Abstract

The effect of high pressure on the structure of orthorhombic Mn3(VO4)2 is investigated using in situ Raman spectroscopy and X-ray powder diffraction up to high pressures of 26.2 and 23.4 GPa, respectively. The study demonstrates a pressure-induced structural phase transition starting at 10 GPa, with the coexistence of phases in the range of 10–20 GPa. The sluggish first-order phase transition is complete by 20 GPa. Importantly, the new phase could be recovered at ambient conditions. Raman spectra of the recovered new phase indicate increased distortion and as a consequence the lowering of the local symmetry of the VO4 tetrahedra. This behavior is different from that reported for isostructural compounds Zn3(VO4)2 and Ni3(VO4)2 where both show stable structures, although almost similar anisotropic compression of the unit cell is observed. The transition observed in orthorhombic Mn3(VO4)2 could be due to the internal charge transfer between the cations, which favors the structural transition at lower pressures and the eventual recovery of the new phase even upon pressure release in comparison to other isostructural compounds. The experimental equation of state parameters obtained for orthorhombic Mn3(VO4)2 match excellently with empirically calculated values reported earlier.

Introduction

Searching novel materials with new phases/polymorphs having desired properties under different thermodynamic conditions is a topic of recent interest because of their useful technological applications and for understanding basic principles. Since vanadium shows multiple oxidation states,1 it forms different stoichiometric oxides, showing a wide range of applications.2−5 When vanadium forms oxide compounds in combination with other magnetic ions, the vacant d-orbitals in the vanadium atom serve as magnetic linking groups resulting in interesting coupling behavior.6−8

Orthovanadates of family A3(VO4)2 having Kagomé staircase structures show interesting magnetic transitions for A = Ni, Co, Mn.6−8 They have potential applications as electrodes in lithium ion batteries when A = Ni, Co, Zn.9 For A = Mg, Zn, Ni, Co, Mn, the family A3(VO4) of compounds commonly adopts an orthorhombic structure with the Cmca space group at ambient conditions.10−14 There exists another vanadate within the A3(VO4)2 family, namely, Cu3(VO4)2, which crystallizes in a triclinic structure at ambient conditions but has a high-temperature polymorph of orthorhombic structure (space group Cmca).15 Similarly, Mn3(VO4)2 is also reported to exist in a tetragonal structure (space group I4̅2d), which is a high-temperature phase (which can be stabilized at ambient temperature via quenching or substitution of Mn2+ by 2 Li+) called ht-Mn3(VO4)2 as against the thermodynamically stable low-temperature orthorhombic phase, which is commonly called lt-Mn3(VO4)2.14

There exist some structural studies on the series of compounds LixMn3–x/2(VO4)2 that report that its structure changes from tetragonal (described by space group I4̅2d) to orthorhombic structure (described by space group Cmcm) when x is above 0.4.14 Our earlier investigation of the structural stability of the tetragonal compound Li0.2Mn2.9(VO4)2 at high pressures using Raman spectroscopy and powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) revealed highly anisotropic compression of the lattice, followed by an irreversible transition to a disordered unidentified crystalline phase above 13 GPa.16

In the literature, only two members, Zn3(VO4)2 and Ni3(VO4)2, of the orthorhombic A3(VO4)2 have been studied under high pressure.17,18 Both are reported to be stable up to 15 and 23 GPa, respectively, with both exhibiting anisotropic compressibility, even though it is less pronounced than that of the tetragonal compound Li0.2Mn2.9(VO4)2.16 The triclinic form of Cu3(VO4)2 has been recently reported to decompose under pressure at a moderate pressure of 1.35 GPa to CuO and V2O5.19 As mentioned earlier, the compound Mn3(VO4)2 exists in two polymorphs, and it is interesting to study both under high pressure for possible new phases in comparison to isostructural compounds Zn3(VO4)2 and Ni3(VO4)2. Apart from the basic research interest, knowledge of high-pressure structural transitions and fundamental properties such as bulk modulus is essential for technological applications. It is reported that in this class of compounds A3(VO4)2, compressibility is decided by that of AO6 octahedra.17,18 The VO4 tetrahedra are supposed to be more rigid than the AO6 octahedra, and the bulk modulus in this family of compounds is given by an empirical formula containing average A–O distance and charge on A ion as parameters.18 Therefore, initial structural parameters such as bond lengths and octahedral distortions of AO6 play an important role in deciding the stability of the compound at high pressures. Here, we report the results of vibrational and structural investigations on lt-Mn3(VO4)2 at high pressures carried out using in situ Raman spectroscopic and powder XRD measurements up to 26.2 and 23.4 GPa, respectively. We also compare the ambient structural parameters, relating them to the Raman spectra and subsequently to the stability at high pressures in the A3(VO4)2 family of compounds with the orthorhombic (space group Cmca) structure. Furthermore, we have used Raman spectroscopy to detect the local structural disturbance induced by symmetry lowering. While initially the effect of pressure is to distort the AO6 octahedra, it affects the VO4 tetrahedra, which is observed in the Raman spectra. Perturbation/distortion in the AO6 network can lead to distortion in VO4 tetrahedra resulting in structural transitions. Some of the vanadates containing VO4 tetrahedra transform into compounds with higher coordination of vanadium under high pressure for better packing, resulting in a structural phase transition.20 Raman spectroscopy is one of the most convenient tools to study a change of coordination across transition, distortion of the polyhedral units, and lowering of their site symmetries.

