African relevance

-

•

Most Sub-Saharan African countries struggle with health information technology and thus lack accurate patient data.

-

•

Medical databases serve a critical function in assessing the quality of healthcare for a specific disease or within a specific healthcare delivery.

-

•

Healthcare data also provides a quantitative basis for the resource allocations, therefore, it is particularly essential to ensure the efficient management and delivery of health services in resource poor environments, like many African countries.

Keywords: Cameroon, Emergency center, Patient database

Abstract

Most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have struggled to utilize health information technology and thus lack in accurate patient data. This paper describes the method of collecting patient data and patient characteristics in an emergency centre in Yaoundé, Cameroon.

We developed an Epi InfoTM-based data entry form to collect data of the patients who visited the Centre des Urgences de Yaoundé (CURY) from January 2016 to June

2018. Demographic, clinical symptoms, treatments and outcome data were collected.

Additional data on the patients with multiple trauma, chest pain, sepsis/septic shock, and stroke were also collected.

During the study period, a total of 18,875 patients’ data were collected (44.5% women, median age of 36). Of the total patients, 2.4% had chest pain, 2.7% had stroke, 1.9% had sepsis/septic shock, and 1.6% had multiple trauma. About 6.0% patients received operation and majority of patients were discharged either normally (48.2%) or with continuity of care (26.3%). About 5.0% of patients were transferred to other hospital and 5.2% of patients were dead.

This study serves to broaden understanding of the emergency patients in Yaoundé, Cameroon.

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa is a resource-constrained region and faces a disproportionately large share of the world's burden of disease [1]. To make the situation worse, most countries in this region have struggled to utilize health information technology and thus lacks in accurate patient data. Availability of a good aggregated patient data is important at both management levels as well as for improved patient care and services, decision making and allocation of limited resources in most low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), particularly sub-Saharan Africa [2].

Cameroon faces significant challenges in the provision of health services, particularly in the field of emergency care. In effort to address the shortage of emergency care services, Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) and Cameroon's Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) signed a project agreement to construct a National Medico-Surgical Emergency Center in Yaoundé. The project proposal included the construction of the building, provision of necessary and appropriate equipment, provision of technical and managerial human resources, provision of practical training of emergency medicine, and development of guidelines for the operation and management of the center by KOICA. In June 2015, KOICA established Centre des Urgences de Yaoundé (CURY). Since its inception, CURY developed a hospital information system, but its utilization has been low and paper-based patient medical records were being used mostly. These paper-based patient medical records had very limited use in CURY. In order to aggregate the patient data and to further utilize the patient information, we used the Epi InfoTM [3] and aggregated the patient data. This paper describes the methods of CURY patient data collection and the characteristics of the patients visited CURY from January 2016 to June 2018.

Methods

Study setting

The Republic of Cameroon is a country located in Central Africa and has an estimated population of 25.8 million with life expectancy at birth of 62.4 years [4]. Gross national income per capita was estimated around 1,500 USD using the Atlas method in 2019 [5], and health spending was 3.5% of gross domestic product in 2018 [6]. Probability of dying from any of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases between age 30 and 70 was 23.9%, and road traffic mortality was 30.2 per 100,000 population [4].

The capital city of Cameroon, Yaoundé with a population of approximately 3.2 million, is the second largest city in the country. The healthcare system in Cameroon is characterized by the division of the country into health districts, which is the operational geographic unit responsible for providing primary healthcare to the population [7]. There are six health districts (Biyem Assi, Cité Verte, Djoungolo, Efoulan, Nkolbisson, and Nkoldongo) in Yaoundé with each health district providing coverage for between 4 and 12 health areas and their constituting communities [8].

As the national medico-surgical emergency center, CURY is entitled to receive all types of emergency patients. However, in Yaoundé, there are specialized maternity center and pediatric hospital that are designated for obstetric and pediatric patients, respectively, by the Cameroon MoPH. Therefore, CURY mainly receives adult, non-obstetric emergency patients. CURY is a stand-alone facility with 52 beds, all of which are exclusively for emergency care. Patients are triaged at the triage area using Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS). After triage, patients are first sent to one of the six units according to their CTAS levels; Resuscitation (level I), Major Trauma (level II with trauma), Major Non-trauma (level II without trauma), Main Treatment (level III), Minor Trauma (level IV and V with trauma), and Consultation (level IV and V without trauma). After receiving first evaluation and treatment from each unit, patients who need subsequent care are sent to one of the following areas; intensive care unit (ICU), sub-ICU, and observation unit. Since all the units in CURY are regarded as parts of the emergency center, patients move from one unit to another without any process for hospitalization, and eventually are either discharged home or transferred to other hospitals if they survive. Patients who need surgery are operated in the theatre within the emergency center.

CURY also has Service Mobile d'Urgence et de Reanimation (SMUR) which is mainly for interfacility transfer though it can also be dispatched to the scene of accidents when requested by the government or victims. CURY currently has 25 specialists and 26 general practitioners and over 400 other healthcare providers, including nurses.

Patient data collection

The database of the medical records of the patients who visited the CURY from January 2016 to June 2018 was collected using Epi InfoTM version 7.2 [3]. Epi InfoTM is a public domain computer program developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which provides easy data entry form and database construction and data analyses [9], [10]. The Epi InfoTM –based patient data entry form was developed by an emergency medicine specialist at CURY.

The data sources used were 1) CURY hospital information system, 2) paper format patient medical records, 3) deceased patient records, and 4) transferred patient records of SMUR. All the patient data were inputted into the Epi InfoTM by an employed medical doctor from March 2017 to July 2018. The patient data from January 2016 to February 2017 were collected retrospectively and data from March 2017 to June 2018 were collected prospectively. Data entered into the Epi InfoTM were then exported to the Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington).

