Abstract

Adolescence is a sensitive developmental period marked by significant changes that unfold across multiple contexts. As a central context of development, neighborhoods capture—in both physical and social space—the stratification of life chances and differential distribution of resources and risks. For some youth, neighborhoods are springboards to opportunities; for others, they are snares that constrain progress and limit the ability to avoid risks. Despite abundant research on “neighborhood effects,” scant attention has been paid to how neighborhoods are a product of social stratification forces that operate simultaneously to affect human development. Neighborhoods in the United States are the manifestation of three intersecting social structural cleavages: race/ethnicity, socioeconomic class, and geography. Many opportunities are allocated or denied along these three cleavages. To capture these joint processes, we advocate a “neighborhood-centered” approach to study the effects of neighborhoods on adolescent development. Using nationally representative data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), we demonstrate the complex ways that these three cleavages shape specific neighborhood contexts and can result in stark differences in well-being. A neighborhood-centered approach demands more rigorous and sensitive theories of place, as well as multidimensional classification and measures. We discuss an agenda to advance the state of theories and research, drawing explicit attention to the stratifying forces that bring about distinct neighborhood types that shape developmental trajectories during adolescence and beyond.

1. INTRODUCTION

Neighborhoods are central social settings for organizing and experiencing human life. In this chapter, we focus on youth, whose lives are constrained by the housing and neighborhood choices of their parents and are more geographically bound than adults. The growing need for autonomy during adolescence increases the amount of time adolescents spend outside of their home, typically with peers, and often in neighborhoods that provide the physical and social space within which much interaction occurs (Leventhal, Dupéré, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). Extensive scholarship has linked neighborhood contexts—particularly their socioeconomic characteristics—to various domains of youth development and well-being: violence and delinquency, substance use, sexual activity, child-bearing, high school drop-out, educational attainment, employment, and physical and mental health (e.g., Dupéré, Leventhal, Crosnoe, & Dion, 2010; Leventhal et al., 2009; McBride Murry, Berkel, Gaylord-Harden, Copeland-Linder, & Nation, 2011).

Inequalities are readily observed in the physical properties of neighborhoods that reflect and reinforce the existing stratification of social groups whose members have differential access to resources, power, status, and prestige (McLeod, 2013; Squires & Kubrin, 2005; Sundstrom, 2003, p. 84). Thus, the processes that occur in these settings generate—and are sometimes meant to compensate for—problems of social stratification. That is, the social and economic characteristics of youth and their families result in a set of risks and resources that can stem from or interact with their neighborhood environments. Youth and their families are changing over time, but so too are the neighborhoods in which they are located, creating a kind of “dynamism” of shifting opportunities and constraints. Neighborhoods are a primary setting within which life course transitions occur and life trajectories are situated.

US neighborhoods, our focus, are largely shaped by the intersection of three key structural “cleavages”: race/ethnicity, social class, and geography.a Neighborhoods are where these cleavages are most visibly “etched in place” (Sampson, 2012, p. 19), resulting in complex neighborhood “types” defined by “profiles” of characteristics, such as those implied by the terms “distressed,” “privileged,” or “bad” neighborhoods (Leicht & Jenkins, 2007). Yet, traditional “neighborhood effects” research has generally focused on single items (e.g., percent Black) or indices (e.g., of concentrated disadvantage) related to the demographic and/or economic composition of neighborhoods.

Although this work has been instrumental in identifying some of the place-based characteristics that influence development, such a “variable-centered” (Weden, Bird, Escarce, & Lurie, 2011) approach treats the structural cleavages superficially and as if they are independent, thereby ignoring their intersections (Choo & Ferree, 2010) and neglecting how they are complex latent aspects of social structure (Diez Roux & Mair, 2010; Ferraro, Shippee, & Schafer, 2009). These three structural cleavages, independently and jointly, are already powerfully associated with individuals’ life chances (McLeod, 2013), reflecting larger social forces such as discrimination, segregation, stratification, and inequality—processes that systematically put certain social groups at an economic or social disadvantage (Braveman, 2014). This is consistent with an “intersectionality” perspective, which underscores the need to probe the meaning and consequences of multiple categories of difference and disadvantage (McCall, 2005), divisions that are often enmeshed and not reducible to each other (Yuval-Davis, 2006).

In this chapter, we aim to advance theories and measures of neighborhoods as a key developmental context, particularly for youth, via three primary goals. First, we briefly establish adolescence as a key developmental period that unfolds across multiple contexts, with neighborhoods being a focal context. We then provide an overview of the state of research on neighborhood effects and describe the advantages of bridging current approaches with more macrosociological stratification theories in order to illuminate the three structural cleavages noted earlier and to generate an integrated perspective.

Second, we outline how a “neighborhood-centered” approach offers an alternative and effective means for studying the effects of neighborhoods on adolescent development and trajectories into adulthood. This approach permits the simultaneous consideration of multiple forms of inequality and a relational, comparative investigation of neighborhoods.

Third, to demonstrate the power of a neighborhood-centered approach, we draw on data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) to examine how trajectories of violent victimization during adolescence and into young adulthood differ across neighborhood types, and how neighborhoods shape victimization behaviors directly and indirectly.

2. ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT AND THE LIFE COURSE: AN ORIENTING NOTE

Adolescence is a sensitive developmental period marked by significant biological, physiological, psychological, and social changes. It is characterized by increasing independence from parents and family, salience of friendships and peer groups, exploration of identity, and experimentation with a wide range of behaviors, some of which can be risky (e.g., Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006). Scholarship on adolescent development has been consistently attuned to matters of risk and resilience that accompany this period and to the early causes and later consequences of youth outcomes.

The evolution of the life course perspective in recent decades has been particularly influential in generating sensitivity to how individual lives unfold over time and within personal and social environments (for an overview, see Elder, Shanahan, & Jennings, 2015; Kohli, 2007; Mayer, 2004). It has especially turned attention to how social structure and historical time impinge on human lives, and how individuals orient themselves to the opportunities and constraints they face, expressing their “agency” within the confines of “structure” (Settersten & Gannon, 2005). In emphasizing the embeddedness of developmental experiences in time and place, the life course perspective resonates with developmental perspectives such as Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) social ecological theory and relational developmental systems theories (e.g., Lerner, Lerner, & Benson, 2011), all of which underscore the fact that individual development is nested within multiple, mutually reinforcing, and transactional contexts.

Although neighborhoods have been acknowledged in both developmental and life course scholarship, they warrant much greater attention, as they are far more than background factors or simple stages on which lives unfold (Sampson, 1993). To that end, we first discuss the emergence of “neighborhood effects” research, tracing it to where it is today and advocating for methods that enhance and extend existing research.

3. THE NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT OF ADOLESCENCE: HOW NEIGHBORHOODS WORK

3.1. A Brief History of Sociological Scholarship on Neighborhood Effects

Serious attention to persons in places—and to the influence of place on human development—can be traced to the early contextual thinkers of the Chicago School (particularly, Burgess, 1925; Park, 1936; Wirth, 1945). These scholars were concerned with understanding everyday human life in relation to the social world, and they used human ecology as the guiding framework for identifying the social forces that organize persons and institutions in a given social space (Gross, 2004). In one of the earliest uses of the term “human ecology” in sociology, McKenzie (1924, p. 288) defined it as “a study of the spatial and temporal relations of human beings as affected by the selective, distributive, and accommodative forces of the environment… [it] is fundamentally interested in the effect of position…” (emphasis added), as place involves both geographic location and social station (Sundstrom, 2003, p. 84).

The Chicago School also recognized that individuals cannot be separated from the social structures and geographical locations of which they are part (Snell, 2010, p. 59). The clustering of social problems in a neighborhood or area was therefore interpreted as a sign of concentrated social disorganization. Several consistent risk factors emerged as common characteristics of urban neighborhoods plagued with high rates of various social problems, particularly crime and deviance: population size and density, racial/ethnic heterogeneity, socioeconomic status (SES), residential mobility, mixed land use, and dilapidation. The revelation was that social problems are not randomly distributed.

Among the early research linking place and risk specifically for youth was Shaw and McKay’s (1942) study of juvenile delinquency rates in Chicago between 1927 and 1933. Much of the research on neighborhood effects in sociology and criminology owes its origins to this work. After observing the persistence of high juvenile delinquency rates in certain neighborhoods over time, Shaw and McKay (1942) concluded that neighborhood juvenile delinquency rates were caused by some properties of the neighborhood as a whole, not simply by the characteristics of individual residents. For both Blacks and Whites, juvenile delinquency rates declined with growing distance from the city center. One core explanation related to the invasion of industry into particular central city neighborhoods, which made these areas less desirable for residents and led to decreasing population as economically able residents migrated out. The loss of population undermined social order and social organization, thus leaving the neighborhood vulnerable to disorder and deviance. In what came to be known as the theory of social disorganization, Shaw and McKay argued that low SES, racial/ethnic heterogeneity, and residential mobility undermined social organization—and were the gateway to delinquent subcultures and behaviors.

