Abstract

Individuals with schizophrenia engage in more sedentary behavior than healthy controls, which is thought to contribute to multiple health adversities. Age, medication side effects and environment are critical determinants of physical activity in psychosis. While motor abnormalities are frequently observed in psychosis, their association with low physical activity has received little interest. Here, we aimed to explore the association of actigraphy as an objective measure of physical activity with clinician assessed hypokinetic movement disorders such as parkinsonism and catatonia. Furthermore, we studied whether patients with current catatonia would differ on motor rating scales and actigraphy from patients without catatonia. In 52 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, we cross-sectionally assessed physical activity using wrist actigraphy and ratings of catatonia, parkinsonism, and negative syndrome. The sample was enriched with subjects with severe psychomotor slowing. Lower activity levels correlated with increased age and severity of catatonia and parkinsonism. The 22 patients with catatonia had lower activity as well as higher scores on parkinsonism, involuntary movements, and negative symptoms compared to the 30 patients without catatonia. Collectively, these results suggest that various hypokinetic motor abnormalities are linked to lower physical activity. Therefore, future research should determine the direction of the associations between hypokinetic motor abnormalities and physical activity using longitudinal assessments and interventional trials.

Keywords: Actigraphy, Schizophrenia, Catatonia, Cardiometabolic health

1. Introduction

Cardio metabolic health is a major issue in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders are associated with lower life expectancy of 15–20 years, which may be partially accounted for the impact of these disorders on health behaviors (Hjorthoj et al., 2017; Kurdyak et al., 2021; Nielsen et al., 2021). Meta-analyses indicate that subjects with schizophrenia have lower physical activity (PA), particularly of moderate to vigorous activity than healthy controls (moderate activity – 10 min per day, vigorous activity – 3 min per day) (Stubbs et al., 2016; Vancampfort et al., 2017). Some of the studies on PA in schizophrenia suggested a negative impact of side effects of antipsychotic medication (Vancampfort et al., 2017; Vancampfort et al., 2012), e.g. fatigue or metabolic syndrome. Although, low PA and low fitness have also been observed in unmedicated subjects at risk for psychosis (Damme et al., 2021; Mittal et al., 2013). In addition, motor side effects may also contribute to lower PA in subjects with schizophrenia.

A variety of spontaneous and drug induced motor abnormalities are frequently observed in schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Walther and Mittal, 2017; Walther et al., 2020). Both hyperkinetic movement disorders, such as abnormal involuntary movements, akathisia or dystonia, and hypokinetic movement disorders, e.g. Parkinsonism (with brady-kinesia), or catatonia may occur at all stages of the disorder ranging from those at risk to those with chronic courses (Peralta and Cuesta, 2010, 2017; Walther and Mittal, 2017; Walther and Strik, 2012; Walther et al., 2020). Finally, psychomotor slowing remains a special symptom, as it may occur either independently or concurrently with classic hypokinetic motor abnormalities or the negative syndrome domain of apathy (Mittal et al., 2021a).

Assessing motor abnormalities, particularly the hypokinetic forms, remains challenging in clinical practice. In fact, there is considerable overlap between hypokinetic phenomena, such as catatonia, parkinsonism, the negative syndrome and psychomotor slowing in psychosis (Mittal et al., 2021a; Osborne et al., 2020; Rogers, 1985; Walther and Mittal, 2017). Depending on the perspective, the same hypokinetic behavior will receive different names. Essentially, these overlaps will also confound expert rating scales, that are typically designed to focus on a single type of motor abnormality. Therefore, the use of instrumental assessments has been advocated in schizophrenia (Pieters et al., 2021; van Harten et al., 2017; Walther et al., 2020). Instrumental measures, such as actigraphy, can assess movements across multiple real world settings continuously and allow for generating dimensional objective parameters. Furthermore, instrumental measures are not prone to observer biases and require little training.

One study indicated that lower PA was predicted by parkinsonism and age in patients with schizophrenia (Pieters et al., 2021). However, the association of PA with other hypokinetic movement disorders such as catatonia remains unclear. In contrast, a number of previous studies using wrist-actigraphy consistently reported reduced activity levels to correlate with increased severity of the negative syndrome (Docx et al., 2013; Kluge et al., 2018; Servaas et al., 2019; Walther et al., 2014; Wichniak et al., 2011). Thus, we may assume that lower PA is indeed linked to negative symptom severity. Still, given the conceptual overlap of the expert rating scales, it is currently unclear if objectively assessed PA may be associated with the presence of hypokinetic movement abnormalities, such as catatonia or parkinsonism. Finally, although patients with catatonic schizophrenia have been found to exhibit lower activity levels compared to patients with paranoid schizophrenia in DSM-IV (Walther et al., 2009), it will still be important to interrogate whether patients with and without catatonia differ in objective measures of motor activity as well as in common ratings of hypokinetic movement disorders.

