Abstract

Objective:

This study aims to assess the prevalence of pesticide use and its occupational exposure among small-scale farmers in the Kellem Wellega Zone of western Ethiopia.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study design using a structured questionnaire was used to collect data from 249 small-scale farmers’ households through face-to-face interviews. Statistical analysis such as descriptive statistics, Chi-square test, and binary logistic regression analysis was applied, and a P-value <.05 at 95% CI was considered statistically significant.

Results:

The prevalence of pesticide use was 87.15%. About 44.2%, 40.2%, and 43.8% of the study participants were classified as having poor knowledge, poor practice, and negative attitude toward pesticide use, respectively. Thus, small-scale farmers whose age was greater than 40 years were 7.87 times more likely to be exposed to skin irritation than those whose age was less than 20 years (AOR = 7.87; 95% CI: 1.75-35.45) and skin contact (AOR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.15-0.91). Most farmers who were directly involved in agriculture were 2.22 times more likely to be exposed to the inhalation of pesticide chemicals than those involved in another activity (AOR = 2.22; 95% CI: 1.14-4.33). Based on educational level, small-scale farmers who have a primary school and above were 81% less likely to inhale pesticide chemicals than those who did not have formal education (AOR = 0.19; 95% CI: 0.09-0.41). Furthermore, low-income small-scale farmers were 2.62 times more likely to be exposed to coughing (AOR = 2.62; 95% CI: 1.25-5.51) than high-income participants. Furthermore, farmers with good knowledge were 1.79 times more likely to be exposed to skin irritation than those with poor knowledge (AOR = 1.79; 95% CI: 1.0-3.17). Farmers with poor practice were 1.85 times more likely to show coughing symptoms than those with good practice (AOR = 1.85; 95% CI: 1.08-3.2), and farmers with good practice were 48% less likely to be exposed to headache than those with poor practice (AOR = 0.52; 95% CI: 0.31-0.88).

Conclusions:

This study shows that small-scale farmers were exposed to pesticides through coughing, headache, skin irritation, inhalation, and skin contact. Low level of knowledge, poor practice, job, low income, older age, and educational level.

Keywords: Ethiopia farmer, pesticide exposure, prevalence of pesticide use

Introduction

Pesticides are any substance used to control certain forms of pests from plant or animal life. 1 On the other hand, the unprotected use of these chemicals can pose serious risks to human health and the environment. 2 The negative effect of exposure to pesticide chemicals during agricultural activities are high in farmers.3,4 According to World Health Organization (WHO) reports, more than 200 000 people are killed from pesticide poisoning each year in rural areas of developing countries. 2 Most health problems are caused by long-term exposure to pesticides. Acute symptoms such as headaches, nausea, respiratory problems, vomiting, dermatitis, leukemia, mental disorders, brain tumors, and burns are widely experienced among farmers in African countries.5-9 Cognitive, motor, sensory, and neurological deficiencies were among the symptoms of chronic exposure of pesticide users. 10

Evidence suggested that farmers’ exposure could occur accidentally in the course of mixing, loading, spraying, in direct contact with treated vegetation by spraying, during cleaning up of spraying equipment, and vapor drift from volatilized deposits of pesticides because of not using PPE.11,12 Furthermore, the consumption of contaminated food, the proximity to agricultural fields, and the occupation of agriculture were some of the possible mechanisms of exposure to pesticides by small farmers.13-16 However, the risk of exposure was based on the type, period, and route of exposure. 17 Occupational exposure to pesticides occurs commonly through inhalation, skin contact, and ingestion during the preparation of solutions and spraying conditions. 19 Thus, farmworkers are considered a primary risk group that receives a lot of exposure to pesticides. 18 Thus, farmworkers are considered a primary risk group that receives a lot of exposure to pesticides.19-21 The adverse effects of pesticides on health are increasing in developing countries due to low educational levels and unfavorable working conditions.22,23

Moreover, lack of knowledge, training, and unintentional application errors such as handling pesticides carelessly can pose serious health risks to farmers.19,24-26 Since farmers’ knowledge, practice, and attitude level of farmers on potential pesticide hazards is essential in preventing pesticide exposure.23,27 Finally, the health risks of farmworkers commonly concerned with agricultural activities were associated with occupational exposure to pesticides. To our knowledge, there are gaps in available data on the prevalence of pesticide use, knowledge and practice about pesticides, occupational exposure, and associated risks in small-scale farmers. Therefore, this study investigates the prevalence of pesticide use and its occupational exposure among small-scale farmers (SSFs) in the Kellem Wellega zone, western Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

