Abstract

We applied graph theory analysis on resting-state functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging data to evaluate sex differences of brain functional topography in normal controls (NCs), early mild cognitive impairment (eMCI), and AD patients. These metrics were correlated with RAVLT verbal learning and memory scores. The results show NCs have better FC metrics than eMCI and AD, and NC women show worse FC metrics compared to men, despite performing better on RAVLT. FC differences between men and women diminished in eMCI and disappeared in AD. Within women, better FC metrics relate to better RAVLT learning in NCs and eMCI groups.

Introduction

Men and women differ in prevalence, incidence, or symptomatology of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer Disease (AD). Two-thirds of current AD sufferers are women, and their greater longevity cannot explain this ratio [1]. The reasons behind sex disparities in AD are not completely understood, but one area of interest is functional neuroimaging. Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) can be used to reveal and characterize brain FC [2]. Here, the healthy brain is a complex dynamic system composed of networks with multiple spatial and time scales, modular structure and balance between neural network segregation and integration [3]. Considering AD a disconnection syndrome [4] graph theory analysis is a robust tool to explore rs-fMRI connectivity patterns [5]. Regarding sex differences in rs-fMRI, across the lifespan, NC women show higher cortical FC mostly in the left hemisphere, whereas men have higher connectivity in the right [6]. A recent review of studies in children and young adults showed males had more between-module, and females had more within-module, connectivity [7]. Our group also has found network-level sex differences in rs-fMRI in AD [8]. However, no studies employing graph theory have examined sex differences in NCs, eMCI and AD.

The investigation of modularity pattern changes in physiological and pathological aging may illuminate sex disparities in AD. However, elucidating sex differences in FC is difficult, as fMRI data contains significant noise, for example from head-motion and physiological oscillations [9]. As such, data denoising techniques are key. Our group has developed and validated an artificial intelligence, time-dependent deep neural network approach, which substantially improves fMRI data quality and strengthens statistical power to detect effects by disentangling the time series between gray matter (GM) and non-GM [10–12]. The aim of our study was to apply this technique on data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI, http://adni.loni.usc.edu/) to evaluate sex differences in graph theory metrics of FC in NC, eMCI, and AD, and their relationship with learning and memory.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, including longitudinal study of AD biomarkers.193 participants with resting-state fMRI and T1 MRI data available in the ADNI database were included. Subjects were scanned on 3.0 Tesla Philips MRI scanners and diagnosed as NCs (27 men/33 women, age 75.9±5.6 years, education 16.5±2.4), eMCI (39 men/31 women, age 73.6±7.0 years, education 15.9±2.8) or AD (36 men/27 women, age 73.5±8.4, education 15.9±2.7).

Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT):

We assessed verbal learning and recall with RAVLT total immediate recall (i.e., total of 5 learning trials), learning (i.e., total immediate recall – Trial 1 total), and delayed recall scores [13].

MRI data.

Structural MRI scans were collected with 24cm field of view, 256×256×170 resolution, for 1×1×1.2mm3 voxel size. Standard echo-planar imaging sequence was used to collect rs-fMRI data with 140 time points, TR/TE=3000/30 ms, flip angle=80 degrees, 48 slices, spatial resolution=3.3× 3.3×3.3mm3 and imaging matrix=64 × 64. The first five volumes were discarded. Preprocessing steps included slice-timing correction, realignment, coregistration to skull-stripped T1 images and spatial normalization to MNI152 2mm template space.

Graph Theory Analysis.

With the functional network generated with AAL atlas [14], graph theory analysis was applied using GRETNA toolbox [15]. Five global metrics derived from graph theoretical analysis were found to be significantly different between NC and AD groups [12], including degree centrality (DC), global efficiency (GE), local efficiency (LE), clustering coefficient (Cp), and characteristic path length (Lp). In this study, we specifically examined the sex differences of brain functional topography using these five graph theory metrics.

Data Analysis.

2-sample t-tests were applied to evaluate differences between women and men in each diagnostic group on memory scores and graph theory metrics. ANCOVA was used to evaluate the interactive effect of sex, diagnosis, and network metrics on memory scores. A post-hoc generalized linear regression model then was applied to test the significance of the association in each diagnostic group for women and men separately. In addition, we carried out regression analysis to compare the slope difference between learning and memory (including immediate and delayed recall) scores versus graph theory metrics. Age, handedness and education were included as confounding factors in ANCOVA and regression analyses.