In this study on hypokinetic movement disorders in psychosis, the first aim was to examine correlations between physical activity (PA) as measured by actigraphy with current severity of parkinsonism, catatonia, and negative symptoms. Here, we expected to find strong associations between expert ratings of motor abnormalities and actigraphic measures of PA. The next goal was to determine patients with and without current catatonia exhibited differences on PA and the severity of motor abnormalities. We hypothesized that patients with catatonia will have lower activity levels as well as higher scores on parkinsonism and negative symptoms compared to patients without catatonia.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

For this analysis, we combined data from two studies; baseline data of a randomized controlled trial (n = 21) (Walther et al., 2020) and a prior cross-sectional study on motor function and neuroimaging in schizophrenia (n = 31) (Walther et al., 2017). We included all available data sets with (1) actigraphy data and (2) patients with schizophrenia (n = 37), schizophreniform (n = 4) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 3). In total, we included33 men and 19 women (mean age 36.8 ± 12.3 years, mean duration of illness 11.6 ± 11.5 years). All but three patients were on antipsychotic medication at the time of assessment. Thirty-two patients were on monotherapy and 17 received multiple antipsychotics. Current antipsychotics administered included risperidone (n = 14), clozapine (n = 15), olanzapine (n = 11), quetiapine (n = 6), haloperidol (n = 5), aripiprazole (n = 4), amisulpride (n = 3), paliperidone (n = 3), clotiapine (n = 2), zuclopenthixol (n = 2), flupentixol (n = 1), and lurasidone (n = 1). Two of the patients (4%) received antiparkinsonian medication. All subjects were right-handed and diagnoses were established using DSM-5 criteria and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (Sheehan et al., 1998). Subjects in the interventional study were included if they had severe psychomotor slowing (52% of the subjects screened for the trial had severe psychomotor slowing), while the other study included patients irrespective of their current symptom presentation. Common exclusion criteria were neurological or medical conditions that impact motor behavior, e.g. stroke, lifetime diagnosis of substance dependence other than nicotine. All participants were in patients (n = 44) or outpatients (n = 8) at the University Hospital of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in Bern, Switzerland. The local ethics committee had approved both studies, participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion.

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Instrumental measure of PA

Both studies applied identical actigraphy assessments using wrist-worn actigraphs (Actiwatch, Cambridge Neurotechnology, Inc., Cambridge, UK) for 24 consecutive hours on the non-dominant arm. The device contains an accelerometer that converts movements in all directions into movement counts. Data were sampled in 2 s intervals. Participants provided information on recording pauses (due to showering or bathing) and sleep. Only the data collected during wakeful periods of the 24 h recording time were analyzed. The total sum of the movement counts were averaged to provide the activity level (AL) in counts/h as the instrumental measure of physical activity (PA) (Kluge et al., 2018; Walther et al., 2009; Walther et al., 2014). Thus, AL represents the total sum of movements per hour during the wake periods of the day across all types of activity, e.g. sitting, standing, or walking.

2.2.2. Rating scales

Assessments of psychopathology and motor behavior were conducted blind to the outcome of the actigraphy data. All clinical ratings were performed by psychiatry residents (IV, DA, LS, KS), who had been trained by the principal investigator (SW) to achieve κ > 0.80.

2.2.2.1. Motor abnormalities.

Hypokinetic motor abnormalities were assessed with the Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) (Bush et al., 1996) and the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) (Fahn et al., 1987), from which we rated the pure motor part (part III). In one study, we also assessed dyskinesia with the abnormal involuntary movement scale (AIMS) (Guy, 1976) and neurological soft signs with the Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES) (Buchanan and Heinrichs, 1989).

2.2.2.2. Symptom rating scales.

We measured broad symptom severity with the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987). Furthermore, negative syndrome severity was rated using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Andreasen, 1989).

2.3. Statistics

Shapiro-Wilk tests indicated that none of the variables followed a normal distribution. Therefore, all analyses were conducted with nonparametric tests (Spearman rank correlations and Mann-Whitney-U-test). First, we correlated the activity levels (AL) with PANSS scores. Second, we calculated the correlations between AL, age, CPZ, and the hypokinetic motor behavior scales (BFRCS, UPDRS-III) and SANS. These correlations were corrected for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate (FDR). Third, we tested whether patients with catatonia according to the BFCRS criteria (≥ 2 items on the screening instrument of BFCRS), would differ from those without catatonia (<2 items on the BFCRS screening instrument) on motor behavior rating scales and activity levels using Mann-Whitney-U-tests, and ANCOVAs controlling for age and CPZ. Finally, we correlated activity levels with the three BFCRS factors described by Wilson and colleagues in a sample of 339 patients: decreased, increased and abnormal psychomotor activity (Wilson et al., 2015).