Variables from each data sources

Each of the abovementioned data sources included the following variables:

-

1)

CURY hospital information system: Patient ID, patient name, sex, age, date and time of arrival, service destination, name of physician, chief complains, triage, type of patient (new or established), payment status (prepaid or not).

-

2)

Paper format patient medical records: Patient ID, patient name, date of birth, sex, age, telephone number, address, language, date and time of arrival, type of patient (new or established), past medical history, initial status of patient (vital signs, mental status, and triage category), mode of arrival, type of patient (trauma, or non-trauma), date and time of symptom onset, type of injury, injury mechanism, physical examination, diagnosis (including ICD-10 code), prescription, results (laboratory test, radiologic studies, ECG etc.), date of disposition, primary consultation department (department in charge of the patients), and mode of disposition.

If the patients were injured from motor vehicle accidents (MVA), the following variables were collected in addition: Type of MVA (vehicle, motorbike, or bicycle), and location of the MVA patient (driver, passenger, pedestrian, or others/unknown).

-

1)

Deceased patient records: Date and time of death, patient name, age, sex, diagnosis

-

2)

Transferred patient records: Patient ID, patient name, sex, age, diagnosis, modes of arrival, name of the transferring hospital, payment, status (alive or dead), and disposition.

Final variables collected into the Epi InfoTM

Using above four data resources, we aggregated each patient's data into Epi InfoTM and collected following variables (Appendix 1): Patient ID, patient name, age, sex, date of birth, date and time of arrival, mode of arrival, payment, language, date and time of symptom onset, past medical history (hypertension, diabetes, tuberculosis, HIV, cerebrovascular disease, cardiac disease, other/unknown, no known disease), initial status of patients (chief complaint, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate, temperature, oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, blood glucose level, mental status), triage level based on the CTAS, location of patient, type of patient (trauma, non-trauma, unknown), derived from (direct visit, referred from hospital, referred from other department, others/unknown), operation status (yes/no), final diagnosis, result, and date and time of discharge.

We also categorized multiple trauma, chest pain, sepsis/septic shock, and stroke as critical diseases/symptoms and collected the following additional data on the patients with those conditions.

-

1)

Multiple trauma: Intention, mechanism of trauma, and type of MVA for those with MVA as mechanism of trauma.

-

2)

Chest pain: Pain onset time, presumed acute coronary syndrome/coronary artery disease (ACS/CAD) status, ST elevation status, reperfusion therapy and time.

-

3)

Sepsis/septic shock: Laboratory results (white blood cell, neutrophil, platelet, total bilirubin, creatinine, CRP, and prothrombin time)

-

4)

Stroke: CT check time, hemorrhagic status, reperfusion therapy status (yes/no), time and date of reperfusion therapy.

Quality assurance of the input data

The quality of the data that were entered into the Epi InfoTM were assured by the statistics team at the Laboratory of Emergency Medical Services, Seoul National University Hospital. Monthly quality control results and feedback were provided to the coding staff at CURY so they can be reflected in the data input.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed and statistical significance of the differences were analyzed with chi-squared test. P-values were calculated based on a two-sided significance level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

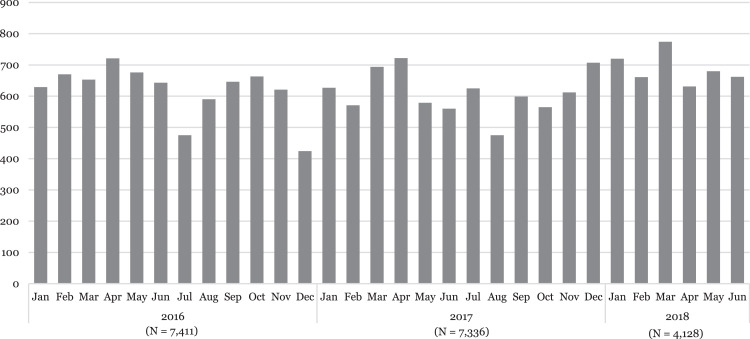

During the years 2016 and 2017, a total of 8,225 and 7,400 patients visited CURY, respectively. In the first half of 2018 (01 January to 30 June), 4,212 patients visited CURY. The average monthly number of CURY visits from 2016 to 2018 were 685, 617, and 702 patients, respectively. During the data collection period from January 2016 to June 2018, a total of 18,875 patients’ data were collected. The monthly distribution of the patients is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Number of CURY Visits Included in the Database from January 2016 to June 2018.

Demographic characteristics of the CURY patients

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the CURY visit patients during the study period and by each year. Overall, 55.5% were males. Majority of patients were adult patients in their 20s (22.5%), 30s (20.4%), and 40s (14.0%) with a median age of the patients being 36 years old. From years 2016 to 2018, there was a trend of increasing number of older patients visiting CURY with 2.2% of the patients aged 80 and older in 2016 and 3.6% in 2018. Number of patients visited CURY were evenly distributed throughout the week and days with slightly more patients on Mondays (15.3%) and during daytime (55.0%). The main mode of arrival to CURY was by public transportation (49.3%), followed by private car (27.7%). The proportion of public transportation use increased from 41.7% in 2016 to 65.1% in 2018. Most CURY patients were French speaking (96.6%) and about 0.3% of the total patients had insurance.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the CURY visit patients

| Total |

Year |

p-value* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Total | 18,875 | (100.0) | 7,411 | (39.2) | 7,336 | (38.9) | 4,128 | (21.9) | |