Results

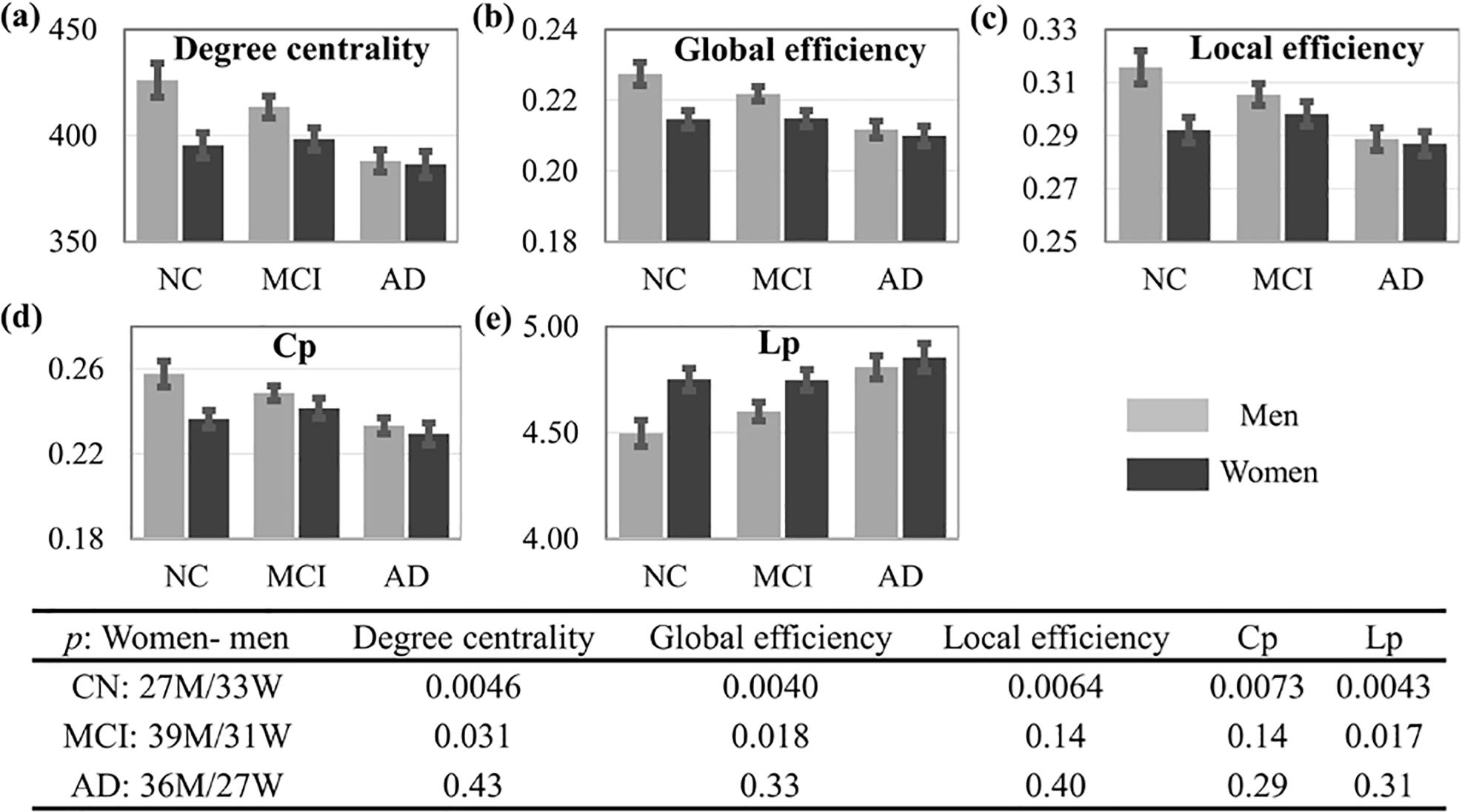

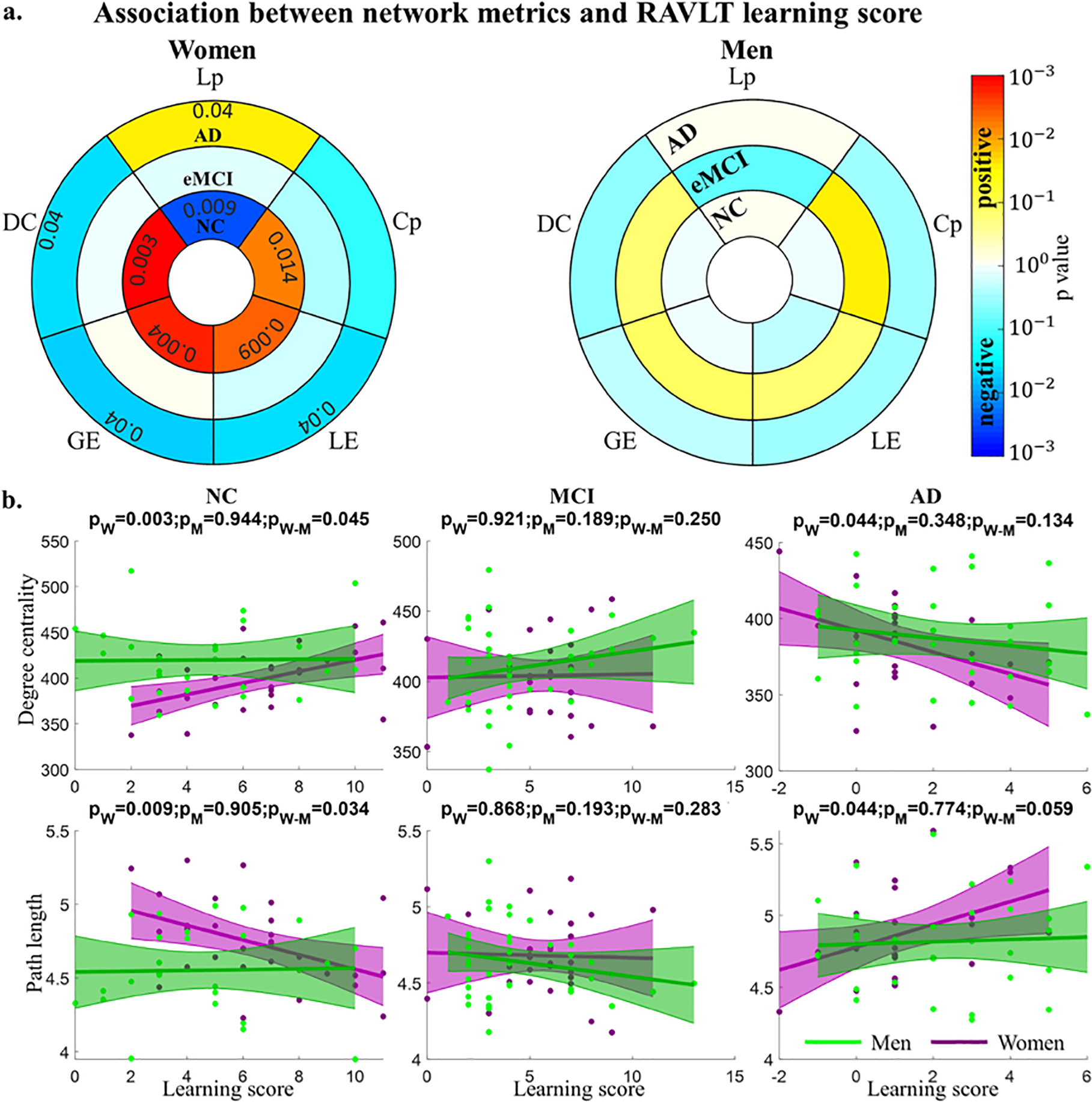

NC women had significantly lower DC, GE, LE, and Cp, and significantly higher Lp. This sex difference diminished in eMCI, with only DC, GE, and Lp remaining significant. No significant sex difference was observed in AD for graph theory metrics (See Fig. 1). Women had significantly higher immediate recall scores than men in NC (p=0.04) and eMCI (p=0.008) but no significant difference in AD. Learning scores were also higher in women than men in NC (p=0.05) and eMCI (p=0.01); a marginal difference was observed in AD, with men showing better learning (p=0.08). Delayed recall scores were not significantly different by sex in any diagnostic group. ANCOVA showed a significant 3-way diagnosis by gender by graph theory metric interaction effect on RAVLT learning for four out of five network metrics (p=0.021, 0.023, 0.023, 0.023 and 0.036 for DC, GE, LE, Cp and Lp, respectively) However, no interaction effect was observed for RAVLT immediate or delayed recall. When broken down by diagnosis, NC women had significant associations between network metrics and learning scores (all positive with the exception of Lp). No significant association was observed in eMCI women, though opposite direction, significant associations were observed in AD women. None of the associations were significant for men. The significance of the association between RAVLT learning and network metrics were shown in Fig. 2a with only significant p values marked in the figure. The scatter plots for DC and Lp, along with the fitting lines with 95% confidence interval, were shown in Fig. 2b. The plots for GE, LE, Cp within each diagnostic group for women and men were similar to the corresponding plots for DC, thus these plots were not shown in the manuscript. We compared the slope difference between memory and learning scores versus network metrics within each diagnostic group for women and men separately (see p values Table 1 and scatter plots in Supplementary Fig. 1). The majority of the significant difference occurred in women among NC or AD group, indicating that brain functional network topology is more strongly associated with learning instead of memory scores and such an effect is sex dependent.

