Abstract

Introduction:

Uterine-serous-carcinoma (USC) is an aggressive variant of endometrial cancer. Based on preliminary results of a multicenter, randomized phase II trial, trastuzumab (T), a humanized-monoclonal-antibody targeting Her2/Neu, in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel (C/P), is recognized as an alternative in treating advanced/recurrent HER2/Neu-positive USC. We report the updated survival analysis of NCT01367002.

Methods:

Eligible patients had stage III-IV or recurrent-disease. Participants were randomized 1:1 to receive C/P for 6 cycles ± T followed by maintenance T until progression or toxicity. PFS was the primary-endpoint; OS and toxicity were secondary-endpoints.

Results:

61 patients were randomized. After a median-follow-up of 25.9-months, 43 progressions and 38 deaths occurred among 58 evaluable patients. Updated median-PFS continued to favor the T-arm, with medians of 8.0 versus 12.9-months in the control and T-arms, (HR 0.46, 90%CI 0.28–0.76; P=0.005). Median-PFS was 9.3 versus 17.7-months among 41 patients with stage III-IV disease undergoing primary treatment (HR 0.44, 90%CI 0.23–0.83; P=0.015), and 7.0 versus 9.2-months among 17 patients with recurrent disease (HR 0.12, 90%CI 0.03–0.48; P=0.004). OS was higher in the T compared to the control arm, with medians of 29.6 versus 24.4-months, (HR 0.58; 90%CI 0.34–0.99; P=0.046). The benefit was most notable in those with stage III-IV disease, with survival median not reached in the T-arm versus 24.4-months in the control arm (HR 0.49, 90%CI 0.25–0.97; P=0.041). Toxicity was not different between arms.

Conclusions:

Addition of T to C/P increased PFS and OS in women with advanced/recurrent HER2/Neu-positive USC, with the greatest benefit seen for the treatment of stage III-IV disease.

INTRODUCTION

This year, an estimated 61,880 women in the United States will be diagnosed with uterine cancer, and 12,160 women will die of the disease.1,2 While the global incidence and mortality from most solid tumors have declined or plateaued in the last three decades, endometrial cancer remains one of the only malignancies for which both the incidence and mortality are on the rise1–3. Uterine serous carcinoma is an aggressive, high grade endometrial cancer subtype associated with poor clinical outcomes and significant mortality4,5,6,7,8, 9,10,11,12 Although considered a rare tumor representing only 10% of all uterine cancer deaths, uterine serous carcinoma accounts for a disproportionate 40% of deaths from endometrial cancer, with an overall 5-year survival rate of 45%, compared to 91% for those with endometrioid adenocarcinoma.13

Uterine serous carcinoma is typically treated with hysterectomy and surgical staging followed by platinum/taxane combination chemotherapy.14,15,16,17 Initial response rates to the most commonly used chemotherapy regimen (i.e., carboplatin and paclitaxel) may be as low as 20–60%, which is no better than the response rate of 10–50% among those with recurrent disease.18 The risk of recurrence is high,19,20 and progression-free and overall survival are considerably worse relative to other endometrial histologies.21,22 Therefore, there is a unmet clinical need to identify better therapies for women with this endometrial cancer subtype.

Approximately 30% of uterine serous carcinoma overexpress Her2/Neu,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 a receptor tyrosine kinase critical to cancer signaling, growth, survival, and proliferation, and the target of the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab. HER2 overexpression and amplification appears to be a poor prognostic factor for uterine serous carcinoma, similar to breast cancer. In 2018, we reported the preliminary results of a randomized phase II trial that showed improvement in progression-free survival by nearly 5 months in patients with advanced and recurrent Her2/Neu-positive uterine serous carcinoma who received trastuzumab in addition to carboplatin/paclitaxel when compared with carboplatin/paclitaxel alone.32 Overall survival data were not yet mature at the time of publication of that report, but in a preliminary sensitivity analysis for stage IIIC or IV disease, a 66% mortality reduction in the trastuzumab arm was observed (hazard ratio 0.34; 90% CI, 0.14 to 0.86; P=0.023). Subsequently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Uterine Neoplasm Guidelines endorsed the addition of trastuzumab to standard cytotoxic chemotherapy as the preferred regimen for the treatment of Her2/Neu-positive, advanced or recurrent uterine serous carcinoma.33 Herein, we report the mature overall survival data for this trial.

