Abstract

Objective:

To compare the effectiveness of two interventions in improving prescribing of guideline-concordant durations of therapy for acute otitis media (AOM).

Study design:

This was a quasi-experimental mixed methods analysis that compared a bundled quality improvement intervention consisting of individualized audit and feedback, education, and electronic health record (EHR) changes to an EHR-only intervention. The bundle was implemented in 3 pediatric clinics from January-August 2020 and an EHR-only intervention was implemented in 6 family medicine clinics. The primary outcome measure was prescription of an institutional guideline-concordant 5-day duration of therapy for children ≥ 2 years of age with uncomplicated AOM. Propensity score matching and differences-in-differences analysis weighted with inverse probability of treatment were completed. Implementation outcomes were assessed using RE-AIM. Balance measures included treatment failure and recurrence.

Results:

In total, 1,017 encounters for AOM were included from February 2019-August 2020. Guideline-concordant prescribing increased from 14.4% to 63.8% (difference=49.4%) in clinics that received the EHR-only intervention and from 10.6% to 85.2% (difference=74.6%) in clinics that received the bundled intervention. In the adjusted analysis the bundled intervention improved guideline-concordant durations by an additional 26.4% (P < .01) compared with the EHR-only intervention. Providers identified EHR-prescription field changes as the most helpful components. There were no differences in treatment failure or recurrence rates between baseline and either intervention.

Conclusion:

Both interventions resulted in improved prescribing of guideline-concordant durations of antibiotics. The bundled intervention improved prescribing more than an EHR-only intervention and was acceptable to providers.

Acute otitis media (AOM) is the most commonly cited indication for antibiotics in children accounting for 24% of all pediatric antibiotic prescriptions and affects 60% of children by 3 years of age.(1, 2) The overuse of antibiotics is associated with a collection of concerning risks and potential harms to children including the development of antibiotic resistant organisms(3), increased adverse drug events(4), and microbiome changes that place children at risk for chronic diseases later in life.(5, 6) Additionally the overuse of antibiotics places patients at higher risk for Clostridioides difficile infection(7) and increases health care costs.(8)

The White House National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria identified benchmarks to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use in outpatient settings by 50%.(9) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also established outpatient antibiotic prescribing as a primary focus for combating antimicrobial resistance.(10)

One method to reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure is to use the shortest duration of antibiotics needed to treat the infection. For most children ≥ 2 years of age, 5–7 days, rather than 10 days, of antibiotics have been shown to be sufficient to treat AOM.(11) This is reflected in current national guidelines, which recommend short courses of antibiotics for non-severe disease in this age group.(12) At Denver Health, institutional guidance recommending 5 days of therapy for children ≥2 years of age with AOM has been available in a clinical care guideline since 2010 and on a mobile antibiotic stewardship app since 2016.(13) Despite these recommendations, in 2018 94% of children ≥2 years of age at our institution received longer than recommended antibiotic durations for AOM and 41% of antibiotic exposure days for AOM could have been averted if the institutional recommendations were followed.(14)

To date, studies aimed at improving prescribing for AOM have primarily focused on promoting the use of first-line antibiotics.(15, 16) Our data suggested that first-line antibiotic selection at DH was high (81% first-line amoxicillin, 18% second-line amoxicillin-clavulanate) and preventing unnecessarily prolonged antibiotic courses would be the most impactful stewardship intervention for AOM.(14) Bundled antibiotic stewardship interventions that include audit and feedback of prescribing practices to providers, education, and clinical decision support have been shown to be effective in improving antibiotic prescribing for AOM.(16) Additionally, for other diagnoses, such as urinary tract infections and skin and soft tissue infections, bundled interventions have been effective in reducing the duration of antibiotics prescribed.(17, 18) Unfortunately, bundled stewardship interventions can be resource intensive which may limit their generalizability. It is unclear what benefit electronic decision support alone, which may be more economical than bundled programs, has in improving antibiotic prescribing.

Therefore, we aimed to determine the effectiveness of a bundled antibiotic stewardship intervention compared with an electronic health record (EHR)-only intervention in reducing prescribing of longer than institution-recommended durations of antibiotics for AOM for children age 2 to 18 years of age.

Methods:

This was a quasi-experimental mixed-methods evaluation of two pilot interventions to reduce prescribing of longer than institution-recommended durations of antibiotics for AOM. The interventions took place from January-August 2020 at DH, a large, urban, academically affiliated, integrated health system comprised of 28 federally qualified health care centers (FQHC; 10 clinics + 18 school based health centers), 3 urgent care centers, and a level one trauma center that includes a pediatric emergency department. The system is the region’s primary safety-net health system and 75% of patients served are at or below 150% of the federal poverty level.(19) This pilot evaluation included the 3 DH primary pediatric clinics and 6 family medicine clinics (Table I). Urgent and emergency care centers were not included in the analysis because a concurrent stewardship intervention was implemented during the time period. School based health centers were also not included because they were closed for a large portion of the intervention period.

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of eligible patients with AOM during the study periods in each intervention group (n=1017).

| EHRa-Only Intervention (n=514) | Bundled Intervention (n=503) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention N (%) N=409 |

Post-intervention N (%) N=105 |

P-value | Pre-intervention N (%) N=388 |

Post-intervention N (%) N=115 |

P-value | |

| Age mean (SD) y. | 5.5 (3.9) | 6.2 (4.2) | 0.10 | 5.8 (3.8) | 6.0 (4.0) | 0.54 |

| Gender | 0.56 | 0.28 | ||||

| Male | 200 (48.9) | 48 (45.7) | 194 (50.0) | 51 (44.4) | ||

| Female | 209 (51.1) | 57 (54.3) | 194 (50.0) | 64 (55.7) | ||

| Race | 0.01 | 0.71 | ||||

| Black | 54 (13.2) | 4 (3.8) | 44 (11.3) | 10 (8.7) | ||

| White | 310 (75.8) | 92 (87.6) | 296 (76.3) | 91 (79.1) | ||

| Other | 45 (11.0) | 9 (8.6) | 48 (12.4) | 14 (12.2) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 125 (30.6) | 21 (20.0) | 108 (27.8) | 32 (27.8) | ||

| Hispanic | 284 (69.4) | 84 (80.0) | 280 (77.2) | 83 (72.2) | ||

| Insurance | 0.80 | 0.36 | ||||

| Commercial | 35 (8.6) | 12 (11.4) | 38 (9.8) | 14 (12.2) | ||

| Public | 355 (86.8) | 89 (84.8) | 343 (88.4) | 98 (85.2) | ||

| Uninsured | 8 (2.0) | 2 (1.9) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 11 (2.6) | 2 (1.9) | 4 (1.0) | 3 (2.6) | ||

Electronic Health Record (EHR)

Interventions:

The primary focus of the interventions was to promote institutional guideline-concordant duration of therapy for AOM in children 2 years and older through adherence to DH’s recommendation for 5 days of therapy for this group. A bundled antimicrobial stewardship intervention structured around the CDC Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic stewardship(10) was implemented in the three primary pediatric clinics. An electronic health record (EHR)-only intervention was implemented across the remainder of the DH ambulatory care system, including the 6 comparison family medicine clinics selected for the analysis (Intervention Components are available in Table 2; available at www.jpeds.com). Given the high potential for intervention diffusion within each specialty, family medicine and pediatric clinics could not be randomized to each intervention.

