Abstract

Background:

The clinical picture of COVID-19 is as complex as it is psychosocial impact. The sheer subjectivity of the illness experience demands that each individual affected be heard and noticed.

Aims:

To assess lived-in experiences and coping strategies of COVID-19 positive individuals.

Settings and Design:

The study was conducted at designated COVID care center of a tertiary care hospital using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach.

Materials and Methods:

Interviews were collected from 13 COVID-19-positive individuals using an open-ended interview guide and were recorded, transcribed and further analyzed.

Statistical Analysis:

Analysis was done using Smith's Interpretative Phenomenological Approach. Themes and sub-themes were extracted and thematic schema was developed.

Results:

A total of 10 themes and 36 sub-themes were identified. The themes extracted with context to before being diagnosed with COVID-19 positive are impact of COVID-19 and preconception about hospitalization and hospitalized individuals. The themes with relation to active COVID-19 infection are psychological reactions, behavioral responses, positive experiences, negative experiences, stigma, coping strategies, and perceived needs. The theme re-adjustment with life was identified for postrecovery from COVID-19.

Conclusions:

COVID-19-positive individuals have myriad of experiences from their transition of being positive to finally being free of infection. Their experience with the illness sheds light on the gray areas like stigma that demand immediate attention. Future policies need to be developed in accordance with the identified perceived needs to potentially guide the satisfaction and recovery of COVID-19-positive individuals.

Keywords: Coping strategies, COVID-19-positive individuals, India, lived-in experience

INTRODUCTION

Globally, as of February 1, 2021, there have been 10,35,84,334 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 22,39,101 deaths, reported to the WHO,[1] whereas on the same date in India, there have been 1,07,58,619 confirmed cases of COVID-19 with 1,54,428 deaths and the infection rates continue to increase.[2] With no effective antiviral drugs and the countless cases of asymptomatic carriers moving around freely, traditional public health intervention measures fail to be the least bit effective.[3] Unemployment, isolation, and death embodies overwhelming stresses of this ghastly pandemic.[4] Doubled with that, COVID-19 has dragged along bizarre and inexplicable symptoms to many of its new hosts leading to chaos and worry.[5] The coining of new terms like “COVID toes” and “COVID tongues” further sends waves of fear and anxiety.[6,7]

As a consequence in the long run, enduring psychological problems in all the socioeconomic domains from rapidly expanding mass hysteria and panic regarding COVID-19 could potentially cause even more damage than the virus itself.[8] COVID-19 has made various changes in the coping strategies of people, let alone having an impact on people's emotions.[9] The clinical picture of COVID-19[10] is as complex as it's psychosocial impact.[11] Affected individuals have a wide range of experiential comments on being infected by the coronavirus and their fight for survival.[12,13] The sheer subjectivity of the illness experience demanded that each individual affected be heard and noticed.[14,15] This will aid in better understanding of the lived experiences of these individuals and the coping strategies employed at that time. The studies related to lived experiences are limited owing to the recency of the illness.

This study aimed at exploration of lived-in experiences and coping strategies used by patients diagnosed as COVID positive which could further provide basis for improvement in existing quality of care. In the Indian context, no such study has been conducted so far. Further, the evidence from this study will help to prepare well for future pandemics. The qualitative approach was used due to the lack of literature on the verbalized encounters of COVID-positive patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A hermeneutic phenomenological design was used for this study.[16] The study was conducted at a public funded tertiary care hospital in New Delhi, India. COVID-19-positive individuals who were admitted at the hospital and had recovered and were currently infection free were chosen to be the participants of the study.

Participant selection

Maximum variation purposive sampling was done to select participants of the study. The participants who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled for the study. Informed verbal consent was taken and recorded and a copy of written participant consent was taken through instant messaging service. Before commencing the study, permission was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Data collection

Subject data sheet was used to collect the demographic details of the study participants. Based on the objectives, an open-ended interview guide consisting of 20 questions was developed after literature search and consultation with experts. The interviews were conducted telephonically following two ice breaking sessions in view of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic. Probes were used as and when deemed necessary. The interviews took 35 min to 75 min for completion and were recorded using phone recorder. Data saturation was achieved by the 13th participant's interview, and hence, data collection was stopped following it. Data were transcribed, translated to English and then back to Hindi.