3.2. A Shift to Processes and Mechanisms

The research of the Chicago School prompted a shift away from individual-based theorizing to place-based theorizing about social problems and other indicators of life chances, health, and well-being. Social disorganization theory has since been expanded by many scholars (e.g., Bursik, 1988; Sampson & Groves, 1989; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002) and is now largely understood as capturing the inability of a community to realize the common values of its residents and maintain effective social control (Sampson & Groves, 1989). The urban ecologists of the Chicago School provided a critical foundation for current research in which neighborhoods are hypothesized to affect individual and group outcomes through positive and negative social mechanisms. Positive mechanisms include social capital, control, solidarity, cohesion, networks, resources, and a commitment to the “common good.” Negative mechanisms include social disorder, isolation, and resource and opportunity deprivation.

Three additional theoretical developments since the Chicago School have been instrumental in advancing neighborhood effects research to its current state. These are exemplified in the work of William J. Wilson, Christopher Jencks and Susan Mayer, and Robert Sampson and his colleagues, respectively. First, Wilson’s (1987) The Truly Disadvantaged has informed much research on how neighborhoods affect children, youth, and families—especially in identifying the concentration of poverty in urban areas as a major culprit and linking it to the outmigration of middle-income residents from mixed-income inner-city neighborhoods and the loss of manufacturing jobs in those areas. Remaining residents became trapped in highly impoverished neighborhoods with few or no opportunities or resources.

Second, Jencks and Mayer (1990) identified some of the processes through which neighborhoods are expected to exert their influence on residents, particularly children and adolescents. This research created a foundation for understanding how neighborhoods “work.” Structural characteristics (e.g., neighborhood SES, racial/ethnic heterogeneity, residential mobility) influence development via processes captured in distinct models: collective socialization, institutional, social comparison, and epidemic/contagion.

Collective socialization or social interaction models focus on the presence (or absence) of prosocial adult role models for children—for instance, the protective effect of “old heads” who provide informal social control in the community (Anderson, 2013), or of parents’ social networks and/or ties to children’s friends and families that are critical for monitoring and supervising children (Coulton & Spilsbury, 2014). Institutional models emphasize both the quality and regulatory capacity of social institutions, such as schools and law enforcement agencies. They also capture how processes of economic and racial segregation deprive certain neighborhoods of resources needed for schools, child care centers, youth development programs, parks and recreational centers, medical care, social services, and other child-serving institutions (Coulton & Spilsbury, 2014). Social comparison models emphasize the detrimental consequences of (perceptions of) deprivation or competition relative to others, including more affluent neighbors, which may lead to subcultural adaptations and conflict (as observed in Anderson’s (1999) account of inner city youth).

Epidemic/contagion models highlight the power of peers—youths’ immediate friends and more distant age-mates—in the transmission of norms through networks and communities. Social isolation and neighborhood disorganization create a context within which certain norms and behaviors that counter those shared by the majority of residents develop and crystallize, creating a subculture that threatens social order (Anderson, 1999). The notion that disadvantaged neighborhoods foster problem behaviors by exposing youth to a greater number of peers who are engaged in and provide opportunities for problem behaviors is nicely illustrated in Osgood and Anderson’s (2004) application of routine activities theory. They showed that adolescents who were exposed to environments where youth spent a majority of time engaged in unstructured socializing (away from shared parental and community monitoring) had more, and more significant, problem behaviors. Similarly, bridging the logic of institutional and epidemic models, Thomas and Shihadeh (2013) found that areas where youth were institutionally disengaged—not in school, the labor force, or the military—had higher crime rates because these idle youth (compared to those who were institutionally engaged) were freer to drift into deviance since they lacked the social bonds needed to keep them from acting on deviant opportunities or impulses.

Third, the work of Sampson and colleagues has explicitly targeted the capacity of adults to regulate the behaviors of children and youth in their community. Sampson’s theorizing emphasizes the role of neighborhood organization in facilitating (or inhibiting) the development of social capital, control, and cohesion. Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls (1997) further refined this by advancing the concept of “collective efficacy,” which is comprised of cohesion among residents, social control of public space, and willingness to intervene for the common good. Thus, the role of the neighborhood transcends particular interpersonal ties because it reflects a larger shared commitment among residents. Accordingly, neighborhood characteristics, particularly neighborhood poverty, can be linked to neighborhood-level social problems because poverty undermines collective efficacy; that is, poverty undermines the regulatory capabilities of residents.

3.3. The Indirect Effects of Neighborhoods: The Role of Other Contexts

In addition to the direct effects of neighborhoods on development, neighborhoods also have indirect effects that operate through and/or interact with other key contexts (Cook, Herman, Phillips, & Settersten, 2002; Leventhal et al., 2009). In fact, the long-term consequences of community context may be largely indirect (Wickrama & Noh, 2010). Particularly relevant for adolescents are neighborhood effects on family, school, and peer domains. For instance, stress process research finds that neighborhood disadvantage leads to parents’ physical, psychological, and emotional distress, which contributes to parental hostility, harsh parenting, and compromised parent–child relationships (Leventhal et al., 2009). Conflicting results exist regarding the effect of neighborhood context on parental monitoring, with some studies showing that disadvantage undermines monitoring, while others show that it increases monitoring (see Antonishak & Reppucci, 2008). Neighborhoods also shape and structure the types of peers to whom young people are exposed (Haynie, 2001). Youth who grow up in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to be exposed to deviant peers, which increases their risk of engaging in risky behaviors themselves (Cantillon, 2006), particularly in neighborhoods with few opportunities for prosocial activity (Osgood & Anderson, 2004).

4. THE NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT OF ADOLESCENCE: HOW NEIGHBORHOODS LOOK

4.1. Shifting Back Upstream

Current research on neighborhoods as contexts of development remains largely grounded in a social disorganization framework and on the concepts, models, and mechanisms described previously. Although significant advancements have been made by researchers in these directions, one perhaps unintended result of this “social process turn” (Browning, Cagney, & Boettner, 2016) is the movement of neighborhoods research “downstream,” away from the “upstream” macrolevel factors that shape neighborhoods in the first place (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000). This hinders thinking about the extent to which neighborhoods represent different “ecological niches” or developmental contexts with respect to the distribution of risks and resources (Shinn & Toohey, 2003; Wilson, 1987), and any subsequent implications for development in adolescence or across the life course. That is, when we are attuned primarily to neighborhood processes (e.g., the “black box” of neighborhood effects), we are less able to conceptualize and capture neighborhoods as indicative of individuals’ social location and position in the opportunity structure—as markers of intersecting social divisions. This also limits the ability to make comparisons across neighborhood types.

Concerns about the patterns and consequences of inequalities among social groups have dominated current research on the life course and stratification (e.g., Massey & Denton, 1993; O’Rand, 2001; Wilson, 1987). Yet, research tends to examine the effects of neighborhoods independent from the residential sorting or segregation processes that perpetuate significantly different neighborhood contexts for individuals according to their racial/ethnic and class group membership (Osypuk, 2013), as well as the actual geographic location of these neighborhoods.

Although individuals act independently, the possibilities they face and the decisions they make are constrained by their social positions (Merton, 1996) and their associated limitations, whether those are actual or perceived (Galster & Killen, 1995). With respect to neighborhoods specifically, individual choices and preferences are conditioned by opportunities and constraints—those of individuals, those of the market, and those that stem from larger social forces and policies (e.g., zoning and other land use practices; federal, state, and local housing policies; exclusionary housing ordinances; subsidized suburban development; discrimination, perceived/experienced harassment). All of these are driven by or based on the three social cleavages described earlier: race/ethnicity, social class, and geography (Osypuk, 2013; Squires & Kubrin, 2005, p. 48). As such, the “choice” to reside in a given neighborhood reflects a decision made, not among the whole set of neighborhoods, but among a limited number of relatively similar neighborhoods defined by one’s opportunities and resources. We now briefly review the historical context of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic residential segregation and inequality in the United States. This is crucial to understand because the question of “who goes where and why” is linked to how places come to be.

4.2. Neighborhood Patterning: Social Cleavages and the Stratification of Life Chances

Just as the Chicago School scholars observed that social problems are not randomly distributed across the city—but rather clustered in certain types of places—types of places themselves are not randomly distributed. The clustering of types of places is particularly characteristic of the United States. The physical separation of socially defined groups is inherently geographical (Massey, Rothwell, & Domina, 2009, p. 74). Indeed, geography itself is a marker of stratification and inequality (Lobao, 2004), although it remains frequently absent from studies of race/ethnicity and class. Neighborhoods reflect how groups are sorted and sifted according to their political and economic resources—that is, neighborhoods both define, and are defined by, persons’ life chances (Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2003). Individuals are differentially sorted into particular types of contexts (and not into others); contexts socialize individuals, who themselves modify their behavior in response to their environment (Mayer, 2004). Consequently, the concern with distinguishing the “unmeasured” characteristics that might lead individuals to “choose” certain neighborhoods (and thus may render a contextual effect “artifactual”) stands in contrast with the argument that selection is not a statistical nuisance but is rather an important social process that requires explicit investigation (McLeod & Pavalko, 2008; Sampson & Sharkey, 2008).

