Abstract

Learning how to tailor Ca2+ speciation and electroactivity is of central importance to engineer next-generation battery electrolytes. Using an exemplar dual-salt electrolyte, Ca(BH4)2 + Ca(TFSI)2 in THF, this work examines how to modulate a critical parameter proposed to govern electroactivity, the BH4−/Ca2+ ratio. Introduction of a more-dissociating source of Ca2+ via Ca(TFSI)2 drives re-speciation of strongly ion-paired Ca(BH4)2, confirmed by ionic conductivity, Raman spectroscopy, and reaction microcalorimetry measurements, generating larger populations of charged species and enhancing plating currents. Ca plating is possible when [Ca(TFSI)2] < [Ca(BH4)2] and thus BH4−/Ca2+ >1, but a dramatic shut-down of plating activity occurs when [Ca(TFSI)2] > [Ca(BH4)2] (BH4−/Ca2+ <1), directly evidencing the significance of coordination-shell chemistry on plating activity. Ca(BH4)2 + TBABH4 in THF, which enables enrichment of BH4− concentrations compared to Ca2+, is also examined; ionic conductivity and plating currents also increase compared to Ca(BH4)2/THF, with the latter related in part to a decrease in solution resistance. These findings delineate future directions to modulate Ca2+ coordination towards achieving both high plating activity and reversibility.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Given concerns about low earth abundance of Li in Li-ion batteries, there is growing interest in developing a beyond-Li materials basis for rechargeable batteries.1,2 Divalent batteries based on magnesium (Mg) and calcium (Ca) have received attention due to their ~1000-fold higher concentration in the earth’s crust along with attractive theoretical metrics if Mg and Ca are used as metallic anodes. Specifically, Ca metal has low reduction potential (−2.87 V vs. SHE), high gravimetric and volumetric capacities (1337 mAh/g and 2073 mAh/cc), and suggested improved safety characteristics compared to Li.2–5 However, Ca anodes cannot be used arbitrarily in the wide range of electrolytes known to the battery community6 given high degrees of ion pairing2 and an enhanced tendency to form a solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) that is blocking to divalent Ca2+,7 a limitation that historically slowed progress in Ca battery research.

Recent years have seen growing interest in Ca electrochemistry spurred by breakthroughs in electrolyte engineering8–12 that allowed reversible Ca plating/stripping to be demonstrated. Reversibility was first reported in carbonate electrolytes containing Ca(BF4)2 salt at elevated temperatures (75-100 °C),8 while other salts such as Ca(TFSI)2 showed no activity. Room-temperature reversibility was subsequently reported by Wang et al. on Au electrodes with 1.5 M Ca(BH4)2 in tetrahydrofuran (THF),9 with the borohydride salt informed by successful parallel development in the Mg field.13 Coulombic efficiencies (CE) up to 95% and high current densities (~10 mA/cm2) were demonstrated. Two additional efforts independently reported a borate-based salt, Ca(B(Ohfip)4)2 in 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME), with good reversibility (CE = 92%) and currents reaching ~20 mA/cm2.10,11 Monocarborane Ca(CB11H12)2 salts have also been reported, which provide a fluorine-free anion with comparable performance and reversibility metrics (~20 mA/cm2, CE = 88%) in a 1:1 (v/v) THF/DME blend.12

While these efforts have focused largely on characterization of deposited Ca metal, its SEI, and its electrochemical performance, there is a broader need to understand design principles for the Ca2+ coordination environment in the electrolyte in connection to reversible plating/stripping. The relatively large ionic radius of Ca2+ and its divalence afford a larger coordination number (up to 6-9 in carbonate-based electrolytes)14,15 than Li+ and Mg2+ (coordination numbers of 3-5), which in principle increases the configurational versatility.16 However, many Ca electrolytes suffer from low salt solubilities, and high degrees of contact-ion pairing and/or viscosity increases present at high salt concentrations make this theoretical versatility difficult to exploit.17 Earlier electrolyte-focused efforts emphasized ion-pairing as a key issue to address;8 the high current density and reversibility of Ca(B(Ohfip)4)2 was rationalized based on the low charge density of the anion and thus high degree of dissociation,10,11 evidencing one successful design strategy.

Further studies have recently indicated that even in non-highly-dissociating salts, manipulation of Ca2+ speciation is possible and can in certain instances lead to dramatic modulation of electrochemical performance. Hahn et al., examining the Ca(BH4)2/THF system, showed that Ca2+ interacts strongly with BH4− anions such that unpaired Ca2+ are exceedingly unlikely in THF,16,18 similar to Mg(BH4)2/THF.13,19 Instead, the salt favors neutral Ca(BH4)2 monomers, neutral Ca2(BH4)4 dimers and/or higher-order multimers in THF to an overwhelming degree: ~90% of Ca2+ are charge-neutral at 0.1 M, leading to low ionic conductivity and electroactivity. At higher concentrations, formation of higher-energy ionic clusters — CaBH4+ and Ca(BH4)3− — becomes increasingly prevalent. The proportion of these ionic clusters is still small (<0.1 M CaBH4+ at 1.5 M)18 but sufficient to increase molar ionic conductivity by approximately an order of magnitude.16 The authors proposed that the electroactive species for Ca deposition is the cationic cluster CaBH4+, as its formation with increasing electrolyte concentration correlates with observations of increasing current densities in cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements.16,20 At present, increasing the salt concentration is the only method to generate sufficient populations of ionic species in this electrolyte, whereas increasing viscosities and/or limited solubilities at high concentrations (>1.65 M) prohibit arbitrary deployment of this strategy.

Using Ca(BH4)2/THF as a model system, this study examines how Ca plating current densities are modulated by alternative means than increasing total salt concentration. The coordination environment of Ca2+ was gradually modified at fixed total salt concentration by introduction of a second, more highly-dissociating salt, Ca(TFSI)2.17 Ca(TFSI)2 was chosen as an exemplar co-salt because it has a higher solubility limit (>2 M) in THF than Ca(BH4)2, in contrast to other possible candidates like Ca(B(Ohfip)4)2 which exhibits sparing solubility (<0.25 M) in THF.21 Previous studies in analogue Mg(BH4)2/THF electrolytes found that LiBH4 or NaBH4 additives enable high Mg plating/stripping current densities and reversibilities;13 Li+ and Na+ act as additional sites for BH4− coordination (‘BH4− absorbers’)22 helping to dissociate otherwise neutral Mg(BH4)2 and generate electrochemically active MgBH4+. In this study, we avoid introducing a foreign metal cation given the possibility for Li and Na to deposit and alloy with Ca,23 as was later found to occur in the Mg-based systems.24 Instead, we show that the second, more-dissociating Ca(TFSI)2 salt acts as an additional source of Ca2+ that allows for tuning of the BH4−/Ca2+ ratio, a key factor in promoting CaBH4+ ionic clusters at a lower overall total salt concentration (e.g., 1 M or lower). This re-speciation allows for ~2x higher ionic conductivities which in turn facilitate significantly increased current densities (~2x) upon plating. Raman spectroscopy and reaction microcalorimetry measurements illuminate preferential ion-paired states, which can be directly used to rationalize changes in electrochemical plating behavior.

Experimental Methods

Electrolyte preparation.