3. Results

3.1. Correlation of PA with psychopathology

In this sample, the activity levels were on average 14′470 counts/h (SD = 8′136), which is in line with previous reports and much lower than in healthy controls, e.g. mean = 21′511, SD = 7′580, n = 46 in (Walther et al., 2017). Lower activity levels in patients correlated with higher PANSS negative scores (rS = − 0.32, p = .021), but not with PANSS positive (rS = 0.20, p = .15), general (rS = − 0.19, p = .18) or total scores (rS = − 0.20, p = .16). In the subgroup of patients with AIMS and NES scores (n = 31), we found no correlation with activity levels (all p > .39).

3.2. Correlation of PA with hypokinetic motor abnormalities

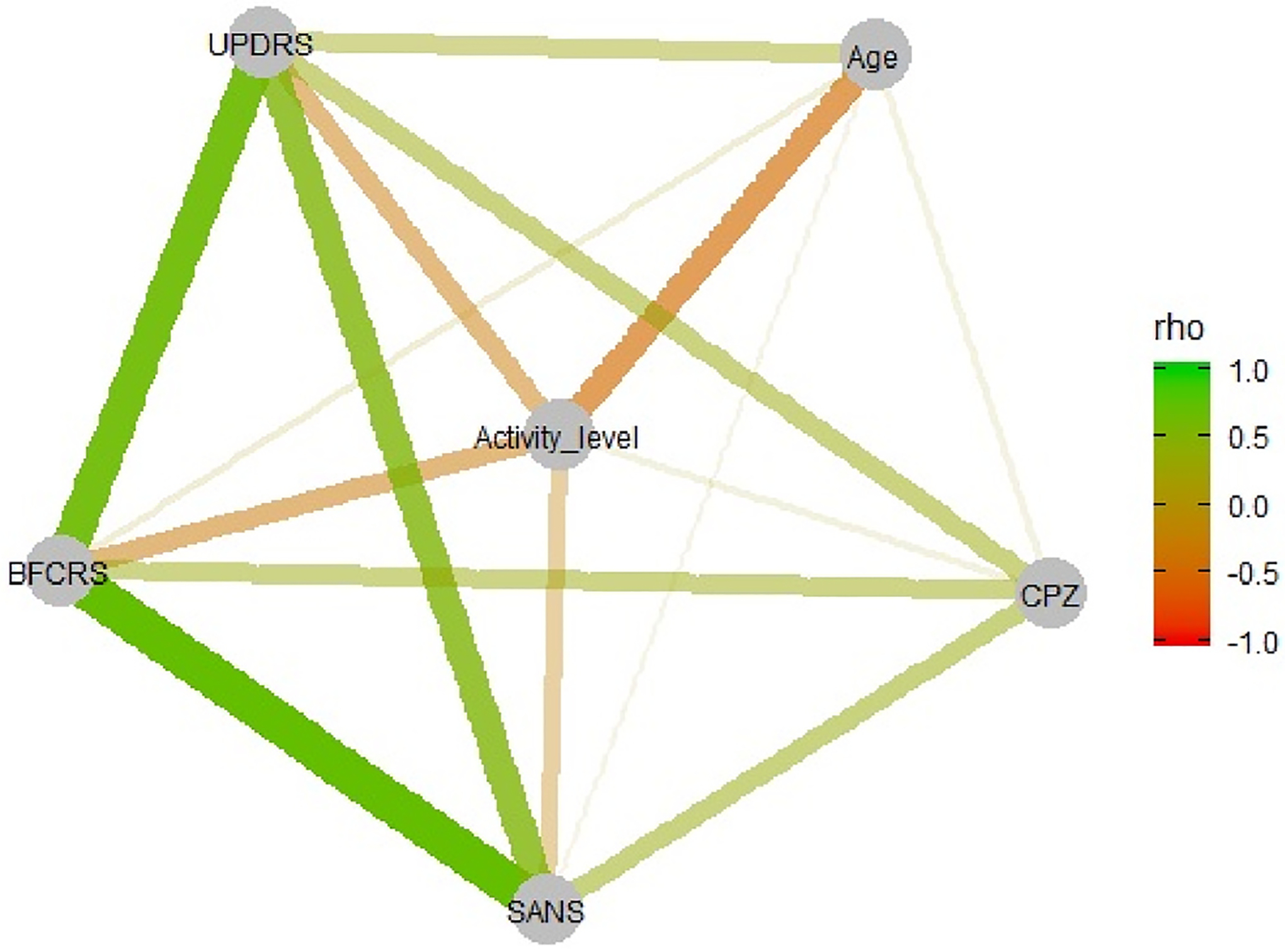

Lower PA was linked to higher age and higher scores on BFCRS, UPDRS, and SANS (see Table 1, Fig. 1). The three rating scales further correlated substantially with each other. Current dose of antipsychotics was unrelated to PA.

