Abstract

Asymmetric catalysis is a major theme of research in contemporary synthetic organic chemistry. The discovery of general strategies for highly enantioselective photochemical reactions, however, has been a relatively recent development, and the variety of photoreactions that can be conducted in a stereocontrolled manner is consequently somewhat limited. Asymmetric photocatalysis is complicated by the short lifetimes and high reactivities characteristic of photogenerated reactive intermediates; the design of catalyst architectures that can provide effective enantiodifferentiating environments for these intermediates while minimizing the participation of uncontrolled racemic background processes has proven to be a key challenge for progress in this field. This review provides a summary of the chiral catalyst structures that have been studied for solution-phase asymmetric photochemistry, including chiral organic sensitizers, inorganic chromophores, and soluble macromolecules. While some of these photocatalysts are derived from privileged catalyst structures that are effective for both ground-state and photochemical transformations, others are structural designs unique to photocatalysis and offer an insight into the logic required for highly effective stereocontrolled photocatalysis.

Graphical Abstact

1. Introduction

The chirality of a molecule can have a profound influence on its biological and physical properties. Methods that produce enantiomerically enriched products from achiral starting materials are therefore of particular importance for the synthesis of a variety of materials, including drug molecules, agrochemicals, and polymers. The 2001 Nobel Prize for Chemistry, awarded for the development of the field of asymmetric catalysis, underscores the centrality of this problem in contemporary synthetic chemistry.1–2 3 Several decades of sustained interest in enantioselective reaction method development has resulted in the elucidation of a large number of structurally diverse chiral catalyst architectures that effectively control stereochemical outcomes in almost every class of synthetically important transformation.

Photochemical reactions offer a conspicuous exception to this general trend. The emergence of general strategies for enantioselective catalytic photoreactions is a relatively recent development, and the variety of organic photoreactions that can be conducted in a highly enantioselective manner remains comparatively limited. This is despite the long fascination chemists have had with light-promoted reactions, both because of the distinctive reactive intermediates that are most readily available by photochemical activation, and because photochemical reactions often result in topologically complex molecular architectures that can be synthesized in no other way.4–5 6 It stands to reason, therefore, that there exist complications specific to enantioselective catalytic photochemical reactions in comparison to better-established asymmetric ground-state reactions. Correspondingly, the chiral catalyst structures that have proven to be most effective in asymmetric photochemistry have often been structurally unique.

One central challenge common to all areas of asymmetric catalysis is the problematic participation of racemic background processes. Product-forming reaction pathways that occur outside of the stereodifferentiating environment of a chiral catalyst necessarily result in racemic products. Thus, no matter how enantioselective a catalytic process might be, the enantioselectivity of the overall reaction is diminished if background processes are competitive. There are two features specific to photochemical activation that are uniquely challenging in this regard. The first is the possibility of competitive direct photoexcitation. If an achiral substrate molecule directly absorbs light under the conditions of a catalytic photoreaction, the resulting photoexcited species can react to give racemic product prior to interacting with the chiral catalyst. Second, many of the most widely exploited photocatalytic systems operate via collisional activation mechanisms. When a photocatalyst activates an organic substrate by a diffusional electron- or energy-transfer event, the encounter complex is typically short-lived. If dissociation of the deactivated photocatalyst and activated substrate is faster than the rate of subsequent bond formation, any chiral information associated with the photocatalyst cannot influence the stereochemical outcome of the reaction.

Thus, early investigations of catalytic asymmetric photochemistry that introduced chiral elements into well-studied organic sensitizers met with limited success.7, 8 Examples that resulted in measurable stereoinduction generally involved the formation of an exciplex, where a donor–acceptor interaction between the substrate and excited-state photocatalyst results in the formation of a longer-lived excited-state complex. Because the exciplex extends the lifetime of the encounter complex, product-formation can occur within the chiral environment of the photocatalyst. These studies provided a valuable proof-of-principle for the possibility of photocatalytic stereoinduction but suffered from low enantiomeric excess (ee) due to ill-defined substrate–catalyst interactions and relatively short exciplex lifetimes.

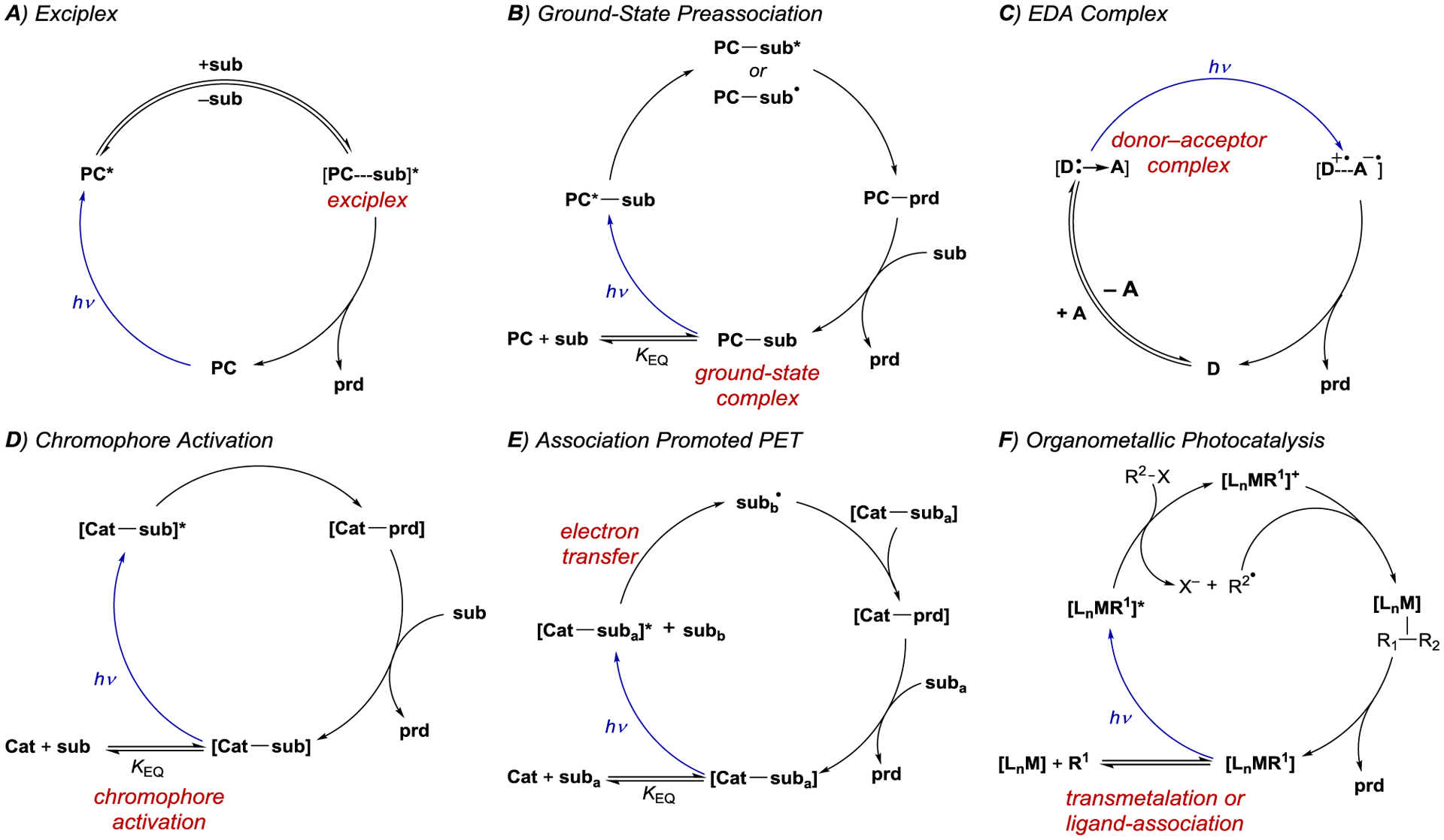

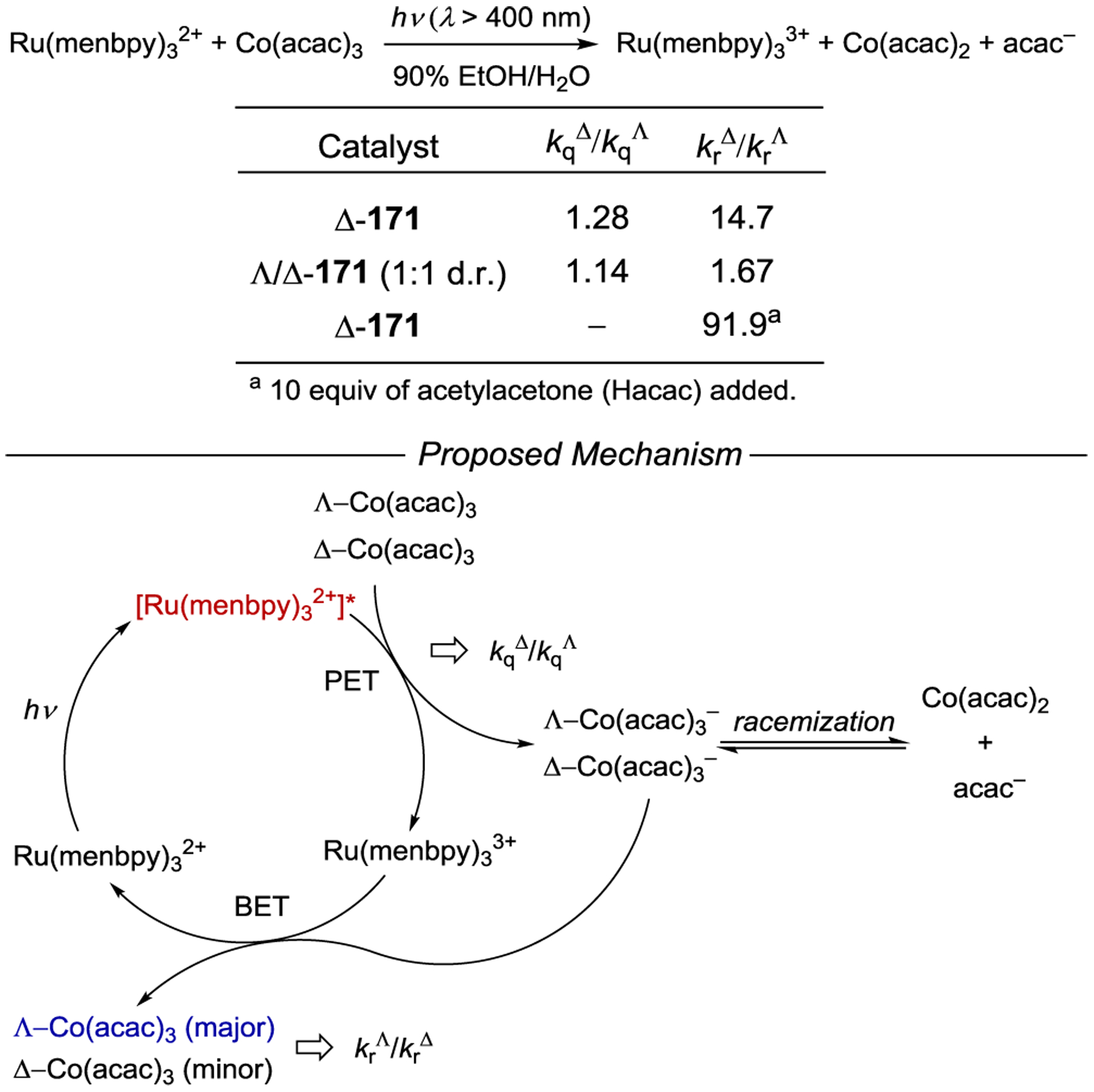

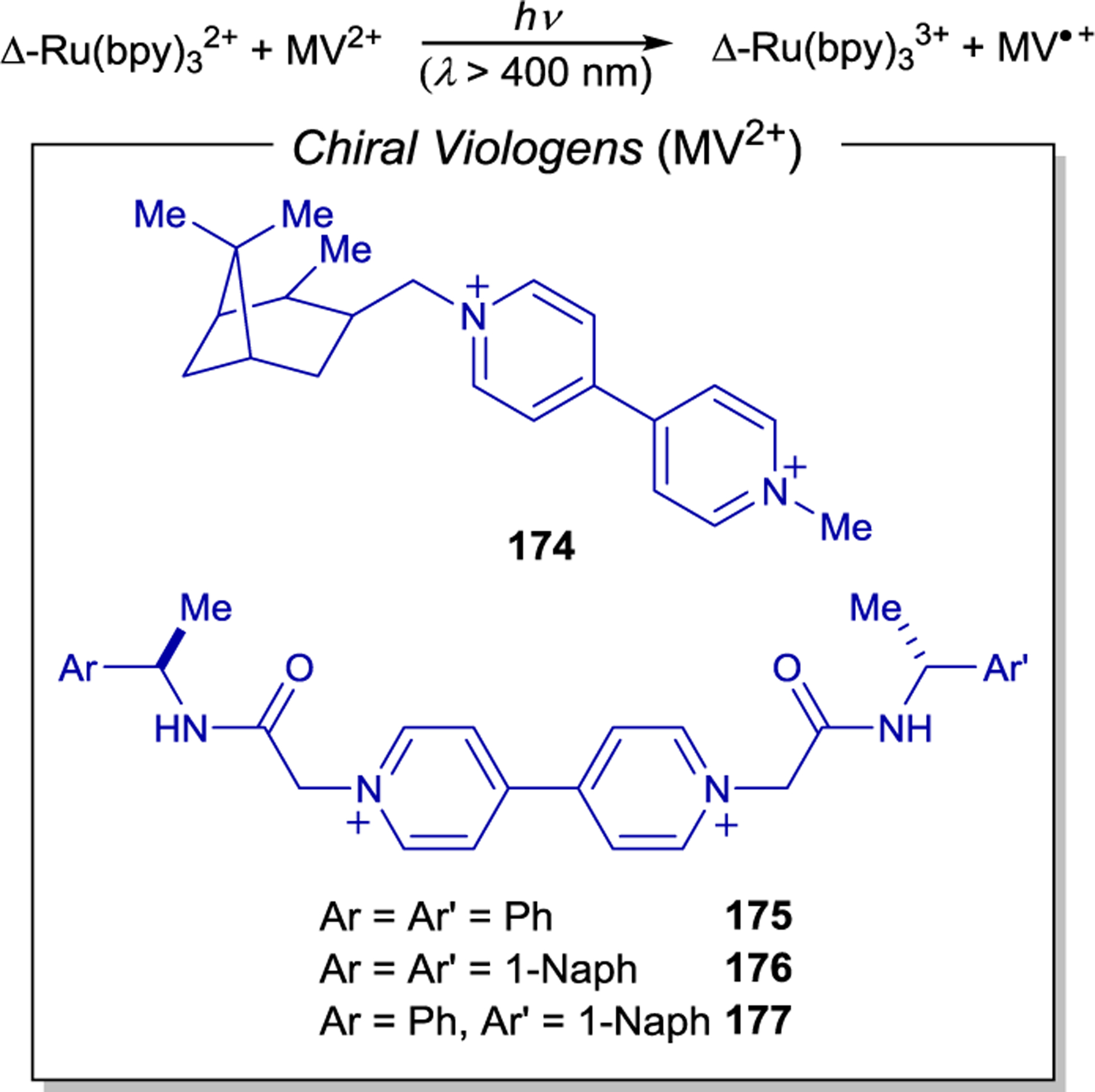

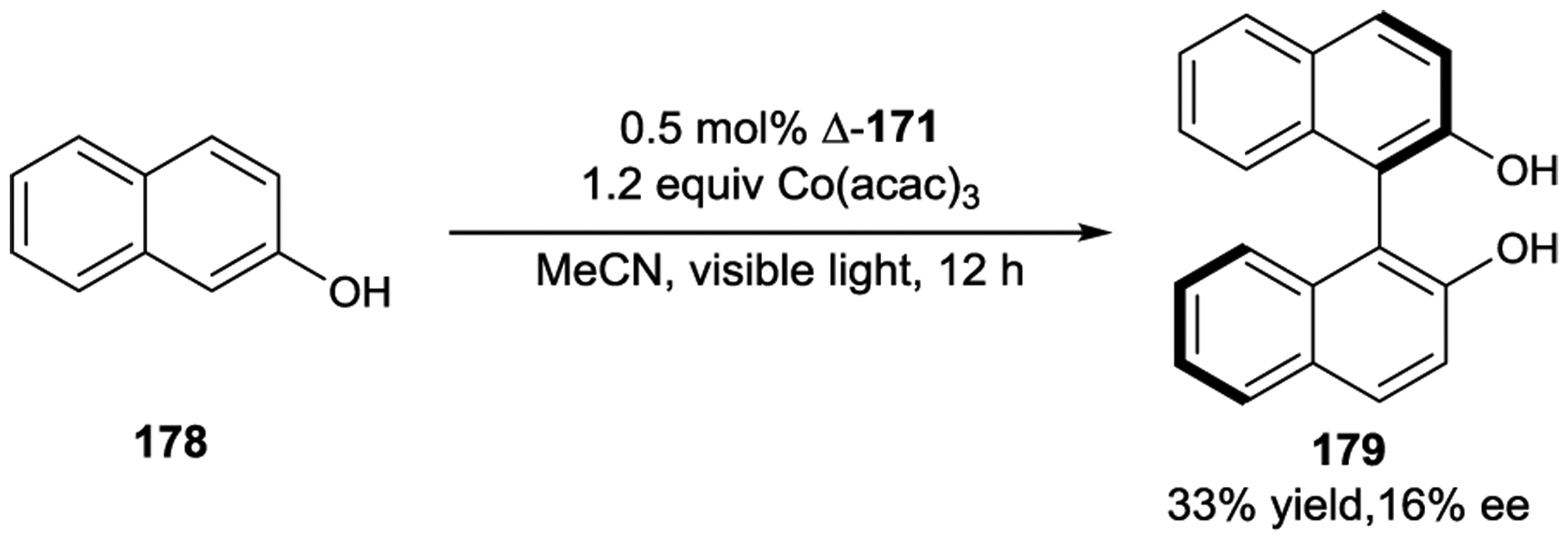

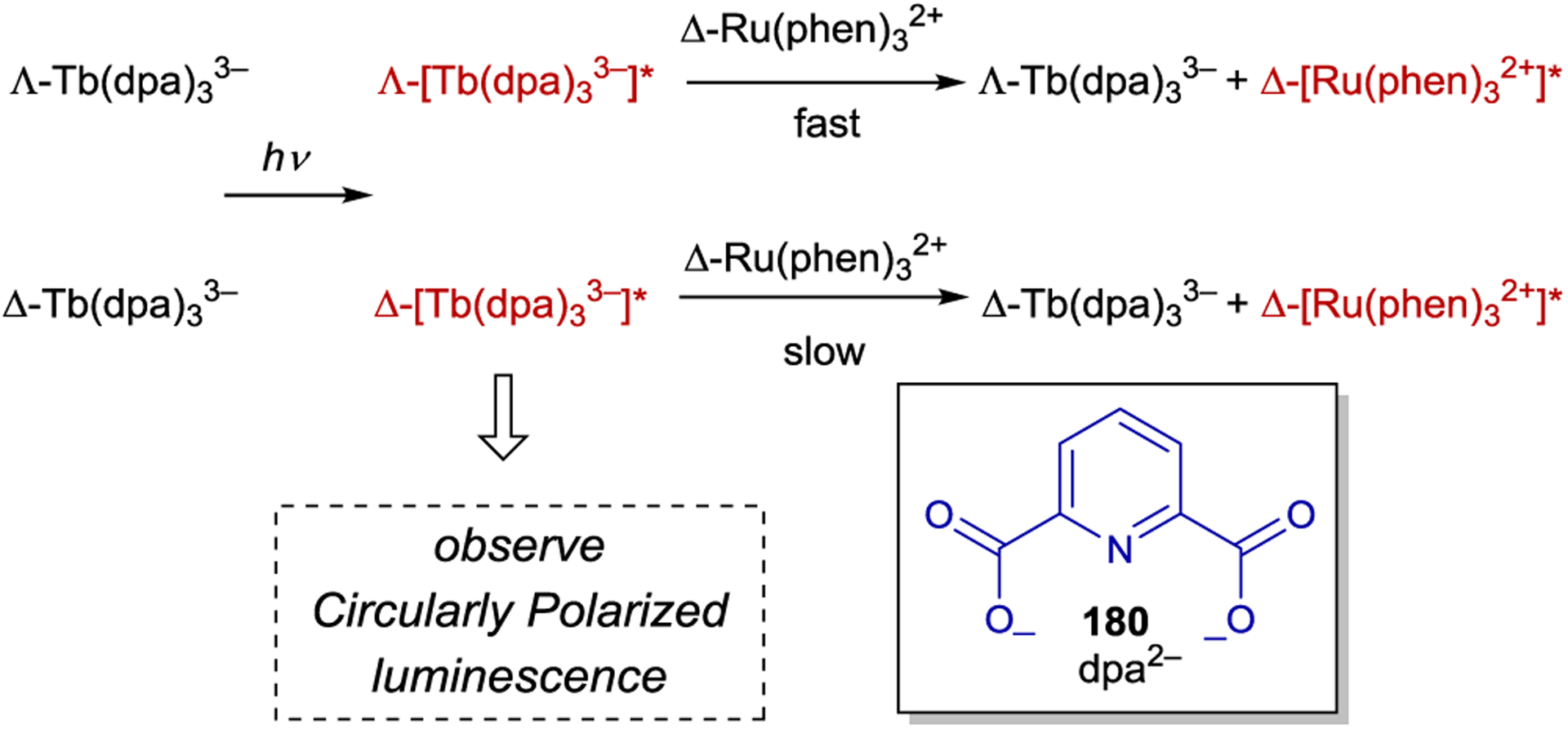

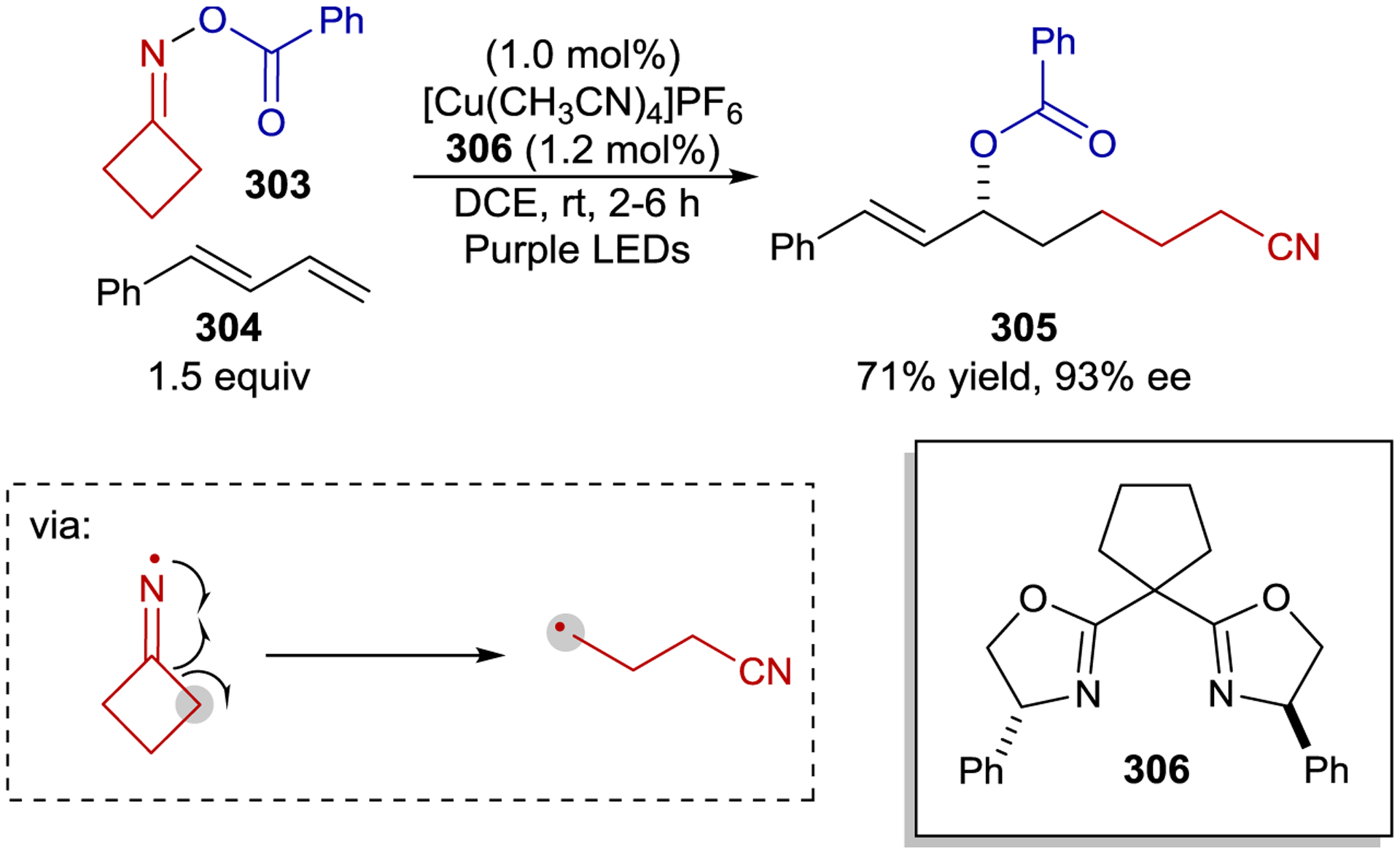

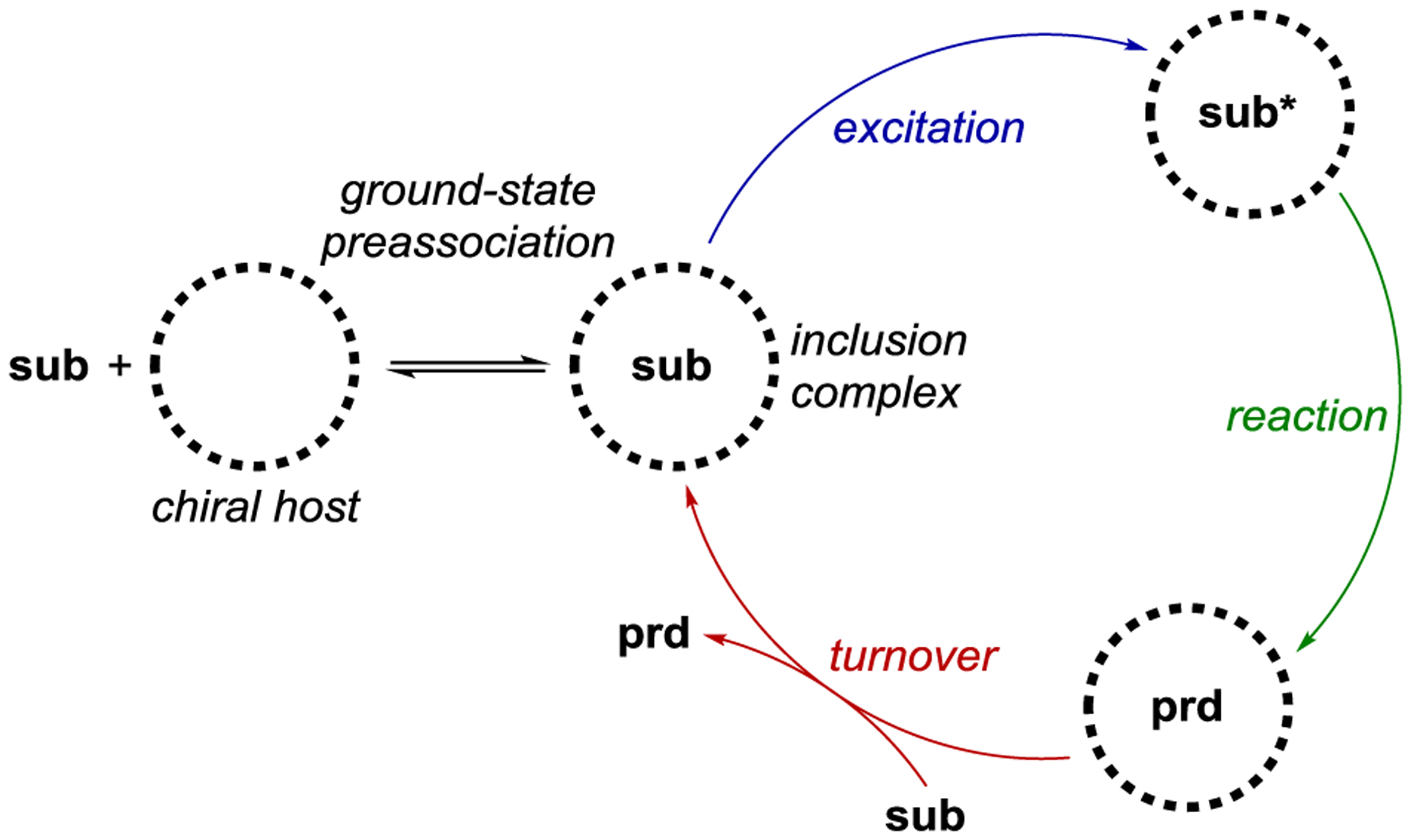

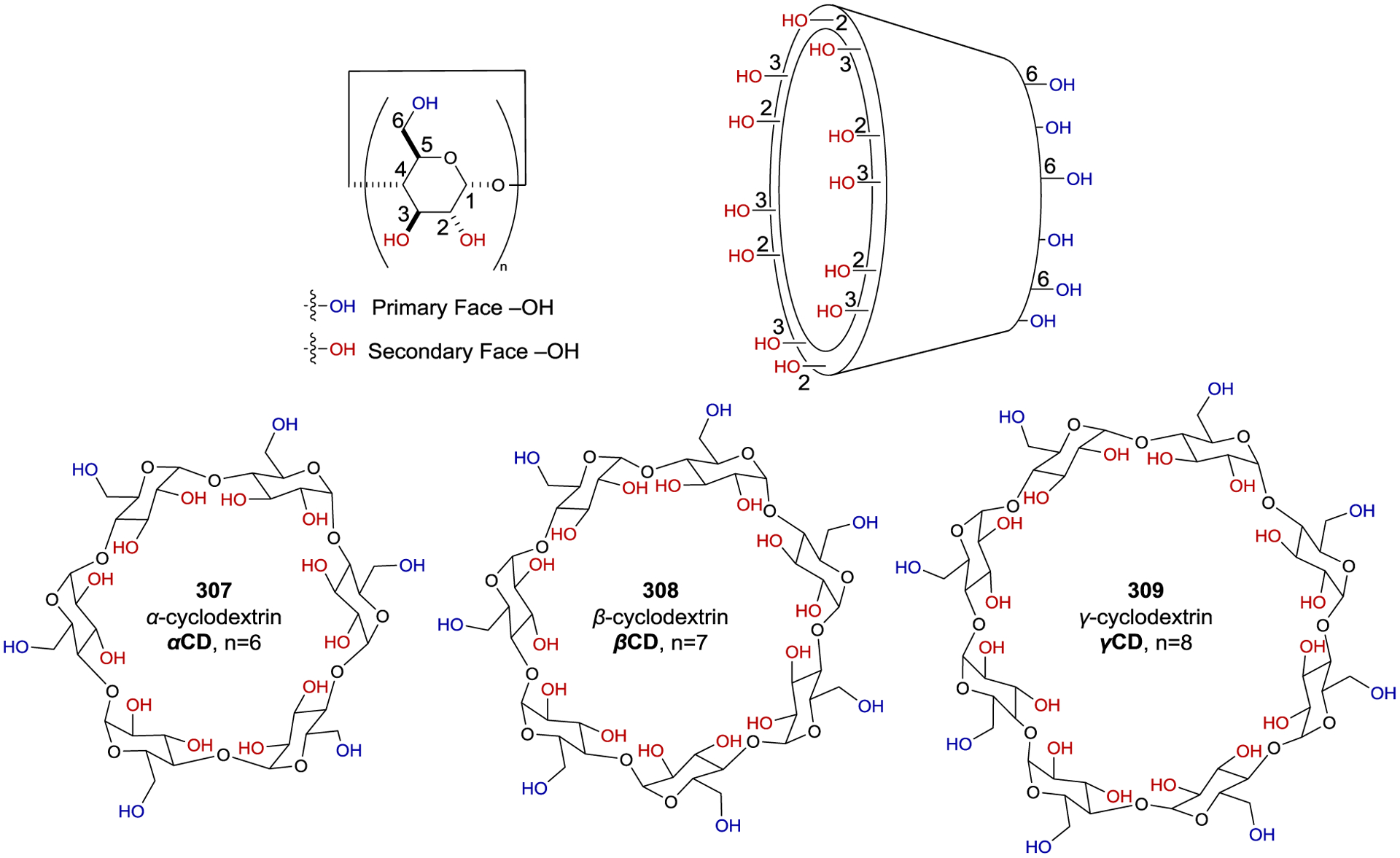

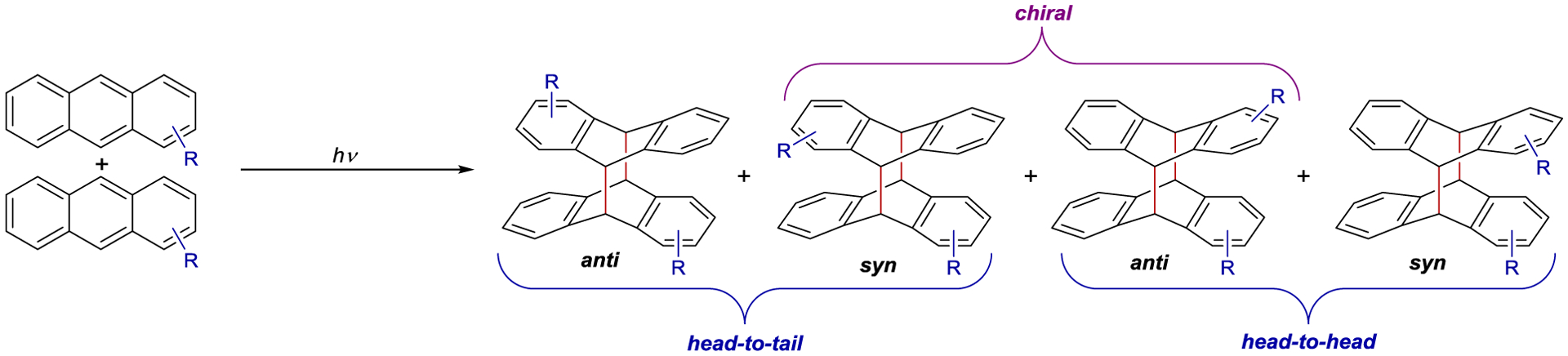

Highly enantioselective catalytic photoreactions have become increasingly common over the past two decades. A guiding strategy that underlies many of the most successful methods in asymmetric photocatalysis is the preassociation principle originally articulated for macromolecular photoactive hosts by Inoue9 and expanded for small molecule asymmetric photocatalysis by Krische.10 This principle argues that the participation of background product-forming pathways will be minimized when a chiral photocatalyst is capable of binding the substrate in the ground state. If the substrate in the complex is excited — either by direct excitation or sensitization — more readily than the free substrate, and if the rate of the photoreaction is faster than the rate of disassociation of the complex, then product formation will predominantly occur within the chiral environment of the photocatalyst with minimal competition from racemic background processes. Although Krische’s seminal example utilized hydrogen-bonding interactions as a strategy to enforce preassociation, many other strategies have subsequently been reported. These include the formation of electron donor–acceptor (EDA) complexes, where the formation of a ground-state association is driven by charge transfer between the catalyst and substrate; chromophore activation, where coordination of a chiral catalyst to a substrate results in a new compound with altered light-absorbing properties; association-induced photoinduced electron transfer (PET), where photon absorption is followed by a redox cascade generating reactive radicals that react with a ground-state activated substrate; and organometallic photocatalysis, where the formation of a new coordination complex engenders product-forming photochemical processes within the coordination sphere of the metal center (Scheme 1). The research area of asymmetric photochemistry has been the subject of several previous reviews.11–12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Scheme 1.

General Mechanisms of Enantiocontrol by Chiral Chromophores in Asymmetric Photocatalysis

While some privileged catalyst structures have proven to be equally applicable to both ground-state and excited-state asymmetric reactions, the challenges specific to photochemical activation have required the invention of novel catalyst structures. This review seeks to provide an examination of the field of catalytic enantioselective photochemistry through the lens of the structures that have proven to be useful as chiral photocatalysts.

The term “photocatalysis” has been used in a somewhat ambiguous fashion throughout the literature of synthetic photochemistry. For the purposes of this review, we adopt a broad definition of photocatalysis and cover any enantioselective catalytic reaction where the stereoinducing chiral catalyst forms part of the light-absorbing complex, regardless of the photophysical properties of the species in isolation. We exclude from this treatment dual-catalytic reactions where the chromophore and the chiral stereoinducing co-catalyst are separate molecular entities; this topic has been reviewed previously.21 The scope of this review is also limited to solution-phase photoreactions; stereoselective photochemistry in the solid state is a broad topic and merits separate treatment.22–23 24

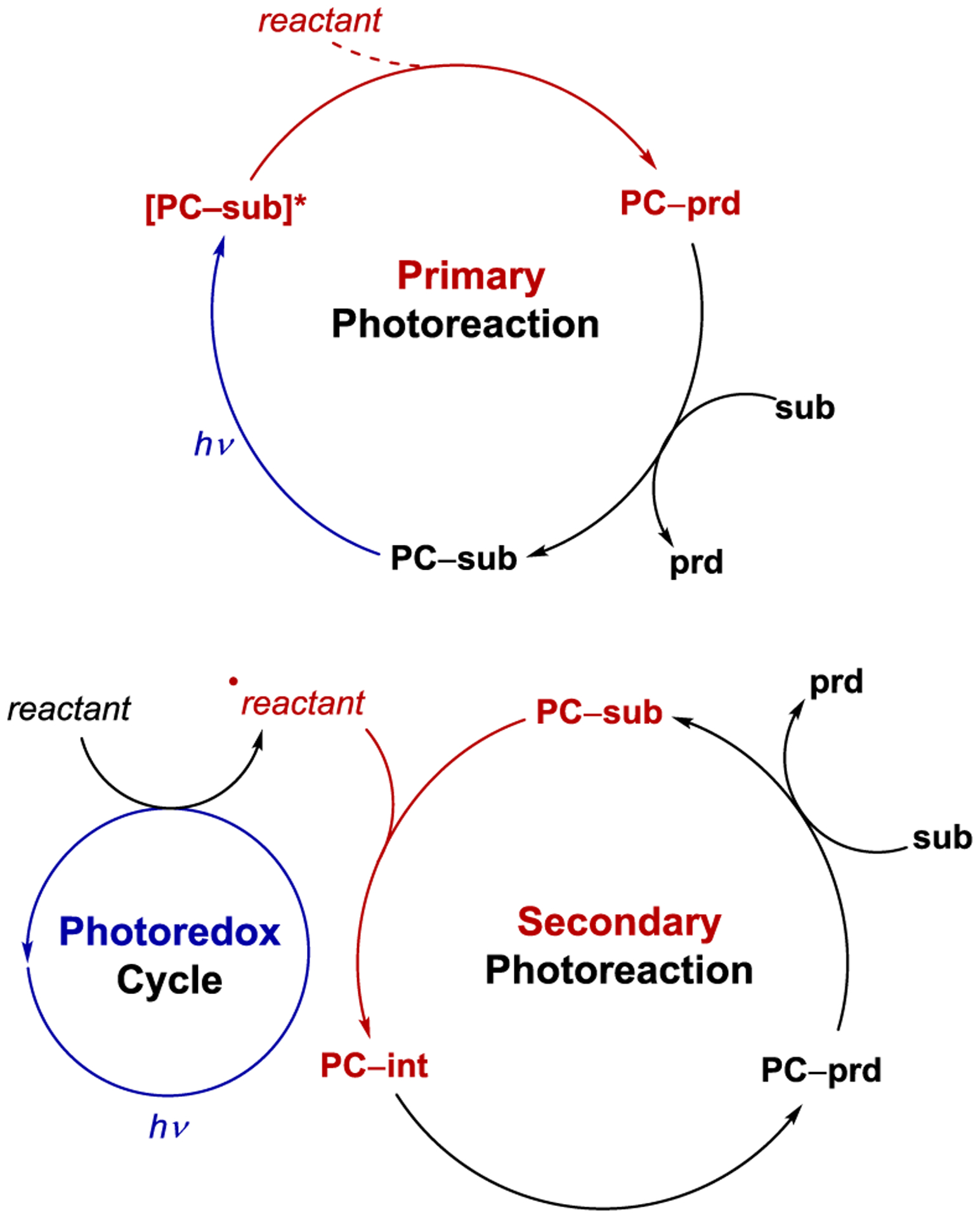

There are also important distinctions that can be made among the mechanisms of photocatalytic reactions involving the nature of the reactive intermediates participating in the key bond-forming events. Primary photoreactions are those that involve bond-forming processes of organic compounds in their electronically excited states. These are distinct from secondary photoreactions, in which the key bond-forming processes are those of photochemically generated reactive intermediates such as radicals or radical ions in their electronic ground states (Scheme 2). While the reactivity patterns available from primary and secondary photoreactions differ significantly, it can sometimes be challenging to unambiguously determine which is operative in a given photoreaction. This review thus covers both classes of photocatalytic reactions, and the organization of the topics centers on the structure of the chiral catalyst rather than on mechanistic considerations.

Scheme 2.

Primary Versus Secondary Photoreactions

2. Organic Chromophores

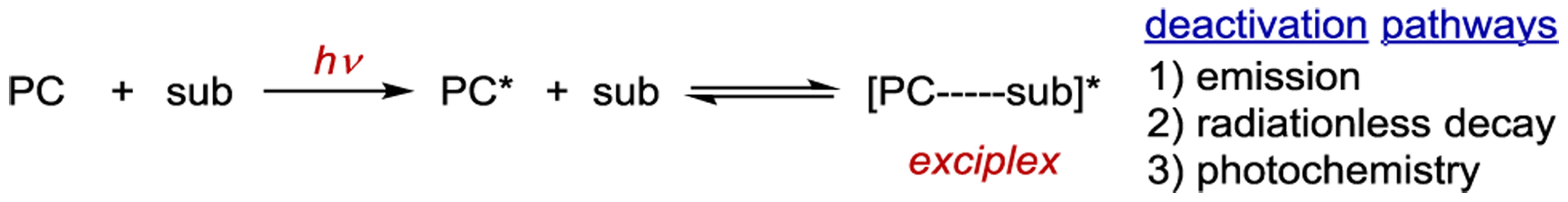

2.1. Arenes

Much of the early work in asymmetric photochemistry involved the use of chiral arene sensitizers capable of forming exciplexes. An exciplex is an electronically excited molecular complex formed between two species that are not associated in the ground state but are held together by charge-transfer interactions in the excited state (Scheme 3).25 Exciplexes have unique photophysical properties relative to the individual sensitizer and substrate. They have the potential to fluoresce (singlet exciplex) and phosphoresce (triplet exciplex), undergo radiationless decay, or chemically react to form a new species.26 Hence, the best spectroscopic evidence for the formation of an exciplex is the observation of quenching of the sensitizer fluorescence and the appearance of a new emission band that does not correspond to the emission of either component of the exciplex in isolation. Notably, substrate activation via exciplex formation is mechanistically distinct from energy transfer. In an exciplex, the exciton is shared between the sensitizer and the substrate, while during energy transfer, the exciton is transferred from the sensitizer to the substrate, resulting in a ground-state sensitizer.

Scheme 3.

Exciplex Formation and Deactivation Pathways

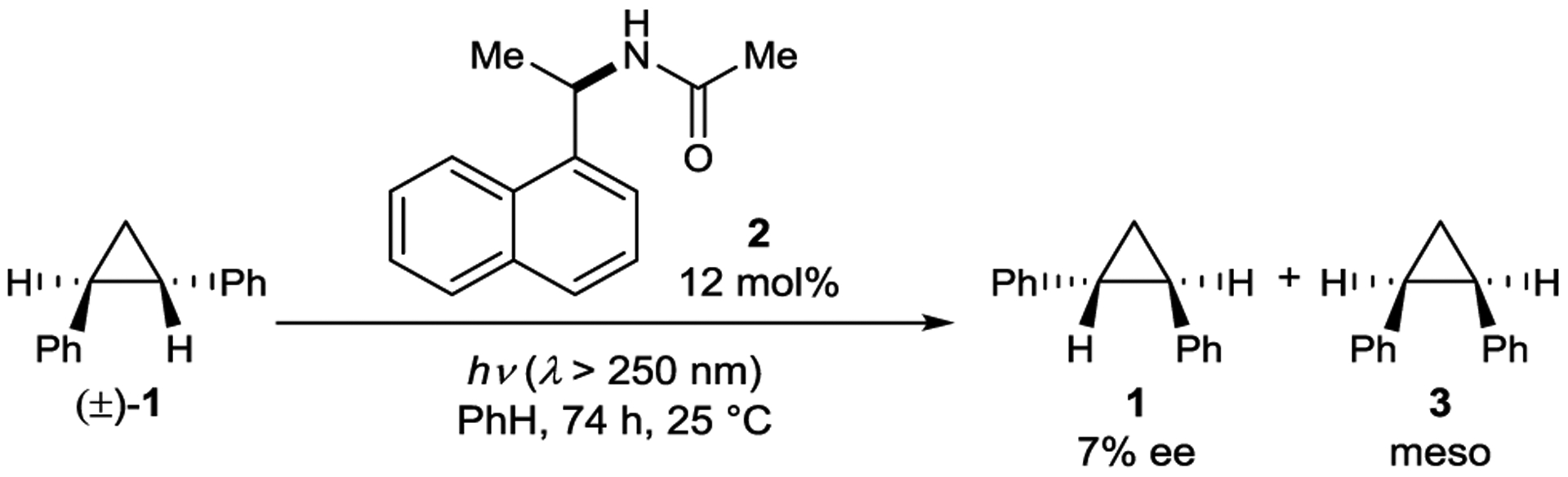

Hammond reported one of the first examples of an enantioselective photoreaction in 1965 (Scheme 4).27 An optically active naphthylamide sensitizer (2) effects the isomerization of cyclopropane 1 to a mixture of cis- and optically enriched trans-1,2-diphenylcyclopropanes upon irradiation with UV light. Notably, only a 12 mol% loading of 2 gives 1 in 7% ee.28, 29 Naphthylamides bound to silica were also tested as isomerization catalysts, but the enantioselectivity was reduced to 1% ee.30 Hammond initially proposed a triplet sensitization mechanism where different energy-transfer rate constants from the chiral sensitizer to (R)- and (S)-1 lead to enantioenrichment.31–32 33 However, it was later shown that the reaction proceeds through a singlet exciplex.34 Interconversion of (R)- and (S)-1 likely occurs via cleavage of the excited cyclopropane to a 1,3-diradical followed by ring-closure.

Scheme 4.

Cyclopropane Isomerization Catalyzed by a Naphthylamide Sensitizer

Naphthylamide sensitizers were also studied by Kagan for their ability to deracemize sulfoxides (Scheme 5). When racemic sulfoxide 4 is irradiated in the presence of 5, the optical purity of the recovered substrate is modestly enriched (12% ee).35, 36 Mechanistic studies on sulfoxide racemization performed by Hammond suggest that this deracemization proceeds through a singlet exciplex.37–38 39 The excited-state configurational lability of the sulfoxide could arise either from direct inversion via a planar electronically excited sulfoxide or from α-cleavage and subsequent radical–radical recombination.40, 41

Scheme 5.

Sulfoxide Deracemization Catalyzed by a Naphthylamide Sensitizer

Several chiral naphthylamide sensitizers were also examined in the 1,5-aryl shift, di-π-methane cascade rearrangement of racemic oxepinones. The ratio of sensitization rate constants (kR/kS = 1.04) suggests an enantioselective transformation, but the ee of the product was not measured.42 Weiss reported the deracemization of 2,3-pentadiene (6) catalyzed by chiral aromatic steroid 7 (Scheme 6).43 Allenes are axially chiral and configurationally stable in the ground state but can undergo stereochemical inversion via a planar, achiral excited state. The authors did not fully elucidate the mechanism but did note that singlet and triplet sensitization from the chiral sensitizer is thermodynamically endergonic.

Scheme 6.