Study site

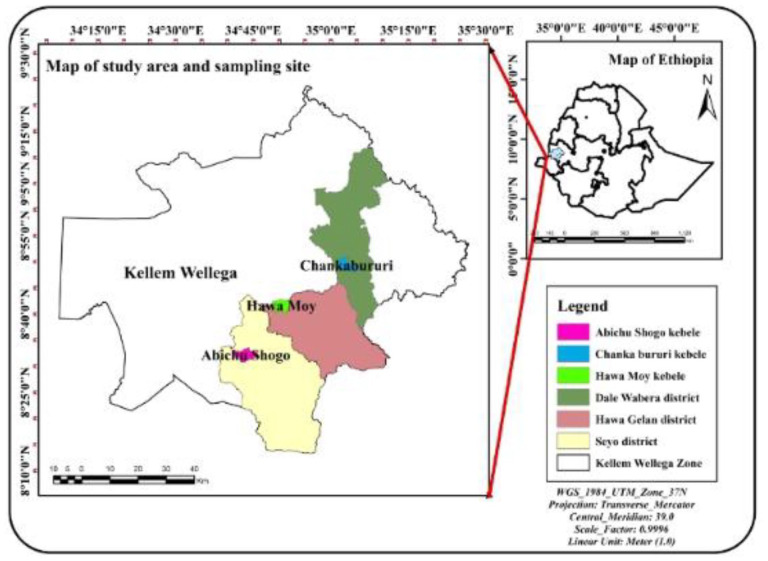

The study was carried out from May to June 2020 in the Kellem Wellega zone of the Oromia region, western Ethiopia. It was 672 km from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. In 10 districts in this region, there was a total population of 965 000. Of the total population, 51.3% were men. The total number of households in the zone was 175 000, with an average family size of 5.5. 28 The study area is located at an elevation of 1701 to 1830 m above sea level. The climatic condition alternates with prolonged summer rainfall, short rainy season, and winter dry season. The minimum and maximum annual precipitation range from 800 to 1200 mm, with a daily temperature, ranges from 15°C to 25°C. 29 This zone is well known for extensive agricultural crop production, such as coffee, maize, teff, wheat, barley, bean seed, and sorghum. Small-scale farmers carry out most of the farming activities. To increase agricultural productivity, these small-scale farmers widely use different types of pesticides to protect pests. The map of the study area was indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study area map for Sayo, Hawa Gelan, and Dale Wabara districts in the Kellem Wellega Zone of western Ethiopia in 2020.

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted that included 249 households of SSFs from May to June 2020, in western Ethiopia. Following the verbal agreement, the heads of families were interviewed face-to-face using a standardized pretested questionnaire. When the head of the household was not available, the interviewer was asked if the first adult over 18 years of age met in the household.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula for one point estimation by considering a confidence level of 95%, a margin of error of 5%, and 82% of small-scale farmers practice on pesticides 30 with a non-response rate of 10%.

By adding a 10% non-response rate to the calculated sample size, it becomes 227 + (227 × 10%) = 250, participants were designed to participate at the household level.

Operational definitions

Small-scale farmers (SFFs): Farmers who can produce crops on a small piece of land without using advanced and expensive technologies

Pesticides exposure: an exposure that may occur through occupational exposure in the case of agricultural workers in open fields and house pests

Pesticide Use: are substances or mixtures of substances that are mainly used in agriculture or in public health protection programs to protect plants from pests, weeds, and diseases

Self-reported symptoms: is single, short-term exposure effects appear immediately and are often reversible. The self-reported symptoms related to coughing, headache, vomiting, skin irritation, and abdominal pain

Exposed small-scale farmers (ESSFs): Farmers who can produce crops using pesticide chemicals on their own for at least 1 year and more in the same area

Non-Exposed Small-Scale Farmers (NESSFs): Farmers practicing organic farming and having no history of chemical exposure to pesticide chemicals for at least 1 year before the study and who did not reside near a vegetable farm were also considered 21

Kebele(s): (Amharic term standing for “neighbor hood”) is a small administrative unit in urban and rural Ethiopia comprising around 500 households per unit.

Sampling techniques

Data were collected from 3 districts: Sayo, Hawa Galan, and Dale Wabara in the Kellem Wellega zone in western Ethiopia. A 3-stage sampling was used to select small-scale farmers for this study. First, 3 districts were purposively selected from the 10 districts in the Kellem Wellega zone based on their potential for agricultural products and the number of pesticides used per year. Second, 3 kebeles, namely Abichu Shogo from the Sayo district, Hawa Moy from the Hawa Galan district, and Chanka Bururi from Dale Wabara, were purposively selected in communication with zonal agricultural experts. According to the information from experts, most small-scale farmers in the study areas used pesticides. Third, each household was randomly selected from each kebeles. Therefore, a total of 249 households study participants were selected using the lottery method, and a systematic sampling method (k = N/n = 700/249 = 2.8 = 3) was used to select the rest of the households.

Data collection

Face-to-face interviews were used to collect data using a standardized and pretested questionnaire.21,27 The questionnaire was written in English and then translated into Afan Oromo and then back into English to ensure that the translation was correct. The questions were pretested to ensure that the data collection instrument was complete. Sociodemographic factors, knowledge, practice, attitude, types of pesticides used, acute health symptoms (coughing, headache, vomiting, skin irritation, and abdominal pain) within 48 hours of exposure to pesticides and pesticide exposure routes such as ingestion, inhalation, and skin contact are included in the questionnaire. Those who had experienced this and reported 2 or more typical pesticide intoxication symptoms were considered.

Before being assigned to data collection, 3 agricultural extension workers and supervisors were trained for 2 days. Based on their reports, those participants who scored below the mean value of the responses for 10 items related to farmer knowledge about pesticide use were considered to have “poor knowledge,” while those with scores above or equal to the mean value were considered to have “good knowledge.” Participants who scored less than the mean value of responses to 10 questions related to farmer practices in pesticide use were labeled as having “poor practice,” while those who scored above or equal to the mean value were labeled as having “good practice.” The level of farmer attitude toward pesticide use was evaluated for participants who scored less than the mean value of the response for 10 questions related to attitude toward pesticide use were considered as having a “negative attitude” and those who scored more than the mean value were considered to have a “positive attitude.”