Fig. 1.

Sex differences in graph theory metrics within diagnostic groups. Significant differences were observed between AD and NCs. The p values of the sex differences in NCs, eMCI and AD groups for these five metrics are shown in the bottom.

Fig. 2.

Association of network metrics with RAVLT learning score. a. p values of the association, only the significant associations are marked with p value in the figure. b. Scatter plots of the association for degree centrality (DC) and characteristic path length (Lp). The plots for global efficiency, local efficiency and clustering coefficient are similar to the corresponding plots for degree centrality and thus these plots are not shown in the figure.

Table 1.

Significance of slope difference between memory and learning scores versus network metrics. Significant p values are marked in bold.

| Metrics | Immediate recall - Learning | Delayed recall - Learning | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||

| NC | MCI | AD | NC | MCI | AD | NC | MCI | AD | NC | MCI | AD | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| DC | 0.489 | 0.109 | 0.151 | 0.005 | 0.471 | 0.062 | 0.264 | 0.438 | 0.313 | 0.009 | 0.389 | 0.035 |

| GE | 0.478 | 0.089 | 0.304 | 0.005 | 0.429 | 0.090 | 0.267 | 0.274 | 0.470 | 0.008 | 0.298 | 0.027 |

| LE | 0.263 | 0.126 | 0.124 | 0.021 | 0.395 | 0.051 | 0.438 | 0.426 | 0.353 | 0.035 | 0.352 | 0.032 |

| Cp | 0.396 | 0.026 | 0.124 | 0.022 | 0.377 | 0.079 | 0.382 | 0.208 | 0.307 | 0.076 | 0.467 | 0.141 |

| Lp | 0.480 | 0.105 | 0.362 | 0.010 | 0.448 | 0.108 | 0.313 | 0.289 | 0.463 | 0.017 | 0.304 | 0.028 |

Discussion

We applied our recently validated DeNN method [12] to explore sex differences in NC, eMCI, and AD subjects from ADNI, showing that consistent with the literature [16; 17] NCs had better graph theory metrics than those with eMCI and AD. Within NCs, women showed significantly lower values of all metrics, except Lp (significantly higher). Sex differences diminished in eMCI, though women continued to show significantly lower DC and GE, and higher Lp than men. In AD, no significant sex difference was observed. In NC women, FC metrics were positively correlated with RAVLT learning, except Lp, which was anticorrelated (Fig. 2). In eMCI women, there were no significant correlations, and AD women showed significant anticorrelation of learning scores and FC metrics, except Lp, which was significantly positively correlated. Although not significant, RAVLT and FC associations were essentially opposite in men.

In our sample, when compared to NC men, NC women show a pattern more similar to the pathological groups in all graph theory metrics. This is also true in the eMCI group for DC, GE, and Lp. Overall, women showed worse integration and segregation values compared to men, despite significantly better verbal learning scores. Our sex differences findings are partially consistent with work showing higher modularity and transitivity in young men versus women [18], though are not consistent with recent review in children and young adults [7]. Although we cannot speak to causation, these results may suggest that weaknesses in segregation and integration contribute to vulnerability of women to AD.

Despite worse FC metrics, NC women had better learning scores than men, confirming previous findings [19]. In the eMCI stage, women show a similar pattern of better learning scores than men, but there are no longer sex differences in AD. Women also showed differences as compared to men in the way FC metrics related to learning performance. Although NC and eMCI women show similar learning performances, which are better than men’s, the sign of FC metrics correlation is inverted (not significantly) in three cases out of four (DC, LE and Cp; GE remains positive correlated and Lp remains negative correlated). In men the change of sign (from positive to negative) occurs only in the AD group (not significantly). Perhaps FC metrics in women degenerate earlier than men and baseline learning and memory performances offer resilience against aging, but with a paradoxical effect. In fact, greater “cognitive reserve” in women is related to reduced clinical progression in predementia stages of AD (eMCI), but accelerated cognitive decline after the onset of dementia (lower learning scores) and also related to worse FC metrics. This paradoxical effect of cognitive reserve has been recently pointed out [20, 21]. Although our data is cross-sectional, early resilience showed by women, which is completely lost in dementia stage, suggests a steeper rate of decline.