| Sex | 0.07 | ||||||||

| Female | 8,404 | (44.5) | 3,312 | (44.7) | 3,201 | (43.6) | 1,891 | (45.8) | |

| Male | 10,471 | (55.5) | 4,099 | (55.3) | 4,135 | (56.4) | 2,237 | (54.2) | |

| Age | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 0-9 | 778 | (4.1) | 337 | (4.5) | 287 | (3.9) | 154 | (3.7) | |

| 10-19 | 1,781 | (9.4) | 692 | (9.3) | 700 | (9.5) | 389 | (9.4) | |

| 20-29 | 4,245 | (22.5) | 1,724 | (23.3) | 1,650 | (22.5) | 871 | (21.1) | |

| 30-39 | 3,847 | (20.4) | 1,540 | (20.8) | 1,459 | (19.9) | 848 | (20.5) | |

| 40-49 | 2,643 | (14.0) | 1,037 | (14.0) | 1,042 | (14.2) | 564 | (13.7) | |

| 50-59 | 2,211 | (11.7) | 899 | (12.1) | 854 | (11.7) | 458 | (11.1) | |

| 60-69 | 1,761 | (9.3) | 638 | (8.6) | 703 | (9.6) | 420 | (10.2) | |

| 70-79 | 1,067 | (5.7) | 374 | (5.1) | 425 | (5.8) | 268 | (6.5) | |

| 80 and older | 519 | (2.8) | 163 | (2.2) | 207 | (2.8) | 149 | (3.6) | |

| Unknown/missing | 23 | (0.1) | 7 | (0.1) | 9 | (0.1) | 7 | (0.2) | |

| Week | 0.07 | ||||||||

| Sunday | 2,801 | (14.8) | 1,090 | (14.7) | 1,158 | (15.8) | 553 | (13.4) | |

| Monday | 2,876 | (15.3) | 1,123 | (15.2) | 1,120 | (15.2) | 633 | (15.3) | |

| Tuesday | 2,614 | (13.9) | 1,046 | (14.1) | 996 | (13.6) | 572 | (13.9) | |

| Wednesday | 2,531 | (13.4) | 979 | (13.2) | 993 | (13.5) | 559 | (13.5) | |

| Thursday | 2,603 | (13.8) | 994 | (13.4) | 1,012 | (13.8) | 597 | (14.5) | |

| Friday | 2,688 | (14.2) | 1,044 | (14.1) | 1,025 | (14.0) | 619 | (15.0) | |

| Saturday | 2,762 | (14.6) | 1,135 | (15.3) | 1,032 | (14.1) | 595 | (14.4) | |

| Day | 0.005 | ||||||||

| Day (06:00∼17:59) | 10,388 | (55.0) | 4,104 | (55.4) | 4,102 | (55.9) | 2,182 | (52.9) | |

| Night (18:00∼05:59) | 8,487 | (45.0) | 3,307 | (44.6) | 3,234 | (44.1) | 1,946 | (47.1) | |

| Modes of Visit | <0.001 | ||||||||

| SAMU/SMUR | 89 | (0.5) | 43 | (0.6) | 30 | (0.4) | 16 | (0.4) | |

| Hospital/other ambulance | 484 | (2.6) | 182 | (2.4) | 193 | (2.7) | 109 | (2.6) | |

| Public transportation | 9,313 | (49.3) | 3,089 | (41.7) | 3,538 | (48.2) | 2,686 | (65.1) | |

| Private car | 5,232 | (27.7) | 2,084 | (28.1) | 2,077 | (28.3) | 1,071 | (25.9) | |

| Other/unknown | 3,757 | (19.9) | 2,013 | (27.2) | 1,498 | (20.4) | 246 | (6.0) | |

| Language | <0.001 | ||||||||

| French | 18,231 | (96.6) | 7,032 | (94.9) | 7,083 | (96.6) | 4,116 | (99.7) | |

| English | 43 | (0.2) | 12 | (0.2) | 30 | (0.4) | 1 | (0.0) | |

| Other/unknown | 601 | (3.2) | 367 | (4.9) | 223 | (3.0) | 11 | (0.3) | |

| Payment | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Prepaid | 15,570 | (82.5) | 6,006 | (81.1) | 6,067 | (82.7) | 3,497 | (84.7) | |

| Insurance | 61 | (0.3) | 17 | (0.2) | 27 | (0.4) | 17 | (0.4) | |

| Others | 2,561 | (13.6) | 915 | (12.3) | 1,035 | (14.1) | 611 | (14.8) | |

| Unknown/missing | 683 | (3.6) | 473 | (6.4) | 207 | (2.8) | 3 | (0.1) | |

* P-value based on the chi-square, except Language and Payment, which were based on the fisher's exact test.

Abbreviations: SAMU=service d'aide médicale urgente; SMUR= Service Mobile d'Urgence et de Reanimation

Clinical characteristics of the CURY patients

Clinical characteristics of the CURY visit patients are described in Table 2. Overall, 10.8% of the total patients had hypertension. The rate of patients with hypertension increased from 8.0% in 2016 to 13.3% in 2018 (p<0.001). Patients with other past medical history, including diabetes, tuberculosis, HIV, stroke, and cardiac diseases also increased from 2016 to 2018 (p<0.05 for all). Of the total CURY visit patients, 39.7% were trauma patients. Overall, internal medicine department was in charge of 29.9% of the patients, traumatology department were in charge of 22.8% of the total patients. Also, 3.6%, 8.6%, and 9.7% of the patients were assigned to general surgery, neurosurgery, and orthopedic surgery departments, respectively. Over 86.0% of the patients visited CURY with mental status categorized as “Alert”. From 2016 to 2018, the proportion of patients with “Unresponsive” as well as CTAS Level 1 (most severe) increased by more than twice (from 3.1% to 7.2% for “Unresponsive” and from 3.7% to 8.0% for CTAS Level 1). Of the total patients, about 2.4% had chest pain, 2.7% had stroke, 1.9% had sepsis/septic shock, and 1.6% had multiple trauma. The overall rate of patients receiving operation was 6.0%. Majority of patients were discharged either normally (48.2%) or with continuity of care (26.3%). About 5.0% of patients were transferred to other hospital and about 5.2% of patients were dead.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the CURY visit patients.

