Abstract

Background:

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is a signature wound of Veterans of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan (i.e., OIF/OEF/OND). Most Veterans with mTBI also experience stress-based psychopathology (e.g., depression, posttraumatic stress disorder) and chronic pain. This combination – referred to as polytrauma - results in detrimental long-term effects on social, occupational, and community reintegration. This study will compare the efficacy of a one-day Acceptance and Commitment Training plus Education, Resources, and Support (ACT+ERS) workshop to a one-day active control group (ERS) on symptoms of distress and social, occupational, and community reintegration. We will also examine mediators and moderators of treatment response.

Methods:

This is an ongoing randomized clinical trial. 212 OIF/OEF/OND Veterans with polytrauma are being recruited. Veterans are randomly assigned to a one-day ACT+ERS or a one-day ERS workshop with two individualized booster sessions approximately two- and four-weeks post-workshop. Veterans complete assessments prior to the workshop and again at six weeks, three months, and six months post-workshop. Of note, workshops were converted to a virtual format due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results:

The primary outcomes are symptoms of distress and reintegration; secondary outcomes are post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and pain interference. Secondary analyses will assess whether changes in avoidance at three months mediate changes in distress and reintegration at six months.

Conclusion:

Facilitating the psychological adjustment and reintegration of Veterans with polytrauma is critical. The results of this study will provide important information about the impact of a brief intervention for Veterans with these concerns.

Keywords: Acceptance commitment therapy, Polytrauma, Mild traumatic brain injury, Veterans, Randomized controlled trial, Brief intervention

1. Introduction

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is a “signature wound” of Operations Iraqi Freedom, Enduring Freedom, and New Dawn (OIF/OEF/OND) [1,2]. Among those with an mTBI diagnosis, many also experience stressed based psychopathology (e.g., depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and/or anxiety) and chronic pain [3–6]. Recent data from studies of OIF/OEF/OND Veterans suggest that each of these problems rarely occur by themselves [7–9]. Individually, each of these conditions alone is associated with negative consequences [10,11]. However, the cumulative effect of the “polytrauma” triad of chronic pain, psychological distress, and mTBI is associated with even more profound negative consequences [10,12,13] and can be devastating for Veterans and their families [8,14].

Despite the negative impacts of polytrauma on OIF/OEF/OND Veterans’ mental health and functioning, only 25% of Veterans sampled in a national survey reported obtaining treatment [6]. Even among Veterans who accessed treatment, only a minority completed treatment [17]. Most patients treated within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) with new psychiatric diagnoses receive no, or low-intensity, psychotherapy services [18] and high dropout rates are common [19].

Avoidance, stigma, and practical constraints (e.g., transportation, travel distance, childcare) contribute to the difficulty in Veterans accessing care and completing treatment [20–26]. Avoidant coping often reduces Veterans’ immediate experience of distress from polytrauma symptoms. However, avoidant coping can have detrimental long-term effects [15,16], can make engaging in care difficult [27], and maintains functional limitations associated with polytrauma [9]. In fact, avoidant coping can have significant costs to Veterans’ functioning. Thus, typical treatment models targeting individual diagnoses over several months do not fit for many Veterans [22,27]. Given the cumulative barriers of stigma, practical constraints, and avoidant coping, novel methods of delivering efficacious therapies are needed [28–30].

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) helps patients overcome avoidance by promoting acceptance-based coping and engagement in valued activities [31]. Acceptance is a willingness to experience difficult thoughts/feelings/memories in the pursuit of doing what matters most (values). ACT has been identified by the American Psychological Association as an empirically supported treatment [32] and has shown promise in facilitating adjustment to various chronic health conditions [33]. Meta-analyses have shown that ACT is effective for treating a wide variety of problems [27,32,34–42].

ACT has been implemented in many formats [43], including one-day workshops [44]. A “workshop,” rather than “weekly therapy,” addresses practical barriers [45] and stigma associated with seeking care [20]. For example, presenting the treatment as a “workshop” rather than “therapy” is better suited for Veterans who are not explicitly seeking specialized mental health care. A one-day workshop is also more accessible and feasible than weekly treatments, particularly for Veterans who work, live in rural communities, have other family or work responsibilities, and/or suffer other functional barriers to accessing care. Finally, the workshop also promotes treatment adherence and completion because Veterans receive the entire protocol on the same day [46].

In pilot work, a one-day ACT workshop was tailored to Veterans with polytrauma [47]. Participants were randomly assigned to the one-day ACT workshop (N = 20) or to treatment as usual (TAU; N = 12). The TAU group followed standard care through the VHA system, including continued utilization of VHA psychiatric and medical services [47]. Veterans in the ACT group exhibited greater improvements in distress (effect size = 0.68) and reintegration (effect size =0.47) compared to those assigned to TAU. Additionally, all Veterans who attended the workshop completed it, and over 90% completed three-month follow-up assessments.

The purpose of the current study is to evaluate the efficacy of a one-day ACT with education plus resources and support (ACT+ERS) intervention compared to an active control condition called education plus resources and support (ERS) workshop among Veterans with polytrauma. The primary aim of this study is to examine the efficacy of a one-day ACT+ERS workshop compared to ERS at the six-month follow-up on symptoms of distress and reintegration into civilian life (primary outcomes) and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and pain interference (secondary outcomes). The secondary aim of this study is to evaluate whether changes in avoidance at the three-month follow-up mediate changes in symptoms of distress and reintegration at the six-month follow-up. The exploratory aims of this study are to compare groups on service utilization patterns and medication use and examine moderators (e.g., demographics, illness) of outcomes at the six-month follow-up.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