Limitations of our study include absence of longitudinal data and analysis of specific resting state networks. Future studies should explore sex differences in memory-specific neural networks. Moreover, we know that the Default Network is “normally” highly clustered, but it tends to lose “connectedness” in neurodegeneration becoming more intermingled with task positive networks [22]. The analysis of these specific networks might clarify our results.

In conclusion, neuroaging seems to occur earlier in women and pathological biomarker changes - such as FC - seem to anticipate the cognitive impairment observed in AD. Our group has already shown that cognitive healthy women may show normal memory despite AD pathology [23, 8]. Our DeNN method confirmed differences between individuals with healthy and impaired cognition and showed new differences between men and women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number 5P20GM109025. In addition, research reported in this publication was supported in part by a grant from The Women’s Alzheimer’s Movement/Maria Shriver to Caldwell. A private grant from the Peter and Angela Dal Pezzo funds, a private grant from Lynn and William Weidner, a private grant from Stacie and Chuck Matthewson, and the young scientist award at Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health (Keep Memory Alive Foundation). Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12–2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Alzheimer Association. 2020. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. SPECIAL REPORT. On the Front Lines: Primary Care Physicians and Alzheimer’s Care in America. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cieri F and Esposito R (2018). Neuroaging through the Lens of the Resting State Networks. BioMed Research International, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tononi G, Sporns O, Edelman GM (1994) A measure for brain complexity: relating functional segregation and integration in the nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:5033–5037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Geschwind N, 1965. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. Brain 88, 237–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nature reviews. 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6[.Gong G et al. (2009) Age-and gender-related differences in the cortical anatomical network. J Neurosci 29(50):15684–15693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gur RC, & Gur RE (2017). Complementarity of sex differences in brain and behavior: From laterality to multimodal neuroimaging. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95(1–2), 189–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8[.Caldwell JZK, et al. (2019). Sex moderates amyloid and apolipoprotein ε4 effects on default mode network connectivity at rest. Frontiers in Neurology, 10(AUG) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Caballero-Gaudes C and Reynolds RC, Methods for cleaning the BOLD fMRI signal. NeuroImage, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yang Z et al. , 2019. Robust motion regression of resting-state data using a convolutional neural network model. Frontiers in neuroscience, 2019. 13: p. 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yang Z et al. , 2020a. A robust deep neural network for denoising task-based fMRI data: An application to working memory and episodic memory. Medical Image Analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yang Z, et al. , 2020b. Disentangling time series between brain tissues improves fMRI data quality using a time-dependent deep neural network. NeuroImage, 2020. 223: p. 117340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rey A L’examen clinique en psychologie [the clinical psychological examination] Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. 1964. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tzourio-Mazoyer N, et al. 2002. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 15, 273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang J, et al. , 2015. GRETNA: a graph theoretical network analysis toolbox for imaging connectomics. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 2015. 9: p. 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cope TE, Rittman T, Borchert RJ, et al. Tau burden and the functional connectome in Alzheimer’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. 2018;141(2):550–567. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang Z, et al. Functional Connectivity Changes Across the Spectrum of Subjective Cognitive Decline, Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neuroinform. 2019. Apr 24;13:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ingalhalikar M et al. Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(2):823–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Brunet H, Caldwell JZK, Brandt J, Miller JB. Influence of sex differences in interpreting learning and memory within a clinical sample of older adults. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].van Loenhoud AC, et al. Cognitive reserve and clinical progression in Alzheimer disease: A paradoxical relationship. Neurology. 2019. Jul 23;93(4):e334–e346. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007821. Epub 2019 Jul 2. PMID: 31266904; PMCID: PMC6669930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yoon B, Shim YS, Park HK, Park SA, Choi SH, Yang DW. Predictive factors for disease progression in patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(1):85–91. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150462. PMID: 26444786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Esposito R, Cieri F, et al. Modifications in resting state functional anticorrelation between default mode network and dorsal attention network: comparison among young adults, healthy elders and mild cognitive impairment patients. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(1):127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Caldwell JZK, et al. (2017). Moderating effects of sex on the impact of diagnosis and amyloid positivity on verbal memory and hippocampal volume. Alzheimer’s research & therapy, 9(1), 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.