Data analysis

Data were checked and entered into SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analysis, such as mean and standard deviation for continuous data, percentage, and frequency for categorical data. Chi-square tests and logistic regression analysis were performed to determine the impact of the predicting variables (sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge, practice, attitude) on the outcome variables (coughing, headache, vomiting, skin irritation and abdominal pain, ingestion, inhalation, and skin contact). Logistic regression analysis was used to adjust the confounders. All explanatory variables associated with the outcome variable in the bivariate analysis with a P-value of less than .25 were selected and further analyzed. The odds ratio and the 95% confidence interval were used to determine the effect of potentially associated variables on the outcome variable by controlling confounders. All variables with a P-value of <.05 were considered statistically significant associations with the exposure of small-scale farmers to pesticides.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Of the 249 SSFs, the majority (88.4%) were male. The mean ages of the respondents were (40 ± 0.45) years with 85.1% of them being married and 76.3% being involved in farming activities. Additionally, approximately 39.8% of the farmers were unable to write and read (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic status of SSFs in the Kellem Wellega Zone of western Ethiopia, 2020.

| Explanatory variables | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 220 | 88.4 |

| Female | 29 | 11.6 |

| Age | ||

| ⩽20 years | 36 | 14.5 |

| 21-40 | 128 | 51.4 |

| ⩾41 | 85 | 34.1 |

| Head of the family | ||

| Yes | 176 | 70.7 |

| No | 73 | 29.3 |

| Jobs | ||

| Farming only | 190 | 76.3 |

| Other activities* | 59 | 23.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 28 | 11.3 |

| Married | 212 | 85.1 |

| Divorced or widowed | 9 | 3.6 |

| Educational level | ||

| Unable to write and read | 99 | 39.8 |

| Primary school | 111 | 44.6 |

| Secondary school and above | 39 | 15.6 |

| Total | 249 | 100 |

Other activities (daily laborers, private business, non-government and civil servants) .

Prevalence of pesticide use among small-scale farmers

The prevalence of pesticide use among farmers in Dale Wabara, Hawa Gelan, and Sayyo districts of the Kellem Wellega zone in western Ethiopia was 90%, 83.3%, and 87.7%, respectively. The overall prevalence of current pesticide use was 217 (87.2%) and 32 (12.8%) of the study participants did not use chemical pesticides to increase agricultural productivity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Previous and current use of pesticides used by SSFs in the Kellem Wellega Zone in western Ethiopia, 2020.

| Name of districts | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Dale Wabara | 90 | 81 (90) |

| Seyo | 81 | 71 (87.7) |

| Hawa Galan | 78 | 65 (83.3) |

| Overall prevalence | 249 | 217 (87.2) |

Among the common pesticide chemicals used in the study area were 2, 4-D (69.1%), glyphosate (41.4%), diazinon (26.5%), malathion (55.4%), DDT (8.4%), mancozeb (25.7%), and diazinon (26.5%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of pesticides used by SSFs in the Kellem Wellega Zone in western Ethiopia, 2020.

| Type of pesticides | Name of districts | Total N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dale Wabara (N = 90) | Hawa Gelan (N = 78) | Sayyo (N = 81) | ||

| 2, 4-D* | 69 (76.7) | 45 (57.7) | 58 (71.6) | 172 (69.1) |

| DDT** | 4 (4.4) | 11 (14.1) | 6 (7.4) | 21 (8.4) |

| Glyphosate | 34 (37.8) | 27 (34.6) | 42 (51.9) | 103 (41.4) |

| Diazinon | 29 (32.2) | 12 (15.4) | 25 (30.9) | 66 (26.5) |

| Malathion | 59 (65.6) | 37 (47.4) | 42 (51.9) | 138 (55.4) |

| Mancozeb | 27 (30) | 13 (16.7) | 24 (29.6) | 64 (25.7) |

2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. ** Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.

Factors related to occupational exposure of SSFs

Knowledge of farmers on the safe use of pesticides

Although 87.2% of small-scale farmers used pesticides for their agriculture, only 42.2% know the safe use of pesticides. Most of them were used for weed control (52.6%). Approximately 76.3% of participants believed that pesticides are useful; however, they did not know the harmful effect of pesticides on humans and the environment in general. Most farmers did not have training (83.9%) on handling and using pesticides. Approximately 85% of them were used above the recommended concentrations and purchased from private companies, illegally at low cost. Most of the participants (93.6%) did not know the appropriate distance for mixing and loading pesticides from residential areas and water streams. Additionally, 67% of farmers carelessly disposed of leftover pesticides in open fields, and 40.6% stored in unsafe places, potentially exposing them. The mean score of knowledge on pesticide use was found to be 49.03 ± 0.5, which is summarized in Table 4. Consequently, 40.16% of small-scale farmers who scored below the mean had poor knowledge about the safe use of pesticides.

Table 4.