4.2.1. Racial/Ethnic Stratification and Segregation

Race is a fundamental cleavage in the United States (Massey & Sampson, 2009) and a dominant organizational principle of housing and residential patterns (Massey & Denton, 1993). As a result, different racial/ethnic groups are exposed to vastly different spatial contexts, with varying degrees of risks and resources (Osypuk, 2013). Explanations for racial segregation generally revolve around three issues: (1) economic differences (e.g., class segregation, income differences); (2) preferences and prejudices of individuals and families (e.g., White avoidance of Black neighborhoods, racial differences in housing preferences); and (3) institutional discrimination (e.g., housing market discrimination; Quillian, 2002). For instance, segregation may result because groups with greater economic resources are able to translate those resources into better residential outcomes (i.e., access more desirable communities), while disadvantaged groups, lacking those same resources, are sorted into less desirable housing in separate neighborhoods.b

In terms of racial preferences, advantaged groups strive to put spatial distance between themselves and less-advantaged groups (South & Crowder, 1998). Studies confirm the desire among Whites for neighborhoods that are predominantly White, and the desire among Blacks for neighborhoods that have at least some presence of other Blacks (Quillian, 2002). Similarly, racial and ethnic biases may underlie institutional practices and barriers in housing markets. Although formal means of discrimination have been largely outlawed—as part of the Fair Housing Act—there is evidence that informal discriminatory practices remain (Yinger, 1995) and that fair housing enforcement is sporadic.c

Racial discrimination (toward both individuals and neighborhoods) in lending practices has been singled out as having played a pivotal role in the subprime boom, housing market collapse, and financial crisis of the mid-2000s (Burd-Sharps & Rasch, 2015; Squires, Hyra, & Renner, 2009). As a consequence of the Great Recession, the racial wealth gap has widened, as White households have been rebounding but Black households have been struggling to recover. The foreclosure crisis had implications for communities too, as homeowners deferred maintenance on their homes and houses became vacant. These problems in turn contributed to declining property values and physical deterioration; to crime, social disorder, and population turnover; and to local government fiscal stress and the deterioration of services (Kingsley, Smith, & Price, 2009). Most notably, the fallout from the housing crisis occurred differentially across neighborhoods, affecting predominantly minority and low-SES neighborhoods most profoundly.

4.2.2. Class Stratification and Segregation

Prior to the 1970s, inequality was largely structured along race/ethnicity; thereafter, it became increasingly structured along social class lines—meaning that poor- and working-class Whites, as well as minorities, were (and are) confronted with similar social problems (Massey & Sampson, 2009). Indeed, neighborhood segregation is one of the most significant factors in raising consciousness of social class and class stratification (Giddens, 1980). Social stratification shapes land use (i.e., zoning), and land values are influential for which groups choose (or are chosen) to go where they do (Gans, 2002). Migration of residents away from moderately poor neighborhoods has been a key factor in the formation of high-poverty neighborhoods (Quillian, 1999), particularly in urban areas (Wilson, 1987). Historically, studies have shown the effect of race to be larger than that of class in driving migration and, accordingly, the bulk of segregation research focuses on racial segregation, not class segregation. Recent studies, however, have revealed that the effect of class is increasing (Massey & Sampson, 2009), and that segregation by class (particularly income) has risen sharply (Reardon, Fox, & Townsend, 2015).

Class stratification and segregation are persistent and upward socioeconomic mobility is differentially attainable. Recent work by Sharkey (2008), for example, illustrates the intergenerational influence of residential segregation by class. Children who grow up in poor neighborhoods are at a grave risk of living in poor neighborhoods as adults, and in turn pass that disadvantage onto their own children. Class segregation is particularly consequential for youth, since income segregation contributes to disparities in youth-serving resources, such as schools, parks, libraries, and recreation spaces (Bischoff & Reardon, 2014). Thus, schools are critical in the transmission process because the highest quality schools and best-prepared students are concentrated in resource-rich areas, while the lowest quality schools and worst-prepared students are concentrated in areas that are resource scarce, exacerbating class inequalities (Massey, 1996). Schools have traditionally been funded locally—by property taxes—further disadvantaging poorer communities, and although school finance reform addressed some of these challenges, notable disparities remain in school spending, educational opportunities, and outcomes (Rice, 2004). Continuing the example of educational attainment, class segregation can affect youth well-being and inequality in two distinct ways (Bischoff & Reardon, 2014). First, youth who grow up in poor neighborhoods may have fewer high-achieving adult role models. Second, high-income communities are better able to attract high-skilled teachers, leading to unequal school resources and inequalities in school success across neighborhoods.

Federal housing programs (e.g., Section 8) were designed to free families from public housing and therefore help poor families leave impoverished neighborhoods for more integrated ones. However, many voucher holders remain concentrated in poor segregated neighborhoods due to limited housing options, landlord practices/preferences, and aspects of the voucher program itself (e.g., time limits for locating housing; DeLuca, Garboden, & Rosenblatt, 2013). Further, the growth in income inequality in recent decades has largely been driven by “upper-tail inequality” (Reardon & Bischoff, 2011)—that is, “the rich got richer” while most other groups stayed the same or got worse, with the result being greater geographic concentration of affluence than poverty (Massey, 1996; Massey et al., 2009). The increasing isolation of rich and poor families has become visible in the declining number of middle-income communities (Squires & Hyra, 2010), paralleling the persistent lamentations about the “disappearing middle class” (Lazonick, 2015).

The recent foreclosure crisis has spurred increased attention to the impact of housing policy on child development, especially policies that address the features of housing units themselves. Housing features such as physical quality, crowding, homeownership, residential mobility, subsidized housing, and affordability are all theorized to affect development both directly (e.g., via exposure to toxins, such as lead paint) and indirectly (e.g., via a family’s stress and resources; Leventhal & Newman, 2010).

Although most research focuses on the detrimental consequences of neighborhood disadvantage for youth, some research finds that concentrated affluence may also undermine well-being—as it, too, has been associated with unhappiness, depression, worse parent–child relationships, and substance use (Luthar & Sexton, 2004; see also Warner, 2016). It is therefore imperative that researchers probe the full range of types and consequences of class stratification and segregation for youth development and well-being.

4.2.3. Geographic Stratification and Segregation

Resources and services are differentially distributed across neighborhoods on the basis of geography. Some neighborhoods have more schools, churches, and libraries; others have more homeless shelters and group homes; and still others are completely lacking in services (Oakley & Logan, 2007). The differential geographic distribution of services and resources also has implications for residents’ life chances and well-being across the life course, as disadvantage is consequential in any place that is plagued by risks and poor in resources and opportunities (Lobao & Hooks, 2007).

This is not simply a problem of variability among neighborhoods in more urban areas. Indeed, the economic transformation of rural America today has prompted dislocations similar to the urban dislocations of a few decades ago (Burton, Lichter, Baker, & Eason, 2013). Yet, due to a “nostalgic romanticization of agrarian society” (Tickameyer & Duncan, 1990, p. 69), rural residents have historically been characterized as more socially integrated and better regulated. Thus, the social problems of rural places are, in contrast to urban ones, relatively neglected. But the reality is that rural places are characterized by persistent concentrated poverty and high-income inequality (Lichter &Johnson, 2007). In impoverished rural areas, the poor are doubly disadvantaged, suffering from low income, a lack of institutional support and resources, and physical, cultural, and economic isolation from mainstream America (Jensen, McLaughlin, & Slack, 2003, p. 130)—creating what Burton et al. (2013) call “rural ghettos.”

The housing crisis and Great Recession also affected the geographic patterning of people and places. The suburban poor now outnumber their central city counterparts, and it is these suburban poor residents who face particular challenges to maintain compliance with the rules and regulations of government assistance programs (e.g., mandatory participation in work preparation or community service, see Butz, 2016). Following the recession, poverty peaked in rural areas, and recovery has been slow. Most notably, increases in postrecession poverty rates were highest for rural children (United States Department of Agriculture et al., 2015).

Rural areas have experienced their own unique set of macrolevel social problems: the rise of agribusiness and big-box retailing that has undermined local businesses, the decline of unions and blue-collar wages, employers’ increased reliance on (and exploitation of) undocumented workers, and the systemic underinvestment in young workers entering the labor force without college degrees (Carr & Kefalas, 2009). All of these contributed to what Carr and Kefalas (2009) call the “rural brain drain”—a “hollowing out” of rural places that occurs when areas lose their most talented/skilled/educated young people, who migrate to metropolitan areas in search of healthier labor markets and greater opportunities (possibly improving their life chances, but with devastating consequences for those left behind). Sherman and Sage (2011) noted that such brain drain has also led parents in rural communities to view education with ambivalence—recognizing it as their children’s best hope for success, but also seeing the educational system as a catalyst that pushes the best and brightest young residents out of the area.

The detrimental consequences of racial/ethnic and class spatial segregation are therefore exacerbated when coupled with segregation by type of geography (e.g., rural, urban, suburban, exurban). The focus on urban/metropolitan areas in neighborhood research has limited the ability to fully understand the intersection of racial/ethnic, class, and geographic social cleavages, and how structural inequality plays out across types of places. Spatial boundaries and barriers mark social divisions, all of which have tangible effects on human development across the life course (Irwin, 2007).