All Ca electrolyte preparation was conducted inside an argon glovebox (H2O content <0.1 ppm, O2 content <0.1 ppm, MBRAUN). As-received THF (anhydrous, 99.9%, Sigma Aldrich) was dried over activated 4Å molecular sieves for over 72 hours; water content was determined to be <10 ppm by KF titration. Ca(BH4)2·2THF (Sigma Aldrich) was added to THF and the solution was rested overnight. The amount of THF solvate in the salt was accounted for when preparing electrolyte. Ca(TFSI)2 (99.5%, Solvionic) was vacuum dried at 120 °C overnight in a Buchi apparatus. TBABH4 (98%, Sigma Aldrich) was used as received. The borohydride-based salts were not further dried due to their intrinsic reactivity towards water.

Electrochemical characterization.

A glass three-electrode cell (Pine Research, Low Volume Cell) was used for electrochemical measurements. The Au working electrode was 1.6 mm in diameter and surrounded by a PCTFE shroud (Pine Research, LowProfile). Freshly-prepared Ca foil reference electrodes were affixed in stainless steel holders and submerged in the electrolyte per a previous procedure.25 A Pt wire coil (Pine Research, LowProfile) was used as the counter electrode. 2032-type coin cells were assembled using a coin cell crimper (MSK-160E, MTI Corporation) inside the Ar glovebox with a crimping pressure of 0.81 tons. Whatman glass fiber separators were used for coin cell measurements. A Bio-Logic potentiostat was used for cyclic voltammetry and galvanostatic experiments. Cyclic voltammetry sweep rates were 25 mV/s, beginning at the open circuit potential and scanning to −1 and 2 V vs. the Ca reference, unless indicated otherwise. Solution resistances were determined with an electrochemical impedance spectroscopy potentiostat technique (ZIR), which was then utilized for IR-compensated cyclic voltammetry.

Raman spectroscopy.

Electrolyte samples were placed inside sealed glass tubes inside an Ar glovebox. Raman spectroscopy was performed on the sealed samples using a Renishaw Invia Reflex Raman Confocal Microscope. A 785 nm bar laser at an operating power of 100 mW was used as the excitation source with a 1200 l/mm grating and 10% at 50 cm−1 shift Rayleigh filter. Accumulations of spectra were obtained to improve the signal to noise ratio. Raman spectra were normalized to the peak at 914 cm−1 corresponding to C-C symmetric stretching of THF.20 Raman peak deconvolution was performed using a mix of Gaussian and Lorentzian band-shape contributions.

Ionic Conductivity.

Ionic conductivity measurements were performed under an Ar environment using an Oakton CON 700 benchtop meter equipped with a conductivity probe. The probe, which had a cell constant K = L/A = 1 (where L denotes the distance between the probe’s electrodes, and A denotes the effective surface area of the electrodes), was immersed in 3 mL of electrolyte until a steady reading was obtained.

Reaction microcalorimetry.

A power-compensation microcalorimeter (Thermal Hazard Technologies, Micro Reaction Calorimeter) was used for calorimetric measurements. A dry salt sample (either 0.1 M Ca(BH4)2·2THF, 0.1 M Ca(TFSI)2, or a 0.05 M/0.05 M mixture of the two) was injected into 1 mL of a liquid sample (either neat THF or a Ca electrolyte). Heat flow into/out of the liquid sample was measured over time with respect to a reference vial that contained 1 mL of the same starting solution. The liquid sample and liquid reference were prepared inside the Ar glovebox. The solid-injection plunger apparatus was filled with the dry salt sample and sealed to the liquid sample vial inside the Ar glovebox before setup within the microcalorimeter. All reaction microcalorimetric measurements were performed isothermally at 25 °C and stirred with a Teflon stir bar at 200 rpm.

Materials characterization.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on two samples: Ca foil soaked in 0.6 M Ca(BH4)2 + 0.4 M Ca(TFSI)2 in THF, and Ca electrochemically deposited onto Au foil from the same electrolyte formulation. The Ca foil was polished per a previous procedure25 and submerged in the electrolyte for three days. The Au foil was soaked in sulfuric acid for 30 minutes, rinsed with deionized water, and vacuum dried overnight. Ca deposits were then galvanostatically plated (~1 mAh/cm2, ~1 mA/cm2) in a glass cell with Au as the working electrode and Ca as the reference and counter electrode. Both samples were rinsed with THF several times and vacuum dried before transfer in an airtight vessel under Ar. XPS measurements were conducted using a nonmonochromatic Al Kα X-ray source. Spectra were calibrated by the adventitious carbon peak at 284.80 eV. High-resolution spectra were deconvoluted using a 70% Gaussian/30% Lorentzian line shape and a Shirley-type background in CasaXPS software.

Results and Discussion

The baseline electrochemical behavior of Ca(BH4)2/THF and its comparison to Ca(TFSI)2/THF are shown in Figure 1a. Consistent with prior reports,16,20 the first CV cycle of Ca plating/stripping on a Au disk working electrode at 25 mV/s is highly concentration dependent for Ca(BH4)2 (blue traces): maximum current densities increased from ~1 mA/cm2 (0.5 M) to ~11 mA/cm2 (1.5 M). The ionic conductivity of Ca(BH4)2 increased monotonically with concentration over this range and plateaued at 0.8 mS/cm at ~1.6 M (Figure 1b).5,16 The conductivity increase corresponds to increasing formation of charged ionic clusters such as CaBH4+ and Ca(BH4)3− in place of neutral ion pairs, as discussed previously by Hahn et al.16,18 In contrast, Ca(TFSI)2 does not support Ca plating in THF when used as the sole salt at concentrations up to and exceeding 1.0 M.9 The higher ionic conductivity of Ca(TFSI)2 compared to Ca(BH4)2 over the entire concentration range (Figure 1b) indicates a larger quantity of charged carriers, and thus the lack of electrochemical activity is not explained by deactivation of Ca2+ in fully neutral ion pairs in Ca(TFSI)2. The deactivating nature of Ca(TFSI)2 in certain solvent systems has been examined elsewhere; a prior study demonstrated that in Ca(TFSI)2/EC:PC at 100 °C, a thin passivation layer containing CaCO3, CaO, and CaF2 deactivates the electrode surface, preventing Ca deposition.26 Ca plating from Ca(TFSI)2/EC:PC was subsequently possible through an engineered SEI, formed either by transferring a borate-enriched SEI formed natively in a separate electrolyte26 or by incorporating SEI-modifying additives.27 The strong ion pairing tendency of Ca2+ with TFSI− in many ethers, including THF, was also recently hypothesized to promote deleterious TFSI− decomposition upon plating in a manner analogous to well-studied Mg(TFSI)2 systems,28 in which ion-pairing facilitates C-S bond scission upon exposure to the transient Mg+ radical generated during plating.29,30 However, direct evidence of activating/deactivating modes toggled by TFSI−-Ca2+ pairing have so far been difficult to obtain.