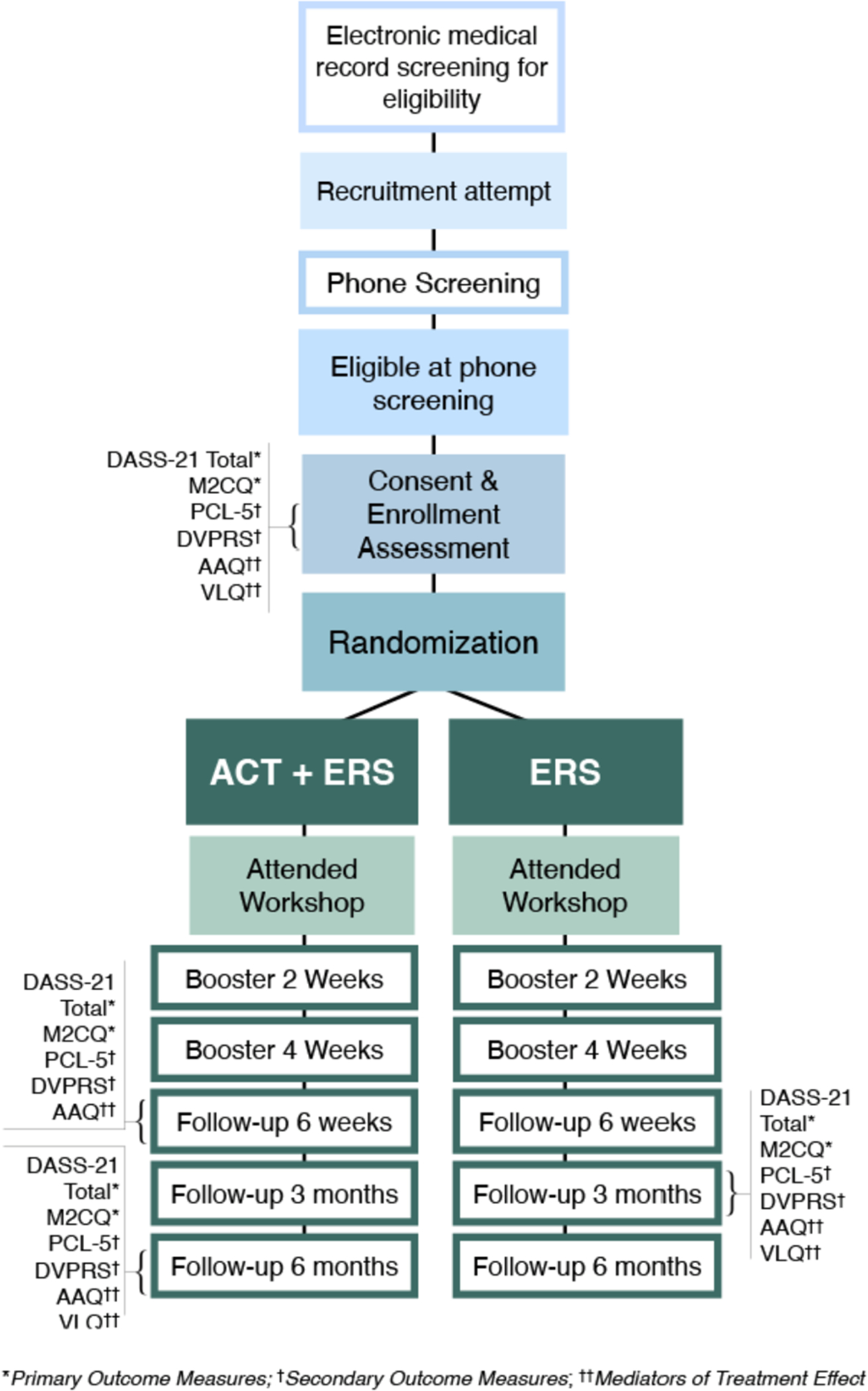

This study is a two-arm, patient- and assessor-blind, parallel randomized controlled trial. Veterans with mTBI, chronic pain, and stress-based psychopathology (i.e., polytrauma), are randomly assigned to one of two group workshops: 1) one-day ACT+ERS workshop or 2) one-day ERS only. At two and four weeks after the workshop, each Veteran receives individualized booster sessions corresponding to the workshop completed. Primary and secondary outcomes are assessed at six weeks, three months and six months following the workshops; six months is the primary outcome point. Study procedures have been designed to be consistent with CONSORT guidelines for reporting randomized controlled trials (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT guidelines for SERVE recruitment, consenting, intervention, and assessments.

2.1.1. Setting and sample

This study is being conducted in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in a large metropolitan city. Over a four-year period, 212 OIF/OEF/OND Veterans with polytrauma will be recruited (see Sample Size Justification for details). Veterans are recruited through a mix of referrals from providers affiliated with the VAMC, ads in associated clinics, Veteran Community Organizations (including their social media), and mailing lists generated from VA electronic medical records.

2.1.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Criteria for pre-consent screening include: 18–64 years old; OIF/OEF/OND related service; endorsement of possible TBI using the Veterans Affairs (VA) 4-question version of the Brief Traumatic Brain Injury Screen [48]; emotional distress (i.e., PHQ-849 or GAD-750 score ≥ 10), and pain (i.e., at least one of: three or higher on one to 10 pain scale; current pain interference is five or more on a one to 10 interference scale; ongoing chronic pain documented in their medical record and verified with the Veteran). Those who pass screening are invited to complete a full baseline assessment, following consent.

Inclusion criteria at the baseline session include: Presence of stress-based psychopathology as operationalized by a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and/or PTSD on the M.I.N·I. International Neuropsychiatric interview, (M.I.N.I [51].)1; presence of at least one OIF/OEF/OND-deployment related mTBI on the Ohio State University TBI Identification method (OSU TBI-ID48); and a pain intensity or interference score ≥ five on the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS [52]) or presence in medical chart of current chronic pain including headache, musculoskeletal pain or neuropathic pain that has been verified with patient. See Table 1 for a list of study measures, their stem and response options, study-relevant inclusion criteria, and psychometric properties.

Table 1.