Table 1.

Correlation of physical activity and clinical parameters in 52 patients with SSD.

| Age | CPZ | BFCRS | UPDRS III | SANS total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity level | −.45 (.003) | .05 (n.s.) | −.34 (.037) | −.33 (.037) | −.23 (n.s.) |

| Age | – | −.04 (n.s.) | .07 (n.s.) | .28 (n.s.) | −.03 (n.s.) |

| CPZ | – | .31 (.039) | .33 (.037) | .34 (.037) | |

| BFCRS | – | .66 (<.001) | .72 (<.001) | ||

| UPDRS III | – | .55 (<.001) |

Spearman rank correlations, p-values are FDR corrected. CPZ – chlorpromazine equivalents, BFCRS – Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale, SANS - Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, UPDRS III – motor part of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

Fig. 1.

Correlation matrix of physical activity, motor rating scales, negative symptom ratings, age, and antipsychotic medication in CPZ equivalent.

3.3. Catatonia vs. non-catatonia patients

According to the BFCRS screening instrument, 22 patients qualified for catatonia (13 men and 9 women), while 30 had no catatonia (20 men and 10 women). Groups did not differ in sex (Chi2 = 0.31, df = 1, p = .77). Patients with catatonia had lower activity levels, more negative symptoms and higher scores on Parkinsonism and abnormal involuntary movements (see Table 2). Note that 14 of the 22 patients with catatonia also qualified for DSM-5 catatonia criteria.

Table 2.

Comparison between patients with and patients without current catatonia.

| Catatonia (n = 22) | No catatonia (n = 30) | Non-parametric statistic | ANCOVA correcting for age and CPZ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | U | p | F | p | |

| Age (y) | 38.6 | 12.5 | 35.3 | 12.0 | 275 | .313 | – | – |

| CPZ (mg) | 623.6 | 436.5 | 344.6 | 340.2 | 181 | .005 | – | – |

| Activity level (counts/h) | 10′ 866.0 | 5′ 144.6 | 17′ 113.3 | 8′ 953.3 | 170 | .003a | 6.0 | .002 |

| UPDRS III | 15.9 | 8.4 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 88 | <.001a | 11.7 | <.001 |

| AIMS | 8.8 | 7.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 7 | <.001a | 12.4 | <.001 |

| NES | 13.5 | 13.4 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 74 | .990 | .6 | .612 |

| SANS | 73.2 | 27.2 | 30.8 | 21.4 | 76 | <.001a | 13.1 | <.001 |

| PANSS pos | 15.6 | 6.7 | 17.9 | 5.9 | 249 | .137 | .9 | .435 |

| PANSS neg | 31.6 | 8.4 | 18.6 | 6.3 | 70 | <.001a | 13.5 | <.001 |

| PANSS total | 94.8 | 22.2 | 71.2 | 16.3 | 144 | .001a | 7.3 | <.001 |

Indicates group differences that survive Bonferroni correction, AIMS – abnormal involuntary movement scale, CPZ – chlorpromazine equivalents, NES – neurological evaluation Scale, PANSS – positive and negative syndrome scales (positive, negative and total scores), SANS – scale for the assessment of negative symptoms, UPDRS III – motor part of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

3.4. Correlation of catatonia factors with PA

Activity levels correlated with the BFCRS factor decreased (rS = − .31, p = .025), but not with the factors increased or abnormal (r < −0.21, p > .14).

4. Discussion

Physical activity (PA) is critical for health related outcomes, but lower in patients with schizophrenia than in healthy controls. Age, body mass index, and medication side effects are potential contributors to lower PA in subjects with severe mental illness. However, the association with other potential factors such as motor abnormalities on PA have not been investigated so far. This study applied an instrumental measure of PA, i.e. wrist actigraphy, in 52 patients to explore cross-sectional correlations between activity levels (AL) and the severity of hypokinetic motor abnormalities. We found that age, catatonia, and Parkinsonism are associated with low activity levels in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In addition, patients with current catatonia had lower PA and higher ratings of negative symptoms, Parkinsonism, and abnormal involuntary movements compared to patients without catatonia.