Figure 1:

Single-salt electrolytes: Ca(BH4)2 or Ca(TFSI)2 in THF. (a) 1st CV cycle of Ca(BH4)2/THF as a function of salt concentration compared to 1 M Ca(TFSI)2/THF, using a Au working electrode, Ca reference electrode, and Pt counter electrode at 25 mV/s. (b) Ionic conductivity vs. concentration at room temperature. (c) Raman spectra of Ca(TFSI)2/THF as a function of salt concentration indicating two distinct TFSI− interaction modes. (d) Distribution of coordinated vs. free TFSI−, and (e) estimated distribution of Ca(TFSI)2 vs. CaTFSI+ states as a function of Ca(TFSI)2 concentration, both obtained by deconvolution of the Raman data in (c) (see Supporting Information). (f) Schematic depicting the predominant coordination environments of Ca2+ at typical concentrations of <1.5 M for Ca(BH4)2 and Ca(TFSI)2 salts.

Raman spectroscopy as a function of Ca(TFSI)2 concentration is shown in Figure 1c. The TFSI− δsCF3 vibrational mode at 742 cm−1 has been previously assigned to uncoordinated TFSI−,31 and cation-TFSI− interactions are reported to blue-shift this peak to higher wavenumbers (~750 cm−1 here for Ca2+-TFSI− interactions).32 The Ca2+-coordinated TFSI− peak is higher in magnitude for all concentrations. Peak fitting (Figure S1) indicates that ~60-70% of all TFSI− anions are in an ion-paired state while the remainder of TFSI− are dissociated (Figure 1d). Assuming that high dissociation energy barriers prohibit formation of lone Ca2+ and that CaTFSI+ vibrational modes occur at similar wavenumbers as Ca(TFSI)2, the speciation of Ca2+ can be estimated by partitioning between CaTFSI+ (proportional to the amount of free TFSI−) and Ca(TFSI)2 neutral ion pairs as shown in Figure 1e (additional details in Figure S1). The results indicate that ~60-80% of Ca cations, depending on concentration, exist as CaTFSI+ whereas the remainder exist as neutral Ca(TFSI)2. We note that this estimate for CaTFSI+ is a lower bound; the formation of higher-order coordination clusters from hypothetical re-distribution of TFSI− among two neutral Ca(TFSI)2 structures – e.g. CaTFSI+ and Ca(TFSI)3− – would increase CaTFSI+ concentration further, although no direct evidence exists for such modes at present, thus we have omitted them from the present analysis. This distribution is summarized in the schematic in Figure 1f; whereas Ca2+ preferentially pairs with 2 BH4− ions to form neutral structures (monomers, dimers or higher-order clusters) at typical concentrations (e.g. 1 M),16 the majority species in TFSI−-based electrolytes is the singly-charged CaTFSI+.

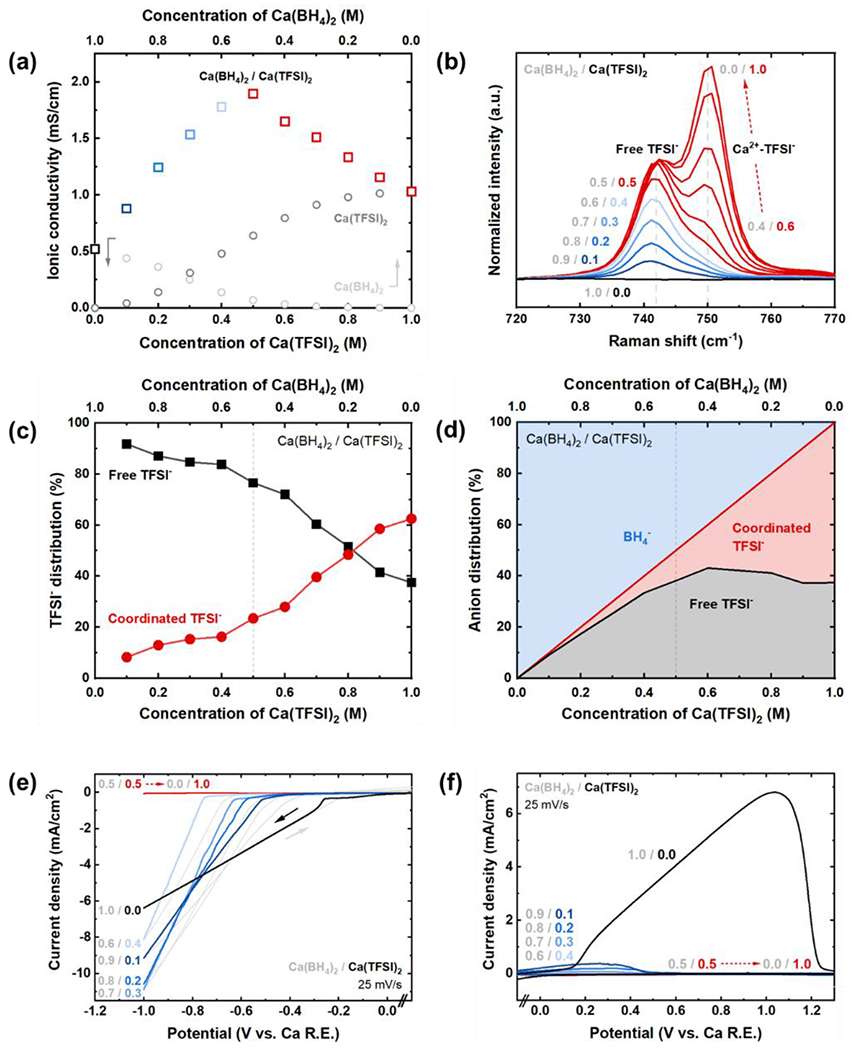

Given the distinct electrochemical activity and ion-pairing tendencies of these two salts, combining Ca(BH4)2 and Ca(TFSI)2 in THF to generate a dual-salt electrolyte provided an interesting test case to examine how Ca2+ speciation can be modulated in the presence of competitive anions. A series of such electrolytes was prepared, keeping the total salt concentration constant at 1 M while varying the relative proportions of BH4− and TFSI−. For example, ‘0.9/0.1’ corresponds to 0.9 M Ca(BH4)2 + 0.1 M Ca(TFSI)2 in THF, with resulting ion concentrations of 1 M Ca2+, 1.8 M BH4−, and 0.2 M TFSI− in THF (i.e. BH4− enriched with minor amounts of TFSI−). In contrast, ‘0.1/0.9’ denotes 0.1 M Ca(BH4)2 + 0.9 M Ca(TFSI)2 in THF, with resulting ion concentrations of 1 M Ca2+, 0.2 M BH4−, and 1.8 M TFSI− in THF (i.e. TFSI− enriched with minor amounts of BH4−). The ionic conductivity of the dual-salt electrolyte compared to single-salt Ca(BH4)2/THF or Ca(TFSI)2/THF is shown in Figure 2a. At either extremum (TFSI−-poor or BH4−-poor), the dual-salt electrolyte’s ionic conductivity approaches that of the single-salt systems at comparable 1 M concentrations, as expected. However, between these extrema, the ionic conductivity was significantly higher than that expected from an additive (linear) combination of the individual component salts at the same respective concentrations. For example, at 0.7/0.3 Ca(BH4)2/Ca(TFSI)2, 0.7 M Ca(BH4) or 0.3 M Ca(TFSI)2 each had comparable ionic conductivities (~0.3 mS/cm), but the dual-salt system exhibited an ionic conductivity of 1.5 mS/cm. This distinction became most pronounced at a ratio of 0.5/0.5 where the ionic conductivity reached a maximum of ~1.8 mS/cm. The ionic conductivity data up to this point indicate changes in speciation of the electrolyte salts at a fixed 1 M concentration to yield more charged ions in solution. The identity of these charged species cannot be distinguished by ionic conductivity measurements and possibilities include CaBH4+, Ca(BH4)3−, CaTFSI+, TFSI−, or higher-order ionic clusters, which can all contribute to ionic current. We note that formation of these ionic species are not independent but rather are strongly coupled, as discussed further below. We exclude from this list lone Ca2+ and lone BH4− given the recent evidence that it is significantly more energetically favorable for Ca2+--BH4− interactions to occur.16,18 The subsequent decrease in ionic conductivity at formulations beyond 0.5/0.5 is discussed below. Overall, the data show that competition between BH4− and TFSI− can significantly alter Ca2+ speciation.