Data analysis

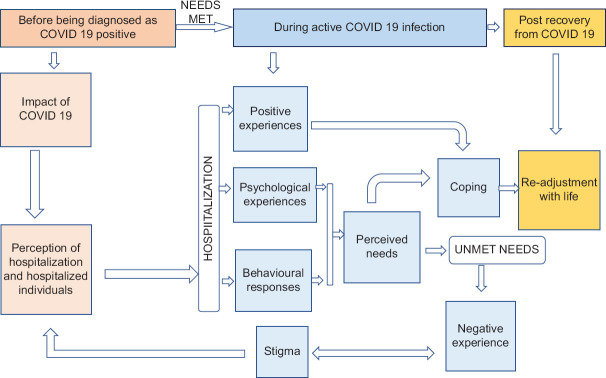

Data were analyzed using Smith's Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.[17] Member checks were done in an on-going fashion. Audit trail was also employed. After the generation of themes covering almost all aspects of the phenomenon, relationships between them were sought. The themes were then clustered to provide effective context to the participant responses and thematic schema [Figure 1] was developed.

Figure 1.

Thematic schema developed from lived-in experiences and coping strategies of COVID-positive patients

RESULTS

Out of the 13 participants, seven (53.85%) were male and six (46.15%) were female. The mean age of the participants was 37.77 ± years. The mean years of education were 11.46 ± years. Eight participants (61.60%) were married, four (30.77%) were unmarried, and one (7.69%) was widowed. Majority of the participants were Hindu which was about 11 participants (84.62%) and two participants (15.38%) were Muslim. The mean monthly family income was Rs. 34,846 ± 32,191. Eleven participants (84.62%) lived in urban area, whereas two participants (15.38%) lived in rural area.

Themes and sub-themes of the lived-in experiences and coping strategies of COVID-positive patients are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Themes and sub-themes derived from lived-in experiences and coping strategies of COVID positive individuals

| Section | Theme | Sub-theme | Verbatims |

|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1: Before being diagnosed with COVID-19 | Impact of COVID-19 Usage of masks which was restricted to hospitals now found its way to the remotest of villages. The ordinary human was fearful of touching alien surfaces like door handles and his very own skin and face, alike |

Precautionary behaviour | I used to watch about this knowledge on my TV and would move around by keeping all safety. Safety means sanitizer, mask on my face and would wear gloves on hands and move. I would follow complete safety measures (P5) |

| Fear of contracting illness | I used to be terrified. Due to this, I worked from home for 2 months. I did not use to come thinking of it (P3) | ||

| Perception of hospitalization and hospitalized individuals The fatality of COVID-19 caused ruckus as nations struggled to grapple the situation at hands, the affected population in one and widespread fear in other |

Negative view of hospitalization | My mindset was that they are pretty hard with the people they are admitting, they are not giving proper food to them and there is no proper facility for them and they are just in kind of a jail or prison, like that (P8) | |

| Shaping of perception by mass media | Before that I used to think that the treatment being given is not good enough because you know, the media and news channels are showing a negative picture about that. There was a doubt at the back of my mind whether the people who are being admitted will survive or not but I had seen on news that many people have recovered so I was emphasizing on that (P8) | ||

| Section 2: During active COVID-19 infection | Psychological reactions As soon as the results of the test are handed over, a psychological unrest commences. An individual would follow the regular Kubler-Ross pattern of grieving the news or they could mark a new trajectory of loss depending on the gravity of the situation |