METHODS

Study design and conduct.

The patient eligibility criteria and study design for this investigator-initiated randomized phase II study (NCT01367002) were as previously described.32 The study was approved by the Yale institutional review board (HIC) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and informed written consent was obtained from each subject. Briefly, across 11 participating academic institutions within the United States, patients were randomized 1:1 by the lead study institution using minimization33 to balance the treatment arms for study site, disease status (advanced versus recurrent uterine serous carcinoma), and residual tumor after debulking within the advanced-disease group. Patients were scheduled to receive intravenous carboplatin area under the curve (AUC) 5 and paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 over 3 hours every 21 days with or without trastuzumab at 8mg/kg for the first dose and 6 mg/kg in subsequent cycles until disease progression or prohibitive toxicity (Figure 1). The trial was designed to accrue 100 participants at a rate of five per month for 20 months. Interim analysis for futility was scheduled on observing 26 recurrences, progressions, or deaths and final analysis on observing 85 events. Power calculations assumed that median progression-free survival (PFS) would be 6 months on the carboplatin-paclitaxel arm and 10.5 months on the carboplatin-paclitaxel-trastuzumab arm, equivalent to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.57 with trastuzumab addition. For the final efficacy analysis, we planned to compare the carboplatin-paclitaxel-trastuzumab arm to the carboplatin-paclitaxel arm for the expected increase in PFS by means of the log-rank test, conducted using a one-sided a of 0.10. Under this plan, 85 recurrence/progression/death events gave the study 90% power to detect HR of 0.57 with carboplatin-paclitaxel-trastuzumab versus carboplatin- paclitaxel. Power was adjusted for the interim futility analysis using the O’Brien-Fleming spending function to allocate type II error. We expected to observe the 26th recurrence/progression/death event at 12.9 months and the 85th recurrence/progression/death event at 33.6 months. The first subject was enrolled in August of 2011, after which (1) the accrual rate was slower than planned, and (2) observed progression-free survival exceeded original expectations. The study was closed to further accrual in March of 2017 with a total of 61 enrolled subjects. Efficacy analysis commenced in August of 2017. The current updated analysis was performed at the time of 43 progressions and 38 deaths.

Figure 1:

CONSORT diagram.

Eligibility.

All patients were 18 years of age or older and had FIGO 2009 stage III-IV34 or recurrent (any previous stage) Her2/Neu-positive uterine serous carcinoma as defined by an immunohistochemistry score of 3+ or 2+ with gene amplification confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Her2/Neu-positive status was determined using paraffin-embedded tumor tissue from either primary surgery or from recurrent disease. Scoring was performed according to guidelines set forth by the 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists for breast cancer.34 Specimens were centrally reviewed for Her2/Neu+ and confirmed to contain ≥10% uterine serous carcinoma by two gynecologic pathologists. Patients may have been either optimally or suboptimally debulked after primary surgery. Patients were enrolled within 8 weeks after surgery or diagnosis of recurrent disease. Patients were required to exhibit an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group35 performance status of 0 to 2, adequate bone marrow, renal function, and hepatic function. All patients diagnosed with recurrence were required to have measurable disease, defined as at least one target lesion per RECIST v1.1.36 A treatment-free interval of >6 months from last carboplatin/paclitaxel treatment was required in those with recurrent disease. Patients with recurrent disease may not have received >3 prior chemotherapies for treatment of their uterine cancer. The schemata for treatment modification are provided in the full protocol (Figure S1).

Endpoints.