4.3. Geographies of Opportunity: Neighborhoods as Springboards or Snares

As noted earlier, life course theory is attuned to issues of time, process, and context. It emphasizes the interplay between macrolevel influences—especially of history, demography, and policies—and individual-level biographies. It emphasizes the joint contribution of “agency” and “structure” in determining individuals’ opportunities and outcomes. That is, individuals’ opportunities and outcomes are, on one hand, due to their own efforts and capacities but also, on the other hand, due to social forces that systematically leave some people rewarded and others disadvantaged as a function of their location in society.

Disadvantage experienced early in life can set into motion a series of cascading socioeconomic and lifestyle events—“chains of risk” (Kuh, Ben-Shlomo, Lynch, Hallqvist, & Power, 2003) or “cumulative disadvantage” (Dannefer, 2003)—that have negative implications for development and trajectories of well-being (Sharkey, 2008; Wickrama & Noh, 2010). Of course, early advantage can accumulate in similar ways, furthering resources and protections as people grow up and older. The neighborhoods in which people live reflect these cumulative processes. Neighborhoods affect residents’ possibilities for future success. They are landscapes of uneven risks, resources, hazards, and protections (Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2003; O’Rand, 2001), where factors such as school quality, employment, crime, availability of health care and other services, and environmental conditions (e.g., pollution, toxins) influence health and well-being in childhood and adolescence (Leventhal & Newman, 2010) and beyond. This is important because, as Robert (1999) notes, empirical studies may find the independent effects of neighborhood context at any given moment are rather small, but the overall importance of neighborhoods is likely to be substantial when one accounts for the intertwined nature of neighborhood effects with those of families, schools, and peer groups; their cumulative effect over the lifetime; and their collective effect on large numbers of people.

As noted earlier, neighborhoods are major markers of social status. Status differences are expressed in where people live and in how whole social groups are sorted and even stigmatized on the basis of them. For instance, individuals tend to possess a cognitive hierarchical map of neighborhoods as good or bad, reflecting the social and economic characteristics of those residents (Semyonov & Kraus, 1983). Neighborhoods not only reinforce status hierarchies, but they engender in residents a place identity. Places “claim” people, and individuals view themselves relative to their surrounding environment—as Cheng, Kruger, and Daniels (2003, p. 90, emphasis in original) argue, “…to be somewhere is to be someone.”

Neighborhoods affect individual outcomes through the channeling and concentration of certain types of individuals into certain types of neighborhoods, creating relatively homogeneous neighborhood groups. That is, the characteristics on which individuals are sorted into different types of neighborhoods represent social stratification processes. Thus, neighborhoods become a means for mediating the effects of individual factors on outcomes, and individual-level factors become a means for mediating the effects of neighborhoods on outcomes. Both are possibilities because neighborhoods are a product of and a means for social stratification. Yet, the usual methods of analysis and interpretation—“variable-centered” approaches examining neighborhood context via single items or indices related to composition—obscure these facts, which lead researchers to make conclusions based on the (unrealistic) premise of “all things being equal.” Neighborhoods are rarely equal because they are both the result of and a mechanism to reinforce inequality.

5. A NEIGHBORHOOD-CENTERED APPROACH

Because race/ethnicity and social class covary so strongly in the United States, neighborhood effects research tends to discuss their effects in tandem (Sucoff & Upchurch, 1998, p. 573). For example, the percentage of Black residents in an area is often used as an indicator of socioeconomic disadvantage, or it is combined with other measures such as the poverty rate, because these measures are highly correlated (Land, McCall, & Cohen, 1990). Despite this, racial/ethnic and social class composition are not equivalent. Recent research on residential segregation suggests that their intersection is becoming increasingly important for the structuring of spatial inequality (Dwyer, 2010; Massey et al., 2009). As such, it will be useful to assess neighborhoods in ways that interrogate how race/ethnicity and class intersect to jointly and simultaneously (re)produce inequality (Choo & Ferree, 2010).

Treating compositional characteristics as independently modeled control variables obscures heterogeneity, “decontextualizes” data (Luke, 2005), and leads researchers to ignore the meaning behind particular contexts and the causes and consequences of patterns and constellations of compositional characteristics. For example, “percent Black,” while associated with various negative outcomes, is not in and of itself a particularly meaningful construct (nor can “social structure” be captured in a single measure). Rather, “percent Black” is a proxy for a set of social forces and experiences (e.g., blocked opportunities, limited resources) that may be similarly applicable in places not characterized by a large proportion of Black residents (e.g., predominantly White poor rural areas) or not applicable in nonurban places with a high composition of Black residents (e.g., predominantly Black rural areas or middle-class Black areas).

Extending the focus on “variable-centered” methods to the intersection of the three key social cleavages described earlier—neighborhood race/ethnicity, social class, and geography—will allow us to bridge “ways of thinking about” neighborhoods with “ways of measuring” them (Burton, Price-Spratlen, & Spencer, 1997, p. 132). It involves more nuanced considerations of neighborhoods as contexts that capture the challenges faced by, or resources available to, persons because of group memberships, socioeconomic positions, and spatial locations (Leung & Takeuchi, 2011; O’Rand, 2001; Williams, Mohammed, Leavell, & Collins, 2010).

A move in this direction calls for a multidimensional and relational approach, one that does not attribute causality to single independently operating independent variables (Abbott, 1998). Although advances in multilevel modeling techniques (e.g., HLM) have allowed the analytical recognition that individuals are embedded in larger contexts (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), these models nonetheless remain concerned with identifying the independent main effects of structural factors—attempting to explicate the effect of one factor “net of” others, which is a problem because nothing in the social world occurs “net of other variables” (Abbott, 1992, p. 6). Coulton and Spilsbury (2014, p. 1308) succinctly noted that much neighborhood effects research “has tended to reify neighborhoods as vessels floating in a vacuum at a point in time, relatively impervious to the social and economic processes that shape them.” We must therefore explore how causal conditions combine to produce given outcomes; otherwise, resulting knowledge is both incomplete and biased (Cole, 2009, p. 173).

One way to continue advancing the study of neighborhoods for adolescent development in a manner that is consistent with the theoretical premise that neighborhoods are socially defined places is to seek inspiration from the “person-centered” approach in the field of human development (Cairns, Bergman, & Kagan, 1998). This approach identifies patterns or “constellations” among variables in the data, rather than relying on singular measures or linear relationships between a few variables. Just as person-centered approaches have been used to differentiate heterogeneity among individuals, these same approaches can be applied to the environments in which persons are nested (Bogat, 2009).

A “neighborhood-centered” approach would take the neighborhood as the key conceptual and analytical unit, emerging from the structural components that formulate it. Traditional multilevel modeling techniques treat each geographic unit (e.g., census tracts) as if it is distinct from the next, comparing average effects of compositional measures across a sample of tracts. A neighborhood-centered approach would instead treat tracts as groups, where a set of tracts share similar characteristics that are distinct from another set. Such an approach would take neighborhoods to be latent constructs that represent the nexus of social structural forces manifested in the primary interactive environments of daily life and that can be compared.

To capture fully the multidimensional intersections between race/ethnicity, class, and geography in linear models, one could theoretically compute several 3- and 4-way interactions. However, such higher order interaction terms are difficult to interpret and can imply combinations of variables that may not exist in reality or are infrequently observed in the data, which further undermines their utility (Weden et al., 2011). What is instead needed for a neighborhood-centered approach is a method that allows the emergence of neighborhood types represented in the data—classifying neighborhoods holistically (Plybon & Kliewer, 2002) and configurationally (Ragin, 2008). One such method is latent class analysis (LCA; Vermunt, 2008), which can be used to uncover and describe contextual patterns (Luke, 2005) and complex intersections among covarying measures (Dupéré & Perkins, 2007). A neighborhood-centered approach explicitly recognizes the social structural foundation of neighborhoods, allows for the exploration of neighborhood effects across all geographies, and facilitates comparative research (e.g., especially beyond comparisons of poor Black urban neighborhoods and White middle-class neighborhoods).

A neighborhood-centered approach using LCA can reveal unknown or previously unmeasured heterogeneity (Luke, 2005). Only a few prior studies have examined “types” of neighborhoods (e.g., Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996; Gorman-Smith, Tolan, & Henry, 2000; Sucoff & Upchurch, 1998) and none have done so using data in which multiple geographies (urban, suburban, and rural) are represented—thus, geography has been absent. A finer-grained description of neighborhoods is needed to understand how the structural dimensions of neighborhood inequality are linked to human development in different life periods and over the life course.

6. AN EMPIRICAL DEMONSTRATION

6.1. Trajectories of Adolescent Violent Victimization Across Neighborhood Types

To more fully introduce a “neighborhood-centered” approach, we illustrate how LCA can embrace the intersection of race/ethnicity, class, and geography, and how a neighborhood-centered approach permits the exploration of neighborhood effects across multiple geographies. Specifically, we explore the extent to which adolescent violent victimization is embedded in and shaped by neighborhood context.