| Total |

Year |

p-value* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Total | 18,875 | (100.0) | 7,411 | (39.3) | 7,336 | (38.9) | 4,128 | (21.9) | |

| Past Medical History | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 2,030 | (10.8) | 591 | (8.0) | 892 | (12.2) | 547 | (13.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 871 | (4.6) | 282 | (3.8) | 356 | (4.9) | 233 | (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Tuberculosis | 52 | (0.3) | 11 | (0.1) | 24 | (0.3) | 17 | (0.4) | 0.02 |

| HIV | 327 | (1.7) | 131 | (1.8) | 90 | (1.2) | 106 | (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 210 | (1.1) | 50 | (0.7) | 92 | (1.3) | 68 | (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac Diseases | 174 | (0.9) | 50 | (0.7) | 73 | (1.0) | 51 | (1.2) | 0.01 |

| Trauma | |||||||||

| Yes | 7,488 | (39.7) | 2,997 | (40.4) | 2,847 | (38.8) | 1,644 | (39.8) | <0.001 |

| Primary Consultation Department | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Internal Medicine | 5,650 | (29.9) | 2,324 | (31.4) | 1,987 | (27.1) | 1,339 | (32.4) | |

| General Surgery | 673 | (3.6) | 260 | (3.5) | 273 | (3.7) | 140 | (3.4) | |

| Gynecology | 201 | (1.0) | 91 | (1.2) | 79 | (1.1) | 31 | (0.8) | |

| Neurosurgery | 1,618 | (8.6) | 444 | (6.0) | 767 | (10.4) | 407 | (9.9) | |

| Orthopedic Surgery | 1,825 | (9.7) | 613 | (8.3) | 798 | (10.9) | 414 | (10.0) | |

| Traumatology | 4,303 | (22.8) | 2,005 | (27.0) | 1,299 | (17.7) | 999 | (24.2) | |

| Other/unknown/missing | 4,605 | (24.4) | 1,674 | (22.6) | 2,133 | (29.1) | 798 | (19.3) | |

| Mental Status | <0.001 | ||||||||

| A | 16,225 | (86.0) | 6,436 | (86.8) | 6,319 | (86.1) | 3,470 | (84.1) | |

| V | 546 | (2.9) | 127 | (1.7) | 228 | (3.1) | 191 | (4.6) | |

| P | 377 | (2.0) | 146 | (2.0) | 115 | (1.6) | 116 | (2.8) | |

| U | 883 | (4.7) | 227 | (3.1) | 358 | (4.9) | 298 | (7.2) | |

| Unknown | 844 | (4.4) | 475 | (6.4) | 316 | (4.3) | 53 | (1.3) | |

| CTAS | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Level 1 | 999 | (5.3) | 271 | (3.7) | 397 | (5.4) | 331 | (8.0) | |

| Level 2 | 5,839 | (30.9) | 2,229 | (30.1) | 2,252 | (30.7) | 1,358 | (32.9) | |

| Level 3 | 7,593 | (40.2) | 3,123 | (42.1) | 2,848 | (38.8) | 1,622 | (39.3) | |

| Level 4 | 3,108 | (16.5) | 1,192 | (16.1) | 1,166 | (15.9) | 750 | (18.2) | |

| Level 5 | 362 | (1.9) | 152 | (2.0) | 198 | (2.7) | 12 | (0.3) | |

| Unknown/missing | 974 | (5.2) | 444 | (6.0) | 475 | (6.5) | 55 | (1.3) | |

| Critical Symptoms/Diseases | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Presumed ACS/CAD | 448 | (2.4) | 203 | (2.7) | 151 | (2.1) | 94 | (2.3) | |

| Stroke | 509 | (2.7) | 142 | (1.9) | 204 | (2.8) | 163 | (3.9) | |

| Sepsis/Septic shock | 362 | (1.9) | 139 | (1.9) | 128 | (1.7) | 95 | (2.3) | |

| Multiple trauma | 294 | (1.6) | 129 | (1.7) | 117 | (1.6) | 48 | (1.2) | |

| Operation | |||||||||

| Yes | 1,129 | (6.0) | 436 | (5.9) | 444 | (6.1) | 249 | (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Result | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Normal discharge | 9,090 | (48.2) | 3,699 | (49.9) | 3,813 | (52.0) | 1,578 | (38.2) | |

| Discharge with continuity of care | 4,967 | (26.3) | 1,503 | (20.3) | 1,751 | (23.9) | 1,713 | (41.5) | |

| Hopeless discharge | 2 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Transfer to other hospital | 949 | (5.0) | 298 | (4.0) | 423 | (5.8) | 228 | (5.5) | |

| Treatment refusal | 389 | (2.1) | 145 | (2.0) | 150 | (2.0) | 94 | (2.3) | |

| Death | 980 | (5.2) | 291 | (3.9) | 453 | (6.2) | 236 | (5.7) | |

| Other/unknown | 2,498 | (13.2) | 1,475 | (19.9) | 744 | (10.1) | 279 | (6.8) | |

*P-value based on the chi-square, except Result, which was based on the fisher's exact test.

