the protection was due to the consumption of the co-germinant glycine therebye preventing spore germination by the invading strain. This highlights the in vivo importance of glycine for C. difficile spore germination.

- 46.Kohler LJ, Quirk AV, Welkos SL, Cote CK: Incorporating germination-induction into decontamination strategies for bacterial spores. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2018, 124:2–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Budi N, Godfrey JJ, Safdar N, Shukla SK, Rose WE: Omadacycline compared to vancomycin when combined with germinants to disrupt the life cycle of Clostridioides difficile. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2021, 65:e01431–01420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Setlow P, Wang S, Li YQ: Germination of spores of the orders Bacillales and Clostridiales. Annu Rev Microbiol 2017, 71:459–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donnelly ML, Forster ER, Rohlfing AE, Shen A: Differential effects of ‘resurrecting’ Csp pseudoproteases during Clostridioides difficile spore germination. Biochemical Journal 2020, 477:1459–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● In this article, Donnelly et al. restored the catalytic triad to the C. difficile CspA and CspC pseudoproteases. Surprisingly, this led to the destablization of the CspC protein which resulted in impaired spore germination. In contrast, restoring the catalytic triad to CspA did not restore protease activity to the protein. Their work indicates that a catalytic triad is not solely responsible for catalytic activity. Interestingly, CspA can be found in other endospore-forming bacteria and these CspA proteins retain their catalytic triad but it may be that these proteins are also pseudoproteases.

- 50.Rohlfing AE, Eckenroth BE, Forster ER, Kevorkian Y, Donnelly ML, Benito de la Puebla H, Doublié S, Shen A: The CspC pseudoprotease regulates germination of Clostridioides difficile spores in response to multiple environmental signals. PLOS Genetics 2019, 15:e1008224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ● In this article, Rohlfing and colleagues determined the X-ray structure of the bile acid germinant receptor, CspC. Using the data from this structure, the authors probed how mutation in certain domains or how residues identified previously influence germination. Their work finds that mutations could be identified that alter the response of spores to both bile acid germinant and amino acid co-germinant or to bile acid germinant alone. This work led to the hypothesis that CspC is hub for germinant sensing and plays a role not only as a bile acid receptor but also is involved in co-germinant sensing.

- 51.Kevorkian Y, Shen A: Revisiting the role of Csp family proteins in regulating Clostridium difficile spore germination. J Bacteriol 2017, 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kevorkian Y, Shirley DJ, Shen A: Regulation of Clostridium difficile spore germination by the CspA pseudoprotease domain. Biochimie 2016, 122:243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams CM, Eckenroth BE, Putnam EE, Doublie S, Shen A: Structural and functional analysis of the CspB protease required for Clostridium spore germination. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9:e1003165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banawas S, Korza G, Paredes-Sabja D, Li Y, Hao B, Setlow P, Sarker MR: Location and stoichiometry of the protease CspB and the cortex-lytic enzyme SleC in Clostridium perfringens spores. Food Microbiol 2015, 50:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paredes-Sabja D, Setlow P, Sarker MR: The protease CspB is essential for initiation of cortex hydrolysis and dipicolinic acid (DPA) release during germination of spores of Clostridium perfringens type A food poisoning isolates. Microbiology 2009, 155:3464–3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paredes-Sabja D, Setlow P, Sarker MR: SleC is essential for cortex peptidoglycan hydrolysis during germination of spores of the pathogenic bacterium Clostridium perfringens. J Bacteriol 2009, 191:2711–2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shimamoto S, Moriyama R, Sugimoto K, Miyata S, Makino S: Partial characterization of an enzyme fraction with protease activity which converts the spore peptidoglycan hydrolase (SleC) precursor to an active enzyme during germination of Clostridium perfringens S40 spores and analysis of a gene cluster involved in the activity. J Bacteriol 2001, 183:3742–3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Francis MB, Sorg JA: Detecting cortex fragments during bacterial spore germination. J Vis Exp 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Francis MB, Allen CA, Sorg JA: Spore cortex hydrolysis precedes dipicolinic acid release during Clostridium difficile spore germination. J Bacteriol 2015, 197:2276–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diaz OR, Sayer CV, Popham DL, Shen A: Clostridium difficile lipoprotein GerS is required for cortex modification and thus spore germination. mSphere 2018, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fimlaid KA, Jensen O, Donnelly ML, Francis MB, Sorg JA, Shen A: Identification of a novel lipoprotein regulator of Clostridium difficile spore germination. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11:e1005239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gutelius D, Hokeness K, Logan SM, Reid CW: Functional analysis of SleC from Clostridium difficile: an essential lytic transglycosylase involved in spore germination. Microbiology 2014, 160:209–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhattacharjee D, Sorg JA: Conservation of the “outside-in” germination pathway in Paraclostridium bifermentans. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Y, Davis A, Korza G, Zhang P, Li YQ, Setlow B, Setlow P, Hao B: Role of a SpoVA protein in dipicolinic acid uptake into developing spores of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 2012, 194:1875–1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Perez-Valdespino A, Li Y, Setlow B, Ghosh S, Pan D, Korza G, Feeherry FE, Doona CJ, Li YQ, Hao B, et al. : Function of the SpoVAEa and SpoVAF proteins of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol 2014, 196:2077–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Velasquez J, Schuurman-Wolters G, Birkner JP, Abee T, Poolman B: Bacillus subtilis spore protein SpoVAC functions as a mechanosensitive channel. Mol Microbiol 2014, 92:813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baloh M, Sorg JA: Clostridioides difficile SpoVAD and SpoVAE interact and are required for dipicolinic acid uptake into spores. J Bacteriol 2021, 203:e0039421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paidhungat M, Ragkousi K, Setlow P: Genetic requirements for induction of germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis by Ca(2+)-dipicolinate. J Bacteriol 2001, 183:4886–4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]