SERVE screening, final inclusion criteria, primary outcomes, secondary outcomes and exploratory outcome measures.

| Construct | Instrument | General Information | Stem and Response Options | Scoring and Study-Relevant Cutoffs | Psychometric Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Measures | |||||

| Presence and Severity of Depression | Patient Health Questionnaire – Eight (PHQ-8) | The PHQ-8 assesses the presence and severity of depression symptoms based on the DSM criteria. | Participants are asked how often they were bothered by each symptom in the past two weeks. From Not at all (0) to Nearly every day (3) |

Sum score of zero to 24; study participants need at least a 10 to meet screening criteria for further assessment. | Internal reliability good (0.88) [49]. |

| Presence and Severity of Anxiety | Generalized Anxiety Disorder - Seven (GAD-7) [50] | The GAD is a seven-item anxiety scale that screens for anxiety and assesses anxiety severity. It utilizes a rating scale to score questions based on the DSM criteria for GAD [53]. | Participants are asked how often they were bothered by each symptom in the past two weeks. From Not at all (0) to Nearly every day (3) |

Zero-21 score; study participants need at least a 10 to meet screening criteria for further assessment. | Test-retest reliability good (0.83). Sensitivity (0.89). Specificity (0.82) [54]. |

| Identifying TBI Injuries and Symptoms | Veteran Traumatic Brain Injury Screening Tool (VATBIST) | This screening tool identifies Veterans with TBI-related injuries and TBI-related symptoms. | Four questions pertaining to: Exposure to a potential TBI-causing event, loss or alteration of consciousness, postconcussive symptoms at the time of injury, current post concussive symptoms. | If a participant responds positively to at least one element in each of the four questions, the screening is considered positive for a possible TBI. | Reliability adequate (0.77). Test-retest reliability good (0.80). Sensitivity (0.94). Specificity (0.59) [55]. |

| Final Inclusion Criteria | |||||

| Psychopathology | M.I.N.I International Neuro-psychiatric Interview (MINI 7.0) | The M.I.N.I. is used to assess the number and type of major DSM-5 Axis I Psychiatric Disorders [56]. This measure is interviewer administered and a case-consensus is completed. | Includes 12 of 17 total modules for psychiatric diagnoses. Questions are phrased to allow only “yes” or “no” answers. | Veteran must meet criteria for MDD, posttraumatic stress disorder, or GAD. Excluded if positive for Psychosis or Severe substance use. | Specificity (range: 0.72 to 0.97) [51]. |

| History of Traumatic Brain Injury | Traumatic Brain Injury - Ohio State University TBI – Identification Method (OSU TBI-ID) – Modified | OSU TBI-ID is a three- to five-minute structured interview to assess a person’s lifetime history of TBI. This measure is interviewer administered and a case-consensus is completed. | Assesses seven types of head trauma: Hospitalization, motor vehicle, fall, fight, explosion, overdose | Severity of injury ranges from Improbable TBI (1) to Severe TBI (5) Severity must be two or three for inclusion in the study. |

Interrater reliability good (range: 0.85 to 0.90) [48]. |

| Primary Outcomes | |||||

| Stress based symptoms of psychopathology | The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) | 21-item measure assessing current symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress and a total score. | Participants rate the extent to which they have experienced each symptom over the past week on a four-point scale (from 0 = did not apply to me at all to 3 = applied to me very much). | Scores are summed and multiplied by two for possible scores on each subscale ranging from zero to 42. | Reliability good (range 0.9 to 0.97). Convergent validity adequate (range 0.69 to 0.78) [57]. |

| Community Reintegration | Military to Civilian Questionnaire (M2C-Q) | 16-item self-report measure assessing post-deployment difficulties with reintegration (Social relations; Community engagement; Perceived meaning in life; Self-care and leisure; and Parenting) during the previous month. | Respondents rate the level of difficulty on a five-point scale from No Difficulty to Extreme Difficulty | Higher scores reflecting greater difficulty with reintegration. | Reliability good (0.95) [58]. |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms | The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) | 20-item self-report measure assesses symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder based on criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders – Version Five (DSM-5). | Each item is rated on a five-point scale with anchors from “not at all” to “extremely” indicating how much the participant has been bothered by the posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in the past month. | Items are summed and total scores range from zero to 80. Higher total scores reflect more severe posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. | Reliability good (0.95) [59]. |

| Pain Interference | Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) | Assesses severity of pain as well as the impact of pain on usual activity and sleep, on mood, and on stress levels. | Utilizes a numerical rating scale enhanced by functional word descriptors, color coding, and facial expressions matched to pain levels. | Participants need to meet at least a five for pain intensity or a five pain interference for study inclusion. | Reliability good (0.87). Test-retest reliability adequate (range 0.64 to 0.77). Interrater reliability good (0.95 to 0.96) [52]. |

| Avoidance / Acceptance | Acceptance and Action Questionnaire - II (AAQ-II) | Self-report to measure acceptance, or willingness to experience difficult thoughts/feelings in pursuit of doing what matters most (greater acceptance and lower avoidance). The AAQ measures mechanisms hypothesized to be at work in ACT treatments and has been found to mediate behavioral outcomes in ACT interventions. | Rate responses from Never True (1) to Always True (7) | Score the scale by summing the seven items. Higher scores reflect greater levels of avoidance. Lower summed scores reflect less avoidance and greater acceptance. | Reliability adequate to good (range 0.78 to 0.88). Test-retest reliability adequate to good (range 0.79 to 0.81) [60]. |

| Engagement in meaningful/valued life activities | Valued Living Questionnaire (VLQ) | Self-report measure assessing engagement in valued areas of life. | Importance rated from not at all important (1) to extremely important (10). Consistency rated from not at all consistent (1) to extremely consistent (10). | Importance and Consistency items are summed. Engagement is the discrepancy between Importance and Consistency sums. | Reliability adequate (range 0.65 to 0.77) [61]. |

| Exploratory Outcomes | |||||

| Self-reported service utilization | Self-report measure assessing frequency of visits for physical and emotional problems in inpatient, emergency room, and outpatient settings and frequency discussing emotional or functional problems during visits. | ||||

| COVID Distress | Pain Management Collaboratory (PMC) Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) Measures Final Version 2.0 05/20/20 | Eight-item self-report measure assessing how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted participants’ healthcare access, social support, finances, ability to meet basic needs, and mental health over the prior three months and whether they or others they live with were sick with COVID-19. [62,63] | Impact items rated from A LOT (a; a large negative impact) to IMPROVED (d; positive impact). | ||

Exclusion criteria include: 1) history of bipolar disorder or a primary psychotic diagnosis; 2) active suicidal ideation with current intent or plan; 3) current diagnosis of severe substance use disorder, other than alcohol or cannabis use disorders (obtained with the M.I.N.I. during baseline); 4) moderate to severe TBI (OSU TBI-ID); 5) neurological illness not related to a TBI; and 6) severe medical illness that could pose a significant stress burden.