Experimental Details

A polycrystalline sample of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 was synthesized by a solid-state reaction method as described in ref (14). The Raman spectra were recorded on a micro-Raman spectrometer LabRAM HR-800 Evolution using 532 nm laser of power 5 mW and resolved with a grating of 600 lines/mm, which gives a pixel coverage of 1.2 cm–1 and spectral resolution of 3 cm–1. Raman spectra could be reproduced with an accuracy better than ±0.1 cm–1. For high-pressure Raman measurements, a few grains of lt-Mn3(VO4)2, ruby (pressure marker), and a pressure-transmitting medium (16:3:1 methanol–ethanol–water mixture) were loaded inside a diamond anvil cell (Diacell B-05). The pressure calibration is performed with the ruby fluorescence method21 with error less than ±0.2 at 10 GPa and less than ± 1 GPa at 25 GPa in the present experiment as measured from the full width at half-maximum of the ruby R1 line and from its position at different locations in the sample chamber in the diamond anvil cell. The pressure-transmitting medium 16:3:1 methanol–ethanol–water mixture remains hydrostatic up to 10.5 GPa, then quasi-hydrostatic up to 20 GPa, and becomes nonhydrostatic above 20 GPa.22,23 The angle dispersive powder X-ray diffraction (ADXRD) measurements at various pressures were recorded at the Xpress beamline of Elettra Synchrotron Source, Trieste, Italy. A Mao–Bell-type diamond anvil cell was used for pressure generation, and the sample with a few grains of platinum as in situ pressure marker, along with the 16:3:1 methanol–ethanol–water mixture as a pressure-transmitting medium, was loaded inside a 100 μm hole of a stainless steel gasket. The pressure was calibrated using the equation of state of platinum with an accuracy of 0.1 GPa.24 An X-ray beam of wavelength 0.4957 Å collimated to 80 μm was used to collect the powder diffraction data on a MAR345 image plate area detector with a resolution of 100 μm × 100 μm pixel size. Typically, data were collected for an exposure time of 30 s at each pressure point. The sample-to-detector distance along with various detector orientation parameters was refined with FIT2D software25 using the diffraction pattern of CeO2. The same software was used to convert two-dimensional diffraction rings from the sample to standard one-dimensional intensity vs 2θ plots. The structural refinement of the diffraction peaks from the sample and further data analysis was performed with GSAS software.26 Initially, the background of the XRD pattern was fitted with a Chebyshev polynomial function, followed by modeling the shape of Bragg peaks with the pseudo-Voigt function. Due to the presence of texture in the patterns, the Le Bail analysis method27 available in GSAS software was used to obtain the structural details at various pressures.

Results and Discussion

Vibrational Properties at Ambient Conditions

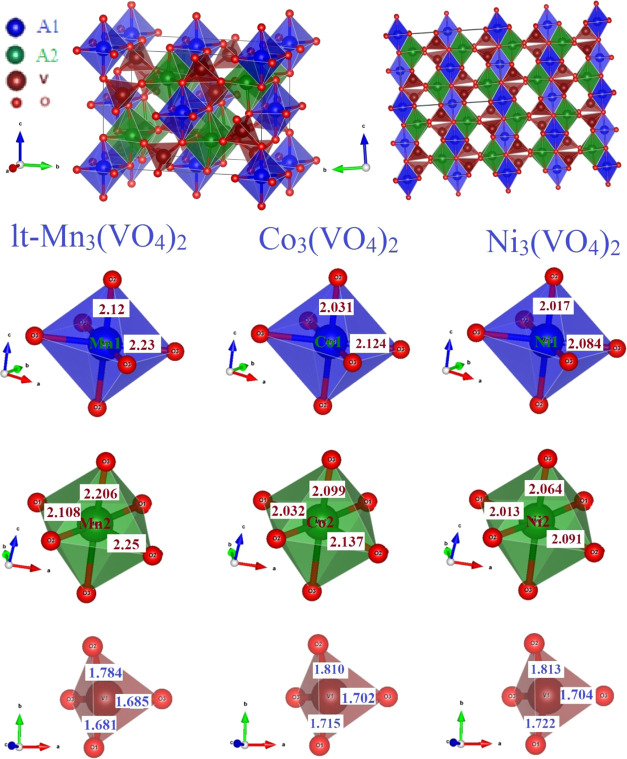

The crystal structure of A3(VO4)2 in the orthorhombic Cmca space group is depicted in Figure 1, which contains AO6 octahedra and VO4 tetrahedra in which each octahedron shares its edge with the three adjacent octahedra and forms layers perpendicular to the [010] direction, and these layers are interconnected by isolated VO4 tetrahedral units.17 The unit cell contains two formula units in which the A-atoms reside at two crystallographically distinct (A1 at 4a, A2 at 8e) Wyckoff sites, while the vanadium atoms reside at the 8f site and the oxygen atoms reside at 8f and 16g sites.14 Therefore, there are 78 zone center phonons, of which optic modes transform as Γoptic = 10Ag + 8B1g + 7B2g + 11B3g + 8Au + 12B1u + 11B2u + 8B3u. Among them, Ag, B1g, B2g, and B3g are Raman active modes; all Au modes are optically inactive; and the remaining modes are IR-active. Hence, there is a maximum of 36 symmetry-allowed Raman modes at ambient conditions for the orthorhombic Cmca structure.28

Figure 1.

Structure of orthorhombic A3(VO4)2 in two orientations.

Figure 2 represents

the Raman spectra of orthorhombic lt-Mn3(VO4)2, Co3(VO4)2, and Ni3(VO4)2 at ambient conditions. All of

the observed Raman spectra match with the reported data,16,28,29 and their assignments suggest

that the modes in the range of 500–900 cm–1 are predominantly due to the V–O stretching and are mixed

with some A–O stretching/bending modes. The

modes in the range of 200–500 cm–1 are bending

modes. The modes below 200 cm–1 are rigid motions

of VO4 tetrahedra and A–O6 octahedra. Major Raman modes of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 are assigned in accordance with our earlier polarized

Raman studies on Ni3(VO4)2,28 and, accordingly, the V–O symmetric stretching

modes (Ag-symmetry) in lt-Mn3(VO4)2 are at 645, 811, and 793 cm–1 in

the high-frequency region due to the symmetric stretching of short

and long V–O bonds (all three bond lengths are given in Figure 1 taken from the literature12,14). The asymmetries in the Raman spectra at around 686 and 783 cm–1 are the asymmetric V–O stretching modes (Bg-symmetry). Similarly, the symmetric (Ag) and asymmetric

