Abstract

During the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the British Cardiovascular Society/British Cardiovascular Intervention Society and the British Heart Rhythm Society recommended to postpone non-urgent elective work and that primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should remain the treatment of choice for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). We sought to determine the impact of COVID-19 on the primary PCI service within the United Kingdom (UK).

A survey of 43 UK primary PCI centres was performed and a significant reduction in the number of cath labs open was found (pre-COVID 3.6±1.8 vs. post-COVID 2.1±0.8; p<0.001) with only 64% of cath labs remained open during the COVID-19 pandemic. Primary PCI remained first-line treatment for STEMI in all centres surveyed.

Key words: acute myocardial infarction, healthcare delivery, medical education, percutaneous coronary intervention

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 12th March 2020.1 Subsequently, on 20th March 2020, the National Health Service (NHS) England in collaboration with the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS), the British Cardiovascular Interventional Society (BCIS) and the British Heart Rhythm Society (BHRS) published guidelines for the management of cardiology patients during the coronavirus pandemic.2 Briefly, the guidelines recommended that:

all non-urgent elective inpatient/day case procedures should be postponed

primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should continue to be the default treatment for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) while thrombolysis could be considered in selected patients with COVID-19

non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) pathways should continue where possible but PCI could be performed instead of surgery for multivessel disease and optimal medical therapy alone could be considered in lower risk NSTEMI patients.

In a subsequent BCS/BCIS/BHRS update it was recommended that primary PCI should be considered an aerosol-generating procedure and, hence, full personal protective equipment (PPE) should be donned and appropriate precautions undertaken.3

The implications for PCI centres across the United Kingdom (UK) tasked with implementation of these guidelines should not be underestimated. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic poses a number of potential risks for patients with cardiovascular disease.

First, there may be delays in the treatment of STEMI caused by the additional step of assessing COVID-19 risk prior to primary PCI, delays in ensuring cath lab staff are wearing adequate PPE in suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients and/or delays in ambulance transfer.

Second, there may be an increased use of thrombolysis for STEMI patients resulting in worse outcomes and longer hospital length of stay

Third, there may be significant reductions in cardiac catheter laboratory (cath lab) utilisation due to cancellation of elective work, delays caused by deep cleaning of labs in between cases and/or staff sickness.

Fourth, interventional cardiologists may experience an increased workload caused by an increased volume of complex PCI and structural interventions (as cardiac surgery has been reduced to maximise intensive care bed availability) and a reduction in the workforce due to self-isolation policies. In addition, there may be a detrimental impact on training with reduced training opportunities for cardiology trainees.

There is currently no data available on the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on primary PCI centres in the UK. We aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiac cath lab activity at primary PCI centres across the UK.

Methods

A survey of primary PCI centres across the UK was conducted between 15th – 22st April 2020. Information on these centres was obtained from cardiology trainees working at these centres via social media and/or email. The following information was requested:

name of hospital

tertiary centre or district general hospital (DGH)?

primary PCI centre?

how many cardiac catheter labs were open pre-COVID-19?

how many cardiac catheter labs are open now?

do you have a separate ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ lab?

is primary PCI still first line treatment for STEMI?

Only those centres which perform primary PCI were included. A cardiothoracic centre (CTC) was defined as having cardiac surgery based on information from the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 25. Data represented as mean±standard deviation (SD) (for continuous variables) or frequency (%) for categorical data. The proportion of cardiac cath labs open post-versus pre-COVID-19 was calculated (%). Continuous variables were tested for normality using Kolmogorov-Smirnov. Group comparisons were tested using Wilcoxon rank test, chi-squared test and Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All primary PCI centres

Responses from 54 hospitals were screened. Eleven hospitals were excluded as they were DGHs that did not perform primary PCI. In total, data from 43 primary PCI centres were included representing 63% of the 68 primary PCI centres in the UK.4 There were 28 CTCs (68%) and 15 DGHs (35%) in England (n=35), Scotland (n=3), Wales (n=3) and Northern Ireland (n=1).

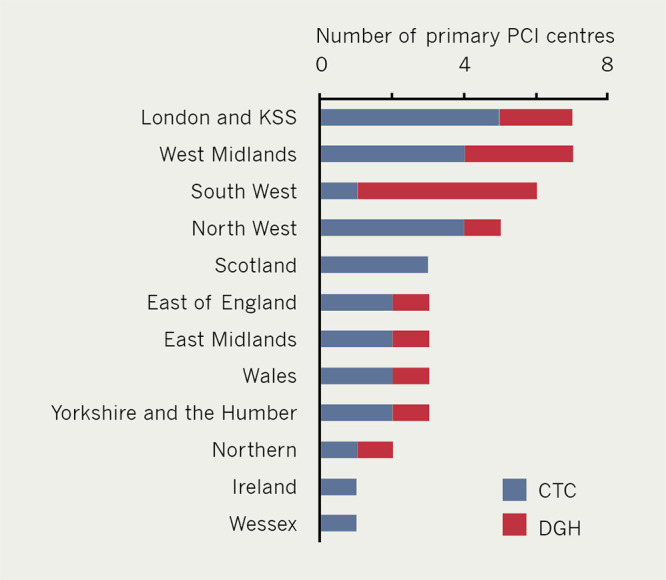

Primary PCI centres from 12 of 13 (92%) UK cardiology training deaneries were included in the survey (figure 1).