Knowledge of SSFs about the use of pesticides in the Kellem Wellega zone of western Ethiopia, 2020.

| Explanatory variables | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Have you ever used pesticides? | ||

| Yes | 217 | 87.2 |

| No | 32 | 12.9 |

| Know how to use pesticides safely? | ||

| Yes | 105 | 42.2 |

| No | 144 | 57.8 |

| Pesticide retailers | ||

| Government | 15 | 6.0 |

| Private | 138 | 55.4 |

| Both government and private | 72 | 28.9 |

| I don’t use | 24 | 9.6 |

| Purpose of using pesticides | ||

| Fungi control | 67 | 26.9 |

| Weed control | 131 | 52.6 |

| Pest control | 10 | 4.0 |

| Mixed-use | 9 | 3.6 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| How can you consider pesticide chemicals? | ||

| Useful | 190 | 76.3 |

| Harmful | 40 | 16.1 |

| Both useful and harmful | 19 | 7.6 |

| Have you ever had any training on how to use and handle pesticides? | ||

| Yes | 40 | 16.1 |

| No | 209 | 83.9 |

| Identifying the quantity of pesticides used? | ||

| Yes | 37 | 14.9 |

| No | 212 | 85.1 |

| Knowing the distance of mixing from home, river? | ||

| Yes | 16 | 6.43 |

| No | 233 | 93.6 |

| Pesticides storage | ||

| Stored everywhere | 101 | 40.6 |

| Stored in the kitchen | 57 | 22.9 |

| In mixed place | 48 | 19.3 |

| In separate place | 13 | 5.2 |

| I don’t use | 30 | 12.1 |

| What are the trends in the amount and frequency of pesticides used in the last few years? | ||

| Increase | 185 | 74.3 |

| Decrease | 64 | 25.7 |

| Level of knowledge | ||

| Poor (<49.03%) | 100 | 40.2 |

| Good (⩾49.03%) | 149 | 59.8 |

| Total | 249 | 100 |

Practice pesticides use

Among farmers who have been using pesticides for more than 10 years (49%), still, 96.8% of them do not understand the instruction and labeling provided by the users in the pesticide containers (96.8%). Small-scale farmers involved in spraying activities were more likely to be exposed to pesticides by eating and drinking (26.1%), chewing chat (16.1%), smoking (26.9%), performing different exposing activities (18.1%), and using damaged equipment during spraying (15.7%). Around 40.6% of farmers used more than 4 L of pesticide chemicals for small land size. As Table 5 shows, the mean score of the farmers’ practices for safe use of pesticides was found to be 50.64 ± 0.5. Almost half of them scored below mean values and had a poor practice that makes them more vulnerable to pesticide chemicals.

Table 5.

Practice of SSFs toward pesticides use the Kellem Wellega Zone of western Ethiopia, 2020.

| Explanatory variables | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Working experience with pesticides | ||

| <3 years | 61 | 24.5 |

| 3-10 years | 34 | 13.7 |

| >10 years | 122 | 49 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Understanding the labeled instruction | ||

| Yes | 8 | 3.21 |

| No | 241 | 96.8 |

| Who sprays pesticides | ||

| Employ | 78 | 31.3 |

| Father | 99 | 39.8 |

| Mother | 40 | 16.1 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Activities performed during spraying | ||

| Eat and drink | 65 | 26.1 |

| Chewing chat | 40 | 16.1 |

| Smoking | 67 | 26.9 |

| Mixed activities | 45 | 18.1 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Types of spraying equipment | ||

| Backpack | 216 | 86.8 |

| Handhold | 33 | 13.3 |

| Condition of the equipment | ||

| Damaged | 39 | 15.7 |

| Not damaged | 178 | 71.5 |

| I do not use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Weather condition during pesticide spraying | ||

| Humid and cold | 25 | 10.0 |

| Dry and hot | 192 | 77.1 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Crop area | ||

| 0-2 hectare | 203 | 81.5 |

| 2.1-4 hectare | 37 | 14.9 |

| >4 hectare | 9 | 3.6 |

| Amount of pesticide | ||

| 0-2 L | 8 | 3.2 |

| 2.1-4 L | 108 | 43.4 |

| >4 L | 101 | 40.6 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Frequency of application | ||

| Once times a year | 83 | 33.3 |

| Two times a year | 88 | 35.3 |

| Three times a year or more | 46 | 18.5 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Overall pesticide use practice | ||

| Poor (<50.64%) | 124 | 49.8 |

| Good (⩾50.64%) | 125 | 50.2 |

| Total | 249 | 100 |

Attitude of farmers toward the use of pesticides

Approximately 84.3% of small-scale farmers did not use PPE during spraying. Some farmers mixed and washed their containers in the house (26.1%), and rivers (24.1%). About 47.39% of small-scale farmers never follow the instruction on the label of the pesticide containers. Regarding sprayer hygiene, (57.4%) wash only hands, (22.9%) bathe, and (6.8%) change clothes before or after spraying. During mixing and spraying (71.1%) mentioned that pesticides spill onto their body (42.6%), spraying against the wind, and (50.2%) of the farmers were re-entered in a recently sprayed farmland. Some farmers did not know the final fate of pesticides (38.2%) and (59%) used pesticide equipment for other purposes. Regarding the container of pesticides that uses them as home utensils (53.4%), thrown into fields (7.6%), sold to others (8.8%), disposed of in streams (12.4%), mixed-use (4.4%), buried, and burned (1.6%) and returned to a disposing agent (2%). In general, Table 6 shows that the mean score of farmers’ attitudes toward pesticide use was 47.89 ± 0.49. About 47.8% of the participants who scored below the mean had a negative attitude toward pesticides.