Figure 2:

Ca(BH4)2/Ca(TFSI)2 dual-salt electrolyte in THF with a constant total salt concentration of 1 M. (a) Ionic conductivity of the dual-salt vs. single-salt electrolytes. For the dual-salt electrolytes, the top axis indicates the concentration of Ca(BH4)2 and the bottom axis indicates the concentration of Ca(TFSI)2. For the individual salts, Ca(BH4)2 and Ca(TFSI)2 concentrations are indicated by the top or bottom axis, respectively. (b) Raman spectra of the dual-salt electrolytes showing two distinct TFSI− interaction modes: free (dissociated) TFSI− at 742 cm−1 and Ca2+-coordinated TFSI− at 750 cm−1.31,32 (c) Distribution of coordinated vs. free TFSI−, and (d) distribution of total anions (i.e. coordinated TFSI−, free TFSI−, and BH4− of any configuration) as a function of Ca(TFSI)2 concentration. (e) 1st CV cycle plating behavior with the forward scan emphasized in colored traces, and (f) 1st CV cycle stripping behavior, both of dual-salt electrolytes using a Au working electrode, Ca reference electrode, and Pt counter electrode at 25 mV/s. The grayed numbers indicate concentration of Ca(BH4)2 whereas colored number indicate concentration of Ca(TFSI)2 in each electrolyte.

Raman spectroscopy was conducted on the same set of dual-salt electrolytes to elucidate the Ca2+ coordination environments by monitoring the TFSI− vibrational modes (Figure 2b). Clear differences were observed regarding the coordination environment of TFSI− in the dual-salt vs. single-salt electrolytes. For 1.0/0.0 (Ca(BH4)2 only) through 0.6/0.4, corresponding to increasing Ca(TFSI)2 fraction in the 1 M electrolyte with a BH4−/Ca2+ ratio > 1, the dissociated TFSI− peak at 742 cm−1 overwhelmingly dominates and there is only minor intensity corresponding to Ca2+-coordinated TFSI− at 750 cm−1 (~10-15% of the deconvoluted peak area, Figure S2). This indicates that a majority of the TFSI− dissociates when BH4− is present and when TFSI− are a minority species, i.e. when there are sufficient BH4− for at least one to coordinate with each Ca2+ on average. These unexpected results, leading to significant TFSI− dissociation, suggest that the coordination of BH4− by Ca2+ is energetically favorable to that of TFSI−. In fact, even minor amounts of Ca(BH4)2 added to Ca(TFSI)2/THF leads to a significant shift in the Raman spectra from coordinated TFSI− to free TFSI− (Figure S3).

The thermodynamic driving force for Ca2+ to preferentially pair with BH4− over TFSI− was directly verified using reaction microcalorimetry. In the experiments, a dry salt (either Ca(TFSI)2 or Ca(BH4)2·2THF,9 the commercially available solvate of Ca(BH4)2), was injected into a prepared solvent or electrolyte solution. Figure 3 displays the heat flow over time – which integrates to give enthalpy of solution, ΔHsol – for three such solid addition scenarios performed isothermally at 25 °C. The red area (top panel) shows the measured ΔHsol for 0.1 M Ca(TFSI)2 into neat THF as −42.3 kJ/molCa2+, while the blue area shows ΔHsol for 0.1 M Ca(BH4)2·2THF into neat THF and is equivalent to −7.3 kJ/molCa2+. Both processes are exothermic, and Ca(TFSI)2 dissolution is considerably more so, which can be attributed in part to the initial partial solvent-coordination of Ca2+ within the Ca(BH4)2 solvate. However, the larger exothermicity of Ca(TFSI)2 also reflects the tendency for Ca2+ to undergo increased cation-solvent interactions given the relatively higher dissociating tendency of TFSI− as indicated by the Raman data. Next, combined 0.05 M Ca(BH4)2·2THF + 0.05 M Ca(TFSI)2 was injected into neat THF to yield an identical final salt concentration of 0.1 M, but containing mixed anions. The resulting ΔHsol (purple area, bottom panel, −29.7 kJ/molCa2+) was considerably more exothermic than the expected value (gray area, −24.8 kJ/molCa2+) based on a linear combination of the single-salt dissolution enthalpies, indicating the occurrence of additional exothermic interactions, such as inter-Ca2+ anion transfer associated with re-speciation, when the salts are co-dissolved. 0.1 M Ca(TFSI)2 injected into 0.1 M Ca(BH4)2/THF, and vice versa, also demonstrated higher exothermicity compared to dissolution in neat THF (Figure S4) as expected, confirming the presence of more-stabilized states in solution and their path-independence.

Figure 3:

Reaction microcalorimetry of Ca(BH4)2, Ca(TFSI)2, and dual-salt injections into THF. (Top) 0.1 M Ca(BH4)2·2THF added to neat THF (blue) and 0.1 M Ca(TFSI)2 added to neat THF (red). (Bottom) 0.05 M Ca(BH4)2·2THF + 0.05 M Ca(TFSI)2 added to THF (purple) compared to the expected value based on the single-salt dissolutions from the top panel (gray). The estimated profile is a linear combination of the 0.1 M single-salt injections divided by two. The integrated area under the purple curve corresponds to the reaction enthalpy of salt dissolution, plus the enthalpy of re-speciation when mixing the two salts.

The combined ionic conductivity, Raman spectroscopy, and microcalorimetry findings are summarized in Scheme 1 for a Ca(BH4)2-dominant electrolyte, using 0.8/0.2 salt ratios as an example. When minority amounts (0.2 M) of Ca(BH4)2 are replaced by 0.2 M Ca(TFSI)2, the strong driving force for Ca2+--BH4− pairing renders most TFSI− species fully dissociated into solution. This generates increased populations of both free TFSI− and cationic CaBH4+ clusters and increases ionic conductivity. Notably, while ~5% of Ca electrolyte species were reported to exist as CaBH4+ in 1 M Ca(BH4)2/THF,18 a simple estimate based on mass conservation (and neglecting entropic considerations) estimates that tailoring the BH4−/Ca2+ ratio per Scheme 1 can generate an upper bound of ~40% CaBH4+ in 0.8/0.2 Ca(BH4)2/Ca(TFSI)2. Note that some remaining Ca2+-coordinated TFSI−, omitted from the schematic given that it is a very minor species at 0.8/0.2, may also be neutralized by BH4− coordination, which will decrease the above estimates of ionic CaBH4+. An additional dual-salt scheme for the 0.6/0.4 formulation that includes minority and neutralized species is included in Figure S5.