6.1.1. The Concentration and Consequences of Adolescent Violent Victimization

Adolescence is characterized by increasing autonomy, yet with this comes increased exposure to various risks. Particularly troubling is the increased risk of violent victimization, which is disproportionately concentrated among youth (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, Hamby, & Kracke, 2009; Truman, Langton, & Planty, 2013). For instance, 2008 data from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV) show that 61% of children aged 17 and younger were exposed to or experienced violence in the past year, and 46% were assaulted. Violent victimization in adolescence is a risk factor for depressive symptoms (Latzman & Swisher, 2005), anger and aggression (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006), fatalism (Warner & Swisher, 2014), substance abuse (DeMaris & Kaukinen, 2005), and suicidal thoughts and actions (Cleary, 2000).

Further, victims of violence are also at risk of experiencing subsequent victimization (Schreck, Stewart, & Osgood, 2008) and becoming violent perpetrators themselves (Menard, 2002). The 2008 NatSCEV data also show that as many as 39% of youth experienced two or more victimizations. Although research is limited, it does illustrate that victimization trajectories follow a similar pattern to the well-established age–crime curve: an increase during early adolescence, a peak around ages 15–17, and steady declines into young adulthood (Sullivan, Wilcox, & Osey, 2011). Many explanations for victim continuity are situational, pointing to lifestyles and routine activities that bring into contact potential victims and motivated offenders in environments that lack capable guardianship (i.e., social control). The environmental risks for victimization are particularly applicable to youth, who lack the autonomy to alter the neighborhoods environments that are “imposed” upon them (Sharkey, 2006). Within these imposed neighborhood environments, youth do have agency over their “selected” environments, although as Sharkey (2006) found, exposure to neighborhood disadvantage undermines adolescents’ confidence in their ability to avoid violence, which in turn influences the types of environments they select for themselves.

Neighborhoods are therefore a crucial context for taking a developmental perspective on victimization, as they carry social and structural characteristics that heighten personal vulnerabilities to crime. In the remainder of this chapter, we address three specific objectives to: (1) develop a typology of neighborhoods based on multidimensional and intersecting characteristics of neighborhood racial/ethnic composition, socioeconomic class, and geography; (2) compare trajectories of risk across adolescent neighborhood types, considering the long-term consequences of neighborhood context for the violent victimization of adolescents and young adults; and (3) determine the extent to which neighborhood type affects trajectories of violent victimization through individual, peer, and family characteristics.

6.2. LCA of Neighborhood Types

We used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health, a nationally representative school-based sample of adolescents in grades 7 through 12, first conducted between 1994 and 1995, with follow-up interviews in 1996 (Wave II), 2001–2002 (Wave III), and 2007–2008 (Wave IV, when respondents were aged 24–34 [detailed information about the design of Add Health can be found in Harris (2005)]). Respondents were sampled from schools that were (disproportionately) stratified by region, urbanicity, school type, racial/ethnic composition, and school size, resulting in a sample of students from a variety of geographic areas (e.g., urban, suburban, and rural).

6.2.1. Analytic Sample

Our analyses proceeded in two stages—the first addressing Objective 1 and the second addressing Objectives 2 and 3. The analytic samples, measures, and strategies differed for each stage. The first stage of the analytic plan used data from the Wave I Add Health in-home interview, along with data from the Wave I Contextual Database (containing demographic indicators from the 1990 US Census; Billy, Wenzlow, & Grady, 1998) and the Obesity and Neighborhood Environment (ONE) add-on (Harris & Udry, 2008), which provides built environment indicators. Analyses for Objective 1 used the 2366 Census tracts from the Wave I contextual data.d

6.2.2. Measures

Neighborhood class was measured via four indicators. The first was the tract-level proportion of residents living below the poverty line. An assumption of LCA is that continuous indicators are normally distributed (Collins & Lanza, 2010; McCutcheon, 1987); therefore, given the highly skewed distribution of this indicator (see Weden et al., 2011), this item was collapsed as: 0=<0.03 (affluent), 1 = 0.03–0.10 (low poverty), 2=0.10–0.20 (moderate poverty), 3=0.20–0.40 (high poverty), 4=>0.40 (extreme poverty; seeJargowsky & Bane, 1991; Timberlake, 2007). Next, neighborhood educational composition was measured via two dummy variables: low education (=1 if the tract proportion of residents with less than a high school education was greater than the grand mean) and high education (=1 if the tract proportion of residents with a college degree was higher than the grand mean). Finally, we included tract-level median household income to differentiate better between neighborhoods falling along the socioeconomic continuum.e

Neighborhood ethnic diversity was assessed with two separate indicators of the proportion of Hispanic residents and foreign-born residents to distinguish predominately native-born Hispanic neighborhoods from predominately immigrant neighborhoods. Neighborhood racial composition was measured with three separate indicators of the proportion of non-Hispanic White residents, non-Hispanic Black residents, and residents who are non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander or other race. Both sets of measures were also highly skewed; the proportion of White residents was therefore recoded as: 0=<0.40 White, 1=0.40–0.80 White, and 2=>0.80 White. The proportion of residents non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander/other, and proportion foreign born were recoded into the following categories: 0=<0.05, 1=0.05–0.10, 2=0.10–0.20, 3=0.20–0.50, and 4=>0.50. Different thresholds were used for minorities to correspond better with their representation in the US population (Friedman, 2008).

Neighborhood geography was captured via five measures. Urbanicity/rurality was measured as the proportion of the tract that is urban (collapsed into 0=0; 1=0.1–0.99; 2=1.00 [completely urban]). Because almost all new single-family construction since 1974 has taken place in the suburbs, and it is the availability of these new homes that distinguishes suburbs (and possibly “exurbs,” Frey, 2012) from central cities (Gyourko & Linneman, 1993), the analyses included a measure of median house age as a proxy for sub-urbanicity (and following Nelson, Gordon-Larsen, Song, & Popkin, 2006). This was collapsed as follows: 0=<15 years, 1=15–25, 2=25–35, 3=35–50, 4=>50. The cylcomatic index is the number of route alternatives between intersections (measured at a 3-km radius around respondents’ homes, see Nelson et al., 2006); it ranges from 2 to 2947, where higher values indicate greater accessibility/connectivity. Although more often used by epidemiologists interested in “built environment” characteristics (than in traditional “neighborhood effects” research), we used the measure to further distinguish types of geographic areas (the measure was collapsed into quartiles). Finally, given documented regional differences in neighborhood types—for instance, the South and Midwest are considerably more “exurban”f (Berube et al., 2006)—dummy variables for southern and western regions were included.

6.2.3. Analytic Strategy

As a person-centered, model-based, probabilistic analytic strategy, LCA is a statistical method for identifying unmeasured class membership among observations. It estimates posterior probabilities (the probability of membership in a particular latent class [c]), and observations are assigned to the latent class for which the posterior probability is highest (Lanza, Collins, Lemmon, & Schafer, 2007). Such probabilistic strategies bring the risk of classification error, but in the case of these Add Health census tracts, the posterior probabilities resulting from our LCA were quite high. For instance, over 90% of the tracts in the Add Health data were assigned to a latent class with posterior probabilities at or above 0.90, which is much higher than the 0.70 criterion recommended for establishing reliable categorizations (Nagin, 2005) and increases our confidence in the rigor of these classifications. In the growth curve analyses (described later), neighborhood type was measured by c number of dummy variables (the number of latent classes identified).

6.3. Results

The number of potential neighborhood types, while unknown, is not infinite, and there are a sizeable number of possible combinations across these 13 measures in a large-scale dataset-like Add Health. To ascertain the best solution for capturing meaningful neighborhood types, we tested up to 15 classes. In order to balance model fit and parsimony, and provide adequate statistical power for comparing neighborhoods, our choice of model solution was guided by fit statistics (Akaike Information Criterion [AIC], Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC]), model comparison tests (likelihood-ratio statistic L2), and an effort to ensure that each neighborhood type contained approximately 5% of census tracts. Based on these criteria, we chose a 10-class solution as most appropriate. Model fit statistics are displayed in Table 1, which shows a diminishing of the percent decrease in the L2 statistic and an uptick in the Entropy R2 (an indicator of classification certainty) around the 10-class solution.g

Table 1.

Model Fit Statistics for Latent Class Analysis of Neighborhood Types

| L 2 | % Reduction in L2 | BIC (L2) | AIC (L2) | Entropy R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Class | 31,236.26 | 12.89 | 13,274.44 | 26,612.26 | 0.87 |

| 3-Class | 28,237.79 | 9.60 | 10,384.73 | 23,641.79 | 0.89 |

| 4-Class | 26,487.35 | 6.20 | 8743.05 | 21,919.35 | 0.91 |

| 5-Class | 24,978.07 | 5.70 | 7342.54 | 20,438.07 | 0.93 |

| 6-Class | 23,977.94 | 4.00 | 6451.17 | 19,465.94 | 0.92 |

| 7-Class | 23,048.01 | 3.88 | 5630.01 | 18,564.01 | 0.92 |

| 8-Class | 22,288.84 | 3.29 | 4979.61 | 17,832.84 | 0.92 |

| 9-Class | 21,707.28 | 2.61 | 4506.81 | 17,279.28 | 0.92 |

| 10-Classa | 21,208.99 | 2.30 | 4117.23 | 16,808.99 | 0.93 |

| 11-Class | 20,747.10 | 2.18 | 3764.17 | 16,375.10 | 0.93 |

| 12-Class | 20,314.18 | 2.09 | 3440.01 | 15,970.18 | 0.93 |

| 13-Class | 20,033.83 | 1.38 | 3268.43 | 15,717.83 | 0.94 |

| 14-Class | 19,669.99 | 1.82 | 3013.35 | 15,381.99 | 0.93 |

| 15-Class | 19,392.19 | 1.41 | 2844.32 | 15,132.19 | 0.93 |

A −2LL bootstrapping test was also used to assess the fit of the 10-class solution; compared to a 9-class solution, the test statistic (−2LL difference = 498.29, p = 0.0000) indicates the 10-class solution provides a better fit than a solution with fewer classes.