Final inclusion/exclusion decisions are made by authors LD and RJ during weekly consensus meetings. During these meetings, research staff provide participant data gathered during the baseline assessment and chart review to inform final decisions about Veterans’ mental health diagnoses and TBI histories.

2.1.3. Randomization

This study uses cluster randomization with the workshops as the unit of randomization. The randomization sequence was generated in permuted blocks of four to ensure approximately equal distribution of the two interventions over the study period. Randomization to the ACT+ERS or ERS only group remains concealed until the beginning of each workshop to ensure both assessors and participants are blind to their condition until arrival.

2.1.4. Description of interventions

Veterans with polytrauma are randomized to a one-day ACT+ERS workshop or a one-day ERS only workshop. Educational workshops are commonly used in medical settings and offer valuable education that attends to patient concerns, making them credible controls. Additionally, the ERS workshops maximize our ability to determine the additive effects of ACT components on distress and reintegration, beyond support, education, and time with therapist. Two active conditions also allow for participant blinding and cluster randomization.

Each workshop includes three to eight Veterans, lasts approximately five hours, and is co-led by two therapists. All therapists are trained to deliver both ERS and ACT+ERS workshops. Based on Veteran feedback during the pilot study, group participants (not facilitators) are single gender. Several short breaks and a lunch break are provided throughout the workshop.

Two patient workbooks (1) ACT and (2) Educational as well as an ACT card deck were developed for this study. The ACT card deck consists of 11 cards depicting ACT concepts that serve to supplement and reinforce the information in the workshop and workbook. Participants in the ACT+ERS group receive all three items while those in the ERS group receive the educational workbook. Group facilitators assign homework at the end of each workshop. Veterans in ACT+ERS are asked to commit to engaging in an activity that is meaningful to them. Veterans in ERS workshops are asked to review the educational workbook, document any questions they may have, and practice using the problem-solving tools learned. A “Certificate of Completion” is provided to all workshop participants.

ERS only workshops

Information provided in the ERS workshop was compiled from existing VHA and community resources. Veterans are educated about 1) common difficulties and challenges with reintegration into civilian life; 2) mild TBI; 3) chronic pain; 4) symptoms of depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder and how these conditions do and do not impact daily life and functional ability; 5) other mental health difficulties commonly encountered by Veterans such as insomnia, substance use disorder, military sexual trauma, and moral injury; 6) problem solving skills [64]; and 7) treatment options and resources. In addition, therapists facilitate group discussion and mutual support surrounding these topics and lead the group through short deep breathing [65] and progressive muscle relaxation [66] exercises.

ACT + ERS workshops.

The goal of the ACT intervention is to help Veterans live rich and meaningful lives by cultivating psychological flexibility [31,35]. Emphasis is placed on helping Veterans 1) identify their “post-deployment mission” (i.e., their fundamental hopes, values, and goals); 2) cultivate the habit of committing to actions in line with their values; 3) willingly accept the unwanted feelings elicited by taking difficult actions consistent with their values; 4) notice thoughts for what they are rather than “truths” to be obeyed; 5) remain present by being mindful of thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations, including during distressing experiences; and 6) enhance their perspective-taking skills.

The clinical content of the ACT workshop has been described in pragmatic detail by Dindo and colleagues [47]. The acceptance and mindfulness portion of the workshop emphasizes new ways of managing troubling thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations and strategies to willingly face experiences that cannot be changed. The committed action portion of the workshop helps Veterans to clarify what matters most to them, what they want to stand for in life, how they want to behave, and what sorts of strengths and qualities they want to develop. Within this context, the workshop encourages engagement with actions consistent with valued directions, rather than avoiding those actions [67]. Examples and experiential exercises are based on information elicited from Veterans during the session. Finally, the same educational topics covered in ERS (listed above) are presented. In the ACT+ERS workshop, however, the follow-up discussion is based on ACT concepts rather than on the educational content. The manuals for the ACT+ERS and ERS Only workshops are available upon request.

2.1.5. Adaptations for online delivery due to COVID-19

While originally intended as an in-person intervention, all workshops to date have been conducted virtually over a secure Zoom connection due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Each workshop lasts approximately five hours and group sizes are targeted for three to eight Veterans per workshop. Prior to the workshop, assistance is provided to Veterans to set up Zoom and technical support is offered via telephone for the duration of the workshop. Veterans who do not have the proper equipment to attend a virtual workshop are loaned an iPad with internet capability.

To adapt the one-day ACT workshop to a virtual format, the research team created a PowerPoint presentation which provides a similar overall structure to the in-person workshop. While this adaptation somewhat limits facilitators’ flexibility to modify the sequence of the workshop, a menu of experiential exercises and metaphors within the slide deck allows facilitators to incorporate relevant examples in real time as specific issues are raised. The whiteboard feature within Zoom allows facilitators to interact with the slides and personalize the workshop to the attending Veterans. Similarly, the ERS workshop was converted to a PowerPoint presentation that mimics the overall structure of the in-person workshop, with videos embedded throughout to provide additional engaging education.

2.2. Therapist training and workshop fidelity

Facilitator manuals have been developed for both the ACT+ERS and ERS conditions to enhance uniformity in treatment delivery. Therapist training includes readings, watching recorded one-day ACT and ERS workshops conducted by established study therapists, and independently rating the sessions for fidelity. New therapists co-facilitate at least one of both types of workshops with an experienced facilitator prior to taking on a lead facilitator role in a workshop. Experienced ACT therapists, i.e., doctoral level therapists who have experience working with Veterans, have undergone the training for this study, and have previously conducted ACT workshops, will rate 20% of completed workshops to assess for therapist competence and content fidelity.

2.3. Measures

Veterans complete assessments at baseline, six weeks, three months, and six months post-workshop. Veterans who complete a workshop receive secure online survey invitations via email as well as phone and text message reminders to take the survey. If participants prefer, paper copies of these surveys are mailed to them. Participants are compensated $30 for each assessment completed up to $120 for completing all four assessments. See Table 1 for the list of screening, baseline, primary outcome, secondary outcome, and exploratory measures. See Fig. 1 for a timeline summarizing assessments from participant enrollment through completion.