Allene Deracemization Catalyzed by a Steroid Sensitizer

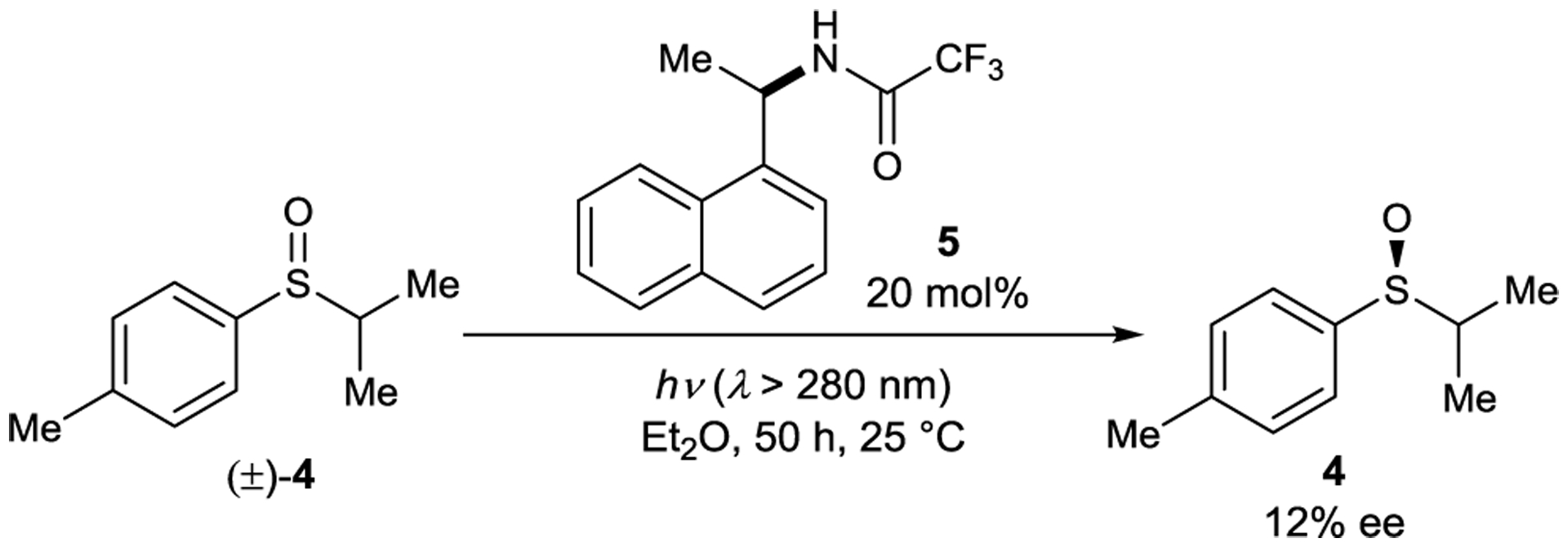

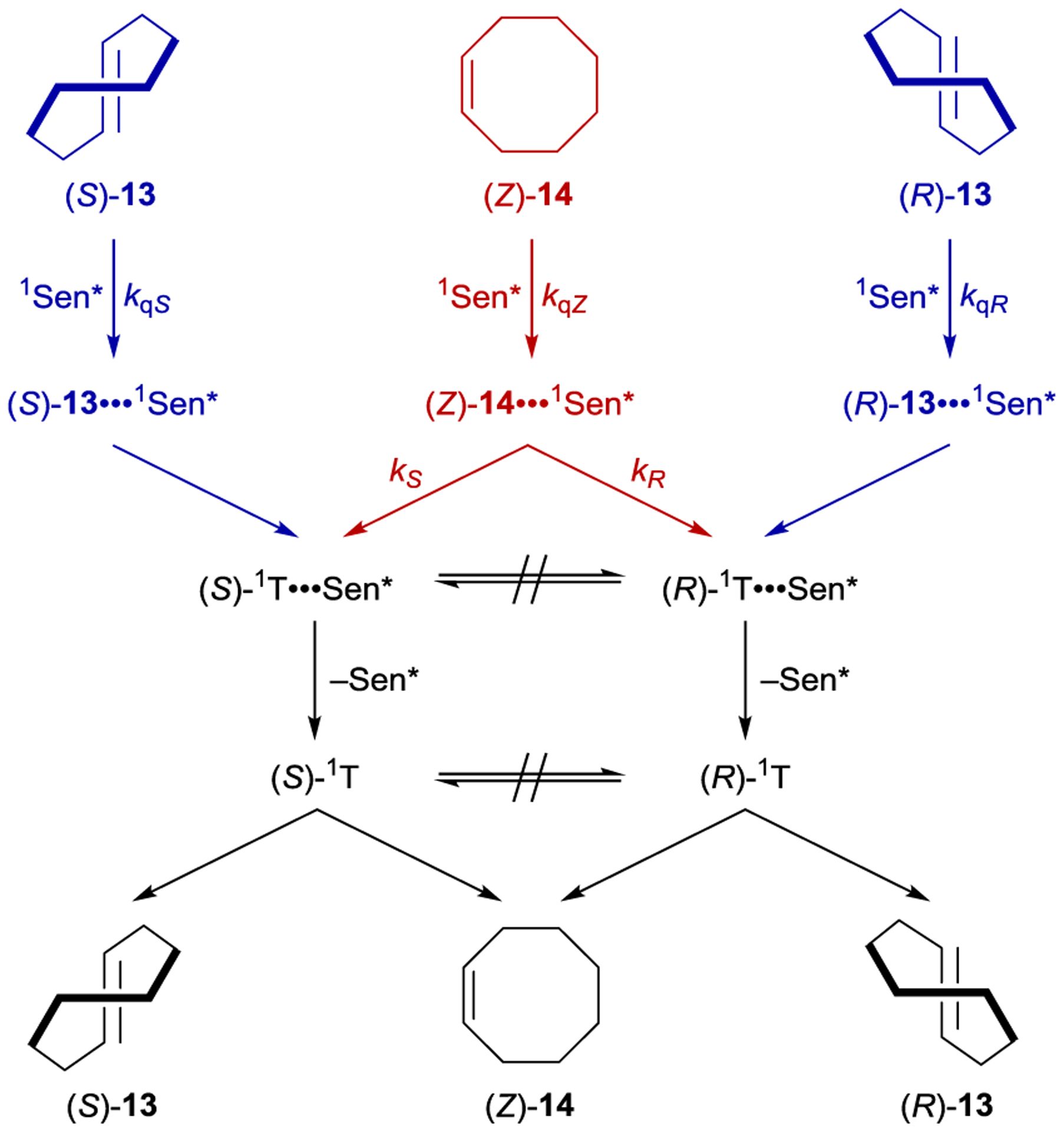

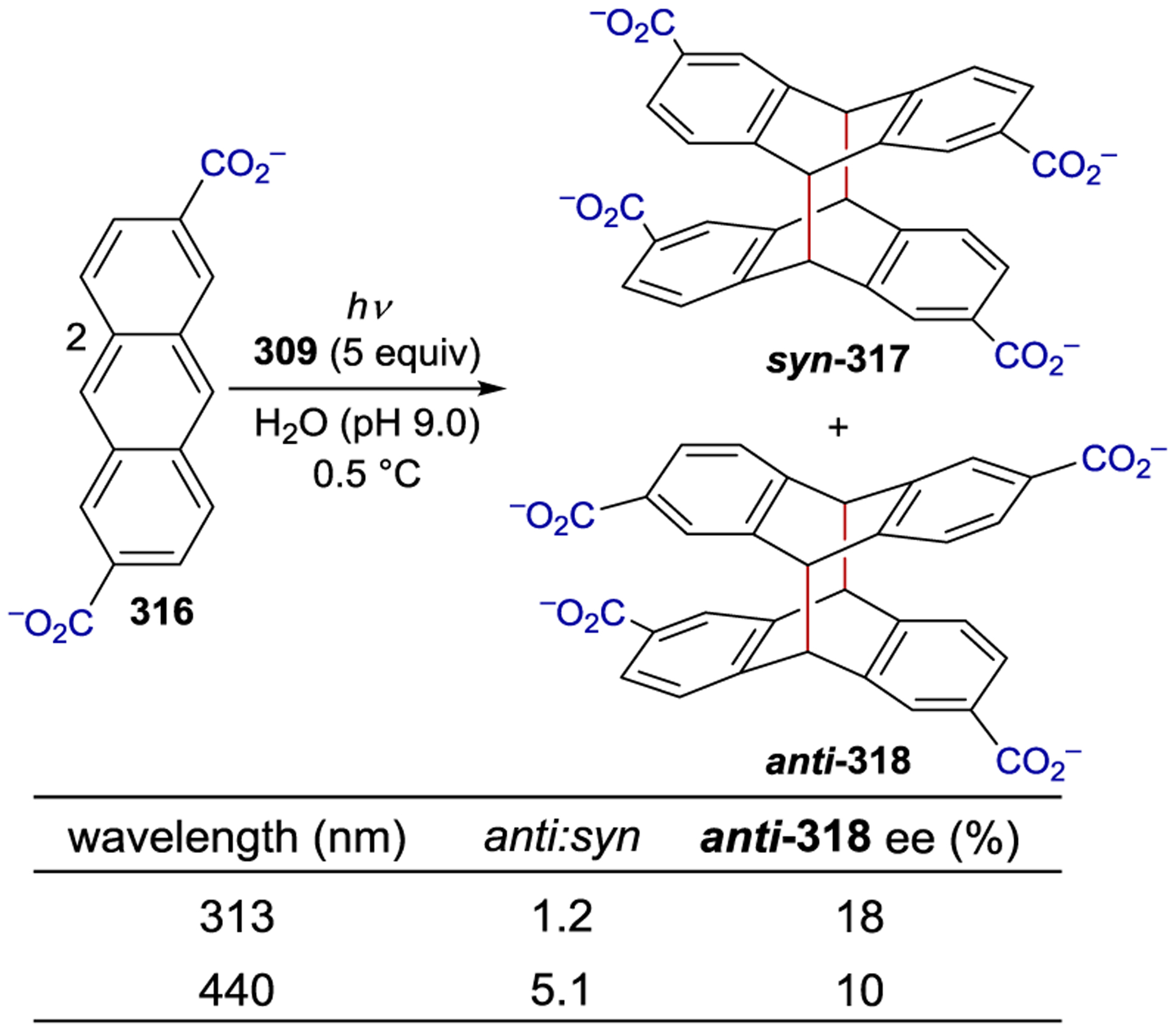

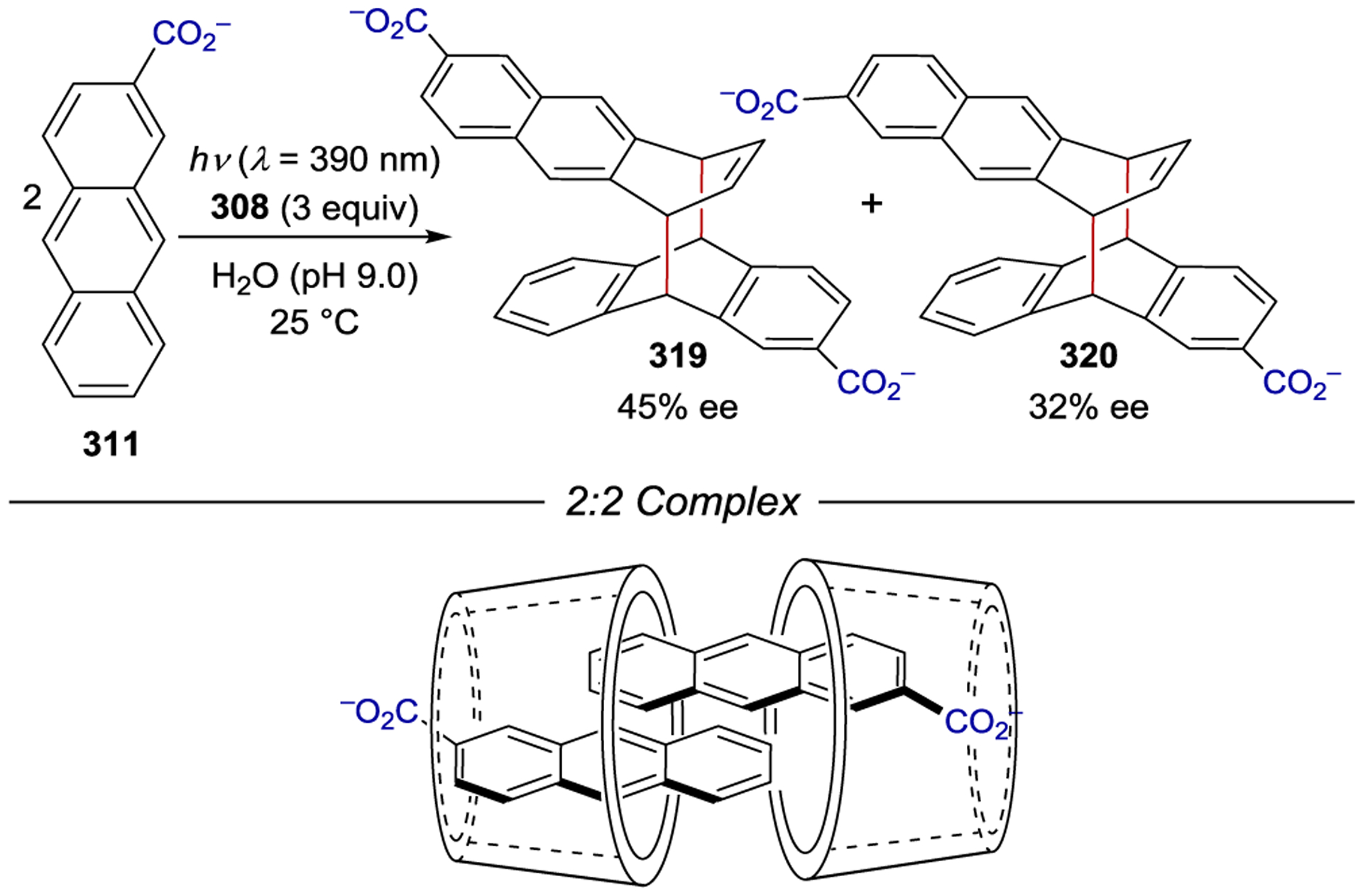

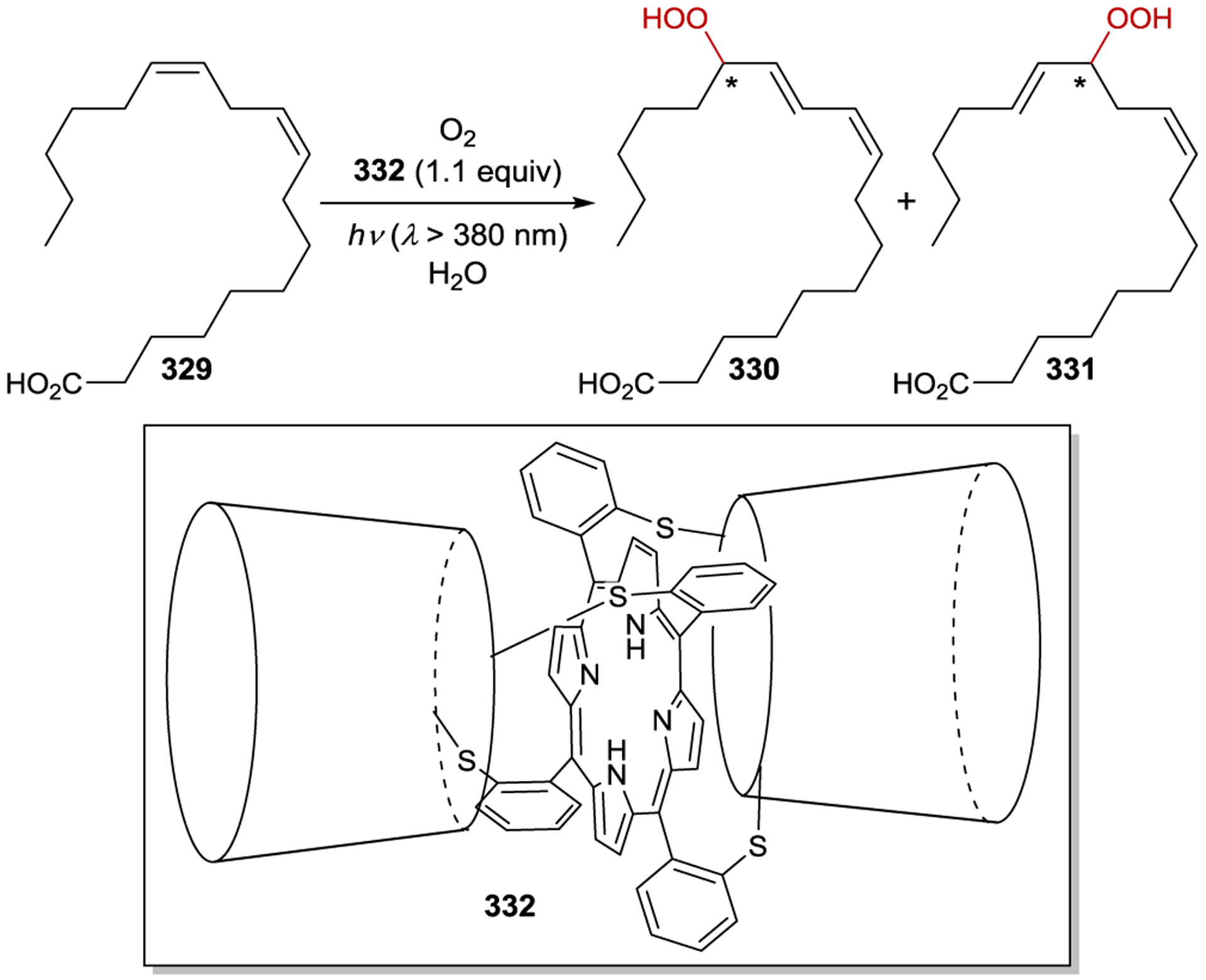

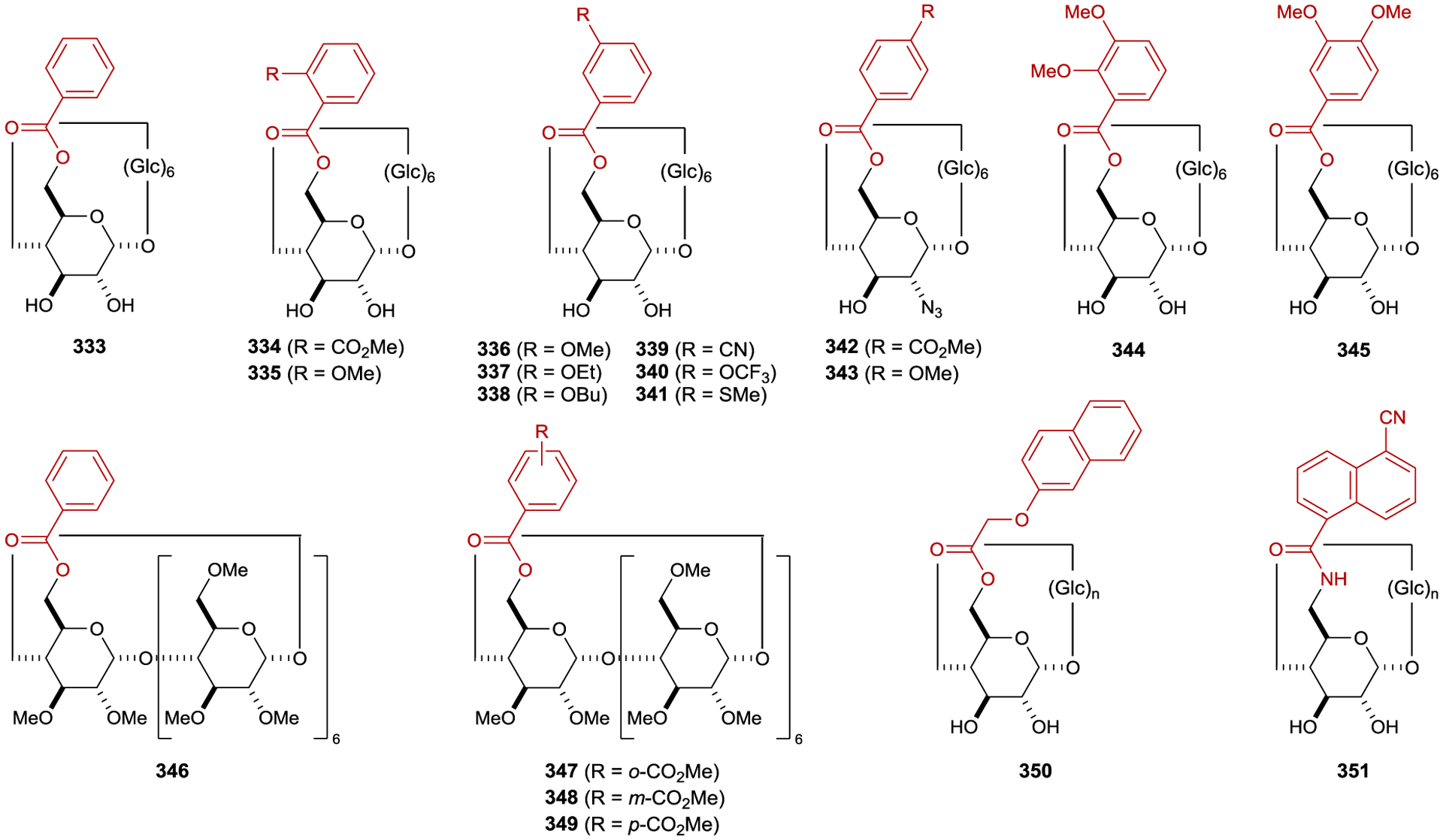

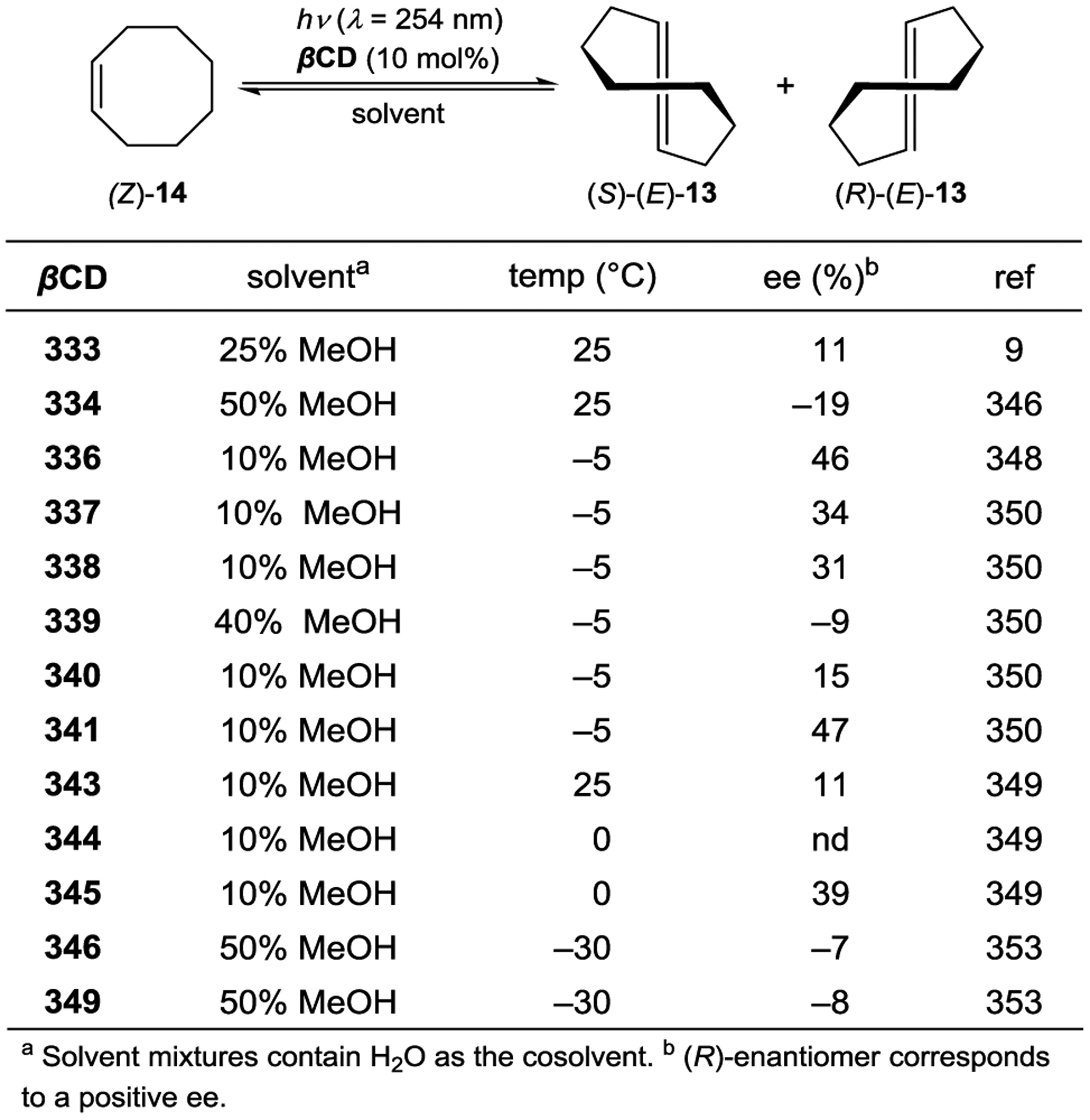

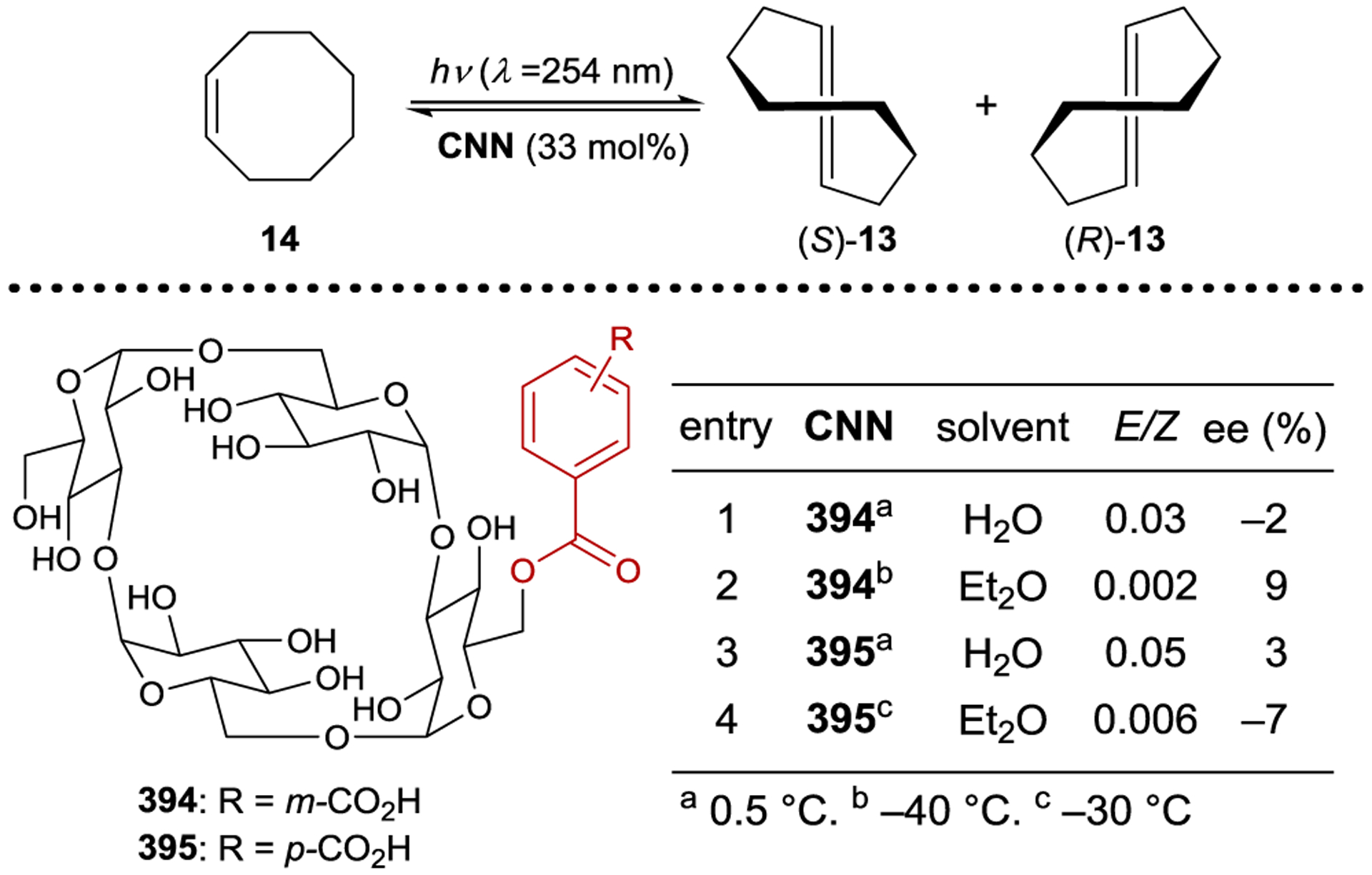

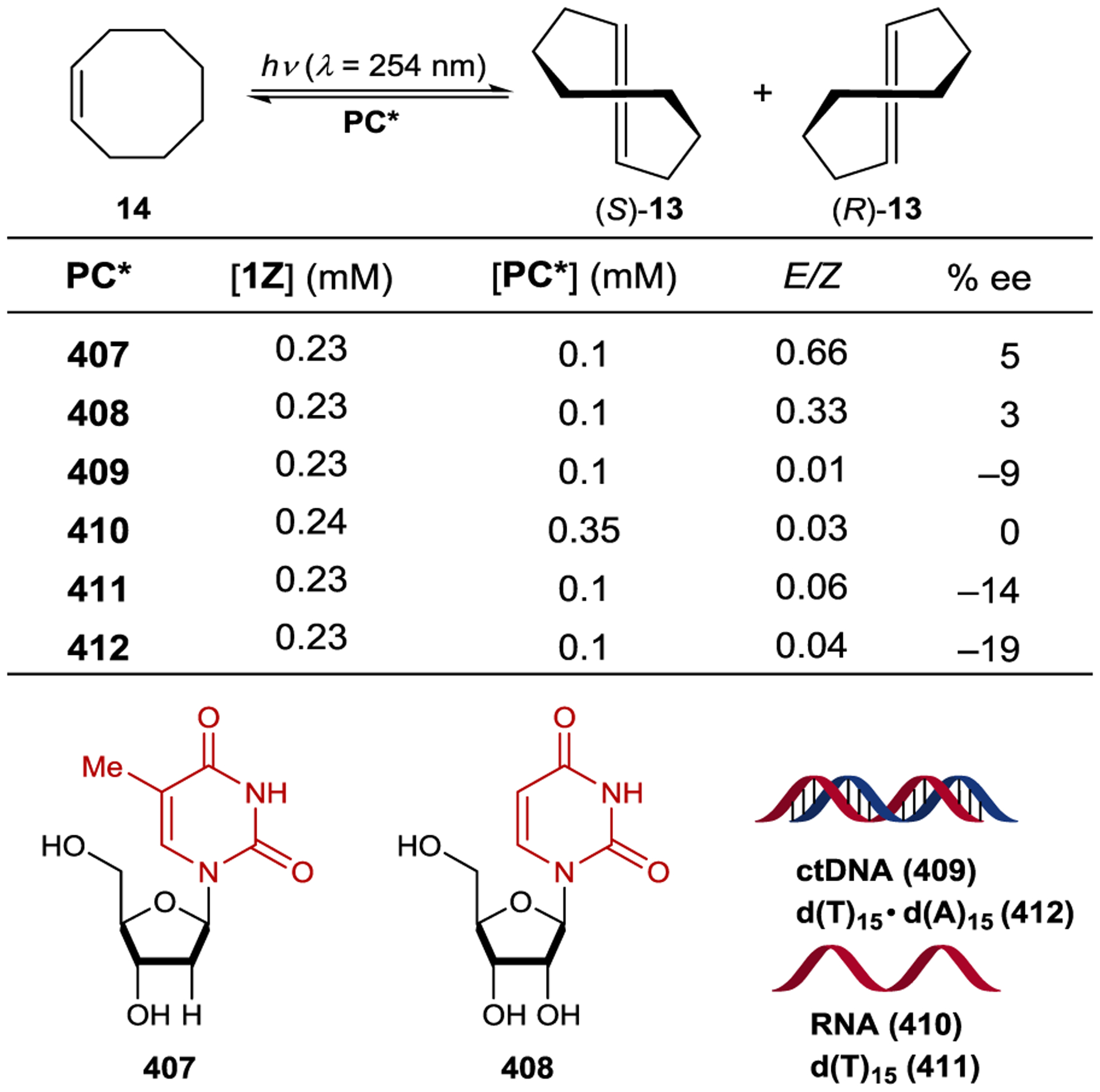

Inoue studied the photochemical isomerization of achiral (Z)-cyclooctene (14) to chiral (E)-cyclooctene (13) using benzenecarboxylates as singlet exciplex sensitizers (Figure 1).44, 45 Initial reports described the production of (E)-cyclooctene in low ee (4% ee), but this process provided the opportunity to study the mechanism of stereoinduction in detail.46, 47 The isomerization proceeds through a singlet exciplex consisting of the excited photocatalyst and cyclooctene (Scheme 7). Rotational relaxation within the initial exciplex produces one of two diastereomeric exciplexes featuring a chiral twisted excited cyclooctene ((S) or (R)-1T). While the exciplex-bound (Z)-cyclooctene may decay to either twisted diastereomeric complex, exciplex-bound (S)- or (R)-cyclooctene decay to the respective (S)- or (R)-1T. After sensitizer dissociation, the excited twisted cyclooctene decays to either (Z)- or (E)-cyclooctene. An enantioselective transformation is achieved as there exists no route for the direct interconversion between the diastereomeric (R)- and (S)-twisted-cyclooctene exciplexes without first reforming (Z)-cyclooctene. Thus, the enantiodetermining step of this process could be either (1) sensitizer quenching by (E)-cyclooctene to form diastereomeric exciplexes (kqS vs. kqR) or (2) stereoselective rotational relaxation from (Z)-cyclooctene to the diastereomeric twisted exciplex intermediates (kS vs. kR). A kinetic resolution of (E)-cyclooctene produced in situ from (Z)-cyclooctene was attempted to distinguish these possibilities. If different sensitizer quenching rates by (E)-cyclooctene dictate enantioselectivity, then an increase in ee over the course of the reaction is expected. On the other hand, if the ee is invariant with time the enantioselectivity is the result of different rates of rotational relaxation from the (Z)-cyclooctene exciplex to the twisted-cyclooctene exciplexes. No change in the ee was observed over the course of the reaction, implying that rotational relaxation of the (Z)-exciplex is the enantiodetermining step.

Figure 1.

Selected Examples of Chiral Benzenecarboxylate Sensitizers

Scheme 7.

Mechanism of Cyclooctene Isomerization Catalyzed by Benzenecarboxylate Sensitizers

The importance of the singlet exciplex for obtaining high levels of enantioselectivity was investigated using benzyl ether sensitizers, which form singlet exciplexes with (Z)-cyclooctene at high substrate concentrations but undergo collisional triplet energy transfer at low substrate concentrations. The ee obtained with the benzyl ethers decreases with decreasing substrate concentration, suggesting that the singlet process is more selective than the triplet. While the catalyst–substrate interaction is long-lived in the singlet exciplex due to the charge-transfer exciplex interaction, the triplet sensitized process likely only involves a fleeting interaction between the catalyst and alkene. Thus, the triplet alkene isomerizes after dissociation from the catalyst, leading to negligible asymmetric induction.48

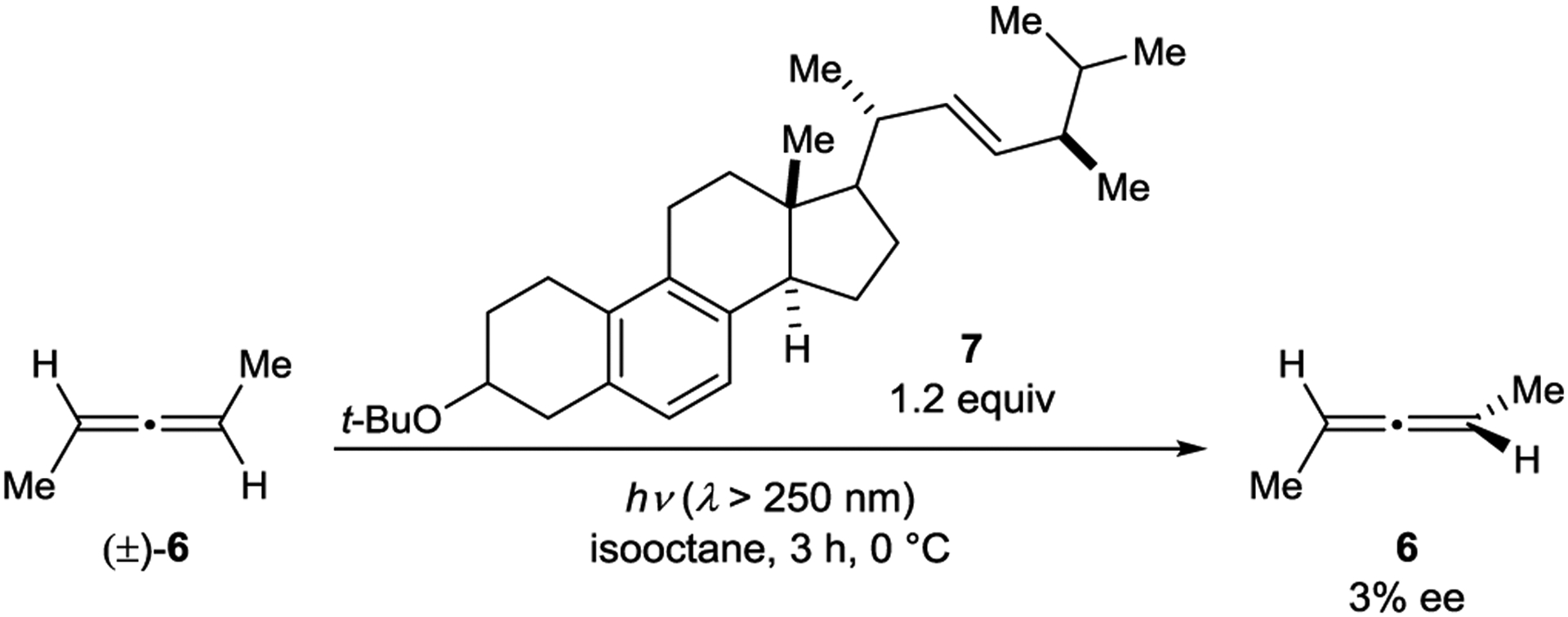

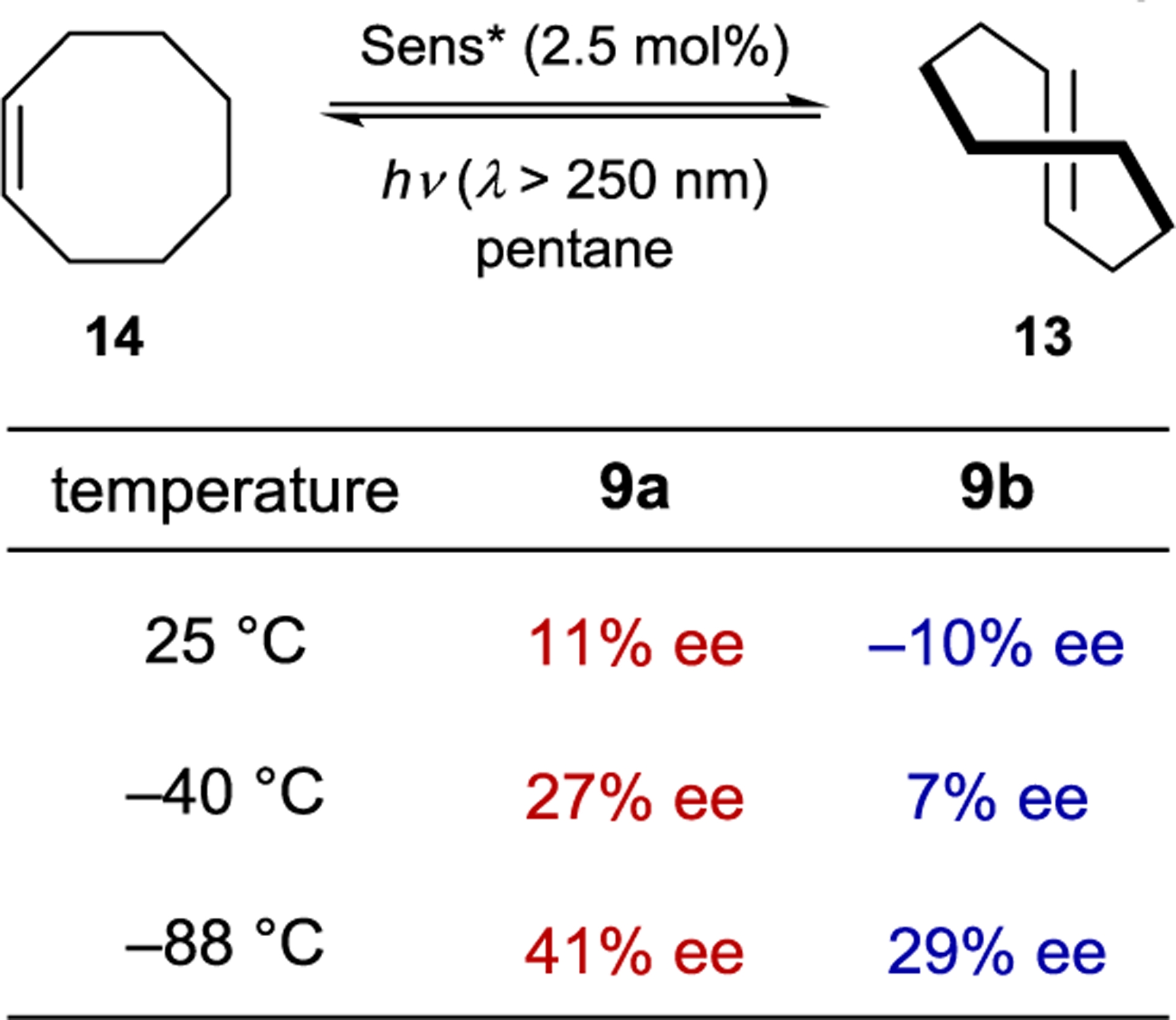

Extensive screening of benzenepolycarboxylate, aromatic amide, and phosphoryl ester sensitizers gave improved enantioselectivity and revealed a surprising relationship between ee and reaction temperature (Scheme 8).49–50 51 52 For bornyl sensitizer 9a, the ee of (E)-cyclooctene increases with decreasing temperature, affording 13 in 41% ee at −88 °C. For menthyl sensitizer 9b, the opposite enantiomer of 13 is favored at 25 °C, but the enantioselectivity decreases with decreasing temperatures, and at −19 °C 13 is formed as a racemate. Below this equipodal temperature, the product chirality inverts, and the ee of the antipodal enantiomer increases with decreasing temperature. This runs contrary to the common assumption that enantioselectivity and temperature should be inversely related, which is an oversimplification of the factors controlling enantioselectivity.

Scheme 8.

Effect of Temperature on Photosensitized Cyclooctene Isomerization

The differential Eyring equation (eq 1) provides a more complete explanation of the temperature-dependent enantioselectivity.53 The differential activation entropy () and enthalpy () for a given reaction are determined by plotting ln(kS/kR) vs. T−1.54 Here, (kS/kR) is the ratio of rate constants leading to the enantiomeric products and can be calculated from the enantiomeric ratio (e.r.). When the entropy and enthalpy terms have opposite signs, they favor formation of the same enantiomer; if their signs are the same, the terms favor opposite enantiomers. Notably, if the differential activation entropy is large and the entropy and enthalpy terms favor opposite enantiomers, which is the case with 9b, the favored enantiomer will switch with a change in temperature.

| eq. 1 |

For cyclooctene photoisomerization catalyzed by 9b, the differential thermodynamic terms are kcal mol−1 and cal mol−1 K−1. Therefore, at low temperatures, the enthalpy term dominates, favoring (S)-cyclooctene, while at higher temperatures the entropy term dominates, favoring (R)-cyclooctene. Further studies showed that the temperature-switching phenomenon is characteristic of ortho-benzencarboxylates, and an extensive screening of these sensitizers showed 9c to be optimal, giving 64% ee at −89 °C.55, 56

Pressure can also be used as an entropy-related tool to control enantioselectivity.57, 58 The pressure dependence of a reaction at constant temperature is given by eq 2:

| eq. 2 |

where is the difference in activation volume between the diastereomeric transition states. Using eq 2, Inoue determined for a variety of sensitizers.59, 60 In general, ortho-benzenecarboxylates show the greatest pressure dependence on enantioselectivity, and several instances where the product chirality switches as a function of pressure were reported. With 9b, (R)-cyclooctene was obtained in 11% ee at atmospheric pressure, while (S)-cyclooctene was obtained in 18% ee at 400 MPa. For most of the sensitizers examined, the pressure effect becomes discontinuous above 200–400 MPa, suggesting a change in mechanism of the isomerization.61 There is no observed correlation between and , implying that both temperature and pressure can be optimized independently for high enantioselectivity. The optimal conditions were predicted by mathematically modeling as a function of P and T−1. In theory, the maximum of the fitted three-dimensional plot corresponds to the pressure and temperature that should provide the highest ee.59

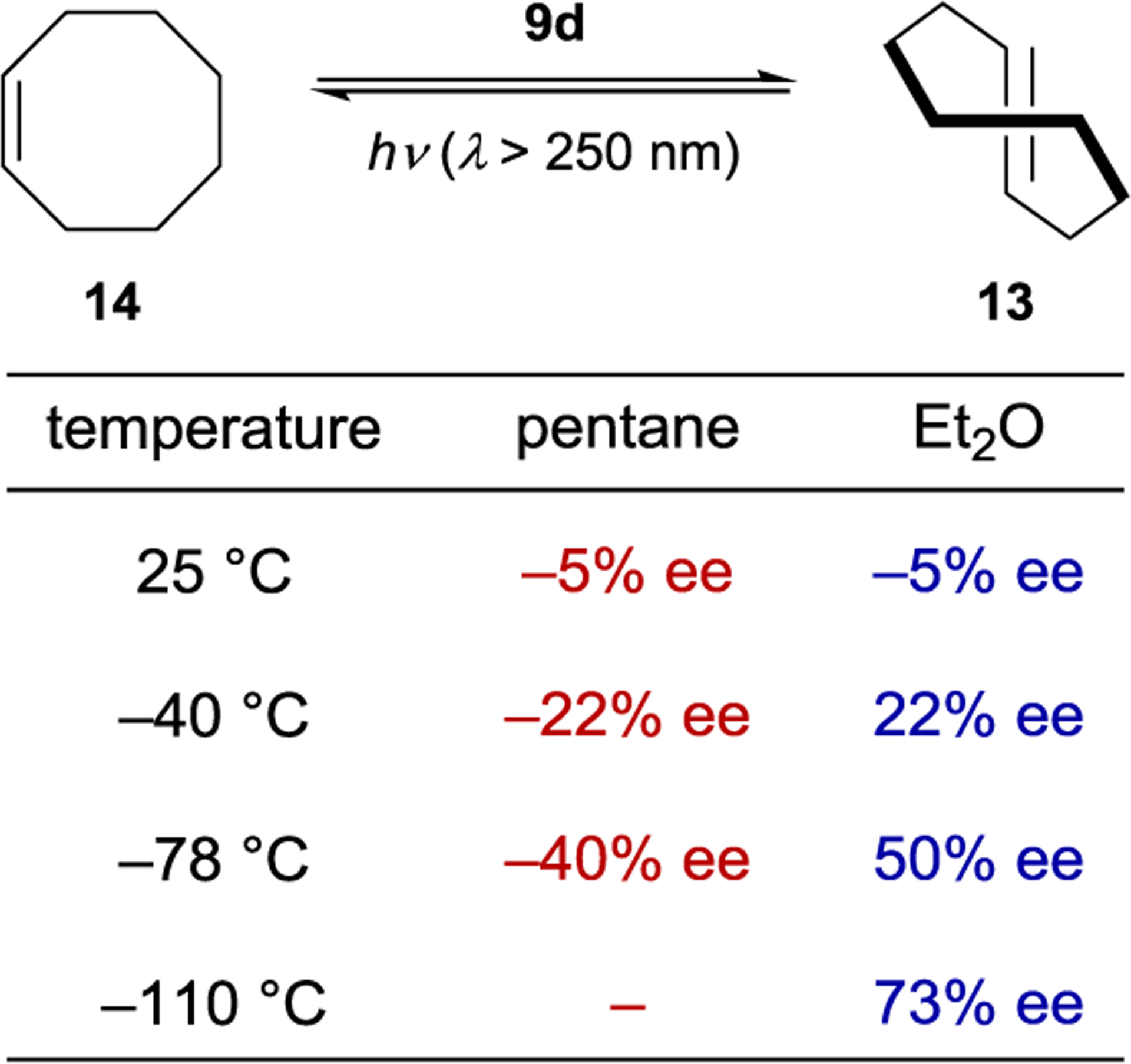

The enantioselectivity of the reaction is relatively insensitive to solvent for most sensitizers; however, an unusual relationship was observed using saccharide sensitizer 9d (Scheme 9).62 The isomerization was conducted in pentane and diethyl ether at several temperatures between −110 °C and 25 °C. At 25 °C, (R)-cyclooctene is formed in approximately 5% ee in both solvents. In pentane, the ee increases with decreasing temperatures, reaching 40% at −78 °C. On the other hand, the chirality inverts in diethyl ether with an equipodal point at −19 °C, ultimately reaching 73% ee for (S)-cyclooctene at −110 °C. These results can be rationalized by the signs of the differential activation entropy and enthalpy, which for pentane are both positive, while for diethyl ether are both negative. The switching of product chirality as a function of solvent was attributed to the solvation of the ether groups of the saccharide esters. Given the solvent effect on enantioselectivity, the reaction was also conducted in supercritical carbon dioxide because the solvent properties can be dramatically tuned within a relatively narrow range of pressure and temperature near the critical density. The differential activation volume was determined from eq 2; however, the relationship between ln(kS/kR) and pressure is not linear over the measured pressure range, suggesting that different values exist in the near-critical and high-pressure regions.63 Together, these results demonstrate how mechanistic understanding can be used to tune catalyst structure in combination with reaction conditions to optimize the enantioselectivity of a photocatalytic reaction.

Scheme 9.

Effect of Solvent on Photosensitized Cyclooctene Isomerization

Using the same class of benzenepolycarboxylate sensitizers, several other cyclic alkenes were subjected to the photoisomerization conditions. In the case of (Z)-1-methylcyclooctene, the ee does not exceed 7%.64, 65 Compared to (Z)-cyclooctene, the E/Z ratio at the photostationary state (PSS) is low, which was attributed to greater steric destabilization in the exciplex. The E/Z ratios could be improved by tethering the sensitizers to the substrate in a diastereodifferentiating isomerization.66–67 68 (Z,Z)-1,3-Cyclooctadiene undergoes photoinduced isomerization to the E,Z-isomer in 18% ee using 10b;69 however, the photoisomerization of 1,5-cyclooctadiene provides only 5% ee.70 The latter reaction is pressure-dependent, favoring (−)-(E,Z)-1,5-cyclooctadiene in 4% ee at atmospheric pressure and (+)-(E,Z)-1,5-cyclooctadiene in 4% ee at 300 MPa.61

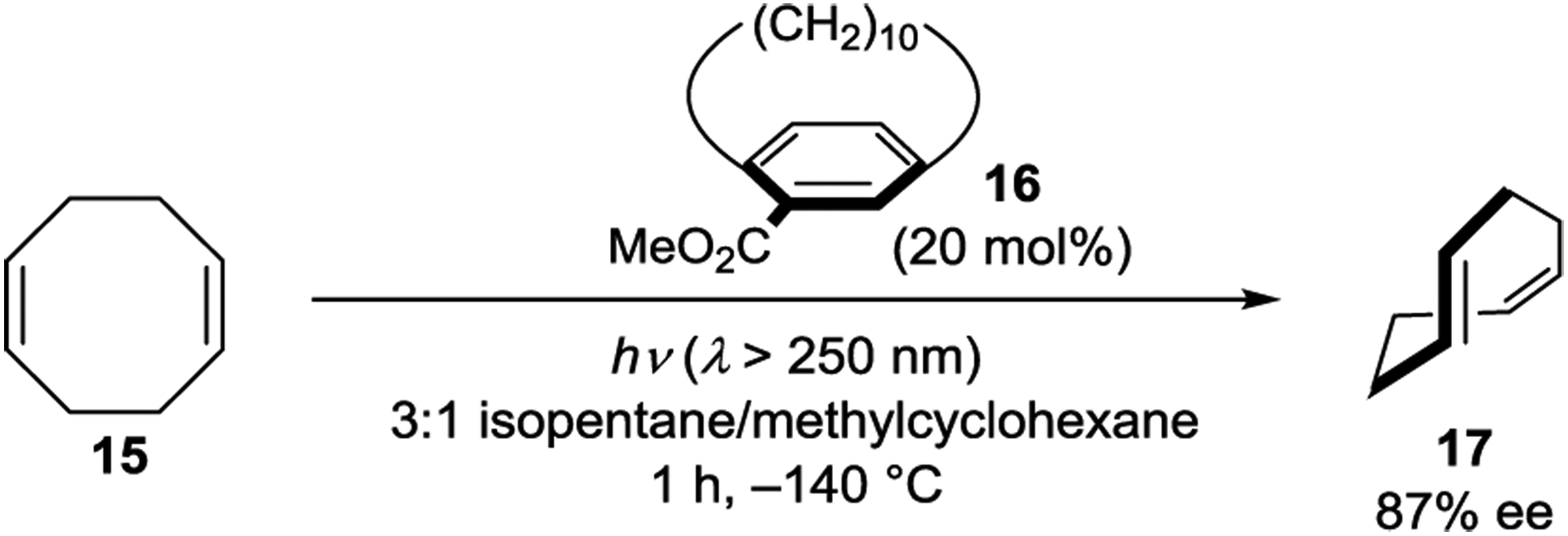

Inoue also examined planar–chiral paracyclophanes as exciplex-forming sensitizers in the photoisomerization of cyclooctenes (Scheme 10).71 Using sensitizer 16, the isomerization proceeded to give photostationary E/Z ratios of approximately 0.01, which is smaller than observed with simpler arenecarboxylate sensitizers (0.1–0.4). The authors hypothesized that steric hindrance in the exciplex of (E,Z)-17 compared to (Z,Z)-15 with the bulkier paracyclophane accounts for the lower E/Z ratios. Spectroscopic experiments showed that (Z,Z)-15 efficiently quenched sensitizer 16 with exciplex formation confirmed by the appearance of a new emission feature. The enantioselectivity increased with decreasing temperatures, affording (E,Z)-17 in 87% ee at −140 °C.

Scheme 10.

Cyclooctadiene Isomerization Catalyzed by a Cyclophane Sensitizer

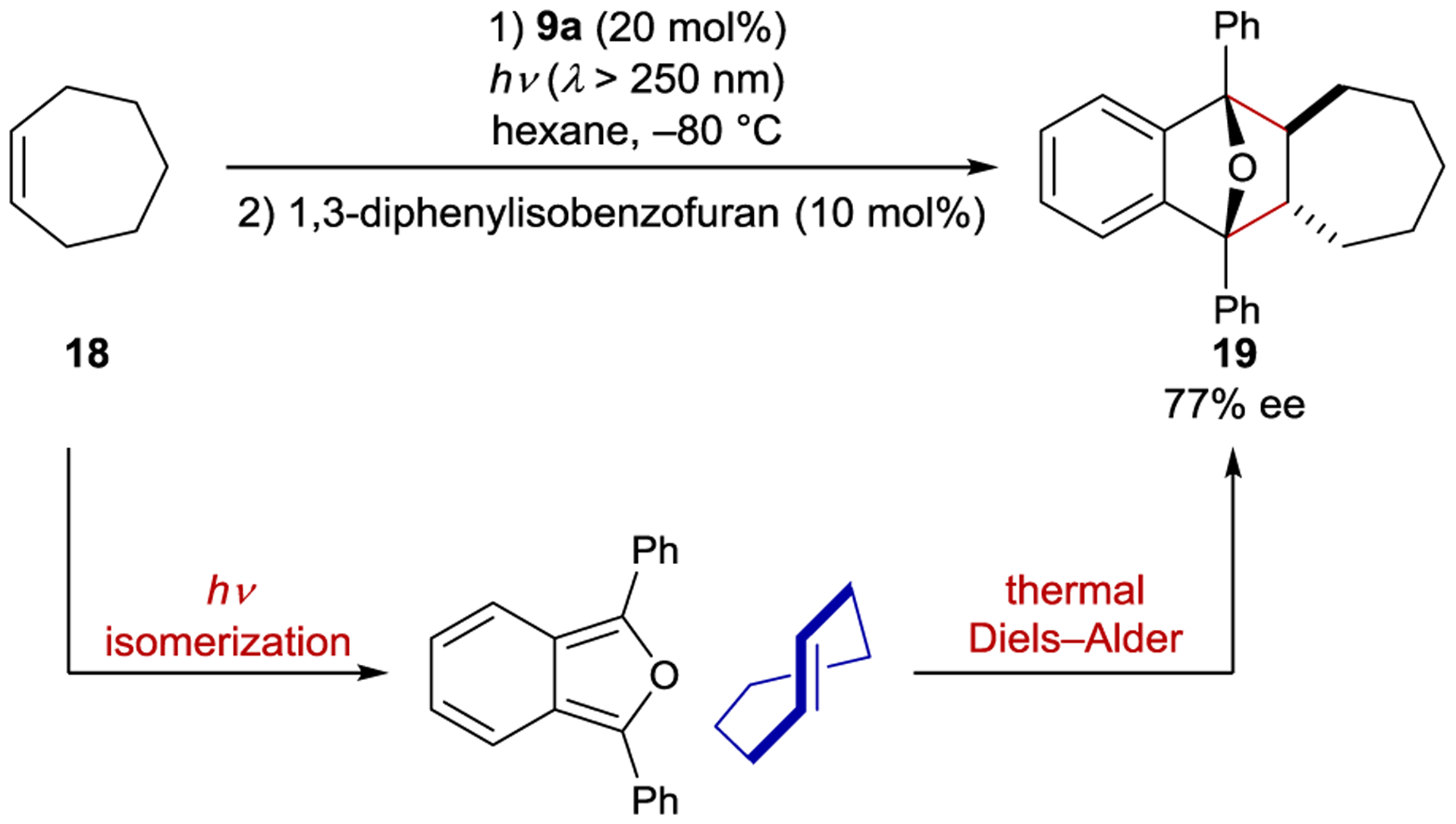

Cycloheptene (18) can also be photochemically isomerized using chiral arene sensitizers; however, due to the thermal instability of (E)-cycloheptene, the enantioselectivity was assessed by trapping with 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran in a stereospecific Diels–Alder cycloaddition (Scheme 11).72 The best enantioselectivity (77% ee) was obtained with 9a in hexane at −80 °C. With most sensitizers, the ee was greater for (E)-cycloheptene than (E)-cyclooctene. This trend was reflected in the calculated and values, which are typically greater by a factor of 2–3 for cycloheptene than for cyclooctene. The authors concluded that the approach of cycloheptene to the photocatalyst is less hindered, enabling a more intimate interaction in the exciplex and consequently greater stereocontrol.

Scheme 11.

Cycloheptene Isomerization and Cycloaddition Catalyzed by Benzenecarboxylate Sensitizers

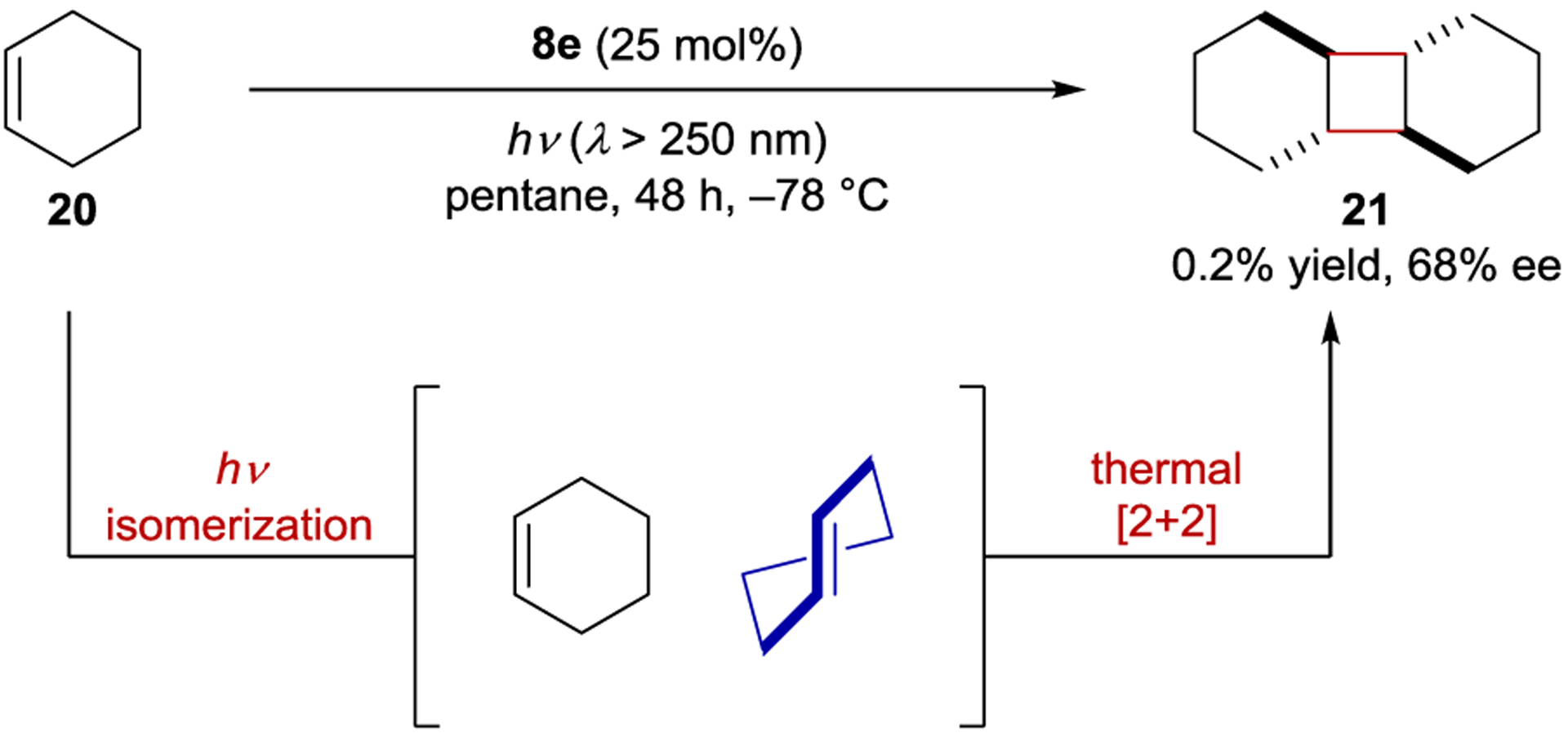

Under similar photoisomerization conditions, (Z)-cyclohexene (20) forms a mixture of [2+2]-cyclodimer diastereomers via initial photochemical isomerization to the (E)-isomer followed by thermal cycloaddition (Scheme 12).73 The cycloaddition may occur by two mechanisms: a concerted, stereospecific dimerization, or a stepwise stereoablative radical dimerization. The plot of ln(kS/kR) vs. T−1 is not linear at high temperatures, which was attributed to the contribution of the stepwise mechanism. At low temperatures, however, the relationship is linear. At −78 °C, the trans-anti-trans isomer (21) is obtained in 68% ee using sensitizer 8e. Photochemically produced (E)-cyclohexene also reacts with 1,3-cyclohexadiene in a thermal [4+2] cycloaddition. Complex mixtures of dimeric products are formed, and only the exo-[4+2] product is obtained in appreciable ee (8%).74

Scheme 12.

Cyclohexene Isomerization and Cycloaddition Catalyzed by Benzenecarboxylate Sensitizers

With the insights gained from the studies of cyclic alkene isomerization discussed above, Inoue revisited the asymmetric isomerization of 1,2-diarylcyclopropanes originally reported by Hammond.27 Several arenecarboxylate sensitizers were tested, but the highest reported ee for trans-1 was 10%.75–76 77

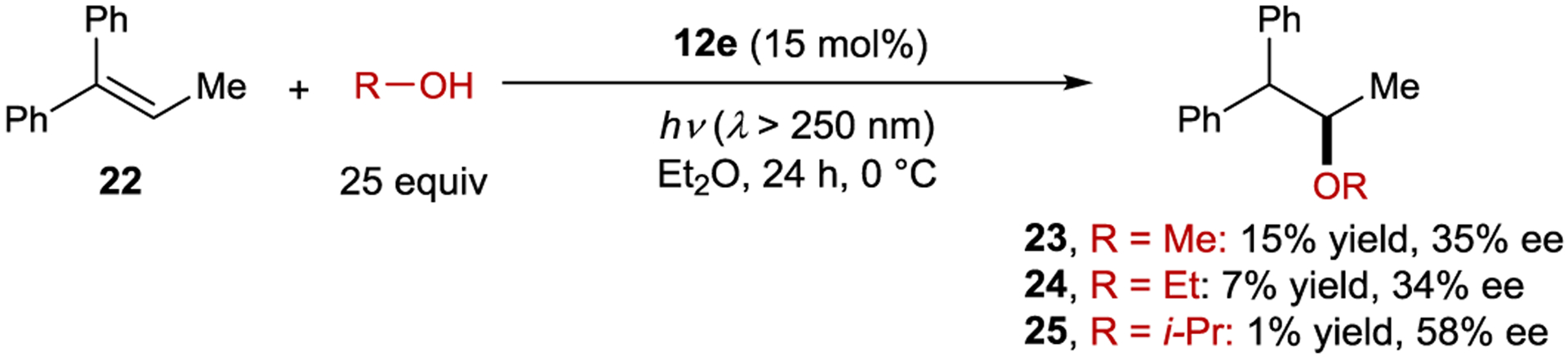

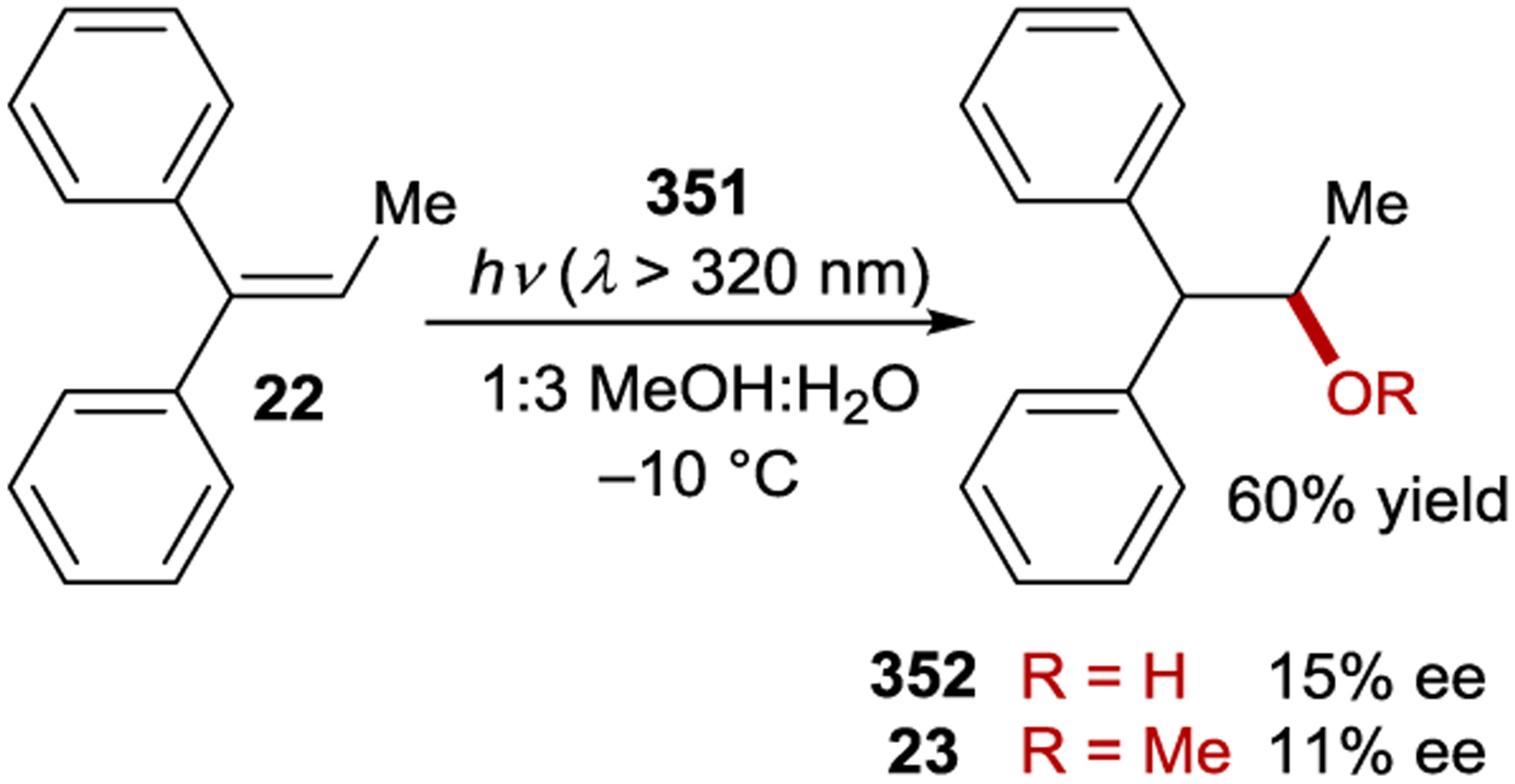

Bimolecular photoreactions are particularly difficult to control through an exciplex mechanism because the enantiodetermining step must occur in a ternary complex comprising the sensitizer and both substrates. This requirement can be satisfied by the attack of a reactant on a substrate–catalyst exciplex. Because the exciplex possesses a significant degree of charge transfer, it is often essential to conduct the reaction in nonpolar solvents to avoid dissociation into a solvent-separated radical-ion pair from which any subsequent reaction is likely to be racemic. This is problematic for electron-transfer reactions, which are slow under these conditions. Hence, it can be challenging to obtain both good yield and high ee simultaneously. This was the case in a [2+2] cycloaddition of electron-rich styrenes reported by Inoue.78 While the reaction catalyzed by 9b proceeded to high yield in CH3CN, the negligible enantioselectivity observed was likely due to racemic reactivity from the free styrene radical cation. In pentane and ether, which both favor exciplex formation, no product was observed.

A similar effect was observed in the anti-Markovnikov photoaddition of methanol to 1,1-diphenylpropene (22). Here, nonpolar solvents give the ether product in low yield (< 10%) and high ee (up to 27%), while polar solvents afford the product in high yield (up to 60%) and low ee (< 1%).79 As a potential solution to this problem, saccharide esters of napthalenecarboxylic acids (11d, 11e, and 12e) were used as sensitizers.80 The authors proposed that these sensitizers provide microenvironmental polarity control where the saccharide moiety creates a high-polarity region in the direct vicinity of the sensitizer, allowing for electron transfer, within a low-polarity bulk solution, ensuring that the sensitizer and substrate do not dissociate. Using these sensitizers, high enantioselectivity is maintained, while the yield is improved to 20–40%. Less hindered alcohols generally give higher yields but lower enantioselectivity (Scheme 13). The best ee (58%) was achieved with sensitizer 12e using i-PrOH as the nucleophile, but the yield was only 1%.81 Based on computational and fluorescence quenching studies, the authors proposed that the difference in free energy between the diastereomeric sensitizer–substrate exciplexes is the primary determinant for enantioselectivity. The temperature and pressure effects on the reaction were evaluated, and similar effects were observed as with the cyclooctene isomerization.82–83 84 85 86 When the reaction is conducted in supercritical carbon dioxide, there is a sudden increase in the product ee when transitioning from the near-critical to supercritical state, indicating a substantial difference in solvent environment in this pressure region. At the critical state, there is significant solvent clustering, where the local density of CO2 is greater around the exciplex than in the bulk solution. Further, the solvent environments for the diastereomeric exciplexes can be significantly different due to this clustering, increasing the difference in free energy. In a related intramolecular photoaddition of a tethered alcohol, this clustering behavior was manipulated by adding cosolvents to reactions conducted in supercritical CO2. When ether was added to tune the cluster polarity, the ee increased from 30% to 45%.87–88 89

Scheme 13.

Polar Photoaddition of Alcohols to Alkenes Catalyzed by Naphthalenecarboxylate Sensitizers

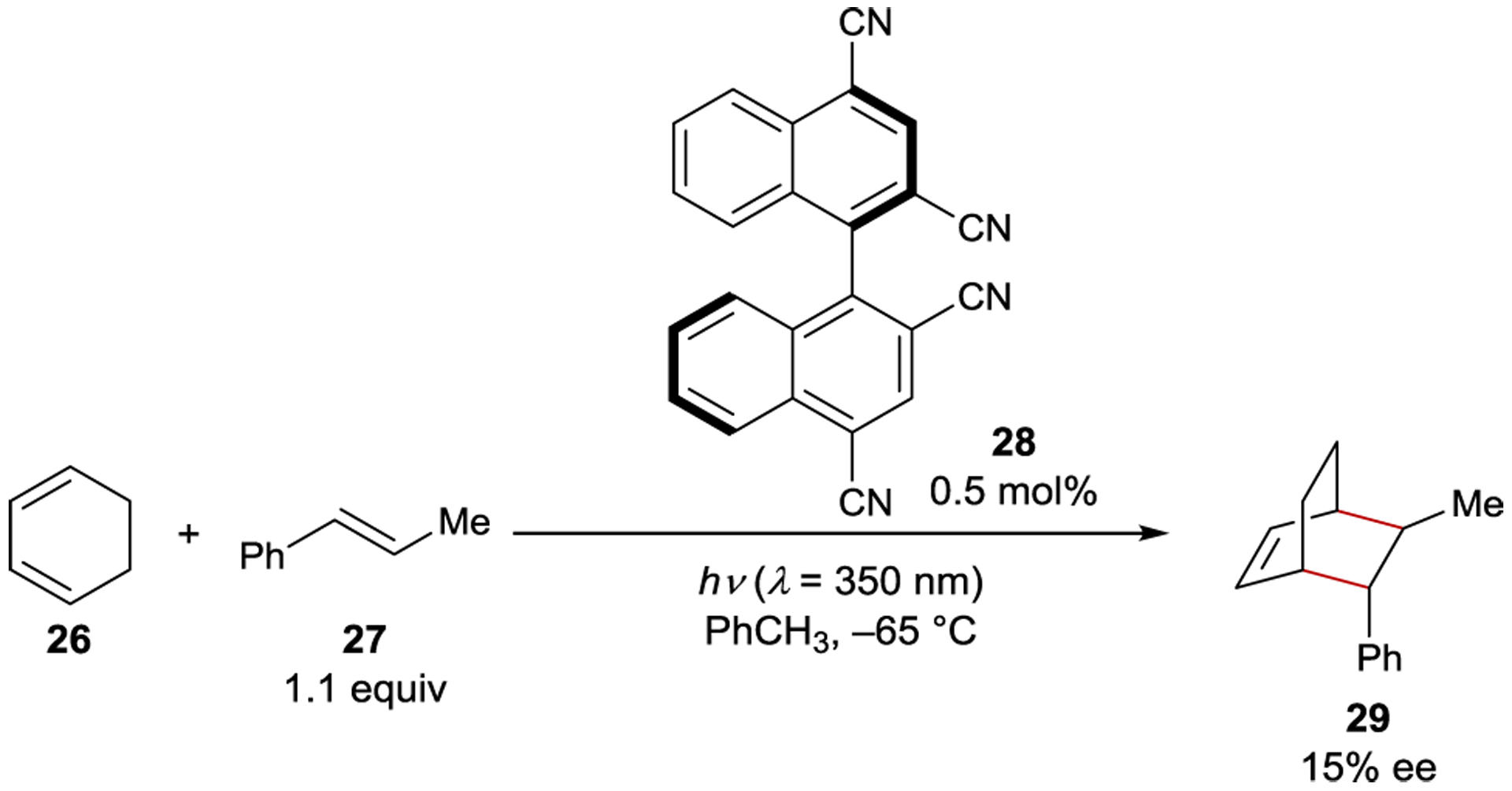

Schuster reported an enantioselective [4+2] photocycloaddition catalyzed by axially chiral cyanoarene sensitizer 28 (Scheme 14).90 The discovery built on prior work showing that electron-deficient photocatalysts promote radical cation Diels–Alder reactions between electron-rich dienes and dienophiles in polar solvents.91–92 93 While the racemic [4+2] product is formed when 26 and 27 are sensitized with 28 in MeCN, the cycloadduct 29 is formed in 15% ee in toluene.94 Transient absorption experiments suggest that electron-transfer quenching of the excited sensitizer in polar solvents produces a radical-ion pair, while an exciplex forms in nonpolar solvents. The existence of the exciplex was corroborated by a new fluorescence feature when the singlet excited-state photocatalyst is quenched by styrene. At low temperature, two discrete, diastereomeric catalyst–styrene exciplexes were detected using time-resolved fluorescence experiments. Addition of cyclohexadiene resulted in further quenching of the exciplex fluorescence, leading the authors to propose the formation of a ternary excited-state complex, or triplex, comprised of the sensitizer, diene, and dienophile. The enantioselectivity in this reaction was attributed to a difference in excited-state lifetimes for the two diastereomeric catalyst-styrene exciplexes.