The primary endpoint in this study was progression-free survival, defined as the length of time from randomization to disease recurrence, disease progression, or death for any reason, whichever occurred first. This primary endpoint drove our previously published sample-size considerations.32 Secondary endpoints included objective response, overall survival, and safety of trastuzumab in study subjects. Response was defined by RECIST 1.1.36 Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0 were used to describe adverse events.37

Statistical analyses.

The statistical design of this trial was described previously.32 Briefly, patient characteristics, objective response rate, and occurrence of adverse events were examined for differences between treatment arms using two-sided Fisher’s exact and Wilcoxon rank sum tests at a = 0.05. PFS and OS, both overall and stratified by disease status, were determined using Kaplan-Meier analysis. One-sided log-rank tests were used to compare survival functions and improvement with trastuzumab. For the primary efficacy analysis, the log rank test used a one-sided a = 0.10 significance level, as originally specified in the study’s protocol. All other log rank tests used one-sided a = 0.05 significance levels. Every assessment was accompanied by a Cox regression HR with two-sided 90% CI.

RESULTS

Patients.

As previously published,32 between August 2011 and January 2017, sixty-one subjects were enrolled (Figure 1). Three participants were excluded due to withdrawal of consent (n=1) or failure to confirm Her2/Neu positivity by FISH following 2+ immunohistochemistry (n=2) at the time of central review, leaving 58 subjects (28 in the carboplatin/paclitaxel arm and 30 in the carboplatin/paclitaxel/trastuzumab arm) evaluable for response to treatment. Forty-one subjects (71%) had primary, advanced disease; 17 subjects (29%) had recurrent disease. Of the subjects with advanced disease, 22 (54%) received primary radiation, and only 5 (11.6%) had gross residual disease following debulking surgery. Of the subjects with recurrent disease, the median number of prior lines of chemotherapy was 1 (range 0–2). The treatment arms did not differ significantly for race, ethnicity, study site, or disease status (advanced versus recurrent disease), radiation or optimal debulking among advanced-disease subjects, or number of prior lines of chemotherapy among recurrent-disease subjects; however, subjects in the trastuzumab arm were younger (median 66 years; interquartile range of 64–69 years) compared to the control arm (median 73 years; interquartile range of 68–78 years) (P=0.006).

Treatment.

The 28 subjects in the control arm completed a total of 156 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel (range 1–8). The 30 subjects in the trastuzumab arm completed 178 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel (range 4–9). At the time of analysis, subjects in the trastuzumab arm had received a total of 654 cycles of trastuzumab (median: 16 cycles; range: 5–86 cycles). In all, 23 subjects (82%) on the control arm completed 6 or more cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel. On the trastuzumab arm, 26 subjects (87%) completed 6 or more paclitaxel cycles while 28 subjects (93%) completed 6 or more carboplatin cycles. To date, 6 patients (20%) on the trastuzumab arm remain on the drug without evidence of disease progression. These patients all had primary, advanced-stage disease.

Primary endpoint: updated progression-free survival.