Table 6.

Attitude of SSFs toward pesticide use in the Kellem Wellega Zone of western Ethiopia, 2020.

| Explanatory variables | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Can you understand the information written on the pesticide packages? | ||

| Yes | 131 | 52.6 |

| No | 118 | 47.4 |

| Should you wear protective equipment during spraying? | ||

| Yes | 39 | 15.7 |

| No | 210 | 84.3 |

| Appropriate locations for mixing pesticide or washing container | ||

| House | 65 | 26.1 |

| River | 60 | 24.1 |

| Farmland | 53 | 21.3 |

| Mixed | 39 | 15.7 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Have you ever spilled pesticides on your body? | ||

| Yes | 177 | 71.1 |

| No | 72 | 28.9 |

| How can you prevent the splash of pesticides during spraying? Practices after spraying | ||

| Washing only hands | 143 | 57.4 |

| Bathing | 57 | 22.9 |

| Changing clothes | 17 | 6.8 |

| I don’t use | 32 | 12.9 |

| Spraying against the wind | ||

| Yes | 106 | 42.6 |

| No | 143 | 57.4 |

| Entering recently sprayed farmland | ||

| Yes | 67 | 26.9 |

| No | 182 | 73.1 |

| Did farmers use empty pesticide equipment for other purposes? | ||

| Yes | 147 | 59.0 |

| No | 102 | 41 |

| Do you think pesticides empty materials can harm your health? | ||

| Yes | 154 | 61.9 |

| No | 95 | 38.2 |

| What solutions do you suggest for the empty pesticide container disposal methods? | ||

| Home use reuse at home | 133 | 53.4 |

| Thrown into fields | 19 | 7.6 |

| Sold to others | 22 | 8.8 |

| Thrown into streams | 31 | 12.5 |

| Mixed-use | 11 | 4.4 |

| Buried or burned | 4 | 1.6 |

| Return to disposing agent | 5 | 2.0 |

| I don’t use | 24 | 9.6 |

| Level of attitude | ||

| Poor (<47.89%) | 119 | 47.8 |

| Good (⩾47.89%) | 130 | 52.2 |

| Total | 249 | 100 |

Acute health symptoms of SSFs

The results of this study showed that nearly all agricultural farmers have symptoms of acute health after using pesticides. The most often symptoms linked to pesticides use includes coughing (61%), headache (62.7%), vomiting (41.8%), skin irritation (29.3%), and abdominal pain (28.1%) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Acute health symptoms of SSFs during pesticide application of SSFs in the Kellem Wellega Zone in western Ethiopia, 2020.

| Outcome variables | Yes | % | No | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coughing | 152 | 61 | 97 | 39 |

| Headache | 156 | 62.7 | 93 | 37.3 |

| Vomiting | 104 | 41.8 | 145 | 58.2 |

| Skin irritation | 73 | 29.3 | 176 | 70.7 |

| Abdominal pain | 70 | 28.1 | 179 | 71.9 |

Determinant of health symptoms

The formulation of pesticides was an essential factor in human exposure to pesticide chemicals. The liquid mist was the predominant type of farmers’ exposure that takes place during the production, transportation, preparation, and application of pesticides in the workplace. In the study area, agricultural occupations pesticide exposure occurs via through the main route of inhalation (51.4%), ingestion (59.8%), and skin contact (58.6%).

Table 8 shows the bivariate analysis of exposure to pesticides with sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge, practice, attitude, route of exposure, and self-reported symptoms of exposure to pesticides. In the analysis: age, job, educational level, knowledge, and practice were significantly associated with a P-value <.05 with the outcome variables of coughing, headache, skin irritation, inhalation, and skin contact. The remaining variables were not significantly associated with the outcome variables. The results of the logistic regression analysis of the exposure of farmers to pesticide use and associated factors are summarized in Table 6. In study jobs, educational level, knowledge, practice, coughing, headache, skin irritation, inhalation, and skin contact are significantly associated with the exposure of farmers to pesticide chemicals.

Table 8.

Results of the logistic regression analysis of self-reported symptoms of SSFs and associated factors in the Kellem Wellega zone of western Ethiopia, 2020.

| Explanatory variables | Coughing | Headache | Skin irritation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes 152 (61%) |