3. Analytic plan

3.1. Sample SIZE justification

Sample size was estimated using the primary outcomes (DASS-21 and M2CQ) to determine the sample size needed to detect a clinically significant difference. We assumed an average of five participants per workshop (cluster) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) of 0.215 for the DASS-21 and 0.093 for the M2CQ [68]. A sample size of n = 180 (90 per group) is needed to detect a significant treatment by time interaction effect (p < .05) corresponding to difference in mean change at six months between treatment groups of at least 14.2 for DASS-21 (d = 0.58) and 5.9 for M2CQ (d = 0.5) with 0.80 power. Based on previous work, we assumed an attrition rate of 15%. To account for this, 212 subjects will be randomized to one of the two interventions.

3.2. Planned analyses

Following CONSORT guidelines, we will not test for differences in baseline characteristics or adjust analyses for any variables not selected a priori for use in the linear models. Descriptive statistics of all variables will be computed for each intervention group. Any significant differences between the groups will be used as covariates or effect moderators in the comparison of outcome measures between the treatment groups. Intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses will be conducted to assess treatment efficacy on primary and secondary outcomes using all Veterans that are randomized to a workshop.

3.2.1. Primary aim analyses

The primary aim of this study is to examine whether the ACT+ERS condition will result in greater reductions in distress (DASS-21) and improvements in reintegration (M2C-Q), compared to ERS only, at the six-month follow-up. We will use longitudinal, linear mixed-model analysis to compare ACT+ERS vs. ERS changes over time. The fixed effects in the mixed model will include treatment, time point (baseline and six months), treatment by time interaction, and a priori covariates. Covariates will include the differential changes over time between treatment groups in psychotherapy and psychiatric medications. These are defined as psychotherapy involvement during the previous time points (baseline, three months, and six months) and whether psychotropic medications were started or changed during the previous period. Participants will be nested within clinician teams (workshops) to account for correlations among participants treated by the same clinicians. The primary aim will be assessed from the result of the treatment by time interaction term. This parameter will indicate whether the within-group change at six months following treatment differs between the two treatment arms.

Similar analytic strategies will be used to examine the effects of the interventions on the secondary outcomes of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (PCL-5) and pain impact (DVPRS). A separate analysis will be performed to examine the effect of booster session attendance on the primary and secondary outcome measures. The number of subjects with and without booster sessions will be noted, and demographic and clinical characteristics of these participants will be compared. Booster session attendance status and an interaction effect with intervention group will be included in the mixed model analysis.

3.2.2. Secondary aim analyses

Mediation analysis will explore the causal pathway between intervention (ACT+ERS or ERS alone) and improvements in distress (DASS-21) and reintegration (M2C-Q) from baseline to six months. Increases in acceptance-based coping and reductions in behavioral avoidance (AAQ-II and VLQ) from baseline to three months will be used as mediators. With the independent variable X (intervention) randomized to workshops (clusters), and the mediator variables M (increases in acceptance-based coping, and reductions in behavioral avoidance), and the dependent variable Y (changes in distress & reintegration) measured at the subject level within clusters, we have a two-level hierarchy with a two-one-one design. Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling (MSEM) will be used to estimate and test the direct and indirect effects to assess multilevel mediation as described by Preacher, Zyphur, and Zhang (1993) [69].

3.2.3. Exploratory aims

Service utilization and medication use (Yes/No answers) at the three-month and six-month follow-ups will be compared for the ACT+ERS and ERS groups. A generalized linear model for binary responses (with logit link function) will be fitted using the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method to account for correlation of responses from subjects within the same workshop. Finally, we will examine if treatment benefits are constrained by demographics, severity of distress and dysfunction, number and type of coexistent psychiatric disorders with medical comorbidity (e.g., substance use, type, and severity of mTBI), time since deployment and number of deployments. We will estimate treatment effects in subgroups to address conditions in which ACT may be optimally useful. Moderation will be tested by including each separate moderator and interaction term between treatment condition and the moderator. A significant interaction will indicate that differences in treatment effects depend on the moderator. Simple slopes analyses will be conducted to follow-up significant interactions.

3.3. Missing data

Reasons for Veteran drop-out will be recorded and compared between treatment groups. Veteran characteristics and outcome measures collected prior to drop-out will be compared for those that drop out to those that complete the study. We expect valid parameter estimates under data Missing At Random (MAR); however, since distinguishing between MAR and data Missing Not At Random (MNAR) is not feasible, we will also perform sensitivity analyses using approaches recommended by Molenberghs and Kenward 94. The team will report differences between missing and non-missing participants, and possible reasons for missingness, in our follow-up publications.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary

Maladaptive coping responses exacerbate polytrauma’s effects in Veterans [9,15,16]. ACT targets avoidance reduction as one of its core mechanisms [31]. While VA currently offers ACT for depression, access to the program remains difficult for many Veterans due to both practical barriers and stigma surrounding mental health. This study aims to build on promising findings from a pilot study showing positive effects of a one-day ACT workshop (N = 20) compared to treatment as usual (TAU; N = 12) on reintegration and distress among Veterans with polytrauma. We are now conducting a more rigorous and adequately powered randomized controlled trial with 212 Veterans with polytrauma to compare the efficacy of the one-day ACT+ERS workshop to an active treatment comparison (ERS) on reintegration and distress. The ERS condition will control for specific treatment elements that pose rival explanations for the efficacy of ACT’s “active ingredients” such as therapist attention, expectation for improvement, education about polytrauma and resources for treatment, and group support. We will also examine mediators and moderators of treatment response to identify which ACT components are directly responsible for treatment effectiveness and whether treatment benefits are constrained by various personal factors.

4.2. Interpretations of potential findings

For psychological interventions to truly be considered a success, they need to be effective and disseminated. If the one-day ACT+ERS workshop results in greater improvements in mental health and reintegration compared to ERS only, greater effort can be directed towards disseminating ACT+ERS workshops in VAMC and other systems that serve Veterans with polytrauma. The one-day ACT+ERS workshops would provide evidence-based interventions to Veterans in a format that minimizes practical barriers. If the ACT+ERS and ERS conditions both result in similar improvements, the ERS workshop may be easier to teach as it requires less training and skill to deliver compared to the ACT+ERS workshop.