(Bg) bending and external modes can be assigned in comparison

to that of Ni3(VO4)2. The most intense

modes in lt-Mn3(VO4)2, Co3(VO4)2, and Ni3(VO4)2 at ambient conditions appear at around 811, 815, and 826

cm–1, respectively. As shown in Table 1, which compares the reported

structural details of the three compounds, all of the three compounds

have almost similar average V–O bond lengths.12,14 It appears that the most intense symmetric stretching frequency

depends predominantly on the radius of the ion A2+ and the tetrahedral distortion, similar to what has been

reported for AV2O6.30 Accordingly, the lowest-size Ni2+-ion (0.69 Å)-containing compound has a large frequency of stretching

mode. It may be noted that the unit cell volume also increases from

Ni to Mn obeying Vegard’s law. While indicators such as elongation

and variance in angles have been used extensively in the literature

to describe the distortion in polyhedra,31 we have used the parameter distortion index calculated from bond

lengths from the literature, which is compared with Raman data in AV2O6 and tungstate double perovskites.30,32 For VO4 tetrahedra, the distortion index is calculated

from  and for MnO6 octahedra is calculated

from

and for MnO6 octahedra is calculated

from  , where d and ⟨d⟩ represent the bond length and average bond length

for the corresponding V–O/A–O bonds.

We have calculated these distortion indices using the bond lengths

reported in the literature12,14 and are given in Table 1. Figure 3 shows the variation of Raman

mode frequency of the highest-intensity V–O symmetric stretching

mode of lt-Mn3(VO4)2, Co3(VO4)2, and Ni3(VO4)2 with (a) VO4 tetrahedral distortion index (ΔTd) and (b) Shannon radius of cation A2+ (Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+). Similar

to the family of AV2O6, where

the Raman frequency corresponding to the symmetric stretching increases

with octahedral distortion of VO6 octahedra, we have found

an increase in Raman frequency with an increase in VO4 tetrahedral

distortion.

, where d and ⟨d⟩ represent the bond length and average bond length

for the corresponding V–O/A–O bonds.

We have calculated these distortion indices using the bond lengths

reported in the literature12,14 and are given in Table 1. Figure 3 shows the variation of Raman

mode frequency of the highest-intensity V–O symmetric stretching

mode of lt-Mn3(VO4)2, Co3(VO4)2, and Ni3(VO4)2 with (a) VO4 tetrahedral distortion index (ΔTd) and (b) Shannon radius of cation A2+ (Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+). Similar

to the family of AV2O6, where

the Raman frequency corresponding to the symmetric stretching increases

with octahedral distortion of VO6 octahedra, we have found

an increase in Raman frequency with an increase in VO4 tetrahedral

distortion.

Figure 2.

Raman spectra of orthorhombic lt-Mn3(VO4)2, Co3(VO4)2, and Ni3(VO4)2 at ambient conditions.

Table 1. Comparison of Various Structural Parameters of lt-Mn3(VO4)2, Co3(VO4)2, and Ni3(VO4)2 at Ambient Conditionsa.

| lt-Mn3(VO4)2 | Co3(VO4)2 | Ni3(VO4)2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ω (cm–1) | 811 | 815 | 826 |

| Shannon radii of A2+ (Å) | 0.83(h) | 0.745(h) | 0.69 |

| unit cell volume (Å3) | 623.4 | 575.5 | 555.7 |

| density (g/cm3) | 4.21 | 4.69 | 4.83 |

| V–O1 (Å) | 1.681 | 1.715 | 1.722 |

| V–O2 (Å) | 1.784 | 1.810 | 1.813 |

| V–O3 (Å) | 1.685 | 1.702 | 1.704 |

| V–O3 (Å) | 1.685 | 1.702 | 1.704 |

| ⟨V–O⟩av (Å) | 1.717 | 1.732 | 1.736 |

| ΔTd (10-4) | 6.64 | 6.92 | 6.98 |

| A1–O1 (Å) | 2.12 | 2.031 | 2.017 |

| A1–O1 (Å) | 2.12 | 2.031 | 2.017 |

| A1–O2 (Å) | 2.23 | 2.124 | 2.084 |

| A1–O2 (Å) | 2.23 | 2.124 | 2.084 |

| A1–O3 (Å) | 2.23 | 2.124 | 2.084 |

| A1–O3 (Å) | 2.23 | 2.124 | 2.084 |

| ⟨A1–O⟩av (Å) | 2.193 | 2.093 | 2.062 |

| ΔOd (10-4) | 5.59 | 4.11 | 2.42 |

| A2–O1 (Å) | 2.108 | 2.032 | 2.013 |

| A2–O1 (Å) | 2.108 | 2.032 | 2.013 |

| A2–O2 (Å) | 2.25 | 2.137 | 2.091 |

| A2–O2 (Å) | 2.25 | 2.137 | 2.091 |

| A2–O3 (Å) | 2.206 | 2.099 | 2.064 |

| A2–O3 (Å) | 2.206 | 2.099 | 2.064 |

| ⟨A2–O⟩av (Å) | 2.188 | 2.09 | 2.056 |

| ΔOd (10–4) | 7.36 | 4.65 | 2.57 |

Distortion index for VO4 tetrahedra is calculated from  and for AO6 octahedra is calculated from

and for AO6 octahedra is calculated from  , where d and

⟨d⟩ represent the bond distance and

average bond distance

for the corresponding V–O/A–O bonds.

, where d and

⟨d⟩ represent the bond distance and

average bond distance

for the corresponding V–O/A–O bonds.

Figure 3.

Variation of Raman mode frequency of the highest-intensity mode of lt-Mn3(VO4)2, Co3(VO4)2, and Ni3(VO4)2 with (a) VO4 tetrahedral distortion index (ΔTd) and (b) Shannon radius of cation A2+ (Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+).