Scheme 14.

Diels–Alder Cycloaddition Catalyzed by a Cyanoarene Sensitizer

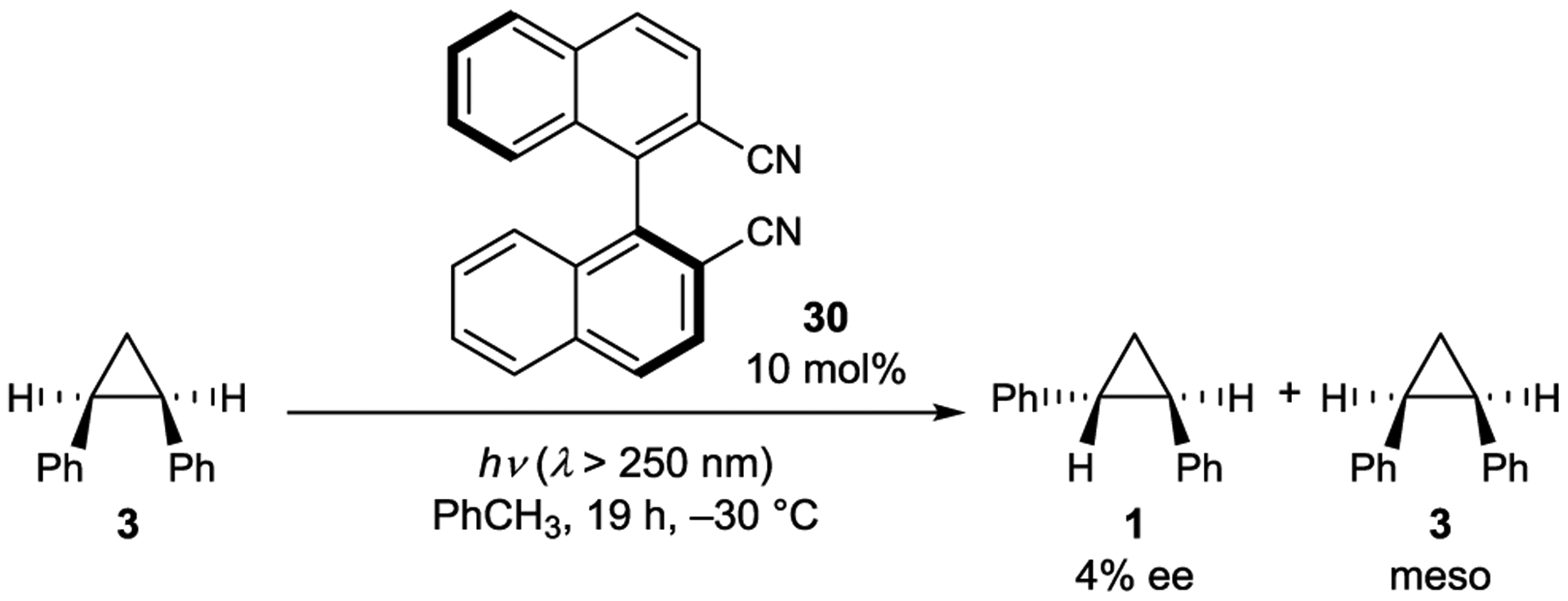

Mattay showed that a similar electron-deficient sensitizer (30) also catalyzes the enantioselective cis-trans isomerization of cyclopropanes (Scheme 15).95, 96 Mechanistic experiments performed with radical cation quencher 1,2,4-trimethoxybenzene showed solvent-dependent reactivity analogous to that observed by Schuster. In toluene, in which an exciplex is formed, enantioenriched trans-1 is obtained in 4% ee. Racemic product is obtained in MeCN, suggesting the existence of an electron-transfer mechanism that produces solvent-separated radical-ion pairs.

Scheme 15.

Cyclopropane Isomerization Catalyzed by a Cyanoarene Sensitizer

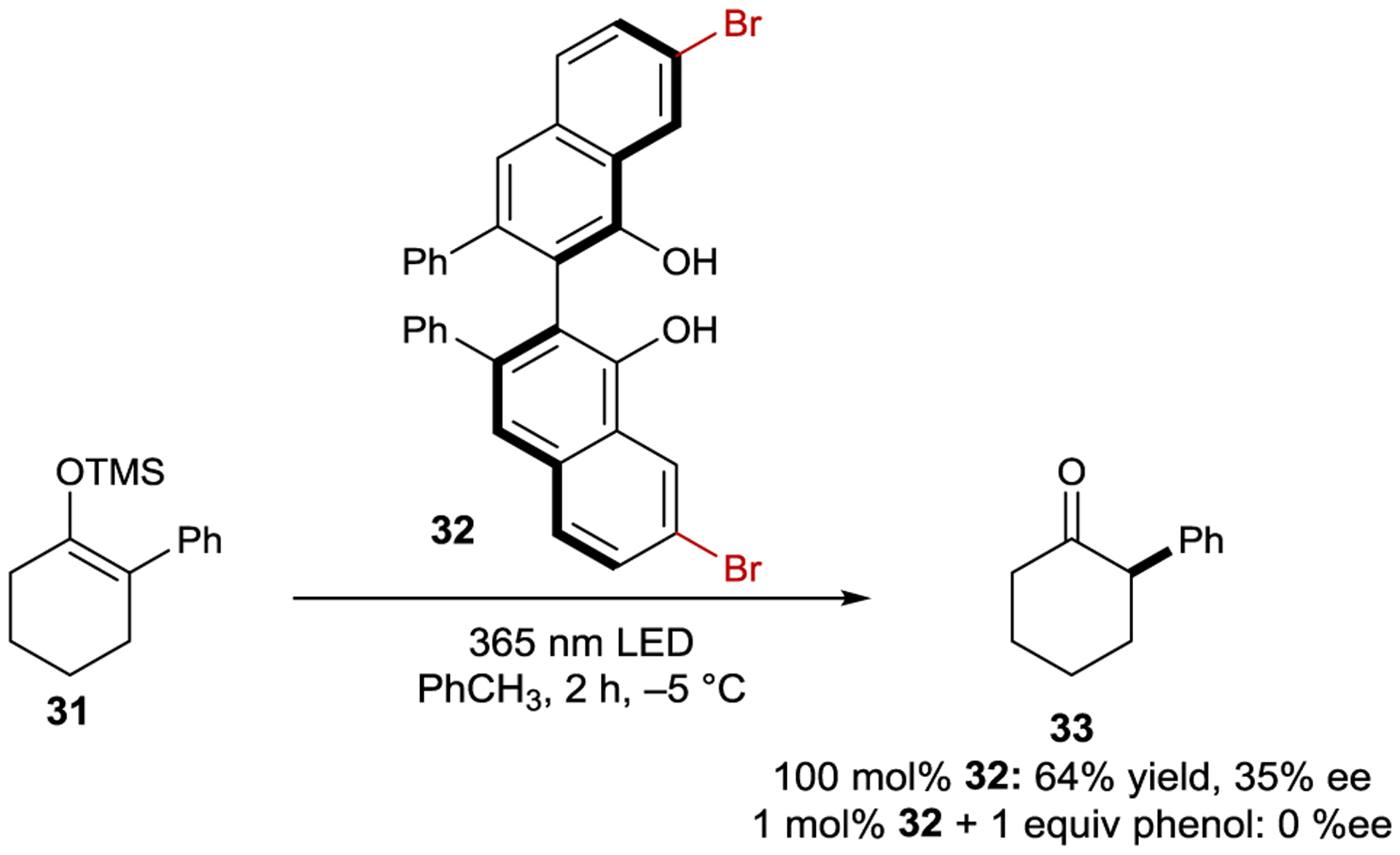

Hanson studied axially chiral VANOL-derived catalysts as excited-state proton-transfer reagents for the stereoselective protonation of silyl enol ethers (Scheme 16).97 The shift of electron density upon excitation of the chromophore increases the acidity of the hydroxyl protons, enabling a protonation event that would be thermodynamically unfavorable in the ground state.98 Stoichiometric loadings of 32 afford ketone 33 in 64% yield and 35% ee. The presence of a bromine substituent on the arene backbone is necessary for productive reactivity, which was attributed to its ability to facilitate intersystem crossing. When only 1 mol% of 32 is used with one equiv of phenol as a sacrificial proton source, racemic product is formed. The authors hypothesized that the loss of enantioselectivity is due to excited-state proton transfer from 32 to phenol to create PhOH2+, which then protonates the substrate.

Scheme 16.

Excited-State Protonation Catalyzed by a VANOL-derived Sensitizer

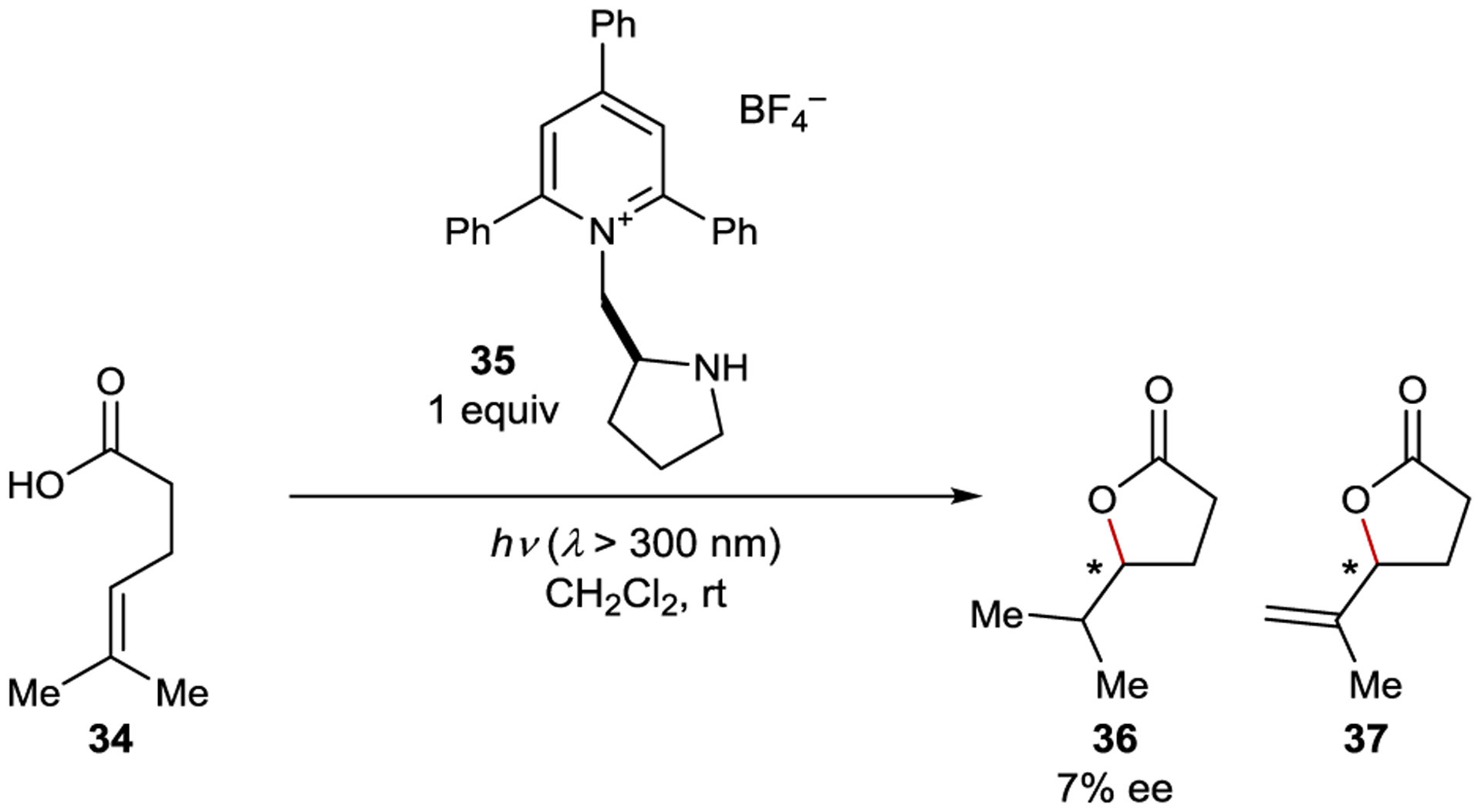

Sabater studied chiral pyridinium photoredox catalysts for the cyclization of 34 to afford a mixture of saturated lactone 36 and unsaturated lactone 37 (Scheme 17). Optimal results were achieved with sensitizer 35, which gave 7% ee for 36.99 The reaction proceeds through photoinduced electron transfer (PET) oxidation of the alkene to the radical cation, followed by enantiodetermining nucleophilic attack of the pendant alcohol.

Scheme 17.

Polar Photoaddition Catalyzed by an Acridinium Sensitizer

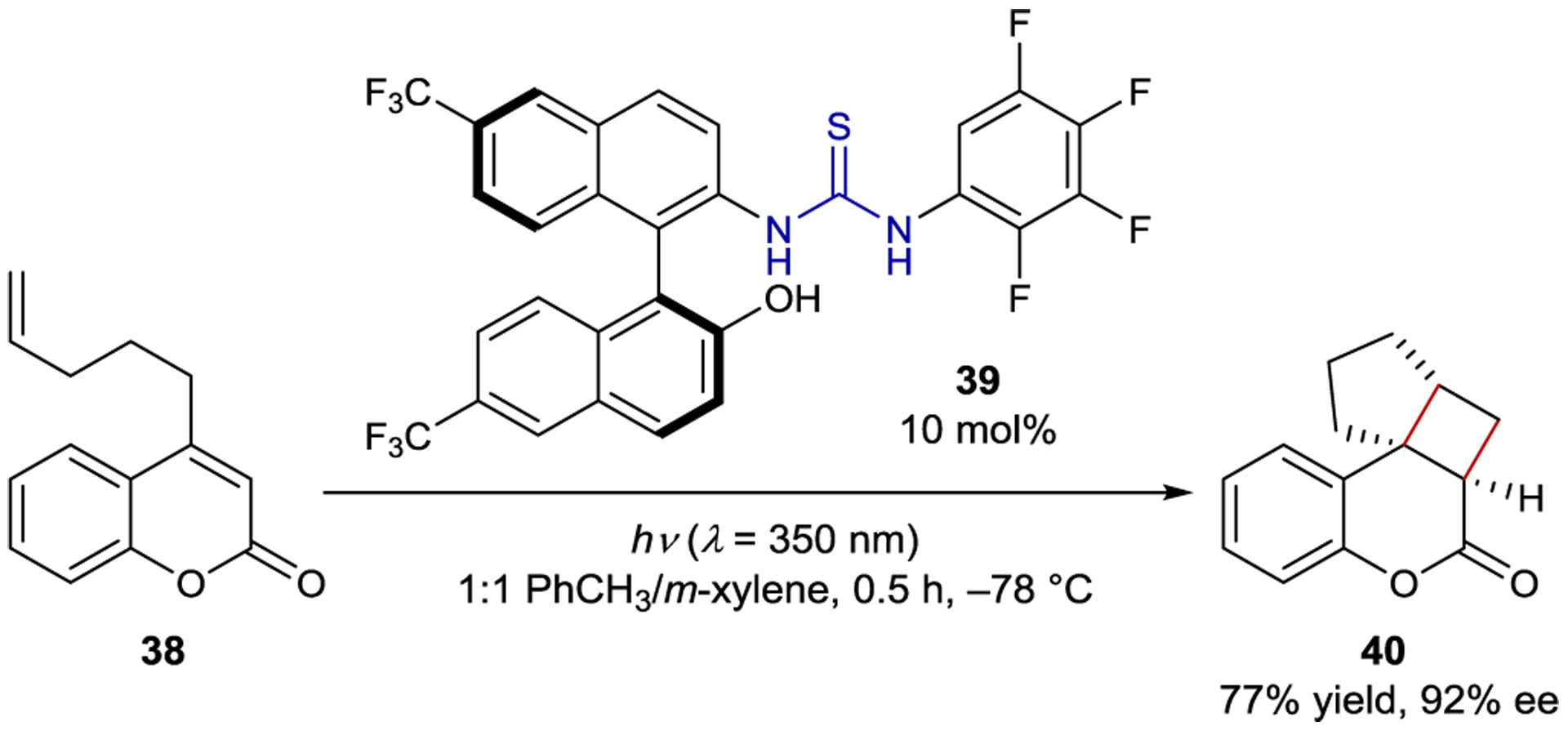

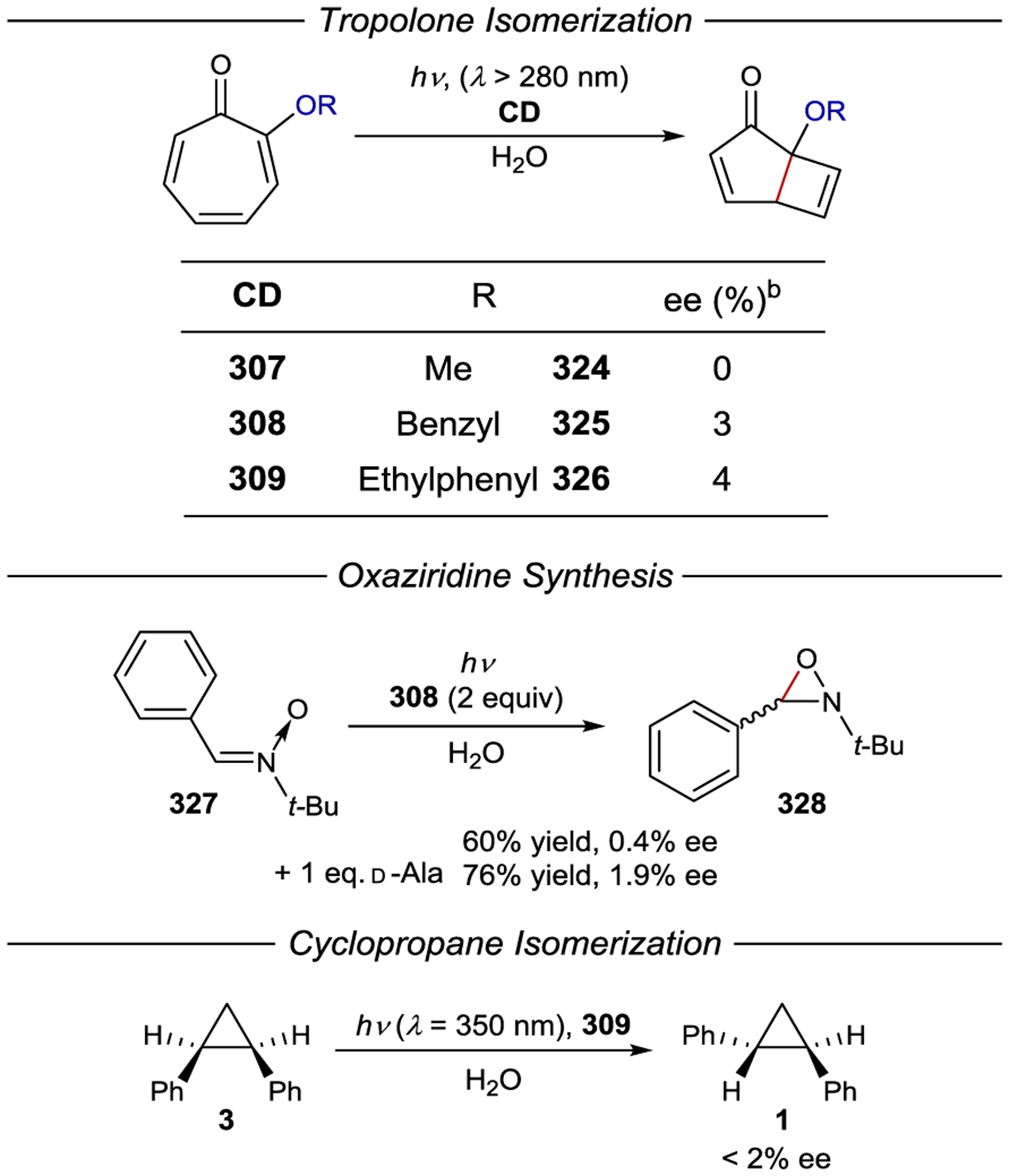

Sivaguru, Sibi, and coworkers developed an intramolecular [2+2] photocycloaddition of 4-alkenyl coumarins (38) catalyzed by chiral thiourea 39 (Scheme 18).100–101 102 The photoadducts are produced with 77–96% ee using only 10 mol% chiral catalyst. Hydrogen bonding between the thiourea and carbonyl moieties on the catalyst and substrate organize the substrate within the chiral environment of the catalyst. Both the substrate and sensitizer efficiently absorb light, but the reaction without catalyst is slow, accounting for the lack of a significant racemic background reaction. Stern–Volmer quenching studies revealed that both static and dynamic quenching of the catalyst by the substrate is operative, and the authors proposed that both pathways lead to enantioenriched product. In the static quenching mechanism, the ground-state substrate-catalyst complex absorbs light, and the substrate undergoes cyclization. In the dynamic quenching mechanism, unbound catalyst is excited and forms a triplet exciplex with the substrate, which can undergo the cycloaddition. Sivaguru also reported the enantioselective 6π-cyclization of acrylanilides catalyzed by chiral thioureas, but the highest enantioselectivity obtained was 13% ee.103

Scheme 18.

Intramolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition Catalyzed by an Atropisomeric Thiourea Sensitizer

2.2. Ketones

2.2.1. Ketones without Hydrogen-Bonding Domains

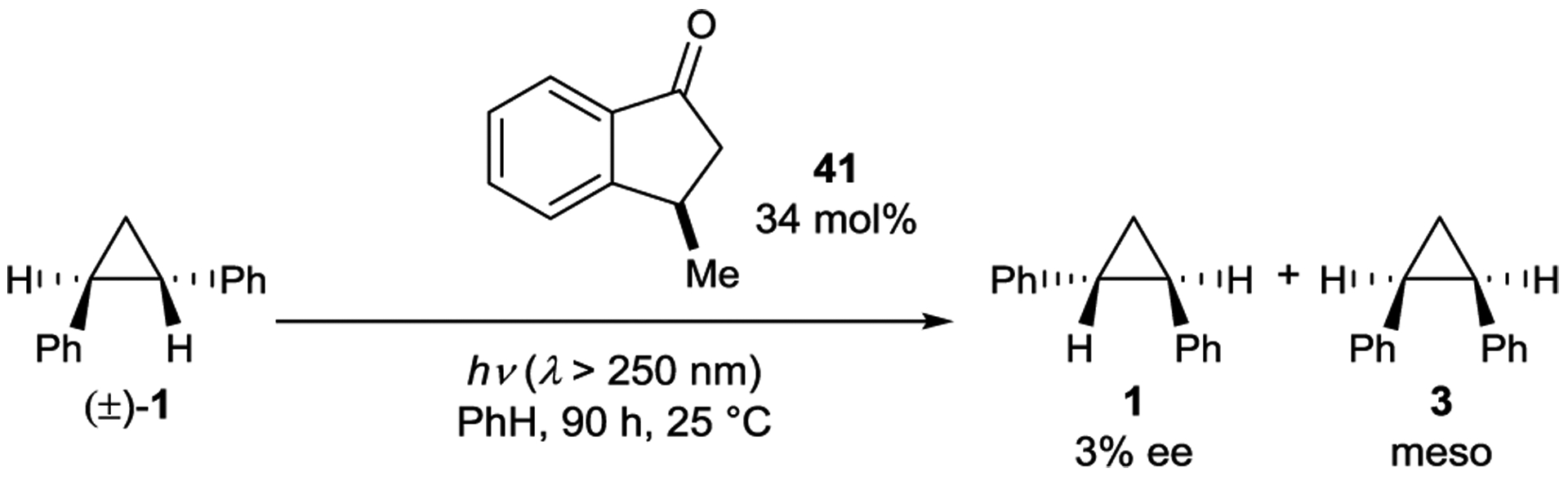

Aromatic ketones have fast rates of intersystem crossing and are often employed as triplet sensitizers.25 Despite the high efficiency with which they sensitize a variety of organic transformations, chiral aromatic ketones without hydrogen-bonding domains have not promoted highly enantioselective reactions. This is likely because the sensitizer quickly dissociates from the excited substrate after sensitization, leading to poor stereocontrol.104, 105 For instance, Ouannès and coworkers reported the asymmetric isomerization of 1 using chiral indanone triplet sensitizer 41 (Scheme 19). After 70 hours of UV irradiation, the product distribution reached a photostationary state consisting of a 3:1 ratio of cis:trans isomers and 3% ee for 1.106

Scheme 19.

Cyclopropane Isomerization Catalyzed by an Aryl Ketone Sensitizer

Chiral indanone sensitizer 43 catalyzed the kinetic resolution of ketone 42 via an oxa-di-π-methane rearrangement (Scheme 20). At low temperature and low levels of conversion, the rearranged product (44) was formed in 10% ee.107

Scheme 20.

Oxa-di-π-methane Rearrangement Catalyzed by an Aryl Ketone Sensitizer

2.2.2. Chiral Ketones with Hydrogen-Bonding Domains

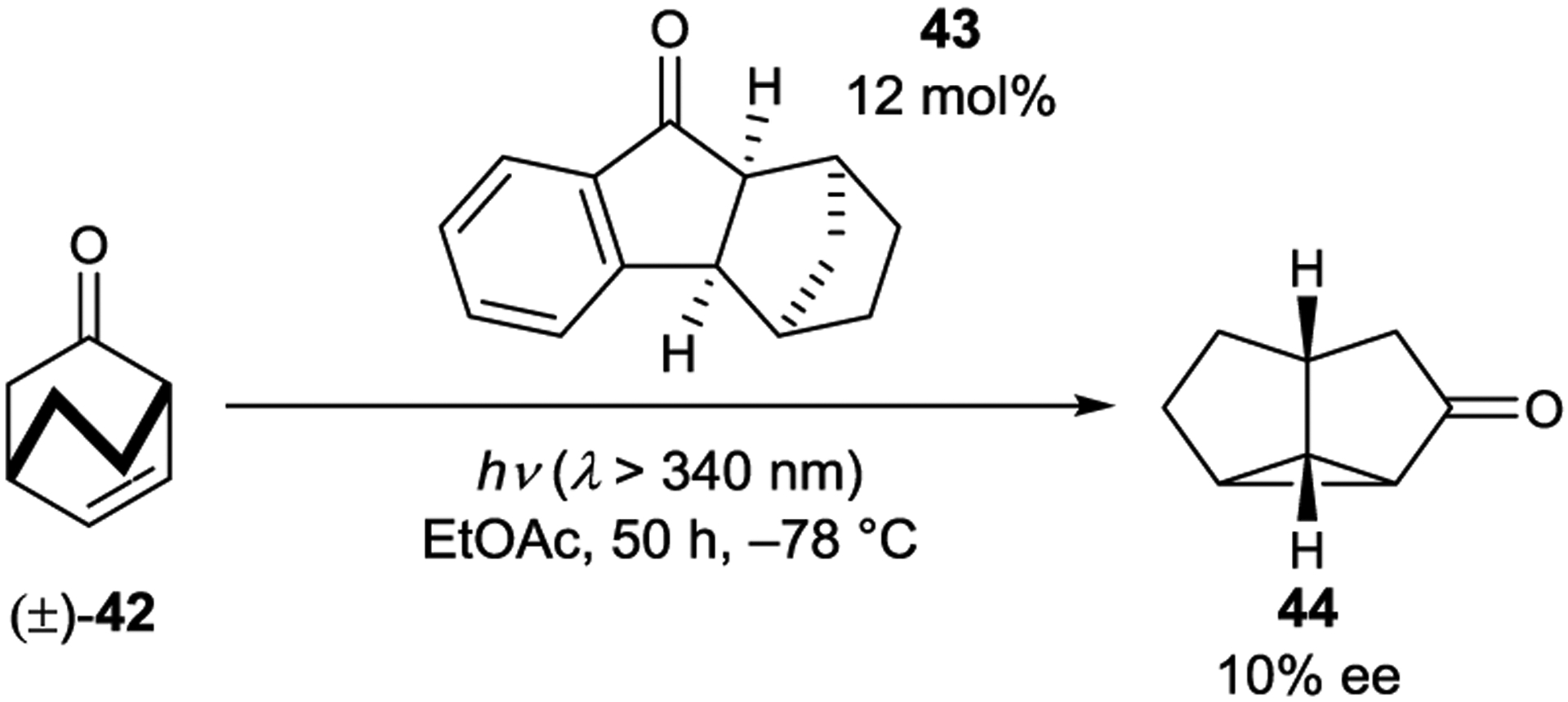

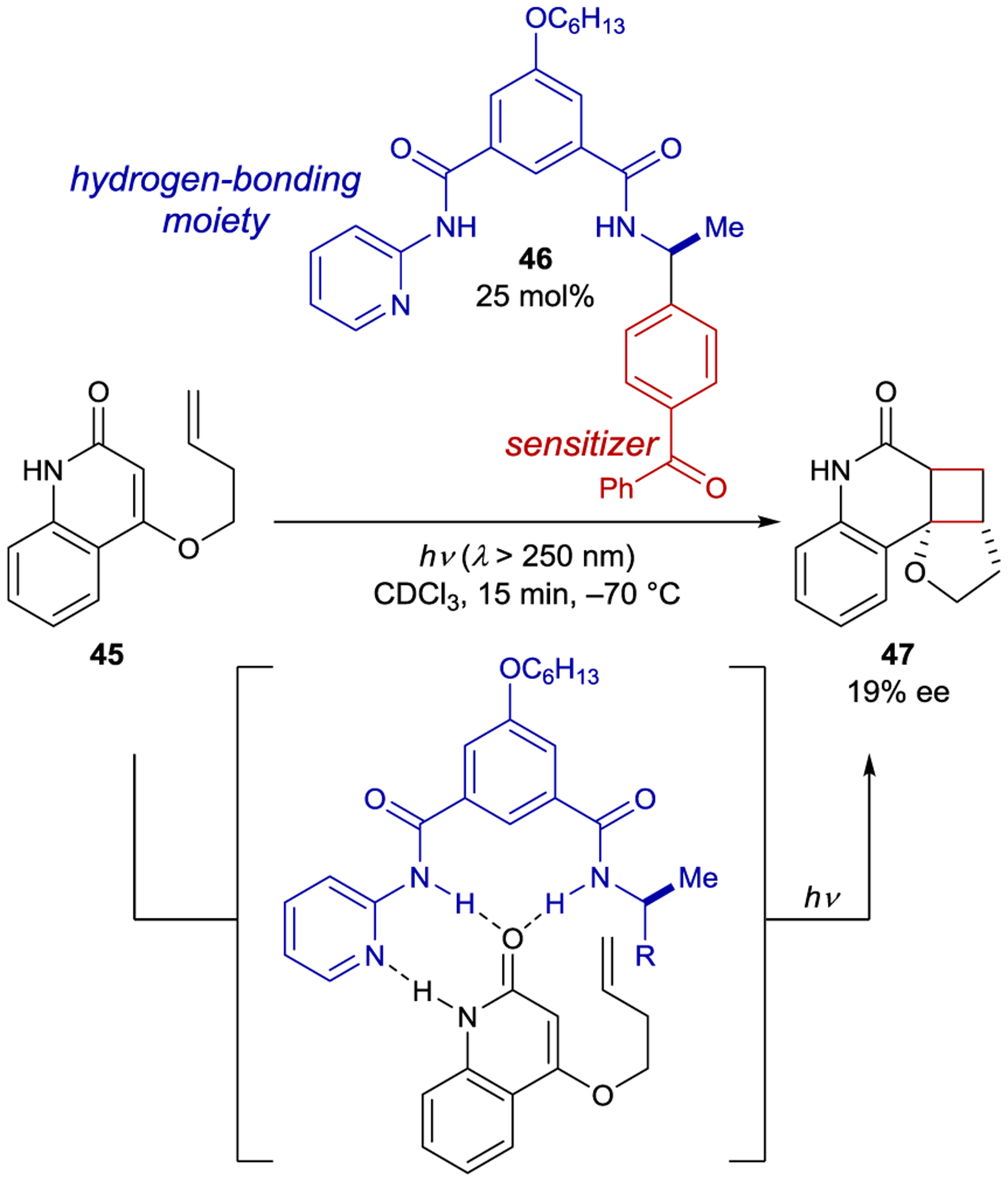

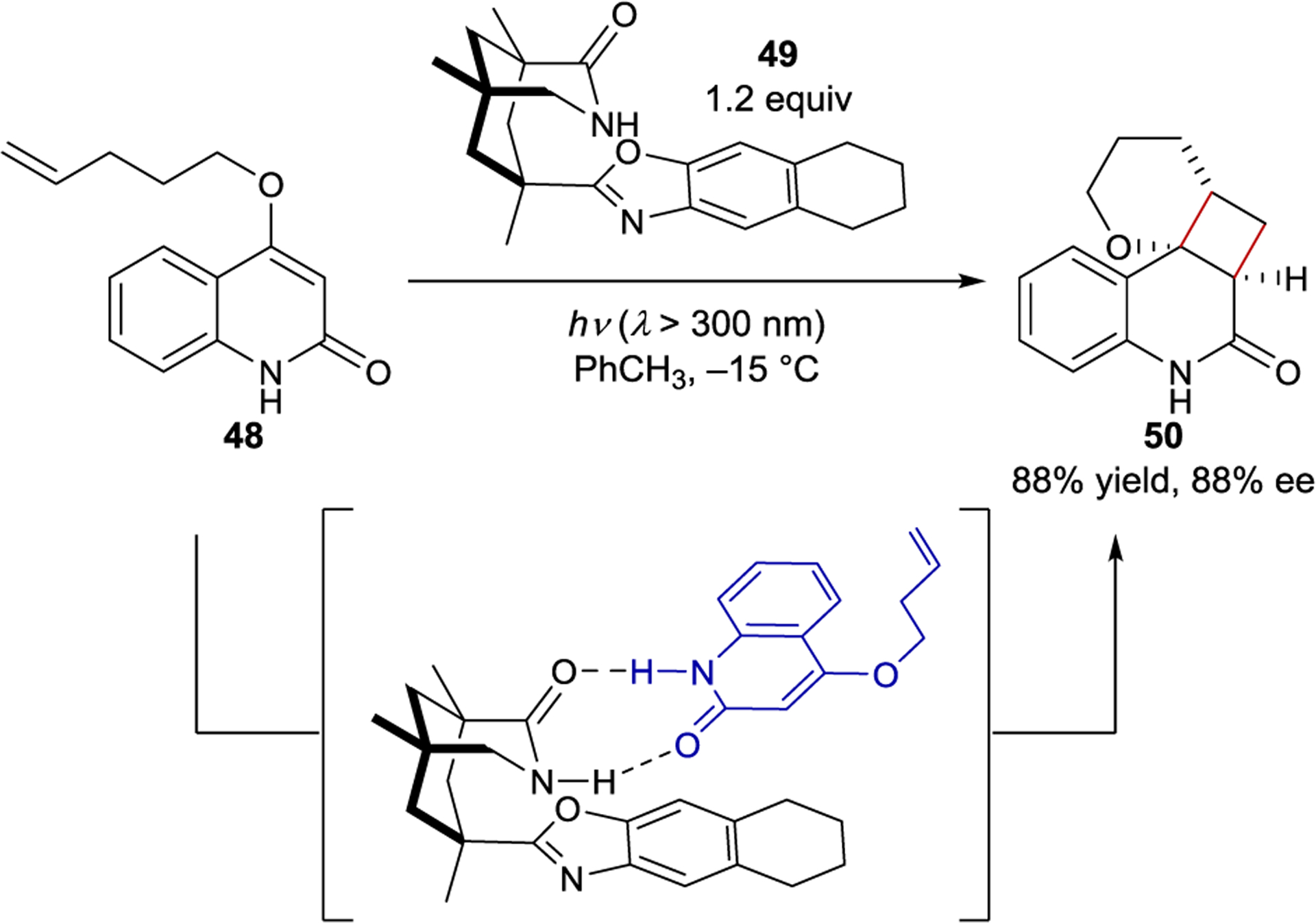

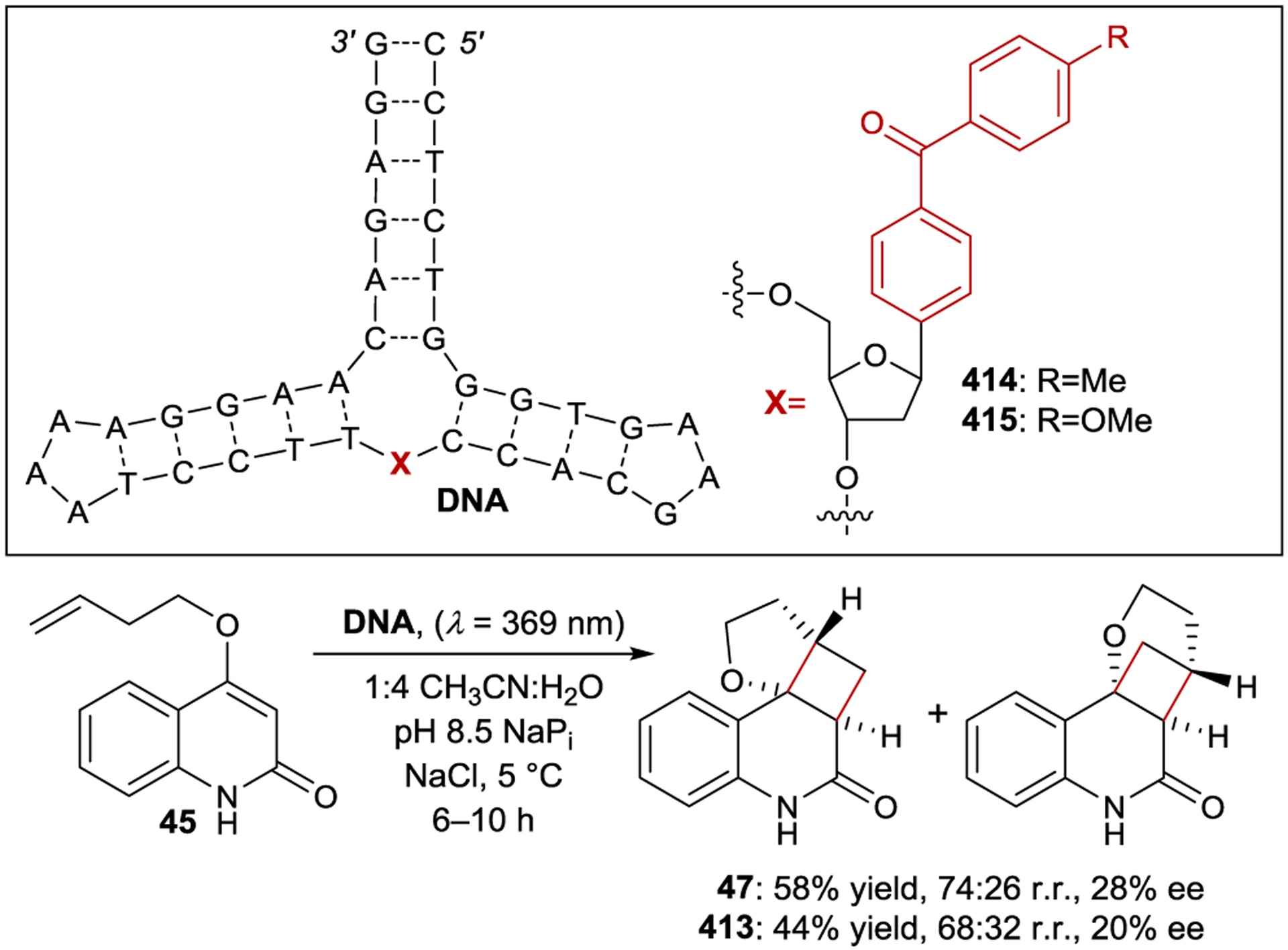

Prior to 2000, most enantioselective photoreactions involved simple chiral sensitizers where the transfer of chiral information occurs within a transient excited-state interaction with limited organization. Consequently, the enantioselectivities obtained were often low, consistent with the lack of a well-defined substrate–catalyst interaction during the enantiodetermining step. In 2003, Krische proposed that two key criteria would be essential for a highly enantioselective photocatalytic reaction: (1) the substrate must exist in a well-defined chiral environment upon binding to the catalyst, and (2) the catalyst–substrate interaction must confer a kinetic advantage to the photoreaction.10 As a potential solution to the first challenge, Krische proposed that chiral hydrogen-bonding catalysts could bind a substrate in the ground state prior to excitation ensuring a well-defined chiral environment after substrate excitation. Krische hypothesized that the second criterion could also be satisfied by introducing a benzophenone triplet sensitizer within the structure of the catalyst, creating a binding-induced rate enhancement due to the distance dependence of energy transfer. With 2 equiv of catalyst 46, quinolone 45 cyclizes to cyclobutane 47 in 21% ee via a [2+2] intramolecular photocycloaddition (Scheme 21). Notably, the catalyst loading could be lowered to 25 mol% with only a slight loss in enantioselectivity (19% ee). A Job plot and NMR binding studies confirmed complete catalyst-substrate association under the reaction conditions. These results indicate that the catalyst confers a kinetic advantage to the reaction, and that the modest enantioselectivity is the result of poor enantiofacial bias within the hydrogen-bonding complex rather than a contribution from uncatalyzed background reaction.

Scheme 21.

Intramolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition Catalyzed by a Hydrogen-Bonding Ketone Sensitizer

Thus, Krische’s hydrogen-bonding catalyst addressed the second challenge, but did not solve the first. The Bach group, on the other hand, initially solved the first challenge, but not the second. Bach prepared chiral templates derived from Kemp’s triacid that form 1:1 ground-state complexes with amide-containing substrates through hydrogen-bonding interactions.108 In this precomplexation strategy, a superstoichiometric loading of the chiral template ensures that the substrate is always bound within a chiral environment after absorbing light. Bach initially disclosed a diastereoselective Paternò–Büchi reaction using the template strategy.109, 110 Chiral template 49 is optimal for a related intramolecular enantioselective [2+2] photocycloadditon of 2-quinolone 48 (Scheme 22).111, 112 It contains both a rigid cyclohexyl backbone, restricting the conformational flexibility, and a sterically demanding benzoxazole moiety, producing effective facial differentiation in a prochiral substrate. The best enantioselectivity is achieved at low temperatures and in nonpolar solvents, both of which maximize hydrogen-bonding interactions.

Scheme 22.

Intramolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition via a Hydrogen-Bonding Amide Template

Chiral hosts related to 49 were examined in several mechanistically diverse photoreactions including intramolecular [2+2]113–114 115, intermolecular [2+2] 116–117 118 119 120, [4+2] 121, 122, and [4+4] 123, 124 cycloadditions, as well as Norrish–Yang cyclizations125,126 and electrocyclizations127. In several cases ee’s greater than 90% were reported; however, in every case superstoichiometric loadings of the template are required because the rate of photoreaction is similar for bound and unbound substrate. In order to ensure high enantioselectivity, nearly all of the substrate must be bound to the template to prevent unbound substrate reacting through a racemic pathway.

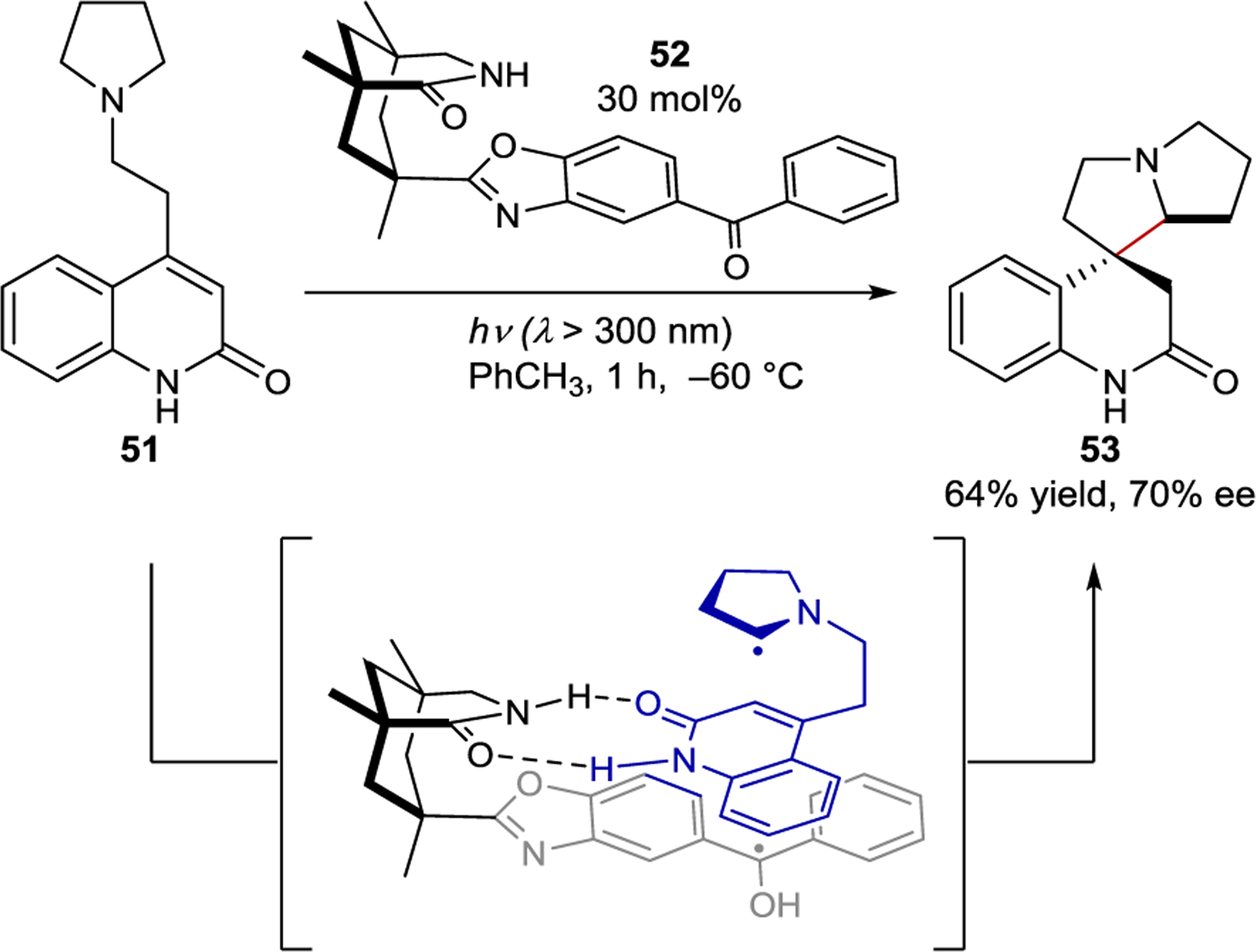

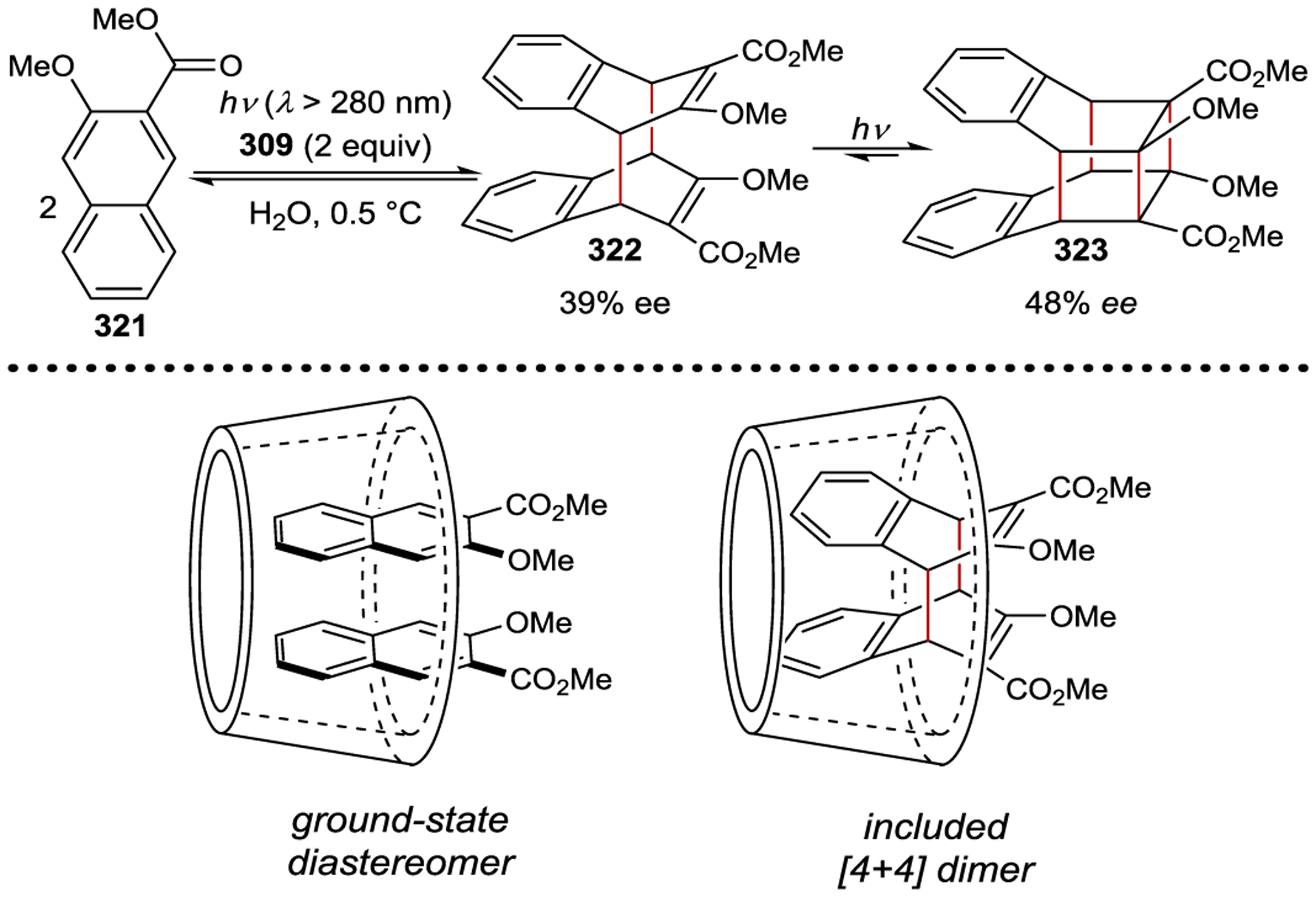

In 2005, Bach made a significant contribution to the field of asymmetric photocatalysis by incorporating a sensitizer into the chiral template.128, 129 Adding an aromatic ketone sensitizer to the existing chiral Kemp’s acid motif retained the desired hydrogen-bonding functionality of the original template while introducing the ability to catalyze the photochemical reaction of the bound substrate. Only 30 mol% of 52 was required in the cyclization of pyrrolidine 51 to spirocycle 53 in 70% ee (Scheme 23). The proposed mechanism invokes a ground-state hydrogen-bonding complex between the catalyst and substrate, situating the substrate within the chiral environment of the photocatalyst. Excitation of the ketone catalyst is followed by PET, oxidizing the bound substrate. After intramolecular proton transfer, the resulting α-amino radical cyclizes, setting the stereochemistry and producing 53 after back electron transfer and protonation. Notably, only a catalytic loading of 52 is required in the reaction because cyclization does not occur in the absence of 52.

Scheme 23.

Intramolecular Cyclization Catalyzed by a Hydrogen-Bonding Benzophenone Sensitizer

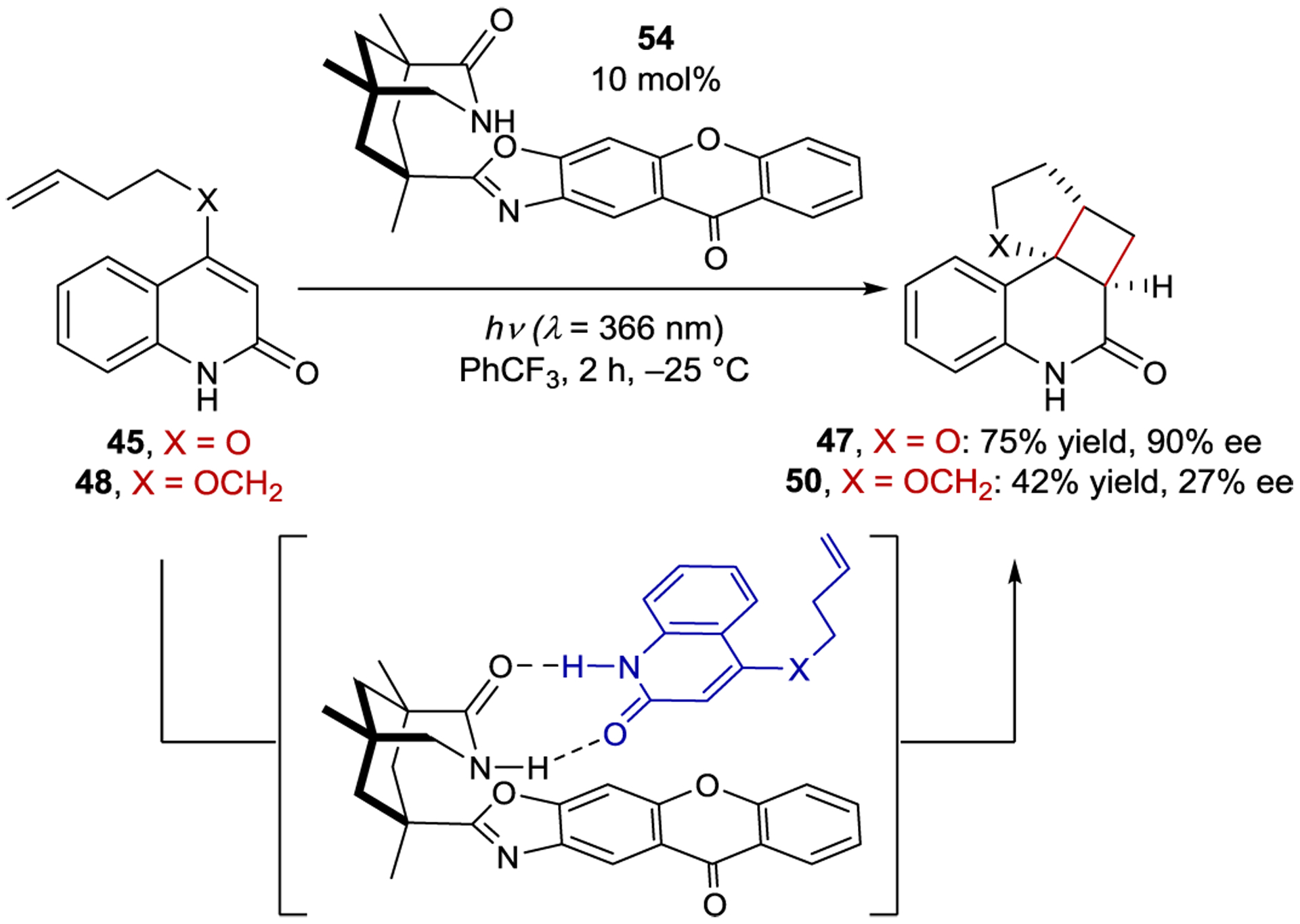

Extension of ketone catalyst 52 to energy-transfer reactions required further modification of the catalyst structure. In an intramolecular [2+2] cycloaddition of quinolone 45, benzophenone 52 afforded the cyclobutane in 39% ee, while xanthone 54 afforded the cycloadduct in 90% ee (Scheme 24).130 For both 52 and 54, the catalyst is completely bound to the substrate at the start of the reaction, thus the ground-state association does not account for the selectivity change.131 Instead, the increase in selectivity was rationalized based on the efficiency of sensitization and the rate of the subsequent reaction.132 Notably, substrate 45 absorbs at the irradiation wavelength. However, the xanthone photocatalyst 54 has a much larger extinction coefficient than the substrate and absorbs nearly all the photons under the reaction conditions. Thus, the racemic background reaction is attenuated and high enantioselectivity achieved. Conversely, benzophenone 52, which has a much lower extinction coefficient at 366 nm, does not effectively attenuate the competitive racemic background reaction, rationalizing the lowered selectivity.133 Finally, to ensure high levels of stereoinduction, the rate of the enantiodetermining step must outcompete the rate of substrate dissociation. After excitation, dissociation prior to cyclization leads to racemic product. Unlike xanthone, photoexcited benzophenone is not planar, which may facilitate faster substrate dissociation.134 This dissociation hypothesis is bolstered by the lower ee (27%) obtained when substrate 48 is sensitized by the xanthone photocatalyst. Laser flash photolysis experiments revealed that the rate of intramolecular photoreaction for 45 is approximately three times greater than for 48. Hence, while 45 reacts prior to dissociation, Bach proposed that the rates of cyclization and dissociation are similar for 48 and result in the lower enantioselectivity.

Scheme 24.

Intramolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition Catalyzed by a Xanthone Sensitizer

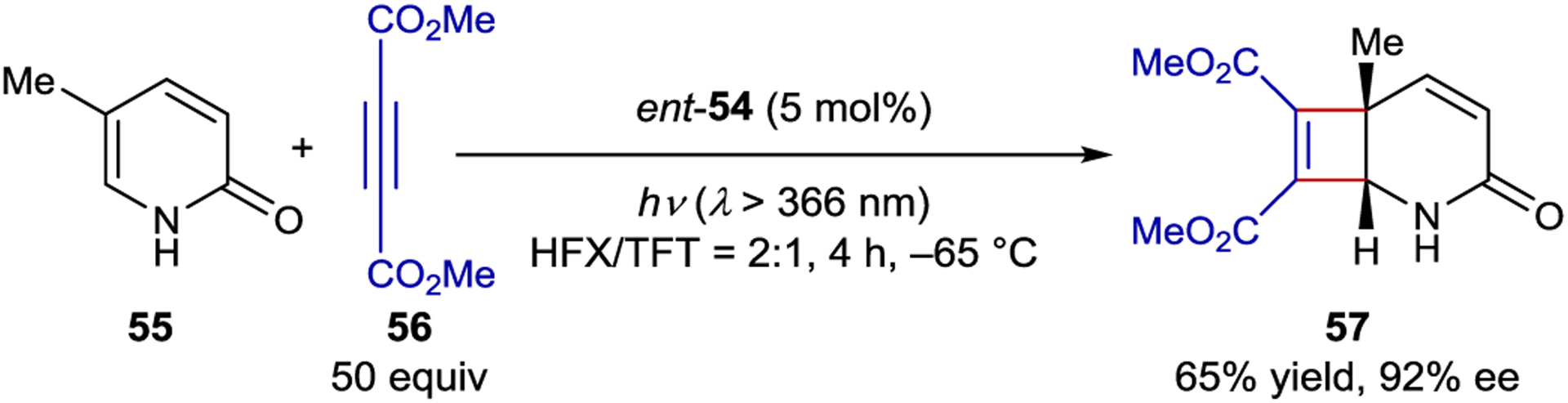

Given the competition between dissociation and cyclization, intermolecular photoreactions are considerably more difficult to design than intramolecular variants. Despite this challenge, Bach developed an intermolecular [2+2] photocycloaddition between pyridone 55 and acetylenedicarboxylates that is catalyzed by ent-54 (Scheme 25).135 Because the pyridone does not absorb the irradiated light under the reaction conditions, there is not a significant correlation between catalyst loading and ee, however, there is a correlation between alkyne loading and ee. It was proposed that a higher concentration of coupling partner leads to a faster bimolecular reaction and less possibility of substrate dissociation. The photochemical rearrangement of spirooxindole epoxides was also examined using xanthone 54, yielding product in up to 33% ee.136 Bach similarly attributed the poor selectivity to a slow rate of rearrangement relative to substrate dissociation from the catalyst.

Scheme 25.

Intermolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition Catalyzed by a Xanthone Sensitizer

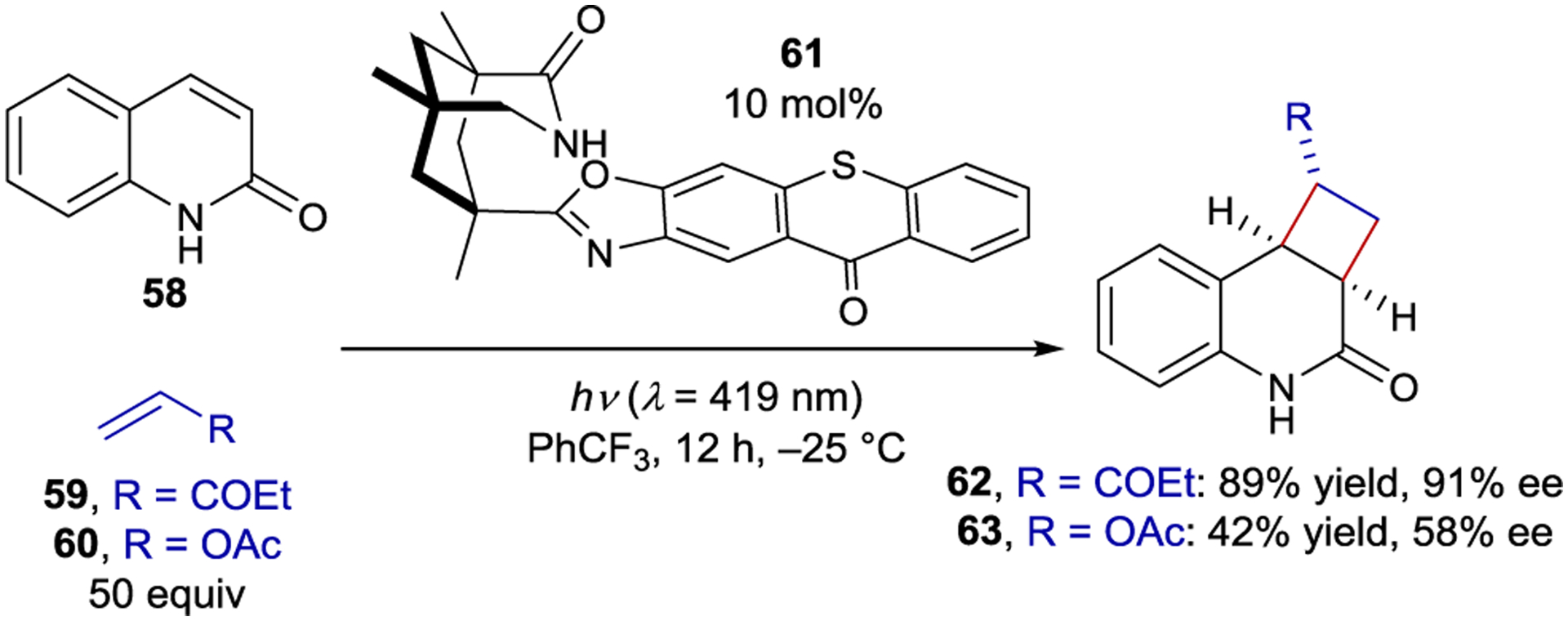

Although 54 was successful in promoting highly enantioselective reactions, there are several problems inherent with the xanthone chromophore that limited reaction development. First, photoexcited 54 is very active towards hydrogen atom abstraction. In toluene, the sensitizer decomposes in less than 10 min under 366 nm irradiation, limiting the choice of reaction solvents.137 The sensitizer also does not have a significant absorption in the visible region, necessitating irradiation at UV wavelengths that have a greater possibility of exciting free substrate. Thioxanthone 61 solves both problems: it is more stable under irradiation in toluene and possesses a significant absorption in the visible region. While the triplet energy of thioxanthone 61 (63 kcal/mol) is lower than xanthone 54 (76 kcal/mol), it is high enough to sensitize a variety of substrate molecules. The new sensitizer was evaluated in the canonical quinolone intramolecular [2+2] photoreaction producing cycloadducts in up to 96% ee under visible light irradiation.137 Under similar conditions, 3-alkylquinolones with tethered alkenes and allenes were also amenable to the intramolecular cycloaddition.138

An intermolecular [2+2] photocycloaddition between quinolone 58 and a variety of alkene coupling partners was also catalyzed by 61; however, 50 equiv of the coupling partner were needed to ensure cyclization occurs prior to dissociation from the catalyst (Scheme 26).139 It follows from this analysis that alkenes that react at slower rates should be expected to give lower enantioselectivities. Vinyl acetate (60) reacts more than an order of magnitude slower than ethyl vinyl ketone (59) when sensitized by an achiral thioxanthone, and consequently gave cycloadducts in significantly lower ee (91% ee vs. 58% ee).

Scheme 26.

Intermolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition Catalyzed by a Thioxanthone Sensitizer

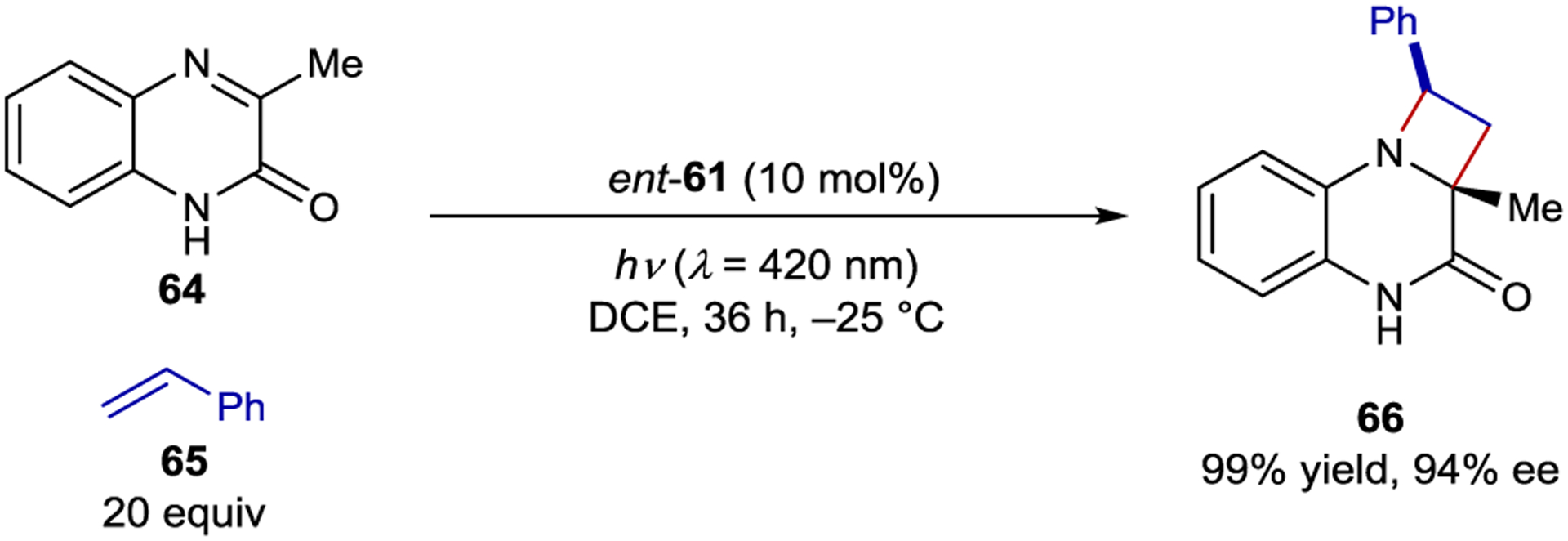

Thioxanthone ent-61 is also an effective photocatalyst for enantioselective aza-Paternò–Büchi reactions that produce chiral azetidines.140 Cyclic imine 64 was tested in the [2+2] reaction shown in Scheme 27, because N-substituted quinoxalinones were previously shown to undergo [2+2] cycloadditions with arylalkenes.141 A variety of styrenes were accommodated as coupling partners in the reaction affording azetidines in high yields and up to 98% ee.

Scheme 27.

Aza-Paternò–Büchi Reaction Catalyzed by a Thioxanthone Sensitizer

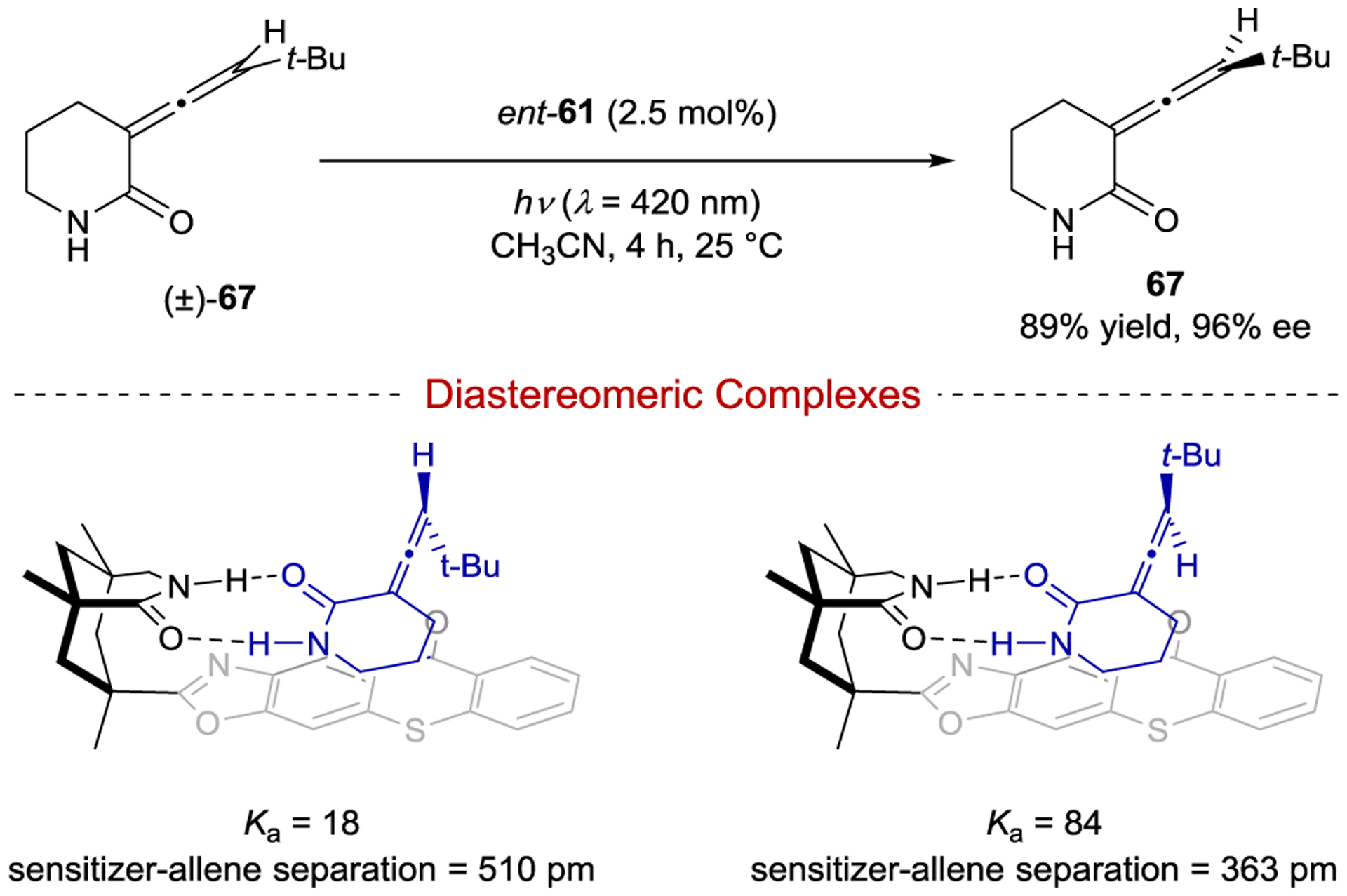

In addition to cycloadditions, thioxanthone 61 has proven to be applicable to photocatalytic deracemization. Under optimized reaction conditions Bach found that allene 67 could be deracemized in up to 97% ee (Scheme 28).142, 143 Mechanistically, triplet energy transfer to chiral allene 67 from thioxanthone 61 produces the achiral triplet-state allene.144 A measured quantum yield of racemization of Φ = 0.52 suggests that the excited achiral triplet allene decays with equal probability to 67 or ent-67. Deracemization is therefore achieved during the sensitization step of the reaction. Because both the allene and sensitizer are chiral, two distinct diastereomeric ground-state sensitizer–allene complexes can form. NMR titrations provided association constants of Ka = 84 and 18 for the respective diastereomeric complexes. The stronger-binding enantiomer is preferentially sensitized and thus selectively depleted over the course of the reaction, enriching the population of the weaker-binding antipode. Notably, the strategy relies on the fact that after sensitization the excited triplet allene dissociates from the catalyst and decays unselectively to the ground state leading to racemization of the stronger binding enantiomer. If, on the other hand, the allene always remained bound to the sensitizer during decay back to the ground state, retention of configuration would likely be expected. Thus, in contrast to cycloaddition reactions where dissociation of excited-state substrate is typically a hurdle in reaction development, dissociation is necessary to achieve high enantioselectivity in deracemization reactions. Computational studies also suggested that the separation between allene and thioxanthone was smaller for the stronger-binding complex, leading to more efficient energy transfer than the other diastereomeric complex. Thus, both the difference in ground-state association constants and the excited-state sensitization efficiencies for the two diastereomeric complexes are responsible for the high selectivity for deracemization.

Scheme 28.

Allene Deracemization Catalyzed by a Thioxanthone Sensitizer

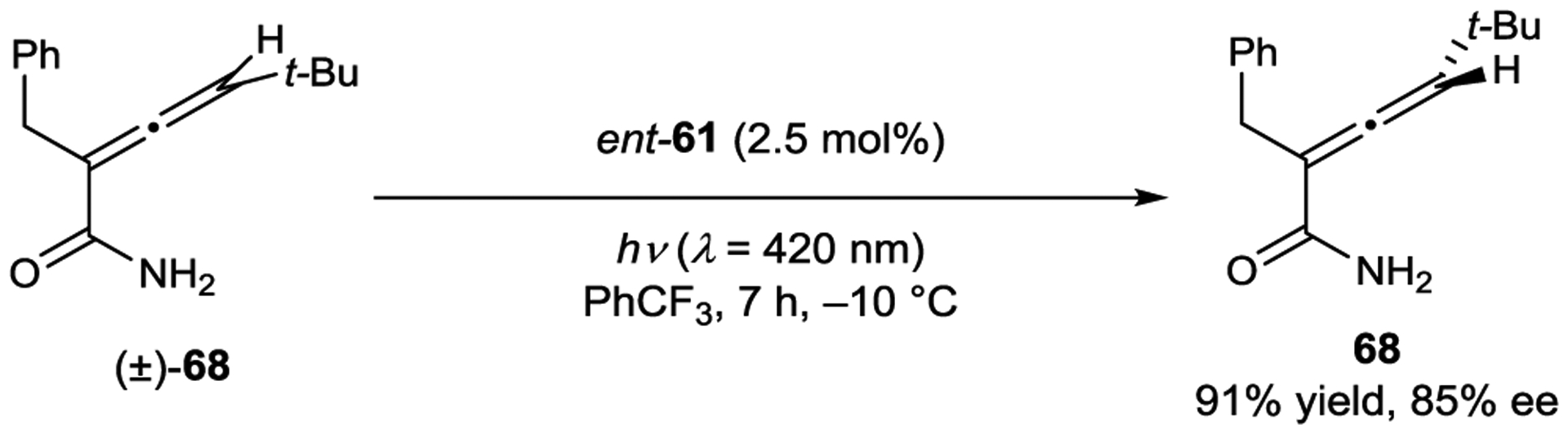

Thioxanthone 61 also catalyzed the deracemization of primary amides in up to 93% ee (Scheme 29).145 A combination of experimental and computational studies again confirmed that both ground-state association constants and excited-state sensitization efficiencies contribute to the enantioselectivity.

Scheme 29.

Primary Allene Amide Deracemization Catalyzed by a Thioxanthone Sensitizer

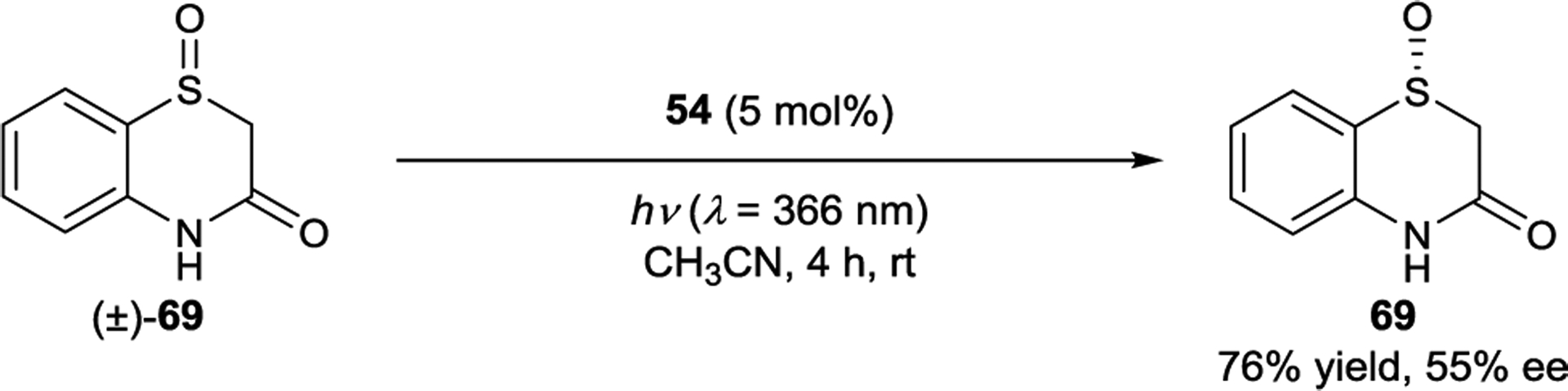

Xanthone 54 catalyzes the deracemization of cyclic sulfoxides in up to 55% ee (Scheme 30).146 An analogous mechanism was proposed in which one enantiomer of 69 binds more strongly to 54 than ent-69, leading to more efficient sensitization for the former. Once excited, the substrate dissociates from the chiral catalyst and can undergo stereochemical inversion prior to relaxation to the ground state. Over time, the enantiomer that binds the catalyst more strongly is preferentially depleted via unselective racemization.

Scheme 30.

Sulfoxide Deracemization Catalyzed by a Xanthone Sensitizer

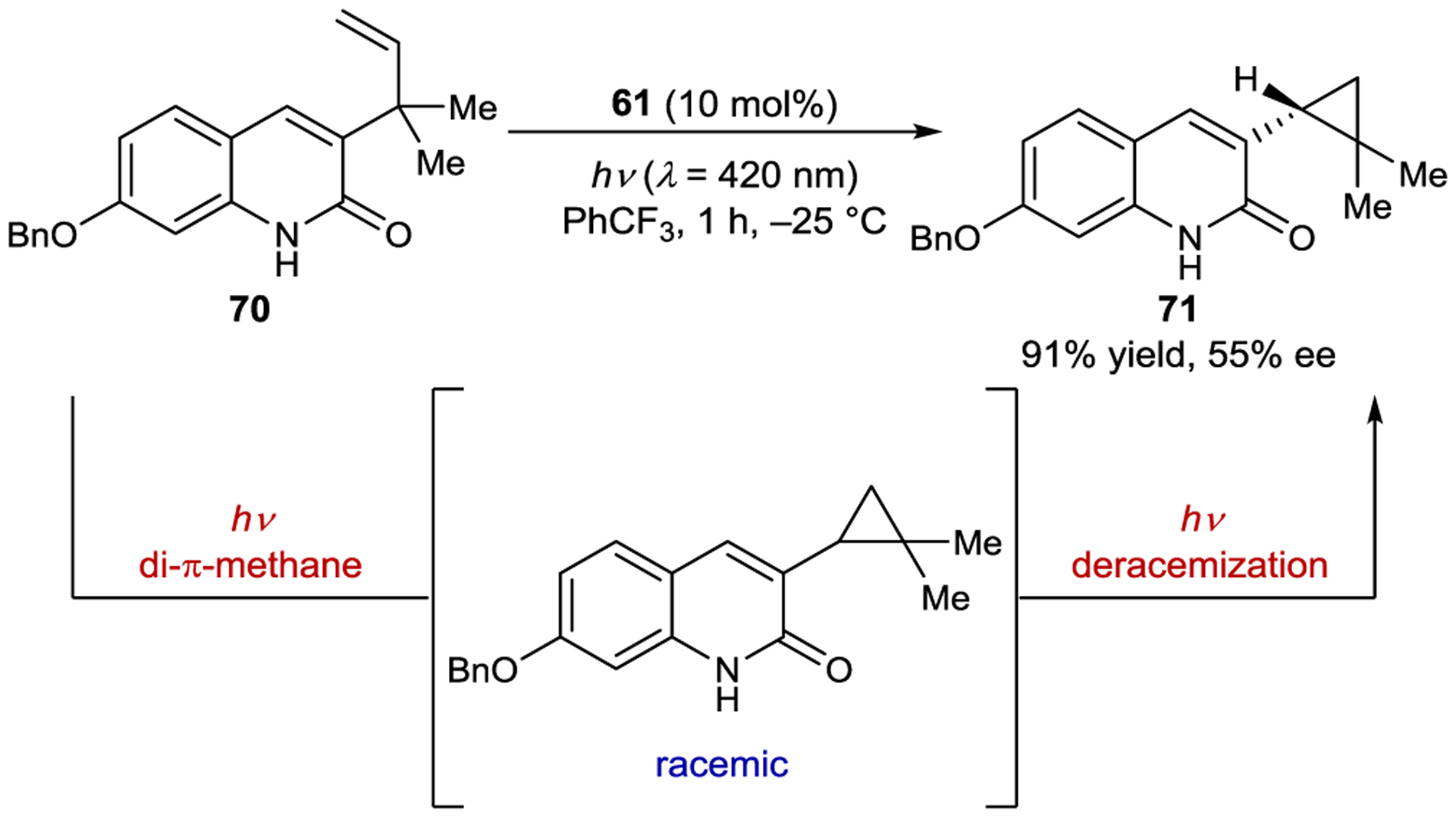

In theory, any substrates that racemize in the excited state could be amenable to photoderacemization. Bach and coworkers discovered the photoderacemization of 3-cyclopropylquinolones by 61 serendipitously when attempting to develop an enantioselective di-π-methane rearrangement (Scheme 31).147 They observed that the enantioselectivity of the cyclopropane product increased from nearly 0% ee to 55% ee within the first hour of irradiation.

Scheme 31.

Di-π-Methane Rearrangement–Cyclopropane Deracemization Cascade Catalyzed by a Thioxanthone Sensitizer

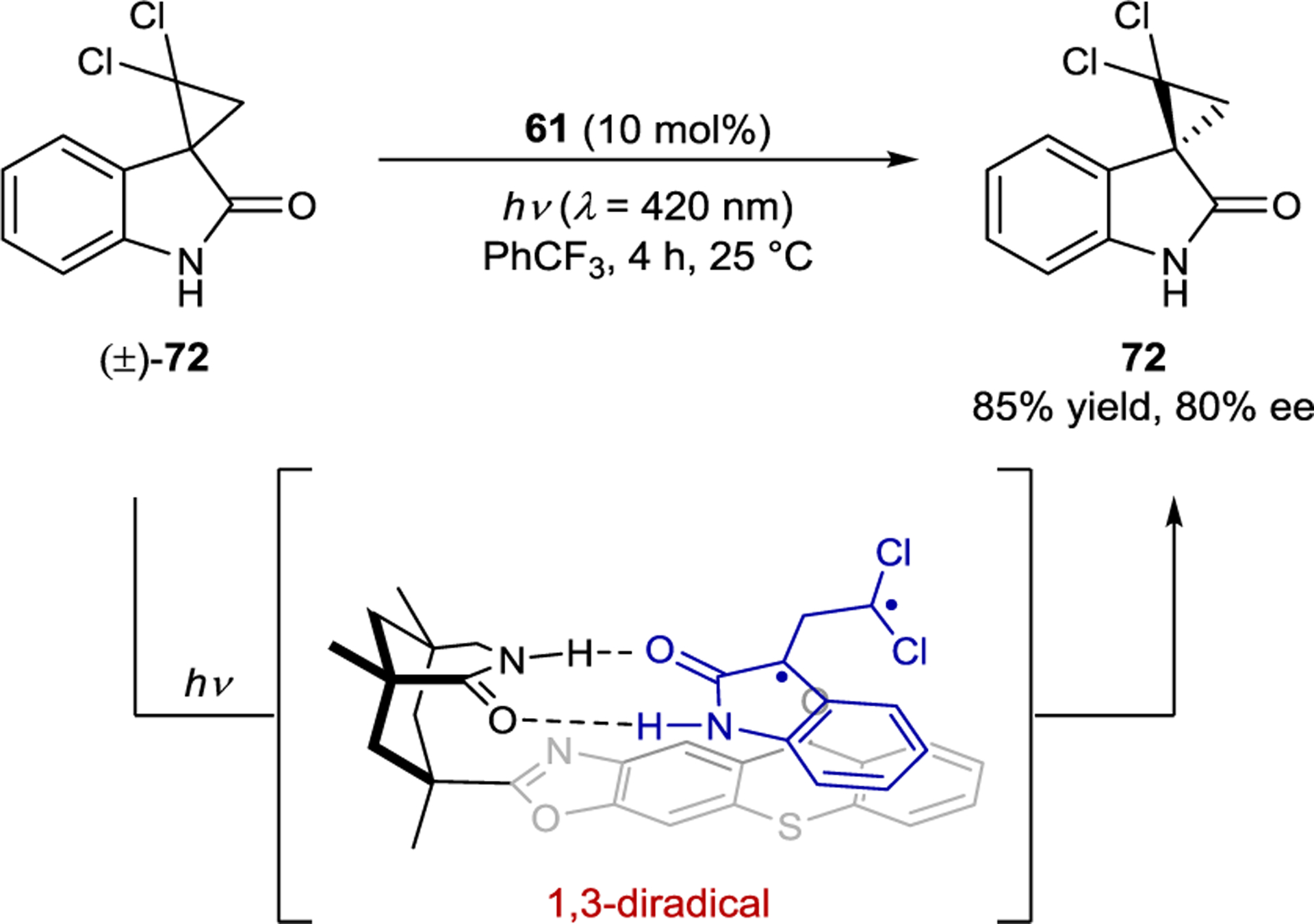

Detailed mechanistic studies were undertaken for the related deracemization of spirocyclopropyl oxindoles (Scheme 32).148 Transient absorption studies suggested a triplet energy transfer from the sensitizer to cyclopropyl substrate 72. The spectral position and shape of the transient signal of the triplet substrate also matched that calculated for the expected ring-opened 1,3-diradical. As with allene deracemization, both the ground-state association constants and excited-state sensitization kinetics of the diastereomeric substrate–catalyst complexes were invoked to account for the enantioenrichment of the product. The triplet lifetime of the 1,3-diradical is 22 μs while the lifetime of the substrate–sensitizer complex is below 1 μs, implying that the 1,3-diradical dissociates from the catalyst prior to cyclization. This kinetic regime is desirable since cyclization within the chiral domain of the catalyst would favor retention of configuration.

Scheme 32.

Cyclopropane Deracemization Catalyzed by a Thioxanthone Sensitizer

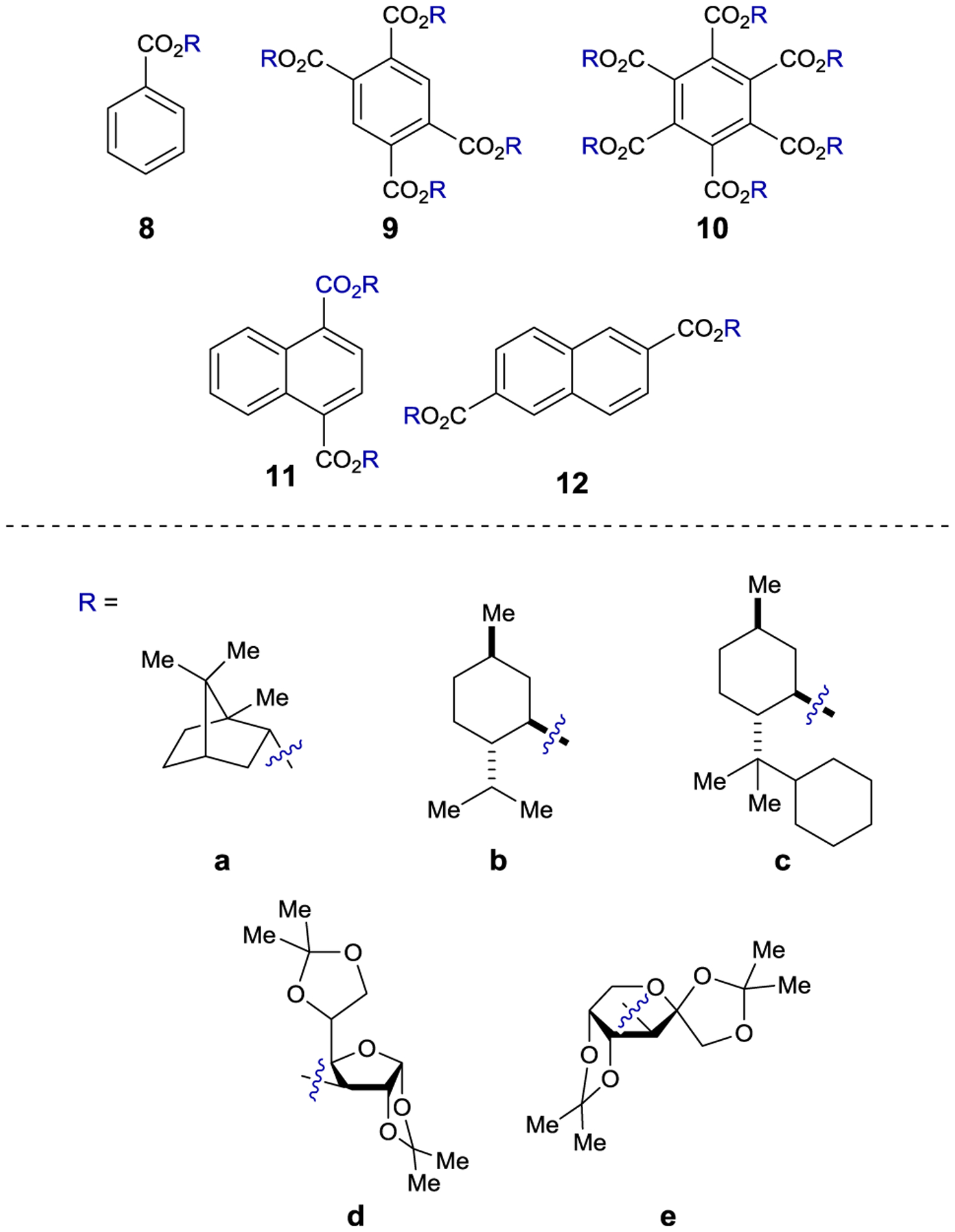

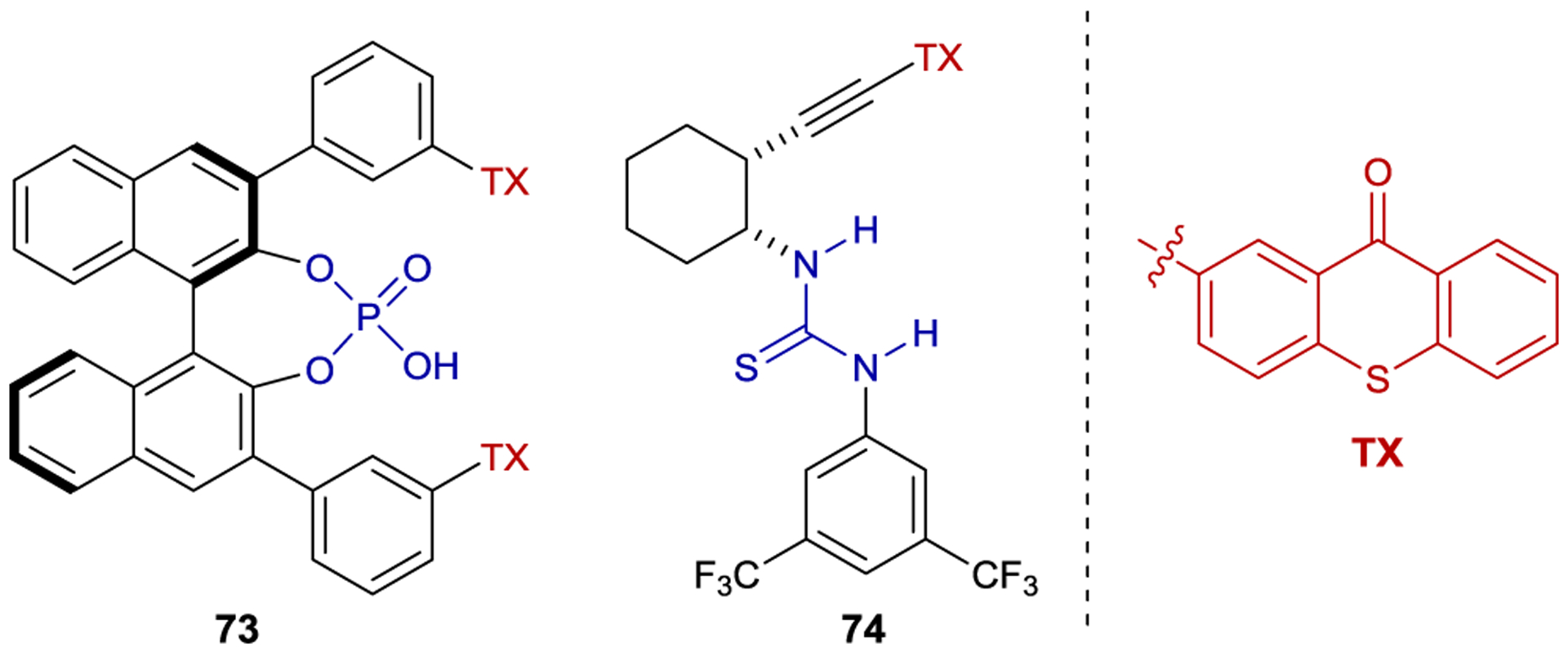

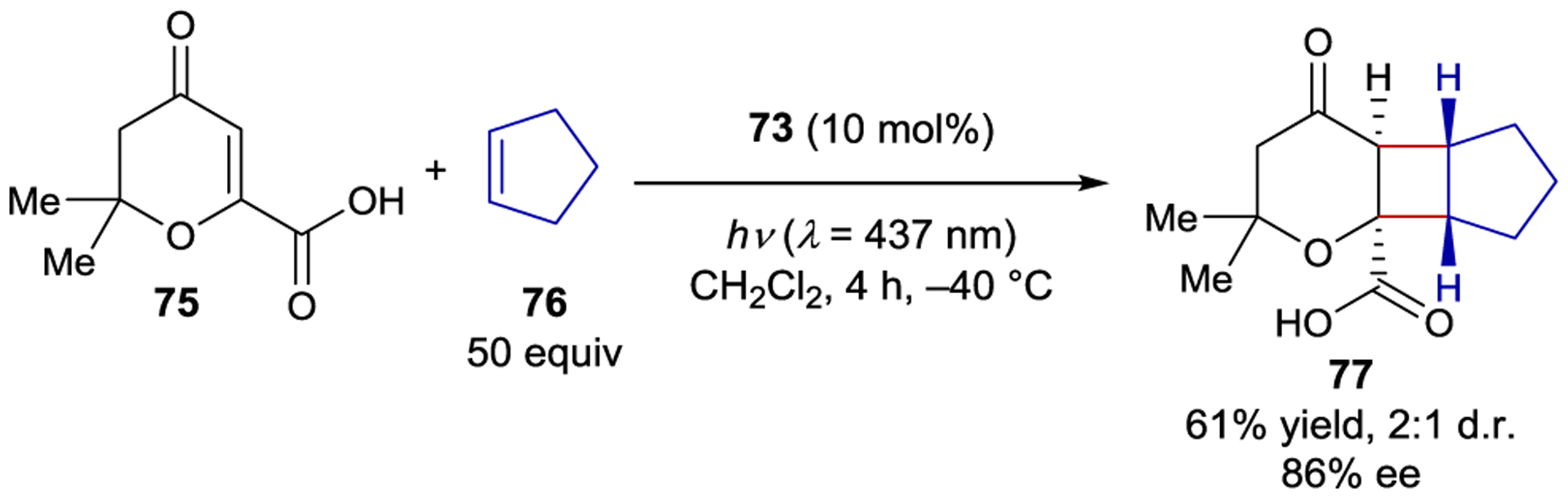

Despite the wide range of photochemical reactions that can be catalyzed by xanthone 54 and thioxanthone 61, the reactions are limited to lactam-containing substrates.149 In an attempt to expand the range of available binding motifs, Bach and coworkers have recently prepared new catalysts that incorporate a thioxanthone sensitizer into an alternate chiral hydrogen-bonding scaffold (Figure 2). While thiourea-linked thioxanthone 74 does not induce high levels of enantioselectivity in a sensitized 6π-electrocyclization (12% ee),150 BINOL-derived phosphoric acid 73 catalyzes an intermolecular [2+2] cycloaddition between carboxylic acid 75 and cyclopentene (76) in 86% ee (Scheme 33).151 NMR studies demonstrated that the carboxylic acid substrate binds the BINOL catalyst under the reaction conditions. Computational studies support a 1:1 complex but suggest that several binding modes are similar in energy, which may account for the moderate enantioselectivity. Takagi has studied a simpler BINOL-derived phosphoric acid lacking a thioxanthone substituent in asymmetric intramolecular [2+2] photocycloadditions of quinolones. However, in this reaction a stoichiometric loading of the acid template was necessary, presumably because both bound and unbound substrate react at similar rates.152

Figure 2.

Chiral Thioxanthone-Derived Sensitizers

Scheme 33.

Intermolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition Catalyzed by a BINOL-Derived Thioxanthone Sensitizer

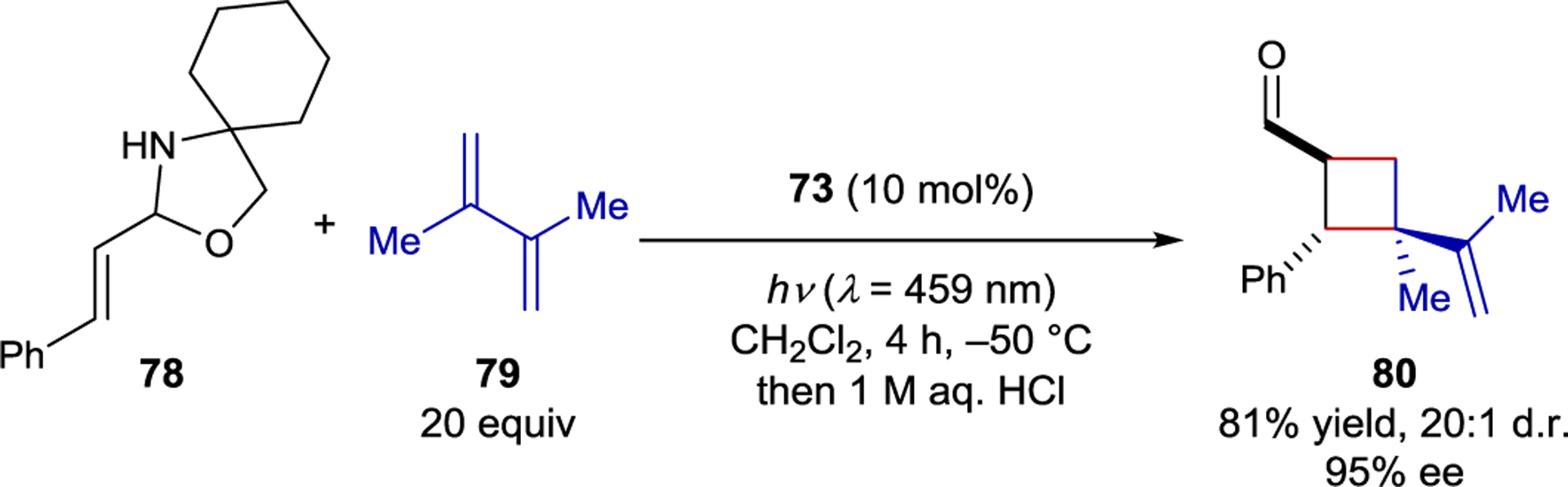

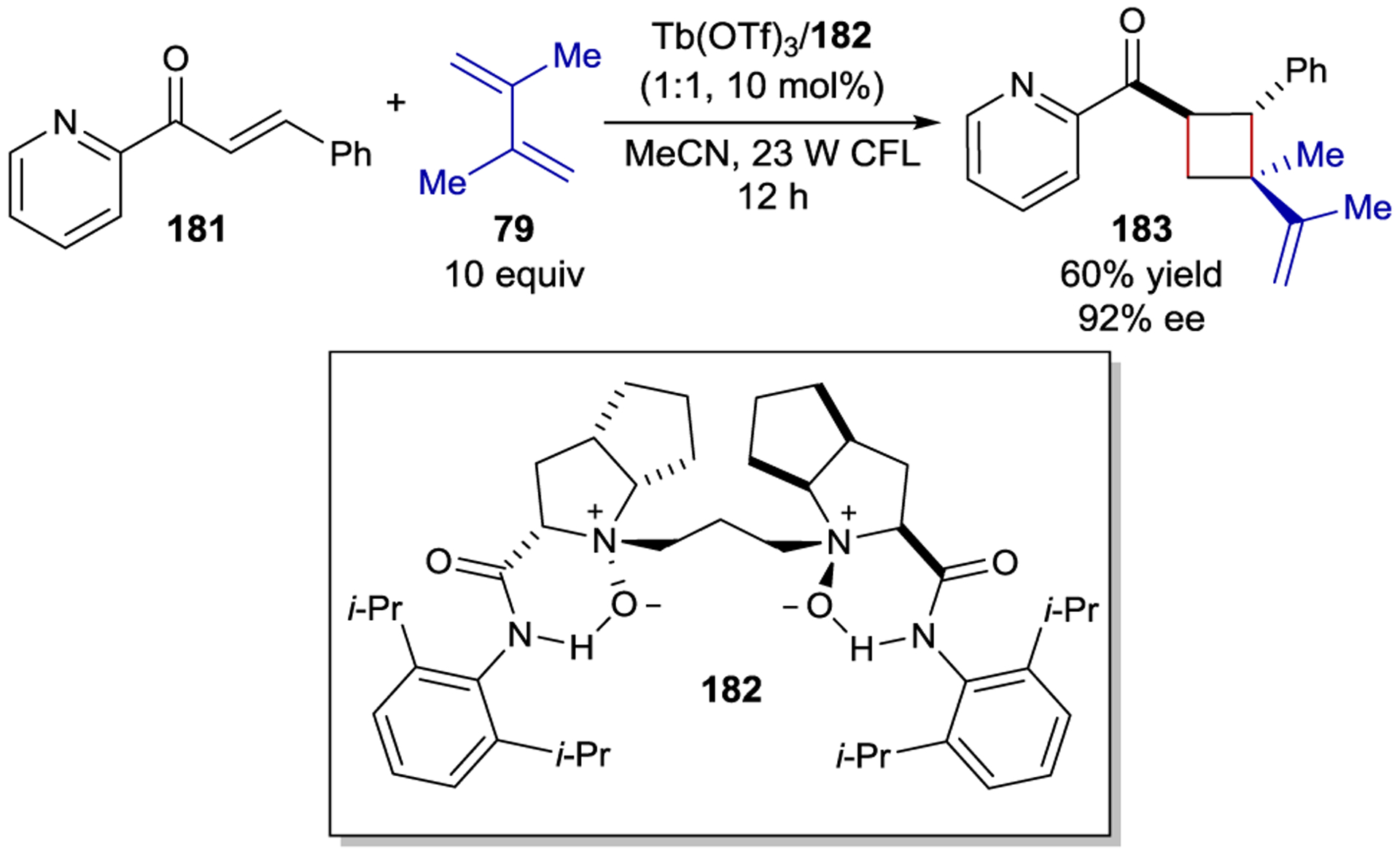

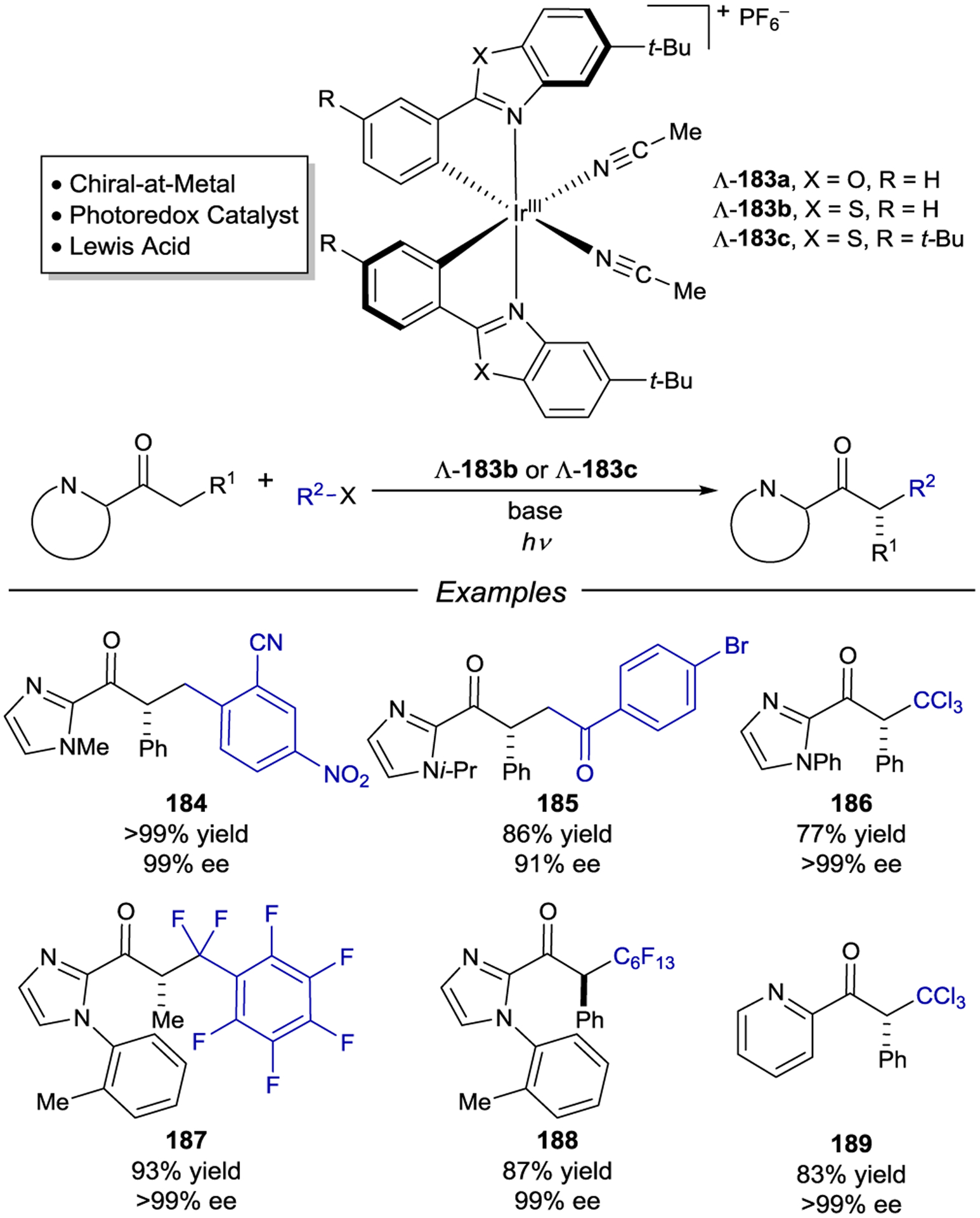

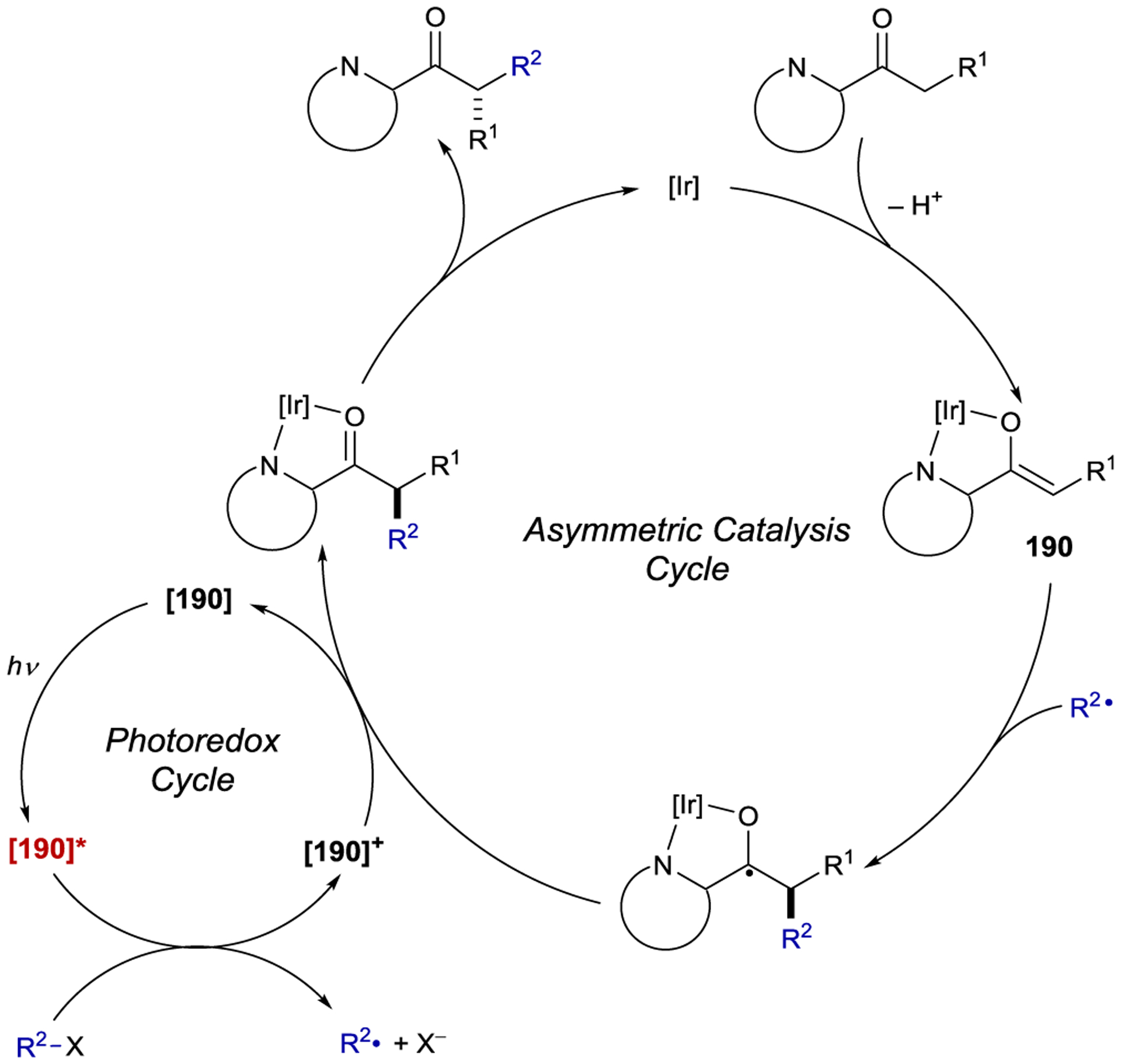

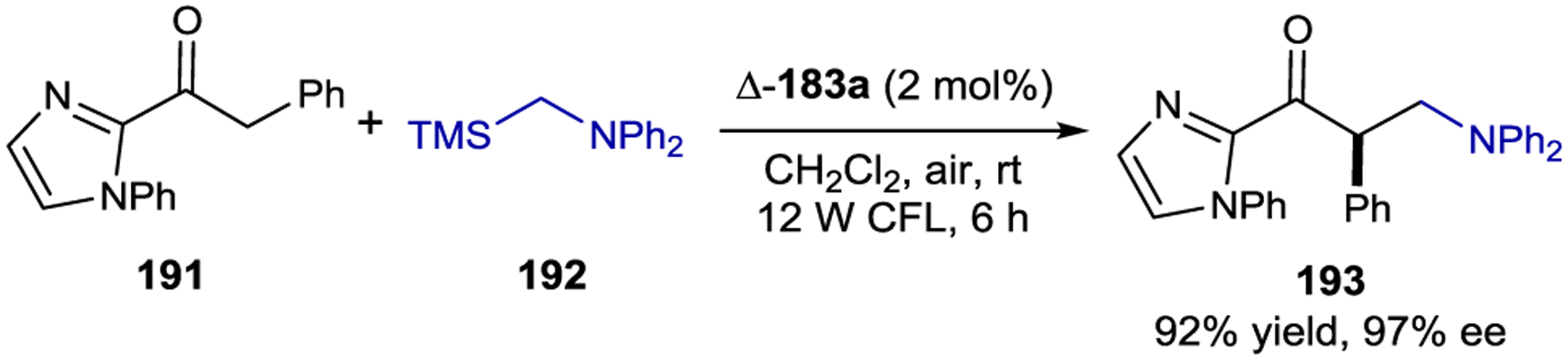

Thioxanthone 73 catalyzes the enantioselective photocycloaddition of N,O-acetal 78 and alkene 79 in 95% ee (Scheme 34). NMR studies revealed that 78 exists as a mixture of the cyclic N,O-acetal and the ring-opened imine. UV-Vis absorption studies showed that a bathochromic shift occurs upon protonation of the imine, while emission studies providing the triplet energies of the iminium ion and thioxanthone catalyst (51 kcal/mol and 56 kcal/mol, respectively) showed that energy transfer to the iminium was exothermic. Conversely, both the N,O-acetal and unprotonated imine are unable to be sensitized by the photoexcited thioxanthone catalyst.

Scheme 34.

Intermolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition of Iminium Ions Catalyzed by a BINOL-Derived Thioxanthone Sensitizer

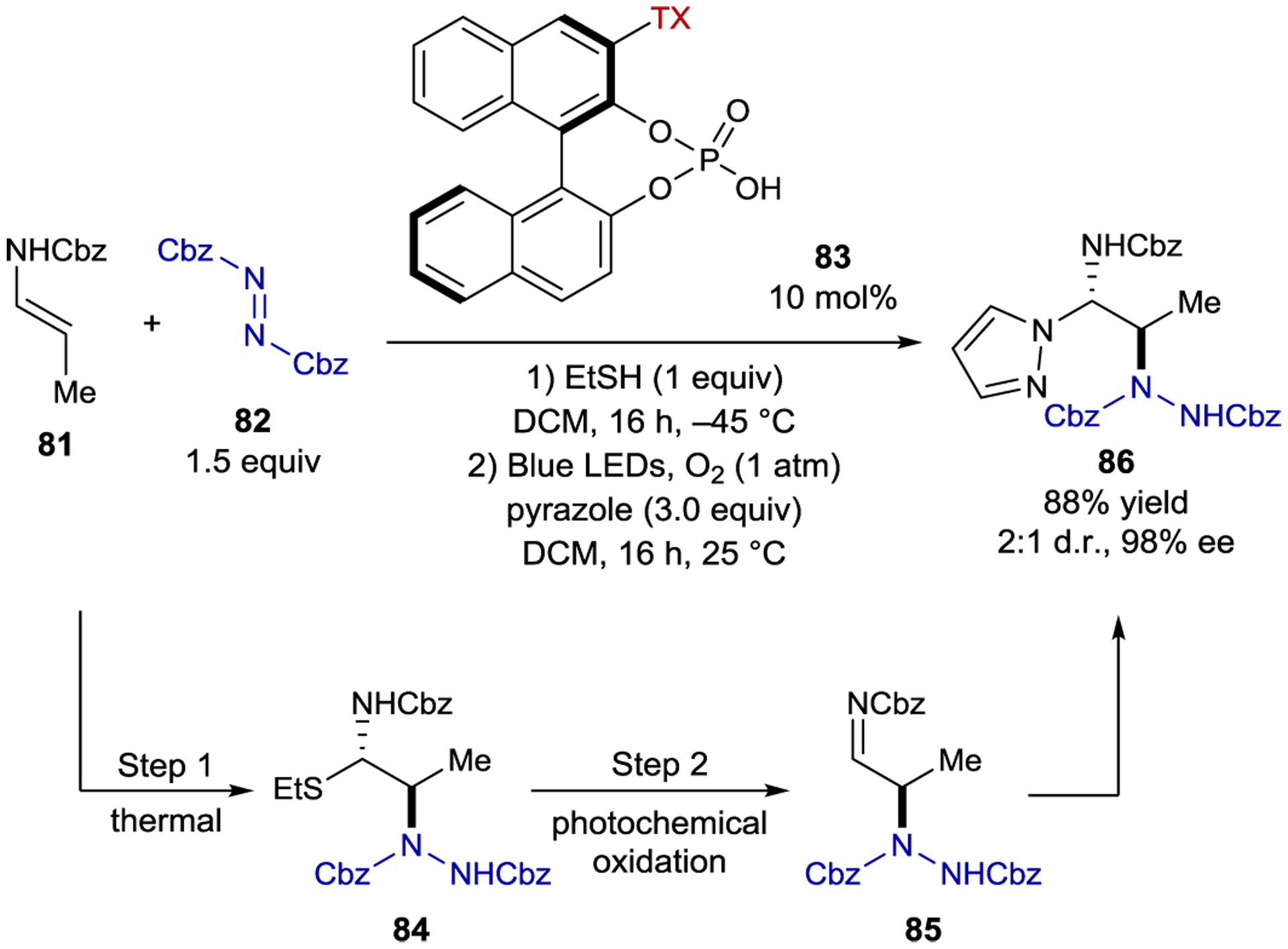

Masson developed a non-C2-symmetric BINOL-derived catalyst with a tethered thioxanthone chromophore for the enantioselective synthesis of 1,2-diamines (Scheme 35).153 This reaction occurs in two steps. In the first, the nucleophilic enecarbamate reacts with the electrophilic azodicarboxylate in an enantioselective thermal reaction. The resulting imine is unstable under the reaction conditions; thus ethanethiol is added to generate α-carbamoylsulfide 84. In the second step, pyrazole is added and the reaction is irradiated with blue light. The authors propose that α-carbamoylsulfide 84 is photochemically oxidized to the sulfur radical cation, triggering mesolytic cleavage of thiyl radical and ultimately generating imine 85, which is intercepted by pyrazole in a thermal, diastereodetermining reaction. Notably, both stereodetermining steps in this reaction are thermal, while the only photochemical step regenerates the reactive imine intermediate.

Scheme 35.