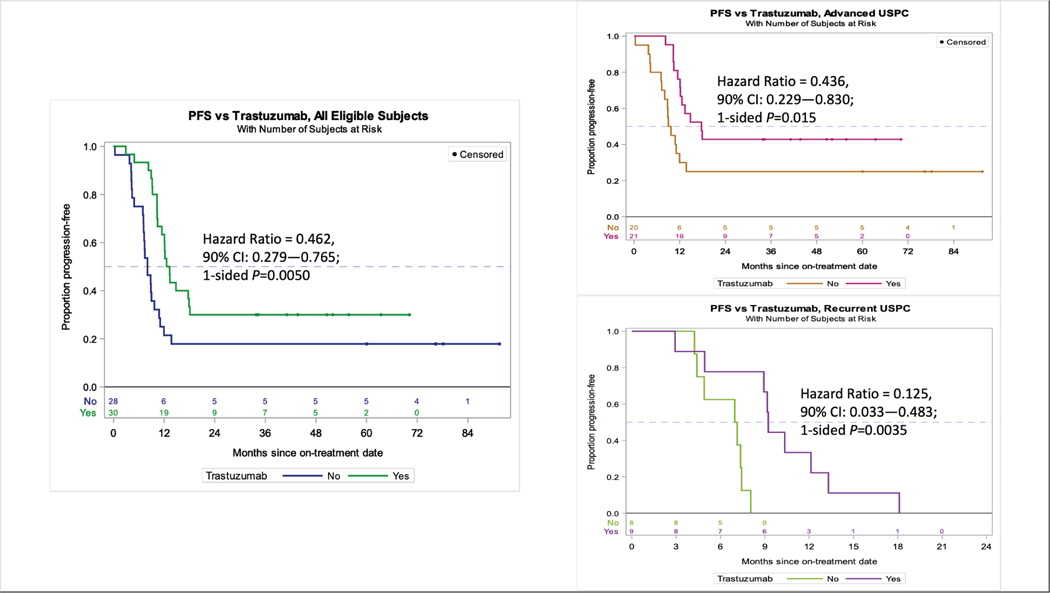

At the time of this updated analysis, the 58 response-evaluable subjects experienced 44 events (43 progressions and 38 deaths) during a total follow-up of 1,865 months (median: 25.9 months; range: 0.33–91.5 months). Among all patients, the updated analysis continued to favor the trastuzumab arm, with median progression-free survival of 8.0 months in patients who received carboplatin/paclitaxel alone and 12.9 months in patients who received chemotherapy plus trastuzumab (hazard ratio 0.46, 90% CI 0.28–0.76; P=0.005,) (Figure 2-left). After subgrouping subjects by disease status (i.e., advanced or recurrent), median progression-free survival was 9.3 in the control arm versus 17.7 months in the trastuzumab arm among 41 stage III-IV patients undergoing primary treatment (hazard ratio 0.44, 90%CI 0.23–0.83, P=0.015) (Figure 2-right top), and 7.0 versus 9.2 months among 17 patients with recurrent disease (hazard ratio 0.12, 90%CI 0.03–0.48; P=0.004) (Figure 2-right, bottom).

Figure 2.

Updated progression-free survival analyses continue to support the addition of trastuzumab to the treatment of advanced/recurrent uterine serous carcinoma (USC). Left: Median PFS was 8.0 months in patients who received CP and 12.9 months in patients who received CP+T (HR 0.46, 90% CI 0.28–0.76, p=0.005). Benefit from the addition of trastuzumab was greatest in those undergoing primary treatment. Right, top: Median PFS was 9.3 (CP) versus 17.7 (CP+T) months among 41 stage III-IV pts undergoing primary treatment (HR 0.44, 90%CI 0.23–0.83, p=0.015). Right, bottom: Median PFS 7.0 (CP) versus 9.2 (CP+T) months among 17 patients with recurrent disease (HR 0.12, 90%CI 0.03–0.48, p=0.004)