It may be also noted from Table 1 that the octahedral distortion is larger in lt-Mn3(VO4)2 compared to the other two vanadates owing to the larger ionic radius of Mn2+. It is interesting to investigate if this distortion facilitates structural transition under pressure. Even in other vanadates such as AV2O6,30 distortion of AO6 octahedra is less with smaller ions such as Co2+ or Ni2+ as compared to that in MnV2O6. It is also remarkable that among the three vanadates being compared, lt-Mn3(VO4)2 has the lowest density and hence is more likely to show structural transitions to denser phases under pressure.

Vibrational Properties at High Pressures

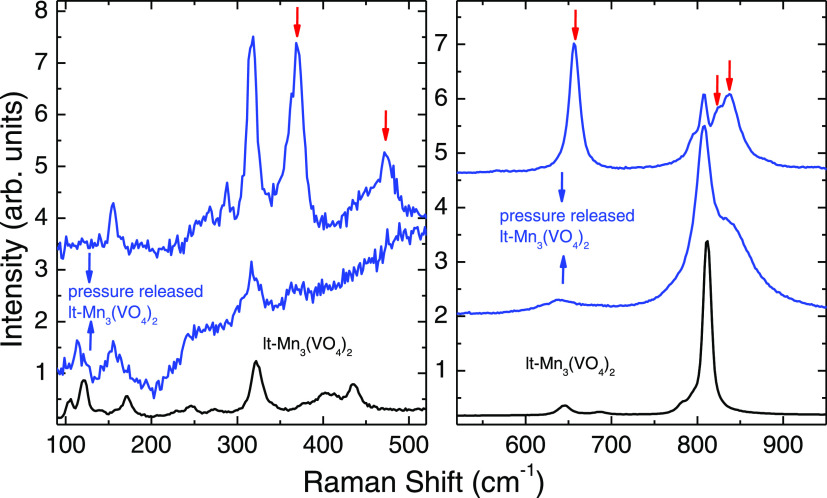

Figure 4a,b depicts the Raman spectra of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 up to 26.2 GPa in the pressure-increasing cycle at a selected pressure in the various regions. All of the modes show hardening behavior. While there is no significant change in low-frequency modes, there is a change in the intensity profile in the V–O stretching region, which is clearly seen in Figure 4b. In the high-frequency region, at a pressure of about 2.5 GPa, the intensity of the weak symmetric stretching (Ag) mode at 793 cm–1 increases and becomes strong under further pressurization, and the simultaneous decrease in the intensity of the highest-frequency mode is observed. At around 9 GPa, the intensity of the weak mode became comparable with the highest stretching mode at 811 cm–1. Above 10 GPa, this weak mode becomes the highest-intensity mode in the Raman spectra. Similar intensity exchange behavior is seen in the Raman spectra of Pr2Ti2O7 across the structural phase transition.33 Above 15 GPa, a new mode appears at around 875 cm–1 marked with an arrow in Figure 4b. This appearance of a new stretching mode could be related to distortions in VO4 tetrahedra under high pressure. Polyhedral distortions resulting in lowering of symmetry and additional peaks in Raman spectra are observed in other oxides also.34 All of the weak modes disappear, followed by the complete disappearance of the entire Raman spectra above 23 GPa. This could be related to changes in the electronic structure induced by high pressure. We pressurized the compound further up to 26.2 GPa, but we could not obtain Raman signals even at higher laser power at the highest pressure achieved. Figure 5 represents the variation of Raman mode frequencies with pressure; all of the modes show gradual hardening behavior up to 23 GPa. We have fitted the variation with a line in the two pressure regions: one below 10 GPa where the intensity exchange behavior is observed and the other above 10 GPa, which may indicate the coexistence of the two-phase region. The pressure dependencies for all of the modes are given in Table 2. We have also explored the compound in the decompression cycle from 26.2 GPa, but we could recover the Raman signal only when pressure was fully released, and the Raman spectra are different compared to ambient Raman spectra as shown in Figure 6. The presence of hysteresis suggests the transition is first order in nature; additional mode beyond the strongest symmetric stretching mode is indicative of lowering of the local symmetry of the VO4 tetrahedra. The new mode that appears beyond 15 GPa when extrapolated to ambient pressure is at 829 cm–1 and matches with the highest-frequency new mode in the pressure released data. The proposed phase transition is at pressures when the medium is quasi-hydrostatic, and we do not have experimental data under perfectly hydrostatic conditions. Therefore, the role of nonhydrostaticity in bringing about transition above 10 GPa cannot be excluded in the present investigation.

Figure 4.

Raman spectra of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 at various pressures up to 26.2 GPa in the pressure-increasing cycle (a) in full range and (b) in the V–O stretching region showing the appearance of a new peak indicated by the arrow mark.

Figure 5.

Variation of Raman mode frequencies of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 with pressure. The solid line indicates linear fitting to the data and the change of color in the solid lines demarcates the two phases.

Table 2. Raman Mode Frequency of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 and Its Pressure Dependence in the Range up to 10 GPaa.

| Raman mode frequency ωi (cm–1) |

(cm–1/GPa) (cm–1/GPa) |

isothermal mode Grüneisen parameter

|

|---|---|---|

| 102.3(1) | 0.4(1) | 0.5(1) |

| 121.9(1) | 1.2(1) | 1.14(9) |

| 148.2(5) | 1.1(2) | 0.9(1) |

| 171.8(2) | 2.7(1) | 1.82(7) |

| 242.3(2) | 1.4(1) | 0.67(5) |

| 252.2(4)b | 3.4(2) | 1.56(9) |

| 272.8(8) | 4.5(2) | 1.91(8) |

| 320.3(1) | 1.3(1) | 0.47(4) |

| 327.1(1)b | 3.9(4) | 1.4(1) |

| 376.8(2) | 2.0(1) | 0.61(3) |

| 407.2(5) | 3.5(2) | 1.00(6) |

| 435.8(4) | 2.2(1) | 0.58(3) |

| 649.9(8) | 5.5(2) | 0.98(3) |

| 690.2(3) | 4.6(2) | 0.77(3) |

| 782.8(8) | 1.35(2) | 0.20(3) |

| 796.1(3) | 2.0(2) | 0.29(3) |

| 809.2(2) | 2.8(2) | 0.40(3) |

The isothermal mode Grüneisen parameters are calculated using zero-pressure bulk modulus B0 = 116 GPa determined from high-pressure XRD.