4.3. COVID-19 pandemic considerations

We made substantial changes to this study due to the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our team has been conducting workshops over Zoom for the safety of both participants and facilitators. Both ACT+ERS and ERS-only workshops were translated into PowerPoint presentations that facilitators use to help structure the online presentations. While the linear structure of a PowerPoint presentation closely mirrors the original in-person format of the ERS workshops, in-person ACT workshops were piloted using a more experiential format. Facilitators moved through the ACT Matrix [67] based on what Veterans’ discussed during the workshops while still ensuring fidelity to the planned content areas. In contrast, the ACT+ERS workshop PowerPoint dictates a more linear progression for presenting the Matrix concepts, although facilitators can still freely select which metaphors and exercises to use.

Because of these changes, the present study will act as an incidental pilot for providing one-day ACT+ERS/ERS workshops via video telehealth. Recent work investigating online and telehealth ACT interventions is promising [70–72] and is in line with work showing that telehealth is an effective method for conducting psychotherapy [73,74]. However, there is less research showing how translating one-day ACT workshops into an online format could impact efficacy. Should in-person workshops resume after the resolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, exploratory analyses will compare the outcomes of Veterans attending in-person vs. video telehealth workshops.

4.4. Limitations

Our sample will be drawn entirely from U.S. military Veterans who served in support of the Iraq or Afghanistan conflicts in the 20 years following the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom. As such, it is unclear how our findings will generalize to older U.S. military Veterans and individuals experiencing polytrauma due to events outside the context of an active warzone. Further, the primary and secondary outcome measures are all self-reported by the Veteran. Conclusions would be strengthened by the addition of other data sources including physiological measures, medical chart information, partner-reports, and/or behavioral-based functional data.

Finally, this study does not include a measure of stigma. It would have been valuable to assess whether the ACT+ERS and/or the ERS workshops result in reductions in stigma, and subsequent increases in service utilization.

5. Conclusions

Enhancing the community, social, and occupational reintegration and functioning of post-deployment Veterans so that they may function more fully in society is a key priority of the Veterans Health Administration. Those with mTBI and multiple coexistent conditions are particularly at risk for significant distress and dysfunction, and they are less likely to seek care. Despite the high prevalence of comorbid conditions among Veterans, existing treatments and service delivery approaches largely reflect fragmented, disease-specific care. Integrated, transdiagnostic treatments for comorbid physical and mental health symptoms are an increasingly valued approach for improving whole-person Veteran health and quality of life. As such, this work has the potential to improve the psychological health status of Veterans with specific needs using a novel intervention format.

Funding

This work was made possible by grant number 1 I01 RX003117-01A1 from the Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service awarded to Lilian N. Dindo and was partially supported by the use and resources of the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN13-413). The funding agency did not play a role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report. The opinions expressed reflect those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US government, or Baylor College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

To reduce the heterogeneity of our participant sample, the only inclusionary mood and anxiety disorders are MDD, PTSD, or GAD. These are the most common mood and anxiety disorders among post-911 Veterans with mTBI.

References

- [1].Department of Veterans Affairs, Analysis of VA Health Care Utilization among Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) Veterans, from 1st Quarter FY 2002 through 1st Quarter FY 2012, Accessed November 24, 2020, https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/epidemiology/healthcare-utilization-report-fy2015-qtr1.pdf, 2012.

- [2].US Department of Defense, VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress, 2010, pp. 1–48. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/cpg_PTSD-full-201011612.PDF. (Accessed 24 November 2020).