Notes: L2 is the likelihood-ratio Chi-square statistic, which indicates the amount of the association among the variables that remains unexplained after estimating the model; the lower the value, the better the fit of the model to the data.

Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, Wave I (n = 2366 census tracts).

6.3.1. Labeling Neighborhood Types

The process of developing labels for the neighborhood types was guided by expectations grounded in theory, previous research, documented patterns of residential segregation, and, much like factor analysis, some subjective judgments. After selecting the 10-class solution, we reviewed the distributional patterns of the 13 indicators across each of the neighborhood types to construct meaningful labels to capture the intersections of the three social cleavages. We also reviewed the distributional patterns of additional contextual indicators not used in the LCA (e.g., proportion female-headed households, households receiving public income, population employed in occupational/managerial professions, proportion employed in farming/forestry/fishing occupations, etc.) to further facilitate the labeling of the emergent types.

We labeled the 10 neighborhood types as follows: (1) Upper-Middle-Class White Suburban, (2) Poor Black Urban, (3) Working-Class Mixed Race Urban, (4) Working-Class White Rural, (5) Middle-Class Hispanic/Asian Suburban, (6) Middle-Class Black Urban, (7) Poor Hispanic/Immigrant Urban, (8) Poor White Urban, (9) Mixed-Class White Urban, and (10) Poor Black Rural.h

Table 2 provides a subset of compositional characteristics for comparing the 10 neighborhood types and a portion of the data used for labeling neighborhood types. The neighborhoods designated as predominantly White had an average population that was almost entirely White (over 90% White), but readers may be confused as to why we labeled other neighborhoods as mixed race or minority neighborhoods when Whites still comprised a large share of the population. There is no standard definition for classifying the racial dominance of a neighborhood, but our assessment of neighborhood racial/ethnic composition was informed by Logan and Zhang (2010) 25% rule (that for a racial/ethnic groups to have a distinct presence it must cross a threshold of 25%) and other commonly employed racial cutoffs (e.g., Fischer & Massey, 2004; Friedman, 2008). In 1990, Whites comprised 80% of the US population, Blacks 12%, and Asians/Pacific Islanders 3%; about 9% of the population identified as being of Hispanic ethnicity.

Table 2.

Select Descriptive Characteristics of Neighborhood Type Indicators, Means, and Standard Deviations (in Parentheses)

| Socioeconomic Class | Racial/Ethnic Composition/Heterogeneity | Geography | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poverty | Median Income (1000s) | <HS Degree | College Degree | NH White | NH Black | Hispanic | Foreign Born | Urban | |

| Neighborhood type a | |||||||||

| Upper-Middle-Class White Suburb [18.3%] | 0.046 | 42.928 | 0.120 | 0.386 | 0.912 | 0.038 | 0.028 | 0.042 | 0.770 |

| (0.027) | (12.437) | (0.049) | 0.126 | 0.074 | 0.057 | 0.032 | 0.034 | 0.381 | |

| Middle-Class Hispanic/Asian Suburb [10.4%] | 0.075 | 41.300 | 0.192 | 0.320 | 0.558 | 0.099 | 0.185 | 0.199 | 0.945 |

| (0.039) | (9.327) | (0.079) | 0.118 | 0.190 | 0.161 | 0.114 | 0.141 | 0.210 | |

| Working-Class White Rural [11.1%] | 0.140 | 25.666 | 0.306 | 0.157 | 0.952 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.193 |

| (0.083) | (6.584) | (0.103) | 0.062 | 0.050 | 0.037 | 0.032 | 0.012 | 0.365 | |

| Poor Black Urban [12.1%] | 0.391 | 14.968 | 0.467 | 0.096 | 0.124 | 0.807 | 0.060 | 0.048 | 0.999 |

| (0.135) | (5.538) | (0.089) | 0.042 | 0.194 | 0.218 | 0.091 | 0.083 | 0.007 | |

| Poor Black Rural [4.4%] | 0.275 | 19.449 | 0.377 | 0.153 | 0.529 | 0.448 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.148 |

| (0.118) | (6.123) | (0.120) | 0.085 | 0.217 | 0.227 | 0.029 | 0.020 | 0.330 | |

| Poor White Urban [8.0%] | 0.162 | 22.911 | 0.256 | 0.221 | 0.906 | 0.039 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.986 |

| (0.104) | (5.145) | (0.111) | 0.143 | 0.070 | 0.041 | 0.042 | 0.037 | 0.106 | |

| Working-Class Mixed Race Urban [11.3%] | 0.179 | 27.186 | 0.331 | 0.226 | 0.466 | 0.200 | 0.247 | 0.251 | 0.999 |

| (0.068) | (5.997) | (0.106) | 0.114 | 0.235 | 0.240 | 0.123 | 0.137 | 0.010 | |

| Poor Hispanic/Immigrant Urban [8.6%] | 0.278 | 20.838 | 0.546 | 0.124 | 0.177 | 0.078 | 0.713 | 0.437 | 0.995 |

| (0.107) | (6.154) | (0.107) | 0.063 | 0.072 | 0.122 | 0.163 | 0.209 | 0.071 | |

| Middle-Class Black Urban [9.1%] | 0.151 | 28.295 | 0.233 | 0.269 | 0.338 | 0.616 | 0.030 | 0.047 | 0.998 |

| (0.079) | (6.798) | (0.079) | 0.123 | 0.286 | 0.303 | 0.037 | 0.066 | 0.013 | |

| Mixed-Class White Urban [6.8%] | 0.054 | 38.696 | 0.257 | 0.288 | 0.912 | 0.012 | 0.052 | 0.136 | 1.000 |

| (0.031) | (11.984) | (0.092) | 0.134 | 0.047 | 0.017 | 0.031 | 0.072 | 0.000 | |

Number in [] indicates percentage of study census tracts categorized into each type.

Source: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health Wave I (n = 2366 census tracts).

Following Fischer and Massey (2004), we defined predominantly Black neighborhood types as those with at least 60% Black residents, which matches the average proportion Black for Poor Urban and Middle-Class Urban Black neighborhoods, but does not for the neighborhood type we label Poor Black Rural (on average 45% Black); however, because 90% of the non-metropolitan population was White, it is very likely that 45% Black (on average) is a significant and noticeable presence of Black residents (also noteworthy, 99% of the tracts in this type were located in the South). The neighborhood type we designated Hispanic/Asian Suburb is distinguishable from the one labeled Mixed Race by their different Black populations (10% vs 20%, respectively) and Asian/Pacific Islander and other race populations (16% vs 9%, respectively [not shown]).

Designating neighborhood socioeconomic class is also challenging, as there is no standard definition of “social class” in general nor standardized distinctions between gradations within class categories (upper, middle, working, lower, etc.). Further, definitions of social class are relative, and commonly employed measures of class—such as median household income—vary by both race (highest among Whites) and geography (highest in suburban areas; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1992). For instance, Whites live in very different types of neighborhoods than their non-White counterparts—where the poorest predominantly White neighborhood is not nearly as impoverished as the poorest non-White neighborhoods. This is also illustrated here. Recent work on residential segregation reveals that poor Whites tend to live in more affluent neighborhoods than even middle-class Blacks and Latinos (Reardon et al., 2015) and that the average affluent Black or Hispanic household is located in a poorer neighborhood than the average low-income White household (Logan & Zhang, 2010).

It is therefore important to be mindful of such pernicious effects of racial/ethnic residential segregation when attempting to label neighborhoods in a way most consistent with their composition. Following Jargowsky (2003), we defined neighborhoods with 40% or more of the population in poverty as poor/high poverty. We also used the 1990 race-specific household income distribution to inform the development of neighborhood type labels.i No neighborhood type emerging in these data met the criteria for what might be considered “affluent” based on the top 5% of household income (Solari, 2012). Another designation (e.g., Massey et al., 2003) is to use the top fifth of the income distribution as an indicator of affluence, which was $55,205 in 1990. Thus, we labeled the “wealthiest” observed neighborhood type as Upper-Middle Class because its average median household income was $42,928. Education was also useful for making distinctions. For instance, the median household income for what we termed a Mixed-Class neighborhood was $38,696, but an average of 26% of tracts were above the median on the proportion of residents without a high school education (compared to only 12% of tracts in Upper-Middle-Class neighborhoods). Although we are unable to measure it in these data, we speculate that this Mixed-Class White Urban neighborhood—given its high-income and educational stratification, sizeable foreign-born population, and older house ages (not shown)—may be capturing gentrified neighborhoods, which are themselves controversial because gentrification may displace predominantly poor residents and further exacerbate class inequalities (Newman & Wyly, 2006).