Table 2, online:

Components of the bundled and electronic health record (EHR)-only antimicrobial stewardship interventions for acute otitis media.

| Bundled | EHR-Only | |

|---|---|---|

| EHR Changes- Antibiotic Prescriptionsa | ||

| Hyperlink to internal clinical care guidelines | • | • |

| “Help” text in upper prescription field | • | • |

| Quick select buttons for dosage in mg/kg | • | • |

| Quick select buttons for duration 5 & 10 days | • | • |

| Education | ||

| Pediatric Grand Roundsb | • | |

| On-site small group session | • | |

| Infographic for providers | • | |

| Patient education materials | • | |

| Audit and Feedback (monthly) | • | |

| Access to clinical care guidelines via website and appc | • | • |

| Informed of EHR changes | • | • |

| Informed of other intervention components, current clinical care guidelines, and monitoring | • | |

| Eligible for American Board of Pediatrics Maintenance of Certification Credit | • |

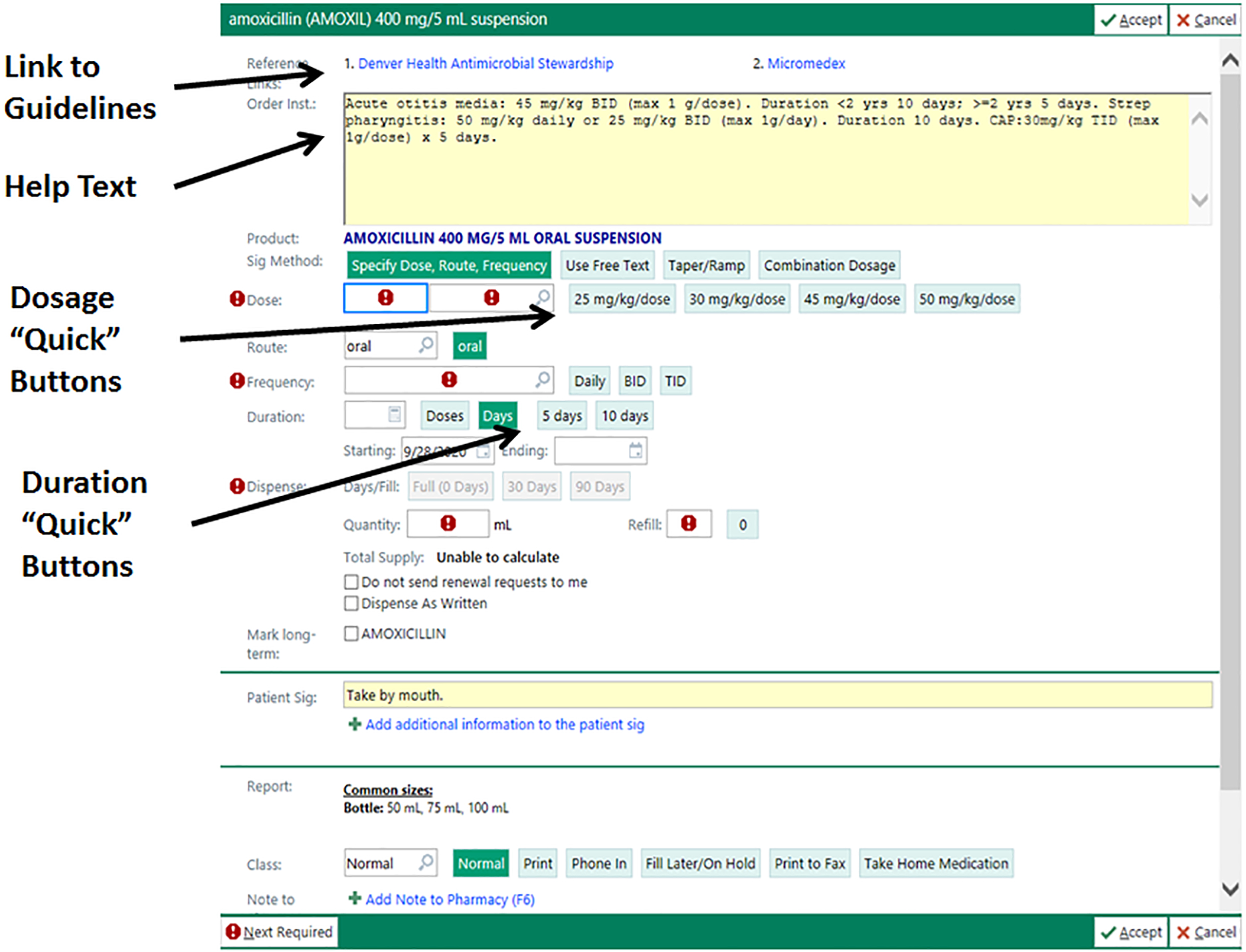

Electronic Health Record- amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, and cefdinir antibiotic prescription fields were changed. Figure 4; online shows EHR modifications.

Grand Rounds is publically viewable, but is attended predominantly by pediatricians. Family medicine clinics have a separate Grand Rounds during the same time and, therefore, are unlikely to attend Pediatric Grand Rounds.

Available for providers since 2010 online and 2016 in an antimicrobial stewardship app.