Denial of having illness | I was thinking that the report might be false, I have no problems at all. How is it coming positive? (P13) |

| Skepticism regarding mode of acquiring infection | The only place where I used to frequent or kind of go to, you know, was to get home vegetable and all. So, I don’t know if I caught it from one of those guys or from somewhere else. That could be a possibility that I caught it from a vendor (P12) | ||

| Fear of transmitting infection | I was scared that my kids and husband will also have it since I was in touch with them (P11) | ||

| Uncertainty about survival | I would not think anything about myself but would think about my younger daughter that it’d be nice if I could get her married off while I am alive. If anything happens to me, what will she do. … I used to wonder about the future regarding my survival (P6) | ||

| Guilt and self-blaming | I started realizing that I have come in contact with everybody and I was very scared. I started feeling very bad, started feeling very guilty that I have come in contact with my friends and I did not even tell them that I am having all of this and if I wanted, I could have stopped if they came near me. They would have felt bad but I could have scolded them and made them go away so I felt like I should have done it at that time. Why did I come in contact with everybody? (P1) | ||

| Fear of exacerbation of infection and developing complications | I came to know that one of the patients there had come for 14 days but had been there for 1 month and 10 days. He was not discharged because his illness had not gone. I would think that this should not happen to me and I should not get more critical (P5) | ||

| Behavioural responses The sturdiest of men can cry, the calmest of women get angry. The anguish of having the illness along with its physical damage creates a myriad of human responses |

Crying | I felt like crying a lot and I was crying a lot (P1) | |

| Anger | They were talking about retrieving blood again. Are you understanding me? They were talking about retrieving blood again. I was very angry (P5) | ||

| Positive experiences A kind word, a gentle reminder of courage, a drop in fever or a less harsh cough, all seem worthy of reminding of life that still hasn’t loosened its grip. They seed hopes and courage back to the tired individuals giving them fresh perspective on life and all other things that life encapsulates |

Satisfaction with care | Food was very good. Such food is not even eaten at homes. I was given good and complete care at the hospital (P4) | |

| Supporters Healthcare personnel Family Friends and acquaintances |

The people around like doctors or serving staff or nursing staff are very friendly and very good (P8) Family members really helped me tide through this. They kept motivating me and giving me reassurance (P1) There is a friend that I have with whom I work. I mean, we go to duties together. My husband’s family was not here so she helped us a lot with respect to money (P11) |

||

| Improvement in health | They gave me Azithro and all and with that other things like my oxygen and all also improved but fever had gone on the 1st day itself (P12) | ||

| Negative experience Feeling ill is already an unfavourable experience and to add over it, isolation and being away from family members is the final straw. The mind is often taken over by one negative experience and all the good also ends in doom |

Being caged | I was made to leave. I was feeling like I have been freed out of a prison. I felt very restrained over there (P7) | |

| Unsettling events in the unit | I would see that there were many types of patients in the hospital so I would get a little anxious. If somebody would expire on the adjacent beds, I would also get worried (P7) | ||

| Delay in accessing care | It took a little time to get the papers made. It must have been around 3 or 3.5 h (P6) | ||

| Stigma With time, as COVID started gobbling the world, people started discriminating their immediate neighbours for having it. It is a sad state to be ill, away from loved ones, facing an uncertainty about life and instead of being cared for, being stigmatized |

Enacted stigma | One of the most important instances was that they asked the liftman and the newspaper vendor to not to go into my house or near my house because I was tested COVID positive. If they do so, they should not come to their houses. That was the first one. Second thing was that when I completed my isolation of 17-18 days their reaction was such that I was some kind of alien who is going to kill them. They stopped talking to me. Even my own relatives, they spread the rumor that I am very sick, my whole family is very sick (P9) | |

| Felt stigma | My family did not tell anyone. A note had been put on my gate regarding it but my family denied…. I did not tell my neighbours because my family asked to not to tell anyone… The fear was that nobody will come to our home or stay in touch with us or they will start differentiating (P8) | ||

| Courtesy stigma | People in my neighborhood raised objection and because of that negative report had to be shown to them that none of my family members had it and that they have already been tested. After seeing the report my neighbors became quiet and thought that there is no issue in talking or sitting with them (P5) | ||

| Coping strategies The mind adapts to a situation with time. The psychological instrument employs defense mechanisms to stabilize the disharmony |