Scheme 1:

Modification of majority-species Ca2+ coordination environments in dual-salt electrolytes at total 1 M salt concentration, for [Ca(TFSI)2] < [Ca(BH4)2]. Here, the specific final formulation of 0.8 M Ca(BH4)2 / 0.2 M Ca(TFSI)2 in THF is given as an example for ease of illustration, corresponding to a total nominal electrolyte composition of 1 M Ca2+, 1.6 M BH4− and 0.4 M TFSI−. Only the Ca(TFSI)+ state is drawn for simplicity; however, Raman data indicate that both Ca(TFSI)+ and lesser quantities of neutral Ca(TFSI)2 are present in the single-salt case (Figure 1e), whereas only a minor amount of Ca2+-coordinated TFSI− is present in the dual-salt case. Note that some remaining Ca2+-coordinated TFSI− might be neutralized by BH4− coordination (see Fig. S5).

The indicated increase in charged ion populations up to the 0.5/0.5 formulation could be directly verified by electrochemical measurements. Figure 2e shows the first CV cycle in the Ca deposition regime onto a Au disk working electrode (Ca foil reference electrode, Pt coil counter electrode) at 25 mV/s with various Ca(BH4)2/Ca(TFSI)2 ratios for a total 1 M salt concentration. At 1.0/0.0 (entirely Ca(BH4)2, black trace), Ca plating initiated at −0.25 V vs. Ca and exhibited high ohmic resistance,25 limiting maximum current densities to approximately −6 mA/cm2 in the voltage window between 0 and −1 V vs. Ca. In contrast, a small increase in TFSI− concentration (0.9/0.1 composition; dark blue trace) led to a negative shift in the plating potential (−0.5 V vs. Ca) as well as a significant increase in ionic conductivity consistent with Figure 2a, which enabled a higher current density (approximately −9 mA/cm2) to be achieved over the same voltage window, even despite the larger plating overpotential (discussed further below). The retention of plating activity indicates that TFSI− can in fact be tolerated in the electrolyte during Ca electrodeposition as long as it remains largely dissociated, as predicted previously for Mg(TFSI)2 analogues.29 Cathodic deposition with these dual-salt electrolytes was characteristic of electroplating in Ca(BH4)2/THF9 (i.e. a nucleation overpotential during the negative sweep, and the reverse sweep indicating activity at less negative potentials, shown in further detail in Figure S6), and all cathodic current density corresponded to the formation of dark Ca deposits on the working electrode,25 shown in Figure S7 for the case of 0.9/0.1 Ca(BH4)2/Ca(TFSI)2. The trend of increasing current density with increasing TFSI− concentration continued from a composition of 0.9/0.1 to 0.7/0.3, yielding a maximum areal current of −11 mA/cm2 for the latter. The 0.6/0.4 formulation, despite the largest plating overpotential of −0.75 V vs. Ca, still exhibited a higher current density at −1 V (−8 mA/cm2) than the 1.0/0.0 formulation.

Given the changing ohmic resistances across electrolyte formulations, CVs with IR compensation were also attempted. Note that IR compensation is not straightforward in the context of Ca electrodeposition due to the changing and often severe interfacial impedance of both the Au working electrode during Ca deposition and of the Ca reference electrode, although the technique can provide some qualitative insights. In almost all cases for the dual-salt electrolytes, the required potentials between the working and counter electrode quickly exceeded the potentiostat compliance limits (Figure S8). The IR-compensated current-voltage slopes for TFSI−-containing electrolyte formulations were still found to be steeper than for the 1.0/0.0 formulation, indicating that the increasing slopes in Figure 2e reflect not only increasing ionic conductivity, but also a degree of improved plating activity. It is possible that the increased plating activity is a result of an increased concentration of electroactive CaBH4+, consistent with Scheme 1; it is also possible that the re-speciation of BH4−, and/or solvent reorganization with TFSI− present, intrinsically improves the charge transfer kinetics of Ca2+ in electroactive CaBH4+. However, it should be noted that parasitic activity corresponding to concurrent TFSI− decomposition cannot be excluded, and also may contribute to the current density increase. Further studies are needed to illuminate mechanistic factors governing the intrinsic plating kinetics and decomposition pathways in greater detail.

A substantial shift in electrolyte speciation was observed past an equimolar salt threshold of 0.5/0.5 and beyond, corresponding to Ca(TFSI)2-dominated formulations with a BH4−/Ca2+ ratio of <1. In the Raman spectra (Figure 2b), a noticeable Ca2+-coordinated TFSI− signal near 750 cm−1 emerged at these concentrations, indicating a sharp onset of Ca2+--TFSI− interactions (Figure 2c–d). For example, per Raman peak deconvolution, 16% of TFSI− anions are coordinated in the electroactive 0.6/0.4 formulation, while 28% are coordinated in the inactive 0.4/0.6 formulation. The results are consistent with the decreasing ionic conductivity (Figure 2a) past this point, signaling a gradual depletion of ionic carriers (loss of free TFSI− and/or neutralization of charged cationic species). Interestingly, this speciation transition corresponded to a rapid shutdown of Ca plating activity past the 0.5/0.5 formulation (Figure 2e) in spite of the conductivity maximum, thus it is not due to the depletion of ionic carriers. Instead, this transition is attributed to the abrupt chemical transition in Ca2+ speciation indicated by the Raman data. The driving force for this re-speciation can be understood by the high energy penalties to form fully dissociated Ca2+ in THF; in electrolytes containing fewer than 1 BH4− per Ca2+, less-preferential Ca2+--TFSI− pairing occurs to minimize free Ca2+ as shown in Scheme 2 using 0.4/0.6 Ca(BH4)2/Ca(TFSI)2 as an example. Unfortunately, the specific coordinated states cannot be further distinguished at this time, and may correspond to CaTFSI+, Ca(TFSI)2, or CaBH4TFSI. However, given that neutral (uncharged) species are less likely to participate in electroreduction, we tentatively suggest that increased presence of CaTFSI+ and concurrent loss of CaBH4+ to neutralized species account for this loss of electroactivity. These results provide direct evidence that uncoordinated TFSI− in solution does not preclude Ca deposition, while increased promotion of TFSI− into the coordination environment of Ca2+ correlates strongly with inhibited plating. This corroborates a prior hypothesis28 that the lack of electrochemical activity in the single-salt Ca(TFSI)2/THF stems from Ca2+-TFSI− interactions.

Scheme 2:

Modification of Ca2+ coordination environments upon replacement of Ca(BH4)2 by Ca(TFSI)2 at total 1 M salt concentration, for [Ca(TFSI)2] > [Ca(BH4)2]. Here, the specific final formulation of 0.4 M Ca(BH4)2 / 0.6 M Ca(TFSI)2 in THF is given as an example for ease of illustration, corresponding to a total nominal electrolyte composition of 1 M Ca2+, 0.8 M BH4− and 1.2 M TFSI−. Raman data indicate that both Ca(TFSI)+ and neutral Ca(TFSI)2 are present in the single-salt configuration. Possible TFSI−-coordinated states in the dual-salt configuration are CaTFSI+, Ca(TFSI)2, and CaBH4TFSI and are not further distinguishable by this technique.