1,2-Diamine Synthesis Catalyzed by a BINOL-Derived Thioxanthone Sensitizer

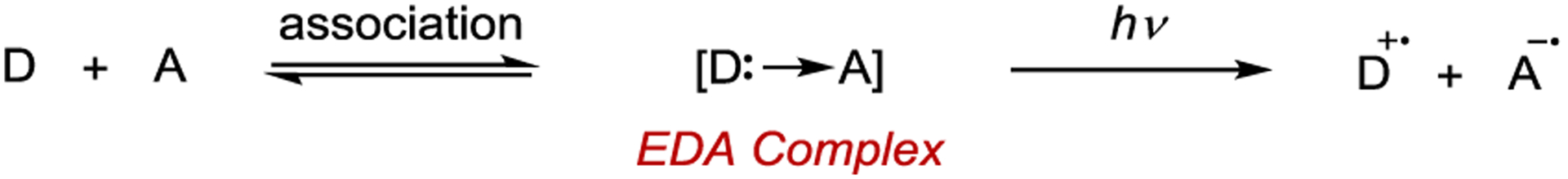

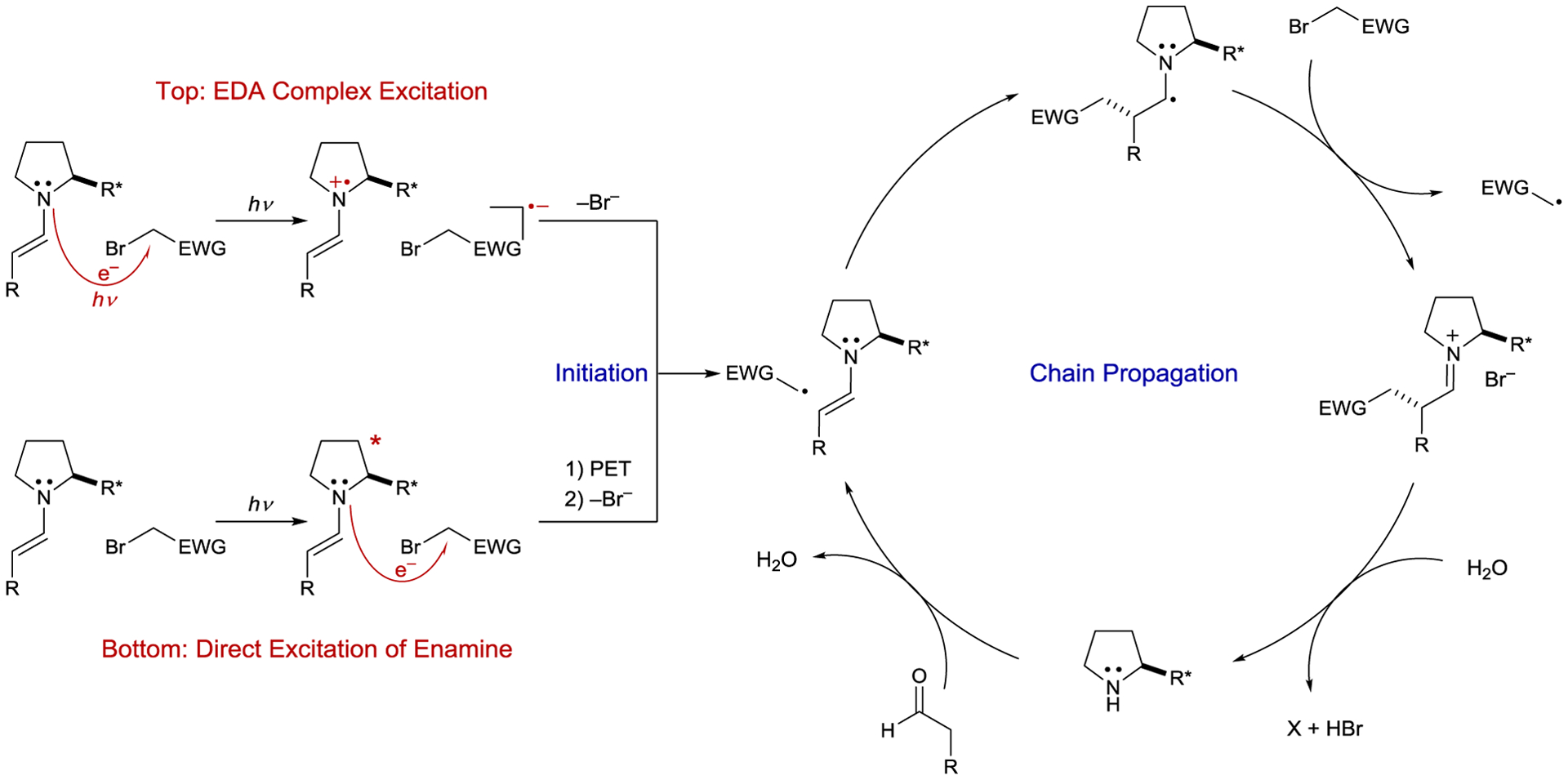

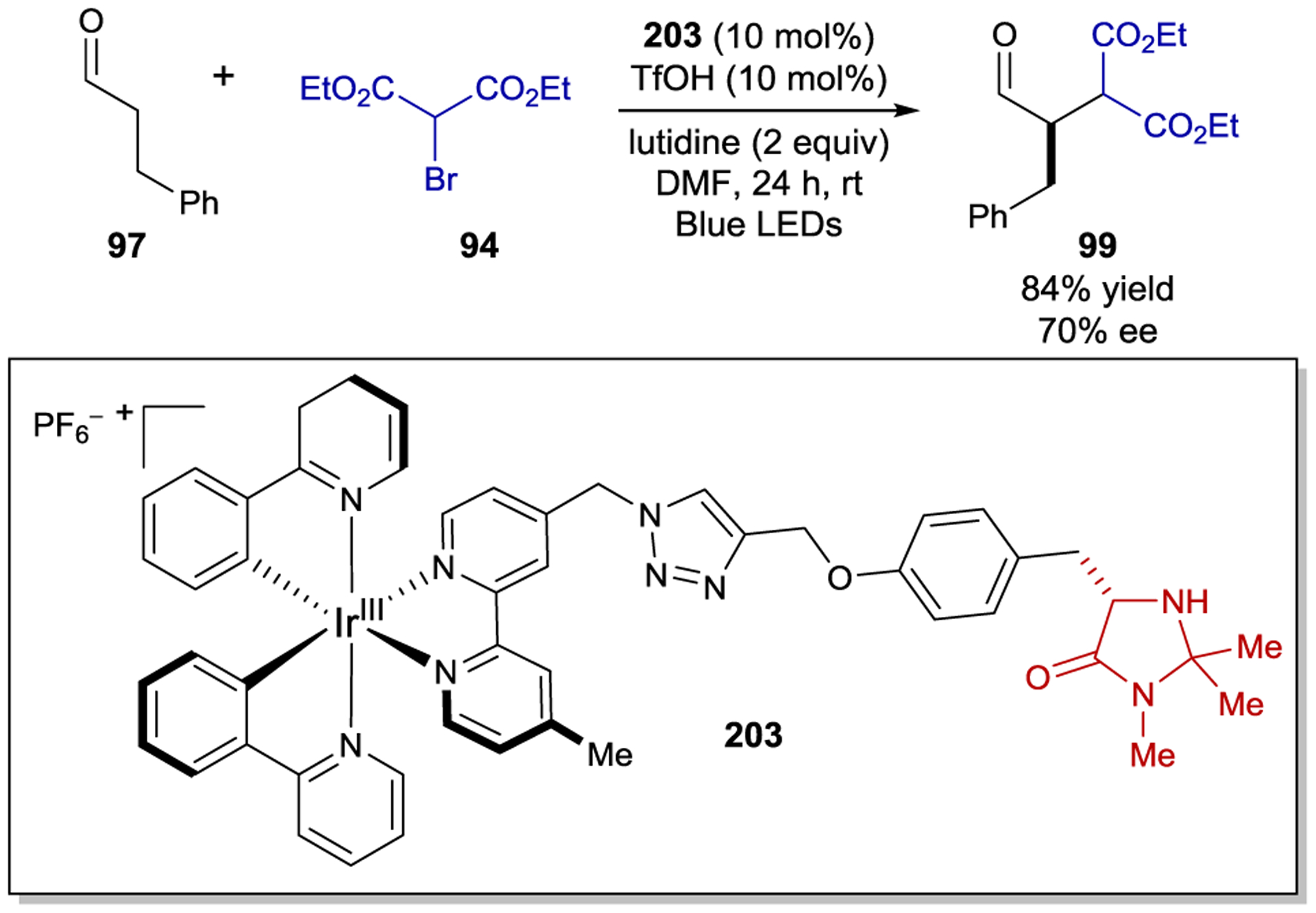

2.2.3. Enamine and Iminium Chromophores

Melchiorre introduced a new strategy in asymmetric photocatalysis in which the light-absorbing species is an electron donor–acceptor (EDA) complex.154, 155 In this strategy, an electron-rich donor molecule and an electron-poor acceptor molecule associate in the ground state, comprising an EDA complex (Scheme 36).156 The photophysical properties of the complex are distinct from the donor or acceptor in isolation. This association leads to the formation of a new charge-transfer absorption band, which at the simplest level can be understood as an intracomplex electron transfer from the donosr HOMO to the acceptor LUMO. In most cases, orbital mixing between the donor and acceptor changes the relative position of the frontier molecular orbitals, stabilizing the formation of the EDA complex. The appearance of color when mixing two colorless compounds is a hallmark of EDA complexes and was the original observation that led Mulliken to formulate the charge transfer theory.157

Scheme 36.

Electron Donor–Acceptor Complex Formation and Excitation

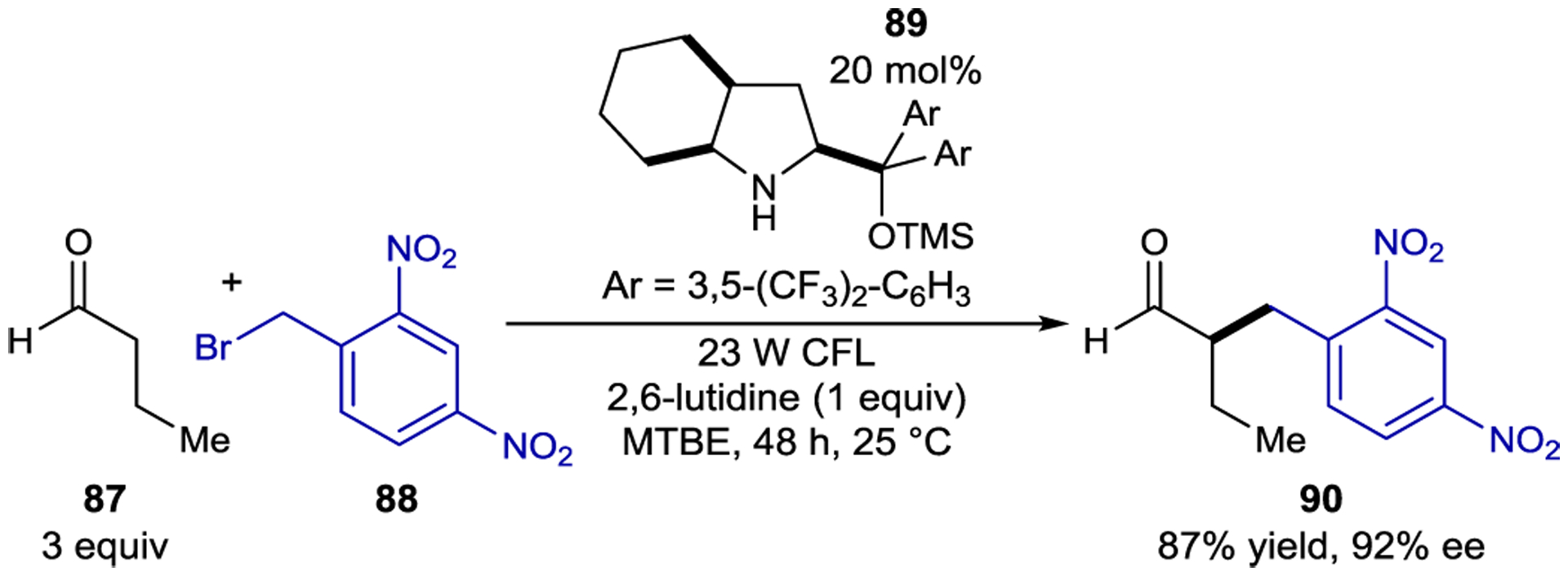

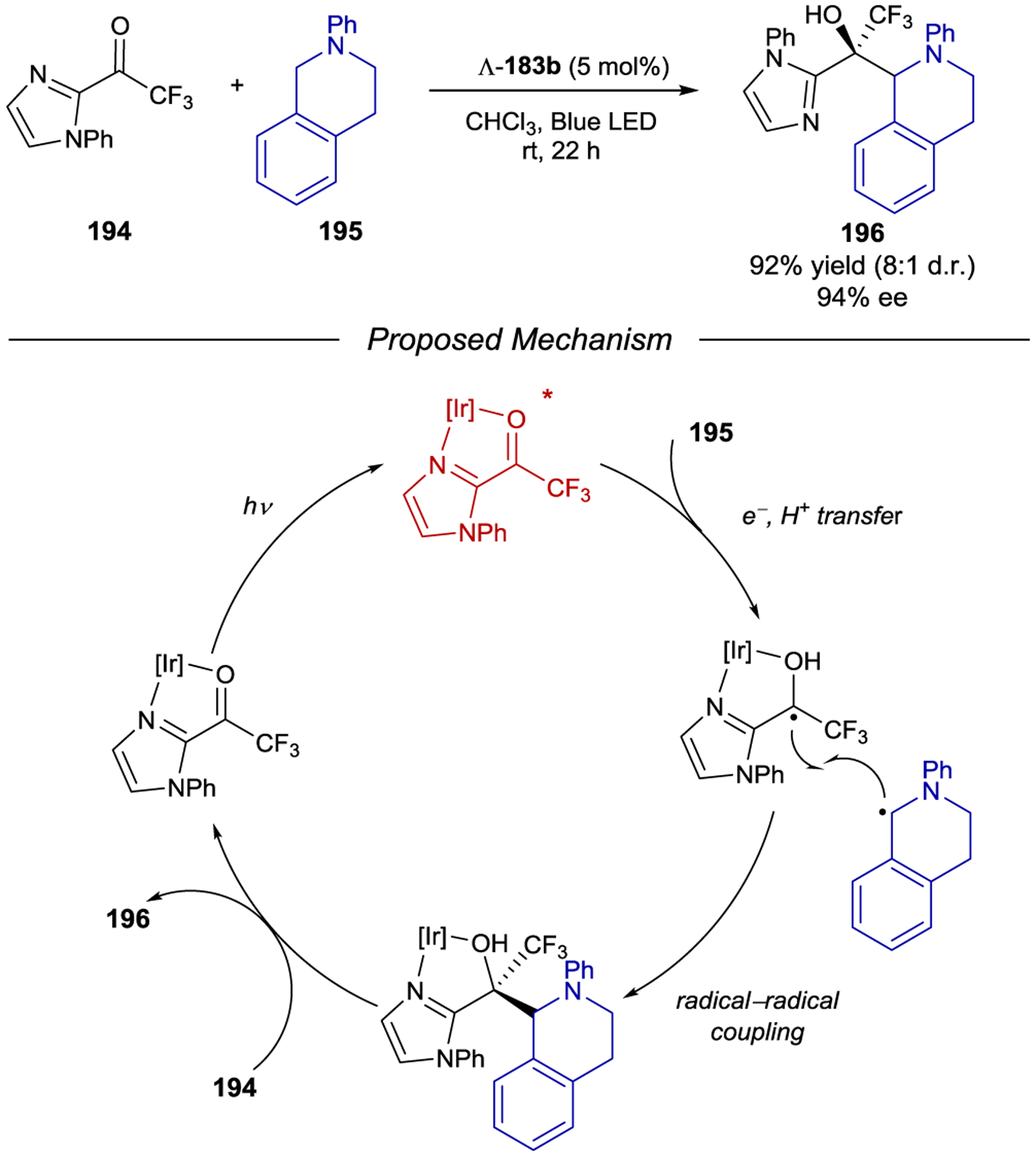

In 2013, Melchiorre exploited this strategy to promote the enantioselective α-alkylation of aldehydes with alkyl halides (Scheme 37).158 This reaction was based on organocatalyzed photoredox reactions developed by MacMillan.159 In both designs, a chiral secondary amine organocatalyst condenses with an aldehyde to form an enamine intermediate. However, unlike the previous organocatalyzed reactions, an exogenous photocatalyst was not needed. Although neither enamine nor alkyl bromide absorb visible light individually, the mixture exhibited a broad absorption feature in the visible region, characteristic of the formation of an EDA complex. Spectrophotometric analyses confirmed the 1:1 ground-state association with an association constant of KEDA = 11.6 determined from Benesi–Hildebrand analysis.160 Upon excitation of the ground-state complex, an electron is promoted from the enamine donor to the alkyl bromide acceptor, forming a radical ion pair (Scheme 38, top). The short-lived radical anion undergoes bromide cleavage to produce an iminium ion and an alkyl radical. The authors first proposed a closed catalytic cycle in which radical-radical recombination forms an iminium intermediate which is then hydrolyzed to afford the α-alkylated product, but further investigations revealed that the quantum yield (Φ) of the reaction with both benzyl and phenacyl bromides is Φ > 20, consistent with a radical chain mechanism.160 Notably, the chiral catalyst is involved in both the photochemical initiation and the ground-state enantiodetermining radical addition into the enamine.

Scheme 37.

Aldehyde α-Alkylation via EDA Complex Excitation

Scheme 38.

Photoinitiated Enamine Catalysis Mechanisms

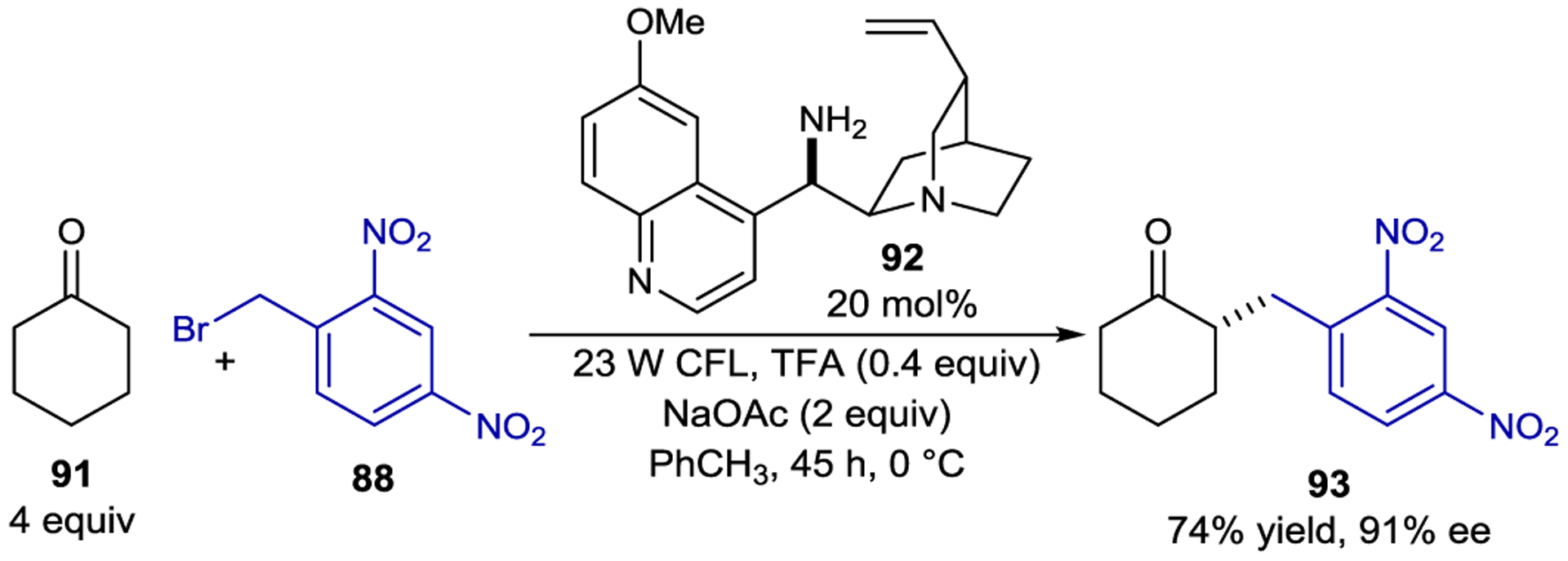

A similar photo-organocatalytic strategy proved applicable to ketone substrates when coupled with cinchona-based primary amine catalyst 92 (Scheme 39).161 Both electron poor benzyl bromides (88) and phenacyl bromides were competent electron acceptors, but the reaction was limited to cyclic ketones as precursors to the chiral enamine electron donors.

Scheme 39.

Ketone α-Alkylation via EDA Complex Excitation

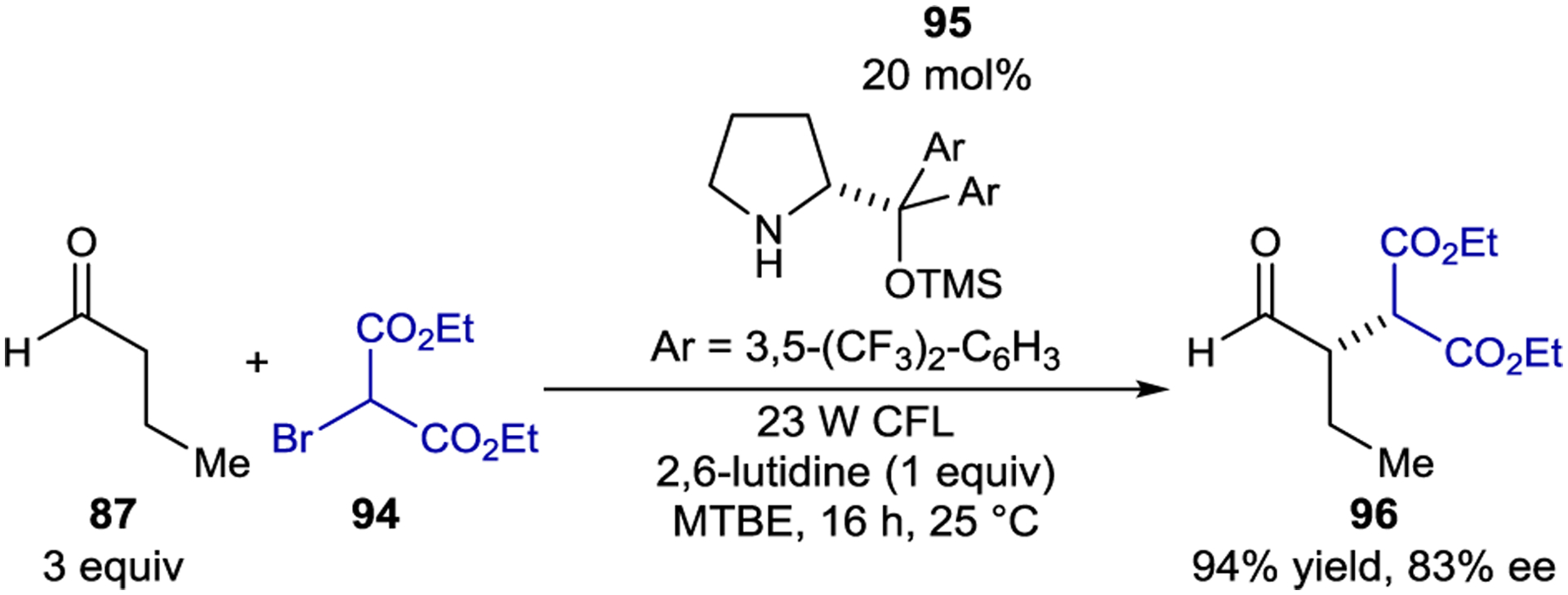

Melchiorre and coworkers also showed that bromomalonates (94) are competent electron acceptors in the α-alkylation of aldehydes (87) and enals using amine organocatalysts (Scheme 40).162 Alkylated products were obtained in up to 94% ee, and complete γ-selectivity was observed in radical addition to enals. The authors initially assumed the intermediacy of an EDA complex between the enamine and bromomalonate; however, no charge transfer band was observed in the UV-Vis absorption spectrum of the mixture. Instead, the enamine was the only reaction component that significantly absorbed light under the optimized conditions. A series of Stern–Volmer quenching studies showed that the bromomalonate quenched the excited-state emission of the enamine. From this study, the authors proposed that PET reduction of the bromomalonate by the excited enamine followed by loss of bromide resulted in the formation of an electrophilic malonyl radical that would subsequently react with another equivalent of ground-state enamine (Scheme 38, bottom). The chain propagation step is likely different than in the EDA reaction because the α-aminoradical is incapable of reducing the bromomalonate. Instead, the α-aminoradical abstracts bromine from another equivalent of bromomalonate. Collapse of the bromoamine intermediate expels bromide, forming an iminium intermediate, which is hydrolyzed to the product. Notably, the photochemical step in both the EDA and PET reactions serves only to initiate the radical chain. Other classes of electron acceptors including (phenylsulfonyl)alkyl iodides were also amenable to the PET reaction.163 After desulfonylation, α-methylation and α-benzylation products could be obtained in high yield and enantioselectivity.

Scheme 40.

Aldehyde α-Alkylation via Direct Enamine Excitation

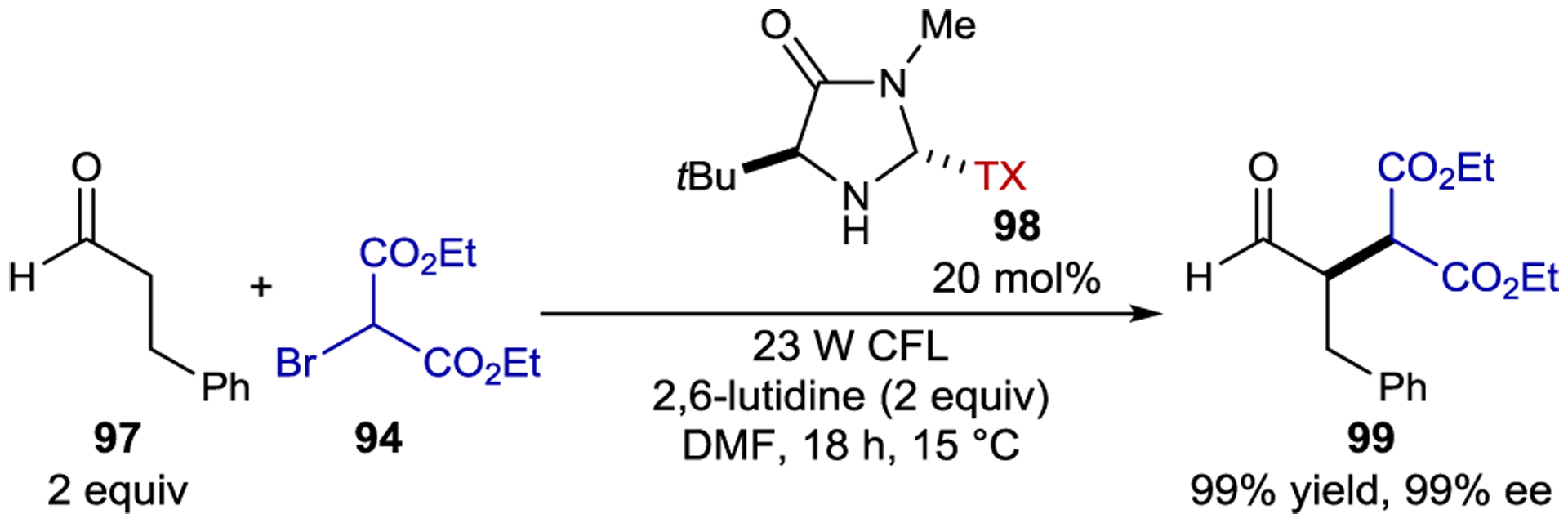

A similar reaction was reported by Alemán with a thioxanthone-substituted organocatalyst (98) yielding alkylated aldehydes in high yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 41). In this case, the bromomalonate is reduced by the thioxanthone catalyst instead of the enamine, initiating the radical chain.164

Scheme 41.

Aldehyde α-Alkylation Promoted by a Bifunctional Photoaminocatalyst

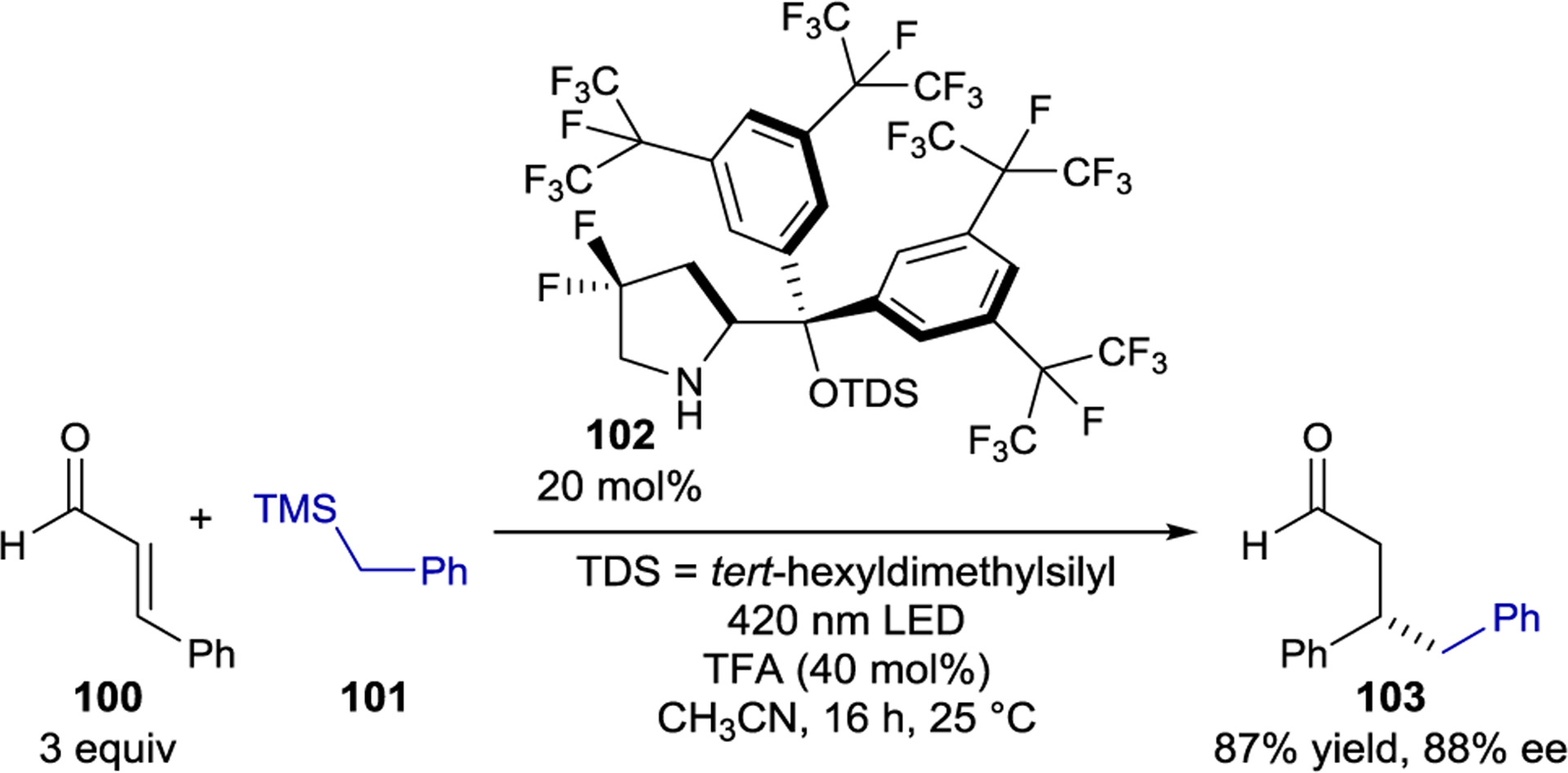

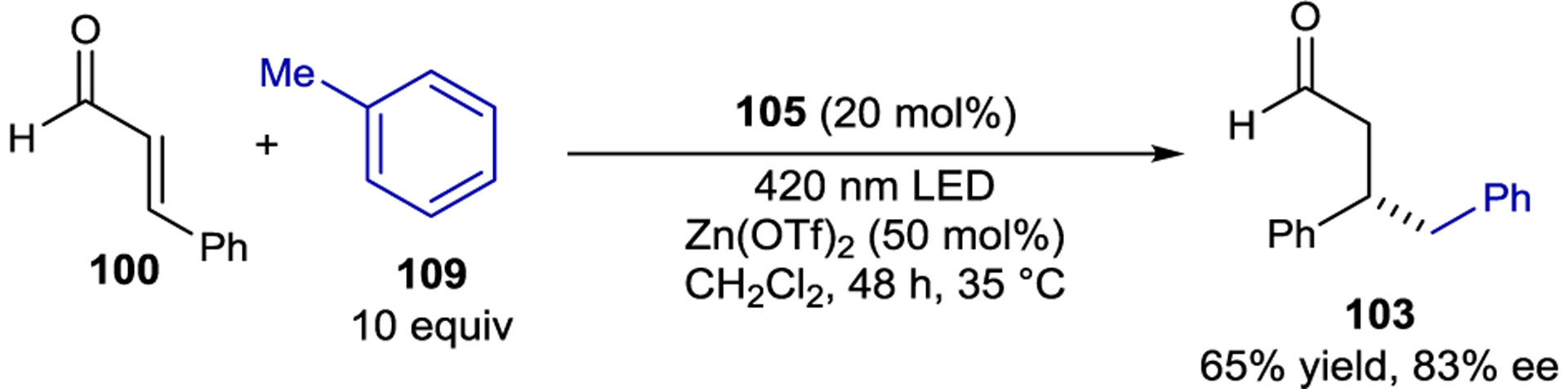

In 2017, Melchiorre and coworkers showed that chiral iminium ions generated in situ by condensation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (100) with chiral amine catalysts (102) could promote the asymmetric β-alkylation of enals (Scheme 42).165 Enamine and iminium photocatalysis are similar yet complementary strategies. Electron-rich enamines are nucleophilic in the ground state and become potent single-electron reductants after photoexcitation. In contrast, iminium ions act as electrophiles in the ground state and are strong oxidants after photoexcitation, allowing the use of complementary radical precursors.

Scheme 42.

Enal β-Alkylation via Direct Iminium Ion Excitation

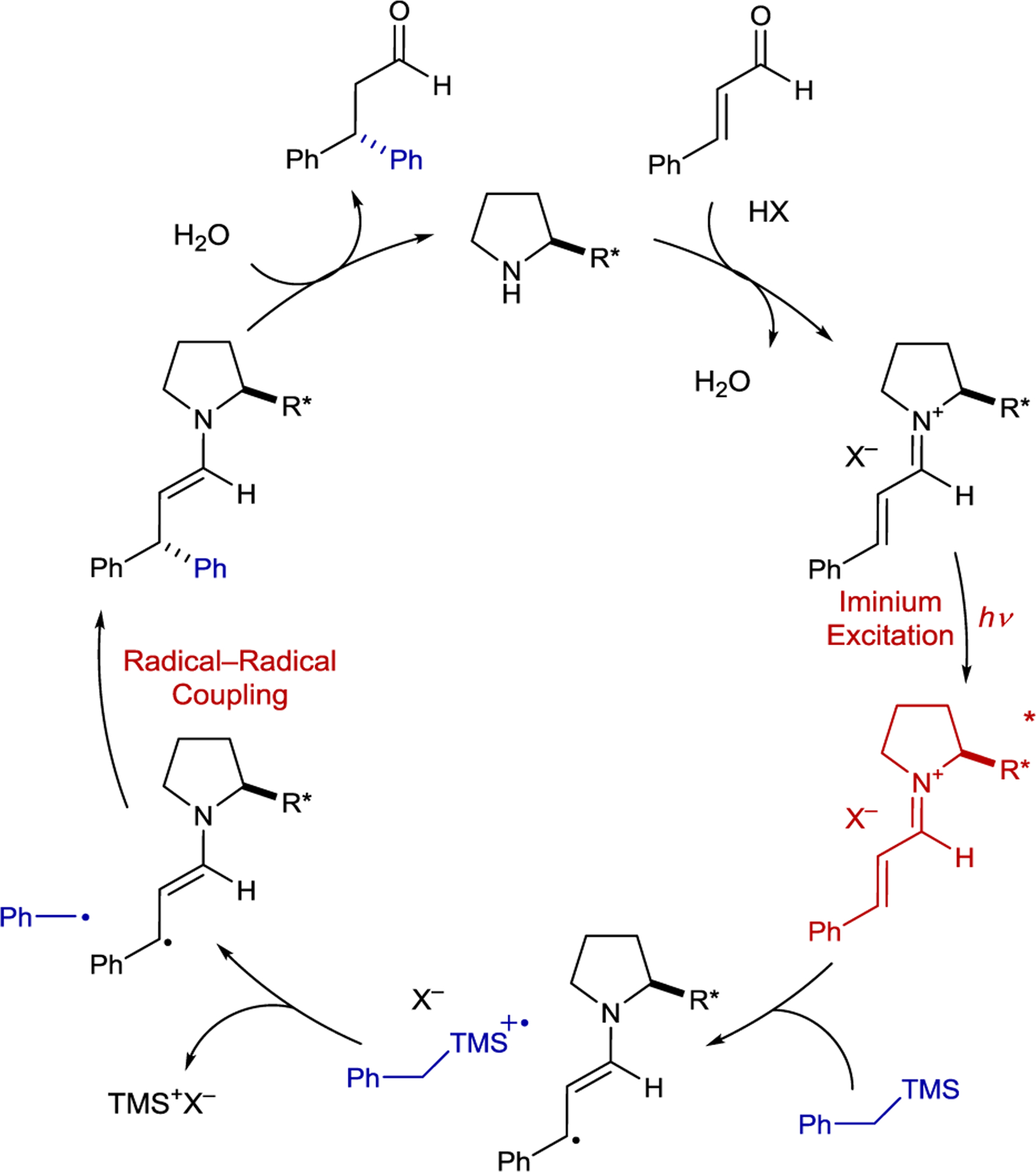

Melchiorre proposed a mechanism in which a chiral iminium ion directly absorbs visible light and functions as a single-electron oxidant to an electron-rich alkyl trimethylsilane (101) (Scheme 43). The silyl radical cation undergoes mesolytic fragmentation to afford a stabilized alkyl radical and trimethylsilyl cation. Coupling of the β-enaminyl radical intermediate with the alkyl radical affords an enamine, which after hydrolysis yields the β-alkylated aldehyde. This radical–radical coupling mechanism was proposed instead of a radical chain mechanism because the putative propagation step, single electron transfer (SET) between the silane and α-iminyl radical cation, would be endergonic. Although this method is limited to benzyl radicals or radicals stabilized by an adjacent heteroatom, unstabilized alkyl radicals could be accommodated when using a dihydropyridine radical precursor.166 This approach gave selective 1,4-addition and offers an advance over thermal iminium catalysis with organometallic nucleophiles, which often produces a mixture of 1,2- and 1,4-addition adducts.

Scheme 43.

Enal β-Alkylation Mechanism

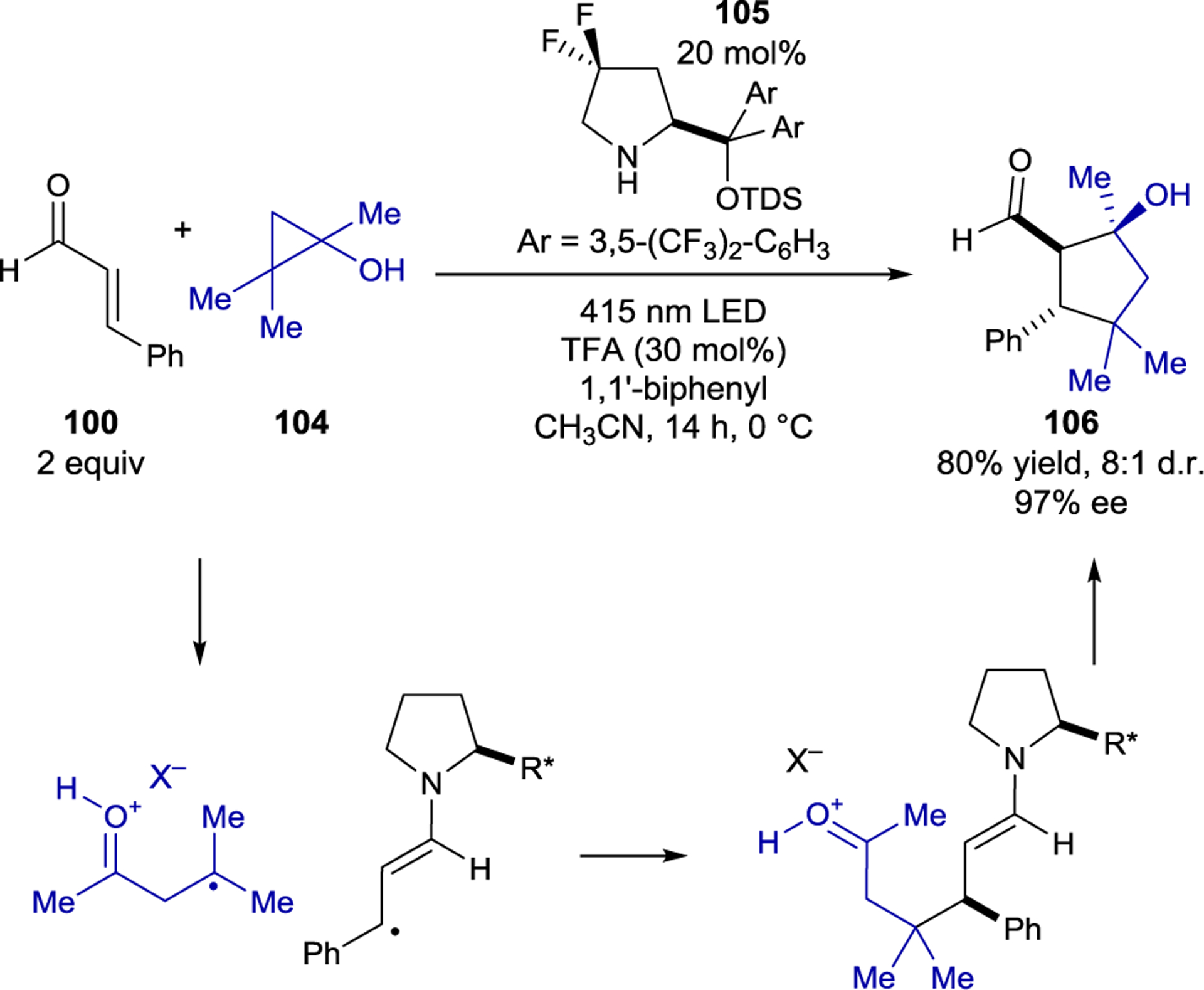

The initial product of a radical–radical coupling under iminium photocatalysis is an enamine, which can further react with an electrophilic moiety if one is present. Melchiorre and coworkers leveraged this insight to design a photochemical cascade reaction in which the excited-state and ground-state reactivity of organocatalytic intermediates were exploited to form cyclopentanols (106) in excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity (Scheme 44).167 Cyclopropanols (104) were used as electron donors, reducing the photoexcited iminium, to generate β-keto radical cation intermediates after ring-opening. In analogy to previous work, stereocontrolled radical–radical coupling affords an enamine intermediate. The ground-state enamine nucleophile cyclizes with the electrophilic ketone in a second stereocontrolled step. A redox mediator, 1,1’-biphenyl, was added to the reaction to increase efficiency. Mechanistic experiments revealed that the excellent enantioselectivity of the reaction arises from a kinetic resolution in the thermal cyclization. The major enantiomer formed in the radical–radical coupling cyclizes quickly, leading to stereochemical amplification over the two steps, while the minor enantiomer does not cyclize.

Scheme 44.

Cyclopentanol Synthesis via Iminium Ion Catalysis

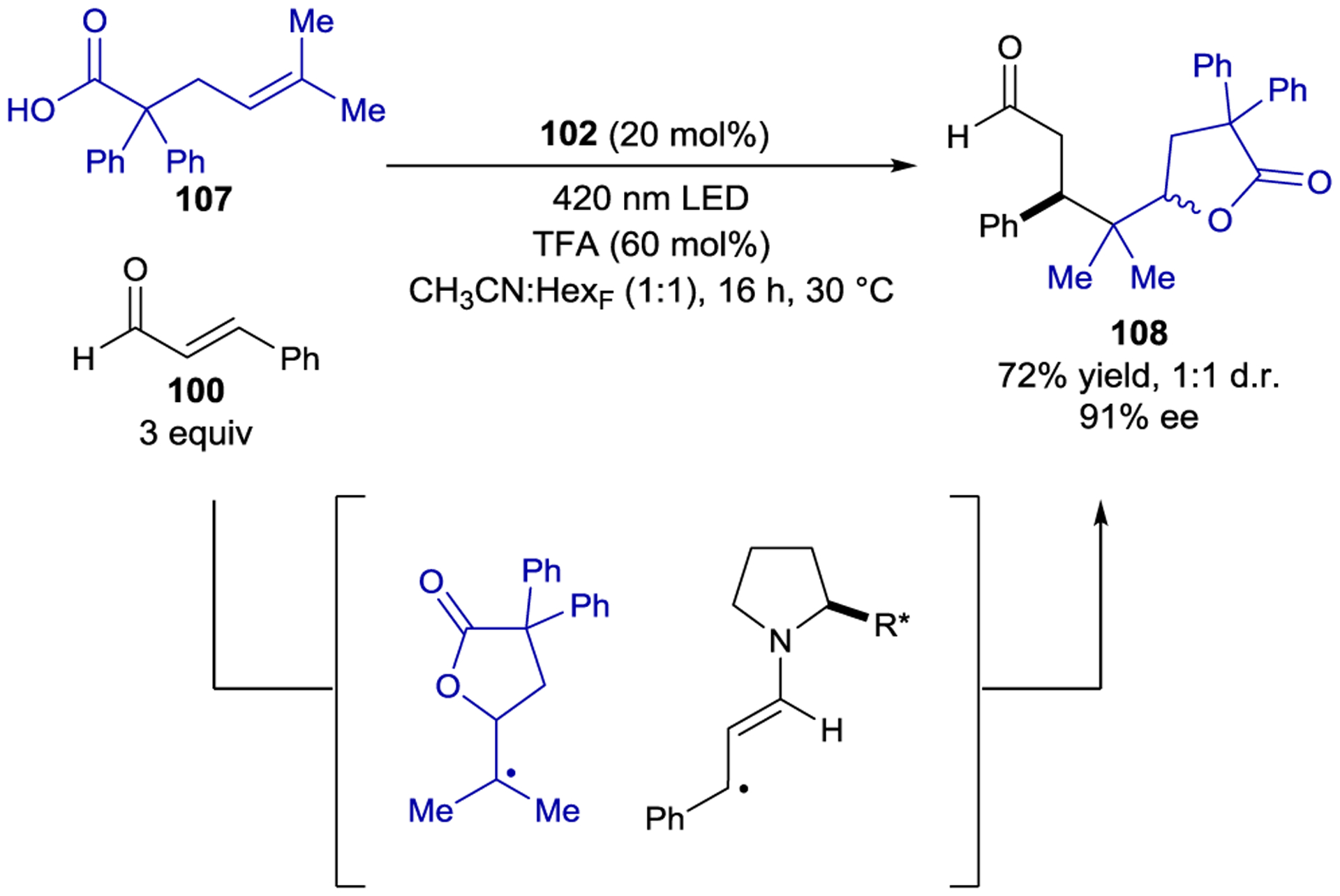

Another example of the cascade strategy enabled the stereoselective construction of complex butyrolactones (108).168 Photoexcitation of an iminium derived from an enal substrate results in oxidation of alkene 107, the appended carboxylic acid moiety of which can cyclize (Scheme 45). Enantioselective radical–radical coupling produces cascade product 108 in high enantioselectivity. Because the first cyclization occurs in the absence of the chiral catalyst, no diastereoselectivity was observed. A similar cascade was subsequently developed with allene-appended carboxylic acids, ultimately yielding bicyclic lactones with moderate enantioselectivity.169

Scheme 45.

Cascade Reaction via Iminium Ion Catalysis

Toluene derivatives also reductively quench the iminium excited state leading to β-benzylated aldehydes from the corresponding enals (Scheme 46).170 Following oxidation of toluene, the benzylic C–H bond is significantly acidified; the pKa is estimated to be −13 in CH3CN.171 Deprotonation results in a benzyl radical that undergoes radical–radical coupling with the β-enaminyl radical intermediate. Zn(OTf)2 was a necessary additive in this process; the Zn2+ cation was proposed to serve as an acid to promote iminium formation, while the triflate counteranion was proposed to deprotonate the photogenerated toluene radical cation.

Scheme 46.

C–H Functionalization of Toluene Derivatives via Iminium Ion Catalysis

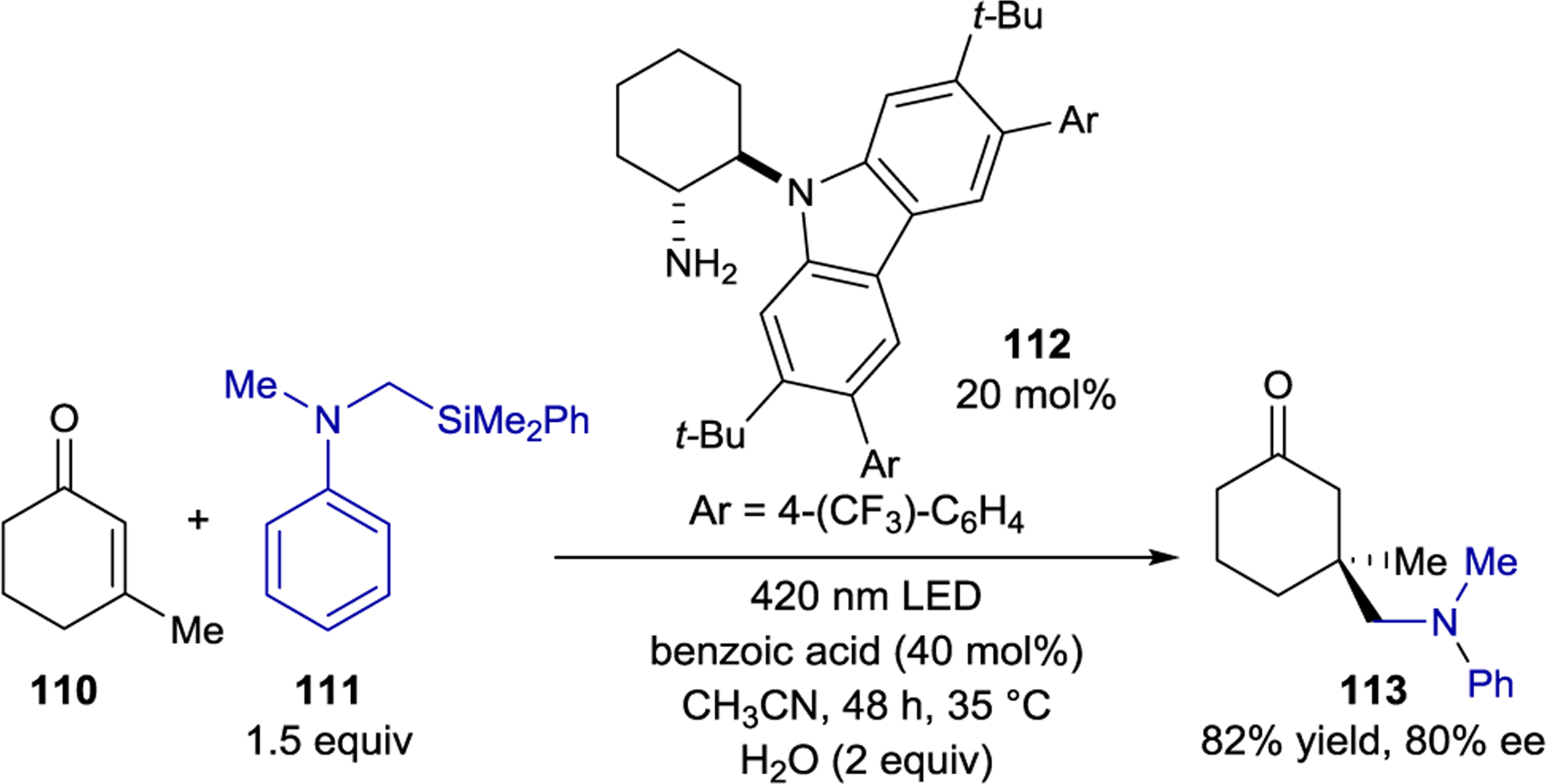

Melchiorre also demonstrated that chiral iminium ions can act as electron acceptors in photocatalytically active EDA complexes (Scheme 47).172 Aliphatic eniminium ions typically absorb in the UV regime (< 400 nm). The iminium produced from condensation of carbazole-functionalized amine 112 and cyclohexanones, however, absorbs strongly in the visible region. This absorption band was assigned as an intramolecular charge transfer between the electron-rich carbazole and electron-poor iminium. Excitation of the intramolecular EDA complex furnishes a carbazole radical cation which oxidizes an α-silyl amine (111). The resulting radical is stereoselectively intercepted by a ground state iminium ion. The overall reaction, which proceeds through a chain mechanism, results in the β-alkylation of enones.

Scheme 47.

EDA Complex Formation with Iminium Electron Acceptors

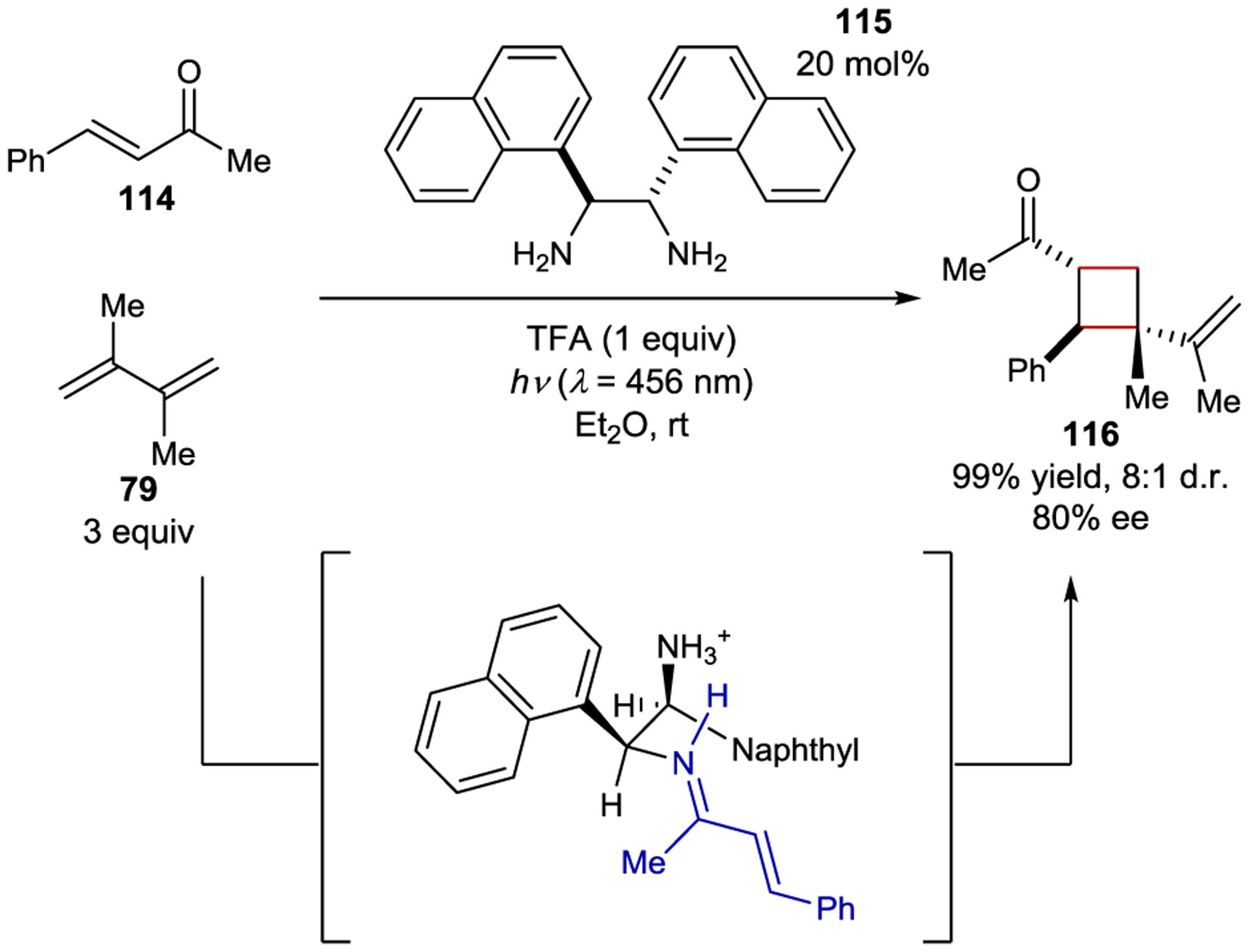

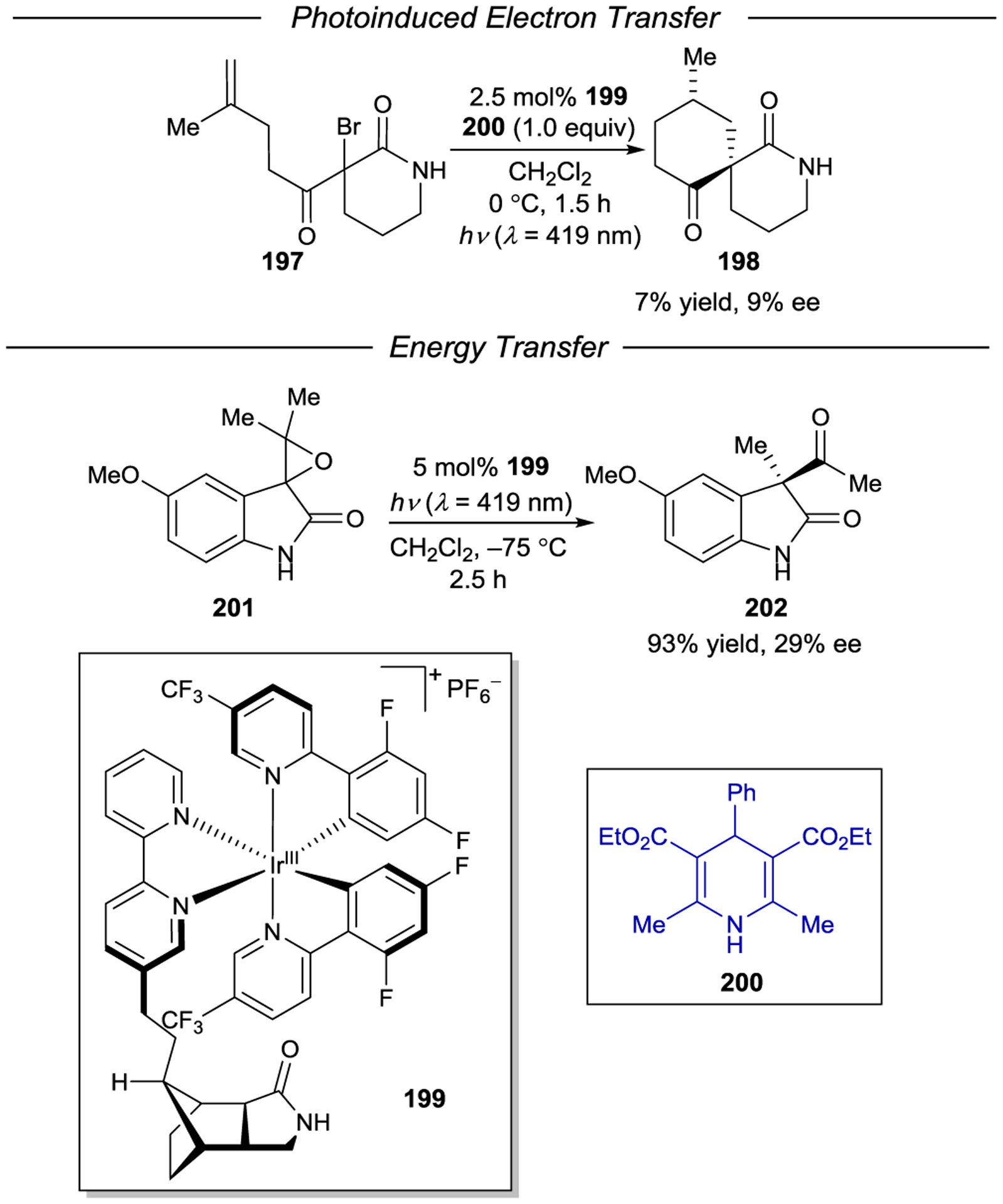

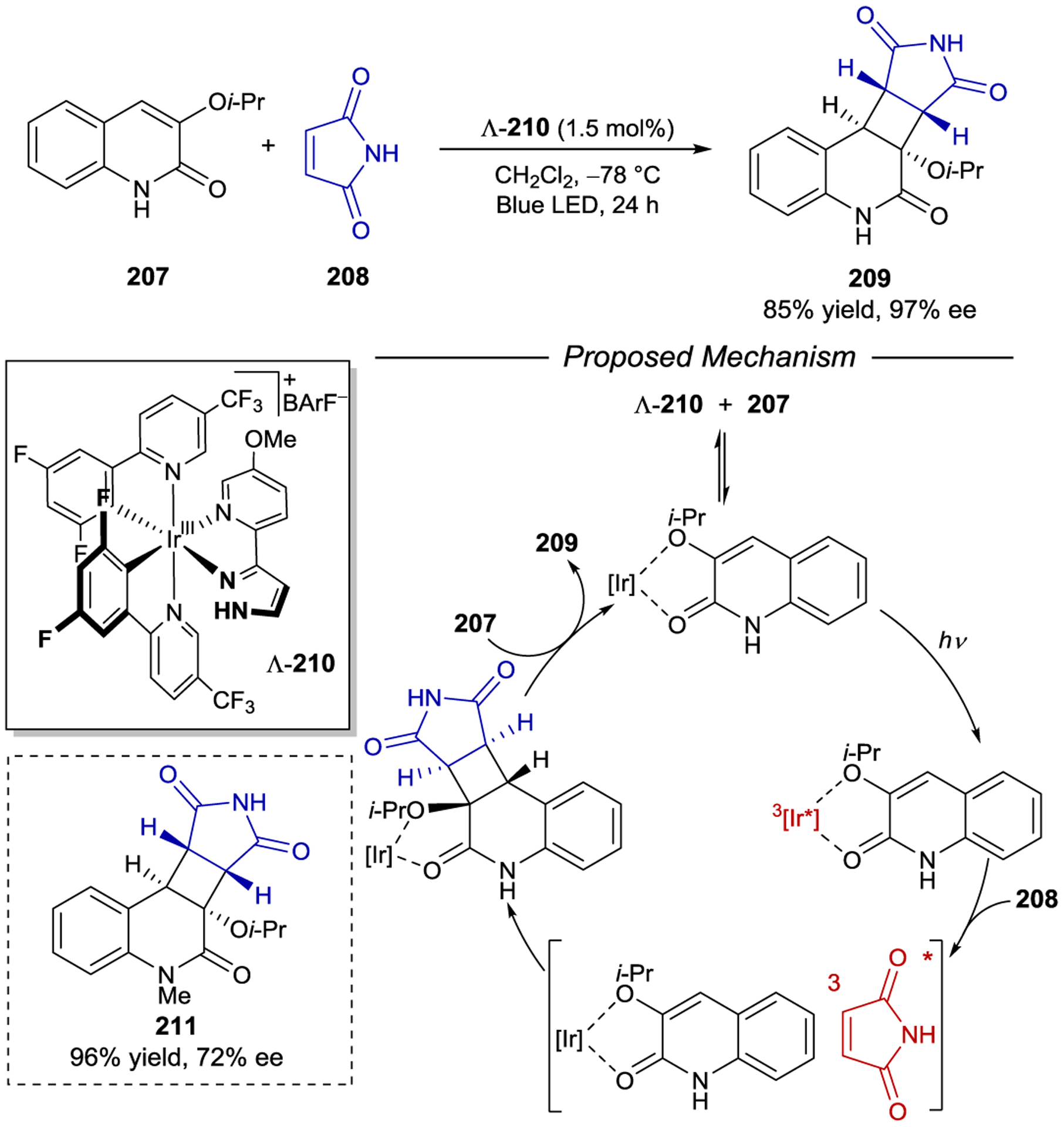

Iminium ion catalysis has also been applied to [2+2] photocycloadditions. The absorption profile of enones features an (n,π*) transition that is red-shifted in comparison to the (π,π*) transition characteristic of analogous iminium species.173 Hence, it can be difficult to minimize the participation of racemic background cycloadditions through direct excitation because the iminium ion cannot be selectively excited. However, the lowest triplet excited state is typically lower in energy for iminium ions than for enones, which could allow for their selective photosensitization. Bach developed an enantioselective [2+2] photoreaction using chiral iminium ions and a Ru triplet sensitizer, but catalysis was inefficient, likely due to competing unproductive electron-transfer quenching of the photocatalyst.174 In 2020 Alemán developed a catalytic enantioselective [2+2] cycloaddition that circumvented the racemic reactivity problem by employing amine catalysts with stereogenic naphthyl substituents (Scheme 48).175 These served as electron donors in an intramolecular EDA complex with the electron-accepting imine. The intramolecular charge-transfer band was sufficiently red-shifted compared to the free enone to allow for its selective excitation. With 20 mol% catalyst 115, cycloadduct 116 was produced in 99% yield and 80% ee. Computational analysis confirmed that the lowest energy transition was the expected charge transfer, while the reactive (π,π*) imine excited state lies slightly higher in energy. The authors proposed that thermal population of the (π,π*) state from the charge-transfer excited state produces an equilibrium population able to undergo the [2+2] cycloaddition. This method was also applied to an intramolecular [2+2] cycloaddition, enabling the synthesis of tricyclic products in high enantioselectivity.176

Scheme 48.

Intermolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition via a Chiral Iminium Chromophore

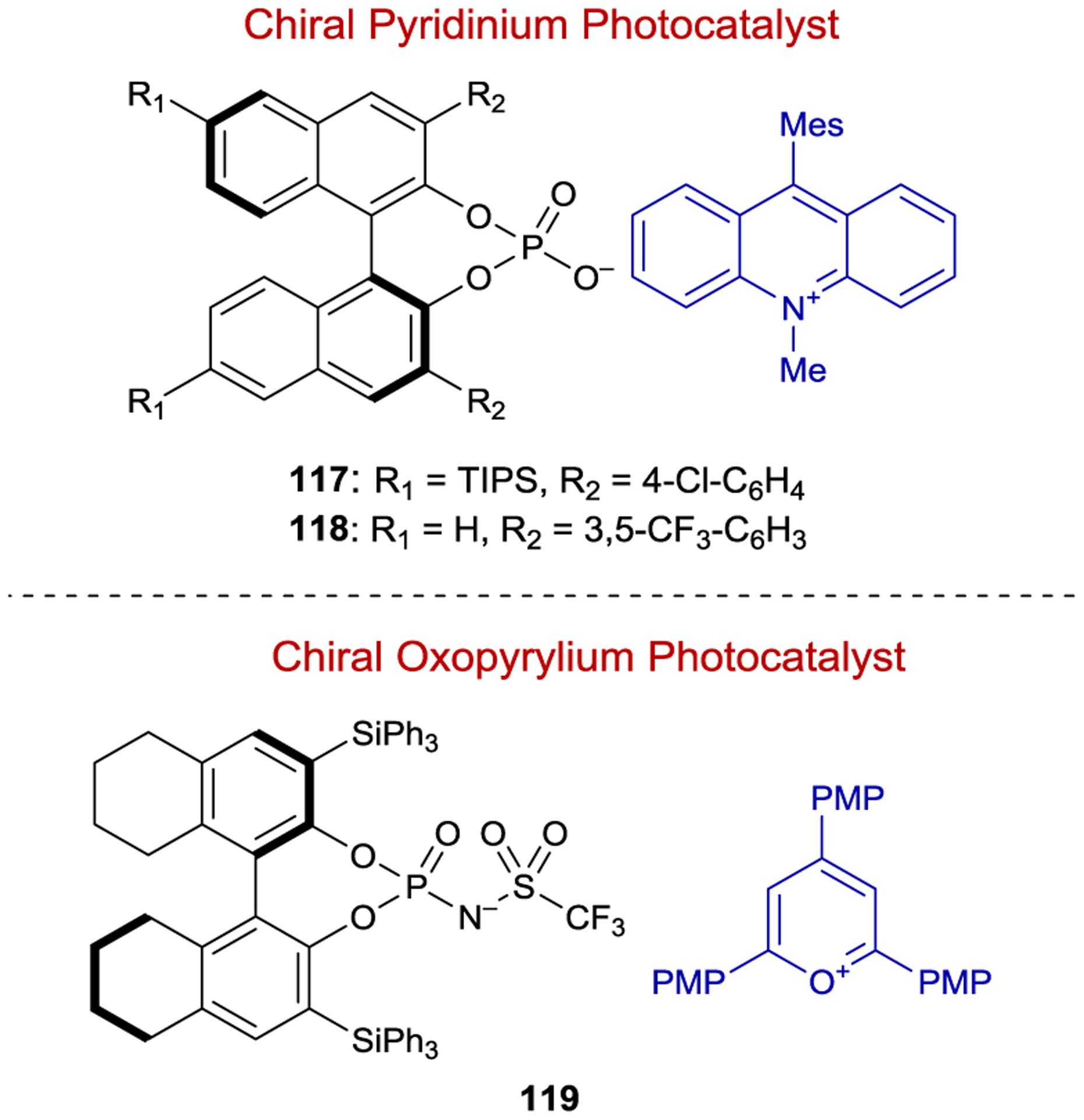

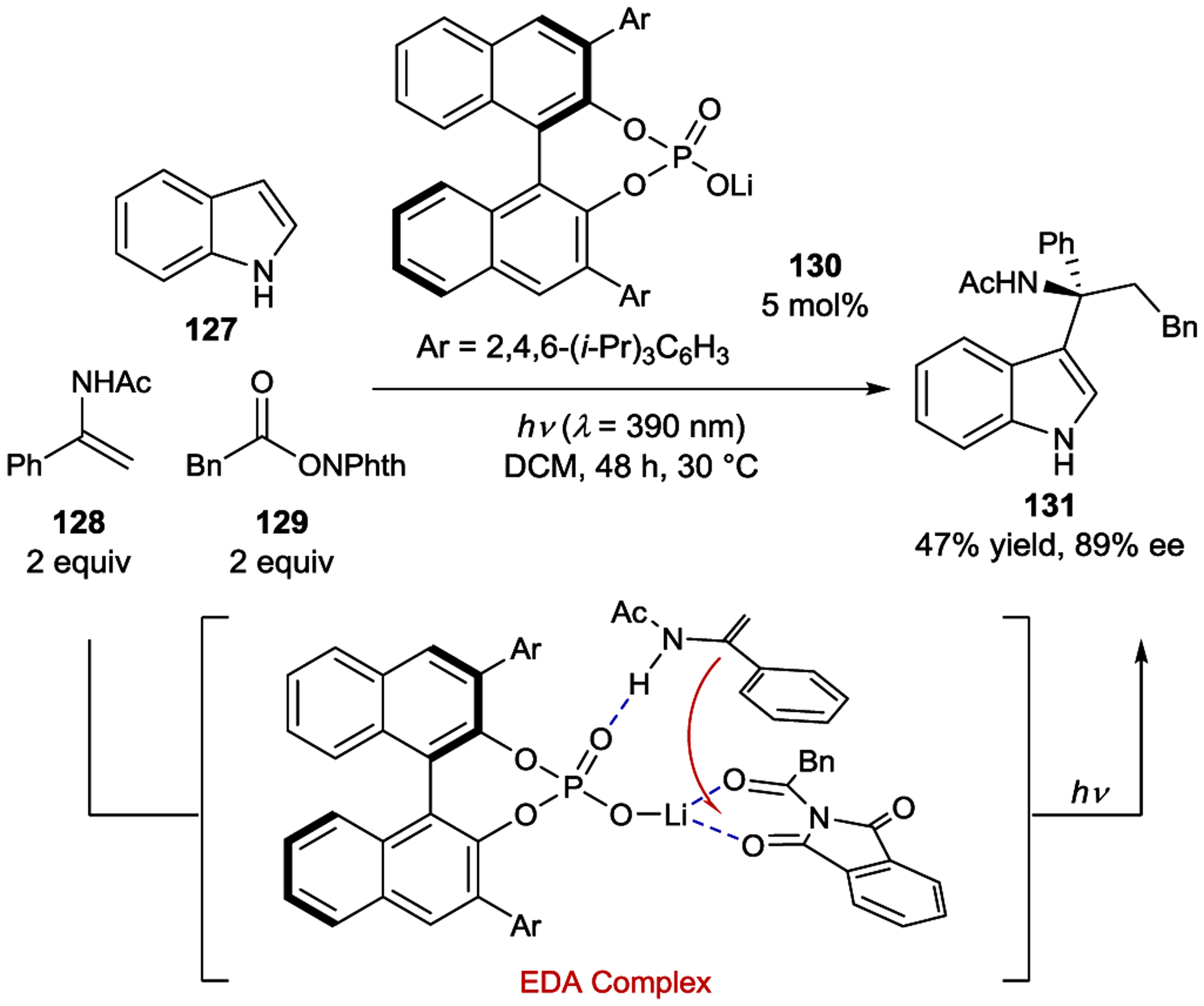

2.2.4. Chiral Counterions

Recently, several groups have attempted to apply chiral anion catalysis to asymmetric photochemistry.177, 178 Chiral anions are intriguing for applications in photoredox chemistry because they can associate with any cationic intermediate through electrostatic interactions, circumventing the need for specific substrate binding moieties such as carbonyls. Further, many of the most common organic and inorganic photoredox catalysts are cationic, offering a conceptually straightforward means to incorporate a chiral counteranion structure into an asymmetric photoredox reaction (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Photocatalysts with Chiral Counteranions

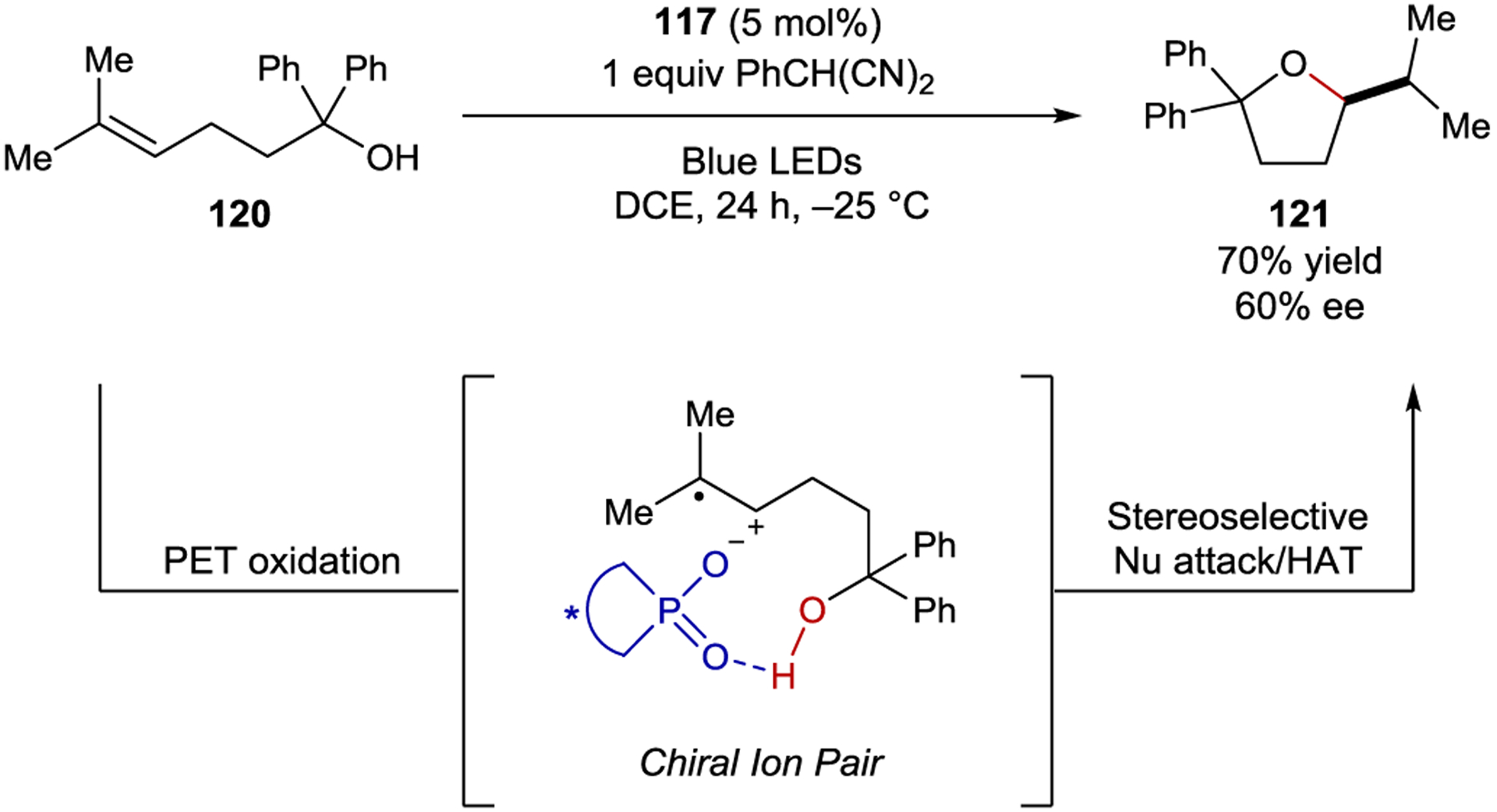

Luo demonstrated the feasibility of this approach by developing an asymmetric version of the anti-Markovnikov hydroetherification originally reported by Nicewicz.179, 180 Under the optimized conditions an acridinium photocatalyst with a BINOL-derived phosphate counteranion (117) afforded cyclic ether 121 in 60% ee (Scheme 49). The reaction proceeds through initial oxidation of alkene 120 to the radical cation, which pairs with the chiral anion, followed by enantiodetermining nucleophilic attack of the pendant alcohol. Hydrogen atom transfer from 2-phenylmalononitrile to the resulting carbon-centered radical yields the cyclic ether product.

Scheme 49.

Hydroetherification via Chiral Ion-Pairing Catalysis

Other stereoselective radical cation photoreactions have utilized chiral phosphonate counteranions. Tang examined chiral acridinium catalyst 118 in a [3+2] cycloaddition between 2H-azirine 122 and azodicarboxylate 123; however, the 1,2,4-triazoline product (124) was only formed in 20% ee (Scheme 50).181

Scheme 50.

[3+2] Cycloaddition via Chiral Ion-Pairing Catalysis

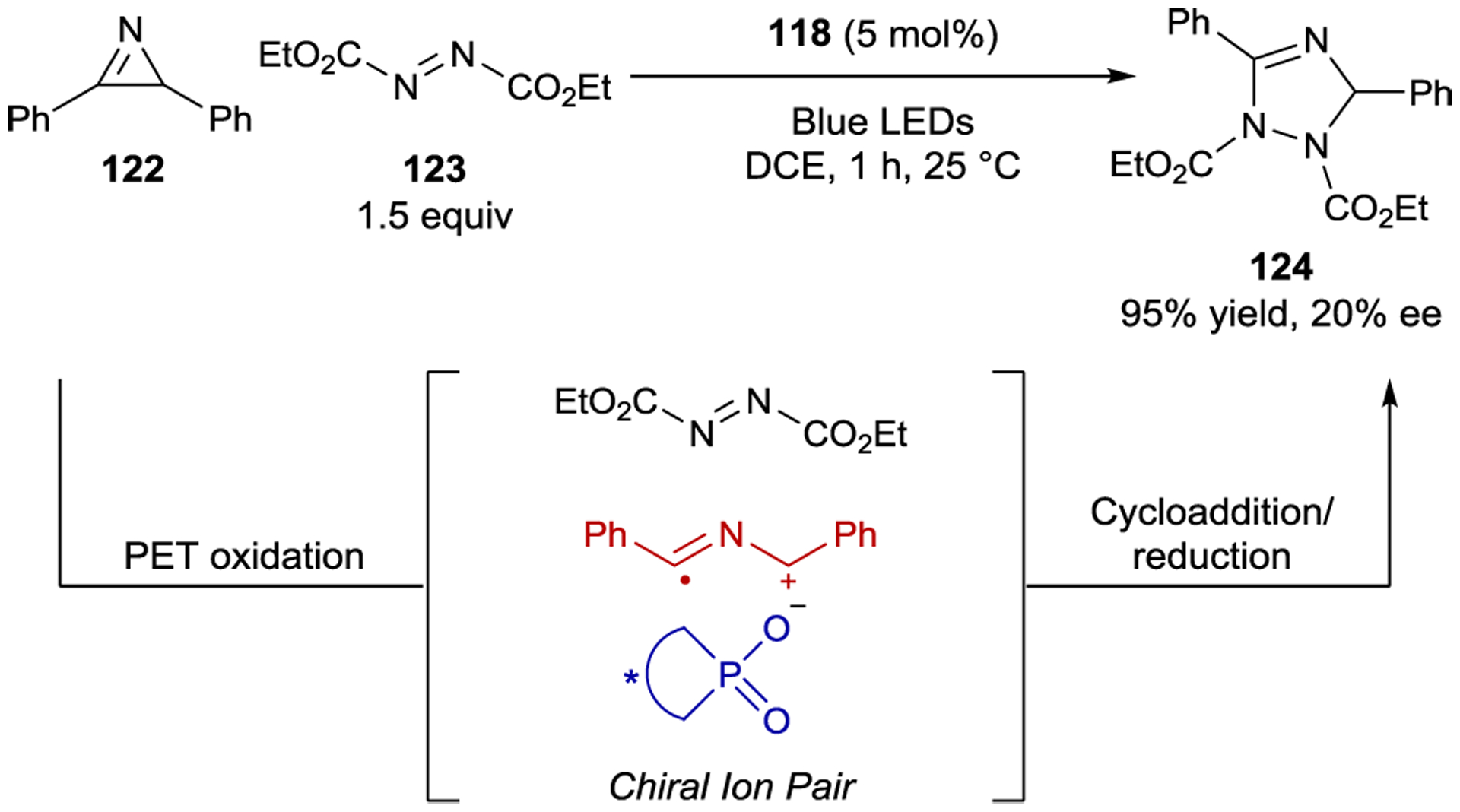

Nicewicz examined a range of BINOL-derived chiral anions with an oxopyrylium photocatalyst in a radical-cation Diels–Alder reaction, with a maximum selectivity of 50% ee with catalyst 119 (Scheme 51).182 When screening solvents, the authors observed an inverse relationship between enantioselectivity and solvent dielectric constant, consistent with the hypothesis that an intimately interacting ion pair is critical for asymmetric induction. The generally modest enantioselectivities reported to date using this strategy reflect its early stage of development.

Scheme 51.

Diels–Alder Cycloaddition Catalyzed by an Oxopyrylium Sensitizer

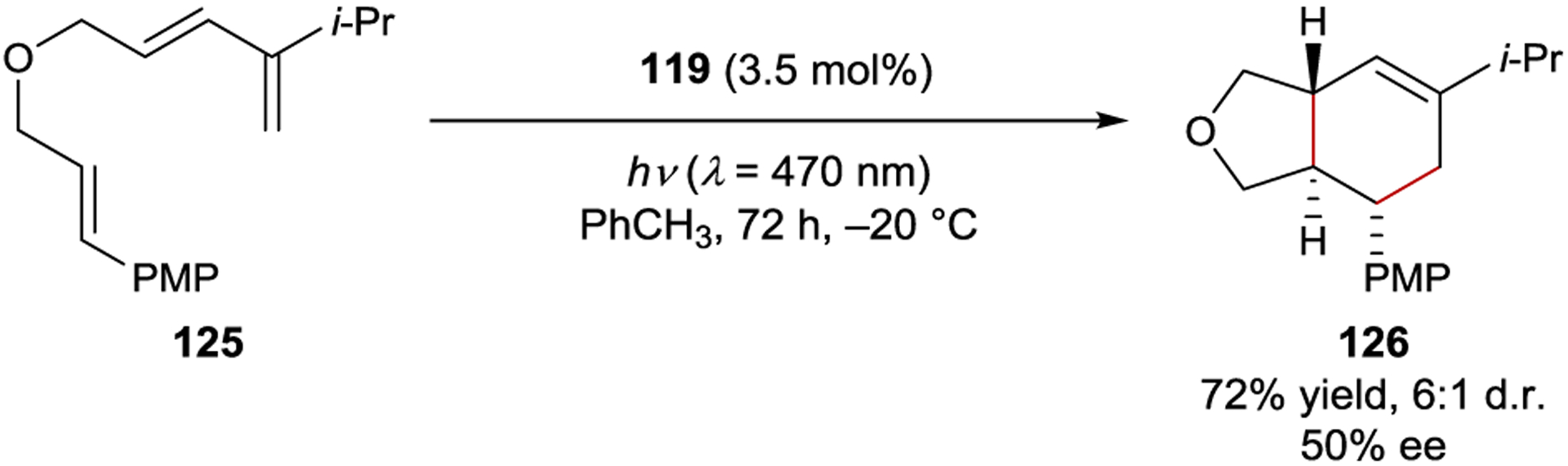

Wang developed an asymmetric dicarbofunctionalization of enamides that proceeded in both the presence and absence of a ruthenium photosensitizer (Scheme 52).183 In the absence of a photosensitizer, indole 127, enamide 128, and redox-active ester 129 were coupled in the presence of a chiral phosphate base to form 131 in 47% yield and 89% ee. A Job plot analysis indicated a ground-state preorganization of the phosphate base, enamide 128 and ester 129 into an EDA complex. Photoexcitation of this EDA complex led to reduction of the redox-active ester followed by rapid decarboxylation. The formed benzyl radical and enamide-derived radical combine to form an iminium intermediate. In the presence of the phosphate catalyst, indole 127 then attacks the electrophilic iminium cation via a Friedel–Crafts reaction to provide enantioenriched indole 131.

Scheme 52.

Dicarbofunctionalization of Enamides via Ion-Pairing Catalysis

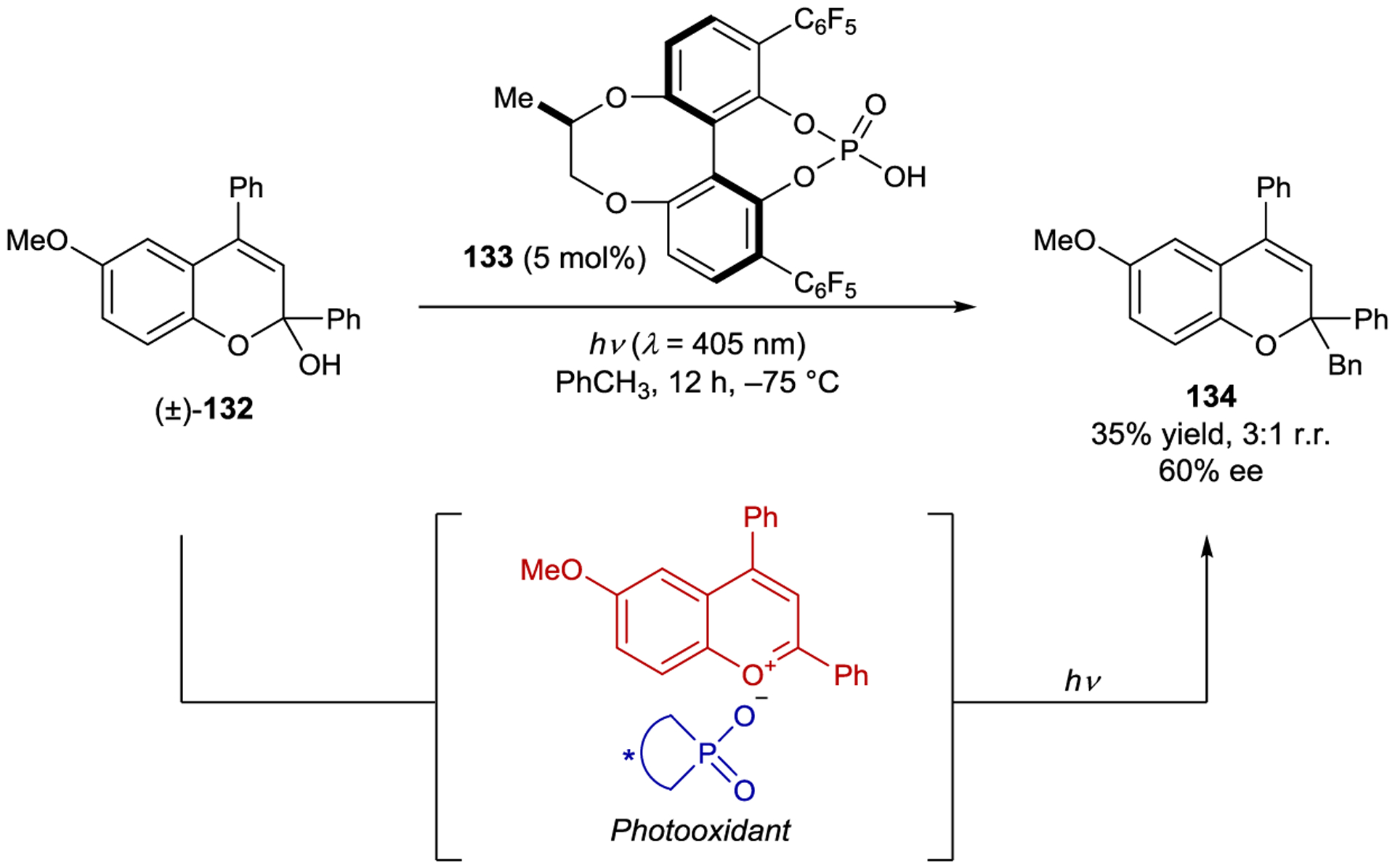

Terada reported the radical addition of toluene-derived radicals to benzopyrylium intermediates to generate chromene derivatives (Scheme 53).184 Protonation of chromenol 132 by phosphoric acid 133 produces a photoactive benzopyrylium intermediate that can photooxidize toluene. Upon deprotonation, the resulting toluyl radical undergoes addition to another equivalent of benzopyrylium. Reduction of the radical adduct by the reduced benzopyrylium affords the product and regenerates the photooxidant. Because the radical addition occurs in the presence of the conjugate base of the acid, the authors tested chiral phosphoric acid 133 in an enantioselective reaction, obtaining 134 in 60% ee.

Scheme 53.

Toluene Functionalization via Excitation of Benzopyrylium Intermediates

Finally, Melchiorre developed an asymmetric perfluoroalkylation of β-ketoesters exploiting an EDA complex activation strategy (Scheme 54).185 In the presence of base and cinchona-derived phase transfer catalyst 137, β-ketoester 136 is converted to the corresponding enolate with a chiral countercation. The electron-rich enolate forms a ground-state association with an electron-poor perfluoroalkyl iodide (135) constituting an EDA complex. After excitation of the EDA complex and cleavage of the alkyl iodide, the pefluoroalkyl radical is proposed to be trapped by another equivalent of the enolate in the enantiodetermining step. The resulting ketyl radical abstracts an iodide from a perfluoroalkyl iodide, regenerating the alkyl radical and propagating a radical chain. Finally, the iodide adduct collapses to form the product. Subsequent computational studies suggested that multiple hydrogen-bonding interaction between the enolate and catalyst account for the high enantioselectivity.186 This work is notably distinct from previous photo-organocatalyzed reports. In prior work the chiral catalyst was covalently bonded to the substrate in the enamine intermediate, while in this study the catalyst is ion paired to the enolate electron donor.

Scheme 54.

Perfluoroalkylation of Enolates via Ion-Pairing Catalysis

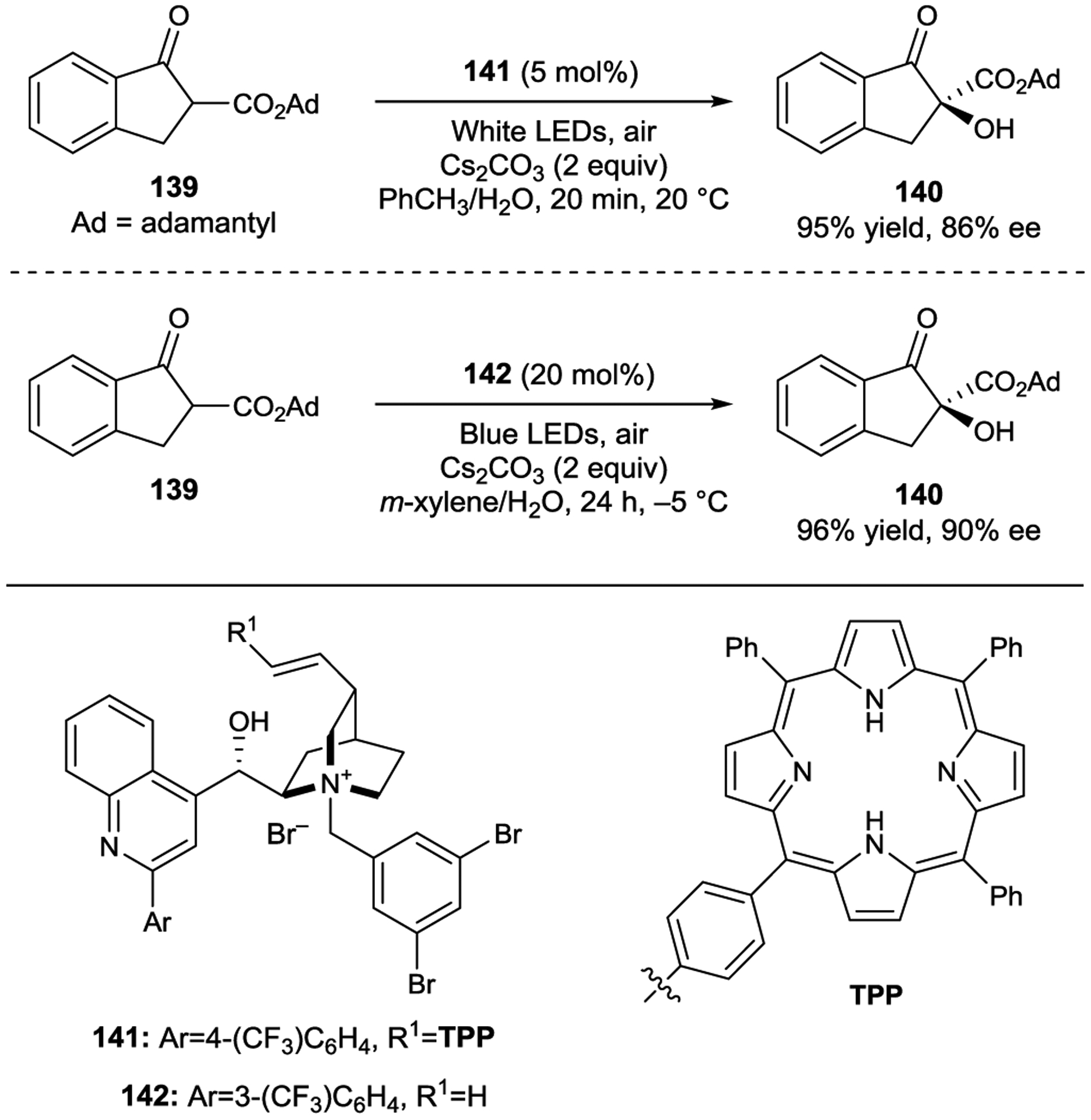

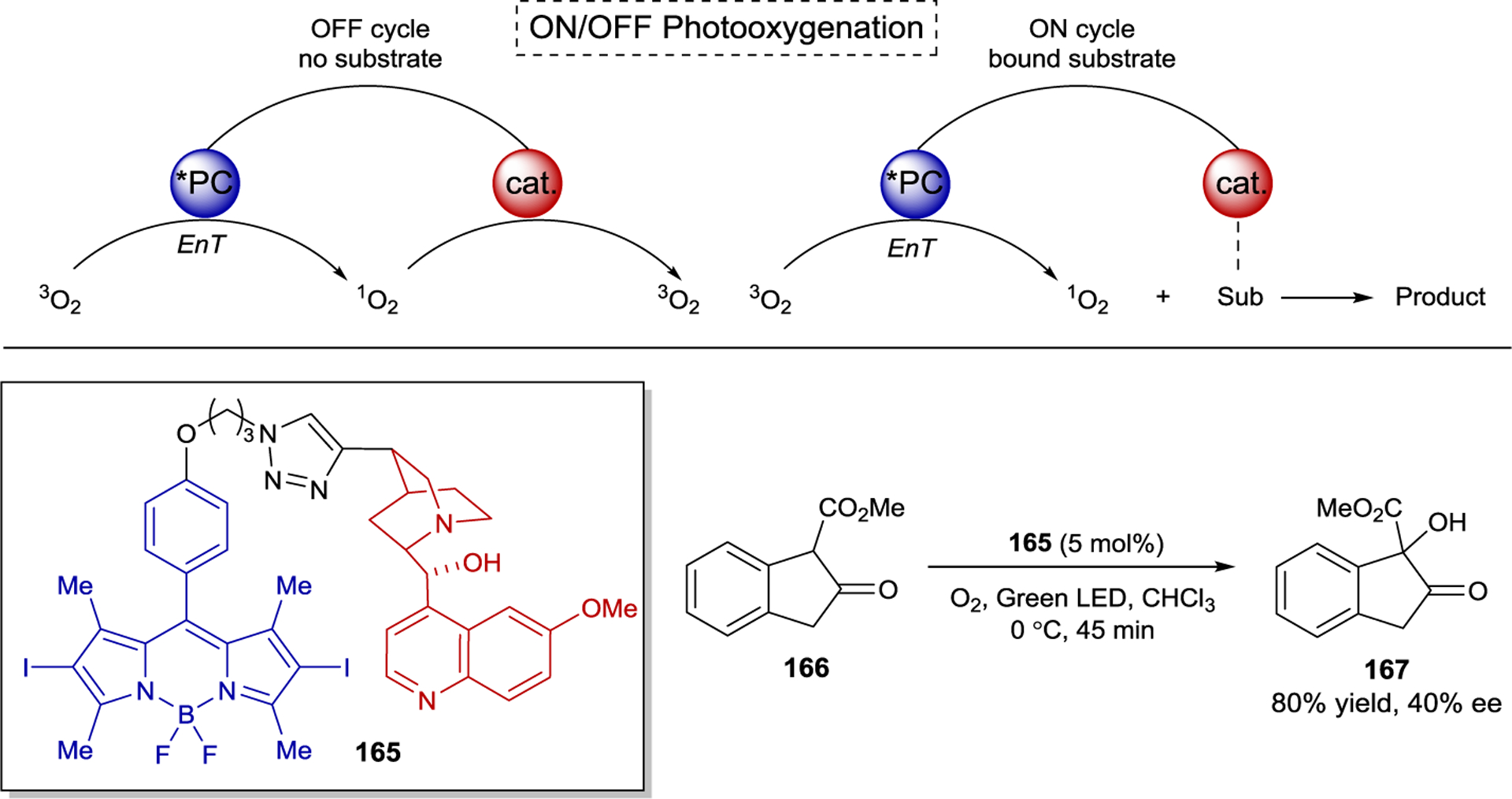

In 2018, Meng showed that a cinchona-derived catalyst (141) tethered to a photocatalyst promotes β-ketoester oxidation via sensitization of oxygen in up to 86% ee (Scheme 55).187 In 2019 the same group discovered that the reaction also proceeds with a similar catalyst lacking the photosensitizing unit (142).188 As in the Melchiorre precedent above, an EDA complex was proposed between the deprotonated substrate enolate and the catalyst. The authors proposed that the excited EDA complex sensitizes oxygen, which then reacts with the enolate, eventually affording the hydroxylated product. The reaction was also performed in a flow photomicroreactor where the product was obtained in similar yield and enantioselectivity in under 1 h.

Scheme 55.

Aerobic Oxidation of β-Ketoesters via Ion-Pairing Catalysis

3. Chiral Inorganic Chromophores

3.1. Boron

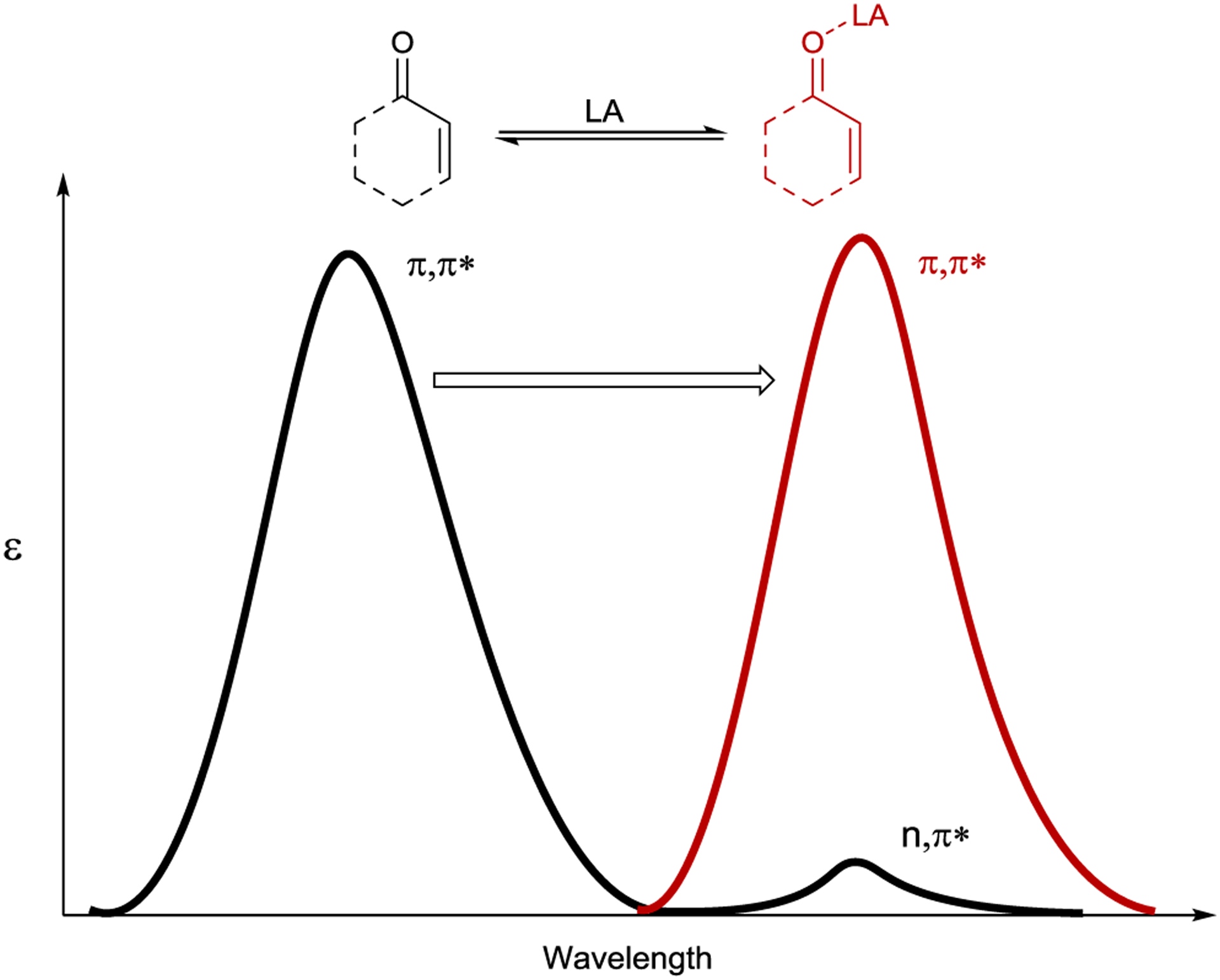

Lewis acids have been studied extensively for their ability to influence the outcomes of a wide range of ground-state transformations. Their effect on photochemical reactions has received considerably less attention. In 1910, Praetorius and Korn described a uranyl chloride accelerated [2+2] photodimerization of α,β-unsaturated ketones.189 Alcock later showed that SnCl4 exhibits a similar effect, suggesting that many Lewis acids might have a general effect in photochemical transformations.190 In more recent work, Lewis and Barancyk performed a detailed study of the Lewis acid promoted [2+2] photocycloaddition of coumarin with 2,3-dimethyl-2-butene.191, 192 While little product was formed in the absence of Lewis acid, addition of 50 mol% of various Lewis acid catalysts led to a large enhancement of product formation. The most active catalyst tested was AlBr3, which yielded complete conversion to the cycloadduct. Mechanistically, Lewis proposed that the binding of a Lewis acid alters the electronic structure of the enone, which in the case of coumarin manifests as a bathochromic shift in the complex’s absorption profile (Scheme 56).

Scheme 56.

Bathochromic Shift of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyls upon Lewis Acid Coordination

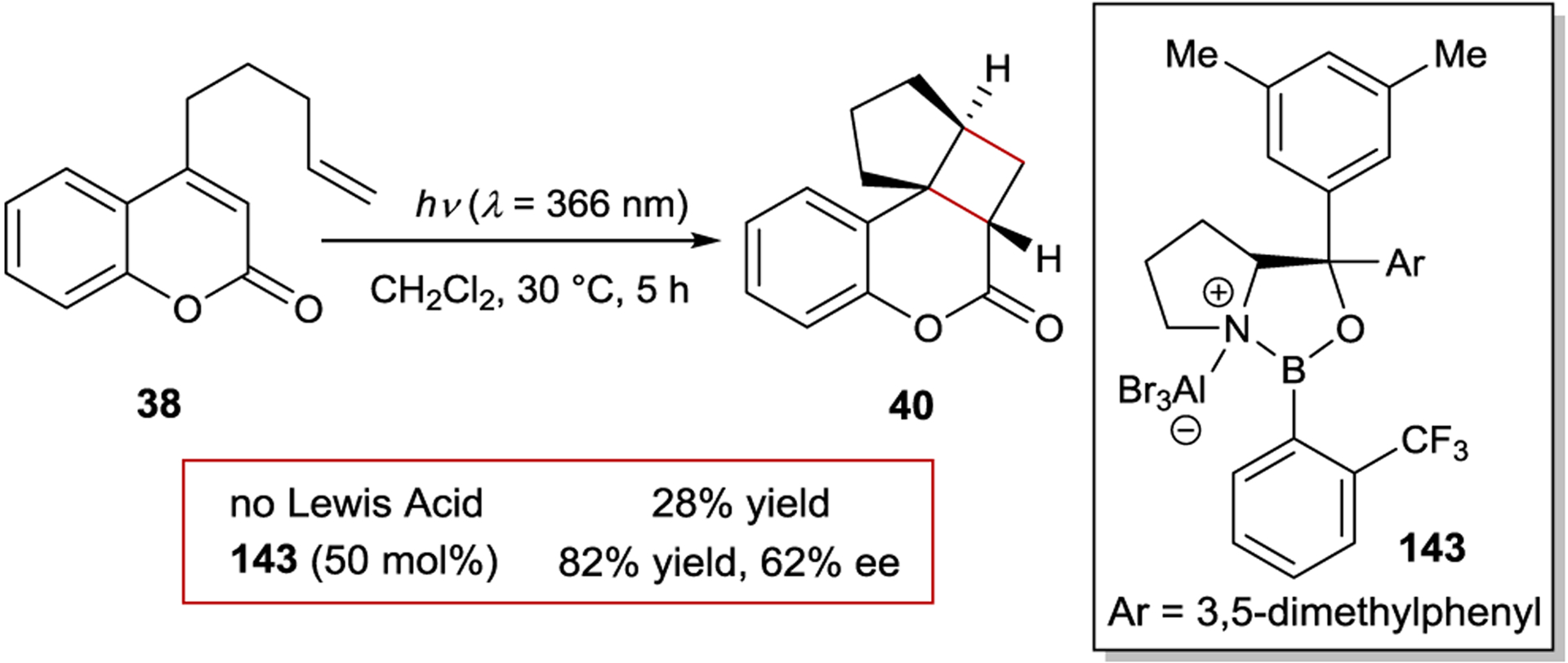

Bach has described this phenomenon as “chromophore activation”193, 194 and proposed that it could be exploited in the design of Lewis acid catalyzed asymmetric photoreactions. Irradiation at wavelengths that maximize the selective photoexcitation of a chiral catalyst–substrate complex over the free α,β-unsaturated carbonyl in solution ensures that reaction occurs within the chiral environment of the Lewis acid, while minimizing direct racemic photoreaction. The initial report demonstrating the feasibility of this concept examined the intramolecular photocycloaddition of coumarin 38 (Scheme 57).195 The reaction proceeds sluggishly upon irradiation at 366 nm due to the low extinction coefficient of the coumarin. In line with the proposed chromophore activation mechanism, addition of simple boron or aluminum Lewis acids red-shift the (π,π*) absorption, greatly accelerating product formation upon irradiation, highlighting that Lewis acids can indeed increase photoreaction rates. Moreover, the use of chiral oxazaborolidine Lewis acid 143 provides the cycloadduct in 82% yield and a remarkable 62% ee, which could be increased to 82% ee at −75 °C.196 At lower concentrations (20 mol%) of oxazaborolidine catalyst 143, however, the ee was diminished due to direct excitation of the weak (n,π*) absorption of free coumarin.

Scheme 57.

Enantioselective [2+2] Photocycloadditions of Coumarins with a Chiral Oxazaborolidine Catalyst

Mechanistic studies provided further insights into the origins of the catalytic effect.197 When the coumarin substrate is irradiated in the absence of a Lewis acid, the cycloaddition is stereospecific, where starting from either the tethered (E) or (Z)-alkene leads to distinct diastereomers. This is consistent with reaction through a singlet excited state. Upon addition of a Lewis acid, the quantum yield (Φ) of the photocycloaddition increases by an order of magnitude. Importantly, under these conditions the cycloaddition becomes stereoconvergent, indicating that the reaction proceeds through a triplet excited state. The Lewis acid promoted increase in efficiency was attributed to the presence of a heavy atom that facilitates intersystem crossing to the coumarin triplet excited state, which proceeds to the cycloadduct more efficiently than the shorter-lived singlet coumarin.

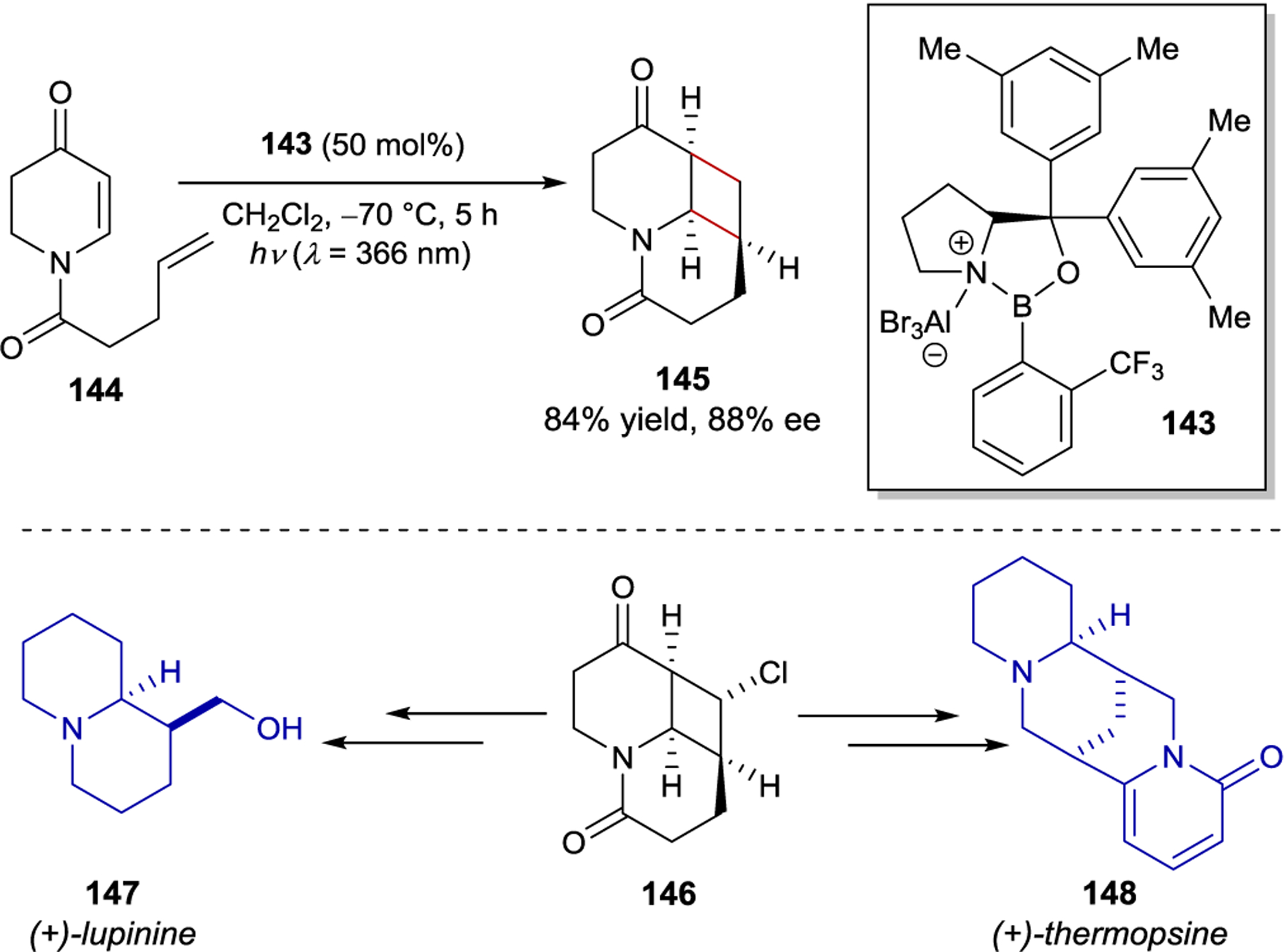

Exploring the generality of this strategy, Bach and coworkers investigated the enantioselective [2+2] photocycloaddition of the synthetically useful class of 5,6-dihydro-4-pyridones (Scheme 58).198 In contrast to their previous work, enone 144 undergoes a more pronounced bathochromic shift when coordinated to a Lewis acid. The authors reasoned that this red shift in combination with a longer wavelength light source would enable selective excitation of the bound species, thus eliminating racemic background reactivity. This proved correct and yielded highly selective cycloadditions (up to 90% ee). In addition, one of the products (146) was utilized as a key intermediate in the total synthesis of (+)-lupinine and the formal synthesis of (+)-thermopsine.

Scheme 58.

Enantioselective [2+2] Photocycloadditions of 5,6-Dihydro-4-pyridones

Despite the superficial similarities of coumarin 38 and dihydropyridone 144, there are several intriguing differences in the mechanisms of their Lewis acid catalyzed [2+2] photocycloadditions. First, the dihydropyridone substrates undergo stereoconvergent cyclization with and without Lewis acid, consistent with the formation of a triplet excited state in both cases. In contrast to the coumarin substrates, the quantum yield of the dihydropyridone cycloaddition decreases from 0.23 to 4 × 10−3 in the presence of a Lewis acid. It is therefore surprising that high enantioselectivity is achieved given that after excitation, free pyridone cyclizes significantly more efficiently than catalyst-bound pyridone. However, this highlights the importance of the change in the absorption spectrum of the Lewis acid complex. Because almost all photons are absorbed by the Lewis acid-bound dihydropyridone upon irradiation at 366 nm, the relatively inefficient stereoselective cyclization still outcompetes the racemic direct excitation pathway. Bach’s mechanistic proposals for both the coumarin and dihydropyridone cycloadditions were consistent with computational studies conducted by Dolg199 and Chen.200

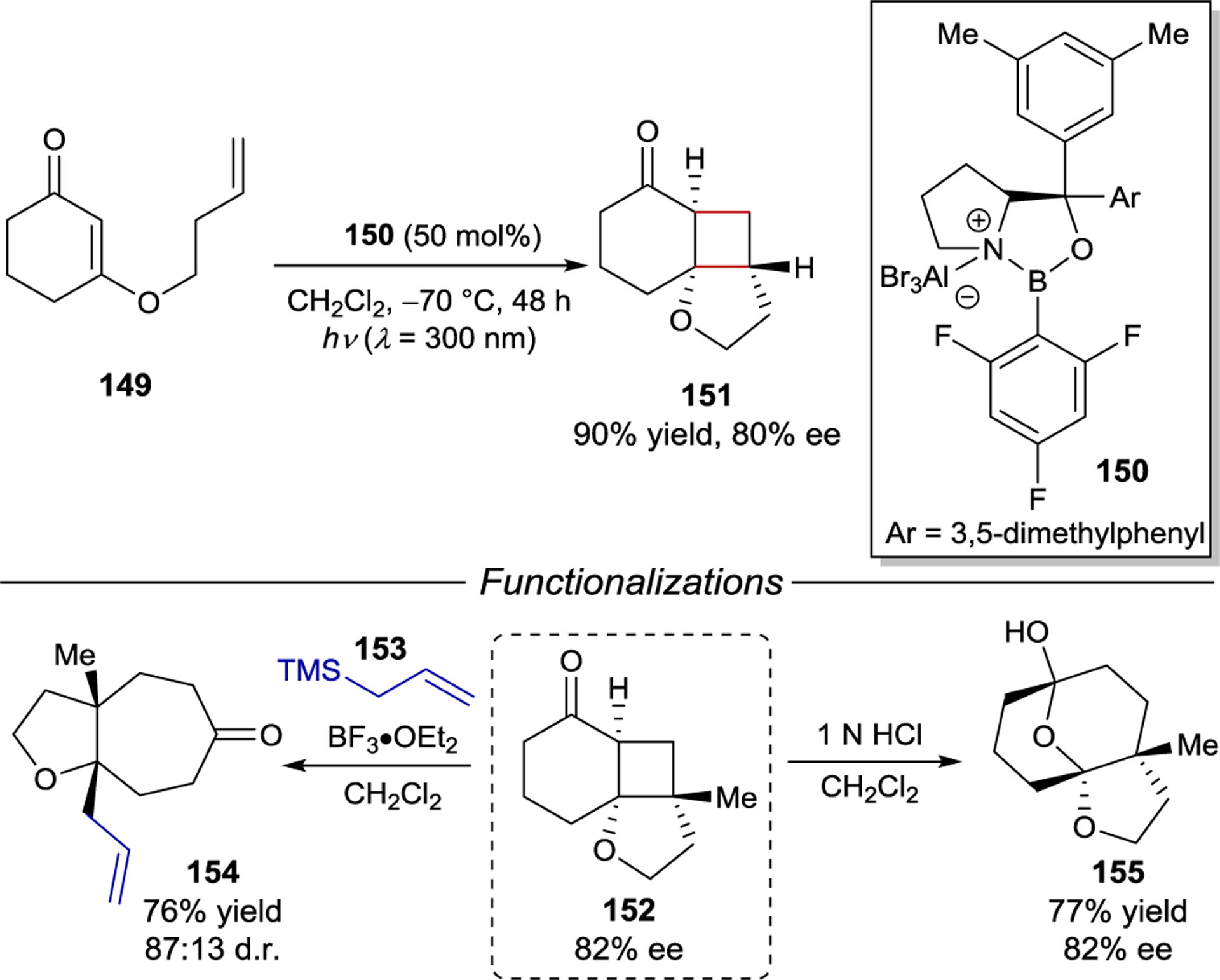

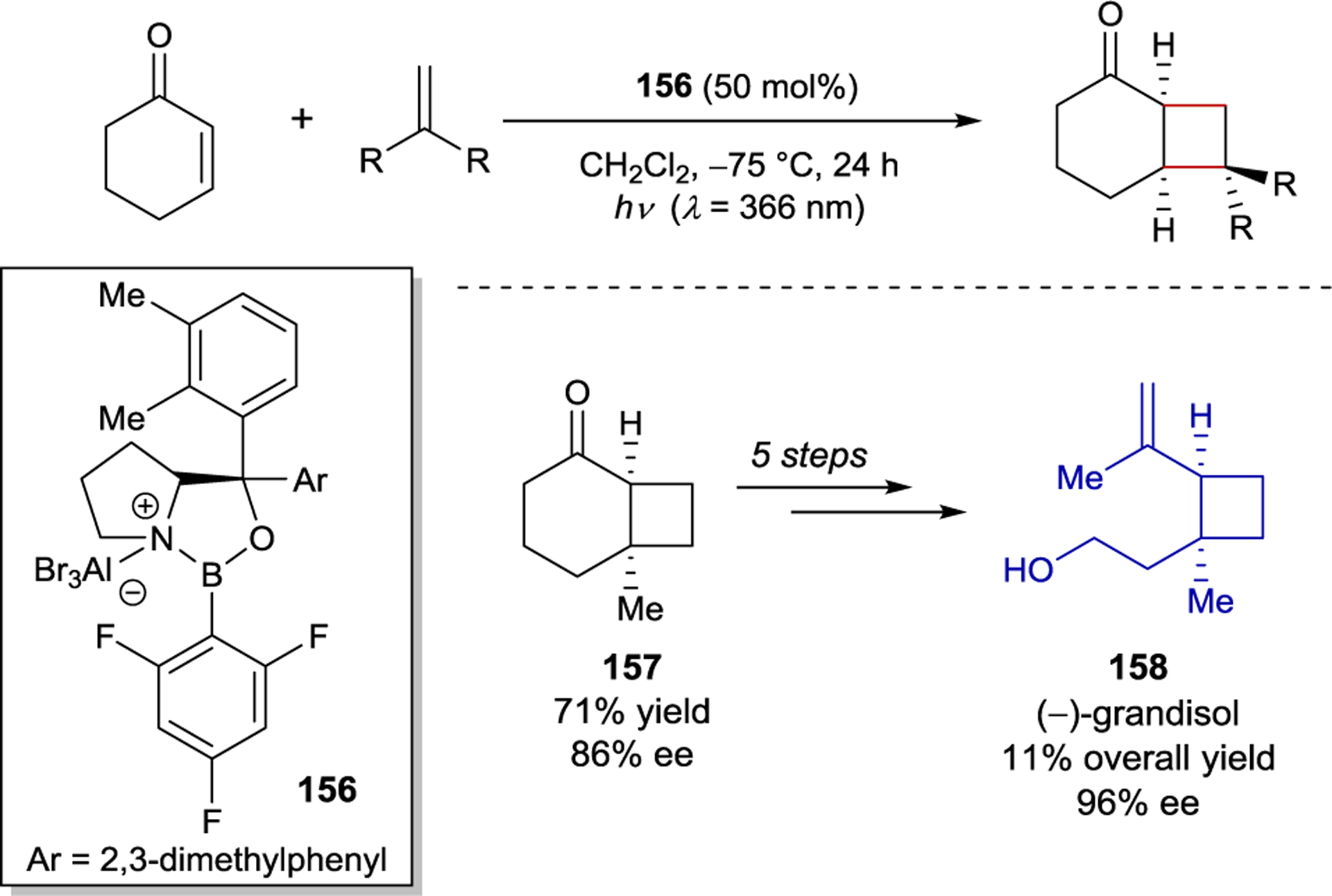

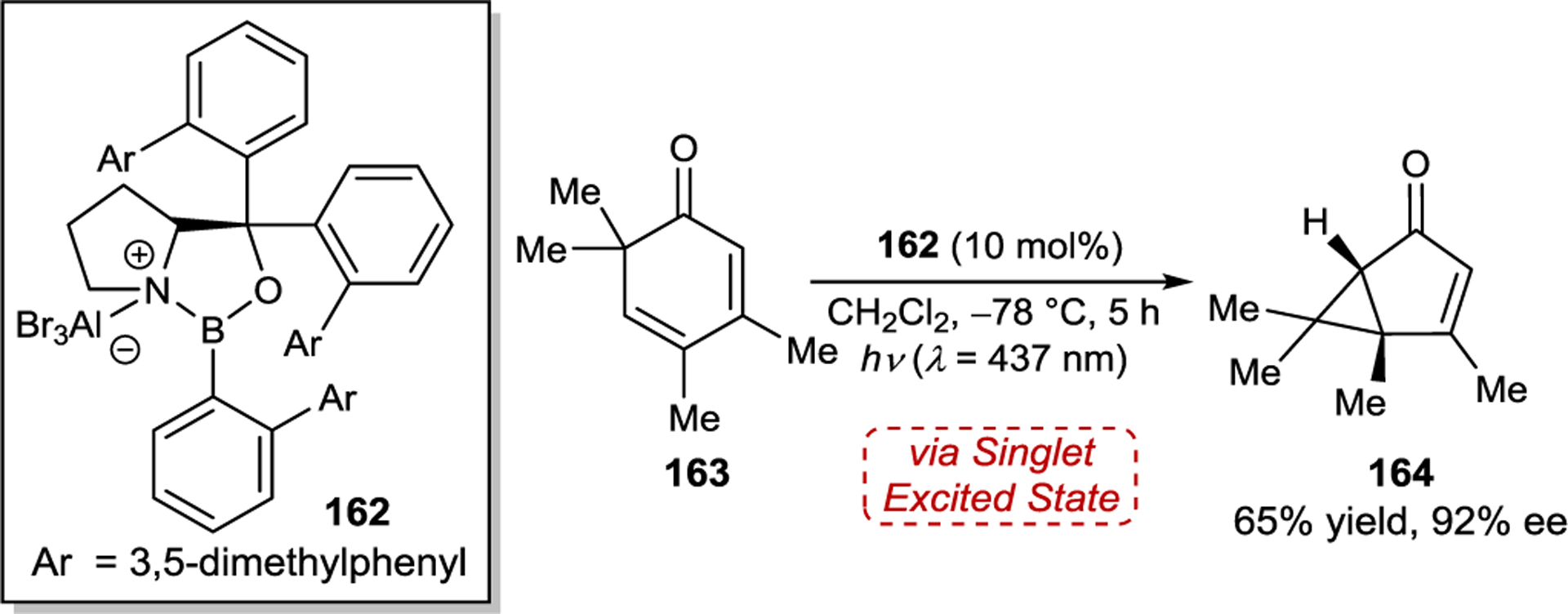

The ability to afford highly enantioenriched cyclobutane products from a chemo- and regioselective [2+2] photocycloaddition of simple cyclic enones and alkenes is a highly desirable goal. To this end, Bach and coworkers studied the enantioselective [2+2] photocycloaddition of 3-alkenyloxy-2-cycloalkenones (149) (Scheme 59).201 For this [2+2] photocycloaddition, modified AlBr3-activated oxazaborolidine 150 proved to be ideal, delivering the simple aliphatic cyclobutane products in nearly quantitative yield and up to 94% ee. The utility of these products was showcased through acid-catalyzed allylation and ring expansion reactions that afforded 154 and 155 without erosion of enantioselectivity.