Indicates modes that appear only at high pressures due to lifting of degeneracy.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Raman spectra of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 at ambient conditions before (black) and after recovering from 26.2 GPa from different regions (blue). New modes of the high-pressure phase are denoted by red arrow marks. Note that the highest-frequency mode (denoted by red arrows) corresponds to the new mode that appears in the high-pressure phase beyond 15 GPa in the pressure-increasing cycle.

It is clear that the compression behavior in lt-Mn3(VO4)2 is different from that reported in Li0.2Mn2.9(VO4)2 (which is isostructural with tetragonal ht-Mn3(VO4)2). In Li0.2Mn2.9(VO4)2, there appeared a broad mode at a much lower frequency (750 cm–1), indicative of higher coordination of vanadium further leading to a disordered phase. On the other hand, in orthorhombic lt-Mn3(VO4)2, the changes appear only near the symmetric stretching region more like only distortion of tetrahedra because of the change in different bond lengths.35 The intensity exchange in the stretching-mode region at around 10 GPa may indicate the beginning of a sluggish structural change. At higher pressures, from the Raman spectroscopic study, it is clear that the lattice structure of orthorhombic lt-Mn3(VO4)2 changes, which is reflected in Raman spectra as a distortion of VO4 tetrahedra, and it fully transforms into a new structure above 23 GPa. Therefore, we have also investigated the structure of orthorhombic lt-Mn3(VO4)2 using high-pressure XRD, which is discussed in the next section.

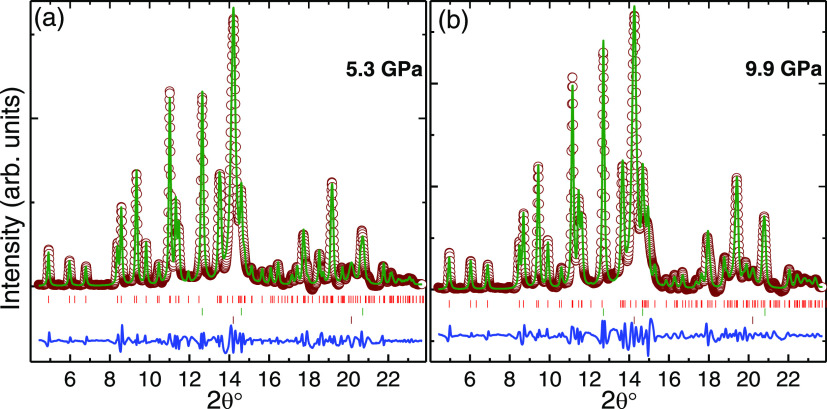

Structural Investigation at High Pressures

Figure 7 shows the evolution of X-ray diffraction patterns of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 at various pressures. A few patterns collected while unloading the pressure (marked with the letter r) are also shown in the same figure. As seen, in addition to the diffraction peaks from the sample, peaks from platinum used as an in situ pressure marker and stainless steel used as a gasket are also observed. In the first pattern collected at 0.5 GPa, all of the diffraction peaks emanating from the samples could be fitted with the ambient orthorhombic Cmca phase. No major changes were observed in the diffraction patterns collected up to 7.7 GPa, except for the shifting of diffraction peaks to higher angles due to lattice compression. All of the patterns up to 7.7 GPa could be fitted with the ambient orthorhombic phase. In Figure 8, we show the refined pattern at 5.3 and 9.9 GPa. Various residuals of the refinement, i.e., wRP and Rp, are 1.46% and 1.0% for 5.3 GPa data and 1.43% and 1.0% for 9.9 GPa, respectively. A similar kind of refinement was obtained for the data refined at other pressures. In the subsequent data collected at 9.9 GPa, there is an appearance of an extra diffraction peak at around 15° (2θ) indicated by an arrow in Figure 7. In the data collected at 10.8 GPa, there is another new broad peak at around 13.2° (2θ), suggesting the onset of a structural transition. As the pressure is increased further, till 16.2 GPa, the intensity of the emerging peaks increases while the intensity of diffraction peaks from the ambient phase reduces. This behavior indicates the coexistence of two phases till 16.2 GPa. In the data collected at 20.1 GPa, the intensity of most of the diffraction peaks from the ambient phase decreases below the detection limit of the detector and the patterns consist of broad peaks mainly from the high-pressure phase along with those from the pressure marker and the gasket. This trend continues till 23.4 GPa, the highest pressure reached in the present investigations. On pressure release, the diffraction pattern remains similar to the one observed at the highest pressure, except for the shifting of the peaks to lower angles due to lattice decompression. The observations obtained in the high-pressure XRD are consistent with the high-pressure Raman investigations discussed in the previous section. Figure 9 depicts XRD patterns of ambient and pressure-retrieved lt-Mn3(VO4)2, which confirm the structural transition and the presence of the high-pressure phase in the pressure-recovered lt-Mn3(VO4)2 whose diffraction peaks are marked with red arrows. Note that due to the addition of a few weak broad peaks, we could not refine the structure of the high-pressure phase.

Figure 7.

X-ray powder diffraction pattern of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 at various pressures. Arrows indicate the appearance of new reflections, numbers show the pressure at which the pattern is given, and r represents the releasing cycle. Pt indicates reflection for platinum, and g the reflection from the stainless steel gasket.

Figure 8.