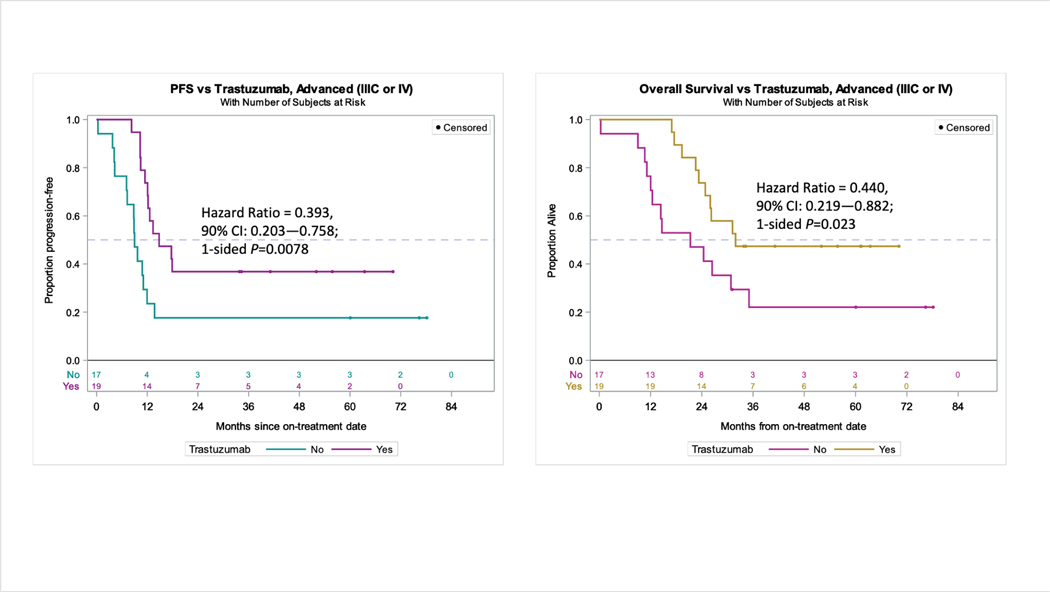

In a subset analysis of those undergoing primary treatment (Figure 3-left) restricted to patients with the highest risk for distant failure and worst outcomes (stage IIIC or stage IV), the addition of trastuzumab (n=17) continued to provide progression-free survival benefit over control (n=19) (9.0 versus 14.8 months, hazard ratio 0.40, 90% CI 0.203─0.758, P=0.008).

Figure 3.

In a subset analysis of patients restricted to stage IIIC/IV disease, the addition of trastuzumab (n=17) continued to provide both (left) progression-free survival benefit over control (n=19) (9.0 versus 14.8 months, HR 0.393, 90% CI 0.203–0.758, p=0.0078) and (right) overall survival benefit over control (21.1 versus 31.9 months, HR 0.440 90% CI 0.219–0.882 p=0.0230).

A total of 15 subjects did not experience disease progression. Five were randomized to the control arm, 9 were randomized to the experimental arm. After disease progression, nine (30%) of the 30 subjects randomized to the carboplatin/paclitaxel-alone arm ultimately received a trastuzumab-containing therapy off-trial.

Secondary endpoints: overall survival.

Among all patients, overall survival was significantly higher in the trastuzumab arm compared to the control arm, with medians of 29.6 versus 24.4 months, respectively (hazard ratio 0.58, 90%CI 0.34–0.99; P=0.046, Figure 4-left). This benefit was particularly striking in the stage III-IV patients (Figure 4-right, top), in whom median overall survival was not reached in the trastuzumab arm versus 25.4 months in the control arm (hazard ratio 0.49, 90%CI 0.25–0.97; p=0.041). Improvement in overall survival was also notable in the subset analysis of stage IIIC/IV patients undergoing primary therapy (21.3 versus 31.9 months, hazard ratio 0.44, 90% CI 0.22–0.88, P=0.023) (Figure 3-right). No significant overall survival benefit from trastuzumab was observed in those with recurrent disease (Figure 4-right, bottom). Of the 38 deaths thus far, 37 were preceded by disease progression while one death was from thromboembolic events.

Figure 4.

Addition of trastuzumab improves overall survival in advanced uterine serous carcinoma (USC). Left: Among all patients, OS was 24.4 (CP) versus 29.6 (CP+T) months (HR 0.581, 90% CI 0.339–0.994, p=0.0462). Right-top: Benefit was greatest in those undergoing primary therapy with advanced disease (OS 25.4 months versus not reached, HR 0.492, 90% CI 0.249 – 0.974, p=0.0406). Right-bottom: Benefit was not apparent in the recurrent setting (22.5 versus 25.0 months, HR 0.864, 90% CI 0.355–2.100, p=0.3929).

Secondary endpoints: safety.