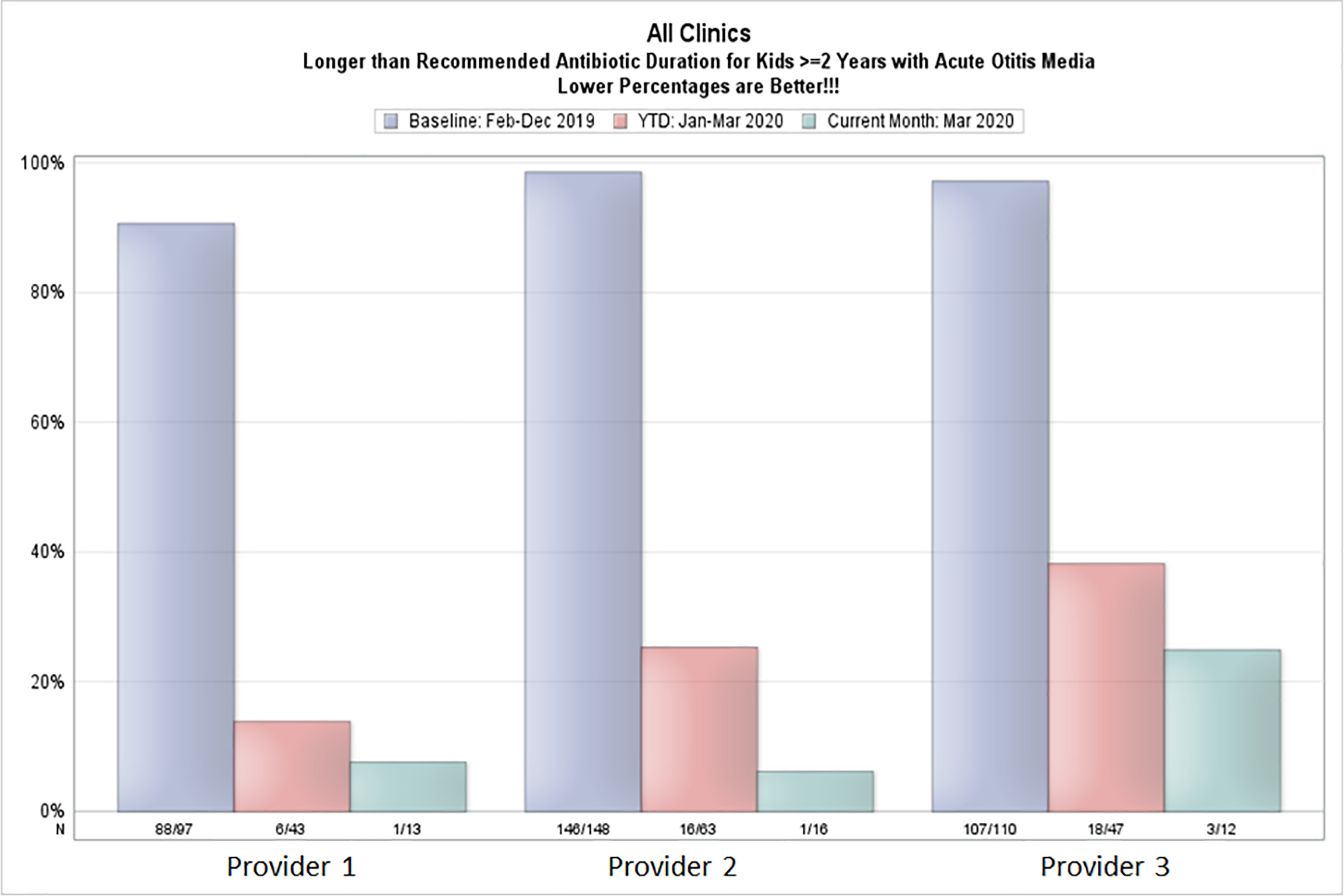

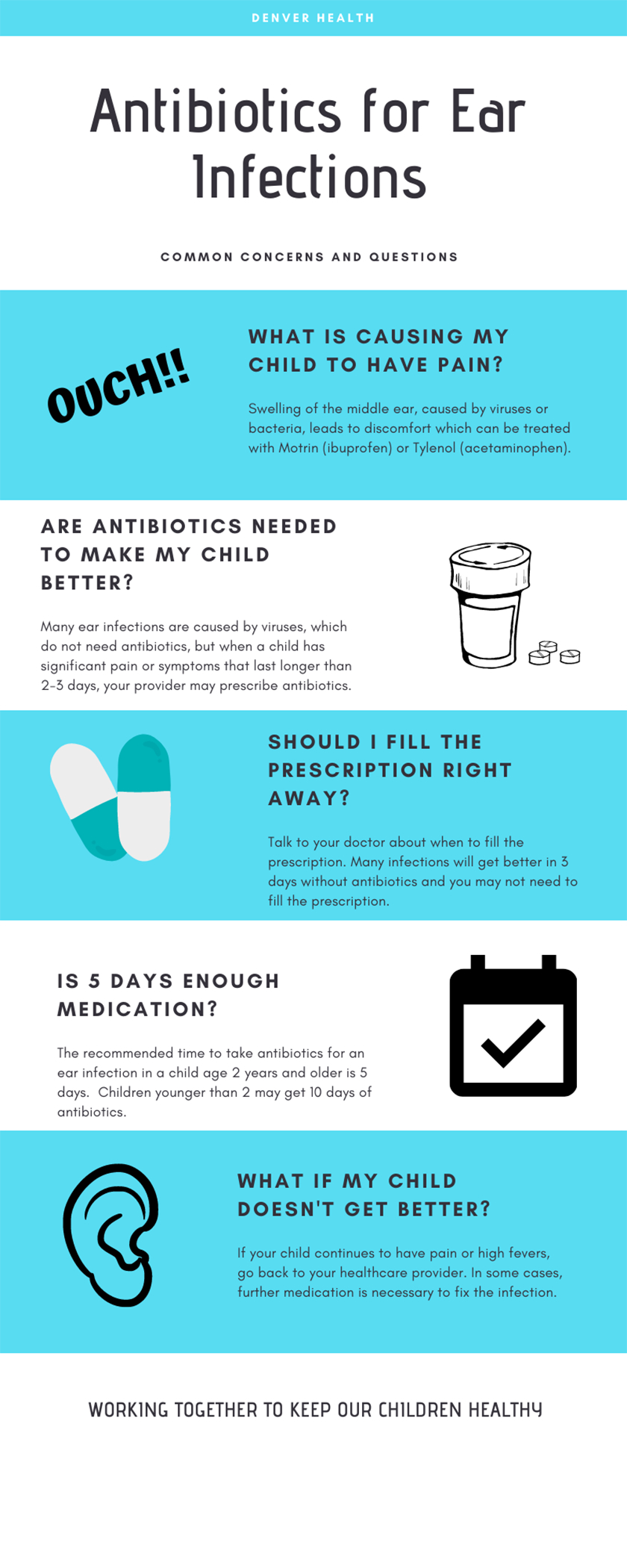

The bundled intervention included monthly individualized provider audit and feedback with peer comparison) education and electronic decision support in the EHR (Epic, Verona, WI; Figures 1–4; available at www.jpeds.com). Audit and feedback reports were created using the DH Outpatient Automated Stewardship Information System (OASIS©, Denver, CO) method, which electronically abstracts data from the EHR, analyzes the data, and creates recurring reports that are sent to provider emails automatically.(21) Provider and clinic level data were reported to providers monthly. Reports included bar graphs that showed the proportion of patients age 2 years and older with uncomplicated AOM who were prescribed an institutional guideline-concordant duration of therapy. Bars were generated for baseline data from 2019, year to date data (Jan 2020-present month), and current month. Per the preference of the DH Pediatric Quality Improvement Committee, in order to be as transparent as possible, provider names were not anonymized in the reports (Figure 1). Education was provided at Pediatric Grand Rounds and via an on-site small group session at each pediatric clinic. Prescribing infographics and patient education materials were also provided (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1; online:

Example individualized provider audit and feedback report generated with OASIS©

Figure 4, online:

Electronic health record changes made to prescription fields for amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, and cefdinir for both intervention groups.