- [3].Cifu DX, Taylor BC, Carne WF, et al. , Traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and pain diagnoses in OIF/OEF/OND veterans, J. Rehabil. Res. Dev 50 (9) (2013) 1169–1176, 10.1682/JRRD.2013.01.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Seal KH, Bringing the war back home: mental health disorders among 103 788 US veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at Department of Veterans Affairs Facilities, Arch. Intern. Med 167 (5) (2007) 476, 10.1001/archinte.167.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tanielian TL, Tanielian T, Jaycox L, Invisible wounds of war: psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery, in: Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery, Rand Corporation, 2008, pp. 87–115. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL, Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care, N. Engl. J. Med 351 (1) (2004) 13–22, 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lew HL, Otis JD, Tun C, Kerns RD, Clark ME, Cifu DX, Prevalence of chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and persistent postconcussive symptoms in OIF/OEF veterans: polytrauma clinical triad, J. Rehabil. Res. Dev 46 (6) (2009) 697–702, 10.1682/jrrd.2009.01.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. , Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans, J. Trauma. Stress 28 (1) (2015) 25–33, 10.1002/jts.21979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Phillips KM, Clark ME, Gironda RJ, et al. , Pain and psychiatric comorbidities among two groups of Iraq and Afghanistan era veterans, J. Rehabil. Res. Dev 53 (4) (2016) 413–432, 10.1682/JRRD.2014.05.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Evans D, Charney D, Lewis L, et al. , Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations, Biol. Psychiatry 58 (2005) 175–189, 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Whiteneck GG, Cuthbert JP, Corrigan JD, Bogner JA, Risk of negative outcomes after traumatic brain injury: a statewide population-based survey, J. Head Trauma Rehabil 31 (1) (2016), E43, 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pugh MJ, Swan AA, Carlson KF, et al. , Traumatic brain injury severity, comorbidity, social support, family functioning, and community reintegration among veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil 99 (2) (2018) S40–S49, 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Combs HL, Berry DTR, Pape T, et al. , The effects of mild traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and combined mild traumatic brain injury/post-traumatic stress disorder on returning veterans, J. Neurotrauma 32 (13) (2015) 956–966, 10.1089/neu.2014.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Barnes DE, Byers AL, Strigo I, Yaffe K, Association of traumatic brain injury with chronic pain in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans: effect of comorbid mental health conditions, Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil 98 (8) (2017) 1636–1645, 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Moos RH, Schaefer JA, Coping resources and processes: current concepts and measures, in: Handbook of Stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects, 2nd ed., Free. Press, 1993, pp. 234–257. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Spelman JF, Hunt SC, Seal KH, Burgo-Black AL, Post deployment care for returning combat veterans, J. Gen. Intern. Med 27 (9) (2012) 1200–1209, 10.1007/s11606-012-2061-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Johnson SC, et al. , Are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using mental health services? New data from a national random-sample survey, Psychiatr. Serv 64 (2) (2013) 134–141, 10.1176/appi.ps.004792011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mott JM, Hundt NE, Sansgiry S, Mignogna J, Cully JA, Changes in psychotherapy utilization among veterans with depression, anxiety, and PTSD, Psychiatr. Serv 65 (1) (2014) 106–112, 10.1176/appi.ps.201300056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Goetter EM, Bui E, Ojserkis RA, Zakarian RJ, Brendel RW, Simon NM, A systematic review of dropout from psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans, J. Trauma. Stress 28 (5) (2015) 401–409, 10.1002/jts.22038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM, Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans, PS. 60 (8) (2009) 1118–1122, 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tanielian T, Woldetsadik MA, Jaycox LH, et al. , Barriers to engaging service members in mental health care within the U.S. Military Health System, PS. 67 (7) (2016) 718–727, 10.1176/appi.ps.201500237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stecker T, Shiner B, Watts BV, Jones M, Conner KR, Treatment-seeking barriers for veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts who screen positive for PTSD, PS. 64 (3) (2013) 280–283, 10.1176/appi.ps.001372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zinzow HM, Britt TW, McFadden AC, Burnette CM, Gillispie S, Connecting active duty and returning veterans to mental health treatment: interventions and treatment adaptations that may reduce barriers to care, Clin. Psychol. Rev 32 (8) (2012) 741–753, 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].True G, Rigg KK, Butler A, Understanding barriers to mental health care for recent war veterans through photovoice, Qual. Health Res 25 (10) (2015) 1443–1455, 10.1177/1049732314562894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Garcia HA, Finley EP, Ketchum N, Jakupcak M, Dassori A, Reyes SC, A survey of perceived barriers and attitudes toward mental health care among OEF/OIF veterans at VA outpatient mental health clinics, Mil. Med 179 (3) (2014) 273–278, 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mott JM, Grubbs KM, Sansgiry S, Fortney JC, Cully JA, Psychotherapy utilization among rural and urban veterans from 2007 to 2010, J. Rural. Health 31 (3) (2015) 235–243, 10.1111/jrh.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Blevins D, Roca JV, Spencer T, Life guard: evaluation of an ACT-based workshop to facilitate reintegration of OIF/OEF veterans, Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract 42 (1) (2011) 32, 10.1037/a0022321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Blais RK, Renshaw KD, Stigma and demographic correlates of help-seeking intentions in returning service members, J. Trauma. Stress 26 (1) (2013) 77–85, 10.1002/jts.21772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gorman LA, Blow AJ, Ames BD, Reed PL, National guard families after combat: mental health, use of mental health services, and perceived treatment barriers, PS. 62 (1) (2011) 28–34, 10.1176/ps.62.1.pss6201_0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mittal D, Drummond KL, Blevins D, Curran G, Corrigan P, Sullivan G, Stigma associated with PTSD: perceptions of treatment seeking combat veterans, Psychiatric Rehabilit. J 36 (2) (2013) 86, 10.1037/h0094976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hayes SC, Levin ME, Plumb-Vilardaga J, Villatte JL, Pistorello J, Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy, Behav. Ther 44 (2) (2013) 180–198, 10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dimidjian S, Arch JJ, Schneider RL, Desormeau P, Felder JN, Segal ZV, Considering Meta-analysis, meaning, and metaphor: a systematic review and critical examination of “third wave” cognitive and behavioral therapies, Behav. Ther 47 (6) (2016) 886–905, 10.1016/j.beth.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Graham CD, Gouick J, Krahé C, Gillanders D, A systematic review of the use of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in chronic disease and long-term conditions, Clin. Psychol. Rev 46 (2016) 46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Öst L-G, Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Behav. Res. Ther 46 (3) (2008) 296–321, 10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Powers MB, Vörding MBZVS, Emmelkamp PMG, Acceptance and commitment therapy: a meta-analytic review, PPS. 78 (2) (2009) 73–80, 10.1159/000190790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ruiz FJ, Acceptance and commitment therapy versus traditional cognitive behavioral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current empirical evidence, Int. J. Psychol 12 (2012) 333–357. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ruiz FJ, A review of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies, Int. J. Psychol 10 (2010) 125–162. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kangas M, McDonald S, Is it time to act? The potential of acceptance and commitment therapy for psychological problems following acquired brain injury, Neuropsychol Rehabil. 21 (2) (2011) 250–276, 10.1080/09602011.2010.540920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Whiting D, Deane F, McLeod H, Ciarrochi J, Simpson G, Can acceptance and commitment therapy facilitate psychological adjustment after a severe traumatic brain injury? A pilot randomized controlled trial, Neuropsychol Rehabil. 30 (7) (2020) 1348–1371, 10.1080/09602011.2019.1583582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Walser RD, Karlin BE, Trockel M, Mazina B, Taylor C Barr, Training in and implementation of acceptance and commitment therapy for depression in the veterans health administration: therapist and patient outcomes, Behav. Res. Ther 51 (9) (2013) 555–563, 10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Walser RD, Garvert DW, Karlin BE, Trockel M, Ryu DM, Taylor CB, Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in treating depression and suicidal ideation in veterans, Behav. Res. Ther 74 (2015) 25–31, 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Flaxman PE, Bond FW, A randomised worksite comparison of acceptance and commitment therapy and stress inoculation training, Behav. Res. Ther 48 (8) (2010) 816–820, 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dindo L, Van Liew JR, Arch JJ, Acceptance and commitment therapy: a transdiagnostic behavioral intervention for mental health and medical conditions, Neurotherapeutics. 14 (3) (2017) 546–553, 10.1007/s13311-017-0521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dindo L, One-day Acceptance and Commitment Training workshops in medical populations, Curr. Opin. Psychol 2 (2015) 38–42, 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Arcury TA, Gesler WM, Preisser JS, Sherman J, Spencer J, Perin J, The effects of geography and spatial behavior on health care utilization among the residents of a rural region, Health Serv. Res 40 (1) (2005) 135–155, 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Pekarik G, Wierzbicki M, The relationship between clients’ expected and actual treatment duration, Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train 23 (4) (1986) 532, 10.1037/h0085653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dindo L, Johnson AL, Lang B, Rodrigues M, Martin L, Jorge R, Development and evaluation of an 1-day acceptance and commitment therapy workshop for veterans with comorbid chronic pain, TBI, and psychological distress: outcomes from a pilot study, Contemp. Clin. Trials 90 (2020) 105954, 10.1016/j.cct.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Corrigan JD, Bogner J, Initial reliability and validity of the Ohio State University TBI identification method, J. Head Trauma Rehabil 22 (6) (2007) 318–329, 10.1097/01.HTR.0000300227.67748.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Shin C, Lee S-H, Han K-M, Yoon H-K, Han C, Comparison of the usefulness of the PHQ-8 and PHQ-9 for screening for major depressive disorder: analysis of psychiatric outpatient data, Psychiatry Investig. 16 (4) (2019) 300–305, 10.30773/pi.2019.02.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B, A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7, Arch. Intern. Med 166 (10) (2006) 1092–1097, 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E, et al. , The Mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI, European Psychiatry. 12 (5) (1997) 224–231, 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Polomano RC, Galloway KT, Kent ML, et al. , Psychometric testing of the defense and veterans pain rating scale (DVPRS): a new pain scale for military population, Pain Med. 17 (8) (2016) 1505–1519, 10.1093/pm/pnw105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Löwe B, Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection, Ann. Intern. Med 146 (5) (2007) 317–325, 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ruiz MA, Zamorano E, García-Campayo J, Pardo A, Freire O, Rejas J, Validity of the GAD-7 scale as an outcome measure of disability in patients with generalized anxiety disorders in primary care, J. Affect. Disord 128 (3) (2011) 277–286, 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Donnelly KT, Donnelly JP, Dunnam M, et al. , Reliability, sensitivity, and specificity of the VA traumatic brain injury screening tool, J. Head Trauma Rehabil 26 (6) (2011) 439–453, 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182005de3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Pettersson A, Modin S, Wahlström R, Winklerfelt AF, Hammarberg S, Krakau I, The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview is useful and well accepted as part of the clinical assessment for depression and anxiety in primary care: a mixed-methods study, BMC Fam. Pract 19 (1) (2018) 19, 10.1186/s12875-017-0674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Crawford J, Henry J, The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS): normative data and latent structure in a large non-clinical sample, Br. J. Clin. Psychol (2003), 10.1348/014466503321903544. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sayer NA, Frazier P, Orazem RJ, et al. , Military to civilian questionnaire: a measure of postdeployment community reintegration difficulty among veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs medical care, J. Trauma. Stress 24 (6) (2011) 660–670, 10.1002/jts.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hall BJ, Yip PSY, Garabiles MR, Lao CK, Chan EWW, Marx BP, Psychometric validation of the PTSD Checklist-5 among female Filipino migrant workers, Eur. J. Psychotraumatol 10 (1) (2019), 10.1080/20008198.2019.1571378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, et al. , Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance, Behav. Ther 42 (4) (2011) 676–688, 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wilson K, Sandoz E, Kitchens J, Roberts M, The valued living questionnaire: defining and measuring valued action within a behavioral framework, Psychol. Rec 60 (2010) 249–272, 10.1007/BF03395706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Coleman BC, Kean J, Brandt CA, Peduzzi P, Kerns RD, Adapting to disruption of research during the COVID-19 pandemic while testing nonpharmacological approaches to pain management, Transl Behav Med. Published online September 4 (2020), 10.1093/tbm/ibaa074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Pain Management Collaboratory Coordinating Center, Phenotypes and Outcomes Workgroup, Pain Management Collaboratory (PMC) Coronavirus Pandemic Measures, Accessed April 27, 2021, https://painmanagementcollaboratory.org/pain-management-collaboratory-pmc-coronavirus-pandemic-measures/.