Significantly, for all dual-salt electrolytes containing TFSI−, limited-to-no stripping behavior was observed (Figure 2f). We propose that this plating/stripping asymmetry stems from rapid chemical passivation of deposited Ca by free TFSI−, which reacts quickly outside the coordination environment of Ca2+ to inhibit subsequent oxidation. To examine this reactivity in detail, XPS measurements performed on both polished, chemically-soaked Ca foil and Ca electrodeposited on Au confirmed the formation of salt and solvent decomposition products.26,33–37 The chemically-passivated Ca contained approximately 15% Ca, 31% C, 39% O, 5% F, 8% B, and 1% S on the Ca surface, while the electrodeposited Ca contained higher percentages of F and S from TFSI− (~ 13% Ca, 35% C, 32% O, 11% F, 5% B, and 4% S), (Figure S9). Both samples contained ionic species such as CaF2 and CaCO3 as well as compounds characteristic of reacted TFSI−; additionally, the deposited Ca exhibited enhanced degrees of CxFy compounds indicative of further TFSI− fragmentation during cathodic polarization (Figure S10). This reactivity does not completely passivate the entire Au working electrode surface given the tendency of Ca to deposit inhomogeneously rather than as a continuous film under these conditions (Figure S7), in contrast to the relatively smooth, uniform layers of single-salt Ca(BH4)2/THF,9 leaving the electrode surface exposed for continued deposition on subsequent plating steps. The plating current density decreased with continued cycling (Figure S6), exacerbated where higher amounts of TFSI− were present.

It could be confirmed that chemical passivation of the Ca reference electrode upon reaction with TFSI− contributes to observed increases in apparent plating overpotentials.32 To examine this, decamethylferrocene (~10 mM) was added to each electrolyte configuration after CV cycling, and additional CVs were performed using a clean Pt working electrode to measure the potential of the Ca reference electrode, assuming minimal change in the decamethylferrocene potential with electrolyte38 (Figure S11). In general, increased concentrations of TFSI− relative to BH4− systematically led to reference electrode drift towards more positive potentials (e.g. by up to 0.22 V for 0.6/0.4 electrolyte formulations), which could partly although not entirely explain the larger required overpotentials (e.g. −0.75 V for 0.6/0.4). Thus, the higher apparent plating overpotential with TFSI− suggests both a degree of surface passivation of the Ca reference and additional nucleation barriers to deposition that likely stem from the formation of an inhibitive interface via TFSI− reduction on the working electrode surface.25 We could confirm that the positive drift in the Ca reference potential and/or surface passivation overpotentials were not obscuring electrochemical plating activity past equimolar formulations (e.g. 0.4/0.6): a CV scan was performed with an extended potential window down to −4.5 V vs. the Ca reference (Figure S12), and even at excessively low potentials, no significant cathodic current density was observed. Overall, these considerations make clear that TFSI− is not a practical salt anion for reversibility.

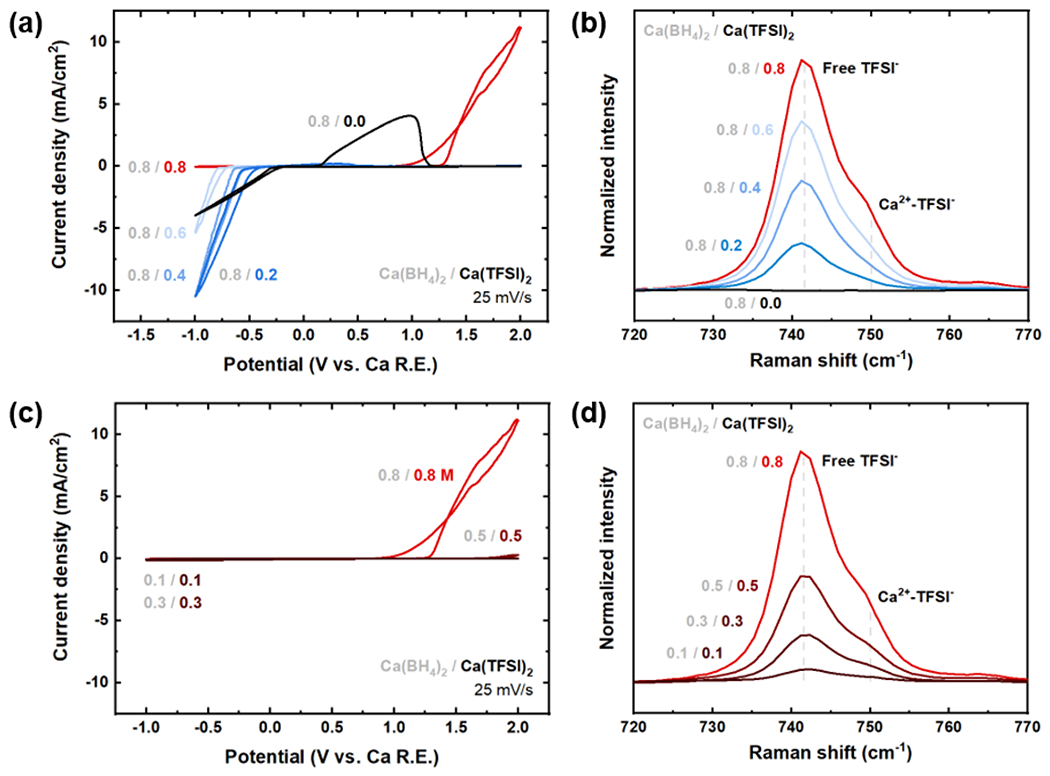

The results suggest that a critical threshold towards deactivation of Ca plating occurs at BH4−/Ca2+ < 1, which drives TFSI− increasingly into the coordination environment of Ca2+. However, increasing proportion of TFSI− in the above fixed-salt-concentration experiments corresponded to a decrease in total Ca(BH4)2 concentration, which in single-salt electrolytes leads to decreases in CaBH4+ active species and electrochemical activity (Figure 1a). To exclude decreasing Ca(BH4)2 as the reason for loss of electrochemical activity, additional experiments were performed in which a moderately high concentration of Ca(BH4)2 (0.8 M) was held constant while the concentration of Ca(TFSI)2 was varied. Consistent with the previous results, increasing the relative proportion of Ca(TFSI)2 below 0.8 M led to an increase in ionic conductivity and higher plating currents (Figure 4a) while Raman spectroscopy showed the added Ca(TFSI)2 were present mainly as dissociated TFSI−, implying formation of CaBH4+. Significant increases in apparent plating overpotential were again observed with addition of Ca(TFSI)2. Once the concentrations of BH4− and TFSI− became equal at 0.8/0.8, Ca plating activity was suppressed; this transition coincided with a marked increase of Ca2+-TFSI− interactions in the Raman data (Figure 4b). These data again indicate a tendency of TFSI− to deactivate plating once in the coordination environment of Ca2+, regardless of Ca(BH4)2 concentration, as further confirmed for equal-concentration dual salts from 0.1/0.1 M up to 0.8/0.8 M in the associated Raman data (Figure 4c–d). We note that electrolyte oxidation within 2 V vs. Ca became evident for the specific case of 0.8/0.8, and was reproducible but did not occur for other formulations; we assign this to an exacerbated degree of Ca reference drift due to the high amounts of reactive free TFSI−.