Trastuzumab was given over a median of 11.3 months (range: 3.45–62.1). No patient required discontinuation of trastuzumab for toxicity, though there were several instances of dose delays due to patient scheduling conflicts or transportation barriers. Sixty patients were evaluable for toxicity; 57 of them had a CTCAE event. At the time of the preliminary analysis, there were no differences in toxicity between the control and experimental treatment arms (p=0.49, Wilcoxon rank-sum for maximum toxicity per patient). Since the original report, there were 42 additional adverse events reported, which included 5 before treatment was assigned (all grade 1); 10 during treatment with chemotherapy and trastuzumab, including grade 3 pruritus (n=1) and grade 3 neutropenia (n=1); one at the end of treatment with chemotherapy alone (alopecia of unknown grade); 13 during post-chemotherapy treatment with trastuzumab alone, including grade 3 leukopenia (n=1); 13 during quarterly surveillance after chemotherapy alone (including grade 3 abdominal pain and grade 3 nausea, both in the same patient). Only one new adverse event (grade 3 pruritus) was classified as serious. There were 12 new adverse events (all belonging to the same subject), 4 of which resulted in hospitalization including grade 1 bowel obstruction, grade 1 abdominal distension, and grade 3 nausea and abdominal pain described above.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective, randomized phase II trial update of women with stage III-IV or recurrent, HER2/neu-positive uterine serous carcinoma, the addition of trastuzumab to carboplatin/paclitaxel resulted in significantly improved progression-free and overall survival, with the greatest benefit in both survival categories observed in women with stage III/IV disease undergoing primary therapy after surgery. Updated median progression-free survival continued to favor the trastuzumab arm by approximately 5 months in the entire cohort, with a >8-month improvement for women with stage III-IV disease undergoing primary treatment. Overall survival was also significantly higher in the trastuzumab arm by 5 months, with a particular benefit again noted in those with stage III-IV disease treated upfront (median overall survival not reached in the trastuzumab arm versus 25.4 months in the control arm). The addition of trastuzumab was well tolerated by patients, with few high-grade adverse events. In fact, 20% of patients on the trastuzumab arm remain on the drug without evidence of disease recurrence. This is the first randomized treatment trial powered to study survival outcomes for this rare endometrial cancer subtype.

Notably, approximately 30% of patients who experienced disease recurrence or progression on the carboplatin/paclitaxel only arm ultimately received trastuzumab therapy off clinical trial, which could have potentially blunted the overall survival benefit of trastuzumab. While progression-free survival was selected as the primary study endpoint precisely because therapies administered downstream of the trial treatments may impact overall survival outcomes, a significant overall survival benefit was still observed to favor the trastuzumab arm.

In this work, we have demonstrated that Her2/Neu overexpression in women with advanced or recurrent uterine serous carcinoma, defined as 3+ by immunohistochemistry or 2+ with confirmatory fluorescent in situ hybridization testing, reliably identifies a target population for whom clinical benefit can be achieved with trastuzumab. Approved algorithms exist for scoring HER2 expression and amplification in breast and gastrointestinal carcinomas. At the time of study conception, no standardized criteria existed for gynecologic cancers, including uterine serous carcinoma. Typically, the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) breast cancer algorithms are employed. This algorithm has undergone two recent modifications, most recently in 2018. Given that HER2/neu expression or amplification based on the 2007 algorithm appeared to be a biomarker for trastuzumab response, we maintained the use of the 2007 ASCO/CAP HER2/neu scheme throughout the trial duration. Efforts to validate the 2018 testing criteria in this setting are underway.

Recent studies suggest improved activity in several cancer subtypes when trastuzumab and chemotherapy are combined with another humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody, pertuzumab. In 2017, the FDA granted pertuzumab approval for use in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy as an adjuvant treatment for patients with HER2-positive, early-stage breast cancer at high risk of recurrence based on the double-blind, phase III APHINITY trial. Additionally, in vitro studies by our research group demonstrated that pertuzumab plus trastuzumab induce strong antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity in HER2/neu amplified uterine serous carcinoma cell lines.39 Given these promising findings a U.S. cooperative group study is planned to determine the efficacy of carboplatin/paclitaxel/trastuzumab with or without pertuzumab in women with advanced, HER2/neu-positive disease.