Footnote: © 2021 Epic Systems Corporation

Figure 2, online:

Caregiver handout and education

Figure 3, online:

Provider posters

The EHR changes included a hyperlink to DH clinical care guidelines for common pediatric infections, help text that offered syndrome specific guidance on antibiotic selection and durations of therapy, and quick buttons to select the appropriate dosing and duration of therapy (Figure 4). EHR changes were made to the most common antibiotics prescribed for children at DH including amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, and cefdinir suspensions, capsules, and tablets. Provider EHR “favorites” were reset for all providers to assure providers updated their favorites with the modifications.

Providers in the bundled intervention group were informed of the intervention prior to and during implementation via email and provider meetings and were eligible for American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) Part 4 Maintenance of Certification (MOC) credit for participating. Providers in the EHR-only group had ongoing access to clinical care guidelines and all EHR changes. They were informed of EHR changes via a system email that included details about other, unrelated, EHR changes, but were not otherwise informed of the project or data monitoring. Pediatric Grand Rounds presentations were publicly available, though they are not commonly attended by providers who are not pediatricians.

All program components were fully implemented during January 2020.

Primary Outcome Measure:

The primary outcome measure was antibiotic prescriptions for children 2 years and older with uncomplicated AOM with an institutional guideline-concordant, 5-day duration of therapy. This outcome was compared between the 3 pediatric clinics receiving the bundled intervention and the 6 family medicine clinics that received the EHR-only intervention.

Encounters for patients 2–18 years of age during the study period were included when a patient had an International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 code for AOM (Appendix; available at www.jpeds.com) and was prescribed an antibiotic. To ensure only patients with uncomplicated AOM were included, patients who received an antibiotic within 30 days prior to the visit, had a history of tympanostomy tubes, or who had a competing bacterial diagnosis (e.g. pneumonia) were excluded. Patients who received intramuscular antibiotics were excluded because this treatment option entails only a single dose of antibiotics; similarly, patients who were prescribed azithromycin were excluded because 5-day prescriptions of this long half-life antibiotic are standard, but azithromycin is not a recommended antibiotic for AOM. Azithromycin and ceftriaxone are prescribed to less than 1.5% of AOM patients at DH.(14)

We calculated summary statistics for the patient demographic characteristics using t tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared or Fisher exact tests (if cell counts <5) for categorical variables. Difference-in-differences analysis was utilized to evaluate the change in guideline-concordant duration of antibiotics during the pre- and post-intervention periods in the bundled and EHR-only intervention groups. A pre-intervention period of February 2019 to December 31, 2019 was selected, and a post-intervention period of January 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020 was utilized. An analysis to evaluate if the COVID-19 pandemic affected the intervention effectiveness was completed and it was determined that separation of pre-COVID and COVID time periods in the post-intervention period was not necessary for the analysis (Table 3; available at www.jpeds.com). To assess parallel trends in the pre-intervention period, we ran a placebo differences-in-differences regression with only pre-intervention data, using May 10, 2019 as the cut-off date to balance the data. We did not find a significant pre-intervention trend, with the difference-in-differences estimator coefficient being 0.078 (p=0.09). Due to potential differences in the patient population between the family medicine and pediatric clinics, we obtained propensity scores by estimating the probability that the patient was included in each intervention cohort based on age, sex, insurance, race, and ethnicity. Subsequently, we used these scores to obtain the inverse probability of treatment duration, which we used to weight the regression model along with controlling for covariates (Appendix). All analyses were conducted in SAS Enterprise Guide (version 7.11).

Table 3; online:

Sub-analysis analyzing the difference in rates of 5-day duration prescriptions prescribed during the intervention period to assess whether the rates were impacted by COVID-19. January 1, 2020-March 31,2020 was used as the pre-COVID-19 intervention period and April 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020 as the post-COVID-19 intervention period. The COVID-19 pandemic did not have a significant impact during the intervention period on prescribing rates. However, a sharp decrease in the number of total visits was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Intervention | Time-Period | 5-Day Duration (%) | Total Visits | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHR-only | Pre-COVID | 76 (49.0) | 155 | 0.77 |

| Post-COVID | 5 (41.7) | 12 | ||

| Bundled | Pre-COVID | 109 (73.7) | 148 | 0.68 |

| Post-COVID | 16 (69.6) | 23 |

Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test

Implementation Outcome Measures:

Implementation outcomes were analyzed for the bundled intervention using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework (Table 4; available at www.jpeds.com).(22) Key stakeholders, including the DH Community Advisory Panel, the Pediatric Quality Improvement Workgroup, and clinic administrators were engaged to determine what program adaptations were needed for successful implementation. The fidelity of the intervention was measured by monitoring read receipts for audit and feedback reports, provider attendance at education sessions, and meeting ABP Part 4 MOC credit requirements. Implementation was also evaluated through provider surveys at the end of the intervention that evaluated providers’ perceptions of their changes in prescribing as a result of the intervention (Table 5; available at www.jpeds.com). Surveys were administered using Qualtrics (Provo, UT) and were emailed to all providers in the 3 clinics where the bundled intervention was implemented. Maintenance and sustainability were evaluated at the end of the intervention using a modified Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool (CSAT; Table 6 [available at www.jpeds.com]) in Qualtrics.(23) The CSAT is a validated sustainability tool that has been reliability tested. Higher scores indicate high likelihood of sustainability across 7 domains. CSAT survey links were emailed to providers in the 3 clinics where the bundled intervention was implemented and the provider administrator at each of the bundled intervention clinics.