Abbreviations: HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; A=alert; V=voice; P=pain; U=unresponsive; CTAS=Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale; ACS=acute coronary syndrome; CAD=coronary artery disease

Characteristics of the CURY patients with critical symptoms/diseases

Of the total patients, 8.5% were categorized having critical symptoms/diseases of either chest pain, stroke, sepsis/septic shock, or multiple trauma. Table 3 describes the characteristics of these patients with critical symptoms/diseases.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the patients with critical symptoms/diseases.

| Total |

Critical Symptoms/Diseases |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Critical Symptoms/Diseases |

Chest Pain |

Stroke |

Sepsis/Septic Shock |

Multiple Trauma |

|||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Total | 18,875 | (100.0) | 17,262 | (91.5) | 448 | (2.4) | 509 | (2.7) | 362 | (1.9) | 294 | (1.5) | |

| Year | |||||||||||||

| 2016 | 7,411 | (39.2) | 6,798 | (39.4) | 203 | (45.3) | 142 | (27.9) | 139 | (38.4) | 129 | (43.9) | |

| 2017 | 7,336 | (38.9) | 6,736 | (39.0) | 151 | (33.7) | 204 | (40.1) | 128 | (35.4) | 117 | (39.8) | |

| 2018 | 4,128 | (21.9) | 3,728 | (21.6) | 94 | (21.0) | 163 | (32.0) | 95 | (26.2) | 48 | (16.3) | |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Female | 8,404 | (44.5) | 7,661 | (44.4) | 185 | (41.3) | 273 | (53.6) | 206 | (56.9) | 79 | (26.9) | |

| Male | 10,471 | (55.5) | 9,601 | (55.6) | 263 | (58.7) | 236 | (46.4) | 156 | (43.1) | 215 | (73.1) | |

| Age | |||||||||||||

| 0-9 | 778 | (4.1) | 764 | (4.4) | 3 | (0.7) | - | (0.0) | 1 | (0.3) | 10 | (3.4) | |

| 10-19 | 1,781 | (9.4) | 1,713 | (9.9) | 25 | (5.6) | 1 | (0.2) | 12 | (3.3) | 30 | (10.2) | |

| 20-29 | 4,245 | (22.5) | 4,032 | (23.4) | 79 | (17.6) | 5 | (1.0) | 31 | (8.6) | 98 | (33.3) | |

| 30-39 | 3,847 | (20.4) | 3,605 | (20.9) | 97 | (21.7) | 14 | (2.8) | 61 | (16.9) | 70 | (23.8) | |

| 40-49 | 2,643 | (14.0) | 2,381 | (13.8) | 88 | (19.6) | 78 | (15.3) | 58 | (16.0) | 38 | (12.9) | |

| 50-59 | 2,211 | (11.7) | 1,947 | (11.3) | 73 | (16.3) | 111 | (21.8) | 53 | (14.6) | 27 | (9.2) | |

| 60-69 | 1,761 | (9.3) | 1,508 | (8.7) | 50 | (11.2) | 140 | (27.5) | 51 | (14.1) | 12 | (4.1) | |

| 70-79 | 1,067 | (5.7) | 878 | (5.1) | 23 | (5.1) | 100 | (19.6) | 59 | (16.3) | 7 | (2.4) | |

| 80 and older | 519 | (2.8) | 414 | (2.4) | 9 | (2.0) | 60 | (11.8) | 34 | (9.4) | 2 | (0.7) | |

| Unknown/missing | 23 | (0.1) | 20 | (0.1) | 1 | (0.2) | - | (0.0) | 2 | (0.5) | - | (0.0) | |

| Day | |||||||||||||

| Day (0600∼1759) | 10,388 | (55.0) | 9,534 | (55.2) | 246 | (54.9) | 277 | (54.4) | 208 | (57.5) | 123 | (41.8) | |

| Night (1800∼0559) | 8,487 | (45.0) | 7,728 | (44.8) | 202 | (45.1) | 232 | (45.6) | 154 | (42.5) | 171 | (58.2) | |

| Modes of Visit | |||||||||||||

| SAMU/SMUR | 89 | (0.5) | 80 | (0.5) | 4 | (0.9) | 1 | (0.2) | 2 | (0.6) | 2 | (0.7) | |

| Hospital/other ambulance | 484 | (2.6) | 375 | (2.2) | 13 | (2.9) | 27 | (5.3) | 34 | (9.4) | 35 | (11.9) | |

| Public transportation | 9,313 | (49.3) | 8,565 | (49.6) | 201 | (44.9) | 236 | (46.4) | 173 | (47.8) | 138 | (46.9) | |

| Private car | 5,232 | (27.7) | 4,752 | (27.5) | 144 | (32.1) | 176 | (34.6) | 100 | (27.6) | 60 | (20.4) | |

| Other/unknown | 3,757 | (19.9) | 3,490 | (20.2) | 86 | (19.2) | 69 | (13.6) | 53 | (14.6) | 59 | (20.1) | |

| Past Medical History | |||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 2,030 | (10.8) | 1,585 | (9.2) | 77 | (17.2) | 288 | (56.6) | 76 | (21.0) | 4 | (1.4) | |

| Diabetes | 871 | (4.6) | 727 | (4.2) | 24 | (5.4) | 66 | (13.0) | 51 | (14.1) | 3 | (1.0) | |

| Tuberculosis | 52 | (0.3) | 41 | (0.2) | - | (0.0) | 2 | (0.4) | 9 | (2.5) | - | (0.0) | |

| HIV | 327 | (1.7) | 260 | (1.5) | 7 | (1.6) | 7 | (1.4) | 50 | (13.8) | 3 | (1.0) | |

| Stroke | 210 | (1.1) | 147 | (0.9) | 9 | (2.0) | 39 | (7.7) | 15 | (4.1) | - | (0.0) | |