No 97 (39%) |

Yes 156 (62.7%) |

No 93 (37.3%) |

Yes 73 (29.3%) |

No 176 (70.7%) |

|

| COR | AOR | COR | AOR | COR | AOR | |

| Age | ||||||

| ⩽20 years | 0.45 (0.19-1.08) | 0.46 (0.19-1.12) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 21-40 | 0.93 (0.53-1.62) | 1.0 (0.56-1.79) | 9.27 (2.08-41.30)* | 7.87 (1.75-35.45)* | ||

| ⩾41 years | 1 | 1 | 1.16 (0.65-2.07) | 1.23 (0.68-2.21) | ||

| Jobs | ||||||

| Farming | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Other activities | 0.68 (0.37-1.27) | 1.41 (0.73-2.71) | 2.13 (1.12-4.05)* | 0.89 (0.44-1.78) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Non-formal | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Primary school | 1.59 (0.74-3.43) | 2.25 (0.94-5.42) | ||||

| Secondary school and above | 1.15 (0.54-2.48) | 1.89 (0.79-4.54) | ||||

| Income | ||||||

| <1000 birr | 0.49 (0.1-2.48) | 0.52 (0.1-2.66) | ||||

| 1000-2000 | 2.84 (1.37-5.92)* | 2.62 (1.25-5.51)* | ||||

| 2000-3000 | 1.35 (0.66-2.73) | 1.38 (0.64-2.81) | ||||

| >3000 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Level of knowledge | ||||||

| Poor | 1 | 1 | 2.15 (1.24-3.75)* | 1.79 (1.0-3.17)* | ||

| Good | 0.66 (0.39-1.1) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Level of practice | ||||||

| Poor | 0.48 (0.28-0.81)* | 1.85 (1.08-3.2)* | 1.91 (1.14-3.22)* | 0.52 (0.31-0.88)* | ||

| Good | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odd ratio; COR, crude odd ratio; CI, confidence interval; SSFs, small-scale farmers.

Other activities (daily laborers, private business, non-government and civil servants).

Represent the level of significance at P-values <.05.

Thus, SSFs whose age was greater than 40 years were 7.87 times more likely to be exposed to skin irritation than those whose age was less than 20 years (AOR = 7.87; 95% CI: 1.75-35.45) and skin contact (AOR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.15-0.91). Most farmers who were directly involved in agriculture were 2.22 times more likely to be exposed to the inhalation of pesticide chemicals than those involved in another activity (AOR = 2.22; 95% CI: 1.14-4.33). Based on educational level, small-scale farmers who have a primary school and above were 81% less likely to be inhaled than those who did not have formal education (AOR = 0.19; 95% CI: 0.09-0.41). Furthermore, low-income SSFs were 2.62 times more likely to be exposed to coughing (AOR = 2.62; 95% CI: 1.25-5.51) than high-income participants. Additionally, farmers with good knowledge were 1.79 times more likely to be exposed to skin irritation than those with poor knowledge (AOR = 1.79; 95% CI: 1.0-3.17). Farmers with poor practice were 1.85 times more likely to show symptoms of coughing than those with good practice (AOR = 1.85; 95% CI: 1.08-3.2), and farmers with the good practice were 48% less likely to be exposed to headache than those with poor practice (AOR = 0.52; 95% CI: 0.31-0.88).

Discussion

This study assessed the prevalence of pesticide use and occupational exposure of small-scale farmers in the Kellem Wellega zone of western Ethiopia. Therefore, 87.2% of small-scale farmers have used at least one or more pesticide chemicals for agricultural purposes (Table 2). This is higher than the study report from southern Ethiopia (83.3%) and southwest (82%) of Ethiopian farmers.27,30 This showed that there is an increasing trend in the use of chemical pesticides among small-scale farmers. 31

Thus, SSFs whose age was greater than 40 years were 7.87 times more likely to be exposed to skin irritation than those whose age was less than 20 years (AOR = 7.87; 95% CI: 1.75-35.45) and skin contact (AOR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.15-0.91) (Table 8). This reveals that younger groups would be convenient for the recommended PPE on pesticides use as compared to older SSFs who could use more pesticides to maximize their products 18 and due to bioaccumulation of pesticides from past exposure and decreasing rates of excretion with increasing age for small-scale farmers.21,32

Additionally, the educational level of small-scale farmers who have a primary school and above was 81% less likely to be inhaled than those who did not have formal education (AOR = 0.19; 95% CI: 0.09-0.41). In this study, about 47.4% and 96.8% of the participants never followed and understood the labeled instruction, respectively. This is due to their low educational level and their instructions, often written in foreign languages (Table 5). A study conducted in Pakistan revealed that 48.2% of farmers did not follow the labeled instructions 26 and in Kuwait, over 70% of farmers did not read or follow the instructions on the pesticide label. 19 Furthermore, low-income SSFs were 2.62 times more likely to be exposed to coughing (AOR = 2.62; 95% CI: 1.25-5.51) than high-income participants. These suggest that farmers in the study area were exposed to pesticide chemicals due to not using complete PPE since they cannot afford the price and are not easily available on market.33-35

On the other hand, farmers with good knowledge were 1.79 times more likely to be exposed to skin irritation (AOR = 1.79; 95% CI: 1.0-3.17) than those with poor knowledge and skin contact (AOR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.15-0.91). This was lower than the study reported from Egyptian 36 and southern Ethiopian farmers. 37 This is due to the low awareness of the harmful effects of pesticides on humans and the environment.35,37Additinally, the level of knowledge of farmers on the safe use of pesticides is very inadequate. 38 Moreover, some farmers who had a sufficient level of knowledge of the safe use of pesticides did not implement their knowledge into practice.23,39 Furthermore, exposure can occur through skin contact with contaminated hands after pesticide-related work.18,23