The correlation of low AL with ratings of parkinsonism and catatonia could reflect several underlying issues in psychosis. The most likely explanation is that parkinsonism and catatonia both exert effects on the motor system of patients resulting in reduced PA. Reduced neural output from the basal ganglia and the primary motor cortex in patients with psychosis and catatonia or Parkinsonism has been suggested by neuroimaging studies (Hirjak et al., 2020; Viher et al., 2020; Walther et al., 2017; Wasserthal et al., 2020; Wolf et al., 2021). This reduced output will affect all motor behaviors and thus influence measures of PA. Another possibility could be an indirect effect, i.e. low PA contributes to or exacerbates a variety of motor abnormalities, including parkinsonism and catatonia. We may speculate that reduced motor output resulting from pathological motor circuit activity may be further deteriorated by sedentary behaviors through a lack of training of this circuit. Indeed, in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease physical exercise helps improving motor outcomes, i.e. reducing bradykinesia (Tiihonen et al., 2021). Similarly, anecdotal reports in chronic catatonia suggest beneficial effects of physical exercise (Heckers and Walther, 2021). A third option, which is not mutually exclusive, is supported in part by the fact that correlations were moderate, is that these phenomena may result from multiple partially overlapping but also distinct pathophysiological mechanisms (Mittal et al., 2021a). Finally, a number of clinical parameters such as dosage of current medication or antipsychotic substance used could exert negative effects on both PA and motor abnormalities (Walther et al., 2010). However, while current CPZ were moderately correlated with parkinsonism, catatonia, and negative symptom severity, CPZ was unrelated to our objective measure of PA.

These findings extend previous knowledge by demonstrating that multiple hypokinetic movement disorders, i.e. catatonia and Parkinsonism, may contribute to lower PA in schizophrenia. The result corroborates the only other study applying actigraphy and ratings of Parkinsonism (Pieters et al., 2021). Findings are similar even though the accelerometer placement differed, i.e. hip vs. wrist of the non-dominant arm. While replicating findings on the role of Parkinsonism in PA, this study is the first to correlate the severity of catatonia according to the BFCRS with activity levels measured via actigraphy. Because of its frequency of 8% in clinical populations (Solmi et al., 2018), it is important to consider catatonia as a transdiagnostic motor abnormality. Catatonia may present with increased, decreased, or abnormal psychomotor activity (Heckers and Walther, 2021; Hirjak et al., 2020; Walther et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2015). Our data demonstrate that lower activity levels correlate with the score on the BFCRS factor decreased activity. While the BFCRS total score was associated with lower PA as hypothesized, single items indicating increased psychomotor activity (e. g. excitement, combativeness) could correlate with higher PA in other samples. More often, however, catatonia presents with decreased psychomotor activity (Wilson et al., 2015), affecting physical activity in the same way as age or Parkinsonism.

Our finding of reduced activity levels in patients with current catatonia is in line with a previous report of our group that compared patients with catatonic schizophrenia to patients with paranoid schizophrenia using wrist actigraphy (Walther et al., 2009). Moreover, the current study corroborates previous actigraphy studies reporting reduced activity levels in schizophrenia patients or subjects at clinical high risk (CHR) with pronounced negative symptoms (Damme et al., 2021; Docx et al., 2013; Kluge et al., 2018; Mittal et al., 2013; Walther et al., 2009; Walther et al., 2014). Finally, our results align with studies reporting moderate to strong correlation between hypokinetic motor abnormalities, e.g. parkinsonism and catatonia, parkinsonism and negative symptoms, catatonia and negative symptoms (Docx et al., 2012; McKenna et al., 1988; Peralta et al., 2012; Rogers, 1985; Sambataro et al., 2020). Still, the correlation was only observed for the PANSS negative syndrome scale, but not for SANS total.

Some of this correlation is likely to stem from conceptual overlap, as all current rating scales have been developed within specific frameworks and focus on one motor phenomenon or on negative symptoms. However, on a behavioral or neurophysiological level the differentiation between the hypokinetic phenomena is close to impossible; therefore, the nature of extrapyramidal signs, catatonia, and negative symptoms such as avolition remains a major challenge to the field (Mittal et al., 2021a,b). Instrumental assessment of motor behavior holds promise in measuring motor behavior precisely (van Harten et al., 2017). However, a revision of current concepts is still needed. This study demonstrates that objectively assessed low physical activity in schizophrenia correlates with all hypokinetic phenomena, rendering the link between low physical activity and negative syndrome scores less specific as previously thought.