Rationalization | I am not able to eat and drink properly, you know, I cannot have proper meals because I am not in the habit of taking breakfast so it could have happened because I used to be empty stomach (P11) | |

| Faith in God | At that time, I only had this one belief that the prayer that I am doing, God is hearing it. He is there with me. He will handle the situation slowly (P1) | ||

| Sharing problems with other patients | When I used to talk to the other lady who had also delivered a baby, I used to feel that at least I have someone here (P13) | ||

| Accepting reality | Even when I was tested positive, I was like okay, I have come positive (P9) | ||

| Staying occupied | I would keep using mobile phone and that would help me pass time. We would not get anything to read there so I would keep using my phone. Time would pass from the morning to evening doing all this stuff (P7) | ||

| Staying in touch with family and friends | To relieve stress, I would talk to my family members… I was in contact with my family members on the phone and on WhatsApp…I also videocalled my friends daily (P2) | ||

| Yoga and meditation | Every morning I used to do Yoga. The nurses told me that you should do anulom-vilom or simple pranayama if you are not feeling very agile (P9) | ||

| Perceived needs Individual needs are important to be addressed for optimum and faster recovery. With a pandemic like this on the loose, meeting needs becomes all the more important to prevent further damage to an already “in-pain” patient |

Need for counselling | If there is any patient so at that time even, I used to think that they are also in need and their family will also need to be made to understand at that time. Then patient also needs to be supported, of counselling, a mental support is needed at that time (P1) | |

| Need for acceptance by others | The most important thing is that there has to be support from the society so that we can de-stigmatize the disease (P9) | ||

| Need for information regarding illness and treatment | I think they should have talked about the illness but they do not do it usually. They keep treating on their own, you know, what has to be done and what should not (P7) | ||

| Need for frequent visits and communication by healthcare personnel | They should knock the door, at least the patient will be a little comfortable that even if the doctor has come or gone, at least he has seen (P3) | ||

| Section 3: Post recovery from COVID-19 | Re-adjustment with life Unlike other flu-like illnesses of the past, COVID does not give an opportunity to going back to the normal self. It leaves a remnant feeling, be it a nice one or a bad one |

Sense of triumph and getting a new life | I feel brave that I survived such a major illness (P7) |

| Re-experiencing the symptoms | Even now, sometimes I have difficulty in breathing, when I sit, I have to breathe fast so I relax completely for five minutes and then I get okay. There is a little cough even now and sometimes, even today the body temperature feels a little abnormal (P1) | ||

| Fear of re-infection and suspicion over others COVID status | I keep a sanitizer in my pocket. My family members made me buy a small bottle of it. I apply it after every 10-15 min and wash hands regularly. I am afraid that I might catch this infection again and this time I will not survive (P5) | ||

| Helping others going through similar situation | 2 months ago, around September I was being contacted by a person who is working in Income Tax. His father was in ICU and he needed a positive blood plasma. I had never met him. I went there after my job and I donated plasma. That was the day that I realized that even if COVID-19 happened, it happened for good (P9) |

ICU – Intensive care unit

DISCUSSION

Preconceived perception of negligence, compromised care, and confinement were voiced in this study. These views were either formed due to the exposure to mass media or due to accounts of other people living in their vicinity. A similar study from Pakistan found that individuals expressed their mistrust for hospitals and expressed that they could actually catch the infection from there despite being initially negative.[18] These concerns could effectively be mitigated by spreading awareness and increasing the transparency of care in COVID-19 care centers.