- [64].D’Zurilla TJ, Goldfried MR, Problem solving and behavior modification, J. Abnorm. Psychol 78 (1) (1971) 107–126, 10.1037/h0031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Jerath R, Edry JW, Barnes VA, Jerath V, Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: neural respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system, Med. Hypotheses 67 (3) (2006) 566–571, 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Carlson CR, Hoyle RH, Efficacy of abbreviated progressive muscle relaxation training: a quantitative review of behavioral medicine research, J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 61 (6) (1993) 1059–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wilson KG, The ACT Matrix: A New Approach to Building Psychological Flexibility Across Settings and Populations, Illustrated edition, Context Press, 2014. (Polk KL, Schoendorff B, eds.). [Google Scholar]

- [68].Dindo L, Weinrib A, Marchman J, One-day ACT workshops for patients with chronic health problems and associated emotional disorders, in: Krafft J, Levin ME, Twohig ME (Eds.), Innovations in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Clinical Advancements and Applications in ACT, New Harbinger Publications, 2020, p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z, A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation, Psychol. Methods 15 (3) (2010) 209, 10.1037/a0020141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Chapoutot M, Peter-Derex L, Schoendorff B, Faivre T, Bastuji H, Putois B, Telehealth-delivered CBT-I programme enhanced by acceptance and commitment therapy for insomnia and hypnotic dependence: A pilot randomized controlled trial, J. Sleep Res 30 (1) (2021), 10.1111/jsr.13199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Herbert MS, Afari N, Liu L, et al. , Telehealth versus in-person acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a randomized noninferiority trial, J. Pain 18 (2) (2017) 200–211, 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Bricker JB, Mull KE, Sullivan BM, Forman EM, Efficacy of telehealth acceptance and commitment therapy for weight loss: a pilot randomized clinical trial, Transl. Behav. Med (2021), 10.1093/tbm/ibab012. Published online March 31. ibab012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Gentry MT, Lapid MI, Clark MM, Rummans TA, Evidence for telehealth group-based treatment: a systematic review, J. Telemed. Telecare 25 (6) (2019) 327–342, 10.1177/1357633X18775855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Reay RE, Looi JC, Keightley P, Telehealth mental health services during COVID-19: summary of evidence and clinical practice, Australas Psychiatry. 28 (5) (2020) 514–516, 10.1177/1039856220943032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]