The etiology of sedentary behaviors or low PA is still subject of investigations. Future longitudinal studies need to address heterogeneity, i.e. few patients present with pure forms of hypokinetic motor abnormalities, as these behaviors overlap substantially. Most motor phenomena manifest for longer periods of time, may wax and wane, but have the potential to impact physical activity of subjects in addition to unspecific effects of age and environmental enrichment (Mittal et al., 2021a). Another way to make progress would be the revision of the current concepts of motor abnormalities. This would also aid the interpretation of the rising number of excellent neuroimaging studies in the field that have provided first preliminary insight but struggle to translate pathology to specific motor behaviors (Hirjak et al., 2020; Mittal et al., 2021a; Northoff et al., 2021; Walther et al., 2017; Walther et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2021). Finally, if we achieve a better understanding of the pathobiology of the various motor abnormalities, we may improve efforts to test novel treatments. Future clinical trials will need to establish whether hypokinetic motor abnormalities will be ameliorated with physical exercise interventions increasing PA or whether PA can be increased by treating hypokinetic motor abnormalities with brain stimulation. Indeed, first studies are targeting motor abnormalities with non-invasive brain stimulation with encouraging effects that require replication and extension (Gupta et al., 2018; Lefebvre et al., 2020; Walther et al., 2020; Walther et al., 2020). If some of these novel treatments prove to increase PA, we would also expect benefits for general health outcomes in subjects with schizophrenia.

The strength of this study include the objective assessment of PA and careful clinical assessment of motor abnormalities. Limitations include the lack of longitudinal data, the moderate sample size, and the enrichment of the sample with subjects with severe psychomotor slowing, which may limit the generalizability to all subjects with schizophrenia. Still, psychomotor slowing is frequently observed in this disorder. Importantly, the current dose of antipsychotics was unrelated to PA, but studies in unmedicated first episode patients would add important information on this issue. In an ideal study, ratings of catatonia and parkinsonism would have been conducted independently, i.e. by separate raters blind to the other’s evaluation. Future studies will include longitudinal assessments to study the course of hypokinetic motor abnormalities as well as further objective measures of PA, such as automated gait analyses, which may help to disentangle parkinsonism from catatonia in psychosis. Finally, clinical trials with physical exercise and brain stimulation will shed light on the mechanism between PA and hypokinetic movement disorders.

In sum, this study demonstrates that low PA in schizophrenia is linked to age, negative symptoms, and hypokinetic motor abnormalities such as catatonia and parkinsonism. Future efforts will include multiple objective assessments of motor behavior in longitudinal studies to disentangle the contributions of various motor abnormalities frequently seen in psychosis.

5. Contributors

Dr. Walther designed the study, wrote the protocol, acquired funding, supervised data acquisition, analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Drs. Vladimirova, Alexaki, Schäppi and Stegmayer recruited subjects and conducted assessments. All authors discussed findings and edited the manuscript.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health R01MH118741 to Shankman, Mittal, and Walther.

Swiss National Science Foundation grant 152619 to Walther.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

Dr. Walther received honoraria from Janssen, Lundbeck, Mepha, Neurolite, and Sunovion. Dr. Stegmayer received honoraria from Lundbeck and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. All other authors report no competing interests.