| Cardiac diseases | 174 | (0.9) | 134 | (0.8) | 16 | (3.6) | 17 | (3.3) | 7 | (1.9) | - | (0.0) | |

| Mental Status | |||||||||||||

| A | 16,225 | (86.0) | 14,999 | (86.9) | 424 | (94.6) | 358 | (70.3) | 249 | (68.8) | 195 | (66.4) | |

| V | 546 | (2.9) | 455 | (2.6) | 4 | (0.9) | 36 | (7.1) | 30 | (8.3) | 21 | (7.1) | |

| P | 377 | (2.0) | 295 | (1.7) | 4 | (0.9) | 35 | (6.9) | 22 | (6.1) | 21 | (7.1) | |

| U | 883 | (4.7) | 724 | (4.2) | 2 | (0.5) | 60 | (11.8) | 47 | (13.0) | 50 | (17.0) | |

| Unknown | 844 | (4.4) | 789 | (4.6) | 14 | (3.1) | 20 | (3.9) | 14 | (3.8) | 7 | (2.4) | |

| CTAS | |||||||||||||

| Level 1 | 999 | (5.3) | 815 | (4.7) | 6 | (1.3) | 41 | (8.1) | 72 | (19.9) | 65 | (22.1) | |

| Level 2 | 5,839 | (30.9) | 4,894 | (28.4) | 206 | (46.0) | 374 | (73.5) | 180 | (49.7) | 185 | (62.9) | |

| Level 3 | 7,593 | (40.2) | 7,244 | (42.0) | 158 | (35.3) | 79 | (15.5) | 87 | (24.0) | 25 | (8.5) | |

| Level 4 | 3,108 | (16.5) | 3,051 | (17.7) | 48 | (10.7) | 1 | (0.2) | 5 | (1.4) | 3 | (1.0) | |

| Level 5 | 362 | (1.9) | 353 | (2.0) | 3 | (0.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 6 | (2.0) | |

| Unknown/missing | 974 | (5.2) | 905 | (5.2) | 27 | (6.0) | 14 | (2.8) | 18 | (5.0) | 10 | (3.4) | |

| Chest Pain | |||||||||||||

| ST elevation status YES | - | - | - | - | 29 | (6.5) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Reperfusion therapy YES | - | - | - | - | 10 | (2.2) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Presumed ACS/CAD YES | - | - | - | - | 112 | (25.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Stroke | |||||||||||||

| CT Check status YES | - | - | - | - | - | - | 297 | (58.3) | |||||

| Hemorrhagic status YES | - | - | - | - | - | - | 237 | (46.6) | - | - | - | - | |

| Reperfusion therapy YES | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | (1.4) | - | - | - | - | |

| Sepsis/Septic Shock | |||||||||||||

| Laboratory results present | |||||||||||||

| WBC | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 248 | (68.5) | - | - | |

| Neutrophil | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 123 | (34.0) | - | - | |

| Platelet | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 236 | (65.2) | - | - | |

| Total bilirubin | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | (1.1) | - | - | |

| Creatinine | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 205 | (56.6) | - | - | |

| CRP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 153 | (42.3) | - | - | |

| INR | 40 | (11.0) | |||||||||||

| Source of infection | |||||||||||||

| Pulmonary infection | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 107 | (29.6) | - | - | |

| Gastrointestinal infection | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 65 | (18.0) | - | - | |

| Urinary tract infection | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | (5.5) | - | - | |

| CNS infection | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32 | (8.8) | - | - | |

| Skin infection | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 27 | (7.5) | - | - | |

| Other/unknown/missing | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 111 | (30.6) | - | - | |

| Multiple Trauma | |||||||||||||

| Intentional | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25 | (8.5) | ||

| Mechanism | |||||||||||||

| Motor vehicle accident | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 214 | (72.8) | ||

| Blunt | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 17 | (5.8) | ||

| Fall/slip down | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 14 | (4.8) | ||

| Penetration | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | (3.4) | ||

| Burn | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (0.0) | ||

| Intoxication | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | (0.0) | ||

| Other/unknown/missing | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 39 | (13.2) | ||

| Operation | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 1,129 | (6.0) | 996 | (5.8) | - | (0.0) | 20 | (3.9) | 10 | (2.8) | 103 | (35.0) | |

| Result | |||||||||||||

| Normal discharge | 9,090 | (48.2) | 8,700 | (50.4) | 251 | (56.0) | 49 | (9.6) | 66 | (18.2) | 24 | (8.2) | |

| Discharge with continuity of care | 4,967 | (26.3) | 4,513 | (26.1) | 109 | (24.4) | 191 | (37.5) | 74 | (20.5) | 80 | (27.2) | |

| Hopeless discharge | 2 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.0) | - | (0.0) | - | (0.0) | - | (0.0) | - | (0.0) | |

| Transfer to other hospital | 949 | (5.0) | 764 | (4.4) | 13 | (2.9) | 103 | (20.2) | 29 | (8.0) | 40 | (13.6) | |

| Treatment refusal | 389 | (2.1) | 353 | (2.1) | 9 | (2.0) | 5 | (1.0) | 11 | (3.0) | 11 | (3.7) | |

| Death | 980 | (5.2) | 624 | (3.6) | 18 | (4.0) | 102 | (20.1) | 144 | (39.8) | 92 | (31.3) | |

| Other/unknown | 2,498 | (13.2) | 2,306 | (13.4) | 48 | (10.7) | 59 | (11.6) | 38 | (10.5) | 47 | (16.0) | |

Abbreviations: SAMU=service d'aide médicale urgente; SMUR= Service Mobile d'Urgence et de Reanimation HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; A=alert; V=voice; P=pain; U=unresponsive; CTAS=Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale; ACS=acute coronary syndrome; CAD=coronary artery disease; CT=computerized tomography; WBC=white blood cells; CRP=C-reactive protein; INR=international normalized ratio.