Similarly, farmers with the poor practice were 1.85 times more likely to be exposed to coughing than those with good practice (AOR = 1.85; 95% CI: 1.08-3.2), and farmers with the good practice were 48% less likely to be exposed to headaches than those with poor practice (AOR = 0.52; 95% CI: 0.31-0.88). A similar report from the Philippines revealed that the most common self-reported symptoms were headache (64.1%), cough (45.5%), weakness (42.4%), eye pain (39.9%), and chest pain (37.4%). 40 Furthermore, 90% of the respondents to the Rwandan study show adverse health effects on farmers, such as intense headache, dizziness, stomach cramps, skin pain, itching, and respiratory distress after using pesticides. 41 This could be due to practicing everyday activities without worrying during spraying, such as eating, drinking, smoking, chewing, and even using damaged backpack sprayer equipment to increase exposure.27,37 In addition spraying within the hot and dry conditions usually results in rapid evaporation of pesticide chemicals 41 that can distract the proper spraying man and take the chemical off-target. 40 Moreover, mixing the pesticides with bare hands, not wearing PPE, and carelessly disposing of leftover pesticides 42 causes high exposure of SSFs to pesticide chemicals. 21

Some limitations are worthy of note, however, sample size and self-reported symptoms when spraying pesticides might introduce recall bias and may have difficulty recalling them a whole year or even a month previously. Furthermore, there may be inaccuracies in reporting on pesticide chemical use history, frequency, training, and experience from both exposed and non-exposed SSFs that affect the result of past exposures.

Conclusions

The prevalence of pesticide use among small-scale farmers in western Ethiopia was 87.2%. In this study, small-scale farmers were exposed to coughing, headache, skin irritation, inhalation, and skin contact with pesticide chemicals due to low level of knowledge, practice and education, age, work, and low income. Finally, it is recommended that the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Ministry of Health, and the Environmental Protection Authority work on integrated and continuous awareness creation programs that increase knowledge and practice on pesticide safety for small-scale farmers in Ethiopia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all volunteers for providing valuable information, Jimma University, and Oromia Education Bureau for valuable support.

Footnotes

Funding: The author (s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author (s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: Tariku Neme Afeta: Methodology, formal analysis, visualization, original draft writing. Dr. Gudina Terefe Tucho: Methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing review, editing. Dr. Seblework Mekonen: Methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing review editing, and Miftahe Shekelifa: Review and editing.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data sets analyzed during the current study were available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate: Ethical approval to conduct this research was obtained from the Jimma University Institute of Review Board (IRB) of the University of South-West Ethiopia, on 18/10/2019 (No. IHRPGD/407/2019). Written informed consent was obtained from the study participants. All subjects voluntarily participated in the study.

ORCID iDs: Tariku Neme Afata  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0844-9449

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0844-9449

Gudina Terefe Tucho  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7848-5456