Strengths of the current study include the randomized trial design, rigorous HER2/neu testing, central pathology review, and the relatively large number of U.S. centers included. Study limitations include the small number of patients enrolled, that the control arm has significantly older patients and this may have impacted overall survival outcomes, that we enrolled a somewhat heterogeneic cohort of patients with advanced/primary and recurrent disease, and premature trial closure was performed due to slow patient accrual. Despite this, the trial findings illustrate the ability to perform clinically meaningful studies in women with uncommon endometrial cancer histologies using an innovative trial design and a coordinated multi-institutional approach. Finally, trastuzumab is an expensive treatment associated with a high drug acquisition cost. However, studies demonstrate that this drug appears to be a reasonably cost effective treatment option for breast cancer patients, especially as primary/adjuvant treatment in contrast to treatment in the palliative disease setting.38 A study is planned to evaluate the cost effectiveness of trastuzumab in women with primary, advanced HER2 positive uterine serous carcinoma.

The identification of novel and improved treatment strategies for uterine serous carcinoma is imperative. The addition of trastuzumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in this randomized phase II study may represent a new standard treatment for uterine serous carcinoma tumors that overexpress HER2/neu, particularly in women with advanced, primary disease. Future studies are needed to determine if the addition of other anti-HER2/neu antibodies or targeted agents to trastuzumab have the potential to augment survival further.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Uterine serous carcinoma (USC) is a rare but highly aggressive variant of endometrial cancer overexpressing Her2/Neu, the target of the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab, in approximately 30% of cases. We report the final results of a randomized multicenter phase II trial of trastuzumab (T) in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel (C/P) compared with carboplatin/paclitaxel (C/P) alone in USC patients overexpressing Her2/Neu. T/C/P treated patients achieved a significantly longer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) when compared to C/P patients. The benefit was most notable in USC patients with stage III-IV disease, with median survival not reached in the T arm versus 24.4 months in the control arm (hazard ratio 0.49, 90%CI 0.25–0.97; P=0.041). Toxicity was not different between treatment arms. Mature OS findings support T/C/P as a new, safe and effective treatment option for USC patients overexpressing HER2/Neu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.215516-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wethington SL, Fader AN. ProMisE on the horizon: molecular classification of endometrial cancer in young women. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(3):465–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lortet-Tieulent J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Jemal A. International Patterns and Trends in Endometrial Cancer Incidence, 1978–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(4):354–361. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hameed K, Morgan DA. Papillary adenocarcinoma of endometrium with psammoma bodies. Histology and fine structure. Cancer. 1972;29(5):1326–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton CA, Cheung MK, Osann K, et al. Uterine papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas predict for poorer survival compared to grade 3 endometrioid corpus cancers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(5):642–646. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slomovitz BM, Burke TW, Eifel PJ, et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC): a single institution review of 129 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91(3):463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podratz KC, Mariani A. Uterine papillary serous carcinomas: the exigency for clinical trials. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91(3):461–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goff BA, Kato D, Schmidt RA, et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: patterns of metastatic spread. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;54(3):264–268. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendrickson M, Ross J, Eifel PJ, Cox RS, Martinez A, Kempson R. Adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: analysis of 256 cases with carcinoma limited to the uterine corpus. Pathology review and analysis of prognostic variables. Gynecol Oncol. 1982;13(3):373–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carcangiu ML, Chambers JT. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: a study on 108 cases with emphasis on the prognostic significance of associated endometrioid carcinoma, absence of invasion, and concomitant ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;47(3):298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grice J, Ek M, Greer B, et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: evaluation of long-term survival in surgically staged patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;69(1):69–73. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.4956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz PE. The management of serous papillary uterine cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2006;18(5):494–499. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000239890.36408.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosary C. Cancer of the Corpus Uterus. Uterus SEER Surviv Monogr Cancer Surviv Adults US SEER Program 1988–2001 1988–2001 NCI SEER Program Natl Cancer Inst Bethesda MD. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boruta DM, Gehrig PA, Fader AN, Olawaiye AB. Management of women with uterine papillary serous cancer: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) review. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115(1):142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fader AN, Drake RD, O’Malley DM, et al. Platinum/taxane-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy favorably impacts survival outcomes in stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115(10):2119–2127. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramondetta L, Burke TW, Levenback C, Bevers M, Bodurka-Bevers D, Gershenson DM. Treatment of uterine papillary serous carcinoma with paclitaxel. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82(1):156–161. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fader AN, Nagel C, Axtell AE, et al. Stage II uterine papillary serous carcinoma: Carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy improves recurrence and survival outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):558–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoskins PJ, Swenerton KD, Pike JA, et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin, alone or with irradiation, in advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;19(20):4048–4053. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.20.4048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sood BM, Jones J, Gupta S, et al. Patterns of failure after the multimodality treatment of uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(1):208–216. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00531-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiess AP, Damast S, Makker V, et al. Five-year outcomes of adjuvant carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy and intravaginal radiation for stage I-II papillary serous endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(2):321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.07.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Homesley HD, Filiaci V, Gibbons SK, et al. A Randomized Phase III Trial in Advanced Endometrial Carcinoma of Surgery and Volume Directed Radiation Followed by Cisplatin and Doxorubicin with or without Paclitaxel: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Boer SM, Powell ME, Mileshkin L, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): patterns of recurrence and post-hoc survival analysis of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(9):1273–1285. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30395-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santin AD, Bellone S, Siegel ER, et al. Racial differences in the overexpression of epidermal growth factor type II receptor (HER2/neu): a major prognostic indicator in uterine serous papillary cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buza N, English DP, Santin AD, Hui P. Toward standard HER2 testing of endometrial serous carcinoma: 4-year experience at a large academic center and recommendations for clinical practice. Mod Pathol. 2013. Dec;26(12):1605–12. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.113. Epub 2013 Jun 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grushko TA, Filiaci VL, Mundt AJ, et al. An exploratory analysis of HER-2 amplification and overexpression in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santin AD, Bellone S, Gokden M, et al. Overexpression of HER-2/neu in uterine serous papillary cancer. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2002;8(5):1271–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalifa MA, Mannel RS, Haraway SD, Walker J, Min KW. Expression of EGFR, HER-2/neu, P53, and PCNA in endometrioid, serous papillary, and clear cell endometrial adenocarcinomas. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;53(1):84–92. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Odicino FE, Bignotti E, Rossi E, et al. HER-2/neu overexpression and amplification in uterine serous papillary carcinoma: comparative analysis of immunohistochemistry, real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(1):14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Díaz-Montes TP, Ji H, Smith Sehdev AE, et al. Clinical significance of Her-2/neu overexpression in uterine serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100(1):139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh P, Smith CL, Cheetham G, Dodd TJ, Davy MLJ. Serous carcinoma of the uterus-determination of HER-2/neu status using immunohistochemistry, chromogenic in situ hybridization, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction techniques: its significance and clinical correlation. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2008;18(6):1344–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buza N, Roque DM, Santin AD HER2/neu in Endometrial Cancer: A Promising Therapeutic Target with Diagnostic Challenges. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014. Mar;138(3):343–50. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0416-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fader AN, Roque DM, Siegel E, et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Carboplatin-Paclitaxel Versus Carboplatin-Paclitaxel-Trastuzumab in Uterine Serous Carcinomas That Overexpress Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2/neu. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2044–2051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-Uterine Neoplasms. Version 4.2019. 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/uterine.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2019.

- 34.Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Hicks DG, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(2):241–256. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0953-SA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) - CTCAE_4.03_2010–06-14_QuickReference_5×7.Pdf. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5×7.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2016.

- 38.Younis T, Skedgel C. Is trastuzumab a cost-effective treatment for breast cancer? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(5):433–442. doi: 10.1586/14737167.8.5.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Sahwi K, Bellone S, Cocco E, et al. In vitro activity of pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab in uterine serous papillary adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(1):134–143. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.