Figure 1. Bar chart showing the number of primary PCI centres who responded according to UK Cardiology Speciality Training Deanery.

Key: CTC = cardiothoracic centre; DGH = district general hospital; KSS = Kent Surrey and Sussex; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention

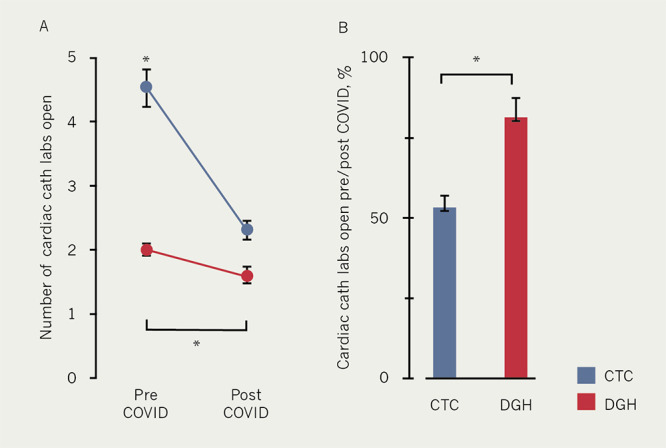

There was a significant reduction in the number of cath labs open (pre-vs. post-COVID-19 3.6±1.8 vs. 2.1±0.8, respectively; p<0.001) (figure 2). Across the UK, 64% of cath labs remained open during the COVID-19 crisis. Most centres adopted a separate ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ cath lab (79%). One centre reported that all cath labs were considered ‘dirty’ and hence they did not have a separate ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ cath lab. Primary PCI remained first-line treatment for STEMI in all centres.

Figure 2. A: line chart showing the mean±SEM number of cardiac cath labs open pre- and post-COVID according to primary PCI centre type B: bar chart showing the percentage of cardiac cath labs open (pre-/post-COVID) according to primary PCI centre type.

Key: COVID = coronavirus disease; CTC = cardiothoracic centre; DGH = district general hospital; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; * p<0.005

CTC versus DGH primary PCI centres

As expected, CTCs had more cath labs pre-COVID-19 compared to DGHs (p<0.001), and the number of cardiac cath labs was significantly reduced in both CTCs (pre-vs. post-COVID-19 4.5±1.6 vs. 2.4±0.8, respectively; p<0.001) and DGHs (pre-vs. post-COVID-19 2.0±0.4 vs. 1.6±0.5 respectively; p=0.014). The relative reduction in cardiac cath labs was more pronounced in CTCs compared to DGHs (% cath labs open post-/pre-COVID in CTC vs. DGH 53±19% vs. 81±24%, respectively; p=0.003). The proportion of primary PCI centres with separate ‘dirty’ cath labs was higher in CTCs but this did not reach statistical significance (CTC vs. DGH 86% vs. 67%, respectively; p=0.143).

Discussion

The results of the present survey confirm that the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent health service response has caused a significant impact on cardiac cath lab activity in primary PCI centres in the UK. It is reassuring that at the time of the survey, primary PCI remained the first-line treatment for STEMI across the UK. Most centres employ a separate ‘dirty’ cath lab, which may improve the flow of patients and minimise treatment delays.

The reduction in the number of cardiac cath labs open is likely due to cessation of elective work, although there may be other reasons including reduction in staffing (i.e. due to sickness or social isolation policies) and/or reductions in hospital attendances.5 The reduction in cath labs was greater within CTCs (46% reduction) compared to DGHs (19% reduction), which is likely to reflect reductions in non-urgent interventions (e.g. complex devices, electrophysiology studies and ablation, structural heart disease) which are more commonly performed in tertiary CTCs.

The results of this survey suggest that non-urgent elective work constitutes a significant proportion of cardiovascular interventional procedures within the UK. Such a dramatic reduction in cardiac cath lab activity may have significant consequences for patient care and if sustained may pose a risk to many patients with cardiovascular disease.

Training

There have been concerns raised regarding the impact of COVID-19 on cardiology training.6 While there has been a rise in virtual education during COVID-19,7 the reduction in cath labs may impact negatively on practical skills training for interventional trainees (i.e. PCI, electrophysiology, devices). The following measures may help minimise the impact: restructuring rotations to facilitate increased cardiac cath lab exposure within tertiary and DGHs in the region; extensions to training programmes; and increasing availability of simulation training.8,9 Further work is required to assess the impact of COVID-19 on cardiology training.