Overall, patients presented with chest pain and multiple trauma were more likely to be male (58.7% for chest pain and 73.1% for multiple trauma) but more female patients were presented with stroke (53.6%) and sepsis/septic shock (56.9%). Chest pain was commonly presented in adult patients in their 30s (21.7%) and 40s (19.6%) while the majority of the patients with stroke was older than 60 years of age (58.9%). On the other hand, multiple trauma was most commonly presented in young adults in their 20s (33.3%). The proportions of patients with history of hypertension were 17.2%, 56.6%, 21.0% and 1.4% for patients with chest pain, stroke, sepsis/septic shock, and multiple trauma, respectively.

Over 94.6% of patients with chest pain were presented with “Alert” mental status while 70.3%, 68.8%, and 66.4% of the stroke, sepsis/septic shock, and multiple trauma patients were presented with “Alert” mental status. Multiple trauma patients showed the highest “Unresponsive” mental status (17.0%) among the four critical symptoms/diseases patients.

Among the 448 patients with chest pain, 6.5% of the patients had ST elevation and 2.2% of the patients received reperfusion therapy. Among the 509 patients with stroke, 58.3% of them received CT imaging and 1.4% received reperfusion therapy. Among the 362 patients with sepsis/septic shock, over half of the patients were tested for white blood cell (68.5%), platelet (65.2%), and creatinine (56.6%). Main source of the infection was pulmonary infection (29.6%) followed by gastrointestinal infection (18.0%). Among the 294 multiple trauma patients, majority of them were from MVA (72.8%). Patients with stroke, sepsis/septic shock, and multiple trauma showed high mortality rates of 20.1%, 39.8%, and 31.3%, respectively.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study on the aggregated patient database in Cameroon. Medical databases serve a critical function in assessing the quality of healthcare for a specific disease or within a specific healthcare delivery [11]. Healthcare data also provides a quantitative basis for the resource allocations, therefore, it is particularly essential to ensure the efficient management and delivery of health services in resource poor environments [12]. The World Health Organization (WHO)’s report, Management of patient information trends and challenges in member state, also emphasizes the importance of patient data and health information in improving the quality of healthcare services [13].

From March 2017 to July 2018, we aggregated patient database from four difference sources and examined the characteristics of patients who visited CURY from January 2016 to June 2018. Since its inception, CURY collected patient databases through its hospital information system, patient medical records, deceased patient records, and transferred patient records. The CURY hospital information system was implemented by the MoPH in Cameroon, and being tested in 5 hospitals with CURY being one of them. However, the system is not being utilized well at CURY and paper-format patient charts are used instead. Most hospitals in Cameroon do not keep patient charts at their hospitals, because patients bring their own patient charts home when they are discharged from the hospital. Although not organized and aggregated, it is one of the CURY's characteristics that the patients’ medical records are being collected and stored in paper-format.

Using the aggregated patient database, we observed several characteristics of the patients who visited CURY. First, only 0.3% of the total patients had insurance. According to the Global Health Expenditure Database in 2018 published by WHO [6], contribution of voluntary health insurance in Cameroon was only 6.8% of the health expenditure in the country whereas out-of-pocket spending was 75.6%. The lower proportion of the number of the patients who were covered by insurance in CURY than that of the expenditure contributed by insurance in the country might be explained by two reasons. First, the health expenditure per person is generally much higher in the patients who are covered by insurance than that in those who are not covered. Second, the uncovered emergency patients who cannot use other health facilities were still able to visit CURY. Most public hospitals in Cameroon ask patients to pay in advance before they provide services even at the emergency situations. To overcome this financial barrier faced by emergency patients, CURY developed its own triage-based post-payment system which enabled those with CTAS level I and level II to receive life-saving care immediately.

Another important finding was the significant increase in the comorbidities, from 2016 to 2018, particularly the non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and cardiac diseases. Our findings are in line with the current experiencing of a rapid increase in the burden of chronic non-communicable diseases in Cameroon [14]. We also observed about 40% of the total patients were trauma patients. Trauma is thought to be a leading cause of global death and disability, and more than 90% of these deaths are occurring in LMIC [15,16]. Our finding also supports trauma being a significant problem in Yaoundé.

In the process of aggregating the patient database, we particularly focused on the four critical symptoms/diseases of chest pain, stroke, sepsis/septic shock, and multiple trauma. Particularly, stroke is the second leading cause of death and disability worldwide and although its incidence is decreasing in developed countries, it is increasing in LMIC, especially African countries [17]. For the treatment of stroke patients, reperfusion therapy using systemic thrombolysis or endovascular mechanical thrombectomy are the proved treatment [18]. Our study shows that while over 58% of the stroke patients received brain CT scan for the diagnosis, only 1.4% of the stroke patients received reperfusion therapy. These findings suggest that while CURY has a functional CT scan that is offered to majority of the stroke patients, they may have shortage of skilled manpower who are specialized in reperfusion therapy skills. A recent systematic review on stroke care services in Africa [19] reported that only 3 African countries (South Africa, Egypt, and Morocco) reported experiences on thrombolysis in acute stroke care. The authors also suggested that the major challenge identified was the cost of stroke treatment, and with the low health insurance coverage across African countries, a significant amount of the high cost of thrombolysis will be paid by patients, which is a major problem given the low per capita income of most African countries. In addition, there is an issue on procurement practices on certain medicines, including the thrombolytic agent, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-TPA). Due to its high cost and infrequent usage, many hospitals in Cameroon, including CURY, do not procure these medicines, which is another barrier for patients with this critical condition from receiving appropriate treatments in time.