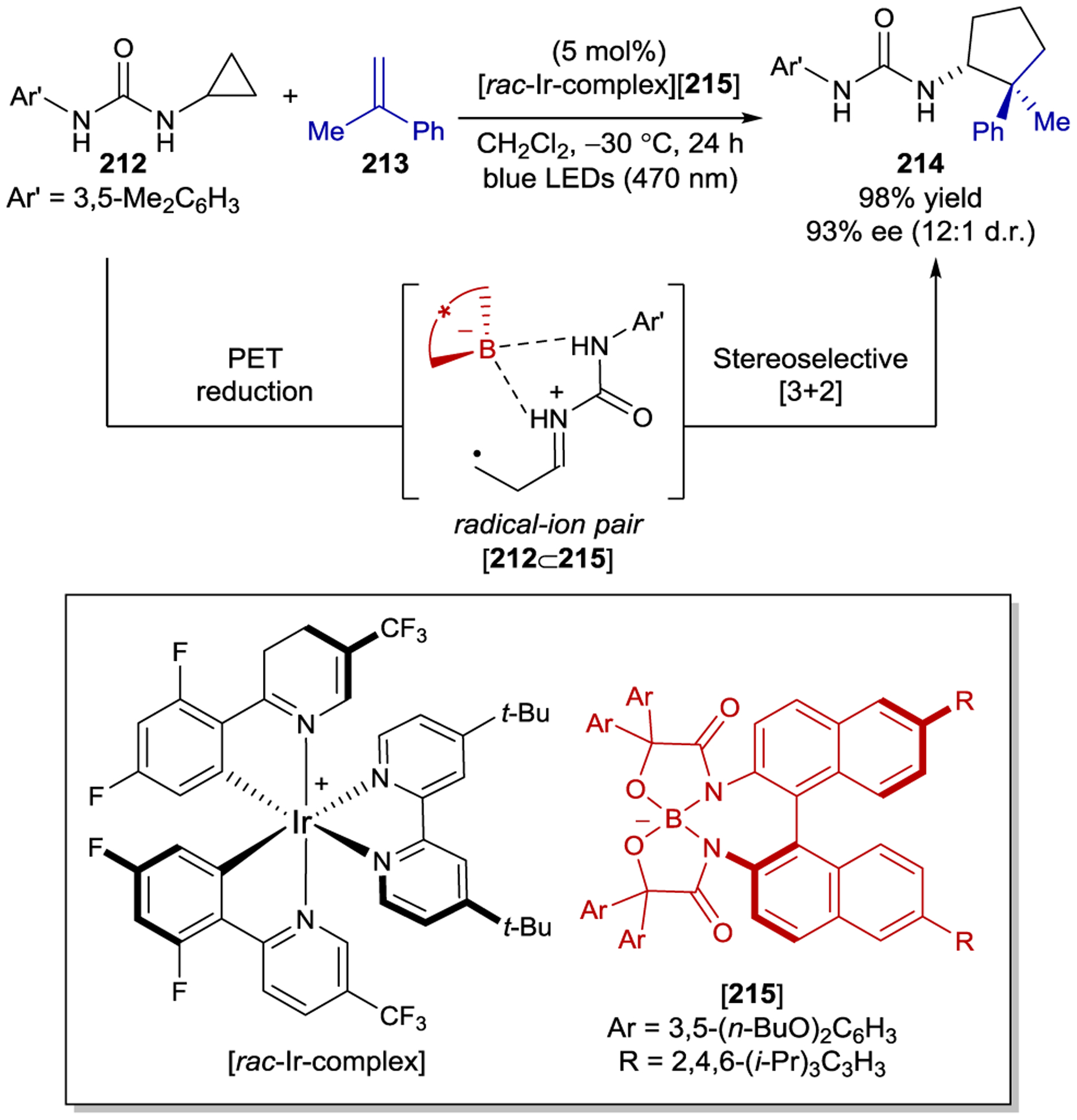

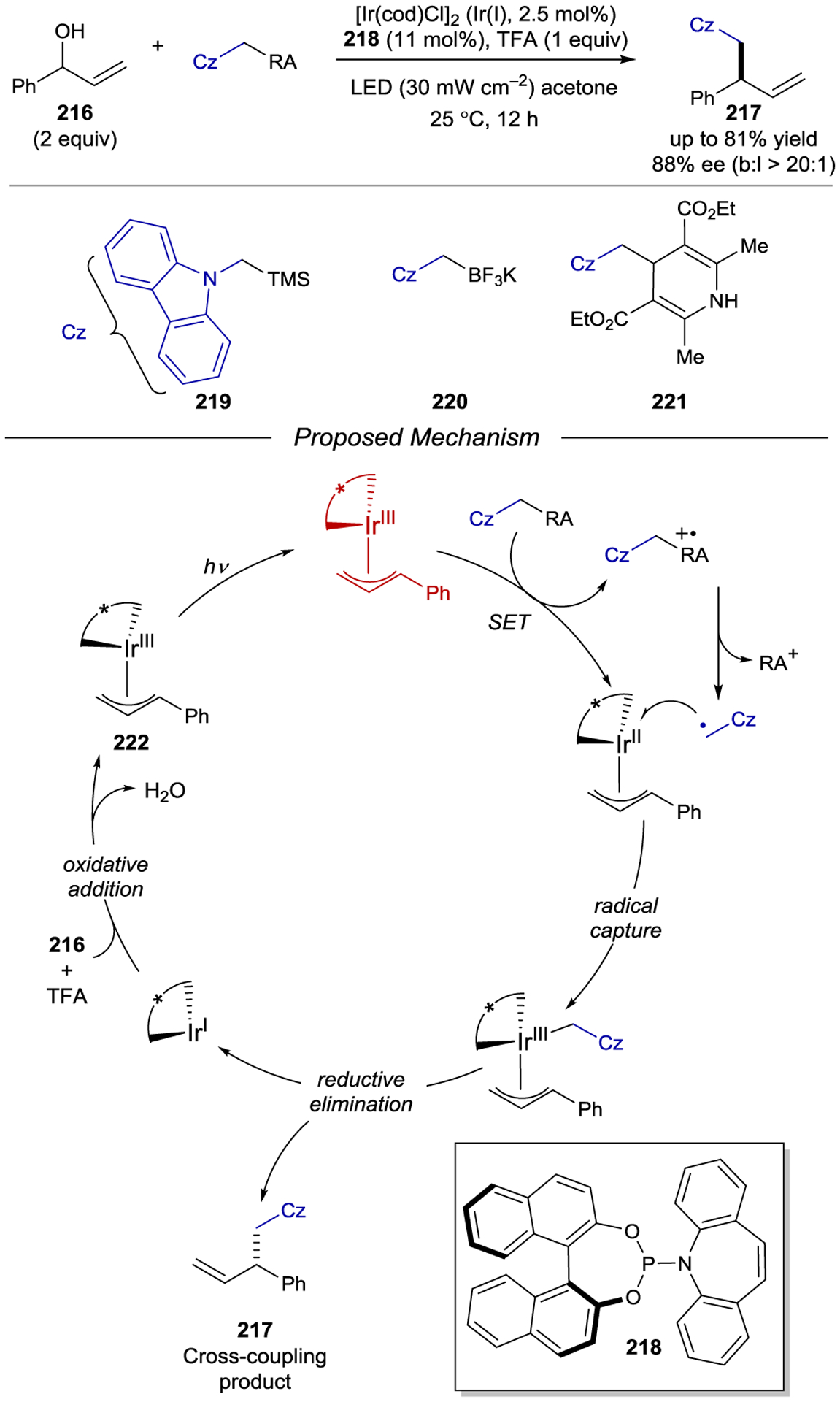

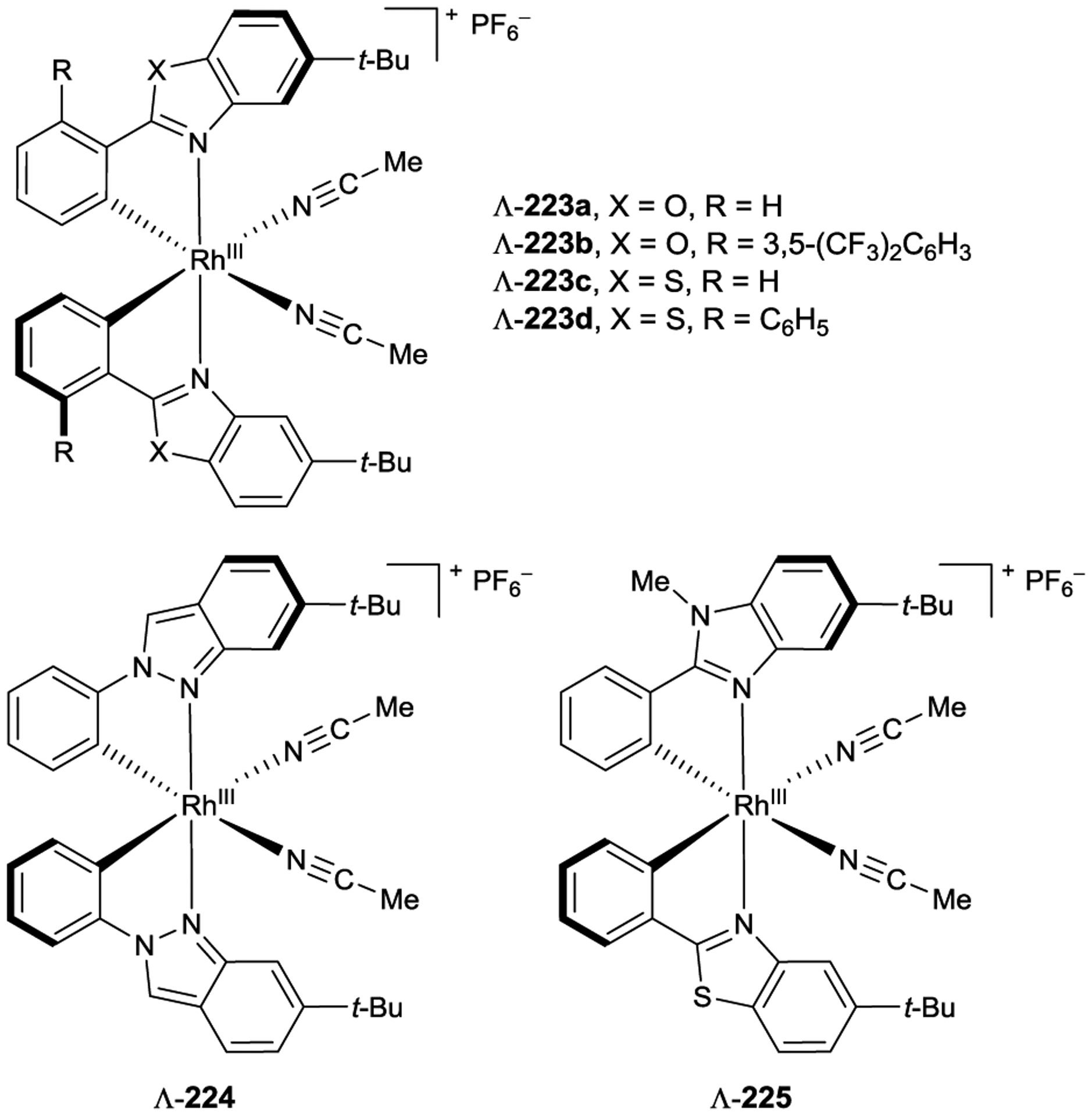

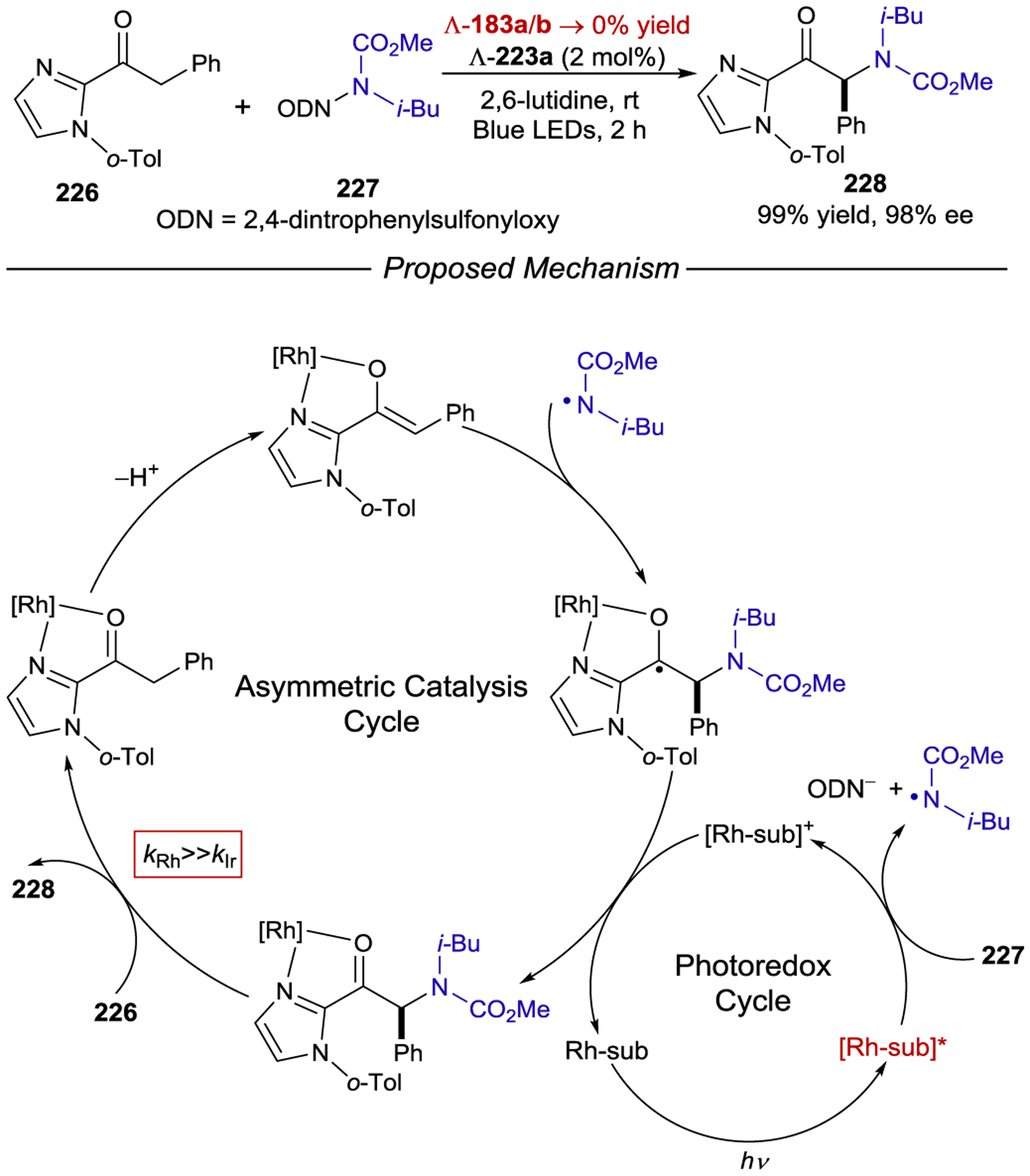

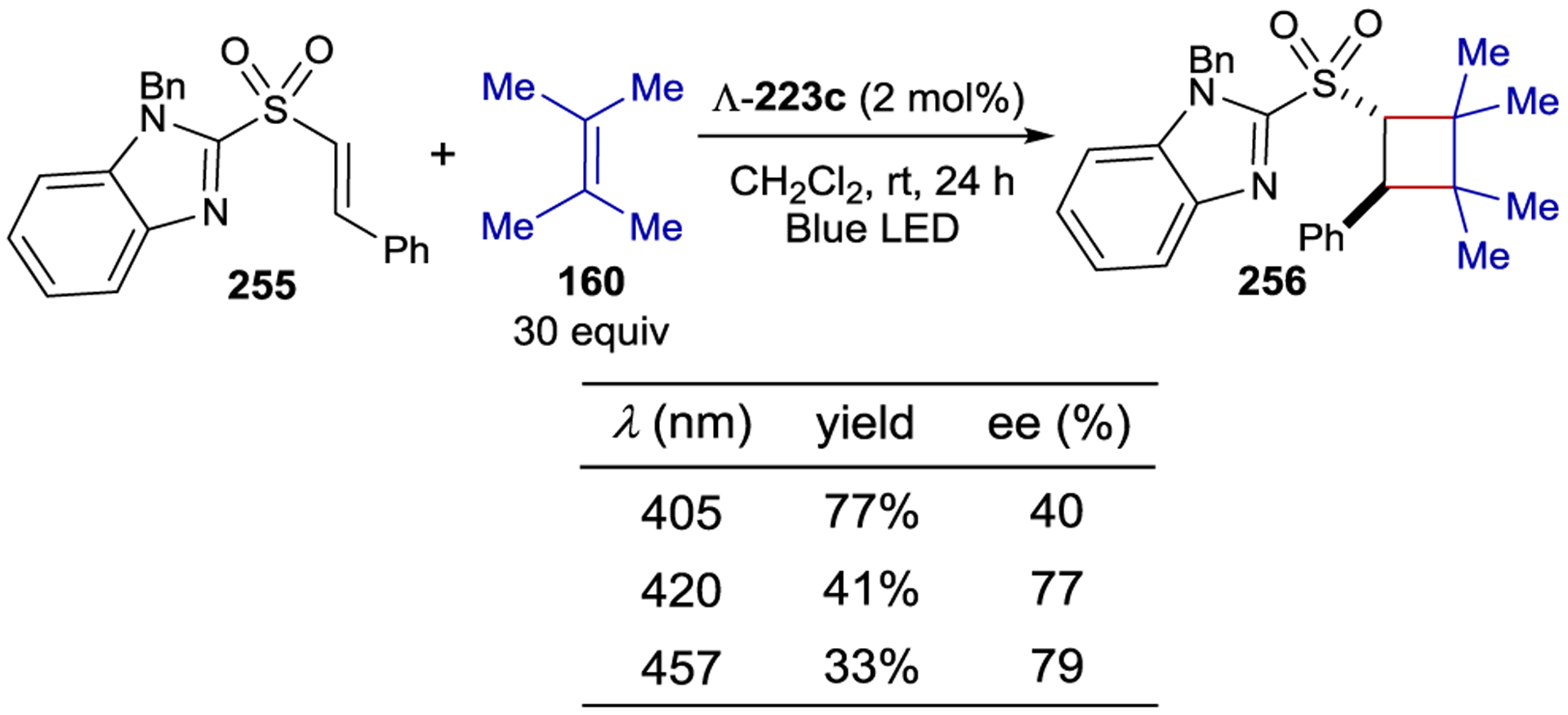

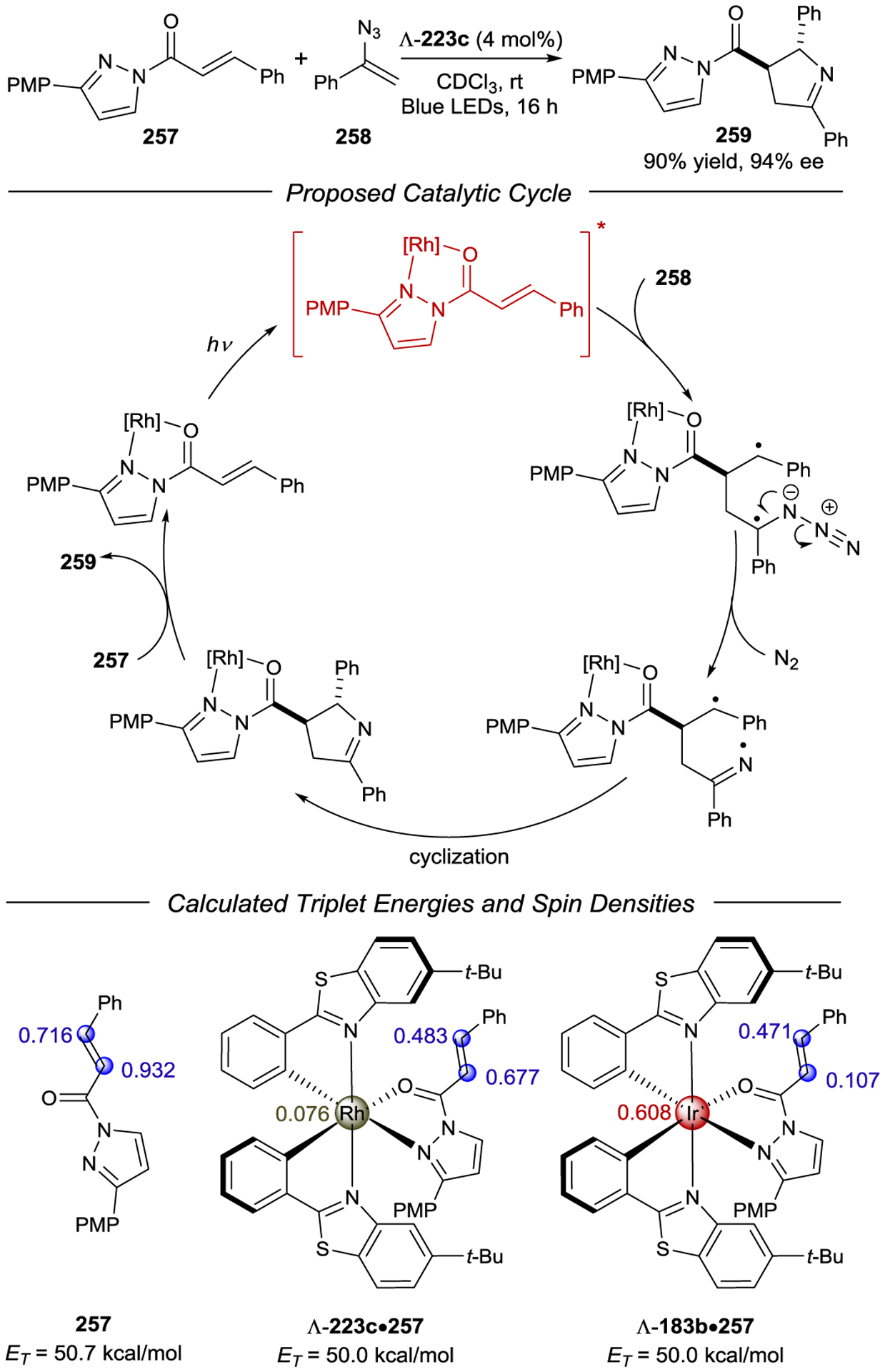

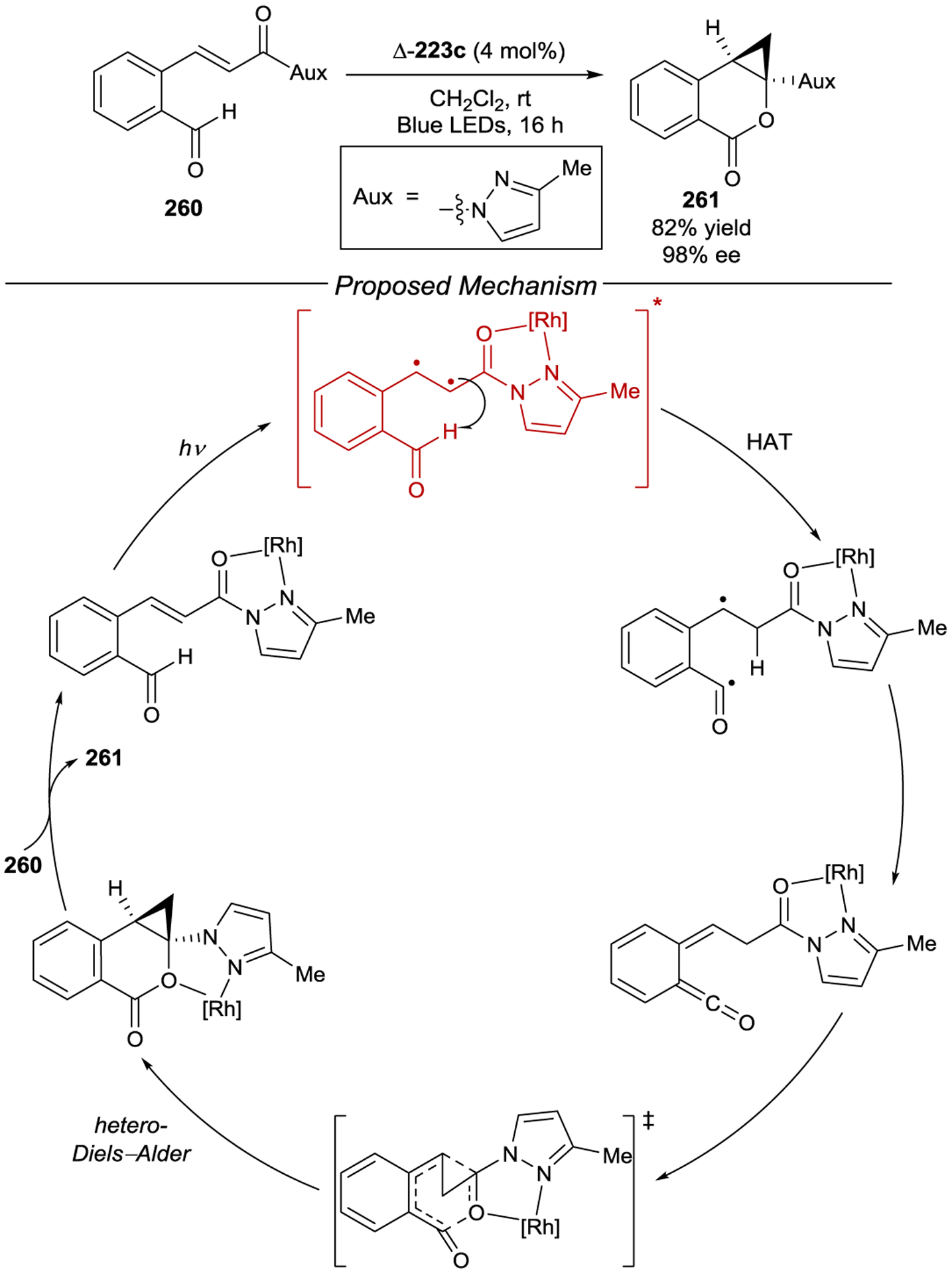

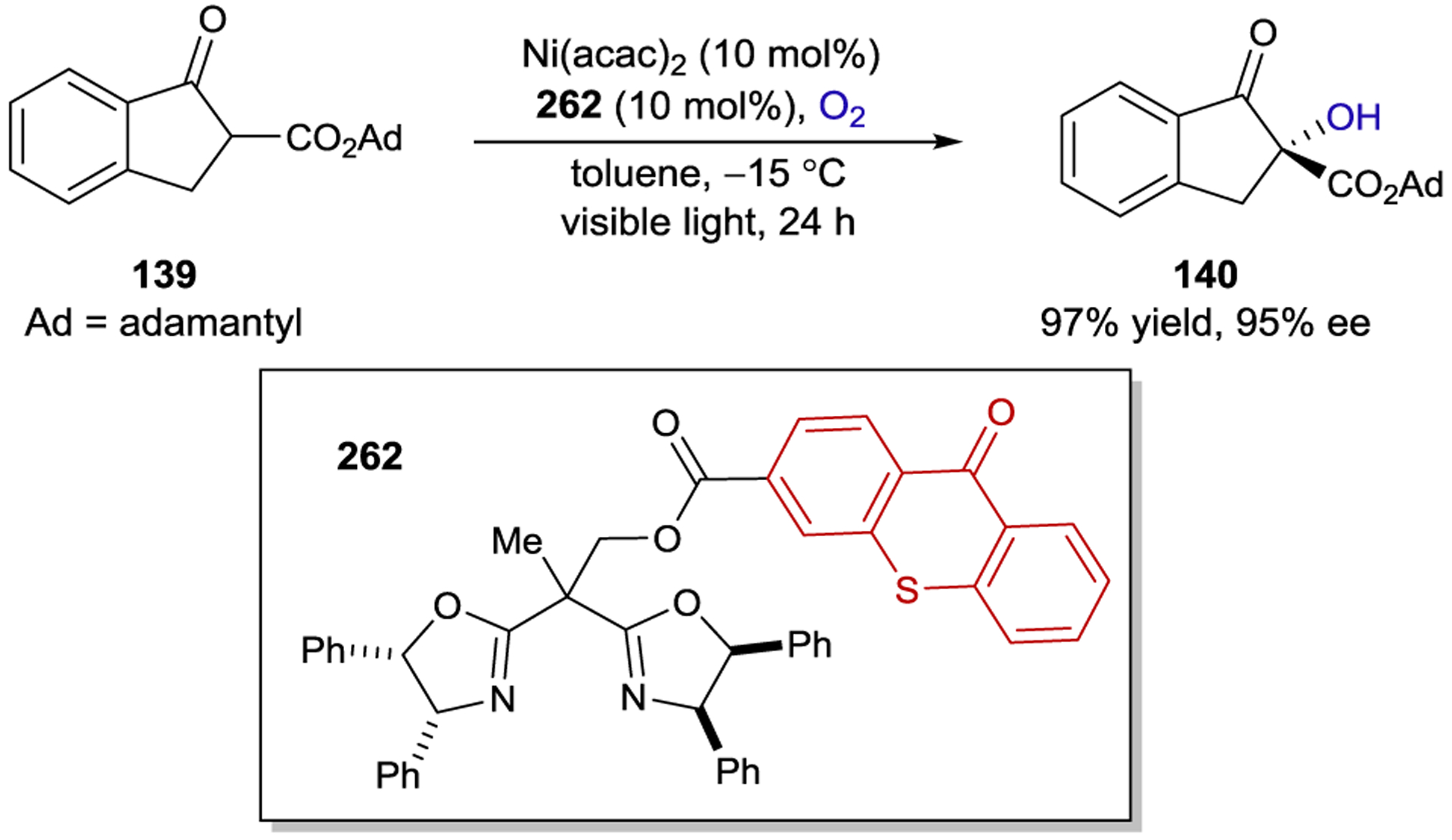

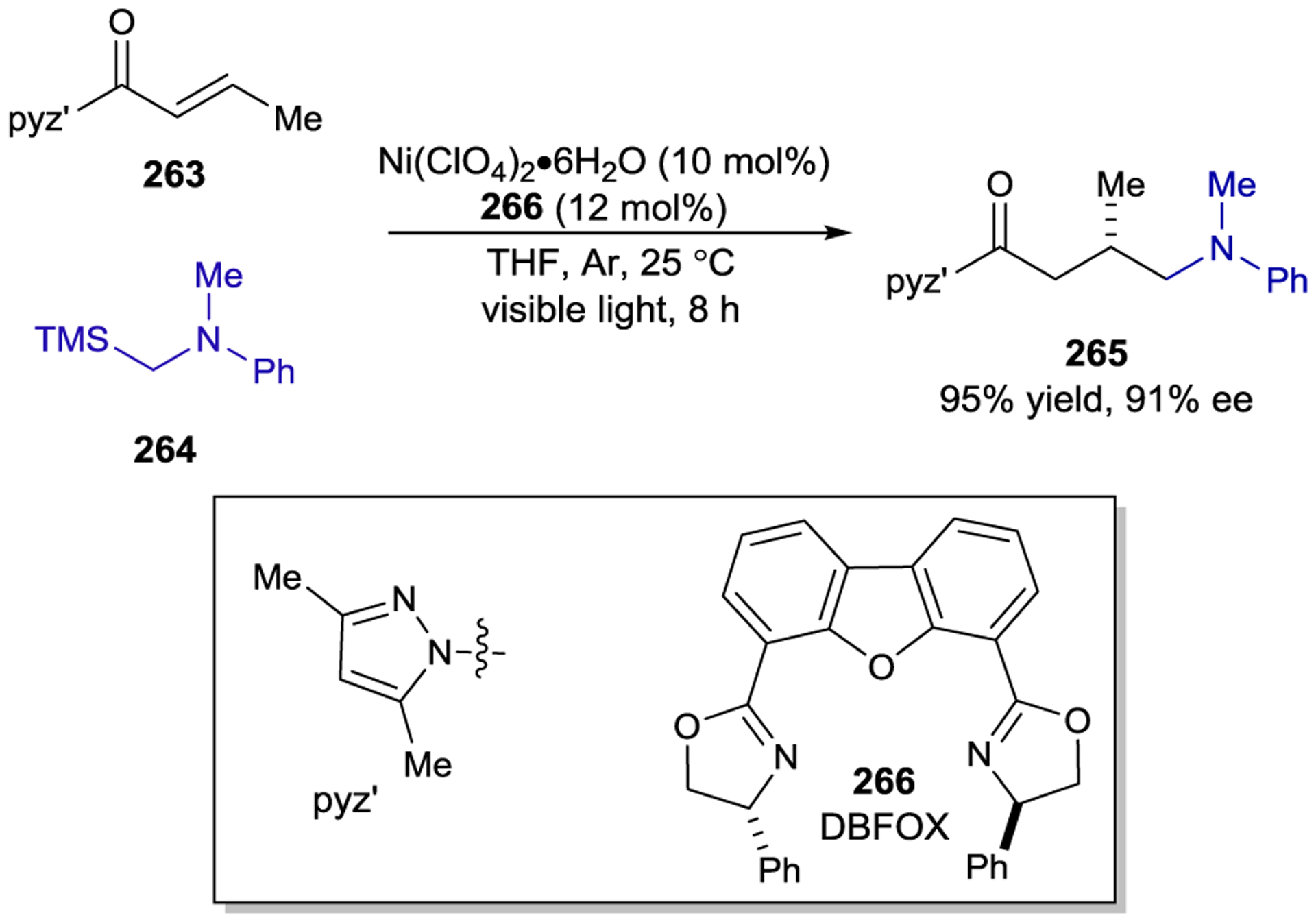

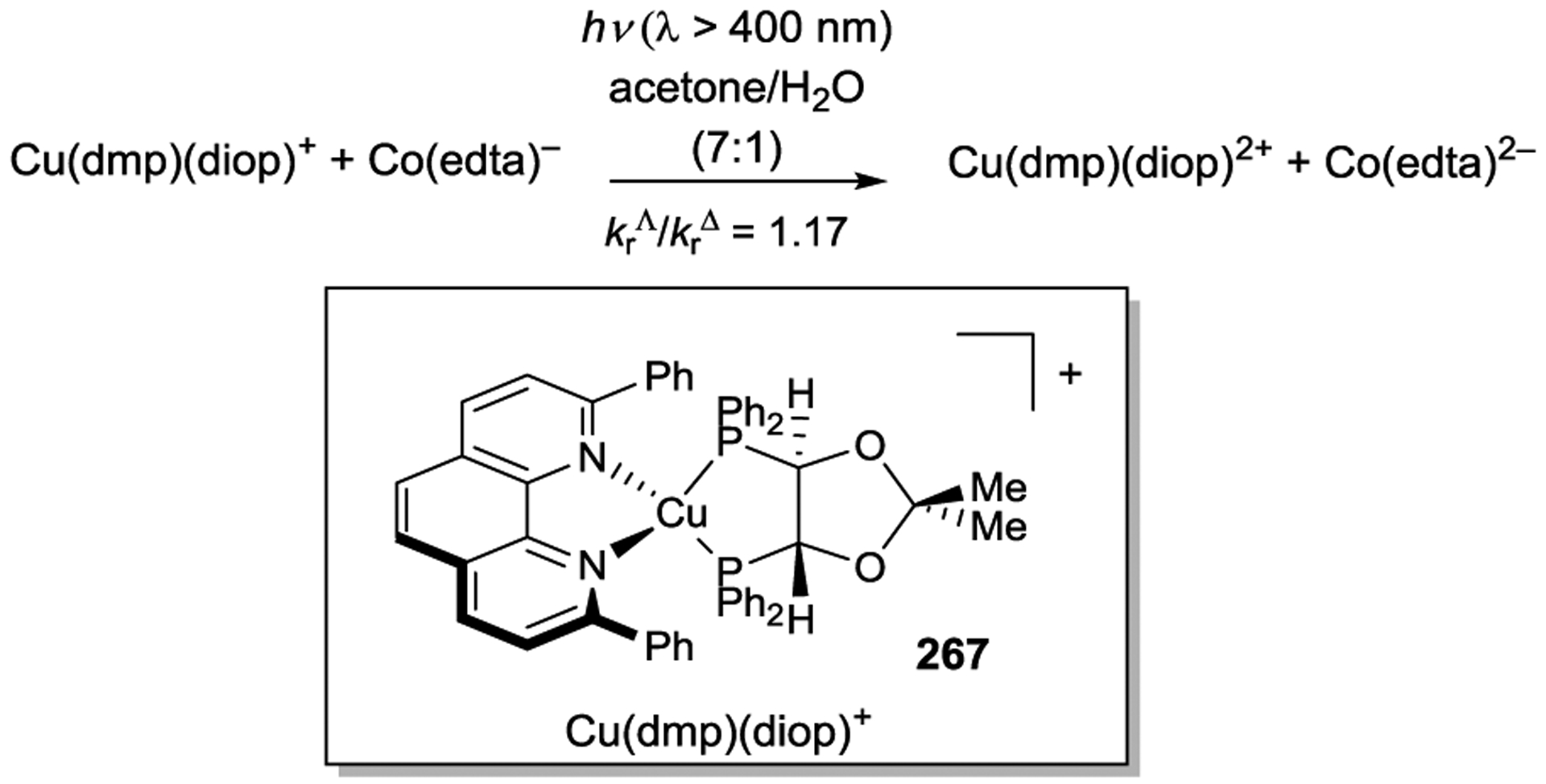

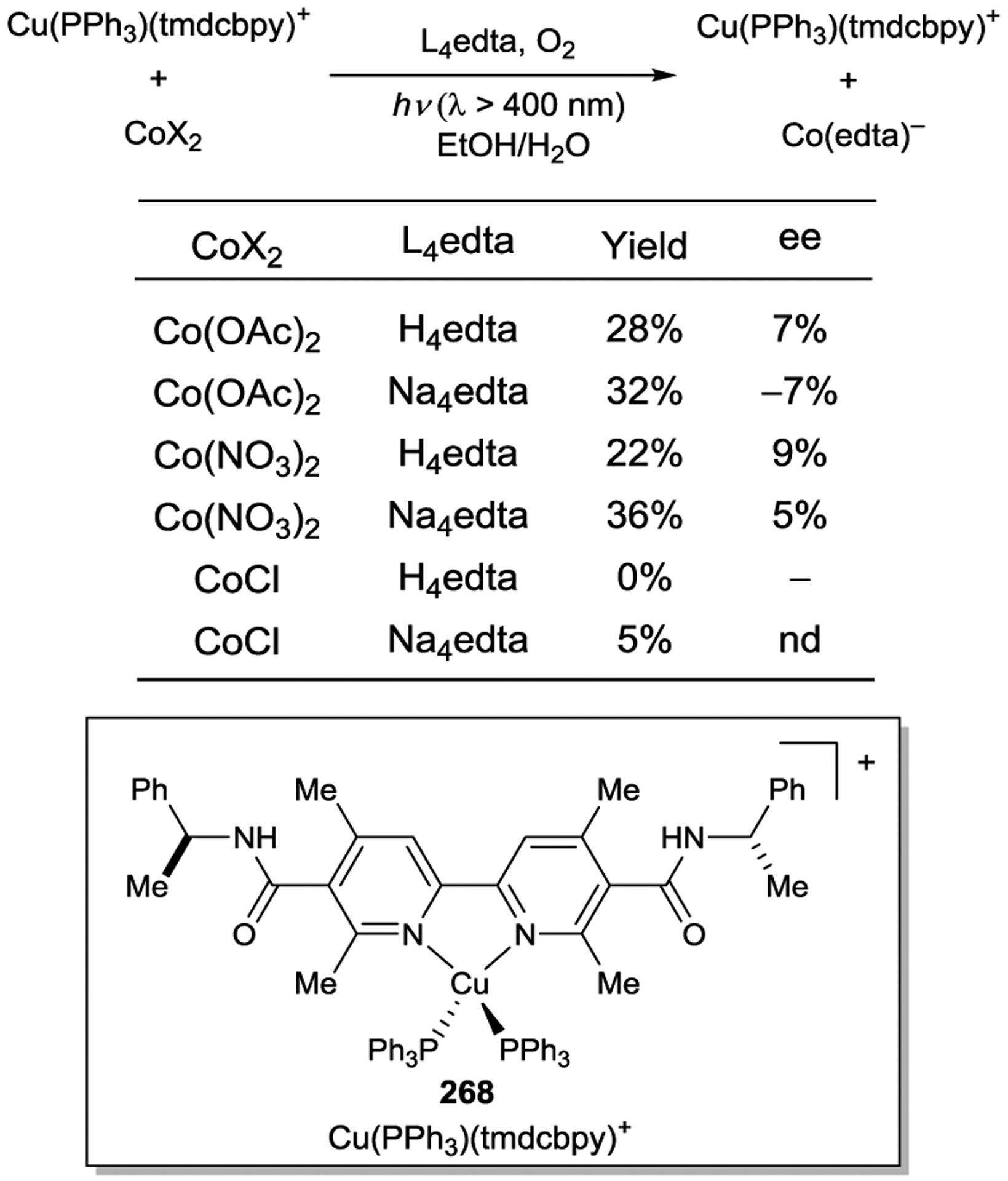

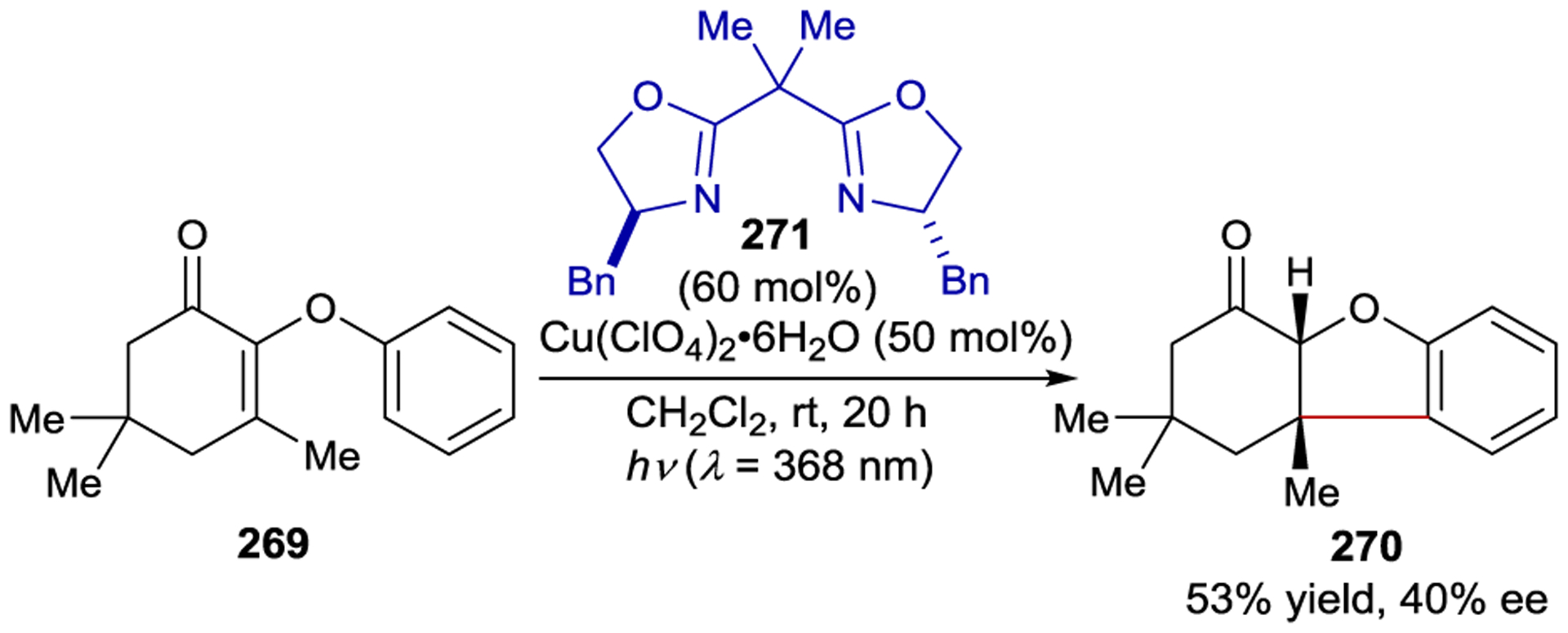

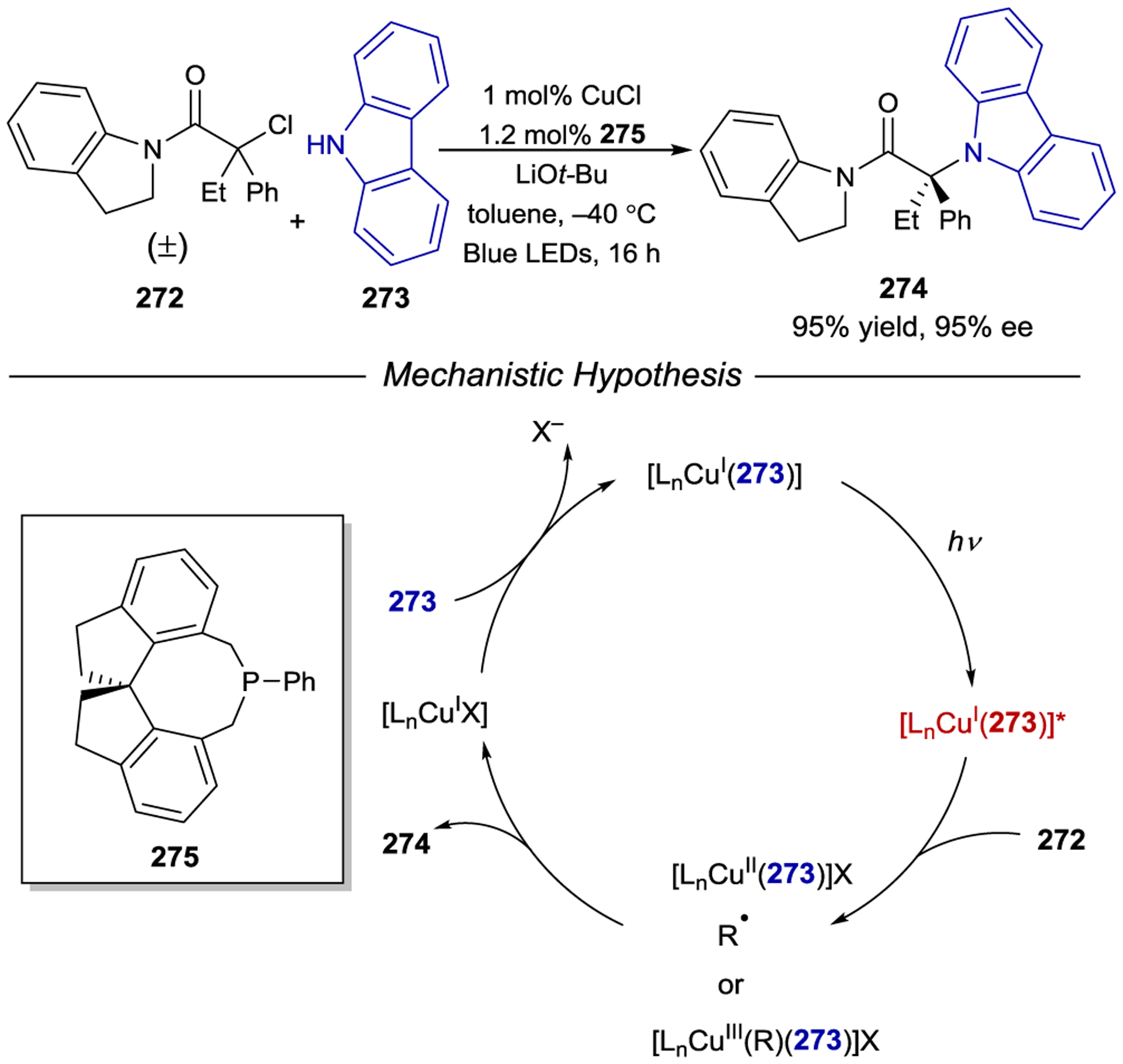

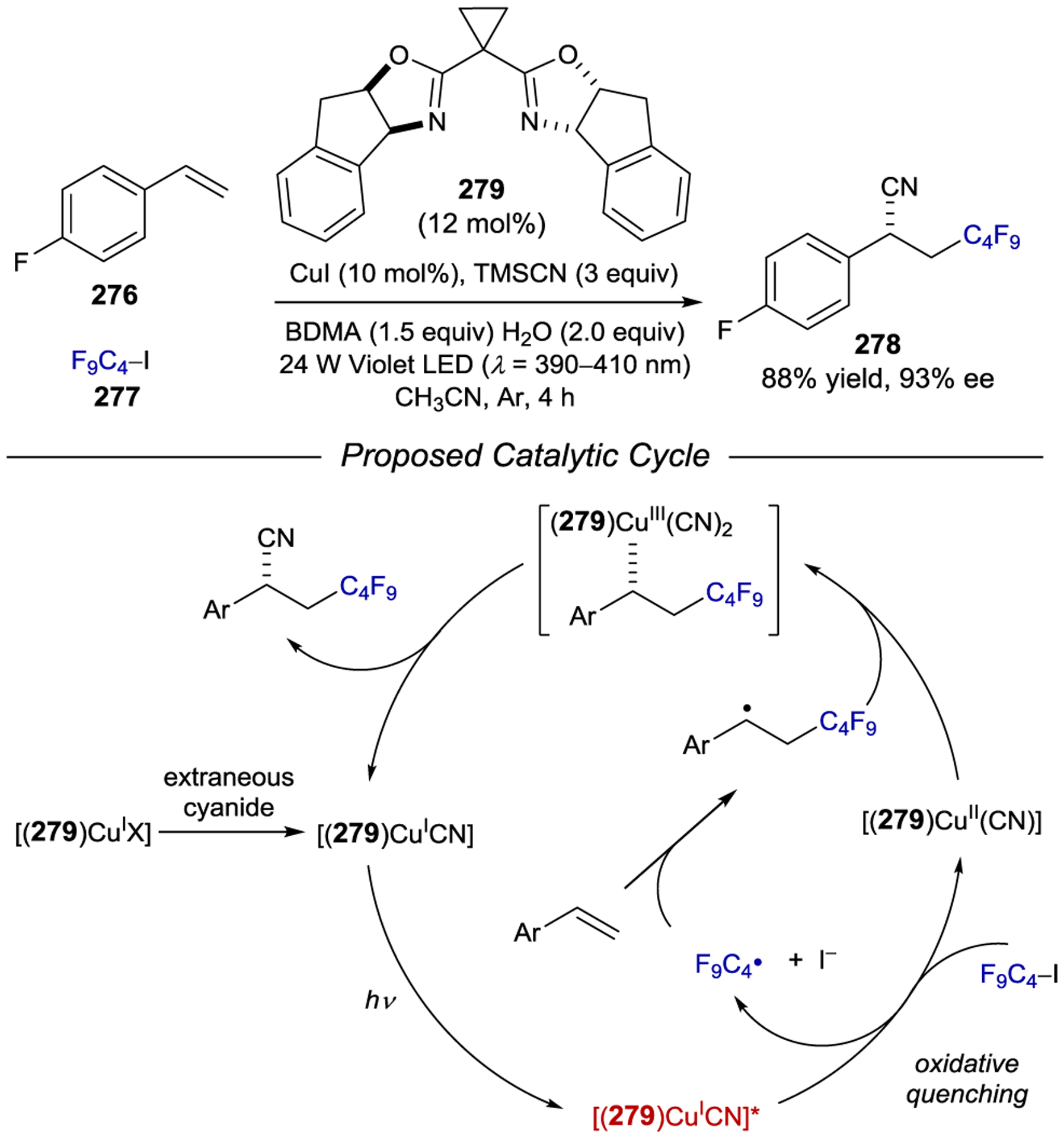

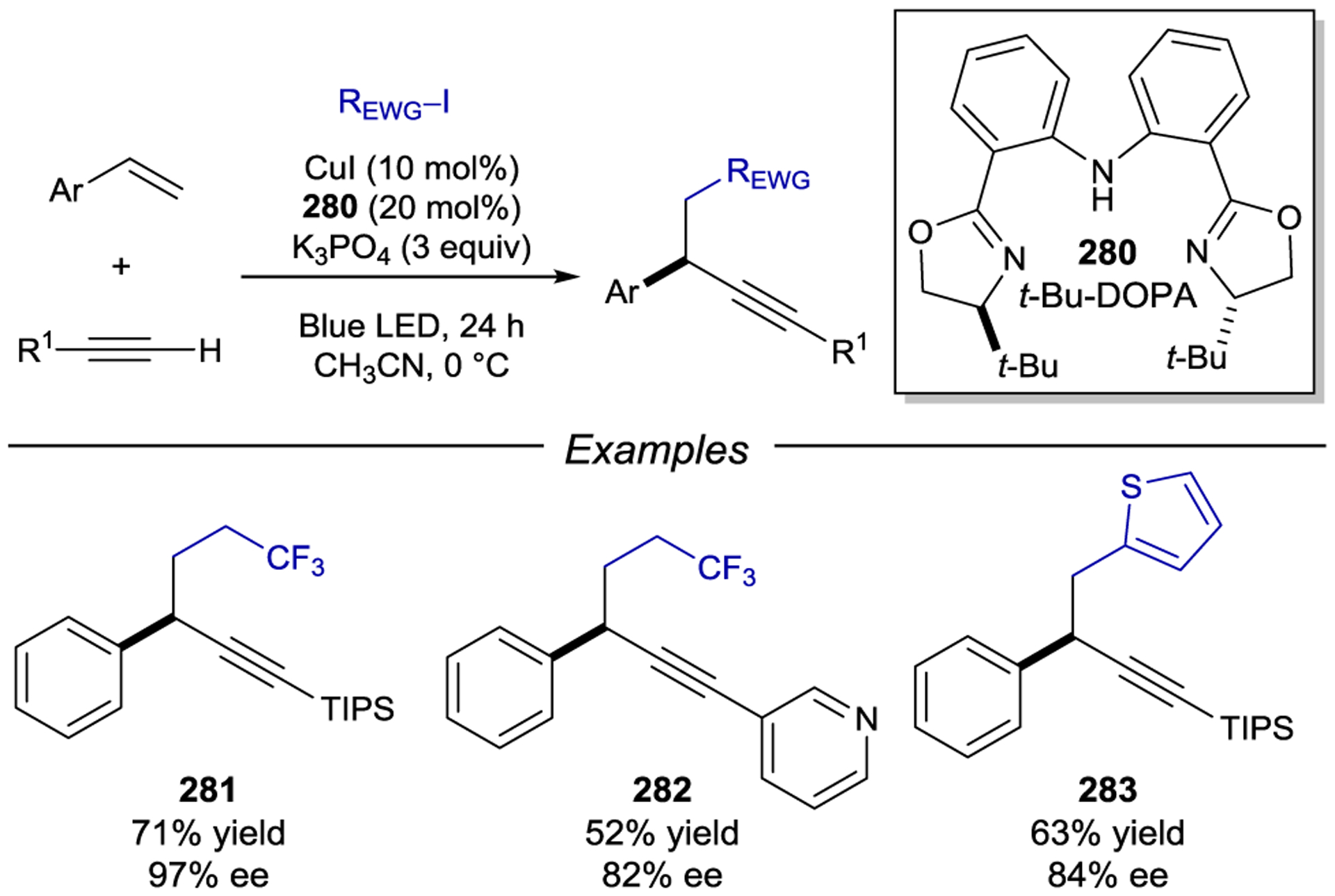

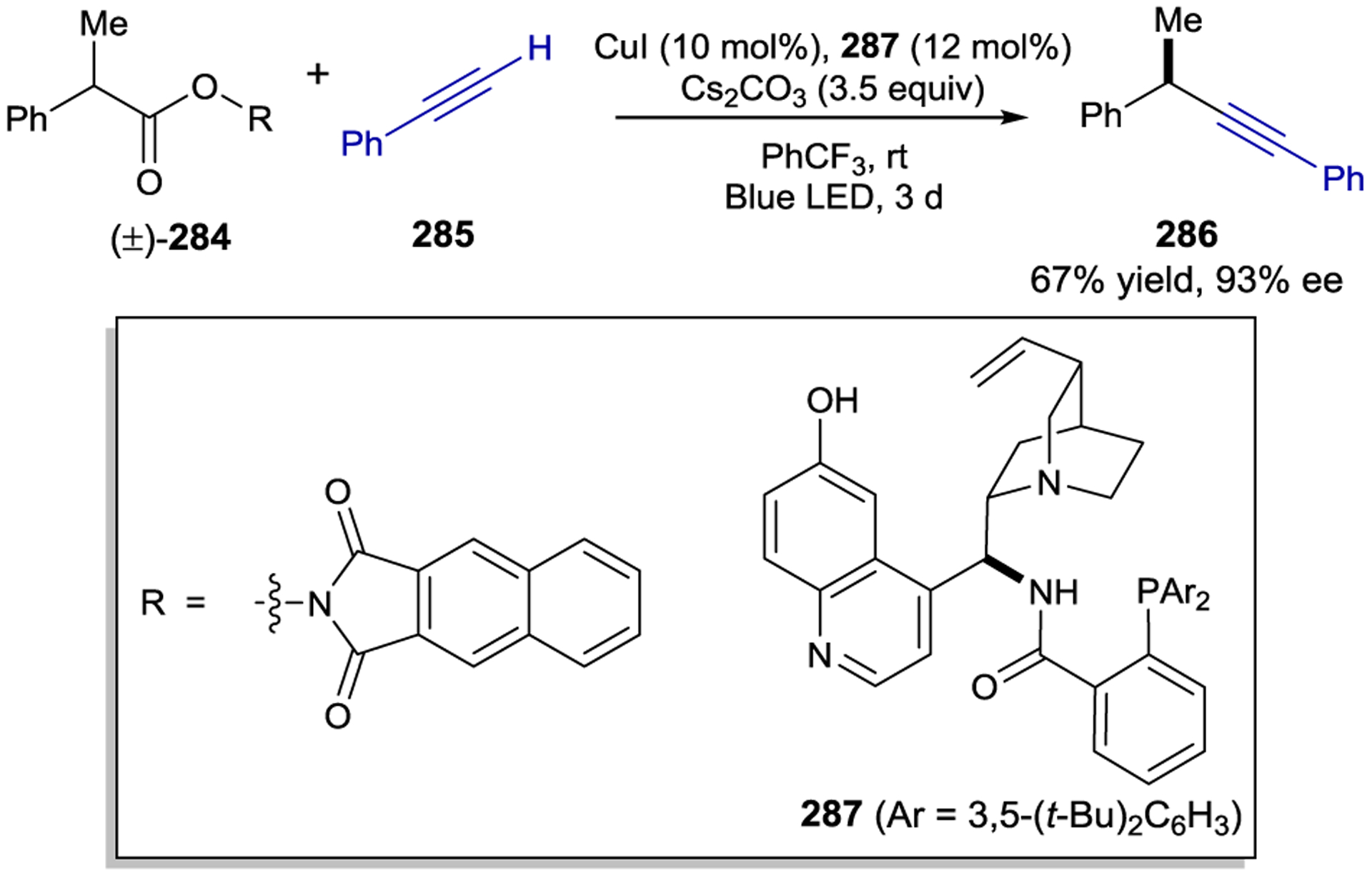

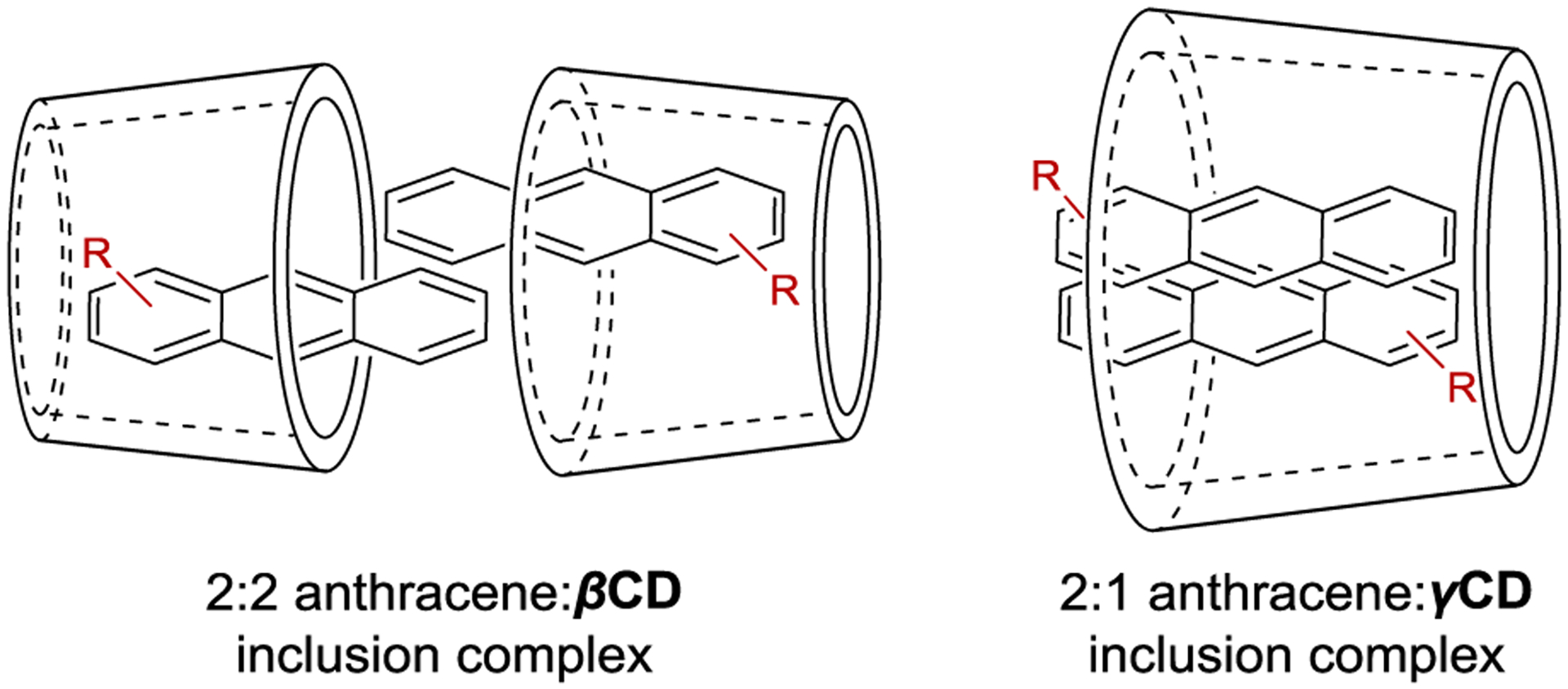

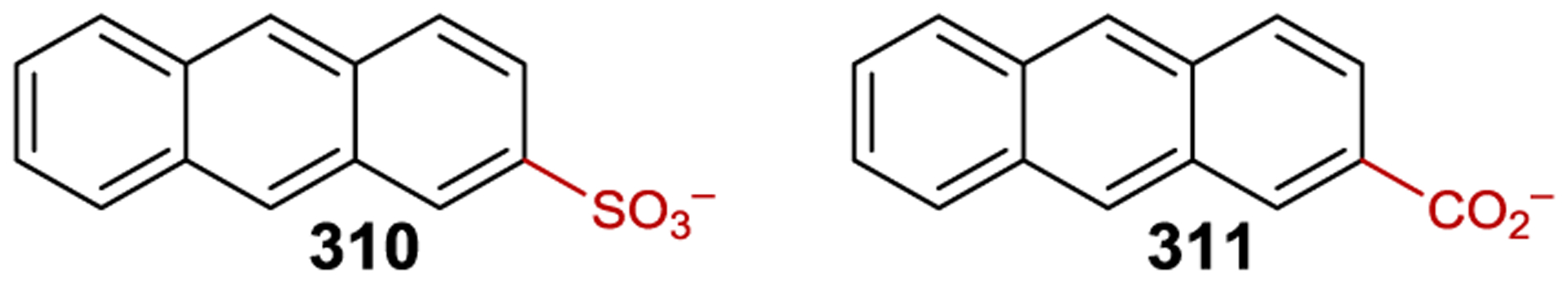