References

- Andreasen NC, 1989. The scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br. J. Psychiatry Suppl, 49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW, 1989. The Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES): a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Res 27, 335–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, Dowling F, Francis A, 1996. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 93, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damme KSF, Sloan RP, Bartels MN, Ozsan A, Ospina LH, Kimhy D, Mittal VA, 2021. Psychosis risk individuals show poor fitness and discrepancies with objective and subjective measures. Sci. Rep 11, 9851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docx L, Morrens M, Bervoets C, Hulstijn W, Fransen E, De Hert M, Baeken C, Audenaert K, Sabbe B, 2012. Parsing the components of the psychomotor syndrome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 126, 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docx L, Sabbe B, Provinciael P, Merckx N, Morrens M, 2013. Quantitative psychomotor dysfunction in schizophrenia: a loss of drive, impaired movement execution or both? Neuropsychobiology 68, 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S, Elton RL, Members UP, 1987. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Goldstein M, Calne DB (Eds.), Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease, vol. 2. Macmillan Healthcare Information, Florham Park, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta T, Dean DJ, Kelley NJ, Bernard JA, Ristanovic I, Mittal VA, 2018. Cerebellar transcranial direct current stimulation improves procedural learning in nonclinical psychosis: a double-blind crossover study. Schizophr. Bull 44 (6), 1373–1380. 10.1093/schbul/sbx179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W, 1976. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Heckers S, Walther S, 2021. Caring for the patient with catatonia. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 560–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirjak D, Kubera KM, Wolf RC, Northoff G, 2020a. Going back to kahlbaum’s psychomotor (and GABAergic) origins: is catatonia more than just a motor and dopaminergic syndrome? Schizophr. Bull 46, 272–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirjak D, Rashidi M, Kubera KM, Northoff G, Fritze S, Schmitgen MM, Sambataro F, Calhoun VD, Wolf RC, 2020b. Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging data fusion reveals distinct patterns of abnormal brain structure and function in catatonia. Schizophr. Bull 46, 202–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorthoj C, Sturup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M, 2017. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA, 1987. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 13, 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge A, Kirschner M, Hager OM, Bischof M, Habermeyer B, Seifritz E, Walther S, Kaiser S, 2018. Combining actigraphy, ecological momentary assessment and neuroimaging to study apathy in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 195, 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdyak P, Mallia E, de Oliveira C, Carvalho AF, Kozloff N, Zaheer J, Tempelaar WM, Anderson KK, Correll CU, Voineskos AN, 2021. Mortality after the first diagnosis of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Schizophr. Bull 47, 864–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre S, Pavlidou A, Walther S, 2020. What is the potential of neurostimulation in the treatment of motor symptoms in schizophrenia? Expert Rev. Neurother 20, 697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna PJ, Mortimer AM, Lund CE, 1988. The motor disorders of severe psychiatric illness: a conflict of paradigms. Br. J. Psychiatry 152, 863–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Bernard JA, Strauss GP, Walther S, 2021a. New insights into sedentary behavior highlight the need to revisit the way we see motor symptoms in psychosis. Schizophr. Bull 47 (4), 877–879. 10.1093/schbul/sbab057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Bernard JA, Walther S, 2021b. Cerebellar-thalamic circuits play a critical role in psychomotor function. Mol. Psychiatr 26 (8), 3666–3668. 10.1038/s41380-020-00935-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Gupta T, Orr JM, Pelletier-Baldelli A, Dean DJ, Lunsford-Avery JR, Smith AK, Robustelli BL, Leopold DR, Millman ZB, 2013. Physical activity level and medial temporal health in youth at ultra high-risk for psychosis. J. Abnorm. Psychol 122, 1101–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen RE, Banner J, Jensen SE, 2021. Cardiovascular disease in patients with severe mental illness. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 18, 136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Hirjak D, Wolf RC, Magioncalda P, Martino M, 2021. All roads lead to the motor cortex: psychomotor mechanisms and their biochemical modulation in psychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatr 26, 92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne KJ, Walther S, Shankman SA, Mittal VA, 2020. Psychomotor slowing in schizophrenia: implications for endophenotype and biomarker development. Biomark Neuropsychiatry 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta V, Basterra V, Campos MS, de Jalon EG, Moreno-Izco L, Cuesta MJ, 2012. Characterization of spontaneous Parkinsonism in drug-naive patients with nonaffective psychotic disorders. Eur. Arch. Psychiatr. Clin. Neurosci 262, 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta V, Cuesta MJ, 2010. The effect of antipsychotic medication on neuromotor abnormalities in neuroleptic-naive nonaffective psychotic patients: a naturalistic study with haloperidol, risperidone, or olanzapine. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta V, Cuesta MJ, 2017. Motor abnormalities: from neurodevelopmental to neurodegenerative through “functional” (Neuro)Psychiatric disorders. Schizophr. Bull 43, 956–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters LE, Deenik J, Tenback DE, van Oort J, van Harten PN, 2021. Exploring the relationship between movement disorders and physical activity in patients with schizophrenia: an actigraphy study. Schizophr. Bull 47 (4), 906–914. 10.1093/schbul/sbab028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D, 1985. The motor disorders of severe psychiatric illness: a conflict of paradigms. Br. J. Psychiatry 147, 221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambataro F, Fritze S, Rashidi M, Topor CE, Kubera KM, Wolf RC, Hirjak D, 2020. Moving forward: distinct sensorimotor abnormalities predict clinical outcome after 6 months in patients with schizophrenia. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 36, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servaas MN, Kos C, Gravel N, Renken RJ, Marsman JC, van Tol MJ, Aleman A, 2019. Rigidity in motor behavior and brain functioning in patients with schizophrenia and high levels of apathy. Schizophr. Bull 45, 542–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC, 1998. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatr 59 (Suppl. 20), 22–33 quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmi M, Pigato GG, Roiter B, Guaglianone A, Martini L, Fornaro M, Monaco F, Carvalho AF, Stubbs B, Veronese N, Correll CU, 2018. Prevalence of catatonia and its moderators in clinical samples: results from a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Schizophr. Bull 44 (5), 1133–1150. 10.1093/schbul/sbx157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs B, Firth J, Berry A, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Gaughran F, Veronesse N, Williams J, Craig T, Yung AR, Vancampfort D, 2016. How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophr. Res 176, 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen M, Westner BU, Butz M, Dalal SS, 2021. Parkinson’s disease patients benefit from bicycling - a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 7, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Harten PN, Walther S, Kent JS, Sponheim SR, Mittal VA, 2017. The clinical and prognostic value of motor abnormalities in psychosis, and the importance of instrumental assessment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 80, 476–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Mugisha J, Hallgren M, Probst M, Ward PB, Gaughran F, De Hert M, Carvalho AF, Stubbs B, 2017. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatr 16, 308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Knapen J, Probst M, Scheewe T, Remans S, De Hert M, 2012. A systematic review of correlates of physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 125, 352–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viher PV, Stegmayer K, Federspiel A, Bohlhalter S, Wiest R, Walther S, 2020. Altered diffusion in motor white matter tracts in psychosis patients with catatonia. Schizophr. Res 220, 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Alexaki D, Schoretsanitis G, Weiss F, Vladimirova I, Stegmayer K, Strik W, Schäppi L, 2020a. Inhibitory repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to treat psychomotor slowing: a transdiagnostic, mechanism-based randomized double-blind controlled trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open 1. [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Horn H, Razavi N, Koschorke P, Muller TJ, Strik W, 2009a. Quantitative motor activity differentiates schizophrenia subtypes. Neuropsychobiology 60, 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Horn H, Razavi N, Koschorke P, Wopfner A, Muller TJ, Strik W, 2010. Higher motor activity in schizophrenia patients treated with olanzapine versus risperidone. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol 30, 181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Koschorke P, Horn H, Strik W, 2009b. Objectively measured motor activity in schizophrenia challenges the validity of expert ratings. Psychiatr. Res 169, 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Kunz M, Muller M, Zurcher C, Vladimirova I, Bachofner H, Scherer KA, Nadesalingam N, Stegmayer K, Bohlhalter S, Viher PV, 2020b. Single session transcranial magnetic stimulation ameliorates hand gesture deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 46, 286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Mittal VA, 2017. Motor system pathology in psychosis. Curr. Psychiatr. Rep 19, 97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Ramseyer F, Horn H, Strik W, Tschacher W, 2014a. Less structured movement patterns predict severity of positive syndrome, excitement, and disorganization. Schizophr. Bull 40, 585–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Schappi L, Federspiel A, Bohlhalter S, Wiest R, Strik W, Stegmayer K, 2017a. Resting-state hyperperfusion of the supplementary motor area in catatonia. Schizophr. Bull 43, 972–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Stegmayer K, Federspiel A, Bohlhalter S, Wiest R, Viher PV, 2017b. Aberrant hyperconnectivity in the motor system at rest is linked to motor abnormalities in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr. Bull 43, 982–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Stegmayer K, Horn H, Razavi N, Muller TJ, Strik W, 2014b. Physical activity in schizophrenia is higher in the first episode than in subsequent ones. Front. Psychiatr 5, 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Stegmayer K, Wilson JE, Heckers S, 2019. Structure and neural mechanisms of catatonia. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 610–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, Strik W, 2012. Motor symptoms and schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology 66, 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther S, van Harten PN, Waddington JL, Cuesta MJ, Peralta V, Dupin L, Foucher JR, Sambataro F, Morrens M, Kubera KM, Pieters LE, Stegmayer K, Strik W, Wolf RC, Hirjak D, 2020c. Movement disorder and sensorimotor abnormalities in schizophrenia and other psychoses - European consensus on assessment and perspectives. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 38, 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserthal J, Maier-Hein KH, Neher PF, Northoff G, Kubera KM, Fritze S, Harneit A, Geiger LS, Tost H, Wolf RC, Hirjak D, 2020. Multiparametric mapping of white matter microstructure in catatonia. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 1750–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichniak A, Skowerska A, Chojnacka-Wojtowicz J, Taflinski T, Wierzbicka A, Jernajczyk W, Jarema M, 2011. Actigraphic monitoring of activity and rest in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine or risperidone. J. Psychiatr. Res 45, 1381–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JE, Niu K, Nicolson SE, Levine SZ, Heckers S, 2015. The diagnostic criteria and structure of catatonia. Schizophr. Res 164, 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf RC, Kubera KM, Waddington JL, Schmitgen MM, Fritze S, Rashidi M, Thieme CE, Sambataro F, Geiger LS, Tost H, Hirjak D, 2021. A neurodevelopmental signature of parkinsonism in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 231, 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]