(a, b) Fitted XRD pattern at (a) 5.3 GPa and (b) 9.9 GPa, respectively. The upper tick marks indicate the sample diffraction peaks while the middle and lower tick marks indicate diffraction peaks from Pt (pressure calibrant) and stainless steel (sample chamber), respectively. Various residuals of the refinement, i.e., wRP and Rp, are 1.46% and 1.0% for 5.3 GPa data and 1.43% and 1.0% for 9.9 GPa, respectively.

Figure 9.

Comparison of XRD patterns of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 at ambient conditions before (blue), at 0.5 GPa in the forward cycle (brown), and after recovering from 23.4 GPa (green). New peaks of the high-pressure phase are denoted by red arrow marks. Gasket and platinum peaks are also marked.

The variation of lattice parameters and the unit cell volume with

pressure obtained by refinement of X-ray diffraction data for lt-Mn3(VO4)2 is shown in Figure 10a,b. The variation of the

unit cell volume shown in Figure 10b and the variation of lattice parameters shown in Figure 10a have been fitted

with third-order Birch–Murnaghan equation of state (BM-EOS),

which is indicated by continuous curves in Figure 10a,b, and the axial compressibilities and

bulk modulus along with pressure derivative of bulk modulus have been

estimated. The fitted values of axial compressibilities are Ka = 3.1 × 10–3 GPa–1, Kb = 2.32 × 10–3 GPa–1, and Kc = 2.9 × 10–3 GPa–1. These data clearly show that the compressibility of the three axes

varies as Ka > Kc > Kb. Similar anisotropic

compression

of lattice parameters with pressure is observed for the other isostructural

compounds Zn3(VO4)2 and Ni3(VO4)2 (listed in Table 3 for easier comparison)17,18 where the authors predicted that the anisotropic behavior could

be due to the nature of the Kagomé layered crystal structure.

The obtained value of ambient pressure bulk modulus and the pressure

derivative of bulk modulus are 116(2) GPa and 2.6(5), respectively.

The bulk modulus obtained from the present experiment shows excellent

matching with the empirically estimated value of 115 GPa.18 Experimental bulk modulus is in comparison with

the other isostructural members Zn3(VO4)2 (B0 = 115 (2) GPa, B0′ = 5.1(6))17 and Ni3(VO4)2 (B0 = 139 (3) GPa, B0′ = 4.4(3)).18 We have used this value of bulk modulus for

lt-Mn3(VO4)2 (B0 = 116 GPa) to calculate the isothermal mode Grüneisen

parameters listed in Table 2 for all of the observed Raman modes using  , which scales the phonon frequency with

unit cell volume. The isothermal mode Grüneisen parameters

for all of the observed Raman modes are positive.

, which scales the phonon frequency with

unit cell volume. The isothermal mode Grüneisen parameters

for all of the observed Raman modes are positive.

Figure 10.

Variation of (a) lattice parameters with pressure. (b) Unit cell volume with pressure. Symbols show the experimental data while the solid line shows the third-order BM-EOS fitting to this data.

Table 3. Linear Compressibilities and Room-Temperature Equation of State (EOS) Parameters of Zn3(VO4)2, Ni3(VO4)2, Li0.2Mn2.9(VO4)2, and lt-Mn3(VO4)2.

| orthorhombic Zn3(VO4)217 | orthorhombic Ni3(VO4)218 | orthorhombic lt-Mn3(VO4)2 (present study) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ka (GPa–1) | 2.9(1) × 10–3 | 2.7(1) × 10–3 | 3.1 × 10–3 | ||

| Kb (GPa–1) | 1.9(1) × 10–3 | 1.79(6) × 10–3 | 2.3 × 10–3 | ||

| Kc (GPa–1) | 2.7(1) × 10–3 | 2.33(5) × 10–3 | 2.9 × 10–3 | ||

| V0 (Å3) | 585.0(4) | 585.1(1) | 555.7(2) | 623.4(2) | 624.5(5) |

| B0 (GPa) | 115(2) | 120(2) | 139(3) | 116(2) | 106(1) |

| B0′ | 5.1(6) | 4 (fixed) | 4.4 | 2.6(5) | 4 (fixed) |

A remarkable result of this study is the observation of a structural transition, which is completed by 20 GPa. A similar result was also seen in Li0.2Mn2.9(VO4)2 above 13 GPa.16 The absence of any structural transition in isostructural Zn and Ni compounds within the pressure range explored (up to 15 GPa for Zn and up to 23 GPa for Ni compound) could be due to the lesser octahedral distortion in the ambient structure in these compounds as compared to Mn compounds.

As has been described in ref (8), the band gap in Mn3(VO4)2 corresponds to a charge transfer from Mn2+ to V5+ according to

The Raman investigation reported in this article clearly indicates significant changes in the vanadium coordination and distortion of the polyhedron. According to the pressure-coordination rule,36 increase of pressure tends to increase the coordination number of the cations due to a decrease of the size of the larger, more compressible anions. Since stabilization of V4+ in tetrahedral coordination is not possible, this might also trigger such an internal charge transition, which might lead to the irreversible charge transformation observed at higher pressures for both modifications of Mn3(VO4)2. This could also be structurally supported from the behavior of Mn3+ at high pressures, for which it has been reported that the Jahn–Teller (JT) distortion of Mn3+ decreases substantially under pressure leading to the appearance of new phases in a wide variety of compounds such as in CaMn2O4,37 GdMnO3,38 Ca3Mn2[SiO4]2[O4H4],39 LaMnO3,40 etc. In CaMn2O4 and GdMnO3, the unit cell volume is reduced and the disappearance/suppression of JT distortion in MnO6 in the high-pressure phase is responsible for the structural phase transition in both.37,38 In LaMnO3, an insulator-to-metal phase transition occurred under pressure due to the change of high JT distortion to less JT distortion of MnO6 octahedra with pressure, although the crystal structure remained unchanged.39,40 In Ca3Mn2[SiO4]2[O4H4], the JT distortion of MnO4(OH)2 octahedra under pressure was suppressed totally and a gradual transition of high-spin to low-spin electronic state of Mn3+ under high pressure appeared.41

In lt-Mn3(VO4)2, the distortion in the octahedra at the Mn2+ site at ambient conditions is low compared to the above-listed compounds due to Mn being present in the d5 high-spin divalent state. Therefore, we hypothesize that the compression could decrease the band gap and favor the internal charge transfer between the cations, which would be favorable for Mn3(VO4)2 in comparison to other A3(VO4)2 compounds, and explain the transition at lower pressures observed here. A pressure-induced band-gap collapse is reported among InVO4, InNbO4, and InTaO4 across their phase transitions.42 Since the data do not allow for a detailed structural analysis to display the above-suggested model, it is of interest to investigate this possibility in more detail in a follow-up study by theoretical methods.