The initial phases of the infection were shrouded in confusion and uncertainty over the diagnosis. COVID-19-positive individuals had denial during the early stages of the disease. They would attribute their symptoms to other illnesses like cold. Some of them also had doubt regarding the test results and would think it is incorrect.[18] Some individuals had sign and symptoms which were inconsistent with that shown in the media and hence it led them to believe that they did not have the illness. Shock, sadness, panic/anxiety, and disbelief were the commonly reported first responses to the news of being diagnosed with COVID-19 positive. The thought of an impending death hung around like a boomerang.[19] An Indian narrative revealed a state of worry owing to evolving mortality statistics and a fear of passing the infection to family members and others in close contact. The dreaded state of being self-infected, isolation and a constant fear of dying and death of loved ones further aggravated the agony.[20] This infodemic concern was also reported in a study from Iran.[21] Feelings of guilt and anticipatory anxiety were also associated with it. Another study instituted that a constant psychological pressure to avoid harming their family members by transmitting them the infection, especially children and parents was very prominent among COVID-19-positive individuals. Some individuals gave it a higher pedestal than the stress of suffering from the infection itself. Similar findings were reported from a study in China where individuals were in rigorous search of a hospital bed to avoid familial transmission.[22] Death anxiety among the affected individuals posed with grave concerns regarding survival in the face of illness.[23,24] Majority of the COVID-19-positive patients experienced a fear of death when showing clinical symptoms. They showed concern regarding their prognosis as they questioned the treatment's effectiveness.[20] Similar findings were reported from China where individuals reported living with fear of death.[22] These issues could be addressed from the first point of contact with the individuals undergoing testing itself to somehow blunt the mental agony. These could follow protocols along the lines of HIV counseling.

Intrusive experience of guilt involving self-criticism could be maladaptive when reparation cannot be done for the behavior. Maladaptive guilt could pronounce the recurrent thoughts.[24] Individuals had psychological disturbances related to the exacerbation of condition and unpredictable complications due to the contradictory information making rounds all over the world.[22] This demands for holistic care of the affected with strong emphasis on myth busting and psychological supportive approaches.

Participants reported receiving support from healthcare personnel, family members, friends and acquaintances, and employers and colleagues which was unlike the experience of those affected in China who reported rejection from health-care workers and a sense of belittlement.[22] A study found that the care from the medical staff was the most important supportive factor reported by the COVID-19-positive individuals. This helped them to provide a sense of security and reliance on health-care personnel. Oriental studies also reiterated the good care provided by the hospital staff as an important factor for road to recovery. Support from family and friends in terms of their concern and encouragement was also found as a supportive factor.[20] This factor can be further utilized by the health-care personnel in forming a good working IPR with the affected and to allay their anxieties. The staff should be trained regarding COVID-19 specific mental health care and team based individualized care should be the focus.

COVID-19 experience was described as one of the bad phases in life by many of the study participants. Some went on to elaborate it further as the most horrible time of their lives.[19] Both Indian and oriental studies reported the feelings of sadness, uncertainty, worthlessness, and helplessness among the affected.[22,25,26] These individuals have dual burden of the illness and the stigma associated with it.[25] Multiple tags like “super-spreader” only worsens the agony.[25] Treatment facilities where COVID-19-positive patients were provided care were also discriminated.[27] All forms of stigma which are felt stigma, enacted stigma, and courtesy stigma were dominant. None of the individuals in this study reported not facing any form of stigma at all. The concerns ranged from facing discrimination on services of public utility to being cornered by own relatives and neighbours. Even families of affected individuals felt that others judged them on the basis of their loved one's positive status and were discriminated by the community members.[22,28] One of the participants even reported being denied to fill water from a common tap near her house. Hence, the stigma defied not only the dignity and self-esteem of the individual but also the basic constitutional rights of equality and freedom. The Indian findings unanimously corroborated with the Western and Oriental experiences of stigma making it a feeling that psychologically and emotionally tied all the infected individuals globally.[18,29] However, a similar study in the Indian context reports that anticipatory stigma had considerably decreased at the time of discharge.[19] This could be due to the decrease in perceived stigma as the individuals mingled with other COVID-19-positive patients throughout the hospital stay and the support received from health-care staff, friends, and family. Even then, there is a need for focussed de-stigmatization of the general population by providing correct information and addressing the commonly held misbeliefs in the community at large. The WHO and Government of India guide to address COVID-19-related stigma should be disseminated in regional languages to spread rightful and responsible behavior. Health-care personnel should be very vigilant about the mental health aspects of stigma and take corrective actions as soon as possible. They should also be responsible and avoid disclosing identity of the affected persons.