Figure 4:

Ca(BH4)2/Ca(TFSI)2 dual-salt electrolytes in THF, with either a constant Ca(BH4)2 concentration of 0.8 M (top) or a constant BH4−/TFSI− ratio (bottom). (a) and (c) 1st CV cycle plating behavior of the dual-salt electrolytes using a Au working electrode, Ca reference electrode, and Pt counter electrode at 25 mV/s. The grayed numbers denote concentration of Ca(BH4)2 whereas colored numbers denote concentration of Ca(TFSI)2 in each electrolyte. (b) and (d) Raman spectra of the dual-salt electrolytes showing two distinct TFSI− interaction modes: free (dissociated) TFSI− at 742 cm−1 and Ca2+-coordinated TFSI− at 750 cm−1.31,32

As a final test case and for the sake of completeness, an electrolyte formulation was examined in which the BH4− anion concentration was enriched, rather than depleted, compared to the nominal Ca(BH4)2 stoichiometry using TBABH4 as the second salt. Significantly, these dual-salt electrolytes allow for BH4−/Ca2+ ratios >2 to be reached without the introduction of foreign alkali cations (i.e. without using LiBH4 or NaBH4). The large ionic radius and charge delocalization of TBA+ leads to weaker association with BH4− compared to the Ca2+ cation, which in theory promotes a transfer of BH4− towards Ca2+-containing clusters beyond the stoichiometric Ca(BH4)2 distribution. Given the strong driving force to form neutral clusters,16 these additional BH4− are expected to first pair with higher-energy CaBH4+ clusters and also promote formation of Ca(BH4)3− (Figure S13). Ionic conductivity measurements (Figure 5a) showed a monotonic increase with concentration up to 2.2 mS/cm, higher than that of 1 M TBABH4/THF (1.2 mS/cm). The increased ionic conductivity with increased TBABH4 proportion – despite fewer salt ions in total (Figure S13) – confirms that significant re-speciation favoring ionic clusters occurs, though the underlying distribution of clusters is still unknown. Figure 5b shows the first CV cycle in the Ca deposition regime onto a Au disk working electrode at 25 mV/s with various Ca(BH4)2/TBABH4 ratios for a total of 1 M salt concentration. Unexpectedly and similar to the case of Ca(TFSI)2, replacing Ca(BH4)2 with minor amounts of TBABH4 led to increased plating current density for the 0.9/0.1 and 0.8/0.2 electrolytes due at least in part to their increased ionic conductivity. The cathodic current density exhibited characteristic electroplating behavior with dark Ca deposits visible after cycling (Figure S14), and Ca stripping was achieved at moderate Coulombic efficiencies for the first cycle (>80%). Parasitic TBA+ reduction7 was evident in the 25th cycle of the 0.8/0.2 formulation, as the cathodic current density no longer exhibited the characteristic electroplating behavior of Ca(BH4)2/THF (Figure S14). Further-increased TBABH4 concentrations, e.g. in a 0.7/0.3 formulation, exhibited decreasing Coulombic efficiencies as parasitic TBA+ reduction became competitive; 0.6/0.4 and 0.5/0.5 formulations showed no evidence of Ca plating/stripping, favoring TBA+ reduction entirely with no visible evidence of deposits (Figure S14) as further supported by the loss of reversibility. These dual-salt Ca(BH4)2/TBABH4 measurements present an additional example where increased current densities are achieved with an increase in ionic speciation. This finding indicates that plating in Ca(BH4)2/THF-based electrolyte systems is ohmically-limited; thus, a major contribution of TBABH4 (and Ca(TFSI)2) is to function as supporting electrolytes, though the possibility of intrinsically improved plating kinetics presents a compelling opportunity for further mechanistic study. While the results of dual-salt electrolytes clearly demonstrate the possibility to modulate CaBH4+ speciation, we are led to conclude that the more important effect at present is the added salt’s role in overcoming severe ohmic limitations, exacerbated in bulk-electrolyte cells in the absence of IR correction as is currently common to the field, which may obscure underlying activity trends including high intrinsic plating activities.

Figure 5:

Ca(BH4)2/TBABH4 dual-salt electrolyte in THF with a constant total salt concentration of 1 M. (a) Ionic conductivity of the dual-salt electrolyte; the top axis indicates the concentration of Ca(BH4)2 and the bottom axis indicates the concentration of TBABH4. (b) 1st CV cycle behavior of the dual-salt electrolytes using a Au working electrode, Ca reference electrode, and Pt counter electrode at 25 mV/s. The grayed numbers denote concentration of Ca(BH4)2 whereas colored numbers denote concentration of TBABH4 in each electrolyte

Conclusions

These results demonstrate how competition between coordinating anions can be exploited in electrolyte design strategies to alter the speciation of Ca2+ and increase the attainable plating current density. For electrolytes that are ohmically-limited such as the Ca(BH4)2/THF system, a primary factor driving increased current densities is the increase in ionic conductivity. However, we suggest that such knowledge may also be exploited in future systems where conductivity is non-limiting to obtain further gains, such as the minimization of concentration polarizations or more detailed study and tailoring of the underlying electrochemical kinetics. In the exemplar system examined herein, the passivating nature of TFSI− is detrimental to reversibility. Future dual-salt electrolytes pairing Ca(BH4)2 with more-dissociating salts that are non-reactive with Ca, and/or can withstand the cathodic polarization of Ca plating without decomposition, are compelling, provided that such salts exhibit sufficient solubility in THF or other solvents of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a NASA Space Technology Research Fellowship. The authors would like to thank Dr. Eric C. Darcy at NASA-JSC, Dr. William C. West at NASA-JPL, and Dr. John-Paul Jones at NASA-JPL for their perspectives throughout the NSTRF project. The authors would also like to thank Rui Guo for his help acquiring and processing XPS data. This work made use of the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center Shared Experimental Facilities at MIT, supported by the National Science Foundation under Award DMR-14-19807.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at [hyperlink].

Deconvolution of the Raman spectra; supplemental reaction microcalorimetry; additional schemes for the distribution of ionic species; supplemental cyclic voltammetry cycling data; IR-compensated cyclic voltammetry; galvanostatic deposition of a dual-salt electrolyte; X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; reference electrode shifts for dual-salt electrolyte formulations.