Conclusions

We have explored the structural stability and vibrational behavior of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 under compression using in situ Raman spectroscopy and synchrotron XRD measurements. The changes in the Raman spectra under pressure suggest that there exists a pressure-induced structural change above 20 GPa. Furthermore, Raman spectroscopy indicates the local structural distortion and symmetry lowering. Changes in XRD indicate pressure-induced crystal structural change at around 10 GPa with coexistence in the range of 10–20 GPa. The compressibility parameters of the orthorhombic phase were analyzed using the third-order Birch–Murnaghan equations of state. Equation of state of lt-Mn3(VO4)2 is obtained, and the bulk modulus obtained is comparable with those reported earlier. Anisotropic reduction is seen in the unit cell parameters that are comparable with those reported for the isostructural compounds Zn3(VO4)2 and Ni3(VO4)2.

Acknowledgments

S.K., A.B.G., and R.R. are thankful to the Department of Science and Technology, India, for the financial support to carry out the XRD measurements at Elettra Synchrotron Source with Proposal Number 20165031. The authors also thank Professor Geetha Balakrishnan, Warwick University, U.K., for the single crystals of Co3(VO4)2 used in the present study.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Zavalij P. Y.; Whittingham M. S. Structural chemistry of vanadium oxides with open frameworks. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 1999, 55, 627–663. 10.1107/S0108768199004000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weckhuysen B. M.; Keller D. E. Chemistry, spectroscopy and the role of supported vanadium oxides in heterogeneous catalysis. Catal. Today 2003, 78, 25–46. 10.1016/S0920-5861(02)00323-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mounasamy V.; Mani G. K.; Madanagurusamy S. Vanadium oxide nanostructures for chemiresistive gas and vapour sensing: a review on state of the art. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 253 10.1007/s00604-020-4182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernova N. A.; Roppolo M.; Dillon A. C.; Whittingham M. S. Layered vanadium and molybdenum oxides: batteries and electrochromics. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 2526–2552. 10.1039/b819629j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boukhalfa S.; Evanoff K.; Yushin G. Atomic layer deposition of vanadium oxide on carbon nanotubes for high-power supercapacitor electrodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6872–6879. 10.1039/c2ee21110f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawes G.; Harris A. B.; Kimura T.; Rogado N.; Cava R. J.; Aharony A.; Entin-Wohlman O.; Yildirim T.; Kenzelmann M.; Broholm C.; Ramirez A. P. Magnetically Driven Ferroelectric Order in Ni3(VO4)2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 087205 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.087205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellido N.; Martin C.; Simon C.; Maignan C. A. Coupled Negative Magnetocapacitance and Magnetic Susceptibility in a Kagome ´ Staircase-like Compound Co3V2O8. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2007, 19, 056001 10.1088/0953-8984/19/5/056001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens O.; Rohrer J.; Nenert G. Magnetic Structures of the Low Temperature Phase of Mn3(VO4)2 - Towards Understanding Magnetic Ordering Between Adjacent Kagome ´ Layers. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 156–171. 10.1039/C5DT03141A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni S.; Liu J.; Chao D.; Mai L. Vanadate-based materials for Li-ion batteries: the search for anodes for practical applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1803324 10.1002/aenm.201803324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamachari N. T.; Calvo C. Refinement of the structure of Mg3(VO4)2. Can. J. Chem. 1971, 49, 1629–1637. 10.1139/v71-266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal R.; Calvo C. Crystal Structure of α-Zn3(VO4)2. Can. J. Chem. 1971, 49, 3056–3059. 10.1139/v71-510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sauerbrei E. E.; Faggiani R.; Calvo C. Refinement of the crystal structure of Co3V2O8 and Ni3V2O8. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1973, 29, 2304–2306. 10.1107/S0567740873006552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Liu Z.; Ambrosini A.; Maignan A.; Stern C. L.; Poeppelmeier K. R.; Dravid V. P. Crystal growth, structure, and properties of manganese orthovanadate Mn3(VO4)2. Solid State Sci. 2000, 2, 99–107. 10.1016/S1293-2558(00)00104-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens O.; Haberkorn R.; Beck H. P. New phases in the system LiMnVO4-Mn3 (VO4)2. J. Solid State Chem. 2011, 184, 2640–2647. 10.1016/j.jssc.2011.07.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N. S.; Palanna O. G. Phase transitions in copper (II) orthovanadate. Bull. Mater. Sci. 1993, 16, 261–266. 10.1007/BF02745305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari S.; Garg A. B.; Clemens O.; Rao R. Compression effect on structure of the Li-stabilized high-temperature phase of Mn3(VO4)2 with composition Li0.2Mn2.9(VO4)2-Raman spectroscopic and X-ray diffraction investigations. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 870, 159418 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.159418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Anichtchenko D.; Santamaria-Perez D.; Marqueño T.; Pellicer-Porres J.; Fuertes J. R.; Ribes R.; Ibañez J.; Achary S. N.; Popescu C.; Errandonea D. Comparativestudy of the high-pressure behaviour of ZnV2O6, Zn2V2O7 and Zn3V2O8. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 837, 155505 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Anichtchenko D.; Turnbull R.; Bandiello E.; Anzellini S.; Errandonea D. High-Pressure Structural Behavior and Equation of State of Kagome Staircase Compound, Ni3V2O8. Crystals 2020, 10, 910 10.3390/cryst10100910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Anichtchenko D.; Turnbull R.; Bandiello E.; Anzellini S.; Achary S. N.; Errandonea D. Pressure-induced chemical decomposition of copper orthovanadate (α- Cu3V2O8). J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 13402–13409. 10.1039/D1TC02901K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Errandonea D. High pressure crystal structures of orthovanadates and their properties. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 040903 10.1063/5.0016323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piermarini G. J.; Block S.; Barnett J. D.; Forman R. A. Calibration of the pressure dependence of the R1 ruby fluorescence line to 195 kbar. J. Appl. Phys. 1975, 46, 2774–2780. 10.1063/1.321957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Errandonea D.; Meng Y.; Somayazulu M.; Häusermann D. Pressure-induced α→ ω transition in titanium metal: a systematic study of the effects of uniaxial stress. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 2005, 355, 116–125. 10.1016/j.physb.2004.10.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz S.; Chervin J. C.; Munsch P.; Marchand G. L. Hydrostatic limits of 11 pressure transmitting media. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 075413 10.1088/0022-3727/42/7/075413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele A.; Loubeyre P.; Mezouar M. Equations of state of six metals above 94 GPa. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 70, 094112 10.1103/PhysRevB.70.094112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley A. P.; Svensson S. O.; Hanflnd M.; Fitch A. N.; Hausermann D. Two dimensional detector software: from real detector to idealised image or two theta scan. High Pressure Res. 1996, 14, 235–248. 10.1080/08957959608201408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson A. C.; Dreele R. B. V.. Los Alamos National Laboratory Report LAUR 86-748, 2004.