The lower limit of median household income for the middle and fourth quintile in 1990 was $23,662 and $36,200, respectively, which we used—along with education and poverty—to inform our assessment of “middle-class” and “working-class” areas. Given the patterns of racial residential segregation discussed previously, our distinctions of neighborhood social class were done within race, which is why, for instance, the average median household income of Poor Black Urban neighborhoods is so much lower ($14,968) than that of Poor White Urban neighborhoods ($22,911), and the income of Middle-Class Black Urban neighborhoods ($28,295) only slightly higher than that of Working-Class White Rural neighborhoods ($25,666) (readers should also note the patterning of education across these types).

Finally, we relied on indicators of proportion urban, house age, region, and street connectivity to identify neighborhood geography, as (again) there is no standardized, universally accepted definition of urban, rural, or suburban. We labeled as urban those neighborhood types where, on average, the tracts were characterized as having 95% or more of its residents living inside an urbanized area (these neighborhoods also had high street connectivity measures). Of the remaining neighborhoods, house age and proportion rural residents informed labeling, where classes with over 50% of residents in rural areas classified as rural. Classes with average house ages of approximately 20 years or less were labeled suburban.

6.4. A Neighborhood-Centered Analysis of Violent Victimization Trajectories

6.4.1. Analytic Sample

The second stage of the analyses examined trajectories of violent victimization across adolescent neighborhood types. We used data from the in-home interviews of Waves I–IV. For parsimony, we do not detail the derivation of the sample here, but details are available upon request. The final sample consisted of 18,630 adolescents, distributed across 2288 census tracts at Wave I.

6.4.2. Outcome Measure

Violent victimization.

Violent victimization was measured at each wave by four questions that asked how often, in the past year, respondents were (a) jumped or beaten up, (b) had a gun or knife pulled on them, (c) stabbed, or (d) shot. Respondents were coded as victim=1 at each wave if they reported any of the four experiences (else=0 if they did not experience any victimization).

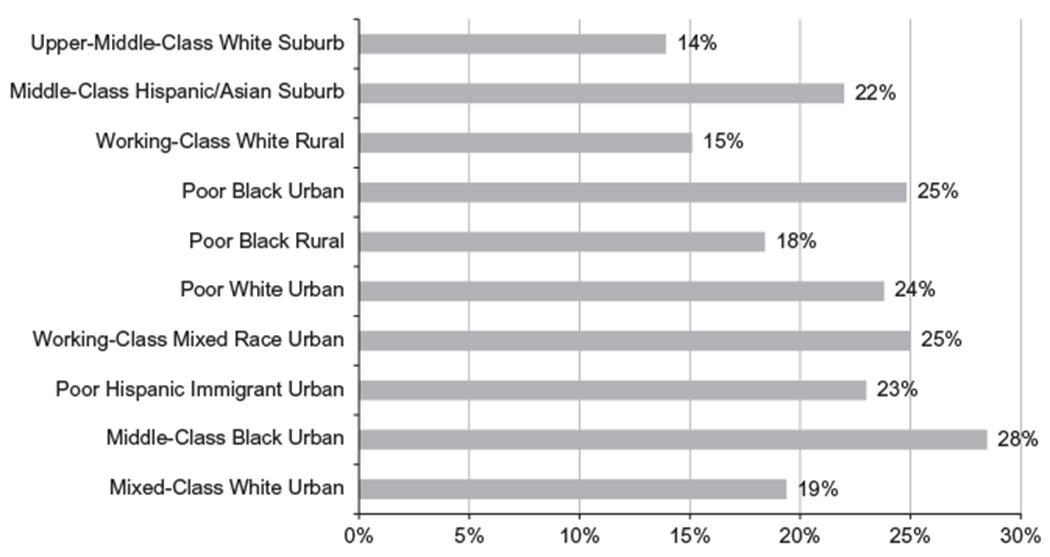

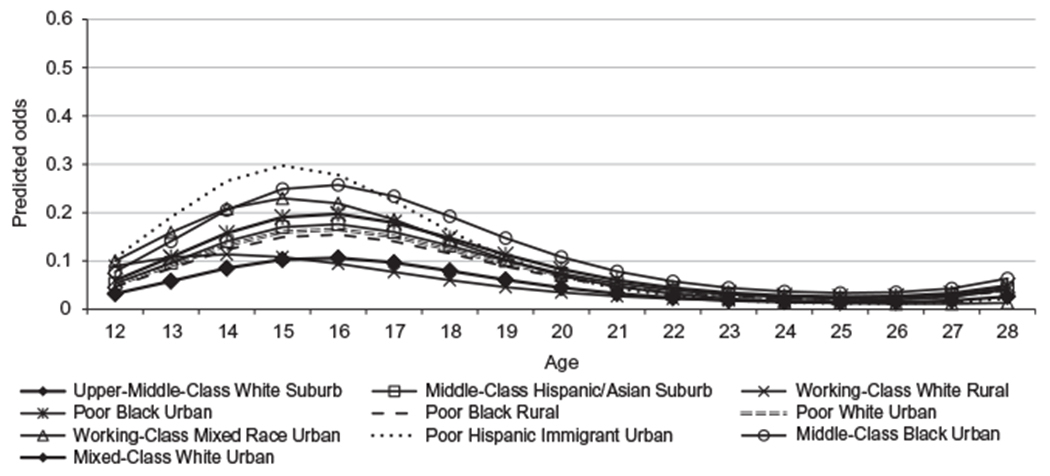

Fig. 1 displays the percentage of youth victimized at age 15 by neighborhood type [we use age 15 to correspond with the peak of the age–crime curve described earlier (DeCamp & Zaykowski, 2015)]. This figure shows considerable variation across neighborhood types—for instance, 29% of 15 year olds from Middle-Class Black Urban neighborhoods had been violently victimized, compared to only 14% of 15 year olds from Upper-Middle-Class White Suburbs. This patterning is comparable to geographic trends in youth violent victimization for this same time period, as reported in the National Crime Victimization Survey (Snyder & Sickmund, 2006).

Fig. 1.

Percent of youth violently victimized at age 15, by neighborhood type.

We drew from extant literature to inform our modeling of the indirect effects of neighborhoods on victimization. As discussed earlier, neighborhood characteristics affect the availability and type of peers to whom youth are exposed (Haynie, 2001), and the amount of time they spend with those peers in unstructured activities (Osgood & Anderson, 2004). The family is another institution through which neighborhood characteristics influence behaviors, primarily because of the family’s role in supervision and informal social control. Neighborhood disadvantage undermines parental efficacy, and ineffective, uninvolved, or even hostile parenting has detrimental consequences for youths’ well-being that also makes adolescents more susceptible and/or vulnerable to delinquent peer influence and opportunity (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Wickrama & Noh, 2010). Even personal characteristics such as self-control may mediate neighborhood effects, with recent studies suggesting that neighborhood disadvantage may contribute to low self-control and impulsivity (Teasdale & Silver, 2009).

Our final objective, therefore, explored how the effect of neighborhood type on trajectories of violent victimization operates through indicators of individual, family, and/or peer mediators. Details about these measures (including their coding) are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Independent Variables Measures and Coding for Analyses of Developmental Trajectories of Violent Victimizationa

| Constructb | Indicators and Response Options |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood accessibility | |

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Gender | Dummy variable for female (0/1) |

| Family characteristics | |

| Family socioeconomic status | Combined scale of parent’s education and parent’s occupational level (0–9; Bearman & Moody, 2004) |

| Family structure | Dummy variable for lived with both biological parents (=1; 0 = all other arrangements) |

| Mediators of neighborhood effects | |

| Individual mediators | |

| Relative pubertal development | Self-rated physical development compared to same-aged peers (range −2 = “I look younger than most” to 2 = “I look older than most”) |

| Low self-control | Scale of past year experiencing “trouble keeping your mind on what you were doing,” “trouble getting your homework done,” “difficulty paying attention in school,” and the extent to which adolescents feel “like you are doing everything just about right”; higher scores represent lower self-control |

| School attachment | Likert scale of the extent to which respondents feel (a) close to people at school, (b) part of their school, and are (c) happy to be at their school (higher scores correspond to greater school attachment) |

| Academic aspirations | Measured from the question: “On a scale of 1–5, how likely is it that you will go to college?” |

| Life course transitions | Time varying (measured at each wave); three dichotomous indicators capturing whether the respondent was (a) in school, (b) working, and/or (c) married at each wave |

| Violent perpetration | 4-item count of any past year perpetration (e.g., “been in a serious fight”; range 0–4) |

| Nonviolent delinquency | 10-item scale of past year perpetration (e.g., vandalism, theft; range 0 = never to 3 = 5 or more times) |

| Marijuana use | Any marijuana use in the past month (1 = any; 0 = none) |

| Family mediators | |

| Parental attachment | Mean of responses to the questions: “How close do you feel to your mother [father]?” and “How much do you feel that your mother [father] cares about you?” (responses range 0 = not at all to 4 = very much) |

| Family support | Scale of adolescents’ reports about the extent to which they feel their family (a) understands them, (b) pays attention to them, and (c) they have fun together (response range 0 = not at all to 5 = very much) |

| Parental autonomy | Mean of two items asking whether parents let respondent make decisions (1 = yes, 0 = no) about “what time to be home on weekend” and “which friends you hang out with” |

| Peer mediators | |

| Unstructured socializing | Measured via the question: “During the past week, how many times did you just hang out with friends” (response range from 0 = not at all to 3 = 5 or more times) |

Unless otherwise noted, all indicators are measured at Wave I.