References:

- 1.Liang Y; Dong H; Aurbach D; Yao Y, Current Status and Future Directions of Multivalent Metal-ion Batteries. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 646–656. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arroyo-de Dompablo ME; Ponrouch A; Johansson P; Palacín MR, Achievements, Challenges, and Prospects of Calcium Batteries. Chem. Rev 2019, 120, 6331–6357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponrouch A; Palacin MR, On the Road Toward Calcium-based Batteries. Curr. Opin. Electrochem 2018, 9, 1–7.4 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gummow RJ; Vamvounis G; Kannan MB; He Y, Calcium-Ion Batteries: Current State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. Adv. Mater 2018, 30, 1801702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melemed AM; Khurram A; Gallant BM, Current Understanding of Nonaqueous Electrolytes for Calcium-Based Batteries. Batteries Supercaps 2020, 3, 570–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu K, Electrolytes and Interphases in Li-Ion Batteries and Beyond. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 11503–11618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aurbach D; Skaletsky R; Gofer Y, The Electrochemical Behavior of Calcium Electrodes in a Few Organic Electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc 1991, 138, 3536–3545. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponrouch A; Frontera C; Bardé F; Palacín MR, Towards a Calcium-based Rechargeable Battery. Nat. Mater 2015, 15, 169.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D; Gao X; Chen Y; Jin L; Kuss C; Bruce PG, Plating and Stripping Calcium in an Organic Electrolyte. Nat. Mater 2017, 17, 16.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shyamsunder A; Blanc LE; Assoud A; Nazar LF, Reversible Calcium Plating and Stripping at Room Temperature Using a Borate Salt. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 2271–2276. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z; Fuhr O; Fichtner M; Zhao-Karger Z, Towards Stable and Efficient Electrolytes for Room-temperature Rechargeable Calcium Batteries. Energy Environ. Sci 2019, 12, 3496–3501. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kisu K; Kim S; Shinohara T; Zhao K; Züttel A; Orimo S. i., Monocarborane Cluster as a Stable Fluorine-free Calcium Battery Electrolyte. Sci. Rep 2021, 11, 7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohtadi R; Matsui M; Arthur TS; Hwang SJ, Magnesium Borohydride: From Hydrogen Storage to Magnesium Battery. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 9780–9783.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz AK; Glusker JP; Beebe SA; Bock CW, Calcium Ion Coordination: A Comparison with That of Beryllium, Magnesium, and Zinc. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 5752–5763.15 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shakourian-Fard M; Kamath G; Taimoory SM; Trant JF, Calcium-Ion Batteries: Identifying Ideal Electrolytes for Next-Generation Energy Storage Using Computational Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 15885–15896. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn NT; Self J; Seguin TJ; Driscoll DM; Rodriguez MA; Balasubramanian M; Persson KA; Zavadil KR, The Critical Role of Configurational Flexibility in Facilitating Reversible Reactive Metal Deposition from Borohydride Solutions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 7235–7244. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forero-Saboya JD; Marchante E; Barros Neves de Araújo R; Monti D; Johansson P; Ponrouch A, Cation Solvation and Physico-Chemical Properties of Ca Battery Electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 29524–29532.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn NT; Self J; Han KS; Murugesan V; Mueller KT; Persson KA; Zavadil KR, Quantifying Species Populations in Multivalent Borohydride Electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 3644–3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arthur TS; Glans P-A; Singh N; Tutusaus O; Nie K; Liu Y-S; Mizuno F; Guo J; Alsem DH; Salmon NJ; Mohtadi R, Interfacial Insight from Operando XAS/TEM for Magnesium Metal Deposition with Borohydride Electrolytes. Chem. Mater 2017, 29, 7183–7188. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ta K; Zhang R; Shin M; Rooney RT; Neumann EK; Gewirth AA, Understanding Ca Electrodeposition and Speciation Processes in Nonaqueous Electrolytes for Next-Generation Ca-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21536–21542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielson KV; Luo J; Liu TL, Optimizing Calcium Electrolytes by Solvent Manipulation for Calcium Batteries. Batteries Supercaps 2020, 3, 766–772.22 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deetz JD; Cao F; Sun H, Exploring the Synergy of LiBH4/NaBH4 Additives with Mg(BH4)2 Electrolyte Using Density Functional Theory. J. Electrochem. Soc 2018, 165, A2451–A2457. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiao S; Jie Y; Tan Y; Li L; Han Y; Xu S; Zhao Z; Cao R; Ren X; Huang F; Lei Z; Tao G; Zhang G, Electrolyte Solvation Manipulation Enables Unprecedented Room-Temperature Calcium Metal Batteries. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59, 12689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang J; Haasch RT; Kim J; Spila T; Braun PV; Gewirth AA; Nuzzo RG, Synergetic Role of Li+ during Mg Electrodeposition/Dissolution in Borohydride Diglyme Electrolyte Solution: Voltammetric Stripping Behaviors on a Pt Microelectrode Indicative of Mg–Li Alloying and Facilitated Dissolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 2494–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melemed AM; Gallant BM, Electrochemical Signatures of Interface-Dominated Behavior in the Testing of Calcium Foil Anodes. J. Electrochem. Soc 2020, 167, 140543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forero-Saboya J; Davoisne C; Dedryvère R; Yousef I; Canepa P; Ponrouch A, Understanding the Nature of the Passivation Layer Enabling Reversible Calcium Plating. Energy Environ. Sci 2020, 13, 3423–3431. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forero-Saboya J; Bodin C; Ponrouch A, A Boron-based Electrolyte Additive for Calcium Electrodeposition. Electrochem. Commun 2021, 124, 106936.28 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hahn NT; Driscoll DM; Yu Z; Sterbinsky GE; Cheng L; Balasubramanian M; Zavadil KR, Influence of Ether Solvent and Anion Coordination on Electrochemical Behavior in Calcium Battery Electrolytes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater 2020, 3, 8437–8447. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajput NN; Qu X; Sa N; Burrell AK; Persson KA, The Coupling between Stability and Ion Pair Formation in Magnesium Electrolytes from First-Principles Quantum Mechanics and Classical Molecular Dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 3411–3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baskin A; Prendergast D, Exploration of the Detailed Conditions for Reductive Stability of Mg(TFSI)2 in Diglyme: Implications for Multivalent Electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 3583–3594. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rey I; Johansson P; Lindgren J; Lassègues JC; Grondin J; Servant L, Spectroscopic and Theoretical Study of (CF3SO2)2N− (TFSI−) and (CF3SO2)2NH (HTFSI). J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 3249–3258. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tchitchekova DS; Monti D; Johansson P; Bardé F; Randon-Vitanova A; Palacín MR; Ponrouch A, On the Reliability of Half-Cell Tests for Monovalent (Li+, Na+) and Divalent (Mg2+, Ca2+) Cation Based Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc 2017, 164, A1384–A1392. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: A Reference Book of Standard Spectra for Identification and Interpretation of XPS Data; Chastain J, Ed.; Perkin-Elmer Corporation: Eden Prairie, MN, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor JA; Lancaster GM; Rabalais JW Surface Alteration of Graphite, Graphite Monofluoride and Teflon by Interaction with Ar+ and Xe+ beams. Appl. Surf. Sci 1978, 1, 503–514. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doveren HV; Verhoeven JT XPS Spectra of Ca, Sr, Ba and their Oxides. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom 1980, 21, 265–273.36 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ni M & Ratner BD Differentiating Calcium Carbonate Polymorphs by Surface Analysis Techniques—an XPS and TOF-SIMS Study. Surf. Interface Anal 2008, 40, 1356–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seyama H & Soma M X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopic Study of Montmorillonite Containing Exchangeable Divalent Cations. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1 1984, 80, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwabi DG; Bryantsev VS; Batcho TP; Itkis DM; Thompson CV; Shao-Horn Y Experimental and Computational Analysis of the Solvent-Dependent O2/Li+-O2− Redox Couple: Standard Potentials, Coupling Strength, and Implications for Lithium–Oxygen Batteries. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 3129–3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.