COVID-19-positive individuals had increased religiosity in view of their illness. The individuals looked for spiritual resources to free themselves of the infection.[19] The time in isolation provided these individuals to re-instil their belief in God and reflect upon their life.[21] Both the Indian and Chinese studies found that the affected were enormously resilient and hoped for a better future.[22] Submission to a higher power could have decreased worries and fears and visible signs of recovery could have led to further strengthening of faith.

Talking to friends and family members, exercising, meditating, surfing internet, and watching movies were also used as coping mechanisms. Affected individuals also reported shouting on others who they conceived as infection spreaders to self, health-care workers and on self to vent out pooled emotions.[19] Need for mental health counselling for both the COVID-19-positive individuals and their family members was reported in order to relieve anxiety associated with the illness, its course, treatment, and outcome. COVID-19-positive individuals require support by mental health professionals. This should be included to provide all round care to these individuals and to prevent severe untoward consequences as a result of their distress.[30] The individuals affected with COVID-19 expected more information regarding their illness, treatment, and prognosis from the health-care team. Furthermore, the information should not be provided to the family members alone and the patient should be kept in the loop regarding his condition. Even though, the discharge from the hospital, travelling back home and reaching home were expressed as the most valuable experiences of the COVID-19 journey,[19] a study done in Indian setting found that at the time of discharge, at least 38% of the affected individuals screen positive for anxiety or depression. These concerns are grave and need immediate remediation through well-planned follow-ups.[19] In this study as well as others, individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 had lingering fears of being re-infected postdischarge and expressed major concerns over it.[21] These concerns can be addressed in the form of discharge counselling or follow-ups. Designated helplines to address post COVID-19 issues can also be initiated by hospitals and government.

Despite ongoing concerns, these recovered individuals were willing to help others by donating plasma in the near future. This was also consistent with a similar study done in China.[22] This act of generosity and charity is deep rooted within the tumultuous experience of the illness and gave a sense of purpose to the recovered individuals. The simple act of giving back to society and easing the difficult situation of other individuals suffering from COVID-19 is seen as an act of defiance against those who stigmatize the illness.

In a nutshell, the individuals began their journey with the infection in a confused, worried, fearful stage, and slowly advanced to the positive aspects of resilience, hope and generosity. Health-care personnel and hospitals can tap on the key needs raised by the individuals in this study to decrease the transit time to recovery. It could also guide the administration in policy making and initiating a more COVID-19 patient friendly unit.

There are certain limitations in this study which are that the study was limited to a single centre. Participants were interviewed postrecovery from the infection, and hence, there may have been recall bias. Owing to it, few experiences might have been missed. Telephonic interview could not elicit nonverbal information.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Rachna Bhargava, Dr. Raminder Klara, Dr. Bichitra Nanda Patra, Dr. Siddharth Sarkar, Mr. Jason Joseph, Mrs. Xavier Belsi, Mr. Jithin Thomas Parel, Mrs. Rashmi Rawat and Ms. Merin Thomas for their valuable suggestions and guidance throughout this study. We also thank all the study participants for their consent and precious time devoted for this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 19]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.India: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 19]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/searo/country/in .

- 3.Sun J, He WT, Wang L, Lai A, Ji X, Zhai X, et al. COVID-19: Epidemiology, evolution, and cross-disciplinary perspectives. Trends Mol Med. 2020;26:483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shader RI. COVID-19 and depression. Clin Ther. 2020;42:962–3. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staines M. “I’m Just Very Frightened” – Patients Say HSE has “no Strategy” for Treating Long-COVID. Newstalk. [Last acessed on 2021 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.newstalk.com/news/patients-say-hse-has-no-coherent-strategy-fortreating-long-covid-symptoms-1136732 .

- 6.COVID Symptoms | All You Need to Know about “COVID Tongue” – The Newest Symptom of COVID-19 Disease, as Per Experts | Health Tips and News. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.timesnownews.com/health/article/all-you-need-to-know-about-covid-tongue-the-newest-symptom-of-covid-19-disease-as-per-experts/709517 .

- 7.Covid Toes: Somerset Mum Warns Parents about Strange Symptom – Somerset Live. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.somersetlive.co.uk/news/somerset-news/covid-toes-somerset-mum-warns-4845261 .