Table 4; online:

Implementation Outcomes Measured using RE-AIM Framework

| Component | Project Questions | Outcome Measure | Evaluation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | • How many patients can be reached by the interventions? | • # of patients 2–18 years of age with uncomplicated AOM | • Descriptive Statistics |

| Effectiveness | • Do the interventions reduce unnecessarily long durations of antibiotics for children with AOM? | • Change in percentage of patients who receive longer than 5 days of antibiotics | • Interrupted Time Series Analyses |

| Adoption | • Does the program need to be modified to meet local needs? | • Intervention adaptations made | • Formative evaluation with stakeholders including clinic administrators, Pediatric Quality Improvement Workgroup, and Community Advisory Panel |

| Implementation | • How many providers participate in intervention components? • Are providers satisfied with the program? |

Fidelity: • Percentage of providers who read ≥50% of feedback emails • Mean number of feedback emails read • Percentage of providers who attended Pediatric Grand Rounds • Percentage of providers who attended small group education sessions. • Percentage of providers who complete ABP Part 4 MOC Requirements |

Fidelity: • Read receipts on feedback emails • Attendance at education sessions • Completion of ABP Part 4 MOC Requirements |

| Provider satisfaction • Provider satisfaction with each program component |

Provider satisfaction • Provider surveys |

||

| Maintenance | • Is the program sustainable? • Could the program be implemented in resource limited settings? |

• Clinical sustainability score | • Post-implementation survey of program managers, administrators, and clinician champions (CSAT) |

Table 5; online:

Survey results for providers who participated in the bundled intervention.

| Survey Question | N (%) N=23 Score=1 |

N (%) N=23 Score=2 |

N (%) N=23 Score=3 |

N (%) N=23 Score=4 |

Weighted Average (max=4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Helpfulness of each program component | Not aware of change | Not helpful | Moderately helpful | Very helpful | |

|

| |||||

| Presentation at grand rounds | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 8 (35) | 13 (57) | 3.4 |

| Provider small group meeting at your clinic | 2 (9) | 2 (9) | 9 (39) | 10 (43) | 3.2 |

| Monthly feedback emails | 1 (4) | 3 (13) | 10 (43) | 9 (39) | 3.2 |

| Posters | 13 (57) | 6 (26) | 4 (17) | 0 (0) | 1.6 |

| Clinical care guidelines | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 15 (65) | 6 (26) | 3.1 |

| Changes in Prescriptions: hyperlink to clinical care guidelines | 5 (22) | 2 (9) | 10 (43) | 6 (26) | 2.7 |

| Changes in Prescriptions: help text | 4 (17) | 1 (4) | 8 (35) | 10 (43) | 3.0 |

| Changes in Prescriptions: default buttons for antibiotic duration | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 5 (22) | 16 (70) | 3.5 |

|

| |||||

| Factors that influence the duration of therapy prescribed | Not at all | A little | Some | A lot | |

|

| |||||

| Pressure from parents to prescribe a longer course | 23 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Pressure from peers to prescribe a longer course | 21 (91) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.1 |

| Fear of caregiver dissatisfaction with a shorter course | 20 (87) | 2 (9) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.2 |

| Fear of treatment failure with a shorter course | 7 (30) | 12 (52) | 3 (13) | 1 (4) | 1.9 |

| Difficulty ordering a shorter course in Epic | 19 (83) | 3 (13) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.2 |

| More severe pain | 19 (83) | 3 (13) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.2 |

| Presence of fever | 18 (78) | 4 (17) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.3 |

| Bilateral, rather than unilateral, infection | 16 (70) | 2 (9) | 5 (22) | 0 (0) | 1.5 |

| History of recurrent infections | 4 (17) | 7 (30) | 8 (35) | 4 (17) | 2.5 |

| Recent antibiotic use | 4 (17) | 10 (43) | 6 (26) | 3 (13) | 2.3 |

| Younger age (2–5 years) | 15 (65) | 5 (22) | 3 (13) | 0 (0) | 1.5 |

|

| |||||

| Likelihood of providers using each prescribing type | Very unlikely | Somewhat unlikely | Somewhat likely | Very likely | |

|

| |||||

| Prescribe a 5-day duration of antibiotics | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (13) | 20 (87) | 3.9 |

| Prescribe a safety-net (delayed) antibiotic | 0 (0) | 3 (13) | 13 (57) | 7 (30) | 3.2 |

| Recommend 48–72 hours of observation without an antibiotic | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 15 (65) | 7 (30) | 3.3 |

Table 6; online:

Modified Clinical Sustainable Assessment Tool Questions and Score

| Domain | Question | Not at all (1) | To little or no extent (2) | To some extent (3) | To a great extent (4) | Total | Score (max=4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engaged Staff and Leadership | Clinical champions of the intervention are recognized and respected | 1 | 1 | 8 | 13 | 23 | 3.4 |

| Engaged Stakeholders | The intervention has buy-in from all team members | 0 | 0 | 6 | 17 | 23 | 3.7 |

| Organizational Readiness | The intervention fits in well with the culture of the team | 0 | 0 | 8 | 15 | 23 | 3.7 |

| Workflow Integration | The intervention integrates well with established clinical practices | 0 | 0 | 5 | 18 | 23 | 3.8 |

| Implementation and Training | The reason for the intervention is clearly communicated to and understood by the clinical care team | 0 | 0 | 5 | 18 | 23 | 3.8 |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | Intervention monitoring, evaluation, and outcomes data are routinely reported to the clinical care team | 0 | 1 | 6 | 16 | 23 | 3.7 |

| Outcomes & Effectiveness | The intervention is evidence-based | 0 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 23 | 3.8 |

| The intervention is associated with improvement in patient outcomes that are clinically meaningful | 0 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 23 | ||

| Total Score (max 4) | 3.7 | ||||||

Balance Measures:

Treatment failure and recurrence rates were compared between the pre-and post-intervention periods using Fisher exact tests. Treatment failure was defined as needing another antibiotic (same or different) between 3–14 days after the initial prescription for AOM, whereas recurrence was defined as needing a new antibiotic between 15–30 days after the initial prescription for AOM.(4) Significance was defined as alpha=0.05 using two-tailed tests.

The project was reviewed by the Quality Improvement Committee of DH, which is authorized by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board at the University of Colorado, Denver, and the DH Ethics Committee and was determined not to be human subjects research.

Results:

The bundled intervention was implemented in 3 pediatric clinics that included 33 pediatric providers (8 advanced practice providers and 25 physicians). Of the 33 providers included, 2 left the clinic after month 5 of the intervention; prescribing data from these providers was included in the analysis because they had received nearly all intervention components. The 6 family medicine practices that received the EHR-only intervention and served as a comparator group included 122 providers (32 advanced practice providers and 90 physicians, none left the clinic during the intervention). Features of eligible patients treated for AOM and included in the analysis are shown in Table 1.

Primary Outcome:

In total, 1,017 encounters for AOM met the criteria to be included in the analysis (Table 1), 503 that occurred in clinics where the bundled intervention occurred and 514 of which occurred in clinics that only received changes to the EHR. In the EHR-only clinics, there were significant differences between pre- and post-intervention patient populations when stratified by race and ethnicity. As expected, the majority of patients were racial or ethnic minorities and had public insurance.