In our patient data, the major mechanism of multiple trauma was MVA. Road traffic injuries as the most frequent mechanism of injury in African countries [20], [21], as well as in Cameroon [22], have been previously reported. The majority of multiple trauma patients were males and young adults in their 20s and 30s. Unlike other critical diseases, multiple trauma patients were more likely to be admitted to CURY during nighttime with highest “Unresponsive” mental status than other critical disease patients. Moreover, the fatality rate of the multiple trauma patients in our study was 31.3%, which was second highest among four critical symptoms/diseases. Our findings suggest significant burden of trauma in Yaoundé, Cameroon, particularly due to road traffic accidents.

There are several limitations in this study. First, although we tried to collect data from all the patients who visited CURY during the study period, there were still missing patient medical records. The paper-format medical records were stored at a medical record storage room. However, they were disorganized and some patient charts were even missing or parts of the charts were torn away. Due to these missing medical records, we were not able to collect 100% of the total patients who visited CURY during the study period, but 90.1% for 2016, 99.1% for 2017, and 98.0% of the total patients for 2018 (January to June). Second, even if there were patient medical records available, many variables were missing or unknown. In order to extract most the available information, we used four different data sources and linked them tougher. Lastly, all the patient data were one-time visit data without any follow-up data.

Conclusion

This study serves to broaden understanding of the emergency patients in Yaoundé, Cameroon. The hospital patient database for emergency patients can be further used as a basis for providing improved quality of medical care and effective communication tool among the medical staffs.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) under the title of “Follow Up Management of Centre des Urgences de Yaoundé (CURY) in Cameroon” in 2016 (No. P2016-00110). We would like to acknowledge Donald Paulin Tchapmi Njeunje for his hard work and support in the data collection process.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). There was no additional external funding received for this study.

Dissemination of results

Findings of this study can be used as a basis for providing improved quality of medical care and effective communication tool among the medical staffs, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Moreover, we believe that the results of this study should be a great value to hospital managers, administrators, and health policy makers.

Authors’ contribution

Authors contributed as follow to the conception or design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: JJ and YJK contributed 15% each; SYJK and SSD 10% each, YSR, DHW, SCK, KMS, SK (Suhee), SK (Sola), SBK, LJB, BH, and LW 5% each. All authors approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Odekunle F.F., Odekunle R.O., Shankar S. Why sub-Saharan Africa lags in electronic health record adoption and possible strategies to increase its adoption in this region. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2017;11(4):59–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams F., Boren S.A. The role of the electronic medical record (EMR) in care delivery development in developing countries: a systematic review. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16(2):139–145. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v16i2.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nieves E. Jones. J E.p.i. Info: Now an Open-source application that continues a long and productive "life" through CDC support and funding. Pan Afr Med J. 2009;2:6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Statistics 2021. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021.

- 5.World Bank Open Data-Cameroon 2019 [Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/country/cameroon.

- 6.World Health Organization Global Health Expenditure Database. 2018.

- 7.Bonny A., Tibazarwa K., Mbouh S., Wa J., Fonga R., Saka C. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death in Cameroon: the first population-based cohort survey in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(4):1230–1238. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kacker S., Bishai D., Mballa G.A., Monono M.E., Schneider E.B., Ngamby M.K. Socioeconomic correlates of trauma: An analysis of emergency ward patients in Yaounde. Cameroon. Injury. 2016;47(3):658–664. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su Y., Yoon S.S. Epi info - present and future. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epi Info™, 2020, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html.

- 11.Martin G.S. The essential nature of healthcare databases in critical care medicine. Crit Care. 2008;12(5):176. doi: 10.1186/cc6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bram J.T., Warwick-Clark B., Obeysekare E., Mehta K. Utilization and Monetization of Healthcare Data in Developing Countries. Big Data. 2015;3(2):59–66. doi: 10.1089/big.2014.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Management of patient information: Trends and challenges in Member States. 2012.

- 14.Echouffo-Tcheugui J.B., Kengne A.P. Chronic non-communicable diseases in Cameroon - burden, determinants and current policies. Global Health. 2011;7:44. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juillard C., Kouo Ngamby M., Ekeke Monono M., Etoundi Mballa G.A., Dicker R.A., Stevens K.A. Exploring data sources for road traffic injury in Cameroon: Collection and completeness of police records, newspaper reports, and a hospital trauma registry. Surgery. 2017;162(6S) doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.01.025. S24-S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organizaton. Injuries and violence: the facts. Department of Violence and Injury Prevention and Disability. 2010.

- 17.Urimubenshi G., Cadilhac D.A., Kagwiza J.N., Wu O., Langhorne P. Stroke care in Africa: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Stroke. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1747493018772747. 1747493018772747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhaskar S., Stanwell P., Cordato D., Attia J., Levi C. Reperfusion therapy in acute ischemic stroke: dawn of a new era? BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-1007-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akinyemi R.O., Adeniji O.A. Stroke care services in Africa: a systematic review. J Stroke Med. 2018;1(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solagberu B.A., Adekanye A.O., Ofoegbu C.P., Udoffa U.S., Abdur-Rahman L.O., Taiwo J.O. Epidemiology of trauma deaths. West Afr J Med. 2003;22(2):177–181. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i2.27944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobusingye O.C., Guwatudde D., Owor G., Lett R.R. Citywide trauma experience in Kampala, Uganda: a call for intervention. Inj Prev. 2002;8(2):133–136. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juillard C., Etoundi Mballa G.A., Bilounga Ndongo C., Stevens K.A., Hyder A.A. Patterns of injury and violence in Yaounde Cameroon: an analysis of hospital data. World J Surg. 2011;35(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]