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7848-5456

References

- 1. Bertomeu-Sánchez JR. Introduction. Pesticides: past and present. HOST. 2019;13:1-27. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Damalas CA, Koutroubas SD. Farmers’ exposure to pesticides: toxicity types and ways of prevention. Toxics. 2016;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang L, Liu Z, Zhang J, Wu Y, Sun H. Chlorpyrifos exposure in farmers and urban adults: metabolic characteristic, exposure estimation, and potential effect of oxidative damage. Environ Res. 2016;149:164-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lebov JF, Engel LS, Richardson D, Hogan SL, Hoppin JA, Sandler DP. Pesticide use and risk of end-stage renal disease among licensed pesticide applicators in the agricultural health study. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koh S-B, Kim TH, Min S, Lee K, Kang DR, Choi JR. Exposure to pesticide as a risk factor for depression: a population-based longitudinal study in Korea. Neurotoxicol. 2017;62:181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Maele-Fabry G, Gamet-Payrastre L, Lison D. Residential exposure to pesticides as risk factor for childhood and young adult brain tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2017;106:69-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen S, Gu S, Wang Y, et al. Exposure to pyrethroid pesticides and the risk of childhood brain tumors in east China. Environ Pollut. 2016;218:1128-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malagoli C, Costanzini S, Heck JE, et al. Passive exposure to agricultural pesticides and risk of childhood leukemia in an Italian community. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2016;219:742-748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lebov JF, Engel LS, Richardson D, Hogan SL, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA. Pesticide exposure and end-stage renal disease risk among wives of pesticide applicators in the agricultural health study. Environ Res. 2015;143:198-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muñoz-Quezada MT, Lucero BA, Iglesias VP, et al. Chronic exposure to organophosphate (OP) pesticides and neuropsychological functioning in farm workers: a review. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2016;22:68-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Damalas C, Koutroubas S, Abdollahzadeh G. Drivers of personal safety in agriculture: a case study with pesticide operators. Agriculture. 2019;9:34. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ouedraogo R, Makoum TOE, Sylvain I, Innocent G. Risk of workers exposure to pesticides during mixing/loading and supervision of the application in sugarcane cultivation in Burkina Faso. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2014;2:143-151. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mekonen S, Ambelu A, Spanoghe P. Pesticide residue evaluation in major staple food items of Ethiopia using the QuEChERS method: a case study from the Jimma zone. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2014;33:1294-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akomea-Frempong S, Ofosu IW, Owusu-Ansah ED-GJ, Darko G. Health risks due to consumption of pesticides in ready-to-eat vegetables (salads) in Kumasi, Ghana. Int J Food Contam. 2017;4:13. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akoto O, Gavor S, Appah MK, Apau J. Estimation of human health risk associated with the consumption of pesticide-contaminated vegetables from Kumasi, Ghana. Environ Monit Assess. 2015;187:244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ali T, Ismail M, Asad F, Ashraf A, Waheed U, Khan QM. Pesticide genotoxicity in cotton picking women in Pakistan evaluated using comet assay. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2018;41:213-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boccolini PDMM, Boccolini CS, Chrisman JDR, Koifman RJ, Meyer A. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma among Brazilian agricultural workers: a death certificate case-control study. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2017;72:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jallow MF, Awadh DG, Albaho MS, Devi VY, Thomas BM. Pesticide knowledge and safety practices among Farm workers in Kuwait: results of a survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Negatu B. Occupational Risks and Health Effects of Pesticides in Three Commercial Farming Systems in Ethiopia. PhD thesis. Utrecht University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gangemi S, Gofita E, Costa C, et al. Occupational and environmental exposure to pesticides and cytokine pathways in chronic diseases (review). Int J Mol Med. 2016;38:1012-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Afata TN, Mekonen S, Tucho GT. Evaluating the level of pesticides in the blood of small-scale Farmers and its associated risk factors in western Ethiopia. Environ Health Insights. 2021;15:11786302211043660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sharifzadeh MS, Abdollahzadeh G, Damalas CA, Rezaei R, Ahmadyousefi M. Determinants of pesticide safety behavior among Iranian rice farmers. Sci Total Environ. 2019;651:2953-2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taghdisi MH, Amiri Besheli B, Dehdari T, Khalili F. Knowledge and practices of safe use of pesticides among a group of Farmers in northern Iran. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2019;10:66-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Groot MJ, Van’t Hooft KE. The hidden effects of dairy farming on public and environmental health in the Netherlands, India, Ethiopia, and Uganda, considering the use of antibiotics and other agro-chemicals. Front Public Health. 2016;4:12-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mubushar M, Aldosari FO, Baig MB, Alotaibi BM, Khan AQ. Assessment of farmers on their knowledge regarding pesticide usage and biosafety. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2019;26:1903-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Negatu B, Vermeulen R, Mekonnen Y, Kromhout H. A method for semi-quantitative assessment of exposure to pesticides of applicators and re-entry workers: an application in three farming systems in Ethiopia. Ann Occup Hyg. 2016;60:669-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gesesew HA, Woldemichael K, Massa D, Mwanri L. Farmers knowledge, attitudes, practices and health problems associated with pesticide use in rural irrigation villages, southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Central Statistical Agency and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. CSA and ICF; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rabira G, Tsegaye G, Tadesse H. The diversity, abundance and habitat association of medium and large-sized mammals of Dati Wolel National Park, western Ethiopia. Int J Biodivers Conserv. 2015;7:112-118. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ligani S. Assessments of pesticide use and practice in Bule Hora districts of Ethiopia. Saudi J Life Sci. 2016;1:103. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Negatu B, Dugassa S, Mekonnen Y. Environmental and health risks of pesticide use in Ethiopia. J Health Pollut. 2021;11:210601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ben Hassine S, Hammami B, Ben Ameur W, et al. Concentrations of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in human serum and their relation with age, gender, and BMI for the general population of Bizerte, Tunisia. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014;21:6303-6313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Negatu B, Kromhout H, Mekonnen Y, Vermeulen R. Use of chemical pesticides in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional comparative study on knowledge, attitude and practice of Farmers and Farm workers in three farming systems. Ann Occup Hyg. 2016;60:551-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Migheli M. Income, wealth and use of personal protection equipment in the Mekong Delta. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28:39920-39937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mengistie BT, Mol APJ, Oosterveer P. Pesticide use practices among smallholder vegetable farmers in Ethiopian central Rift Valley. Environ Dev Sustain. 2017;19:301-324. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mohammed M, EL-Din SAB, Sadek R, Mohammed A. Knowledge, attitude and practice about the safe use of pesticides among Farmers at a village in MiniaCity, Egypt. J Nurs Health Sci. 2018;7:68-78. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ocho FL, Abdissa FM, Yadessa GB, Bekele AE. Smallholder farmers’ knowledge, perception and practice in pesticide use in south western Ethiopia. J Agric Environ Int Dev. 2016;110:307-323. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Öztaş D, Kurt B, Koç A, Akbaba M, İlter H. Knowledge level, attitude, and behaviors of Farmers in Çukurova region regarding the use of pesticides. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:6146509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sankoh AI, Whittle R, Semple KT, Jones KC, Sweetman AJ. An assessment of the impacts of pesticide use on the environment and health of rice farmers in Sierra Leone. Environ Int. 2016;94:458-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lu JL. Assessment of pesticide-related pollution and occupational health of vegetable farmers in Benguet province, Philippines. J Health Pollut. 2017;7:49-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ndayambaje B, Amuguni H, Coffin-Schmitt J, Sibo N, Ntawubizi M, VanWormer E. Pesticide application practices and knowledge among small-scale local rice growers and communities in Rwanda: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Satya Sai MV, Revati GD, Ramya R, Swaroop AM, Maheswari E, Kumar MM. Knowledge and perception of Farmers regarding pesticide usage in a rural farming village, southern India. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2019;23:32-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]