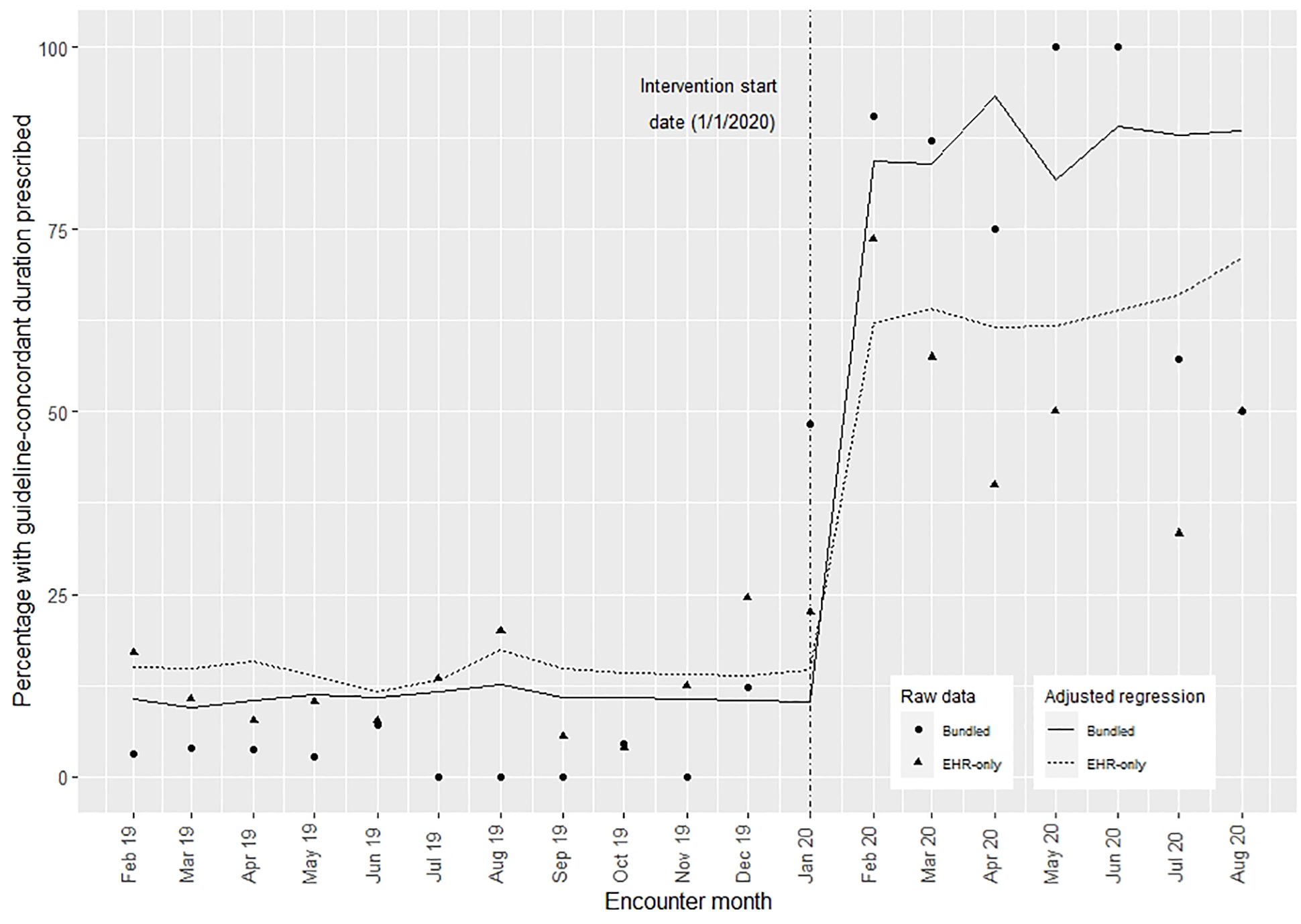

In the unadjusted difference-in-differences model (Table 7), guideline-concordant prescribing rates increased from 10.6% to 85.2% (difference=74.6%) in clinics that received the bundled intervention; whereas guideline-concordant prescribing rates increased from 14.4% to 63.8% (difference =49.4%) in the clinics that received the EHR-only intervention. The unadjusted difference-in-differences estimator attributed the bundled intervention with an additional improvement of 25.3% (p<0.01) compared with the EHR-only intervention. In the adjusted differences-in-differences regression (Table 7) using inverse probability weights and controlling for covariates, we estimated that the bundled intervention improved guideline-concordant prescribing by 26.4% (p<0.01) compared with EHR-only intervention (Table 8; available at www.jpeds.com). Figure 5 shows the raw data overlaid with the estimated rates based on the regression model. A notable decrease in the number of patients included per month was evident after emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 3).

Table 7:

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of primary outcome measure (5-day duration of therapy) for each intervention

| Intervention | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | Difference | Unadjusted DiDa Estimate | P-value | Adjusted DiDb Estimate | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| EHR-only | 59/409 (14.4%) | 67/105 (63.8%) | 49.4% | 25.3% | <0.01 | 26.4% | <0.01 |

| Bundled | 41/388 (10.6%) | 98/115 (85.2%) | 74.6% | ||||

Difference in Differences Analysis

Adjusted difference-in-differences regression estimates and confidence intervals shown in Supplementary Table

Table 8; online:

Adjusted difference-in-differences regression estimates

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald 95% Confidence Limits | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 0.481 | 0.039 | 0.406 | 0.556 | <.0001 |

| Intervention | −0.044 | 0.025 | −0.092 | 0.005 | 0.078 |

| Time*Intervention | 0.264 | 0.053 | 0.160 | 0.369 | <.0001 |

| Age | 0.012 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.018 | <.0001 |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 0.050 | 0.049 | −0.046 | 0.146 | 0.308 |

| White | 0.014 | 0.036 | −0.056 | 0.084 | 0.691 |

| Other (ref) | |||||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.015 | 0.029 | −0.043 | 0.072 | 0.614 |

| Insurance | |||||

| Commercial | −0.059 | 0.087 | −0.228 | 0.111 | 0.500 |

| Public | −0.030 | 0.080 | −0.187 | 0.127 | 0.706 |

| Uninsured | −0.119 | 0.126 | −0.366 | 0.127 | 0.344 |

| Other (ref) | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | −0.018 | 0.022 | −0.061 | 0.025 | 0.407 |

Figure 5:

Proportion of patients prescribed a guideline-concordant duration of antibiotics in the pre- and post- intervention periods for each intervention.