Limitations

There are a number of important limitations associated with the study design. Surveys are inherently subject to bias (e.g. response bias, selection bias). Although the survey did not capture all primary PCI centres in the UK, data was collected from almost two thirds of all such centres which we believe is sufficiently reflective of UK practice. The present survey did not include data from non-primary PCI cath labs which would be useful to assess the impact of COVID-19 on overall cath lab activity. Further study is warranted to determine whether there was a significant uptake of starting primary PCI within these labs. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic is rapidly evolving hence these results only reflect practice for the time period of the survey.

In conclusion, this survey suggests a significant reduction in cardiac cath lab utility in primary PCI centres since the COVID-19 pandemic and almost universal adherence to the NHS England recommendations to cancel non-urgent elective work. Further work is required to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the management of acute myocardial infarction as well as cardiology speciality training within the UK

Key messages

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) has significantly impacted the management of patients with cardiovascular disease worldwide

The British Cardiovascular Society/British Cardiovascular Intervention Society and British Heart Rhythm Society recommended to postpone non-urgent elective work and that primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should remain the treatment of choice for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) during the COVID-19 pandemic

This survey provides data showing that cardiac cath lab activity within primary PCI centres in the UK has been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic with a 36% reduction in the number of open cath labs. A greater reduction in cath lab utility occurred within cardiothoracic centres compared to district general hospitals and is likely to reflect a reduction in non-urgent elective work

Reassuringly, this study provides evidence that despite the COVID-19 pandemic primary PCI was still considered first-line treatment for STEMI in all the centres surveyed

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Study approval and consent

Ethical approval was not required as this survey constitutes a quality improvement in healthcare and did not involve human participants. Consent was therefore not required.

Editors’ note

This article first appeared online in the third of our bulletins COVID-19: clinical practice during the pandemic.

An editorial by Professor Nick Curzen on this topic can be found on pages 49-50.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Contributor Information

Ahmed M Adlan, Senior Cardiology Fellow in Electrophysiology and Devices North West Heart Centre, Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Southmoor Road, Manchester, M23 9LT.

Ven G Lim, Cardiology Specialist Registrar University Hospital, University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire NHS Trust, Clifford Bridge Road, Coventry, CV2 2DX.

Gurpreet Dhillon, Cardiology Specialist Registrar St George’s Hospital, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Blackshaw Road, London, SW17 0QT.

Hibba Kurdi, Cardiology Specialist Registrar Morriston Hospital, Swansea Bay University Health Board, Heol Maes Eglwys, Swansea, SA6 6NL.

Gemina Doolub, Cardiology Specialist Registrar Southmead Hospital, North Bristol NHS Trust, Southmead Road, Westbury-on-Trym, Bristol, BS10 5NB.

Nadir Elamin, Cardiology Specialist Registrar Northern General Hospital, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Herries Road, Sheffield, S5 7 AU.

Amir Aziz, Cardiology Specialist Registrar Heartlands Hospital, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Bordesley Green East, Birmingham, B9 5SS.

Sanjay Sastry, Consultant Interventional Cardiologist North West Heart Centre, Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Southmoor Road, Manchester, M23 9LT.

Gershan Davis, Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, PR1 2HE.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . [Published online 2020]. [last accessed 26th May 2020]. WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS England . [Published online 2020]. [last accessed 26th May 2020]. Clinical guide for the management of cardiology patients during the coronavirus pandemic.https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/specialty-guide-cardiolgy-coronavirus-v1-20-march.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.British Cardiovascular Society British Cardiovascular Interventional Society and British Heart Rhythm Society . [Published online 2020]. [last accessed online 26th May 2020]. BCS, BCIS & BHRS Response to PHE Updated Guidance on PPE.https://www.britishcardiovascularsociety.org/news/guidance-ppe-phe [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) 2019 summary report (2017/18 data) [Published online 2019]. [last accessed 26th May 2020]. National Audit For Percutaneous Coronary Intervention.https://www.hqip.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Ref-129-Cardiac-NAPCI-Summary-Report-2019-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS England . [Published online 2020]. [last accessed 26th May 2020]. A&E attendances and amergency admissions 2019–20.https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ae-waiting-times-and-activity/ae-attendances-and-emergency-admissions-2019-20/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board . [Update published 16th March 2020]. [last accessed 26th May 2020]. COVID-19 and recognition of trainee progression in 2020.https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/news/covid-19-and-recognition-trainee-progression-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almarzooq ZI, Lopes M, Kochar A. Virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a disruptive technology in graduate medical education. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2635–2638. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeFilippis EM, Stefanescu Schmidt AC, Reza N. Adapting the educational environment for cardiovascular fellows-in-training during the COVID-19 pandemic. [published online May 2020];J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 75 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison CM, Gosai JN. Simulation-based training for cardiology procedures: Are we any further forward in evidencing real-world benefits. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2017;27(3):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]