Models also controlled for years lived in neighborhood at Wave I.

6.4.3. Analytic Strategy

We estimated a series of three-level models, with multiple observations over time (age [centered at 15]) nested within persons (respondents), who are in turn nested within census tracts. We conducted preliminary analyses (not shown) to determine the specification of fixed and random effects for change in victimization with age; comparisons of fit for models of increasing complexity indicated that a cubic model with random intercept and random linear slope provided the best fit.

6.5. Results

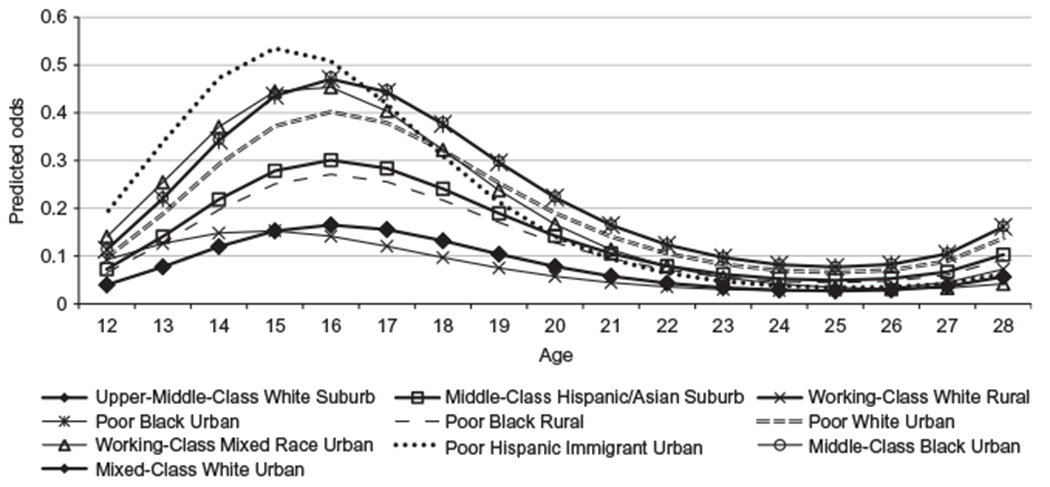

We ran a series of growth curve models exploring the role of neighborhood type in anchoring and shaping trajectories of violent victimization in adolescence and young adulthood. Analyses were stratified by gender because there are significant gender differences in overall risks for victimization (Lauritsen & Heimer, 2009). Figs. 2 through 5 illustrate the unadjusted (neighborhood type only) and adjusted (neighborhood type, plus all other covariates) models of the effects of adolescent neighborhood type on victimization trajectories, with Upper-Middle-Class White Suburb as the reference category. To simplify our presentation, we display the results in figures rather than tables, although we do discuss some specific coefficients from multivariate tables which are available from the authors upon request.

Fig. 2.

Males’ trajectories of violent victimization, predicted odds (unadjusted).

Fig. 5.

Females’ trajectories of violent victimization, predicted odds (adjusted).

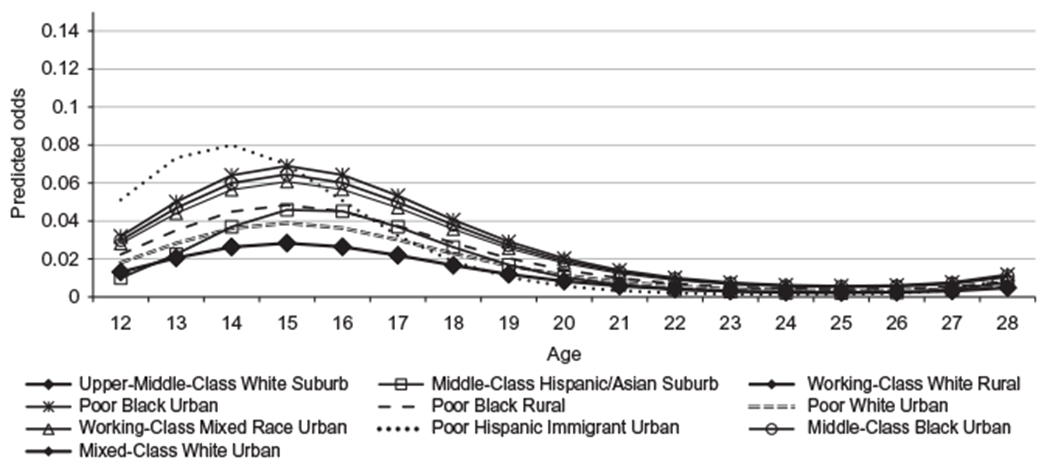

We begin with the victimization trajectories for youth across the 10 neighborhood types, with males shown in Fig. 2 and females shown in Fig. 3. The figure for males shows a fairly consistent increase in victimization risk in early adolescence, peaking around age 15, and followed by a steady decline through age 29. However, the figure also illustrates considerable variation in the height of peak victimization risk, as well as variation in the rate at which it declines. For instance, odds of victimization at age 15 were highest for males from Poor Hispanic Immigrant Urban neighborhoods. Compared to their peers from Upper-Middle-Class White Suburbs, these youth were 78% more likely to be victimized. On the other hand, young men from Working-Class White Rural neighborhoods did not differ from their UMC suburban peers in risk at age 15, but their trajectories of risk declined more quickly between ages 15 and 22, such that they were actually less likely to be victimized during these years, a perhaps surprising finding given this rural neighborhood is more socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Fig. 3.

Females’ trajectories of violent victimization, predicted odds (unadjusted).

A neighborhood-centered approach allows us to observe variation among predominantly White neighborhoods (e.g., youth from Poor White Urban neighborhoods were 71% more likely than UMC suburban peers to have been victimized [at age 15]), and variation across neighborhoods with similar socioeconomic profiles (e.g., youth from MC Hispanic and Asian suburbs were 65% more likely than UMC suburban peers to have been victimized). The unadjusted models for young women display similar variation (Fig. 3), for instance, showing that females from Poor Black Urban neighborhoods were 83% and girls from Mixed-Class White Urban neighborhoods were 63% more likely to be victims (at age 15) than their UMC White suburban peers.

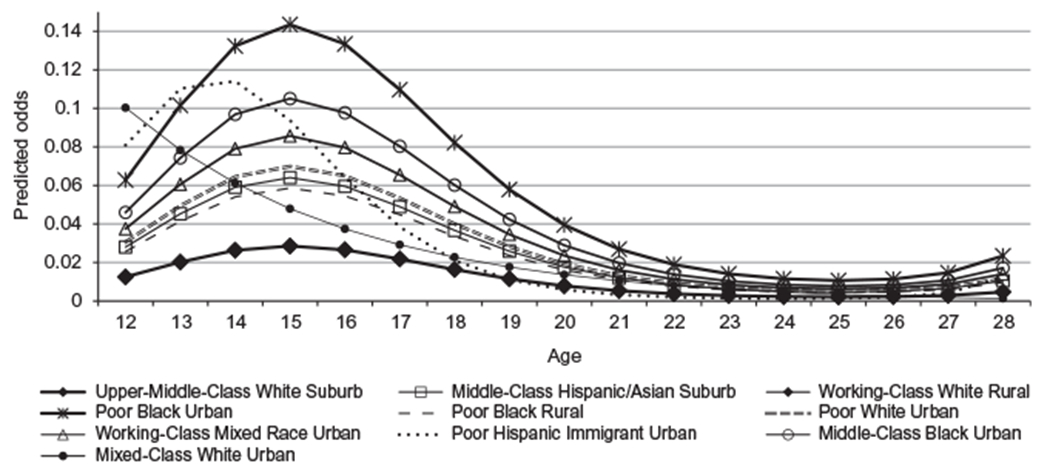

The adjusted models, which include a range of theorized mediators, are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5. As both figures show, variation in victimization risk remained, although differences were minimized. For both young men and women, the effects of neighborhood type were partially mediated by individual characteristics, particularly involvement in risky behaviors, such as substance use and violent and delinquent behaviors. But it is important to note that the main effects of neighborhood type on victimization nonetheless remained statistically significant. The inclusion of these mediators helps answer the question not of whether neighborhoods matter, but how they matter—in this case, operating through neighborhood opportunity structures by differentially shaping youths’ exposure to deviant/delinquent opportunities and to deviant/delinquent others.

Fig. 4.

Males’ trajectories of violent victimization, predicted odds (adjusted).