Implementation Outcomes:

Formative evaluations were used to adapt the intervention components to meet the needs of the clinics. These adaptations are shown in Table 9 (available at www.jpeds.com). Of the 31 providers still working at one of the clinics at the end of the intervention period, 31 (100%) read at least one audit and feedback report, 28 (90%) read ≥50% of audit and feedback reports and 13 (42%) read all audit and feedback reports. Small group education sessions were attended by 31 of 33 (94%) of providers in the bundled intervention group and the Pediatric Grand Rounds education session was attended by 33 of 33 (100%) of providers. Of the participating physicians, 20 of 26 (77%) met criteria for ABP Part 4 MOC; 5 of 5 (100%) APPs also met criteria, though they were not eligible for MOC credit.

Table 9; online:

Intervention Adaptations Made to the Intervention After Formative Evaluations

| Adaptation |

|---|

| Provider names shown on audit and feedback reports to improve transparency |

| Refreshments offered at education sessions to improve attendance |

| Inclusions of amoxicillin-clavulanate & cefdinir in prescription changes |

| Prescription “favorites” in EPIC reset with new changes |

| Audit and feedback reports were included in the email text rather than as pdf. |

| American Board of Pediatrics Part 4 Maintenance of Certification was offered to providers in the bundled intervention group |

Post-implementation surveys were completed by 23 of 31 (75%) of providers (20 physicians and 3 APPs (Table 5). Of the 23 respondents, 20 (87%) reported they were very likely to prescribe a 5-day duration for uncomplicated AOM in a child 2 years or older and 3 (13%) were somewhat likely to prescribe a 5-day duration. EHR changes to the quick select buttons for duration were felt to be the most helpful bundle component (70% very helpful, 21% moderately helpful), followed by the education session at Grand Rounds (57% very helpful, 34% moderately helpful), and the direct link to the clinical care guidelines within the prescription field (26% very helpful, 65% moderately helpful). Posters were the least helpful component, and over half of providers (56%) were not aware of the posters. A history of recurrent infections and recent antibiotic use were the factors most likely to influence providers to prescribe a longer course of antibiotics. More providers reported they were very likely to prescribe a shorter course of antibiotics (20 of 23, 87%) compared with prescribing a safety-net (delayed) antibiotic (7 of 23, 30%) or recommending observation (7 of 23, 30%).

The modified CSAT was completed by 23 individuals including 3 APPs, 17 physicians, and 3 providers who serve as clinic administrators. The program was found to have a sustainability score of 3.4 (max=4) or higher in all 7 domains and a total sustainability score of 3.7 (Table 6).

Balance Measures:

Treatment failure and recurrence were uncommon (failure <2%; recurrence <3%) and did not differ significantly between the pre- and post-intervention periods for either intervention (Table 10).

Table 10:

Fisher exact test results for balance measures

| Bundled Intervention | EHRa-only Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Pre-intervention N (%) N=388 |

Post-intervention N (%) N=115 |

P-valueb | Pre-intervention N (%) N=409 |

Post-intervention N (%) N=105 |

P-valueb | |

|

| ||||||

| Failure | 4 (1.0) | 2 (1.7) | 0.62 | 5 (1.2) | 2 (1.9) | 0.64 |

| Recurrence | 5 (1.3) | 3 (2.6) | 0.18 | 6 (1.5) | 1 (0.9) | 1.0 |

Electronic health record

Fisher’s exact test

Discussion:

In this quality improvement program both a bundled and EHR-only antimicrobial stewardship intervention significantly increased prescribing of institutional guideline-concordant durations of antibiotics for children 2 and older with uncomplicated AOM. The bundled intervention resulted in a greater improvement in guideline-concordant durations prescribed compared with the EHR-only intervention, though it is unclear if this was from difference in implementation sites (pediatrics or family medicine) or the specific intervention components. Treatment failure and recurrence rates were uncommon and did not increase with either intervention.

Historically, antimicrobial stewardship interventions for AOM have focused on reducing broad-spectrum antibiotic use or improving rates of delayed antibiotic prescribing.(15, 16) For practices with high use of overly broad-spectrum antibiotics, focusing on first line antibiotic selection is important. However, at institutions, including DH, where providers already have a high rate of first-line antibiotic selection, a complementary strategy to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use through promoting use of the shortest effective antibiotic course is essential. In this study, providers indicated they were more likely to prescribe a shorter duration of antibiotics rather than a delayed antibiotic or use observation. Providers commented that there were fewer concerns regarding loss to follow up, time spent educating families, and parent satisfaction with prescription of a shorter antibiotic course than with observation or delayed antibiotic prescribing. Thus, in addition to advocating for observation and delayed prescribing, focusing on duration of antibiotic therapy is an important and potentially effective mechanism to help reduce antibiotic exposure.

In the era of progressive antimicrobial resistance, novel strategies that are effective, easy to implement, and economical are needed to promote broad-scale stewardship. Though bundled interventions have been shown to be effective here and in other studies, they may not be feasible for small to mid-sized practices or those with resource limitations. In such settings, EHR changes to prescriptions fields could be an economical, effective alternative. Importantly, the bundled intervention presented here was also designed to be inexpensive and require minimal time resources. Education sessions could be presented virtually and recorded for providers. By automating audit and feedback reports using OASIS© external statistical programming, rather than an EHR platform, we were able to set up reports once and the system automatically updated them, emailed them to providers monthly, and allowed us to track who read reports for the remainder of the project. The OASIS code can also be freely shared between organizations and is easily modified.(21) The estimated time for the initial OASIS set-up for this project with a data analyst comfortable with statistical software and accessing the EHR data warehouse is 3–5 hours. Although the current OASIS code is written for EPIC (Verona, WI), the code could be modified and used for any EHR that utilizes a data warehouse (eg, Cerner, North Kansas City, MO, etc.). Finally, setting up an ABP MOC project is an inexpensive way to encourage provider participation.

The bundled intervention had high provider engagement and fidelity. Most providers read audit and feedback reports, participated in education sessions, and utilized EHR tools. Though this project was not designed to assess differences in the fidelity of the intervention or effectiveness of the intervention by provider type, there were no notable differences between APPs or providers. By engaging patients, providers, and administrative stakeholders prior to the intervention we were able to adapt the program to meet the unique needs of our organization. Though a long-term evaluation of sustainability is needed, the bundled intervention received a high CSAT sustainability score in all domains at its conclusion suggesting the intervention is likely sustainable and may provide a foundation for other antimicrobial stewardship interventions.