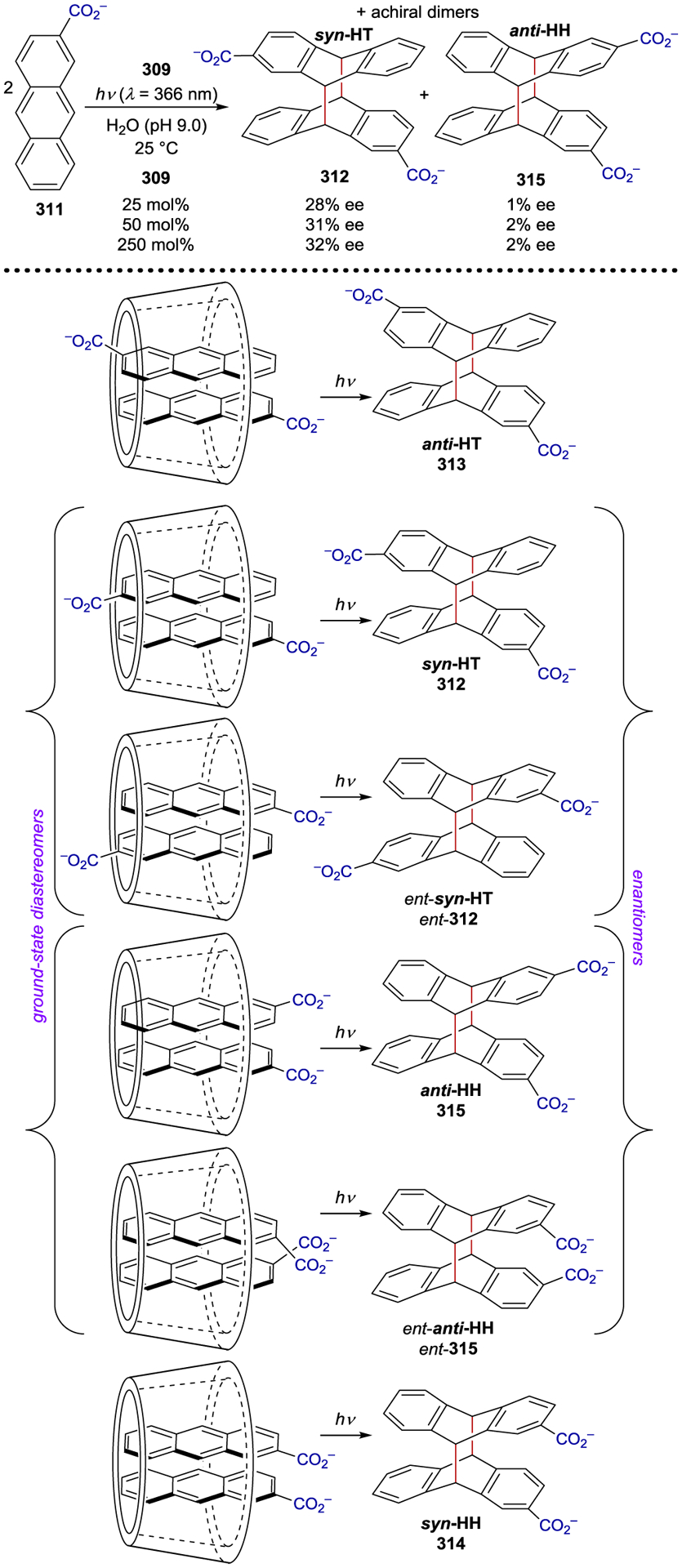

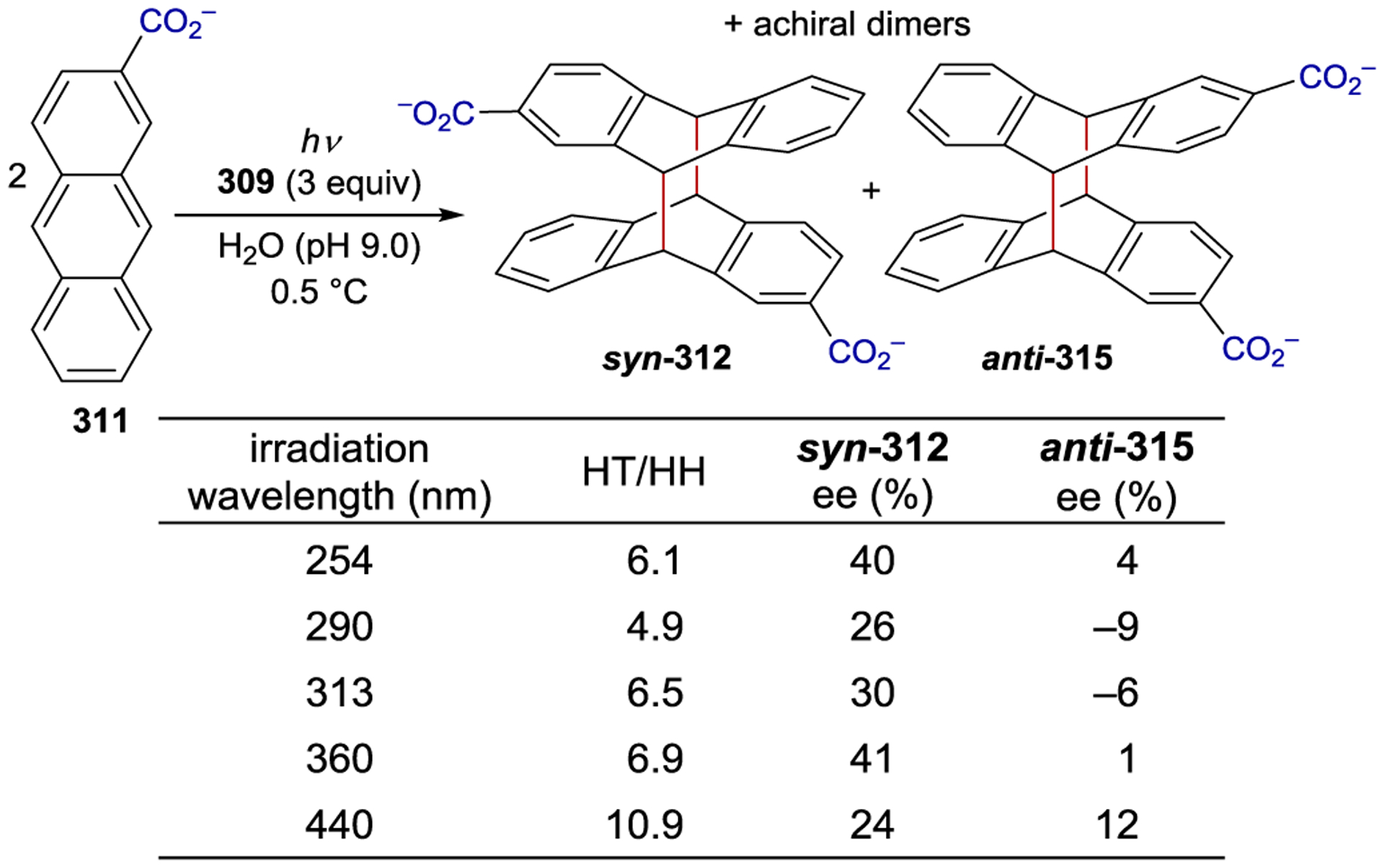

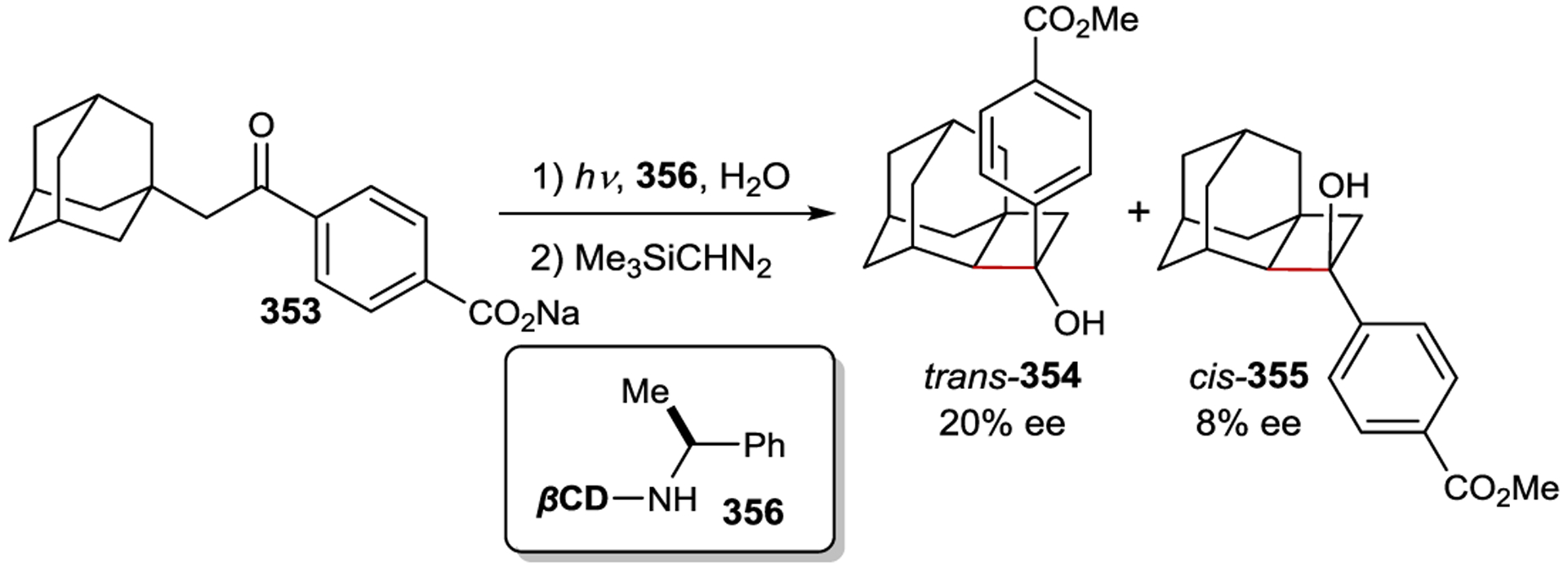

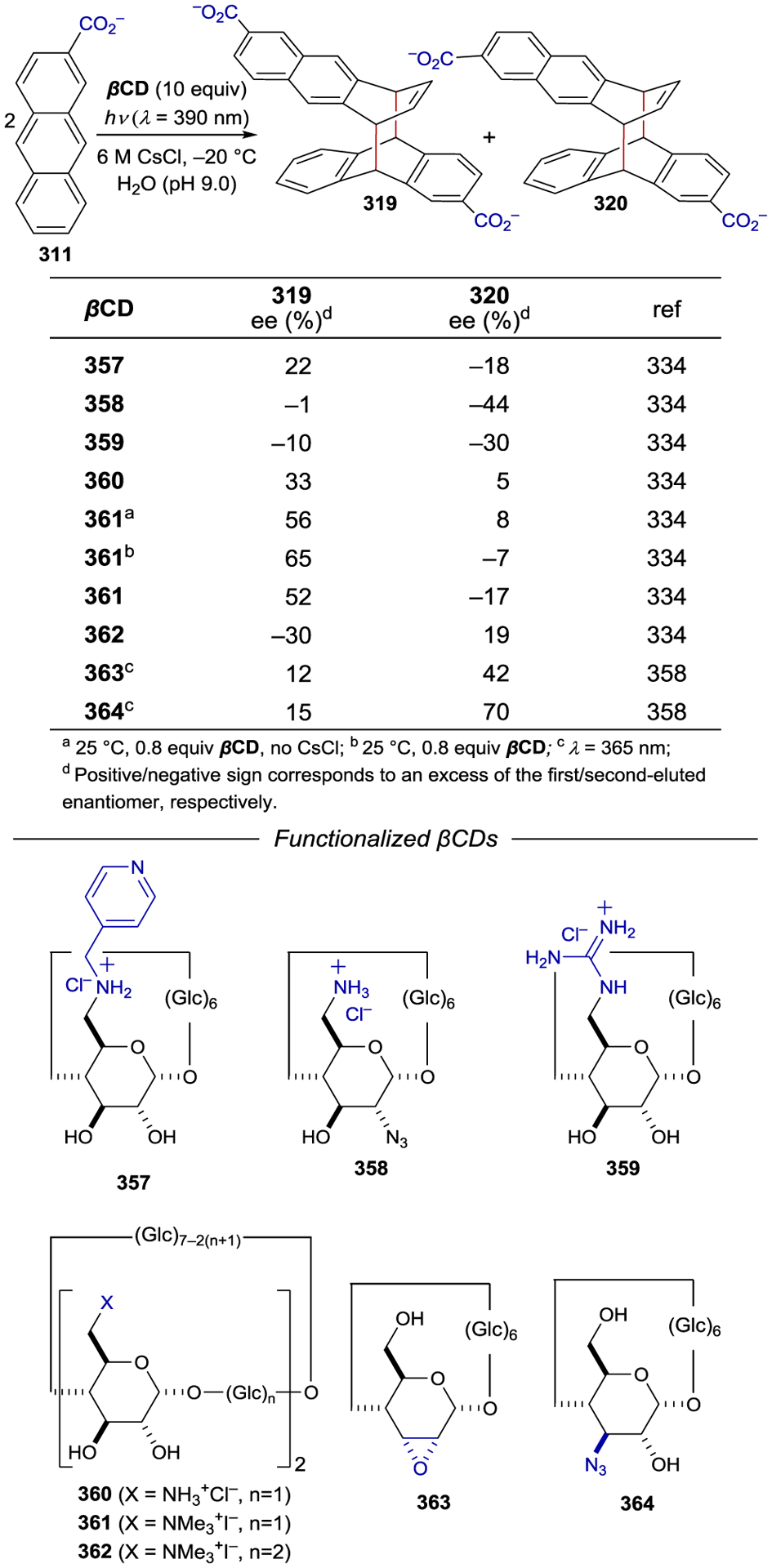

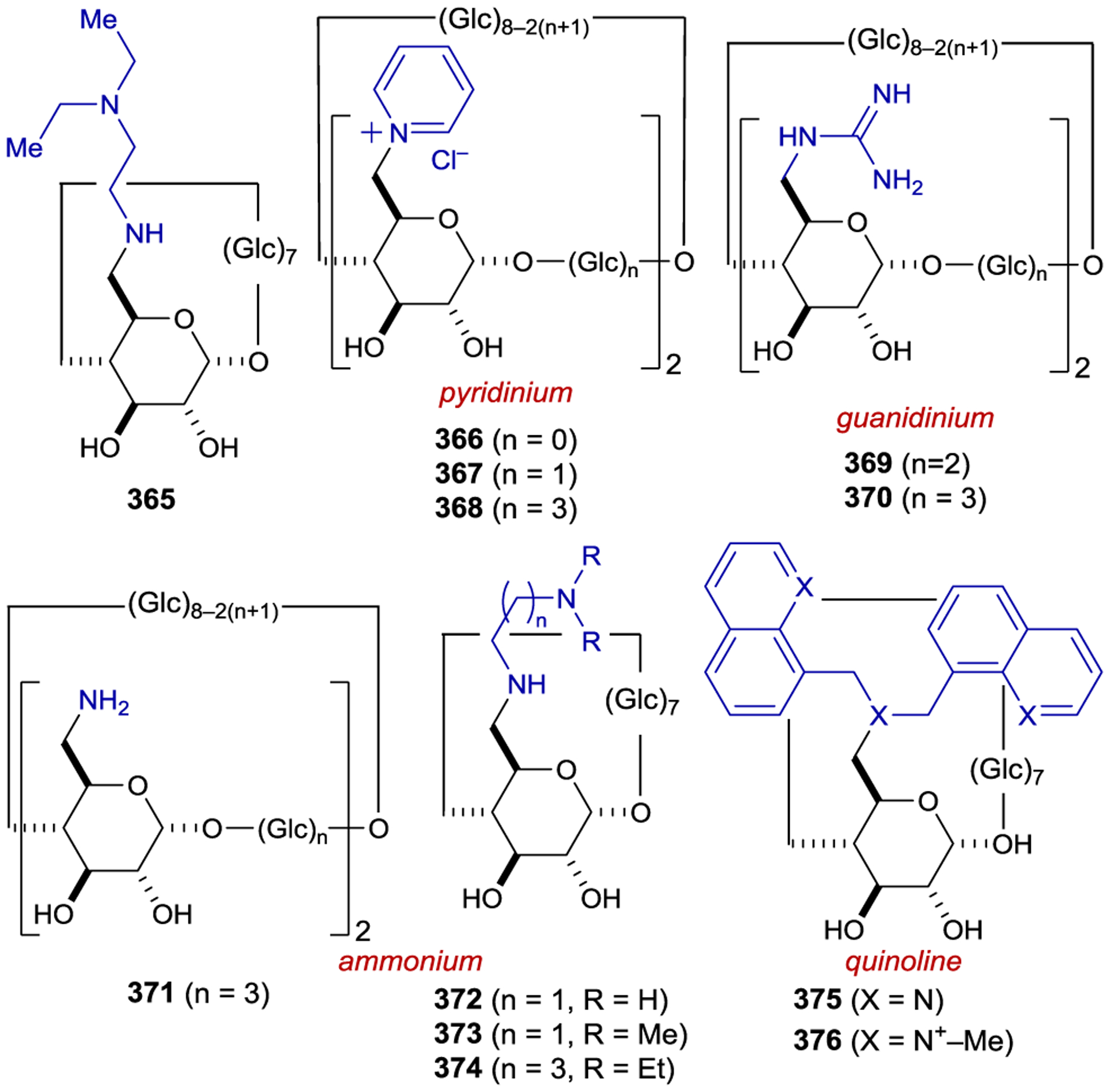

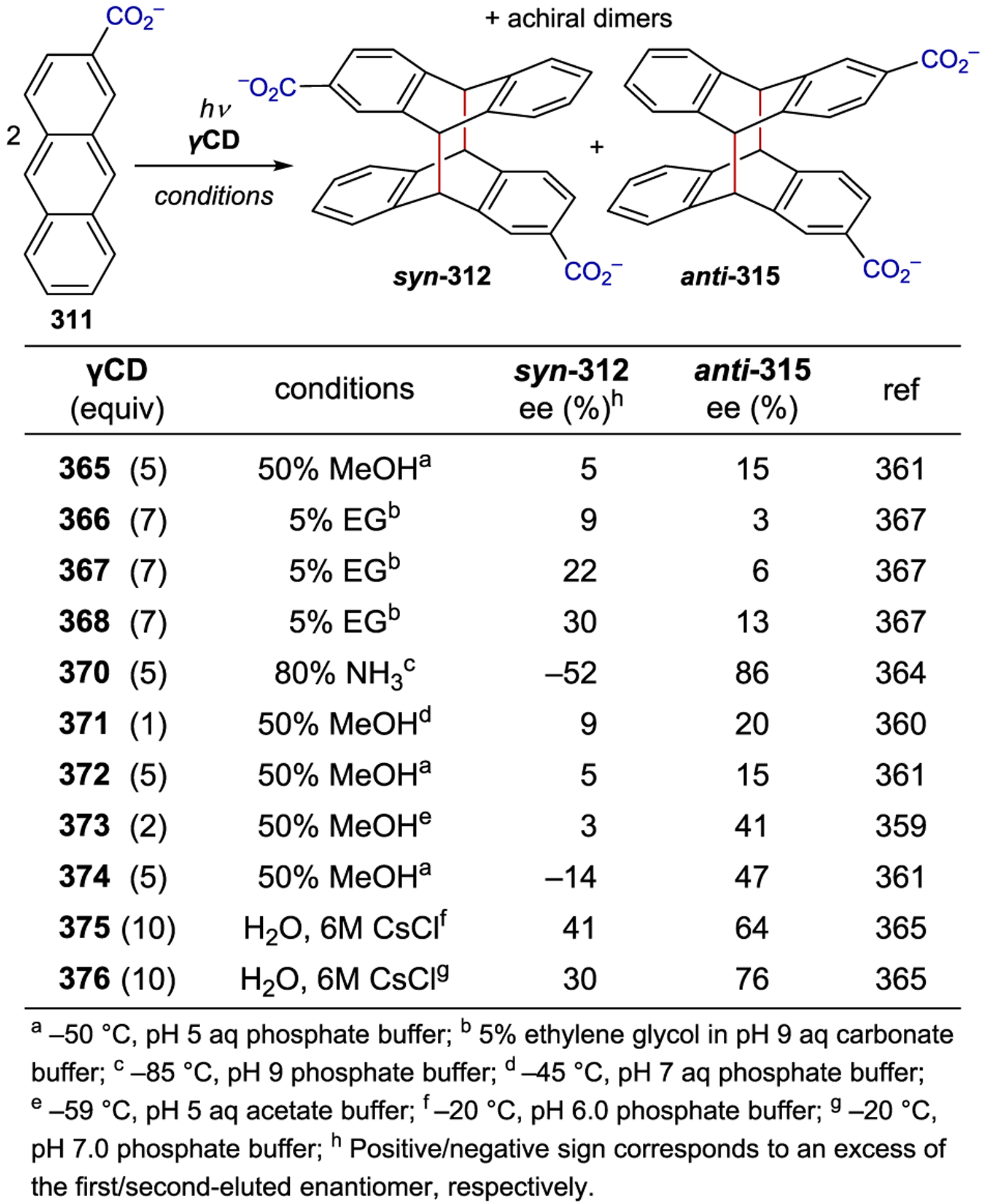

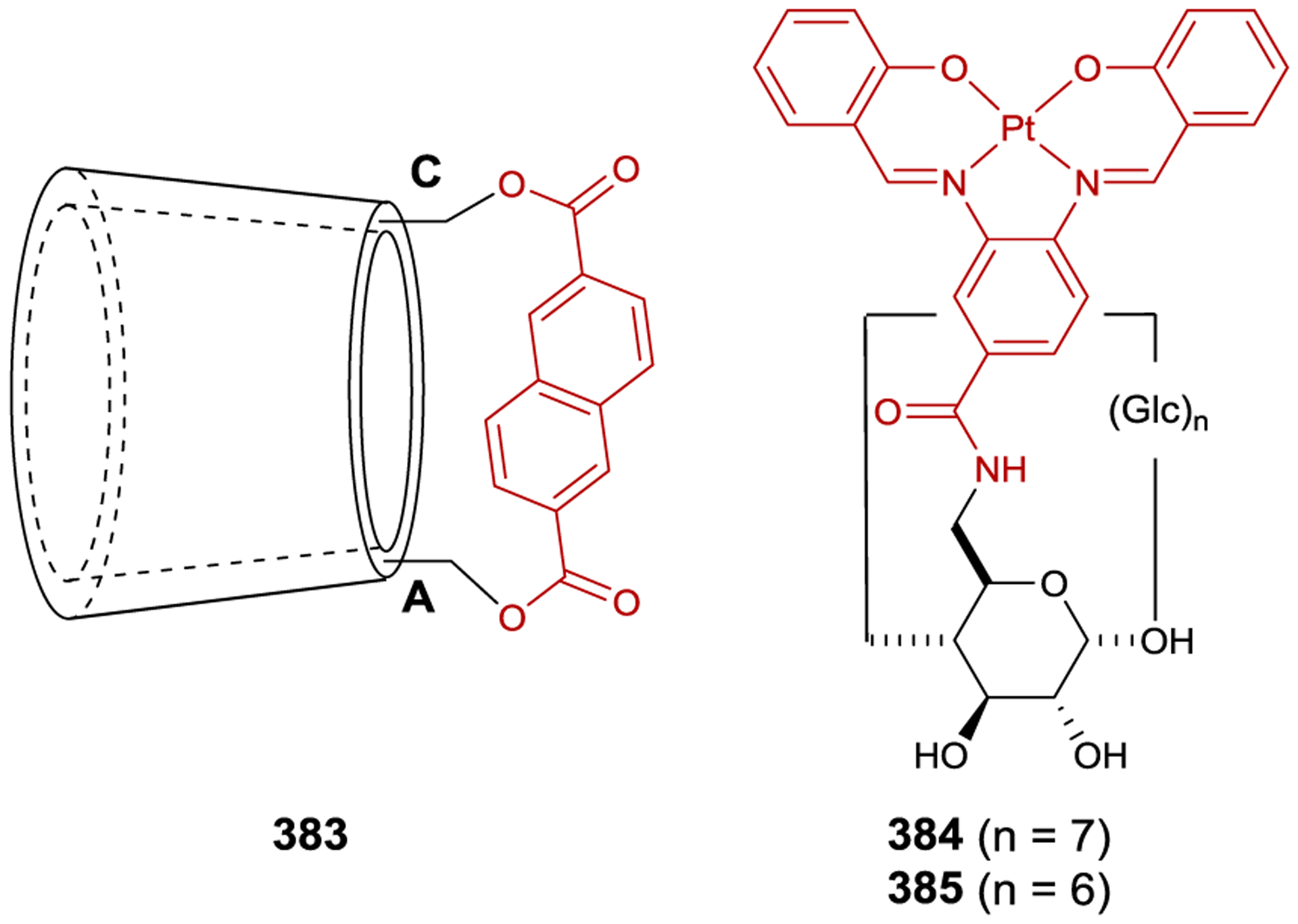

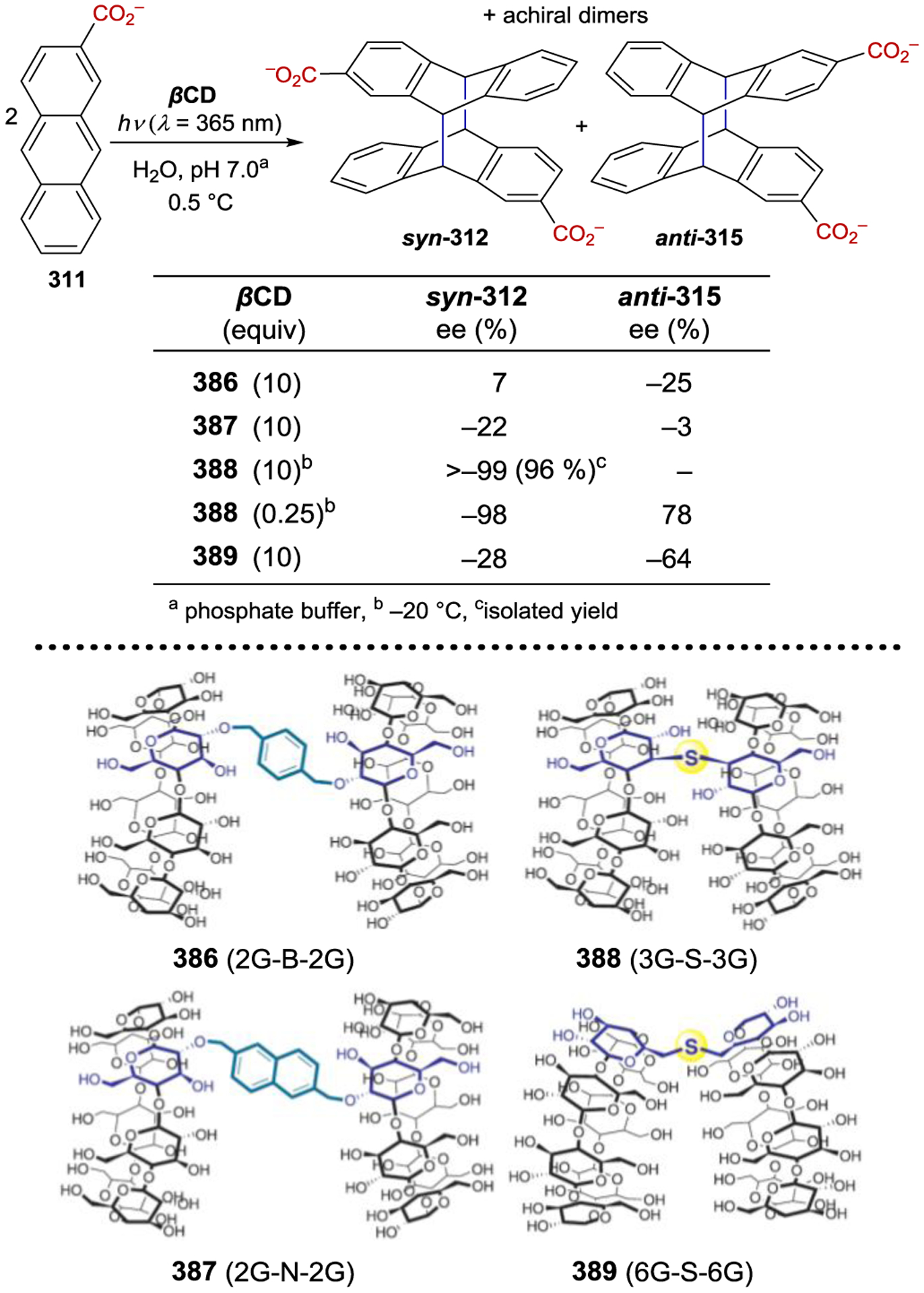

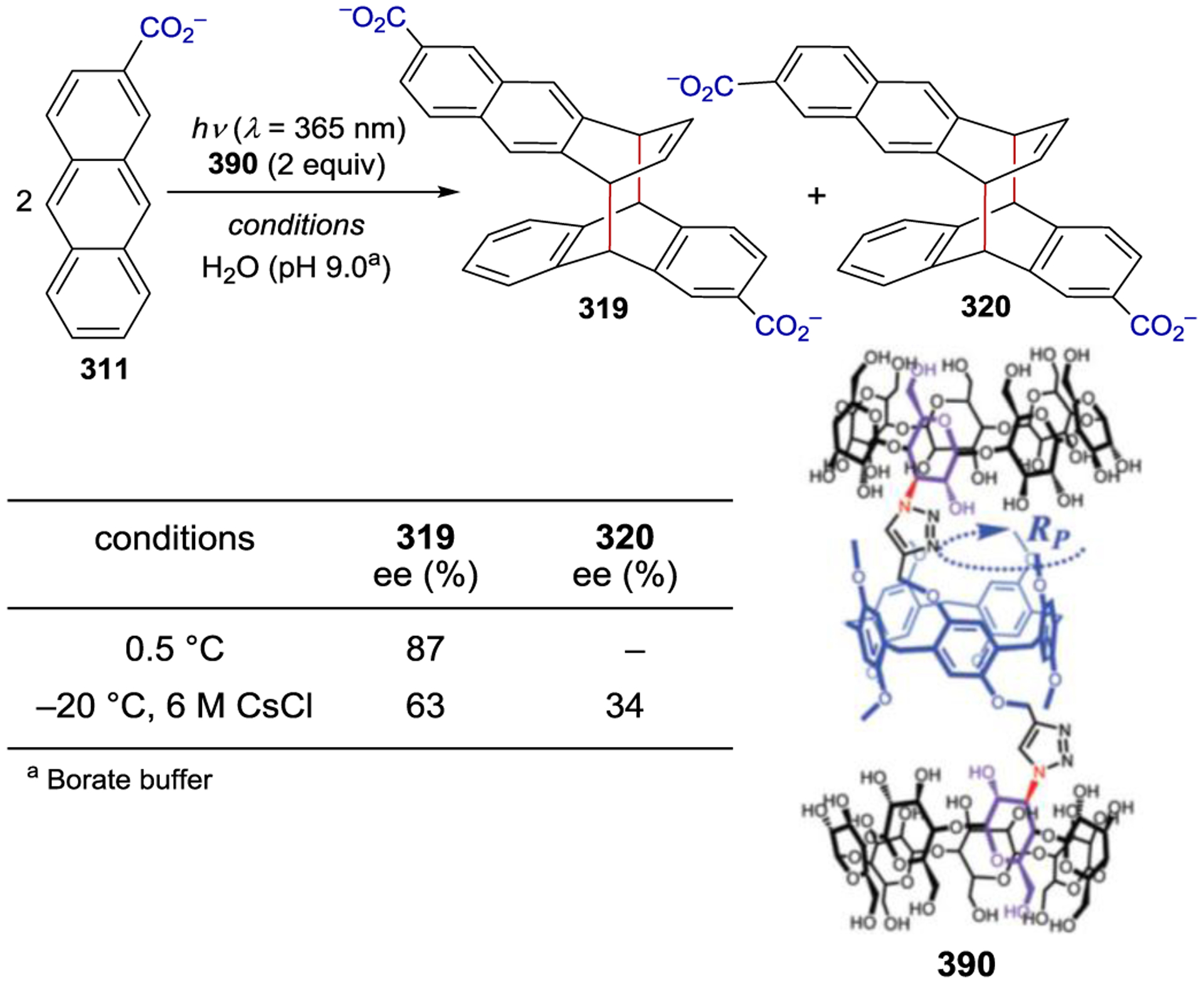

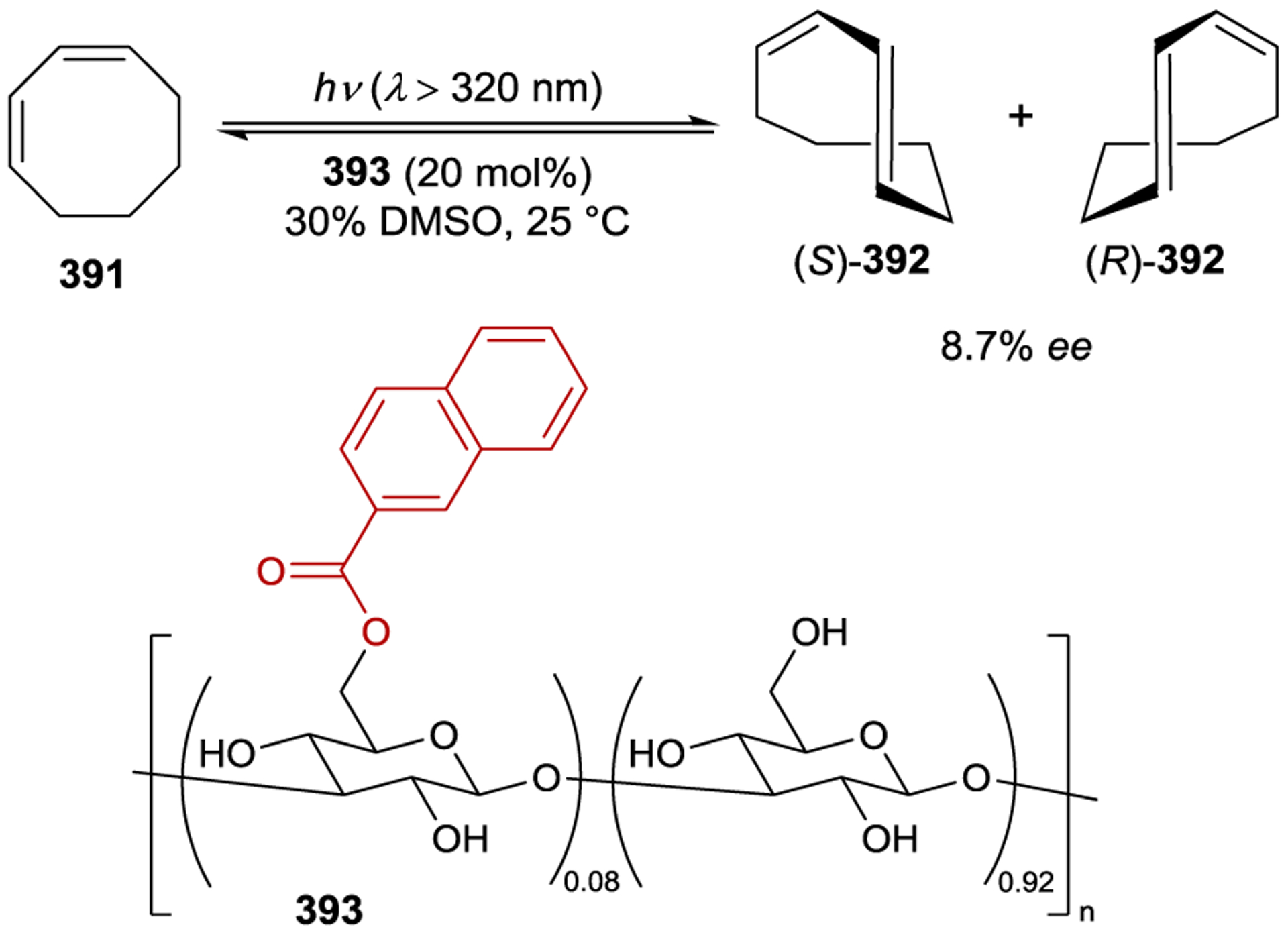

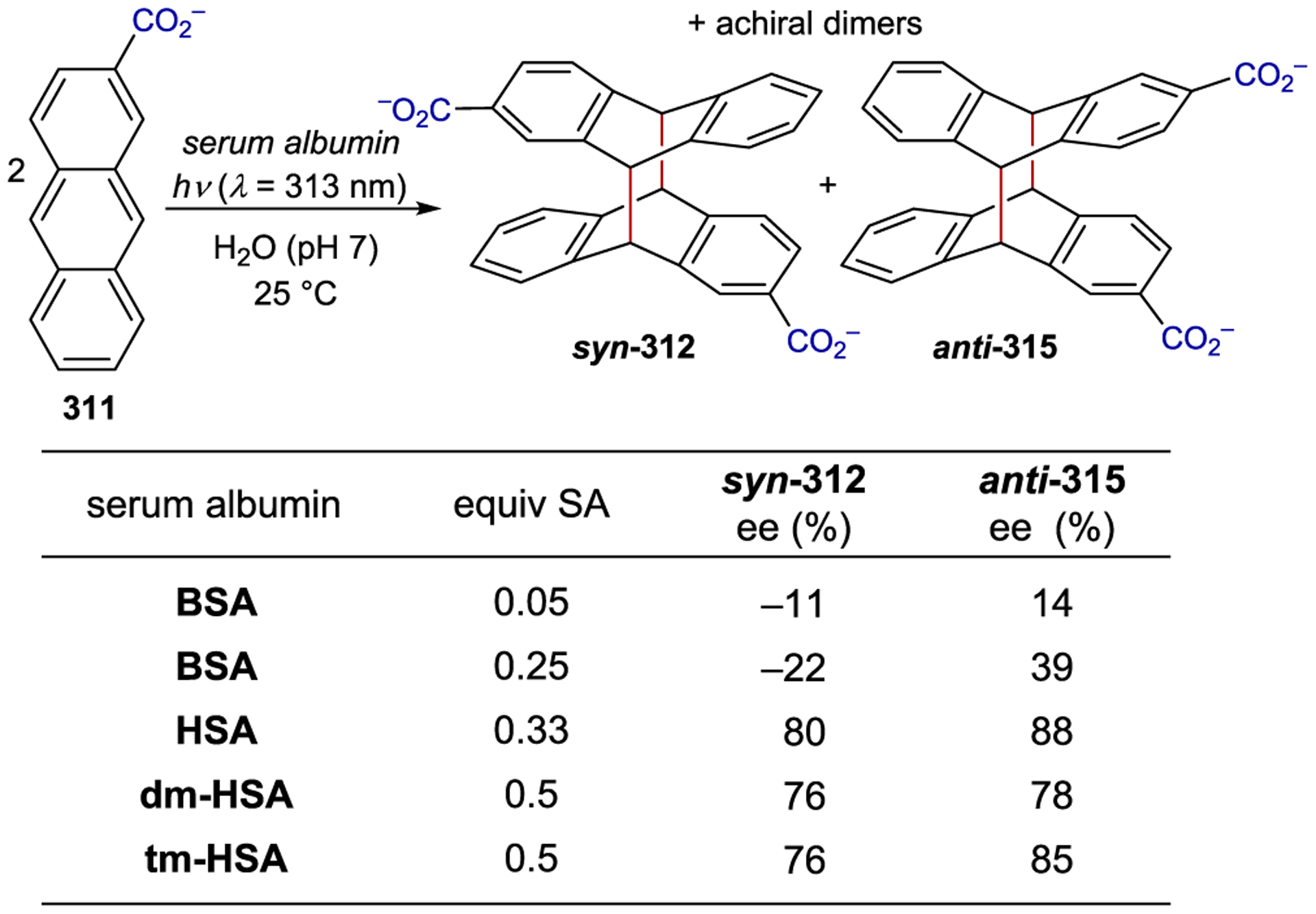

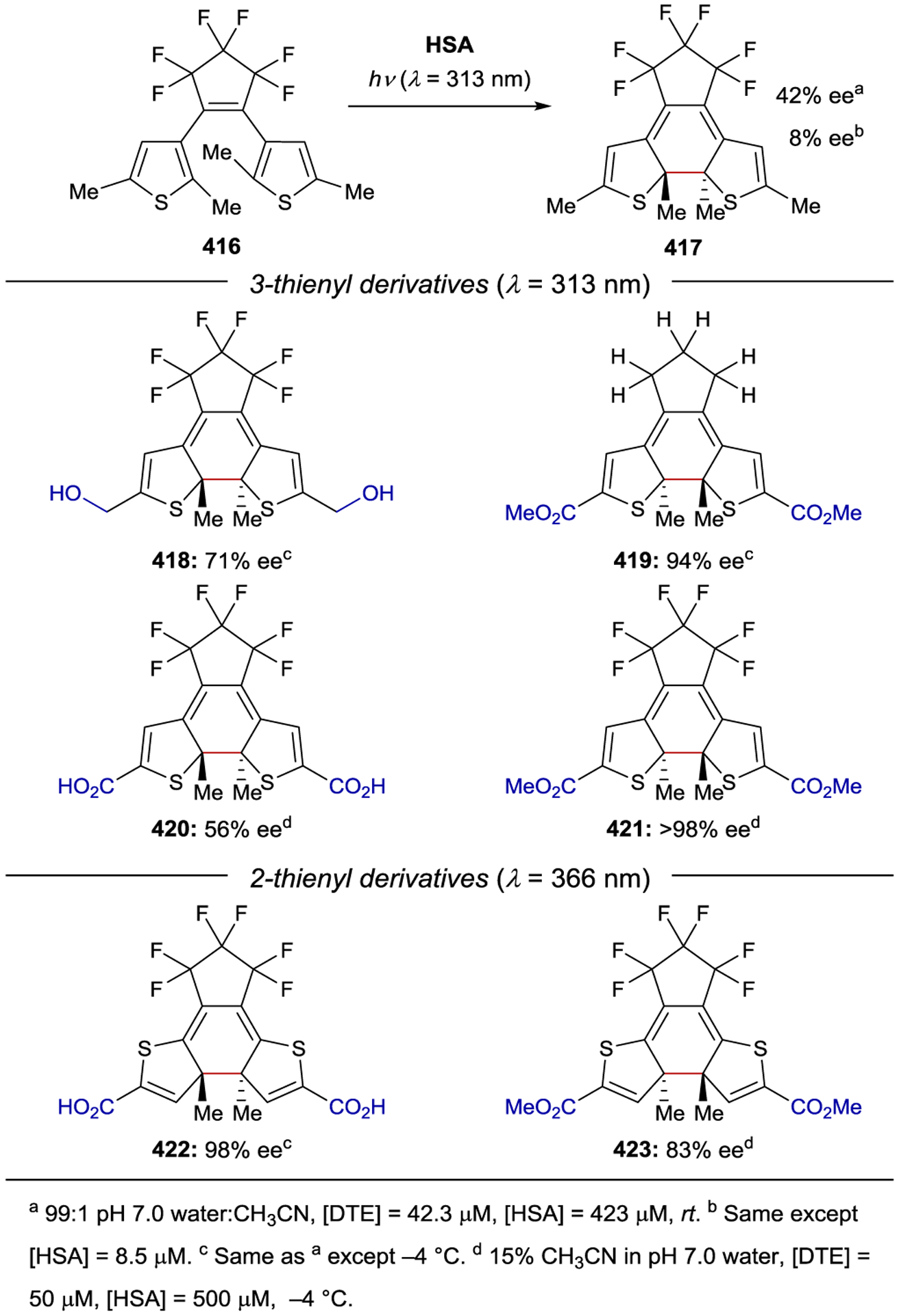

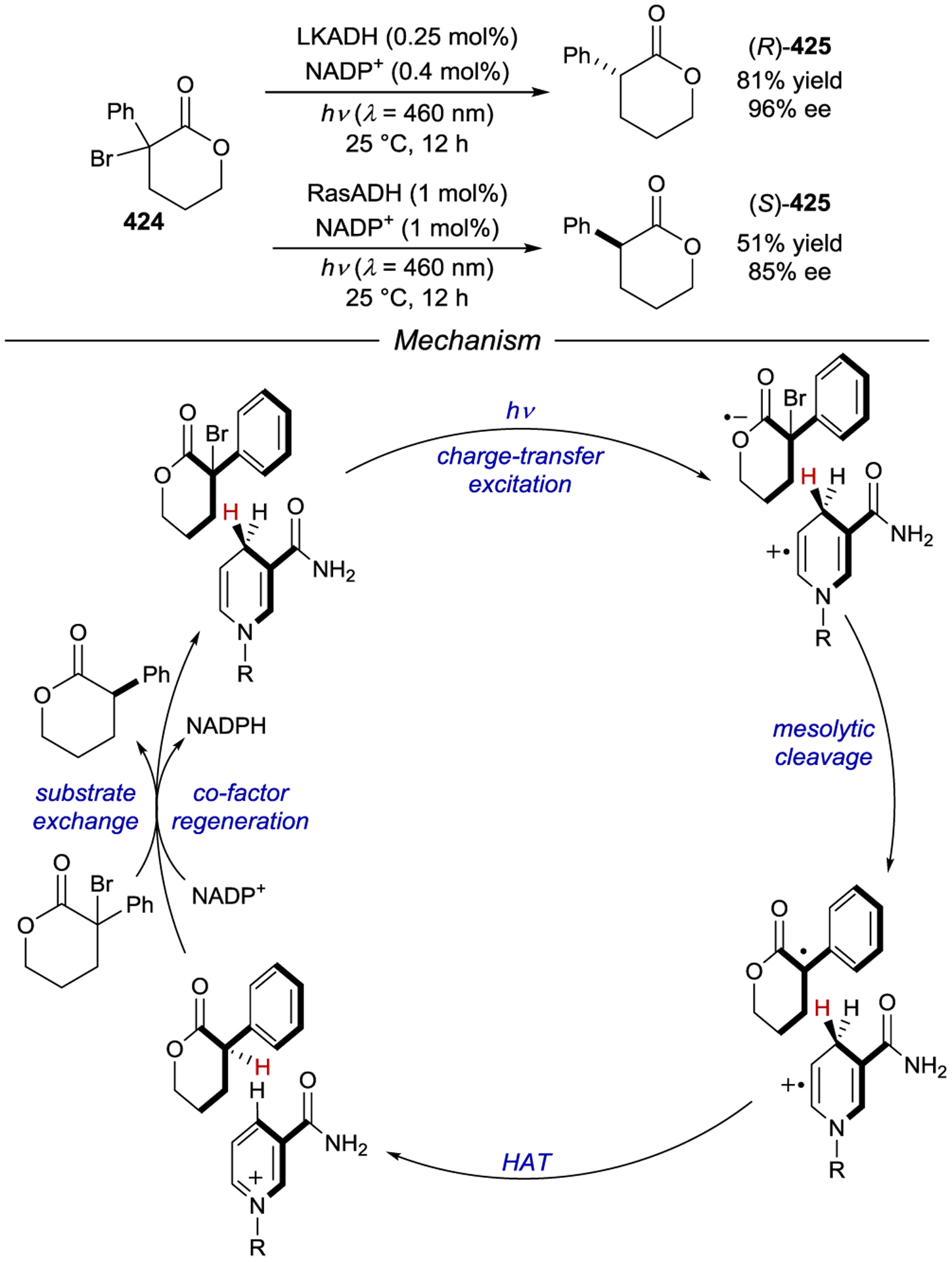

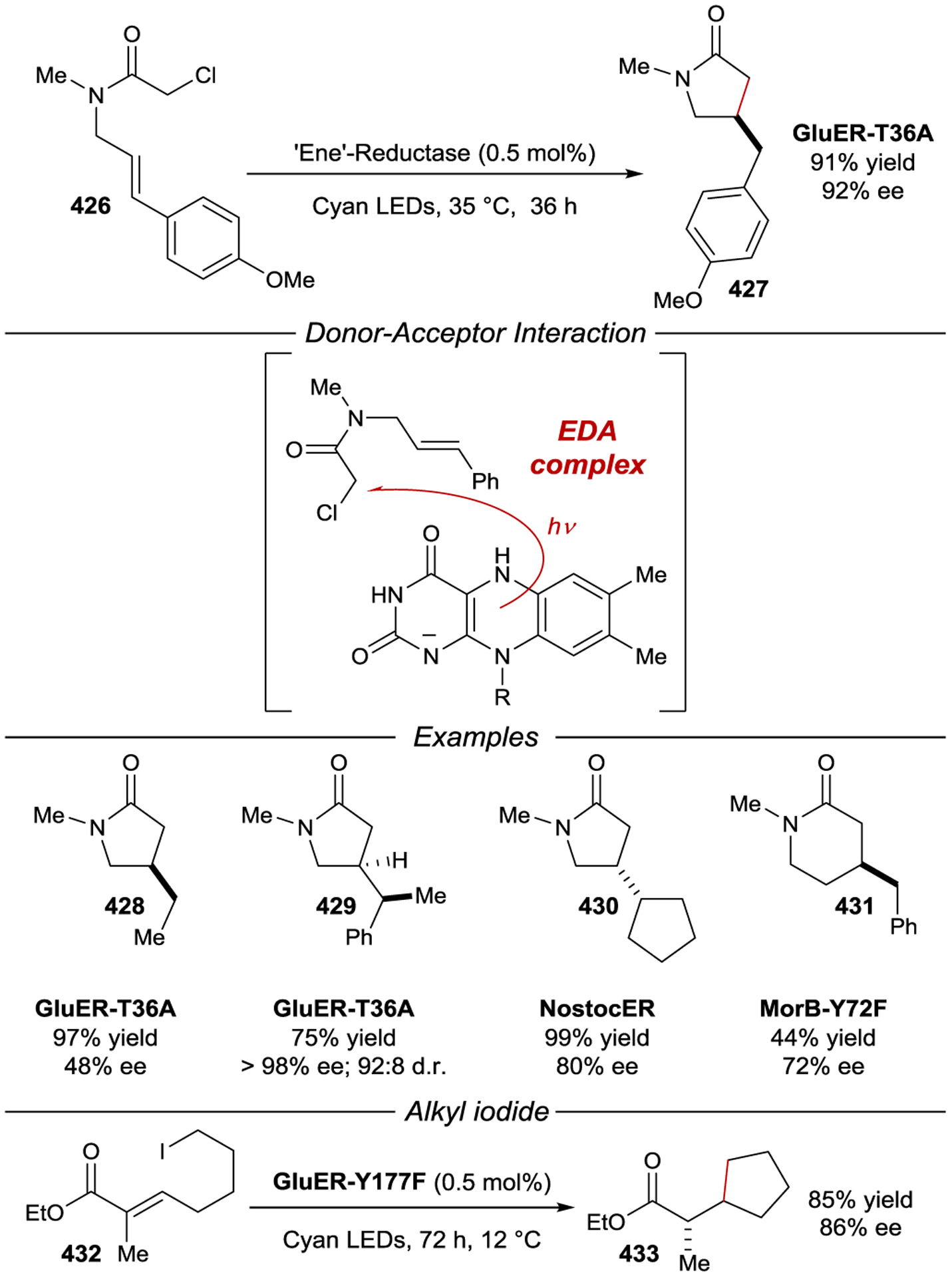

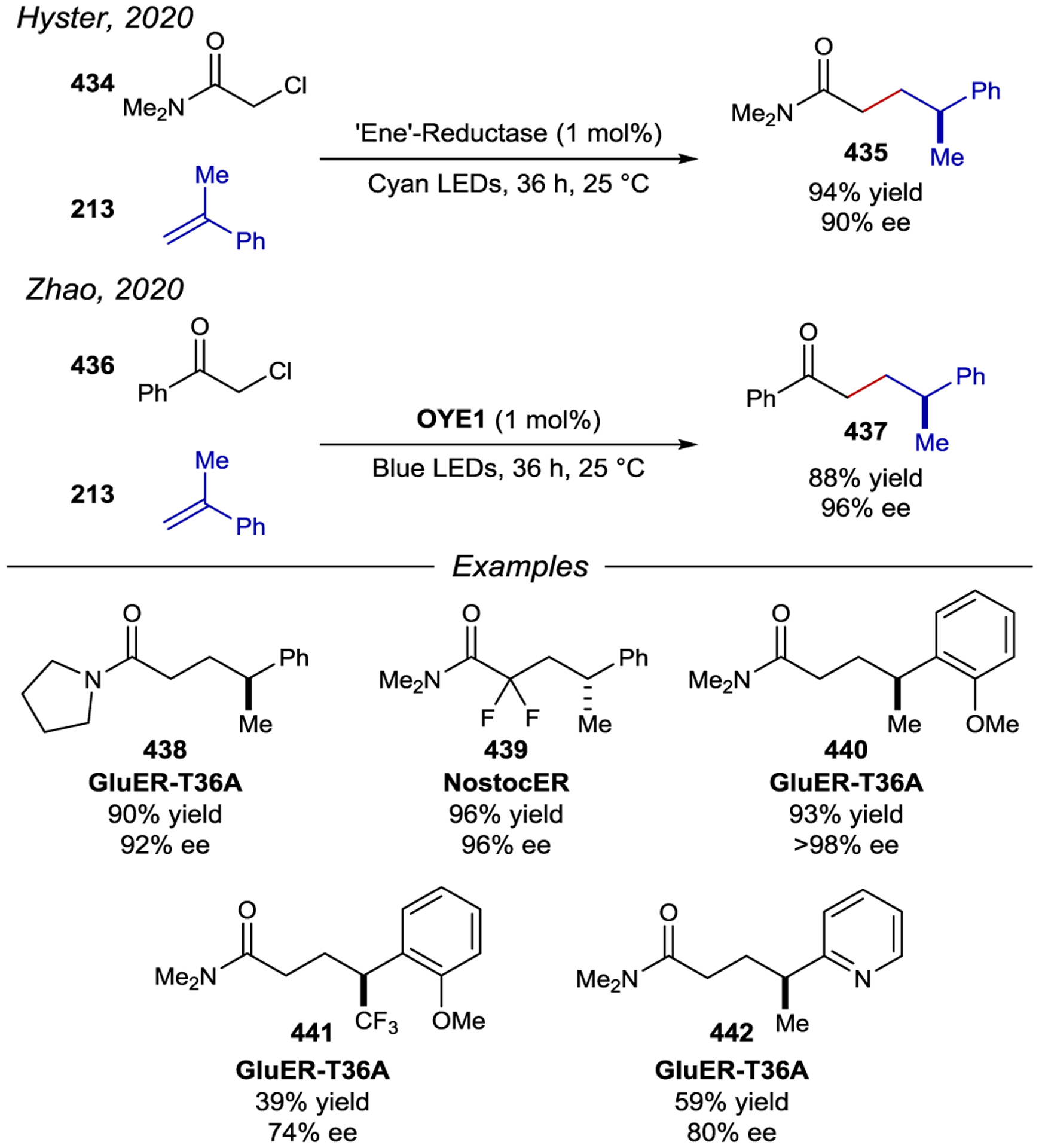

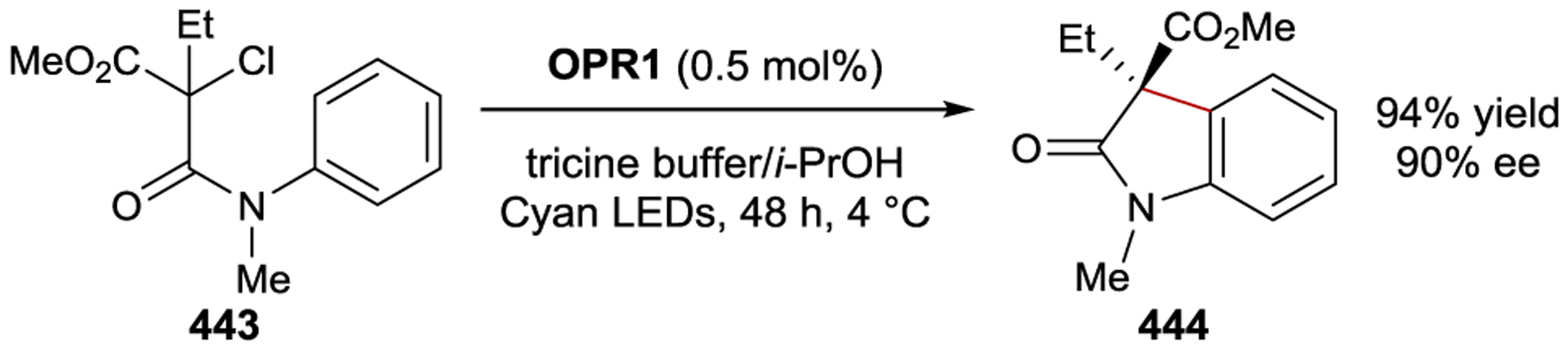

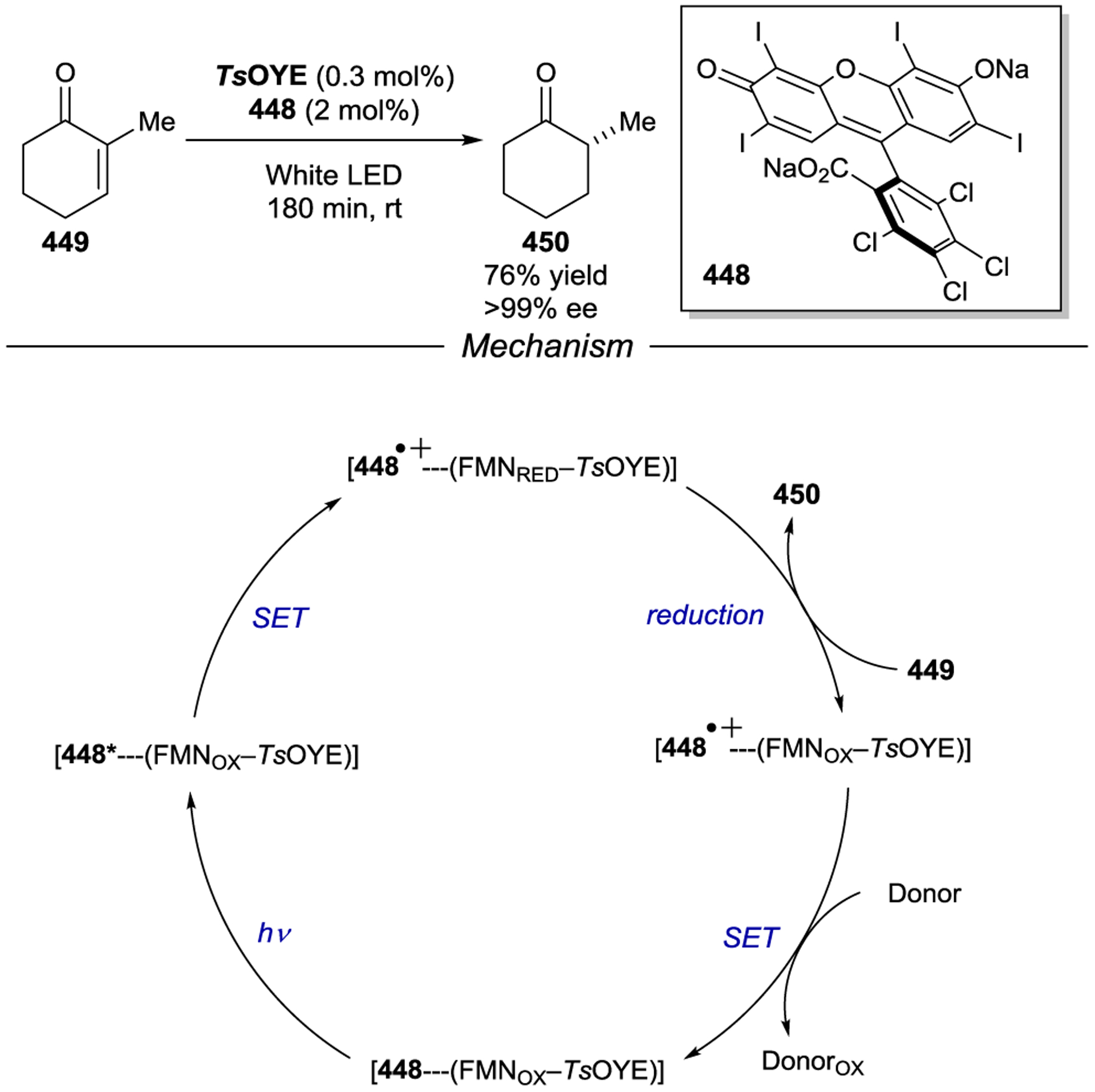

Scheme 59.