- 8.Depoux A, Martin S, Karafillakis E, Preet R, Wilder-Smith A, Larson H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27:taaa031. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang L, Lei W, Xu F, Liu H, Yu L. Emotional responses and coping strategies in nurses and nursing students during COVID-19 outbreak: A comparative study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts MC, Levi M, McKee M, Schilling R, Lim WS, Grocott MP. COVID-19: A complex multisystem clinical syndrome. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 24];BMJ. 2020 125:238–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.013. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/05/01/covid-19-a-complex-multisystem-clinical-syndrome/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19. [Last acessed on 2021 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7255207/

- 12.Sastry AK. Recovered COVID-19 Patient Shares His Experience. The Hindu. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Mangalore/recovered-covid-19-patient-shares-his-experience/article31394243.ece .

- 13.DelhiApril 11 ITWDN, April 11 2020UPDATED: Ist 2020 14:18. Coronavirus: What 6 Indian Survivors Want You to Know about Fighting COVID-19. India Today. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/coronavirus-what-6-indian-survivors-want-you-to-knowabout-fighting-covid-19-1665758-2020-04-11 .

- 14.My COVID Story: “We Were Positive and we Didn’t Know from Where” – Times of India. The Times of India. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 23]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/health-fitness/health-news/mycovid-experience-we-were-positive-and-we-didnt-know-from-where/articleshow/78655526.cms .

- 15.My COVID-19 Experience – By Mukul Kesavan. [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.ndtv.com/opinion/my-covid-19-experience-by-mukulkesavan-2255638 .

- 16.Smith JA, Osborn M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. Br J Pain. 2015;9:41–2. doi: 10.1177/2049463714541642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun N, Wei L, Wang H, Wang X, Gao M, Hu X, et al. Qualitative study of the psychological experience of COVID-19 patients during hospitalization. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansoor T, Mansoor S, Bin ZU. “Surviving COVID-19”: Illness narratives of patients and family members in Pakistan. Ann KEMU. 2020;26:157–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahoo S, Mehra A, Dua D, Suri V, Malhotra P, Yaddanapudi LN, et al. Psychological experience of patients admitted with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102355. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahoo S, Mehra A, Suri V, Malhotra P, Yaddanapudi LN, Dutt Puri G, et al. Lived experiences of the corona survivors (patients admitted in COVID wards): A narrative real-life documented summaries of internalized guilt, shame, stigma, anger. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102187. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moradi Y, Mollazadeh F, Karimi P, Hosseingholipour K, Baghaei R. Psychological disturbances of survivors throughout COVID-19 crisis: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:594. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-03009-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W, Liu J. Living with COVID-19: A phenomenological study of hospitalised patients involved in family cluster transmission. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046128. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahmatinejad P, Yazdi M, Khosravi Z, Shahisadrabadi F. Lived experience of patients with coronavirus (COVID-19): A phenomenological study. J Res Psychological Health. 2020;14:71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahoo S, Mehra A, Suri V, Malhotra P, Yaddanapudi LN, Puri GD, et al. Lived experiences of COVID-19 intensive care unit survivors. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42:387–90. doi: 10.1177/0253717620933414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavalera C. COVID-19 psychological implications: The role of shame and guilt. Front Psychol. 2020;11:571828. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.571828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacharya P, Banerjee D, Rao TS. The “Untold” side of COVID-19: Social stigma and its consequences in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42:382–6. doi: 10.1177/0253717620935578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmud A, Islam MR. Social stigma as a barrier to COVID-19 responses to community well-being in Bangladesh. Int J Community Well-Being. 2020;8:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s42413-020-00071-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:782. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ladds E, Rushforth A, Wieringa S, Taylor S, Rayner C, Husain L, et al. Persistent symptoms after COVID-19: Qualitative study of 114 “long Covid” patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1144. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-06001-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaban RZ, Nahidi S, Sotomayor-Castillo C, Li C, Gilroy N, O'Sullivan MV, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19: The lived experience and perceptions of patients in isolation and care in an Australian healthcare setting. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:1445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]