This quality improvement evaluation had several limitations. First, given that the interventions took place within a single healthcare system, the results may not be generalizable to other organizations, but may serve as models for implementing stewardship interventions in other settings. The population served by DH is also representative of the 28 million patients served by urban FQHCs annually.(20) Second, because the bundled intervention took place exclusively in pediatric clinics and the EHR-only intervention was analyzed only in family medicine clinics, we were not able to directly evaluate the effectiveness of each intervention in each specialty. We also could not delineate if the observed improvement in prescribing resulted from clinic-specific factors related to how providers received each intervention or due to the actual interventions. A cluster randomized comparative effectiveness trial would provide a more robust direct comparison. Third, we were not able to evaluate for antibiotics prescribed for treatment failure or recurrence outside of the DH system, however, most DH patients receive care predominantly from DH including emergency and urgent care. Fourth, COVID-19 emerged mid-way through the intervention which reduced the number of patients presenting for AOM. An apparent decrease in the effectiveness of the bundled intervention occurred during July-August 2020, however, this likely reflects random variation in the setting of a low number of patients included these months as a result of AOM seasonality and enhanced infection prevention measures (hand washing, mask use, daycare closures etc.) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients treated during the pandemic may also have had higher severity of illness and providers may have been more likely to prescribe antibiotics than prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, these changes would have lessened the impact of the intervention from providers prescribing longer courses of antibiotics rather than increase the intervention’s effectiveness. Because our primary objective was to evaluate duration of antibiotics rather than appropriate diagnosis of AOM, prescriptions for AOM prescribed via telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic were included in the analysis. This was a small number of prescriptions and the proportion of prescribing for short vs. long courses did not differ between telemedicine and in-person visits. Finally, though the study assessed sustainability using the CSAT score, we were not able to evaluate the longer-term sustainability of the intervention or changes in prescribing due to the short study duration. The strengths of this intervention included the ability to directly compare two simple, low cost interventions to reduce antibiotic prescribing for AOM in a diverse setting and the evaluation of implementation outcomes including the fidelity to the intervention and potential for sustainability. We were also able to develop a system to completely automate audit and feedback reporting, which is a resource that may be shared with other organizations.

In conclusion, interventions to increase adherence to recommended shorter antibiotic durations should be considered essential components of antibiotic stewardship programs. A simple, low-cost, bundled intervention was more effective in improving institutional guideline-concordant antibiotic durations as compared with only EHR changes; it remains to be determined if the difference in effectiveness is from intervention components versus sites of intervention. Though a bundled approach is likely optimal for improving prescribing, even EHR changes alone can have a positive impact on prescribing. Because AOM is the most common indication for antibiotics in children practices should strongly consider implementing interventions to improve prescribing for AOM as overprescribing has implications for child health. This bundle appears to be a feasible, promising approach to reduce duration of prescribed antibiotics and warrants testing in a larger clinical trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Denver Health Pilot Grant program ( PI: H.F.). H.F. received salary support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HD099925. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations:

- ABP

American Board of Pediatrics

- AOM

Acute Otitis Media

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CSAT

Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

- FQHC

Federally Qualified Health Clinic

- ICD

International Classification of Disease

- MOC

Maintenance of Certification

- OASIS

Outpatient Automated Stewardship Information System

- RRR

Relative Risk Ratio

Footnotes

OASIS may be licensed at no cost by completing a web-based license or by contacting the author or co-authors (Holly Frost).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Shah SS. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1053–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaur R, Morris M, Pichichero ME. Epidemiology of Acute Otitis Media in the Postpneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Era. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerber JS, Ross RK, Bryan M, Localio AR, Szymczak JE, Wasserman R, et al. Association of Broad- vs Narrow-Spectrum Antibiotics With Treatment Failure, Adverse Events, and Quality of Life in Children With Acute Respiratory Tract Infections. Jama. 2017;318(23):2325–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad OF, Akbar A. Microbiome, antibiotics and irritable bowel syndrome. British medical bulletin. 2016;120(1):91–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton DB, Scott FI, Haynes K, Putt ME, Rose CD, Lewis JD, et al. Antibiotic Exposure and Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Case-Control Study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e333–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, Pant C, Rolston DD, Sferra TJ, et al. Community-associated Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotics: a meta-analysis. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2013;68(9):1951–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong S, Amand C, Kieffer A, Kyaw MH. Trends in healthcare utilization and costs associated with acute otitis media in the United States during 2008–2014. BMC health services research. 2018;18(1):318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The White House. National action plan for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. 2015. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/national_action_plan_for_combating_antibotic-resistant_bacteria.pdf.

- 10.Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports. 2016;65(6):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozyrskyj A, Klassen TP, Moffatt M, Harvey K. Short-course antibiotics for acute otitis media. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010;2010(9):Cd001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, Ganiats TG, Hoberman A, Jackson MA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e964–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young HL, Shihadeh KC, Skinner AA, Knepper BC, Sankoff J, Voros J, et al. Implementation of an institution-specific antimicrobial stewardship smartphone application. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2018;39(8):986–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frost HM, Becker LF, Knepper BC, Shihadeh KC, Jenkins TC. Antibiotic Prescribing Patterns for Acute Otitis Media for Children 2 Years and Older. The Journal of pediatrics. 2020;220:109–15.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frost HM, Andersen LM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Norlin C, Czaja CA. Sustaining outpatient antimicrobial stewardship: Do we need to think further outside the box? Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2020;41(3):382–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, Localio AR, Grundmeier RW, Bell LM, et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. Jama. 2013;309(22):2345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins TC, Hulett T, Knepper BC, Shihadeh KC, Meyer MJ, Barber GR, et al. A Statewide Antibiotic Stewardship Collaborative to Improve the Diagnosis and Treatment of Urinary Tract and Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018;67(10):1550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuler CL, Courter JD, Conneely SE, Frost MA, Sherenian MG, Shah SS, et al. Decreasing Duration of Antibiotic Prescribing for Uncomplicated Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20151223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denver Health and Hospital Authority. Report To The City 2018. Denver, CO: Denver Health; 2018. [Available from: https://www.denverhealth.org/-/media/files/about/annual-reports/gr1902-07-reporttothecity-2018-final-web.pdf?la=en&hash=E4323D81B05197C29485D4C74A3C9466FFE42042.. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Resources and Services Administration. Denver Health & Hospital Authority Health Center Program Awardee Data; 2018. [Available from: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?q=d&bid=080060&state=CO&year=2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost HM, Munsiff SS, Lou Y, Jenkins TC. Simplifying outpatient antibiotic stewardship. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2021:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American journal of public health. 1999;89(9):1322–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DougIas A Luke SM, Kim Prewitt,, Rachel Hackett JL. The clinical sustainability assessment tool (CSAT): Assessing sustainability in clinical medicine settings. Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health; Washington D.C 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.