- Le Bail A. Whole powder pattern decomposition methods and applications: A retrospection. Powder Diffr. 2005, 20, 316–326. 10.1154/1.2135315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari S.; Rao R.; Gupta M. K.; Mittal R.; Balakrishnan G. Symmetries of modes in Ni3V2O8: Polarized Raman spectroscopy and ab initio phonon calculations. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2019, 50, 587–594. 10.1002/jrs.5539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y. S.; Kim S. H.; Ahn J. S.; Jeong I. K. Determination of the local symmetry and the multiferroic-ferromagnetic crossover in Ni3–xCoxV2O8 by using Raman scattering spectroscopy. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2013, 62, 116–120. 10.3938/jkps.62.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peña J. P.; Bouvier P.; Hneda M.; Goujon C.; Isnard O. Raman spectra of vanadates MV2O6 (M= Mn, Co, Ni, Zn) crystallized in the non-usual columbite-type structure. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 154, 110034 10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K.; Gibbs G. V.; Ribbe P. H. Quadratic elongation: a quantitative measure of distortion in coordination polyhedra. Science 1971, 172, 567–570. 10.1126/science.172.3983.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R. L.; Heyns A. M.; Woodward P. M. Raman studies of A2MWO6 tungstate double perovskites. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 10700–10707. 10.1039/C4DT03789H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari S.; Salke N. P.; Patwe S. J.; Achary S. N.; Sinha A. K.; Sastry P. U.; Tyagi A. K.; Rao R. Structural stability and anharmonicity of Pr2Ti2O7: Raman spectroscopic and XRD studies. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 11791–11800. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S.; Zhou Q.; Huang F.; Li F.; Hu Y.; Huang L.; Li L.; Li Y.; Cui T. High pressure Raman scattering and X-ray diffraction studies of MgTa2O6. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 065324 10.1063/5.0009821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thalluri S. R. M.; Martinez-Suarez C.; Virga A.; Russo N.; Saracco G. Insights from crystal size and band gap on the catalytic activity of monoclinic BiVO4. Int. J. Chem. Eng. Appl. 2013, 4, 305. 10.7763/IJCEA.2013.V4.315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grochala W.; Hoffmann R.; Feng J.; Ashcroft N. W. The Chemical imagination at work in Very Tight Places. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3620–3642. 10.1002/anie.200602485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka T.; Uchida A.; Nakamoto Y. Structural transition of post-spinel phases CaMn2O4, CaFe2O4, and CaTi2O4 under high pressures up to 80 GPa. Am. Mineral. 2008, 93, 1874–1881. 10.2138/am.2008.2934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.; Zhang Y.; Liu J.; Li X.; Li Y.; Tang L.; Xiong L. Pressure-induced structural change in orthorhombic perovskite GdMnO3. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2012, 24, 115402 10.1088/0953-8984/24/11/115402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich A.; Winkler B.; Morgenroth W.; Perlov A.; Milman V. Pressure-induced spin collapse of octahedrally coordinated Mn3+ in the tetragonal hydrogarnethenritermieriteCa3Mn2[SiO4]2[O4H4]. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 014117 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.014117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loa I.; Adler P.; Grzechnik A.; Syassen K.; Schwarz U.; Hanfland M.; Rozenberg G.Kh.; Gorodetsky P.; Pasternak M. P. Pressure-Induced Quenching of the Jahn-Teller Distortion and Insulator-to-Metal Transition in LaMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 125501 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.125501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A. Y.; Souza-Neto N. M.; Tolentino H. C. N.; Bunau O.; Joly Y.; Grenier S.; Itié J.–P.; Flank A.-M.; Lagarde P.; Caneiro A. Bandwidth-driven nature of the pressure-induced metal state of LaMnO3. Europhys. Lett. 2011, 96, 36002 10.1209/0295-5075/96/36002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botella P.; Errandonea D.; Garg A. B.; Rodriguez-Hernandez P.; Muñoz A.; Achary S. N.; Vomiero A. High-pressure characterization of the optical and electronic properties of InVO4, InNbO4, and InTaO4. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 389 10.1007/s42452-019-0406-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]